95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Microbiol. , 07 August 2018

Sec. Microbial Physiology and Metabolism

Volume 9 - 2018 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2018.01801

This article is part of the Research Topic Engineering the Microbial Platform for the Production of Biologics and Small-Molecule Medicines View all 17 articles

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides, or RiPPs, which have mainly isolated from microbes as well as plants and animals, are an ever-expanding group of peptidic natural products with diverse chemical structures and biological activities. They have emerged as a major category of secondary metabolites partly due to a myriad of microbial genome sequencing endeavors and the availability of genome mining software in the past two decades. Heterologous expression of RiPP gene clusters mined from microbial genomes, which are often silent in native producers, in surrogate hosts such as Escherichia coli and Streptomyces strains can be an effective way to elucidate encoded peptides and produce novel derivatives. Emerging strategies have been developed to facilitate the success of the heterologous expression by targeting multiple synthetic biology levels, including individual proteins, pathways, metabolic flux and hosts. This review describes recent advances in heterologous production of RiPPs, mainly from microbes, with a focus on E. coli and Streptomyces strains as the surrogate hosts.

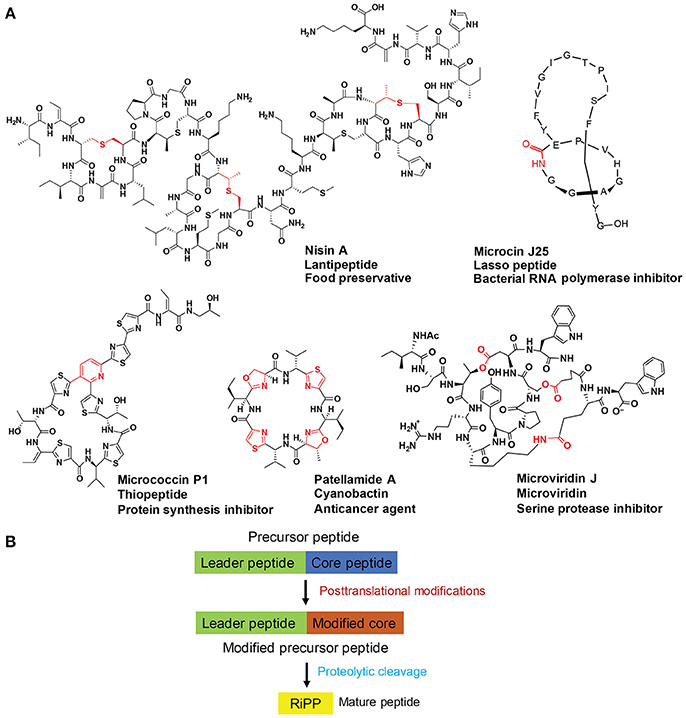

Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs) are a large group of natural products with a high degree of structural diversity and a wide variety of bioactivities (Figure 1A; Arnison et al., 2013). So far, over 20 different families of RiPPs have been discovered, each carrying unique chemical features (Ortega and van Der Donk, 2016). A biosynthetic logic for RiPPs has emerged and can be simplified as the post-translational modification (PTM) of ribosomally synthesized precursor peptides (Figure 1B; Arnison et al., 2013). An ever-growing list of PTMs expand chemical functionality and often impart metabolic and chemical stability upon precursor peptides. One precursor peptide usually contains the leader peptide (in rare cases C-terminal, named as follower peptide) N-terminal to the core peptide. The leader peptide binds to and guides biosynthetic enzymes for PTMs on the core peptide and is eventually removed from the modified core peptides by proteases. The entire sequence of the core peptide is generally retained in the final structures of RiPPs and can carry multiple variable sites. As such, the separation of substrate recognition and catalysis enables a concise RiPP biosynthetic route, possessing an evolutionary advantage of accessing high chemical diversity at low genetic cost.

Figure 1. (A) Representative structures of five select RiPP families with diverse bioactivities. Post-translational modification(s) on each structure are highlighted in red. (B) A schematic depiction of RiPP biosynthesis. Precursor peptide typically contains the leader peptide (in green) followed by the core peptide (in blue). Modifications of the core peptides (in brown) are guided by the leader peptides that interact with processing enzymes. Proteolytic release of the leader peptides then gives rise to mature RiPPs (in yellow).

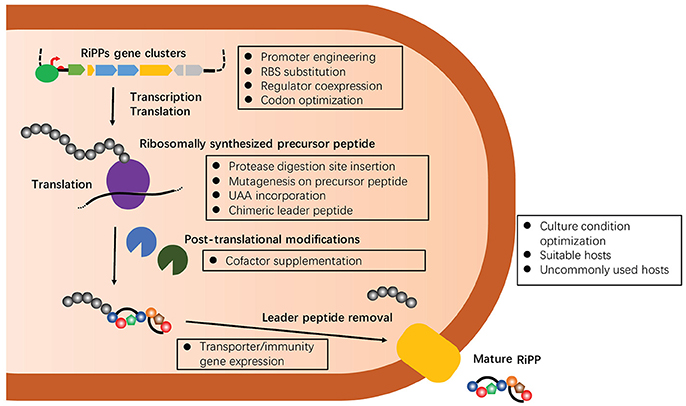

As a consequence of their ribosomal origin, the chemical structures of RiPPs are more predictable from genomic data than other families of natural products, making RiPPs an attractive target of genome-driven natural product discovery efforts. Compared to conventional “top-down” approaches, the starting point of the genome-driven approach is genome sequences that have exponentially grown over the past decade. Many specialized bioinformatic tools have been developed for identifying RiPPs biosynthetic gene clusters, such as AntiSMASH (Weber et al., 2015), PRISM (Skinnider et al., 2017), SMURF (Khaldi et al., 2010), and more recently RODEO (Tietz et al., 2017). However, there are many technical challenges to translate the identified clusters into chemical entities, rendering the genome-driven approach far from being a panacea for accessing the chemical space that natural products occupy (Luo et al., 2014). Indeed, the diversity and complexity of PTMs, which are often essential for bioactivity of RiPPs, are not readily identifiable on the core peptides as our understanding of biosynthetic enzymes, particularly their substrate specificity and regio-, stereo-, and chemo-selectivity, remains limited (Arnison et al., 2013). On the other hand, the structural determination of RiPPs is often challenged with their no-to-low isolation yields from samples collected from the field or cultured under laboratory conditions (Smith et al., 2018). Over the past decade, many approaches have been developed to address this critical, major issue of the genome-driven approach, including the activation of silent biosynthetic gene clusters (e.g., modification of fermentation methods and engineering of original producers), heterologous expression using a genetically tractable surrogate host, and in vitro reconstruction (Chiang et al., 2011; Abdelmohsen et al., 2015; Reen et al., 2015; Ren et al., 2017). Among them, heterologous expression of RiPPs in surrogate hosts, commonly Escherichia coli and Streptomyces strains, has so far been one of the most successful methods to elucidate cryptic gene clusters and discover new RiPPs (Ortega and van Der Donk, 2016). Furthermore, heterologous production can effectively harvest the promiscuity of RiPP biosynthetic systems to produce designed analogs through genetic engineering of precursor peptides. Importantly, many emerging strategies have been developed to improve the success of heterologous production of RiPPs over the past several years, mainly focusing on the manipulation of individual proteins, pathways, metabolic flux and hosts (Figure 2). Herein, this review describes the details of these strategies ensuring and expanding the heterologous expression approach to discover and develop RiPPs. Representative examples of heterologous expression of each major family of RiPPs were summarized in Table 1. Of note, thousands of antimicrobial peptides have been isolated from a variety of organisms (Deng et al., 2017), and this manuscript excluded their heterologous production in discussions.

Figure 2. A summary of multiple emerging strategies that target on manipulating individual proteins, pathways, metabolic flux or hosts to improve the success of heterologous expression of RiPPs. All of these strategies will be discussed below with select recent examples.

A RiPP gene cluster commonly comprises of all essential genes for the production of RiPP. Manipulation of the pathway-specific components allows precise and rational improvement of RiPP production and minimizes potential perturbation of the holistic metabolism of the heterologous host. Detailed information regarding the function, timing, specificity and regulation on the pathway can also be extracted via this approach. From a synthetic biology standpoint, here we use representative examples to describe different strategies used to manipulate RiPP biosynthetic pathways for successful heterologous expression.

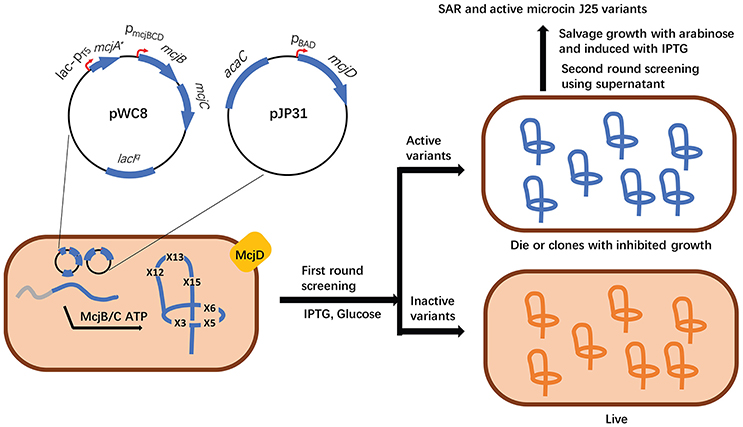

Altered transcription levels of biosynthetic genes are commonly observed when they are introduced into heterologous hosts. Genetic engineering of a biosynthetic gene cluster by the introduction of one or more constitutive or inducible promoters has proved very effective for the heterologous production of different RiPP families. Importantly, a number of well-characterized promoters of commonly used hosts (e.g., E. coli and Streptomyces strains) (De Mey et al., 2007; Li et al., 2015; Myronovskyi and Luzhetskyy, 2016) have been available to enable this synthetic biology approach. For example, lichenicidin is a two-component lantibiotic produced by Bacillus licheniformis I89, and its heterologous production from the native gene cluster in E. coli BLic5 led to a significantly lowered yield compared with the native producer (Table 1; Caetano et al., 2011a,b). By contrast, driving the expression of each biosynthetic gene by a strong T7 promoter resulted in a yield of lichenicidin up to 100 times higher than B. licheniformis I89 (Kuthning et al., 2015). In another example, Staphylococcus warneri ISK-1 produces a lantibiotic nukacin ISK-1 (Sashihara et al., 2000) but the heterologous expression of its gene cluster in S. carnosus TM300 and Lactobacillus plantarum ATCC 14917T failed to produce any natural product (Aso et al., 2004). Aso et al. addressed this problem through the identification of a cognate response activator and by driving the cluster expression with a nisin-inducible promoter PnisA (Table 1; Aso et al., 2004). Likewise, the utilization of a proper promoter was also essential for the successful production of a macrocyclic peptide telomestatin (Table 1). Initially, a xylose-inducible promoter (xylAp) was used to drive the expression of its gene cluster in the highly engineered Streptomyces avermitilis SUKA17 (Komatsu et al., 2013) but yielded no targeted molecule. It was later speculated that the transcription of the gene cluster should be activated during the late logarithmic phase of cell growth. Accordingly, the replacement of xylAp with the olmRp promoter led to the production of telomestatin in S. avermitilis SUKA17 (Amagai et al., 2017), clearly indicating the essentiality and importance of temporal control of gene expression in the successful production of natural products. Other remarkable examples of applying constitutive or inducible promoters to promote the success of RiPP heterologous expression include the complete refactoring of the cyanobactin patellamide pathway for its expression in E. coli Rosetta2 (DE3) (Donia et al., 2006), the use of inducible araPBAD promoter to drive the entire operon of a lasso peptide in E. coli BL21 (DE3) (Metelev et al., 2013), increased production of thiopeptides GE2270 and lactazole A in Streptomyces hosts after introduction of the constitutive ermE* promoter (Flinspach et al., 2014) and by a strong promoter (Hayashi et al., 2014), respectively (Table 1). Of note, the Link group constructed an expression system with two orthogonally inducible promoters to permit a separate control of the production and the export/immunity of lasso peptide MccJ25 in E. coli (Table 1, Figure 3). This elegant design enabled high-throughput screening of saturation mutagenesis libraries of the ring and β-hairpin tail regions of MccJ25 to obtain new insights to its structure-activity relationship (Pan and Link, 2011).

Figure 3. High throughput discovery of functional microcin J25 variants with multiple amino acid substitutions was enabled by an orthogonally inducible system which separately controls the production and export/immunity of mature RiPPs. More specifically, the expression of the precursor gene mcjA and the transporter gene mcjD was independently induced by IPTG and arabinose, respectively. In the noninduced state, leaky expression leads to the low levels of both McjA and McjD (left). When IPTG and glucose are added, the expression of mcjA mutants is highly induced, but not mcjD, resulting in cytoplasmic accumulation of McjAs. If McjAs are processed into mature MccJ25 variants with antibacterial activity, accumulated lasso peptides will inhibit the growth of the host cell (top right). The poor growth of these cells will be salvaged by the addition of arabinose to overexpress McjD. By contrast, inactive MccJ25 variants will have no inhibitory effect on the cell growth (bottom right).

A ribosomal binding site (RBS) is critical in initiating the translation of many downstream genes. Its efficiency depends on the core Shine-Dalgarno (SD) sequence, the surrounding secondary structure, and the spacing between the SD sequence and the start codon AUG. Upon translation initiation, the 3′-sequence of the 16S rRNA complementarily pairs with the SD sequence in the RBS. Over millions of years of evolution, microbes have created and utilized a diverse set of RBSs to control protein translation (Omotajo et al., 2015), which is also employed to regulate the production of secondary metabolites. As such, RBSs are an important component part of synthetic biology applications including the heterologous production of RiPPs and other families of natural products (Bai et al., 2015). For example, the incorporation of optimized E. coli RBSs has proven to be an efficient way to significantly increase the yields of multiple lasso peptides, including astexin–1,−2, and−3 (Maksimov et al., 2012; Maksimov and Link, 2013), capistruin (Pan et al., 2012), and caulosegnin (Table 1) (Hegemann et al., 2013a). In a more inclusive example, Hegemann et al. cloned the gene clusters of lasso peptides from various sources into the expression vector pET41a, and included a strong E. coli RBS in the intergenic region between their precursor gene(s) and the genes encoding processing enzymes (Table 1; Hegemann et al., 2013b). This design increased the production yields of almost all expressed lasso peptides by 1.8- to 84.5-folds, although the deletion of extra precursor peptides might also contribute to the yield improvement in some cases (Hegemann et al., 2013b).

RiPP biosynthesis recruits a rapidly expanding list of functionally diverse enzymes to furnish structural and functional diversity (Arnison et al., 2013). The reactions of some RiPP biosynthetic enzymes require cofactors/co-substrates that may not be (or insufficiently) available in the surrogate host, leading to suboptimal production of targeted RiPPs. Therefore, optimal heterologous expression of RiPPs sometimes can be achieved by targeting cofactors/co-substrates of essential processing enzymes. For instance, NisB is a dehydratase involved in the biosynthesis of the food preservative nisin and its catalytic function requires glutamyl-tRNAGlu as a co-substrate, uncommon to RiPP processing enzymes (Ortega et al., 2016). Accordingly, increasing the cellular availability of Microbispora sp. 107891 glutamyl-tRNAGlu in E. coli was attempted to enhance the catalytic activity of MibB, a homolog of NisB involved in the biosynthesis of NAI-107. This study led to the production of NAI-107 analogs containing up to seven dehydrations, in contrast to nearly no dehydration when having no expressed Microbispora sp. 107891 glutamyl-tRNAGlu (Table 1) (Ortega et al., 2016). In a more pronounced example, the Schmidt group found that the addition of cysteine (5–10 mM) to the culture media, along with minor process changes, increased the yield of cyanobactin patellins by 150-folds (Table 1; Tianero et al., 2016). It was proposed that sulfide derived from cysteine specifically modulates the substrate preference of cyanobactin processing enzymes, enabling post-translational control of product formation in vivo. Moreover, elevating the availability of the isoprene precursor, which is required by the pathway-specific prenyltransferase (Mcintosh et al., 2011), gave rise to an additional ~18-fold increase of patellin yield in E. coli (Table 1).

Due to the different abundance of tRNAs in various hosts, each organism has its own codon preference. Thus, codon optimization of biosynthetic genes proves to be a good strategy to achieve optimal heterologous expression. For example, the biosynthetic genes of geobacillin I, a nisin analog encoded by the thermophilic bacterium Geobacillus thermodenitrificans NG80-2, were codon-optimized before their introduction to E. coli for heterologous expression (Garg et al., 2012). Likewise, genes cylLL, cylLS, and cylM encoding the enterococcal cytolysin were synthesized with codon optimization for use in E. coli (Tang and Van Der Donk, 2013). Notably, in the heterologous expression of patellamides in E. coli, much lower yield was observed with vectors that were not codon-optimized (Schmidt et al., 2005).

Despite the brevity of RiPP biosynthetic logic (Figure 1B), their gene clusters often encode components for precursor peptides, processing enzymes, resistance mechanism and regulators, the same as other families of natural products (e.g., polyketides and nonribosomal peptides) (Ortega and van Der Donk, 2016). Targeting any of these components, particularly the regulators of RiPP biosynthetic pathways, can favor the success of RiPP heterologous production. A comprehensive review on gene-regulatory mechanisms operating in RiPPs biosynthesis was recently reported elsewhere (Bartholomae et al., 2017). We highlighted here an example about the essentiality of a pathway-specific regulator to successful RiPP heterologous expression. The biosynthetic gene cluster of thiopeptide GE2270 (pbt) from Planobispora rosea ATCC 53733 previously failed to express the natural product in several Streptomyces hosts (Table 1; Tocchetti et al., 2013). In a recent report, Flinspach et al. revealed that the expression of PbtR, a TetR family of transcriptional regulator, is essential to the successful heterologous production in S. coelicolor M1146 (Flinspach et al., 2014).

Natural products are known to possess biological activities that target organisms in the same environmental niches, thereby offering survival benefits (Behie et al., 2017). To avoid self-toxicity, the producers accordingly evolve many different types of resistance mechanisms (e.g., transporters, chemical modification and target modification), often embedded in the natural product gene clusters (Jia et al., 2017; Almabruk et al., 2018). Expectedly, resistance mechanisms can offer a way to regulate the production of natural products, including RiPPs. For example, the biosynthesis of the lantibiotic nisin in Lactococcus lactis requires the dehydratase NisB, the cyclase NisC, the ABC-type transporter NisT, and the protease NisP, which together convert the precursor peptide NisA into the final product (Cheigh and Pyun, 2005). NisT forms a protein complex with NisB, C and P to effectively export bioactive nisin after its formation. Indeed, no secreted nisin was detected from the medium of a L. lactis mutant lacking the nisT gene, while the expression of nisABCP in this strain resulted in a considerable growth inhibition due to the intracellular accumulation of nisin (Table 1; Van Den Berg Van Saparoea et al., 2008). This example illustrates the necessity of a resistance mechanism to protect RiPP native producers. The same is likely true to surrogate hosts. For example, the ABC transporter MdnE was reported to be crucial for the successful production of a unique RiPP family, cyanobacterial tricyclic microviridins, in E. coli (Table 1; Weiz et al., 2011). In this case, MdnE might also act as a scaffold protein to guide the biosynthesis (Weiz et al., 2011). In another example, the multidrug transporter BotT of a bottromycin biosynthetic pathway is key to produce this antibiotic peptide in the surrogate host (Huo et al., 2012). Overexpression of the botT gene driven by a strong PermE* promoter in S. coelicolor host enhanced the production titer by 20 times compared to the control with the unmodified cluster. In addition to transporter genes, other resistance-imparting genes can also be used to boost the heterologous production of RiPPs. For instance, the heterologous production of the bacteriocin enterocin A (EntA) was accomplished by fusing a Sec-dependent signal peptide (SPusp45) with mature EntA and coexpressing the EntA immunity gene entiA (Table 1; Jiménez et al., 2015). EntiA protects the producing strain by forming a strong complex with the receptor protein, mannose phosphotransferase system, to avoid the toxicity. These manipulations led to a 4.9-fold higher production of EntA than the native producer (Jiménez et al., 2015).

For the successful heterologous expression of RiPPs, one common hurdle is the lack of proper peptidases in the surrogate host to remove the leader peptide after finishing modifications on the core peptide (Bindman et al., 2015). Indeed, a number of RiPP gene clusters do not encode a protease dedicated to the removal of the leader peptide. The sequences of the linkers between the leader and core peptides also provide limiting information for the identification of such a protease from the genomes of native producers. To address this issue, the digestion site of a well-characterized, commercially available protease, such as GluC (Tang and Van Der Donk, 2012; Zhao and Van Der Donk, 2016;), trypsin (Himes et al., 2016), and C39 protease domain of the ABC transporter (Wang et al., 2014), can be engineered into the linker for the in vitro proteolytic release of the leader peptide from the matured precursor peptides isolated from heterologous hosts. As another approach, the van der Donk group genetically incorporated unnatural amino acids (UAAs) hydroxyl acids in the first position of a lanthipeptide by using a pyrrolysyl-tRNA synthetase-tRNA pair in E. coli (Table 1; Bindman et al., 2015). The installation of hydroxyl acid leads to an ester linkage between the leader and core peptides, which is readily cleavable by simple hydrolysis.

The majority of RiPPs precursor peptides comprise of the leader peptide region for the interactions with processing enzymes and the core peptide region that becomes the final products after chemical modification and proteolytic removal of the leader peptide (Arnison et al., 2013). The core region often carries multiple sequence variations that are tolerated by processing enzymes in modifications, providing opportunities to expand the chemical diversity of RiPPs. Indeed, genetic engineering of the core peptides of multiple RiPP families has led to impressive successes in exploring new chemical space for therapeutic applications. Two strategies have commonly been employed to diversify core peptide sequences, including single-site saturation mutagenesis (Young et al., 2012) and multiple-site sequence randomization (Ruffner et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2018). The first strategy is advantageous to screen small-size libraries but can miss desirable mutants that require multiple mutations on the core peptides. By contrast, the second strategy in principle explores the broadest chemical space covered by large libraries (e.g., 106-109 members), which is favored in drug discovery and development research. However, the success of this strategy depends on all three following factors, (1) the expression of all precursor peptide mutants in the host, (2) the proper processing of all mutants to generate large numbers of RiPP analogs, and (3) the high throughput screening methods to identify desirable compounds. In one recent example, Ruffner et al. employed the second strategy to randomly mutate the core peptide (TSIAPFC) of cyanobactin trunkamide (Table 1; Ruffner et al., 2015), whose processing enzymes are known to exhibit unusually relaxed sequence selectivity (Sardar et al., 2015). They prepared three double mutant libraries (XXIAPFC, TSXXPFC, and TSIXPXC) and a quadruple mutant library (XSXXPXC) in E. coli using the degenerate codon NNK. From the double mutant libraries (theoretically, 1,200 unique sequences in each library), they randomly screened a total of 460 clones, found 260 full-length precursor peptides, and detected 150 trunkamide analogs, giving a 33% success rate. The quadruple mutant library had the potential to produce 160,000 different sequences. The authors assessed the quality of this library by screening randomly picked 96 clones, found 65 full-length precursor peptides, and detected nine trunkamide analogs. The lower success rate (9.4%) of the quadruple mutant library may correlate with the selectivity of processing enzymes. In this regard, the van der Donk group recently leveraged the remarkable substrate tolerance of a lanthipeptide synthetase ProcM to generate a genetically encoded lanthipeptide library (Yang et al., 2018). They first randomized 10 positions of the core peptide of the precursor peptide ProcA2.8 (Table 1) (AACXXXXXSMPPSXXXXXC) using the NWY codon that encodes eight amino acids, leading to a 1.07 × 109 library. Limited by the transformation efficiency of E. coli, they obtained ~106 clones, 99.7% of which produced unique peptide sequences. Screening of 33 randomly selected clones led to identify 33 cyclized samples, illustrating the impressive versatility and substrate flexibility of ProcM. The authors then screened all 106 lanthipeptides using a cell survival-based high throughput assay and identified one potent inhibitor of HIV p6 protein (Yang et al., 2018). In addition to the use of E. coli as a host to produce mutated RiPPs, both yeast display and phage display have recently been used to generate libraries of 106 lanthipeptides for screening for new bioactive analogs (Urban et al., 2017; Hetrick et al., 2018). These two well-characterized platforms can find more applications in expanding the chemical space of other RiPP families by the sequence randomization strategy.

In addition to 20 proteinogenic amino acids, a variety of UAAs can be used to expand the chemical diversity of RiPPs (Young and Schultz, 2010). This strategy has demonstrated its success with multiple RiPP families, including lantipeptide (Nagao et al., 2005; Oldach et al., 2012; Bindman et al., 2015; Kuthning et al., 2016; Lopatniuk et al., 2017; Zambaldo et al., 2017), lasso peptide (Piscotta et al., 2015), cyanobactin (Tianero et al., 2012), and sactipeptide (Himes et al., 2016). However, these unnatural RiPP analogs showed no significant improvement of their bioactivities possibly due to the relatively small extent of chemical expansion brought by a single UAA on a single position. However, coupled with the directed evolution of targeted core peptides, e.g., multiple-site randomization as described above, this strategy can generate new-to-nature RiPP analogs with enhanced structural and functional diversity.

RiPP precursor peptides physically separate their molecular recognition and catalysis sites for the processing by enzymes. Capitalizing on this distinct feature, a chimeric leader peptide strategy was recently developed to produce RiPP hybrids (Burkhart et al., 2017). Specifically, the leader peptides for the binding of thiazoline-forming cyclodehydratase, thioether-formation AlbA involved in the biosynthesis of sactipeptide, and lanthipeptide dehydratases NisB/C and ProcM were fused to allow sequential interactions with multiple processing enzymes of different RiPP families (Figure 4). As such, the engineered core peptides were received a combination of chemical transformations to produce unnatural peptide products, providing a generally applicable strategy to unlock the vast chemical space afforded by a variety of RiPP biosynthetic machinery (Burkhart et al., 2017).

Figure 4. A chimeric leader peptide strategy to produce unnatural RiPP hybrids. By properly designing the concatenated leader peptides, recognition and processing by multiple enzymes from unrelated RiPP pathways could be realized. By using this method, a thiazoline-forming cyclodehydratase was combined with biosynthetic enzymes from the sactipeptide and lanthipeptide families to create new-to-nature hybrid RiPPs, demonstrating the feasibility of the strategy.

Screening a wide array of fermentation conditions, e.g., temperature, pH, shaking speed, nutrient levels, and trace metals, has routinely been practiced for the optimal production of target products. For example, Knappe et al. heterologously expressed the gene cluster of lasso peptide capistruin in E. coli and achieved a yield of 0.2 mg/L in the defined medium M20, which was 30% of its native producer Burkholderia thailandensis E264 in the same medium (Table 1) (Knappe et al., 2008). Surprisingly, no capistruin was produced when culturing transformed E. coli in commonly used LB medium. In another example, after testing a variety of conditions, the co-expression of Fe-S cluster biogenesis genes and lowered shaking speed together led to the significantly improved expression of subtilosin A in E. coli (Himes et al., 2016).

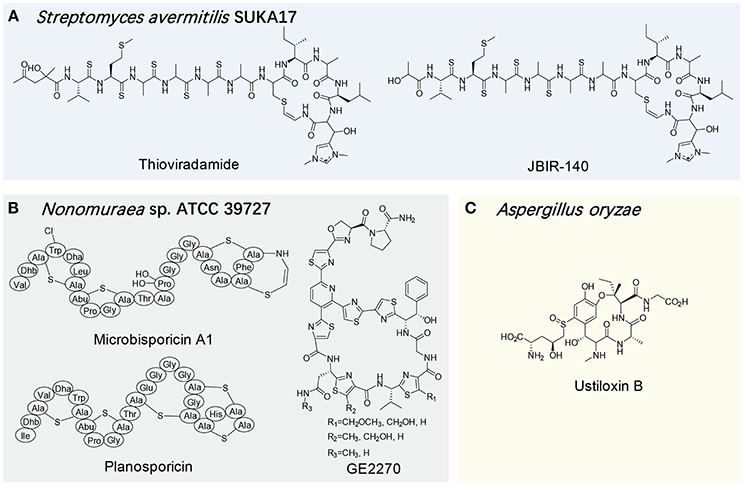

An ideal host for the heterologous expression of natural products usually requires a clean background and high compatibility with the target biosynthetic gene cluster. More specifically, the ideal heterologous host would be able to supply abundant biosynthetic precursors from its primary metabolism while maintaining a relative clean secondary metabolic background, and also be capable of recognizing exogenous genetic parts, thus allowing access to the vast biosynthetic potential of the host. In this regard, E. coli has become one of the most popular heterologous hosts, and produced many RiPP families, e.g., cyanobactins, lantipeptides, lasso peptides, microviridins, and sactipeptides (Donia et al., 2006; Weiz et al., 2011; Metelev et al., 2013; Himes et al., 2016; Kuthning et al., 2016). On the other hand, the RiPP gene cluster from a high G+C producer is often expressed in a host with a relatively comparable genetic background. For example, the lantibiotic cinnamycin is produced by several Streptomyces strains and its gene cluster from S. cinnamoneus cinnamoneus DSM 40005 was successfully expressed in S. lividans to produce this peptidic antibiotic (Widdick et al., 2003). In another study, S. lividans TK23 and S. avermitilis SUKA17 were used as the hosts to produce thioviridamide (Table 1, Figure 5A; Izawa et al., 2013; Izumikawa et al., 2015). Interestingly, the expression of its gene cluster in S. avermitilis SUKA17 led to the production of a novel thioviridamide derivative, JBIR-140, further demonstrating the significant influence of a surrogate host on RiPP production.

Figure 5. Structures of select RiPPs produced by uncommon surrogate hosts exemplified by Streptomyces avermitilis SUKA17 (A), Nonomuraea sp. ATCC 39727 (B) and Aspergillus oryzae (C).

In addition to the widely used hosts like E. coli and Streptomyces strains, several uncommon microorganisms have also been characterized as suitable RiPP heterologous hosts. With the consideration of available substrates and comparable genetic backgrounds, these heterologous hosts are often from the same family of the native producers of the target RiPPs. For example, when expressing the clusters of the lantibiotics microbisporicin and planosporicin and the thiopeptide GE2270 from Microbispora coralline, Planomonospora alba and Planobispora rosea, respectively, Nonomuraea sp. ATCC 39727, which is in the same family of the above native producers, acted as a viable host to produce corresponding RiPPs, but not multiple other tested Streptomyces strains (Table 1, Figure 5B; Foulston and Bibb, 2010; Sherwood et al., 2013; Tocchetti et al., 2013).

In recent years, fungal RiPPs have attracted increasing attentions given the availability of a number of fungal genomes in public domain (Hallen et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2016; Nagano et al., 2016; Ramm et al., 2017). To realize the chemical and functional potential of fungal RiPPs, their heterologous expression systems have to be established. In this regard, commonly used fungal strains can be initial targets in the development. Encouragingly, several biosynthetic genes of ustiloxin, the first filamentous fungal RiPP, were successfully expressed in Aspergillus oryzae, greatly facilitating the understanding of the macrocyclic formation and its entire biosynthetic pathway (Table 1, Figure 5C; Ye et al., 2016). In a more recent example, the partial reconstitution of the biosynthesis of one dodecapeptide omphalotin A, which is ribosomally produced by the basidiomycete Omphalotus olearius, was succeeded in Pichia pastoris strain GS115, but not E. coli (Ramm et al., 2017). This work further shed light on a novel biosynthesis mechanism for a RiPP in which a self-sacrificing enzyme, methyltransferase OphMA, bears its own precursor peptide.

Cyclotides are a family of plant-derived RiPPs that are characterized by a head-to-tail cyclic peptide backbone and a cystine knot arrangement of disulfide bonds. These peptidic compounds possess a wide range of bioactivities (e.g., protease inhibition, anti-microbials, and cytotoxicity) and are good carriers of other bioactive peptides, both of which are attractive to pharmaceutical research. Recently, the heterologous production of cyclotides were successfully achieved by co-expressing a select asparaginyl endoprotease and its precursor peptide in planta, using Nicotiana benthamian, tobacco, bush bean, lettuce, and canola as hosts (Poon et al., 2018). Interestingly, alternative strategies such as intein-mediated protein trans-splicing (Jagadish et al., 2013) and sortase-induced backbone cyclization (Stanger et al., 2014) have also been developed to produce cyclotides in bacterial and yeast expression systems, in which the asparaginyl endoprotease is not employed for the cyclization.

Harnessing the biosynthetic prowess of RiPPs via heterologous expression has witnessed several exciting advances in recent years. As described above, due to the conciseness of the biosynthetic route, the cloning and mobilization of the RiPP gene clusters typically do not constitute a major hurdle for the heterologous production of RiPPs. However, the functional expression of biosynthetic genes in surrogate hosts could be complicated by many less-predictable factors, such as the availability of protein cofactors, promoter recognition, product toxicity, protein–protein interaction, and imbalanced protein dosage. On the other hand, with E. coli and Streptomyces strains serving as the most common hosts in the heterologous expression of RiPPs, the ever-increasing number of synthetic biology tools developed for these systems can be applied to overcome these challenges. In addition, in vitro characterization of RiPP biosynthesis and in silico prediction can be coupled to streamline and improve the outcomes of heterologous expression efforts. We are optimistic that a small set of highly developed hosts will be available as generally applicable platforms for rapid and robust sampling of the vast chemical space of RiPPs from bacteria, fungi, and even plants in future.

YZ, MC, SB, and YD planned, wrote and reviewed the manuscript.

This work was partly supported by America Cancer Society Institutional Research Grant (YD), the Department of Medicinal Chemistry at the University of Florida and NIH NIGMS (1R35GM128742).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We would like to thank lab members of the Ding and Bruner groups for many discussions of this topic. We also thank Prof. Hendrik Luesch for informative suggestions. Due to length limitations, here we were unable to include many other excellent studies in the heterologous production of RiPPs. We apologize to the authors whose studies were not cited.

Abdelmohsen, U. R., Grkovic, T., Balasubramanian, S., Kamel, M. S., Quinn, R. J., and Hentschel, U. (2015). Elicitation of secondary metabolism in actinomycetes. Biotechnol. Adv. 33, 798–811. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2015.06.003

Almabruk, K. H., Dinh, L. K., and Philmus, B. (2018). Self-resistance of natural product producers: past, present, and future focusing on self-resistant protein variants. ACS Chem. Biol. 13, 1426–1437. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.8b00173

Amagai, K., Ikeda, H., Hashimoto, J., Kozone, I., Izumikawa, M., Kudo, F., et al. (2017). Identification of a gene cluster for telomestatin biosynthesis and heterologous expression using a specific promoter in a clean host. Sci. Rep. 7:3382. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-03308-5

Arnison, P. G., Bibb, M. J., Bierbaum, G., Bowers, A. A., Bugni, T. S., Bulaj, G., et al. (2013). Ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products: overview and recommendations for a universal nomenclature. Nat. Prod. Rep. 30, 1568–1568. doi: 10.1039/C2NP20085F

Aso, Y., Nagao, J., Koga, H., Okuda, K., Kanemasa, Y., Sashihara, T., et al. (2004). Heterologous expression and functional analysis of the gene cluster for the biosynthesis of and immunity to the lantibiotic, nukacin ISK-1. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 98, 429–436. doi: 10.1016/S1389-1723(05)00308-7

Bai, C., Zhang, Y., Zhao, X., Hu, Y., Xiang, S., Miao, J., et al. (2015). Exploiting a precise design of universal synthetic modular regulatory elements to unlock the microbial natural products in Streptomyces. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 112, 12181–12186. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1511027112

Bartholomae, M., Buivydas, A., Viel, J. H., Montalbán-López, M., and Kuipers, O. P. (2017). Major gene-regulatory mechanisms operating in ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide (RiPP) biosynthesis. Mol. Microbiol. 106, 186–206. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13764

Basi-Chipalu, S., Dischinger, J., Josten, M., Szekat, C., Zweynert, A., Sahl, H. G., et al. (2015). Pseudomycoicidin, a class II lantibiotic from Bacillus pseudomycoides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 81, 3419–3429. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00299-15

Behie, S. W., Bonet, B., Zacharia, V. M., McClung, D. J., and Traxler, M. F. (2017). Molecules to ecosystems: Actinomycete natural products in situ. Front. Microbiol. 7:2149. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.02149

Bindman, N. A., Bobeica, S. C., Liu, W. S. R., and Van Der Donk, W. A. (2015). Facile removal of leader peptides from lanthipeptides by incorporation of a hydroxy acid. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 137, 6975–6978. doi: 10.1021/jacs.5b04681

Burkhart, B. J., Kakkar, N., Hudson, G. A., Van Der Donk, W. A., and Mitchell, D. A. (2017). Chimeric leader peptides for the generation of non-natural hybrid RiPP products. ACS Cent. Sci. 3, 629–638. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00141

Caetano, T., Krawczyk, J. M., Mösker, E., Süssmuth, R. D., and Mendo, S. (2011a). Heterologous expression, biosynthesis, and mutagenesis of type II lantibiotics from Bacillus licheniformis in Escherichia coli. Chem. Biol. 18, 90–100. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2010.11.010

Caetano, T., Krawczyk, J. M., Mosker, E., Sussmuth, R. D., and Mendo, S. (2011b). Lichenicidin biosynthesis in Escherichia coli: licFGEHI immunity genes are not essential for lantibiotic production or self-protection. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 5023–5026. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00270-11

Cheigh, C. I., and Pyun, Y. R. (2005). Nisin biosynthesis and its properties. Biotechnol. Lett. 27, 1641–1648. doi: 10.1007/s10529-005-2721-x

Chekan, J. R., Koos, J. D., Zong, C. H., Maksimov, M. O., Link, A. J., and Nair, S. K. (2016). Structure of the lasso peptide isopeptidase identifies a topology for processing threaded substrates. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 138, 16452–16458. doi: 10.1021/jacs.6b10389

Chiang, Y. M., Chang, S. L., Oakley, B. R., and Wang, C. C. C. (2011). Recent advances in awakening silent biosynthetic gene clusters and linking orphan clusters to natural products in microorganisms. Curr. Opin. Chem. Biol. 15, 137–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2010.10.011

Claesen, J., and Bibb, M. J. (2011). Biosynthesis and regulation of grisemycin, a new member of the linaridin family of ribosomally synthesized peptides produced by Streptomyces griseus IFO 13350. J. Bacteriol. 193, 2510–2516. doi: 10.1128/JB.00171-11

Deane, C. D., Melby, J. O., Molohon, K. J., Susarrey, A. R., and Mitchell, D. A. (2013). Engineering unnatural variants of plantazolicin through codon reprogramming. ACS Chem. Biol. 8, 1998–2008. doi: 10.1021/cb4003392

De Mey, M., Maertens, J., Lequeux, G. J., Soetaert, W. K., and Vandamme, E. J. (2007). Construction and model-based analysis of a promoter library for E. coli: an indispensable tool for metabolic engineering. BMC Biotechnol. 7:34. doi: 10.1186/1472-6750-7-34

Deng, T., Ge, H., He, H., Liu, Y., Zhai, C., Feng, L., et al. (2017). The heterologous expression strategies of antimicrobial peptides in microbial systems. Protein Expr. Purif. 140, 52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2017.08.003

Ding, W., Liu, W. Q., Jia, Y. L., Li, Y. Z., Van Der Donk, W. A., and Zhang, Q. (2016). Biosynthetic investigation of phomopsins reveals a widespread pathway for ribosomal natural products in Ascomycetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 3521–3526. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1522907113

Donia, M. S., Hathaway, B. J., Sudek, S., Haygood, M. G., Rosovitz, M. J., Ravel, J., et al. (2006). Natural combinatorial peptide libraries in cyanobacterial symbionts of marine ascidians. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2, 729–735. doi: 10.1038/nchembio829

Donia, M. S., Ravel, J., and Schmidt, E. W. (2008). A global assembly line for cyanobactins. Nat. Chem. Biol. 4, 341–343. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.84

Flinspach, K., Kapitzke, C., Tocchetti, A., Sosio, M., and Apel, A. K. (2014). Heterologous expression of the thiopeptide antibiotic GE2270 from Planobispora rosea ATCC 53733 in Streptomyces coelicolor requires deletion of ribosomal genes from the expression construct. PLoS ONE 9:e90499. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0090499

Foulston, L. C., and Bibb, M. J. (2010). Microbisporicin gene cluster reveals unusual features of lantibiotic biosynthesis in actinomycetes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 107, 13461–13466. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1008285107

Garg, N., Tang, W. X., Goto, Y., Nair, S. K., and Van Der Donk, W. A. (2012). Lantibiotics from Geobacillus thermodenitrificans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 5241–5246. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1116815109

Hallen, H. E., Luo, H., Scott-Craig, J. S., and Walton, J. D. (2007). Gene family encoding the major toxins of lethal Amanita mushrooms. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 104, 19097–19101. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0707340104

Hayashi, S., Ozaki, T., Asamizu, S., Ikeda, H., Omura, S., Oku, N., et al. (2014). Genome mining reveals a minimum gene set for the biosynthesis of 32-membered macrocyclic thiopeptides lactazoles. Chem. Biol. 21, 679–688. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2014.03.008

Hegemann, J. D., Zimmermann, M., Xie, X., and Marahiel, M. A. (2013a). Caulosegnins I-III: A highly diverse group of lasso peptides derived from a single biosynthetic gene cluster. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 210–222. doi: 10.1021/ja308173b

Hegemann, J. D., Zimmermann, M., Zhu, S. Z., Klug, D., and Marahiel, M. A. (2013b). Lasso peptides from proteobacteria: Genome mining employing heterologous expression and mass spectrometry. Biopolymers 100, 527–542. doi: 10.1002/bip.22326

Hetrick, K. J., Walker, M. C., and Van Der Donk, W. A. (2018). Development and application of yeast and phage display of diverse lanthipeptides. ACS Cent. Sci. 4, 458–467. doi: 10.1021/acscentsci.7b00581

Himes, P. M., Allen, S. E., Hwang, S. W., and Bowers, A. A. (2016). Production of sactipeptides in Escherichia coli: probing the substrate promiscuity of subtilosin A biosynthesis. ACS Chem. Biol. 11, 1737–1744. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.6b00042

Huo, L., Rachid, S., Stadler, M., Wenzel, S. C., and Müller, R. (2012). Synthetic biotechnology to study and engineer ribosomal bottromycin biosynthesis. Chem. Biol. 19, 1278–1287. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.08.013

Iftime, D., Jasyk, M., Kulik, A., Imhoff, J. F., Stegmann, E., Wohlleben, W., et al. (2015). Streptocollin, a Type IV lanthipeptide produced by Streptomyces collinus Tu 365. Chembiochem 16, 2615–2623. doi: 10.1002/cbic.201500377

Izawa, M., Kawasaki, T., and Hayakawa, Y. (2013). Cloning and heterologous expression of the thioviridamide biosynthesis gene cluster from Streptomyces olivoviridis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 79, 7110–7113. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01978-13

Izumikawa, M., Kozone, I., Hashimoto, J., Kagaya, N., Takagi, M., Koiwai, H., et al. (2015). Novel thioviridamide derivative-JBIR-140: heterologous expression of the gene cluster for thioviridamide biosynthesis. J. Antibiot. 68, 533–536. doi: 10.1038/ja.2015.20

Jagadish, K., Borra, R., Lacey, V., Majumder, S., Shekhtman, A., Wang, L., et al. (2013). Expression of fluorescent cyclotides using protein trans-splicing for easy monitoring of cyclotide–protein interactions. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 52, 3126–3131. doi: 10.1002/anie.201209219

Jia, B., Raphenya, A. R., Alcock, B., Waglechner, N., Guo, P. Y., Tsang, K. K., et al. (2017). CARD 2017: expansion and model-centric curation of the comprehensive antibiotic resistance database. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, D566–D573. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw1004

Jiménez, J. J., Diep, D. B., Borrero, J., Gútiez, L., Arbulu, S., Nes, I. F., et al. (2015). Cloning strategies for heterologous expression of the bacteriocin enterocin A by Lactobacillus sakei Lb790, Lb. plantarum NC8 and Lb. casei CECT475. Microb. Cell Fact. 14:116. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0346-x

Khaldi, N., Seifuddin, F. T., Turner, G., Haft, D., Nierman, W. C., Wolfe, K. H., et al. (2010). SMURF: Genomic mapping of fungal secondary metabolite clusters. Fungal Genet. Biol. 47, 736–741. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2010.06.003

Knappe, T., Linne, U., Zirah, S., Rebuffat, S., Xie, X. L., and Marahiel, M. (2008). Isolation and structural characterization of capistruin, a lasso peptide predicted from the genome sequence of Burkholderia thailandensis E264. J. Pept. Sci. 14, 97–97. doi: 10.1021/ja802966g

Komatsu, M., Komatsu, K., Koiwai, H., Yamada, Y., Kozone, I., Izumikawa, M., et al. (2013). Engineered Streptomyces avermitilis host for heterologous expression of biosynthetic gene cluster for secondary metabolites. ACS Synth. Biol. 2, 384–396. doi: 10.1021/sb3001003

Kuthning, A., Durkin, P., Oehm, S., Hoesl, M. G., Budisa, N., and Süssmuth, R. D. (2016). Towards biocontained cell factories: An evolutionarily adapted Escherichia coli strain produces a new-to-nature bioactive lantibiotic containing thienopyrrole-alanine. Sci. Rep. 6:33447. doi: 10.1038/srep33447

Kuthning, A., Mösker, E., and Süssmuth, R. D. (2015). Engineering the heterologous expression of lanthipeptides in Escherichia coli by multigene assembly. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 99, 6351–6361. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6557-6

Leikoski, N., Fewer, D. P., Jokela, J., Wahlsten, M., Rouhiainen, L., and Sivonen, K. (2010). Highly diverse cyanobactins in strains of the genus Anabaena. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 76, 701–709. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01061-09

Li, S., Wang, J., Li, X., Yin, S. L., Wang, W. S., and Yang, K. Q. (2015). Genome-wide identification and evaluation of constitutive promoters in streptomycetes. Microb. Cell Fact. 14:172. doi: 10.1186/s12934-015-0351-0.

Lohans, C. T., Li, J. L., and Vederas, J. C. (2014). Structure and biosynthesis of carnolysin, a homologue of Enterococcal cytolysin with D-amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 136, 13150–13153. doi: 10.1021/ja5070813

Long, P. F., Dunlap, W. C., Battershill, C. N., and Jaspars, M. (2005). Shotgun cloning and heterologous expression of the patellamide gene cluster as a strategy to achieving sustained metabolite production. Chembiochem 6, 1760–1765. doi: 10.1002/cbic.200500210

Lopatniuk, M., Myronovskyi, M., and Luzhetskyy, A. (2017). Streptomyces albus: a new cell factory for non-canonical amino acids incorporation into ribosomally synthesized natural products. ACS Chem. Biol. 12, 2362–2370. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.7b00359

Luo, Y., Cobb, R. E., and Zhao, H. M. (2014). Recent advances in natural product discovery. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 30, 230–237. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2014.09.002

Maksimov, M. O., and Link, A. J. (2013). Discovery and characterization of an isopeptidase that linearizes lasso peptides. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 135, 12038–12047. doi: 10.1021/ja4054256

Maksimov, M. O., Pelczer, I., and Link, A. J. (2012). Precursor-centric genome-mining approach for lasso peptide discovery. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, 15223–15228. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1208978109

Malcolmson, S. J., Young, T. S., Ruby, J. G., Skewes-Cox, P., and Walsh, C. T. (2013). The posttranslational modification cascade to the thiopeptide berninamycin generates linear forms and altered macrocyclic scaffolds. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 8483–8488. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1307111110

Mcintosh, J. A., Donia, M. S., Nair, S. K., and Schmidt, E. W. (2011). Enzymatic basis of ribosomal peptide prenylation in cyanobacteria. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13698–13705. doi: 10.1021/ja205458h

Metelev, M., Serebryakova, M., Ghilarov, D., Zhao, Y. F., and Severinov, K. (2013). Structure of microcin B-like compounds produced by Pseudomonas syringae and species specificity of their antibacterial action. J. Bacteriol. 195, 4129–4137. doi: 10.1128/JB.00665-13

Myronovskyi, M., and Luzhetskyy, A. (2016). Native and engineered promoters in natural product discovery. Nat. Prod. Rep. 33, 1006–1019. doi: 10.1039/C6NP00002A

Nagano, N., Umemura, M., Izumikawa, M., Kawano, J., Ishii, T., Kikuchi, M., et al. (2016). Class of cyclic ribosomal peptide synthetic genes in filamentous fungi. Fungal Genet. Biol. 86, 58–70. doi: 10.1016/j.fgb.2015.12.010

Nagao, J., Harada, Y., Shloya, K., Aso, Y., Zendo, T., Nakayama, H., et al. (2005). Lanthionine introduction into nukacin ISK-1 prepeptide by co-expression. with modification enzyme NAM in Escherichia coli. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 336, 507–513. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2005.08.125

Ökesli, A., Cooper, L. E., Fogle, E. J., and Van Der Donk, W. A. (2011). Nine post-translational modifications during the biosynthesis of cinnamycin. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 13753-13760. doi: 10.1021/ja205783f

Oldach, F., Al Toma, R., Kuthning, A., Caetano, T., Mendo, S., Budisa, N., et al. (2012). Congeneric lantibiotics from ribosomal in vivo peptide synthesis with noncanonical amino acids. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 51, 415–418. doi: 10.1002/anie.201106154

Omotajo, D., Tate, T., Cho, H., and Choudhary, M. (2015). Distribution and diversity of ribosome binding sites in prokaryotic genomes. BMC Genomics 16:604. doi: 10.1186/s12864-015-1808-6

Ortega, M. A., Hao, Y., Walker, M. C., Donadio, S., Sosio, M., Nair, S. K., et al. (2016). Structure and tRNA specificity of MibB, a lantibiotic dehydratase from Actinobacteria involved in NAI-107 biosynthesis. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 370–380. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.017

Ortega, M. A., and van Der Donk, W. A. (2016). New insights into the biosynthetic logic of ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide natural products. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 31–44. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.012

Pan, S. J., and Link, A. J. (2011). Sequence diversity in the lasso peptide framework: discovery of functional microcin J25 variants with multiple amino acid substitutions. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 5016–5023. doi: 10.1021/ja1109634

Pan, S. J., Rajniak, J., Maksimov, M. O., and Link, A. J. (2012). The role of a conserved threonine residue in the leader peptide of lasso peptide precursors. Chem. Commun. 48, 1880–1882. doi: 10.1039/c2cc17211a

Piscotta, F. J., Tharp, J. M., Liu, W. R., and Link, A. J. (2015). Expanding the chemical diversity of lasso peptide MccJ25 with genetically encoded noncanonical amino acids. Chem. Commun. 51, 409–412. doi: 10.1039/C4CC07778D

Poon, S., Harris, K. S., Jackson, M. A., Mccorkelle, O. C., Gilding, E. K., Durek, T., et al. (2018). Co-expression of a cyclizing asparaginyl endopeptidase enables efficient production of cyclic peptides in planta. J. Exp. Bot. 69, 633–641. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erx422

Ramm, S., Krawczyk, B., Mühlenweg, A., Poch, A., Mösker, E., and Sussmuth, R. D. (2017). A self-sacrificing N-methyltransferase is the precursor of the fungal natural product omphalotin. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 56, 9994–9997. doi: 10.1002/anie.201703488

Reen, F. J., Romano, S., Dobson, A. D., and O'Gara, F. (2015). The sound of silence: activating silent biosynthetic gene clusters in marine microorganisms. Mar. Drugs 13, 4754–4783. doi: 10.3390/md13084754

Ren, H., Wang, B., and Zhao, H. (2017). Breaking the silence: new strategies for discovering novel natural products. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 48, 21–27. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2017.02.008

Ruffner, D. E., Schmidt, E. W., and Heemstrat, J. R. (2015). Assessing the combinatorial potential of the RiPP cyanobactin tru pathway. ACS Synth. Biol. 4, 482–492. doi: 10.1021/sb500267d

Sardar, D., Pierce, E., Mcintosh, J. A., and Schmidt, E. W. (2015). Recognition sequences and substrate evolution in cyanobactin biosynthesis. ACS Synth. Biol. 4, 167–176. doi: 10.1021/sb500019b

Sashihara, T., Kimura, H., Higuchi, T., Adachi, A., Matsusaki, H., Sonomoto, K., et al. (2000). A novel lantibiotic, nukacin ISK-1, of Staphylococcus warneri ISK-1: cloning of the structural gene and identification of the structure. Biosci. Biotechno. Biochem. 64, 2420–2428. doi: 10.1271/bbb.64.2420

Schmidt, E. W., Nelson, J. T., Rasko, D. A., Sudek, S., Eisen, J. A., Haygood, M. G., et al. (2005). Patellamide, A., and C biosynthesis by a microcin-like pathway in Prochloron didemni, the cyanobacterial symbiont of Lissoclinum patella. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 7315–7320. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0501424102

Sherwood, E. J., Hesketh, A. R., and Bibb, M. J. (2013). Cloning and analysis of the planosporicin lantibiotic biosynthetic gene cluster of Planomonospora alba. J. Bacteriol. 195, 2309–2321. doi: 10.1128/JB.02291-12

Shi, Y., Yang, X., Garg, N., and Van Der Donk, W. A. (2011). Production of lantipeptides in Escherichia coli. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 2338–2341. doi: 10.1021/ja109044r

Skinnider, M. A., Merwin, N. J., Johnston, C. W., and Magarvey, N. A. (2017). PRISM 3: expanded prediction of natural product chemical structures from microbial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 45, W49–W54. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkx320

Smith, T. E., Pond, C. D., Pierce, E., Harmer, Z. P., Kwan, J., Zachariah, M. M., et al. (2018). Accessing chemical diversity from the uncultivated symbionts of small marine animals. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 179–185. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2537

Stanger, K., Maurer, T., Kaluarachchi, H., Coons, M., Franke, Y., and Hannoush Rami, N. (2014). Backbone cyclization of a recombinant cystine-knot peptide by engineered Sortase, A. FEBS Lett. 588, 4487–4496. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2014.10.020

Tang, W., and Van Der Donk, W. A. (2013). The sequence of the enterococcal cytolysin imparts unusual lanthionine stereochemistry. Nat. Chem. Biol. 9, 157–159. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.1162

Tang, W., and Van Der Donk, W. A. (2012). Structural characterization of four prochlorosins: a novel class of lantipeptides produced by planktonic marine cyanobacteria. Biochemistry 51, 4271–4279. doi: 10.1021/bi300255s

Tianero, M. D., Donia, M. S., Young, T. S., Schultz, P. G., and Schmidt, E. W. (2012). Ribosomal route to small-molecule diversity. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 134, 418–425. doi: 10.1021/ja208278k

Tianero, M. D., Pierce, E., Raghuraman, S., Sardar, D., Mcintosh, J. A., Heemstra, J. R., et al. (2016). Metabolic model for diversity-generating biosynthesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 113, 1772–1777. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1525438113

Tietz, J. I., Schwalen, C. J., Patel, P. S., Maxson, T., Blair, P. M., Tai, H.-C., et al. (2017). A new genome-mining tool redefines the lasso peptide biosynthetic landscape. Nat. Chem. Biol. 13, 470–478. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.2319

Tocchetti, A., Maffioli, S., Iorio, M., Alt, S., Mazzei, E., Brunati, C., et al. (2013). Capturing linear intermediates and C-terminal variants during maturation of the thiopeptide GE2270. Chem. Biol. 20, 1067–1077. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2013.07.005

Urban, J. H., Moosmeier, M. A., Aumüller, T., Thein, M., Bosma, T., Rink, R., et al. (2017). Phage display and selection of lanthipeptides on the carboxy-terminus of the gene-3 minor coat protein. Nat. Commu. 8:1500. doi: 10.1038/s41467-017-01413-7

Van Den Berg Van Saparoea, H. B., Bakkes, P. J., Moll, G. N., and Driessen, A. J. M. (2008). Distinct contributions of the nisin biosynthesis enzymes NisB and NisC and transporter NisT to prenisin production by Lactococcus lactis. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 74, 5541–5548. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00342-08

Van Heel, A. J., Mu, D., Montalbán-López, M., Hendriks, D., and Kuipers, O. P. (2013). Designing and producing modified, new-to-nature peptides with antimicrobial activity by use of a combination of various lantibiotic modification enzymes. ACS Synth. Biol. 2, 397–404. doi: 10.1021/sb3001084

Wang, J., Ma, H. C., Ge, X. X., Zhang, J., Teng, K. L., Sun, Z. Z., et al. (2014). Bovicin HJ50-like lantibiotics, a novel subgroup of lantibiotics featured by an indispensable disulfide bridge. PLoS ONE 9:e97121. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097121

Weber, T., Blin, K., Duddela, S., Krug, D., Kim, H. U., Bruccoleri, R., et al. (2015). antiSMASH 3.0-a comprehensive resource for the genome mining of biosynthetic gene clusters. Nucleic Acids Res. 43, W237–W243. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkv437

Weiz, A. R., Ishida, K., Makower, K., Ziemert, N., Hertweck, C., and Dittmann, E. (2011). Leader peptide and a membrane protein scaffold guide the biosynthesis of the tricyclic peptide microviridin. Chem. Biol. 18, 1413–1421. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2011.09.011

Widdick, D. A., Dodd, H. M., Barraille, P., White, J., Stein, T. H., Chater, K. F., et al. (2003). Cloning and engineering of the cinnamycin biosynthetic gene cluster from Streptomyces cinnamoneus cinnamoneus DSM 40005. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 100, 4316–4321. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0230516100

Yang, X., Lennard, K. R., He, C., Walker, M. C., Ball, A. T., Doigneaux, C., et al. (2018). A lanthipeptide library used to identify a protein-protein interaction inhibitor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 14, 375–380. doi: 10.1038/s41589-018-0008-5

Ye, Y., Minami, A., Igarashi, Y., Izumikawa, M., Umemura, M., Nagano, N., et al. (2016). Unveiling the biosynthetic pathway of the ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptide ustiloxin B in filamentous fungi. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. Engl. 55, 8072–8075. doi: 10.1002/anie.201602611

Young, T. S., Dorrestein, P. C., and Walsh, C. T. (2012). Codon randomization for rapid exploration of chemical space in thiopeptide antibiotic variants. Chem. Biol. 19, 1600–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2012.10.013

Young, T. S., and Schultz, P. G. (2010). Beyond the canonical 20 amino acids: Expanding the genetic lexicon. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 11039–11044. doi: 10.1074/jbc.R109.091306

Young, T. S., and Walsh, C. T. (2011). Identification of the thiazolyl peptide GE37468 gene cluster from Streptomyces ATCC 55365 and heterologous expression in Streptomyces lividans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 108, 13053–13058. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1110435108

Zambaldo, C., Luo, X. Z., Mehta, A. P., and Schultz, P. G. (2017). Recombinant macrocyclic lanthipeptides incorporating non-canonical amino acids. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 139, 11646–11649. doi: 10.1021/jacs.7b04159

Zhao, X., and Van Der Donk, W. A. (2016). Structural characterization and bioactivity analysis of the two-component lantibiotic Flv system from a ruminant bacterium. Cell Chem. Biol. 23, 246–256. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2015.11.014

Ziemert, N., Ishida, K., Liaimer, A., Hertweck, C., and Dittmann, E. (2008). Ribosomal synthesis of tricyclic depsipeptides in bloom-forming cyanobacteria. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 47, 7756–7759. doi: 10.1002/anie.200802730

Keywords: RiPPs, heterologous expression, precursor peptide, processing enzymes, synthetic biology, E. coli, Streptomyces

Citation: Zhang Y, Chen M, Bruner SD and Ding Y (2018) Heterologous Production of Microbial Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-translationally Modified Peptides. Front. Microbiol. 9:1801. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2018.01801

Received: 07 June 2018; Accepted: 17 July 2018;

Published: 07 August 2018.

Edited by:

Dipesh Dhakal, Sun Moon University, South KoreaReviewed by:

Johannes Koehbach, The University of Queensland, AustraliaCopyright © 2018 Zhang, Chen, Bruner and Ding. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yousong Ding, eWRpbmdAY29wLnVmbC5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.