- ICAR Indian Institute of Soil Science, Bhopal, India

The processes regulating nitrification in soils are not entirely understood. Here we provide evidence that nitrification rates in soil may be affected by complexed nitrate molecules and microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs) produced during nitrification. Experiments were carried out to elucidate the overall nature of mVOCs and biogenic nitrates produced by nitrifiers, and their effects on nitrification and redox metabolism. Soils were incubated at three levels of biogenic nitrate. Soils containing biogenic nitrate were compared with soils containing inorganic fertilizer nitrate (KNO3) in terms of redox metabolism potential. Repeated NH4–N addition increased nitrification rates (mM NO31- produced g-1 soil d-1) from 0.49 to 0.65. Soils with higher nitrification rates stimulated (p < 0.01) abundances of 16S rRNA genes by about eight times, amoA genes of nitrifying bacteria by about 25 times, and amoA genes of nitrifying archaea by about 15 times. Soils with biogenic nitrate and KNO3 were incubated under anoxic conditions to undergo anaerobic respiration. The maximum rates of different redox metabolisms (mM electron acceptors reduced g-1 soil d-1) in soil containing biogenic nitrate followed as: NO31- reduction 4.01 ± 0.22, Fe3+ reduction 5.37 ± 0.12, SO42- reduction 9.56 ± 0.16, and CH4 production (μg g-1 soil) 0.46 ± 0.05. Biogenic nitrate inhibited denitrificaton 1.4 times more strongly compared to mineral KNO3. Raman spectra indicated that aliphatic hydrocarbons increased in soil during nitrification, and these compounds probably bind to NO3 to form biogenic nitrate. The mVOCs produced by nitrifiers enhanced (p < 0.05) nitrification rates and abundances of nitrifying bacteria. Experiments suggest that biogenic nitrate and mVOCs affect nitrification and redox metabolism in soil.

Introduction

Nitrification is a key biogeochemical process for the global nitrogen cycle (Nelson et al., 2016). Therefore, in-depth knowledge on nitrification is essential for agricultural, environmental, and economic reasons. Nitrification of ammonia to nitrate is a two-step process usually performed by two distinct groups of chemolitho-autotrophic microbes (Alfreider et al., 2017), one step oxidizes NH4+ to NO21-, while the other oxidizes NO21- to NO31- (Li Y. et al., 2018). In the first step, most of the NH4+ is converted to NO21-, but a small portion of the N is emitted as N2O (Liimatainen et al., 2018). This is produced as a byproduct when the intermediate HNO is produced during the oxidation of NH2OH to NO21-. HNO is further oxidized to NO21- and finally to NO31- (Weber et al., 2015). Complete ammonia oxidation (comammox) is energetically feasible and bacteria (Nitrospira sp.) capable of performing both steps have been identified (Daims et al., 2015). These bacteria encode all enzymes necessary for ammonia oxidation via nitrite to nitrate in their genomes (van Kessel et al., 2015).

Most ammonia oxidizing bacteria (AOB) belong to the Betaproteobacteria (β-AOB) (Pan et al., 2018). There are two distinct phylogenetic clusters within the β-AOB, the Nitrosomonas cluster and the Nitrosospira cluster (Zhao et al., 2015). The Nitrosomonas cluster comprises members of the genus Nitrosomonas. The Nitrosospira cluster comprises the genera Nitrosospira, Nitrosolobus, and Nitrosovibrio. Nitrite (NO21-) oxidizing bacteria have been described in four genera; Nitrobacter, Nitrococcus, Nitrospina, and Nitrospira (Han et al., 2017). Our understanding of the nitrogen cycle has been revised in the past few years by the discovery of ammonia oxidizing archaea (AOA) (Leininger et al., 2006). AOA are members of the proposed archaeal phylum Thaumarchaea (Gribaldo et al., 2010). However, AOA are difficult to cultivate, so some aspects of their physiology and contribution to biogeochemical pathways are still speculative. AOA are found in almost all environments. Crenarchaeotal 16S rRNA gene sequences have been recovered from different environments including Pacific and Atlantic oceans (Flood et al., 2015), lake sediments (Lliros et al., 2014), the guts of animals (Radax et al., 2012), agricultural soils (Tourna et al., 2011), and forest soils (Isobe et al., 2012). Typically AOA greatly outnumber AOB. In soil samples, the copy number of crenarchaeotal amoA is one to three orders of magnitude higher than bacterial amoA (Wuchter et al., 2006).

Nitrification is carried out by the microbial membrane-bound enzymes. The ammonia monooxygenase (AMO) is responsible for the conversion of NH3 to hydroxylamine (Bock and Wagner, 2013). The end product of nitrification, NO31-, may binds to cationic molecules present in soil or extracellular microbial molecules. Thus, the NO31- produced by nitrifiers can be different in nature than inorganic NO31-. The nitrates produced from nitrification may bind to extracellular complex organic compounds to form “biogenic nitrate.” Contrastingly, inorganic forms of NO3 (NaNO3, KNO3, NH4NO3, etc.) are in the form of salts. The bonding between NO31- and cations (Na, K, NH4, etc) in inorganic NO3 fertilizer is stronger than the bonding between NO31- and cellular organic cations in biogenic nitrate. Therefore, nitrate in the inorganic nitrate fertilizer preferably does not bind to cellular organic cations unlike the nitrate produced through nitrification. It is also reported that nitrifiers produce soluble microbial products (SMPs) which serve as supplementary organic substrates for heterotrophic bacteria (Dolinšek et al., 2013). The SMPs are mainly constituted of proteins and humics (Li J. et al., 2018). There is a possibility that after nitrification the product (NO31-) binds to SMPs forming “biogenic nitrate.” Like inorganic nitrate, the biogenic nitrate has two main biological functions. Either it is assimilated by plants and microbes (under aerobic condition) (Rubio-Asensio et al., 2014) or it is denitrified when anoxic conditions prevail. Nitrate reduction or denitrification is carried out by dissimilatory nitrate reducing bacteria (Castro-Barros et al., 2017). However, due to its complexation with SMPs, the availability and fate of biogenic nitrate can be different from inorganic fertilizer nitrate (KNO3).

Like other microorganisms, nitrifiers can produce volatile organic compounds (VOCs). However, information on the VOCs emitted by nitrifiers is scarce. Microbial VOCs (mVOCs) act as signal molecules for different microorganisms (Insam and Seewald, 2010). The mVOCs can modulate activities of the producing species, or of different microbial species. However, it is unclear how the volatiles produced by nitrifiers influence the activity of nitrifiers and denitrifiers. The manuscript aims to define how the NO31- derived from nitrification is different from that in chemical inorganic nitrate fertilizers.

Materials and Methods

Soil Sampling and Characterization

Experiments were carried out using soil samples collected during September 2016 from the experimental fields of the Indian Institute of Soil Science, Bhopal, Madhya Pradesh, India (23.30 N, 77.40 E, 485 m above mean sea level). The soil is a heavy clayey Vertisol (typic Haplustert, WRB code VR), characterized by: 5.7 g kg-1 organic C, 225 mg kg-1 available N, 2.6 mg kg-1 available P, and 230 mg kg-1 available K. The textural composition of soil was: sand 15.2%, silt 30.3%, clay 54.5%, electrical conductivity (EC) 0.43 dS m-1, and pH 7.5. The soil had 863.24 μM NO31-, 0.01 μM Fe2+, and 101.02 μM SO42-. Concentration of these ions was estimated by wet chemical method as given below (chemical analysis). After collection, the soil was hand-processed after breaking the clods and removing roots and stones. Soil was then passed through 2-mm mesh sieve and was used within 2 days of collection.

Nitrification and Biosynthesis of Biogenic Nitrate

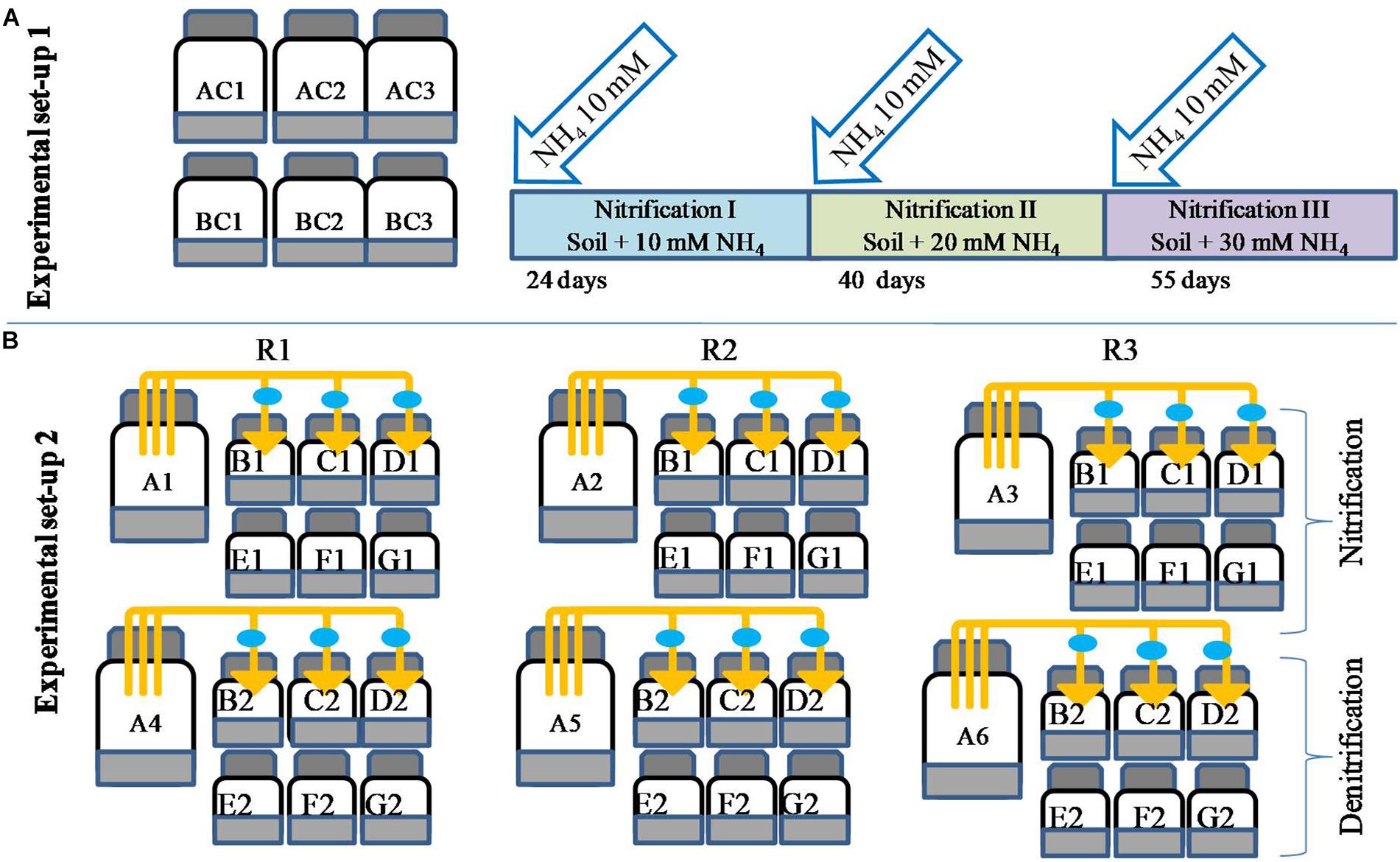

Biogenic nitrate is defined here as the nitrate produced via nitrification. To biosynthesize biogenic nitrate, microcosms were prepared where nitrification was carried out three times (Figure 1). The choice of having three repeated NH4 additions was based on the fact that in agriculture, N fertilizer is often applied in split doses, and for most crops, three split doses of N are recommended (Arregui and Quemada, 2008). Repeated nitrification resulted in different levels of nitrate (biogenic nitrate). Experiments were carried out in six 1000-ml bottles (Figure 1). Three bottles served as controls (AC1–AC3) and the other three were used for biosynthesis of biogenic nitrate and estimation of nitrification (labeled as BC1–BC3). To each bottle 200 g soil was added and sterilized double distilled water was added to maintain soil at 60% moisture holding capacity (MHC). There was no ammonium amendment to “AC” bottles, while 2 ml of 1 M NH4–N (NH4Cl) was added the “BC” bottles, giving a final concentration of 10 mM. Soils were mixed thoroughly using a glass rod and bottles were closed with butyl rubber caps. All the bottles were incubated at 30 ± 2°C. At different times, bottles BC1–BC3 were opened and 1-g soil subsamples were taken out to determine NO31- concentrations. Control bottles were also opened for analysis to mimic the treated ones. Nitrate measurement continued till the NO31- concentrations in BC bottles reached a plateau. Nitrification of the first dose of NH4–N (10 mM) was referred as “nitrification I.” After nitrification I, 10 mM of NH4–N was again added to BC bottles and the same incubation and measurement protocol applied until the NO31- was again stabilized. This second nitrification stage was referred as “nitrification II.” Subsequently, the bottles were again opened and amended with a third dose of 10 mM NH4–N in BC bottles. The third nitrification stage was referred as “nitrification III.” The three nitrification stages (nitrification I, II, and III) produced three levels of biogenic nitrate. After completion of each nitrification stage, 20-g soil was taken from the bottles (AC and BC) and incubated to evaluate redox metabolism as described below.

Figure 1. Microcosm design for biosynthesis of biogenic nitrate and estimation of nitrification potential of soil under repeated NH4–N amendment (setup 1, A). Microcosm setup to evaluate the effect of microbial volatiles (mVOCs) on nitrification and denitrification (setup 2, B). Bottles of 250 ml volume contained 50 g soil and were un-amended (AC1–AC3) or amended with 10 mM NH4 (BC1–BC3). After complete nitrification of 10 mM NH4 (24 days) a second dose of NH4 was added (BC bottles) and after complete nitrification (40 days) a third dose of 10 mM NH4 was added (BC bottles). The third nitrification stage was completed in 55 days of incubation. The three complete nitrification phases were designated as nitrification I, nitrification II, and nitrification III. The second setup (B) was designed to evaluate the effect of mVOCs (A1–A6) on nitrification and denitrification. All experimental treatments included three replicates (R1, R2, R3). The six source bottles (A1–A6) were connected to 18 sink bottles (130 ml volume containing 20 g of soil), shown as B1, C1, D1, B2, C2, and D2. The control bottles (130 ml bottle containing 20 g soil) were without exposure to mVOCs (E1, F1, G1 and E2, F2, G2). The connectors fitted with 0.2-μm filters (filled circle) were used to connect source and sink bottles. After each nitrification stage, one sink bottle and one control bottle were further incubated to determine nitrification and denitrification rates as mentioned the methodology.

The Effect of Biogenic Nitrate on Redox Metabolism

To evaluate the effect of biogenic nitrate on redox metabolism, experiments were carried out as described above (AC1–AC3 and BC1–BC3). In addition, 18 130-ml vials were also used for this analysis. Nine vials were kept for evaluating redox metabolism using soil mixed with equivalent amount of inorganic fertilizer nitrate (KNO3) as observed in nitrification vials (labeled as A). Another nine vials were used for evaluating redox metabolism using the soil in which biogenic nitrate was produced (labeled as B). Each set of nine vials was represented as three nitrification phases and three replicates. Soil (20 g) from AC1–AC3 and BC1–BC3 bottles (collected after nitrification I, II, and III) were placed into 130-ml serum vials. Soils were mixed with 10 mM of CH3COONa, and 50 ml of sterile distilled water. Acetate served as carbon source for anaerobic microbial metabolism. After mixing the contents, bottles were closed with rubber septa and sealed using aluminum crimp seals. Bottles were incubated at 30 ± 2°C with shaking at 100 revolutions per minute (rpm) on an orbital shaker for 30 days. To determine the temporal variation in the reduction of the terminal electron acceptors, 3 ml of slurry from each vial was withdrawn using a syringe (Dispovan, India). Before sampling, the syringes were first flushed with pure N2 to maintain anoxic conditions. Slurry samples were processed following standard methods to estimate NO31-, Fe3+, SO42- (see below). Changes in the concentrations of all electron acceptors (NO31-, Fe3+, SO42-) were measured at each sampling time to estimate the rates of redox metabolism. Headspace gas samples of the vials were analyzed via gas chromatography (see below) to quantify CH4 production at the end of the incubation period (30 days).

Effects of N2O and Microbial Volatiles on Nitrification

To test the effect of N2O on nitrification, experiments were carried out by placing 20 g soil into six 130-ml sterilized serum bottles. Soils were moistened with sterilized double distilled water to maintain 60% MHC and NH4–N was added to a final concentration of 10 mM. After mixing the contents, bottles were closed with rubber septa and sealed with aluminum crimp seals. Three bottles were kept as controls and three were injected with pure N2O (Inox Pvt. Ltd., Bhopal, India) to a final mixing ratio of 10 ppmv. Control vials were injected with pure helium (99%) instead of N2O. All bottles were incubated at 30 ± 2°C for 30 days. At different incubation, periods bottles were opened and 1 g amounts of soil taken to measure NO31-. After each NO31- measurement, bottles were re-incubated with 10 ppmv N2O.

To evaluate the effect of mVOCs on nitrification and denitrification, an experiment was set up as shown in Figure 1; 50 g amounts of soil were placed into 250-ml bottles, and sterile double distilled water added to maintain soil at 60% MHC. To each bottle, 10 mM NH4–N was added. Bottles were closed with rubber stoppers and tightened with screw caps. Three bottles were controls and six “source bottles” were the source of mVOCs originating from nitrification. Another set of 36 “sink bottles” were 130 ml serum bottles each containing 20 g of soil at 60% MHC. The headspace of one source bottle was connected with three sink bottles using silicon tubes (45 cm long × 0.5 cm internal diameter), each fitted with a needle (1.20 mm × 38 mm) at one end and a 0.2 μm syringe filter (25 mm) and needle (1.20 mm × 38 mm) at the other end. The syringe filters were used to restrict any microbial cross contamination between source bottles and sink bottles. The needles of both ends of the silicon tubes were pierced into the rubber caps of source and sink bottles. Gas phases of source and sink bottles were mixed via repeated (10 times) flushing (withdrawing and injecting) of the headspace of the sink bottles using a 50 ml syringe. A total of 18 sink bottles were connected with six source bottles, and another 18 sink bottles were not connected and served as “mVOCs control.” All bottles were kept in an incubator maintained at 30 ± 2°C in the dark. Headspace gas samples of all sink bottles were analyzed for N2O. Nitrification was measured only in the bottles labeled as “controls.”

Nitrification of 10 mM NH4–N in the source bottles was repeated three times as described earlier. The three nitrification stages were referred to as nitrification I, nitrification II, and nitrification III. At the completion of each nitrification phase, three sink bottles and three control bottles were removed and used for evaluating nitrification and denitrification rates. To measure nitrification in these bottles, 10 mM NH4–N was added and the accumulation of NO31- was determined. Denitrification was measured by adding 10 mM NO31- (KNO3) and 50 ml of sterile distilled water. Decline in NO31- concentrations was measured to determine denitrification.

Chemical Analyses

Soil nitrate content was estimated after extraction with CaSO4 and reaction by the phenol disulfonic acid method (Jackson, 1958). Reduced Fe2+ was determined by extracting slurries with 0.5 N HCl and ferrozine assay (Stookey, 1970). Sulfate (SO42-) content was estimated by extracting slurries with Ca(H2PO4)2 and turbidometric analysis (Searle, 1979). The slopes of regression lines relating the changes in NO3–N concentrations with the incubation time were used to determine the potential rates of nitrification or denitritrification (nitrification: μg NO31- produced g-1 soil d-1; denitrification: μg NO31- consumed g-1 soil d-1) (Schmidt and Belser, 1982). Potential iron (Fe3+) reduction rates were estimated from the increase of Fe2+ in slurries over time, and potential sulfate reduction rates were determined from declining SO42- concentrations.

Gas samples of 0.1 ml were withdrawn from the headspaces of the vials using a gas-tight syringe. After each sampling, the headspace was replaced with an equivalent amount of high purity (>99%) helium (He) to maintain atmospheric pressure. Gas analysis was carried out using a gas chromatograph (GC 2010, CIC, India) fitted with flame ionization detector (FID) and electron capture detector (ECD). Gas samples were introduced through the port of an on-column injector. The GC was calibrated before and after each set of measurements using different mixtures of gasses (CO2 or CH4 or N2O) in N2 (Inox Gas, Bhopal, India) as primary standards. Primary standards were CO2 (500, 1000 ppmv), CH4 (10 and 100 ppmv), and N2O (1 and 10 ppmv).

To quantify CO2 and CH4, a Porapak Q column (2 m length, internal diameter 3.175 mm, 80/100 mesh, stainless steel column) was used in combination with the FID. The CO2 was quantified after its conversion to CH4using a attached methanizer module at 350°C. The injector, column, and detector (FID) were maintained at 120, 60, and 330°C, respectively. N2O was estimated using a stainless steel column (2 ft; diameter, 1/8 in) filled with chromosorb 101 (60–80 mesh) coupled to the ECD. The oven temp was 30°C, the injector and detector (ECD) temp were 120 and 330°C, respectively.

Raman Spectroscopic Analysis of Soil

To test the hypothesis that NO31- derived through nitrification is a complex mixture of NO31- and cellular derived bio-molecules, and to reveal any compositional changes of soil due to nitrification, soil samples were analyzed by Raman spectrophotometry (Guizani et al., 2017). Soil samples of un-nitrified control and after third nitrification (nitrification III) were dried at room temperature. The dried soil samples were ground using a mortar and pestle and passed through a 0.1-mm sieve. Samples were scanned in a high-resolution Raman spectrometer (RamanStationTM 400F, Perkin-Elmer®, Beaconsfield, Buckingham-shire, United Kingdom) fitted with Czerny-Turner type achromatic spectrograph. The spectral resolution was 0.4 cm-1pixel-1 at the spectral range of 200–1050 nm and the source of excitation was a 632.8 nm, air cooled He–Ne laser. Nomenclature of wavelengths and the representing functional groups was based on the earlier publications (Socrates, 2004; Colthup, 2012). Data obtained from the instrument were normalized. Wavelengths representing each functional group were considered for analysis. Intensities of the peaks were added and the average of three replicates was calculated.

DNA Extraction

DNA was extracted from 0.5 g field soil samples using the ultraclean DNA extraction kit (MoBio, United States) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNA concentrations were determined in a biophotometer (Eppendorf, Germany) by measuring absorbance at 260 nm (A260), assuming that 1 A260 unit corresponds to 50 ng of DNA per μl. DNA extraction was further confirmed by electrophoresis on a 1% agarose gel. The extracted DNA was dissolved in 50 μl TE buffer and stored at -20°C until further analysis.

Real-Time PCR Quantification of Total Bacteria, Ammonia Oxidizing Bacteria, and Ammonia Oxidizing Archaea

Microbial abundance was estimated from two experimental setups: first with soil samples of un-incubated control, nitrification I, II, and III soils, and second with soil samples exposed to microbial volatiles (mVOCs) of nitrification III and un-exposed controls. The microbial groups estimated were total bacteria, AOB, and AOA. Real-time PCR was performed on a Step one plus real-time PCR (ABI, United States). Reaction mixtures contained 2 μl of DNA template, 10 μl of 2X SYBR green master mix (Affymetrix, United States), and 200 nM of each primer (GCC Biotech, New Delhi). The final volume of PCR reaction mixture was made to 20 μl with PCR grade water (MP Bio, United States). Primers targeting bacterial 16S rRNA genes, bacterial amoA genes, and archaeal amoA gene were used to quantify the respective microbial abundance. The primers (5’–3’) for bacteria were 1F (CCT ACG GGA GGC AGC AG) and 518R (ATT ACC GCG GCT GCT GG) (Baek et al., 2010); nitrifying bacteria 1F (GGG GTT TCT ACT GGT GGT) and amoA 2R1 (CCC CTC TGG AAA GCC TTC TTC) (Okano et al., 2004); nitrifying archaea arc-Amo-F (STA ATG GTC TGG CTT AGA CG; S = G or C); and arc-amoa-R (GCG GCC ATC CAT CTG TAT GT) (Mutlu and Guven, 2011). Thermal cycling was carried out by an initial denaturizing step at 94°C for 4 min, 40 cycles of 94°C for 1 min, the assay-dependent annealing temperature for 30 s, 72°C for 45 s; and a final extension at 72°C for 5 min. The annealing temperature for 16S rRNA genes was 52°C, and for amoA genes of bacteria and archaea were 50 and 52°C, respectively. Fluorescence was measured during the elongation step. Data analysis was carried out with Step one plus software (ABI, United States) as described in user’s manual. The cycle at which the fluorescence of target molecule number exceeded the background fluorescence (threshold cycle [CT]) was determined from dilution series of target amplicons with defined target molecule amounts. CT was proportional to the logarithm of the target molecule number. The quality of PCR amplification products was determined by melting curve analysis with temperature increase of 0.3°C per cycle. Standard for bacteria prepared by using Escherichia coli strain JM 109 (Promega Inc., United States). For preparing standard for amoA genes of nitrifying bacteria and nitrifying archaea, the PCR products of bacterial amoA and archaeal amoA genes were separately cloned to TOPO TA cloning vector (Invitrogen, United States). Constructed plasmids were transformed into competent cells (One Shot Top 10, Invitrogen, United States). Transformed cells (white colonies) were multiplied in LB broth for 24 h at 37°C and their concentration was estimated using a Biophotometer (Eppendorf, Germany). Plasmids from the E. coli or transformed cells were extracted using a plasmid extraction kit (Axygen, United States). Concentration of plasmids was quantified and expressed as ng μL-1. Serial dilution for each plasmid was prepared and real-time PCR carried out. Standard curve for each gene was prepared by plotting plasmid concentration (representing cell number or gene copies) versus CT values (Supplementary Table S1).

Statistical Analysis

All statistical analyses were carried out using the “agricolae” packages of the statistical software R (2.15.1) (Ihaka and Gentleman, 1996). Data obtained were presented as arithmetic mean of three replicated observations. Effect of factors (NH4 amendment) on the parameters (nitrification, denitrification, Fe3+ reduction, SO42- reduction, CH4 production, and microbial abundance) was tested by analysis of variance (ANOVA). Low P-value and high F statistics indicated significant impact of the factors on the variables. To define the significant difference among the treatments, Tukeys honestly significant difference (HSD) test was performed.

Results

Nitrification Activity of Soil

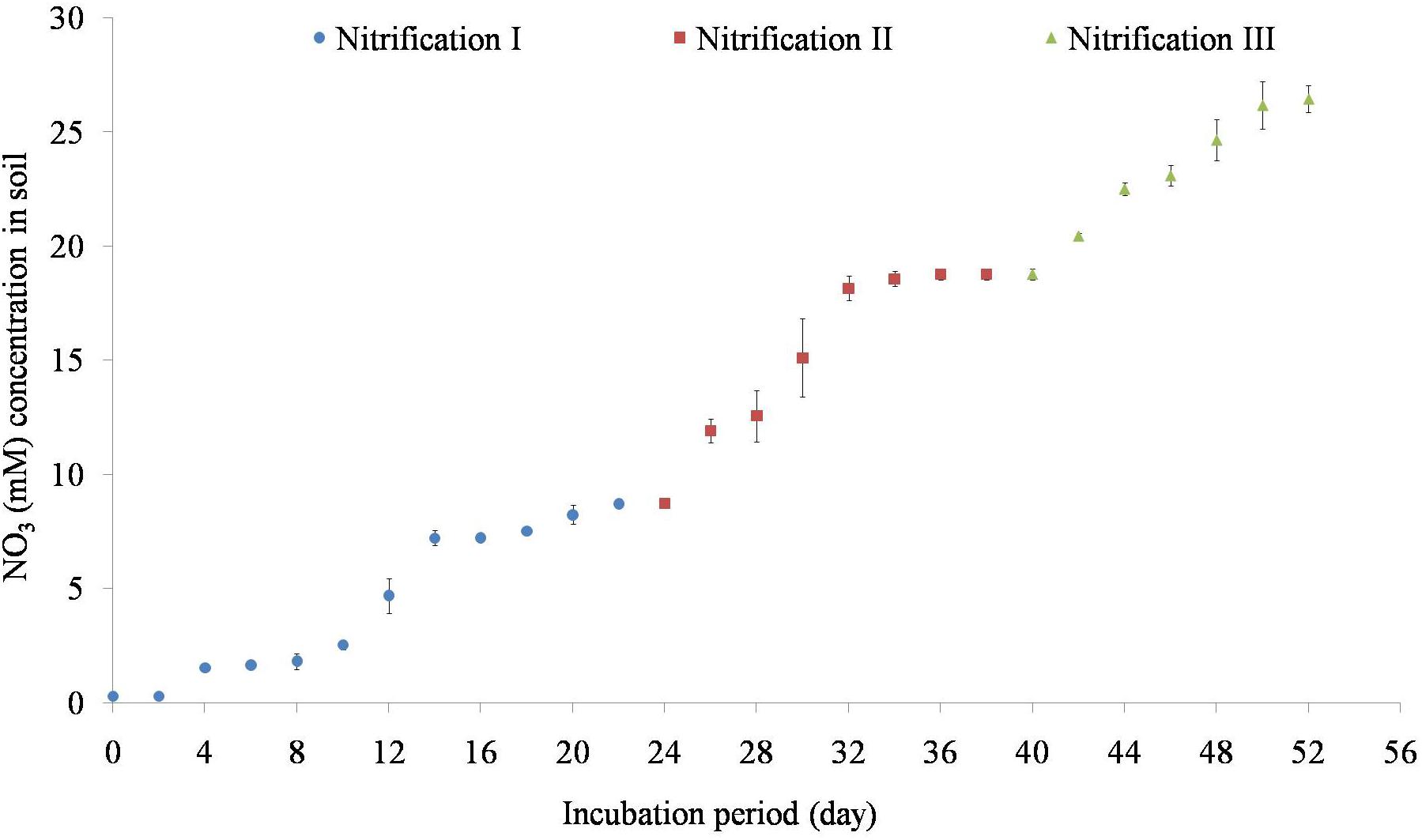

Variation of NO31- concentrations during repeated stages of nitrification is shown in Figure 2. Nitrification increased steadily after 5 days of incubation. Nitrification of the first dose of 10 mM NH4–N occurred within 24 days. Subsequent amendment of NH4–N stimulated nitrification. The second dose of 10 mM NH4–N was nitrified by 40 days while the third dose of 10 mM NH4–N was nitrified by 55 days. The added NH4–N was nitrified by about 84% in nitrification I, 92% in nitrification II, and 87% in nitrification III stages. Potential nitrification rates (PNRs) increased with repeated nitrification (Table 1). PNR of fresh soil was 0.49 mMg-1 soil d-1 while the PNR of nitrification III soil was highest of 0.65 mMg-1 soil d-1.

Figure 2. Temporal variation of nitrification in response to 10 mM NH4–N amendment. Nitrification was estimated as the increase in NO31- concentration afterNH4–N amendment. After complete nitrification, soils were again amended with 10 mM NH4 for a second and a third time to complete three nitrification stages (nitrification I, nitrification II, and nitrification III). Each data point represents an arithmetic mean with standard deviation of three replicates.

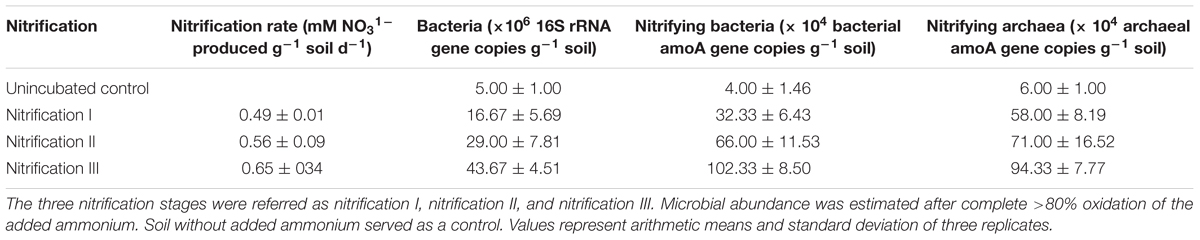

Table 1. Nitrification and microbial abundance in soil after nitrification of three successive 10 mM NH4–N amendments.

Effect of Nitrification on Microbial Abundance

Abundances of total bacteria, nitrifying bacteria, and nitrifying archaea all increased after repeated nitrification (Table 1). The bacterial population varied from 5 to 43.67 (×106 cells g-1 soil). The nitrifying bacterial population ranged from 4 to 102 (×104 cells g-1 soil) and the nitrifying archaeal population varied from 6 to 94.33 (×104 cells g-1 soil). The lowest abundances were measured in control treatments and the highest in the nitrification III soil samples.

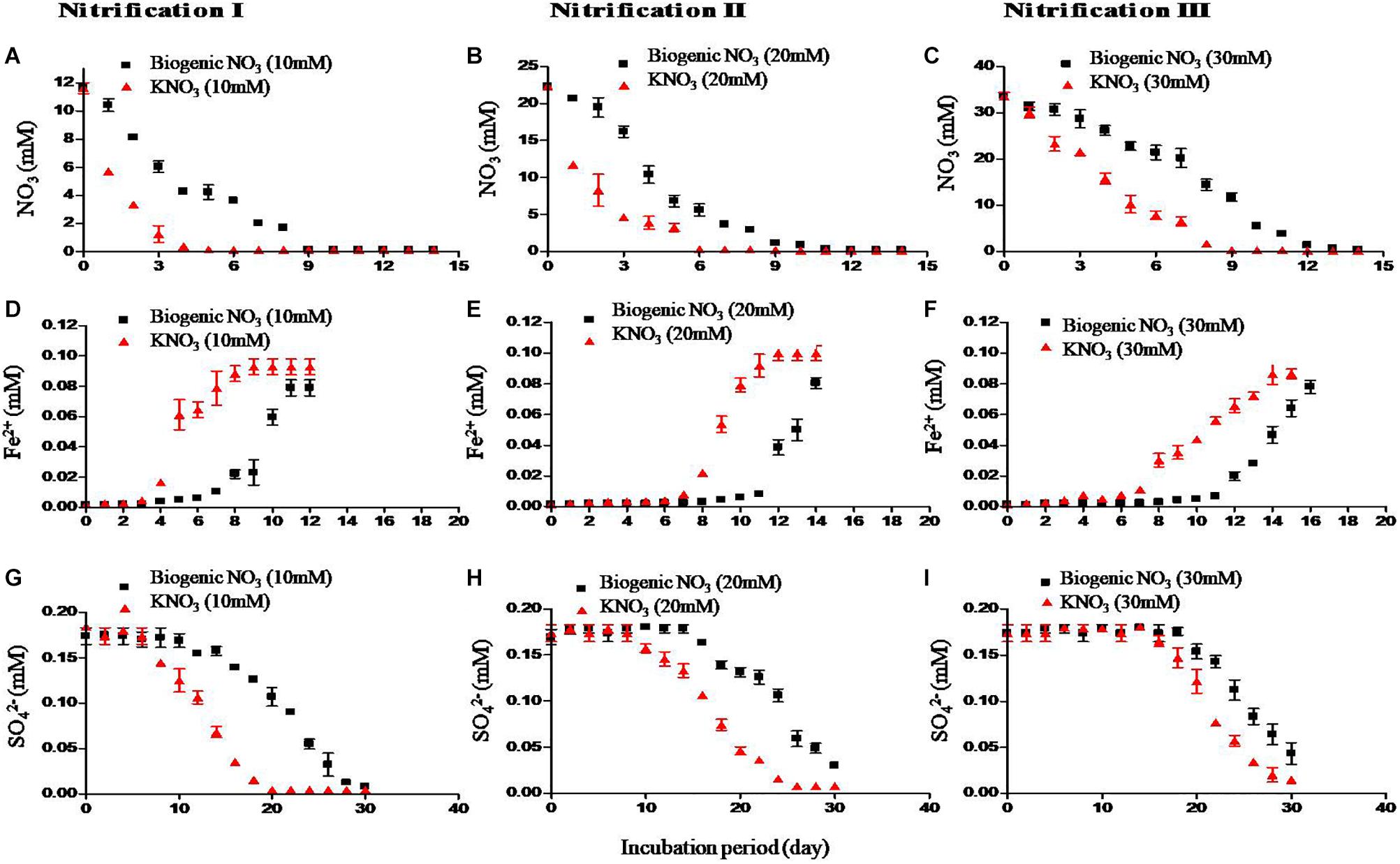

Effect of Nitrification on Redox Metabolism

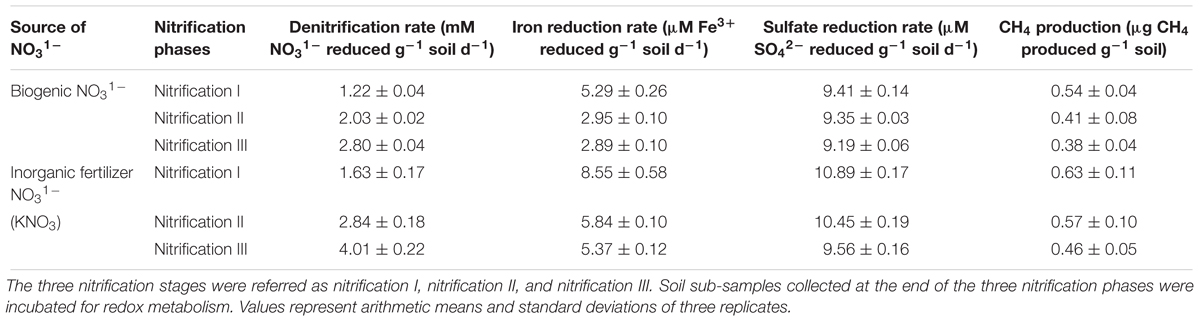

Redox metabolism followed the classical trend of sequential reduction of terminal electron acceptors (Figure 3), starting with NO31- reduction followed by Fe3+ reduction, SO42- reduction, and CH4 production. Soil amended with inorganic KNO3 exhibited detectable nitrate reduction after 2 days and complete denitrification within 5 days. Iron reduction peaked at 5 days and SO42- reduction after 2 weeks. Potential redox metabolic rates are presented in Table 2. Denitrification rates increased with NO31- concentration originating from either nitrification phases or KNO3. However, the denitrification rate was lower in the soil that had undergone nitrification than compared to the KNO3 treated soil. Denitrification may have been inhibited by biogenic nitrate. The reduction rate of Fe3+ was also lower in the nitrification soil. Similarly, the reduction of SO42- was also low in the nitrification soil. Production of CH4 was estimated after the end of incubation. CH4 production was low in nitrification soil compared to non-nitrification soil (Table 2).

Figure 3. Effect of nitrification on redox metabolism. Soil samples after three nitrification stages were incubated to undergo redox metabolism. Inorganic NO31- (KNO3) was used to compare with biogenic NO31- (i.e., nitrate produced from nitrification). First row – denitrification (NO31- reduction) (A–C), second row – iron (Fe3+) reduction (D–F) measured as increase of Fe2+ concentration, and third row – SO42- reduction (G–I). The three nitrifications stages were nitrification I (left), nitrification II (center), and nitrification III (right). Each data point represents an arithmetic mean and standard deviation of three replicates.

Table 2. Influence of biogenic NO31- and inorganic fertilizer KNO3 on soil denitrification rate, iron reduction rate, sulfate reduction rate, and methane production rate.

Statistical Analyses

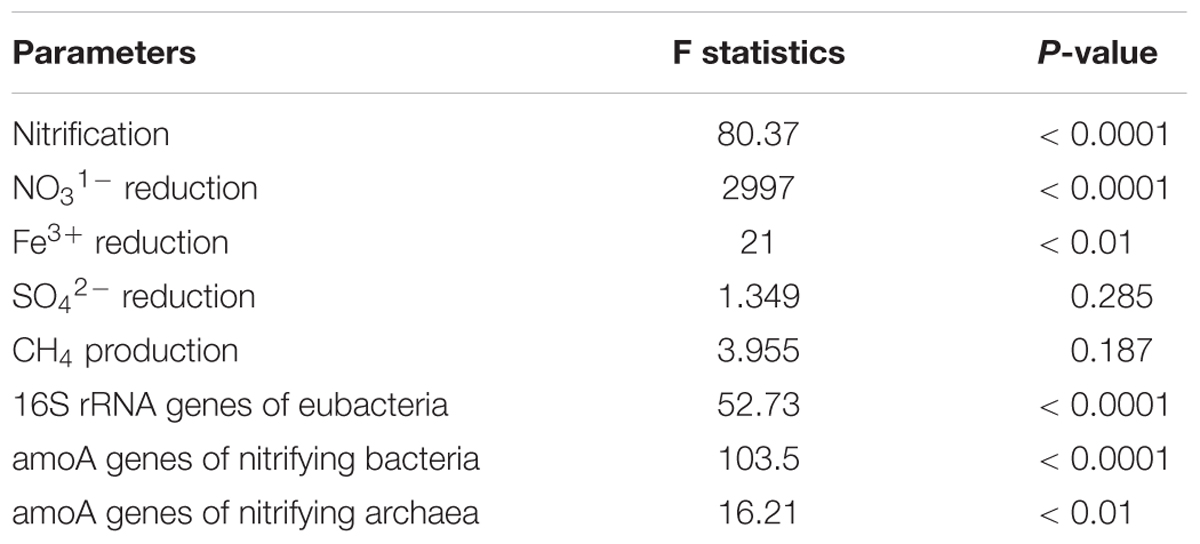

Analysis of variance indicated that NH4–N addition significantly and positively influenced nitrification (p < 0.0001) (Table 3). It also significantly influenced NO31- reduction (p < 0.0001), and Fe3+ reduction (p < 0.01) compared to or inorganic nitrate amendment. However, SO42- reduction and CH4 production were not significantly affected. Abundances of 16S rRNA genes, amoA genes of nitrifying bacteria, and amoA genes of nitrifying archaea were significantly (p < 0.0001) influenced by the NH4 amendment.

Table 3. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) to determine the effect of NH4 amendment on nitrification, denitrification, sulfate reduction, CH4 production, abundance of bacterial 16S rRNA genes, amoA of nitrifying bacteria, and amoA of nitrifying archaea.

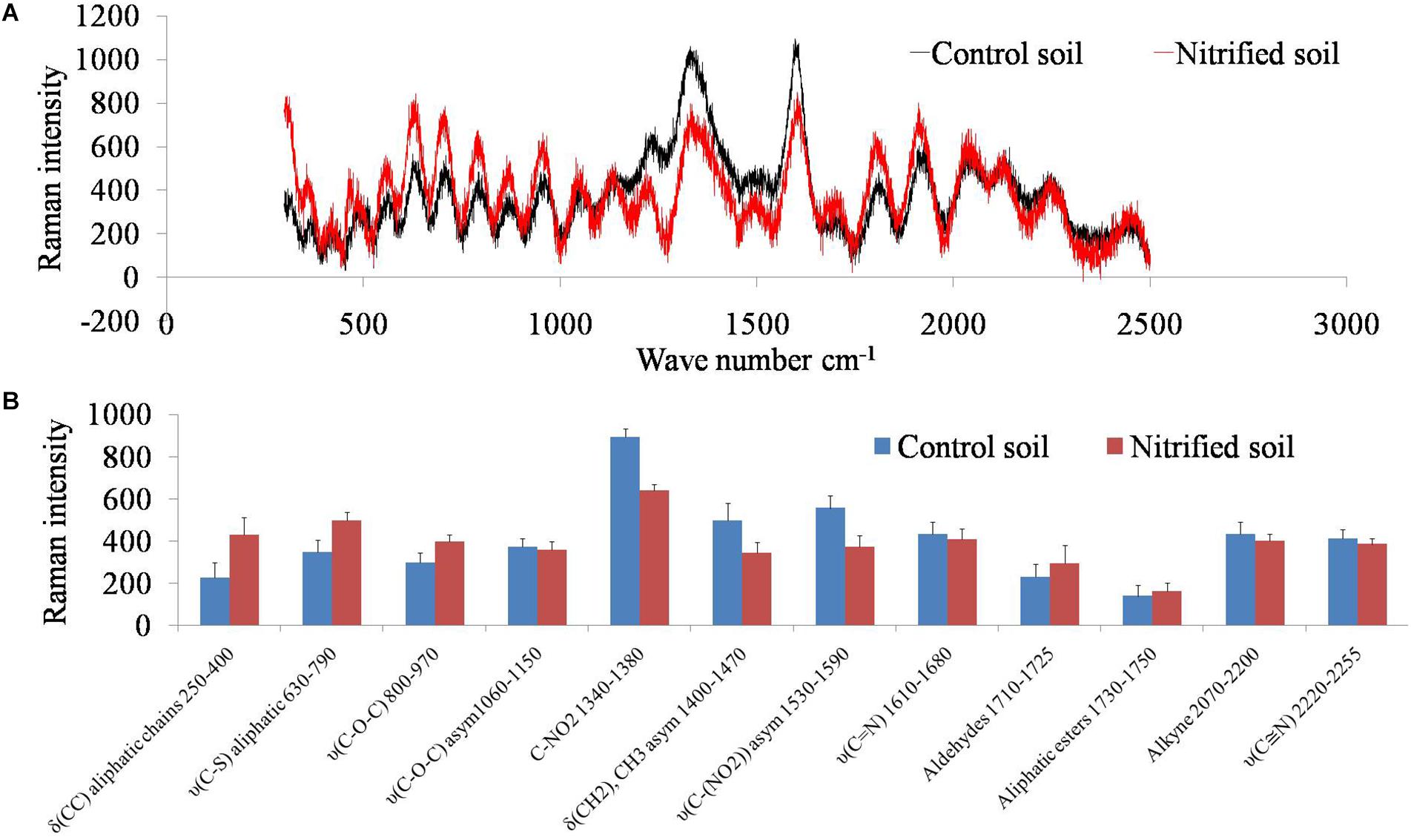

Raman Spectra of Soil in Response to Nitrification

Soil samples were scanned by a Raman spectrometer to examine how soil organic carbon changed due to the metabolism of nitrifiers (Figure 4). Nitrified soil (nitrification III) had high absorbance for the wavelengths (wavenumbers cm-1) between 500–1000 and 1500–2000. Absorbance intensity was low for the wavelengths ranging from 1200–1600. Raman intensity for the above wavelengths was plotted for both the samples (Figure 4). Nitrification increased the concentration of C–C, C–S, C–O–C molecules and decreased C–NO2, and CH2 molecules.

Figure 4. Raman spectra of the non-nitrified (control) and nitrified (after nitrification III) soil (A). The x-axis represents wavenumber cm-1 and the y-axis represents Raman intensity. Raman intensity of different functional groups (wavenumber cm-1) of nitrified (nitrification III) and control soils (B). The x-axis represents functional groups and the y-axis represents Raman intensity. Data points are arithmetic means and standard deviations of three replicates.

Production of N2O and CO2 From Soil During Nitrification

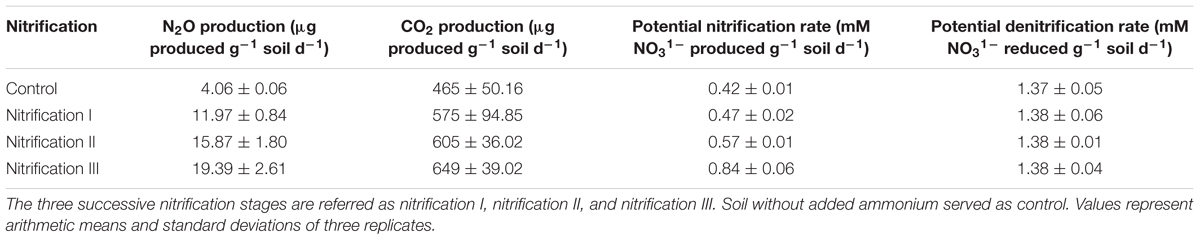

Headspace N2O and CO2 production were measured from control soil (no added nitrogen) and soil after the three nitrification stages (Table 4). N2O production rates varied from 4.06 to 19.39 μg g-1 soil d-1. The lowest rate was in control soil and the highest was in nitrification III soil. The amount of headspace CO2 varied from 465 μg g-1 soil d-1 in control soil to 649 μg g-1 soil d-1 in nitrification III soil. The values of N2O varied significantly among the treatments.

Table 4. Production rates of N2O, CO2, potential rates of nitrification and denitrification in soil in response to repeated ammonium additions.

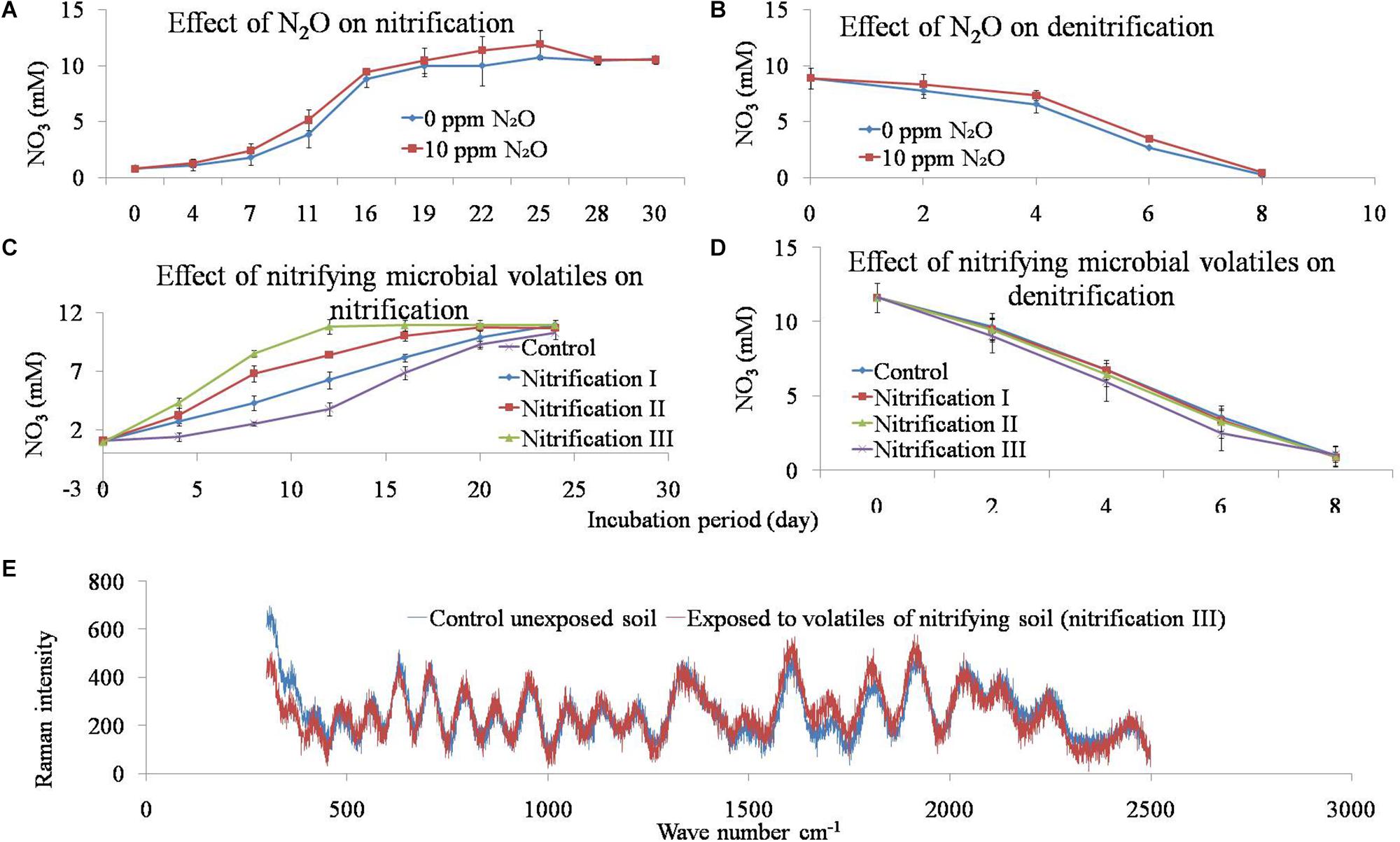

Effect of N2O and Nitrifying Microbial Volatiles on Nitrification and Denitrification

The effect of N2O on the nitrification and denitrification was evaluated by exposing soil to 0 or 10 ppm of N2O. Production of NO31- was measured during nitrification, while the decline of NO31- was measured during denitrification. Nitrification of 10 mM NH4 was completed in 3 weeks whereas the denitrificaion of NO31- (∼10 mM) was completed within 8 days. Added N2O had no significant effect on nitrification and denitrification (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Effect of N2O and microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs) on nitrification and denitrification activity in soil (A,B). The mixing ratios of N2O were either 0 or 10 ppm. To evaluate the effect of microbial volatiles (mVOCs) produced during nitrification on nitrification and denitrification activity, soils were exposed to the gas phase of soils during nitrification I, nitrification II, and nitrification III stages. Soil without exposure served as controls. After exposure, soils were incubated to determine nitrification (C) and denitrification (D) rates. The x-axis represents incubation period and the y-axis represents NO31- concentration. Data points are arithmetic means and standard deviations of three replicates. Raman spectra of soil under the influence of nitrifying microbial volatiles (E). Soils were exposed to nitrifying microbial volatiles (nitrification III) or not exposed (control). The x-axis represents wavenumber cm-1 and the y-axis represents Raman intensity. Data points are arithmetic means of three replicates.

The effect of volatiles originating from nitrification was tested on nitrification and denitrification (Figure 5). The composition of nitrifier-derived mVOCs was not evaluated in this study because the primary aim was to reveal the influence of mVOCs on nitrification and denitrification. Soils were exposed to microbial volatiles of three repeated nitrification (nitrification I, II, and III) phases. The mVOCs originating from nitrifiers significantly stimulated nitrification (Figure 5). Time required for complete nitrification of the added NH4 was significantly reduced due to the volatiles. Nitrification rates (mM NO31- produced g-1 soil d-1) varied from 0.425 in control soil to 0.844 in nitrification III soil. Nitrification and denitrification values of the controls remained unchanged over the three nitrification phases. However, mVOCs of nitrifiers did not influence denitrification. Potential denitrification rates (mM NO31- reduced g-1 soil d-1) varied from 1.37 to 1.38 with no statistical difference among the treatments (Table 4).

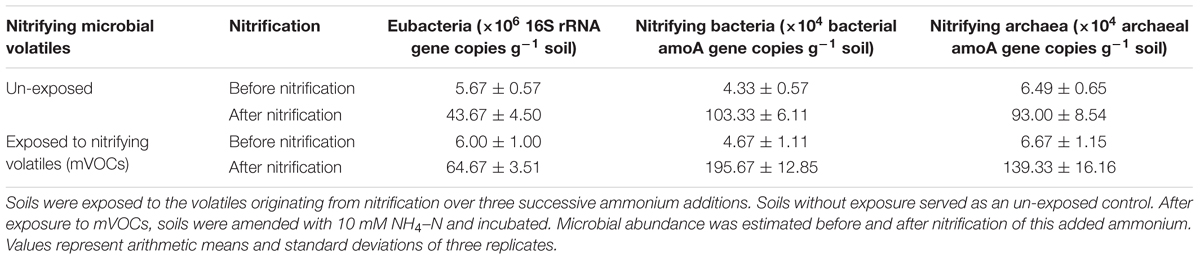

Microbial Abundance in Response to Microbial Volatiles

The effect of nitrifying mVOCs on the soil microbial abundance was estimated by quantifying the 16S rRNA genes of eubacteria, amoA genes of nitrifying bacteria, and amoA genes of nitrifying archaea. Exposure of soils to mVOCs of nitrification (nitrification III) did not increased microbial abundance in soils (Table 5). This indicated that the mVOCs were not a substantial substrate for growth of soil microorganisms. However, prior exposure of soils to mVOCs and subsequent incubation for nitrification resulted in a significant increase in the growth of nitrifying bacteria. Probably, the mVOCs may have activated the nitrifiers in some way resulting high microbial abundance.

Table 5. Effect of microbial volatiles (mVOCs) produced during nitrification on the abundance of different microbial groups.

Raman Spectra of Soil Exposed to Nitrifying Microbial Volatiles

Soils after exposure to the nitrification III and control (unexposed) treatments were analyzed by Raman spectra (Figure 5). The Raman intensity across the total wavelengths of the two samples was mostly equivalent with no apparent change.

Discussion

NO31- influences (mostly negatively) reduction of Fe3+ (Ionescu et al., 2015), SO42- (Ontiveros-Valencia et al., 2013), and methanogenesis (Rissanen et al., 2017). Denitrification is thermodynamically more favorable than the reduction of other electron acceptors (Fe3+, SO42-, CO2). This influence of inorganic nitrate on redox metabolism is well understood. However, the role of biogenic NO31- on redox metabolism is not known. Therefore, the interaction between nitrification (which produces biogenic nitrate) and redox metabolism was explored.

Soils were amended with 10 mM NH4–N and the progress of nitrification was monitored. The PNRs measured were similar to those observed in other soils (Fierer et al., 2001). The nitrification was repeated three times to generate three levels of NO31- (biogenic nitrate). Nitrification rates increased over repeated NH4–N amendments, as did the abundance of both nitrifying bacteria and archaea. After each nitrification stage, the soils were evaluated for redox metabolism. Soil samples were incubated under flooded moisture regime to test the effect of the biogenic nitrate versus inorganic nitrate (control) on redox metabolism. Biogenic nitrate inhibited reduction of electron acceptors compared to inorganic NO31-. This is reasonable as any compound or processes that inhibited denitrification will ultimately affect the reduction of subsequent terminal electron acceptors (Fe3+, SO42-, CO2).

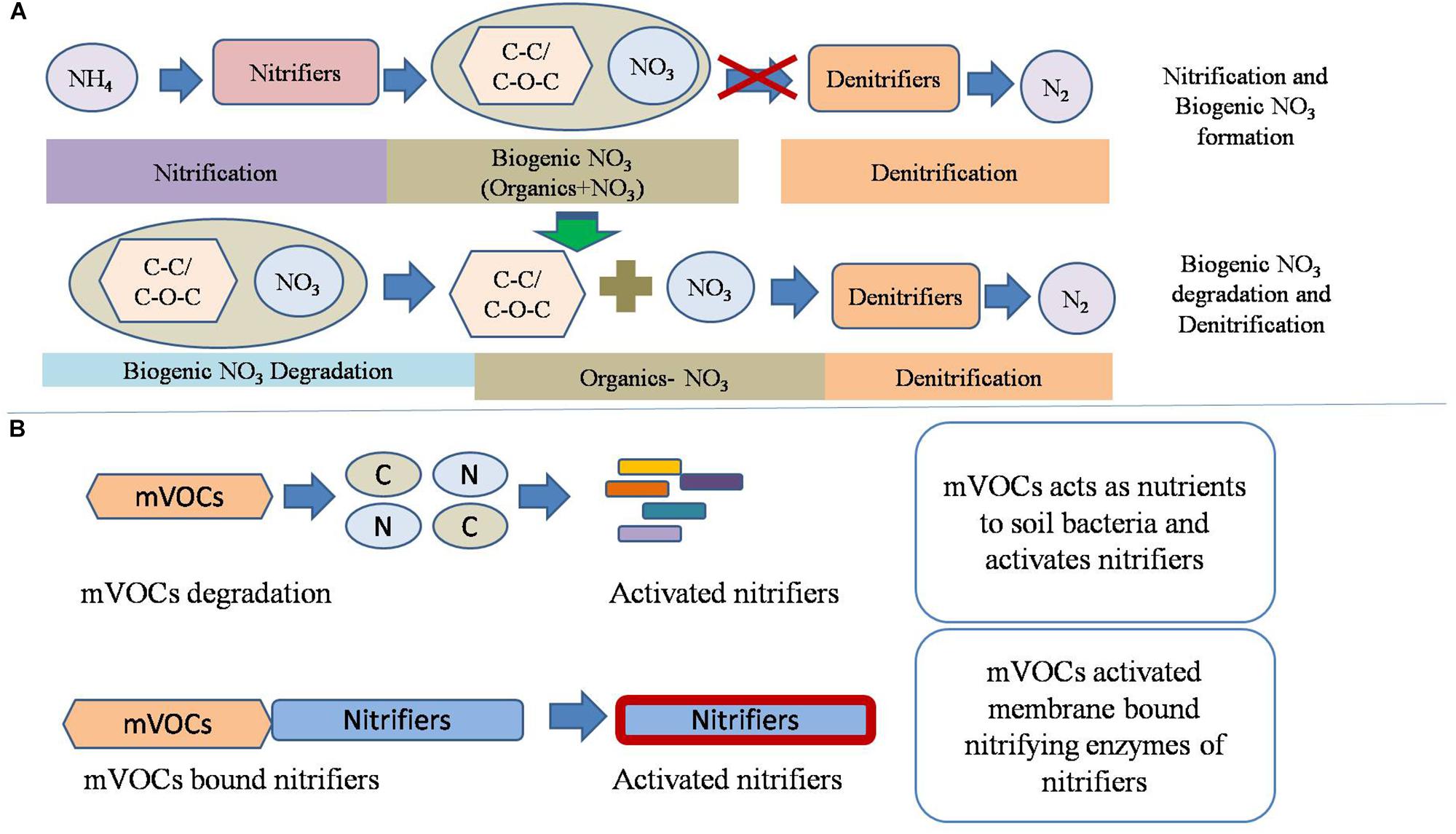

The production of biogenic nitrate via nitrification significantly (p < 0.05) inhibited redox metabolism compared to the addition of inorganic NO31-. Several soil factors may have been affected by the nitrification phase. One possibility is that nitrifiers produced biomolecules which inhibited the redox metabolism. To identify those biomolecules, soils of non-nitrified control soil and soil from the nitrification III stage were analyzed by Raman spectrometer. Soils of nitrification III were selected for Raman spectra analysis because these soils had undergone maximum nitrification. Raman spectra differentiated soil of control (with an equivalent amount of KNO3) from soils of nitrification III. Nitrification increased the abundance of functional groups including C–C, C–S, C–O–C. Spectra also indicated that nitrification decreased the amount of functional groups including C–NO2, CH2/CH3, C–NO2, C–N, esters, and alkynes. Therefore, the inhibition of redox metabolism by nitrification may have been due to the presence and/or absence of these functional groups. Under anaerobic conditions, denitrifiers oxidize aliphatic bonds (C–C and C–O–C) to CO2 through NO31- dependent oxidation (Zedelius et al., 2011). Theoretically, the occurrence of aliphatics would stimulate the redox metabolism by acting as substrates for the anaerobic microorganisms. However, in the current experiment, they were correlated with reduced redox metabolism. Probably, the biogenic nitrate was less reactive (denitrifying) than the inorganic NO31- as mentioned above. This could be due to the complex interaction or bonding between NO31- and the extracellular aliphatics. In control (non-nitrified soil), the C–NO2 functional groups were high. Spectral data indicated occurrence of biogenic nitrate in soil that has undergone nitrification. Biogenic nitrate is a complex form of nitrate containing organic molecules. The organic molecules can be short- or long-chain aliphatics. The complex structure and bonding between aliphatics and NO21- /NO31- makes it less reactive to undergo denitrification (Figure 6). It has been found that organic compounds may inhibit denitrification (Gilbert et al., 1997). Probably, the biogenic NO31- was denitrified after separation of NO31- and aliphatics, which might have been carried out by anaerobic microorganisms (Rabus et al., 2016). The processes of decomposition of the biogenic nitrate by microorganisms probably delayed the availability of NO31- for denitrification. Thus, due to the delayed denitrification, there was delay in the reduction of subsequent electron acceptors comprising Fe3+, SO42-, and CH3COO1- (CH4 production).

Figure 6. Conceptual model of nitrification and its interaction with the redox metabolism. (A) The proposed mechanism of biogenic nitrate formation and of its interaction with denitrification. Biogenic nitrates are produced by the binding of NO31- with extracellular organic compounds, possibly aliphatics. The biogenic nitrates are degraded before onset of redox metabolism under anaerobic conditions. (B) The proposed role of microbial volatile organic compounds (mVOCs) emitted by nitrifiers on soil nitrification. It is hypothesized that mVOCs acts as nutrients for proliferation of certain microbial groups and/or bind to cell membrane proteins to activate nitrifiers.

It was observed that unlike other microbial activities, nitrification progressed steadily in spite of a constant increase in NO31- concentration. Therefore, the formation of biogenic NO31- may be a mechanism used by nitrifiers to block the feedback inhibition of NO31- to nitrification. Production of CO2 did not significantly vary with nitrification potential. However, N2O production varied significantly among the treatments. Nitrous oxide was generally produced from nitrification, because active nitrification (continuous increase in the NO31- concentration) was observed over the incubation period. N2O production through denitrification cannot be ruled out, because some denitrification might have occurred in the soil microaggregates. However, NO31- production from NH4 was consistent and there was no decline in the NO31- level. Therefore, the denitrification mediated N2O production could be marginal. A follow-up experiment was carried out to determine the effect of N2O on nitrification and denitrification. It was observed that there was no significant effect of N2O on nitrification and denitrification.

Apart from CO2 and N2O, other gaseous products emitted by soil microorganisms include mVOCs. Soil microbes produce VOCs including alkenes, alcohols, ketones, terpenes, benenoids, pyrazines, acids, and esters (Lemfack et al., 2013). Microbial volatiles act as signal molecules to other microorganisms, plants, and animals (Insam and Seewald, 2010). The composition of mVOCs originating from nitrification was beyond the scope of this research, which aims only to provide primary information about the influence of mVOCs on nitrification and denitrification. Based on the current study, conceptual models were developed depicting the potential interaction of mVOCs and nitrifiers (Figure 6). This experiment suggested that mVOCs stimulated nitrification, but no effect on denitrification. Probably, the mVOCs acted as signal molecules for the nitrifiers and stimulated their activity (nitrification). Exposure of soil to mVOCs did not increase the abundance of bacteria, nitrifying bacteria, and nitrifying archaea, suggesting that mVOCs stimulated the nitrifiers by increasing cell activity. Many bacteria decompose VOCs in soil (Tyc et al., 2016). The degraded products could have played important role in the activation of microbial population, resulting in high nitrification rates compared to the unexposed control. Soils after exposure to mVOCs were further tested by Raman spectrometer to evaluate if the volatiles altered chemical composition. However, mVOCs did not change the measured soil properties. We propose that the mVOCs stimulate nitrifiers by acting as signal molecules rather than altering the soil properties.

Conclusion

The current experiment addressed four key questions about nitrification. First, how does nitrification progress under repeated N amendment? Second, how does nitrification influence redox metabolism? Third, how does the nitrate produced from nitrification (biogenic nitrate) differ from inorganic nitrate? Fourth, do the nitrifiers communicate by means of VOCs? Nitrification activity was observed under three repeated N amendments. Nitrification increased steadily in respect to the NH4–N amendment, due to increasing abundance of nitrifying bacteria and nitrifying archaea. After each nitrification stage, soils were incubated to undergo redox metabolism. An initial nitrification phase inhibited redox rates compared to the addition of an equivalent amount of inorganic NO31- (KNO3). Raman spectra of the nitrified soils revealed an increased concentration of aliphatics. Based on these observations, it was hypothesized that during nitrification, biogenic nitrates are produced by complex interaction (bonding) between NO31- and the aliphatics, and that this biogenic nitrate is less reactive toward denitrification than is inorganic nitrate. Nitrifiers emitted VOCs which stimulated nitrification. Nitrification was accelerated by both VOCs and biogenic nitrate. The current experiment mostly indicated the formation of biogenic nitrate and mVOCs by nitrifiers which regulate nitrification and redox metabolism. However, there is need of comprehensive studies on the biochemical characteristics of biogenic nitrate and mVOCs to better understand the nitrification. Further studies are also warranted with other soil types as well as under field conditions to verify complex interaction between biogenic nitrate, VOCs, and nitrification.

Author Contributions

SRM conceptualized the experiments, and drafted the manuscript. MN executed experiments and performed most of the wet chemical analysis. RP assisted in setting up experiments. UA contributed in analyzing redox moieties of soil samples. GD performed qPCR reactions to quantify functional genes. BK analyzed data statistically and contributed in drafting and revising the manuscript.

Funding

This study is part of the ICAR AMAAS and DST funded India Argentina bilateral project.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank Dr. Peter Dunfield for his input improving the manuscript.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2019.00772/full#supplementary-material

References

Alfreider, A., Baumer, A., Bogensperger, T., Posch, T., Salcher, M. M., and Summerer, M. (2017). CO2 assimilation strategies in stratified lakes: diversity and distribution patterns of chemolithoautotrophs. Environ. Microbiol. 19, 2754–2768. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13786

Arregui, L. M., and Quemada, M. (2008). Strategies to improve nitrogen use efficiency in winter cereal crops under rainfed conditions. Agron. J. 100, 277–284. doi: 10.2134/agronj2007.0187

Baek, K. H., Park, C., Oh, H.-M., Yoon, B.-D., and Kim, H.-S. (2010). Diversity and abundance of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in activated sludge treating different types of wastewater. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 20, 1128–1133. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0907.07021

Bock, E., and Wagner, M. (2013). “Oxidation of inorganic nitrogen compounds as an energy source,” in The Prokaryotes, eds E. Osenberg, E. F. DeLong, S. Lory, E. Stackebrandt, and F. Thompson (Berlin: Springer), 83–118.

Castro-Barros, C. M., Jia, M., van Loosdrecht, M. C., Volcke, E. I., and Winkler, M. K. (2017). Evaluating the potential for dissimilatory nitrate reduction by anammox bacteria for municipal wastewater treatment. Bioresour. Technol. 233, 363–372. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.02.063

Daims, H., Lebedeva, E. V., Pjevac, P., Han, P., Herbold, C., Albertsen, M., et al. (2015). Complete nitrification by Nitrospira bacteria. Nature 528:504. doi: 10.1038/nature16461

Dolinšek, J., Lagkouvardos, I., Wanek, W., Wagner, M., and Daims, H. (2013). Interactions of nitrifying bacteria and heterotrophs: identification of a Micavibrio-like putative predator of Nitrospira spp. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 2027–2037. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03408-12

Fierer, N., Schimel, J. P., Cates, R. G., and Zou, J. (2001). Influence of balsam poplar tannin fractions on carbon and nitrogen dynamics in Alaskan taiga floodplain soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 33, 1827–1839. doi: 10.1016/S0038-0717(01)00111-0

Flood, M., Frabutt, D., Floyd, D., Powers, A., Ezegwe, U., Devol, A., et al. (2015). Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria and archaea in sediments of the Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Technol. 36, 124–135. doi: 10.1080/09593330.2014.942385

Gilbert, F., Stora, G., Bonin, P., LeDréau, Y., Mille, G., and Bertrand, J.-C. (1997). Hydrocarbon influence on denitrification in bioturbated Mediterranean coastal sediments. Hydrobiologia 345, 67–77. doi: 10.1023/A:1002931432250

Gribaldo, S., Poole, A. M., Daubin, V., Forterre, P., and Brochier-Armanet, C. (2010). The origin of eukaryotes and their relationship with the Archaea: are we at a phylogenomic impasse? Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 743–752. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2426

Guizani, C., Haddad, K., Limousy, L., and Jeguirim, M. (2017). New insights on the structural evolution of biomass char upon pyrolysis as revealed by the Raman spectroscopy and elemental analysis. Carbon 119, 519–521. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2017.04.078

Han, S., Luo, X., Liao, H., Nie, H., Chen, W., and Huang, Q. (2017). Nitrospira are more sensitive than Nitrobacter to land management in acid, fertilized soils of a rapeseed-rice rotation field trial. Sci. Total Environ. 599, 135–144. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2017.04.086

Ihaka, R., and Gentleman, R. (1996). R: a language for data analysis and graphics. J. Comput. Graph. Stat. 5, 299–314.

Insam, H., and Seewald, M. S. (2010). Volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in soils. Biol. Fertil. Soils 46, 199–213. doi: 10.1007/s00374-010-0442-3

Ionescu, D., Heim, C., Polerecky, L., Ramette, A., Haeusler, S., Bizic-Ionescu, M., et al. (2015). Diversity of iron oxidizing and reducing bacteria in flow reactors in the Äspö hard rock laboratory. Geomicrobiol. J. 32, 207–220. doi: 10.1080/01490451.2014.884196

Isobe, K., Koba, K., Suwa, Y., Ikutani, J., Fang, Y., Yoh, M., et al. (2012). High abundance of ammonia-oxidizing archaea in acidified subtropical forest soils in southern China after long-term N deposition. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 80, 193–203. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2011.01294.x

Leininger, S., Urich, T., Schloter, M., Schwark, L., Qi, J., Nicol, G. W., et al. (2006). Archaea predominate among ammonia-oxidizing prokaryotes in soils. Nature 442, 806–809. doi: 10.1038/nature04983

Lemfack, M. C., Nickel, J., Dunkel, M., Preissner, R., and Piechulla, B. (2013). mVOC: a database of microbial volatiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 42, D744–D748. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkt1250

Li, J., Wei, J., Ngo, H. H., Guo, W., Liu, H., Du, B., et al. (2018). Characterization of soluble microbial products in a partial nitrification sequencing batch biofilm reactor treating high ammonia nitrogen wastewater. Bioresour. Technol. 249, 241–246. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2017.10.013

Li, Y., Chapman, S. J., Nicol, G. W., and Yao, H. (2018). Nitrification and nitrifiers in acidic soils. Soil Biol. Biochem. 116, 290–301. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2017.10.023

Liimatainen, M., Voigt, C., Martikainen, P. J., Hytönen, J., Regina, K., Óskarsson, H., et al. (2018). Factors controlling nitrous oxide emissions from managed northern peat soils with low carbon to nitrogen ratio. Soil Biol. Biochem. 122, 186–195. doi: 10.1016/j.soilbio.2018.04.006

Lliros, M., Ingeoglu, O., Garcia-Armisen, T., Auguet, J. C., Morana, C., Darchambeau, F., et al. (2014). “Ammonia oxidising Archaea in the OMZ of a freshwater African Lake,” in Proceedings of the 46th International Liège Colloquium, Low Oxygen Environments in Marine, Estuarine and Fresh Waters, (Liège).

Mutlu, M. B., and Guven, K. (2011). Detection of prokaryotic microbial communities of Çamaltı Saltern, Turkey, by fluorescein in situ hybridization and real-time PCR. Turk. J. Biol. 35, 687–695.

Nelson, M. B., Martiny, A. C., and Martiny, J. B. (2016). Global biogeography of microbial nitrogen-cycling traits in soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 8033–8040. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1601070113

Okano, Y., Hristova, K. R., Leutenegger, C. M., Jackson, L. E., Denison, R. F., Gebreyesus, B., et al. (2004). Application of real-time PCR to study effects of ammonium on population size of ammonia-oxidizing bacteria in soil. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 70, 1008–1016. doi: 10.1128/AEM.70.2.1008-1016.2004

Ontiveros-Valencia, A., Ilhan, Z. E., Kang, D.-W., Rittmann, B., and Krajmalnik-Brown, R. (2013). Phylogenetic analysis of nitrate-and sulfate-reducing bacteria in a hydrogen-fed biofilm. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 85, 158–167. doi: 10.1111/1574-6941.12107

Pan, K.-L., Gao, J.-F., Li, H.-Y., Fan, X.-Y., Li, D.-C., and Jiang, H. (2018). Ammonia-oxidizing bacteria dominate ammonia oxidation in a full-scale wastewater treatment plant revealed by DNA-based stable isotope probing. Bioresour. Technol. 256, 152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2018.02.012

Rabus, R., Boll, M., Heider, J., Meckenstock, R. U., Buckel, W., Einsle, O., et al. (2016). Anaerobic microbial degradation of hydrocarbons: from enzymatic reactions to the environment. J. Mol. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 26, 5–28. doi: 10.1159/000443997

Radax, R., Hoffmann, F., Rapp, H. T., Leininger, S., and Schleper, C. (2012). Ammonia-oxidizing archaea as main drivers of nitrification in cold-water sponges. Environ. Microbiol. 14, 909–923. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02661.x

Rissanen, A. J., Karvinen, A., Nykänen, H., Peura, S., Tiirola, M., Mäki, A., et al. (2017). Effects of alternative electron acceptors on the activity and community structure of methane-producing and-consuming microbes in the sediments of two shallow boreal lakes. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 93, 1–16. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fix078

Rubio-Asensio, J. S., López-Berenguer, C., García-de la Garma, J., Burger, M., and Bloom, A. J. (2014). “Root strategies for nitrate assimilation,” in Root Engineering, eds A. Morte and A. Varma (Berlin: Springer), 251–267.

Schmidt, E. L., and Belser, L. W. (1982). Nitrifying bacteria. Methods Soil Anal. Part 2, 1027–1042.

Searle, P. L. (1979). Measurement of adsorbed sulphate in soils—effects of varying soil: extractant ratios and methods of measurement. N. Z. J. Agric. Res. 22, 287–290. doi: 10.1080/00288233.1979.10430749

Socrates, G. (2004). Infrared and Raman Characteristic Group Frequencies: Tables and Charts. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons.

Stookey, L. L. (1970). Ferrozine - a new spectrophotometric reagent for iron. Anal. Chem. 42, 779–781. doi: 10.1021/ac60289a016

Tourna, M., Stieglmeier, M., Spang, A., Könneke, M., Schintlmeister, A., Urich, T., et al. (2011). Nitrososphaera viennensis, an ammonia oxidizing archaeon from soil. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 8420–8425. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1013488108

Tyc, O., Song, C., Dickschat, J. S., Vos, M., and Garbeva, P. (2016). The ecological role of volatile and soluble secondary metabolites produced by soil bacteria. Trends Microbiol. 25, 280–292. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2016.12.002

van Kessel, M. A., Speth, D. R., Albertsen, M., Nielsen, P. H., den Camp, H. J. O., Kartal, B., et al. (2015). Complete nitrification by a single microorganism. Nature 528:555. doi: 10.1038/nature16459

Weber, E. B., Lehtovirta-Morley, L. E., Prosser, J. I., and Gubry-Rangin, C. (2015). Ammonia oxidation is not required for growth of Group 1.1 c soil Thaumarchaeota. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 91:fiv001. doi: 10.1093/femsec/fiv001

Wuchter, C., Abbas, B., Coolen, M. J., Herfort, L., van Bleijswijk, J., Timmers, P., et al. (2006). Archaeal nitrification in the ocean. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 103, 12317–12322. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0600756103

Zedelius, J., Rabus, R., Grundmann, O., Werner, I., Brodkorb, D., Schreiber, F., et al. (2011). Alkane degradation under anoxic conditions by a nitrate-reducing bacterium with possible involvement of the electron acceptor in substrate activation. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 3, 125–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1758-2229.2010.00198.x

Keywords: nitrification, biogenic nitrate, redox metabolism, mVOCs, 16S rRNA, amoA

Citation: Mohanty SR, Nagarjuna M, Parmar R, Ahirwar U, Patra A, Dubey G and Kollah B (2019) Nitrification Rates Are Affected by Biogenic Nitrate and Volatile Organic Compounds in Agricultural Soils. Front. Microbiol. 10:772. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00772

Received: 15 September 2018; Accepted: 26 March 2019;

Published: 14 May 2019.

Edited by:

Suvendu Das, Gyeongsang National University, South KoreaReviewed by:

Kristof Brenzinger, Netherlands Institute of Ecology (NIOO-KNAW), NetherlandsYe Deng, Research Center for Eco-Environmental Sciences (CAS), China

Copyright © 2019 Mohanty, Nagarjuna, Parmar, Ahirwar, Patra, Dubey and Kollah. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Santosh Ranjan Mohanty, bW9oYW50eXdpc2NAZ21haWwuY29t; c2FudG9zaC5tb2hhbnR5QGljYXIuZ292Lmlu

Santosh Ranjan Mohanty

Santosh Ranjan Mohanty Mounish Nagarjuna

Mounish Nagarjuna Bharati Kollah

Bharati Kollah