- 1Department of Plant Pathology, EXIM Bank Agricultural University, Chapainawabganj, Bangladesh

- 2Department of Biotechnology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University, Gazipur, Bangladesh

- 3Department of Plant Pathology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University, Gazipur, Bangladesh

Plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) are the rhizosphere bacteria that may be utilized to augment plant growth and suppress plant diseases. The objectives of this study were to identify and characterize PGPR indigenous to cucumber rhizosphere in Bangladesh, and to evaluate their ability to suppress Phytophthora crown rot in cucumber. A total of 66 isolates were isolated, out of which 10 (PPB1, PPB2, PPB3, PPB4, PPB5, PPB8, PPB9, PPB10, PPB11, and PPB12) were selected based on their in vitro plant growth promoting attributes and antagonism of phytopathogens. Phylogenetic analysis of 16S rRNA sequences identified these isolates as new strains of Pseudomonas stutzeri, Bacillus subtilis, Stenotrophomonas maltophilia, and Bacillus amyloliquefaciens. The selected isolates produced high levels (26.78–51.28 μg mL-1) of indole-3-acetic acid, while significant acetylene reduction activities (1.79–4.9 μmole C2H4 mg-1 protein h-1) were observed in eight isolates. Cucumber plants grown from seeds that were treated with these PGPR strains displayed significantly higher levels of germination, seedling vigour, growth, and N content in root and shoot tissue compared to non-treated control plants. All selected isolates were able to successfully colonize the cucumber roots. Moreover, treating cucumber seeds with these isolates significantly suppressed Phytophthora crown rot caused by Phytophthora capsici, and characteristic morphological alterations in P. capsici hyphae that grew toward PGPR colonies were observed. Since these PGPR inoculants exhibited multiple traits beneficial to the host plants, they may be applied in the development of new, safe, and effective seed treatments as an alternative to chemical fungicides.

Introduction

The cucumber (Cucumis sativus) is one of the most widely grown vegetable crops in the world, and is particularly prevalent on the Indian sub-continent. This crop is prone to massive attacks by Phytophthora capsici that causes crown rot and blight (Kim et al., 2008; Maleki et al., 2011). P. capsici infects susceptible hosts throughout the growing season at any growth stage, and causes yield losses as high as 100% (Lee et al., 2001). This pathogen has a wide host range with more than 50 plant species including Cucurbitaceae, Leguminosae, and Solanaceae (Hausbeck and Lamour, 2004). Although fungicides can control the disease, their use is detrimental to the surrounding environment and to the viability and survival of beneficial rhizosphere microbes (Carson et al., 1962; Hussain et al., 2009; Heckel, 2012). Furthermore, the growing cost of pesticides and the consumer demand for pesticide-free food have led to a search for substitutes for these products. Thus, there has been a need to find effective alternatives to costly and environmentally degrading synthetic pesticides.

Rhizobacteria that benefit plants by stimulating growth and suppressing disease are referred to as plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR; Kloepper et al., 1980). PGPR have been tested as biocontrol agents for suppression of plant diseases (Gerhardson, 2002), and also as inducers of disease resistance in plants (Cattelan et al., 1999; Bargabus et al., 2002; Bais et al., 2004). In particular, strains of Pseudomonas, Stenotrophomonas, and Bacillus have been successfully used in attempts to control plant pathogens and increase plant growth (Bais et al., 2004; Idris et al., 2007; Liu et al., 2007; Messiha et al., 2007; Chen et al., 2009; El-Sayed et al., 2014). The widely recognized mechanisms of plant growth promotion by PGPR are production of phytohormones, diazotrophic fixation of nitrogen, and solubilization of phosphate. Mechanisms of biocontrol action include competition with phytopathogens for an ecological niche or substrate, as well as production of inhibitory compounds and hydrolytic enzymes that are often active against a broad spectrum of phytopathogens (Zhang and Yuen, 2000; Manjula et al., 2004; Haas and Défago, 2005; Stein, 2005; Detry et al., 2006; Konsoula and Liakopoulou-Kyriakides, 2006; Cazorla et al., 2007).

Many PGPR have been shown to reduce Phytophthora crown rot occurrence on various plants. Ahmed et al. (2003) demonstrated in vitro suppression of P. capsici by bacterial isolates from the aerial part and rhizosphere of sweet pepper. An endophytic bacterium isolated from black pepper stem and roots, B. megaterium IISRBP17 suppressed P. capsici on black pepper in greenhouse assays (Aravind et al., 2009). Zhang et al. (2010) demonstrated that PGPR strains used separately or in combinations had the potential to suppress Phytophthora blight on squash in the greenhouse. Shirzad et al. (2012) reported that some fluorescent pseudomonads isolated from different fields of East and West Azarbaijan and Ardebil provinces of Iran exhibited strong antifungal activity against P. drechsleri and controlled crown and root rot of cucumber caused by the pathogen. However, little is known about PGPRs with the potential to suppress crown rot caused by P. capsici on cucumber. Furthermore, the plant-growth-promoting and biocontrol efficacy of PGPR often depend upon the rhizosphere competence of the microbial inoculants (Lugtenberg and Kamilova, 2009). Rhizosphere competence refers to the survival and colonization potential of PGPR (Bulgarelli et al., 2013), and is thought to be highest for each PGPR strain when associated with its preferred host plant. This to some extent explains why some PGPR strains exhibiting promise as biocontrol agents in vitro have variable biocontrol efficacy in the rhizosphere of a given crop under a given set of conditions. The identification and characterization of PGPR populations indigenous to cucumber rhizospheres is therefore critical to discovery of strains that can be utilized to improve growth and Phytophthora crown rot suppression in cucumber. The objectives of the present study were to isolate bacterial strains from the cucumber rhizosphere, to characterize these isolates on the basis of morphological and physiological attributes as well as by 16S rRNA sequence analysis, and to assess the plant growth promoting effects of these isolates in vivo and their ability to suppress Phytophthora crown rot in cucumber plants. To our knowledge, this is the first report of PGPR reducing P. capsici infection on cucumber.

Materials and Methods

The Study Site

The experimental site was located at the Field Laboratory of the Department of Plant Pathology, Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University (BSMRAU), Gazipur, Bangladesh. The location of the site is at 24.09° N latitude and 90.25° E longitude with an elevation of 2–8 m. The study area is within the Madhupur Tract agro-ecological zone (AEZ 28). The soil used for pot experiments belongs to the Salna series and has been classified as “swallow red brown terrace soil” in the Bangladesh soil classification system, which falls under the order Inceptisol (Brammer, 1978). This soil is characterized by clay within 50 cm of the surface and is slightly acidic in nature. The pH value, cation exchange capacity (CEC) and electrical conductivity (EC) of bulk soil samples collected from the study site were 6.38, 6.78 meq 100 g-1 soil and 0.6 dS m-1, respectively. This soil contained 1.08% organic carbon (OC), 1.87% organic matter (OM), 0.10% nitrogen (N), 9 ppm phosphorus (P) and 0.20 meq 100 g-1 soil exchangeable potassium (K).

Plant Material, Bacterial Isolation, and Pathogenic Organism

Cucumber (Cucumis sativus L.) variety Baromashi (Lal Teer Seed Company, Dhaka, Bangladesh) root samples were collected from the study site along with rhizosphere soil. For isolation of bacteria, 2–5 g of fresh roots were washed under running tap water and surface sterilized in 5% NaOCl for 1 min. After washing three times with sterilized distilled water (SDW), the root samples were ground with a sterilized mortar and pestle. Serial dilutions were prepared from the ground roots, and 100 μl aliquots from each dilution of 1 × 10-6, 1 × 10-7, and 1 × 10-8 CFU mL-1 were spread on potato dextrose agar (PDA) plates and incubated for 2 days at 28 ± 2°C. Morphologically distinct bacterial colonies were selected for further purifications. The purified isolates were preserved temporarily in 20% glycerol solution at -20°C. The pathogen P. capsici was provided by Prof. W. Yuanchao, Nanjing Agricultural University, China.

Morphological and Biochemical Characterization of Bacterial Isolates

Colony morphology, size, shape, color, and growth pattern were recorded after 24 h of growth on PDA plates at 28 ± 2°C as described by Somasegaran and Hoben (1994). Cell size was observed by light microscopy. The Gram reaction was performed as described by Vincent and Humphrey (1970). A series of biochemical tests were conducted to characterize the isolated bacteria using the criteria of Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology (Bergey et al., 1994). For the KOH solubility test, bacteria were aseptically removed from Petri plates with an inoculating wire loop, mixed with 3% KOH solution on a clean slide for 1 min and observed for formation of a thread-like mass. The motility of each isolate was tested in sulfide indole motility (SIM) medium. Using a needle, strains were introduced into test tubes containing SIM, and were incubated at room temperature until the growth was evident (Kirsop and Doyle, 1991). Turbidity away from the line of inoculation was a positive indicator of motility. Catalase and oxidase tests were performed as described in Hayward (1960) and Rajat et al. (2012), respectively. To determine whether the rhizobacterial isolates are better suited to aerobic or anaerobic environments, the citrate test was conducted according to Simmons (1926) using Simmons citrate agar medium. All experiments were done following complete randomized design (CRD) with three replications for each isolate and repeated once.

Molecular Characterization of Bacterial Isolates

Culture DNA was obtained using the lysozyme-SDS-phenol/chloroform method (Maniatis et al., 1982). DNA was extracted with phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (25:24:1) and precipitated with isopropanol. The extracted DNA was treated with DNase-free RNase (Sigma Chemical Co., St. Louis, MO, USA) at a final concentration of 0.2 mg/ml at 37°C for 15 min, followed by a second phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and isopropanol precipitation. Finally, the DNA pellet was re-suspended in TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8.0), stored at -20°C, and used as template DNA in PCR to amplify the 16S rRNA for phylogenetic analysis.

16S rRNA gene amplification was performed by using the bacterial-specific primers, 27F (5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′) and 1492R (5′-GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT-3′) (Reysenbach et al., 1992). PCR amplifications were performed with 1 × Ex Taq buffer (Takara Bio Inc, Japan), 0.8 mM dNTP, 0.02 units μl-1 Ex Taq polymerase, 0.4 mg ml-1 BSA, and 1.0 μM of each primer. Three independent PCR amplifications were performed at an annealing temperature of 55°C (40 s), an initial denaturation temperature of 94°C (5 min), 30 amplification cycles with denaturation at 94°C (60 s), annealing (30 s), and extension at 72°C (60 s), followed by a final extension at 72°C (10 min). The PCR product was purified using Wizard® PCR Preps DNA Purification System (Promega, Madison, WI, USA). Purified double-stranded PCR fragments were directly sequenced with Big Dye Terminator Cycle sequencing kits (Applied Biosystems, Forster City, CA, USA) using the manufacturer’s instructions. Sequences for each region were edited using Chromas Lite 2.01. The 16S rRNA sequence of the isolate has been deposited in the GenBank database. The BLAST search program2 was used to search for nucleotide sequence homology for the 16S region for bacteria. Highly homologous sequences were aligned, and neighbor-joining trees were generated using ClustalX version 2.0.11 and MEGA version 6.06. Bootstrap replication (1000 replications) was used as a statistical support for the nodes in the phylogenetic trees.

Bioassays for Plant Growth Promoting Traits

Biological Nitrogen Fixation

Nitrogenase activity of isolates was determined via the acetylene reduction assay/ethylene production assay as described in Hardy et al. (1968). Pure bacterial colonies were inoculated to an airtight 30 ml vial containing 10 ml nitrogen-free basal semi-solid medium, and were grown for 48 h at 28 ± 2°C. Following pellicle formation, the bottles were injected with 10% (v/v) acetylene gas and incubated at 28 ± 2°C for 24 h. Ethylene production was measured using a G-300 Gas Chromatograph (Model HP 6890, USA) fitted with a Flame Ionization Detector and a Porapak-N column. Hydrogen and oxygen were used as a carrier gas, with a flow rate of 4 kg/cm2, and the column temperature was maintained at 165°C. The ethylene concentration calibration curve was plotted for each trial, and the viable cell numbers (cfu) of the isolate were determined. The rate of N2 fixation was expressed as the quantity of ethylene accumulated (μmol C2H4 mg-1 protein h-1) based on the standard curve and peak-area percentage.

Indole-3-Acetic Acid Production

For detection and quantification of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) production by bacterial isolates, isolated colonies were inoculated into Jensen’s broth (Sucrose 20 g, K2HPO4 1 g L-1, MgSO4 7H2O 0.5 g L-1, NaCl 0.5 g L-1, FeSO4 0.1 g L-1, NaMoO4 0.005 g L-1, CaCO3 2 g L-1) (Bric et al., 1991) containing 2 mg mL-1 L-tryptophan. The culture was incubated at 28 ± 2°C with continuous shaking at 125 rpm for 48 h (Rahman et al., 2010). Approximately 2 mL of culture solution was centrifuged at 15000 rpm for 1 min, and a 1 mL aliquot of the supernatant was mixed with 2 mL of Salkowski’s reagent and incubated 20 min in darkness at room temperature (150 ml concentrated H2SO4, 250 ml distilled water, 7.5 ml 0.5 M FeCl3.6H2O) as described by Gordon and Weber (1951). IAA production was observed as the development of a pink-red color, and the absorbance was measured at 530 nm using a spectrophotometer. The concentration of IAA was determined using a standard curve prepared from pure IAA solutions (0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 30, 35, 40, 45, 50, 55, 60, and 65 μg ml-1).

Preparation of Bacterial Inocula for Cucumber Seed Treatment

Bacterial strains were cultured in 250 ml conical flasks containing 200 ml yeast peptone broth on an orbital shaker at 120 rpm for 72 h at 28 ± 2°C. Bacterial cells were collected via centrifugation at 15000 rpm for 1 min at 4°C, and each pellet was washed twice with SDW. The bacterial pellets were suspended in 0.6 ml SDW, vortexed and used for seed treatment. Approximately 30–31 cucumber seeds were surface sterilized in 5% NaOCl for 1 min and washed three times in SDW. Dry seeds were immersed in each bacterial suspension, and the preparation was stirred frequently for 5 min. The treated seeds were spread on a petri dish and air dried overnight at room temperature. The number of bacterial cells per seed, determined via serial dilutions, was approximately 108 CFU/seed.

Effect of Bacterial Seed Treatment on Germination and Vigour Index in Cucumber

In order to determine the effect of the isolates on germination and seedling vigour, 100 seeds inoculated with each isolate were incubated in ten 9-cm petri dishes on two layers of moistened filter paper. As a control treatment, seeds treated with water instead of bacterial suspensions were also established. In order to maintain sufficient moisture for germination, 5 ml distilled water was added to the petri dishes every other day, and seeds were incubated at 28 ± 2°C in a light incubator. Germination was considered to have occurred when the radicles were half of the seed length. The germination percentage was recorded every 24 h for 7 days. Root and shoot length were measured after the seventh day. The experiment was planned as a completely randomized design with 10 replications for each isolate.

Effect of Bacterial Seed Treatment on Growth and Nitrogen Content in Cucumber Plants

In order to test the ability of isolates to promote growth in cucumber plants, surface-sterilized cucumber seeds were inoculated with each isolate as described above. The soil from the study site described above was used as potting medium. After autoclaving twice at 24 h intervals at 121°C and 15 psi for 20 min, 180 g of the sterilized soil was placed in each sterilized plastic pot (9.5 cm × 7.0 cm size). One pre-germinated cucumber seed was sown in each pot, and plants were grown 3 weeks in a net house with watering on alternate days. After harvest, the fresh weight, dry weight, and root and shoot lengths of the plants were measured. The shoots and roots were separated and dried in an oven at 68 ± 2°C for 48 h, then ground for determination of tissue-N concentrations (Kjeldahl, 1883).

Root Colonization

Root colonization by bacterial isolates was determined according to the protocol of Hossain et al. (2008). Roots were harvested from plants at 7, 14, and 21 days of growth. Root systems were thoroughly washed with running tap water to remove adhering soil particles, then were rinsed three times with SDW and blotted to dryness. Roots were divided into top, middle, and bottom regions, and were weighed and homogenized in SDW. Serial dilutions were prepared on PDA plates, and the number of colony-forming units (cfu) per gram root was determined after 24 h of incubation at 28 ± 2°C.

Pathogenicity of P. capsici in Cucumber

For preparation of zoospore inoculum, P. capsici was cultured on PDA plates at 18 ± 2°C for 7 days. Five-mm blocks were then cut from the culture plates and placed in petri dishes containing SDW. The petridishes were incubated in darkness at room temperature for 72 h, followed by a 1-h cold treatment at 4°C. Zoospore production was confirmed via light microscopy. In order to test the pathogenicity of P. capsici zoospores, cucumber seedlings were planted in pots containing 0, 500, 1000, or 1500 μl zoospores/pot. As 100% mortality was found in case 1000 μl zoospores/pot, two concentrations (500 and 1000 μl) of zoospores suspension per pot were fixed.

In Vitro Screening for Antagonism

To test antagonism of P. capsici by each isolate, the pathogen and bacteria were inoculated 3 cm apart on the same agar plate. Fungal growth on each plate was observed, and the zone of inhibition, if present, was determined as described in Riungu et al. (2008):

Where,

X = Mycelial growth of pathogen in absence of antagonists

Y = Mycelial growth of pathogen in presence of antagonists

Morphologies of hyphae in the vicinity of bacterial colonies were observed under a light microscope (Meiji Techno: ML2600), and images were recorded with a digital camera (Model: Canon Digital IXUS 900 Ti). Each experiment was carried out following CRD with three replications for each isolate and repeated once.

Testing the Effect of Rhizobacterial Seed Treatment on Phytophthora Crown Rot of Cucumber

Cucumber seeds inoculated with each isolate were sown and grown for 7 days in sterilized plastic pots as described above. Seven-day-old seedlings were inoculated with 500 or 1000 μl zoospore suspension/pot as described in Deora et al. (2005). Inoculated plants were kept inside humid chambers for 48 h. Each experiment included 12 plants per treatment with three replications. Surviving plants were counted 7 days after inoculation. Percent disease incidences (PDI) were calculated using the following formula:

Percent protection by PGPR was calculated using following formula:

Where,

A = PDI in non-inoculated control plants

B = PDI in PGPR-treated plants.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS (Version 17) and Microsoft Office Excel 2007. A completely randomized design was used for all experiments, with 3–12 replications for each treatment. The data presented are from representative experiments that were repeated at least twice with similar results. Treatments were compared via ANOVA using the least significant differences test (LSD) at 5% (P ≤ 0.05) probability level.

Results

Strain Isolation and Biochemical and Molecular Characterization

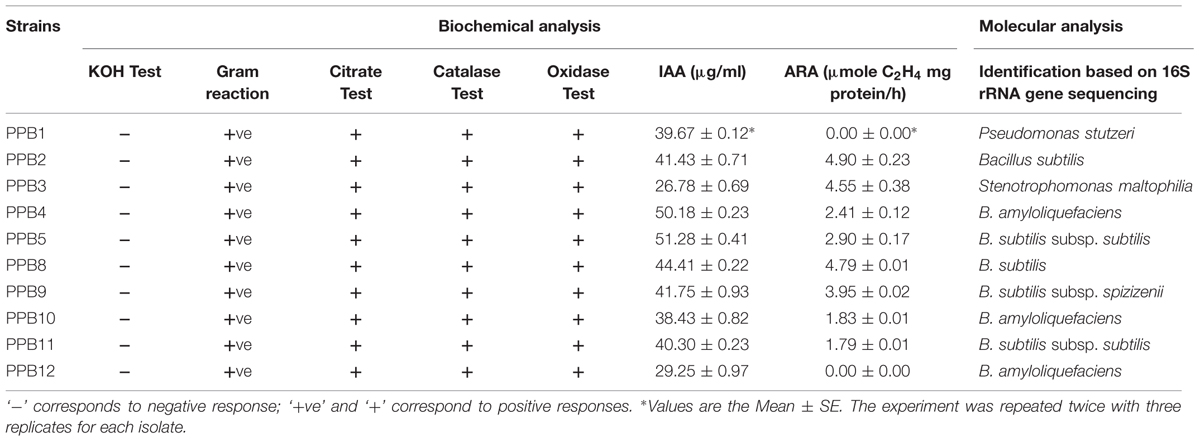

We obtained a total of 66 rhizobacterial strains from the interior of cucumber roots. Ten isolates – PPB1, PPB2, PPB3, PPB4, PPB5, PPB8, PPB9, PPB10, PPB11, and PPB12 – were selected based on their ability to produce IAA, fix N2, and show in vitro antagonism against various pathogens in a preliminary screening. All isolates were rods producing fast-growing, round to irregular colonies with raised elevations and smooth surfaces. Reddish pigmentation was produced by PPB5, while no pigmentation was produced by other isolates (Supplementary Table S1). All 10 isolates were motile and reacted positively to the Gram staining, citrate, catalase and oxidase tests, but reacted negatively to the KOH solubility test (Table 1).

Phylogenetic trees constructed from 16S rRNA sequences showed that the selected isolates were mainly members of genus Bacillus, Pseudomonas, and Stenotrophomonas (Supplementary Figure S1). The sequences of the isolates PPB2, PPB5, PPB8, PPB9, and PPB11 showed 99% similarity with Bacillus subtilis and were submitted to GenBank under accession numbers KJ690255, KM008605, KM008606, KM092525 and KM092527, respectively (Table 1). Isolate PPB1 had 99% homology with Pseudomonas stutzeri and was submitted to GenBank under accession number KJ959616. Isolate PPB3 was identified as Stenotrophomonas maltophilia with GenBank accession number KJ959617. Isolates PPB4, PPB10, and PPB12 showed 99% sequence homology with B. amyloliquefaciens and were submitted to GenBank under accession number KM008604, KM092526 and KM092528, respectively (Table 1).

Characterization for Plant Growth Promoting Traits

The plant growth promoting characteristics viz., IAA production and ARA were examined with the ten selected PGPR isolates. The results of the assays are presented in Table 2. In the presence of tryptophan, the isolated bacteria produced IAA in concentrations between 26.78 μg mL-1 and 51.28 μg mL-1. The highest and lowest amounts of IAA were produced by strain PPB5 and PPB3, respectively (Table 2). Nitrogenese activity, as determined by ARA, was not detected in PPB1 and PPB12 under the conditions tested. However, the ARA values ranged from 1.79 to 4.9 μmole C2H4/mg protein/h for remaining isolates. PPB2 showed the highest activity, while the lowest was recorded for PPB11 (Table 1). The other isolates also reduced acetylene in significant amounts. Collectively, these results suggest that the isolates possess a number of traits associated with plant growth promotion.

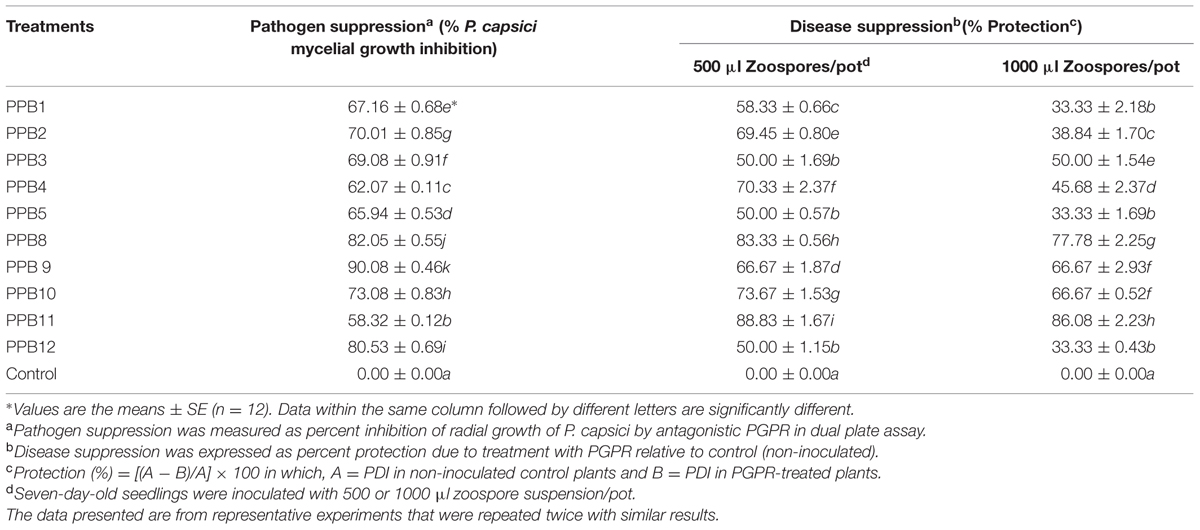

TABLE 2. Comparative performance of PGPR in mycelia growth inhibition of P. capsici and Phytophthora crown rot disease suppression in cucumber plants.

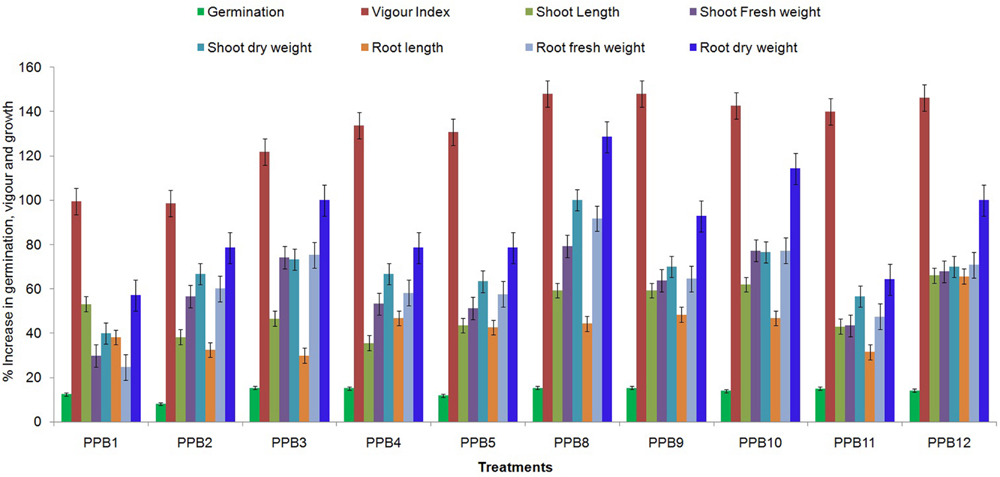

Germination and Vigour Index Improvement in Cucumber

The effect of rhizobacterial treatment upon seed germination and vigour index of cucumber varied with different isolates. All treatments had a significant effect on the germination rate and vigour index compared to the control. The PGPR treatments increased the germination rate of cucumber seeds by 8.07–15.32% compared with the control, while the vigour index was increased by 98.62–148.05% (Figure 1). In both germination rate and vigour index, the maximum increase was obtained with the PPB9 treatment. These results suggest that rhizobacterial treatment could improve the germination and vigour of cucumber seeds.

FIGURE 1. Effect of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) treatments on seed germination, vigour and growth characteristics of cucumber seedlings grown in pots under axenic conditions. Error bars are SE from three replicates per same treatment. Data are presented as % increase in germination, vigour index, shoot length, root length, shoot fresh weight, root fresh weight, shoot dry weight, and root dry weight of PGPR-treated cucumber seedlings relative to non-treated control seedlings. The experiment was repeated twice.

Plant Growth Promotion in Cucumber

All isolates significantly increased the growth of cucumber compared to non-inoculated controls. Treatment with isolate PPB12 produced the maximum shoot and root lengths of 18.23 and 20.47 cm, corresponding to increases of 66.02 and 65.63% above control treatments (Figure 1). However, the maximum shoot and root weight enhancement was observed in PPB8-treated plants. Treatment with isolate PPB8 produced shoot fresh and dry weights of 5.29 and 0.60 g plant-1, which were 79.32 and 100.00% higher than those of control plants. Similarly, treatment with isolate PPB8 produced root fresh and dry weights of 3.03 and 0.32 g plant-1, corresponding to increase of 91.77 and 128.57% above control treatments.

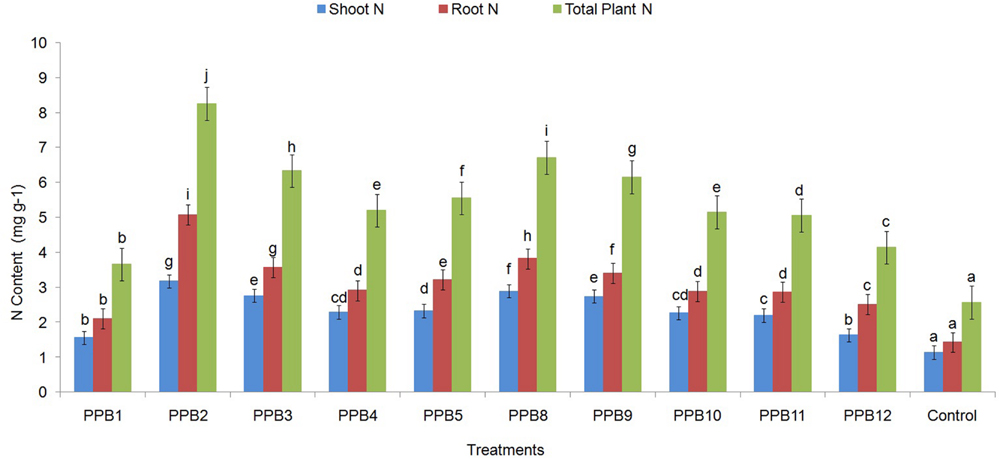

N Concentration in Cucumber Plants

The N content in plant roots and shoots significantly increased due to inoculation treatments with rhizobacterial isolates (Figure 2). The shoot and root N content showed similar trends in response to different treatments; hence, the N content is reported as the total combined shoot and root N. The total N content in PGPR-treated plants ranged from 3.66 mg g-1 to 8.25 mg g-1 N compared with 2.57 mg g-1 N for non-inoculated control plants, a 42–221% increase in PGPR-treated plants over control plants (Figure 2). The highest N content was recorded in plants grown under PPB2 followed by PPB8, PPB3, PPB9 and other treatments.

FIGURE 2. Effect of inoculation with PGPR strains on shoot and root N contents of cucumber plants. Error bars are SE from three replicates that received the same treatment. Data represents total shoot and root N concentration (mg g-1), each from 3 sets of 8–10 shoots and roots sampled following harvesting the cucumber plants. Within each frame different letters indicate statistically significant difference between treatments (LSD test, P ≤ 0.05). The experiment was repeated twice.

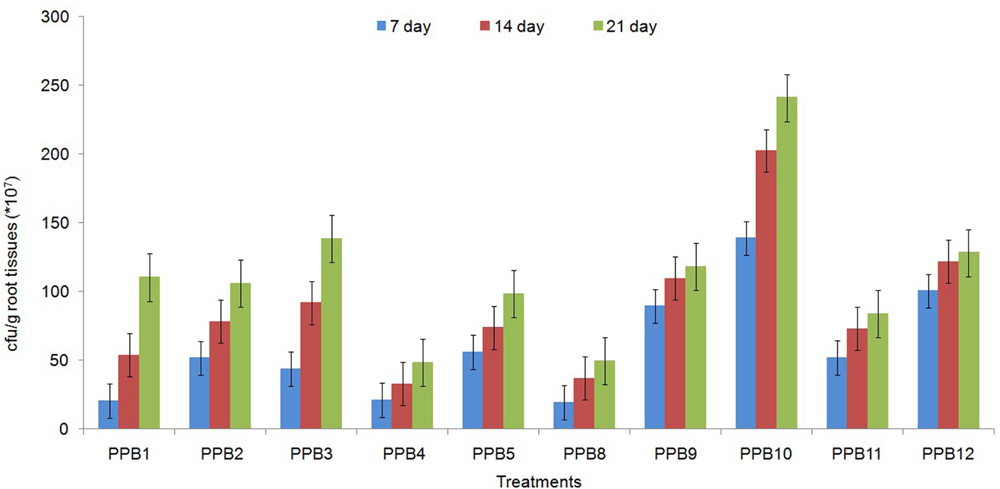

Root Colonization

The ability to colonize the root system is essential for rhizobacteria to be effective plant growth promoters. The root colonization assays showed that all the tested isolates successfully colonized the roots of cucumber plants as tested after only 7 days of seedling growth. The inoculated populations were even higher on 21-day-old roots. Nevertheless, the root population densities varied widely among the isolates (Figure 3). The largest root populations were observed for strain PPB2, followed by PPB5 and PPB9 (Figure 3). These results demonstrate specific interactions between cucumber plants and the rhizobacterial isolates.

FIGURE 3. Population density (cfu) of different PGPR strains from roots of 7-, 14-, and 21-day-old cucumber seedlings. Error bars are SE from three replicates per treatment. Data are presented as numbers of c.f.u. g-1 fresh weight, each from three sets of 5–8 whole roots. The data presented are from representative experiments that were repeated twice with similar results.

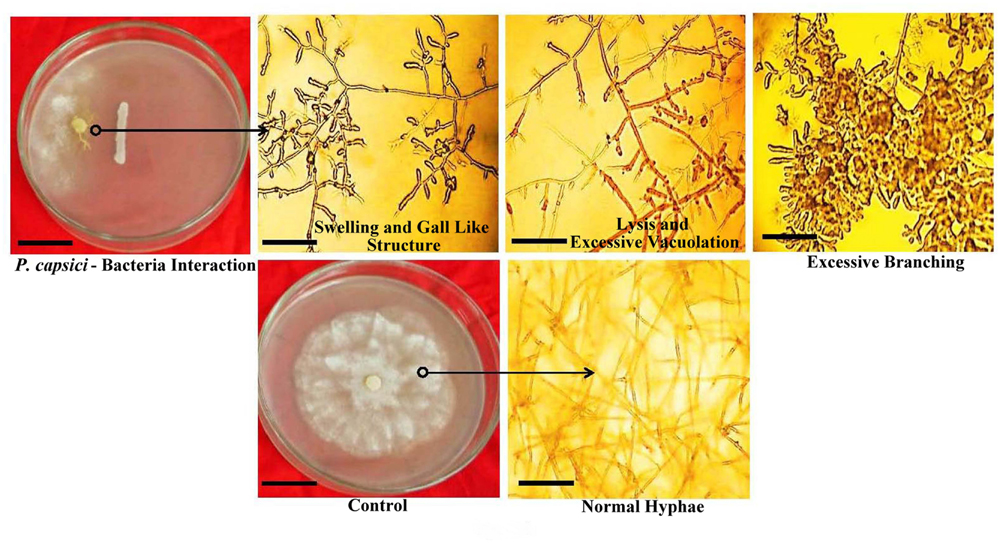

In vitro Antagonism of Phytophthora capsici

All rhizobacterial isolates exhibited significant antagonistic activity against P. capcisi on PDA. The largest inhibition zone was observed with PPB9 (90.08%) followed by PPB8 (82.05%) (Table 2). Distinct morphological alterations in P. capcisi hyphae were also detected during dual cultures with the rhizobacterial isolates. Hyphal features observed in the vicinity of bacterial colonies included irregular and excessive branching, abnormal swelling of hyphal diameters, unusually long and pointed hyphal tips, and vacuolization leading to hyphal lysis (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4. In vitro interactions of PGPR strains with P. capsici on PDA plates, including morphological alterations in P. capsici hyphae.

Suppression of Phytophthora Crown Rot in Cucumber

All the selected PGPR strains showed consistent suppression of Phytophthora crown rot in the greenhouse experiments. Compared with the control, the average disease protection at 500 μl zoospore suspension ranged from 50 to 88.83% after treatment with rhizobacterial isolates, while protection at 1000 μl zoospore suspension ranged from 33.33 to 86.08% (Table 2). At both inoculum rates, isolate PPB11 showed the highest disease reduction, and the lowest disease reduction was obtained with PPB5.

Discussions

PGPR colonizing the surface or inner part of roots play important beneficial roles that directly or indirectly influence plant growth and development (Glick et al., 1999; Gerhardt et al., 2009). In this study, 10 PGPR classified as Pseudomonas stutzeri (PPB1), B. subtilis (PPB2, 5, 8, 9, and 11), S. maltophilia (PPB3), and B. amyloliquefaciens (PPB4, 10, and 12) were isolated from the rhizosphere of cucumber plants. All the isolated PGPR were gram positive and motile rods, and tested positive for the ability to utilize citrate as a carbon source. Flagellar motility and citrate utilization are both thought to play a significant role in competitive root colonization and maintenance of bacteria in roots (Turnbull et al., 2001; Weisskopf et al., 2011). These strains also tested positive for oxidase and catalase activity. Standard microbiology references suggest that S. maltophilia is an oxidase-negative bacterium (Ryan et al., 2009). Recent data, however, suggest that some S. maltophilia are oxidase-positive (Carmody et al., 2011), and this was also the case for isolate PPB3 in this study. Our catalase test results corroborate prior studies showing that B. subtilis, Pseudomonas stutzeri, and B. amyloliquefaciens are catalase-positive (Merchant and Packer, 1999; Kamboh et al., 2009). Bacillus and Pseudomonas are the most frequently reported genera of PGPR (Laguerre et al., 1994; Hallmann and Berg, 2006; Zahid et al., 2015). Similarly, most isolates in this study belong to genus Bacillus.

Treatment of cucumber seeds with the selected isolates significantly improved seedling emergence and growth. Several different mechanisms have been suggested for similar observations using other PGPR strains: PGPR might indirectly enhance seed germination and vigour index by reducing the incidence of seed mycoflora, which can be detrimental to plant growth (Begum et al., 2003). Duarah et al. (2011) found that amylase activity during germination was increased in rice and legume after inoculation with PGPR. The amylase hydrolyzes the starch into metabolizable sugars, which provide the energy for growth of roots and shoots in germinating seedlings (Beck and Ziegler, 1989; Akazawa and Nishimura, 2011). One of the most commonly reported mechanisms is the production of phytohormones such as IAA (Patten and Glick, 2002). All the selected isolates in this study produced IAA. Similar studies have shown that IAA production is very common among PGPR (Yasmin et al., 2004; Ng et al., 2012; Zahid et al., 2015). In fact, many isolates in this study produced higher IAA than previously reported strains (Yasmin et al., 2004; Banerjee et al., 2010; Ng et al., 2012). This is an important mechanism of plant growth promotion because IAA promotes root development and uptake of nutrients (Carrillo et al., 2002). It has long been proposed that phytohormones act to coordinate demand and acquisition of nitrogen (Kiba et al., 2011). Therefore, enhanced N-content found in inoculated plants could be due to increased N-uptake by the roots caused by hormonal effects on root morphology and activity. Nitrogen fixation may also play a role in plant growth promotion. All the selected isolates in this study except PPB1 and PPB12 showed acetylene reduction activity, which is a widely accepted surrogate for nitrogenase activity and N2-fixing potential (Andrade et al., 1997). However, defensible proof of N2-fixation needs the application of 15N as tracer of soil N or as 15N2-gas and the demonstration of significantly changed N-isotope-labeling in the plant biomass. Transfer of N between diazotrophic N-fixing rhizobacteria and the roots of several crops has been demonstrated (Islam et al., 2009; Abbasi et al., 2011; Tajini et al., 2012; Verma et al., 2013). It is interesting to note that in this study all isolates, including the two that demonstrated no acetylene reduction activity, enhanced the N content of cucumber. This suggests that while N2 fixation may be an important mechanism of plant growth promotion, there may also be alternate mechanisms, like hormonal interactions and nutrient uptake or pathogen suppression, which might be more pronounced than the contribution of nitrogen fixation.

Results from our study indicate that PGPR strains applied as a seed treatment significantly reduced disease severity of Phytophthora crown rot on cucumber plants. The fungal antagonists Pseudomonas stutzeri, B. subtilis, B. amyloliquifaciens, and S. maltophilia were have been shown to be effective biocontrol agents in prior studies (Dunne et al., 2000; Zhang and Yuen, 2000; Dal Bello et al., 2002; Berg et al., 2005; Islam and Hossain, 2013; Erlacher et al., 2014). Competitive root tip colonization by PGPR strains might play an important role in the efficient control of soil-borne diseases. The crucial colonization level that must be reached has been estimated at 105–106 cfu g-1 of root in the case of Pseudomonas sp., which protect plants from Gaeumannomyces tritici or Pythium sp. (Haas and Défago, 2005). Most of our selected strains were efficient colonizers of roots, since CFU counts for tested strains were more than 107 cfu g-1 root. However, the former study examined the root colonization by introduced bacteria under natural field soil conditions, while our study did under axenic conditions. In view of that, comparison between root colonization data obtained under these two conditions may not be accurate. Biological control of P. capsici can also result from antibiosis by the bacteria (Nakayama et al., 1999; Kawulka et al., 2004; Chung et al., 2008; Lim and Kim, 2010; Mousivand et al., 2012; Islam and Hossain, 2013). All the selected isolates exhibited moderate to high antagonistic activity against P. capsici in vitro, and caused clear morphological distortions such as abnormal branching, curling, swelling and lysis of the hyphae at the interaction zone in dual cultures. Excessive branching and curling accompanied by marked ultrastructural alterations including invagination of the hyphal membrane, disintegration or necrosis of hyphal cell walls, accumulation of excessive lipid bodies, enlarged and electron-dense vacuoles, and degradation of cytoplasm were potentially due to bacterial production of antibiotics and lytic enzymes (Deora et al., 2005; Islam and von Tiedemann, 2011). These antibiotics and lytic enzymes cause membrane damage and are particularly inhibitory to zoospores of Oomycete (de Souza et al., 2003; Beneduzi et al., 2012). Induced systemic resistance is most likely another mechanism by which bacteria suppress P. capsici (Zhang et al., 2010).

In the present study, we have isolated 10 new strains of PGPR from indigenous cucumber plants. These strains possessed several plant growth promoting traits as well as antifungal activity, and were found to be efficient in controlling Phytophthora crown rot of cucumber seedlings. In vitro and in vivo evidence suggest that the selected isolates benefit cucumber plants via multiple modes of action including antibiosis against phytopathogens, competitive colonization, and plant growth promotion. This reveals the potential of these strains for biofertilizer applications and commercial use as biocontrol agents in the field. However, from the estimation of a PGPR-potential to a biofertilizer application, it requires a long way of greenhouse experiments with pot filled with different type of soils and finally, field experiments to find out the optimum formulations for the inoculums. Thus, the inoculants can perform close to its optimum potential. Future studies concerning commercialization and field applications of integrated stable bio-formulations as effective biocontrol strategies are in progress.

Author Contribution

SI was involved in the planning and execution of the research work; collection, analysis and interpretation of the data; manuscript writing etc. following the suggestions and directions of the Major Professor. AMA served as the Member of the Dissertation Committee of SI and was involved in the planning of the work and editing of the manuscript. AP was actively involved in the original research work, data collection, analysis as well as manuscript preparation. TI supplied the Phytophthora capsici inocula and oversaw the sequence work of the bacterial isolates and related description in the manuscript. MMH served as the Major Professor of SI and was involved in the research design and planning; analysis and interpretation of data; drafting as well as critical revision of the work for intellectual content.

All authors approve the final version of the manuscript for publication and agrees to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to acknowledge the financial assistance from University Grant Commissions through Research Management Committee of Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman Agricultural University, Bangladesh. The authors also wish to thank Prof. M. T. Islam for his help obtain 16S rRNA sequences of the tested bacterial isolates.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.01360

FIGURE S1 | Phylogenetic tree of 16S rRNA gene sequences showing the relationships among the isolates isolated from cucumber rhizosphere. The data of type strains of related species were from GenBank database.

Footnotes

References

Abbasi, M. K., Sharif, S., Kazmi, M., Sultan, T., and Aslam, M. (2011). Isolation of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from wheat rhizosphere and their effect on improving growth, yield and nutrient uptake of plants. Plant Biosyst. 145, 159–168. doi: 10.1080/11263504.2010.542318

Ahmed, A., Ezziyyani, M., Egea-Gilabert, C., and Candela, M. E. (2003). Selecting bacterial strains for use in the biocontrol of diseases caused by Phytophthora capsici and Alternaria alternate in sweet pepper plants. Biol. Plant. 47, 569–574.

Akazawa, T., and Nishimura, H. (2011). Topographic aspects of biosynthesis, extracellular secretion, and intracellular storage of proteins in plant cells. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. 36, 441–472. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.36.060185.002301

Andrade, G., Esteban, E., Velasco, L., Lorite, M. J., and Bedmar, E. J. (1997). Isolation and identification of N2-fixing microorganisms from the rhizosphere of Capparisspinosa (L.). Plant Soil 197, 19–23. doi: 10.1023/A:100421190964

Aravind, R., Kumar, A., Eapen, S. J., and Ramana, K. V. (2009). Endophytic bacterial flora in root and stem tissues of black pepper (Piper nigrum L.) genotype: isolation, identification and evaluation against Phytophthora capsici. Lett. Appl. Microbiol 48, 58–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1472-765X.2008.02486.x

Bais, H. P., Fall, R., and Vivanco, J. M. (2004). Biocontrol of Bacillus subtilis against infection of Arabidopsis roots by Pseudomonas syringae is facilitated by biofilm formation and surfactin production. Plant Physiol. 134, 307–319. doi: 10.1104/pp.103.028712

Banerjee, S., Palit, R., Sengupta, C., and Standing, D. (2010). Stress induced phosphate solubilization by ‘Arthrobacter’ sp. and ‘Bacillus’ sp. isolated from tomato rhizosphere. Aust. J. Crop. Sci. 4, 378–383.

Bargabus, R. L., Zidack, N. K., Sherwood, J. E., and Jacobsen, B. J. (2002). Characterization of systemic resistance in sugar beet elicited by a non-pathogenic, phylosphere-colonizing Bacillus mycoides, biological control agents. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 61, 289–298. doi: 10.1006/pmpp.2003.0443

Beck, E., and Ziegler, P. (1989). Biosynthesis and degradation of starch in higher plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Physiol. Plant Mol. Biol. 40, 95–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pp.40.060189.000523

Begum, M., Rai, V. R., and Lokesh, S. (2003). Effect of plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on seed borne fungal pathogens in okra. Indian Phytopathol. 56, 156–158.

Beneduzi, A., Ambrosini, A., and Passaglia, L. M. (2012). Plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR): their potential as antagonists and biocontrol agents. Genet. Mol. Biol. 35, 1044–1051. doi: 10.1590/S1415-47572012000600020

Berg, G., Krechel, A., Ditz, M., Sikora, R. A., Ulrich, A., and Hallmann, J. (2005). Endophytic and ectophytic potato-associated bacterial communities differ in structure and antagonistic function against plant pathogenic fungi. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 51, 215–229. doi: 10.1016/j.femsec.2004.08.006

Bergey, D. H., Holt, J. G., and Noel, R. K. (1994). Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology, Vol. 1, 9th Edn (Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins), 1935–2045.

Brammer, H. (1978). Rice Soils of Bangladesh. In: Soils and Rice. Los Banos: International Rice Research Institute Publication, 35–55.

Bric, J. M., Bostock, R. M., and Silverstone, S. E. (1991). Rapid in situ assay for indole acetic acid production by bacteria immobilized on a nitrocellulose membrane. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 57, 535–538.

Bulgarelli, D., Schlaeppi, K., Spaepen, S., Ver Loren van Themaat, E., and Schulze-Lefert, P. (2013). Structure and functions of the bacterial microbiota of plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 64, 807–838. doi: 10.1146/annurev-arplant-050312-120106

Carmody, L. A., Spilker, T., and Li Puma, J. J. (2011). Reassessment of Stenotrophomonas maltophilia phenotype. J. Clin. Microbiol. 49, 1101–1103. doi: 10.1128/JCM.02204-10

Carrillo, A. E., Li, C. Y., and Bashan, Y. (2002). Increased acidification in the rhizosphere of cactus seedlings induced by Azospirillum brasilense. Naturwissenschaften 89, 428–432. doi: 10.1007/s00114-002-0347-6

Cattelan, A. J., Hartel, P. G., and Fuhrmann, J. J. (1999). Screening for plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria to promote early soybean growth. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 63, 1670–1680. doi: 10.2136/sssaj1999.6361670x

Cazorla, F. M., Romero, D., Pérez-García, A., Lugtenberg, B. J., Vicente, A., and Bloemberg, G. (2007). Isolation and characterization of antagonistic Bacillus subtilis strains from the avocado rhizoplane displaying biocontrol activity. J. Appl. Microbiol. 103, 1950–1959. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2672.2007.03433.x

Chen, X. H., Koumoutsi, A., Scholz, R., Schneider, K., Vater, J., Süssmuth, R., et al. (2009). Genome analysis of Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42 reveals its potential for biocontrol of plant pathogens. J. Biotechnol. 140, 27–37. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2008.10.011

Chung, S., Kong, H., Buyer, J. S., Lakshman, D. K., Lydon, J., Kim, S. D., et al. (2008). Isolation and partial characterization of Bacillus subtilis ME488 for suppression of soilborne pathogens of cucumber and pepper. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 80, 115–123. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1520-4

Dal Bello, G. M., Mónaco, C. I., and Simón, M. R. (2002). Biological control of seedling blight of wheat caused by Fusarium graminearum with beneficial rhizosphere microorganisms. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 18, 627–636. doi: 10.1023/A:1016898020810

Deora, A., Hashidoko, Y., Islam, M. T., and Tahara, S. (2005). Antagonistic rhizoplane bacteria induce diverse morphological alterations in Peronosporomycete hyphae during in vitro interaction. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 112, 311–322. doi: 10.1007/s10658-005-4753-4

de Souza, J. T., Arnould, C., Deulvot, C., Lemanceau, P., Gianinazzi-Pearson, V., and Raaijmakers, J. M. (2003). Effect of 2,4-diacetylphloroglucinol on Pythium: cellular responses and variation in sensitivity among propagules and species. Phytopathology 93, 966–975. doi: 10.1094/PHYTO.2003.93.8.966

Detry, J., Rosenbaum, T., Lütz, S., Hahn, D., Jaeger, K. E., Müller, M., et al. (2006). Biocatalytic production of enantiopure cyclohexane-trans-1, 2-diol using extracellular lipases from Bacillus subtilis. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 72, 1107–1116. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0391-9

Duarah, I., Deka, M., Saikia, N., and Deka, B. H. P. (2011). Phosphate solubilizers enhance NPK fertilizer use efficiency in rice and legume cultivation. Biotech 1, 227–238.

Dunne, C., Loccoz, Y. M., de Bruijn, F. J., and O’Gara, F. (2000). Overproduction of an inducible extracellular serine protease improves biological control of Pythium ultimum by Stenotrophomonas maltophilia strain W81. Microbiology 146, 2069–2078. doi: 10.1099/00221287-146-8-2069

El-Sayed, S. W., Akhkha, A., El-Naggar, M. Y., and Elbadry, M. (2014). In vitro antagonistic activity, plant growth promoting traits and phylogenetic affiliation of rhizobacteria associated with wild plants grown in arid soil. Front. Microbiol. 5:651. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00651

Erlacher, A., Cardinale, M., Grosch, R., Grube, M., and Berg, G. (2014). The impact of the pathogen Rhizoctonia solani and its beneficial counterpart Bacillus amyloliquefaciens on the indigenous lettuce microbiome. Front. Microbiol. 5:175. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2014.00175

Gerhardson, B. (2002)). Biological substitutes for pesticides. Trends Biotechnol. 20, 338–343. doi: 10.1016/S0167-7799(02)02021-8

Gerhardt, K. E., Huang, X.-D., Glick, B. R., and Greenberg, B. M. (2009). Phytoremediation and rhizoremediation of organic soil contaminants: potential and challenges. Plant Sci. 176, 20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.plantsci.2008.09.014

Glick, B. R., Patten, C. L., Holguin, G., and Penrose, D. M. (1999). Biochemical and Genetic Mechanisms Used by Plant Growth Promoting Bacteria. London: Imperial College Press.

Gordon, S. A., and Weber, R. P. (1951). Colorimetric estimation of indole acetic acid. Plant Physiol. 26, 192–195. doi: 10.1104/pp.26.1.192

Haas, D., and Défago, G. (2005). Biological control of soil-borne pathogens by fluorescent Pseudomonads. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 3, 307–319. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro1129

Hallmann, J., and Berg, G. (2006). “Spectrum and population dynamics of bacterial root endophytes,” in Microbial Root Endophytes, eds B. Schulz, C. Boyle, and T. Sieber (Heidelberg: Springer), 15–31.

Hardy, R. W. F., Holstern, R. D., Jacksoen, E. K., and Burns, R. C. (1968). The acetylene-ethylene assay for N2 fixation: laboratory and field evaluation. Plant Physiol. 43, 1185–1207. doi: 10.1104/pp.43.8.1185

Hausbeck, M. K., and Lamour, K. H. (2004). Phytophthora capsici on vegetable crops: research progress and management challenges. Plant Dis. 88, 1292–1303. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2004.88.12.1292

Hayward, A. C. (1960). A method for characterizing Pseudomonas solanacearum. Nature 186:405. doi: 10.1038/186405a0

Heckel, D. G. (2012). Insecticide resistance after silent spring. Science 337, 1612–1614. doi: 10.1126/science.1226994

Hossain, M. M., Sultana, F., Kubota, M., and Hyakumachi, M. (2008). Differential inducible defense mechanisms against bacterial speck pathogen in Arabidopsis thaliana by plant-growth-promoting-fungus Penicillium sp. GP16-2 and its cell free filtrate. Plant Soil 304, 227–239. doi: 10.1007/s11104-008-9542-3

Hussain, S., Siddique, T., Saleem, M., Arshad, M., and Khalid, A. (2009). “Impact of pesticides on soil microbial diversity, enzymes, and biochemical reactions,” in Advances in Agronomy, Vol. 102, eds D. L. Sparks and S. H. du Pont (Amsterdam: Elseveir), 159–200.

Idris, E. E. S., Iglesias, D. J., Talon, M., and Borriss, R. (2007). Tryptophan-dependent production of indole-3-acetic acid (IAA) affects level of plant growth promotion by Bacillus amyloliquefaciens FZB42. Mol. Plant Microbe Interact. 20, 619–626. doi: 10.1094/MPMI-20-6-0619

Islam, M. R., Madhaiyan, M., Deka Boruah, H. P., Yim, W., Lee, G., Saravanan, V. S., et al. (2009). Characterization of plant growth-promoting traits of free-living diazotrophic bacteria and their inoculation effects on growth and nitrogen uptake of crop plants. J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 19, 1213–1222. doi: 10.4014/jmb.0903.3028

Islam, M. T., and Hossain, M. M. (2013). “Biological control of peronosporomycete phytopathogen by bacterial antagonist,” in Bacteria in Agrobiology: Disease Management, ed. D. K. Maheshwari (Heidelberg: Springer), 167–218.

Islam, M. T., and von Tiedemann, A. (2011). 2, 4-Diacetylphloroglucinol suppresses zoosporogenesis and impairs motility of Peronosporomycete zoospores. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 27, 2071–2079. doi: 10.1007/s11274-011-0669-7

Kamboh, A. A., Rajput, N., Rajput, I. R., Khaskheli, M., and Khaskheli, G. B. (2009). Biochemical properties of bacterial contaminants isolated from livestock vaccines. Pak. J. Nutr. 8, 578–581. doi: 10.3923/pjn.2009.578.581

Kawulka, K. E., Sprules, T., Diaper, C. M., Whittal, R. M., McKay, R. T., Mercier, P., et al. (2004). Structure of Subtilosin A, a cyclic antimicrobial peptide from Bacillus subtilis with unusual sulfur to α-carbon cross-links: formation and reduction of α-Thio-α-Amino Acid derivatives. Biochemistry 43, 3385–3395. doi: 10.1021/bi0359527

Kiba, T., Kudo, T., Kojima, M., and Sakakibar, H. (2011). Hormonal control of nitrogen acquisition: roles of auxin, abscisic acid, and cytokinin. J. Exp. Bot. 62, 1399–1409. doi: 10.1093/jxb/erq410

Kim, Y. C., Jung, H., Kim, K. Y., and Park, S. K. (2008). An effective biocontrol bioformulation against Phytophthora blight of pepper using growth mixtures of combined chitinolytic bacteria under different field conditions. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 120, 373–382. doi: 10.1007/s10658-007-9227-4

Kirsop, B. E., and Doyle, A. (1991). Maintenance of Microorganisms and Cultured Cells: A Manual of Laboratory Methods, 2nd Edn. London: Academic Press.

Kjeldahl, J. (1883). A new method for the estimation of nitrogen in organic compounds.Z. Anal. Chem. 22:366. doi: 10.1007/BF01338151

Kloepper, J. W., Leong, J., Teintze, M., and Schroth, M. N. (1980). Enhanced plant growth by siderophores produced by plant growth promoting rhizobacteria. Nature 268, 885–886. doi: 10.1038/286885a0

Konsoula, Z., and Liakopoulou-Kyriakides, M. (2006). Thermostable α-amylase production by Bacillus subtilis entrapped in calcium alginate gel capsules. Enzyme Microb. Technol. 39, 690–696. doi: 10.1016/j.enzmictec.2005.12.002

Laguerre, G., Attard, M. R., Revoy, F., and Amarger, N. (1994). Rapid identification of Rhizobia by restriction fragment length polymorphism analysis of PCR amplified 16S rRNA genes. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 60, 56–63.

Lee, B. K., Kim, B. S., Chang, S. W., and Hwang, B. K. (2001). Aggressiveness to pumpkin cultivars of isolates of Phytophthora capsici from pumpkin and pepper. Plant Dis. 85, 497–500. doi: 10.1094/PDIS.2001.85.5.497

Lim, J. H., and Kim, S. D. (2010). Biocontrol of Phytophthora blight of red pepper caused by Phytophthora capsici using Bacillus subtilis AH18 and B. licheniformis K11 formulations. J. Korean Soc. Appl. Biol. Chem. 53, 766–773. doi: 10.3839/jksabc.2010.116

Liu, C. H., Chen, X., Liu, T. T., Lian, B., Gu, Y., Caer, V., et al. (2007). Study of the antifungal activity of Acinetobacter baumannii LCH001 in vitro and identification of its antifungal components. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 76, 459–466. doi: 10.1007/s00253-007-1010-0

Lugtenberg, B., and Kamilova, F. (2009). Plant-growth-promoting rhizobacteria. Annu. Rev. Microbiol. 63, 541–556. doi: 10.1146/annurev.micro.62.081307.162918

Maleki, M., Mokhtarnejad, L., and Mostafaee, S. (2011). Screening of rhizobacteria for biological control of cucumber root and crown rot caused by Phytophthora drechsleri. Plant Pathol. J. 27, 78–84. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.2011.27.1.078

Maniatis, T., Fritsch, E. F., and Sambrook, J. (1982). Molecular Cloning: A Laboratory Manual. New York, NY: Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory.

Manjula, K., Kishore, G. K., and Podile, A. R. (2004). Whole cells of Bacillus subtilis AF1 proved more effective than cell-free and chitinase-based formulations in biological control of citrus fruit rot and groundnut rust. Can. J. Microbiol. 50, 737–744. doi: 10.1139/W04-058

Merchant, I. A., and Packer, R. A. (1999). Veterinary Bacteriology and Virology, 8th Edn. New Delhi: CBS Publishers and Distributors.

Messiha, N. A. S., van Diepeningen, A. D., Farag, N. S., Abdallah, S. A., Janse, J. D., van Bruggen, A. H. C., et al. (2007). Stenotrophomonas maltophilia: a new potential biocontrol agent of Ralstonia solanacearum, causal agent of potato brown rot. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 118, 211–225. doi: 10.1007/s10658-007-9136-6

Mousivand, M., Jouzani, G. S., Monazah, M., and Kowsari, M. (2012). Characterization and antagonistic potential of some native biofilm-forming and surfactant-producing Bacillus subtilis strains against six pathotypes of Rhizoctonia solani. J. Plant Pathol. 94, 171–180. doi: 10.4454/jpp.v94i1.017

Nakayama, T., Homma, Y., Hashidoko, Y., Mizutani, J., and Tahara, S. (1999). Possible role of xanthobaccins produced by Stenotrophomonas sp. strain SB-K88 in suppression of sugar beet damping-off disease. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 65, 4334–4339.

Ng, L. C., Sariah, M., Sariam, O., Radziah, O., and Abi, M. A. Z. (2012). Rice seed bacterization for promoting germination and seedling growth under aerobic cultivation system. Aust. J. Crop. Sci. 6, 170–175.

Patten, C. L., and Glick, B. R. (2002). Regulation of indole acetic acid production in Pseudomonas putida GR12-2 by tryptophan and the stationary-phase sigma factor RpoS. Can. J. Microbiol. 48, 635–642. doi: 10.1139/w02-053

Rahman, A., Sitepu, I. R., Tang, S. Y., and Hashidoko, Y. (2010). Salkowski’s reagent test as a primary screening index for functionalities of rhizobacteria isolated from wild dipterocarp saplings growing naturally on medium-strongly acidic tropical peat soil. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 74, 2202–2208. doi: 10.1271/bbb.100360

Rajat, R. M., Ninama, G. L., Mistry, K., Parmar, R., Patel, K., and Vegad, M. M. (2012). Antibiotic resistance pattern in Pseudomonas aeruginosa species isolated at a tertiary care hospital. Ahmadabad. Natl. J. Med. Res. 2, 156–159.

Reysenbach, A. L., Giver, L. J., Wickham, G. S., and Pace, N. R. (1992). Differential amplification of rRNA genes by polymerase chain reaction. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 58, 3417–3418.

Riungu, G. M., Muthorni, J. W., Narla, R. D., Wagacha, J. M., and Gathumbi, J. K. (2008). Management of Fusarium head blight of wheat and deoxynivalenol accumulation using antagonistic microorganisms. Plant Pathol. J. 7, 13–19. doi: 10.3923/ppj.2008.13.19

Ryan, R. P., Monchy, S., Cardinale, M., Taghavi, S., Crossman, L., Avison, M. B., et al. (2009). The versatility and adaptation of bacteria from the genus Stenotrophomonas. Nat. Rev. 7, 514–525. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2163

Shirzad, A., Fallahzadeh-Mamaghani, V., and Pazhouhandeh, M. (2012). Antagonistic potential of fluorescent pseudomonads and control of crown and root rot of cucumber caused by Phytophthora drechsleri. Plant Pathol. J. 28, 1–9. doi: 10.5423/PPJ.OA.05.2011.0100

Simmons, J. S. (1926). A culture medium for differentiating organisms of typhoid-colon aerogenes groups and for isolation of certain fungi. J. Infect. Dis. 39:209. doi: 10.1093/infdis/39.3.209

Somasegaran, P., and Hoben, H. J. (1994). Handbook for Rhizobia: Methods in Legume-Rhizobium Technology. New York, NY: Springer-Verlag.

Stein, T. (2005). Bacillus subtilis antibiotics: structures, syntheses and specific functions. Mol. Microbiol. 56, 845–857. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04587.x

Tajini, F., MustaphaTrabelsi, M., and Drevon, J. J. (2012). Combined inoculation with Glomus intraradices and Rhizobium tropici CIAT899 increases phosphorus use efficiency for symbiotic nitrogen fixation in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 19, 157–163. doi: 10.1016/j.sjbs.2011

Turnbull, G. A., Morgan, J. A. W., Whipps, J. M., and Saunders, J. R. (2001). The role of bacterial motility in the survival and spread of Pseudomonas fluorescens in soil and in the attachment and colonisation of wheat roots. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 36, 21–31. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6941.2001.tb00822.x

Verma, J. P., Tiwari, K. N., and Kumar, A. (2013). Effect of indigenous Mesorhizobium spp. and plant growth promoting rhizobacteria on yields and nutrients uptake of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) under sustainable agriculture. Ecol. Eng. 51, 282–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2012.12.022

Vincent, J. M., and Humphrey, B. (1970). Taxonomically significant group antigens in Rhizobium. J. Gen. Microbiol. 63, 379–382. doi: 10.1099/00221287-63-3-379

Weisskopf, L., Heller, S., and Eberl, L. (2011). Burkholderia species are major inhabitants of white lupin cluster roots. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 77, 7715–7720. doi: 10.1128/AEM.05845-11

Yasmin, S., Bakar, M. A. R., Malik, K. A., and Hafeez, F. Y. (2004). Isolation, characterization and beneficial effects of rice associated plant growth promoting bacteria from Zanzibar soils. J. Basic Microbiol. 44, 241–252. doi: 10.1002/jobm.200310344

Zahid, M., Abbasi, M. K., Hameed, S., and Rahim, N. (2015). Isolation and identification of indigenous plant growth promoting rhizobacteria from Himalayan region of Kashmir and their effect on improving growth and nutrient contents of maize (Zea mays L.). Front. Microbiol. 6:207. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00207

Zhang, S., White, T. L., Martinez, M. C., McInroy, J. A., Kloepper, J. W., and Klassen, W. (2010). Evaluation of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria for control of Phytophthora blight on squash under greenhouse conditions. Biol. Control 53, 129–135. doi: 10.1016/j.biocontrol.2009.10.015

Keywords: PGPR, plant growth promotion, IAA production, biological nitrogen fixation, antagonism, Phytophthora capsici, disease suppression

Citation: Islam S, Akanda AM, Prova A, Islam MT and Hossain MM (2016) Isolation and Identification of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizobacteria from Cucumber Rhizosphere and Their Effect on Plant Growth Promotion and Disease Suppression. Front. Microbiol. 6:1360. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01360

Received: 16 August 2015; Accepted: 16 November 2015;

Published: 02 February 2016.

Edited by:

Anton Hartmann, Helmholtz Zentrum München – German Research Center for Environmental Health, GermanyReviewed by:

Abu Hena Mostafa Kamal, University of Texas at Arlington, USAChristian Staehelin, Sun Yat-sen University, China

Copyright © 2016 Islam, Akanda, Prova, Islam and Hossain. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Md. M. Hossain, aG9zc2Fpbm1tQGJzbXJhdS5lZHUuYmQ=

Shaikhul Islam

Shaikhul Islam Abdul M. Akanda

Abdul M. Akanda Ananya Prova

Ananya Prova Md. T. Islam

Md. T. Islam Md. M. Hossain

Md. M. Hossain