- 1Maryland Pathogen Research Institute, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA

- 2CosmosID, Inc., Rockville, MD, USA

- 3Center of Bioinformatics and Computational Biology, University of Maryland Institute of Advanced Computer Studies, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA

- 4International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 5Department of Microbiology, University of Dhaka, Dhaka, Bangladesh

- 6Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health, Baltimore, MD, USA

- 7Maryland Institute of Applied Environmental Health, University of Maryland, College Park, MD, USA

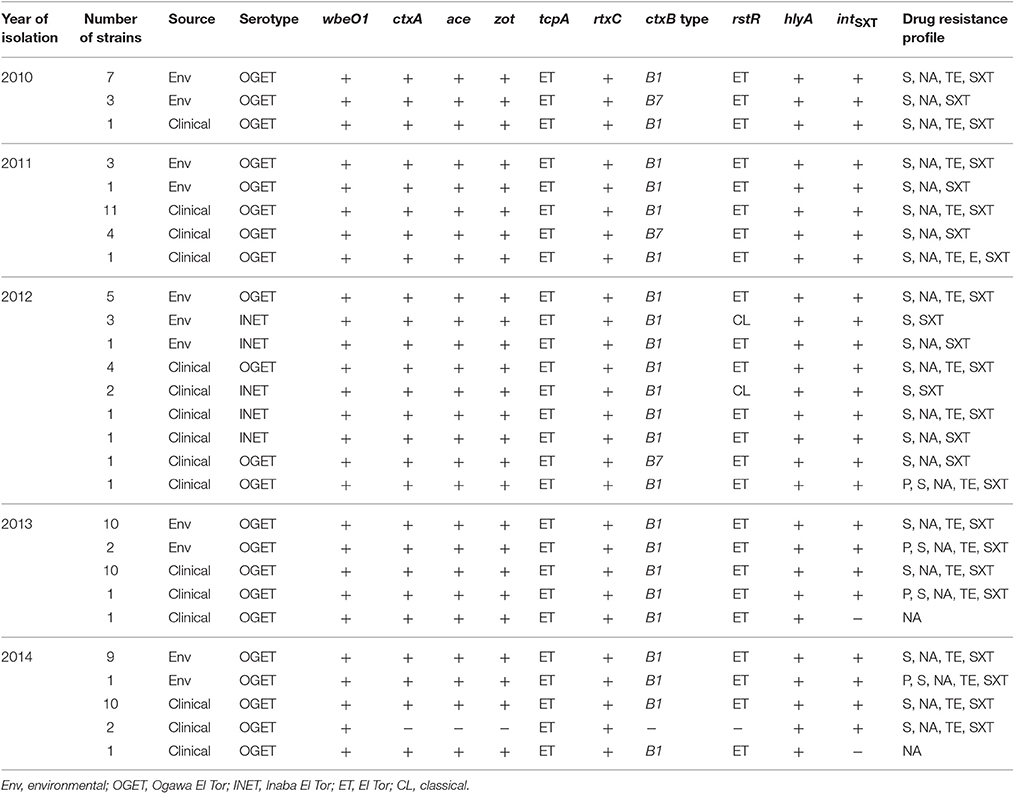

Cholera outbreaks occur each year in the remote coastal areas of Bangladesh and epidemiological surveillance and routine monitoring of cholera in these areas is challenging. In this study, a total of 97 Vibrio cholerae O1 isolates from Mathbaria, Bangladesh, collected during 2010 and 2014 were analyzed for phenotypic and genotypic traits, including antimicrobial susceptibility. Of the 97 isolates, 95 possessed CTX-phage mediated genes, ctxA, ace, and zot, and two lacked the cholera toxin gene, ctxA. Also both CTX+ and CTX− V. cholerae O1 isolated in this study carried rtxC, tcpAET, and hlyA. The classical cholera toxin gene, ctxB1, was detected in 87 isolates, while eight had ctxB7. Of 95 CTX+ V. cholerae O1, 90 contained rstRET and 5 had rstRCL. All isolates, except two, contained SXT related integrase intSXT. Resistance to penicillin, streptomycin, nalidixic acid, sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, erythromycin, and tetracycline varied between the years of study period. Most importantly, 93% of the V. cholerae O1 were multidrug resistant. Six different resistance profiles were observed, with resistance to streptomycin, nalidixic acid, tetracycline, and sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim predominant every year. Ciprofloxacin and azithromycin MIC were 0.003–0.75 and 0.19–2.00 μg/ml, respectively, indicating reduced susceptibility to these antibiotics. Sixteen of the V. cholerae O1 isolates showed higher MIC for azithromycin (≥0.5 μg/ml) and were further examined for 10 macrolide resistance genes, erm(A), erm(B), erm(C), ere(A), ere(B), mph(A), mph(B), mph(D), mef(A), and msr(A) with none testing positive for the macrolide resistance genes.

Introduction

Vibrio cholerae, the causative agent of cholera, is autochthonous to the estuarine and marine environment worldwide. Of more than 200 O-antigen serogroups identified in V. cholerae, only toxigenic O1 and O139 are primarily associated with epidemics and pandemics (Sack et al., 2004). Cholera, an ancient diarrheal disease, continues to be a serious threat in countries of Asia, Africa, and South America. Even though cholera is underreported in many countries, 3–5 million cases are recorded annually in different parts of the world, with a significant number of deaths (Ali et al., 2012). The case fatality rate of cholera has been reduced over the past few decades, mainly because patients are treated with oral and/or intravenous rehydration therapy together with appropriate dosage of antibiotics. Effective antibiotic treatment shortens the duration of diarrhea and limits the loss of body fluids by ca. 50% (Sack et al., 2004). However, antibiotic resistant enteropathogens, including V. cholerae, are emerging rapidly due to the selective pressure of antibiotics existing in the environment and from excessive use (Laxminarayan et al., 2013; Andersson and Hughes, 2014). V. cholerae, both O1 and O139, have developed resistance to several antimicrobial drugs, including tetracycline (TE), chloramphenicol (C), furazolidone, ampicillin (AM), and trimethoprim-cotrimoxazole, used successfully to treat cholera over the years (Garg et al., 2001; Kitaoka et al., 2011). As a consequence, multidrug resistant (MDR) V. cholerae has been on the rise, causing clinicians to face a serious challenge when deciding a drug of choice and regimen for treating cholera patients.

Two biotypes of V. cholerae O1, Classical (CL) and El Tor (ET) are universally recognized, with each possessing distinct phenotypic and genetic traits, including major virulence genes, i.e., toxin coregulated pilus (tcpA) and B-subunit of cholera toxin (ctxB; Kaper et al., 1995; Safa et al., 2010). Of the two biotypes, CL is associated with the sixth and presumably the earlier pandemics of cholera that occurred between 1817 and 1923 (Kaper et al., 1995; Devault et al., 2014), while ET is reported to have initiated the ongoing seventh pandemic in the early 1960s, gradually displacing the CL biotype (Kaper et al., 1995; Kim et al., 2015). Over the past two decades, variants of ET with only a few CL attributes (phage-encoded repressor rstRCL and B-subunit of cholera toxin ctxBCL) have emerged in Asia and Africa. These variants are collectively known as atypical ET (Safa et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2015). Moreover, based on amino acid substitutions in CtxB, 12 different ctxB genotypes have been identified in V. cholerae (Kim et al., 2015). In 1992, V. cholerae O139 carrying the SXT/R391 family integrative conjugative element (ICE) appeared transiently as the major cause of cholera in Bangladesh and India (Albert et al., 1993; Ramamurthy et al., 1993; Waldor et al., 1996). SXT/R391 ICE was the first MDR marker detected in V. cholerae, conferring resistance to streptomycin (S), sulfamethoxazole, and trimethoprim (Waldor et al., 1996; Hochhut et al., 2001). SXT/R391 ICE also found to provide a selective advantage to V. cholerae O1 ET, a strain that has been tracked globally in three overlapping waves during the seventh pandemic (Mutreja et al., 2011).

Interestingly, outbreaks of cholera that occur in the coastal areas are seasonal each year in Bangladesh. For example, in Mathbaria, cholera occurs predominantly during the spring, months of March through May, with inhabitants lacking safe drinking water are most susceptible (Emch et al., 2008; Akanda et al., 2013). Several antibiotics are used to treat cholera, including doxycycline, ciprofloxacin (CIP), and azithromycin (AZ), all greatly influenced by the drug sensitivity pattern of the bacterium reported in the contemporary literature (Harris et al., 2012). In Bangladesh, a single dose of AZ or CIP currently is used for prophylactic treatment. Not surprising, V. cholerae O1 is now reported to have reduced susceptibility to CIP in Bangladesh, India, Vietnam, Haiti, Zimbabwe, and Western Africa (Islam et al., 2009; Quilici et al., 2010; Sjölund-Karlsson et al., 2011; Tran et al., 2012; Kumar et al., 2014; Khan et al., 2015). MDR V. cholerae O1 resistant to TE, AM, S, sulfonamides, norfloxacin, gentamicin, furazolidone, kanamycin (K), sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim (SXT), and erythromycin (E), is currently circulating in cholera endemic countries of Asia and Africa (Finch et al., 1988; Faruque et al., 2007; Jain et al., 2011; Rashed et al., 2012; Dixit et al., 2014). Furthermore, genes conferring resistance to CIP and AZ have been shown to be transferred to V. cholerae via plasmids, gene cassettes, and mobile genetic elements with horizontal gene transfer mechanisms in environmental reservoir implicated in transforming sensitive bacteria to resistant (Kitaoka et al., 2011). Considering these phenotypic and genetic modifications that are reported, a study of 97 V. cholerae O1 isolates was undertaken to determine the antibiotic resistance/susceptibility status of V. cholerae O1 isolated from environmental samples and cholera cases in cholera endemic Mathbaria, Bangladesh.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains

In this study, a total of 97 V. cholerae O1 isolated from rectal swabs and surface water samples collected in the coastal villages of Mathbaria, Bangladesh, between June, 2010 and December, 2014, as a part of epidemiological surveillance conducted by the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B) were analyzed for antibiotic susceptibility and genotypic traits. Mathbaria is geographically adjacent to the Bay of Bengal, located ~165 km south-west of Dhaka city. Clinical isolates (n = 52) were obtained from rectal swabs of suspected cholera patients seeking treatment at the local health center during the cholera peak and off-peak season. Environmental isolates (n = 45) were obtained from water and plankton samples collected periodically at six different ponds and a river in the same area where the clinical samples were collected. The clinical and environmental samples were collected, transported, and subjected to bacteriological analysis for V. cholerae, following standard procedures (Alam et al., 2006a; Huq et al., 2012). Isolation and identification were performed according to standard methods (Alam et al., 2006a,b; Huq et al., 2012). All samples were collected according to protocols approved by institutional review boards at the Johns Hopkins University, University of Maryland (College Park, MD, USA), and ICDDR,B. Informed consent was obtained from the patients, and parents or legal guardians of the children who participated in this study. Genomic DNA was prepared from the presumptively identified V. cholerae isolates using the boiling lysis method of Park et al. (2013) and V. cholerae species-specific ompW PCR was done to confirm identity of the isolates (Nandi et al., 2000).

Serogrouping

The serogroups of the V. cholerae isolates were confirmed by a slide agglutination test using specific polyvalent antisera for V. cholerae O1 and O139. Isolates showing positive agglutination reaction with O1 antisera were tested further using a serotype-specific monoclonal antibody, i.e., Inaba and Ogawa (Alam et al., 2006b). The serogroups of these isolates were reconfirmed by multiplex PCR, targeting O1-(wbe) and O139-(wbf) specific O biosynthetic genes, together with the cholera toxin gene (ctxA; Hoshino et al., 1998).

Antimicrobial Susceptibility

Susceptibility to antimicrobials was determined by standard disc diffusion on Muller-Hinton agar (BD, USA) according to Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute guidelines for V. cholerae (CLSI, 2010a) and Enterobacteriaceae (CLSI, 2010b). Escherichia coli ATCC 25922 was used as a control for antimicrobial susceptibility. All strains of V. cholerae were tested for resistance to AM (10 μg), CIP (5 μg), C (30 μg), E (15 μg), K (30 μg), S (10 μg), TE (30 μg), nalidixic acid (NA, 30 μg), penicillin (P, 10 μg), and SXT (23.75 and 1.25 μg, respectively) using commercially available discs (BD BBL Sensi-Disc). Minimum inhibitory concentrations (MIC) of CIP and AZ were determined using E-test strips (bioMérieux-USA), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Cut-off levels for assessing resistance were determined following the CLSI document M45 guidelines (CLSI, 2010b).

PCR Assay

PCR assays were carried out to detect genes encoding accessory cholera enterotoxin (ace), zonula occludens toxin (zot), hemolysin (hlyA; Rivera et al., 2001), SXT-related integrase (intSXT; Hochhut et al., 2001) and biotype-specific (ET and CL) toxin coregulated pilus (tcpA; Rivera et al., 2001), phage-encoded repressor (rstR; Kimsey et al., 1998), and repeat in toxin (rtxC; Chow et al., 2001) using primers and conditions described previously. Double mismatch amplification mutation assay (DMAMA)-PCR was performed to identify three genotypes of the cholera toxin gene, i.e., ctxB1, ctxB3, and ctxB7, based on nucleotide substitution at position 58, 115, and 203 (Naha et al., 2012). V. cholerae O1 strains O395 (CL), N16961 (ET), and 2010EL-1786 were used as control for the PCR analysis. V. cholerae O1 isolates showing MIC for AZ ≥ 0.5 μg/mL were analyzed further for the macrolide resistance genes: erm(A), erm(B), and erm(C), that encode methylase; ere(A) or ere(B) encoding esterases; mph(A), mph(B), and mph(D) encoding phosphotransferases; and mef (A) and msr(A) encoding efflux pumps (Phuc Nguyen et al., 2009).

Results

Phenotypic and Geneotypic Characteristics

All 97 isolates produced colonies typical of V. cholerae on both taurocholate tellurite gelatin agar (TTGA) and thiosulfate citrate bile-salts sucrose (TCBS) agar. These isolates gave biochemical reactions characteristic of V. cholerae and reacted to polyvalent antibody specific for V. cholerae serogroup O1. Of 97 isolates, 89 gave positive agglutination with monovalent Ogawa antisera, while the remaining eight reacted positively with monovalent Inaba antisera. All isolates were serologically identified as V. cholerae O1. Notably, the serotype of 89 strains was determined to be Ogawa and eight to Inaba (Table 1).

Genomic DNA of all isolates (n = 97) amplified V. cholerae species-specific genes, namely ompW and O-antigen biosynthetic-wbe (O1) confirming identification as V. cholerae O1. None amplified the O-antigen biosynthetic-wbf (O139). As shown in Table 1, except for two isolates, all amplified the CTX-phage mediated genes ctxA, ace, and zot, suggesting 95 of the isolates were toxigenic V. cholerae O1. The PCR assay results also showed hlyA gene present in all isolates (Table 1). Of 97 V. cholerae O1, intSXT was identified in 95 isolates, while two lacked intSXT. All V. cholerae O1 isolates contained the ET biotype specific tcpA and rtxC, reflecting ET attributes. Among the 95 toxigenic V. cholerae O1 isolates, 90 possessed rstR of the ET biotype (rstRET), while the remaining five revealed CL biotype specific rstRCL. Unlike hybrid ET strains, none of the toxigenic isolates contained both rstRET and rstRCL. DMAMA-PCR detected cholera toxin gene of CL biotype (ctxB1) in 87 V. cholerae O1 isolates, while 8 had Orissa variant or Haiti variant cholera toxin (ctxB7; Table 1). Overall, the PCR results confirmed that 90 of the V. cholerae O1 isolates were atypical ET, possessing the rstRET and either ctxB1 or ctxB7 gene. Five toxigenic V. cholerae O1 possessing rstRCL and ctxB1 are designated as variant ET and their genetic attributes were similar to the Matlab variant (MJ1236) isolated in 1994 in Matlab, Bangladesh. As shown in Table 1, V. cholerae O1 variant ET was isolated from both clinical and environmental sources in Mathbaria, Bangladesh only in 2012. V. cholerae O1 atypical ET was associated with cholera cases that occurred during June, 2010, and December, 2014, in Mathbaria, Bangladesh and these strains were also isolated frequently from environmental sources (Table 1).

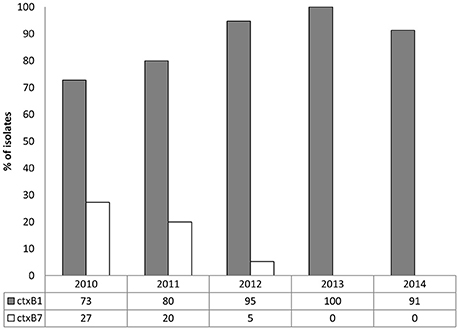

As shown in Figure 1, the CL type cholera toxin genotype, ctxB1, was predominant, having been detected in 73, 80, 95, 100, and 91% V. cholerae O1 isolates in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014, respectively. In contrast, Orissa, or Haiti variant cholera toxin genotype ctxB7 was found in 27, 20, and 5% isolates in 2010, 2011, and 2012, respectively. Remarkably, ctxB7 was not detected in V. cholerae O1 isolated in 2013 and thereafter (Table 1). Although, 9% of the V. cholerae O1 were non-toxigenic in 2014, ctxB1 was the only genotype prevailed among toxigenic isolates in 2013 and 2014.

Figure 1. Distribution of ctxB genotypes in 97 V. cholerae O1 from Mathbaria, Bangladesh isolated during 2010 and 2014. In both the clinical and environmental isolates, ctxB1 (gray bars) was predominant in each year. Although ctxB7 in the V. cholerae O1 isolates (white bars) was detected in relatively low percentage in 2010, 2011, and 2012, it was not detected in 2013 and 2014.

Antimicrobial Susceptibility

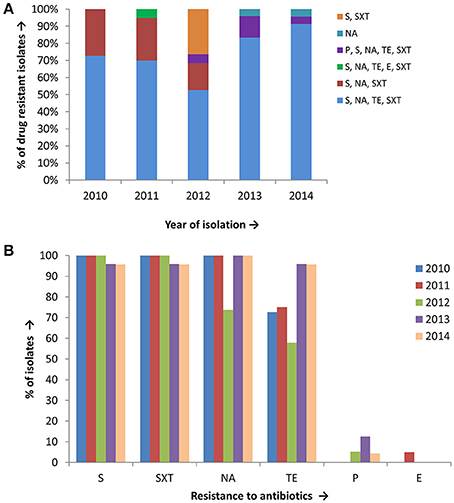

Antimicrobial susceptibility tests, using ten different antibiotics revealed that 93% of the total set of V. cholerae O1 isolates were MDR, i.e., resistant to at least three different antibiotics drugs (Table 1). As shown in Figure 2A, six different resistance profiles were observed, with a range of resistance to one to five antibiotics during 2010 and 2014. V. cholerae O1 showing resistance to S, NA, TE, and SXT was the dominant pattern (53–91%) each year between 2010 and 2014 (Figure 2A). Interestingly, resistance of V. cholerae O1 to P, S, NA, SXT, E, and TE varied during the years of the study period. As shown in Figure 2B, 100% of the V. cholerae O1 showed resistance to S and SXT in 2010, 2011, and 2012. However, S and SXT resistance fell to 96% the following 2 years, 2013 and 2014. The SXT-related integrase (intSXT) was detected in all isolates resistant to S and SXT, suggesting the SXT/R391 ICE mediated the resistance to S and SXT. Except for five of the V. cholerae O1 variant ET isolated in 2012, all were resistant to NA (Figure 2B), an indicator of reduced susceptibility to CIP. TE resistant V. cholerae O1 comprised 73, 75, 58, 96, and 96% in 2010, 2011, 2012, 2013, and 2014, respectively (Figure 2B). Of 97 V. cholerae O1, five showed resistance to P during 2012 and 2014, while only one isolate showed resistance to E in 2011. Notably, all 97 V. cholerae O1 isolates were uniformly sensitivity to AM, CIP, C, and K.

Figure 2. (A) Drug resistance profile of 97 V. cholerae O1 isolates from Mathbaria, Bangladesh. Six different resistance profiles were observed for V. cholerae O1 isolated during 2010 and 2014, of which four profiles were multidrug resistance: resistance to S, NA, TE, and SXT was most abundant and predominant in V. cholerae O1 (B) V. cholerae O1 isolated during 2010 and 2014 showing resistance to six different drugs. The majority of the isolates were resistant to S, SXT, TE, and NA, while only a few were resistant to P and E.

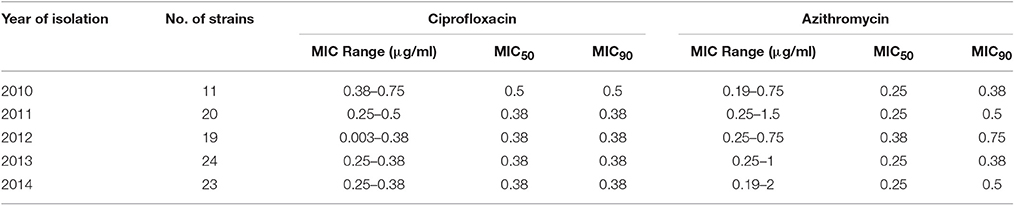

MIC of Ciprofloxacin

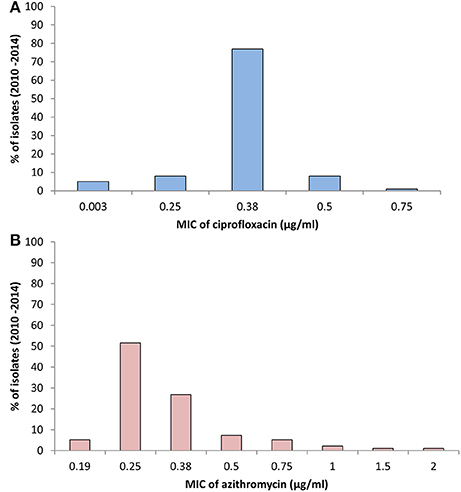

The MIC of CIP of all 97 V. cholerae O1 isolates was determined to be 0.003–0.75 μg/ml during 2010 and 2014. As shown in Table 2, MIC50 and MIC90 of CIP was 0.5 μg/ml in 2010. However, the MIC50 and MIC90 were 0.38 μg/ml in 2011, maintained consistently over the following years until 2014. Five of the V. cholerae O1 variant ET isolated in 2012 had an MIC for CIP of 0.003 μg/ml. Only 1% of the total set of strains had the highest MIC, 0.75 μg/ml, while 77% had an MIC of 0.38 μg/ml (Figure 3A).

Table 2. Minimum inhibitory concentration of ciprofloxacin and azithromycin for 97 V. cholerae O1 isolates.

Figure 3. (A) MIC of CIP for 97 V. cholerae O1 isolates from Mathbaria, Bangladesh. The MIC range for CIP was 0.003–0.75 μg/ml. The majority of the isolates showed MIC 0.38 μg/ml, while a low percentage had MIC of 0.5 and 0.75 μg/ml. (B) MIC of AZ for 97 V. cholerae O1 isolates from Mathbaria, Bangladesh. The range of MIC for AZ was 0.19–2 μg/ml. A relatively low percent of the isolates had a MIC of 2 μg/ml, the sensitivity-borderline for V. cholerae.

MIC of Azithromycin

The MIC of AZ for 97 of the V. cholerae O1 isolates was 0.19–2.00 μg/ml. As shown in Table 2, except for the 2012 isolates, MIC50 was consistently 0.25 μg/ml. Year-wise data revealed that the lowest MIC90 was 0.38 μg/ml in 2010 and 2013 and increased to 0.5 and 0.75 μg/ml in 2011 and 2012, respectively (Table 2). As shown in Figure 3B, 52 and 27% of the total isolates had MIC 0.25 and 0.38 μg/ml, respectively. The highest MIC of 2.00 μg/ml occurred in 1% of the V. cholerae O1 isolates (Figure 3B). Sixteen (16%) V. cholerae O1 with an MIC of ≥0.5 μg/ml were analyzed further for 10 macrolide resistance genes. PCR assay results revealed that none of the isolates contained the following macrolide resistance genes: erm(A); erm(B); erm(C); ere(A); ere(B); mph(A); mph(B); mph(D); mef (A); and msr(A).

Discussion

Endemic cholera occurs in many geographic locations of Bangladesh each year, with two distinct seasonal peaks, one in the spring (March–May) and the other in the fall (September–November; Emch et al., 2008; Akanda et al., 2013). The Ganges delta region of the Bay of Bengal is a well-known reservoir of V. cholerae where it has established residence for centuries (Sack et al., 2004). Historically, this part of Asia has been affected severely by both CL and ET cholera during the seventh pandemic up to 1991, prior to the disappearance of CL strains from Bangladesh (Siddique and Cash, 2014). Epidemiological data suggest that most of the recorded epidemics struck the coastal populations first (Jutla et al., 2010), a pattern typical of recent epidemics in Bangladesh as well before reaching inland (Akanda et al., 2013). Since the beginning of the ongoing seventh pandemic, V. cholerae O1 strains have undergone multiple genetic changes, with the evolution of new clones and also atypical ET strains (Chun et al., 2009; Safa et al., 2010; Kim et al., 2014). Results of this study show association of V. cholerae O1 atypical ET with cholera occurring in the coastal areas of Mathbaria, Bangladesh during 2010 and 2014. Since 2001, atypical ET emerged as the major cause of cholera in Bangladesh superseding prototype ET, although isolated a decade earlier in the 1990s in Matlab, Bangladesh (Nair et al., 2006; Safa et al., 2006). This transition was considered remarkable for cholera epidemiology, mainly because atypical ET strains possessing CL cholera toxin (ctxB1) cause a more severe cholera than prototype ET (Siddique et al., 2010). In recent years, several non-synonymous mutations have been detected in the ctxB gene, although, correlation of these mutations with clinical outcomes of the disease remains to be clarified (Kim et al., 2015). The ctxB7 genotypes have an amino acid substitution at position 20 [histidine (H)→asparagine (N)] first reported in a cholera outbreak in Orissa, India (Kumar et al., 2009). Later, V. cholerae O1 carrying ctxB7 was determined to be associated with cholera in Haiti, Zimbabwe, India, Bangladesh, Nepal, Nigeria, and Cameroon (Quilici et al., 2010; Chin et al., 2011; Hasan et al., 2012; Rashed et al., 2012; Marin et al., 2013; Dixit et al., 2014). In Mathbaria, Bangladesh, ctxB1 was consistently dominant to ctxB7 during 2010 and 2012, whereas ctxB7 was not detected thereafter. The alternating dominance of ctxB1 and ctxB7, i.e., one genotype disappearing transiently for 2 or 3 years and reappearing in the following years with remarkable dominance, was previously observed in V. cholerae O1 causing cholera in Kolkata, India, and Dhaka, Bangladesh (Rashed et al., 2012; Mukhopadhyay et al., 2014; Rashid et al., 2016).

Bacterial resistance to antimicrobial drugs is a serious public health concern worldwide and antibiotic therapy constitutes a major component of the clinical management of cholera. An antimicrobial drug considered to be a successful therapeutic agent may not be successful in the future and notably so if V. cholerae acquires resistance to drugs of choice. Resistance can arise from single or multiple mutations in target genes or by acquisition of resistance genes carried by mobile genetic elements, such as plasmids, transposons, integrons, and ICEs (Kitaoka et al., 2011). Prior to the use of macrolides and fluoroquinolone drugs for treatment of cholera, TE was the drug of choice, except for young children and pregnant women (Greenough et al., 1964; Sack et al., 2004). However, tetracycline was limited as a drug of choice because of the emergence of resistant V. cholerae O1 to AMP, KN, S, and SXT, as well as TE, in Asia and Africa (Mhalu et al., 1979; Glass et al., 1980). In this study, 93% of the V. cholerae O1 strains tested proved to be multidrug resistant, mostly resistant to S, NA, TE, and SXT. Despite having spatio-temporal variation in the resistance profile, the multidrug resistant V. cholerae O1 was consistently identified as the etiological agent of cholera epidemics in Asia and Africa, and most recently in Haiti (Mhalu et al., 1979; Glass et al., 1980; Dalsgaard et al., 2001; Jain et al., 2011; Sjölund-Karlsson et al., 2011; Rashed et al., 2012; Tran et al., 2012). A recent study from China reported that the prevalence of multidrug resistant V. cholerae O1 strains has been increased rapidly since 1993, showing resistance to AMP, NA, TE, and SXT (Wang et al., 2012). The same study also revealed relatively low number of V. cholerae O1 has reduced susceptibility to azithromycin in China that were isolated only in 1965, 1998, and 2006 (Wang et al., 2012). Drug resistant markers, such as SXT ICE, class 1 integrons, and low molecular weight plasmids are commonly found in multidrug resistant V. cholerae O1 (Kitaoka et al., 2011). Interestingly, a recent study reported the presence of a transmissible multidrug resistant plasmid (IncA/C) in Haitian V. cholerae isolates possessing several multidrug resistance determinants, i.e., aac(3)-IIa, blaCMY−2, blaCTX−M−2, bla-TEM−1, dfrA15, mphA, sul1, tetA, floR, strAB, and sul2 (Folster et al., 2014).

Among the fluoroquinolone antibiotics, only CIP has been recommended by the Pan American Health Organization and International Centre for Diarrhoeal Disease Research, Bangladesh for treatment of cholera. Although, V. cholerae O1 has not shown complete resistance to CIP, current epidemiological data confirm a gradual increase in the MIC of CIP has been occurring (Khan et al., 2015). V. cholerae O1 with reduced susceptibility to CIP has been reported in different parts of the world and appears to be disseminating globally (Islam et al., 2009; Quilici et al., 2010; Sjölund-Karlsson et al., 2011; Tran et al., 2012; Khan et al., 2015). A recent study showed that the MIC of CIP for V. cholerae O1 has increased 45-fold in a 19 year time-span in Bangladesh. That is, the MIC was 0.010 μg/ml in 1994 and has increased dramatically to 0.475 μg/ml in 2012 (Khan et al., 2015). In our study, 95% of the V. cholerae O1 isolated in Mathbaria, Bangladesh, showed reduced susceptibility to CIP during 2010 and 2014. Notably, the CIP MIC50 and MIC90 did not show rapid change in the 5 year of our study period and the MIC remained below the susceptibility breakpoint (≤ 1 μg/ml) according to CLSI guidelines (CLSI, 2010a). It is important to note that all V. cholerae O1 atypical ET isolates were resistant to NA, another drug in the quinolone group. V. cholerae O1 showing resistance to NA is an indicator of reduced susceptibility to CIP (Khan et al., 2015). The genetic basis of quinolone drug resistance in V. cholerae is the accumulation of mutations in gyrA (83Ser → Ile) and parC (85Ser → Leu) (Kitaoka et al., 2011). These point mutations have been detected in currently circulating V. cholerae O1 associated with cholera epidemics in Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Nigeria, Cameroon, and Haiti (Quilici et al., 2010; Sjölund-Karlsson et al., 2011; Hasan et al., 2012; Dixit et al., 2014).

Frequent use of a specific group of antibiotics for treatment of cholera over a prolonged period will increase the likelihood of bacterial resistance. Global dissemination of V. cholerae O1 with reduced CIP sensitivity raises a serious concern for clinical management of cholera in countries where the disease is endemic. Results of a recent study showed that single-dose CIP used to treat cholera was not as effective as it was in the past because of the emergence of V. cholerae O1 less susceptible to CIP and NA (Khan et al., 2015). Single dose AZ has been introduced as an alternative treatment for cholera in India and Bangladesh. However, the sensitivity breakpoint guidelines for the AZ disc diffusion assay has not yet been published by the CLSI for V. cholerae (CLSI, 2010a). In this study, all V. cholerae O1 isolates showed a reduced susceptibility to AZ and the MIC for 1% of the isolates was at the sensitivity breakpoint borderline (≤2 μg/ml). Interestingly, none of the V. cholerae O1 (AZ MIC ≥ 0.5 μg/ml) possessed macrolide resistance genes that have been reported for the Enterobacteriaceae (Phuc Nguyen et al., 2009). Although at a relatively low incidence, E and AZ resistant V. cholerae O1 have been reported in Bangladesh and India (Faruque et al., 2007; Bhattacharya et al., 2012).

Reduced susceptibility to CIP and AZ is alarming for cholera-endemic countries of Asia and Africa. Environmental factors trigger seasonal cholera in endemic countries including Bangladesh, but cholera cases have occurred in other countries immediately after a devastating natural calamity, e.g., floods, earthquakes, typhoons, and cyclones. The morbidity and mortality rates of cholera, which were under control for several decades, can be expected to increase if V. cholerae O1 acquires full resistance to currently used drugs. Considering the global burden of cholera, it is important that the appropriate antibiotic and appropriate concentration be used to treat cholera. Indiscriminate use of antibiotics, for example in agriculture and animal husbandry for disease management should be controlled to assure continued success of antibiotic for the treatment of disease in humans, including cholera. Therefore, global monitoring of antimicrobial sensitivity of V. cholerae O1 is essential to assess clinical efficacy of drugs worldwide.

Author Contributions

SR and AH contributed to the design of the study. SR also performed all research works in the laboratory, analyzed data, and wrote the manuscript. AS and MS collected clinical and environmental samples from the field area and processed all samples at ICDDR,B. NH, MA, MH, RS, RC, and AH contributed to revising the manuscript critically for important intellectual content. All authors discussed, read, and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) grant no. 2RO1A1039129-11A2 from the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We thank the study participants and all the members of MA's group at the International Centre for Diarrheal Disease Research, Bangladesh (ICDDR,B) for their valuable and relentless clinical and environmental sampling throughout the years. The ICDDR,B is also thankful to the governments of Australia, Bangladesh, Canada, Sweden and the UK for providing core/unrestricted support.

References

Akanda, A. S., Jutla, A. S., Gute, D. M., Sack, R. B., Alam, M., Huq, A., et al. (2013). Population vulnerability to biannual cholera outbreaks and associated macro-scale drivers in the Bengal Delta. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 89, 950–959. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.12-0492

Alam, M., Hasan, N. A., Sadique, A., Bhuiyan, N. A., Ahmed, K. U., Nusrin, S., et al. (2006a). Seasonal cholera caused by Vibrio cholerae serogroups O1 and O139 in the coastal aquatic environment of Bangladesh. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 4096–4104. doi: 10.1128/AEM.00066-06

Alam, M., Sultana, M., Nair, G. B., Sack, R. B., Sack, D. A., Siddique, A. K., et al. (2006b). Toxigenic Vibrio cholerae in the aquatic environment of Mathbaria, Bangladesh. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 72, 2849–2855. doi: 10.1128/AEM.72.4.2849-2855.2006

Albert, M. J., Siddique, A. K., Islam, M. S., Faruque, A. S., Ansaruzzaman, M., Faruque, S. M., et al. (1993). Large outbreak of clinical cholera due to Vibrio cholerae non-O1 in Bangladesh. Lancet 341, 704. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90481-U

Ali, M., Lopez, A. L., You, Y. A., Kim, Y. E., Sah, B., Maskery, B., et al. (2012). The global burden of cholera. Bull. World Health Organ. 90, 209–218A. doi: 10.2471/BLT.11.093427

Andersson, D. I., and Hughes, D. (2014). Microbiological effects of sublethal levels of antibiotics. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 12, 465–478. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3270

Bhattacharya, D., Sayi, D. S., Thamizhmani, R., Bhattacharjee, H., Bharadwaj, A. P., Roy, A., et al. (2012). Emergence of multidrug-resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor in Port Blair, India. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 86, 1015–1017. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.2012.11-0327

Chin, C. S., Sorenson, J., Harris, J. B., Robins, W. P., Charles, R. C., Jean-Charles, R. R., et al. (2011). The origin of the Haitian cholera outbreak strain. N. Engl. J. Med. 364, 33–42. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1012928

Chow, K. H., Ng, T. K., Yuen, K. Y., and Yam, W. C. (2001). Detection of RTX toxin gene in Vibrio cholerae by PCR. J. Clin. Microbiol. 39, 2594–2597. doi: 10.1128/JCM.39.7.2594-2597.2001

Chun, J., Grim, C. J., Hasan, N. A., Lee, J. H., Choi, S. Y., Haley, B. J., et al. (2009). Comparative genomics reveals mechanism for short-term and long-term clonal transitions in pandemic Vibrio cholerae. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 106, 15442–15447. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0907787106

CLSI (2010a). Methods for Antimicrobial Dilution and Disk Susceptibility Testing of Infrequently Isolated or Fastidious Bacteria; Approved Guideline, 2nd Edn. CLSI document M45-A2. Wayne, PA: CLSI.

CLSI (2010b). Performance Standards for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing; Twentieth Informational Supplement. CLSI document M100-S20. Wayne, PA: CLSI.

Dalsgaard, A., Forslund, A., Sandvang, D., Arntzen, L., and Keddy, K. (2001). Vibrio cholerae O1 outbreak isolates in Mozambique and South Africa in 1998 are multiple-drug resistant, contain the SXT element and the aadA2 gene located on class 1 integrons. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 48, 827–838. doi: 10.1093/jac/48.6.827

Devault, A. M., Golding, G. B., Waglechner, N., Enk, J. M., Kuch, M., Tien, J. H., et al. (2014). Second-pandemic strain of Vibrio cholerae from the Philadelphia cholera outbreak of 1849. N. Engl. J. Med. 370, 334–340. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1308663

Dixit, S. M., Johura, F. T., Manandhar, S., Sadique, A., Rajbhandari, R. M., Mannan, S. B., et al. (2014). Cholera outbreaks (2012) in three districts of Nepal reveal clonal transmission of multi-drug resistant Vibrio cholerae O1. BMC Infect. Dis. 14:392. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-14-392

Emch, M., Feldacker, C., Islam, M. S., and Ali, M. (2008). Seasonality of cholera from 1974 to 2005: a review of global patterns. Int. J. Health Geogr. 7:31. doi: 10.1186/1476-072X-7-31

Faruque, A. S., Alam, K., Malek, M. A., Khan, M. G., Ahmed, S., Saha, D., et al. (2007). Emergence of multidrug-resistant strain of Vibrio cholerae O1 in Bangladesh and reversal of their susceptibility to tetracycline after two years. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 25, 241–243.

Finch, M. J., Morris, J. G. Jr., Kaviti, J., Kagwanja, W., and Levine, M. M. (1988). Epidemiology of antimicrobial resistant cholera in Kenya and East Africa. Am. J. Trop. Med. Hyg. 39, 484–490.

Folster, J. P., Katz, L., McCullough, A., Parsons, M. B., Knipe, K., Sammons, S. A., et al. (2014). Multidrug-resistant IncA/C plasmid in Vibrio cholerae from Haiti. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 20, 1951–1953. doi: 10.3201/eid2011.140889

Garg, P., Sinha, S., Chakraborty, R., Bhattacharya, S. K., Nair, G. B., Ramamurthy, T., et al. (2001). Emergence of fluoroquinolone-resistant strains of Vibrio cholerae O1 biotype El Tor among hospitalized patients with cholera in Calcutta, India. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 1605–1606. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.5.1605-1606.2001

Glass, R. I., Huq, I., Alim, A. R., and Yunus, M. (1980). Emergence of multiply antibiotic-resistant Vibrio cholerae in Bangladesh. J. Infect. Dis. 142, 939–942. doi: 10.1093/infdis/142.6.939

Greenough, W. B. III., Gordon, R. S. Jr., Rosenberg, I. S., Davies, B. I., and Benenson, A. S. (1964). Tetracycline in the treatment of Cholera. Lancet 1, 355–357. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(64)92099-9

Harris, J. B., Larocque, R. C., Qadri, F., Ryan, E. T., and Calderwood, S. B. (2012). Cholera. Lancet 379, 2466–2476. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(12)60436-X

Hasan, N. A., Choi, S. Y., Eppinger, M., Clark, P. W., Chen, A., Alam, M., et al. (2012). Genomic diversity of 2010 Haitian cholera outbreak strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 109, E2010–E2017. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1207359109

Hochhut, B., Lotfi, Y., Mazel, D., Faruque, S. M., Woodgate, R., and Waldor, M. K. (2001). Molecular analysis of antibiotic resistance gene clusters in Vibrio cholerae O139 and O1 SXT constins. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 45, 2991–3000. doi: 10.1128/AAC.45.11.2991-3000.2001

Hoshino, K., Yamasaki, S., Mukhopadhyay, A. K., Chakraborty, S., Basu, A., Bhattacharya, S. K., et al. (1998). Development and evaluation of a multiplex PCR assay for rapid detection of toxigenic Vibrio cholerae O1 and O139. FEMS Immunol. Med. Microbiol. 20, 201–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1998.tb01128.x

Huq, A., Haley, B. J., Taviani, E., Chen, A., Hasan, N. A., and Colwell, R. R. (2012). Detection, isolation, and identification of Vibrio cholerae from the environment. Curr. Protoc. Microbiol. Chapter 6, Unit6A.5. doi: 10.1002/9780471729259.mc06a05s26

Islam, M. S., Midzi, S. M., Charimari, L., Cravioto, A., and Endtz, H. P. (2009). Susceptibility to fluoroquinolones of Vibrio cholerae O1 isolated from diarrheal patients in Zimbabwe. JAMA 302, 2321–2322. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.1750

Jain, M., Goel, A. K., Bhattacharya, P., Ghatole, M., and Kamboj, D. V. (2011). Multidrug resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor carrying classical ctxB allele involved in a cholera outbreak in South Western India. Acta Trop. 117, 152–156. doi: 10.1016/j.actatropica.2010.12.002

Jutla, A. S., Akanda, A. S., and Islam, S. (2010). Tracking cholera in coastal regions using satellite observations. J. Am. Water Res. Assoc. 46, 651–662. doi: 10.1111/j.1752-1688.2010.00448.x

Khan, W. A., Saha, D., Ahmed, S., Salam, M. A., and Bennish, M. L. (2015). Efficacy of Ciprofloxacin for treatment of cholera associated with diminished susceptibility to ciprofloxacin to Vibrio cholerae O1. PLoS ONE 10:e0134921. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0134921

Kim, E. J., Lee, C. H., Nair, G. B., and Kim, D. W. (2015). Whole-genome sequence comparisons reveal the evolution of Vibrio cholerae O1. Trends Microbiol. 23, 479–489. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.03.010

Kim, E. J., Lee, D., Moon, S. H., Lee, C. H., Kim, S. J., Lee, J. H., et al. (2014). Molecular insights into the evolutionary pathway of Vibrio cholerae O1 atypical El Tor variants. PLoS Pathog. 10:e1004384. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1004384

Kimsey, H. H., Nair, G. B., Ghosh, A., and Waldor, M. K. (1998). Diverse CTXphis and evolution of new pathogenic Vibrio cholerae. Lancet 352, 457–458. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)79193-5

Kitaoka, M., Miyata, S. T., Unterweger, D., and Pukatzki, S. (2011). Antibiotic resistance mechanisms of Vibrio cholerae. J. Med. Microbiol. 60, 397–407. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.023051-0

Kumar, P., Jain, M., Goel, A. K., Bhadauria, S., Sharma, S. K., Kamboj, D. V., et al. (2009). A large cholera outbreak due to a new cholera toxin variant of the Vibrio cholerae O1 El Tor biotype in Orissa, Eastern India. J. Med. Microbiol. 58, 234–238. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.002089-0

Kumar, P., Mishra, D. K., Deshmukh, D. G., Jain, M., Zade, A. M., Ingole, K. V., et al. (2014). Haitian variant ctxB producing Vibrio cholerae O1 with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin is persistent in Yavatmal, Maharashtra, India, after causing a cholera outbreak. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 20, O292–O293. doi: 10.1111/1469-0691.12393

Laxminarayan, R., Duse, A., Wattal, C., Zaidi, A. K., Wertheim, H. F., Sumpradit, N., et al. (2013). Antibiotic resistance-the need for global solutions. Lancet Infect. Dis. 13, 1057–1098. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70318-9

Marin, M. A., Thompson, C. C., Freitas, F. S., Fonseca, E. L., Aboderin, A. O., Zailani, S. B., et al. (2013). Cholera outbreaks in Nigeria are associated with multidrug resistant atypical El Tor and non-O1/non-O139 Vibrio cholerae. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 7:e2049. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0002049

Mhalu, F. S., Mmari, P. W., and Ijumba, J. (1979). Rapid emergence of El Tor Vibrio cholerae resistant to antimicrobial agents during first six months of fourth cholera epidemic in Tanzania. Lancet 1, 345–347. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(79)92889-7

Mukhopadhyay, A. K., Takeda, Y., and Balakrish Nair, G. (2014). Cholera outbreaks in the El Tor biotype era and the impact of the new El Tor variants. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 379, 17–47. doi: 10.1007/82_2014_363

Mutreja, A., Kim, D. W., Thomson, N. R., Connor, T. R., Lee, J. H., Kariuki, S., et al. (2011). Evidence for several waves of global transmission in the seventh cholera pandemic. Nature 477, 462–465. doi: 10.1038/nature10392

Naha, A., Pazhani, G. P., Ganguly, M., Ghosh, S., Ramamurthy, T., Nandy, R. K., et al. (2012). Development and evaluation of a PCR Assay for tracking the emergence and dissemination of haitian variant ctxB in Vibrio cholerae O1 strains isolated from Kolkata, India. J. Clin. Microbiol. 50, 1733–1736. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00387-12

Nair, G. B., Qadri, F., Holmgren, J., Svennerholm, A. M., Safa, A., Bhuiyan, N. A., et al. (2006). Cholera due to altered El Tor strains of Vibrio cholerae O1 in Bangladesh. J. Clin. Microbiol. 44, 4211–4213. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01304-06

Nandi, B., Nandy, R. K., Mukhopadhyay, S., Nair, G. B., Shimada, T., and Ghose, A. C. (2000). Rapid method for species-specific identification of Vibrio cholerae using primers targeted to the gene of outer membrane protein OmpW. J. Clin. Microbiol. 38, 4145–4151.

Park, J. Y., Jeon, S., Kim, J. Y., Park, M., and Kim, S. (2013). Multiplex real-time polymerase chain reaction assays for simultaneous detection of Vibrio cholerae, Vibrio parahaemolyticus, and Vibrio vulnificus. Osong Public Health Res. Perspect 4, 133–139. doi: 10.1016/j.phrp.2013.04.004

Phuc Nguyen, M. C., Woerther, P. L., Bouvet, M., Andremont, A., Leclercq, R., and Canu, A. (2009). Escherichia coli as reservoir for macrolide resistance genes. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 15, 1648–1650. doi: 10.3201/eid1510.090696

Quilici, M. L., Massenet, D., Gake, B., Bwalki, B., and Olson, D. M. (2010). Vibrio cholerae O1 variant with reduced susceptibility to ciprofloxacin, Western Africa. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 16, 1804–1805. doi: 10.3201/eid1611.100568

Ramamurthy, T., Garg, S., Sharma, R., Bhattacharya, S. K., Nair, G. B., Shimada, T., et al. (1993). Emergence of novel strain of Vibrio cholerae with epidemic potential in southern and eastern India. Lancet 341, 703–704. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90480-5

Rashed, S. M., Mannan, S. B., Johura, F. T., Islam, M. T., Sadique, A., Watanabe, H., et al. (2012). Genetic characteristics of drug-resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 causing endemic cholera in Dhaka, 2006-2011. J. Med. Microbiol. 61, 1736–1745. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.049635-0

Rashid, M.-U., Rashed, S. M., Islam, T., Johura, F.-T., Watanabe, H., Ohnishi, M., et al. (2016). CtxB1 outcompetes CtxB7 in Vibrio cholerae O1, Bangladesh. J. Med. Microbiol. 65, 101–103. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.000190

Rivera, I. N., Chun, J., Huq, A., Sack, R. B., and Colwell, R. R. (2001). Genotypes associated with virulence in environmental isolates of Vibrio cholerae. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 67, 2421–2429. doi: 10.1128/AEM.67.6.2421-2429.2001

Sack, D. A., Sack, R. B., Nair, G. B., and Siddique, A. K. (2004). Cholera. Lancet 363, 223–233. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)15328-7

Safa, A., Bhuyian, N. A., Nusrin, S., Ansaruzzaman, M., Alam, M., Hamabata, T., et al. (2006). Genetic characteristics of Matlab variants of Vibrio cholerae O1 that are hybrids between classical and El Tor biotypes. J. Med. Microbiol. 55, 1563–1569. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.46689-0

Safa, A., Nair, G. B., and Kong, R. Y. (2010). Evolution of new variants of Vibrio cholerae O1. Trends Microbiol. 18, 46–54. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2009.10.003

Siddique, A. K., and Cash, R. (2014). Cholera outbreaks in the classical biotype era. Curr. Top. Microbiol. Immunol. 379, 1–16. doi: 10.1007/82_2013_361

Siddique, A. K., Nair, G. B., Alam, M., Sack, D. A., Huq, A., Nizam, A., et al. (2010). El Tor cholera with severe disease: a new threat to Asia and beyond. Epidemiol. Infect. 138, 347–352. doi: 10.1017/S0950268809990550

Sjölund-Karlsson, M., Reimer, A., Folster, J. P., Walker, M., Dahourou, G. A., Batra, D. G., et al. (2011). Drug-resistance mechanisms in Vibrio cholerae O1 outbreak strain, Haiti, 2010. Emerg. Infect. Dis. 17, 2151–2154. doi: 10.3201/eid1711.110720

Tran, H. D., Alam, M., Trung, N. V., Kinh, N. V., Nguyen, H. H., Pham, V. C., et al. (2012). Multi-drug resistant Vibrio cholerae O1 variant El Tor isolated in northern Vietnam between 2007 and 2010. J. Med. Microbiol. 61, 431–437. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.034744-0

Waldor, M. K., Tschäpe, H., and Mekalanos, J. J. (1996). A new type of conjugative transposon encodes resistance to sulfamethoxazole, trimethoprim, and streptomycin in Vibrio cholerae O139. J. Bacteriol. 178, 4157–4165. doi: 10.1128/jb.178.14.4157-4165.1996

Keywords: Vibrio cholerae, El Tor, antibiotic resistance, reduced susceptibility, ciprofloxacin, azithromycin

Citation: Rashed SM, Hasan NA, Alam M, Sadique A, Sultana M, Hoq MM, Sack RB, Colwell RR and Huq A (2017) Vibrio cholerae O1 with Reduced Susceptibility to Ciprofloxacin and Azithromycin Isolated from a Rural Coastal Area of Bangladesh. Front. Microbiol. 8:252. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2017.00252

Received: 29 December 2016; Accepted: 06 February 2017;

Published: 21 February 2017.

Edited by:

Learn-Han Lee, Monash University Malaysia Campus, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Durg Vijai Singh, Institute of Life Sciences, IndiaHaijian Zhou, Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention, China

Hongxia Wang, University of Alabama at Birmingham, USA

M. Jahangir Alam, University of Houston, USA

Copyright © 2017 Rashed, Hasan, Alam, Sadique, Sultana, Hoq, Sack, Colwell and Huq. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anwar Huq, aHVxYW53YXJAZ21haWwuY29t

Shah M. Rashed

Shah M. Rashed Nur A. Hasan2,3

Nur A. Hasan2,3 Munirul Alam

Munirul Alam Marzia Sultana

Marzia Sultana Md. Mozammel Hoq

Md. Mozammel Hoq Rita R. Colwell

Rita R. Colwell Anwar Huq

Anwar Huq