- Department of Medicine, Division of Infectious Diseases, Warren Alpert Medical School of Brown University, Rhode Island Hospital, Providence, RI, United States

Antimicrobial drug discovery against drug-resistant bacteria is an urgent need. Beyond agents with direct antibacterial activity, anti-virulent molecules may also be viable compounds to defend against bacterial pathogenesis. Using a high throughput screen (HTS) that utilized Caenorhabditis elegans infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) strain of MW2, we identified 4-(1,3-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)phenol (BIP). Interestingly, BIP had no in vitro inhibition activity against MW2, at least up to 64 μg/ml. The lack of direct antimicrobial activity suggests that BIP could inhibit bacterial virulence factors. To explore the possible anti-virulence effect of the identified molecule, we first performed real-time PCR to examine changes in virulence expression. BIP was highly active against MRSA virulence factors at sub-lethal concentrations and down-regulated virulence regulator genes, such as agrA and codY. However, the benzimidazole derivatives omeprazole and pantoprazole did not down-regulate virulence genes significantly, compared to BIP. Moreover, the BIP-pretreated MW2 cells were more vulnerable to macrophage-mediated killing, as confirmed by intracellular killing and live/dead staining assays, and less efficient in establishing a lethal infection in the invertebrate host Galleria mellonella (p = 0.0131). We tested the cytotoxicity of BIP against human red blood cells (RBCs), and it did not cause hemolysis at the highest concentration tested (64 μg/ml). Taken together, our findings outline the potential anti-virulence activity of BIP that was identified through a C. elegans-based, whole animal based, screen.

Introduction

Fatal infections from antibiotic-resistant bacteria are predicted to rise and expected to exceed deaths caused by cancer by the year 2050 (de Kraker et al., 2016), therefore putting forth a critical need for novel antibiotics (Zaman et al., 2017). The infection process is a multifaceted process with the interplay between the invading bacteria and host. Most bacterial pathogens rely on virulence factors, inclusive of toxins, adhesins, secreted proteins, secretion systems, lytic enzymes, invasins, etc. to establish an infection (Defoirdt, 2017). Targeting these virulence mechanisms can be a means of thwarting the microbial attack (Wilson et al., 2002).

A possible benefit to developing anti-virulence agents is the potential to reduce antibiotic resistance from overexposure to antibiotic compounds (Hauser et al., 2016). Anti-virulence compounds neither kill nor inhibit bacterial growth, but disable the infection process (Heras et al., 2015; Totsika, 2017). The fundamental principle behind blocking virulence factors is to make the pathogen more vulnerable to host immune responses (Longdon et al., 2015). Currently, anti-virulence compounds present a potentially untapped strategy in controlling or treating bacterial infections.

Virulence factors are already a target exploited by nature to curb microbial infections. Natural products exist that target microbial virulence factors. Examples include garlic, menthol, clove, and black pepper which inhibit enterotoxins, the type III secretion system (T3SS), and biofilm (Maura et al., 2016; Silva et al., 2016). Anti-virulence compounds can also be found among orphaned United States-Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved drugs and existing therapeutic agents by engaging in “drug repurposing” (Rampioni et al., 2017). For example, anthelmintic drug niclosamide was found to have a potential “anti-quorum sensing” activity against the Gram-Negative pathogen Pseudomonas aeruginosa (Imperi et al., 2013). Recently, the FDA approved a therapy that targets virulence factors using immunoglobulins, while other anti-virulence molecules are in preclinical evaluation (Dickey et al., 2017).

In search of new antimicrobial agents, we performed a high throughput screen (HTS) to find compounds that prolong the survival of C. elegans infected with methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (Rajamuthiah et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2018). In this screen, the molecule BIP was identified as a hit. The compound is a benzimidazole derivative linked with phenol. Benzimidazole is a heterocyclic aromatic organic compound consisting of a fusion of benzene and imidazole (Shrivastava et al., 2017) and its derivatives exhibit a diverse biological activity including, anthelminthic, antibacterial, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, etc. (Singh et al., 2012). Because the compound did demonstrate in vitro inhibition activity against the MW2, we hypothesized that BIP exhibits anti-virulence activity.

Materials and Methods

Compound Information

4-(1,3-Dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)phenol (Chembridge # 5534382) (BIP) was purchased from Chembridge (Chembridge Corporation, San Diego, CA, USA). BIP was prepared by dissolving in DMSO (Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA) at 10 mg/ml and diluting as required for experiments. Hits were identified from the screen based on the Z-score. The Z-score was calculated from the ratio of live versus dead worms after treatment with investigational compounds, and the score is defined as the number of standard deviations (SD) by which the investigational compound is separated from the mean using the formula Z = (x − μ)/σ, where x is the raw sample score, μ is the mean of the population, and σ is the standard deviation of the population. Samples with Z > 2σ were considered as hits (Rajamuthiah et al., 2014). Other approved clinical drugs were purchased from Sigma Aldrich.

Bacterial and Nematode Strains

All reference and clinical bacterial strains were from our laboratory collection (Table 1). For all experiments, bacteria were grown at 37°C. S. aureus (MRSA strain MW2) (clinical strains BF 9 and BF 10) agr mutant S. aureus RN 4220, Enterococcus faecium, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Acinetobacter baumannii, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Enterobacter aerogenes, and Candida albicans were grown in tryptic soy broth (TSB) (BD Biosciences, Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA). The C. elegans glp-4(bn2);sek-1(km4) strain was maintained at 15°C on a lawn of Escherichia coli strain HB101 on 10-cm plates, as previously described (Rajamuthiah et al., 2014). The glp-4(bn2) mutation renders the strain unable to produce progeny at 25°C (Beanan and Strome, 1992), and the sek-1(km4) mutation increases sensitivity to several pathogens (Tanaka-Hino et al., 2002), thereby reducing assay time.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing

In vitro, antibiotic susceptibility assays were carried out using a broth microdilution assay using Müller-Hinton broth (BD Biosciences) in 96-well plates (BD Biosciences) with a total assay volume of 100 μl (Wikler, 2006). Two-fold serial dilutions of BIP were prepared over the concentration range 0.01 ̶ 64 μg/ml. The initial bacterial inoculum was adjusted to OD600 = 0.06 and assays were incubated at 35°C for 18 h. To determine the minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), OD600 was measured and visual inspection was made after incubation, and the lowest concentration of test compound that suppressed bacterial growth was reported as the MIC. The choice of medium for C. albicans was RPMI and 103–2.5 × 103 of initial inoculum was used to determine the MIC. The assays were carried out in triplicate.

Time to Kill Assays

The strain MW2 was used to probe the killing effects of BIP, as previously described (Rajamuthiah et al., 2015). The assays were carried out in 10-ml tubes (BD Biosciences) in duplicate. Briefly, log-phase cultures of MW2 were diluted in fresh TSB to a density of 108 cells/ml. BIP was added at sub-lethal concentrations (64, 32 μg/ml), and the tubes were incubated at 37°C with agitation. At periodic intervals, aliquots from each tube were serially diluted in TSB and plated onto tryptic soy agar (TSA, BD Biosciences). CFU was enumerated after overnight incubation at 37°C (Tharmalingam et al., 2017). Gentamicin at 0.5 μg/ml (MIC: 1.0 μg/ml) was used as a control agent.

An independent experiment was carried out to test the hypothesis of post-antibiotic effect. The MW2 cells were treated with BIP (64 μg/ml) for 4 h, and the cells were washed with sterile PBS. The washed cells were suspended in fresh MHB (0.05 OD600) and incubated for 2 h with agitation. After 2 h, the total viable count was enumerated as described earlier in this section.

Human Red Blood Cell Hemolysis

Human erythrocytes (Rockland Immunochemicals, Limerick, PA, USA) were used to test the hemolytic properties of BIP, as described previously (Isnansetyo and Kamei, 2003). BIP was serially diluted in PBS, and an equal volume of 4% RBCs were added in 96-well plates. After incubating at 37°C for 1 h, the plates were centrifuged at 500 × g for 5 min, and an aliquot of 100 μl of the supernatant from each well was transferred to a second 96-well plate. Triton-X (0.0025–1.0%) was used as a positive control. Visual inspection and absorbance at 540 nm were used to measure hemolysis.

Real-Time Quantitative PCR Assays

An overnight culture of MW2 was grown in TSB to evaluate the effects of BIP on bacterial gene expression. The culture was harvested when the OD600 had reached 0.4. The cells were washed with PBS and exposed to the sub-lethal concentration of BIP (32 or 64 μg/ml), vancomycin (0.5 μg/ml), or DMSO for 4 h. RNA was prepared using RNeasy mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The Verso cDNA synthesis kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) was used for cDNA synthesis. Real-time quantitative polymerase chain reaction (RT-qPCR) was performed as described in the manufacturer’s instructions (Bio-Rad, CA, USA) using the primers reported by Liu et al. (2018) and the iCycler iQ real-time detection system (Bio-Rad). No-RT control was included as a negative control. According to Mitchell et al. (2011), the relative expression ratios were calculated as follows: n-fold expression = 2‑ΔΔCt, ΔΔCt = ΔCt (drug-treated)/ΔCt (untreated), where ΔCt represents the difference between the cycle threshold (Ct) of the gene studied and the Ct of housekeeping 16S rRNA gene (internal control). Primer sequences used in this study were: 5-GGGACCCGCACAAGCGGTGG-3 and 5-GGGTTGCGCTCGTTGCGGGA-3 (Atshan et al., 2013). Statistical significance was calculated using Student’s t-test.

Intracellular Killing Assays

RAW 264.7 macrophages were used to evaluate the intracellular killing of BIP-pretreated S. aureus. Assays were performed in triplicate as described by Schmitt et al. (2013). Briefly, macrophages were cultured and maintained as described previously (Jayamani et al., 2017). Macrophages (5 × 105) were seeded in 24-well plates 24 h before infection. The multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 25 (i.e., 25 bacterial cells per macrophage) was used for the assay in which BIP-pretreated MW2, untreated MW2 alone, or agr mutant S. aureus RN4220 cells were added to macrophage cultures for 2 h to interrogate phagocytosis. After the incubation period, planktonic bacteria were removed, and DMEM containing 200 μg/ml gentamicin was added for 2 h to inhibit/kill remaining extracellular bacteria. The cells were incubated under 5% CO2 for 20 h with gentamicin (1X MIC, 1 μg/ml) to prevent the multiplication of bacterial cells released from burst macrophages. After incubation, the macrophages were lysed by adding SDS to a final concentration of 0.02% (i.e., lysing only macrophages and not ingested bacteria). Cell lysates were diluted serially and the CFUs were enumerated by plating on TSA plates (Tharmalingam et al., 2017).

Live/Dead Staining Assay

The macrophage phagocytosis assay was performed as discussed in the intracellular killing assay above, except cells were not lysed. Instead, after 20 h of incubation, the cells were washed twice with 0.1 M 3-(N-morpholino) propanesulfonic acid (MOPS), pH 7.2, containing 1 mM MgCl2 (MOPS/MgCl2). Then, the cells were stained with live/dead staining solution (5 μM SYTO9, 30 μM propidium iodide and 0.1% saponin in MOPS/MgCl2) and incubated for 15 min in the dark. The cells were then rinsed with MOPS/MgCl2 and observed using a Nikon C1si 141 confocal microscope (Nikon, Melville, NY, USA) with 488- and 561-nm diode lasers and images were captured (Zheng et al., 2017b).

Checkerboard Assay

Compounds were arrayed in serial concentrations, vertically for one molecule and horizontally for the other molecule in 96-well plate. The bacterial inoculation and measurement of growth were carried out as described earlier in the antimicrobial susceptibility assay. The synergy was measured by calculating the fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) using the formula FICI = (A/MICA) + (B/MICB), whereby MICA and MICB are the MIC’s individual molecules, and (A) and (B) are the lowest concentration of the molecule in combination with another molecule that inhibits bacterial growth. An FICI of <0.5 indicated synergism and scores between 0.51 and 1.0 suggest a partial synergy between the compounds being tested (Odds, 2003).

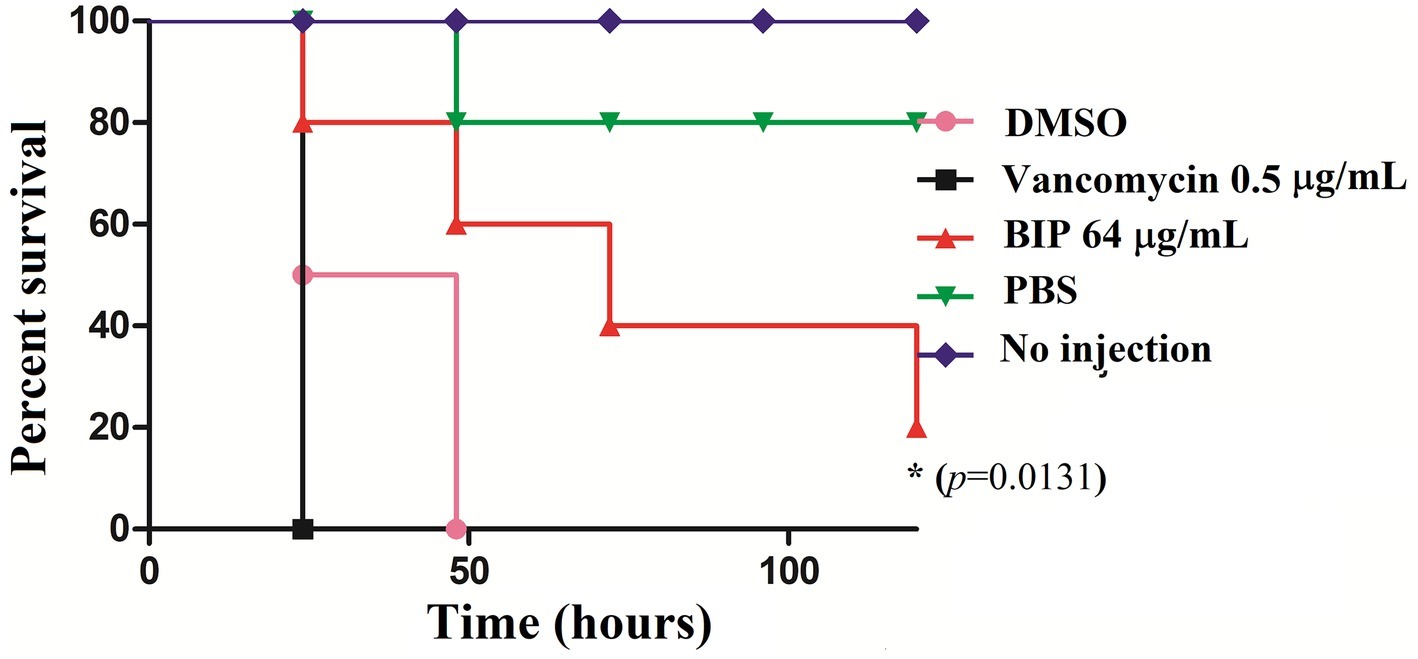

Galleria mellonella Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infection Assay

Sixteen G. mellonella larvae (Vanderhorst Wholesale, St. Mary’s, OH, USA), which were randomly selected and weigh between 300 and 350 mg, were used for each group in the experiment interrogated group (Gibreel and Upton, 2013). Overnight, MW2 cells were diluted at 1:2,000 in a cation-adjusted MHB in the presence of a sub-lethal concentration of BIP (64 μg/ml) or vancomycin (0.5 μg/ml). After incubation with agitation for 12 h, the cells were washed and suspended in PBS at an optical density of absorbance 600 (OD600) of 0.3. A 10-μl (2 × 106 cells/ml) inoculum was injected into the last left proleg using a Hamilton syringe and incubated at 37°C. Five test groups were included, and the same dose of bacteria was injected into the corresponding infection groups: (1) PBS alone (no bacteria control), (2) BIP-pretreated MW2 cells, (3) vancomycin-pretreated MW2 cells, (4) DMSO-pretreated MW2 cells, and (5) no injection and no bacteria (quality control). G. mellonella survival was assessed up to 120 h, with larvae considered dead if unresponsive to touch using sterile tips. Killing curves and differences in survival were analyzed by the Kaplan–Meier method using GraphPad Prism version 6.04 (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA, USA). All of the statistical analysis was carried out using the same program, and p < 0.05 was considered significant.

Results and Discussion

Antibacterial Susceptibility

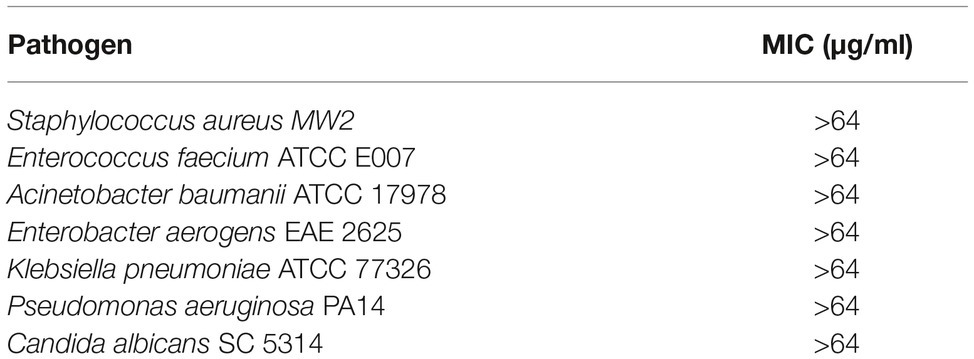

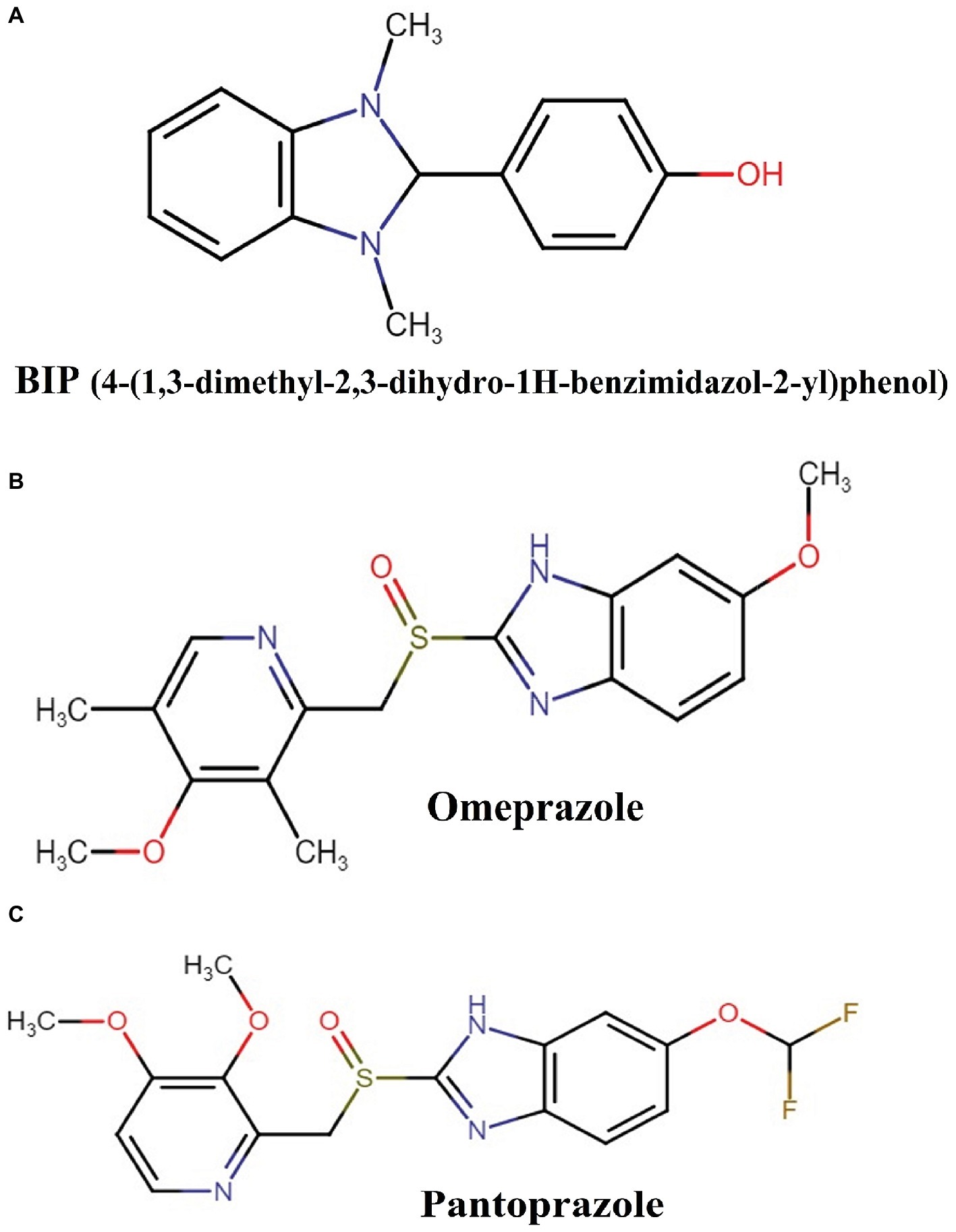

We previously reported several direct antibacterial molecules that were discovered using a whole organism C. elegans-based HTS (Rajamuthiah et al., 2014, 2015; Gwisai et al., 2017; Jayamani et al., 2017; Tharmalingam et al., 2017, 2018a,b; Zheng et al., 2017a). In this work, we report a molecule 4-(1,3-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)phenol (BIP) (Figure 1) that produced an average Z-score of 9.61 and rescued the nematode C. elegans from MW2 infection. The benzimidazole derivatives have potent antibacterial activity against Gram-positive (Göker et al., 2005; Tunçbilek et al., 2009; Karataş et al., 2012) and certain Gram-negative bacteria (Picconi et al., 2017; Vashist et al., 2018). Also, studies have reported that the benzimidazole derivatives exhibit an anti-biofilm and anti-virulence role (Kim et al., 2009; Sambanthamoorthy et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2018). Interestingly, although BIP was identified as a hit from the screen, the broth microdilution assay revealed that BIP did not inhibit the growth of S. aureus or any other organisms tested (Table 1). The seemingly contradictory results from HTS and broth-microdilution assay generated the hypothesis that the molecule may prolong host survival by either inhibiting bacterial virulence or modulating host immunity. We also tested the antibacterial activity of the benzimidazole derivatives omeprazole and pantoprazole. As previously reported (Sjöström et al., 1996; Ni et al., 2014), neither compound inhibited MW2 growth at the highest concentration tested (64 μg/ml).

Figure 1. Chemical structures of: (A) BIP (4-(1,3-dimethyl-2,3-dihydro-1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)phenol), (B) omeprazole, and (C) pantoprazole.

Exploring the Role of 4-(1,3-Dimethyl-2,3-Dihydro-1H-Benzimidazol-2-yl)Phenol on MW2 Growth

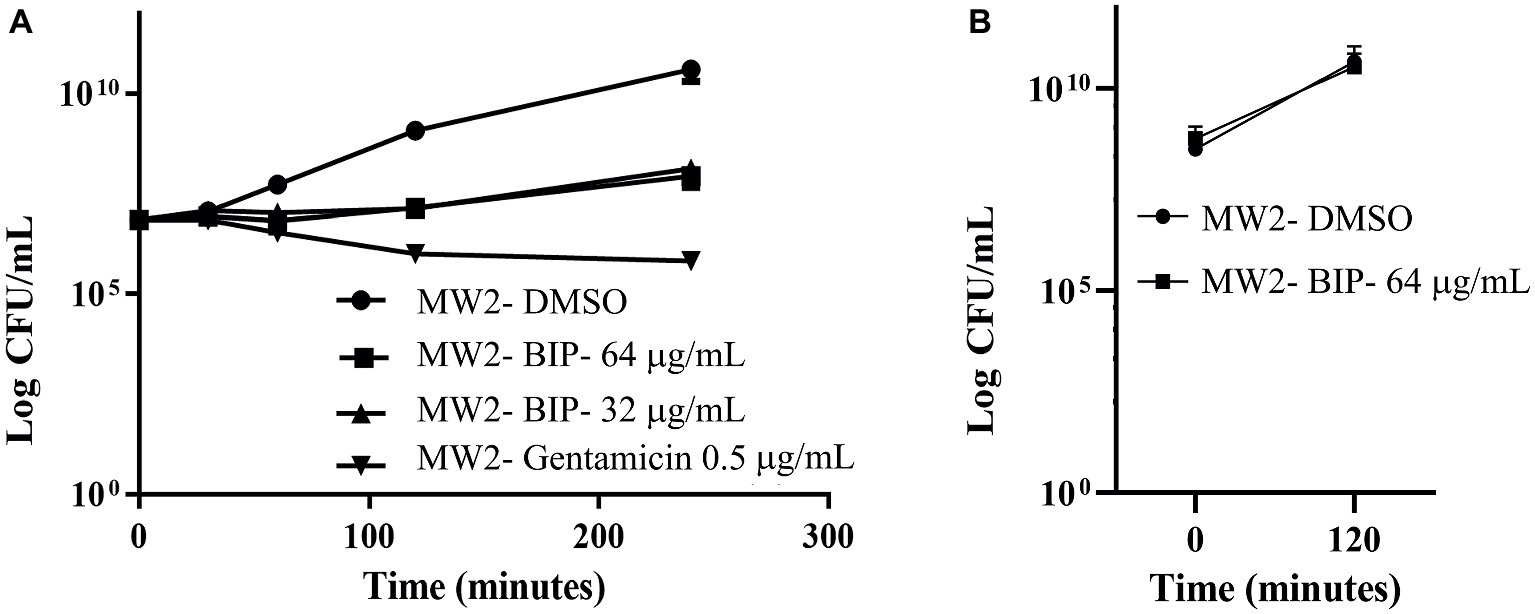

First, we aimed to evaluate whether BIP can decrease the bacterial cell numbers at the concentration of 32 or 64 μg/ml from an initial inoculum. The killing kinetics assay determined that the total viable bacterial count was about 5-logCFU at 0 h. After 4 h, the total viable count of BIP-pretreated cells was about 6-logCFU (Figure 2A). The DMSO-treated MW2 cells at the later time point were measured at 10-logCFU. The data suggest that BIP treatment resulted in slower bacterial growth compared to DMSO treatment but did not exert either bacteriostatic or bactericidal activity. As a positive control, we included the antibacterial agent gentamicin at 0.5 MIC (0.5 μg/ml). Gentamicin decreased the initial inoculum by 1-logCFU during the same time period (Figure 2A). In addition, a post-antibiotic effect assay determined that the bacterial cells grew normally compared to DMSO control after the cells were washed post drug treatment (Figure 2B). Taken together, we found that BIP did not decrease overall cell number from an initial inoculum and BIP-pretreated cells grew normally upon drug removal indicating that the effect of the compound is related to altered growth dynamic and not viability.

Figure 2. Killing kinetics. Growth curves were generated using S. aureus cells. (A) After BIP treatment, MW2 cells continued to grow, although at a slower rate than cells exposed to DMSO. (B) After BIP was removed by washing, the MW2 cells exhibited normal growth comparable to DMSO pre-treated cells. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

Toxicity of 4-(1,3-Dimethyl-2,3-Dihydro-1H-Benzimidazol-2-yl)Phenol on Human Red Blood Cellss

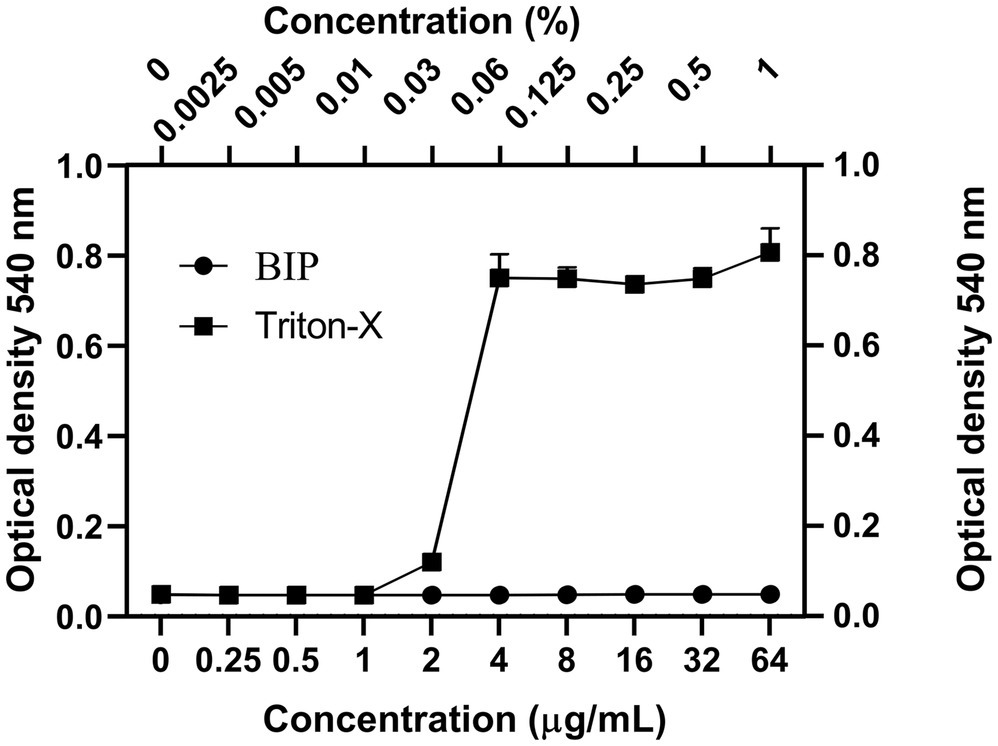

We tested the hemolysis potential of BIP with human RBCs and found that the BIP treatment did not cause hemolysis up to 64 μg/ml (Figure 3). We used 0.0025–1.0% of Triton-X as a positive control. The lack of detectable RBC cytotoxicity was confirmed in this assay.

Figure 3. Cytotoxicity assay. Toxicity of BIP was tested using human red blood cells. BIP concentrations up to 64 μg/ml did not cause hemolysis. In this study, 0.0025–1% Triton-X was used as a positive control. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3).

Exploring the Anti-virulence Role of 4-(1,3-Dimethyl-2,3-Dihydro-1H-Benzimidazol-2-yl)Phenol

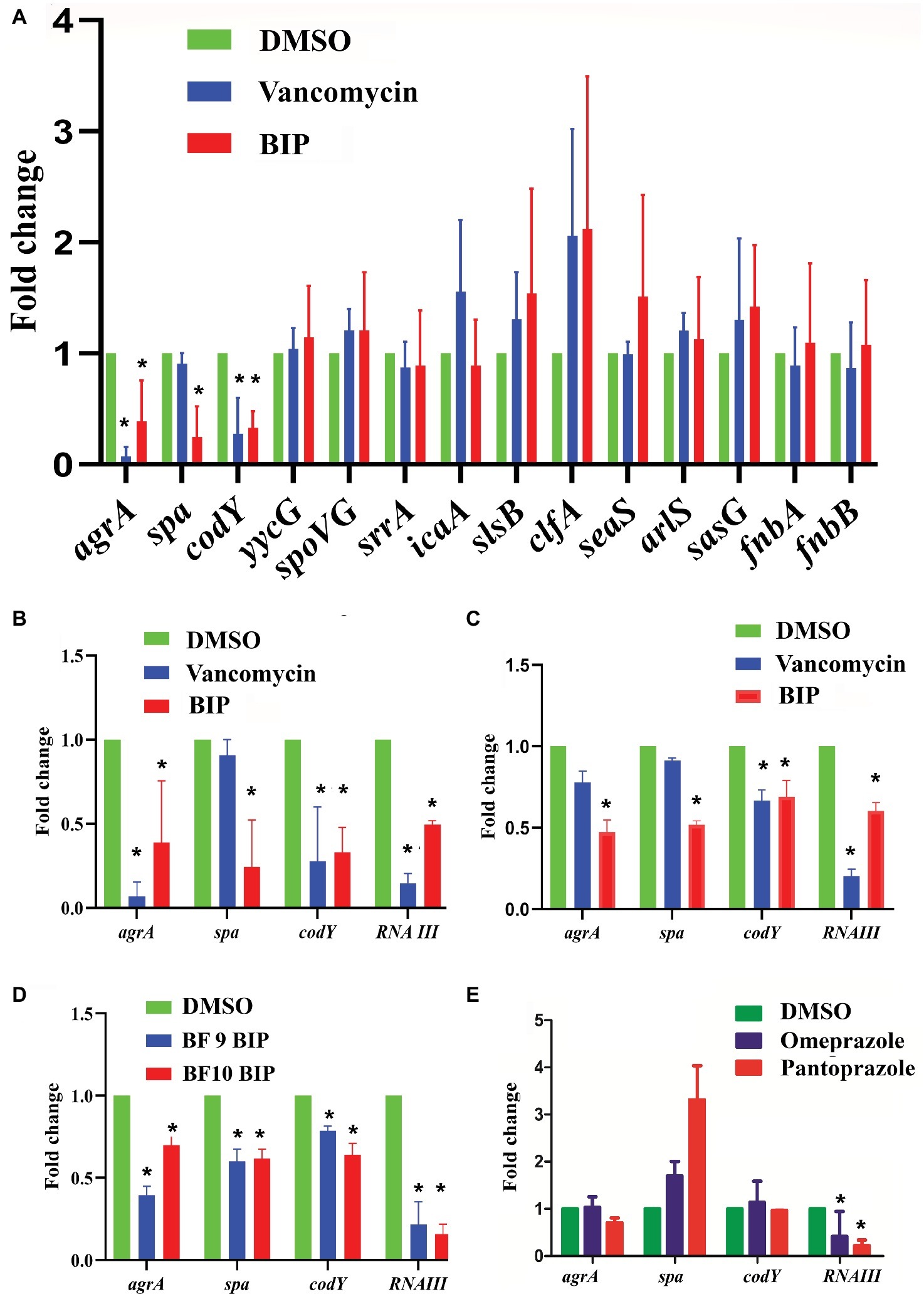

We examined a panel of known virulence genes (agrA, spa, codY, yycG, spoVG, srrA, icaA, slsB, clfA, saeS, arlS, sasG, fnbA, fnbB) to evaluate if they were affected by BIP. Since RNA III is known to control several virulence factors, we also included it in the panel of examined genes. After exposing bacteria to BIP, we monitored the expression of MW2 virulence genes through a real-time PCR assay. The presence of the BIP down-regulated virulence genes such as accessory gene regulator A (agrA), staphylococcal protein A (spa), and GTP-sensing transcriptional pleiotropic repressor (codY) with statistical significance (Figure 4A). Virulence gene expression after the BIP treatment was examined in reference and non-reference strains of S. aureus, including two clinical isolates in order to evaluate the effect of conservation. Interestingly, BIP induced down-regulation of agrA, spa, codY, and RNA III genes in all the isolates tested, (Figure 4D) demonstrated that the effect is not a strain-specific. To exclude the possibility of a time-dependent effect of BIP treatment, we examined the prolonged treatment (24 h) of BIP and observed a down-regulation of agrA, spa, and codY (Figures 4B,C) in MW2. Benzimidazole derivatives are majorly known for their antimicrobial action (Singh et al., 2012). However, few studies show that these compounds target virulence determinants by inhibiting multiple adaptational response (MAR) transcription factor in various pathogens without targeting bacterial growth (Kim et al., 2009; Grier et al., 2010). These previous studies support our findings that the BIP down-regulates bacterial virulence without targeting bacterial growth in vitro.

Figure 4. Effect of BIP on virulence genes. S. aureus MW2 cells were treated with BIP (64 μg/ml) for 4 h. RNA was isolated and used as a template for cDNA synthesis and was analyzed using real-time PCR. (A) Exposure to BIP was associated with down-regulation of major virulence regulator genes, including agrA, spa, and codY. (B,C) The expression of virulence genes agrA, spa, codY, RNA III was examined during the 4- and 24-h treatments of BIP, respectively. Drug treatment down-regulated agrA, spa, codY, and RNA III expression. (D) Two clinical strains of S. aureus (BF 9, BF 10) were also evaluated for changes to agrA, spa, codY, and RNA III expression. (E) MW2 cells were exposed with the benzimidazole derivatives omeprazole and pantoprazole (64 μg/ml) for 4 h. Data represent the mean ± SD (n = 3). *p < 0.05, Student’s t-test comparing DMSO control.

In S. aureus, the agr system plays a central control in the regulation of virulence gene expression and is involved in the production of multiple virulence factors (Tan et al., 2018). Also, agrA is a response regulator of the agr system, and it binds to the recognition site in RNA III and RNA II (Tan et al., 2018). RNA III controls several virulence factors, including the spa gene (Huntzinger et al., 2005), supporting our finding that down-regulation of agrA by BIP is coupled with down-regulation of the spa gene. Shrestha et al. reported that the benzimidazole derivative (ABC-1) down-regulated spa primarily, but not fnbA, fnbB, clfA, and clfB (Shrestha et al., 2016) supports our study with a similar kind of observation. Exposure to BIP also caused reduced expression of codY that produces a global regulator protein known to repress agrBDCA and RNA III transcription (Roux et al., 2014). By comparison, vancomycin treatment caused down-regulation of agrA and codY (Figure 4A) but not spa, demonstrating that the sub-MIC level of vancomycin exerted limited influences on S. aureus virulence genes expression (Cázares-Domínguez et al., 2015; Hodille et al., 2017). In addition, we tested the anti-virulence activity of the benzimidazole derivatives omeprazole and pantoprazole (Kromer, 1995). Omeprazole at 64 μg/ml did not down-regulate the expression of the major staphylococcal virulence genes agrA, spa, and codY (Figure 4E). Pantoprazole at 64 μg/ml down-regulated the gene expression of RNA III (Figure 4E). These results, along with published reports, indicate that some benzimidazole derivatives down-regulate bacterial virulence (Kim et al., 2009; Sambanthamoorthy et al., 2011; Kong et al., 2018), while other benzimidazole derivatives, such omeprazole, and pantoprazole, do not appear to influence staphylococcal virulence. The two approved drugs, omeprazole and pantoprazole, are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) and reduce the gastric pH (Axon and Moayyedi, 1996). Structural activity relationship (SAR) studies demonstrated that the omeprazole and methoxy or fluorine-substituted analogs affect urease activity (Kühler et al., 1995). Vidaillac et al. demonstrated that the addition of one methoxy group in the benzimidazole nucleus resulted in improved activity (Vidaillac et al., 2007).

Macrophage Assay

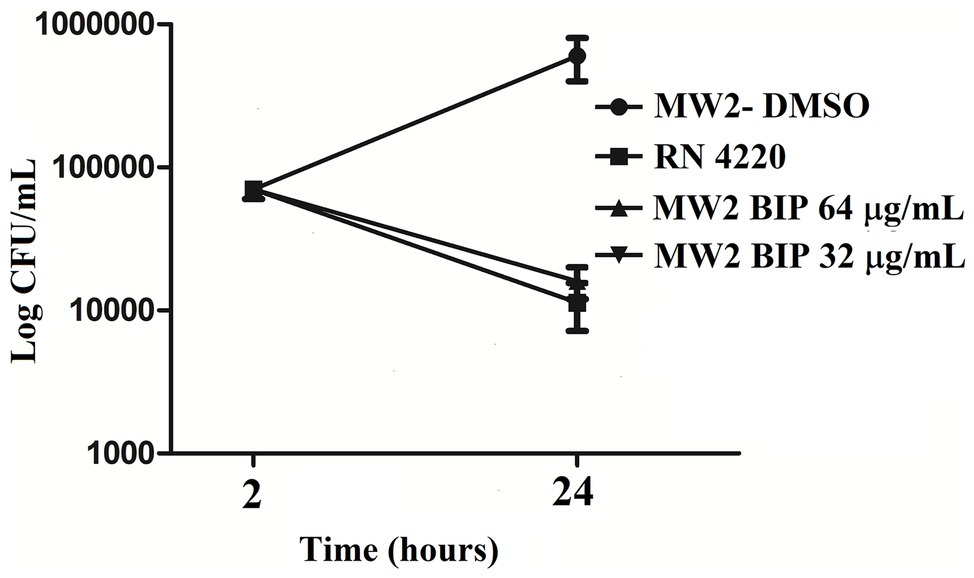

O’Keeffe et al. reported that the agr gene is associated with autophagosome protection of bacterial cells that leads to intracellular survival within phagocytes (O’Keeffe et al., 2015). As shown above, BIP causes down-regulation of agr and we investigated whether exposure to BIP affects the susceptibility of MRSA cells during phagocytosis by mouse macrophage cells. In this macrophage assay, MW2 cells were treated with BIP for 4 h, before being introduced into wells with RAW 264.7 cells. Untreated cells and the agr mutant strain S. aureus RN 4220 were included as controls. The agrA mutant strain RN4220 was used as a control in order to contrast the down-regulation of agrA in BIP-treated MW2 cells. After 20 h of incubation, live bacterial cells inside the macrophages were enumerated by total viable count and bacterial live/dead stain.

We found that the DMSO-pretreated MW2 cells survived and grew inside the macrophages. After 20 h of incubation, the 1.5-logCFU of DMSO-pretreated cells increased from the initially phagocytosed MW2 cells (Figure 5). However, BIP-pretreated cells and agr mutant S. aureus RN4220 were killed by macrophages, resulting in a 1-logCFU decrease from the initially phagocytosed MW2 cells inside the macrophages (Figure 5). Kong et al. reported that the new benzimidazole derivative (UM-C162) exhibits a strong anti-virulence role by down-regulating the major biofilm forming genes, including the genes responsible for intracellular multiplications (clpB, clpC, ctsR) (Kong et al., 2018). Hence, targeting genes responsible for intracellular bacterial survival directly or indirectly results in hindered intracellular multiplication, supporting our observation that the role of BIP on agrA down-regulation might contribute in making bacteria more prone to macrophage-mediated killing.

Figure 5. The effect of BIP in the killing of S. aureus MW2 cells by mouse macrophages. Raw 264.7 cells were co-incubated with BIP-pretreated MW2 cells, and the viable bacterial cells were enumerated after lysis release. Mouse macrophages killed the BIP-pretreated cells, while DMSO-pretreated cells survived and increased to 1.5-logCFU from the initial inoculation. The agr mutant strain S. aureus RN4220 was used as a positive control.

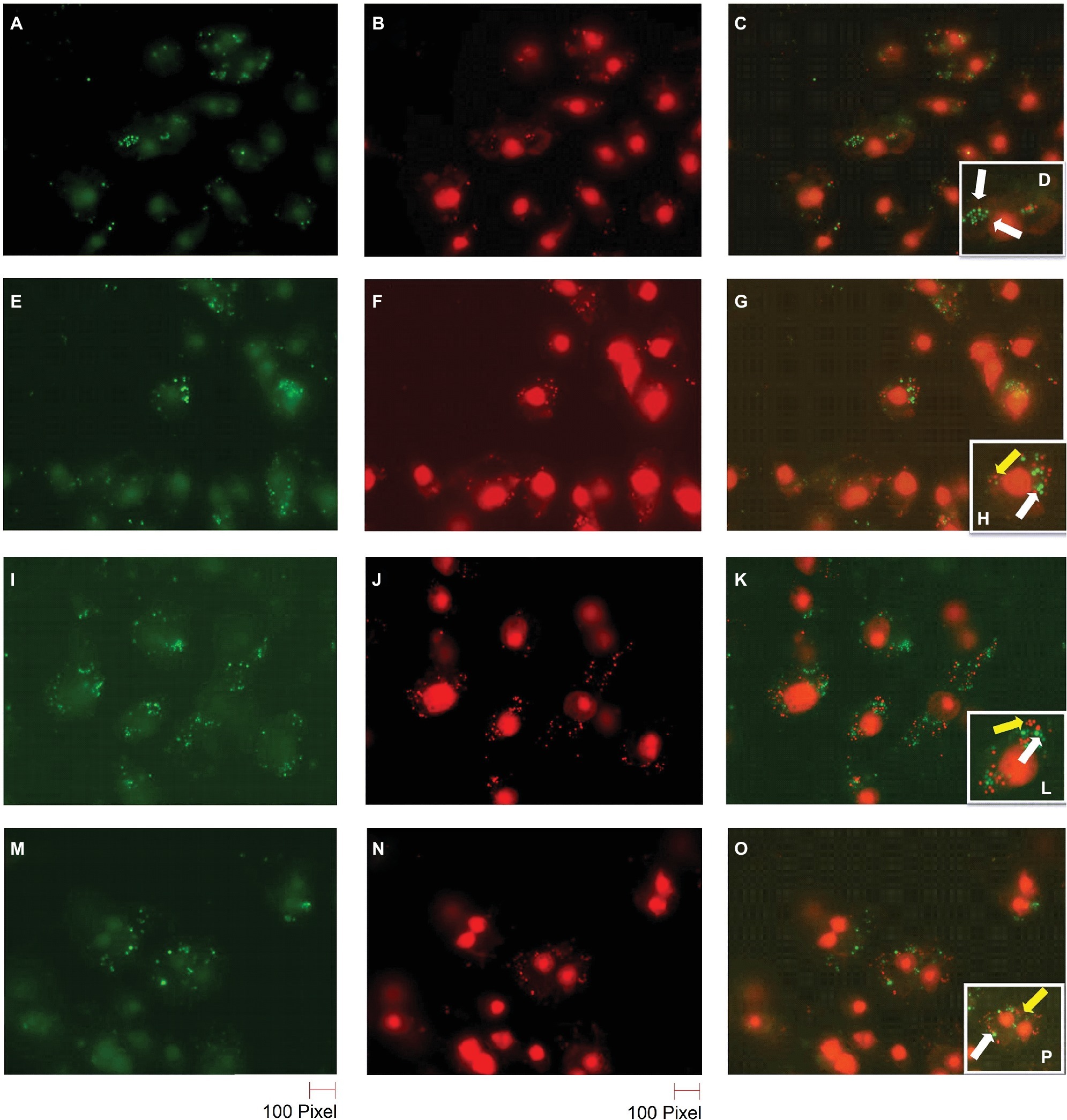

S. aureus cells can survive inside macrophages (Fraunholz and Sinha, 2012). In order to confirm the reduction of BIP-pretreated bacterial cells and the greater susceptibility of the agr mutant strain, we performed bacterial live/dead stain (green/red color) to differentiate viable versus dead cells inside the macrophages (Figures 6A–D). We found that the DMSO-pretreated MW2 cells fluoresced green (Figures 6A–D), indicating bacterial survival, and BIP-pretreated bacterial cells (64 μg/ml, Figures 6E–H; 32 μg/ml, Figures 6I–L) stained red, indicating death. These studies confirmed our findings observed through CFU-based data. We also used the S. aureus RN 4220 (an agrA mutant strain) to confirm the hypothesis that down-regulation of agrA makes bacteria more susceptible to macrophage-mediated killing (O’Keeffe et al., 2015). Indeed, the strain RN 4220 was more susceptible to macrophage-mediated killing (Figures 6M–P), than a wild strain of MW2.

Figure 6. Live/dead staining of BIP-pretreated S. aureus MW2 cells within macrophages. Raw 264.7 cells were allowed to phagocytose MW2 cells that were pretreated with either DMSO or BIP. After 20 h, the cells were washed and stained with a bacterial live/dead stain. The fluorescence figures were imaged using two different channels. Live cells are depicted with green fluorescent images (A,E,I,M), and dead cells are represented in red fluorescent images (B,F,J,N) (magnification 65×). Images taken in two different channels were merged (C,G,K,O) and enlarged images are presented in the panel (D,H,L,P). Live bacterial cells were marked with a white arrow, and dead bacterial cells were marked with a yellow arrow. DMSO-treated bacterial cells (A–D) were stained green, while BIP-pretreated bacterial cells (E–H – 64 μg/ml and I–L – 32 μg/ml) were stained red suggesting that pretreatment with BIP made cells susceptible to macrophage killing. The agr mutant strain S. aureus RN4220 (M–P) was used as a positive control.

4-(1,3-Dimethyl-2,3-Dihydro-1H-Benzimidazol-2-yl)Phenol Potentiates Antibiotic Activity

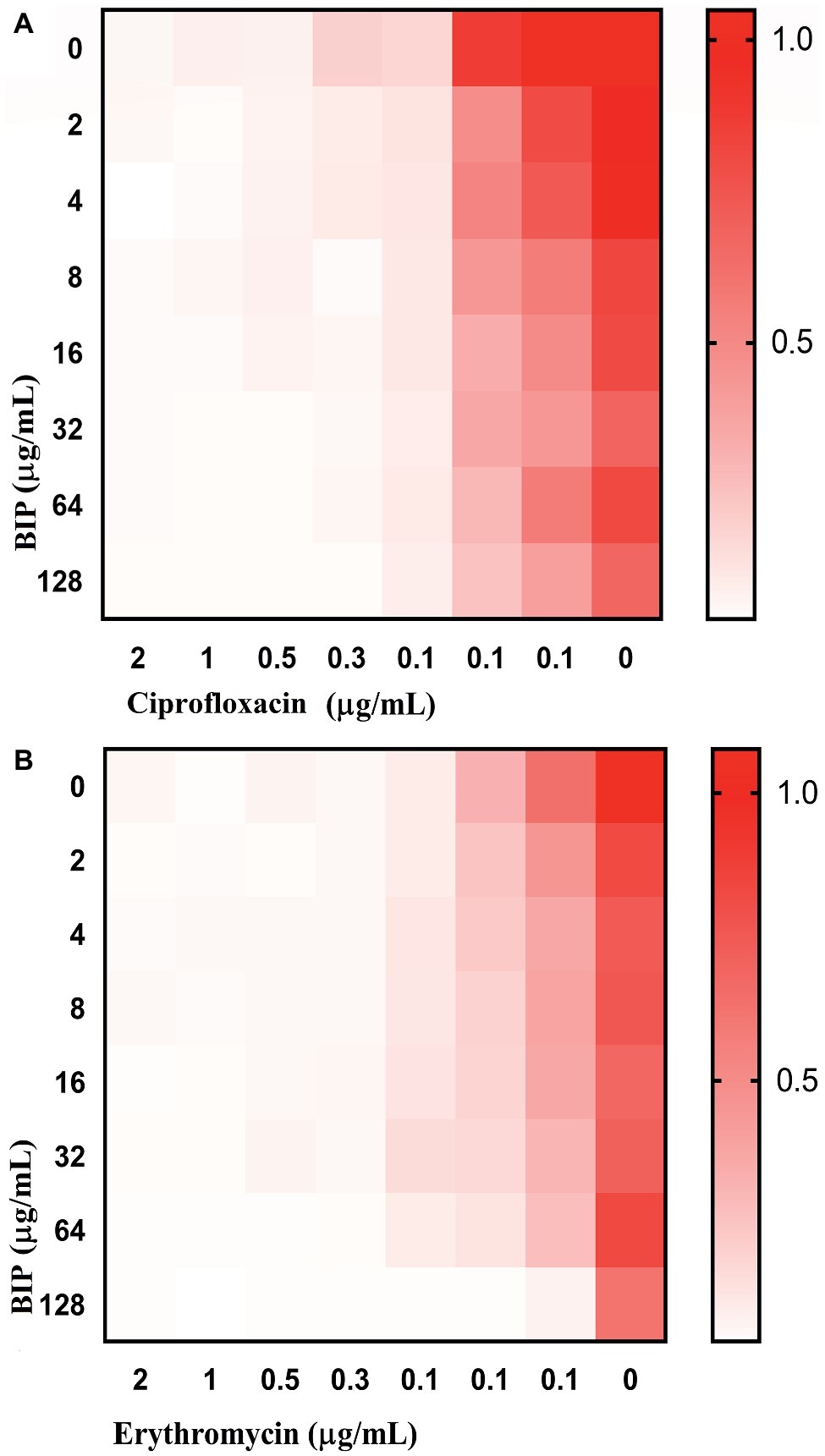

Anti-virulence molecules work synergistically with conventional antibiotics to impair bacterial cells (van Tilburg Bernardes et al., 2017). For example, Abraham et al. reported that the tick anti-virulence protein IAFGP demonstrated a synergistic role with conventional antibiotics (Abraham et al., 2017). Hence, we evaluated if BIP was synergistic with other conventional antibiotics, testing a representative from the most common antibiotics, including β-lactam, fluoroquinolones, peptide antibiotics, tetracyclines, macrolides, and aminoglycosides. In a checkerboard assay, BIP enhanced the antibiotic activity of ciprofloxacin and erythromycin (Figure 7) with a FICI of 0.75, a value that indicates partial synergy (Martin et al., 1996). Fractional Inhibitory Concentration Index (FICI) = (A/MICA) + (B/MICB), where MICA and MICB are the MIC’s individual molecules, and (A) and (B) are the lowest concentration of the molecule in combination with another molecule that inhibits bacterial growth. An FICI of <0.5 indicates synergism, while scores between 0.51 and 1.0 suggest a partial synergy between the compounds being tested (Odds, 2003).

Figure 7. Enhanced activity of clinical antibacterial agents in association with BIP. In the checkerboard assay, BIP demonstrated partial synergistic activity (FICI: 0.75) with (A) ciprofloxacin or (B) erythromycin. The representative figure is from triplicate repeats. The white color indicates no growth, and red color indicates a gradual increase in growth.

Insect Survival

G. mellonella is used widely to investigate various pathogens (Gibreel and Upton, 2013; Giannouli et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2017), and test new investigational compounds (Desbois and Coote, 2012). Given that BIP-pretreated cells were more susceptible to macrophage killing, we hypothesized that they would be less efficient in killing an infected host. We injected DMSO-treated MW2 cells versus BIP-pretreated MW2 cells into G. mellonella larvae. After 24 h, all larvae injected with DMSO-treated MW2 cells were dead (100%). However, at the same time point, 80% of BIP-pretreated (64 μg/ml) MW2 injected larvae survived (p = 0.131; Figure 8). Starkey et al. reported that the benzamide-benzimidazole phenoxy substituted benzamide ring that contains a benzimidazole moiety rescue mice from P. aeruginosa infection by reducing its acute virulence without reducing bacterial CFU (Starkey et al., 2014). Garrity et al. demonstrated that non-antibacterial LcrF inhibitors protected mice significantly from lethal Yersinia pseudotuberculosis lung infection (Garrity-Ryan et al., 2010). These reports support our insect survival data and, taken together, these observations suggest that the anti-virulence molecules harboring the benzimidazole moiety can prevent the invertebrate/vertebrate animals from lethal bacterial infection. Vancomycin is known to prolong the survival of S. aureus-infected G. mellonella (Tharmalingam et al., 2017). However, in the presented assay, a sub-MIC concentration was provided to G. mellonella as a positive control to induce a moderate inhibition of bacteria within the host. The provision of vancomycin at sub-MIC levels was shown to reduce expression of agrA, spa, and codY as was also seen with BIP treatment (Figure 4). However, a distinction between vancomycin and BIP treatment was noted with G. mellonella survival in which BIP prolonged survival, whereas vancomycin treatment did not.

Figure 8. In vivo killing efficacy of BIP-pretreated S. aureus MW2 cells in the G. mellonella model. MW2 cells were pretreated with BIP or DMSO for 12 h prior to injection to G. mellonella larva (n = 16). After 24 h, the group of larvae that received the BIP-pretreated cells survived longer than the group that received the DMSO-pretreated bacterial cells (p = 0.0131). As a control, the group of larvae that received vancomycin-pretreated MW2 cells also killed the larvae within 24 h from incubation. The figure is a representative graph from three independent replicates.

The finding suggests that exposure of MW2 cells to BIP results in down-regulation of major virulence factors, such as agrA, spa, codY. Moreover, the MW2 cells become more vulnerable to phagocytosis-mediated bacterial killing and, in turn, less virulent in a model host. Based on our findings, we conclude that BIP is an anti-virulence candidate compound that deserves further study. The current data lead us to believe that BIP acts in a capacity to inhibit S. aureus virulence factors. The fact that BIP treatment contributes to staphylococcal killing by macrophages and results in prolonged survival of the infected alternative host suggests that the compound might act through host immune modulation (which we do not rule out as a contributing influence) and/or inhibition of virulence attributes needed during the infection process. Apart from an anti-virulence role, BIP might modulate host immunity, but this is beyond the scope of this report. Nevertheless, the effects of benzimidazole derivatives to host immunity are noted in the literature. Wildenberg et al. reported that six benzimidazole derivatives induced regulatory macrophages (Wildenberg et al., 2017). Rickard et al. reported that the benzimidazole diamide GSK 669 inhibits NOD2, an intracellular pattern recognition receptor involved in the induction of pro-inflammatory cytokines (Rickard et al., 2013). Moreover, the benzimidazole derivatives are reported to have an analgesic action (Srivastava et al., 2012). In another study, the benzimidazole derivatives are a potential candidate for the management of opioid-induced paradoxical pain (Idris et al., 2019). As demonstrated by Alpan et al., BIP compounds can also bind with mammalian DNA (Alpan et al., 2007). Further SAR studies demonstrated that the methylated BIP (5-methyl-4-(1H-benzimidazole-2-yl)phenol) derivative exerts increased topo-isomerase I inhibition (Alpan et al., 2007). Interestingly, Gul et al. reported that the benzimidazole phenol derivative (4-(1H-benzimidazol-2-yl)phenol) inhibits human carbonic anhydrase (hCA) activity and addition of more phenol side group decreases the level of inhibition (Gul et al., 2016). Taken together, these reports suggest that the benzimidazole compounds potentially have multiple targets (Singh et al., 2012). In drug discovery, we often find that compounds do not have a singular effect or target; indeed, effects can be multifaceted. This withstanding, our current research does provide strong evidence that BIP inhibits known virulence genes. Future work is needed to determine the specific mechanisms that convey the anti-virulence effect.

Author Contributions

NT and EM conceived the idea and designed the study. NT designed the project, performed the experiments, and analyzed the data. RK performed the RT-qPCR and insect survival assays. NT drafted the manuscript with revisions and final approval by BF and EM. EM supervised the project.

Funding

This study was funded by NIH grants P01 AI083214 to EM and grant P20 GM121344 from the COBRE Center for Antimicrobial Resistance and Therapeutic Discovery, awarded to BF.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abraham, N. M., Liu, L., Jutras, B. L., Murfin, K., Acar, A., Yarovinsky, T. O., et al. (2017). A tick antivirulence protein potentiates antibiotics against Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e00113–e00117. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00113-17

Alpan, A. S., Gunes, H. S., and Topcu, Z. (2007). 1H-benzimidazole derivatives as mammalian DNA topoisomerase I inhibitors. Acta Biochim. Pol.-English Edition 54, 561–565. Available at: http://www.actabp.pl/pdf/3_2007/561.pdf

Atshan, S. S., Shamsudin, M. N., Karunanidhi, A., Van Belkum, A., Lung, L. T. T., Sekawi, Z., et al. (2013). Quantitative PCR analysis of genes expressed during biofilm development of methicillin resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA). Infect. Genet. Evol. 18, 106–112. doi: 10.1016/j.meegid.2013.05.002

Axon, A., and Moayyedi, P. (1996). Eradication of Helicobacter pylori: omeprazole in combination with antibiotics. Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 31, 82–89.

Beanan, M. J., and Strome, S. (1992). Characterization of a germ-line proliferation mutation in C. elegans. Development 116, 755–766.

Cázares-Domínguez, V., Ochoa, S. A., Cruz-Córdova, A., Rodea, G. E., Escalona, G., Olivares, A. L., et al. (2015). Vancomycin modifies the expression of the agr system in multidrug-resistant Staphylococcus aureus clinical isolates. Front. Microbiol. 6:369. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00369

de Kraker, M. E., Stewardson, A. J., and Harbarth, S. (2016). Will 10 million people die a year due to antimicrobial resistance by 2050? PLoS Med. 13:e1002184. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002184

Defoirdt, T. (2017). Quorum-sensing systems as targets for antivirulence therapy. Trends Microbiol. 26, 313–328. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2017.10.005

Desbois, A. P., and Coote, P. J. (2012). “Utility of greater wax moth larva (Galleria mellonella) for evaluating the toxicity and efficacy of new antimicrobial agents”. Adv. Appl. Microbiol. 78, 25–53. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-394805-2.00002-6

Dickey, S. W., Cheung, G. Y., and Otto, M. (2017). Different drugs for bad bugs: antivirulence strategies in the age of antibiotic resistance. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 16, 457–471. doi: 10.1038/nrd.2017.23

Fraunholz, M., and Sinha, B. J. F. I. C. (2012). Intracellular Staphylococcus aureus: live-in and let die. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2:43. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2012.00043

Garrity-Ryan, L. K., Kim, O. K., Balada-Llasat, J.-M., Bartlett, V. J., Verma, A. K., Fisher, M. L., et al. (2010). Small molecule inhibitors of LcrF, a Yersinia pseudotuberculosis transcription factor, attenuate virulence and limit infection in a murine pneumonia model. Infect. Immun. 78, 4683–4690. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01305-09

Giannouli, M., Palatucci, A. T., Rubino, V., Ruggiero, G., Romano, M., Triassi, M., et al. (2014). Use of larvae of the wax moth Galleria mellonella as an in vivo model to study the virulence of Helicobacter pylori. BMC Microbiol. 14:228. doi: 10.1186/s12866-014-0228-0

Gibreel, T. M., and Upton, M. (2013). Synthetic epidermicin NI01 can protect Galleria mellonella larvae from infection with Staphylococcus aureus. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 68, 2269–2273. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkt195

Göker, H., Özden, S., Yıldız, S., and Boykin, D. W. (2005). Synthesis and potent antibacterial activity against MRSA of some novel 1, 2-disubstituted-1H-benzimidazole-N-alkylated-5-carboxamidines. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 40, 1062–1069. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2005.05.002

Grier, M. C., Garrity-Ryan, L. K., Bartlett, V. J., Klausner, K. A., Donovan, P. J., Dudley, C., et al. (2010). N-Hydroxybenzimidazole inhibitors of ExsA MAR transcription factor in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: in vitro anti-virulence activity and metabolic stability. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 20, 3380–3383. doi: 10.1016/j.bmcl.2010.04.014

Gul, H. I., Yazici, Z., Tanc, M., and Supuran, C. T. (2016). Inhibitory effects of benzimidazole containing new phenolic Mannich bases on human carbonic anhydrase isoforms hCA I and II. J. Enzyme Inhib. Med. Chem. 31, 1540–1544. doi: 10.3109/14756366.2016.1156675

Gwisai, T., Hollingsworth, N., Cowles, S., Tharmalingam, N., Mylonakis, E., Fuchs, B., et al. (2017). Repurposing niclosamide as a versatile antimicrobial surface coating against device-associated, hospital-acquired bacterial infections. Biomed. Mater. 12, 1–13. doi: 10.1088/1748-605X/aa7105

Hauser, A. R., Mecsas, J., and Moir, D. T. (2016). Beyond antibiotics: new therapeutic approaches for bacterial infections. Clin. Infect. Dis. 63, 89–95. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciw200

Heras, B., Scanlon, M. J., and Martin, J. L. (2015). Targeting virulence not viability in the search for future antibacterials. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 79, 208–215. doi: 10.1111/bcp.12356

Hodille, E., Rose, W., Diep, B. A., Goutelle, S., Lina, G., and Dumitrescu, O. J. C. M. R. (2017). The role of antibiotics in modulating virulence in Staphylococcus aureus. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 30, 887–917. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00120-16

Huntzinger, E., Boisset, S., Saveanu, C., Benito, Y., Geissmann, T., Namane, A., et al. (2005). Staphylococcus aureus RNAIII and the endoribonuclease III coordinately regulate spa gene expression. EMBO J. 24, 824–835. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600572

Idris, Z., Abbas, M., Nadeem, H., and Khan, A.-U. (2019). The benzimidazole derivatives, B1 (N-[(1H-benzimidazol-2-yl) methyl]-4-methoxyaniline) and B8 (N-{4-[(1H-benzimidazol-2-yl) methoxy] phenyl} acetamide) attenuate morphine-induced paradoxical pain in mice. Front. Neurosci. 13, 1–9. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00101

Imperi, F., Massai, F., Pillai, C. R., Longo, F., Zennaro, E., Rampioni, G., et al. (2013). New life for an old drug: the anthelmintic drug niclosamide inhibits Pseudomonas aeruginosa quorum sensing. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 57, 996–1005. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01952-12

Isnansetyo, A., and Kamei, Y. (2003). MC21-A, a bactericidal antibiotic produced by a new marine bacterium, Pseudoalteromonas phenolica sp. nov. O-BC30(T), against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 47, 480–488. doi: 10.1128/AAC.47.2.480-488.2003

Jayamani, E., Tharmalingam, N., Rajamuthiah, R., Coleman, J. J., Kim, W., Okoli, I., et al. (2017). Characterization of a Francisella tularensis-Caenorhabditis elegans pathosystem for the evaluation of therapeutic compounds. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61, e00310–e00317. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00310-17

Karataş, H., Alp, M., Yıldız, S., and Göker, H. (2012). Synthesis and potent in vitro activity of novel 1H-benzimidazoles as anti-MRSA agents. Chem. Biol. Drug Des. 80, 237–244. doi: 10.1111/j.1747-0285.2012.01393.x

Kim, O. K., Garrity-Ryan, L. K., Bartlett, V. J., Grier, M. C., Verma, A. K., Medjanis, G., et al. (2009). N-hydroxybenzimidazole inhibitors of the transcription factor LcrF in Yersinia: novel antivirulence agents. J. Med. Chem. 52, 5626–5634. doi: 10.1021/jm9006577

Kim, W., Zhu, W., Hendricks, G. L., Van Tyne, D., Steele, A. D., Keohane, C. E., et al. (2018). A new class of synthetic retinoid antibiotics effective against bacterial persisters. Nature 556:103. doi: 10.1038/nature26157

Kong, C., Chee, C.-F., Richter, K., Thomas, N., Rahman, N. A., and Nathan, S. (2018). Suppression of Staphylococcus aureus biofilm formation and virulence by a benzimidazole derivative, UM-C162. Sci. Rep. 8:2758. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-21141-2

Kromer, W. (1995). Similarities and differences in the properties of substituted benzimidazoles: a comparison between pantoprazole and related compounds. Digestion 56, 443–454.

Kühler, T. C., Fryklund, J., Bergman, N.-K., Weilitz, J., Lee, A., and Larsson, H. (1995). Structure-activity relationship of omeprazole and analogs as Helicobacter pylori urease inhibitors. J. Med. Chem. 38, 4906–4916.

Liu, Q., Zheng, Z., Kim, W., Burgwyn Fuchs, B., and Mylonakis, E. (2018). Influence of subinhibitory concentrations of NH125 on biofilm formation & virulence factors of Staphylococcus aureus. Future Med. Chem. 10, 1319–1331. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0286

Longdon, B., Hadfield, J. D., Day, J. P., Smith, S. C., Mcgonigle, J. E., Cogni, R., et al. (2015). The causes and consequences of changes in virulence following pathogen host shifts. PLoS Pathog. 11:e1004728. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004728

Martin, S. J., Pendland, S. L., Chen, C., Schreckenberger, P., and Danziger, L. H. (1996). In vitro synergy testing of macrolide-quinolone combinations against 41 clinical isolates of Legionella. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40, 1419–1421.

Maura, D., Ballok, A. E., and Rahme, L. G. (2016). Considerations and caveats in anti-virulence drug development. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 33, 41–46. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2016.06.001

Mitchell, G., Lafrance, M., Boulanger, S., Séguin, D. L., Guay, I., Gattuso, M., et al. (2011). Tomatidine acts in synergy with aminoglycoside antibiotics against multiresistant Staphylococcus aureus and prevents virulence gene expression. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 67, 559–568. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkr510

Ni, W., Cai, X., Liang, B., Cai, Y., Cui, J., and Wang, R. (2014). Effect of proton pump inhibitors on in vitro activity of tigecycline against several common clinical pathogens. PLoS One 9:e86715. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0086715

Odds, F. C. (2003). Synergy, antagonism, and what the chequerboard puts between them. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkg301

O’Keeffe, K. M., Wilk, M. M., Leech, J. M., Murphy, A. G., Laabei, M., Monk, I. R., et al. (2015). Manipulation of autophagy in phagocytes facilitates Staphylococcus aureus bloodstream infection. Infect. Immun. 83, 3445–3457. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00358-15

Picconi, P., Hind, C., Jamshidi, S., Nahar, K., Clifford, M., Wand, M. E., et al. (2017). Triaryl benzimidazoles as a new class of antibacterial agents against resistant pathogenic microorganisms. J. Med. Chem. 60, 6045–6059. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.7b00108

Rajamuthiah, R., Fuchs, B. B., Conery, A. L., Kim, W., Jayamani, E., Kwon, B., et al. (2015). Repurposing salicylanilide anthelmintic drugs to combat drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 10:e0124595. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124595

Rajamuthiah, R., Fuchs, B. B., Jayamani, E., Kim, Y., Larkins-Ford, J., Conery, A., et al. (2014). Whole animal automated platform for drug discovery against multi-drug resistant Staphylococcus aureus. PLoS One 9:e89189. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0089189

Rampioni, G., Visca, P., Leoni, L., and Imperi, F. (2017). Drug repurposing for antivirulence therapy against opportunistic bacterial pathogens. Emerging Top. Life Sci. 1, 13–22. doi: 10.1042/ETLS20160018

Rickard, D. J., Sehon, C. A., Kasparcova, V., Kallal, L. A., Zeng, X., Montoute, M. N., et al. (2013). Identification of benzimidazole diamides as selective inhibitors of the nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain 2 (NOD2) signaling pathway. PLoS One 8:e69619. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069619

Roux, A., Todd, D. A., Velázquez, J. V., Cech, N. B., and Sonenshein, A. L. (2014). CodY-mediated regulation of the Staphylococcus aureus Agr system integrates nutritional and population density signals. J. Bacteriol. 196, 1184–1196. doi: 10.1128/JB.00128-13

Sambanthamoorthy, K., Gokhale, A. A., Lao, W., Parashar, V., Neiditch, M. B., Semmelhack, M. F., et al. (2011). Identification of a novel benzimidazole that inhibits bacterial biofilm formation in a broad-spectrum manner. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 55, 4369–4378. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00583-11

Schmitt, D. M., O’dee, D. M., Cowan, B. N., Birch, J. W., Mazzella, L. K., Nau, G. J., et al. (2013). The use of resazurin as a novel antimicrobial agent against Francisella tularensis. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 3:93. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2013.00093

Shrestha, L., Kayama, S., Sasaki, M., Kato, F., Hisatsune, J., Tsuruda, K., et al. (2016). Inhibitory effects of antibiofilm compound 1 against Staphylococcus aureus biofilms. Microbiol. Immunol. 60, 148–159. doi: 10.1111/1348-0421.12359

Shrivastava, N., Naim, M. J., Alam, M. J., Nawaz, F., Ahmed, S., and Alam, O. (2017). Benzimidazole scaffold as anticancer agent: synthetic approaches and structure–activity relationship. Arch. Pharm. 350, 1–80. doi: 10.1002/ardp.201700040

Silva, L. N., Zimmer, K. R., Macedo, A. J., and Trentin, D. S. (2016). Plant natural products targeting bacterial virulence factors. Chem. Rev. 116, 9162–9236. doi: 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00184

Singh, N., Pandurangan, A., Rana, K., Anand, P., Ahamad, A., and Tiwari, A. K. (2012). Benzimidazole: a short review of their antimicrobial activities. Int. Curr. Pharm. J. 1, 119–127. doi: 10.3329/icpj.v1i5.10284

Sjöström, J., Fryklund, J., Kühler, T., and Larsson, H. (1996). In vitro antibacterial activity of omeprazole and its selectivity for Helicobacter spp. are dependent on incubation conditions. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 40, 621–626.

Srivastava, S., Pandeya, S., Yadav, M. K., and Singh, B. (2012). Synthesis and analgesic activity of novel derivatives of 1,2-substituted benzimidazoles. J. Chem. 2013. doi: 10.1155/2013/694295

Starkey, M., Lepine, F., Maura, D., Bandyopadhaya, A., Lesic, B., He, J., et al. (2014). Identification of anti-virulence compounds that disrupt quorum-sensing regulated acute and persistent pathogenicity. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004321. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004321

Tan, L., Li, S. R., Jiang, B., Hu, X. M., and Li, S. (2018). Therapeutic targeting of the Staphylococcus aureus accessory gene regulator (agr) system. Front. Microbiol. 9:55. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.00055

Tanaka-Hino, M., Sagasti, A., Hisamoto, N., Kawasaki, M., Nakano, S., Ninomiya-Tsuji, J., et al. (2002). SEK-1 MAPKK mediates Ca2+ signaling to determine neuronal asymmetric development in Caenorhabditis elegans. EMBO Rep. 3, 56–62. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kvf001

Tharmalingam, N., Jayamani, E., Rajamuthiah, R., Castillo, D., Fuchs, B. B., Kelso, M. J., et al. (2017). Activity of a novel protonophore against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Future Med. Chem. 9, 1401–1411. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0047

Tharmalingam, N., Port, J., Castillo, D., and Mylonakis, E. (2018a). Repurposing the anthelmintic drug niclosamide to combat Helicobacter pylori. Sci. Rep. 8:3701. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22037-x

Tharmalingam, N., Rajmuthiah, R., Kim, W., Fuchs, B. B., Jeyamani, E., Kelso, M. J., et al. (2018b). Antibacterial properties of four novel hit compounds from a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus–Caenorhabditis elegans high-throughput screen. Microb. Drug Resist. 24, 666–674. doi: 10.1089/mdr.2017.0250

Totsika, M. (2017). Disarming pathogens: benefits and challenges of antimicrobials that target bacterial virulence instead of growth and viability. Future Med. Chem. 9, 267–269. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2016-0227

Tunçbilek, M., Kiper, T., and Altanlar, N. (2009). Synthesis and in vitro antimicrobial activity of some novel substituted benzimidazole derivatives having potent activity against MRSA. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 44, 1024–1033. doi: 10.1016/j.ejmech.2008.06.026

van Tilburg Bernardes, E., Charron-Mazenod, L., Reading, D., Reckseidler-Zenteno, S. L., and Lewenza, S. (2017). Exopolysaccharide repressing small molecules with antibiofilm and antivirulence activity against Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 61:e01997-16. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01997-16

Vashist, N., Sambi, S. S., Narasimhan, B., Kumar, S., Lim, S. M., Shah, S. A. A., et al. (2018). Synthesis and biological profile of substituted benzimidazoles. Chem. Cent. J. 12:125. doi: 10.1186/s13065-018-0498-y

Vidaillac, C., Guillon, J., Arpin, C., Forfar-Bares, I., Ba, B. B., Grellet, J., et al. (2007). Synthesis of omeprazole analogues and evaluation of these as potential inhibitors of the multidrug efflux pump NorA of Staphylococcus aureus. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 51, 831–838. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01306-05

Wikler, M. A. (2006). Methods for dilution antimicrobial susceptibility tests for bacteria that grow aerobically; approved standard —eleventh edition. CLSI document M07-A9. 1–18. Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute; 2012.

Wildenberg, M. E., Levin, A. D., Ceroni, A., Guo, Z., Koelink, P. J., Hakvoort, T. B., et al. (2017). Benzimidazoles promote anti-TNF mediated induction of regulatory macrophages and enhance therapeutic efficacy in a murine model. J. Crohn's Colitis 11, 1480–1490. doi: 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjx104

Wilson, J., Schurr, M., Leblanc, C., Ramamurthy, R., Buchanan, K., and Nickerson, C. A. (2002). Mechanisms of bacterial pathogenicity. Postgrad. Med. J. 78, 216–224. doi: 10.1136/pmj.78.918.216

Yang, H.-F., Pan, A.-J., Hu, L.-F., Liu, Y.-Y., Cheng, J., Ye, Y., et al. (2017). Galleria mellonella as an in vivo model for assessing the efficacy of antimicrobial agents against Enterobacter cloacae infection. J. Microbiol. Immunol. Infect. 50, 55–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jmii.2014.11.011

Zaman, S. B., Hussain, M. A., Nye, R., Mehta, V., Mamun, K. T., and Hossain, N. (2017). A review on antibiotic resistance: alarm bells are ringing. Cureus 9:e1403. doi: 10.7759/cureus.1403

Zheng, Z., Liu, Q., Kim, W., Tharmalingam, N., Fuchs, B. B., and Mylonakis, E. (2017a). Antimicrobial activity of 1,3,4-oxadiazole derivatives against planktonic cells and biofilm of Staphylococcus aureus. Future Med. Chem. 10, 283–296. doi: 10.4155/fmc-2017-0159

Keywords: anti-virulent molecules, agrA, bacterial virulence, codY, methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

Citation: Tharmalingam N, Khader R, Fuchs BB and Mylonakis E (2019) The Anti-virulence Efficacy of 4-(1,3-Dimethyl-2,3-Dihydro-1H-Benzimidazol-2-yl)Phenol Against Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Front. Microbiol. 10:1557. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01557

Edited by:

Natalia V. Kirienko, Rice University, United StatesReviewed by:

Polly H. M. Leung, Hong Kong Polytechnic University, Hong KongYou-Hee Cho, Cha University, South Korea

Rustam Aminov, University of Aberdeen, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2019 Tharmalingam, Khader, Fuchs and Mylonakis. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eleftherios Mylonakis, ZW15bG9uYWtpc0BsaWZlc3Bhbi5vcmc=

Nagendran Tharmalingam

Nagendran Tharmalingam Rajamohammed Khader

Rajamohammed Khader Beth Burgwyn Fuchs

Beth Burgwyn Fuchs Eleftherios Mylonakis

Eleftherios Mylonakis