94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Microbiol. , 19 December 2017

Sec. Plant Pathogen Interactions

Volume 8 - 2017 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02538

This article is part of the Research Topic Biotechnological potential of plant-microbe interactions in environmental decontamination View all 19 articles

Bao Chen1,2†

Bao Chen1,2† Sha Luo1†

Sha Luo1† Yingjie Wu1

Yingjie Wu1 Jiayuan Ye1

Jiayuan Ye1 Qiong Wang1

Qiong Wang1 Xiaomeng Xu1

Xiaomeng Xu1 Fengshan Pan1

Fengshan Pan1 Kiran Y. Khan1

Kiran Y. Khan1 Ying Feng1*

Ying Feng1* Xiaoe Yang1

Xiaoe Yang1Endophytic bacteria have received attention for their ability to promote plant growth and enhance phytoremediation, which may be attributed to their ability to produce indole-3-acetic acid (IAA). As a signal molecular, IAA plays a key role on the interaction of plant and its endomicrobes. However, the different effects that endophytic bacteria and IAA may have on plant growth and heavy metal uptake is not clear. In this study, the endophytic bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Sasm05 was isolated from the stem of the zinc (Zn)/cadmium (Cd) hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Hance. The effects of Sasm05 and exogenous IAA on plant growth, leaf chlorophyll concentration, leaf Mg2+-ATPase and Ca2+-ATPase activity, cadmium (Cd) uptake and accumulation as well as the expression of metal transporter genes were compared in a hydroponic experiment with 10 μM Cd. The results showed that after treatment with 1 μM IAA, the shoot biomass and chlorophyll concentration increased significantly, but the Cd uptake and accumulation by the plant was not obviously affected. Sasm05 inoculation dramatically increased plant biomass, Cd concentration, shoot chlorophyll concentration and enzyme activities, largely improved the relative expression of the three metal transporter families ZRT/IRT-like protein (ZIP), natural resistance associated macrophage protein (NRAMP) and heavy metal ATPase (HMA). Sasm05 stimulated the expression of the SaHMAs (SaHMA2, SaHMA3, and SaHMA4), which enhanced Cd root to shoot translocation, and upregulated SaZIP, especially SaIRT1, expression to increase Cd uptake. These results showed that although both exogenous IAA and Sasm05 inoculation can improve plant growth and photosynthesis, Sasm05 inoculation has a greater effect on Cd uptake and translocation, indicating that this endophytic bacterium might not only produce IAA to promote plant growth under Cd stress but also directly regulate the expression of putative key Cd uptake and transport genes to enhance Cd accumulation of plant.

Plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB) have recently attracted wide attention, because PGPB can effectively increase the plant biomass and the efficiency of heavy metal phytoextraction (Rajkumar et al., 2009; Glick, 2010, 2012, 2014; Bashan et al., 2013; Ma et al., 2016; Santoyo et al., 2016). Many studies have shown that the supplementary effects of PGPB on heavy metal phytoextraction were related to their capacity to promote plant growth, the production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA), 1-aminocyclopropane-1-carboxylic acid (ACC) deaminase, siderophores, antibiotics and phosphorus (P) solubilization (Penrose and Glick, 2003; Khalid et al., 2004; Hynes et al., 2008; Glick, 2010, 2012, 2014; Bashan et al., 2013). For instance, Pseudomonas azotoformans ASS1 could protect plants against abiotic stresses and help plants to thrive in semiarid ecosystems, accelerate the phytoremediation process in metal-polluted soils, and significantly enhance the chlorophyll content and improve the accumulation, bio-concentration factor and biological accumulation coefficient of metals (Ma et al., 2017).

As a phytohormone, IAA is known to be involved in root imitation, cell division and cell enlargement (Teale et al., 2006). It can not only found in plants but also reported to be synthesized in microorganisms (Kazan, 2013). The inoculation of IAA-producing endophytic bacteria has been demonstrated as a promising way to enhance plant biomass, root length, root tip number and root surface area (Chen et al., 2014a; Ali et al., 2017). The regulation of IAA secreted by PGPB and the plant is considered to be an important cause of growth promotion. For example, the bacterial endophyte Sphingomonas sp. LK11 isolated from the leaf of Tephrosia apollinea, which produces IAA (11.23 ± 0.93 μM mL-1) and gibberellins, promoted the growth of tomato (Khan et al., 2014). IAA produced by PGPB might play an extremely important role as a growth regulating substance that drives root hair and cotyledon cell expansion during seedling development (Strader et al., 2010). And even though the concentration of IAA production from various endophytic bacteria are different, IAA synthesis in both plant and microbe were affected by their interaction (Jasim et al., 2014). For instance, an average of 35 μg mL-1 IAA was produced in the five endophytic bacteria isolated from Piper nigrum, the yield of IAA was drastically increased around 20-fold to 869 μg mL-1 which can be due to the induction of the endophytic IAA biosynthetic pathway by the host plant metabolites (Jasim et al., 2014). Additionally, several reports showed that endophytes may also alter plant auxin synthesis (Kazan, 2013). And the cross-border regulation of microbes and their products on the plant IAA signal system is considered as the main mechanism that promotes lateral root development and relieves plant stress (Glick, 2012; Duca et al., 2014). Recent results indicated that IAA-overproducing endophytes had shown many transcriptional changes naturally occurring in nitrogen-fixing root nodule (Defez et al., 2016) and the high expression of nifH gene coding for the nitrogenase iron protein, moreover, they could increase nitrogenase activity of rice (Defez et al., 2017). Except for growth promoting, IAA can also affect plant heavy metal uptake and translocation. In Arabidopsis, exogenous auxin could enhance Cd2+ fixation in the root cell wall, decrease Cd2+ translocation from root to shoot thus to alleviate Cd toxicity (Zhu et al., 2013). Therefore, the IAA producing trait of endophytic bacteria may have multiple consequences in plant–microbe interaction.

Many studies have demonstrated that plants take up Cd primarily by the iron (Fe), zinc (Zn), manganese (Mn), and calcium (Ca) pathways in the roots (Clemens et al., 2013). IRT1 is metal ion transporter with a broad substrate range localized in the plasma membrane in Arabidopsis thaliana that can transport Fe, Zn, Mn, Cd, and cobalt (Co) (Korshunova et al., 1999). IRT1 is expressed in the plasma membrane of root epidermal cells (Vert, 2002) and is likely to be involved in Cd uptake. Other metal transporters of the ZRT-IRT-like Protein (ZIP) family (e.g., AtZIP1 and AtZIP2) have been indicated to play a role in Zn and Mn uptake (Milner et al., 2013). In Arabidopsis thaliana, P1B-type ATPases are known as Heavy Metal ATPase (HMA) and are the major transporters for root-to-shoot Cd translocation (Wong and Cobbett, 2009). In the HMA family, HvHMA2 is a plasma membrane P1B-ATPase from barley that functions in Zn/Cd root-to-shoot transport (Barabasz et al., 2013), AtHMA3 participates in the vacuolar storage of Cd (Morel et al., 2009), and AtHMA4 encodes the export protein responsible for loading Zn and Cd into the xylem vessels, thus controlling root to shoot translocation in Arabidopsis (Wong and Cobbett, 2009). We recently isolated and functionally characterized a tonoplast-localized SaHMA3 gene from Sedum alfredii Hance (S. alfredii), which had a significantly higher constitutive expression level. SaHMA3 is a Cd-specific transporter with the ability to transport both Cd and Zn (Zhang et al., 2016). Similar results were also obtained in S. plumbizincicola (Liu et al., 2017). In addition to ZIP and the HMA family, the Natural Resistance Associated Macrophage Protein (NRAMP) family play an important role in regulating metal ion transport (Sasaki et al., 2012). The plasma membrane-localized OsNramp5 is a major transporter for Cd uptake in rice (Ishimaru et al., 2012; Sasaki et al., 2012). AtNramp3 and AtNramp4 are located in vascular tissues and are both related to the mobilization of vacuolar Cd (Thomine et al., 2003; Lanquar et al., 2010). In Arabidopsis, Nramp1, 3, 4, and 6 were shown to confer Cd sensitivity in yeast (Thomine et al., 2000; Cailliatte et al., 2009).

Recent studies showed that PGPB could also regulate host plant gene expression. Defez et al. (2017) showed that the inoculation of IAA-overproducing endophytes could significantly up-regulate nitrogenase activity. Bacillus altitudinis WR10 could up-regulate the expression of many genes encoding ferritins, which alleviated iron deficiency in plants (Sun et al., 2017). Our results also showed that the inoculation of the IAA-producing endophytic bacteria SaMR12 can not only increase the leaf chlorophyll content as well as the iron and magnesium uptake but also regulate the expression of the three above mentioned heavy metal transporter genes in S. alferdii (Pan et al., 2017). However, few studies were compared the effects of PGPB and exogenous IAA on metal transporter gene expression.

S. alfredii is a native of China and a Zn/Cd hyperaccumulator. Based on the data from RNA-seq (Gao et al., 2013), we cloned a series of transporter genes (Zhang et al., 2016), but the mechanism of Cd hyperaccumulation in this plant is still not fully understood. Many endophytic bacteria have been isolated (Zhang et al., 2012) and they might also contribute to Cd hyperaccumulation in plants. In the present study, we investigated (1) the effects of the endophytic bacterium Sasm05 on plant growth and Cd uptake; (2) the effects of IAA and its transport inhibitor naphthylphthalamic acid (NPA) on plant growth and Cd uptake; and (3) the effects of Sasm05, IAA and NPA on the expression of selected transporter genes, to elucidate the functional contribution of IAA to plant–endophytic bacteria interactions.

The plant S. alfredii was collected from an old Pb/Zn mined site in Quzhou city, Zhejiang Province of China (Yang et al., 2004), and healthy and uniform shoots were selected and cultured hydroponically. After growth for 12 days in distilled water, the plants were subjected to 4 days exposure to one-half strength Hoagland nutrient solution, continuously aerated and renewed every 3 days. Plants were grown in an environmentally controlled growth chamber with a temperature range of 23–26°C, relative humidity 60% and light intensity of 180 μM m-2 s-1 during a 14/10 h day/night duration. Single shoot tips were excised and grown as described above for another generation to remove the heavy metals.

Healthy plants of S. alfredii together with soil were collected from six different points of the mined site, put into a sterile bag and sealed. After come back to the lab, the bacteria were isolated immediately and the other samples were stored at 4°C. The whole plant was washed with tap water for 30 min, and the roots, rotten leaves as well as diseased tissues were removed, and thus only the green healthy parts were preserved. Then the whole process was carried out in a super clean bench. First the plant tissue was washed with distilled water at least three times, 3 min each time. Later the washed tissue was immersed in 75% ethanol to maintain 3 min, sterile water washed 3 times, and then soaked in of 3% NaOCl (Cl- concentration) for 3 min, sterile water washed for five times. The obtained surface sterile tissues were placed on the sterilized filter paper, and the excess water was absorbed. The stems were sliced into thin slices and laid on the solid culture dish containing 20 mL Petri plates of Luria–Bertani’s (LB) medium. The sealed film was used to seal the culture dish and placed in 30°C for dark culture. In order to verify the effectiveness of the in vitro sterilization process, 200 μL washed water of the last time was evenly coated on the LB solid medium, and no colony growth treatment was used as effective surface sterilization. The colonies on the plant tissue were picked out with inoculation needle, purified in LB solid medium, and cultured at 30°C for 3 days, then the monoclonal strain was obtained (Supplementary Materials). A single colony was placed on a LB solid medium, 3 replicates per plant, cultured for 48 h and stored at 4°C for further analysis.

After purification and pathogenicity identification, single clone of candidate endophytic bacteria were selected and inoculated to 10 mL liquid LB medium, cultured at 37°C overnight. 1 mL bacteria suspension were put into a 1.5 mL centrifuge tube, 12000 rpm, 3 min. Then the precipitate were collected and washed by sterile water for two times. The genomic DNA was extracted with a rapid bacterial genomic DNA isolation kit (Sangon Biotech, China). Universal primers for bacteria were used for polymerase chain reaction (PCR) amplification; the forward primer was (27f: 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and the reverse primer was (1492r: 5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′). The amplified DNA was purified with a DNA purification kit (Sangon Biotech) and sequencing was performed at the Huada biotechnology company (Guangzhou, China). The 16S rDNA sequence was compared with sequences in the GenBank database using the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) Basic Local Alignment Search Tool - nucleotide (BLASTn) program1 (Weisburg et al., 1991). The strain was named Sasm05 and has been preserved in the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center with preservation number is CGMCC 12173 (Supplementary Materials).

The ability of bacteria to produce siderophore and ACC deaminase as well as heavy metal resistance were investigated according to Sheng et al. (2008). And IAA production and phosphate solubilizing enzyme were determined according to Tiwari et al. (2016).

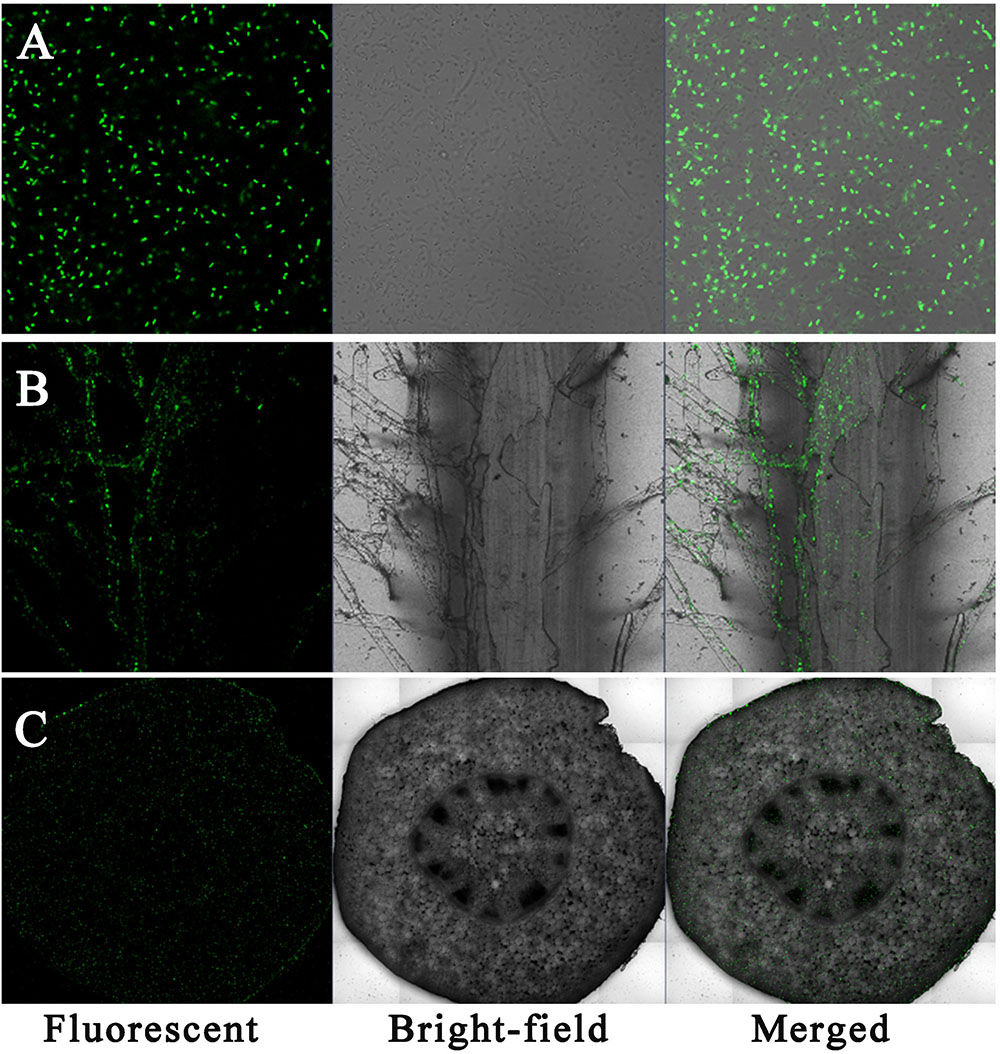

The green fluorescent protein (GFP) was used to label Sasm05 according to Zhang et al. (2013). Sasm05 was inoculated into 250 mL Erlenmeyer flasks containing 150 mL sterilized LB liquid medium and cultivated aerobically in an orbital rotary shaker (200 rpm) at 30°C for 24 h. The cells were collected by centrifugation, washed three times with 0.85% sterile saline, and resuspended to an OD = 1.0. Uniform plant seedlings were selected, and the roots were immersed in the labeled Sasm05 suspension for 2 h, then transferred to 10 μM Cd-containing Hoagland medium. The roots were imaged by Laser Scanning Confocal Microscopy (LSCM) 6 d after inoculation.

After 4 weeks of preculture, the roots of uniform young plants were immersed in each treatment for 4 h: (1) Control treatment (sterilized deionized water), (2) Sasm05 (107 CFU /mL), (3) Sasm05 and 10 μM IAA transport inhibitor (NPA), (4) 1 μM IAA, (5) 1 μM IAA and 10 μM NPA, and (6) 10 μM NPA, then exposed to 10 μM Cd Hoagland nutrient solution with (treatments 3, 5, and 6) or without NPA (treatments 1, 2, and 4). 4 plants were transferred into a 2.5 L black plastic bucket as one treatment, and each treatment was repeated six times.

The hydroponic plant cultures were harvested after 7 days for gene expression analysis or 30 days for Cd uptake analysis, and the shoots and roots were washed with deionized water. The fresh weights (FW) and the dry weights (DW) of the roots and shoots were recorded before and after oven-drying at 65°C for 48 h.

The plant roots were soaked in 20 mM Na2-EDTA for 15 min to remove the Cd ions adhering to the root surfaces. The shoots and roots were dried and powered as much as possible. A final sample of 0.1 g was digested by adding 5 mL HNO3 and 1 mL HClO4 in a boiled Polytetrachloroethylene cup at 180°C for 8 h. The digested samples were diluted with deionized water, filtered through a filter membrane (13 mm, 0.22 μm), and the Cd concentration was determined using an Inductively Coupled Plasma Mass Spectrometer (ICP-MS, Agilent 7500a, United States).

Acetone and ethyl alcohol were mixed in a ratio of 2:1, fresh leaf (without veins and stalks) samples (0.20 g each) were placed into this mixture (20 mL) in the dark for 24 h before the extracts were measured for the absorbance at wavelengths of 663 and 645 nm using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Lambda 350V-vis, PerkinElmer, Singapore) (Chen et al., 2014b). The Chl concentration (g kg-1) was calculated using the following equations: Total Chl = [8.02 × A663] + [20.21 × A645].

For Ca2+-ATPase, 3 mL of total reaction mixture containing 0.3 mL of crude mitochondrial extract, 30 mmol L-1 Tris-HCl buffer (pH 8.0), 3 mmol L-1 Mg2SO4, 0.1 mmol L-1 Na3VO4, 50 mmol L-1 NaNO3, 3 mmol L-1 Ca(NO3)2 and 0.1 mmol L-1 ammonium molybdate was employed. The reaction was initiated by the addition of 100 μL of 30 mmol L-1 trichloroacetic acid after 20 min of incubation at 37°C. One unit of Ca2+-ATPase activity was defined as the release of 1 mol of phosphorus in absorbance per minute at 660 nm under the assay conditions (Jin et al., 2013).

For Mg2+-ATPase, a reaction mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.8, 33% methanol, 4 mM ATP, 4 mM MgCl2 and thylakoids at 30 μg Chl/mL in total volume of 1.0 mL was employed. After incubation at 37°C for 2 min, the reaction was terminated by the addition of 0.1 ml of 20% TCA, then the release of Pi was determined (Ren et al., 1995).

Shoot and root tissues were collected after 7 days of treatment and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen prior to total RNA extraction. Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen). The first-strand cDNA was synthesized with a 10 μL reaction system according to the instructions for the TAKARA PrimeScript RT Reagent Kit (Perfect for Real Time) (TaKaRa Biotechnology, Dalian, China). For a real-time RT-PCR analysis, 1 μL 10-fold-diluted cDNA was used for the quantitative analysis of gene expression performed with SYBR PremixExTaq (Takara), and the pairs of gene-specific primers used were the same as in Pan et al. (2017). The expression data were normalized to the expression of actin (forward: 5′-TGTGCTTTCCCTCTATGCC-3′; reverse: 5′-CGCTCAGCAGTGGTTGTG-3′).

A Mastercycler ep realplex2 Real Time PCR machine (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with the default program (2 min at 50°C and 10 min at 95°C followed by 40 cycles at 95°C for 30 s, 55°C for 30 s, and 72°C for 30 s.) were employed for quantitative RT-PCR analysis with a reaction mixture volume of 20 μL in an optical 96-well plate. A control was also included in each plate with 2 μL of RNase-free water as a template. Three technical replicates were contained in each plate. Specificity verification of the PCR amplification dissociation and the PCR efficiency curves were determined for each candidate reference gene prior to the quantitative RT-PCR evaluation of these genes in S. alfredii. The relative quantification analysis was performed using the comparative ΔΔCt method and the formula was: Fold induction = 2-ΔΔCT, as described by Winer et al. (1999). To evaluate the gene expression level, the results were normalized using Ct values obtained from actin cDNA amplifications run on the same plate.

Three replicates were used and analyzed independently for each treatment. The data was analyzed using OriginPro 8, and it was analyzed statistically by a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA). Significantly different means were indicated by Fisher’s least significant difference (LSD) test and Duncan’s multiple range test at the P < 0.05 level.

Sasm05, an endophytic bacterium isolated from surface sterilized stems of S. alfredii, was identified as a gram-negative bacterium and a Pseudomonas fluorescens by 16S rRNA array. It could utilize tryptophane for growing and produce IAA (15–50 μg mL-1). It also could utilize ACC as the sole nitrogen source and show relatively high levels of ACC deaminase activity (Table 1).

Sasm05 was successfully tagged by GFP (Figure 1A). Laser scanning confocal microscopy (LSCM) showed that under 10 μM Cd treatment, gfp-tagged Sasm05 colonized the root surface (Figure 1B) and evenly distributed in the plant stem as shown by the cross-section profile of the stem (Figure 1C).

FIGURE 1. Colonization of gfp-tagged Sasm05 in plant. (A) gfp-tagged Sasm05 strains on root surface, (B) colonized in the roots and (C) colonized in the stems. LSCM images show bacterial GFP fluorescence in green. Bars = 25 μM.

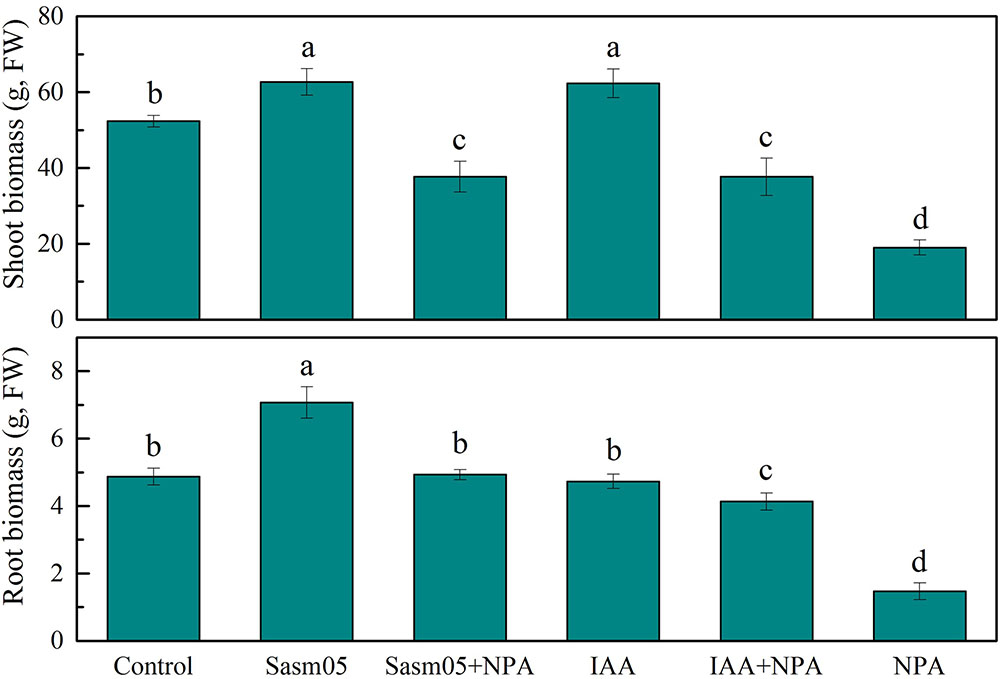

Plants were exposed to 10 μM Cd for 30 days and no visible phytotoxicity of Cd was observed. The shoot and root biomass (expressed as the fresh weight) were significantly (p < 0.05) enhanced by 20% and 45% by Sasm05 inoculation (Figure 2). IAA treatment could increase the shoot biomass by 19% but had no obvious effect on root biomass (Figure 2). However, the plant biomass was significantly inhibited by 64% and 70% (p < 0.05) in the 10 μM NPA treatment, and IAA or Sasm05 could alleviate this inhibition to some extent (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2. Effects of Sasm05 and IAA on the plant biomass. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) of three individual replicates. The different letters on the error bars indicate significant differences among the treatments at p < 0.05.

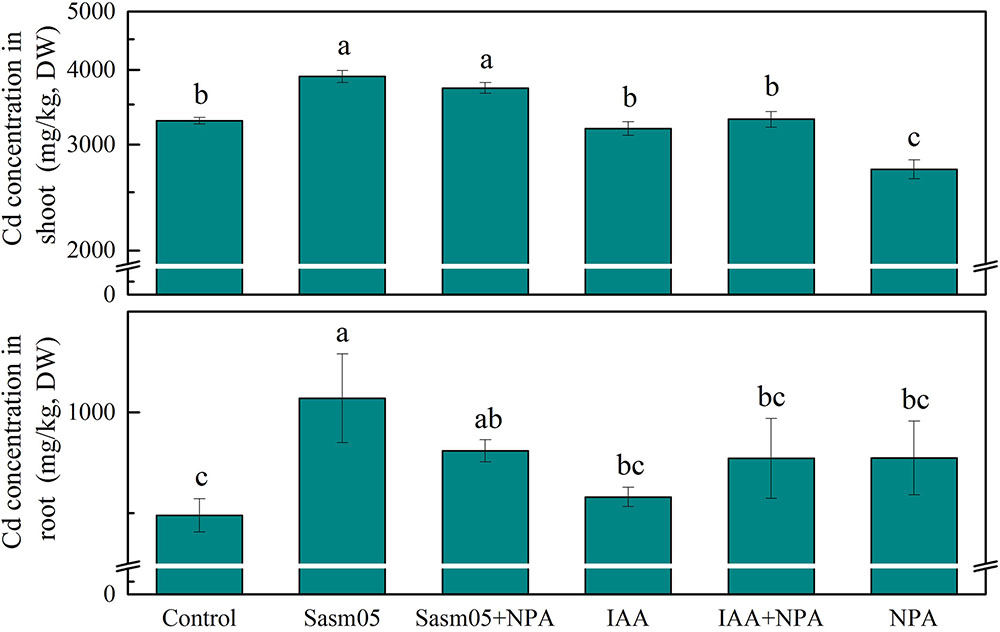

After inoculation with Sasm05, the Cd concentration in S. alfredii was significantly increased by 19% in the shoots and 59% in the roots, and even with an additional NPA treatment, the Cd concentration was still increased by 13% in the shoots and 37% in the roots (Figure 3). However, IAA treatment could not increase the Cd concentration compared to the control either whether NPA was added or not. In the NPA treatment, the Cd concentration was significantly decreased by 17% in the shoots and no changes were observed in the roots.

FIGURE 3. Effects of Sasm05 and IAA on Cd concentration. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) from of three individual replicates. The different letters on the error bars indicate significant differences among the treatments at p < 0.05.

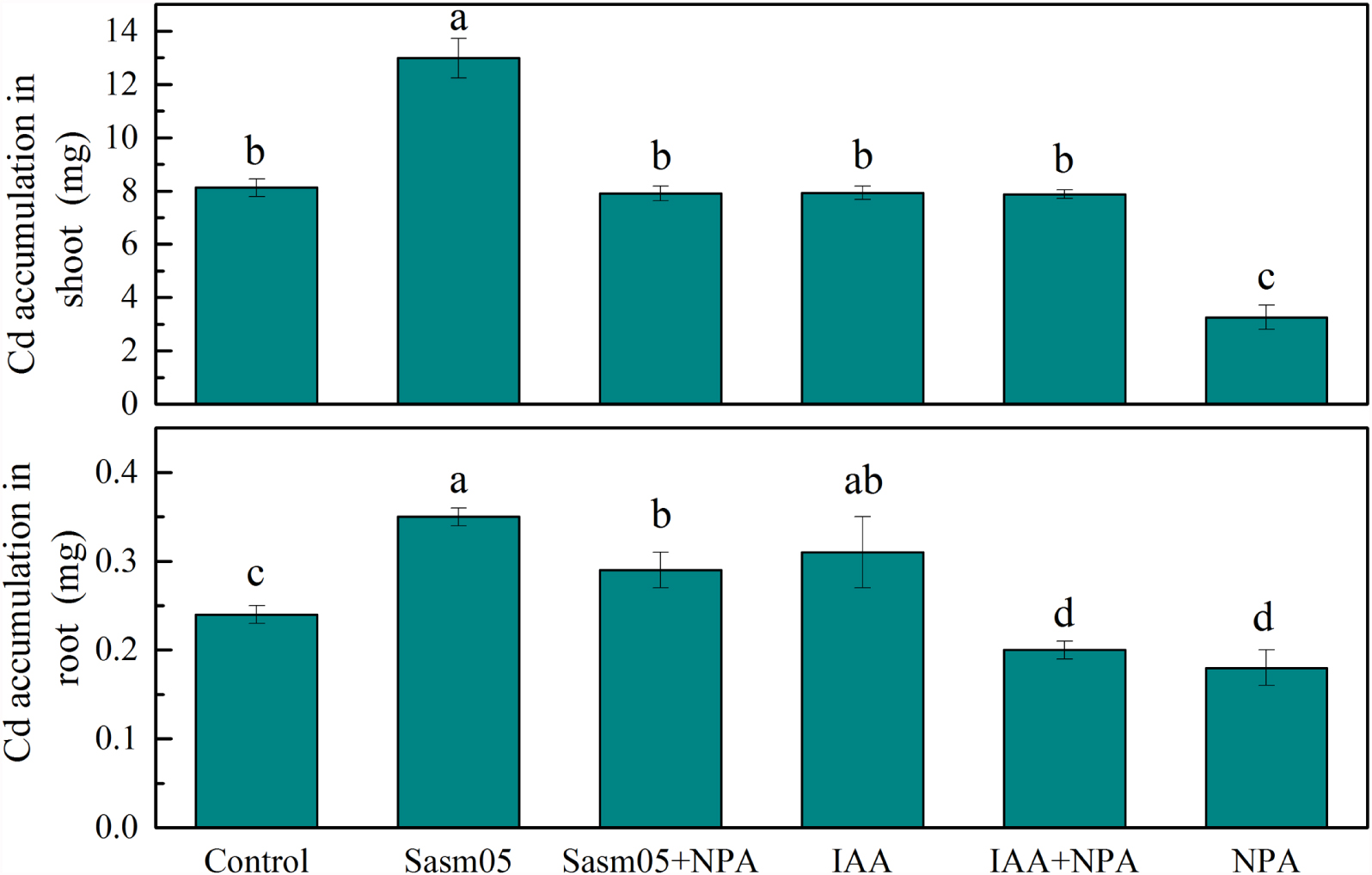

Cd accumulation in S. alfredii was significantly increased by 60% in the shoots and 46% in the roots with Sasm05 treatment (Figure 4). In the shoots, IAA or a combined NPA treatment showed no effect on the Cd accumulation, while it decreased by 60% when treated with NPA alone. In the roots, Sasm05 combined with NPA could increase Cd accumulation by 21%, while IAA combined with NPA or treated with NPA alone decreased the Cd accumulation by 17 and 25%, respectively.

FIGURE 4. Effects of Sasm05 and IAA on Cd accumulation. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) from of three individual replicates. The different letters on the error bars indicate significant differences among the treatments at p < 0.05.

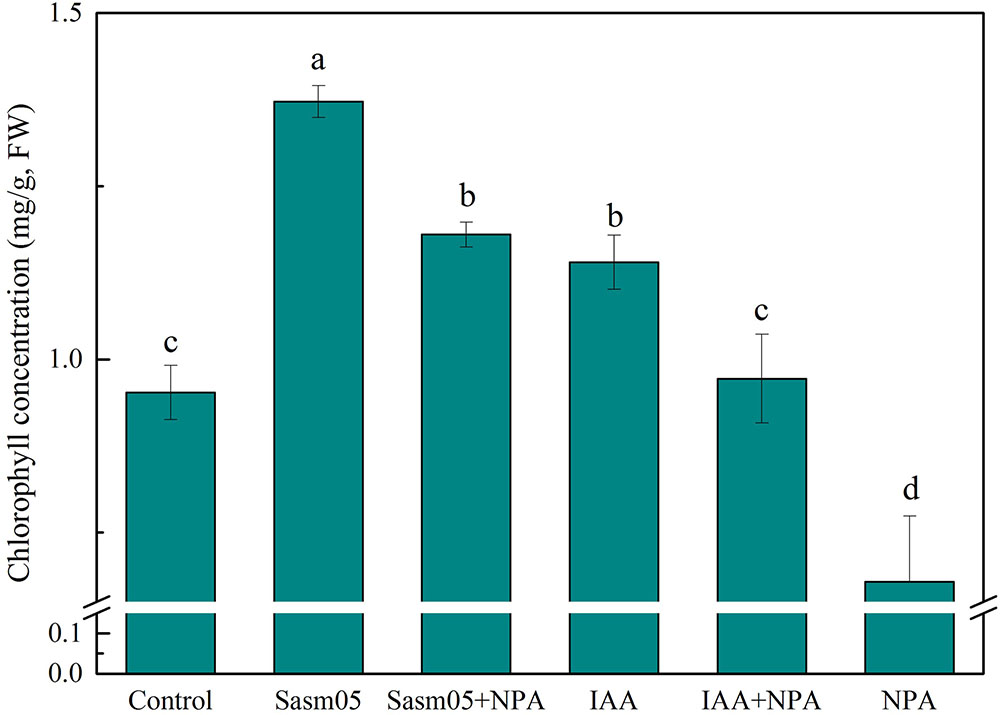

Both Sasm05 and IAA had a positive effect on the content of chlorophyll (P < 0.05), which was increased by 24–44 and 20% with Sasm05 and IAA treatments, respectively (Figure 5). Combined with NPA treatment, Sasm05 showed a higher chlorophyll concentration (18%) than when combined with an IAA treatment. Treatment with NPA alone resulted in a reduction of the chlorophyll concentration by 40%, indicating that NPA can inhibit the synthesis of chlorophyll (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5. Effects of Sasm05 and IAA on plant chlorophyll concentration. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) from of three individual replicates. The different letters on the error bars indicate significant differences among the treatments at p < 0.05.

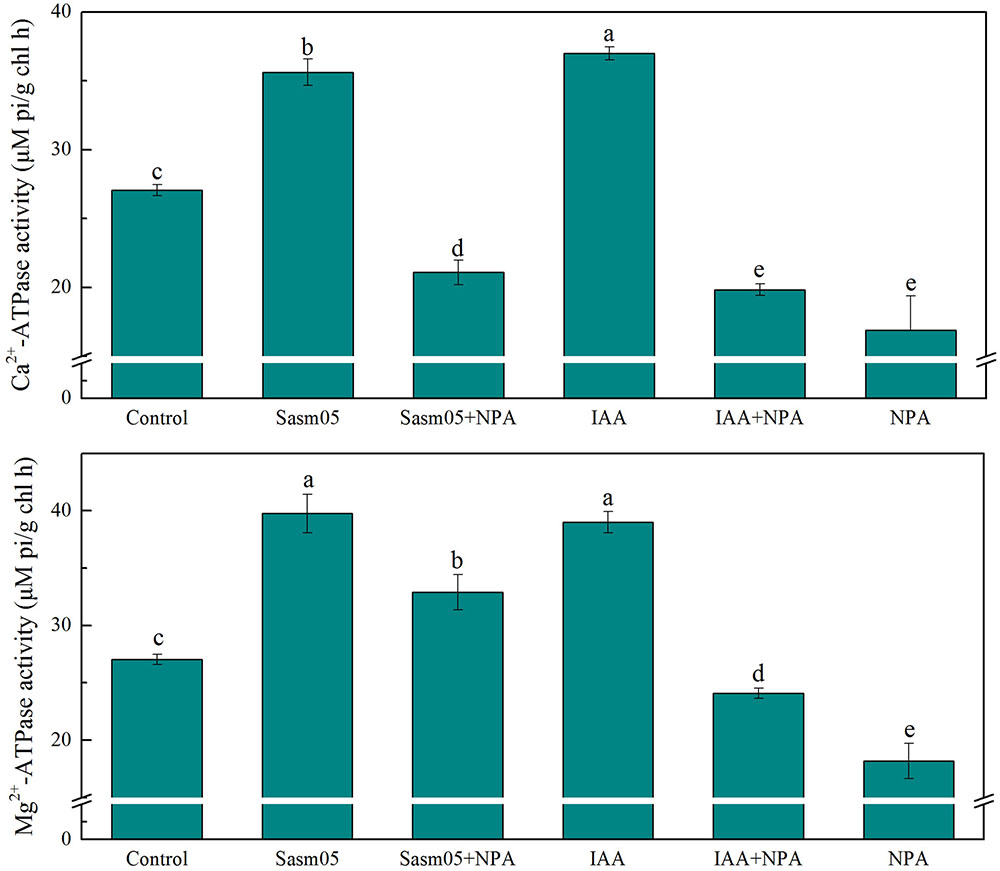

ATPases are the main transport proteins and energy source. Ca2+-ATPase was often affected by changes in the growth environment. In this experiment, both Sasm05 and IAA treatment could significantly increase the activity of Ca2+-ATPase by 32% and 37%, and IAA treatment was better than Sasm05 inoculation. All the NPA treated plants had lower Ca2+-ATPase levels than the control, which were decreased by 22% when combined with Sasm05, by 27% when combined with IAA, and by 38% when treated with NPA alone (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6. Effects of Sasm05 and IAA on leave Mg2+-ATPase activity and Ca2+-ATPase activity. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) from of three individual replicates. The different letters on the error bars indicate significant differences among the treatments at p < 0.05.

The Mg2+-ATPase activity was significantly enhanced by 47% and 22% in the Sasm05 and Sasm05 + NPA treatments, respectively (Figure 6). The biological activity of the Mg2+-ATPase was also enhanced by 46% by IAA, but it was significantly decreased by 33% in the IAA + NPA treatment (Figure 6).

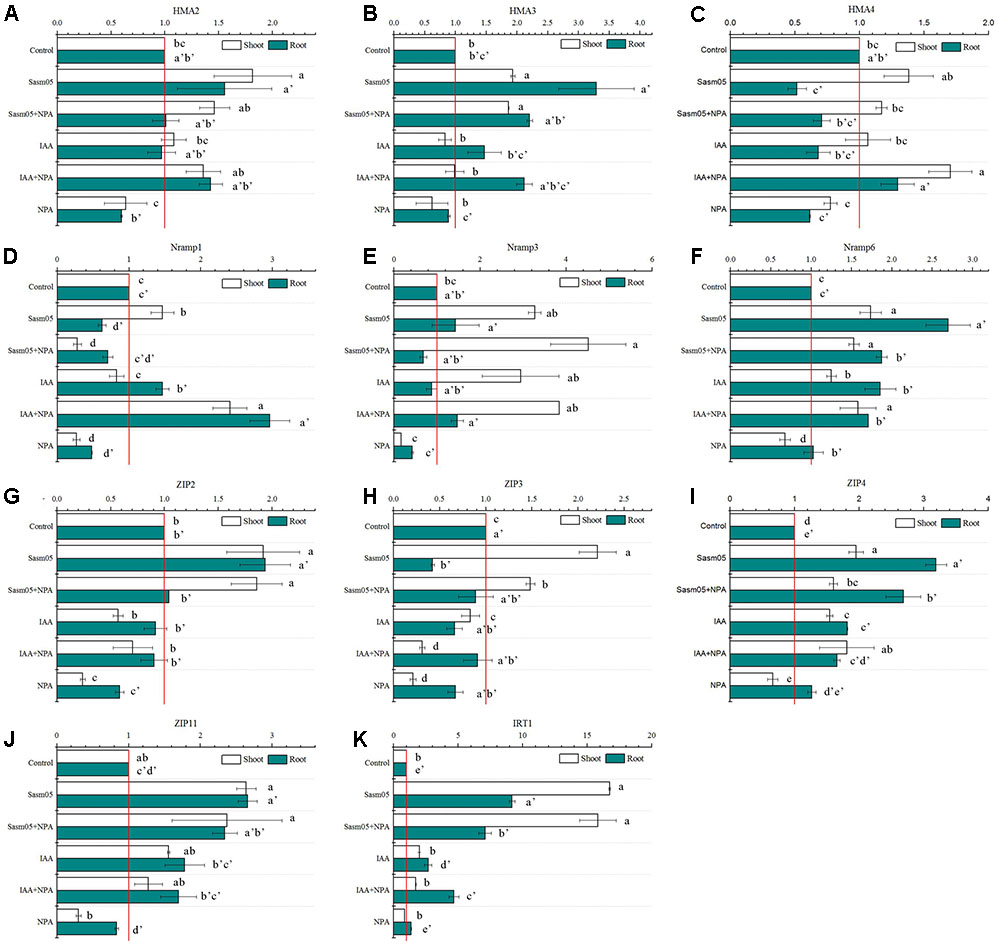

The quantitative RT-PCR results revealed that the transcripts of these metal transporter genes were highly induced by Sasm05, and the IRT1 transcript levels in the Sasm05 treatment in the shoots and the roots were 17-fold and 9-fold higher, respectively (Figure 7K). After inoculation with Sasm05, the expression of SaHMAs (SaHMA2, SaHMA3 and SaHMA4), SaNramps (SaNramp1, SaNramp3, SaNramp6), and SaZIPs (SaZIP2, SaZIP3, SaZIP4 and SaZIP11) in the shoots and SaHMAs (SaHMA2 and SaHMA3), SaNramps (SaNramp3 and SaNramp6), as well as SaZIPs (SaZIP2, SaZIP4 and SaZIP11) in the roots was significantly increased (Figures 7A–K). IAA treatment had no obvious effect on most genes, but it also increased the expression of SaNramp3, SaNramp6 and SaZIP4 in the shoots and SaNramps (SaNramp1, SaNramp6), SaZIPs (SaZIP4, SaZIP11 and SaIRT1) in the roots (Figures 7A–K). On the contrary, the expression levels of SaHMAs (SaHMA2 and SaHMA4), SaNramps (SaNramp1, SaNramp3 and SaNramp6), SaZIPs (SaZIP3, SaZIP4, and SaZIP11) in the shoots and SaHMAs (SaHMA2, SaHMA3 and SaHMA4), SaNramps (SaNramp1 and SaNramp3), SaZIPs (SaZIP2, SaZIP11, and SaIRT1) in the roots were reduced by the addition of NPA (Figures 7A–K). However, the addition of NPA and IAA increased the expression levels of SaHMAs (SaHMA2 and SaHMA4), SaNramps (SaNramp1, SaNramp3, and SaNramp6), SaZIP4 in the shoots and SaHMAs (SaHMA3 and SaHMA4), SaNramps (SaNramp1, SaNramp3 and SaNramp6), SaZIPs (SaZIP4, SaZIP11, SaIRT1) in the roots (Figures 7A–K).

FIGURE 7. Effects of Sasm05 and IAA on relative expression levels of SaHMAs (A–C), SaNramps (D–F) and SaZIPs (G–K) genes. Error bars represent the standard deviation (SD) from of three individual replicates. The different letters on the error bars indicate significant differences among the treatments at p < 0.05.

Previous studies showed that endophyte inoculation improved plant biomass and root growth (Zhang et al., 2013; Chen et al., 2014a,b; Cocozza et al., 2014). In the hydroponic experiment, both Sasm05 and IAA could promote plant growth and enhanced shoot biomass. IAA is a regulator known to stimulate both rapid (e.g., increases in cell elongation) and long-term (e.g., cell division and differentiation) responses in plants (Shi et al., 2009). ACC deaminase can lower plant ethylene levels and thus stimulate plant growth (Glick et al., 2007). Furthermore, siderophores are able to bind metals, improving plant growth and enhancing phytoremediation processes (Rajkumar et al., 2010). Therefore, it was reasonable that Sasm05 treatment showed greater improvement in plant growth and root biomass compared to the exogenous IAA treatment.

As a transport inhibitor of IAA, NPA significantly decreased the root IAA concentration while it increased the shoot IAA concentration (Gong et al., 2014). Ljung et al. (2001) conducted an experiment in which 40 mM NPA was added to the medium, demonstrating that NPA decreased the amount of IAA and leaf expansion probably by feedback inhibition of IAA biosynthesis. Root length and lateral root development was significantly inhibited after the application of 10 μM NPA compared with the absence of NPA (Casimiro et al., 2001). Further study revealed that the role of NPA is not only related to auxin transport but also closely related to the content of ethylene; the inhibitory effect of NPA on the growth of plant roots may be related to an increase in the ethylene content (Rashotte et al., 2000; Keller et al., 2004; Ruzicka et al., 2007). Here, the root biomass was significantly reduced by NPA, which was consistent with the discovery of Barkoulas et al. (2008), for it might have a significant inhibitory effect on the plant lateral roots (Gong et al., 2014). NPA treatment prevents the lateral roots from penetrating the hypodermis due to the hardening of hypodermis cell walls and the disturbance of gravitropism (Ogawa et al., 2017).

Indole-3-acetic acid is the most common, naturally occurring plant hormone in the auxin class (Marathe et al., 2017). Apart from IAA produced by plants, some bacteria hosted in plant showed the ability to produce IAA and promote plant growth. The IAA produced by Pseudomonas fluorescens HP72 is proposed to act as a stimulator of cell proliferation and elongation and enhance the host uptake of minerals and nutrients from the soil (Suzuki et al., 2003). This promotion effect was outstanding when the plant was grown in a stressed environment, such as stress from water, temperature, salt, pollutants, and so on (Husen et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2016). Thus, growth parameters including chlorophyll synthesis were suppressed under a stressed environment, and the effect of the stress was greater in plants that received no additional IAA treatment than on those treated with exogenous IAA or IAA-producing PGPB. Inoculation with Pantoea alhagi sp. nov. could promote chlorophyll production in the leaves compared to non-inoculated control plants under similar water stress conditions (Chen et al., 2017). Consistently, the addition of Sasm05 and IAA could also significantly increase the chlorophyll concentration (Figure 5).

Mg2+ and Ca2+ are essential to the integrity of the cellular membrane and the intracellular adhesives, and the function of the Ca2+-ATPase and Mg2+-ATPase are important in the maintenance of the intracellular calcium and magnesium level (de la Torre et al., 2000; Lin et al., 2016). In the present study, the activity of Ca2+-ATPase and Mg2+-ATPase were measured, and it was found that both Sasm05 and IAA can activate Ca2+-ATPase and Mg2+-ATPase (Figure 6), indicating that both of them can stimulate photosynthesis. The IAA treatment had a growth-stimulating effect via the simulation of the electrogenic activity of the plasmalemma membrane potential H+-ATPase and the hormonal effects were mediated by a transient elevation in the level of free Ca2+ in the cytosol and generation of reactive oxygen species (Kovaleva et al., 2016). However, all NPA treatments sharply decreased the activity of Ca2+-ATPase and Mg2+-ATPase, as well as decreasing the leaf chlorophyll content (Figure 5), which illustrated that IAA and its transport had dramatic effects on the improvement of plant photosynthesis.

Although a lot of literatures indicated that PGPB can increase heavy metal uptake in plant, the opposite results were also not unusual. Mesa et al. (2015) found that endophytic cultivable bacteria of the metal bioaccumulator Spartina maritima improve plant growth but not metal uptake in polluted marshes soils. Here we found that Sasm05 increase Cd concentration in both root and shoot while exogenous have no significant effects (Figure 3). Therefore, we assumed that it should be related with transporter gene expression regulation.

Many metal transporters and homologous genes involved in metal transport in plants have been identified by genetic and molecular techniques, such as sequence comparison. A suite of metal-sensing regulatory proteins from bacterial sources orchestrated metal homeostasis by allosterically coupling the selective binding of target metals to the activity of the DNA-binding domains for detecting and responding to toxic levels of heavy metals (Furukawa et al., 2015). Although our previous data showed that the IAA-producing PGPB Sphingomonas SaMR12 could affect the gene expression of transporters (Pan et al., 2017), the effects of exogenous IAA and the auxin transport inhibitor were the first time compared. In Arabidopsis, AtHMA2 and AtHMA4 are essential for Zn and Cd translocation from the roots to the shoots (Eren, 2004; Verret et al., 2004). AtHMA3 is another heavy metal ATPase transporter that is located in the tonoplast and is associated with Cd and Zn tolerance (Morel et al., 2009). And in Cucumber, CsHMA3, CsHMA4 were predominantly expressed in the roots and up-regulated by excess Zn and Cd (Migocka et al., 2015). SaHMA3 of S. alfredii was a Cd transporter, constitutively expressed in both shoots and roots, and encoded tonoplast-localized proteins (Zhang et al., 2016). Although no significantly induced expression of SaHMA2, SaHMA3 and SaHMA4 was observed after addition of IAA or NPA, Sasm05 inoculation increased their expression levels except for SaHMA4 in the roots (Figures 7A–C), indicating that Sasm05 might enhance Cd root to shoot translocation by regulation these genes.

In Arabidopsis, six AtNramp1-6 genes encode the NRAMP proteins. AtNramp1 played an important role on plant iron homoeostasis (Curie et al., 2000). AtNramp3 and AtNramp4 are localized to the vacuolar membrane and encode tonoplastic proteins with redundant functions (Lanquar et al., 2005). They are metal transporters with a broad range of substrate specificities including Fe, Cd, and Zn (Lanquar et al., 2005, 2010). AtNramp6 is an intracellular Cd transporter that functions inside the cell either by mobilizing Cd from its storage compartment or by taking up Cd into a cellular compartment where it becomes toxic (Cailliatte et al., 2009). However, in rice, OsNramp5 has been reported to be a major transporter for Cd uptake (Ishimaru et al., 2012; Sasaki et al., 2012), and the expression of OsNramp5 was increased in the roots and shoots in the presence of Cd (Ishimaru et al., 2012). In this research, we found the variation of the transcription levels of SaNramp1, SaNramp3, and SaNramp6 in the different treatments are not uniform (Figures 7D–F), indicating the function of these genes may also differ. NPA greatly inhibited the expression of these genes, while Sasm05 and IAA increased their expression. Those results indicated that Sasm05 and IAA might help the plant alleviate Cd toxicity to the cells, but more data about the functions of these genes in S. alfredii are needed.

Present studies have indicated that the ZIP family is the main membrane transporter responsible for possible Cd2+ uptake and transport (Zhu et al., 2013). As expected, the expression levels of ZIP family genes in the shoots and roots were all up-regulated by the Sasm05 treatment, except for ZIP3 in the roots (Figures 7G–K), suggesting that Sasm05 causes more Cd2+ to enter the cell. Although the relative expression levels of other genes varied limited in fivefold, the expression of IRT1 was dramatically induced by Sasm05 by 17-fold in the shoots and 9-fold in the roots (Figure 7K), suggesting that Sasm05 promotes plant Cd uptake and transport through up-regulating the expression of the ZIP genes, especially IRT1.

In conclusion, with exposure to Cd, both the endophytic bacterium Sasm05 and exogenous IAA can promote the growth and photosynthesis of S. alfredii, and Sasm05 has greater effects on the enhancement of phytoextraction compare with IAA treatment. Moreover, Sasm05 can upregulate the expression of key transporters for Cd uptake, root to shoot translocation as well as detoxification, although IAA can also improve the expression of some transporter genes involved metal uptake and detoxification. These results indicated that the beneficial plant-endophytic bacterial interaction of Sasm05 is but not limited to IAA production. This study analyzed for the first time the effects of PGPB Sasm05 and exogenous IAA on phytoremediation of Cd contaminated soil, through which not only cleared the improvement from IAA treatment, but also illustrated related mechanisms of phytoremediation enhancement from Sasm05. These results will guide our subsequent study on plant growth promoting endophytic bacteria and their application for realizing efficient phytoremediation.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication. In this research, YF, XY, and BC designed the experiment; BC, SL, YW, FP, QW, and JY performed the experiment; SL, BC, and QW analyzed the data and drafted the manuscript; YF, BC, XX, FP, and KK revised the manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

This research was supported by the National Science Foundation for Post-doctoral Scientists of China (2016M591999), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 41771345), and the National Key Research and Development Projects of China (2017YFD0801104 and 2016YFD0800801).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmicb.2017.02538/full#supplementary-material

Ali, S., Charles, T. C., and Glick, B. R. (2017). “Endophytic phytohormones and their role in plant growth promotion,” in Functional Importance of the Plant Microbiome: Implications for Agriculture, Forestry and Bioenergy, ed. S. L. Doty (Cham: Springer International Publishing), 89–105.

Barabasz, A., Wilkowska, A., Tracz, K., Ruszczyńska, A., Bulska, E., Mills, R. F., et al. (2013). Expression of HvHMA2 in tobacco modifies Zn–Fe–Cd homeostasis. J. Plant Physiol. 170, 1176–1186. doi: 10.1016/j.jplph.2013.03.018

Barkoulas, M., Hay, A., Kougioumoutzi, E., and Tsiantis, M. (2008). A developmental framework for dissected leaf formation in the Arabidopsis relative Cardamine hirsuta. Nat. Genet. 40, 1136–1141. doi: 10.1038/ng.189

Bashan, Y., Kamnev, A. A., and De-Bashan, L. E. (2013). Tricalcium phosphate is inappropriate as a universal selection factor for isolating and testing phosphate-solubilizing bacteria that enhance plant growth: a proposal for an alternative procedure. Biol. Fert. Soils 49, 465–479. doi: 10.1007/s00374-012-0737-7

Cailliatte, R., Lapeyre, B., Briat, J. F., Mari, S., and Curie, C. (2009). The NRAMP6 metal transporter contributes to cadmium toxicity. Biochem. J. 422, 217–228. doi: 10.1042/BJ20090655

Casimiro, I., Marchant, A., Bhalerao, R. P., Beeckman, T., and Dhooge, S. (2001). Auxin transport promotes Arabidopsis lateral root initiation. Plant Cell 13, 843–852. doi: 10.1105/tpc.13.4.843

Chen, B., Shen, J., Zhang, X., Pan, F., Yang, X., and Feng, Y. (2014a). The endophytic bacterium, Sphingomonas SaMR12, improves the potential for zinc phytoremediation by its host, Sedum alfredii. PLOS ONE 9:e106826. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0106826

Chen, B., Zhang, Y., Rafiq, M. T., Khan, K. Y., Pan, F., Yang, X., et al. (2014b). Improvement of cadmium uptake and accumulation in Sedum alfredii by endophytic bacteria Sphingomonas SaMR12: effects on plant growth and root exudates. Chemosphere 117, 367–373. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2014.07.078

Chen, C., Xin, K., Liu, H., Cheng, J., Shen, X., Wang, Y., et al. (2017). Pantoea alhagi, a novel endophytic bacterium with ability to improve growth and drought tolerance in wheat. Sci. Rep. 7:41564. doi: 10.1038/srep41564

Clemens, S., Aarts, M. G. M., Thomine, S., and Verbruggen, N. (2013). Plant science: the key to preventing slow cadmium poisoning. Trends Plant Sci. 18, 92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2012.08.003

Cocozza, C., Vitullo, D., Lima, G., Maiuro, L., Marchetti, M., and Tognetti, R. (2014). Enhancing phytoextraction of Cd by combining poplar (clone “I-214”) with Pseudomonas fluorescens and microbial consortia. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 21, 1796–1808. doi: 10.1007/s11356-013-2073-3

Curie, C., Alonso, J. M., Le, J. M., Ecker, J. R., and Briat, J. F. (2000). Involvement of NRAMP1 from Arabidopsis thaliana in iron transport. Biochem. J. 347, 749–755. doi: 10.1042/bj3470749

de la Torre, F. R., Salibián, A., and Ferrari, L. (2000). Biomarkers assessment in juvenile Cyprinus carpio exposed to waterborne cadmium. Environ. Pollut. 109, 277–282. doi: 10.1016/S0269-7491(99)00263-8

Defez, R., Andreozzi, A., and Bianco, C. (2017). The overproduction of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) in endophytes upregulates nitrogen fixation in both bacterial cultures and inoculated rice plants. Microb. Ecol. 74, 441–452. doi: 10.1007/s00248-017-0948-4

Defez, R., Esposito, R., Angelini, A., and Bianco, C. (2016). Overproduction of indole-3-acetic acid in free-living rhizobia induces transcriptional changes resembling those occurring inside nodule bacteroids. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 29, 484–495. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-01-16-0010-R

Duca, D., Lorv, J., Patten, C. L., Rose, D., and Glick, B. R. (2014). Indole-3-acetic acid in plant-microbe interactions. Antonie Van Leeuwenhoek 106, 85–125. doi: 10.1007/s10482-013-0095-y

Eren, E. (2004). Arabidopsis HMA2, a divalent heavy metal-transporting PIB-Type ATPase, is involved in cytoplasmic Zn2+ homeostasis. Plant Physiol. 136, 3712–3723. doi: 10.1104/pp.104.046292

Furukawa, K., Ramesh, A., Zhou, Z., Weinberg, Z., Vallery, T., Winkler, W. C., et al. (2015). Bacterial riboswitches cooperatively bind Ni 2+ or Co 2+ ions and control expression of heavy metal transporters. Mol. Cell 57, 1088–1098. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2015.02.009

Gao, J., Sun, L., Yang, X., and Liu, J. X. (2013). Transcriptomic analysis of cadmium stress response in the heavy metal hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Hance. PLOS ONE 8:e64643. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0064643

Glick, B. R. (2010). Using soil bacteria to facilitate phytoremediation. Biotechnol. Adv. 28, 367–374. doi: 10.1016/j.biotechadv.2010.02.001

Glick, B. R. (2012). Plant growth-promoting bacteria: mechanisms and applications. Scientifica 2012:963401. doi: 10.6064/2012/963401

Glick, B. R. (2014). Bacteria with ACC deaminase can promote plant growth and help to feed the world. Microbiol. Res. 169, 30–39. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2013.09.009

Glick, B. R., Cheng, Z., Czarny, J., and Duan, J. (2007). Promotion of plant growth by ACC deaminase-producing soil bacteria. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 119, 329–339. doi: 10.1007/s10658-007-9162-4

Gong, B., Miao, L., Kong, W., Bai, J., Wang, X., Wei, M., et al. (2014). Nitric oxide, as a downstream signal, plays vital role in auxin induced cucumber tolerance to sodic alkaline stress. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 83, 258–266. doi: 10.1016/j.plaphy.2014.08.004

Husen, A., Iqbal, M., and Aref, I. M. (2016). IAA-induced alteration in growth and photosynthesis of pea (Pisum sativum L.) plants grown under salt stress. J. Environ. Biol. 37, 421–429.

Hynes, R. K., Leung, G. C. Y., Hirkala, D. L. M., and Nelson, L. M. (2008). Isolation, selection, and characterization of beneficial rhizobacteria from pea, lentil, and chickpea grown in western Canada. Can. J. Microbiol. 54, 248–258. doi: 10.1139/w08-008

Ishimaru, Y., Takahashi, R., Bashir, K., Shimo, H., Senoura, T., Sugimoto, K., et al. (2012). Characterizing the role of rice NRAMP5 in manganese, iron and cadmium transport. Sci. Rep. 2:286. doi: 10.1038/srep00286

Jasim, B., Jimtha, J. C., Shimil, V., Jyothis, M., and Radhakrishnan, E. K. (2014). Studies on the factors modulating indole-3-acetic acid production in endophytic bacterial isolates from Piper nigrum and molecular analysis of ipdc gene. J. Appl. Microbiol. 117, 786–799. doi: 10.1111/jam.12569

Jin, P., Zhu, H., Wang, J., Chen, J., and Wang, X. (2013). Effect of methyl jasmonate on energy metabolism in peach fruit during chilling stress. J. Sci. Food Agric. 93, 1827–1832. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.5973

Kazan, K. (2013). Auxin and the integration of environmental signals into plant root development. Ann. Bot. 112, 1655–1665. doi: 10.1093/aob/mct229

Keller, C. P., Stahlberg, R., Barkawi, L. S., and Cohen, J. D. (2004). Long-term inhibition by auxin of leaf blade expansion in bean and Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 134, 1217–1226. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.032300

Khalid, A., Arshad, M., and Zahir, Z. A. (2004). Screening plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for improving growth and yield of wheat. J. Appl. Microbiol. 94, 473–480. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2672.2003.02161.x

Khan, A. L., Waqas, M., Kang, S., Al-Harrasi, A., Hussain, J., Al-Rawahi, A., et al. (2014). Bacterial endophyte Sphingomonas sp. LK11 produces gibberellins and IAA and promotes tomato plant growth. J. Microbiol. 52, 689–695. doi: 10.1007/s12275-014-4002-7

Korshunova, Y. O., Eide, D., Clark, W. G., Guerinot, M. L., and Pakrasi, H. B. (1999). The IRT1 protein from Arabidopsis thaliana is a metal transporter with a broad substrate range. Plant Mol. Biol. 40, 37–44. doi: 10.1023/A:1026438615520

Kovaleva, L. V., Voronkova, A. S., Zakharovab, E. V., Minkinaa, Y. V., Timofeevaa, G. V., and Andreev, I. M. (2016). Exogenous IAA and ABA stimulate germination of petunia male gametophyte by activating Ca2+-dependent K+-channels and by modulating the activity of plasmalemma H+-ATPase and actin cytoskeleton. Russ. J. Dev. Biol. 47, 109–121. doi: 10.1134/S1062360416030036

Lanquar, V., Lelievre, F. S., Hames, C., Alcon, C., and Neumann, D. (2005). Mobilization of vacuolar iron by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is essential for seed germination on low iron. EMBO J. 24, 4041–4051. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600864

Lanquar, V., Ramos, M. S., Lelievre, F., Barbier-Brygoo, H., Krieger-Liszkay, A., Kramer, U., et al. (2010). Export of vacuolar manganese by AtNRAMP3 and AtNRAMP4 is required for optimal photosynthesis and growth under manganese deficiency. Plant Physiol. 152, 1986–1999. doi: 10.1104/pp.109.150946

Lin, J., Zhao, H., Xiang, L., Xia, J., Wang, L., Li, X., et al. (2016). Lycopene protects against atrazine-induced hepatic ionic homeostasis disturbance by modulating ion-transporting ATPases. J. Nutri. Biochem. 27, 249–256. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2015.09.009

Liu, H., Zhao, H., Wu, L., Liu, A., Zhao, F. J., and Xu, W. (2017). Heavy metal ATPase 3 (HMA3) confers cadmium hypertolerance on the cadmium/zinc hyperaccumulator Sedum plumbizincicola. New Phytol. 215, 687–698. doi: 10.1111/nph.14622

Ljung, K., Bhalerao, R. P., and Sandberg, G. (2001). Sites and homeostatic control of auxin biosynthesis in Arabidopsis during vegetative growth. Plant J. 28, 465–474. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2001.01173.x

Ma, Y., Rajkumar, M., Moreno, A., Zhang, C., and Freitas, H. (2017). Serpentine endophytic bacterium Pseudomonas azotoformans ASS1 accelerates phytoremediation of soil metals under drought stress. Chemosphere 185, 75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2017.06.135

Ma, Y., Rajkumar, M., Zhang, C., and Freitas, H. (2016). Beneficial role of bacterial endophytes in heavy metal phytoremediation. J. Environ. Manage. 174, 14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.02.047

Marathe, R., Phatake, Y., Shaikh, A., Shinde, B., and Gajbhiye, M. (2017). Effect of IAA produced by Pseudomonas aeruginosa 6A (BC4) on seed germination and plant growth of glycin max. J. Exp. Biol. Agric. Sci. 5, 351–358.

Mesa, J., Mateos-Naranjo, E., Caviedes, M. A., Redondo-Gómez, S., Pajuelo, E., and Rodríguez-Llorente, I. D. (2015). Endophytic cultivable bacteria of the metal bioaccumulator Spartina maritima improve plant growth but not metal uptake in polluted marshes soils. Front. Microbiol. 6:1450. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01450

Migocka, M., Papierniak, A., Maciaszczyk-dziubinska, E., Posyniak, E., and Kosieradzka, A. (2015). Molecular and biochemical properties of two P1B2-ATPases, CsHMA3 and CsHMA4, from cucumber. Plant Cell Environ. 38, 1127–1141. doi: 10.1111/pce.12447

Milner, M. J., Seamon, J., Craft, E., and Kochian, L. V. (2013). Transport properties of members of the ZIP family in plants and their role in Zn and Mn homeostasis. J. Exp. Bot. 64, 369–381. doi: 10.1093/jxb/ers315

Morel, M., Crouzet, J., Gravot, A., Auroy, P., Leonhardt, N., Vavasseur, A., et al. (2009). AtHMA3, a P1B-ATPase allowing Cd/Zn/Co/Pb vacuolar storage in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 149, 894–904. doi: 10.1104/pp.108.130294

Ogawa, A., Matsunami, M., Suzuki, Y., Toyofuku, K., and Wabiko, H. (2017). Lateral root elongation inside the basal cortex of the seminal root is caused by the changes in auxin distribution to the root system of rice (Oryza sativa L.) seedlings. Plant Root 11, 10–15. doi: 10.3117/plantroot.11.10

Pan, F., Luo, S., Shen, J., Wang, Q., Ye, J., Meng, Q., et al. (2017). The effects of endophytic bacterium SaMR12 on Sedum alfredii Hance metal ion uptake and the expression of three transporter family genes after cadmium exposure. Environ. Sci. Pollut. R. 24, 9350–9360. doi: 10.1007/s11356-017-8565-9

Penrose, D. M., and Glick, B. R. (2003). Methods for isolating and characterizing ACC deaminase-containing plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Physiol. Plant. 118, 10–15. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-3054.2003.00086.x

Rajkumar, M., Ae, N., and Freitas, H. (2009). Endophytic bacteria and their potential to enhance heavy metal phytoextraction. Chemosphere 77, 153–160. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2009.06.047

Rajkumar, M., Ae, N., Prasad, M. N., and Freitas, H. (2010). Potential of siderophore-producing bacteria for improving heavy metal phytoextraction. Trends Biotechnol. 28, 142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.12.002

Rashotte, A. M., Brady, S. R., Reed, R. C., Ante, S. J., and Muday, G. K. (2000). Basipetal auxin transport is required for gravitropism in roots of Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 122, 481–490. doi: 10.1104/pp.122.2.481

Ren, H., Wei, J., and Shen, Y. (1995). Malate regulation of Mg 2+-ATpase of chloroplast coupling factor. Photosynth. Res. 43, 19–25. doi: 10.1007/BF00029458

Ruzicka, K., Ljung, K., Vanneste, S., Podhorská, R., Beeckman, T., Friml, J., et al. (2007). Ethylene regulates root growth through effects on auxin biosynthesis and transport- dependent auxin distribution. Plant Cell 19, 2197–2212. doi: 10.1105/tpc.107.052126

Santoyo, G., Moreno-Hagelsieb, G., Orozco-Mosqueda Mdel, C., and Glick, B. R. (2016). Plant growth-promoting bacterial endophytes. Microbiol. Res. 183, 92–99. doi: 10.1016/j.micres.2015.11.008

Sasaki, A., Yamaji, N., Yokosho, K., and Ma, J. F. (2012). Nramp5 is a major transporter responsible for manganese and cadmium uptake in rice. Plant Cell 24, 2155–2167. doi: 10.1105/tpc.112.096925

Sheng, X. F., Xia, J. J., Jiang, C. Y., He, L. Y., and Qian, M. (2008). Characterization of heavy metal-resistant endophytic bacteria from rape (Brassica napus) roots and their potential in promoting the growth and lead accumulation of rape. Environ. Pollut. 156, 1164–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.envpol.2008.04.007

Shi, Y., Lou, K., and Li, C. (2009). Promotion of plant growth by phytohormone-producing endophytic microbes of sugar beet. Biol. Fertil. Soils 45, 645–653. doi: 10.1007/s00374-009-0376-9

Strader, L. C., Culler, A. H., Cohen, J. D., and Bartel, B. (2010). Conversion of endogenous indole-3-butyric acid to indole-3-acetic acid drives cell expansion in Arabidopsis seedlings. Plant Physiol. 153, 1577–1586. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.157461

Sun, Z., Liu, K., Zhang, J., Zhang, Y., Xu, K., Yu, D., et al. (2017). IAA producing Bacillus altitudinis alleviates iron stress in Triticum aestivum L. seedling by both bioleaching of iron and up-regulation of genes encoding ferritins. Plant Soil 25, 1–11. doi: 10.1007/s11104-017-3218-9

Suzuki, S., He, Y., and Oyaizu, H. (2003). Indole-3-acetic acid production in Pseudomonas fluorescens HP72 and its association with suppression of creeping bentgrass brown patch. Curr. Microbiol. 47, 138–143. doi: 10.1007/s00284-002-3968-2

Teale, W. D., Paponov, I. A., and Palme, K. (2006). Auxin in action: signalling, transport and the control of plant growth and development. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 7, 847–859. doi: 10.1038/nrm2020

Thomine, S., Lelievre, F., Debarbieux, E., Schroeder, J. I., and Barbier-Brygoo, H. (2003). AtNRAMP3, a multispecific vascular metal transporter involved in plant responses to iron deficiency. Plant J. 34, 685–695. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-313X.2003.01760.x

Thomine, S., Wang, R., Ward, J. M., Crawford, N. M., and Schroeder, J. I. (2000). Cadmium and iron transport by members of a plant metal transporter family in Arabidopsis with homology to Nramp genes. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 4991–4996. doi: 10.1073/pnas.97.9.4991

Tiwari, S., Sarangi, B. K., and Thul, S. T. (2016). Identification of arsenic resistant endophytic bacteria from Pteris vittata roots and characterization for arsenic remediation application. J. Environ. Manage. 180, 359–365. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2016.05.029

Verret, F., Gravot, A., Auroy, P., Leonhardt, N., and David, P. (2004). Overexpression of AtHMA4 enhances root-to-shoot translocation of zinc and cadmium and plant metal tolerance. FEBS Lett. 576, 306–312. doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.09.023

Vert, G. (2002). IRT1, an Arabidopsis transporter essential for iron uptake from the soil and for plant growth. Plant Cell 14, 1223–1233. doi: 10.1105/tpc.001388

Weisburg, W. G., Barns, S. M., Pelletier, D. A., and Lane, D. J. (1991). 16S ribosomal DNA amplification for phylogenetic study. J. Bacteriol. 173, 697–703. doi: 10.1128/jb.173.2.697-703.1991

Winer, J., Jung, C. K., Shackel, I., and Williams, P. M. (1999). Development and validation of real-time quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction for monitoring gene expression in cardiac myocytes in vitro. Anal. Biochem. 270, 41–49. doi: 10.1006/abio.1999.4085

Wong, C. K. E., and Cobbett, C. S. (2009). HMA P-type ATPases are the major mechanism for root-to-shoot Cd translocation in Arabidopsis thaliana. New Phytol. 181, 71–78. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-8137.2008.02638.x

Yang, X. E., Long, X. X., Ye, H. B., He, Z. L., Calvert, D. V., and Stoffella, P. J. (2004). Cadmium tolerance and hyperaccumulation in a new Zn-hyperaccumulating plant species (Sedum alfredii Hance). Plant Soil 259, 181–189. doi: 10.1023/B:PLSO.0000020956.24027.f2

Zhang, J., Zhang, M., Shohag, M. J. I., Tian, S., Song, H., Feng, Y., et al. (2016). Enhanced expression of SaHMA3 plays critical roles in Cd hyperaccumulation and hypertolerance in Cd hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Hance. Planta 243, 577–589. doi: 10.1007/s00425-015-2429-7

Zhang, X., Lin, L., Chen, M., Zhu, Z., Yang, W., Chen, B., et al. (2012). A nonpathogenic Fusarium oxysporum strain enhances phytoextraction of heavy metals by the hyperaccumulator Sedum alfredii Hance. J. Hazard. Mater. 229-230, 361–370. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2012.06.013

Zhang, X., Lin, L., Zhu, Z., Yang, X., Wang, Y., and An, Q. (2013). Colonization and modulation of host growth and metal uptake by endophytic bacteria of Sedum alfredii. Int. J. Phytoremediat. 15, 51–64. doi: 10.1080/15226514.2012.670315

Zhu, X. F., Wang, Z. W., Dong, F., Lei, G. J., Shi, Y. Z., Li, G. X., et al. (2013). Exogenous auxin alleviates cadmium toxicity in Arabidopsis thaliana by stimulating synthesis of hemicellulose 1 and increasing the cadmium fixation capacity of root cell walls. J. Hazard. Mater. 263, 398–403. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2013.09.018

Keywords: hyperaccumulator, gene expression, metal transporter, plant growth-promoting bacteria (PGPB), Cd

Citation: Chen B, Luo S, Wu Y, Ye J, Wang Q, Xu X, Pan F, Khan KY, Feng Y and Yang X (2017) The Effects of the Endophytic Bacterium Pseudomonas fluorescens Sasm05 and IAA on the Plant Growth and Cadmium Uptake of Sedum alfredii Hance. Front. Microbiol. 8:2538. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.02538

Received: 31 March 2017; Accepted: 06 December 2017;

Published: 19 December 2017.

Edited by:

Ying Ma, University of Coimbra, PortugalReviewed by:

Roberta Fulthorpe, University of Toronto Scarborough, CanadaCopyright © 2017 Chen, Luo, Wu, Ye, Wang, Xu, Pan, Khan, Feng and Yang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ying Feng, eWZlbmdAemp1LmVkdS5jbg==

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.