- 1School of Nursing, China Medical University, Shenyang, Liaoning, China

- 2Affiliated Hospital of Qingdao University, Qingdao, Shandong, China

- 3Shenyang Orthopedics Hospital, Shenyang, Liaoning, China

Background: About 89% of global End-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients receive hemodialysis. Data show that about 40% ~ 60% of dialysis patients are young and middle-aged. Hemodialysis significantly impacts the daily life and rehabilitation of patients, underscoring the urgency of understanding their experiences and needs. However, findings from previous individual qualitative studies may lack representativeness.

Aims: This study used Meta-synthesis to offer a thorough understanding of the lived experiences, psychological states, and needs of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients.

Design: Systematic review and meta-synthesis.

Methods: A systematic search was conducted in PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science, CINAHL, CBM, CNKI, WanFang, and VIP databases from the establishment of each database to November 4, 2024, targeting qualitative studies on the experiences of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients (aged 18–65 years old). Quality assessment used the Joanna Briggs Institute’s 2016 Checklist for Qualitative Research, followed by meta-synthesis. The study’s reporting was informed by the principles of the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) framework. The thematic analysis approach was employed to synthesize the findings.

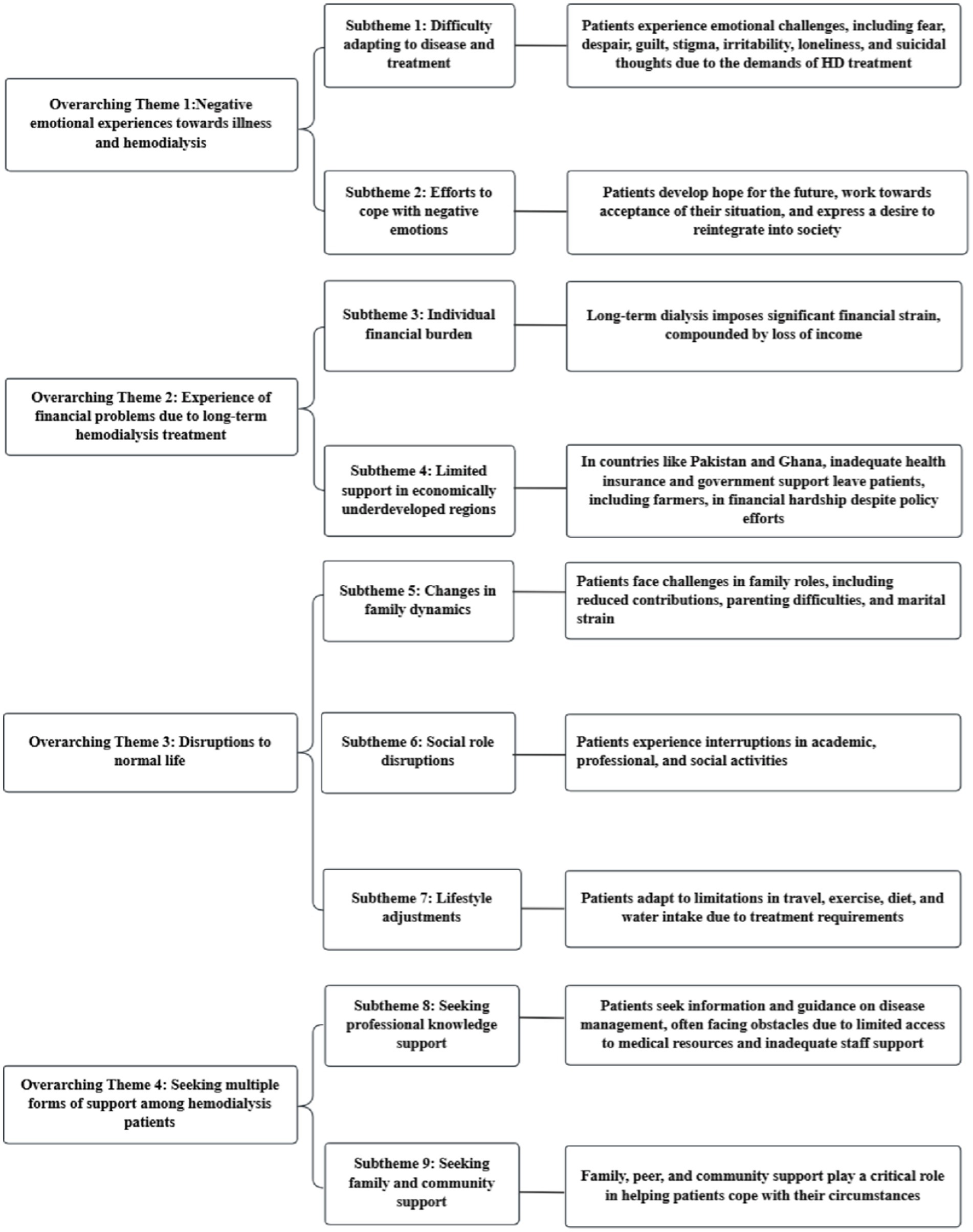

Results: Twenty-two studies were included, covering 14 countries. The inclusion of 22 studies yielded 83 findings, categorized into nine subthemes and condensed into four overarching themes: negative emotional experiences toward illness and hemodialysis, experience of financial problems due to long-term hemodialysis treatment, disruptions to normal life, and seeking multiple forms of support among hemodialysis patients.

Conclusion: Healthcare providers should attach importance to this group, to meet their specific needs, and support their active recovery. The goal is to help them relieve negative emotions, reduce financial burden, return to normal life and meet multiple forms of support.

1 Introduction

Hemodialysis (HD) is the renal replacement therapy in patients with acute and chronic renal failure, and is one of the most commonly used blood purification methods. It utilizes hemodialysis to remove metabolites and toxic substances from the human body and to correct water, electrolyte and acid–base balance disorders (1). Most hemodialysis patients undergo regular long-term dialysis sessions lasting 3.5–4.5 h, three times a week. Globally, approximately 89% of end-stage renal disease (ESRD) patients rely on hemodialysis (2). Data from 2013 indicated that 1 million people were receiving hemodialysis treatment worldwide, and the total number of people receiving dialysis was increasing by 10% per year (3). By 2023, China’s hemodialysis patient population had reached 910,000, and the number continues to increase significantly (4). About 40~60% of dialysis patients are young and middle-aged adults (5).

With advancements in hemodialysis technology, the survival rate of ESRD patients has markedly improved. However, prolonged treatment exerts comprehensive impacts on patients’ physical and mental health, social integration, daily functioning, and financial stability, significantly reducing quality of life (6, 7). While hemodialysis alleviates symptoms and prolongs survival, young and middle-aged patients face intensified challenges, including complications, economic strain, and treatment-related lifestyle constraints, which disproportionately burden those navigating pivotal life stages—pursuing education, advancing careers, and establishing families (8). Struggling to reconcile health demands with societal and familial obligations, they endure the dual pressures of maintaining survival and pursuing life aspirations (8). Understanding the impact of hemodialysis on young and middle-aged patients enables healthcare providers to deliver targeted nursing care and support.

Meta-synthesis is a method of systematic integration of qualitative research results, aiming to form a more comprehensive and in-depth understanding of a phenomenon by extracting common themes and deep meanings from different studies. Unlike the Meta-analysis of traditional quantitative research, Meta-synthesis focuses on the human experience, emotion, and socio-cultural context contained in qualitative data, and is particularly suitable for exploring complex health issues (such as psychological adaptation processes in patients with chronic diseases). There are many qualitative studies on the experience and needs of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients worldwide, but the sample size of a single study is small, and it is difficult to fully reflect the real situation of the target population by cultural background or sample characteristics. Meta-synthesis can integrate the results of different studies, reveal common rules, and provide more universal evidence for clinical practice. This study used Meta-synthesis to offer a thorough understanding of the lived experiences, psychological states, and needs of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients.

2 Methods

2.1 Research design

The Joanna Briggs Institute’s (JBI) PICo framework, an Australian evidence-based model (9), informed the development of our inclusion and exclusion criteria, using “P” for the study population; “I” for the research focus, the phenomenon of interest; and “Co” for the research context. The study’s reporting was informed by the principles of the Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) framework (10) (Supplementary material). The thematic analysis approach was employed to synthesize the findings (11).

2.2 Literature search strategy

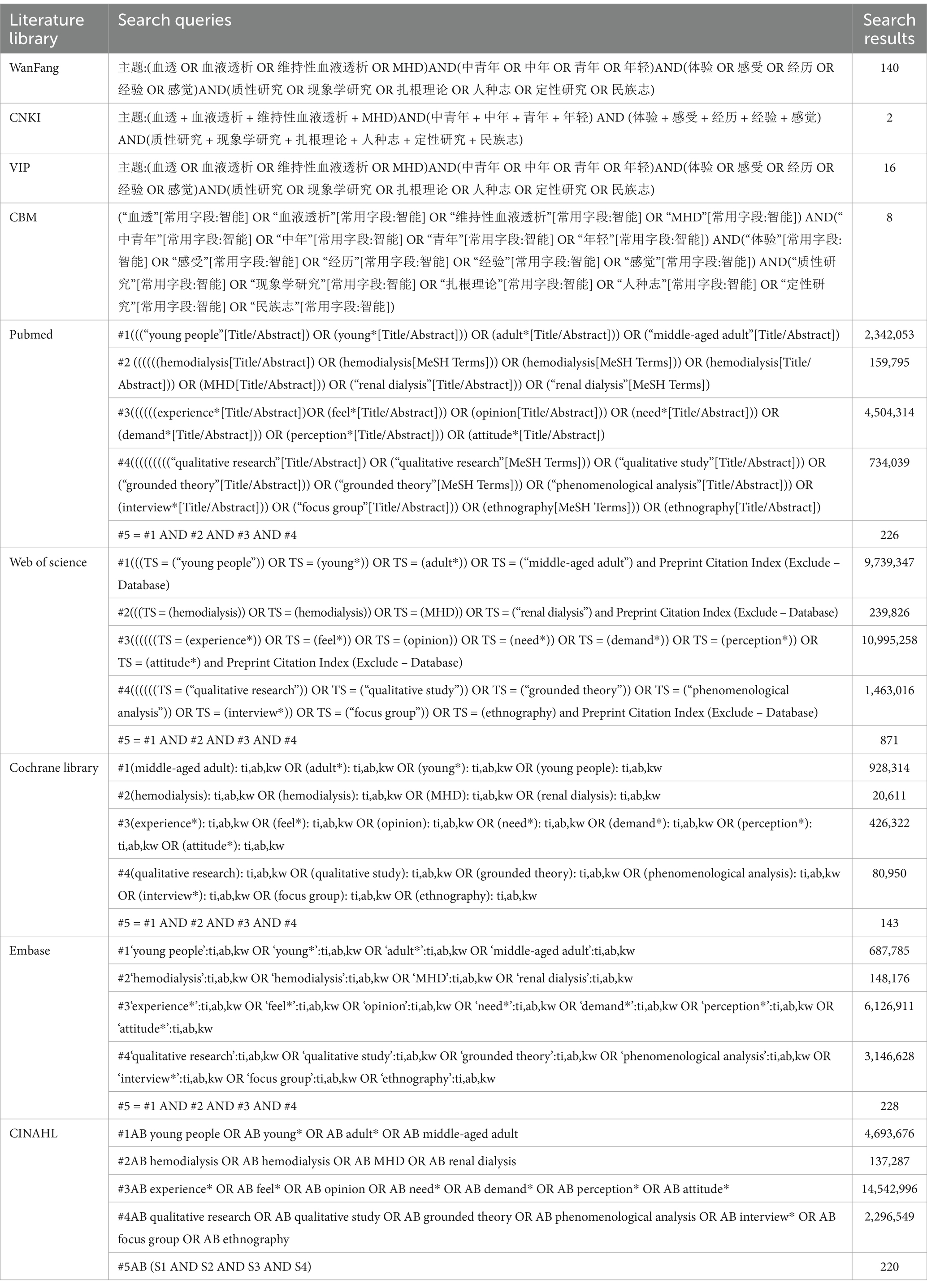

Zhang Kai and Teng Zeng searched PubMed, Embase, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science, CINAHL, CNKI, CBM, Wanfang, and VIP databases. The search integrated subject terms and free terms, customized for each database’s unique characteristics. Search terms included “hemodialysis,” “MHD,” “hemodialysis,” “renal dialysis,” “young people,” “young*,” “adult*,” “middle-aged adult,” “experience*,” “feel*,” “opinion,” “need*,” “demand*,” “perception*,” “attitude*,” “qualitative research,” “qualitative study,” “grounded theory,” “phenomenological analysis,” “interview*,” “focus group,” and “ethnography.” We conducted a manual search using the literature tracing method to comprehensively supplement the literature. Our search encompassed the period from the establishment of each database to November 4, 2024. The study is registered in Prospero: CRD42024577165. Table 1 illustrates the Search strategy.

2.3 Inclusion criteria

① Participants (P): Hemodialysis patients aged 18–65 were classified as young and middle-aged. ② Interest of Phenomena (I): Psychological states, needs, experiences, and emotions of hemodialysis patients aged 18–65. ③ Context (Co): Interviews with hemodialysis patients during hospital or home. ④ Study types (S): Qualitative studies using phenomenology, grounded theory, and ethnography, encompassing interviews and thematic analysis.

2.4 Exclusion criteria

① Exclude conference papers, policy documents, review articles, and case reports. ② Exclude articles that are published more than once or lack accessible full texts. ③ Exclude studies with a methodological quality rating of C. ④ Exclude literature that is not written in Chinese or English.

2.5 Literature quality assessment

Two researchers independently evaluated the included studies based on the 2016 Joanna Briggs Institute’s quality assessment criteria for qualitative research (12). They rated 10 criteria, responding “yes,” “no,” or “unclear” for each. When all 10 items are answered “yes,” the likelihood of bias is minimal and rated as A. If some of the quality criteria are met but not all, the possibility of bias is considered moderate, designated as B. If all items are answered “no,” the possibility of bias is deemed high and classified as C. Discrepancies in evaluations were resolved through discussion; a third party arbitrated if consensus was not reached. Studies graded A and B were included in the final analysis.

2.6 Data screening and extraction

Two researchers, both postgraduate students who have completed a course in evidence-based nursing and are familiar with qualitative methods, independently screened the literature, extracted data, and cross-verified their findings. A third researcher (NCP) mediated evaluations in cases of disagreement. The screening process included importing documents into NoteExpress for de-duplicating, removing, reviewing titles and abstracts based on established criteria, and conducting a full-text review for secondary screening. Data extraction focused on author, country, methodology, study object, the phenomenon of interest, contextual factors, and key findings.

2.7 Meta synthesis

The information from the included studies were integrated utilizing the three-stage thematic analysis framework proposed by Thomas and Harden (11). This process encompassed three distinct phases. Initially, a dual-review methodology was applied by ZK and NCP, who meticulously scrutinized the primary literature, engaging in repeat readings to assign codes based on the semantic and contextual nuances of the text. Proceeding to the second phase, ZK and NCP conducted a comparative analysis of the emergent codes, identifying commonalities and disparities, which facilitated the formation of descriptive themes. In the third phase, the reviewers ZK and NCP conducted a thorough review of these descriptive themes, discerning novel insights, interpretations, or presuppositions that enriched the thematic landscape.

3 Results

3.1 Literature screening process and results

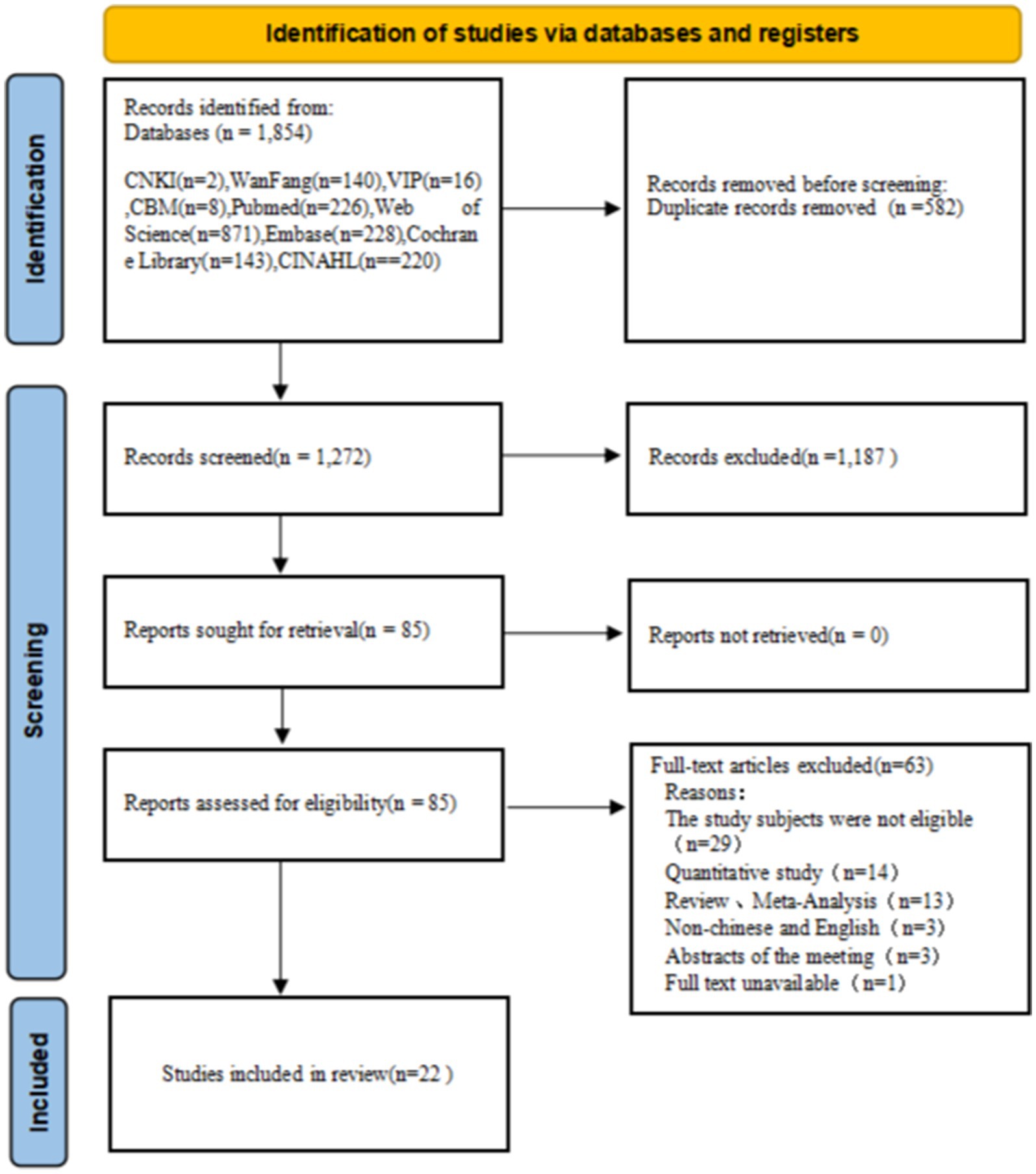

Initially, our search strategy identified 1,854 relevant articles, which was reduced to 1,272 after the removal of duplicates. Following the review of titles and abstracts, the articles were narrowed down to 85 according to the selection. The full-text review led to the exclusion of an additional 63 articles. A total of 22 articles were included after quality evaluation. The process of literature screening is depicted in Figure 1.

3.2 Characteristics results of the included literature

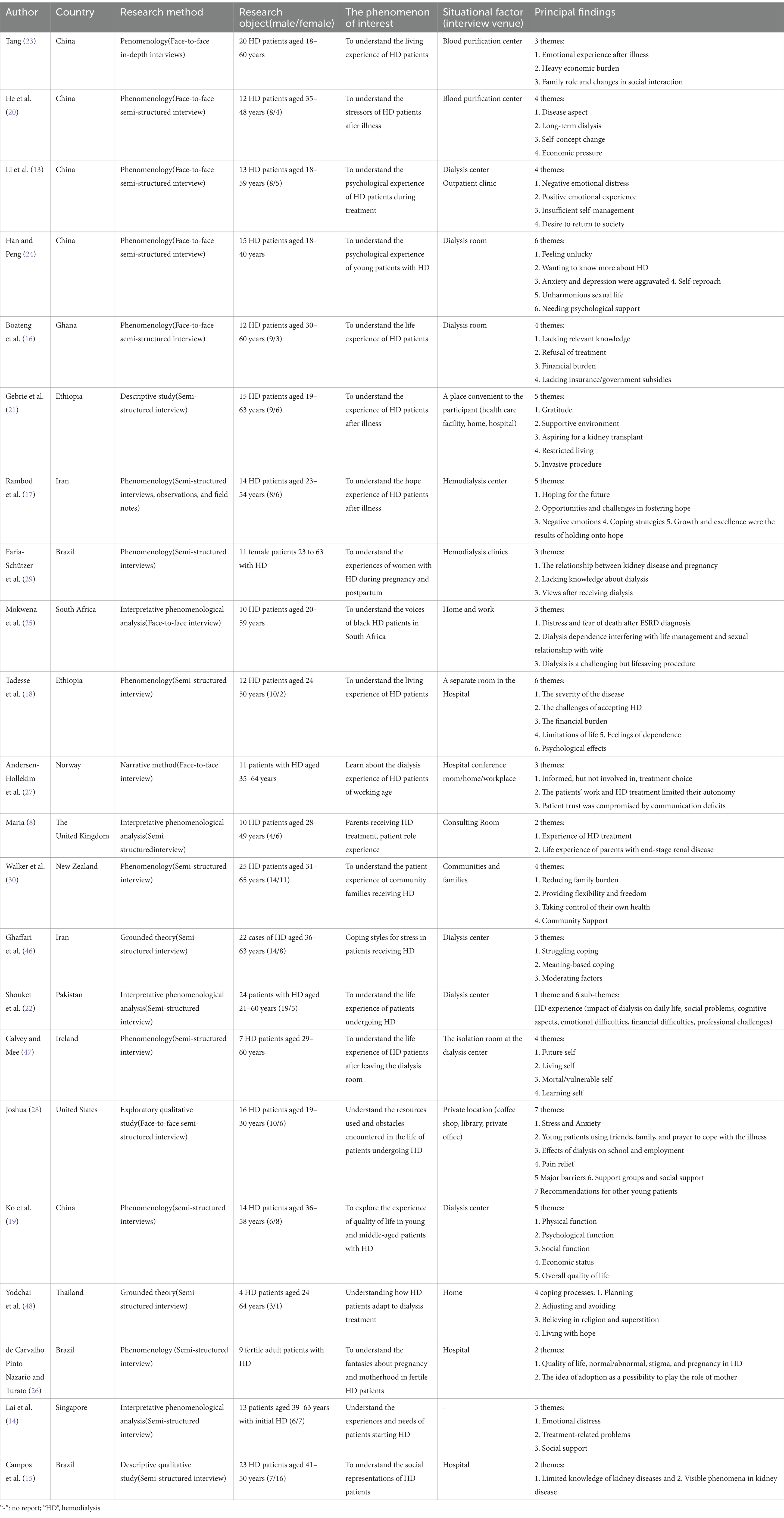

The research methods include: 16 phenomenological studies, 2 grounded theory studies, 2 descriptive qualitative studies, 1 exploratory qualitative study and 1 narrative qualitative study. Age range from 18 to 65 years old. The study involving the authentic experience of hemodialysis in young and middle-aged adults in 14 countries. Studies were conducted in the United States (n = 1), China (n = 5), Ghana (n = 1), Ethiopia (n = 2), Iran (n = 2), South Africa (n = 1), Norway (n = 1), The United Kingdom (n = 1), New Zealand (n = 1), Pakistan (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), Thailand (n = 1), Brazil (n = 3), Singapore (n = 1). More than 50% of the articles in this paper were published less than 5 years ago, and only 2 articles were published more than 15 years ago. The basic characteristics of the included literatures are shown in Table 2.

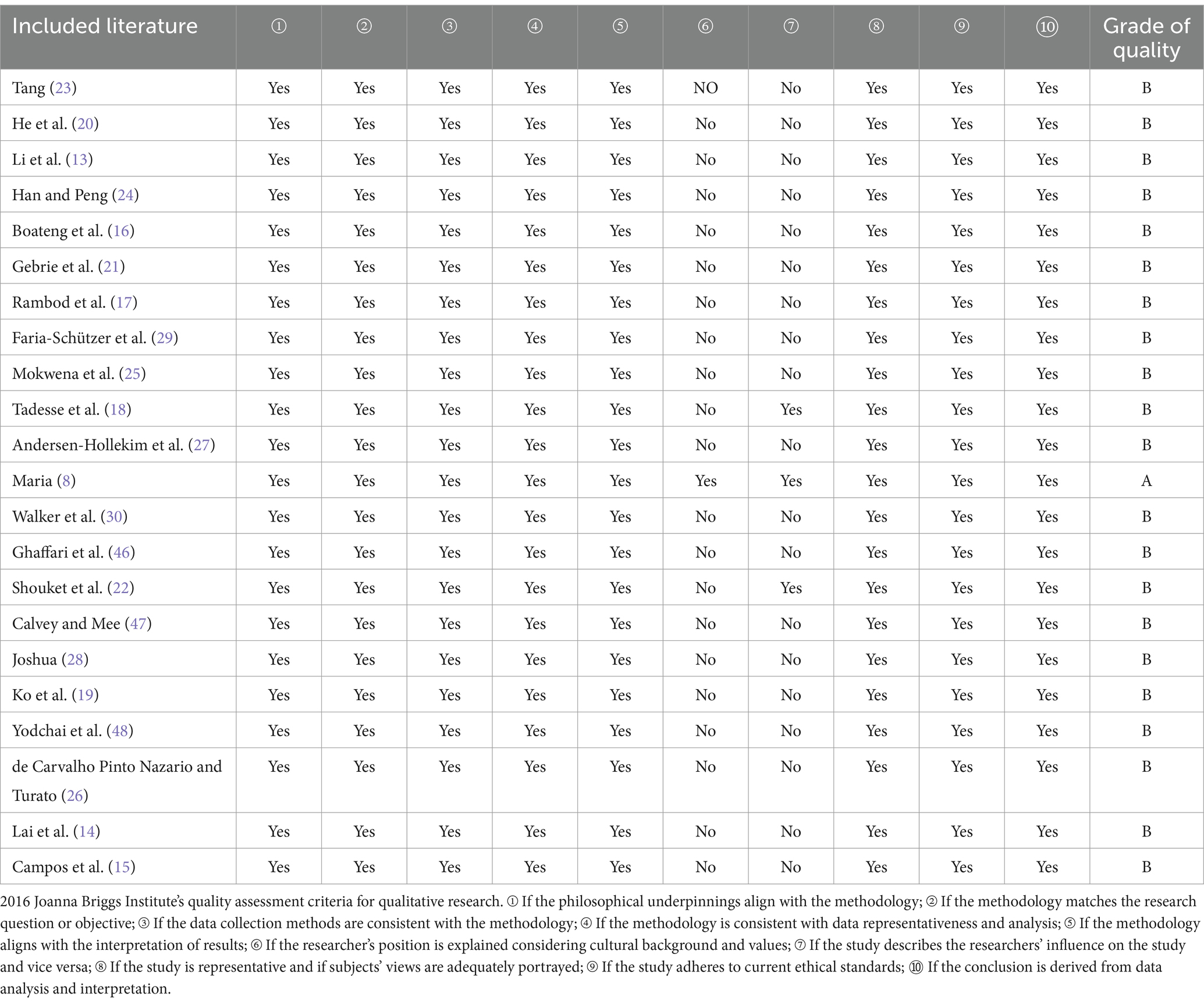

3.3 Quality appraisal

Twenty-one studies were rated as “B” and 1 was rated as “A,” and thus none was deleted after quality appraisal. Twenty-one studies rated “no” on item 6 “introducing researchers from a cultural or theoretical background.” 19 studies were rated “no” in item 7 “study describes the researchers’ influence on the study and vice versa.” On the other items, all 22 studies were rated as “yes.” The results of literature quality evaluation is shown in Table 3.

3.4 Meta-synthesis results

We extracted 83 themes from 22 studies, grouped similar findings into 9 subthemes, and synthesized these into 4 overarching themes. The results of integration are shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Overarching themes of included literatures. The content in the far right box is an explanation of the subtheme.

3.4.1 Overarching theme 1: negative emotional experiences toward illness and hemodialysis

Subtheme 1: Adjusting to illness and treatment posed challenges for young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients. In included qualitative studies, patients frequently indicated significant psychological distress and negative emotions linked to their physical challenges. Many patients also expressed despair about the future for themselves and their families, driven by concerns over the long-term impact of their illness, unpredictable disease progression, and variable prognosis. “After falling ill and undergoing continuous dialysis, my spouse felt the financial pressure at home was too great, and we divorced within 2 years. Alas, such was life (with tears in my eyes) (Male, 44, Primary school, Unemployed); While undergoing dialysis here, I occasionally contemplated the possibility of worse outcomes, fearing that the dialysis might not effectively remove toxins, which could then lead to infections affecting other organs (Female, 44, High school, Working)” (13). Patients indicated that fistulas and needle sites might lead to body image concerns and stigma. “Looking at their (established patients’) scars, I felt so scared (Female, 52)” (14). “Constant stares caused embarrassment and tears” (15). Some young patients denied kidney issues and dialysis need, resulting in treatment refusal; one patient stated: “I was reluctant to seek hospital treatment, as I could not believe there was a problem with my kidneys (Male, Unemployed) “(16). Patients indicated they felt aggressive over minor stressors and developed an aversion to dialysis machinery due to prolonged treatment; one patient said: “I detested the dialysis machinery, and thinking of dialysis caused depression (Male, Elementary, Unemployed) “(17). Additionally, patients experienced intense loneliness and boredom from living with the condition. A female patient expressed that: “I was deciding to kill myself, to be free from hemodialysis. I feel lonely. It is boring to live with such a condition. [She cried] (Cannot read and write, Merchant)” (18).

Subtheme 2: Young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients attempt to cope with negative emotions. Despite life dissatisfaction, some patients accepted their situation, comparing it favorably to graver illnesses. “Hemodialysis was better than facing death without it. Now, patients could stay with their families, avoiding direct succumbing to kidney disease (Female, 36)” (19). Eager for societal reintegration, a patient said: “Removing toxins through dialysis was good, but I hoped to find work; I was still young (Women, Middle school, Unemployed) “(13). “Post-dialysis, I aspired to a kidney transplant and a healthy, fulfilling life without illness or complications (Female, High school, Housewife)” (17). “Despite immense suffering from hemodialysis and kidney disease, the struggle fortified my resolve, allowing hopeful confrontation of reality (Male, Middle school, Unemployed)” (13).

3.4.2 Overarching theme 2: experience of financial problems due to long-term hemodialysis treatment

Subtheme 3: Individual financial burden. As primary breadwinners, young and middle-aged patients undergoing long-term dialysis often face unemployment and hardship, struggling to cover basic needs. “Since my illness, I relied on my husband’s earnings. Limited by our rural income, our once school-attending children now worked to contribute financially” (20). “Thrice-weekly hemodialysis sessions, with their time constraints and health impacts, prevented me from securing steady employment or income (Female, 46, Unemployed)”; “Dialysis-induced weakness inhibited my ability to work, cutting off my income” (19). As a result, patients indicated that, desperate to afford the costly treatments, numerous patients were forced to sell their assets and seek financial assistance from family members and others (21).

Subtheme 4: Underdeveloped Areas’ Healthcare Policy Challenges. In a Pakistan study, patients indicated that financial constraints limited the access of low-income patients to hemodialysis, due to few available beds in government hospitals and high costs at private centers (22). Patients could not afford essential dialysis treatments due to facility scarcity (22). Similarly, In a Ghana study, patients indicated that the lack of government and insurance coverage for hemodialysis burdened them with the full treatment costs (16). “Migrant ‘hukou’ patients reported that despite policy relief for farmers, medical costs, including consultations, tests, and hospitalization, remain burdensome” (23).

3.4.3 Overarching theme 3: breaking the normal life

Subtheme 5: Shifts in Family Dynamics. Disease and regular dialysis treatments were perceived by patients to decrease work capacity and strength, which in turn, was perceived to deteriorate their role as family pillars. Individuals undergoing hemodialysis indicated significant challenges in fulfilling their role responsibilities and managing family pressures (23). The rigid hemodialysis schedule and associated side effects were particularly disruptive to their parental roles, often impeding their ability to provide childcare and meet parental expectations. As a parent lamented: “Three four-hour weekly hospital visits broke my heart; I was absent for my child (Female, 41)”; Additionally, the authority in the family dynamic shifts, as one father explained, “My word used to be law, but now it is not.” (Male, 44) (8). Furthermore, patients described how illness prompted relinquishment of responsibilities, including transferring family finances to their wives and ceasing their sons’ recreational activities, while fatigue, a notable side effect, further impeded their parenting abilities (8). For instance, one parent recounted, “Post-dialysis exhaustion sometimes stopped me from listening to my child (Female, 43); fistula site pain weakened my arm, needing help to lift my son (Male, 28)” (8).

Patients indicated that discord in sexual life discord and challenges with pregnancy due to end-stage kidney disease impacted family life. They conveyed emotional struggles: “Dialysis during the day and my partner’s night work resulted in rare encounters and concern for our sparse sexual life” (24); “Lack of sexual desire for weeks might lead to affairs and family breakdowns” (25). Moreover, individuals undergoing hemodialysis indicated that menstrual and ovulation irregularities, reduced sexual function, and fertility challenges made pregnancy and motherhood seem unattainable for women on hemodialysis; the arteriovenous fistula’s physical mark and societal stigmatization further compounded these challenges, given the perception that only healthy women were suitable for motherhood (26). Additionally, they indicated that post-transplant pregnancies were short-lived due to kidney rejection and renal failure after childbirth, which necessitated the resumption of hemodialysis (8).

Subtheme 6: Changes in social roles. Qualitative findings revealed that altered body image was a significant factor contributing to social withdrawal among individuals undergoing hemodialysis. One female patient described her experience, saying: “Embarrassed and fearing questions, I avoided communication” (19). Moreover, patients indicated that inflexible dialysis schedule and limited energy forced them to narrow their social lives (23). For example, a patient stated: “A session consumed half my day, centering my life around dialysis” (20). In addition, individuals undergoing hemodialysis indicated that complications from dialysis significantly altered their social roles. As one male patient mentioned: “Fatigue reduced my ability to perform daily tasks, affecting social interactions and life quality (Secondary school, Merchant) “(18). Furthermore, symptoms like itching and restless legs syndrome discouraged my participation in social activities (27). Finally, “School attendance was challenging due to eight-hour weekly therapy sessions, causing frequent absences. Visible treatment effects, like an enlarged arm, and post-dialysis discomfort, sometimes also deterred me from attending” (28).

Subtheme 7: Behavior changes in daily life. Patients indicated that travel plans had to fit hemodialysis constraints, reducing destination options: “I used to avidly travel and enjoy sports, but my kidney condition put an end to those activities (Male, 63)” (19). Furthermore, dietary and drinking water restrictions imposed by dialysis often led to changes in social behaviors and daily routines, as described by patients: “Thirsty but unable to drink, disheartening (Male, 46)” (14). “Dietary restrictions from dialysis often lead me to avoid food at family gatherings (Male, 55)” (22).

3.4.4 Overarching theme 4: patients are seeking multiple forms of support

Subtheme 8: Seeking professional knowledge support. Patients frequently sought explanations for their conditions and desired deeper knowledge of hemodialysis. For example, one patient said, “I used to use my spare time to consult the internet about nephropathy, internal fistulas, and dialysis” (24). However, patients often lacked awareness of kidney disease issues, especially those linked to hypertension or pregnancy. As a male patient mentioned, “I used to smoke, drink, and stay up late, ignoring warnings about kidney damage (College, Working)” (13). And patients indicated that they could identify recognized conditions such as hypertension or diabetes, but that kidney disease, which is often overlooked, was a complication (16). As a female patient shared, “My mother noticed my swelling, and despite our rural setting, she treated me with various medications. It wasn’t until I was 18 that I discovered my kidneys were impaired. Later, during pregnancy, I faced further issues, initially consulting a therapist. It was only on the day of my child’s birth that my condition deteriorated, prompting a visit to a doctor” (29).

Subtheme 9: Seeking family and social support. Patients indicated that they derived strength in life from their children and spouse. For example, one female patient said, “Her five children were her reason for living” (29) and another mentioned, “My family, including my husband, had been a pillar of support” (21). Additionally, with the help and support of friends and peers, patients gained relevant knowledge and improved their self-management skills. As a female patient noted, “Friends in the hemodialysis room provided significant support” (29), while a male patient shared, “Conversations with fellow patients offered valuable insights and treatment advice” (30). Furthermore, Community and support groups provided comfort and helped patients cope with challenges. A female patient expressed, “A community home turned me from fearful to optimistic” (30), and another patient said, “I encouraged other patients to join our support group, where they could receive valuable information and personalized assistance with their challenges” (8).

4 Discussion

The aim of this study is to explore the experiences, psychological states and needs of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients (aged 18–65 years) through a meta-synthesis of qualitative studies. Our findings suggest that patients face negative emotional experiences toward illness and hemodialysis, experience of financial problems due to long-term hemodialysis treatment, disruptions to normal life, and struggle to seek multiple forms of support. Compared with the existing literature, this study is the first to systematically summarize the experiences and needs of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients, offering insights for better patient-centered care and disease management in clinical practice. Based on these findings, we propose the following recommendations.

4.1 Pay attention to the inner world of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients and guide positive psychological experience

Young and middle-aged individuals, who shoulder the highest work responsibilities and family/societal obligations, endure substantial physical and psychological trauma from kidney disease and hemodialysis. This leads to physiological decline, increased complications, symptom burden, and social dysfunction. Patients often experience a variety of negative emotions, including self-blame, regret, fear, anxiety, pain, irritability, disgust, loneliness, depression, despair, and suicidal thoughts. Some may even refuse treatment. However, they also attempt to cope with negative emotions. For customized nursing interventions, medical staff should maintain consistent communication, promptly assess the psychological states of patients and identify early signs of negative emotions. For patients who already have severe emotional distress, it is essential to facilitate the expression of feelings, offer effective psychological counseling, support self-adjustment, and encourage a positive outlook. Psychological interventions, such as humor therapy (31), mindfulness-based stress reduction (32), and cognitive-behavioral therapy (33) help individuals to change maladaptive cognitions and behaviors, alleviate negative emotions, and develop coping mechanisms. More deeply, the results of this study showed that most patients had negative emotions due to symptom burden, decreased physical function, and disease management strategies, such as multidisciplinary nursing care, which promotes collaboration among healthcare professionals, ensuring optimal treatment, maximal symptom relief, and the reduction of negative emotions (34).

4.2 Ease the economic burden

The study showed that hemodialysis patients face significant financial strain from treatment costs, symptom management, unemployment, and healthcare policies. To alleviate their burden, the following actions are recommended. While systemic reforms require governmental action, medical staff could implement immediate interventions to mitigate economic burdens. Clinicians could proactively identify patients’ financial distress and establish confidential counseling channels for those opting to disclose economic concerns. This could help in identifying potential financial resources and family support systems available to patients for long-term hemodialysis. Tailoring dialysis regimens to individual clinical profiles and residual renal function may yield both medical and socioeconomic benefits. Incremental hemodialysis, offering sessions of 3–4 h ≤2 times per week or <3 h ≥3 times, adapts to personal situations and allows flexible treatments adjustments, which can slow the renal function decline, reduce dialysis frequency, lower medical costs and ease patients’ financial strain (35, 36). Introducing nocturnal dialysis services and implementing flexible scheduling options, such as home hemodialysis, support patients’ employment needs and increase their income. Through the implementation of these clinically grounded, patient-oriented strategies, to alleviate the economic burdens inherent in mostly long-term hemodialysis management.

4.3 Assist the patient to gradually return to normal life

The prolonged hemodialysis process, with its specialized treatment and symptom burden, disrupts patients’ lives. Hemodialysis patients often experience reduced family function due to dialysis complications and disease treatment needs. Healthcare providers should take a family-centered approach, wherein interventions engage both patients and their family members as collaborative partners in treatment. This approach involves structured family education programs detailing renal pathophysiology, dialysis frequency protocols, evidence-based dietary modifications, and pharmacological management, etc. (37). By strengthening familial health literacy and caregiving capacity, such interventions may reduce treatment-related complications while enhancing psychosocial support systems to facilitate successful household reintegration (37). Medical staff could communicate more with patients and guide them through interventions such as hand-foot massage (38), aerobic exercise (39), and self-acupressure (40) to alleviate symptom cluster, enhance their quality of life, and facilitate return to normal life. For patients pursuing vocational or educational reintegration, care teams should develop tailored transition plans featuring flexible dialysis scheduling coordinated with occupational rehabilitation specialists. This multidimensional care framework aims to optimize both clinical outcomes and psychosocial adaptation throughout the disease trajectory. Hemodialysis patients require dietary restriction due to their severely impaired kidney function, which prevents them from properly excreting metabolic waste and regulating electrolyte and water balance (41, 42). However, the results of this study indicate that dietary restrictions in young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients often lead to decreased appetite, loss of social function, and reduced quality of life. Healthcare teams should collaborate with patients to co-develop individualized dietary plans, integrating clinical parameters and psychosocial needs. This evidence-based approach aims to reduce unnecessary dietary constraints while supporting social reintegration through nutrition autonomy.

4.4 Providing hemodialysis patients with essential knowledge, peer and community support

The results of this study show that many patients are uninformed about their disease’s origins and self-management, highlighting the need for better health education. To empower patients, medical staff could develop a series of educational materials, including brochures, posters, videos, and science communication via digital platforms. These resources would disseminate knowledge on kidney disease self-management and dialysis, ultimately improving patients’ health literacy and self-care capabilities (43, 44). The results of this study suggest that hemodialysis patients often need to seek peer and social support to help them better face the disease and the challenges of dialysis treatment. Therefore, medical staff could help patients to establish peer support network to achieve the purpose of returning to society and promoting patients’ trust (45). The community could organize recreational activities for dialysis patients to participate in (such as painting, calligraphy classes, and light exercise classes) to enhance their sense of social integration.

5 Conclusion

This study conducted a meta-synthesis of 22 qualitative studies to comprehensively analyze and interpret the actual experiences, psychological states, and needs of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients. The findings showed that young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients face negative emotional experiences toward illness and hemodialysis, experience of financial problems due to long-term hemodialysis treatment, disruptions to normal life and seeking multiple forms of support. Noting the rising number of young hemodialysis patients, the study emphasizes their psychological journey and specific needs. Healthcare providers should attach importance to this group, to meet their specific needs, and support their active recovery. The goal is to help them relieve negative emotions, reduce financial burden, return to normal life and meet support-seeking behaviors.

6 Limitations

(1) Most literature quality evaluations rated grade B, with one grade A study, indicating a moderate overall quality. (2) The literature search included only Chinese and English sources, excluding those in other languages. (3) The study covered 14 countries with varying economic levels and nursing environments, reflecting a broad heterogeneity, the findings of this review may not be universally applicable to medical staff across all countries.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

KZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. ZT: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. AL: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. NZ: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. RW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. SW: Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. CN: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by Teaching Research Project of School of Nursing, China Medical University (2023HL-02).

Acknowledgments

The authors thanks the teachers of Nursing School of China Medical University.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The authors declare that no Gen AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2025.1530465/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Working Group for the Choice of Blood Purification Modality, the Innovation Aliance of Blood Purification for Kidney Disease in Zhong Guan Cun Division of Blood Purification Center, Chinese Hospital Association. Expert consensus on blood purification mode selection. Chin J Blood Purif. (2019) 18:442–72. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1671-4091.2019.07.002

2. Pecoits-Filho, R, Okpechi, IG, Donner, JA, Harris, DCH, Aljubori, HM, Bello, AK, et al. Capturing and monitoring global differences in untreated and treated end-stage kidney disease, kidney replacement therapy modality, and outcomes. Kidney Int Suppl. (2020) 10:e3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.kisu.2019.11.001

3. Eckardt, KU, Coresh, J, Devuyst, O, Johnson, RJ, Köttgen, A, Levey, AS, et al. Evolving importance of kidney disease: from subspecialty to global health burden. Lancet. (2013) 382:158–69. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60439-0

4. Chen, XM. Chinese mainland latest dialysis data. Chinese Society of Nephrologists, Chinese Medical Doctor Association (CNA). (2024). Available online at: https://www.sohu.com/a/798151047_121948383 (Accessed November 10, 2024).

5. Kimata, N, Tsuchiya, K, Akiba, T, and Nitta, K. Differences in the characteristics of Dialysis patients in Japan compared with those in other countries. Blood Purif. (2015) 40:275–9. doi: 10.1159/000441573

6. Wang, D, Wang, PC, Zhang, P, Weng, YM, Qian, Z, Qiao, T, et al. Illness experience of maintenance hemodialysis patients with end-stage renal disease. Chin Nurs Manag. (2023) 23:32–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1672-1756.2023.01.007

7. Shen, HX, Li, MY, Lai, MQ, Yan, SJ, van der Kleij, R, Chavannes, N, et al. Experience of patients with chronic kidney disease: a qualitative study. Milit Nurs. (2024) 41:74–7. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2097-1826.2024.08.017

8. Maria, T. The experience of being a parent receiving hospital-based haemodialysis treatment: a qualitative study. Dissertation/master's thesis. London: The City University (2019).

9. Joanna Briggs Institute. Joanna Briggs institute reviewers manual: 2011 cdition. SA, Joanna Briggs Institute: Adelaide (2011).

10. Tong, A, Flemming, K, McInnes, E, Oliver, S, and Craig, J. Enhancing transparency in reporting the synthesis of qualitative research: ENTREQ. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2012) 12:181. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-181

11. Thomas, J, and Harden, A. Methods for the thematic synthesis of qualitative research in systematic reviews. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2008) 8:45. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-8-45

12. Hu, Y, and Hao, YF. Evidence-based nursing. 2nd ed. Bei Jing: People's Medical Publishing House (2018).

13. Li, YP, Zhang, L, Meng, X, Hu, JK, Wang, GH, Qiu, MB, et al. Psychological experience of young and middle-aged uremia patients undergoing regular hemodialysis. Henan Med Res. (2022) 31:2909–12. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1004-437X.2022.16.008

14. Lai, AY, Loh, AP, Mooppil, N, Krishnan, DS, and Griva, K. Starting on haemodialysis: a qualitative study to explore the experience and needs of incident patients. Psychol Health Med. (2012) 17:674–84. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2012.658819

15. Campos, CG, Mantovani Mde, F, Nascimento, ME, and Cassi, CC. Social representations of illness among people with chronic kidney disease. Rev Gaucha Enferm. (2015) 36:106–12. doi: 10.1590/1983-1447.2015.02.48183

16. Boateng, EA, Iddrisu, AA, Kyei-Dompim, J, and Amooba, PA. A qualitative study on the lived experiences of individuals with end-stage kidney disease (ESKD) accessing haemodialysis in northern Ghana. BMC Nephrol. (2024) 25:186. doi: 10.1186/s12882-024-03622-x

17. Rambod, M, Pasyar, N, and Parviniannasab, AM. A qualitative study on hope in iranian end stage renal disease patients undergoing hemodialysis. BMC Nephrol. (2023) 24:281. doi: 10.1186/s12882-023-03336-6

18. Tadesse, H, Gutema, H, Wasihun, Y, Dagne, S, Menber, Y, Petrucka, P, et al. Lived experiences of patients with chronic kidney disease receiving hemodialysis in Felege Hiwot comprehensive specialized hospital, Northwest Ethiopia. Int J Nephrol. (2021) 2021:6637272. doi: 10.1155/2021/6637272

19. Ko, FC, Lee, BO, and Shih, HT. Subjective quality of life in patients undergoing long-term maintenance hemodialysis treatment: a qualitative perspective. Hu Li Za Zhi. (2007) 54:53–61.

20. He, LF, Gan, X, Yang, YQ, and Liu, MQ. Qualitative research on pressure sources of young and middle-aged patients receiving maintenance hemodialysis. J Bengbu Medi Coll. (2013) 38:1620–1622, 1630. doi: 10.13898/j.cnki.issn.1000-2200.2013.12.008

21. Gebrie, MH, Asfaw, HM, Bilchut, WH, Lindgren, H, and Wettergren, L. Patients' experience of undergoing maintenance hemodialysis. An interview study from Ethiopia. PLoS One. (2023) 18:e0284422. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0284422

22. Shouket, H, Gringart, E, Drake, D, and Steinwandel, U. "machine-dependent": the lived experiences of patients receiving hemodialysis in Pakistan. Glob Qual Nurs Res. (2022) 9:23333936221128240. doi: 10.1177/23333936221128240

23. Tang, WY. Related research on life experience of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients. Diet Health. (2018) 5:18. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.2095-8439.2018.33.020

24. Han, X, and Peng, L. Qualitative research on the real psychological experience of young hemodialysis patients. China Pract Med. (2013) 33:267–8. doi: 10.14163/j.cnki.11-5547/r.2013.33.034

25. Mokwena, J, Sodi, T, Makgahlela, M, and Nkoana, S. The voices of black South African men on renal Dialysis at a tertiary hospital: a phenomenological inquiry. Am J Mens Health. (2021) 15:15579883211040918. doi: 10.1177/15579883211040918

26. de Carvalho Pinto Nazario, R, and Turato, ER. Fantasies about pregnancy and motherhood reported by fertile adult women under hemodialysis in the Brazilian southeast: a clinical-qualitative study. Rev Lat Am Enfermagem. (2007) 15:55–61. doi: 10.1590/s0104-11692007000100009

27. Andersen-Hollekim, T, Solbjør, M, Kvangarsnes, M, Hole, T, and Landstad, BJ. Narratives of patient participation in haemodialysis. J Clin Nurs. (2020) 29:2293–305. doi: 10.1111/jocn.15238

28. Joshua, N. Social service needs of young adults undergoing hemodialysis treatment. Dissertation/master's thesis California State University (2011).

29. Faria-Schützer, DB, Borovac-Pinheiro, A, Rodrigues, L, and Surita, FG. Pregnancy and postpartum experiences of women undergoing hemodialysis: a qualitative study. J Bras Nefrol. (2023) 45:180–91. doi: 10.1590/2175-8239-JBN-2022-0001en

30. Walker, RC, Tipene-Leach, D, Graham, A, and Palmer, SC. Patients' experiences of community house hemodialysis: a qualitative study. Kidney Med. (2019) 1:338–46. doi: 10.1016/j.xkme.2019.07.010

31. Xie, C, Li, L, and Li, Y. Humor-based interventions for patients undergoing hemodialysis: a scoping review. Patient Educ Couns. (2023) 114:107837. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2023.107837

32. Akbulut, G, and Erci, B. The effect of conscious mindfulness-based informative approaches on managing symptoms in hemodialysis patients. Front Psychol. (2024) 15:1363769. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1363769

33. Sohn, BK, Oh, YK, Choi, JS, Song, J, Lim, A, Lee, JP, et al. Effectiveness of group cognitive behavioral therapy with mindfulness in end-stage renal disease hemodialysis patients. Kidney Res Clin Pract. (2018) 37:77–84. doi: 10.23876/j.krcp.2018.37.1.77

34. Yu, SB, Zeng, XQ, and Fu, P. Improvement of quality of life in a patient with diabetic nephropathy by integrated management. Chin J Nephrol. (2023) 39:291–3. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn441217-20220510-00518

35. Gedney, N, and Kalantar-Zadeh, K. Dialysis patient-centeredness and precision medicine: focus on incremental home hemodialysis and preserving residual kidney function. Semin Nephrol. (2018) 38:426–32. doi: 10.1016/j.semnephrol.2018.05.012

36. Vilar, E, Kaja Kamal, RM, Fotheringham, J, Busby, A, Berdeprado, J, Kislowska, E, et al. A multicenter feasibility randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of incremental versus conventional initiation of hemodialysis on residual kidney function. Kidney Int. (2022) 101:615–25. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2021.07.025

37. Zolfaghari, M, Asgari, P, Bahramnezhad, F, Ahmadi Rad, S, and Haghani, H. Comparison of two educational methods (family-centered and patient-centered) on hemodialysis: related complications. Iran J Nurs Midwifery Res. (2015) 20:87–92.

38. Çeçen, S, and Lafcı, D. The effect of hand and foot massage on fatigue in hemodialysis patients: a randomized controlled trial. Complement Ther Clin Pract. (2021) 43:101344. doi: 10.1016/j.ctcp.2021.101344

39. Hargrove, N, El Tobgy, N, Zhou, O, Pinder, M, Plant, M, Askin, N, et al. Effect of aerobic exercise on Dialysis-related symptoms in individuals undergoing maintenance hemodialysis: a systematic review and Meta-analysis of clinical trials. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. (2021) 16:560–74. doi: 10.2215/CJN.15080920

40. Parker, K, Raugust, S, Vink, B, Parmar, K, Fradsham, A, and Armstrong, M. The feasibility and effects of self-acupressure on symptom burden and quality of life in hemodialysis patients: a pilot RCT. Can J Kidney Health Dis. (2024) 11:20543581241267164. doi: 10.1177/20543581241267164

41. Borrelli, S, Provenzano, M, Gagliardi, I, Michael, A, Liberti, M, de Nicola, L, et al. Sodium intake and chronic kidney disease. Int J Mol Sci. (2020) 21:4744. doi: 10.3390/ijms21134744

42. Kim, SM, and Jung, JY. Nutritional management in patients with chronic kidney disease. Korean J Intern Med. (2020) 35:1279–90. doi: 10.3904/kjim.2020.408

43. Chen, Y, Li, Z, Liang, X, Zhang, M, Zhang, Y, Xu, L, et al. Effect of individual health education on hyperphosphatemia in the Hakkas residential area. Ren Fail. (2015) 37:1303–7. doi: 10.3109/0886022x.2015.1073072

44. Ren, Q, Shi, S, Yan, C, Liu, Y, Han, W, Lin, M, et al. Self-management Micro-video health education program for hemodialysis patients. Clin Nurs Res. (2022) 31:1148–57. doi: 10.1177/10547738211033922

45. Liang, MF, Wang, L, Zhao, J, Yuan, HY, Zhang, J, Wang, LJ, et al. Influence of peer support intervention on maintenance hemodialysis patients. Chin Nurs Res. (2024) 38:176–81. doi: 10.12102/j.issn.1009-6493.2024.01.031

46. Ghaffari, M, Morowatisharifabad, MA, Mehrabi, Y, Zare, S, Askari, J, and Alizadeh, S. What are the hemodialysis Patients' style in coping with stress? A directed content analysis. Int J Community Based Nurs Midwifery. (2019) 7:309–18. doi: 10.30476/IJCBNM.2019.81324.0

47. Calvey, D, and Mee, L. The lived experience of the person dependent on haemodialysis. J Ren Care. (2011) 37:201–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2011.00235.x

Keywords: hemodialysis, qualitative research, meta synthesis, nursing, young and middle aged

Citation: Zhang K, Teng Z, Li A, Zhang N, Wang R, Wei S and Ni C (2025) Real experience of young and middle-aged hemodialysis patients: a qualitative meta-synthesis. Front. Med. 12:1530465. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2025.1530465

Edited by:

Olga Catherina Damman, Amsterdam University Medical Center, NetherlandsReviewed by:

Wenlin Yang, University of Florida, United StatesDamiano Zemp, Ente Ospedaliero Cantonale (EOC), Switzerland

Copyright © 2025 Zhang, Teng, Li, Zhang, Wang, Wei and Ni. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cuiping Ni, Y3BuaUBjbXUuZWR1LmNu

†ORCID: Kai Zhang, orcid.org/0009-0002-5312-5010

Cuiping Ni, orcid.org/0009-0002-3535-9390

Kai Zhang

Kai Zhang Zeng Teng

Zeng Teng Ailing Li2

Ailing Li2