95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Microbiol. , 06 December 2019

Sec. Virology

Volume 10 - 2019 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2019.02764

Plant viruses are thought to be essentially harmful to the lives of their cultivated crop hosts. In most cases studied, the interaction between viruses and cultivated crop plants negatively affects host morphology and physiology, thereby resulting in disease. Native wild/non-cultivated plants are often latently infected with viruses without any clear symptoms. Although seemingly non-harmful, these viruses pose a threat to cultivated crops because they can be transmitted by vectors and cause disease. Reports are accumulating on infections with latent plant viruses that do not cause disease but rather seem to be beneficial to the lives of wild host plants. In a few cases, viral latency involves the integration of full-length genome copies into the host genome that, in response to environmental stress or during certain developmental stages of host plants, can become activated to generate and replicate episomal copies, a transition from latency to reactivation and causation of disease development. The interaction between viruses and host plants may also lead to the integration of partial-length segments of viral DNA genomes or copy DNA of viral RNA genome sequences into the host genome. Transcripts derived from such integrated viral elements (EVEs) may be beneficial to host plants, for example, by conferring levels of virus resistance and/or causing persistence/latency of viral infections. Studies on viral latency in wild host plants might help us to understand and elucidate the underlying mechanisms of latency and provide insights into the raison d’être for viruses in the lives of plants.

So far, virologists have focused only on a parasitic relationship between plant viruses and their host plants. In most described cases, the interaction between viruses and host plants negatively affects host morphology and physiology, resulting in disease (Hull, 2014). In a majority of cases, viruses are virulent and cause disease in crops during their mono-cultivation in open fields or greenhouses for food production. Not surprisingly, the current taxonomy of plant viruses is primarily based on viruses isolated from cultivated crops showing disease symptoms (Wren et al., 2006; Owens et al., 2012). However, a survey on latent infections of plant hosts has revealed that some plants may be infected with viruses without any clear symptoms (Roossinck, 2005, 2010; Richert-Pöggeler and Minarovits, 2014). More recent studies using a metagenomic approach have revealed that asymptomatic infections of plants with viruses might be a much more common event in nature than initially thought (Kreuze et al., 2009; Barba et al., 2014; Stobbe and Roossinck, 2014; Kamitani et al., 2016; Pooggin, 2018; Zhang et al., 2018). Asymptomatic infections may result from tolerance, in which plants do not suffer from wild type (high titer) virus replication levels, or from viral persistence, in which virus titers are reduced to avoid cytopathic effects and harm to the host. During virus latency, no viral replication occurs, and viruses remain in a kind of silenced/dormant status. Since a number of definitions of tolerance to viruses exist in genetics, physiology, and ecology, the relation of tolerance to virus titer still remains to be discussed (Little et al., 2010; Råberg, 2014). In the following sections, an overview will be given of plant virus latency. During this entire overview, discussion of viral latency also refers to viral persistence, since many studies have not distinguished between latency and persistence. Possible underlying mechanisms will be discussed, as well as how plant virus latency/persistence may be harmful or beneficial to the life of plants.

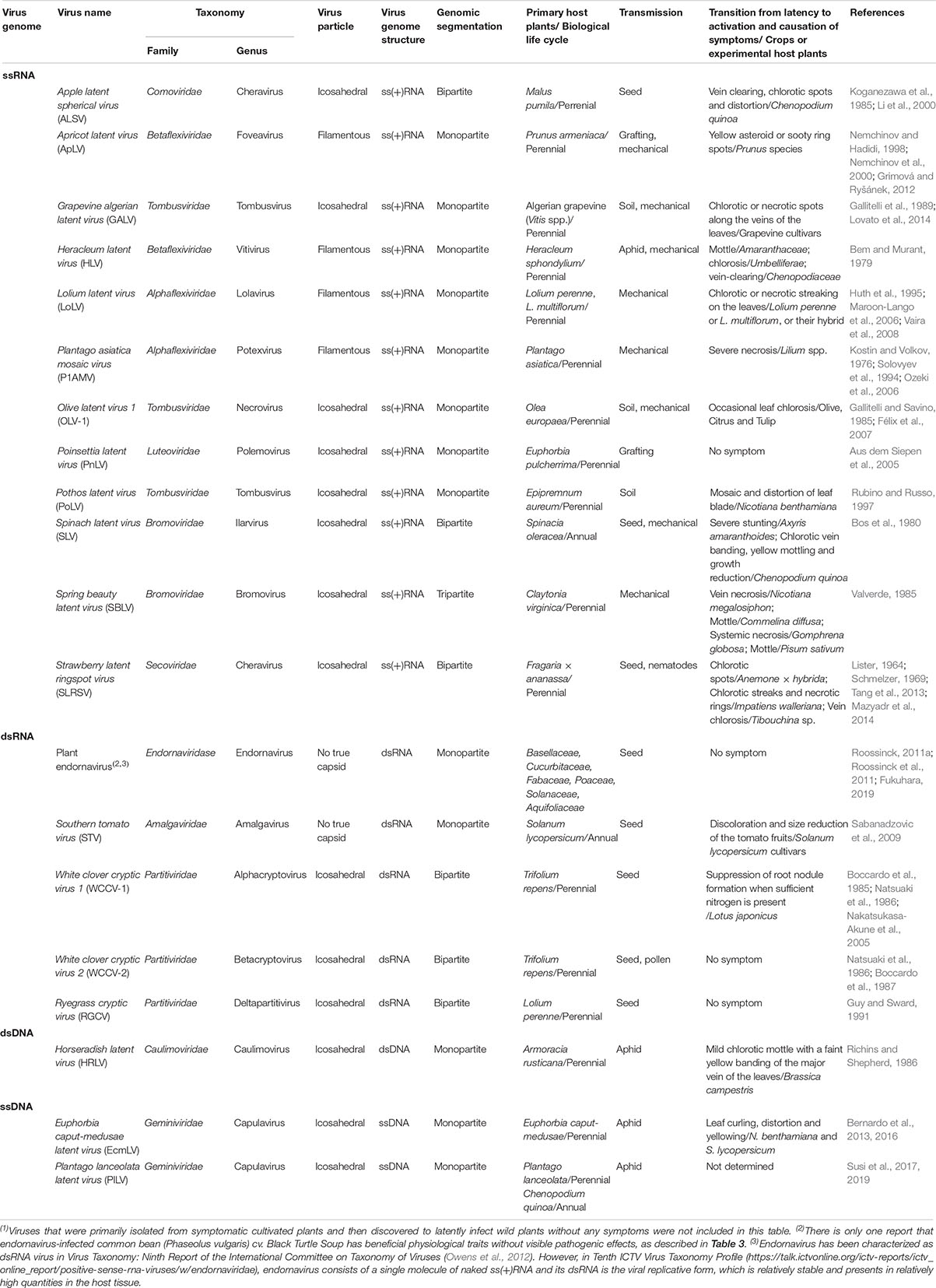

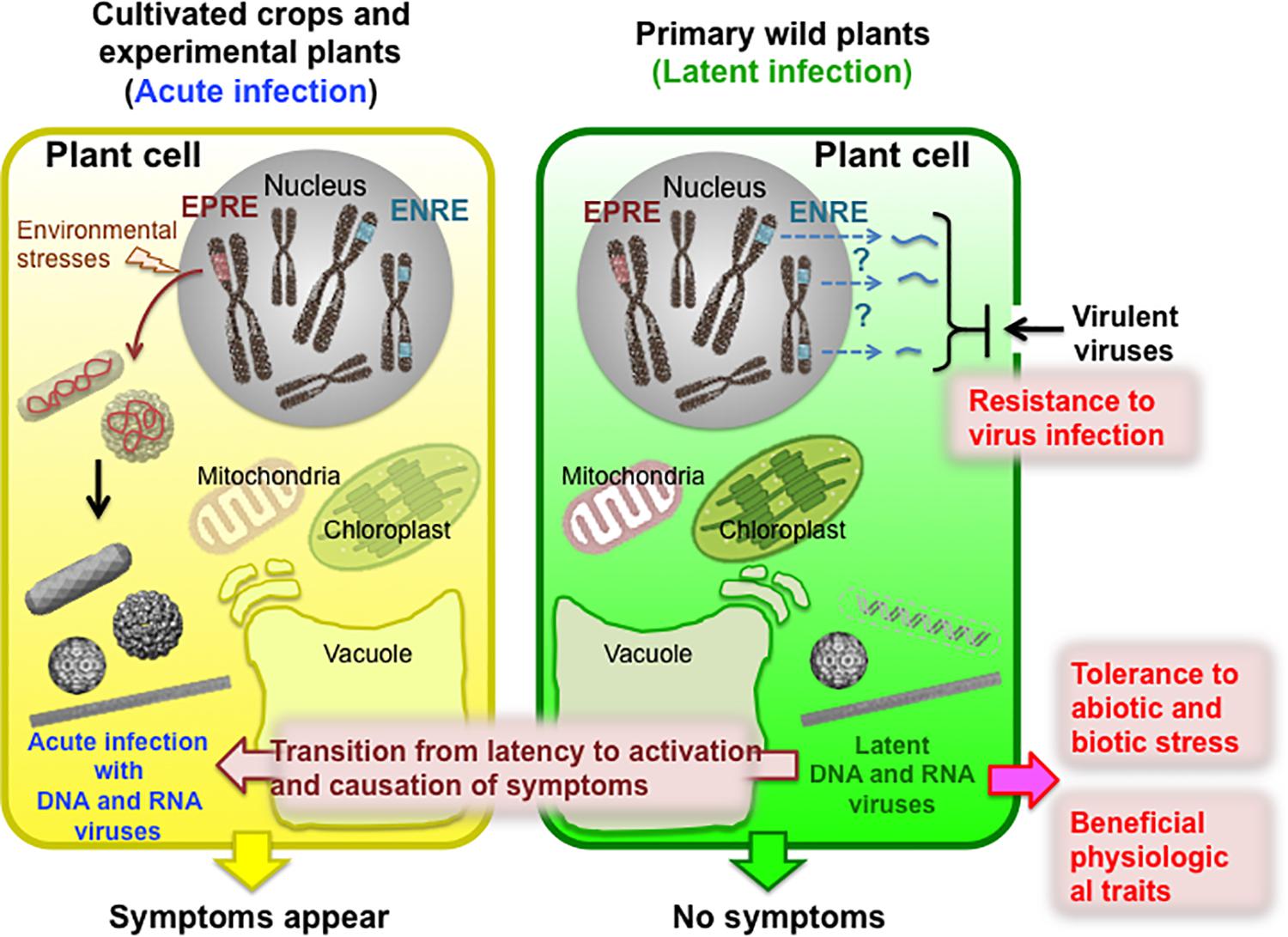

Wild plants are often latently infected with viruses in nature without any apparent disease symptoms (Min et al., 2012; Shates et al., 2019). Table 1 is a list of plant viruses that are reported to latently infect primary wild host plants and to transition from latency to activation in crops or experimental host plants with the appearance of disease symptoms. Latent viruses are apparently easily maintained in perennial plants (Hull, 2014). In the case of annual plants, latent viruses may be transmitted to the next generation of host plants through pollination, although the efficiency of seed-borne transmission depends on the virus and host plant (Hull, 2014). However, viruses that latently infect wild plants often cause disease symptoms in closely related crop plants through vector-mediated transmission and in experimental plants via mechanical wounding (Table 1) (Pagán et al., 2012; Roossinck and Garcia-Arenal, 2015). Moreover, in perennial plants asymptomatically infected with viruses, a transition from latency to activation and the appearance of disease symptoms occasionally occurs during mixed infections with other viruses, changing environmental conditions, or during certain host plant growth stages (Table 1 and Figure 1).

Table 1. List of plant viruses featuring a latent infection and possible transition from the latency to the causation of symptoms(1).

Figure 1. Schematic of positive and negative effects of latent virus infection on wild host plants in nature. Wild plants are often latently/persistently infected with viruses without exhibiting any apparent symptoms. Moreover, endogenous viral elements, such as endogenous pararetroviral elements (EPREs) and endogenous non-retroviral elements (ENREs), have become integrated into the genomes of some host plant species. The latent infection can occasionally transition to activation into an acute infection accompanied by the appearance of disease symptoms. This activation can occur due to vector-mediated transmission to cultivated crops, mixed infections with other viruses, environmental stresses, or the particular developmental stage of plant growth. However, latent/persistent infections can be of benefit to plants, such as by conferring resistance to infection by another virus, tolerance to abiotic or biotic stresses, or beneficial physiological traits that improve the lives of host plants.

Latent infections with positive single-stranded [ss(+)] RNA viruses are found in many host plants (Table 1). Viruses in those studies have primarily been isolated from asymptomatic cultivated plants or wild plants. However, latent infections occasionally convert into acute infections with the appearance of disease symptoms, as nicely observed in the following examples. Apricot latent virus (ApLV) was first isolated from asymptomatic Prunus armeniaca in Moldavia in 1993 (Zemtchik and Verderevskaya, 1993). However, some Prunus species, after being inoculated by grafting a healthy scion onto ApLV-infected P. armeniaca as a rootstock, become ApLV-infected and exhibit yellow asteroid or sooty ring spots on their leaves (Martelli and Jelkmann, 1998; Grimová and Ryšánek, 2012). Grapevine algerian latent virus (GALV) was first isolated in Italy from an Algerian vine (Vitis spp.) infected with grapevine fanleaf virus (GFLV) and is considered a latent virus due to the presence of only GFLV-related symptoms (Gallitelli et al., 1989). Passage of this mixed infection to nipplefruit (Solanum mammosum) and statice (Limonium spp.) causes severe stunting, chlorotic spots, and mosaic symptoms (Lovato et al., 2014). Heracleum latent virus (HLV) was isolated in Scotland from Heracleum sphondylium that showed no disease symptoms (Bem and Murant, 1979). When this virus is transmitted by aphids to host plants in the Amaranthaceae, Chenopodiaceae, and Umbelliferae families, it causes leaf mottle, chlorosis, and systemic vein-clearing symptoms (Bem and Murant, 1979). Plantago asiatica mosaic virus (PIAMV) was originally isolated from Plantago asiatica L. and latently infects a wide range of plant species, except cereals (Kostin and Volkov, 1976; Solovyev et al., 1994). Recently, PIAMV has been found in Lilium spp. (Oriental types) showing severe necrosis of the leaves (Ozeki et al., 2006). Knowledge on ss(+) RNA virus infections in native perennial grasses is slowly accumulating (Malmstrom and Alexander, 2016; Alexander et al., 2017) and also points to cases of viral latency. Lolium latent virus (LoLV) was initially detected in several areas in Europe, including Germany, the Netherlands, France, and the United Kingdom, as Ryegrass latent virus (Huth et al., 1995). LoLV has also been reported in the United States for the first time in ryegrass hybrids (Lolium perenne x L. multiflorum) (Maroon-Lango et al., 2006; Vaira et al., 2008). Plants infected with LoLV alone exhibit either no symptoms or mild chlorotic flecking, but the flecks coalesce to form chlorotic to necrotic streaking on the leaves depending on environmental conditions and growth stage.

Double-stranded (ds) RNA viruses from the families Amalgaviridae, Chrysoviridae, Endornaviridae, Partitiviridae, and Totiviridae are found in plants, fungi, and protists (Roossinck et al., 2011; Song et al., 2013). Other virus-like sequences related to those families have been discovered by in silico surveys using known dsRNA viral sequences as queries against the NCBI Expressed Sequence Tag (EST) database (Liu et al., 2012). Whereas plant endornaviruses and amalgaviruses do not form true particles, plant cryptoviruses of the family Partitiviridae form icosahedral particles (Table 1) (Owens et al., 2012). The latter viruses are usually present at low copy numbers, have no obvious effects on the host plant, and can be maintained as a latent infection during the life of a perennial or be efficiently transmitted vertically via gametes (Table 1) (Fukuhara, 2019). Southern tomato virus (STV) belongs to the amalgaviruses, which are also known to latently infect plants without forming true particles (Martin et al., 2011) and are thought to represent a transitional intermediate between totiviruses and partitiviruses (Sabanadzovic et al., 2009). However, a correlation between the presence of STV dsRNA and discoloration and size reduction of fruits in some tomato cultivars suggests that infection with STV may cause abnormal development depending on the cultivar (Sabanadzovic et al., 2009). White clover cryptic virus 1 (WCCV-1), WCCV-2, and ryegrass cryptic virus (RGCV) are members of the family Partitiviridae, that commonly appear in plants and fungi (Boccardo et al., 1985, 1987; Natsuaki et al., 1986; Guy and Sward, 1991). Interestingly, WCCV-1 is thought to play a role in the regulation of the host-rhizobium symbiosis (Nakatsukasa-Akune et al., 2005). WCCV-2 and RGCV do not induce clear symptoms on either their natural or experimental host plants (Table 1).

Although latent infections often correlate with the absence of symptoms, negative effects of such infection may be manifested in other plant traits and/or at certain developmental stages. In this sense, recent studies have indicated that asymptomatic infections may reduce plant survival depending on the growth stage (Fraile et al., 2017; Rodríguez-Nevado et al., 2017). However, despite these studies, the effect of virus infection on the survival of wild plants remains largely unknown.

The family Caulimoviridae includes all plant viruses with circular double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) genomes with a reverse transcription phase in their lifecycles. The caulimovirus Horseradish latent virus (HRLV), isolated from horseradish (Armoracia rusticana) (Table 1) (Richins and Shepherd, 1986), causes latent infections in the natural host plant Armoracia rusticana, but mild chlorotic mottling symptoms can be observed during infection of some Brassica plants with HRLV (Richins and Shepherd, 1986).

Members of the family Geminiviridae are characterized by a circular single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) genome that is encapsidated within a twinned icosahedral particle. Geminiviruses infect both monocotyledonous and dicotyledonous plants and cause major losses in agricultural production worldwide. Seven genera are recognized within this family, but, recently, two new additional genera, Capulavirus and Grablovirus, have been established (Varsani et al., 2017). Euphorbia caput-medusae latent virus (EcmLV) and plantago lanceolata latent virus (PILV), both classified as Capulavirus, latently infect their natural host plants, Euphorbia caput-medusae and Plantago lanceolata, respectively (Bernardo et al., 2016; Susi et al., 2017). PILV was discovered during a viral metagenomics survey of uncultivated Plantago lanceolata and Chenopodium quinoa plants that did not exhibit symptoms (117; 118). Symptom development has not been examined in crops or experimental plants challenged with PILV yet. Although EcmLV-inoculated Euphorbia caput-medusae do not exhibit any symptoms, EcmLV-inoculated Nicotiana benthamiana and tomato plants exhibit leaf curling, distortion, and yellowing (Bernardo et al., 2013).

From the growing number of reports described above, it becomes clear that wild host plants are often asymptomatically infected with viruses and that these may transform from latency to activation. Considering that the viruses reported and described above in relation to latency belong to different plant virus families with as many different lifestyles also raises the question of how these viruses end up in a stage of latency and whether or not there is an underlying generic mechanism to this.

Considering that latent virus infections might also improve the survival, genetic diversity, or population density of wild host plant species in nature, knowledge on their biology will provide insights that might lead to potential future exploitations for cultivated crops and be related to beneficial effects on plant hosts, e.g., increased resilience toward (a)biotic stress factors (see sections further below). Although the underlying mechanism of plant virus latency remains elusive, some cases implicate endogenized viral elements (EVEs) in this.

All types of viruses can become endogenous by the integration of (partial) viral (copy) DNA sequences into the genomes of various host organisms (Figure 1) (Holmes, 2011; Teycheney and Geering, 2011; Feschotte and Gilbert, 2012; Aiewsakun and Katzourakis, 2015). These sequences are often and generally referred to as endogenized viral elements (EVEs), the most well-known ones coming from animal/human-infecting retroviruses like human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and several leukemia viruses. The replication of retroviral RNA genomes requires prior integration of a DNA copy of the entire viral RNA genome into the DNA of infected cells, mediated by a virus-encoded integrase. In a next step, transcription by the host machinery will produce progeny viral RNA. Thus, for retroviruses, endogenization is essential for the accomplishment of their life cycle, and these viruses are therefore debated as an example of EVEs. However, for none of the plant viruses known so far is the integration of a DNA copy required for their replication. During the past two decades, an increasing number of observations have been made on integrated plant viral sequences in the genome of various plant species. Most of them involve the integration of a partial viral genome sequence, but a few cases have been reported on the endogenization of entire viral genome sequences.

The first EVEs to be described in plants contained sequences that originated from two groups of plant viruses, both containing circular DNA genomes, i.e., the single-stranded DNA geminiviruses and the double-stranded DNA pararetroviruses (reviewed by Harper et al., 2002; Hohn et al., 2008; Iskra-Caruana et al., 2010). Meanwhile, EVEs have been found originating from a diverse group of plant nuclear and cytoplasmic replicating DNA and RNA viruses, respectively (Table 2) (Owens et al., 2012). Furthermore, integrated sequences have been reported that originate from ancestral viruses (Chiba et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2014; Diop et al., 2018). Nowadays, EVEs are commonly distinguished into two groups: those originating from pararetroviral elements (Endogenous pararetroviral elements [EPREs]) (Diop et al., 2018) and those containing any other plant virus sequence (Endogenous non-retroviral elements [ENREs]) (Chiba et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2014). Since many EPREs and ENREs integrated a long time ago, they are suggested to represent ancient relics of viral infection, and their study is called Paleovirology. However, recent studies indicate that these might not just represent molecular fossils but could play a role in pathogenicity or contribute to levels of resistance (Bertsch et al., 2009). Considering the latter, EVEs may well play a major role in the establishment of viral latency/persistence.

Most plant EPREs that have been characterized are derived from viruses in the family Caulimoviridae. The Caulimoviridae currently consists of eight genera: Badnavirus, Caulimovirus, Cavemovirus, Petuvirus, Rosadnavirus, Solendovirus, Soymovirus, and Tungrovirus, and the two tentative genera Orendovirus and Florendovirus (Table 2) (Bousalem et al., 2008; Geering et al., 2010). EPRV-like sequences derived from banana streak virus (BSV) in Musa spp., dahlia mosaic virus (DMV) in Dahlia spp., petunia vein-clearing virus (PVCV) in Petunia spp., tobacco vein-clearing virus (TVCV) in Nicotiana spp., and rice tungro bacilliform virus (RTBV) in Oryza spp. have been identified in their host genomes (Table 2) (Harper et al., 1999; Jakowitsch et al., 1999; Ndowora et al., 1999; Lockhart et al., 2000; Richert-Pöggeler et al., 2003; Eid and Pappu, 2014). EPREs corresponding to entire viral DNA genomes can generate episomal infections from their endogenous intact sequences within the host genome of specific cultivars in response to stress (Staginnus and Richert-Pöggeler, 2006). One of the most beautiful cases reports on an enemy from within a banana hybrid containing an endogenized copy of the Banana streak virus (BSV) genome (Iskra-Caruana et al., 2010). Episomal forms of BSV, DMV, TVCV, and PVCV apparently transition from latency to activation with the assembly of virus particles and symptoms of virus infection (Table 2) (Harper et al., 2002). Episomal copies may also be generated by transcription from tandemly arranged integrants or recombination from fragmented integrants in host genomes (Ndowora et al., 1999; Richert-Pöggeler et al., 2003). Interspecific crosses and in vitro propagation can induce EPRE reactivation, which has been shown to be economically detrimental in banana breeding (Chabannes and Iskra-Caruana, 2013).

In contrast to the relatively small number of reports on EPREs in which a full-length genome-copy has been integrated, most EPREs are non-infective because their sequences have been fragmented by deletions, mutations, or epigenetic modifications in plant genomes (Staginnus and Richert-Pöggeler, 2006; Staginnus et al., 2009). Segments of rice tungro bacilliform virus (RTBV) DNA have been identified between AT-dinucleotide repeats within several loci in rice genome databases (Kunii et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2012; Chen and Kishima, 2016). Furthermore, partial endogenous RTBV seems to have been generated by transcription from tandemly arranged integrants of RTBV or by recombination from fragmented integrants of RTBV in rice genomes (Chen et al., 2014). While active intact endogenous RTBV DNA has not been obtained from the rice genome, RTBV has been identified as the infectious agent of rice tungro diseases independently of its EPREs. Similarly, analysis of genomic sequences of Solanum lycopersicum and S. habrochaites revealed sequence similarity between their EPREs, named LycEPRVs, interspersed in these tomato genomes, indicating that they are potentially derived from one pararetrovirus (Staginnus et al., 2007). Furthermore, TA simple sequence repeats from endogenous florendoviruses have extensively colonized the genomes of two monocotyledonous plant species and 19 dicotyledonous plant species (Geering et al., 2014).

Endogenous non-retroviral elements (ENREs) in the genomes of host plants are derived from segmented and rearranged viral sequences of dsRNA, ssDNA, or ssRNA viruses (Table 2) (Bejarano et al., 1996; Ashby et al., 1997; Murad et al., 2004; Tanne and Sela, 2005; Liu et al., 2010; Chiba et al., 2011; Liu et al., 2012; Chu et al., 2014). ENREs in host plants predominantly match RNA-dependent RNA polymerase (RdRP)-like, movement protein (MP)-like, and coat protein (CP)-like sequences of dsRNA viruses (Liu et al., 2010, 2012; Chiba et al., 2011; Chu et al., 2014). The genomes of various host plants have also been observed to contain sequences from negative-ssRNA [ss(-)RNA] viruses (Chiba et al., 2011). These sequences are homologous to CP-like sequences of cytorhabdovirus and varicosavirus. The integration of sequences homologous to positive-ssRNA [ss(+)RNA] in host plant genomes has also been demonstrated (Tanne and Sela, 2005; Chiba et al., 2011). Nucleotide sequences homologous to a part of the CP gene and 3′-UTR of a potyvirus or to a portion of the CP and movement protein (MP) genes of cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) have been identified in the genomic databases of grape and Medicago truncatula, respectively. Many ENREs derived from these RNA viruses appear to be long interspersed elements created by reverse transcriptase and integrase activities encoded by host nuclear genomes or by non-homologous recombination between viral RNA and RNA generated from a retrotransposon.

Repetitive geminivirus-related DNA (GRD) sequences have also been discovered in host genomes and appear to have resulted from promiscuous integration of multiple repeats of the geminivirus initiation (Rep) sequence into the nuclear genome of an ancestor of some host plant species (Bejarano et al., 1996; Ashby et al., 1997; Murad et al., 2004; Liu et al., 2011).

In general, few studies have focused on the benefits of virus latent infection and EVEs for host plants or the mutualistic symbioses between these and their host organisms (Figure 1). Viruses with beneficial functions for or mutualistic symbioses with various host organisms, including bacteria, insects, fungi, and animals, have been discovered and are being given more attention relatively recently (Barton et al., 2007; Nuss, 2008; Roossinck, 2011b). For example, many pathogenic bacteria produce a broad range of virulence factors that have turned out not to be expressed from the bacterial genome but rather from a phage genome (Brüssow et al., 2004; Boyd, 2012). Many wasps deposit symbiogenic polydnavirus during egg deposition in a lepidopteran caterpillar host to expresses “wasp” genes that suppress host immune responses and prevent encapsulation of the egg, allowing the larva to develop and mature normally (Edson et al., 1981).

A mutualistic three-way symbiosis involving a fungal virus, curvularia thermal tolerance virus (CThTV), the fungal endophyte Curvularia protuberate, and the panic grass Dichanthelium lanuginosum helps the grass to tolerate high temperatures and grow in geothermal soils (Redman et al., 2002; Márquez et al., 2007; Roossinck, 2015a, b). CThTV infection induces the expression of genes involved in the synthesis of trehalose and melanin, which confer abiotic stress tolerance in the fungal endophyte and the plant (Morsy et al., 2010). While, slowly, the idea of mutualistic and beneficial effects of viruses on their host has become generally accepted, the effects may differ (mechanistically) between those caused by acute viral infections, viral latency, and/or EVEs.

While, a decade ago, Roossinck and colleagues discovered and emphasized the beneficial effects of viral infections for host plants (Xu et al., 2008; Roossinck, 2011b), meanwhile, several virulent strains of plant viruses such as cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) Fny strain [CMV(Fny)], bromo mosaic virus (BMV) Russian strain, tobacco mosaic virus (TMV) U1 strain, and tobacco rattle virus (TRV) have been shown to confer drought or cold tolerance to their host plants (Table 3) (Xu et al., 2008; Roossinck, 2013; Westwood et al., 2013). Although the molecular mechanisms underlying this conferred drought and cold tolerance have not yet been elucidated, several metabolites, including osmoprotectants and antioxidants that are associated with improved drought and cold tolerance, were observed to increase in these virus-infected plants (Xu et al., 2008).

In another recent study, the emission profile of volatile organic compounds from CMV(Fny)-infected Solanum lycopersicum and Arabidopsis thaliana altered the foraging behavior of bumblebees (Bombus terrestris), thereby increasing buzz pollination (Table 3) (Groen et al., 2016). Although CMV(Fny) infection decreased seed yield without buzz-pollination, the increased buzz-pollination in CMV(Fny)-infected plants raised their seed yields to levels comparable to those in mock-inoculated plants (Groen et al., 2016). Virus infections thereby positively affect plant reproduction through increased pollinator preference. Furthermore, A. thaliana plants infected with CMV(Fny) rendered seeds with improved tolerance to deterioration when compared to the non-inoculated plants (Table 3) (Bueso et al., 2017).

Plant viruses may also influence the susceptibility/preference of plants to biotic stressors of different natures. White clover mosaic virus (WCIMV) infection in Trifolium repens can decrease the attractiveness of white clover plants for female fungus gnats (van Molken et al., 2012). In zucchini yellow mosaic virus (ZYMV)-infected Cucumis sativa, attraction of the cucumber beetle, which can transmit the bacterial wilt pathogen Erwinia tracheiphila, was reduced (Shapiro et al., 2013). In both cases, the production of volatile compounds altered due to virus infection and appeared to protect host plants by decreasing herbivore infestation rates (van Molken et al., 2012; Shapiro et al., 2013). Thus, viruses clearly may have beneficial functions for plants in plant–herbivore interactions that could either involve attraction or repelling of certain insects. The effects of viral infections on plants are not limited to herbivores but are also reported in relation to fungal infections of plants. A comparative study using ZYMV-inoculated and non-inoculated controls cultivated in a greenhouse revealed that ZYMV-infected plants were more resistant to powdery mildew than the controls and that this seemed to be caused by elevated concentrations of salicylic acid, leading to enhanced pathogen defense responses (Harth et al., 2018).

Infection with most of the well-characterized viruses in crop plants is often acute; however, several plant species can be latently infected with viruses without showing symptoms (Roossinck, 2010, 2012a,b). Studies on viruses that latently infect host plants are still quite limited, and likewise the beneficial effects of latent virus infection, but this is slowly receiving growing interest (Table 3). Meanwhile, the protection of some plant virus strains that cause latent or mild infections against other more virulent strains has been well reported for many combinations of viruses and host plants so far (e.g., Agüero et al., 2018). For example, beet cryptic virus (BCV), a member of the family Partitiviridae, can prevent yield losses caused by drought conditions in latently infected Beta vulgaris (Xu et al., 2008). In Lotus japonicus, the artificial over-expression of the white clover cryptic partitivirus-1 (WCCV-1) coat protein (CP) gene, which is also a member of the family Partitiviridae, inhibited root nodule formation (Nakatsukasa-Akune et al., 2005). Although one could debate on the beneficial effects, these findings could indicate, albeit speculatively, that a latent infection with WCCV-1 suppresses excessive root nodule formation that otherwise would disrupt the growth of plants. Phaseolus vulgaris endornavirus (PvEV)-infected common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) cv. Black Turtle Soup exhibits obvious beneficial physiological traits without visible pathogenic effects (Table 3) (Khankhum and Valverde, 2018). PvEV-infected plants exhibit faster seed germination, a longer radicle and pods, higher carotene content, and higher 100-seed weight (Khankhum and Valverde, 2018). Recently, cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) strain Ho (CMV[Ho]) has been isolated from asymptomatic Arabidopsis halleri, a perennial wild plant (Takahashi et al. in review). A. halleri is latently infected with CMV(Ho), and the virus has spread systemically. When this strain was inoculated on A. thaliana, the plants were persistently infected with CMV(Ho). CMV(Ho)-infected plants exhibited heat and drought tolerance and had promoted main root growth but suppressed lateral root development (Table 3). Furthermore, latent infection of Solanum lycopersicum cultivar M82 with southern tomato virus (STV) increased the plant height, production of fruit, and germination rate of seeds (Fukuhara et al., 2019). In another recent study (Safari et al., 2019), latent infection of Capsicum annuum by the partitivirus pepper cryptic virus 1 (PVC-1) interestingly appeared to deter aphids. This contrasted with studies in which acute infections with cucumber mosaic virus (CMV) attracted aphids to promote and facilitate the spread of CMV. The relation between PVC-1 and pepper thus appears to be beneficial, as it may protect the host from aphids transmitting acute viruses and aphid herbivory.

Altogether, it has become clear that virus infections, irrespective of whether acute or latent, can provide beneficial effects to host plants. While the underlying mechanisms leading to those beneficial effects have not yet been widely studied, it is not unlikely that these may be similar for acute and latent/persistent infections.

A growing number of studies indicate the widespread nature of EVEs, including their presence in the genomes of various plant species (Holmes, 2011; Feschotte and Gilbert, 2012; Aiewsakun and Katzourakis, 2015). Although EVEs only lead to a viral infection in a few cases in plants, their presence has also been linked to beneficial effects. A study by Staginnus et al. (2007) demonstrated that cultivated tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and a wild relative (S. habrochaites) both contained tomato EVEs with high sequence similarity, likely derived from the same pararetrovirus (LycEPRV). While the pathogenicity of LycEPRVs could not be demonstrated, transcripts derived from multiple LycEPRV loci and short RNAs complementary to LycEPRVs were detected in healthy plants and became elevated in abundance upon infection with heterologous viruses encoding suppressors of post-transcriptional gene silencing (Staginnus et al., 2007). This observation supports the idea that transcriptionally expressed EVEs may contribute to antiviral defense responses.

Although EVEs are thought to represent viral relics from the past resulting from a horizontal gene transfer (HGT) event following a viral infection, studies, as described above, indicate that EVEs can be responsive and may contribute to pathogenicity or virus resistance in the host (Bertsch et al., 2009). Whether viral integration into host genomes is ultimately of net benefit or harm to the host remains to be determined.

To date, most studies of plant viruses have focused on acute infection of cultivated crop plants. Many wild (non-cultivated) host plants are often asymptomatically/latently infected with viruses, and it is tempting to assume that this is the result of a natural evolution with benefits for the virus in terms of survival and dissemination and for the plant hosts in terms of survival and resilience to (a)biotic stressors.

Understanding the biology of latent infections is not only of scientific interest; the knowledge generated might also contribute to future exploitation in cultivated crops and be related to beneficial effects, e.g., increased resilience to (a)biotic stress factors.

Whether latent virus infections result from (partial) genome integration of viral sequences into the host genome, leading to EVEs, remains a matter of debate. However, support for the function of EVEs, and of the RNAi machinery, in the development of latent infections is being provided by recent studies in which persistence of RNA viruses in Drosophila was observed to result from reverse transcription and endogenization (or presence as episomal elements) of viral copy DNA (vDNA) sequences. Transcripts from those sequences were shown to be processed by the RNAi machinery, which inhibited viral replication (Goic et al., 2013). Application of reverse transcriptase inhibitors prevented the establishment of viral persistence, and, instead, lethal acute infections were observed. Following this study, more cases of the persistence of RNA viruses in insects were investigated and demonstrated to involve reverse transcription into vDNA (Goic et al., 2016; Nag et al., 2016). Latent infections, but also integrations of entire copies of a full-length viral genome, present a major risk toward cultivated crops due to the possibility of these viruses/EVEs becoming activated and giving rise to acute infections. A well-studied example of EVE-activation relates to endogenous BSV (eBSV) in hybrid banana (Iskra-Caruana et al., 2010). Interestingly, a recent study has successfully applied CRISPR/Cas9-mediated editing of the eBSV sequences and prevented proper transcription and activation into infectious particles (Tripathi et al., 2019). This not only paves the way to use hybrids containing dormant but activated infectious viral genome copies but also to use these inactivated hybrids in breeding programs to maximally exploit the potential beneficial effects of EVEs.

How can it be explained that cultivated agricultural crops seem to suffer more from viral disease symptoms, while their wild relatives/non-cultivated crops do not but seem more often to contain latent infections? Maybe this view is not correct, since plant virologists have so far been more interested in viruses causing disease and reducing crop yields and not those that do not cause harm (latent infections) or involve non-cultivated crops of no economic importance. On the other hand, if this view is correct, do agricultural crops suffer from viral disease more because they more often grown in monocultures that support the rapid spread of insect vector infestations into the entire outstanding crop, while non-cultivated crops are more resilient and protected due to a more natural balanced ecosystem? Or is there also an involvement of genetic traits, present in wild/non-cultivated crops but lost from cultivated crops during breeding for fast growth and high yields, that support the establishment of latent infections and result from millions of years of evolution? In this perspective, it is interesting to note that endornaviruses, which are normally found in persistent infections, have been observed in many different important crops but are only observed at a very low rate in wild plants. Although endornaviruses are not associated with visible pathogenic effects, their presence correlates with, e.g., faster seed germination, longer bean pods, higher seed weight, etc. (Fukuhara, 2019; Herschlag et al., 2019). Hence, it is very likely that endornaviruses have been positively selected for during breeding for economically important traits, but they rely on certain host factors to maintain their persistence and prevent viral disease. The absence of endornavirus from Oryza knocked down for certain components of the RNAi pathway (RDR or DCL) provided support for the involvement of the host cellular RNAi machinery in the maintenance of a persistent endornavirus infection (Urayama et al., 2010).

While many questions remain to be answered, e.g., the role of EVEs and/or RNAi in the establishment of persistence, studying latent infections in (non-cultivated) plants will be one of the challenges for the future (Watanabe et al., 2019). Further research is required not only to help understand this phenomenon but also to identify genetical traits that could keep viruses in a more dormant state while maintaining maximal benefits toward the host and suppressing negative effects from (a)biotic stressors.

HT and RK contributed substantially to the conception and design of this review article. HT, RK, TF, and HK co-wrote the manuscript. TF and HK reviewed the manuscript before submission for its intellectual content. All authors gave final approval of the published version.

This study was supported by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) (19H02953) and Core-to-Core Program, A. Advanced Research Networks entitled “Establishment of international agricultural immunology research-core for a quantum improvement in food safety” from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (JSPS). This study was also supported by grants for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Science, Sports, and Technology (MEXT) of Japan (16H06429, 16K21723, and 16H06435).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Agüero, J., Gómez-Aix, C., Sempere, R. N., García-Villalba, J., García-Núñez, J., Hernando, Y., et al. (2018). Stable and broad spectrum cross-protection against pepino mosaic virus attained by mixed infection. Front. Plant Sci. 9:1810. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01810

Aiewsakun, P., and Katzourakis, A. (2015). Endogenous viruses: connecting recent and ancient viral evolution. Virology 479-480, 26–37. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.011

Alexander, H. M., Bruns, E., Schebor, H., and Malmstrom, C. M. (2017). Crop-associated virus infection in a native perennial grass: reduction in plant fitness and dynamic patterns of virus detection. J. Ecol. 105, 1021–1031. doi: 10.1111/1365-2745.12723

Ashby, M. K., Warry, A., Bejarano, E. R., Khashoggi, A., Burrell, M., and Lichtenstein, C. P. (1997). Analysis of multiple copies of geminiviral DNA in the genome of four closely related Nicotiana species suggest a unique integration event. Plant Mol. Biol. 35, 313–321.

Aus dem Siepen, M., Pohl, J. O., Koo, B. J., Wege, C., and Jeske, H. (2005). Poinsettia latent virus is not a cryptic virus, but a natural polerovirus-sobemovirus hybrid. Virology 336, 240–250. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2005.03.020

Barba, M., Czosnek, H., and Hadidi, A. (2014). Historical perspective, development and applications of next-generation sequencing in plant virology. Viruses 6, 106–136. doi: 10.3390/v6010106

Barton, E. S., White, D. W., Cathelyn, J. S., Brett-McClellan, K. A., Engle, M., Diamond, M. S., et al. (2007). Herpesvirus latency confers symbiotic protection from bacterial infection. Nature 447, 326–330. doi: 10.1038/nature05762

Bejarano, E. R., Khashoggi, A., Witty, M., and Lichtenstein, C. (1996). Integration of multiple repeats of geminiviral DNA into the nuclear genome of tobacco during evolution. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 93, 759–764. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.2.759

Bem, F., and Murant, A. F. (1979). Host range, purification and serological properties of heracleum latent virus. Ann. Appl. Biol. 92, 243–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1979.tb03870.x

Bernardo, P., Golden, M., Akram, M., Naimuddin Nadarajan, N., Fernandez, E., Granier, M., et al. (2013). Identification and characterization of a highly divergent geminivirus: evolutionary and taxonomic implications. Virus Res. 177, 35–45. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2013.07.006

Bernardo, P., Muhire, B., Francois, S., Deshoux, M., Hartnady, P., Farkas, K., et al. (2016). Molecular characterization and prevalence of two capulaviruses: Alfalfa leaf curl virus from France and Euphorbia caput-medusae latent virus from South Africa. Virology 493, 142–153. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.03.016

Bertsch, C., Beuve, M., Dolja, V. V., Wirth, M., Pelsy, F., Herrbach, E., et al. (2009). Retention of the virus-derived sequences in the nuclear genome of grapevine as a potential pathway to virus resistance. Biol. Direct 4:21. doi: 10.1186/1745-6150-4-21

Boccardo, G., Lisa, V., Luisoni, E., and Milne, R. G. (1987). Cryptic plant viruses. Adv. Virus Res. 32, 171–214. doi: 10.1016/s0065-3527(08)60477-7

Boccardo, G., Milne, R. G., Luisoni, E., Lisa, V., and Accotto, G. P. (1985). Three seedborne cryptic viruses containing double-stranded RNA isolated from white clover. Virology 147, 29–40. doi: 10.1016/0042-6822(85)90224-7

Bos, L., Huttinga, H., and Maat, D. Z. (1980). Spinach latent virus, a new ilarvirus seed-borne in Spinacia oleracea. Netherlands J. Plant Pathol. 86, 79–98. doi: 10.1007/bf01974337

Bousalem, M., Douzery, E. J. P., and Seal, S. E. (2008). Taxonomy, molecular phylogeny and evolution of plant reverse transcribing viruses (family Caulimoviridae) inferred from full-length genome and reverse transcriptase sequences. Arch. Virol. 153, 1085–1102. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0095-9

Boyd, E. F. (2012). Bacteriophage-encoded bacterial virulence factors and phage-pathogenicity island interactions. Adv. Virus Res. 82, 91–118. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394621-8.00014-5

Brüssow, H., Canchaya, C., and Hardt, W. D. (2004). Phages and the evolution of bacterial pathogens: from genomic rearrangements to lysogenic conversion. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 68, 560–602. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.68.3.560-602.2004

Bueso, E., Serrano, R., Pallás, V., and Sánchez-Navarro, J. A. (2017). Seed tolerance to deterioration in arabidopsis is affected by virus infection. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 116, 1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.04.020

Chabannes, M., and Iskra-Caruana, M. L. (2013). Endogenous pararetroviruses - a reservoir of virus infection in plants. Curr. Opin. Virol. 3, 615–620. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2013.08.012

Chen, S., and Kishima, Y. (2016). Endogenous pararetroviruses in rice genomes as a fossil record useful for the emerging field of palaeovirology. Mol. Plant Pathol. 17, 1317–1320. doi: 10.1111/mpp.12490

Chen, S., Liu, R., Koyanagi, K. O., and Kishima, Y. (2014). Rice genomes recorded ancient pararetrovirus activities: virus genealogy and multiple origins of endogenization during rice speciation. Virology 471, 141–152. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2014.09.014

Chiba, S., Kondo, H., Tani, A., Saisho, D., Sakamoto, W., Kanematsu, S., et al. (2011). Widespread endogenization of genome sequences of non-retroviral RNA viruses into plant genomes. PLoS Pathog. 7:e1002146. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002146

Chu, H., Jo, Y., and Cho, W. K. (2014). Evolution of endogenous non-retroviral genes integrated into plant genomes. Curr. Plant Biol. 1, 55–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cpb.2014.07.002

Diop, S. I., Geering, A. D. W., Alfama-Depauw, F., Loaec, M., Teycheney, P. Y., and Maumus, F. (2018). Tracheophyte genomes keep track of the deep evolution of the Caulimoviridae. Sci. Rep. 8:572. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-16399-x

Edson, K. M., Vinson, S. B., Stoltz, D. B., and Summers, M. D. (1981). Virus in a parasitoid wasp: suppression of the cellular immune response in the parasitoid’s host. Science 211, 582–583. doi: 10.1126/science.7455695

Eid, S., and Pappu, H. R. (2014). Expression of endogenous para-retroviral genes and molecular analysis of the integration events in its plant host Dahlia variabilis. Virus Genes 48, 153–159. doi: 10.1007/s11262-013-0998-8

Félix, M. R., Joana, M. S., Cardoso, J. M. S., Oliveira, S., and Clara, M. I. E. (2007). Biological and molecular characterization of Olive latent virus 1. Plant Viruses 1, 170–177.

Feschotte, C., and Gilbert, C. (2012). Endogenous viruses: insights into viral evolution and impact on host biology. Nat. Rev. Genet. 13, 283–296. doi: 10.1038/nrg3199

Fraile, A., McLeish, M. J., Pagán, I., González-Jara, P., Piñero, D., and García-Arenal, F. (2017). Environmental heterogeneity and the evolution of plant-virus interactions: viruses in wild pepper populations. Virus Res. 241, 68–76. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2017.05.015

Fukuhara, T. (2019). Endornaviruses: persistent dsRNA viruses with symbiotic properties in diverse eukaryotes. Virus Genes 55, 165–173. doi: 10.1007/s11262-019-01635-5

Fukuhara, T., Tabara, M., Koiwa, H., and Takahashi, H. (2019). Effect on tomato plants of asymptomatic infection with southern tomato virus. Arch. Virol. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04436-1 [Epub ahead of print].

Gallitelli, D., Martelli, G. P., and Di Franco, A. (1989). Grapevine Algerian latent virus, a newly recognized Tombusvirus. Phytoparasitica 17, 61–62.

Gallitelli, D., and Savino, V. (1985). Olive latent virus 1, an isometric virus with a single RNA species isolated from olive in Apulia, Southern Italy. Ann. Appl. Biol. 106, 295–303. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1985.tb03119.x

Geering, A. D. W., Maumus, F., Copetti, D., Choisne, N., Zwickl, D. J., Zytnicki, M., et al. (2014). Endogenous florendoviruses are major components of plant genomes and hallmarks of virus evolution. Nat. Commun. 5:5269. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6269

Geering, A. D. W., Scharaschkin, T., and Teycheney, P.-Y. (2010). The classification and nomenclature of endogenous viruses of the family Caulimoviridae. Arch. Virol. 155, 123–131. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0488-4

Goic, B., Stapleford, K. A., Frangeul, L., Doucet, A. J., Gausson, V., Blanc, H., et al. (2016). Virus-derived DNA drives mosquito vector tolerance to arboviral infection. Nat. Commun. 7:12410. doi: 10.1038/ncomms12410

Goic, B., Vodovar, N., Mondotte, J. A., Monot, C., Frangeul, L., Blanc, H., et al. (2013). RNA-mediated interference and reverse transcription control the persistence of RNA viruses in the insect model Drosophila. Nat. Immunol. 14, 396–403. doi: 10.1038/ni.2542

Grimová, L., and Ryšánek, P. (2012). Apricot latent virus - review. Hort. Sci. 39, 144–148. doi: 10.17221/260/2011-hortsci

Groen, S. C., Jiang, S., Murphy, A. M., Cunniffe, N. J., Westwood, J. H., Davey, M. P., et al. (2016). Virus infection of plants alters pollinator preference: a payback for susceptible hosts? PLoS Pathog. 12:e1005790. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005906

Guy, P. L., and Sward, R. J. (1991). Ryegrass mosaic and ryegrass cryptic virus in Australia. Acta Phytopathol. Ent. Hungarica 26, 199–202.

Harper, G., Hull, R., Lockhart, B., and Olszewski, N. (2002). Viral sequences integrated into plant genomes. Annu. Rev. Phytopathol. 40, 119–136. doi: 10.1146/annurev.phyto.40.120301.105642

Harper, G., Osuji, J. O., Heslop-Harrison, J. S., and Hull, R. (1999). Integration of banana streak badnavirus into the Musa genome: molecular and cytogenetic evidence. Virology 255, 207–213. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9581

Harth, J. E., Ferrari, M. J., Helms, A. M., Tooker, J. F., and Stephenson, A. G. (2018). Zucchini yellow mosaic virus infection limits establishment and severity of powdery mildew in wild populations of Cucurbita pepo. Front. Plant Sci. 9:792. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2018.01815

Herschlag, R., Escalante, C., de Souto, E. R., Khankhum, S., Okada, R., and Valverde, R. A. (2019). Occurrence of putative endornaviruses in non-cultivated plant species in South Louisiana. Arch. Virol. 164, 1863–1868. doi: 10.1007/s00705-019-04270-5

Hohn, T., Richert-Poeggeler, K. R., Staginnus, C., Harper, G., Schwarzacher, T., Teo, C. H., et al. (2008). “Evolution of integrated plant viruses,” in Plant Virus Evolution, ed. M. J. Roossinck (Berlin: Springer), 53–81. doi: 10.1007/978-3-540-75763-4_4

Holmes, E. C. (2011). The evolution of endogenous viral elements. Cell Host Microbe 10, 368–377. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2011.09.002

Hull, R. (2014). Plant Virology, 5th Edn. Cambridge, MA: Academic Press. doi: 10.1016/C2010-0-64974-1

Huth, W., Lesemann, D. E., Götz, R., and Vetten, H. J. (1995). Some properties of Lolium latent virus. Agronomie 15:508. doi: 10.1094/PD-90-0528C

Iskra-Caruana, M. L., Baurens, F. C., Gayral, P., and Chabannes, M. (2010). A four-partner plant-virus interaction: enemies can also come from within. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 23, 1394–1402. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-05-10-0107

Jakowitsch, J., Mette, M. F., van der Winden, J., Matske, M. A., and Matske, A. J. M. (1999). Integrated pararetroviral sequences define a unique class of dispersed repetitive DNA in plants. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 96, 13241–13246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.96.23.13241

Kamitani, M., Nagano, A. J., Honjo, M. N., and Kudoh, H. (2016). RNA-Seq reveals virus–virus and virus–plant interactions in nature. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 92:fiw176. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiw176

Khankhum, S., and Valverde, R. A. (2018). Physiological traits of endornavirus-infected and endornavirus-free common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris) cv Black Turtle Soup. Arch. Virol. 163, 1051–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00705-018-3702-4

Koganezawa, H., Yanase, H., Ochiai, M., and Sakuma, T. (1985). Anisometric virus-like particle isolated from russet ring-diseased apple. Ann. Phytopathol. Soc. Japan 51:363.

Kostin, V. D., and Volkov, Y. G. (1976). Some properties of the virus affecting Plantago asiatica L. Virusnye Bolezni Rastenij Dalnego Vostoka 25, 205–210.

Kreuze, J. F., Perez, A., Untiveros, M., Quispe, D., Fuentes, S., Barker, I., et al. (2009). Complete viral genome sequence and discovery of novel viruses by deep sequencing of small RNAs: a generic method for diagnosis, discovery and sequencing of viruses. Virology 388, 1–7. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2009.03.024

Kunii, M., Kanda, M., Nagano, H., Uyeda, I., Kishima, Y., and Sano, Y. (2004). Reconstruction of putative DNA virus from endogenous rice tungro bacilliform virus-like sequences in the rice genome: implications for integration and evolution. BMC Genomics 5:80. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-5-80

Li, C., Yoshikawa, N., Takahashi, T., Ito, T., Yoshida, K., and Koganezawa, H. (2000). Nucleotide sequence and genome organization of apple latent spherical virus: a new virus classified into the family Comoviridae. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 541–547. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-2-541

Lister, R. M. (1964). Strawberry latent ringspot: a new nematode-bome virus. Ann. Appl. Biol. 54, 167–176. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1964.tb01180.x

Little, T. J., Shuker, D. M., Colegrave, N., Day, T., and Graham, A. L. (2010). The coevolution of virulence: tolerance in perspective. PLoS Pathog. 6:e1001006. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1001006

Liu, H., Fu, Y., Jiang, D., Li, G., Xie, J., Cheng, J., et al. (2010). Widespread horizontal gene transfer from double-stranded RNA viruses to eukaryotic nuclear genomes. J. Virol. 84, 11879–11887. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00955-10

Liu, H., Fu, Y., Li, B., Yu, X., Xie, J., Cheng, J., et al. (2011). Widespread horizontal gene transfer from circular single-stranded DNA viruses to eukaryotic genomes. BMC Evol. Biol. 11:276. doi: 10.1186/1471-2148-11-276

Liu, H., Fu, Y., Xie, J., Cheng, J., Ghabrial, S. A., Li, G., et al. (2012). Discovery of novel dsRNA viral sequences by in silico cloning and implications for viral diversity, host range and evolution. PLoS One 7:e42147. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042147

Lockhart, B. E., Menke, J., Dahal, G., and Olszewski, N. E. (2000). Characterization and genomic analysis of Tobacco vein clearing virus, a plant pararetrovirus that is transmitted vertically and related to sequences integrated in the host genome. J. Gen. Virol. 81, 1579–1585. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-81-6-1579

Lovato, A., Faoro, F., Gambino, G., Maffi, D., Bracale, M., Polverari, A., et al. (2014). Construction of a synthetic infectious cDNA clone of Grapevine algerian latent virus (GALV-Nf) and its biological activity in Nicotiana benthamiana and grapevine plants. Virol. J. 11:186. doi: 10.1186/1743-422X-11-186

Malmstrom, C. M., and Alexander, H. M. (2016). Effects of crop viruses on wild plants. Curr. Opin. Virol. 19, 30–36. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2016.06.008

Maroon-Lango, C., Hammond, J., Warnke, S., Li, R., and Mock, R. (2006). First report of Lolium latent virus in ryegrass in the USA. Plant Dis. 90:528. doi: 10.1094/PD-90-0528C

Márquez, L. M., Redman, R. S., Rodriguez, R. J., and Roossinck, M. J. (2007). A virus in a fungus in a plant: three-way symbiosis required for thermal tolerance. Science 315, 513–515. doi: 10.1126/science.1136237

Martelli, G. P., and Jelkmann, W. (1998). Foveavirus, a new plant virus genus. Arch. Virol. 143, 1245–1249. doi: 10.1007/s007050050372

Martin, R. R., Zhou, J., and Tzanetakis, I. E. (2011). Blueberry latent virus: an amalgam of the Partitiviridae and Totiviridae. Virus Res. 155, 175–180. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2010.09.020

Matzke, M., Gregor, W., Mette, M. F., Aufsatz, W., Kanno, T., Jakowitsch, J., et al. (2004). Endogenous pararetroviruses of allotetraploid Nicotiana tabacum and its diploid progenitors, N. sylvestris and N. tomentosiformis. Biol. J. Lin. Soc. 82, 627–638. doi: 10.1111/j.1095-8312.2004.00347.x

Mauck, K. E., De Moraes, C. M., and Mescher, M. C. (2010). Deceptive chemical signals induced by a plant virus attract insect vectors to inferior hosts. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 3600–3605. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907191107

Mazyadr, A. A., Khederr, A. A., El-Attart, A. K., Amer, W., Ismail, M. H., and Amal, A. F. (2014). Characterization of strawberry latent ringspot virzs (SLRSV) on strawberry in Egypt. Egypt. J. Virol. 11, 229–235.

Min, B.-E., Feldman, T. S., Ali, A., Wiley, G., Muthukumar, V., Roe, B. A., et al. (2012). Molecular characterization, ecology, and epidemiology of a novel Tymovirus in Asclepias viridis from Oklahoma. Phytopathology 102, 166–176. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO-05-11-0154

Morsy, M. R., Oswald, J., He, J., Tang, Y., and Roossinck, M. J. (2010). Teasing apart a three-way symbiosis: transcriptome analyses of Curvularia protuberata in response to viral infection and heat stress. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 401, 225–230. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2010.09.034

Murad, L., Bielawski, J. P., Matyasek, R., Kovarik, A., Nichols, R. A., Leitch, A. R., et al. (2004). The origin and evolution of geminivirus-related DNA sequences in Nicotiana. Heredity 92, 352–358. doi: 10.1038/sj.hdy.6800431

Nag, D. K., Brecher, M., and Kramer, L. D. (2016). DNA forms of arboviral RNA genomes are generated following infection in mosquito cell cultures. Virology 498, 164–171. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2016.08.022

Nakatsukasa-Akune, M., Yamashita, K., Shimoda, Y., Uchiumi, T., Abe, M., Aoki, T., et al. (2005). Suppression of root nodule formation by artificial expression of the TrEnodDR1 (coat protein of White clover cryptic virus 1) gene in Lotus japonicus. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 18, 1069–1080. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-18-1069

Natsuaki, T., Natsuaki, K. T., Okuda, S., Teranaka, M., Milne, R. G., Boccardo, G., et al. (1986). Relationships between the cryptic and temperate viruses of alfalfa, beet and white clover. Intervirology 25, 69–75. doi: 10.1159/000149658

Ndowora, T., Dahal, G., LaFleur, D., Harper, G., Hull, R., Olszewski, N. E., et al. (1999). Evidence that badnavirus infection in Musa can originate from integrated pararetroviral sequences. Virology 255, 214–220. doi: 10.1006/viro.1998.9582

Nemchinov, L., and Hadidi, A. (1998). Apricot latent virus: a novel stone fruit pathogen and its relationship to apple stem pitting virus. Acta Horti. 472, 159–173.

Nemchinov, L. G., Shamloul, A. M., Zemtchik, E. Z., Verderevskaya, T. D., and Hadidi, A. (2000). Apricot latent virus: a new species in the genus Foveavirus. Arch. Virol. 145, 1801–1813. doi: 10.1007/s007050070057

Nuss, D. L. (2008). “Hypoviruses,” in Encyclopedia of Virology, eds A. Granoff and R. Webster (Amsterdam: Elsevier), 580–585. doi: 10.1016/b978-012374410-4.00406-4

Owens, R. A., Flores, R., Di Serio, F., Li, S., Pallas, V., and Randles, J. W. (2012). Virus Taxonomy: Ninth Report of the International Committee on Taxonomy of Viruses. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Ozeki, J., Takahashi, S., Komatsu, K., Kagiwada, S., Yamashita, K., Mori, T., et al. (2006). A single amino acid in the RNA dependent RNA polymerase of Plantago asiatica mosaic virus contributes to systemic necrosis. Arch. Virol. 151, 2067–2075. doi: 10.1007/s00705-006-0766-3

Pagán, I., González-Jara, P., Moreno-Letelier, A., Rodelo-Urrego, M., Fraile, A., Piñero, D., et al. (2012). Effect of biodiversity changes in disease risk: exploring disease emergence in a plant-virus system. PLoS Pathog. 8:e1002796. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002796

Pooggin, B. B. (2018). Small RNA-Omics for plant virus identification, virome reconstruction, and antiviral defense characterization. Front. Microbiol. 9:2779. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.02779

Råberg, L. (2014). How to live with the enemy: understanding tolerance to parasites. PLoS Biol. 12:e1001989. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.1001989

Redman, R. S., Sheehan, K. B., Stout, R. G., Rodriguez, R. J., and Henson, J. M. (2002). Thermotholerance generated by plant/fungal symbiosis. Science 298:1581. doi: 10.1126/science.1072191

Richert-Pöggeler, K. R., and Minarovits, J. (2014). Diversity of latent plant-virus interactions and their impact on the virosphere. Plant Virus Host Interact. 14, 263–275. doi: 10.1016/b978-0-12-411584-2.00014-7

Richert-Pöggeler, K. R., Noreen, F., Schwarzacher, T., Harper, G., and Hohn, T. (2003). Induction of infectious Petunia vein clearing (pararetro) virus from endogenous provirus in petunia. EMBO J. 22, 4836–4845. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg443

Richins, R. D., and Shepherd, R. J. (1986). Horseradish latent virus, a new member of the Caulimovirus group. Phytopathology 76, 749–754.

Rodríguez-Nevado, C., Montes, N., and Pagán, I. (2017). Ecological factors affecting infection risk and population genetic diversity of a novel potyvirus in its native wild ecosystem. Front. Plant Sci. 8:1958. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2017.01958

Roossinck, M. J. (2005). Symbiosis versus competition in plant virus evolution. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 917–924. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1285

Roossinck, M. J. (2010). Lifestyles of plant viruses. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 365, 1899–1905. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2010.0057

Roossinck, M. J. (2011a). The big unknown: plant virus biodiversity. Curr. Opin. Virol. 1, 63–67. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2011.05.022

Roossinck, M. J. (2011b). The good viruses: viral mutualistic symbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 9, 99–108. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2491

Roossinck, M. J. (2012a). “Persistent plant viruses: molecular hitchhikers or epigenetic elements,” in In Viruses: Essential Agents of Life, ed. G. Witzany (New York, NY: Springer), 177–186. doi: 10.1007/978-94-007-4899-6_8

Roossinck, M. J. (2012b). Plant virus metagenomics: biodiversity and ecology. Annu. Rev. Genet. 46, 359–369. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-110711-155600

Roossinck, M. J. (2013). Plant virus ecology. PLoS Pathog. 9:e1003304. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1003304

Roossinck, M. J. (2015a). Metagenomics of plant and fungal viruses reveals an abundance of persistent lifestyles. Front. Microbiol. 12:767. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00767

Roossinck, M. J. (2015b). Move over, bacteria! Viruses make their mark as mutualistic microbial symbionts. J. Virol. 89, 6532–6535. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02974-14

Roossinck, M. J., and Garcia-Arenal, F. (2015). Ecosystem simplification, biodiversity loss and plant virus emergence. Curr. Opin. Virol. 10, 56–62. doi: 10.1016/j.coviro.2015.01.005

Roossinck, M. J., Sabanadzovic, S., Okada, R., and Valverde, R. A. (2011). The remarkable evolutionary history of endornaviruses. J. Gen. Virol. 92, 2674–2678. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.034702-0

Rubino, L., and Russo, M. (1997). Molecular analysis of the pothos latent virus genome. J. Gen. Virol. 78, 1219–1226. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-78-6-1219

Sabanadzovic, S., Valverde, R. A., Brown, J. K., Martin, R. R., and Tzanetakis, I. E. (2009). Southern tomato virus: the link between the families Totiviridae and Partitiviridae. Virus Res. 140, 130–137. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2008.11.018

Safari, M., Ferrari, M. J., and Roossinck, M. J. (2019). Manipulation of aphid behavior by a persistent plant virus. J. Virol. 93:e01781-18. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01781-18

Schmelzer, K. (1969). Strawberry latent ringspot virus in Euonymous, Acacia, and Aesculus. Phytopathol. Z. 66, 1–24.

Shapiro, L. R., Salvaudon, L., Mauck, K. E., Pulido, H., DeMoraes, C. M., Stephenson, A. G., et al. (2013). Disease interactions in a shared host plant: effects of pre-existing viral infection on cucurbit plant defense responses and resistance to bacterial wilt disease. PLoS One 8:e77393. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0077393

Shates, T. M., Sun, P., Malmstrom, C. M., Dominguez, C., and Mauck, K. E. (2019). Addressing research needs in the field of plant virus ecology by defining knowledge gaps and developing wild dicot study systems. Front. Microbiol. 9:3305. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.03305

Solovyev, A. G., Novikov, V. K., Merits, A., Savenkov, E. I., Zelenina, D. A., Tyulkina, L. G., et al. (1994). Genome characterization and taxonomy of Plantago asiatica mosaic potexvirus. J. Gen. Virol. 75, 259–267. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-75-2-259

Song, D., Cho, W. K., Park, S.-H., Jo, Y., and Kim, K.-H. (2013). Evolution of and horizontal gene transfer in the Endornavirus genus. PLoS One 8:e64270. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064270

Staginnus, C., Gregor, W., Mette, M. F., Teo, C. H., Borroto-Fernández, E. G., da Câmara Machado, M. L., et al. (2007). Endogenous pararetroviral sequences in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) and related species. BMC Plant Biol. 7:24. doi: 10.1186/1471-2229-7-24

Staginnus, C., Iskra-Caruana, M., Lockhart, B., Hohn, T., and Richert-Pöggeler, K. R. (2009). Suggestions for a nomenclature of endogenous pararetroviral sequences in plants. Arch. Virol. 154, 1189–1193. doi: 10.1007/s00705-009-0412-y

Staginnus, C., and Richert-Pöggeler, K. R. (2006). Endogenous pararetroviruses: two-faced travelers in the plant genome. Trends Plant Sci. 11, 485–491. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2006.08.008

Stobbe, A. H., and Roossinck, M. J. (2014). Plant virus metagenomics: what we know and why we need to know more. Front. Plant Sci. 5:150. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2014.00150

Susi, H., Filloux, D., Frilander, M. J., Roumagnac, P., and Laine, A.-L. (2019). Diverse and variable virus communities in wild plant populations revealed by metagenomic tools. Peer J. 7:e6140. doi: 10.7717/peerj.6140

Susi, H., Laine, A. L., Filloux, D., Kraberger, S., Farkas, K., Bernardo, P., et al. (2017). Genome sequences of a capulavirus infecting Plantago lanceolata in the Åland archipelago of Finland. Arch. Virol. 162, 2041–2045. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3298-0

Tang, J., Ward, L. I., and Clover, G. R. G. (2013). The diversity of strawberry latent ringspot virus in New Zealand. Plant Dis. 97, 662–667. doi: 10.1094/PDIS-07-12-0703-RE

Tanne, E., and Sela, I. (2005). Occurrence of a DNA sequence of a non-retro RNA virus in a host plant genome and its expression: evidence for recombination between viral and host RNAs. Virology 332, 614–622. doi: 10.1016/j.virol.2004.11.007

Teycheney, P.-Y., and Geering, A. D. W. (2011). “Endogenous viral sequences in plant genomes,” in Recent Advances in Plant Virology, eds C. Caranta, M. A. Aranda, M. Tepfer, and J. J. López-Moya (Caister: Academic Press), 343–362.

Tripathi, J. N., Ntui, V. O., Ron, M., Muiruri, S. K., Britt, A., and Tripathi, L. (2019). CRISPR/Cas9 editing of endogenous banana streak virus in the B genome of Musa spp. overcomes a major challenge in banana breeding. Commun. Biol. 2:46. doi: 10.1038/s42003-019-0288-7

Urayama, S., Moriyama, H., Aoki, N., Nakazawa, Y., Okada, R., Kiyota, E., et al. (2010). Knock-down of OsDCL2 in rice negatively affects maintenance of the endogenous dsRNA virus, Oryza sativa endornavirus. Plant Cell Physiol. 51, 58–67. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcp167

Vaira, A. M., Maroon-Lango, C. J., and Hammond, J. (2008). Molecular characterization of Lolium latent virus, proposed type member of a new genus in the family Flexiviridae. Arch. Virol. 153, 1263–1270. doi: 10.1007/s00705-008-0108-8

Valverde, R. A. (1985). Spring beauty latent virus: a new member of the bromovirus group. Phytopathology 75, 395–398. doi: 10.1094/Phyto-75-395

van Molken, T., de Caluwe, H., Hordijk, C. A., Leon-Reyes, A., Snoeren, T. A., van Dam, N. M., et al. (2012). Virus infection decreases the attractiveness of white clover plants for a non-vectoring herbivore. Oecologia 170, 433–444. doi: 10.1007/s00442-012-2322-z

Varsani, A., Roumagnac, P., Fuchs, M., Navas-Castillo, J., Moriones, E., Idris, A., et al. (2017). Capulavirus and Grablovirus: two new genera in the family Geminiviridae. Arch. Virol. 162, 1819–1831. doi: 10.1007/s00705-017-3268-6

Watanabe, T., Suzuki, N., Tomonaga, K., Sawa, H., Matsuura, Y., Kawaguchi, Y., et al. (2019). Neo-virology: the raison d’etre of viruses. Virus Res. 274:197751. doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2019.197751

Westwood, J. H., McCann, L., Naish, M., Dixon, H., Murphy, A. M., Stancombe, M. A., et al. (2013). A viral RNA silencing suppressor interferes with abscisic acid-mediated signalling and induces drought tolerance in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant Pathol. 14, 158–170. doi: 10.1111/j.1364-3703.2012.00840.x

Wren, J. D., Roossinck, M. J., Nelson, R. S., Scheets, K., Palmer, M. W., and Melcher, U. (2006). Plant virus biodiversity and ecology. PLoS Biol. 4:e80. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0040080

Xie, W. S., Antoniw, J. F., White, R. F., and Jolliffee, T. H. (1994). Effects of beet cryptic virus infection on sugar beet in field trials. Ann. Appl. Biol. 124, 451–459. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-7348.1994.tb04150.x

Xu, P., Chen, F., Mannas, J. P., Feldman, T., Sumner, L. W., and Roossinck, M. J. (2008). Virus infection improves drought tolerance. New Phytol. 180, 911–921. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02627.x

Zemtchik, E. Z., and Verderevskaya, T. D. (1993). Latent virus on apricot unknown under Moldavian conditions. Russian Agric. Biol. 3, 130–133.

Keywords: beneficial interactions with plant viruses, endogenous viral elements, latent infection, stress tolerance, plant virus

Citation: Takahashi H, Fukuhara T, Kitazawa H and Kormelink R (2019) Virus Latency and the Impact on Plants. Front. Microbiol. 10:2764. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.02764

Received: 12 August 2019; Accepted: 12 November 2019;

Published: 06 December 2019.

Edited by:

Jesús Navas-Castillo, Institute of Subtropical and Mediterranean Hortofruticultura La Mayora (IHSM), SpainReviewed by:

Israel Pagan, Polytechnic University of Madrid, SpainCopyright © 2019 Takahashi, Fukuhara, Kitazawa and Kormelink. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hideki Takahashi, aGlkZWtpLnRha2FoYXNoaS5kNUB0b2hva3UuYWMuanA=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.