- 1National Microbiology Laboratory at Lethbridge, Public Health Agency of Canada, Lethbridge, AB, Canada

- 2Department of Biological Sciences, University of Lethbridge, Lethbridge, AB, Canada

- 3Lethbridge Research and Development Centre, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada, Lethbridge, AB, Canada

Campylobacter jejuni is a leading human enteric pathogen worldwide and despite an improved understanding of its biology, ecology, and epidemiology, limited tools exist for identifying strains that are likely to cause disease. In the current study, we used subtyping data in a database representing over 24,000 isolates collected through various surveillance projects in Canada to identify 166 representative genomes from prevalent C. jejuni subtypes for whole genome sequencing. The sequence data was used in a genome-wide association study (GWAS) aimed at identifying accessory gene markers associated with clinically related C. jejuni subtypes. Prospective markers (n = 28) were then validated against a large number (n = 3,902) of clinically associated and non-clinically associated genomes from a variety of sources. A total of 25 genes, including six sets of genetically linked genes, were identified as robust putative diagnostic markers for clinically related C. jejuni subtypes. Although some of the genes identified in this study have been previously shown to play a role in important processes such as iron acquisition and vitamin B5 biosynthesis, others have unknown function or are unique to the current study and warrant further investigation. As few as four of these markers could be used in combination to detect up to 90% of clinically associated isolates in the validation dataset, and such markers could form the basis for a screening assay to rapidly identify strains that pose an increased risk to public health. The results of the current study are consistent with the notion that specific groups of C. jejuni strains of interest are defined by the presence of specific accessory genes.

Introduction

Campylobacter jejuni is one of the leading causes of bacterial foodborne gastroenteritis in the world; it is estimated to be responsible for as much as 14% of all cases of diarrheal disease, translating to more than 400 million cases of campylobacteriosis annually (Duong and Konkel, 2009). In Canada, annual incidence rates nearing 30 cases per 100,000 individuals have been reported (Galanis, 2007), although statistical models that account for unreported and undiagnosed cases suggest this rate could be as high as 447 cases per 100,000 individuals (Thomas et al., 2013). While a majority of cases are self-limiting, post-infection complications, such as Guillain-Barré syndrome can be life threatening (Nachamkin et al., 1998; Nachamkin, 2002). Campylobacter jejuni is commonly isolated from the gastrointestinal tract of many different wild and domesticated species, including companion animals and food animals such as poultry and cattle (Lastovica et al., 2014). Faecal contamination from carrier animals is considered to be a primary source of C. jejuni in the environment and on food products (Koenraad et al., 1997). This bacterium is highly prevalent in raw poultry meat and poultry by-products (Suzuki and Yamamoto, 2009; Williams and Oyarzabal, 2012), and the consumption and handling of contaminated poultry products is thought to be the primary source of exposure leading to human infection. Nonetheless, the epidemiology of campylobacteriosis is complex, with a large number of cases that appear to be sporadic (Silva et al., 2011), a range of animal and environmental reservoirs (Whiley et al., 2013), and multiple potential routes for the introduction of C. jejuni into the food chain as well as non-food-related pathways of exposure (Pintar et al., 2016).

Although epidemiological evidence suggests that not all C. jejuni strains or genetic lineages pose an equal risk to human health, our current understanding of C. jejuni subtype-dependent pathogenesis is incomplete. In contrast to other enteric pathogens, C. jejuni does not possess a number of the classical virulence factors (e.g., Type III or Type IV secretion systems, enterotoxins) found in other pathogens (Havelaar et al., 2009). Previous studies have identified genetic determinants that are important for C. jejuni pathogenicity (Dasti et al., 2010), but they are generally conserved across the species. Therefore, these factors have little predictive power for the identification of isolates with a higher propensity to cause disease in humans.

With the advent of inexpensive and high-throughput whole genome sequencing, Genome Wide Association Studies (GWAS) are increasingly being applied to bacterial genomics as tools for the identification of genetic markers associated with a phenotype or trait of interest (Read and Massey, 2014). GWAS represent a “top-down” approach to molecular marker discovery because the genomic content of “test” and “control” groups is compared and analyzed to identify genetic variation that is strongly associated with a given trait. This is in contrast to “bottom-up” approaches where individual genetic factors are manipulated to observe a phenotypic effect. The utility of GWAS lies in their ability to test many genetic factors in order to reveal associations with the phenotype of interest without a priori assumptions on the specific biological processes involved (Read and Massey, 2014). GWAS have been utilized to identify mutations and other polymorphisms associated with antibiotic resistance in Mycobacterium tuberculosis (Farhat et al., 2013), Staphylococcus aureus (Alam et al., 2014), and Streptococcus pneumoniae (Chewapreecha et al., 2014). In Campylobacter, GWAS have been used to identify genetic factors related to the Guillain-Barré Syndrome (Taboada et al., 2007), host adaptation in C. jejuni and Campylobacter coli (Sheppard et al., 2013), and has recently been used to identify markers associated with the survival of C. jejuni in the poultry production chain (Yahara et al., 2016).

In this study, we have used isolates from the Canadian Campylobacter Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting Database (C3GFdb) to perform a GWAS aimed at identifying genetic determinants preferentially found among C. jejuni lineages associated with human disease. Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting (CGF) (Clark et al., 2012; Taboada et al., 2012) has been used as the primary tool for subtyping of C. jejuni isolates made available through a range of projects in Canada, including the FoodNet Canada sentinel surveillance program, the Canadian Integrated Program for Antimicrobial Surveillance, the Canadian Food Inspection Agency’s microbiological baseline survey of poultry, and several projects that incorporate human, food animal, wild animal, retail food, and environmental sampling activities. The C3GFdb currently contains subtyping data for 24,142 Campylobacter isolates from human (n = 4,697), animal (n = 14,750), and environmental (n = 4,457) sources from across Canada, representing 4,882 unique subtypes. It also contains basic epidemiological metadata for each isolate including host source, date and location, which facilitates contextualization of subtypes within the broader population structure of C. jejuni circulating in Canada.

The goal of the current study was to identify accessory genes with a statistically significant difference in carriage rates in two C. jejuni cohorts that differ in terms of their association with human campylobacteriosis. These genes could be used as diagnostic markers for molecular-based risk assessment and the rapid detection of C. jejuni isolates that pose the greatest risk to human health.

Materials and Methods

Strain Selection

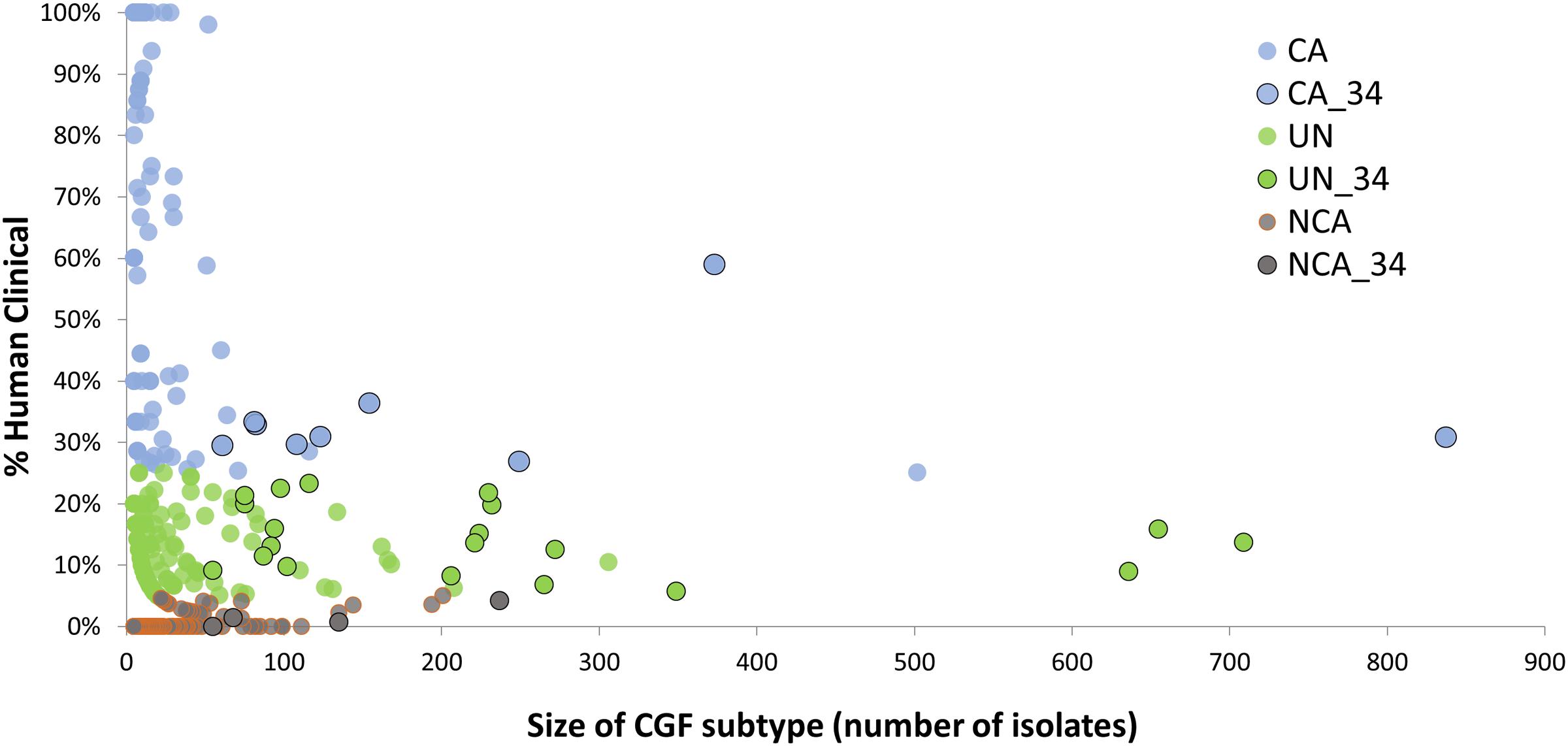

A total of 166 C. jejuni isolates representing 34 of the 100 most prevalent CGF subtypes circulating in Canada were selected from the C3GFdb for whole genome sequencing (Supplementary Table S1). The selected isolates and their respective subtypes represented approximately 31% (7,407/24,142) of all isolates in the database and over 55% (7,407/13,367) of the isolates from the 100 most prevalent CGF subtypes (Figure 1). They have been observed in multiple provinces, sources and hosts, and over multiple years, suggesting that they are endemic and in wide circulation. The dataset selected for WGS was comprised of 72 isolates from animals or retail meat, 54 isolates from environmental sources, and 40 isolates from human clinical cases (Table 1).

FIGURE 1. Identification of CGF subtypes for GWAS analysis of Clinically-Associated (CA) vs. Non-Clinically-Associated (NCA) Campylobacter jejuni subtypes. The C3GFdb was used to identify 166 C. jejuni isolates for whole genome sequencing from 34 highly prevalent CGF subtypes (black outline) that together account for nearly 31% of all isolates in the database, and over 55% of all isolates from the 100 most prevalent CGF subtypes circulating in Canada. These subtypes exhibit differences in their association with human campylobacteriosis, and sequence data from representative isolates was used in a genome-wide association analysis aimed at identifying accessory genes associated with clinically relevant C. jejuni subtypes.

TABLE 1. Epidemiological characteristics of 34 CGF subtypes targeted for whole-genome sequencingbased on the Canadian Campylobacter Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting Database (C3GFdb).

Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

Sequencing was conducted at Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre, BC, Canada using the Illumina HiSeq 2000 platform. Whole genome sequence data for this study has been deposited in the Sequence Read Archive (SRA) at the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI) under the BioProject PRJNA368735. Draft de novo genome assembly of paired-end reads was performed using SPAdes v.2.4.0 (Bankevich et al., 2012) with pre-assembly BayesHammer read correction, default k-mer size testing options, and post-assembly Burrows Wheeler Aligner mismatch correction. Contigs with low coverage or shorter than 500 bp were removed from all subsequent analyses. Genome assembly quality was assessed using QUAST v.2.1 (Gurevich et al., 2013). Prediction of Open Reading Frames (ORFs) and annotation was performed using the PROKKA pipeline v.1.5.2 (Seemann, 2014) using a custom database of non-redundant gene sequences representing five complete and well-annotated C. jejuni reference genomes available from NCBI (Supplementary Table S2).

Definition of a C. jejuni Reference Pan-Genome for the Dataset

Predicted ORFs were queried using a reciprocal best hit approach (Moreno-Hagelsieb and Latimer, 2008; Ward and Moreno-Hagelsieb, 2014) with BLAST v 2.2.29 (Camacho et al., 2009) in order to define a reference pan-genome, the non-redundant set of genes for a set of genome sequences (Méric et al., 2014). Paired BLAST queries were treated as orthologous if they shared ≥80% sequence identity and ≥50% alignment coverage and a single exemplar was included in the pan-genome. The pan-genome defined using this process was used in the subsequent GWAS.

Genome Wide Association Study

Carriage across the dataset of all genes representing the pan-genome was assessed by BLAST analysis. The nucleotide sequence of each gene was queried against the 166 draft genome assemblies using Blastn. Genes were considered to be present if a hit representing ≥80% sequence identity over ≥50% of the length of the query gene was found and considered absent otherwise. In order to facilitate statistical comparison, subtypes were defined as either Non-Clinically Associated (NCA; ≤5% human clinical isolates), Undefined (UN; 5–25% human clinical isolates), or Clinically Associated (CA; ≥25% human clinical isolates). The statistical significance of each gene (p < 0.05) was defined based on its carriage rate in the CA and NCA cohorts and was computed using Fisher’s Exact test statistic in GenomeFisher1; p-values were adjusted for multiple testing using the method of Holm (Holm, 1979; Aickin and Gensler, 1996). Statistically significant genes were subjected to further analysis and validation as outlined below.

In Silico Validation of Putative Diagnostic Marker Genes

In order to select markers with the highest potential for downstream assay development, candidate genes identified by the GWAS analysis were filtered in a stepwise process according to the following conditions: (1) complete absence in the NCA cohort and presence in ≥50% of CA genomes; (2) high sequence identity (>99%) and complete, or near complete, conservation of sequence length (>90%) in the corresponding orthologous gene, when present, among a set of reference genomes (Table 2); and (3) statistical significance (p < 0.05) when the NCA cohort was compared to a combined CA+UN cohort, in which the UN (i.e., undefined) genomes were treated as CA and pooled with the CA genomes. Genes that passed all criteria were selected for in silico validation using a larger set of genome sequences. This validation dataset was created by combining genomes sequenced in house as part of current or previous studies (n = 325) and additional genomes acquired from public repositories (n = 3,955). Publicly available genomes were restricted to those with available epidemiological data (e.g., sample source, country of origin, etc.). To facilitate assignment into NCA, UN, and CA cohorts, in silico CGF was performed on these genomes using MIST (Kruczkiewicz et al., 2013), with a concordance between CGF profiles predicted in silico and those generated in the laboratory estimated to be 96.8% on a subset of 325 isolates (12,583/13,000 matching loci; data not shown); only genomes from CGF subtypes previously observed in the C3GFdb were retained in the validation set (n = 3,902). Each genome was designated to its respective cohort based on the corresponding epidemiological data of the in silico CGF subtype. Finally, the putative diagnostic genes identified by the GWAS using the original set of 166 genomes were tested for statistical significance with the expanded cohorts. The combinatorial effect of different subsets of markers was also assessed to determine if a reduced number of markers could be applied to detect clinically related C. jejuni subtypes without a subsequent loss of sensitivity.

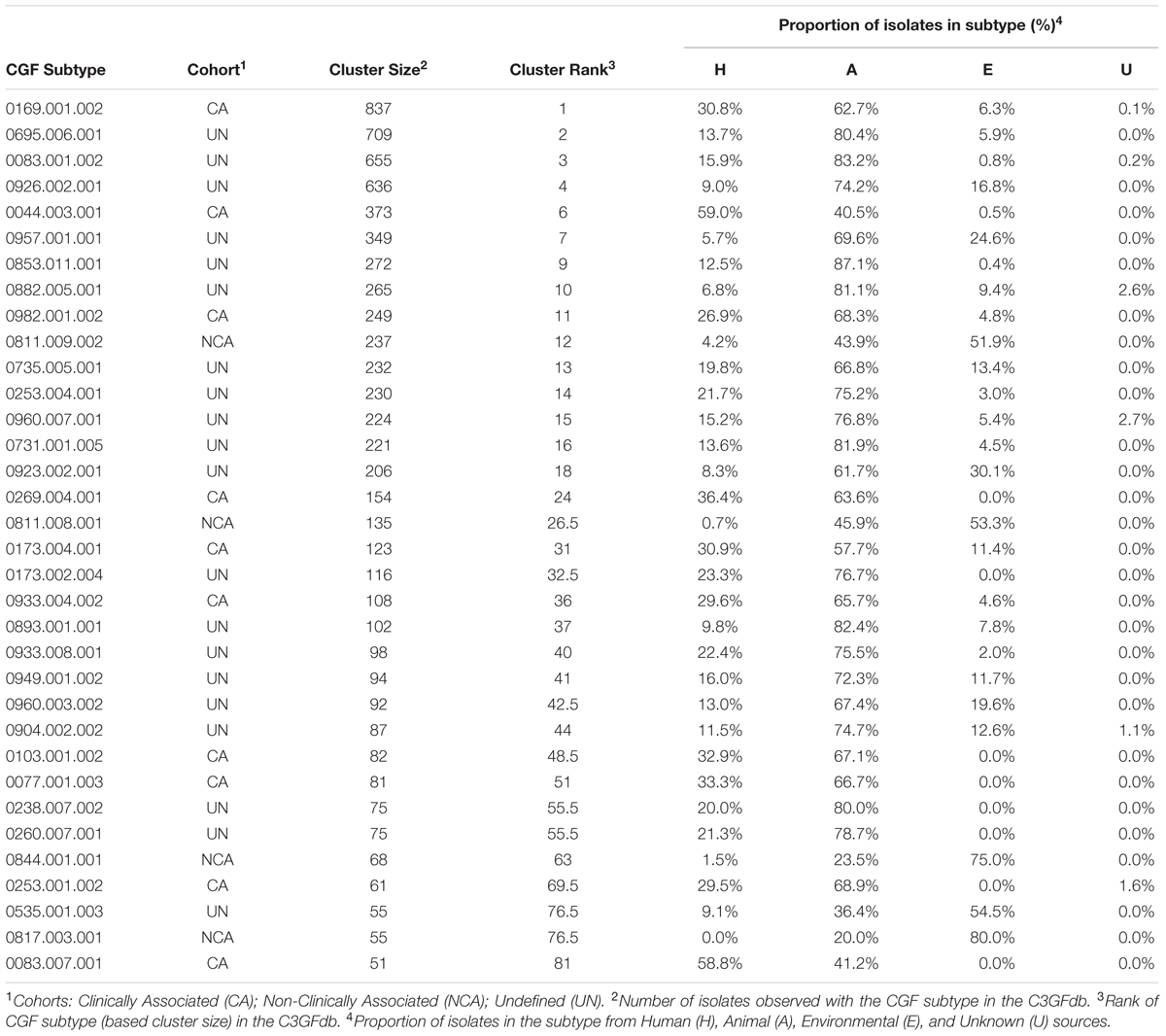

TABLE 2. Significant genes observed after GWAS analysis of genome sequences from representative Clinically Associated (CA) and Non-Clinically Associated (NCA) C. jejuni subtypes.

Results and Discussion

Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and Annotation

The quality of the de novo assembly of the 166 genomes selected as representatives of 34 highly prevalent CGF subtypes in Canada was assessed using QUAST (Gurevich et al., 2013). The average number of reads produced for each genome was 4,161,271 (±1,223,304), for an average coverage of 253× (±74.7×). Individual genome assemblies had an average of 67 (±27) contigs and an N75 of 34,631 bp (±13,815 bp). All genome assemblies had additional parameters in range with what has typically been observed for C. jejuni. The average assembly length (1,660,986 ± 51,283.5 bp), predicted ORFs (1,719 ± 71), and %G+C (30.4 ± 0.13%) were typical of C. jejuni genome assemblies available in the public domain. Annotation of the 166 draft genomes from this study using the PROKKA pipeline (Seemann, 2014) resulted in the identification of 291,502 ORFs. The genome of strain NCTC 11168, which has been completely sequenced (Parkhill et al., 2000), was included in the analysis as a control to assess the completeness of the ORF prediction and annotation process. The original annotation of NCTC 11168 predicted 1,654 ORFs, while a subsequent re-annotation predicted 1,643 ORFs (Gundogdu et al., 2007); in our analysis, the PROKKA pipeline predicted 1,659 ORFs. This small discrepancy is related to the advanced curation used in the re-annotation of NCTC 11168, which resulted in the merging and removal of coding sequences belonging to pseudogenes and phase variable genes. The pan-genome established using this dataset consisted of 3,358 unique ORFs, of which 1,377 were present in all genomes (i.e., core genes) and 1,981 were present in a varying number of genomes (i.e., accessory genes).

Genome Wide Association Study

Of the 166 C. jejuni isolates selected for this study, 35 were assigned to the NCA cohort and represented four different CGF subtypes, 80 were assigned to the UN cohort and represented 20 CGF subtypes, and 51 were assigned to the CA cohort and represented ten CGF subtypes (Table 1). A GWAS was performed in order to identify accessory genes with a biased distribution in CA and NCA cohorts. Although in principle GWAS can be used to identify genetic variation ranging from SNPs to indels involving multiple genes, we chose to focus on accessory genes, as they have excellent potential for the development of rapid, robust, and inexpensive PCR-based diagnostic assays for screening of large numbers of strains. At the same time, it is important to note that other forms of genetic variation may represent valuable targets for tracking strains of interest. Recently, Clark et al. (Clark et al., 2016) showed that large-scale chromosomal inversion could be used to distinguish a subset of outbreak-associated isolates from epidemiologically unrelated co-circulating isolates.

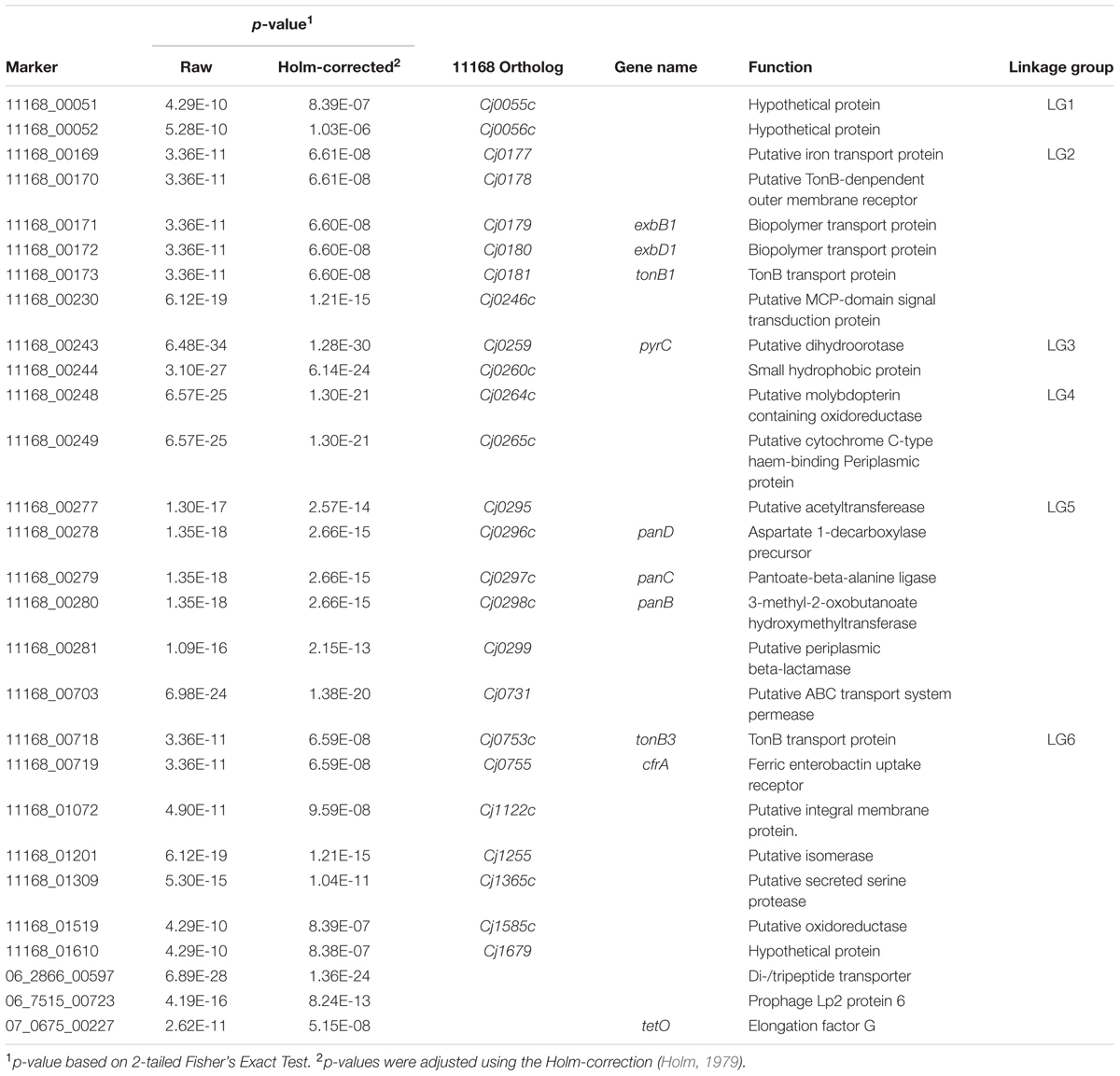

In total, 595 genes showed statistically significant differences in carriage between NCA and CA cohorts (p ≤ 0.05) (Figure 2). Of these, 71 genes were completely absent from the NCA cohort but were present in at least ≥50% of isolates in the CA cohort (Condition 1), and 63 of these genes also maintained high sequence identity (>99%) and near complete sequence coverage (>90%) compared to their respective reference genes (Condition 2). Of these, 28 continued to exhibit robust statistical significance when the NCA cohort was compared to a pooled cohort comprised of all UN and CA genomes (Condition 3). These include six sets of genes that appear to be found in linkage groups (Table 2), with members of each linkage group possessing similar rates of carriage in the dataset. Since linked genes, which are located adjacently on the chromosome, tend to be functionally related and are typically transmitted as a functional unit (Muley and Acharya, 2013), it is likely that their identification in this study was not due to spurious statistical signal.

FIGURE 2. GWAS-based Identification of genes with significant differences in carriage between NCA and CA cohorts. The distribution of p-values observed for 3,358 genes in the C. jejuni pangenome computed for this study after Genome Fisher analysis of gene carriage data for CA and NCA cohorts. (A) Genes from NCTC 11168 genome strains (n = 1,648). (B) Genes from all other genomes (n = 1,710).

Among the linkage groups observed in the GWAS were two sets of genes responsible for encoding iron acquisition systems. We observed that genes encoding both the TonB1-mediated Cj0178 (LG2; Cj0177–Cj0181) and the TonB3-mediated CfrA (LG6; Cj0753c/Cj0755) iron acquisition systems were significantly associated with C. jejuni isolates from clinically related CGF subtypes. As is the case in most pathogens, iron acquisition is considered to be a virulence determinant in C. jejuni and has been linked to successful colonization in vivo (Kim et al., 2003; Palyada et al., 2004; Naikare et al., 2006). CfrA has been shown to be capable of transporting a wide variety of structurally different siderophores, which may contribute to the ability of isolates with these genes to colonize a wide variety of hosts/niches (Naikare et al., 2013).

Another linkage group associated with CA and UN subtypes was comprised of genes that encode the pantothenate (vitamin B5) biosynthesis pathway and β-lactam antibiotic resistance. LG5 encompasses a total of five genes, including a putative acetyltransferase (Cj0295), the panBCD operon (Cj0296c–Cj0298c), which encodes for the pantothenate (vitamin B5) biosynthesis pathway, as well as the gene blaOXA-61 (Cj0299), which encodes a protein that confers resistance to β-lactam antibiotics. These genes were recently implicated in host adaptation in C. jejuni and C. coli, where they were found to be more strongly associated with cattle-specific lineages relative to chicken-specific lineages, possibly as a result of selective pressures created by contemporary and geographically dependent agricultural practices (Sheppard et al., 2013). Although it is generally recognized that chickens are a primary source of human exposure leading to infection, we observed strong statistical signal among CA subtypes for genes previously identified as cattle-associated (Sheppard et al., 2013). Sheppard et al. (2013) suggested that maintenance of these genes in chickens, albeit at a reduced rate, may facilitate rapid-host switching as part of a host-generalist strategy. Moreover, we have observed that a majority of the most prevalent clinically related CGF subtypes, many of which are represented in our GWAS dataset, are associated with both cattle and chickens. This is consistent with the possible role of cattle as an important reservoir for strains that go on to contaminate the chicken production system, ultimately leading to human cases of campylobacteriosis. As this manuscript was being readied for publication, GWAS was used to identify several loci that could be used as “host-segregating” epidemiological markers markers for source attribution (Thépault et al., 2017). Interestingly, one of the loci (Cj0260c) was also identified in our analysis. Thus, while our data suggests that presence of this gene is strongly associated with human clinical isolates, data from the study by Thépault et al. further suggests the allelic information appears highly predictive of host source.

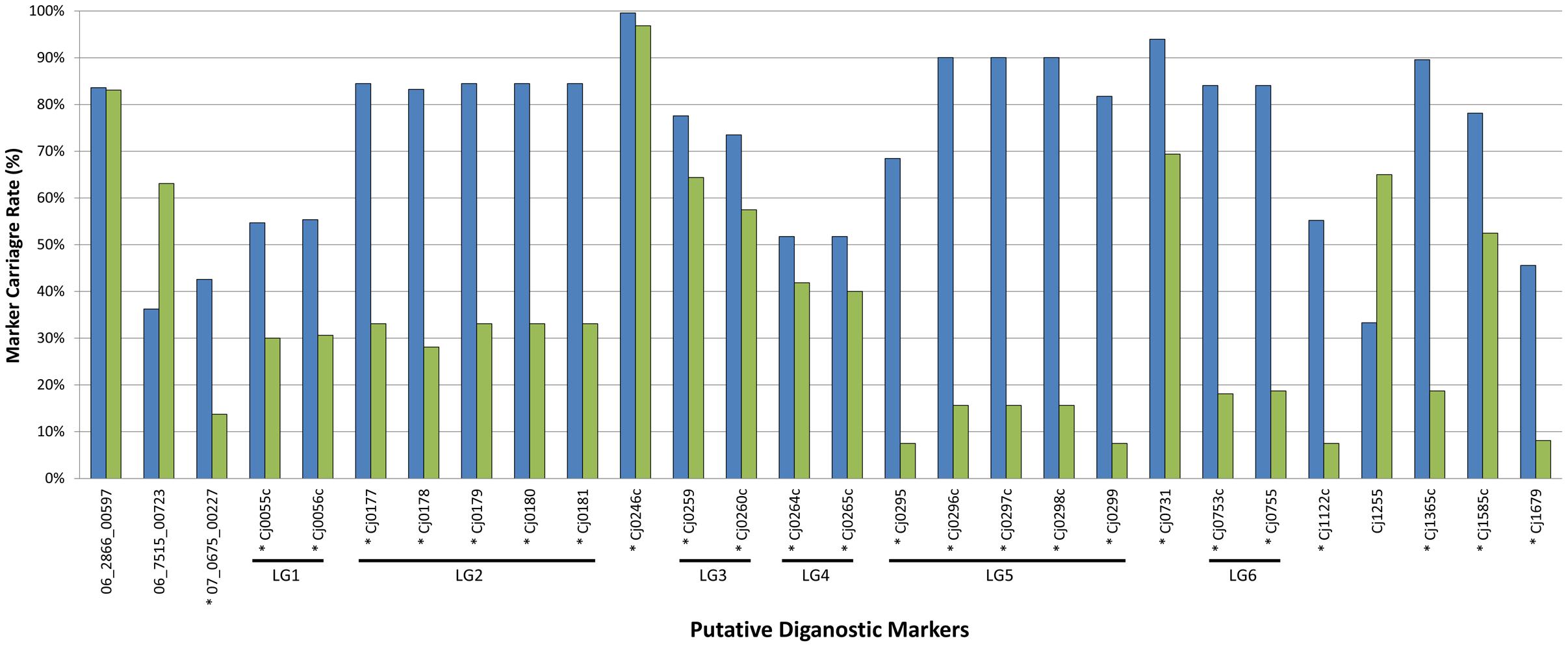

In Silico Validation of Putative Diagnostic Marker Genes

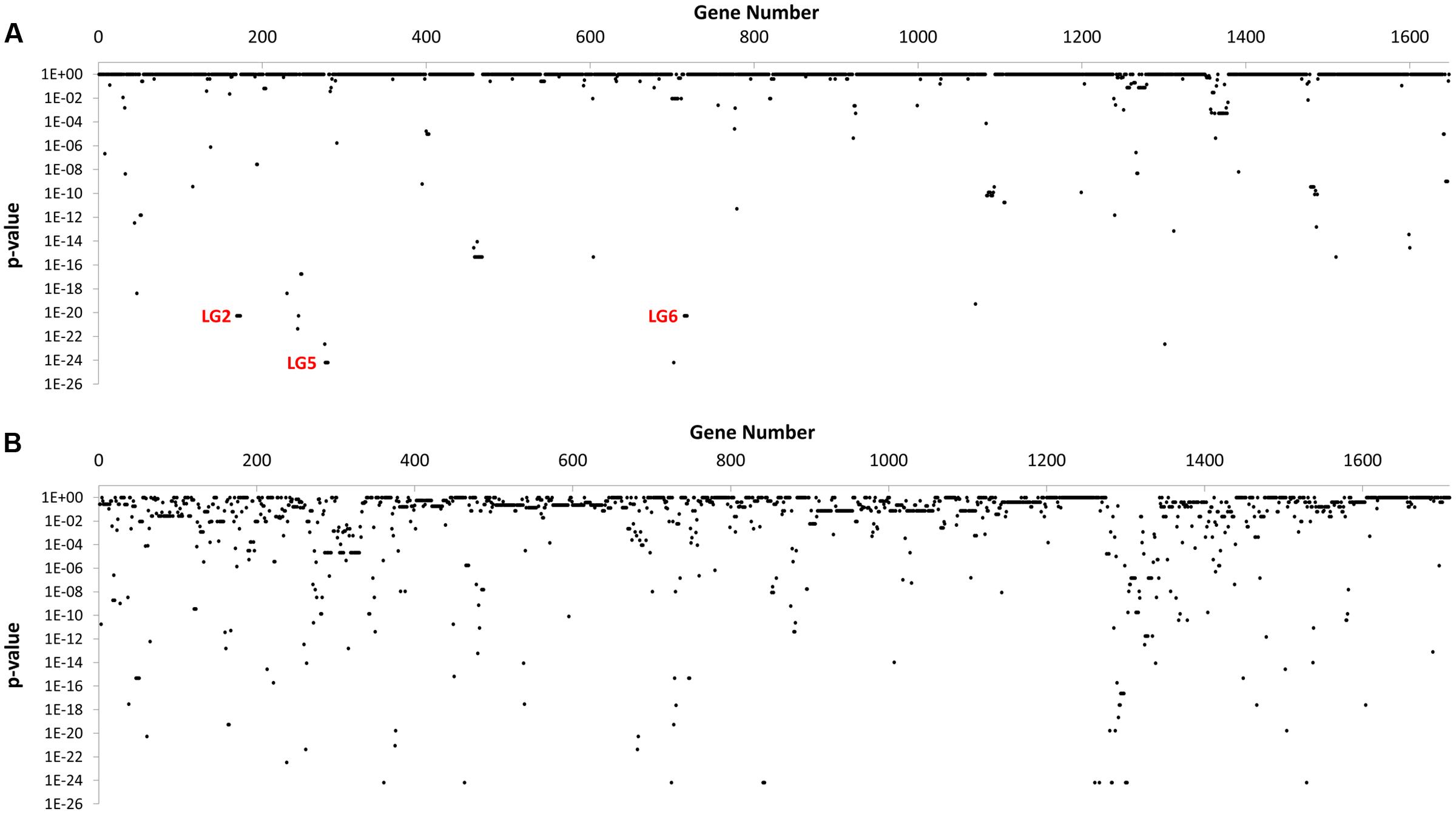

Population structure has been identified as a potential confounding factor in GWAS analyses, in that statistically significant associations may ultimately be due to oversampling of certain subpopulations rather than with the phenotypic trait under investigation (Read and Massey, 2014). Since the focus of the current study was the examination of prevalent C. jejuni subtypes in Canada in the context of population structure, it was necessary to exclude the possibility that the markers we identified represent a biased distribution resulting from oversampling within certain lineages in the population. The large-scale marker validation that we performed using available WGS data included a dataset comprised of genomes largely from the United Kingdom (3,871/4,280; 90%) and Canada (327/4,280; 8%), and an overwhelming majority of isolates were recovered from human clinical sources (3,559/4,280; 83%), while those from animal (626/4,280; 15%) and environmental (95/4,280; 2%) sources comprised the remainder. A total of 539 CGF subtypes were identified by in silico CGF, however, 279 subtypes were novel and had not been previously observed in the C3GFdb and were omitted from the analysis since their epidemiological characteristics could not be determined. Of the remaining 260 CGF subtypes, 38 CGF subtypes (160 genomes) were identified as NCA, nine CGF subtypes (99 genomes) were identified as UN, and 213 CGF subtypes (3,742 isolates) were identified as CA. Despite the influx of genetically and geographically diverse isolates introduced as part of the expanded dataset, a majority (n = 25) of the markers in the original GWAS analysis continued to show statistical significance with CA subtypes; on average these markers were present in 73% of CA isolates compared to only 36% of NCA isolates (Figure 3). Moreover, results of our combinatorial marker analysis show that as few as four markers could be used in combination to detect up to 90% of CA isolates in the validation dataset, with a modest carriage rate of 21% among NCA isolates. These findings suggest that the robust signal detected in the original GWAS analysis stems from genes that appear to have diagnostic value for the identification of C. jejuni subtypes with an increased association with campylobacteriosis.

FIGURE 3. In silico validation of putative diagnostic marker genes against expanded CA and NCA cohorts. The putative diagnostic genes identified by GWAS using the original set of 166 genomes were tested for statistical significance with expanded CA (blue bars; n = 3,742) and NCA (green bars; n = 160) cohorts comprised of additional genomes sequenced in house and from public repositories. Despite the influx of genetically and geographically diverse isolates introduced as part of the expanded dataset, a majority (n = 25) of the markers continued to show statistically significant signal with CA subtypes. This suggests that the robust signal detected in the original GWAS analysis stems from genes that appear to have diagnostic value for the identification of C. jejuni subtypes with an increased association with campylobacteriosis. ∗Denotes genes that showed statistically significant signal with CA subtypes.

Conclusion

A major challenge in the prevention and control of campylobacteriosis is our current inability to identify strains of C. jejuni that pose the greatest risk to human health. Addressing this issue would pave the way to better tracking of high-risk strains, leading to a better understanding of their distribution in the food chain and providing critical information towards the development of targeted mitigation strategies to reduce human exposure.

The goal of this study was to identify markers associated with C. jejuni lineages known to cause disease in humans and that have a high prevalence in Canada. The genomes of 166 isolates representing 34 highly prevalent C. jejuni subtypes were sequenced and a GWAS was performed to identify 28 genes significantly associated with highly prevalent and clinically-related C. jejuni subtypes. While some putative gene markers identified as part of this study have previously been associated with important aspects of C. jejuni biology including iron acquisition and vitamin B5 biosynthesis, others represent putative proteins associated with catalysis and transport, which may play roles in processes important for infection and warrant further investigation.

Although these genes were identified within a dataset of Canadian origin, 25 of them continued to display strong statistical significance when validated against a more genetically and geographically diverse dataset. This suggests that they may represent robust markers for clinically-associated C. jejuni subtypes, paving the way for future development of molecular assays for rapid identification of C. jejuni strains that pose an increased risk to human health.

Author Contributions

CB participated in all aspects of laboratory and in silico analyses and drafted the manuscript; AW and SM participated in data analysis and drafting of the manuscript; PK, DB, and BH assisted with various aspects of bioinformatics analyses; VG, WA, JT, DI, and ET contributed to study design and writing the manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this work was provided by the Alberta Livestock and Meat Association (ALMA) through project 2012F034R, Alberta Innovates Bio Solutions through project BIOFS-12-026, and through the Government of Canada’s Genomics Research and Development Initiative.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to acknowledge Canada’s Michael Smith Genome Sciences Centre, BC, Canada for assistance with sequencing of C. jejuni isolates. This work would not have been possible without the collaboration of the many contributors to the Canadian Campylobacter Comparative Genomic Fingerprinting database (C3GFdb).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.01224/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

References

Aickin, M., and Gensler, H. (1996). Adjusting for multiple testing when reporting research results: the Bonferroni vs Holm methods. Am. J. Public Health 86, 726–728. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.86.5.726

Alam, M. T., Petit, R. A., Crispell, E. K., Thornton, T. A., Conneely, K. N., Jiang, Y., et al. (2014). Dissecting vancomycin-intermediate resistance in Staphylococcus aureus using genome-wide association. Genome Biol. Evol. 6, 1174–1185. doi: 10.1093/gbe/evu092

Bankevich, A., Nurk, S., Antipov, D., Gurevich, A. A., Dvorkin, M., Kulikov, A. S., et al. (2012). SPAdes: a new genome assembly algorithm and its applications to single-cell sequencing. J. Comput. Biol. 19, 455–477. doi: 10.1089/cmb.2012.0021

Camacho, C., Coulouris, G., Avagyan, V., Ma, N., Papadopoulos, J., Bealer, K., et al. (2009). BLAST+: architecture and applications. BMC Bioinformatics 10:421. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-10-421

Chewapreecha, C., Marttinen, P., Croucher, N. J., Salter, S. J., Harris, S. R., Mather, A. E., et al. (2014). Comprehensive identification of single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with beta-lactam resistance within pneumococcal mosaic genes. PLoS Genet. 10:e1004547. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1004547

Clark, C. G., Berry, C., Walker, M., Petkau, A., Barker, D. O. R., Guan, C., et al. (2016). Genomic insights from whole genome sequencing of four clonal outbreak Campylobacter jejuni assessed within the global C. jejuni population. BMC Genomics 17:990. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3340-8

Clark, C. G., Taboada, E., Grant, C. C. R., Blakeston, C., Pollari, F., Marshall, B., et al. (2012). Comparison of molecular typing methods useful for detecting clusters of Campylobacter jejuni and C. coli isolates through routine surveillance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 798–809. doi: 10.1128/JCM.05733-11

Dasti, J. I., Tareen, A. M., Lugert, R., Zautner, A. E., and Gross, U. (2010). Campylobacter jejuni: a brief overview on pathogenicity-associated factors and disease-mediating mechanisms. Int. J. Med. Microbiol. 300, 205–211. doi: 10.1016/j.ijmm.2009.07.002

Duong, T., and Konkel, M. E. (2009). Comparative studies of Campylobacter jejuni genomic diversity reveal the importance of core and dispensable genes in the biology of this enigmatic food-borne pathogen. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 20, 158–165. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2009.03.004

Farhat, M. R., Shapiro, B. J., Kieser, K. J., Sultana, R., Jacobson, K. R., Victor, T. C., et al. (2013). Genomic analysis identifies targets of convergent positive selection in drug-resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Nat. Genet. 45, 1183–1189. doi: 10.1038/ng.2747

Galanis, E. (2007). Campylobacter and bacterial gastroenteritis. CMAJ 177, 570–571. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.070660

Gundogdu, O., Bentley, S. D., Holden, M. T., Parkhill, J., Dorrell, N., and Wren, B. W. (2007). Re-annotation and re-analysis of the Campylobacter jejuni NCTC11168 genome sequence. BMC Genomics 8:162. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-162

Gurevich, A., Saveliev, V., Vyahhi, N., and Tesler, G. (2013). QUAST: quality assessment tool for genome assemblies. Bioinformatics 29, 1072–1075. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btt086

Havelaar, A. H., van Pelt, W., Ang, C. W., Wagenaar, J. A., van Putten, J. P. M., Gross, U., et al. (2009). Immunity to Campylobacter: its role in risk assessment and epidemiology. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 35, 1–22. doi: 10.1080/10408410802636017

Kim, E.-J., Sabra, W., and Zeng, A.-P. (2003). Iron deficiency leads to inhibition of oxygen transfer and enhanced formation of virulence factors in cultures of Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Microbiology 149, 2627–2634. doi: 10.1099/mic.0.26276-0

Koenraad, P. M. F. J., Rombouts, F. M., and Notermans, S. H. W. (1997). Epidemiological aspects of thermophilic Campylobacter in water-related environments: a review. Water Environ. Res. 69, 52–63. doi: 10.2175/106143097X125182

Kruczkiewicz, P., Mutschall, S., Barker, D., Thomas, J. E., Domselaar, G. V. H., Gannon, V. P., et al. (2013). “MIST: a tool for rapid in silico generation of molecular data from bacterial genome sequences,” in Proceedings of Bioinformatics 2013: 4th International Conference on Bioinformatics Models, Methods and Algorithms (New York, NY: Springer), 316–323.

Lastovica, A. J., On, S. L., and Zhang, L. (2014). “The family Campylobacteraceae,” in The Prokaryotes, eds E. Rosenberg, E. F. DeLong, S. Lory, E. Stackebrandt, and F. Thompson (Berlin: Springer), 307–335.

Méric, G., Yahara, K., Mageiros, L., Pascoe, B., Maiden, M. C. J., Jolley, K. A., et al. (2014). A reference pan-genome approach to comparative bacterial genomics: identification of novel epidemiological markers in pathogenic Campylobacter. PLoS ONE 9:e92798. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0092798

Moreno-Hagelsieb, G., and Latimer, K. (2008). Choosing BLAST options for better detection of orthologs as reciprocal best hits. Bioinformatics 24, 319–324. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btm585

Muley, V. Y., and Acharya, V. (2013). “Chromosomal proximity of genes as an indicator of functional linkage,” in Genome-Wide Prediction and Analysis of Protein-Protein Functional Linkages in Bacteria, eds V. Y. Muley and V. Acharya (New York, NY: Springer), 33–42. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4614-4705-4_4

Nachamkin, I. (2002). Chronic effects of Campylobacter infection. Microbes Infect. 4, 399–403. doi: 10.1016/S1286-4579(02)01553-8

Nachamkin, I., Allos, B. M., and Ho, T. (1998). Campylobacter species and Guillain-Barré syndrome. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 11, 555–567.

Naikare, H., Butcher, J., Flint, A., Xu, J., Raymond, K. N., and Stintzi, A. (2013). Campylobacter jejuni ferric–enterobactin receptor CfrA is TonB3 dependent and mediates iron acquisition from structurally different catechol siderophores. Metallomics 5, 988–996. doi: 10.1039/C3MT20254B

Naikare, H., Palyada, K., Panciera, R., Marlow, D., and Stintzi, A. (2006). Major role for FeoB in Campylobacter jejuni ferrous iron acquisition, gut colonization, and intracellular survival. Infect. Immun. 74, 5433–5444. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00052-06

Palyada, K., Threadgill, D., and Stintzi, A. (2004). Iron acquisition and regulation in Campylobacter jejuni. J. Bacteriol. 186, 4714–4729. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.14.4714-4729.2004

Parkhill, J., Wren, B. W., Mungall, K., Ketley, J. M., Churcher, C., Basham, D., et al. (2000). The genome sequence of the food-borne pathogen Campylobacter jejuni reveals hypervariable sequences. Nature 403, 665–668. doi: 10.1038/35001088

Pintar, K. D. M., Thomas, K. M., Christidis, T., Otten, A., Nesbitt, A., Marshall, B., et al. (2016). A Comparative exposure assessment of Campylobacter in Ontario, Canada. Risk Anal. 37, 677–715. doi: 10.1111/risa.12653

Read, T. D., and Massey, R. C. (2014). Characterizing the genetic basis of bacterial phenotypes using genome-wide association studies: a new direction for bacteriology. Genome Med. 6:109. doi: 10.1186/s13073-014-0109-z

Seemann, T. (2014). Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 30, 2068–2069. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btu153

Sheppard, S. K., Didelot, X., Méric, G., Torralbo, A., Jolley, K. A., Kelly, D. J., et al. (2013). Genome-wide association study identifies vitamin B5 biosynthesis as a host specificity factor in Campylobacter. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110, 11923–11927. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1305559110

Silva, J., Leite, D., Fernandes, M., Mena, C., Gibbs, P. A., and Teixeira, P. (2011). Campylobacter spp. as a foodborne pathogen: a review. Front. Microbiol. 2:200. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2011.00200

Suzuki, H., and Yamamoto, S. (2009). Campylobacter contamination in retail poultry meats and by-products in the world: a literature survey. J. Vet. Med. Sci. 71, 255–261. doi: 10.1292/jvms.71.255

Taboada, E. N., Ross, S. L., Mutschall, S. K., Mackinnon, J. M., Roberts, M. J., Buchanan, C. J., et al. (2012). Development and validation of a comparative genomic fingerprinting method for high-resolution genotyping of Campylobacter jejuni. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 788–797. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00669-11

Taboada, E. N., van Belkum, A., Yuki, N., Acedillo, R. R., Godschalk, P. C., Koga, M., et al. (2007). Comparative genomic analysis of Campylobacter jejuni associated with Guillain-Barré and Miller Fisher syndromes: neuropathogenic and enteritis-associated isolates can share high levels of genomic similarity. BMC Genomics 8:359. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-8-359

Thépault, A., Méric, G., Rivoal, K., Pascoe, B., Mageiros, L., Touzain, F., et al. (2017). Genome-wide identification of host-segregating epidemiological markers for source attribution in Campylobacter jejuni. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 83:e3085-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.03085-16

Thomas, M. K., Murray, R., Flockhart, L., Pintar, K., Pollari, F., Fazil, A., et al. (2013). Estimates of the burden of foodborne illness in Canada for 30 specified pathogens and unspecified agents, circa 2006. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 10, 639–648. doi: 10.1089/fpd.2012.1389

Ward, N., and Moreno-Hagelsieb, G. (2014). Quickly finding orthologs as reciprocal best hits with BLAT, LAST, and UBLAST: How much do we miss? PLoS ONE 9:e101850. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0101850

Whiley, H., van den Akker, B., Giglio, S., and Bentham, R. (2013). The role of environmental reservoirs in human campylobacteriosis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 10, 5886–5907. doi: 10.3390/ijerph10115886

Williams, A., and Oyarzabal, O. A. (2012). Prevalence of Campylobacter spp. in skinless, boneless retail broiler meat from 2005 through 2011 in Alabama, USA. BMC Microbiol. 12:184. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-184

Keywords: Campylobacter jejuni, genome sequence, genome-wide association study, clinical association, molecular marker discovery, linkage analysis, molecular risk assessment

Citation: Buchanan CJ, Webb AL, Mutschall SK, Kruczkiewicz P, Barker DOR, Hetman BM, Gannon VPJ, Abbott DW, Thomas JE, Inglis GD and Taboada EN (2017) A Genome-Wide Association Study to Identify Diagnostic Markers for Human Pathogenic Campylobacter jejuni Strains. Front. Microbiol. 8:1224. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.01224

Received: 27 January 2017; Accepted: 16 June 2017;

Published: 30 June 2017.

Edited by:

Sandra Torriani, University of Verona, ItalyReviewed by:

Heriberto Fernandez, Austral University of Chile, ChileJinshui Zheng, Huazhong Agricultural University, China

Beatrix Stessl, Veterinärmedizinische Universität Wien, Austria

Copyright © 2017 Buchanan, Webb, Mutschall, Kruczkiewicz, Barker, Hetman, Gannon, Abbott, Thomas, Inglis and Taboada. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Eduardo N. Taboada, ZWR1YXJkby50YWJvYWRhQGNhbmFkYS5jYQ==

†Present address: Cody J. Buchanan, Canadian Food Inspection Agency, Canadian Science Centre for Human and Animal Health, Winnipeg, MB, Canada

Cody J. Buchanan

Cody J. Buchanan Andrew L. Webb1

Andrew L. Webb1 Steven K. Mutschall

Steven K. Mutschall Peter Kruczkiewicz

Peter Kruczkiewicz Dillon O. R. Barker

Dillon O. R. Barker Benjamin M. Hetman

Benjamin M. Hetman Victor P. J. Gannon

Victor P. J. Gannon G. Douglas Inglis

G. Douglas Inglis Eduardo N. Taboada

Eduardo N. Taboada