- 1Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Jiangsu University – School of Medicine, Zhenjiang, China

- 2Danyang People’s Hospital of Jiangsu Province, Danyang, China

Bacterial non-coding RNAs are essential in many cellular processes, including response to environmental stress, and virulence. Deep sequencing analysis of the Salmonella enterica serovar typhi (S. typhi) transcriptome revealed a novel antisense RNA transcribed in cis on the strand complementary to rseC, an activator gene of sigma factor RpoE. In this study, expression of this antisense RNA was confirmed in S. typhi by Northern hybridization. Rapid amplification of cDNA ends and sequence analysis identified an 893 bp sequence from the antisense RNA coding region that covered all of the rseC coding region in the reverse direction of transcription. This sequence of RNA was named as AsrC. After overexpression of AsrC with recombinantant plasmid in S. typhi, the bacterial motility was increased obviously. To explore the mechanism of AsrC function, regulation of rseC and rpoE expression by AsrC was investigated. We found that AsrC increased the levels of rseC mRNA and protein. The expression of rpoE was also increased in S. typhi after overexpression of AsrC, which was dependent on rseC. Thus, we propose that AsrC increased RseC level and indirectly activating RpoE which can initiate fliA expression and promote the motility of S. typhi.

Introduction

Non-coding RNAs (ncRNAs) are important in gene expression and regulation. In general, their transcription is activated in response to specific growth and stress conditions and their activities aid cells in recovering from stress (Waters and Storz, 2009). ncRNAs activities in controlling virulence and pathogenesis have been demonstrated for a number of gram-negative and gram-positive bacteria (Romby et al., 2006; Toledo-Arana et al., 2007). Most ncRNAs act by forming base pairs with target mRNAs. These base-pairing ncRNAs fall into two categories: trans-encoded ncRNAs and cis-encoded ncRNAs. The most extensively studied trans-encoded RNAs are coded by DNA at genomic locations distant from the mRNAs they regulate. They are thus only partially complementary to their target RNA(s) and regulate mRNAs by short, imperfect base-pairing interaction. Cis-encoded RNAs are transcribed from the DNA strand opposite the gene on bacterial chromosomes; these RNA are called antisense RNAs (asRNAs), and thus have perfect complementarity with their target (Storz et al., 2011).

Cis-encoded asRNAs are involved in a number of cellular processes in bacteria including replication initiation, conjugation efficiency, suicide, transposition, mRNA degradation, and translation initiation (Thomason and Storz, 2010). The known functional mechanisms employed by asRNAs include transcription attenuation, translation inhibition, promotion, or inhibition of mRNA degradation and preventing the formation of an activator RNA pseudoknot (Georg and Hess, 2011). Transcription of asRNAs has been discovered by computational prediction, oligonucleotide microarrays, or deep sequencing (Thomason and Storz, 2010). By deep RNA sequencing analysis of the transcriptome, we recently found many novel asRNAs in Salmonella enterica serovar typhi (S. typhi). Some have been found to be important in bacterial replication (Dadzie et al., 2013, 2014). One of the asRNAs coded from the strand opposite the rseC gene gets our attention.

The rseC gene is fourth in a four-gene operon (rpoE, rseA, rseB, rseC) and is cotranscribed with rpoE, rseA, and rseB in S. typhi. The regulatory protein σE (encoded by rpoE) is a member of the extracytoplasmic family of alternative sigma factors (Dartigalongue et al., 2001). The protein σE guides the core RNA polymerase in binding to the promoter region to initiate transcription of specific genes in response to the disturbance of envelope homeostasis caused by the accumulation of unfolded outer membrane proteins, damage to the outer membrane or oxidative and osmotic stress (Mecsas et al., 1993; Missiakas and Raina, 1997; Miticka et al., 2003). In unstressed conditions, σE activity is negatively regulated by RseA, an inner membrane protein that sequesters σE in an inactive form at the inner membrane (De Las Penas et al., 1997). Binding of RseB to the periplasmic domain of RseA might shift RseA to a conformation in which it is most effective as an anti-sigma factor, thus keeping σE activity low (De Las Penas et al., 1997). In contrast, RseC positively modulates the transcriptional activity of σE (Missiakas et al., 1997).

We describe here the identification and characterization of a novel cis-encoded antisense RNA of S. typhi rseC, which was named antisense RNA of rseC (AsrC), and demonstrate that the expression of this antisense RNA is critical for the motility of S. typhi.

Materials and Methods

Bacterial Strains, Plasmids, and Growth Conditions

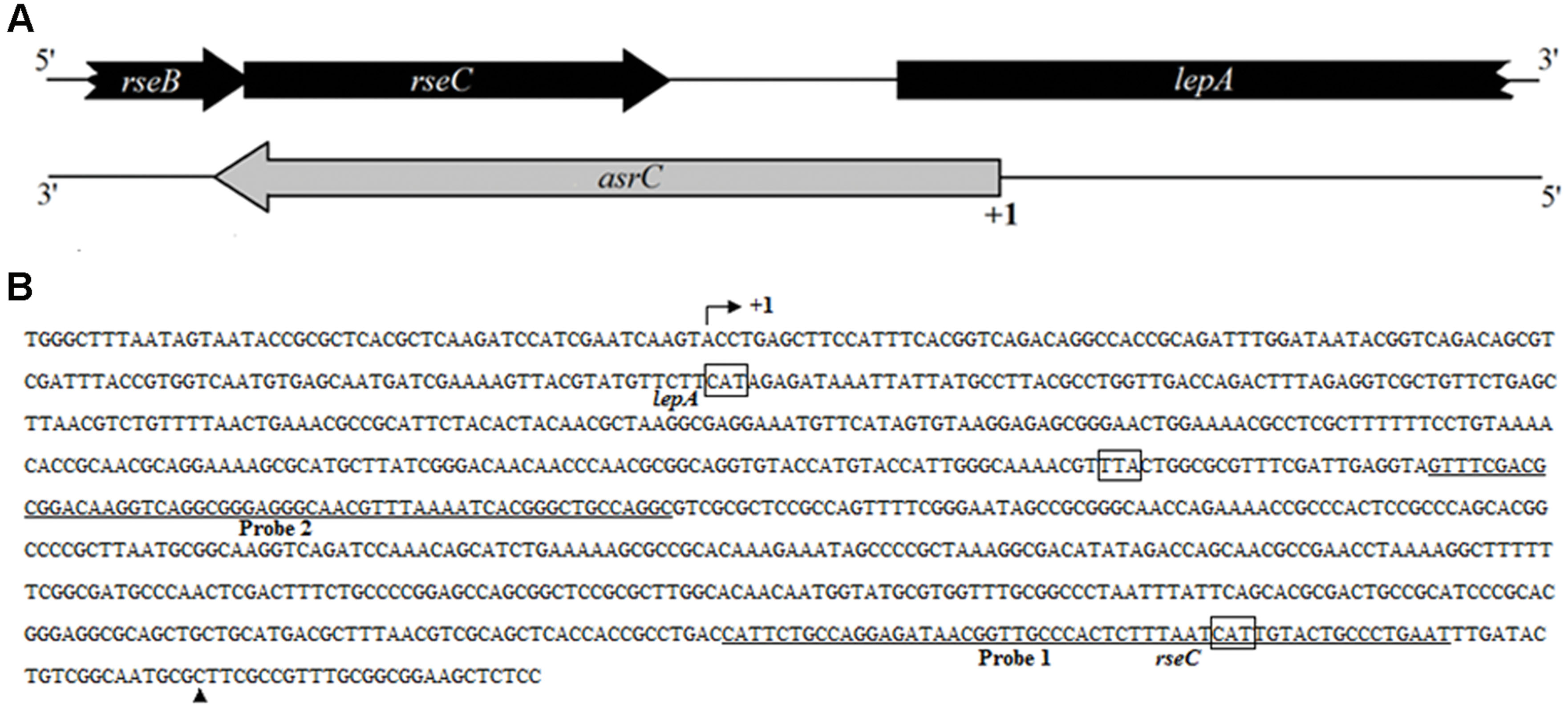

Strains and plasmids used in this study are in Table 1. S. typhi GIFU10007, a z66-positive wild-type strain was used as the parent strain for all mutants generated in this study. Unless otherwise noted, bacteria were incubated at 37°C in Luria-Bertani (LB) medium with shaking (250 rpm). When necessary, L-arabinose was added to induce the expression of plasmid-borne genes and antibiotics added to cultures were ampicillin (Ap; 100 μg/ml) and kanamycin (50 μg/ml).

Strain Construction

RseC mutant (ΔrseC), with whole ORF deleted, was conducted using a λ Red disruption system according to the method described previously with some modifications (Datsenko and Wanner, 2000). Briefly, a kanamycin-resistant gene was amplified by overlap-extension PCR from the template plasmid pET-28a with primers rseC-K1F/rseC-K1R and rseC-K2F/rseC-K2R, which apart from the region of complementarity with the kan sequences they were flanked with 89 bp ends homologous for the rseC gene. Electrocompetent cells containing the helper plasmid pKD46 were transformed with the purified PCR product. Successful recombinants were recovered by antibiotic selection and screened by PCR with the primers rseC-K2F and rseC-K2R for correct gene disruption. The promoter region of asrC (from +19 to -481) was deleted as described above using primer pairs AsrC-KF and AsrC-KR. Kanamycin-resistant gene was flanked by 50 bp of asrC sequences. AsrC-promoter mutant stain (ΔPasrC) was verified by PCR with primers AsrC-KF and AsrC-KR. S. typhi wild-type strain derivatives with chromosomally encoded FLAG-fusion proteins were constructed using the sucrose-sensitive suicide vector pGMB151. All constructs were verified by PCR and DNA sequencing.

Plasmid Construction

To construct the recombinant vector pBAD-asrC, a 1034 bp Nco I-Hind III fragment corresponding to the 893 bp asrC sequence and 140 bp upstream of asrC was amplified by PCR with primers pBAD-asrC PA/PB. Genomic DNA of the wild-type strain GIFU10007 was used as template. The amplicon was cloned into Nco I-Hind III sites of the vector pBAD/Myc-His A (Invitrogen). The wild-type strain GIFU10007 was transformed with the recombinant vector and used as the AsrC-overexpressing strain.

To construct a C-terminal 3 × FLAG-tagged fusion protein, primers rseC-F1A/1B, and rseC-F2A/2B were used to amplify fragments F1 (422 bp) and F2 (508 bp) from upstream and downstream of the rseC gene, respectively, using chromosomal DNA and overlap-extension PCR with Pfu Ultra DNA polymerase. FLAG sequences were integrated at the end of the rseC gene. F1 and F2 were used as template for a second PCR using primers rseC-F1A/F2B to obtain a 900 bp fragment with 66 bp FLAG DNA sequences. The 900 bp fragment was inserted into the Bam HI site of the suicide plasmid pGMB151, which carries a sucrose-sensitivity sacB gene. The suicide plasmid with the insert was electroporated into the S. typhi wild-type strain. Epitope insertion mutant strains cultured on LB plates with sucrose were screened by PCR with primers rseC-F1A/F2B.

RNA Extraction

Overnight cultures of S. typhi were diluted 1:100 in LB medium and grown at 37°C with shaking. To determine expression at different times, samples were taken at OD600 0.3, 0.8, 1.2, and 1.8. To determine expression under different stress conditions, bacteria were grown to OD600 0.4 and treated with 0.3 M NaCl for high osmotic stress or 4 mM hydrogen peroxide for oxidative stress. For acid stress, the pH of the culture medium was adjusted with HCl to 4.5. Cells were grown for 30 min after stress. For overexpression analysis, overnight cultures of bacteria carrying an empty pBAD/Myc-His A plasmid (WT+pBAD) and a plasmid expressing AsrC (WT+pBAD-asrC) were diluted 1:100 in LB medium and grown at 37°C to OD600 0.4. Overexpression was induced by addition of 0.2% (w/v) L-arabinose. Aliquots were taken prior to addition or maintained for the indicated time after L-arabinose addition. To extract total RNA, cultures were pelleted by centrifugation at 10,000 g for 2 min and RNAs were isolated using TRIzol (Invitrogen). RNA samples were treated with DNase I (Takara) to eliminate DNA contamination and quantified by ND-1000 Spectrophotometer (NanoDrop Technologies, Wilmington, DE, USA).

5′ and 3′ RACE Analysis

5′-rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACEs) used 5′-Full RACE kits (Takara) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 5 μg of total RNA was treated with 10 units of calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (1 h, 50°C) and 1 unit of tobacco acid pyrophosphotase (1 h, 37°C) and ligated to 250 pmol of supplied 5′ RACE adaptor with 40 unit of T4 RNA ligase (1 h, 16°C). Reverse transcription was at 42°C for 1 h with 5 units M-MLV reverse transcriptase and 25 pmol antisense RNA specific primer (5′ RACE RT). The cDNA was amplified with an adaptor-specific primer (5′ RACE outer primer) and asrC specific primer (5′ RACE GSP1). A second amplification was with 5′ RACE inner primer and 5′ RACE GSP2 using first PCR products as template. Purified PCR products were cloned into pGEM-T vector (Promega). Bacterial colonies were checked for appropriate inserts by PCR and confirmed by sequencing. The protocol for 3′-RACE was as described previously (Argaman et al., 2001). Briefly, total RNA (15 μg) was dephosphorylated with calf intestine alkaline phosphatase (Takara). RNA was ligated to 5′-phosphorylated 3′-RACE adaptor. Reverse transcription was performed as described for 5′-RACE with 3′-RACE adaptor-specific primer. Nested PCR was performed with 3′-RACE adaptor primer and asrC-specific primers (3′-RACE GSP1 and 3′-RACE GSP2). Cloning and sequence analysis were as described above.

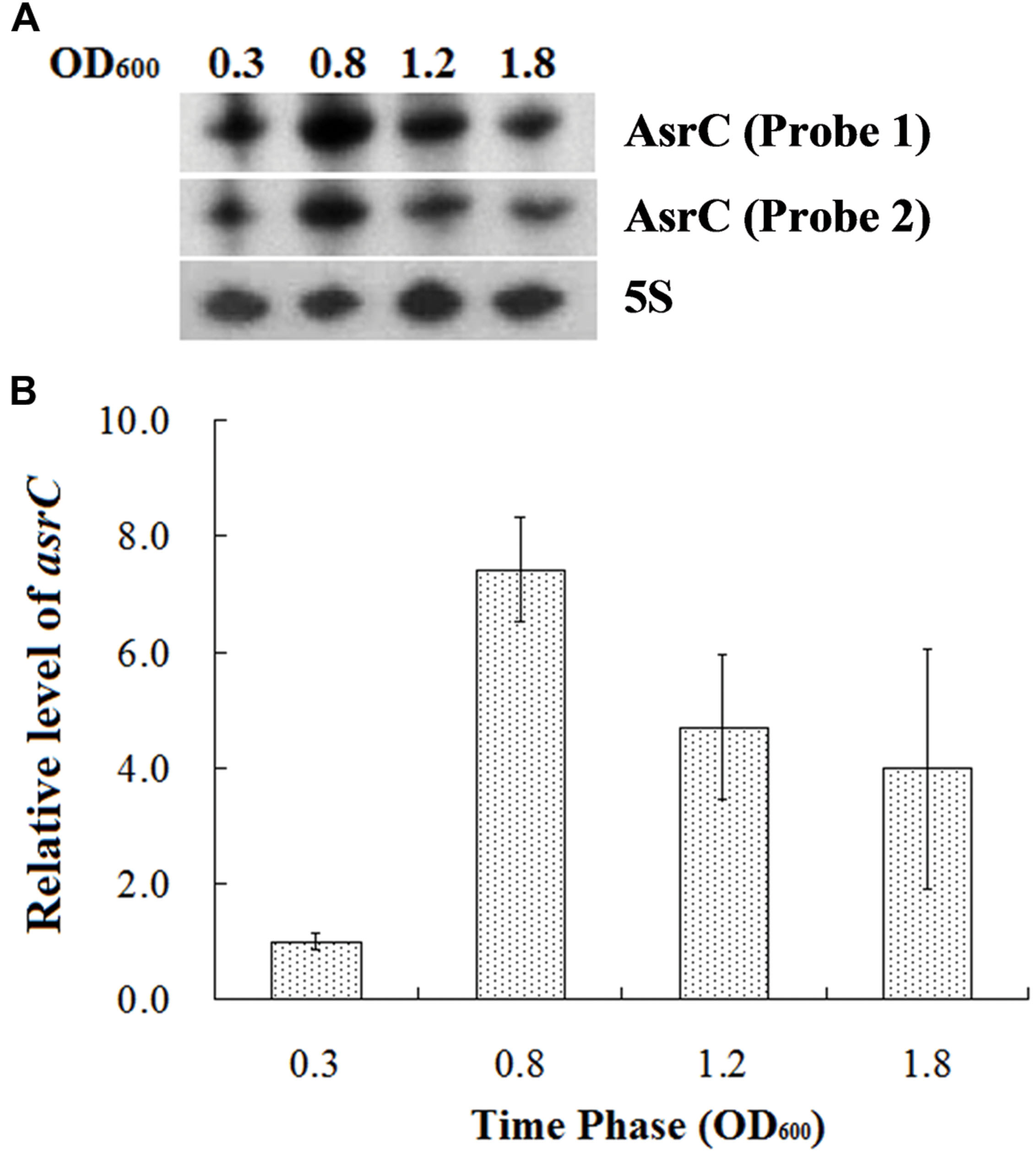

Northern Hybridization Analysis

Total RNA (5–30 μg) was separated on 7 M urea/6% polyacrylamide gels in 0.5 × TBE buffer and transferred to Hybond N+ membranes (GE Healthcare). Oligonucleotides (Table 2) were 5′-labeled with [γ-32P]-ATP by T4 polynucleotide kinase (Takara). Following prehybridization of membranes in Hyb hybridization buffer (Innogent) for 1 h at 42°C, membranes were hybridized overnight at 42°C. Membranes were washed twice with 2 × SSC + 0.05% SDS and twice with 0.1 × SSC + 0.1% SDS and exposed to KODAK X-Ray film at -70°C.

Quantitative Real-Time PCR

DNase I-treated total RNA (4 μg) was used for cDNA synthesis with PrimeScript Reverse Transcriptase (Takara) and gene-specific primers according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Quantification of cDNA used SYBR Premix Ex Taq II (Takara) and appropriate primers and was monitored using a C1000 Thermal Cycler (Bio-Rad) according to manufacturer’s instructions. Primer sequences are in Table 2. All samples were normalized against levels of 5S ribosomal RNA amplified with primers 5S-qF and 5S-qR. Relative mRNA levels were determined by the comparative CT method (Livak and Schmittgen, 2001). Each experiment was performed in triplicate.

Motility Assay

Swimming motility was evaluated on LB plates containing 0.3% (w/v) agar. Bacterial strains were grown in LB broth at 37°C overnight, diluted 1:100 and incubated to OD600 0.4. L-arabinose was added to induce AsrC expression for 1 h. Bacterial cultures (2.5 μl) were incubated on spots on swimming plates at 37°C for 8 h. Motility was assessed by measuring the circular swim formed by the growing motile cells. Experiments were carried out triplicate.

Western Blot Analysis

After L-arabinose-induction, bacterial cells were cultured for the indicated time (normalized to the optical density at OD600) before harvest, pelleted, and washed once with an equal volume of PBS buffer. Final pellets were resuspended in PBS buffer and maintained on ice during sonication for the minimum time required to observe cleared lysate (10 s each at 1 min intervals) with an CL4 probe in a XL2020 Ultrasonic Processor (Misonix, Inc., Farmingdale, NY, USA). Supernatants of bacterial cultures after ultrasonic treatment were used for Western blots. Samples were separated on 15% polyacrylamide gels and proteins were electrophoretically transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membranes. Membranes were treated with 5% non-fat dried milk in Tris-buffered saline, incubated with anti-FLAG (CMC Scientific), anti-RpoE (Santa Cruz Biotechology), or anti-DnaK antibodies (Enzo Life Sciences) raised in mice and subsequently incubated with anti-mouse immunoglobulin G linked to horseradish peroxidase. Crossreactive proteins were detected with ECL plus Western blotting detection reagents (Thermo Scientific).

Statistical Analysis

Data are presented as means ± SE. Statistical analysis was performed with Student’s t-test. Significance was defined as P < 0.05.

Results

Identification and Characterization of AsrC Expression in S. typhi

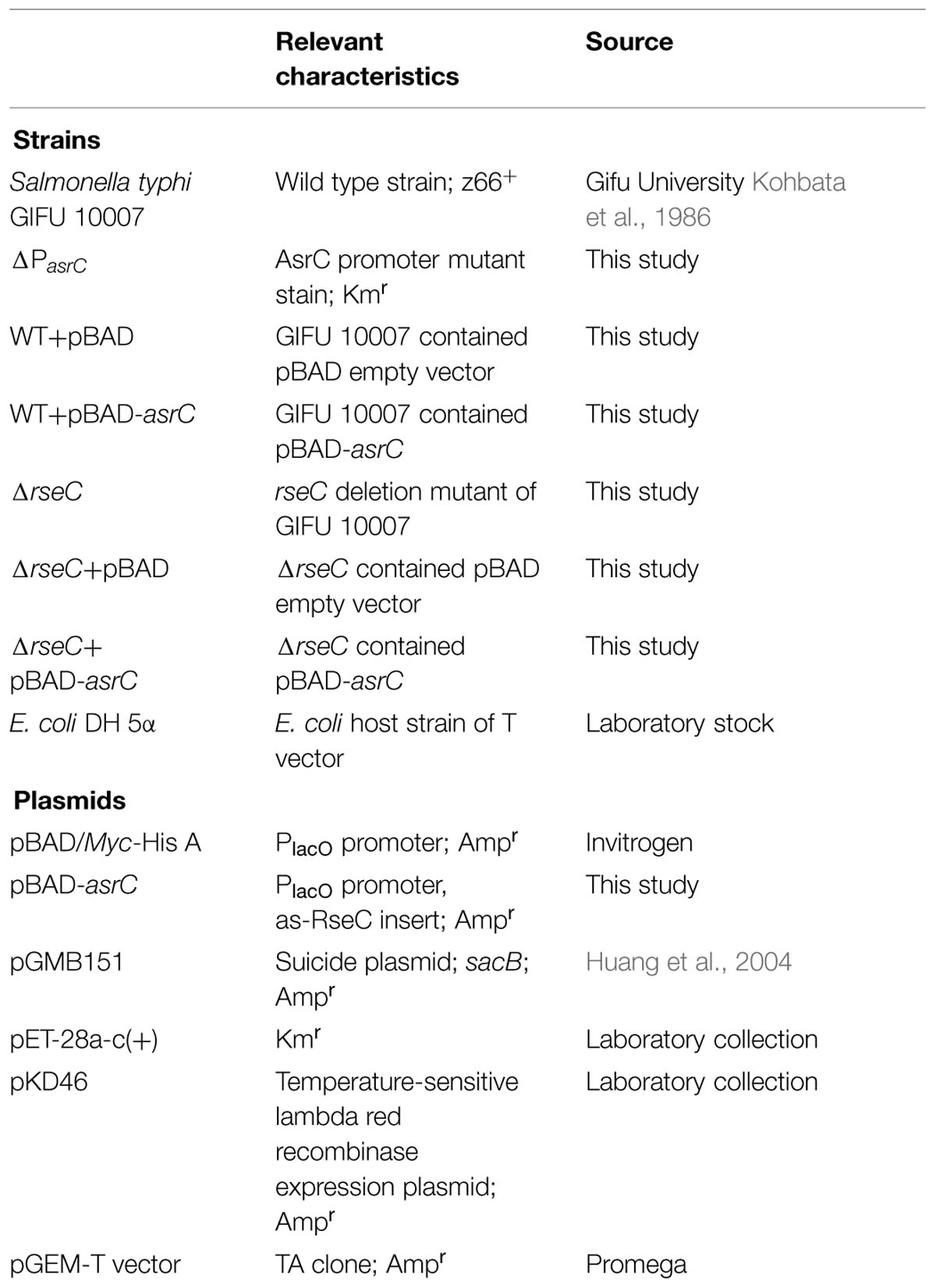

By transcriptome analysis of S. typhi, several new ncRNAs were found, including a putative antisense RNA for rseC. To determine the boundaries of the putative novel ncRNA, rapid amplification of cDNA ends (RACEs) was used. Results of 5′-RACE and 3′-RACE revealed the 5′-end of the transcript, which was 119 bp downstream of the lepA start codon. The 3′-end of the transcript was 36 bp upstream of the rseC start codon, indicating a full-length transcript of 893 nt. The gene structure and sequence of the transcript are in Figure 1. End mapping revealed that the novel transcript was transcribed in cis from the strand complementary to rseC and overlapped the entire rseC mRNA. We therefore named it AsrC. From the entire sequence of the novel asRNA, no obvious ORF structure longer than 150 nt or SD element was found. Thus, we hypothesized that the novel asRNA was an ncRNA.

FIGURE 1. Schematic representation and sequence analyses of asrC. (A) Genomic location of asrC. Black arrows, location of rseB, rseC, and lepA genes; gray arrows, position of asrC. (B) Sequence analysis by RACE of the AsrC. Bent arrow, transcription start site; +1 and ▲, experimentally determined transcription start site and transcription stop site of the asrC, respectively; underlined sequence, two different positions of oligonucleotide probes used for Northern hybridization for AsrC expression.

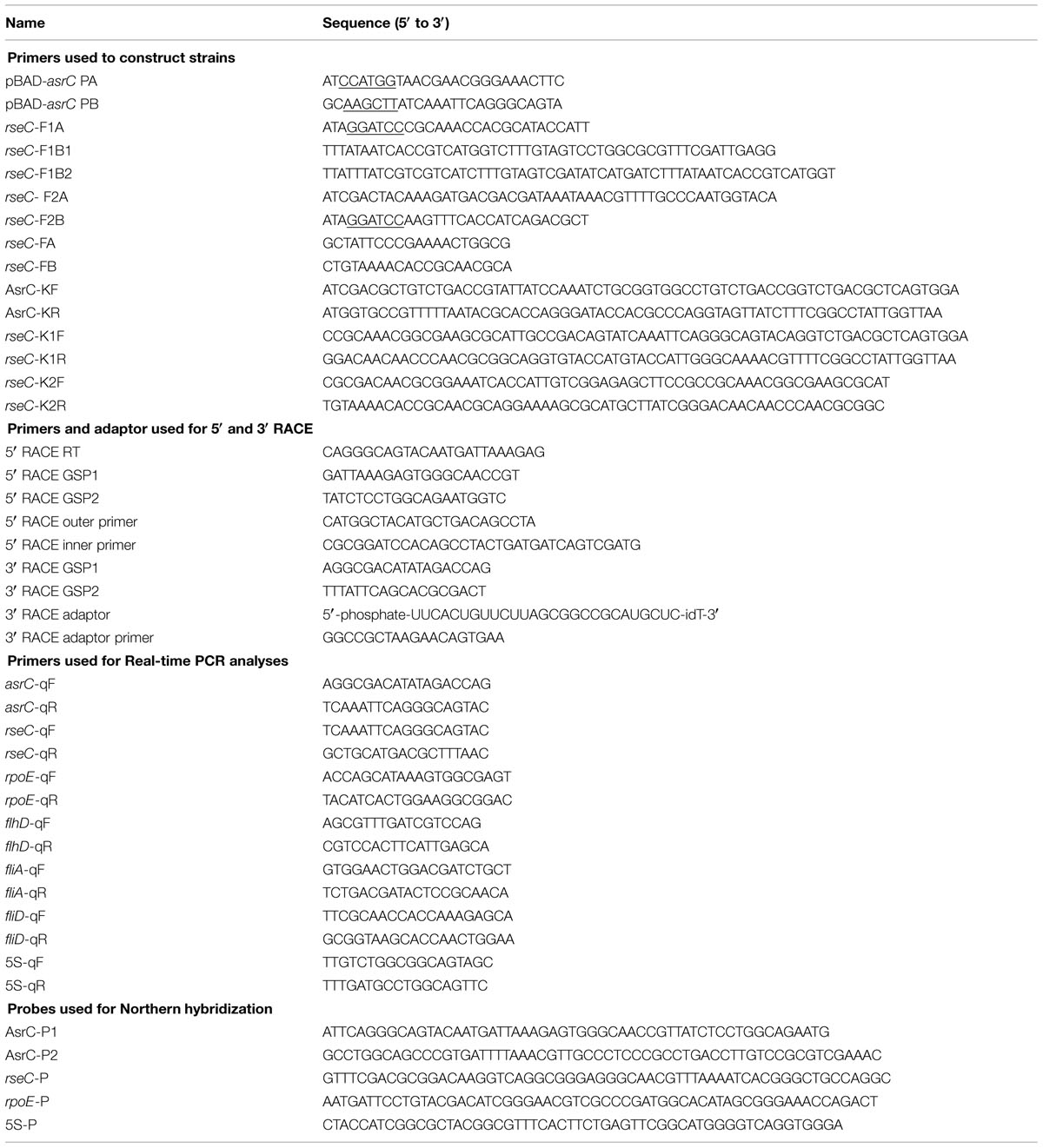

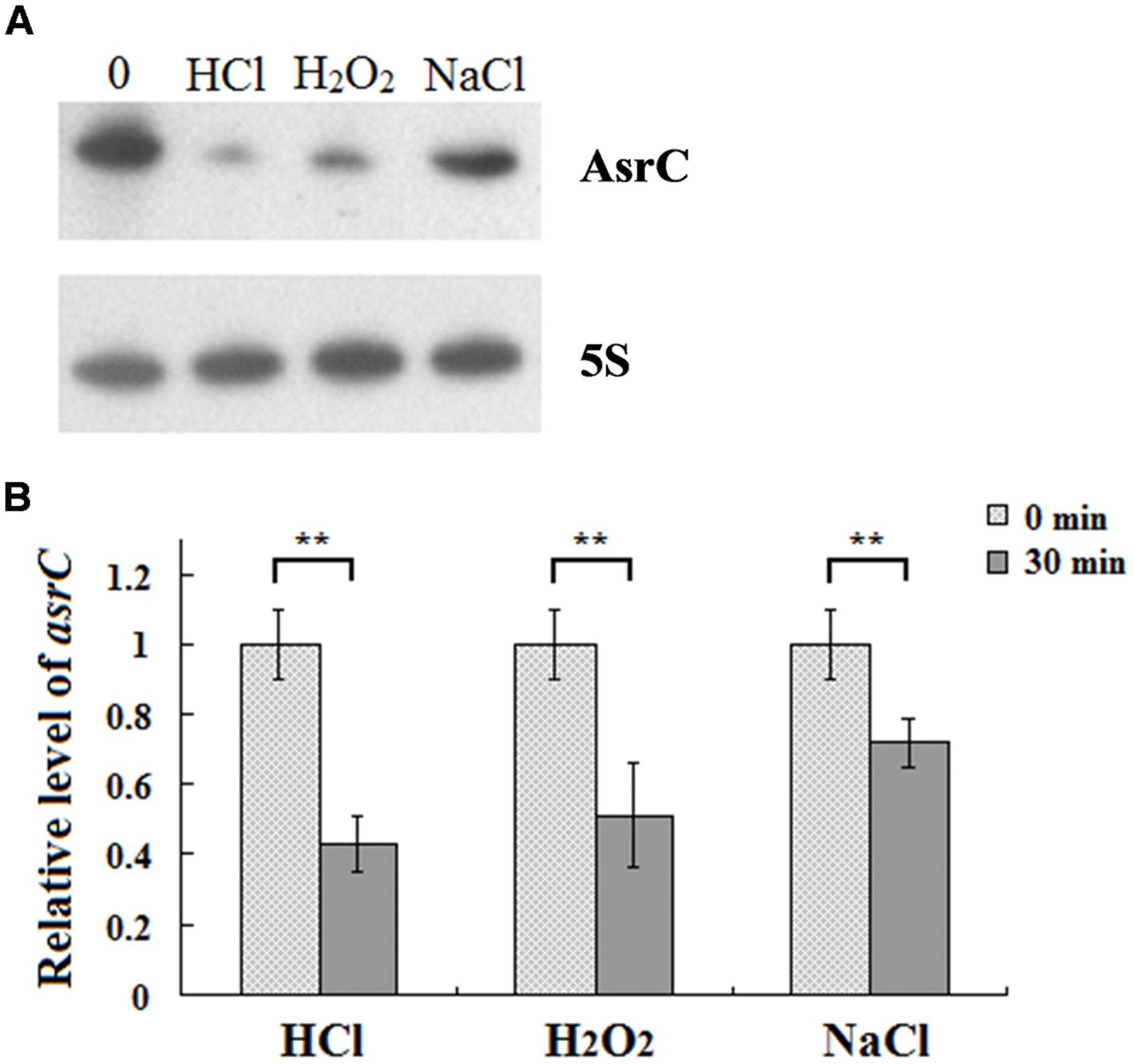

To understand the expression characteristics of asrC, RNA was harvested from wild-type S. typhi at different times and under different stress conditions and analyzed by Northern hybridization and qRT-PCR. Total RNA from a S. typhi wildtype strain was collected at OD600 0.3, 0.8, 1.2, and 1.8, representing bacterial growth phases from lag through stationary. Two oligonucleotide probes specific to different regions of the asrC gene (Figure 1B) were designed for Northern hybridization. AsrC RNA was detected by both probes mainly in late log and early stationary phase (Figure 2A). The expression pattern of asrC was observed by qRT-PCR (Figure 2B). Expression of asrC was also determined under stress conditions reflecting the Salmonella environment upon invasion of a host or within macrophages. Total RNA was extracted from wild-type after cells were subjected to acidic, oxidative, or osmotic stress. Northern hybridization and qRT-PCR analysis showed that expression of asrC was reduced in acidic, oxidative conditions (Figures 3A,B). These results suggested that the novel asRNA AsrC was expressed in S. typhi and that expression was regulated by environmental conditions.

FIGURE 2. Expression of AsrC at different times. (A) Total RNA was extracted at OD600 0.3, 0.8, 1.2, and 1.8 and 5 μg total RNA was loaded into gels, separated on a 7 M urea/6% polyacrylamide gels and transferred to a membranes. Probes 1 and 2 for two regions were used for Northern hybridization. 5S rRNA was the loading control. (B) qRT-PCR to measure AsrC at different times. 5S rRNA was the internal reference.

FIGURE 3. Expression of AsrC under stress conditions. (A) Northern hybridization and (B) qRT-PCR of total RNA isolated from Salmonella typhi cells grown in LB to OD600 0.4 and subjected for 30 min to acid stress (HCl: pH 4.5), oxidative stress (H2O2: 4 mM hydrogen peroxide) or osmotic shock (NaCl: 0.3 M NaCl). Internal reference was 5S rRNA. ∗∗P < 0.01 compared with control group.

AsrC Eexpression Enhances S. typhi Motility

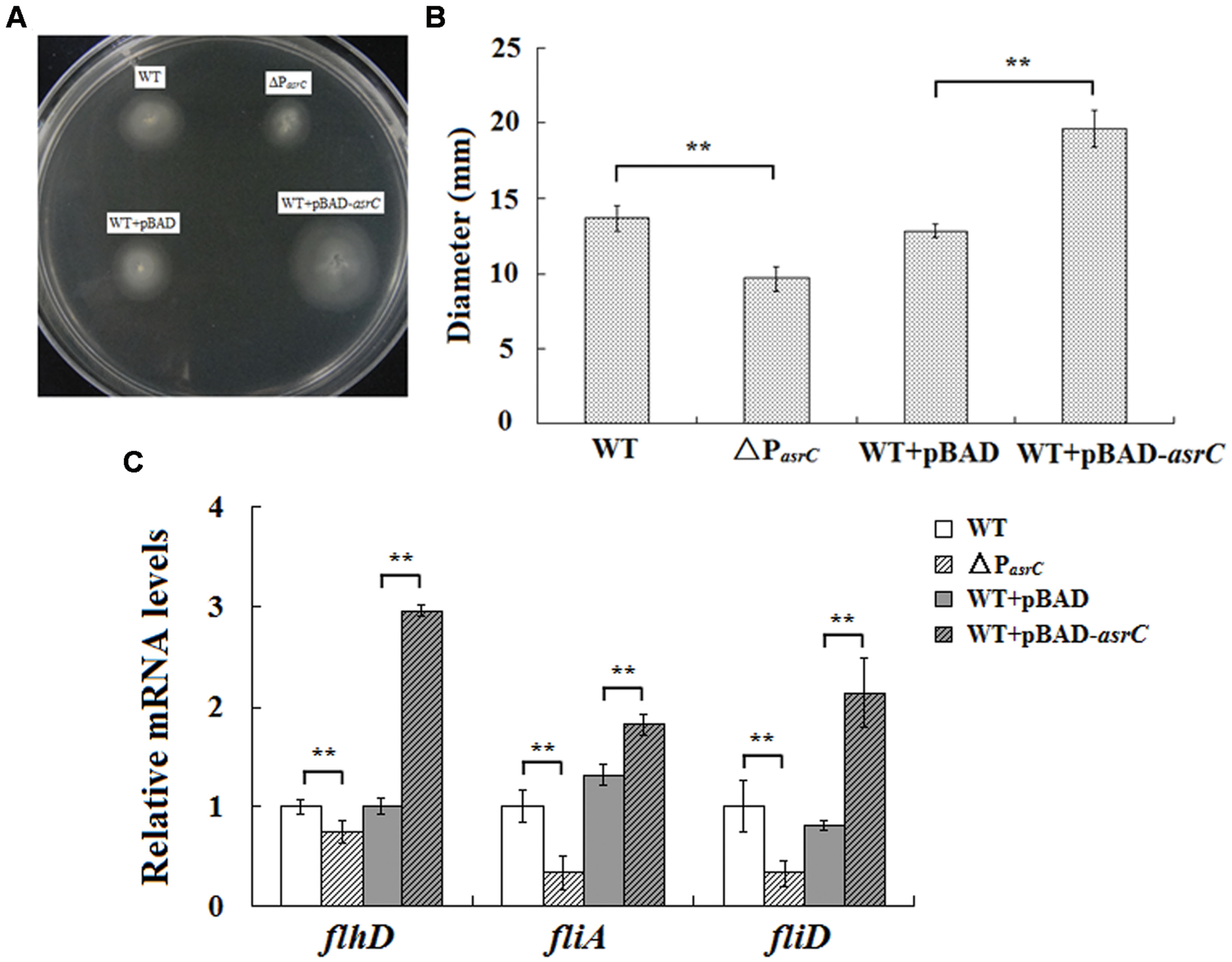

To investigate the function of the AsrC, the asrC-promoter mutant stain (ΔPasrC) of S. typhi was prepared. qRT-PCR results showed that asrC had almost no expression in ΔPasrC strain (Supplementary Figure S1). Overexpression of AsrC was performed in S. typhi which was transformed by a recombinant plasmid pBAD-asrC and induced with L-arabinose. The motility of S. typhi influence by the AsrC was assessed by using motility-swim agar plates. The motility of ΔPasrC was significantly decreased compared to the wild-type strain (WT). After overexpression of AsrC, S. typhi (WT+pBAD-asrC) had significantly increased motility compared to the control strain (WT+pBAD; Figures 4A,B). Transcript levels of flagellar genes flhD, fliA, and fliD were compared among WT, ΔPasrC, WT+pBAD, and WT+pBAD-asrC strains using qRT-PCR. Expression of flhD, fliA, and fliD in the mutant stain ΔPasrC was decreased compared to the WT strain and increased in the WT+pBAD-asrC strain compared to the empty-plasmid control (Figure 4C). LepA complementary strain and control strain were constructed by transferring the recombinant plasmid pBAD-lepA and the empty vector pBAD/gIII into the ΔPasrC mutant strain. Expression of flagella-related genes of the two strains was observed to be identical (data not shown). These results suggested that AsrC can up-regulate S. typhi motility.

FIGURE 4. Motility assay of the wild type, ΔPasrC, WT+pBAD and WT+pBAD-asrC strains. (A) AsrC-promoter mutant strain with decreased motility. Overexpression of AsrC increased motility on swim-agar plates. (B) Motility ring diameters of S. typhi strains. Bacterial were spotted onto LB plates with 0.3% agar and incubated at 37°C for 8 h. The image is representative of three independent experiments. (C) mRNA of flagellar genes (flhD, fliA, and fliD) determined by qRT-PCR. RNA was extracted from three independent cultures for each strain grown to OD600 0.4. Levels of 5S rRNA were the internal reference. ∗∗ P < 0.01 compared with control group.

Overexpression of AsrC Increases rseC mRNA and Protein Levels

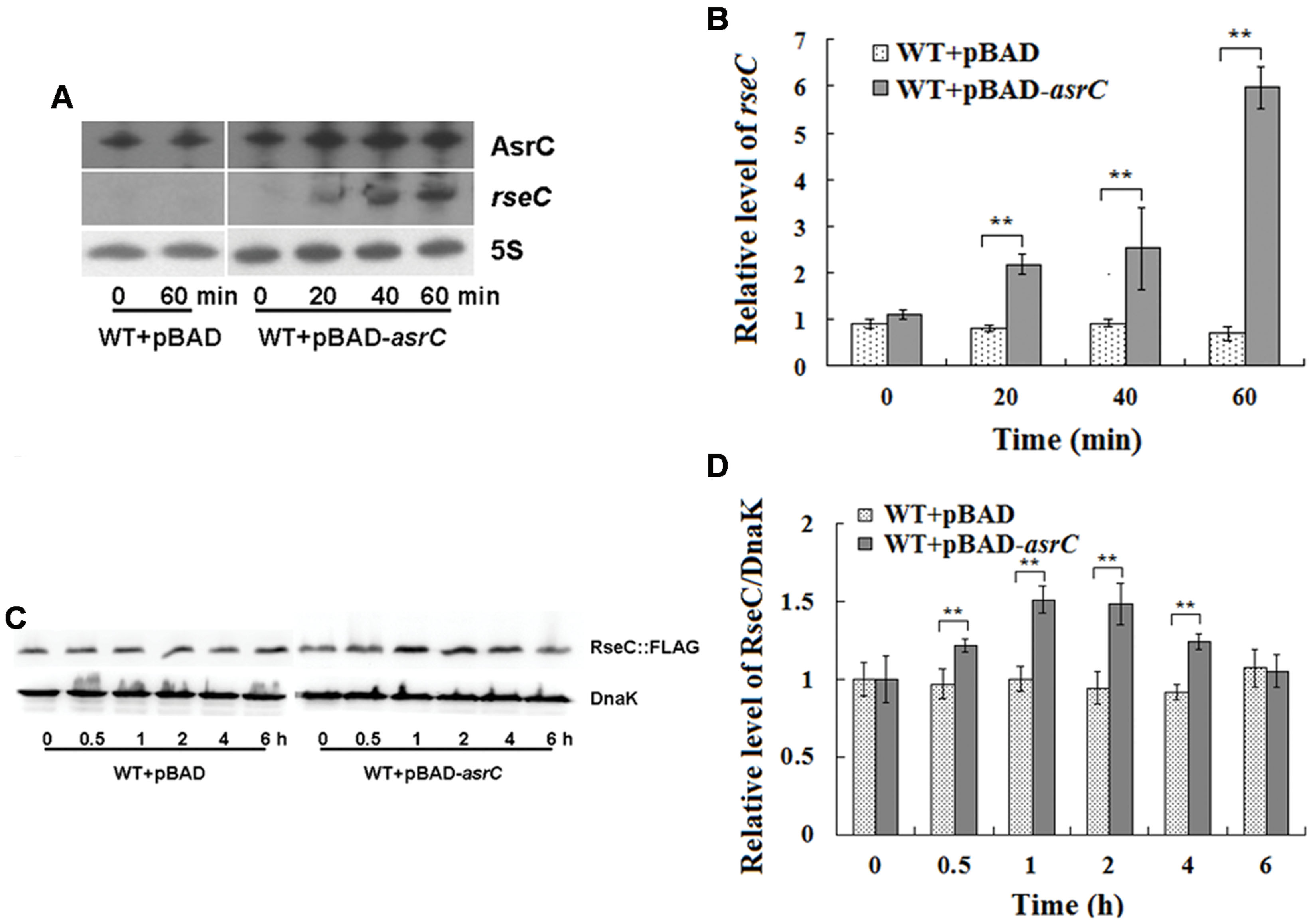

AsrC is transcribed from the DNA strand opposite the rseC gene and therefore has perfect complementarity with rseC mRNA. To investigate the effect of asrC expression on resC levels, WT+pBAD and WT+pBAD-asrC strains were grown to exponential phase (OD600 0.4) and treated with L-arabinose for 0, 20, 40, or 60 min. Changes in mRNA abundance were monitored by Northern hybridization. The mRNA level of rseC increased time-dependently when AsrC was overexpressed, but no additional increase was seen in the WT+pBAD strain (Figure 5A). These results were confirmed by qRT-PCR. The mRNA level of rseC was significantly higher when AsrC was overexpressed compared to the WT+pBAD strain (Figure 5B). The effect of AsrC overexpression on the protein level of RseC was analyzed. Western blots showed an increase in RseC protein levels in the WT+pBAD-asrC strain compared to the WT+pBAD strain during induction of asrC expression for the first 4 h with recovery to basal level at 6 h. No significant expression difference was observed in the WT+pBAD control strain (Figures 5C,D). The mRNA level of rseC was also detected in ΔPasrC lepA complementary (ΔPasrC+pBAD-lepA) strain and WT+pBAD control strain. qRT-PCR results showed that rseC expression significantly decreased in ΔPasrC+pBAD-lepA strain compared to WT+pBAD control strain (Supplementary Figure S2). These observations suggested that AsrC might be vital for in increasing rseC mRNA and protein levels.

FIGURE 5. Overexpression of AsrC increased rseC mRNA and protein expression levels. mRNA levels of resC were assessed by Northern hybridization (A) and qRT-PCR (B). Total RNA from wild-type (WT+pBAD) and overexpression strain (WT+pBAD-asrC) grown to OD600 0.4 at 0, 20, 40, and 60 min after addition of L-arabinose (0.2% final concentration). Levels of 5S rRNA were the internal reference. (C) Western blot profile of RseC protein relative to DnaK in WT+pBAD and WT+pBAD-asrC strains. Representative blots are shown. (D) Quantitation of RseC protein based on Western blots. Proteins were isolated from WT+pBAD and WT+pBAD-asrC strains grown to OD600 0.4 at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 4, and 6 h after addition of L-arabinose (0.2% final concentration). Experiments were repeated three times and error bars indicate standard deviations. ∗∗P < 0.01 compared with control group.

Overexpression of AsrC Increases rpoE mRNA and Protein Levels

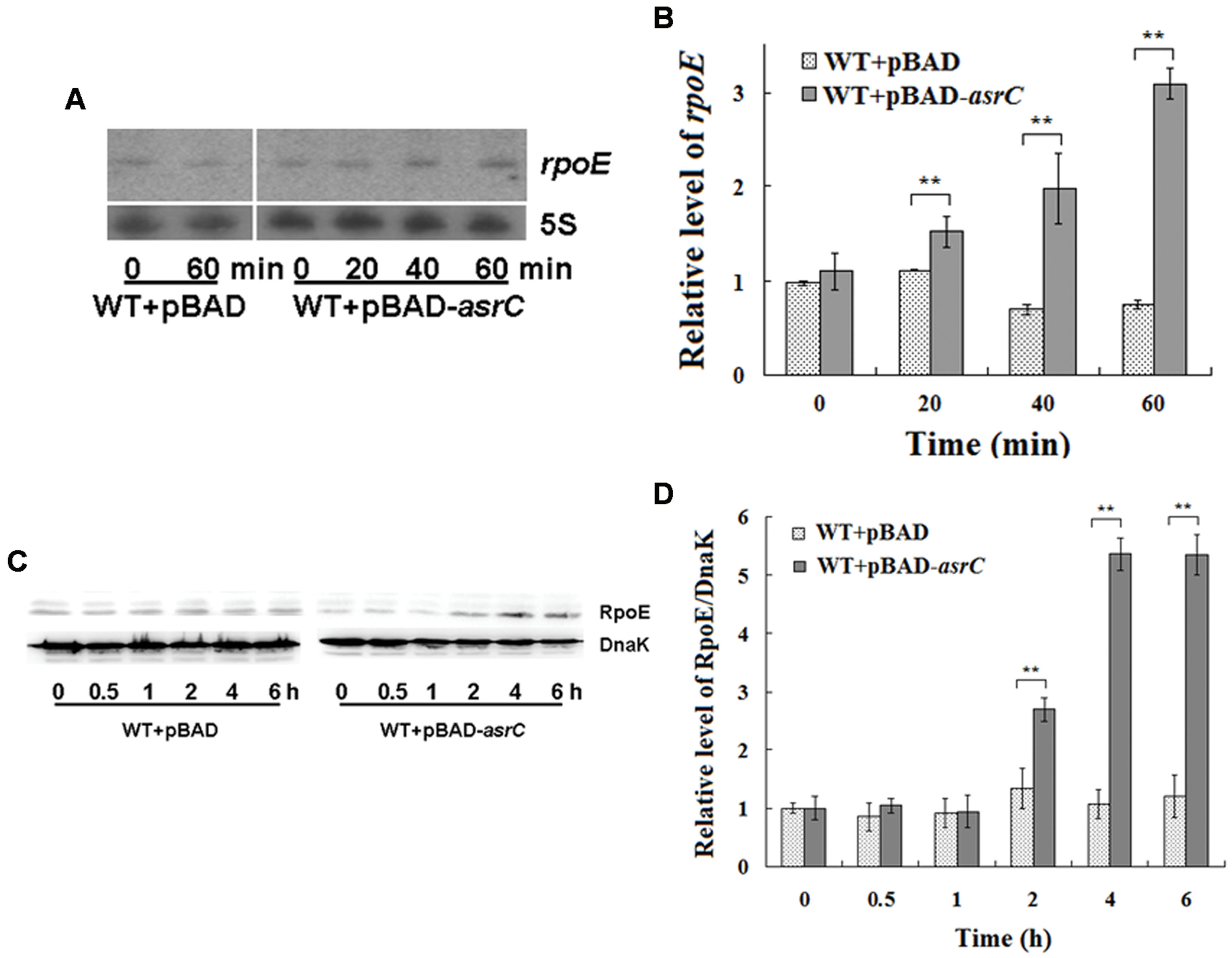

The last gene of the rpoE operon is rseC. RseC positively modulates the transcriptional activity of σE (Missiakas et al., 1997). Thus, we investigated if AsrC overexpression influenced the expression of rpoE. Northern hybridization and qRT-PCR both showed that overexpression of AsrC increased rpoE mRNA, but the WT+pBAD control strain displayed no significant differences in rpoE mRNA level after L-arabinose induction for 60 min (Figures 6A,B). The level of rpoE mRNA increased about threefold after 60 min of L-arabinose induction in the WT+pBAD-asrC strain (Figure 6B). RpoE protein increased time-dependently after AsrC overexpression was induced (Figure 6C). Western blot quantification showed that RpoE protein was significantly elevated after L-arabinose induction for 2 h and reached a maximum (5.3-fold) after induction for 4 h (Figure 6D). Expression of rpoE was also detected in ΔPasrC+pBAD-lepA strain and WT+pBAD control strain. qRT-PCR results showed that mRNA level of rpoE significantly decreased in ΔPasrC+pBAD-lepA strain compared to WT+pBAD control strain (Supplementary Figure S2). These results indicated that expression of RpoE was positively affected by AsrC.

FIGURE 6. Overexpression of AsrC increased rpoE mRNA and protein. RpoE mRNA assessed by Northern hybridization (A) and qRT-PCR (B). Total RNAs were isolated from WT+pBAD and WT+pBAD-asrC strains grown to OD600 0.4 at 0, 20, 40, and 60 min after addition of L-arabinose (0.2% final concentration). Levels of 5S rRNA were the internal reference. (C) Western blot of RpoE protein relative to DnaK in WT+pBAD and WT+pBAD-asrC strains. Representative blots are shown. (D) Quantitation of RpoE protein levels based on Western blots. Experiments were repeated three times and error bars indicate standard deviations. ∗∗P < 0.01 compared with control group.

AsrC Increases rpoE mRNA and Protein Through rseC

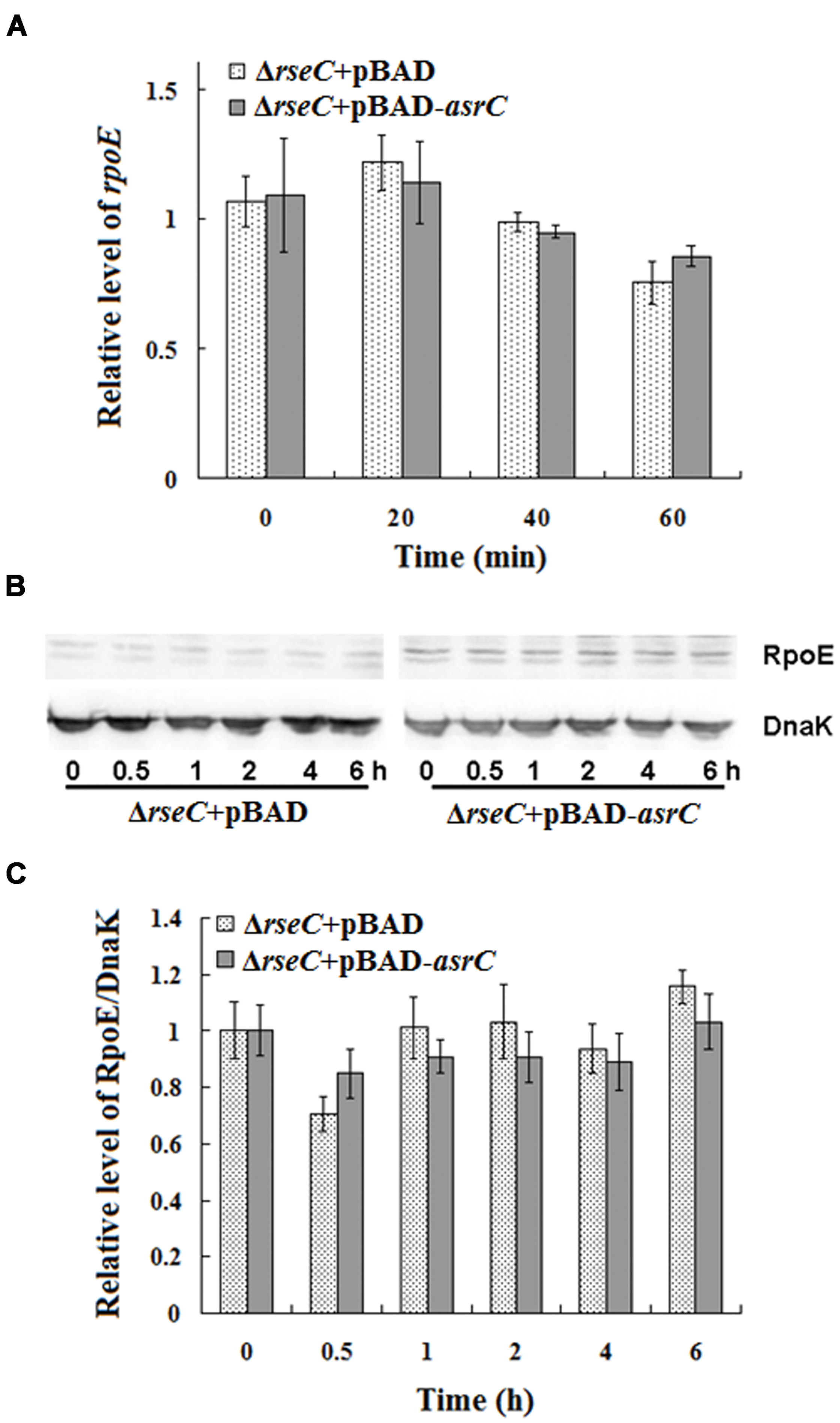

The results above indicated that AsrC overexpression increased rseC and rpoE mRNA and protein. RseC positively modulate σE (RpoE) activity (Missiakas et al., 1997), suggesting that AsrC might elevate rpoE mRNA and protein through increased transcription and translation of rseC. We investigated rpoE mRNA and protein in an rseC mutant containing a pBAD-asrC plasmid (ΔrseC+pBAD-asrC) or pBAD control plasmid (ΔrseC+pBAD). No significant expression difference in mRNA or protein was observed between the ΔrseC+pBAD-asrC strain and the ΔrseC+pBAD control strain (Figures 7A–C). These results indicated that increased rpoE mRNA and protein induced by AsrC overexpression was rseC dependent, primarily through increasing rseC transcription and translation.

FIGURE 7. Expression of rpoE mRNA and protein in rseC mutant strain after overexpression of AsrC. (A) qRT-PCR for rpoE mRNA levels in ΔrseC+pBAD and ΔrseC+pBAD-asrC strains. Total RNA was isolated from ΔrseC+pBAD and ΔrseC+pBAD-asrC strains grown to OD600 0.4 at 0 min, 20 min, 40 min, and 60 min after addition of L-arabinose (0.2% final concentration). Levels of 5S rRNA were the internal reference. (B) Western blot of RpoE protein relative to DnaK in ΔrseC+pBAD and ΔrseC+pBAD-asrC strains. (C) Quantitation of RpoE protein based on Western blots. Proteins were isolated from ΔrseC+pBAD and ΔrseC+pBAD-asrC strains grown to OD600 0.4 at 0 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h and 6 h after addition of L-arabinose (0.2% final concentration). Experiments were repeated three times and error bars indicate standard deviations.

Discussion

Most ncRNAs are transcribed and accumulate in the stationary phase of bacterial growth and under specific stress conditions (Wassarman et al., 2001; Vogel et al., 2003). Bacteria prepare for these conditions by upregulating a number of genes and regulators to cope with environmental changes. Numerous ncRNAs of bacterial pathogens affect the expression of virulence genes (Pichon and Felden, 2005; Papenfort and Vogel, 2010). RNA III of Staphylococcus aureus was the first regulatory ncRNA shown to be involved in bacterial pathogenicity (Novick et al., 1993). Recently, we found many novel asRNAs in S. typhi by RNA-seq analysis (Dadzie et al., 2013, 2014). A transcript that overlaps the entire mRNA sequence of rseC was found in S. typhi. We identified an 893 nt sequence of a putative novel ncRNA by RACE. This sequence was transcribed from 119 nt downstream of the lepA start codon to the last 40 nt of rseB (Figure 1). No obvious ORF structure longer than 150 nt or an SD element was found in the entire sequence. Therefore, we believe this is a novel ncRNA. The novel ncRNA AsrC is transcribed in cis from the strand complementary to rseC and overlaps the entire rseC mRNA.

Using Northern hybridization, we confirmed expression of AsrC in S. typhi. We determined the expression characteristics of AsrC in S. typhi during different growth phases and under selected stress conditions using Northern hybridization and qRT-PCR.

The abundance of the asrC transcript is highest during late exponential phase (Figure 2). Transcription of asrC was regulated in different environmental conditions (Figure 3). Transcription of ncRNAs in general is activated in response to specific growth and stress conditions and their activities aid cells in recovery from those stresses (Waters and Storz, 2009).

According to the expressional characteristics of AsrC, we suspected that is a functional product in S. typhi. Effect of AsrC expression on the bacterial phenomenon was investigated at first. In this study, we could not find obvious difference in growth curve between the AsrC mutant strain ΔPasrC and the wild type strian of S. typhi (data not shown). Results obtained from motility assays indicate that expression changes of asrC resulted in variation in swimming motility (Figure 4), implying that AsrC plays an important role in bacterial motility. Flagella are cell surface appendages involved in a number of bacterial behaviors, including motility (Chilcott and Hughes, 2000; Yang et al., 2012). The flagellar genes are organized into a transcriptional hierarchy with three promoter classes (class 1, 2, and 3). Class 1 promoters drive expression of the flagellar master operon that encodes the transcription factors FlhD and FlhC. Class 3 flagellar genes are regulated by FliA, encoded by class 2 gene fliA, which activates a third group of genes, class 3, needed for final flagellar assembly (Chilcott and Hughes, 2000). The fliD gene, which belongs to class 2, encodes the filament-cap protein of the flagellar apparatus (Ohnishi et al., 1990; Ikebe et al., 1999; Chilcott and Hughes, 2000). We used qRT-PCR approach to identify relative mRNA expression of flagella genes flhD, fliA, and fliD in the AsrC mutant and overexpression strains. AsrC mutant decreased the expression of flhD, fliA, and fliD and overexpression of AsrC increased the flhD, fliA, and fliD expression (Figure 4). The 5′-end of AsrC is 119 nt downstream of the lepA start codon, so mutation of the AsrC promoter region might influence lepA expression. Therefore, we constructed a lepA complementary strain and control strain by transferring the recombinant plasmid pBAD-lepA and the empty vector pBAD/gIII into the ΔPasrC mutant strain. No significant differences in expression of flagella-related genes were observed compared to pBAD-lepA and pBAD control strains (data not shown).

We previously found that RpoE can promote Salmonella flagellar gene expression and motility (Du et al., 2011). RseC was reported as a positive modulater of RpoE (σE), as overproduction from a multicopy plasmid led to an increase in transcriptional σE activity (Missiakas et al., 1997). RseC fine-tunes the interaction of RseA and RseB with σE and is associated with other bacterial functions. RseC maintains the reduced state of SoxR, one of two transcription factors that sense the presence of oxidants and induce genes against oxidative stress (Koo et al., 2003). RseC is reported to be involved in synthesis of the pyrimidine ring of thiamine, which is a requirement for conversion of aminoimidazole ribotide to the 4-amino-5-hydroxymethyl-2-methyl pyrimidine in S. enterica serovar typhimurium (Beck et al., 1997). RseC and proteins such as ApbC and ApbE and glutathione participate in Fe-S cluster repair (Skovran et al., 2004). We observed that overexpression of AsrC led to a significant increase in rseC mRNA and enhanced its translation, which was confirmed by Western blot analysis (Figure 5). This result was consistent with the observation that many sense-antisense pairs exhibit positively coregulated expression profiles that indicate possible involvement of antisense RNAs in stabilizing cis-encoded mRNAs (Chinni et al., 2010).

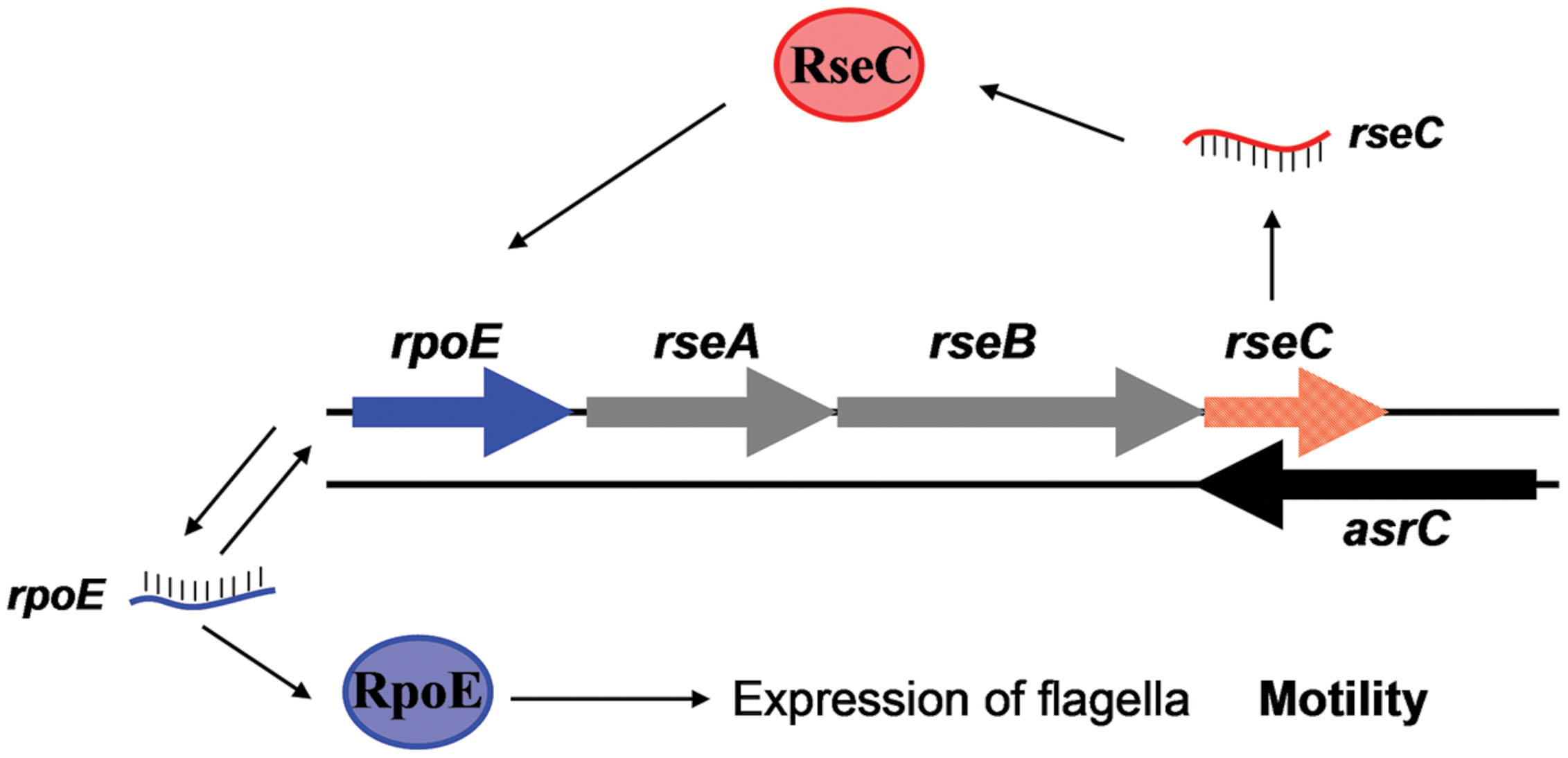

The protein σE is involved in the response to extracytoplasmic stresses and initiates transcription of a series of genes in Escherichia and Salmonella under environmental stress, for example, high osmolarity and oxidative stress (Testerman et al., 2002; Miticka et al., 2003; Rolhion et al., 2007). In our study, AsrC overexpression increased rpoE mRNA and protein, probably by enhancing transcription and translation of rseC (Figure 6). RseC protein began to increase after 0.5 h of AsrC induction and RpoE increased after 2 h of induction, 1.5 h later than RseC. Increased RpoE protein appeared later than RseC protein, suggesting that AsrC induced RpoE expression through enhancing expression of RseC. Our results showed that AsrC was expressed throughout S. typhi growth, with the highest expression during late exponential phase (Figure 2), and rpoE mRNA were increased ∼16-fold during the transition to stationary phase (Testerman et al., 2002). The enhancement of rpoE expression could be partly due to increased expression of asrC mRNA, which is resulted in an increase in rseC expression. In our observation, overexpression of AsrC in an rseC mutant strain had no significant effect on rpoE mRNA and protein (Figure 7). Thus, we hypothesized a pathway in which AsrC overexpression increased rpoE expression primarily through increasing expression of rseC and enhanced σE regulatory pathways. Moreover, it is known that at the transcriptional level, the rpoE gene is positively autoregulated, because one of its own promoters is transcribed by the EσE holoenzyme itself (Raina et al., 1995; Rouvière et al., 1995). Therefore, by increasing the expression of RseC that positively controls RpoE activity, AsrC could induces the expression of the rpoE-rseABC operon. Taken together, AsrC promoted the expression of genes related to motility and enhancing the motility of S. typhi (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8. AsrC and its regulatory circuits. AsrC expression increases rseC mRNA and protein levels. RseC positively modulates transcriptional activity of rpoE and increases RpoE (σE) protein. The rpoE gene is positively autoregulated. Enhanced σE regulatory pathways respond by inducing transcription of genes related to motility. Arrows, activation.

In summary, the full-length AsrC was identified to be 893 nt, located 119 nt downstream of the lepA start codon and 36 nt upstream of rseC start codon. Expression of this antisense RNA increased the levels of rseC mRNA and protein and positively regulating RpoE. These processes might be important in motility of S. typhi.

Author Contributions

Conceived and designed the experiments: QZ, YZ, XZ; Performed the experiments: QZ, YZ, XZ, LZ; Analyzed the data: QZ, YZ, XH, SX, XS; Contributed reagents/materials/analysis tools: SX, XZ; Wrote the paper: YZ, XZ, XH, XS.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Takayuki Ezaki (Gifu University) for providing bacterial strains and suicide plasmid pGMB151, the National Natural Science Foundation of China (81371780). We wish to thank International Science Editing, Compuscript Ltd., Shannon Industrial Estate West Shannon, Co., Clare, Republic of Ireland, for native English checking.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: http://journal.frontiersin.org/article/10.3389/fmicb.2015.00990

References

Argaman, L., Hershberg, R., Vogel, J., Bejerano, G., Wagner, E. G., Margalit, H., et al. (2001). Novel small RNA-encoding genes in the intergenic regions of Escherichia coli. Curr. Biol. 11, 941–950. doi: 10.1016/S0960-9822(01)00270-6

Beck, B. J., Connolly, L. E., De Las Penas, A., and Downs, D. M. (1997). Evidence that rseC, a gene in the rpoE cluster, has a role in thiamine synthesis in Salmonella typhimurium. J. Bacteriol. 179, 6504–6508.

Chilcott, G. S., and Hughes, K. T. (2000). Coupling of flagellar gene expression to flagellar assembly in Salmonella enterica serovar typhimurium and Escherichia coli. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 64, 694–708. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.64.4.694-708.2000

Chinni, S. V., Raabe, C. A., Zakaria, R., Randau, G., Hoe, C. H., Zemann, A., et al. (2010). Experimental identification and characterization of 97 novel npcRNA candidates in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Nucleic Acids Res. 38, 5893–5908. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkq281

Dadzie, I., Ni, B., Gong, M., Ying, Z., Zhang, H., Sheng, X., et al. (2014). Identification and characterization of a cis antisense RNA of the parC gene encoding DNA topoisomerase IV of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. Res. Microbiol. 165, 439–446. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2014.05.032

Dadzie, I., Xu, S., Ni, B., Zhang, X., Zhang, H., Sheng, X., et al. (2013). Identification and characterization of a cis-encoded antisense RNA associated with the replication process of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. PLoS ONE 8:e61308. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0061308

Dartigalongue, C., Missiakas, D., and Raina, S. (2001). Characterization of the Escherichia coli sigma E regulon. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 20866–20875. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M100464200

Datsenko, K. A., and Wanner, B. L. (2000). One-step inactivation of chromosomal genes in Escherichia coli K-12 using PCR products. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 97, 6640–6645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.120163297

De Las Penas, A., Connolly, L., and Gross, C. A. (1997). The sigmaE-mediated response to extracytoplasmic stress in Escherichia coli is transduced by RseA and RseB, two negative regulators of sigmaE. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 373–385. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3611718.x

Du, H., Sheng, X., Zhang, H., Zou, X., Ni, B., Xu, S., et al. (2011). RpoE may promote flagellar gene expression in Salmonella enterica serovar typhi under hyperosmotic stress. Curr. Microbiol. 62, 492–500. doi: 10.1007/s00284-010-9734-y

Georg, J., and Hess, W. R. (2011). cis-antisense RNA, another level of gene regulation in bacteria. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 75, 286–300. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.00032-10

Huang, X., Phung, Le, V., Dejsirilert, S., Tishyadhigama, P., Li, Y., et al. (2004). Cloning and characterization of the gene encoding the z66 antigen of Salmonella enterica serovar Typhi. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 234, 239–246. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.2004.tb09539.x

Ikebe, T., Iyoda, S., and Kutsukake, K. (1999). Structure and expression of the fliA operon of Salmonella typhimurium. Microbiology 145(Pt 6), 1389–1396. doi: 10.1099/13500872-145-6-1389

Kohbata, S., Yokoyama, H., and Yabuuchi, E. (1986). Cytopathogenic effect of Salmonella typhi GIFU 10007 on M cells of murine ileal Peyer’s patches in ligated ileal loops: an ultrastructural study. Microbiol. Immunol. 30, 1225–1237. doi: 10.1111/j.1348-0421.1986.tb03055.x

Koo, M. S., Lee, J. H., Rah, S. Y., Yeo, W. S., Lee, J. W., Lee, K. L., et al. (2003). A reducing system of the superoxide sensor SoxR in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 22, 2614–2622. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdg252

Livak, K. J., and Schmittgen, T. D. (2001). Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 25, 402–408. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262

Mecsas, J., Rouviere, P. E., Erickson, J. W., Donohue, T. J., and Gross, C. A. (1993). The activity of sigma E, an Escherichia coli heat-inducible sigma-factor, is modulated by expression of outer membrane proteins. Genes Dev. 7, 2618–2628. doi: 10.1101/gad.7.12b.2618

Missiakas, D., Mayer, M. P., Lemaire, M., Georgopoulos, C., and Raina, S. (1997). Modulation of the Escherichia coli sigmaE (RpoE) heat-shock transcription-factor activity by the RseA. RseB and RseC proteins. Mol. Microbiol. 24, 355–371. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.1997.3601713.x

Missiakas, D., and Raina, S. (1997). Protein misfolding in the cell envelope of Escherichia coli: new signaling pathways. Trends Biochem. Sci. 22, 59–63. doi: 10.1016/S0968-0004(96)10072-4

Miticka, H., Rowley, G., Rezuchova, B., Homerova, D., Humphreys, S., Farn, J., et al. (2003). Transcriptional analysis of the rpoE gene encoding extracytoplasmic stress response sigma factor sigmaE in Salmonella enterica serovar Typhimurium. FEMS Microbiol. Lett. 226, 307–314. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1097(03)00600-1

Novick, R. P., Ross, H. F., Projan, S. J., Kornblum, J., Kreiswirth, B., and Moghazeh, S. (1993). Synthesis of staphylococcal virulence factors is controlled by a regulatory RNA molecule. EMBO J. 12, 3967–3975.

Ohnishi, K., Kutsukake, K., Suzuki, H., and Iino, T. (1990). Gene fliA encodes an alternative sigma factor specific for flagellar operons in Salmonella typhimurium. Mol. Gen. Genet. 221, 139–147. doi: 10.1007/BF00261713

Papenfort, K., and Vogel, J. (2010). Regulatory RNA in bacterial pathogens. Cell Host Microbe 8, 116–127. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2010.06.008

Pichon, C., and Felden, B. (2005). Small RNA genes expressed from Staphylococcus aureus genomic and pathogenicity islands with specific expression among pathogenic strains. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 102, 14249–14254. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0503838102

Raina, S., Missiakas, D., and Georgopoulos, C. (1995). The rpoE gene encoding the sigma E (sigma 24) heat shock sigma factor of Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 14, 1043–1055.

Rolhion, N., Carvalho, F. A., and Darfeuille-Michaud, A. (2007). OmpC and the sigma(E) regulatory pathway are involved in adhesion and invasion of the Crohn’s disease-associated Escherichia coli strain LF82. Mol. Microbiol. 63, 1684–1700. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2007.05638.x

Romby, P., Vandenesch, F., and Wagner, E. G. (2006). The role of RNAs in the regulation of virulence-gene expression. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 9, 229–236. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2006.02.005

Rouvière, P. E., De Las Peñas, A., Mecsas, J., Lu, C. Z., Rudd, K. E., and Gross, C. A. (1995). rpoE, the gene encoding the second heat-shock sigma factor, sigma E, in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 14, 1032–1042.

Skovran, E., Lauhon, C. T., and Downs, D. M. (2004). Lack of YggX results in chronic oxidative stress and uncovers subtle defects in Fe-S cluster metabolism in Salmonella enterica. J. Bacteriol. 186, 7626–7634. doi: 10.1128/JB.186.22.7626-7634.2004

Storz, G., Vogel, J., and Wassarman, K. M. (2011). Regulation by small RNAs in bacteria: expanding frontiers. Mol. Cell 43, 880–891. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2011.08.022

Testerman, T. L., Vazquez-Torres, A., Xu, Y., Jones-Carson, J., Libby, S. J., and Fang, F. C. (2002). The alternative sigma factor sigmaE controls antioxidant defences required for Salmonella virulence and stationary-phase survival. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 771–782. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2958.2002.02787.x

Thomason, M. K., and Storz, G. (2010). Bacterial antisense RNAs: how many are there, and what are they doing? Annu. Rev. Genet. 44, 167–188. doi: 10.1146/annurev-genet-102209-163523

Toledo-Arana, A., Repoila, F., and Cossart, P. (2007). Small noncoding RNAs controlling pathogenesis. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 182–188. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2007.03.004

Vogel, J., Bartels, V., Tang, T. H., Churakov, G., Slagter-Jager, J. G., Huttenhofer, A., et al. (2003). RNomics in Escherichia coli detects new sRNA species and indicates parallel transcriptional output in bacteria. Nucleic Acids Res. 31, 6435–6443. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkg867

Wassarman, K. M., Repoila, F., Rosenow, C., Storz, G., and Gottesman, S. (2001). Identification of novel small RNAs using comparative genomics and microarrays. Genes Dev. 15, 1637–1651. doi: 10.1101/gad.901001

Waters, L. S., and Storz, G. (2009). Regulatory RNAs in bacteria. Cell 136, 615–628. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.043

Keywords: Salmonella enterica serovar typhi, antisense RNA, AsrC, invasion, rseC, rpoE

Citation: Zhang Q, Zhang Y, Zhang X, Zhan L, Zhao X, Xu S, Sheng X and Huang X (2015) The novel cis-encoded antisense RNA AsrC positively regulates the expression of rpoE-rseABC operon and thus enhances the motility of Salmonella enterica serovar typhi. Front. Microbiol. 6:990. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.00990

Received: 29 June 2015; Accepted: 04 September 2015;

Published: 17 September 2015.

Edited by:

Yi-Cheng Sun, Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences and Peking Union Medical College, ChinaReviewed by:

Victor H. Bustamante, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, MexicoMonica Alejandra Delgado, Instituto Superior de Investigaciones Biologicas and Instituto de Quiimica Biologica “Dr. Bernabe Bloj”, Argentina

Copyright © 2015 Zhang, Zhang, Zhang, Zhan, Zhao, Xu, Sheng and Huang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) or licensor are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xinxiang Huang, Department of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, Jiangsu University – School of Medicine, Zhenjiang, Jiangsu 212013, China,aHV4aW54QHVqcy5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work.

Qi Zhang1,2†

Qi Zhang1,2† Ying Zhang

Ying Zhang Xiaolei Zhang

Xiaolei Zhang Xiumei Sheng

Xiumei Sheng Xinxiang Huang

Xinxiang Huang