- 1Key Laboratory of Molecular Animal Nutrition of Ministry of Education, Institute of Feed Science, College of Animal Sciences, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

- 2Department of Cardiology, Zhejiang Provincial People’s Hospital, Hangzhou, China

- 3Department of Biochemistry, School of Medicine, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

Probiotics are increasingly applied in popularity in both humans and animals. Decades of research has revealed their beneficial effects, including the immune modulation in intestinal pathogens inhibition. Autophagy—a cellular process that involves the delivery of cytoplasmic proteins and organelles to the lysosome for degradation and recirculation—is essential to protect cells against bacterial pathogens. However, the mechanism of probiotics-mediated autophagy and its role in the elimination of pathogens are still unknown. Here, we evaluated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 (Ba)-induced autophagy and its antibacterial activity against Escherichia coli (E. coli) in murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 cells. Western blotting and confocal laser scanning analysis showed that Ba activated autophagy in a dose- and time-dependent manner. Ba-induced autophagy was found to play a role in the elimination of intracellular bacteria when RAW264.7 cells were challenged with E. coli. Ba induced autophagy by increasing the expression of Beclin1 and Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex, but not the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway. Moreover, Ba pretreatment attenuated the activation of JNK in RAW264.7 cells during E. coli infection, further indicating a protective role for probiotics via modulating macrophage immunity. The above findings highlight a novel mechanism underlying the antibacterial activity of probiotics. This study enriches the current knowledge on probiotics-mediated autophagy, and provides a new perspective on the prevention of bacterial infection in intestine, which further the application of probiotics in food products.

Introduction

The gut is the largest immune organ in the body, where harbors a diverse array of organisms and the environment is quite complex (Ouwehand et al., 2005). Various factors such as foodborne pathogens may disturb the intestinal balance, leading to infectious diseases and diarrhea, which eventually influence the overall health (Giacomin et al., 2016). In recent years, nutritional intervention has become a new trend to maintain intestinal homeostasis. In this context, there has been an explosion of consumer interest in probiotics, and the market is increasing annually (Neef and Sanz, 2013). Probiotics are live microorganisms that, when administered in adequate amounts, confer a health benefit on the host (Hill et al., 2014). The benefits of probiotics include rebalancing the distribution of intestinal microbiota (Neef and Sanz, 2013), management of metabolic syndromes (Musso et al., 2010), and prevention of gastrointestinal diseases (Prakash et al., 2011; Whelan and Quigley, 2013). Studies have also shown that probiotics, such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium, Bacillus, and Enterococcus, significantly inhibited pathogen infection in vitro and in vivo (Lebeer et al., 2008; Candela et al., 2008; Zhou et al., 2015; Safari et al., 2016). One possible mechanism of action is regulation of the immune response. Recent studies found that probiotics altered the inflammatory response by stimulating cytokine production (Ranadheera et al., 2014; Djaldetti and Bessler, 2017). However, further study of probiotics-mediated molecular mechanisms is still needed.

Autophagy is a highly conserved process in which cytoplasmic targets are sequestered in double membraned autophagosomes and subsequently delivered to lysosomes for degradation (Mizushima, 2011). Acting as an innate defense pathway in response to a variety of stimuli, autophagy is crucial for cytoplasmic recycling, fundamental homeostatis and cell survival (Nakagawa et al., 2004; Levine et al., 2011). Autophagy is also an essential component of the immune defense against bacterial pathogens such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, Salmonella enterica, and Escherichia coli (Kirkegaard et al., 2004; Chargui et al., 2012; Bento et al., 2015). Thus, triggering autophagy in an appropriate manner is essential for cell survival during pathogens infection (Wang et al., 2013; Rekha et al., 2015).

The induction of autophagy involves numerous proteins and multiple signaling pathways. More than 30 members of the autophagy-related genes (Atg) family, such as Beclin1 (homolog of Atg6), and Atg complexes are needed for autophagosome formation (Yang and Klionsky, 2010). Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3, a mammalian homolog of yeast Atg8), a vital component of the elongation step, is regarded as the autophagy marker (Mizushima, 2011). p62 (also known as SQSTM1), a common autophagy substrate and a marker of autophagic flux, is selectively incorporated into autophagosomes and efficiently degraded by autophagy (Xu et al., 2015). Moreover, several signaling pathways, including AKT (alpha serine/threonine kinase)/mTOR (mammalian target of rapamycin), AMPK [Adenosine 5′-monophosphate (AMP)-activated protein kinase], and MAPK (mitogen-activated protein kinase), modulate autophagy at different autophagosome formative stages (Yang and Klionsky, 2010).

Recent studies have suggested that probiotics can mildly regulate macrophages to enhance the immune response to foreign invaders. Macrophage, an important effector during pathogen invasion (Naito, 2008), can utilize autophagy to defend against infection (Martinez et al., 2013). Pathogens that are passively taken up by macrophages and stored in the cytosol or phagosome are eventually degraded by the autophagy pathway. A previous study found that probiotic mixture VSL#3 can induce a mixed inflammatory phenotype in macrophages (Isidro et al., 2014); Lactobacillus acidophilus and Bacillus clausii are potent activators of innate immune responses in murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 cells (Pradhan et al., 2016). The immunostimulatory activity of probiotics depends on the interaction between microorganisms-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs) and toll-like receptors (TLRs) (Lebeer et al., 2010). This interaction is also involved in triggering autophagy in macrophages. Thus, probiotics may mediate antibacterial activity in macrophages through mechanisms that activate autophagy. Despite the evidence, only a few studies have explored the regulation of autophagy by probiotics (Kim et al., 2010; Wu et al., 2013; Lin et al., 2014), and its role in the elimination of pathogens is still unknown.

In the present study, we examined the relationship between probiotics and autophagy and its role in the elimination of pathogens. We found that probiotic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 (Ba) induced autophagy in RAW264.7 cells by upregulating the expression of Beclin1 and Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex. This mechanism played a key role in protecting macrophages against E. coli infection.

Materials and Methods

Reagents

Antibody LC3 was obtained from Sigma–Aldrich (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA). phospho-ERK1/2 and anti-ERK1 were from BD Biosciences (San Jose, CA, USA). Antibodies including SQSTM/p62, phospho-AKT, AKT, phospho-mTOR, mTOR, Beclin1, phospho-JNK, and phospho-p38 were obtained from Cell Signal Technologies (Danvers, Massachusetts, USA). SAPK/JNK, p38, β-actin, HRP-conjugated anti-mouse IgG, and HRP-conjugate anti-rabbit IgG were from Beyotime (Shanghai, China). Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated secondary antibody to rabbit IgG was purchased from Life Technologies (Gaithersburg, MD, USA). Autophagy inhibitors chloroquine, 3-MA, and the activator rapamycin were purchased from Sigma–Aldrich (Sigma, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Cell Culture and Bacteria Preparation

Murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 were purchased from American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Rockville, MD) and maintained in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Media (DMEM, Hyclone), supplemented with 10% fetal calf serum (FBS, Australian origin, Gibco), and 1% antibiotics (100 U/ml of penicillin G and 100 mg/ml of streptomycin) in a humidified atmosphere at 37°C. The probiotic Ba, was isolated from soil and preserved at China Center for Type Culture Collection (CCTCC, No: M2012280). Ba was grown in Luria-Bcrtani (LB) medium overnight at 37°C, harvested by centrifugation (5000 rpm, 10 min), washed 3 times and suspended in PBS at different optical densities at 600 nm (0.33 OD = 1 × 108 cfu/ml). Then, bacteria were heated at 100°C for 30 min (Ji et al., 2013). The heat-killed bacteria precipitation was collected after centrifugation, and resuspended in DMEM for cell treatments. The Escherichia coli (E. coli) strain (C83549 (O149:k91, K88ac)) was obtained from China Institute of Veterinary Drug Control. E. coli expressing RFP (RFP-E. coli) was constructed in our lab. Both of them were grown in LB medium overnight at 37°C, and then incubated in fresh medium (1:100) for another 3 h for all experiments.

Cell Cytotoxicity Assay

Cell viability was measured using cell counting kit 8 (CCK-8, Beyotime, China) (Ma et al., 2010). Briefly, monolayers of RAW264.7 cells were cultured in 96-well plates overnight and then pretreated with Ba at different concentrations (ranging from 106 to 109cfu/ml) for 12 h. Followed by removal of the cultured medium, 10 μL CCK-8 assay solution was added to every cell well and further incubated for 1 h. Subsequently, the OD value was measured using SpectraMax M5 at OD450 and the percentage of living cells was calculated as previously described (Mosmann, 1983). Lactate dehydrogenase (LDH) release from damaged cells was quantified using CytoTox96 kit (Roche Diagnostics, Mannheim, Germany) after cells co-cultured with 107 or 108 cfu/ml Ba for 12 h.

Western blotting

Cells were lysed in RIPA buffer (Beyotime) on ice for 30 min. An equal amount of proteins (20 μg) from each sample were loaded on 8, 12, or 15% SDS-polyacrylamide gels and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride (PVDF) membranes (Roche). After blocking with no protein blocking solution (SangonBiotech) at room temperature, the membranes were incubated with primary antibody overnight at 4°C. Following incubated with secondary antibody for 1 h, the immunoreactive bands were visualized with an ECL detection system. Densitometric quantification of band intensities was determined using Image J software.

Immunofluorescence Staining Analysis

RAW264.7 cells were seeded on coverslips (Nest) in 12-well plates for overnight culture, and then treated with 108 cfu/ml Ba or 2 μM rapamycin for 6 h. For infection assay, pretreated cells were infected with RFP-E. coli for 1 h in antibiotic free DMEM. Then, cells were fixed with cold methanol for 5 min, blocked with 2.5% BSA for 2 h in room temperature, and incubated with anti-LC3 antibody overnight at 4°C. After incubated with Alexa Fluor 488-conjugated antibody for 1 h, nuclei were labeled with DAPI for 10 min. Samples were mounted by confocal microscopy using the Olympus Laser Scanning Microscope (Olympus BX61W1-FV1000, Tokyo, Japan).

Real-time PCR for Expression Analysis

Total RNA was isolated from treated RAW264.7 cells with RNAiso plus (Takara). cDNA was synthesized with PrimeScript II 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was performed using SYBR PremixExTaqII (Takara) and StepOnePlus real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems). All samples were runned in duplicate. The gene expression levels were normalized to β-actin using the comparative Ct method (Schmittgen et al., 2000). The primers were as follows:

Atg5: forward, AGAAGATGTTAGTGAGATATGG

reverse, ATGGACAGTGTAGAAGGT;

Atg7: forward, AGCCCACAGATGGAGTAGCAGTTT

reverse, TCCCATGCCTCCTTTCTGGTTCTT

Atg12: forward, CCAAGGACTCATTGACTTC

reverse, GCAAAGGACTGATTCACATA;

Atg16: forward, TGTCTTCAGCCCTGATGGCAGTTA

reverse, AGCACAGCTTTGCATCCTTTGTCC.

Antibacterial Assay

RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with Ba for 6 h, and infected with E. coli at a multiplicity of infection (MOI) of 30 for 1 h in antibiotic free medium. The antibacterial activity was assessed as previously described (Boudeau et al., 1999; Mao et al., 2015). In detail, cells were washed three times with PBS post infection, and cultured in medium containing gentamicin (100 μg/ml) for 1 h to eliminate extracellular bacteria. For phagocytosis analysis, cells were then lysed immediately in PBS with 1% Triton X-100. For bactericidal analysis, cells were lysed after a further incubation for 7 h or 19 h in medium containing 10 μg/ml gentamicin. The number of bacteria released from cells was detected by plating serial dilutions of the cell lysates on LB agar plates. Meanwhile, a portion of lysates was used to measure the concentration of cell protein. Bactericidal activity was analyzed by the remaining E. coli at each time point/cell protein concentration. All infections were performed in duplicate, and each experiment was repeated three times.

Statistical Analysis

Data were expressed as means ± standard deviation. Differences were determined by two-tailed student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA using SPSS 20.0 statistical software (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). P-values of <0.05 were considered statistically significant. All statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 5.0 software.

Results

Cytotoxicity Analysis of Ba on RAW264.7 Cells

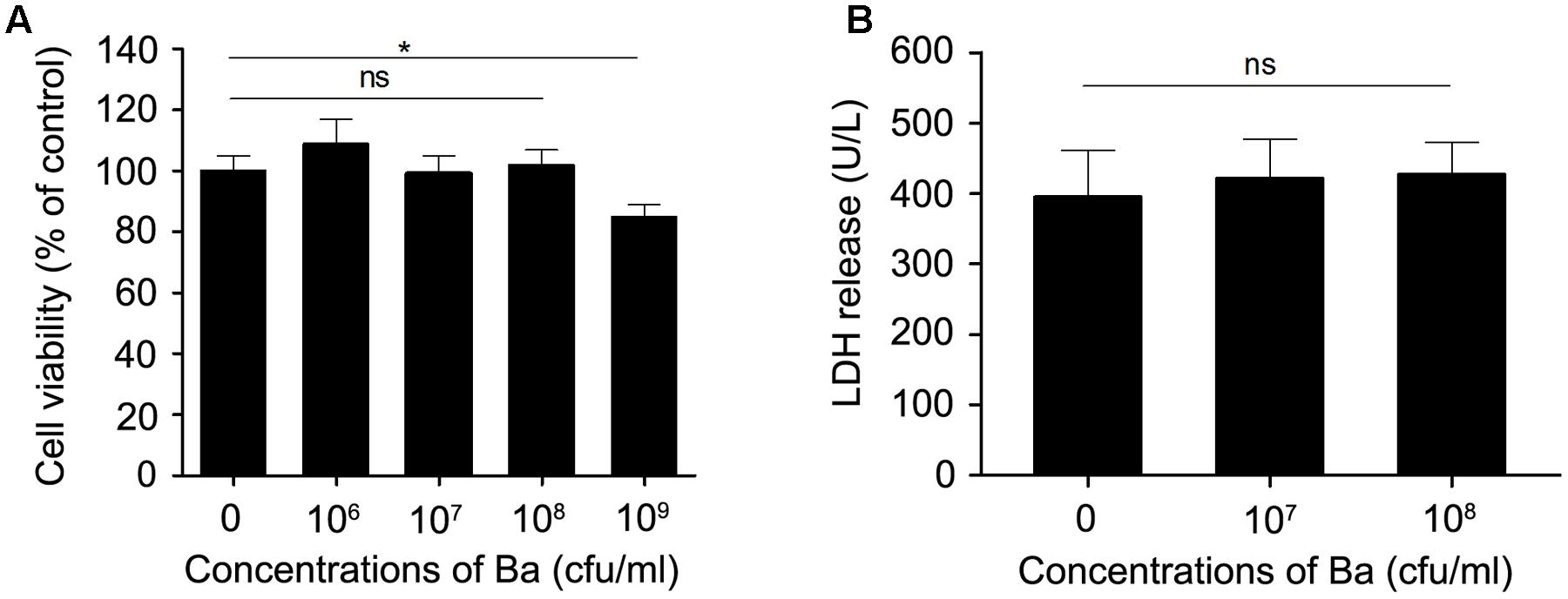

To evaluate the cytotoxicity of probiotics on macrophages, murine macrophage cell line RAW264.7 cells were treated with probiotic Ba. Cell viability was determined using the CCK-8 assay. No obvious decrease of viability was observed when cells were incubated with Ba at a range of concentrations (from 106 to 108 cfu/ml) (Figure 1A). Therefore, 107 (97.5 ± 2.67 % viable cells) and 108 cfu/ml (99.9 ± 2.47% viable cells) were used in subsequent experiments. To evaluate the effect of Ba on cell damage, we measured LDH activity in the cell culture supernatant. There was no significant difference in LDH activity following 12 h of treatment with Ba when compared to untreated cells (p > 0.05) (Figure 1B).

FIGURE 1. Cytotoxity assay of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 (Ba) in RAW264.7 cells. (A) RAW264.7 cells were exposed to Ba at different concentrations (106, 107, 108, 109 cfu/ml) for 12 h. Cell viability was determined by CCK-8 assay. (B) Cell damage was determined by measuring the release of LDH. RAW264.7 cells were incubated with Ba (108 and 109 cfu/ml) for 12 h, and LDH release in the supernatant was quantified using the CytoTox96 kit. Data are representative of three individual experiments. ∗p < 0.05 (t-test). ns indicates no significance (p > 0.05).

Ba Stimulates Autophagy in RAW264.7 Cells

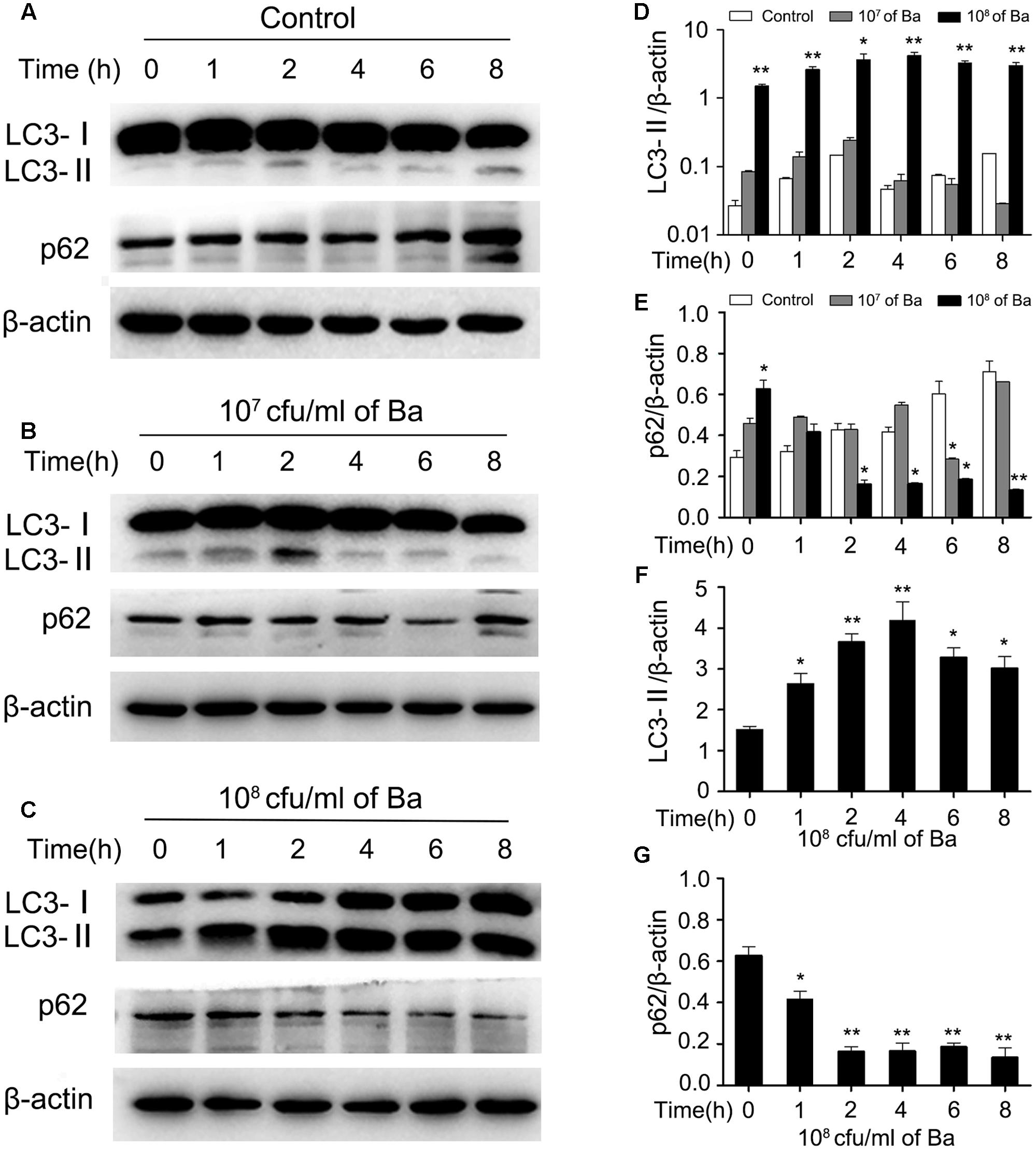

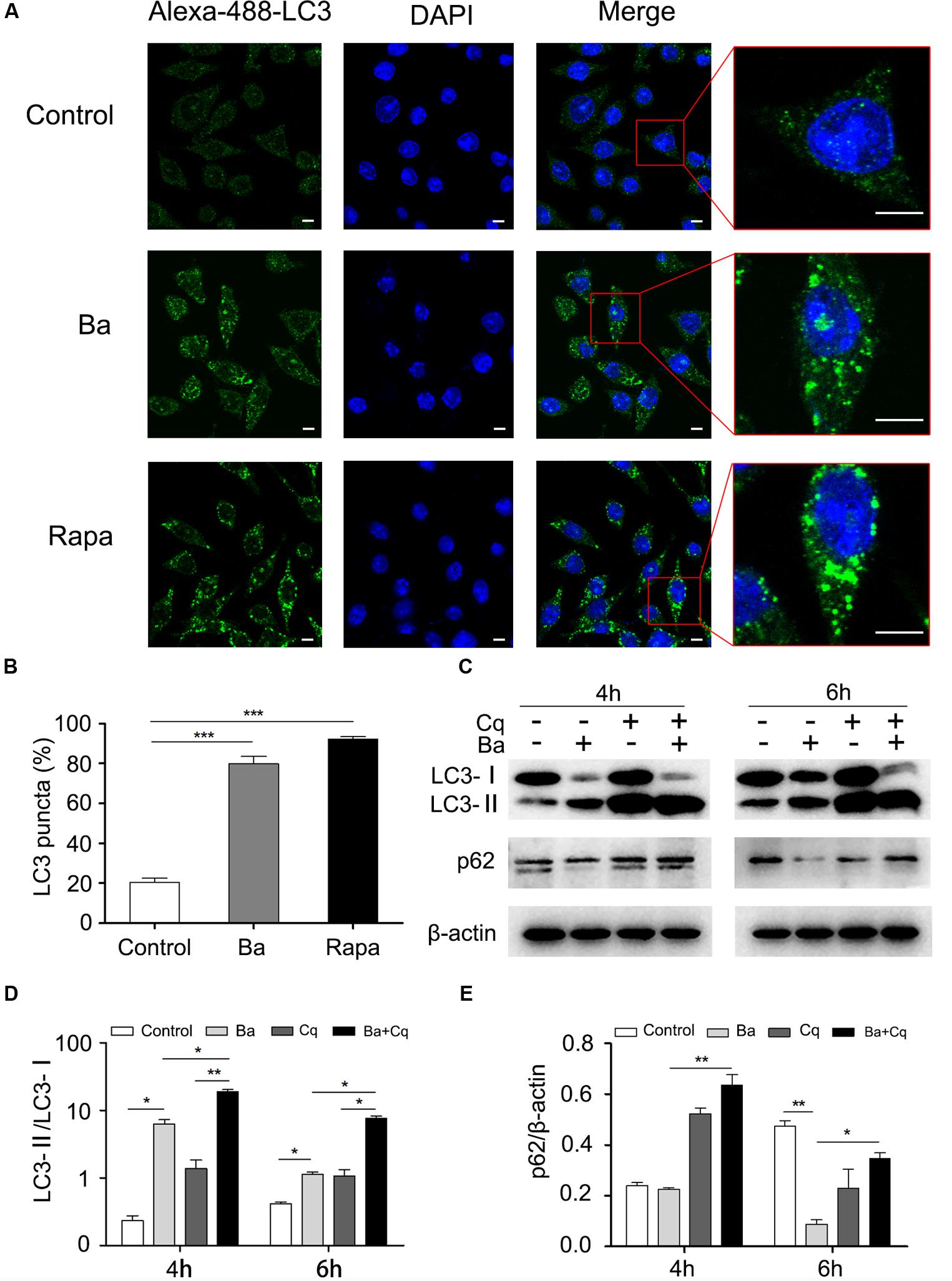

To determine whether Ba induces autophagy, RAW264.7 cells were incubated with Ba for different lengths of time (0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 h). Protein expression of Microtubule-associated protein 1 light chain 3 (LC3), an autophagy marker, was examined by western blotting (Klionsky et al., 2012). No significant changes in LC3-II expression were observed between untreated cells and cells treated with a low concentration (107 cfu/ml) of Ba for 8 h (Figures 2A,B,D). However, LC3-II was significantly higher in cells treated with a high dose (108 cfu/ml) of Ba compared to untreated cells (p < 0.01) (Figures 2A,C,D). Treatment with 108 cfu/ml Ba upregulated intracellular LC3-II at 2 h (p < 0.05), peaked at 4 h (p < 0.01), and maintained high levels persistently up to 8 h (Figures 2C,F). In addition to LC3-II, we examined the autophagic flux by detecting degradation of p62, a common autophagy substrate. p62 expression significantly decreased from 2 h to 8 h (p < 0.05) in 108 cfu/ml Ba-treated cells, but not in cells treated with 107 cfu/ml Ba and untreated cells (Figures 2E,G). Autophagy induction was also confirmed with confocal laser scanning analysis of LC3 cells. As shown in Figures 3A,B, cells treated with 108 cfu/ ml Ba or 2 μM autophagy activator rapamycin for 6 h significantly increased LC3 puncta (p < 0.001).

FIGURE 2. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 (Ba) increases LC3-II and degrades p62 in a dose- and time- dependent manner. (A) Control: RAW264.7 cells were incubated from 0 to 8 h without any treatment, and were harvested and analyzed by western blotting using anti-LC3, anti-p62, or anti-β-actin antibody. (B) 107 cfu/ml of Ba: Cells were treated with Ba at the concentration of 107cfu/ml from 0 to 8 h. (C) 108 cfu/ml of Ba: Cells were treated with Ba at the concentration of 108cfu/ml from 0 to 8 h. (D,E) The ratio of LC3-II or P62 to β-actin were analyzed by Image J. Significance was determined by comparing to control cells. (F,G) The ratio of LC3-II or p62 to β-actin in 108 cfu/ml of Ba group were analyzed by Image J. Significance was determined by comparing to the value at 0 h (t-test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). Data are representative of three individual experiments with similar results.

FIGURE 3. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 (Ba) treatment induces autophagy in RAW264.7 cells (A) RAW264.7 cells were treated as follows. Control: Untreated cells. Ba: Cells were incubated with 108 cfu/ml Ba for 6 h. Rapa: Positive control. Cells were treated with rapamycin (2 μM, 6 h). All cells were then stained using immunofluorescence technique and observed under a confocal microscopy. The scale bar represents 5 μm (B) Statistical analyses of the number of positive cells with > 3 green puncta. Values are from 100 cells per sample (t-test, ∗∗∗p < 0.001). Data are representative of three individual experiments with similar results. (C) Cells were pretreated with Chloroquine (Cq, 50 μM, 3 h) and then incubated with 108 cfu/ml of Ba for 6 h. The levels of LC3 and p62 were identified by western blotting. (D,E) Analyses of LC3-II/LC3-I or p62/β-actin using Image J (one-way ANOVA; Tukey test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). Data are representative of three individual experiments with similar results.

To further examine the effect of Ba on autophagy in macrophages, cells were treated with autophagy inhibitor chloroquine (Cq) prior to Ba treatment. Chloroquine, an agent that impairs lysosomal acidification, can block both the degradation of LC3-II and p62, leading to their accumulation (Tanida et al., 2005). Cells were pretreated with 50 μM Cq for 3 h, and then incubated with 108 cfu/ml Ba for another 4 or 6 h. Treatment with Ba alone enhanced the conversion of LC3-I to LC3-II and the degradation of p62. However, pretreatment with Cq resulted in an increase in the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I and inhibited p62 degradation (Figures 3C–E), confirming the activation of autophagy. Taken together, these findings suggest that Ba stimulates autophagy in macrophages.

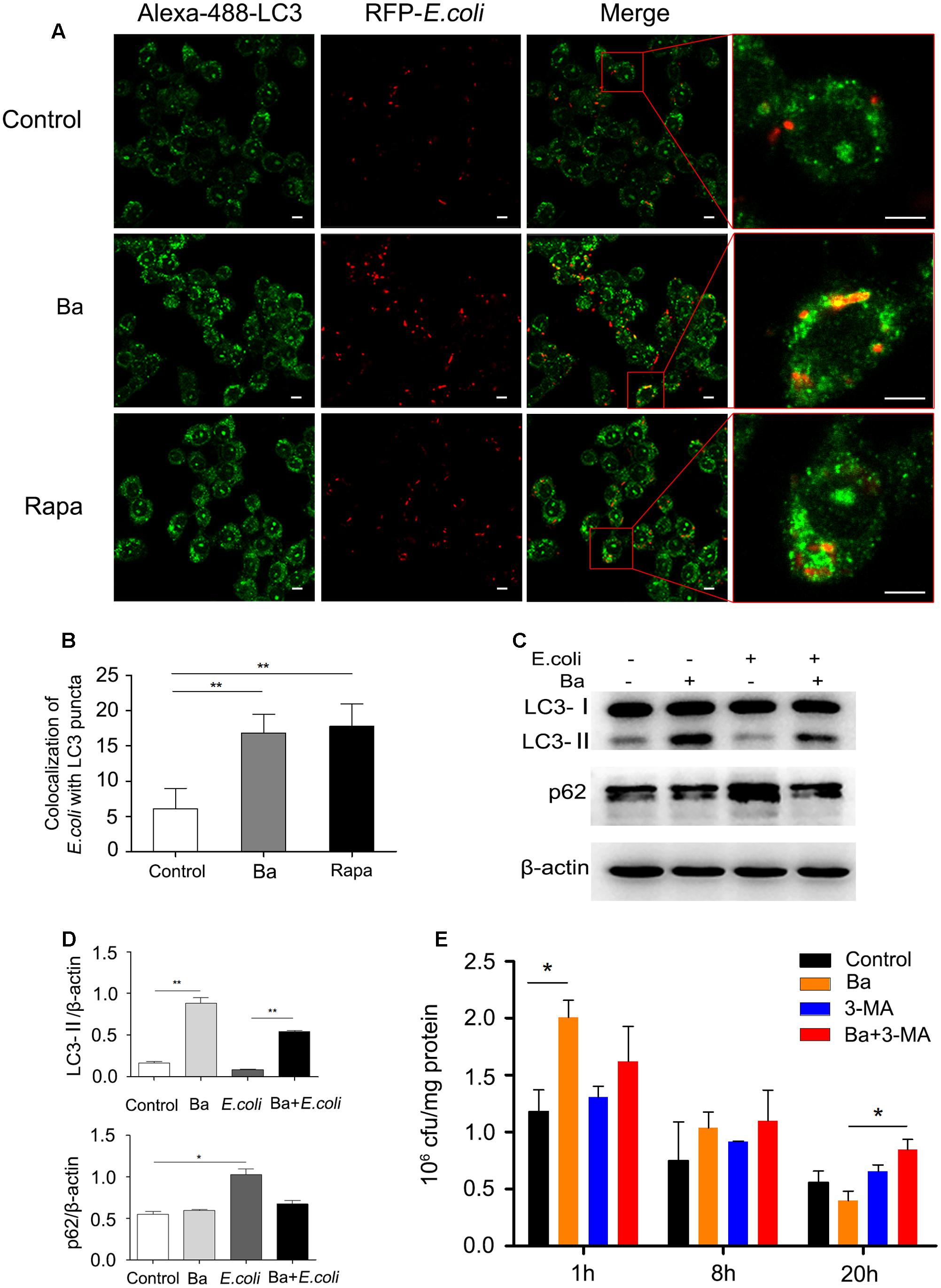

Ba Enhances the Elimination of E. coli in RAW264.7 Cells via Autophagic Pathway

To investigate whether Ba-induced autophagy is involved in antibacterial activity in RAW264.7 cells, we first analyzed the recruitment of LC3 to RFP-E. coli. Cells pretreated with 108 cfu/ml Ba were infected with RFP-E. coli for 1 h. Compared to untreated cells, Ba-treated cells exhibited a markedly increased rate of E. coli colocalization with LC3 puncta (p < 0.01) (Figures 4A,B). Western blotting with total cell protein revealed that the ratio of LC3-II/β-actin was remarkably upregulated in Ba and Ba + E. coli cells, as compared with untreated and E. coli only treated cells (Figures 4C,D).

FIGURE 4. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06-induced autophagy enhances the elimination of E. coli in RAW264.7 cells (A) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with 108 cfu/ml of Ba or 2 μM rapamycin for 6 h, and then infected with RFP-E. coli for 1 h (MOI = 30). After immunofluorescence staining, the colocalization of E. coli with LC3 was observed by confocal microscope. The scale bar represents 5 μm. (B) Statistical analyses of the positive cells with >1 colocalization. Values are from 100 cells per sample (t-test, ∗∗p < 0.01). Data are representative of three individual experiments with similar results. (C) Cells were pretreated with 108 cfu/ml Ba for 6 h, and then infected with E. coli (MOI = 30, 1 h). LC3 and p62 protein expression was determined using western blotting. (D) Analyses of the ratio of LC3-II or p62 to β-actin using Image J (one-way ANOVA; Tukey test, ∗p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01). Data are representative of three individual experiments with similar results. (E) Cells were treated as follows. Control: Untreated cells. Ba: Cells were pretreated with Ba (108 cfu/ml, 6 h). 3-MA: Cells treated with 3-MA (2 mM). Ba+3-MA: Cells pretreated with 3-MA (2mM, 3 h) and then incubated with Ba (108 cfu/ml, 6 h). All the group were infected with E. coli (MOI = 30, 1 h). Following incubation with gentamicin for 1, 8, or 20 h, cells were lysed with 1% Triton X-100 in PBS, and the cfu was counted. Portions of the lysates were used to measure the concentration of cell protein. Remaining E. coli (cfu/mg) = Remaining E. coli/cell protein concentration. Values are from three independent experiments with similar results, one-way ANOVA, Tukey test, ∗p < 0.05.

The phagocytosis and bactericidal activity in RAW264.7 cells were monitored by scoring bacterial colony forming units (cfu). As shown in Figure 4E, Ba significantly increased the uptake of E. coli (t = 1) (2.01 ± 0.15 × 106 cfu/mg), compared with the control group (1.18 ± 0.19 × 106 cfu/mg). Following 8 h incubation, the intracellular bacteria dropped but with no significance among all the groups. However, after 20 h, the number of E. coli in Ba-treated cells experienced a dramatic decrease (0.40 ± 0.08 × 106 cfu/mg), compared to untreated cells (0.56 ± 0.10 × 106 cfu/mg). Interestingly, when adding 3-MA to inhibit autophagy, antibacterial activity dramatically decreased, with 0.85 ± 0.09 × 106 cfu/mg E. coli in Ba treated cells after 20 h. Taken together, the results suggest that Ba-induced autophagy enhances the elimination of E. coli in RAW264.7 cells.

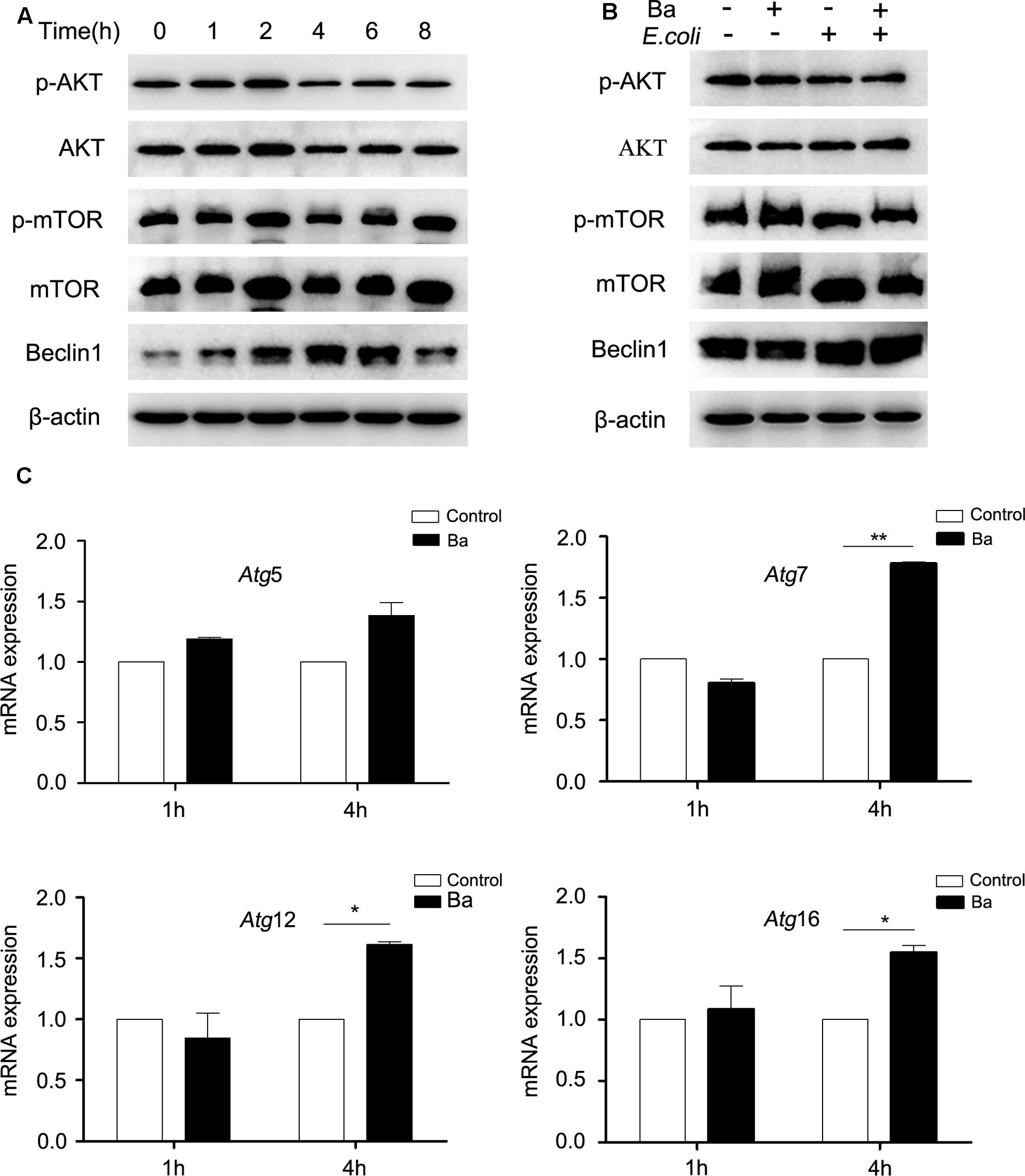

Ba Induces Autophagy by Upregulating the Expression of Beclin1 and Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 Complex, But Not by AKT/mTOR Signaling Pathway

To elucidate the underlying mechanisms of Ba-induced autophagy, we examined the effect of Ba on autophagic signaling pathways (Beclin1 and AKT/mTOR). Cells were incubated with Ba alone for different lengths of time (0, 1, 2, 4, 6, 8 h), or pretreated with Ba for 6 h and subsequently challenged with E. coli for 1 h. Beclin1 is a core protein in autophagosome nucleation (McKnight and Yue, 2013). Results revealed that Beclin1 expression was upregulated in a time-dependent manner in response to Ba treatment alone (p < 0.05; Figure 5A and Supplementary Figure S1C). Consistently, pretreatment with Ba led to an increasing level of Beclin1 when cells were infected with E. coli (Figure 5B and Supplementary Figure S1). The inhibition of AKT/mTOR phosphorylation can activate autophagy (Mizushima, 2010). Western blotting analyses showed no significant changes of p-AKT/AKT and p-mTOR/mTOR after Ba treatment alone (p > 0.05, Figure 5A and Supplementary Figures S1A,B), and similar results could also be obtained during E. coli challenge (Figure 5B and Supplementary Figures S1D,E).

FIGURE 5. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 (Ba) upregulates the expression of Beclin1, but not the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway in RAW264.7 cells (A) RAW264.7 cells were treated with 108 cfu/ml Ba for 0 to 8 h. The cells were then harvested and analyzed by western blotting using anti-phospho-AKT, anti-AKT, anti-phospho-mTOR, anti-mTOR, Beclin1, or anti-β-actin antibody. (B) RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with Ba (108 cfu/ml, 6 h), and then infected with E. coli (MO = 30, 1 h). Western analysis was the same as (A). (C) Cells were treated with Ba (108 cfu/ml) for 1 or 4 h, and then the mRNA expressions of Atg5, Atg7, Atg12i, and Atg16 were detected by quantitative Real-Time PCR. Values are from three independent experiments with similar results, t-test, ∗ p < 0.05, ∗∗p < 0.01.

We also determined the mRNA expression of an autophagic complex Atg5-Atg12-Atg16, which is essential to LC3-II ligation to the autophagosome membrane (Klionsky et al., 2012). RAW264.7 cells were treated with Ba for 1 or 4 h. The mRNA expression levels of all the tested genes showed no differences after Ba treatment for 1 h (p > 0.05) (Figure 5C). However, after 4 h treatment, the mRNA expressions of Atg7 (p < 0.01), Atg12 and Atg16 (p < 0.05) increased markedly (Figure 5C).

All these observations suggest that Beclin1 and Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex may play important roles in the induction of autophagy in RAW264.7 cells by Ba treatment. However, the AKT/mTOR signaling pathway is not involved in Ba-induced autophagy.

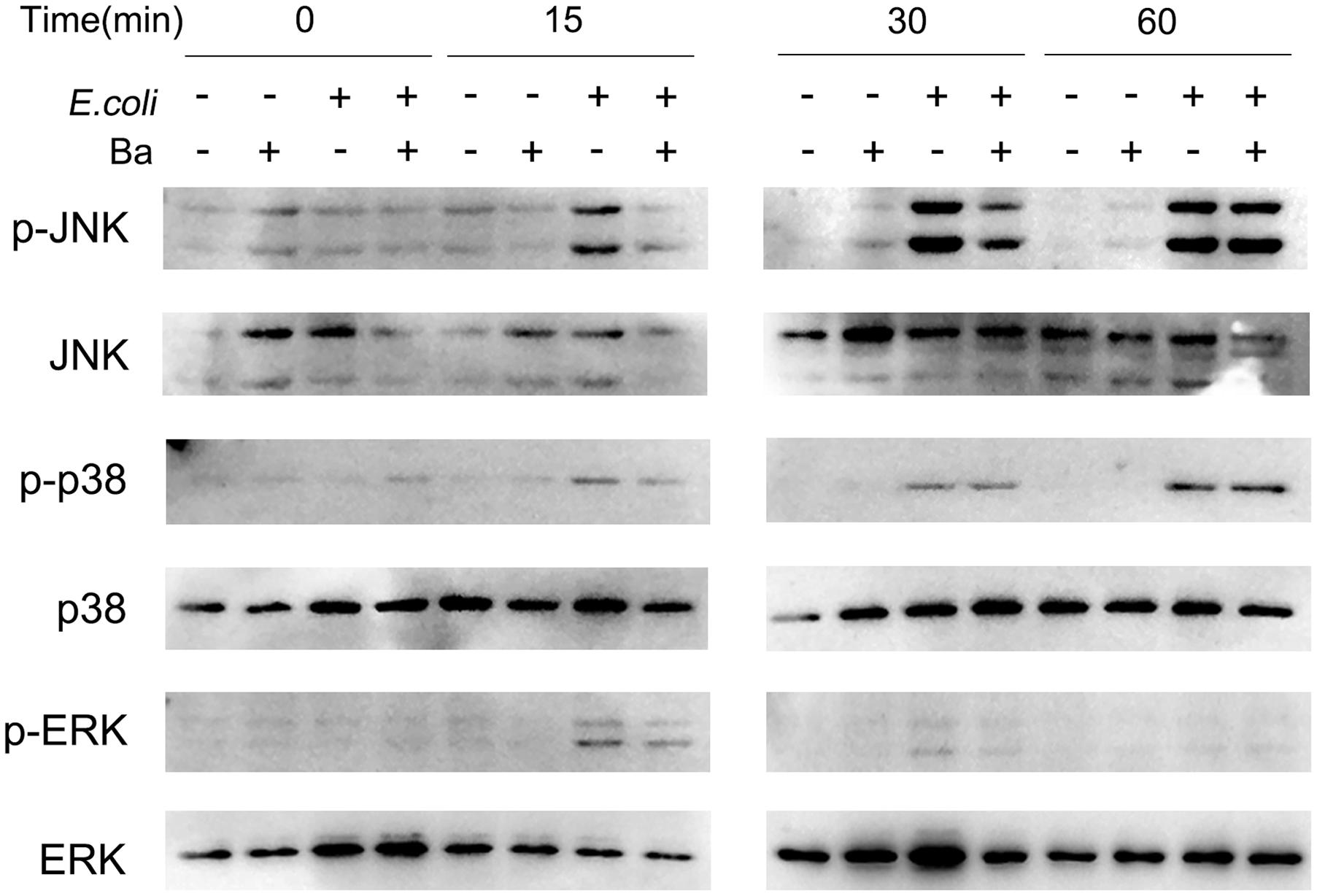

Ba Decreases the Phosphorylation of JNK Under Conditions of E. coli Infection in RAW264.7 Cells

As previous studies verified a critical role of MAPK signaling pathways in mediating microorganism–host interaction, we asked whether these pathways were activated in RAW264.7 cells during Ba treatment or E. coli infection. As shown in Figure 6, JNK phosphorylation remained at basal level during Ba treatment alone, but experienced a rapid increase when cells were challenged with E. coli after 15 min. Surprisingly, pretreated with Ba led to a dramatic decline in JNK phosphorylation. The accumulation of phospho-p38 in E. coli-infected cells started at 15 min and peaked at 60 min, but showed no significant difference when pretreated with Ba. Neither exposure to E. coli nor Ba significantly activated ERK phosphorylation, although a slight upward trend was observed at 15 and 30 min.

FIGURE 6. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 inhibits JNK phosphorylation in RAW264.7 cells. RAW264.7 cells were pretreated with Ba (108 cfu/ml, 6 h), and then infected with E. coli (MOI = 30) for 0, 15, 30, or 60 min. The expressions of phospho-JNK, JNK, phospho-p38, p38, phospho-ERK, and ERK were detected by western blotting.

Discussion

The relationship between probiotics and improved gut health has received considerable scientific interests for more than a century. Accumulating evidence supports the well-characterized immune modulation of probiotics in preventing intestinal diseases (Isaacs and Herfarth, 2008; Kleta et al., 2014; Lenoir-Wijnkoop et al., 2014). Macrophages, as important immune cells in intestine, when activated, can rapidly respond to pathogenic microorganisms by releasing inflammatory cytokines (Fernando et al., 2014). Our study indicates that probiotic can also enhance pathogen inhibition by triggering autophagy in macrophages, which provides valuable insights into the mechanism of probiotics in maintaining gut health.

Pathogens control is also one of the most important topics in food safety. In animal husbandry, the overuse of antibiotics can lead to severe drug resistance and increase food safety risks (Gilchrist et al., 2007). For these reasons, antibiotics have been forbidden in feed in Europe since 2006 (Chu et al., 2013). In order to produce safe and reliable animal products, probiotics such as Lactobacillus, Bifidobacterium and Bacillus are considered to be promising substitutes for antibiotics to prevent bacterial diseases (Zacarias et al., 2014; Yang et al., 2015; Guo et al., 2016). Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, belonging to Bacillus genus, is a species closely related to Bacillus subtilis (Xu Z. et al., 2013). With strong bactericidal activity to suppress numerous pathogens (fungi and bacteria) (Xu Z. et al., 2013; Wu et al., 2014; Torres et al., 2017), B. amyloliquefaciens strains, are not only widely used as plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and biocontrol agents in agriculture (Soylu et al., 2005; Chowdhury et al., 2015), but also have been attracted to be potential biopreservative in food industry (Kaewklom et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2014). In recent years, an increasing number of reports further their beneficial effects on the growth performance and infectious disease resistance of animals when being used as probiotics (Gracia et al., 2003; Das et al., 2013; Thy et al., 2017). Our previous trials found that supplement with Ba inhibited E. coli-induced pro-inflammatory responses and alleviated diarrhea in weaned pigs (Ji et al., 2013). Similarly, B. amyloliquefaciens protected against Clostridium difficile-associated disease in a mouse model (Geeraerts et al., 2015). Previous studies highlighted that B. amyloliquefaciens strains exerted antagonistic activity against pathogens by producing diverse bioactive metabolites including lipopeptides, fengycin, and iturin (Wong et al., 2008). Here we found that heat-killed Ba itself could trigger immune response and protect against pathogens, this deepen the mechanisms of their antimicrobial effects and further their use as probiotics.

Our study is the first to show that probiotic-mediated autophagy contributes to bacterial inhibition by macrophages. Using western blotting and confocal laser scanning analysis, we found that treatment with Ba induced autophagy-related processes including LC3-II accumulation, p62 degradation, and LC3 puncta aggregation in RAW264.7 cells. Furthermore, cells pretreated with Cq, an inhibitor of autophagic flux, facilitated the ratio of LC3-II/LC3-I and the accumulation of p62 during Ba treatment. Taken together, these findings demonstrate Ba can act as a stimulant of autophagic activity in RAW264.7 cells.

We determine that probiotic-induced autophagy inhibits E. coli growth in RAW264.7 cells. Pretreatment of infected cells with Ba remarkably elevated the LC3-II expression, phagocytosis, co-localization of RFP-E. coli within autophagosomes and E. coli elimination. Moreover, 3-MA blockade of autophagy dramatically impaired bactericidal activity. Thus, we confirm autophagy activated by Ba contributes to the inhibition of intracellular E. coli. Consistent with our findings, other investigators have reported that enhanced autophagy played a role in pathogen elimination. Wang et al. (2013) revealed LPS-induced autophagy was a cell-autonomous defense mechanism involved in the restriction of E. coli in peritoneal mesothelial cells. Another study demonstrated poly(I:C)-induced autophagy mediated the elimination of mycobacteria in macrophages (Xu Y. et al., 2013). Physiological induction of autophagy or its pharmacological stimulation by rapamycin could suppress intracellular survival of mycobacteria in infected macrophages (Gutierrez et al., 2004).

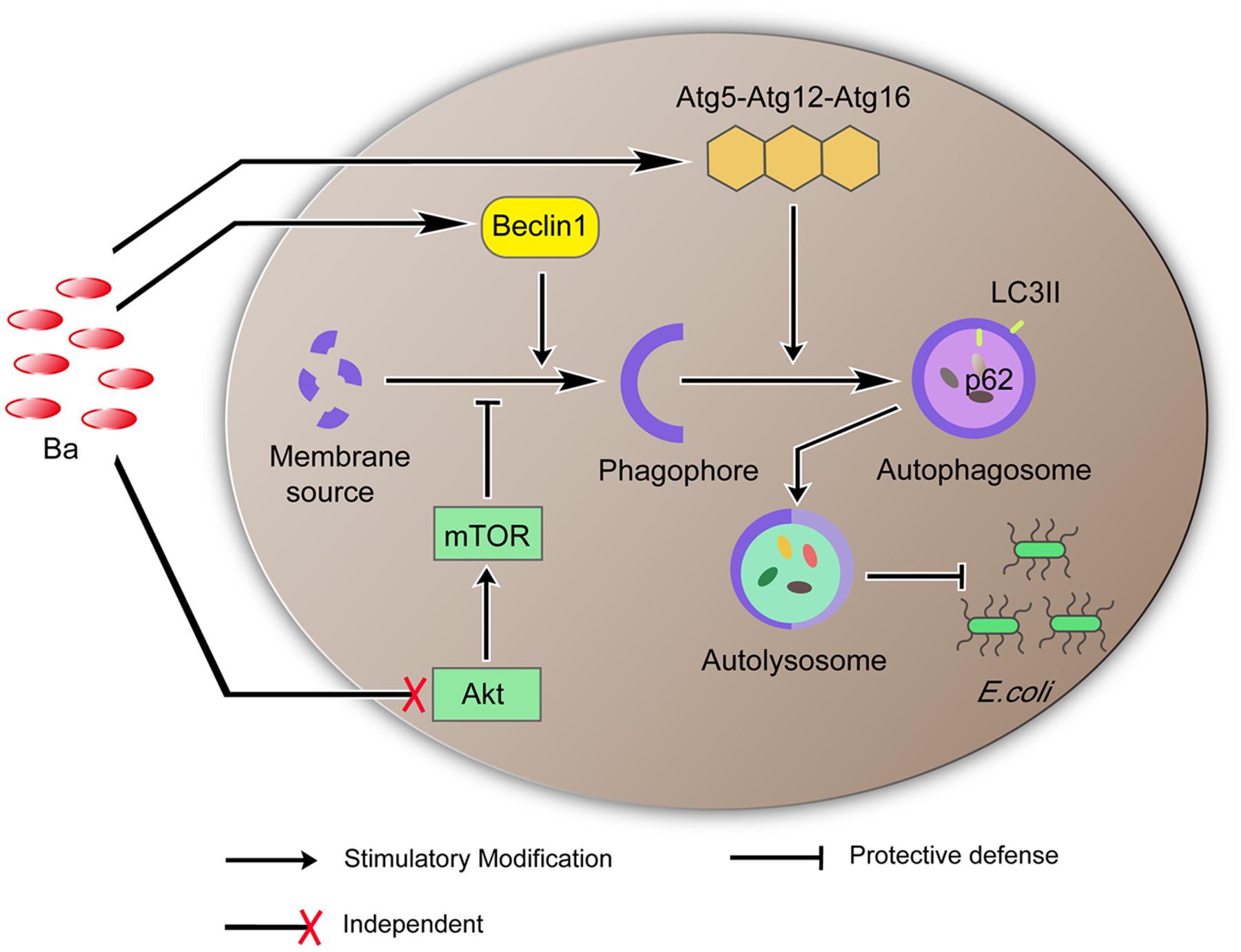

We also determine that Ba alters expression of several signaling pathways and proteins that regulate autophagy. Beclin 1, as a core component of class III phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase (PI3K-III) complex, enables recruitment of a number of autophagy proteins involved in the nucleation of autophagosome (McKnight and Yue, 2013). The Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex is a ubiquitin-like complex that is required in the final step of autophagosome formation, elongation of isolation membrane and/or completion of enclosure (McKnight and Yue, 2013). We found that Ba significantly upregulated Beclin1 expression in a time-dependent manner in RAW264.7 cells. Beclin1 expression also experienced an uptrend when pretreated with Ba during E. coli infection. The mRNA expression levels of Atg7, Atg12, Atg16 increased significantly after Ba treatment. Additionally, one of the most conserved autophagy pathways is dependent on the metabolic checkpoint kinase mTOR, which can be initiated by AKT (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). During nutrient starvation or other stress, the activity of AKT/mTOR is inhibited, resulting in translocation of ULK complex (ULK1/2, Atg13, FIP200, and Atg101) which activates autophagy (Mizushima, 2010). Surprisingly, our study showed that phosphorylations of mTOR and AKT were not decreased by Ba treatment alone or subsequent E. coli infection. mTOR is assembled and functional only when cellular nutrients or cofactors are not limited (Laplante and Sabatini, 2012). Unlike some pathogens, such as Salmonella or Listeria, may trigger a rapid inhibition of mTOR signaling through competition for nutrients (Tattoli et al., 2012, 2013). Ba delivers a mild stimulus to cells and no nutrients competition, thus it might explain no reduction of phosphorylation levels of AKT and mTOR. Taken together, the signaling pathways involved in the activation of autophagy by Ba were not dependent in AKT/mTOR, but possibly via regulating expressions of Beclin1 and Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7. Proposed model of Ba-induced autophagy and its function in eliminating E. coli. Ba upregulates the expression of Beclin1. Beclin1 promotes formation of the phagophore. The phagophore incorporates the Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex into its membrane to generate an autophagosome which consumes and lyses invading pathogens. AKT/MTOR is independent in this process.

Mitogen-activated protein kinase signaling pathway is one of the most important regulators of physiological cell processes including inflammation, stress, cell growth, differentiation and death. JNK is considered to be activated by a number of stressors which can induce apoptosis or growth inhibition (Bogoyevitch and Kobe, 2006). Our study showed that JNK phosphorylation in RAW264.7 cells increased after 15min, and lasted up to 60 min when infected with E. coli. Similarly, studies showed that infected with S. Flexneri for 20 min increased JNK activation in HeLa cells (Girardin et al., 2001) and E. caratavora induced JNK phosphorylation after 30 min in Drosophila larvae (Jones et al., 2008). During bacterial infection, the rapid activation of JNK initiates nuclear factor activator protein-1 (AP-1) to regulate pro-inflammatory cytokines expression, which could trigger excessive inflammation (Weston and Davis, 2007; Zhang et al., 2013). Interestingly, we observed that pretreatment with Ba for 6 h inhibited the activation of JNK. Similar results were found in other probiotics. For example, Lactobacillus attenuated the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines caused by E. coli challenge by downregulating JNK activation in Caco-2 cells (Yu et al., 2015); Increased JNK activity in obese mice was abolished during probiotic administration (Toral et al., 2014). According to previous and our results, we can deduce that, the suppression of JNK activity by Ba has a protective effect during E. coli infection and Ba might play an anti-inflammatory role in RAW264.7 cells. Furthermore, we investigate whether the inhibition of JNK is associated with autophagy. Autophagy is involved in both cell death and cell survival depending on the cell type and strength of specific stimuli (Janku et al., 2011). A previous study demonstrated that JNK activation mainly contributed to autophagic cell death, which eventually caused cell apoptosis (Bowrsello et al., 2003). Therefore, we speculate that probiotic Ba, as a mild activator, triggers cell protective autophagy and enhances the immune function of RAW264.7 cells during E. coli challenge by suppressing JNK phosphorylation and inhibiting E. coli-induced pro-inflammatory responses.

In summary, the present study reveals that heat-killed probiotic Ba activates autophagy via upregulating the expression of Beclin1 and Atg5-Atg12-Atg16 complex and that the induced-autophagy promotes the elimination of E. coli in RAW264.7 cells. Moreover, Ba reduces the levels of JNK phosphorylation triggered by E. coli, indicating an anti-inflammatory role of Ba. To our knowledge, this is the first report to uncover probiotic-mediate autophagy enhancement of the antibacterial activity of macrophages. These findings deepen our understanding of the immune protective capabilities of probiotics and may aid in the application of probiotics in the food industry to improve human or animal’s health. However, whether these protected mechanism function in vivo warrants further investigation.

Author Contributions

WL, XX, and QS conceived and designed the experiments; YpW, YW, AF, YyW, and YbW performed the experiments; YW analyzed the data; YpW and BW made the figures; YpW, HZ, and YW wrote the paper.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

This study is supported by National High-Tech R & D Program (863) of China (No. 2013AA102803D), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 31672460 and 31472128), and the Major Science and Technology Project of Zhejiang Province (No. 2006C12086), China.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2017.00469/full#supplementary-material

FIGURE S1 | (A–F) Densitometric analyses of p-AKT/AKT, p-mTOR/mTOR, and Beclin-1/β-actin in Figures 5A,B. Values are from three independent experiments with similar results, one-way ANOVA, Tukey test, ∗p < 0.05.

References

Bento, C. F., Empadinhas, N., and Mendes, V. (2015). Autophagy in the fight against tuberculosis. DNA Cell Biol. 34, 228–242. doi: 10.1089/dna.2014.2745

Bogoyevitch, M. A., and Kobe, B. (2006). Uses for JNK: the many and varied substrates of the c-Jun N-terminal kinases. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 70, 1061–1095. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00025-06

Boudeau, J., Glasser, A. L., Masseret, E., Joly, B., and Michaud, A. D. (1999). Invasive ability of an Escherichia coli strain isolated from the ileal mucosa of a patient with Crohn’s disease. Infect. Immun. 67, 4499–4509.

Bowrsello, T., Croquelois, K., Hornung, J. P., and Clarke, P. G. (2003). N-methyl- d- aspartate-triggered neuronal death in organotypic hippocampal cultures is endocytic, autophagic and mediated by the c-Jun N-terminal kinase pathway. Eur. J. Neurosci. 18, 473–485. doi: 10.1046/j.1460-9568.2003.02757.x

Candela, M., Perna, F., Carnevali, P., Vitali, B., Ciati, R., Gionchetti, R., et al. (2008). Interaction of probiotic Lactobacillus and Bifidobacterium strains with human intestinal epithelial cells: adhesion properties, competition against enteropathogens and modulation of IL-8 production. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 125, 286–292. doi: 10.1016/j.Ijfoodmicro.2008.04.012

Chargui, A., Cesaro, A., Mimouna, S., Fareh, M., Brest, P., Naquet, P., et al. (2012). Subversion of autophagy in adherent invasive Escherichia coli-infected neutrophils induces inflammation and cell death. PLoS ONE 7:e51727. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0051727

Chowdhury, S. P., Hartmann, A., Gao, X., and Borriss, R. (2015). Biocontrol mechanism by root-associated Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42-a review. Front. Microbiol. 6:780. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00780

Chu, G. M., Jung, C. K., Kim, H. Y., Ha, J. H., Kim, J. H., Jung, M. S., et al. (2013). Effects of bamboo charcoal and bamboo vinegar as antibiotic alternatives on growth performance, immune responses and fecal microflora population in fattening pigs. Anim. Sci. J. 84, 113–120. doi: 10.1111/j.1740-0929.2012.01045.x

Das, A., Nakhro, K., Chowdhury, S., and Kamilya, D. (2013). Effects of potential probiotic Bacillus amyloliquifaciens FPTB16 on systemic and cutaneous mucosal immune responses and disease resistance of catla (Catla catla). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 35, 1547–1553. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2013.08.022

Djaldetti, M., and Bessler, H. (2017). Probiotic strains modulate cytokine production and the immune interplay between human peripheral blood mononucear cells and colon cancer cells. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. doi: 10.1093/femsle/fnx014 [Epub ahead of print].

Fernando, M. R., Reyes, J. L., Iannuzzi, J., Leung, G., and McKay, D. M. (2014). The pro-inflammatory cytokine, interleukin-6, enhances the polarization of alternatively activated macrophages. PLoS ONE 9:e94188. doi: 10.1371/journal.Pone.0094188

Geeraerts, S., Ducatelle, R., Haesebrouck, F., and Immerseel, F. V. (2015). Bacillus amyloliquefaciens as prophylactic treatment for Clostridium difficile- associated disease in a mouse model. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 30, 1275–1280. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12957

Giacomin, P., Agha, Z., and Loukas, A. (2016). Helminths and intestinal flora team up to improve gut health. Trends Parasitol. 32, 664–666. doi: 10.1016/j.pt.2016.05.006

Gilchrist, M. J., Greko, C., Wallinga, D. B., Beran, G. W., Riley, D. G., and Thorne, P. S. (2007). The potential role of concentrated animal feeding operations in infectious disease epidemics and antibiotic resistance. Environ. Health Perspect. 115, 313–316. doi: 10.1289/ehp.8837

Girardin, S. E., Tournebize, R., Mavris, M., Page, A. L., Li, X., Stark, G. R., et al. (2001). CARD4/Nod1 mediates NF-kB and JNK activation by invasive Shigella flexneri. EMBO Rep. 2, 736–742. doi: 10.1093/embo-reports/kve155

Gracia, M. I., Araníbar, M. J., Lázaro, R., Medel, P., and Mateos, G. G. (2003). α-Amylase supplementation of broiler diets based on corn. Poult. Sci. 82, 436–442. doi: 10.1093/ps/82.3.436

Guo, M., Hao, G., Wang, B., Li, L., Li, R., Wei, L., et al. (2016). Dietary administration of Bacillus subtilis enhances growth performance, immune response and disease resistance in Cherry Valley ducks. Front. Microbiol. 7:1975. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2016.01975

Gutierrez, M. G., Master, S. S., Singh, S. B., Taylor, G. A., Colombo, M. I., and Deretic, V. (2004). Autophagy is a defense mechanism inhibiting BCG and Mycobacterium tuberculosis survival in infected macrophages. Cell 119, 753–766. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.038

Hill, C., Guarner, F., Reid, G., Gibson, G. R., Merenstein, D. J., Pot, B., et al. (2014). Expert consensus document. The international scientific association for probiotics and prebiotics consensus statement on the scope and appropriate use of the term probiotic. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 11, 506–514. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2014.66

Isaacs, K., and Herfarth, H. (2008). Role of probiotic therapy in IBD. Inflamm. Bowel Dis. 14, 1597–1605. doi: 10.1002/ibd.20465

Isidro, R. A., Bonilla, F. J., Pagan, H., Cruz, M. L., Lopez, P., Godoy, L., et al. (2014). The probiotic mixture VSL# 3 alters the morphology and secretion profile of both polarized and unpolarized human macrophages in a polarization-dependent manner. J. Clin. Microbiol. 5:1000227. doi: 10.4172/2155-9899.1000227

Janku, F., McConkey, D. J., Hong, D. S., and Kurzrock, R. (2011). Autophagy as a target for anticancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 8, 528–539. doi: 10.1038/nrclinonc.2011.71

Ji, J., Hu, S., Zheng, M., Du, W., Shang, Q., and Li, W. (2013). Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 inhibits ETEC-induced pro-inflammatory responses by suppression of MAPK signaling pathways in IPEC-1 cells and diarrhea in weaned piglets. Livest. Sci. 58, 206–214. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2013.09.017

Jones, R. M., Wu, H., Wentworth, C., Luo, L., Collier-Hyams, L., and Neish, A. S. (2008). Salmonella AvrA coordinates suppression of host immune and apoptotic defenses via JNK pathway blockade. Cell Host Microbe. 3, 233–244. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2008.02.016

Kaewklom, S., Lumlert, S., Kraikul, W., and Aunpad, R. (2013). Control of Listeria monocytogenes on sliced bologna sausage using a novel bacteriocin, amysin, produced by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens isolated from Thai shrimp paste (Kapi). Food Control 32, 552–557. doi: 10.1016/j.foodcont.2013.01.012

Kim, Y., Oh, S., Yun, H. S., Oh, S., and Kim, S. H. (2010). Cell-bound exopolysaccharide from probiotic bacteria induces autophagic cell death of tumour cells. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 51, 123–130. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2010.02859.x

Kirkegaard, K., Taylor, M. P., and Jackson, W. T. (2004). Cellular autophagy: surrender, avoidance and subversion by microorganisms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2, 301–314. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro865

Kleta, S., Nordhoff, M., Tedin, K., Wieler, L. H., Kolenda, R., Oswald, S., et al. (2014). Role of F1C fimbriae, flagella, and secreted bacterial components in the inhibitory effect of probiotic Escherichia coli Nissle 1917 on atypical enteropathogenic E. coli infection. Infect. Immun. 82, 1801–1812. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01431-13

Klionsky, D. J., Abdalla, F. C., Abeliovich, H., Abraham, R. T., Acevedo-Arozena, A., Adeli, K., et al. (2012). Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 8, 445–544. doi: 10.4161/auto.19496

Laplante, M., and Sabatini, D. M. (2012). mTOR signaling in growth control and disease. Cell 149, 274–293. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.03.017

Lebeer, S., Vanderleyden, J., and De Keersmaecker, S. C. (2008). Genes and molecules of lactobacilli supporting probiotic action. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 72, 728–764. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00017-08

Lebeer, S., Vanderleyden, J., and De Keersmaecker, S. C. (2010). Host interactions of probiotic bacterial surface molecules: comparison with commensals and pathogens. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 8, 171–184. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2297

Lenoir-Wijnkoop, I., Nuijten, M. J. C., Craig, J., and Butler, C. C. (2014). Nutrition economic evaluation of a probiotic in the prevention of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. Front. Pharmacol. 5:13. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2014.00013

Levine, B., Mizushima, N., and Virgin, H. W. (2011). Autophagy in immunity and inflammation. Nature 469, 323–335. doi: 10.1038/nature09782

Lin, R., Jiang, Y., Zhao, X. Y., Guan, Y., Qian, W., Fu, X. C., et al. (2014). Four types of Bifidobacteria trigger autophagy response in intestinal epithelial cells. J. Digest. Dis. 15, 597–605. doi: 10.1111/1751-2980.12179

Ma, Y., Yu, S., Zhao, W., Lu, Z., and Chen, J. (2010). miR-27a regulates the growth, colony formation and migration of pancreatic cancer cells by targeting Sprouty2. Cancer Lett. 298, 150–158. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2010.06.012

Mao, Y., Wang, B., Xu, X., Du, W., Li, W., and Wang, Y. (2015). Glycyrrhizic acid promotes M1 macrophage polarization in murine bone marrow-derived macrophages associated with the activation of JNK and NF-κB. Mediators Inflamm. 2015, 1–12. doi: 10.1155/2015/372931

Martinez, J., Verbist, K., Wang, R., and Green, D. R. (2013). The relationship between metabolism and the autophagy machinery during the innate immune response. Cell Metab. 17, 895–900. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.012

McKnight, N. C., and Yue, Z. (2013). Beclin 1, an essential component and master regulator of PI3K-III in health and disease. Curr. Pathobiol. Rep. 1, 231–238. doi: 10.1007/s40139-013-0028-5

Mizushima, N. (2010). The role of the Atg1/ULK1 complex in autophagy regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 132–139. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.12.004

Mizushima, N. (2011). Autophagy in protein and organelle turnover. Cold Spring Harb. Symp. Quant. Biol. 76, 397–402. doi: 10.1101/sqb.2011.76.011023

Mosmann, T. (1983). Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J. Immunol. Methods 65, 55–63. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(83)90303-4

Musso, G., Gambino, R., and Cassader, M. (2010). Obesity, diabetes, and gut microbiota. Diabetes Care 33, 2277–2284. doi: 10.2337/dc10-0556

Naito, M. (2008). Macrophage differentiation and function in health and disease. Pathol. Int. 58, 143–155. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.2007.02203.x

Nakagawa, I., Amano, A., Mizushima, N., Yamamoto, A., Yamaguchi, H., Kamimoto, T., et al. (2004). Autophagy defends cells against invading group A Streptococcus. Science 306, 1037–1040. doi: 10.1126/science.1103966

Neal, M. D., Sodhi, C. P., Dyer, M., Craig, B. T., Good, M., Jia, H., et al. (2013). A critical role for TLR4 induction of autophagy in the regulation of enterocyte migration and the pathogenesis of necrotizing enterocolitis. J. Immunol. 190, 3541–3551. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202264

Neef, A., and Sanz, Y. (2013). Future for probiotic science in functional food and dietary supplement development. Curr. Opin. Clin. Nutr. 16, 679–687. doi: 10.1097/MCO.0b013e328365c258

Ouwehand, A. C., Derrien, M., de Vos, W., Tiihonen, K., and Rautonen, N. (2005). Prebiotics and other microbial substrates for gut functionality. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 16, 212–217. doi: 10.1016/j.copbio.2005.01.007

Pradhan, B., Guha, D., Ray, P., Das, D., and Aich, P. (2016). Comparative analysis of the effects of two probiotic bacterial strains on metabolism and innate immunity in the RAW 264.7 murine macrophage cell line. Probiotics Antimicrob. Proteins 8, 73–84. doi: 10.1007/s12602-016-9211-4

Prakash, S., Tomaro-Duchesneau, C., Saha, S., and Cantor, A. (2011). The gut microbiota and human health with an emphasis on the use of microencapsulated bacterial cells. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2011:981214. doi: 10.1155/2011/981214

Ranadheera, C. S., Evans, C. A., Adams, M. C., and Baines, S. K. (2014). Effect of dairy probiotic combinations on in vitro gastrointestinal tolerance, intestinal epithelial cell adhesion and cytokine secretion. J. Funct. Foods 8, 18–25. doi: 10.1016/j.jff.2014.02.022

Rekha, R. S., Rao Muvva, S. S. V. J., Wan, M., Raqib, R., Bergman, P., Brighenti, S., et al. (2015). Phenylbutyrate induces LL-37-dependent autophagy and intracellular killing of Mycobacterium tuberculosis in human macrophages. Autophagy 11, 1688–1699. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2015.1075110

Safari, R., Adel, M., Lazado, C. C., Caipang, C. M. A., and Dadare, M. (2016). Host-derived probiotics Enterococcus casseliflavus improves resistance against Streptococcus iniae infection in rainbow trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) via immunomodulation. Fish Shellfish Immunol. 52, 198–205. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.03.020

Schmittgen, T. D., Zakrajsek, B. A., Mills, A. G., Gorn, V., Singer, M. J., and Reed, M. W. (2000). Quantitative reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction to study mRNA decay: comparison of endpoint and real-time methods. Anal. Biochem. 285, 194–204. doi: 10.1006/abio.2000.4753

Soylu, S., Soylu, E. M., Kurt, S., and Ekici, O. K. (2005). Antagonistic potentials of rhizosphere-associated bacterial isolates against soil-borne diseases of tomato and pepper caused by Sclerotinia sclerotiorum and Rhizoctonia solani. Pak. J. Biol. Sci. 8, 43–48. doi: 10.3923/pjbs.2005.43.48

Tanida, I., Minematsu-Ikeguchi, N., Ueno, T., and Kominami, E. (2005). Lysosomal turnover, but not a cellular level, of endogenous LC3 is a marker for autophagy. Autophagy 1, 84–91. doi: 10.4161/auto.1.2.1697

Tattoli, I., Philpott, D. J., and Girardin, S. E. (2012). The bacterial and cellular determinants controlling the recruitment of mTOR to the Salmonella-containing vacuole. Biol. Open 1, 1215–1225. doi: 10.1242/bio.20122840

Tattoli, I., Sorbara, M. T., Yang, C., Tooze, S. A., Philpott, D. J., and Girardin, S. E. (2013). Listeria phospholipases subvert host autophagic defenses by stalling pre-autophagosomal structures. EMBO J. 32, 3066–3078. doi: 10.1038/emboj.2013.234

Thy, H. T. T., Tri, N. N., Quy, O. M., Fotedar, R., Kannika, K., Unajak, S., et al. (2017). Effects of the dietary supplementation of mixed probiotic spores of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens 54A, and Bacillus pumilus 47B on growth, innate immunity and stress responses of striped catfish (Pangasianodon hypophthalmus). Fish Shellfish Immunol. 60, 391–399. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2016.11.016

Toral, M., Gómez-Guzmán, M., Jiménez, R., Romero, M., Sánchez, M., Utrilla, M. P., et al. (2014). The probiotic Lactobacillus coryniformis CECT5711 reduces the vascular pro-oxidant and pro-inflammatory status in obese mice. Clin. Sci. 127, 33–45. doi: 10.1042/CS20130339

Torres, M. J., Brandan, C. P., Sabaté, D. C., Petroselli, G., Balsells, R. E., and Audisio, M. C. (2017). Biological activity of the lipopeptide-producing Bacillus amyloliquefaciens PGPBacCA1 on common bean Phaseolus vulgaris L. pathogens. Biol. Control 105, 93–99. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2016.12.001

Wang, J., Feng, X. R., Zeng, Y. J., Fan, J. J., Wu, J., Li, Z. J., et al. (2013). Lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced autophagy is involved in the restriction of Escherichia coli in peritoneal mesothelial cells. BMC Microbiol. 13:255. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-255

Wang, Y., Zhu, X., Bie, X., Lu, F., Zhang, C., Yao, S., et al. (2014). Preparation of microcapsules containing antimicrobial lipopeptide from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens ES-2 by spray drying. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 56, 502–507. doi: 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.11.041

Weston, C. R., and Davis, R. J. (2007). The JNK signal transduction pathway. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 19, 142–149. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2007.02.001

Whelan, K., and Quigley, E. M. M. (2013). Probiotics in the management of irritable bowel syndrome and inflammatory bowel disease. Curr. Opin. Gastroenterol. 29, 184–189. doi: 10.1097/MOG.0b013e32835d7bba

Wong, J. H., Hao, J., Cao, Z., Qiao, M., Xu, H., Bai, Y., et al. (2008). An antifungal protein from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. J. Appl. Microbiol. 105, 1888–1898. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2008.03917.x

Wu, L., Wu, H., Chen, L., Xie, S., Zang, H., Borriss, R., et al. (2014). Bacilysin from Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 has specific bactericidal activity against harmful algal bloom species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 80, 7512–7520. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02605-14

Wu, S. P., Yuan, L. J., Zhang, Y. G., Liu, F. N., Li, G. H., Wen, K., et al. (2013). Probiotic Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG mono-association suppresses human rotavirus-induced autophagy in the gnotobiotic piglet intestine. Gut Pathog. 5:22. doi: 10.1186/1757-4749-5-22

Xu, Y., Fattah, E. A., Liu, X. D., Jagannath, C., and Eissa, N. T. (2013). Harnessing of TLR-mediated autophagy to combat mycobacteria in macrophages. Tuberculosis 93, S33–S37. doi: 10.1016/S1472-9792(13)70008-8

Xu, Z., Shao, J., Li, B., Yan, X., Shen, Q., and Zhang, R. (2013). Contribution of bacillomycin D in Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SQR9 to antifungal activity and biofilm formation. Appl. Environ. microbiol. 79, 808–815. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02645

Xu, Z., Yang, L., Xu, S., Zhang, Z., and Cao, Y. (2015). The receptor proteins: pivotal roles in selective autophagy. Acta Biochim. Biophys. Sin. 47, 571–580. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmv055

Yang, F., Hou, C., Zeng, X., and Qiao, S. (2015). The use of lactic acid bacteria as a probiotic in swine diets. Pathogens 4, 34–45. doi: 10.3390/pathogens4010034

Yang, Z., and Klionsky, D. J. (2010). Mammalian autophagy: core molecular machinery and signaling regulation. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 22, 124–131. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2009.11.014

Yu, Q., Yuan, L., Deng, J., and Yang, Q. (2015). Lactobacillus protects the integrity of intestinal epithelial barrier damaged by pathogenic bacteria. Front. Cell Infect. Microbiol. 5:26. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2015.00026

Zacarias, M. F., Reinheimer, J., Forzani, L., Grangette, C., and Vinderola, G. (2014). Mortality and translocation assay to study the protective capacity of Bifidobacterium lactis INL1 against Salmonella Typhimurium infection in mice. Benef. Microbes 5, 427–436. doi: 10.3920/BM2013.0086

Zhang, W., Ju, J., Rigney, T., and Tribble, G. (2013). Integrin α5β1-fimbriae binding and actin rearrangement are essential for Porphyromonas gingivalis invasion of osteoblasts and subsequent activation of the JNK pathway. BMC Microbiol. 13:5. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-13-5

Keywords: probiotics, Bacillus amyloliquefaciens, autophagy, pathogens, antibacterial activity, signaling pathways

Citation: Wu Y, Wang Y, Zou H, Wang B, Sun Q, Fu A, Wang Y, Wang Y, Xu X and Li W (2017) Probiotic Bacillus amyloliquefaciens SC06 Induces Autophagy to Protect against Pathogens in Macrophages. Front. Microbiol. 8:469. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00469

Received: 30 December 2016; Accepted: 07 March 2017;

Published: 22 March 2017.

Edited by:

Michael Gänzle, University of Alberta, CanadaReviewed by:

Soner Soylu, Mustafa Kemal University, TurkeyMehrdad Mark Tajkarimi, University of North Carolina at Greensboro, USA

Copyright © 2017 Wu, Wang, Zou, Wang, Sun, Fu, Wang, Wang, Xu and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xiaogang Xu, eGlhb3hpYW9nYW5nMjAwM0AxMjYuY29t Weifen Li, d2ZsaUB6anUuZWR1LmNu

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Yanping Wu

Yanping Wu Yang Wang1†

Yang Wang1† Hai Zou

Hai Zou Baikui Wang

Baikui Wang Yuanyuan Wang

Yuanyuan Wang Xiaogang Xu

Xiaogang Xu Weifen Li

Weifen Li