- 1Department of Health Services and Hospitals Administration, Faculty of Economics and Administration, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 2Health Economics Research Group, King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

- 3Department of Population Studies, University of Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana

Introduction: To achieve universal health coverage consistent with World Health Organization recommendations, monitoring financial protection is vital, even in the context of free medical care. Toward this end, this study investigated out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditure on medicines and their determinants among adults in Saudi Arabia.

Methods: This analysis was based on cross-sectional data derived from the Family Health Survey conducted by the General Authority for Statistics in 2018. Data analyses for this study were based on the total sample of 10,785 respondents. Descriptive statistics were used to identify the sample distribution for all variables included in the study. Tobit regression analysis was used to examine the determinants of OOP expenditure on medicines.

Results: The average OOP expenditure on medicines was estimated to be 279.69 Saudi Riyal in the sampled population. Tobit regression analysis showed that age, average household monthly income, education level, and suffering a chronic condition were the main determinants of OOP expenditure on medicines. Conversely, being married and employed were associated with a lower probability of OOP expenditure on medicines.

Conclusion: This study could assist policy makers to provide additional insurance funding and benefits to reduce the possibility of catastrophic OOP expenditure on medicines, especially for the most vulnerable demographic.

Introduction

There has generally been a global improvement in average household income and life expectancy in recent decades related to improvements in healthcare outcomes. Despite general improvements in quality of life in the general population, the opposite trend is evident for the older adult population (1). Most developed countries are experiencing an increase in the proportion of the older adult population, which is often associated with an increased prevalence of chronic non-communicable diseases and complex medical conditions, resulting in an increased demand for healthcare services, including access to medicines (2). Inequalities in medical supplies and resource distribution are likely to further affect the most socioeconomically disadvantaged populations (3, 4). The Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) projected that adult populations will significantly influence public expenditures, indicating that long-term care and health will comprise over half the rise in age-related societal costs by 2050. The increasing costs of medicines and general care may result in catastrophic health expenditure (CHE) and poverty in the near future (5–7). CHE occurs when a family’s health expenditure is equal to or more than 40% of the total family expenditure after subtracting subsistence costs (8, 9).

Out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures for healthcare utilization, medicines, and medical services of older adults are all higher than those of the general population (10–12). However, these data are based on studies from high-income countries (HICs), with less focus on the situation in low-and middle-income countries (LMICs) (13, 14). Moreover, relative OOP expenditure as a share of total spending on medicines among OECD member states (41% in 2011) was more than double that spent on healthcare services (18% in 2011) (15). The limited available evidence from LMICs corroborates these findings (12–14, 16).

It is estimated that over 150 million people are impacted by the economic burden of OOP health expenditure and that approximately 100 million people reach a state of poverty due to OOP medical and healthcare expenditures worldwide (17, 18), with the greatest experience by low-income families (19, 20). To provide protection against the adverse effects of OOP health expenditure, the World Health Assembly resolution recommended that member states should target the achievement of universal health coverage (UHC) (21) to ensure equal access to healthcare services utilization, especially when required, with no financial barriers. Achieving this goal involves multi-faceted strategies, including targeting the proportion of medical costs, variety of services, and number of people covered (22).

Given that the pharmaceutical market in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia (KSA) is the largest, most volatile, and most sophisticated in the Middle East and North Africa region, understanding the determinants of OOP expenditure on medicines in the KSA is vitally important. The majority of medicines provided to Saudi citizens are paid for by the government, while non-Saudi nationals are covered by mandatory private health insurance provided by employers (22). Individuals who use private health insurance are generally treated in the private sector. Since the KSA offers universal primary healthcare to the population, it is generally assumed that OOP expenditure on medicines and healthcare should be nominal. However, the most recent data suggest that retail sales account for 44% of medicine in terms of value (23).

Although the KSA is considered to be an HIC, it also has a notable low-income population (24–26). The provision of free healthcare services to its citizens imposes pressure on public health facilities that ultimately affects public healthcare provision. Some studies have demonstrated notable variation in OOP expenditure on medicines and health in general, even in the context of UHC for primary healthcare (19, 27, 28). The pharmaceutical industry and health financing system are evolving rapidly in the KSA (22, 23). Therefore, understanding the determinants of OOP expenditure on medicines is important for policy interventions.

The few studies on OOP health expenditure in the KSA focused on OOP expenditure for healthcare, health insurance, and chronic conditions to provide insight into the total or public resources devoted to health (10, 22, 29, 30); however, the determinants of OOP expenditure on prescribed medicines remain unclear. This may be due to the lack of adequate routine data on pharmaceutical expenditures collected at the individual and household levels.

To address this gap, this study investigated inequalities in OOP expenditure on medicines and their determinants among adults in the KSA based on data from a large national survey. Identifying the population with the highest risk of facing CHE and the consequent economic behaviors can guide policymakers to better target the distribution of public health insurance.

Methodology

Study design

This was a cross-sectional analysis of self-weighted data obtained from the 2018 Family Health Survey (FHS) (31), conducted by the General Authority for Statistics (GaStat) in Saudi Arabia in collaboration with various entities in the health sector of Saudi Arabia, including the Ministry of Health, Saudi Health Council, private organizations, and academic institutions.

Population and setting

The FHS is carried out every 3 years and falls under the classification of education and health statistics. The FHS collects information by visiting a representative sample of the population across all 13 administrative regions of Saudi Arabia.

Given its extensive coverage of health-related information and its representative nature, the FHS dataset was well-suited for examining the heterogeneous relationship between OOP expenditure on medicines and various explanatory variables.

Sample

The total sample size for the FHS was 15,265 responses, randomly selected from the 13 administrative regions of Saudi Arabia. Our analysis was limited to respondents who were aged 18 years or older and had completed information on all the variables of interest. After excluding those with missing responses to healthcare-related questions and covariates, the final sample consisted of 10,785 respondents.

Outcome variable

To examine the determinants of OOP expenditure on medicines in the KSA, the outcome variable was taken from a section of the FHS on health status where respondents were asked to report their average household monthly OOP expenditure on medicines prescribed by a healthcare professional and their average household monthly income (in Saudi Riyal [SR]). This is a continuous variable reported in SR (1 US$ = 3.75 SR). As a result, analysis of expenditures on non-prescribed medications is beyond the scope of this study.

Explanatory variables

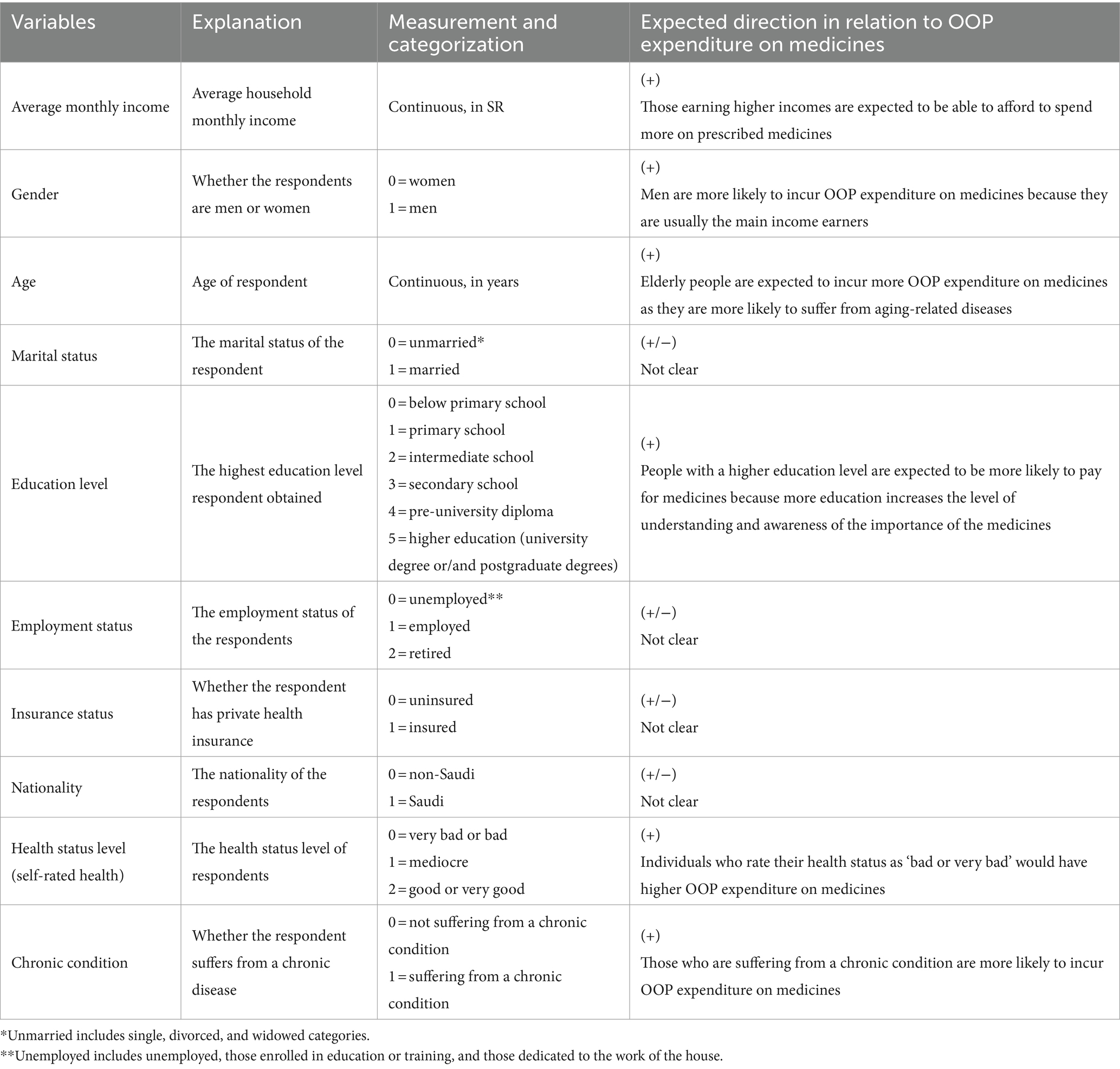

The survey also contains rich information on demographic and socioeconomic status. Among these, the selection of explanatory variables used in this study was derived from the existing literature on the determinants of OOP expenditure on medicines (32). Table 1 shows the list of the independent variables that could influence OOP expenditure in medicine, their explanation, measurement and categorization, and the expected direction of regression coefficients in relation to OOP expenditure in medicines.

The explanatory variables tested included personal, household, and health-related characteristics. Sum et al. (33) reported that personal characteristics such as gender, age, education, marital status, employment status, and nationality are very important predictors of whether or not individuals will utilize medicines. Income and educational level were found to be among the most important predictors of OOP expenditure on medicines in Eastern Asia (34).

Economic status, as measured by average household income, has been highlighted as a strong determinant of OOP expenditure on medicines (35). The same pattern has been shown in previous studies in the KSA, demonstrating a significant association of household income with OOP health expenditure in general (26). Therefore, we included monthly household income as a proxy for economic status in this study as this variable is reflective of the household’s overall wealth status (36).

We expected that higher monthly income would be positively correlated with the amount of OOP expenditure on medicines. Thus, we anticipated that households with higher monthly incomes would be able to afford to spend more on prescribed medicines compared to households with low monthly incomes. Indeed, households with low monthly incomes are more likely to spend a relatively larger portion of their budget on medicines compared to counterpart households with higher monthly incomes. Moreover, households with higher monthly incomes are characteristically wealthier, often have access to information, and therefore have better knowledge about healthcare (37). For example, they may know where to buy inexpensive medicines and where to obtain good price discounts for medicines. Consequently, household income was hypothesized to influence OOP expenditure on medicines.

Other important characteristics affecting the expenditures and utilization of medicines include health-related variables such as suffering from a chronic disease, health status level, and health insurance coverage. Suffering from a chronic disease was set as a dummy variable, which was hypothesized to be linked to the OOP expenditure on medicines. Having members in the household who suffer from chronic diseases requires more resources to be devoted to their care. Chronic conditions such as hypertension or diabetes require lifelong medication and therefore pose a heavy burden (38). Moreover, we hypothesized that individuals who rate their health status as ‘bad or very bad’ would have higher OOP expenditure on medicines. In other words, households with people who have poor health will need to spend more on the prescribed medications, thereby significantly increasing their vulnerability to poverty (39).

Although health insurance is opined to reduce OOP expenditure on medicines, the evidence on this association is at best mixed. While there is some evidence to suggest that health insurance indeed reduces OOP expenditure (40, 41), other studies indicate that health insurance coverage increases OOP expenditure (42–44). These contradictions invite the question of interrogating whether health insurance coverage reduces or increases OOP expenditure on medicines in the KSA. Although the KSA is categorized as an HIC, it has some attributes of LMICs (24), which make its context comparable to the related literature for both categories. Consequently, exploration of the link between insurance coverage and OOP expenditure on medicines in the KSA could help to explain the heterogeneous relationships reported in the literature to date.

Statistical analyses

Data analyses for this study were based on the total sample of 10,785 respondents. We used descriptive statistics to identify the sample distribution for all variables included in the study. Percentage, mean, and standard deviation (SD) values for OOP expenditure on medicines (our primary outcome) were calculated to describe the sample.

Tobit regression analysis (45) was used to identify the determinants of OOP expenditure on medicines prescribed by a healthcare professional, although ordinary least squares (OLS) multiple regression is typically used when continuous data are obtained from an open-ended question. However, the large number of survey responses of zero OOP expenditure on medicines raises concern about the continuity of the dependent variable. In addition, the OLS estimation fails to account for the qualitative differences between the limit observations (zero OOP expenditure on medicines) and non-limit observations (positive OOP expenditure on medicines) (46). This can lead to biased and inconsistent estimation of the marginal effects (47). It has been argued that the nature of the OOP expenditure question is continuous with censoring at zero. Therefore, the use of a standard linear regression model (48) with the Tobit model is deemed a more appropriate estimation technique in this context of such a limited dependent variable (46).

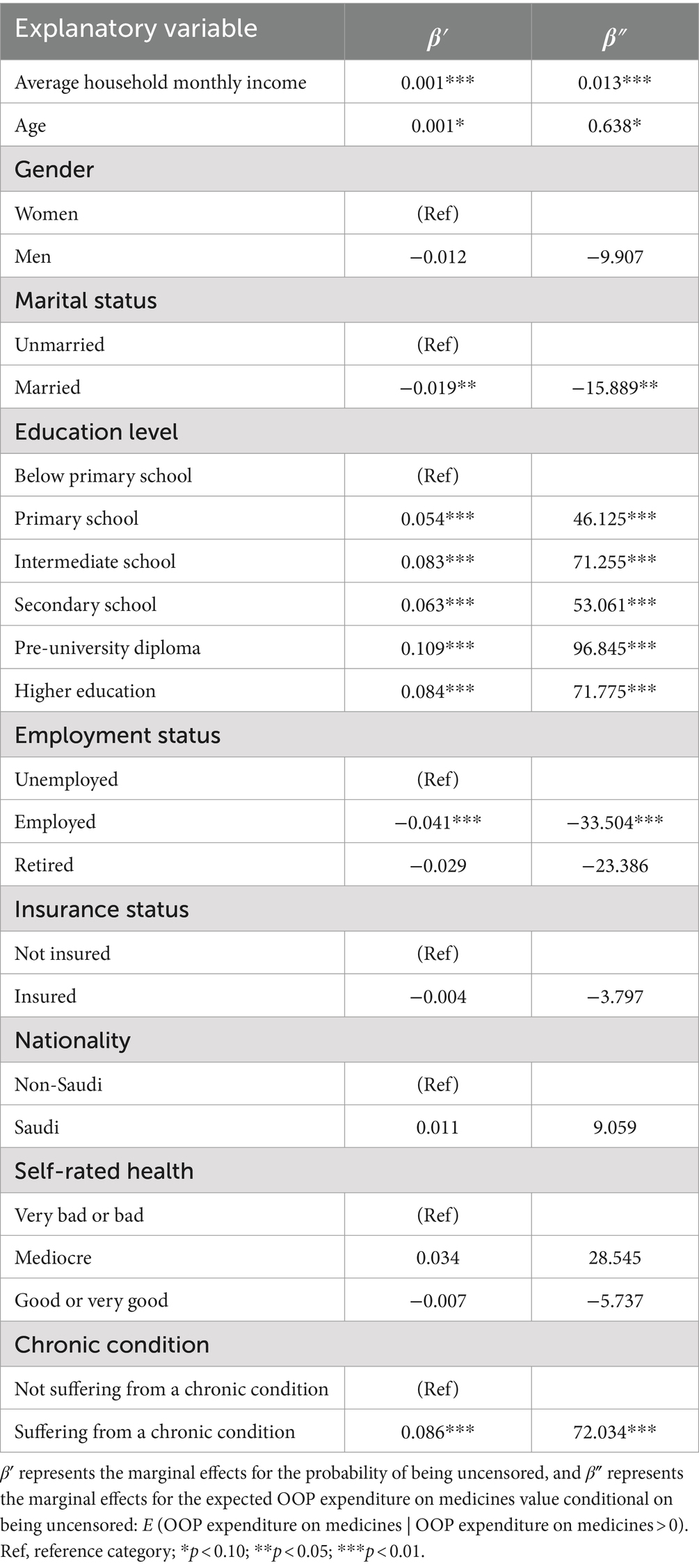

Previous studies have also indicated that the Tobit model is suitable for analyzing OOP expenditure when the nature of this variable is continuous with censoring at zero (44, 49–51). Consequently, Tobit regression analysis was used in this study to estimate the ‘beta’ coefficients associated with OOP expenditure on medicines in the KSA and examine how OOP expenditure on medicines varies based on respondents’ socioeconomic characteristics. The marginal effects, denoted as β′ and β″, were estimated. β″ represents the marginal effects for the probability of being uncensored, while β″ represents the marginal effects for the expected OOP expenditure on medicines conditional on being uncensored: E (OOP on medicines | OOP on medicines >0) (52, 53). All data analyses were performed using STATA SE 14 (StataCorp LP, TX, USA).

Results

Descriptive analysis

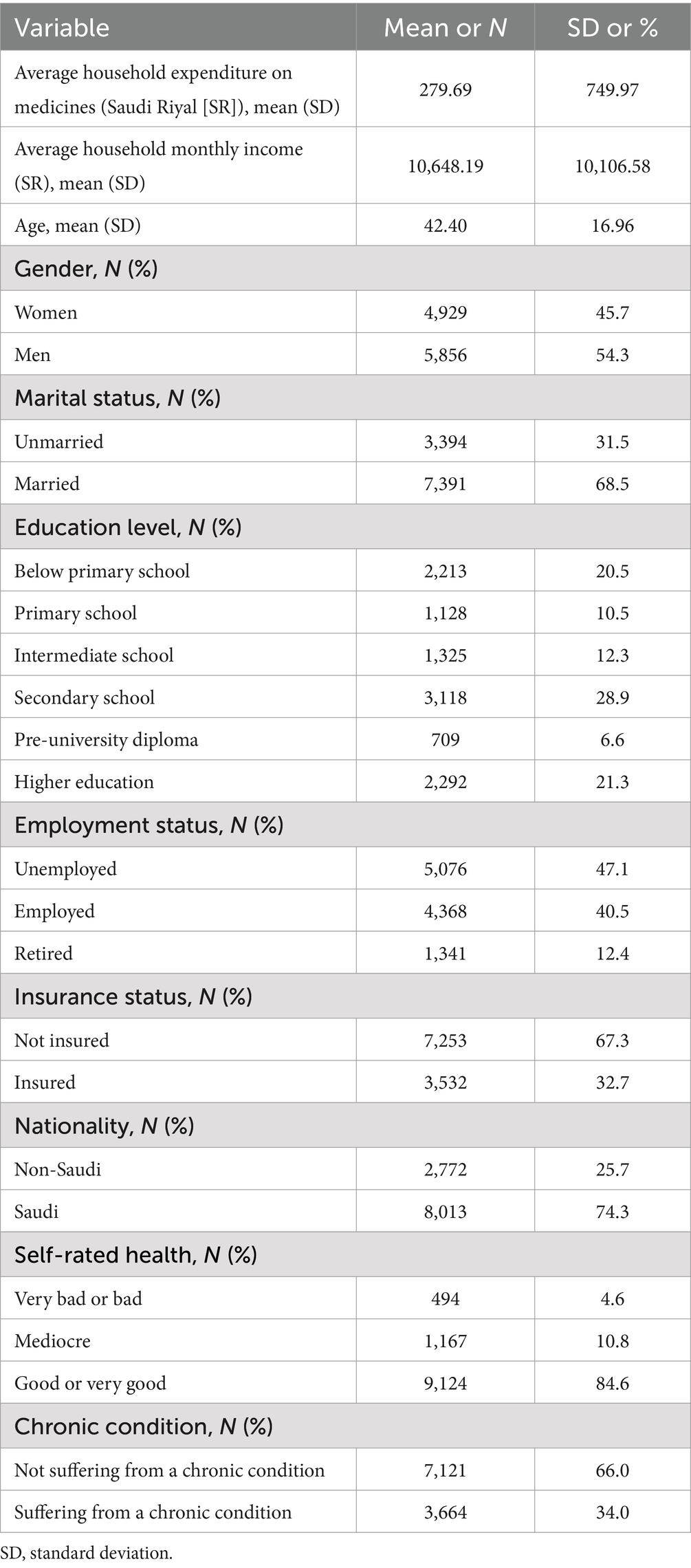

Table 2 shows the socioeconomic characteristics of the sample. The sample constituted a high proportion of men (54.3%), those who were married (68.5%), with secondary school education (28.9%), unemployed (47.1%), Saudi nationals (74.3%), those self-reporting a good or very good health status (84.6%), those not covered by health insurance (67.3%), and those who were not suffering from a chronic condition (66.0%).

Determinants of OOP expenditure on medicines

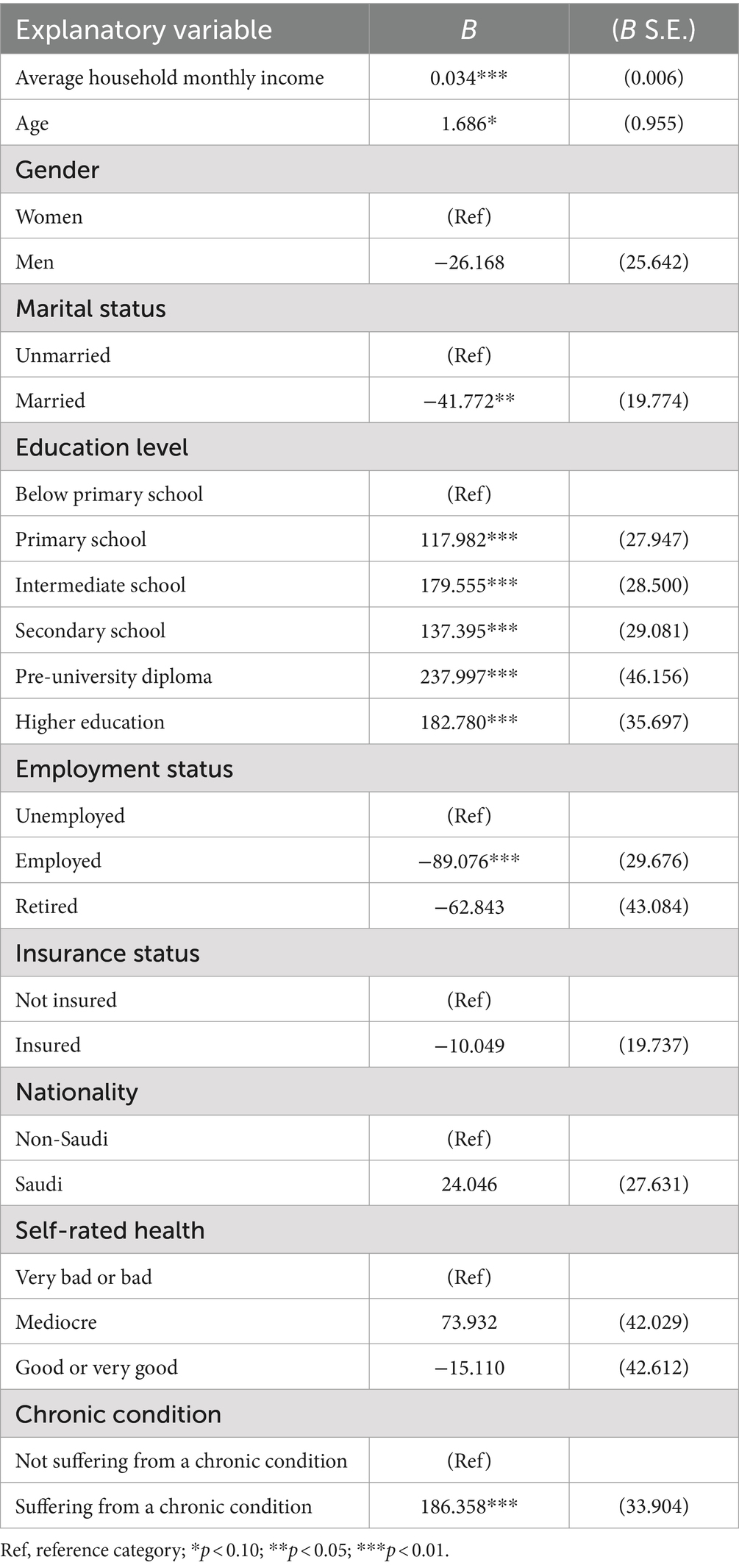

The results of the Tobit regression analysis are presented in Table 3, and the marginal effects are presented in Table 4. In accordance with a priori expectations, average household monthly income was significantly associated with OOP expenditure on medicines, suggesting that individuals earning higher income had a higher probability of spending OOP on medicines (p < 0.01). Moreover, the education variable also had a positive coefficient in the Tobit regression. This suggests the probability that an individual with a secondary school level of education and higher education level of education would have, respectively, 0.06 and 0.08 greater OOP expenditure on medicines than individuals with an education level of primary school or below. Moreover, those with secondary school education and those with higher education spent approximately 53 SR and 72 SR more, respectively, OOP on medicines than those with an education level below primary school. All these results were significant at a p-value of <0.001.

Moreover, age emerged as a significant factor contributing to OOP expenditures on medicine at a p-value of <0.1. This suggests that as age increases, the probability of spending OOP on medicines increases. Suffering from a chronic condition was also found to be significantly associated with OOP expenditure on medicines at a p-value of <0.01. Specifically, those suffering from a chronic condition had a 0.08 greater probability of spending OOP on medicines than those not suffering from a chronic condition, spending approximately 72 SR more than their counterparts. Conversely, marital status and employment status had negative coefficients in the Tobit model (Table 4), suggesting that married and employed individuals have an approximately 0.02 lower probability of spending OOP on medicines with significance at the 0.05 and 0.01 level, respectively.

Discussion

The findings of this study indicate that the sampled respondents paid an average of 279.69 SR OOP for medicines, even though Saudi Arabia provides free healthcare services to the general public (54). However, this finding is not surprising since some previous studies have shown that free public healthcare usually creates pressure on public health facilities and affects public healthcare provision (24, 25). As a result, some people, especially public sector employees, ultimately go to private health facilities and pay for prescribed medicines OOP, while others prefer the option of purchasing private health insurance packages to safeguard their income and wealth against the high prices of some medicines.

Age was found to be positively associated with OOP expenditure in medicines, suggesting that as age increases, the probability of spending OOP on medicines increases. This finding is consistent with other studies showing that OOP expenditure on medicines increases with age, with proximity to death resulting in higher medicine expenditure (55, 56). In the context of Saudi Arabia, two plausible reasons explain why increasing age is significantly linked to an increased likelihood of OOP expenditure in medicines. First, aging is often associated with medical complications, including chronic diseases. As a result, in cases where there are no medicines available in public health facilities for such conditions, medicines are acquired from private health facilities through OOP spending (10). Second, polypharmacy constitutes a high proportion of expenditure on medicines, especially among older adults. Aging places individuals at risk of multi-morbidity due to associated physiological and pathological changes and thereby increases the chances of being prescribed multiple medications (57).

In addition, the results showed an increased likelihood of OOP expenditure on medicines at all levels of education compared with that of individuals without primary school education. This finding indicates that individuals at all levels of education may be aware of the importance of health and have acquired more knowledge about healthcare alternatives, including OOP spending on medicines. This conclusion corroborates research performed in other highly developed and literate nations where the majority of the population exhibits a sufficient level of knowledge about their health (58, 59). The expectation was that individuals with higher education levels would spend more OOP on medicines compared to those with lower education due to affordability. Moreover, although healthcare services in the KSA are provided free at the point of use regardless of education level, the difference in OOP expenditure on medicines may reflect the unavailability of some medicines in public facilities (24, 25). The provision of free healthcare services by the KSA to the general public may not be sustainable, especially as the cost of financing healthcare in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia is exacerbated by the current rapid demographic changes, population aging, epidemiological transition, and increasing prices of medical technology (60).

We also found that suffering from a chronic condition increased the likelihood of OOP expenditure on medicines among the sampled respondents. This finding is in line with earlier published studies in both LMICs and HICs (61–63). For instance, Chen et al. (62) found that the OOP expenditure for patients with chronic diseases was more than three times higher than that of patients without chronic conditions. Excess spending on medicines for chronic illnesses is incessant, and, in the long-term, the compounding effects of OOP costs arising from chronic illnesses—together with lost income—can result in severe financial hardship, leading to catastrophic expenditure on medicines. In the context of the KSA, this finding highlights that public healthcare systems do not necessarily eliminate increased OOP expenditure on medicines.

Average household monthly income was significantly associated with OOP expenditure on medicines, suggesting that individuals earning higher income had a higher probability of OOP spending on medicines. Although this finding corroborates the results of related research in other regions (64, 65), it indicates a low probability of catastrophic expenditure in the KSA. However, it is possible that continued OOP expenditures on medicines can lead to catastrophic health expenditures and impoverishment in the long run, even in households with high monthly incomes.

Marital status and employment status showed negative coefficients in the Tobit model, indicating that married and employed individuals had a lower probability of OOP spending on medicines. These associations can be explained by the existence of medical insurance coverage, which is provided to employed individuals and their families in the country as a benefit package. This is consistent with the findings from other studies showing that medical insurance reduces the probability of OOP expenditure in health (66, 67). Moreover, being married has been significantly associated with medical insurance coverage in Saudi Arabia (22).

Our study has some limitations, which can be explored in future research. First, the measures of health-related variables and estimates of OOP expenditure on medicines are self-reported. As a result, the cost an individual would have spent on medicines is subject to recall bias or incomplete reporting; therefore, a more objective measure of the amount of OOP expenditure needs to be explored. Second, our analyses are cross-sectional and do not consider dynamic changes in OOP expenditure over time. However, this study has several notable strengths. First, it utilizes a large, nationally representative sample, enhancing the generalizability of the findings to the adult population in Saudi Arabia. In addition, by focusing specifically on OOP expenditures on medicines, this study fills a gap in the existing literature, particularly in the context of Saudi Arabia where most of the research in this field to date has focused on general healthcare costs. Furthermore, the use of Tobit regression analysis allows for a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing OOP expenditures, taking into account both zero expenditures and positive spending, which provides a more comprehensive view of the economic burden.

Conclusion

Age, average household monthly income, education level, and suffering from a chronic condition were significant determinants of OOP expenditure on medicines in the sampled population. The government of the KSA should consider increasing health insurance benefits for groups that are most vulnerable to CHE (i.e., families with low income and high household expenditure, those with a low education level, and those suffering from chronic conditions) due to excessive expenditures on medicines. This study could assist policymakers in providing additional insurance funding to reduce OOP expenditure on medicines.

Data availability statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to privacy, confidentiality, and other restrictions. Access to data can be gained through the General Authority for Statistics in Saudi Arabia via https://www.stats.gov.sa/en.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was not required for the studies involving humans because this study was based on the use of secondary data from the FHS, which was conducted, commissioned, funded, and managed in 2018 by GaStat that was in charge of all ethical procedures. All procedures performed in this study involving human participants complied with the institutional and/or national research committee ethical standards, and with the 1964 Helsinki Declaration and subsequent amendments or equivalent ethical standards. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. All personal identifiers were removed from the dataset by GaStat to allow for secondary data use. GaStat granted permission to use the data and thus no further clearance was necessary as this was performed at the data collection phase.

Author contributions

MKA: Conceptualization, Data curation, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Software, Supervision, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. MK: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This project was funded by the Deanship of Scientific Research (DSR) at King Abdulaziz University, Jeddah, under grant no. (GPIP: 128-120-2024). The authors, therefore, acknowledge with thanks DSR for technical and financial support.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Gwatidzo, SD, and Stewart Williams, J. Diabetes mellitus medication use and catastrophic healthcare expenditure among adults aged 50+ years in China and India: results from the WHO study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE). BMC Geriatr. (2017) 17:1–15. doi: 10.1186/s12877-016-0408-x

2. Dall, TM, Gallo, PD, Chakrabarti, R, West, T, Semilla, AP, and Storm, MV. An aging population and growing disease burden will require alarge and specialized health care workforce by 2025. Health Aff. (2013) 32:2013–20. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2013.0714

3. WHO . Handbook on health inequality monitoring: with a special focus on low-and middle-income countries. Geneva: World Health Organization (2013).

4. Zhang, T, Xu, Y, Ren, J, Sun, L, and Liu, C. Inequality in the distribution of health resources and health services in China: hospitals versus primary care institutions. Int J Equity Health. (2017) 16:1–8. doi: 10.1186/s12939-017-0543-9

5. Rahman, MM, Gilmour, S, Saito, E, Sultana, P, and Shibuya, K. Health-related financial catastrophe, inequality and chronic illness in Bangladesh. PLoS One. (2013) 8:e56873. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0056873

6. Sun, J, and Lyu, S. The effect of medical insurance on catastrophic health expenditure: evidence from China. Cost Effectiv Resour Alloc. (2020) 18:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12962-020-00206-y

7. Zhao, S-W, Zhang, X-Y, Dai, W, Ding, Y-X, Chen, J-Y, and Fang, P-Q. Effect of the catastrophic medical insurance on household catastrophic health expenditure: evidence from China. Gac Sanit. (2021) 34:370–6. doi: 10.1016/j.gaceta.2018.10.005

8. Ekman, B . Catastrophic health payments and health insurance: some counterintuitive evidence from one low-income country. Health Policy. (2007) 83:304–13. doi: 10.1016/j.healthpol.2007.02.004

9. Xu, K, Evans, DB, Kawabata, K, Zeramdini, R, Klavus, J, and Murray, CJ. Household catastrophic health expenditure: a multicountry analysis. Lancet. (2003) 362:111–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13861-5

10. Al-Hanawi, MK . Decomposition of inequalities in out-of-pocket health expenditure burden in Saudi Arabia. Soc Sci Med. (2021) 286:114322. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.114322

11. Borde, MT, Kabthymer, RH, Shaka, MF, and Abate, SM. The burden of household out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures in Ethiopia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Equity Health. (2022) 21:1–20. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01610-3

12. Park, E-J, Kwon, J-W, Lee, E-K, Jung, Y-H, and Park, S. Out-of-pocket medication expenditure burden of elderly Koreans with chronic conditions. Int J Gerontol. (2015) 9:166–71. doi: 10.1016/j.ijge.2014.06.005

13. Mekuria, GA, and Ali, EE. The financial burden of out of pocket payments on medicines among households in Ethiopia: analysis of trends and contributing factors. BMC Public Health. (2023) 23:1–12. doi: 10.1186/s12889-023-15751-3

14. Sanwald, A, and Theurl, E. Out-of-pocket expenditures for pharmaceuticals: lessons from the Austrian household budget survey. Eur J Health Econ. (2017) 18:435–47. doi: 10.1007/s10198-016-0797-y

15. OECD . Health at a glance 2013: OECD indicators. (2013). Available at: https://www.oecd.org/els/health-systems/Health-at-a-Glance-2013.pdf (Accessed June 4, 2024).

16. Du, J, Yang, X, Chen, M, and Wang, Z. Socioeconomic determinants of out-of-pocket pharmaceutical expenditure among middle-aged and elderly adults based on the China health and retirement longitudinal survey. BMJ Open. (2019) 9:e024936. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-024936

17. Aregbeshola, BS, and Khan, SM. Out-of-pocket payments, catastrophic health expenditure and poverty among households in Nigeria 2010. Int J Health Policy Manag. (2018) 7:798–806. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2018.19

18. WHO . The world health report: Health systems financing: the path to universal coverage: executive summary. Geneva: World Health Organization (2010).

19. Kanmiki, EW, Bawah, AA, Phillips, JF, Awoonor-Williams, JK, Kachur, SP, Asuming, PO, et al. Out-of-pocket payment for primary healthcare in the era of national health insurance: evidence from northern Ghana. PLoS One. (2019) 14:e0221146. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0221146

20. WHO . Designing health financing systems to reduce catastrophic health expenditure. Geneva: World Health Organization (2005).

21. World Bank Group . High-performance health financing for universal health coverage: driving sustainable, inclusive growth in the 21st century. Washington DC: World Bank (2019).

22. Al-Hanawi, MK, Mwale, ML, and Qattan, AM. Health insurance and out-of-pocket expenditure on health and medicine: heterogeneities along income. Front Pharmacol. (2021) 12:638035. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2021.638035

23. Alghaith, T., Almoteiry, K., Alamri, A., Alluhidan, M., Alharf, A., Al-Hammad, B., et al. “Strengthening the pharmaceutical system in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia”: World Bank Group; Saudi Health Council. (2020). Available at: https://openknowledge.worldbank.org/server/api/core/bitstreams/0d9e9ffa-1e49-51df-b0c7-84d22858b410/content (Accessed December 28, 2023).

24. Al-Hanawi, MK, Alsharqi, O, Almazrou, S, and Vaidya, K. Healthcare finance in the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia: a qualitative study of householders’ attitudes. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. (2018) 16:55–64. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0353-7

25. Al-Hanawi, MK, Alsharqi, O, and Vaidya, K. Willingness to pay for improved public health care services in Saudi Arabia: a contingent valuation study among heads of Saudi households. Health Econ Policy Law. (2020) 15:72–93. doi: 10.1017/S1744133118000191

26. Al-Hanawi, MK, Vaidya, K, Alsharqi, O, and Onwujekwe, O. Investigating the willingness to pay for a contributory national health insurance scheme in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional stated preference approach. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. (2018) 16:259–71. doi: 10.1007/s40258-017-0366-2

27. Masiye, F, and Kaonga, O. Determinants of healthcare utilisation and out-of-pocket payments in the context of free public primary healthcare in Zambia. Int J Health Policy Manag. (2016) 5:693–703. doi: 10.15171/ijhpm.2016.65

28. Taniguchi, H, Rahman, MM, Swe, KT, Islam, MR, Rahman, MS, Parsell, N, et al. Equity and determinants in universal health coverage indicators in Iraq, 2000–2030: a national and subnational study. Int J Equity Health. (2021) 20:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12939-021-01532-0

29. Al-Hanawi, MK, and Njagi, P. Assessing the inequality in out-of-pocket health expenditure among the chronically and non-chronically ill in Saudi Arabia: a Blinder-Oaxaca decomposition analysis. Int J Equity Health. (2022) 21:1–11. doi: 10.1186/s12939-022-01810-5

30. Almalki, ZS, Alahmari, AK, Alshehri, AM, Altowaijri, A, Alluhidan, M, Ahmed, N, et al. Investigating households’ out-of-pocket healthcare expenditures based on number of chronic conditions in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study using quantile regression approach. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e066145. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2022-066145

31. GaStat . General authority for statistics: family health survey. (2018). Available at: https://www.stats.gov.sa/en/965 (Accessed January 1, 2023).

32. Ambade, M, Sarwal, R, Mor, N, Kim, R, and Subramanian, S. Components of out-of-pocket expenditure and their relative contribution to economic burden of diseases in India. JAMA Netw Open. (2022) 5:e2210040–09. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.10040

33. Sum, G, Hone, T, Atun, R, Millett, C, Suhrcke, M, Mahal, A, et al. Multimorbidity and out-of-pocket expenditure on medicines: a systematic review. BMJ Glob Health. (2018) 3:e000505. doi: 10.1136/bmjgh-2017-000505

34. Jakovljevic, M, Sugahara, T, Timofeyev, Y, and Rancic, N. Predictors of (in) efficiencies of healthcare expenditure among the leading Asian economies–comparison of OECD and non-OECD nations. Risk Manag Healthc Policy. (2020) 13:2261–80. doi: 10.2147/RMHP.S266386

35. Mate, K, Bryan, C, Deen, N, and McCall, J. Review of health systems of the Middle East and North Africa region. Int Encycl Public Health. (2017) 4:347. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-803678-5.00303-9

36. Jowett, M, Brunal, MP, Flores, G, and Cylus, J. Spending targets for health: no magic number. Geneva: World Health Organization (2016).

37. Dash, A, and Mohanty, SK. Do poor people in the poorer states pay more for healthcare in India? BMC Public Health. (2019) 19:1–17. doi: 10.1186/s12889-019-7342-8

38. Rowley, J, Richards, N, Carduff, E, and Gott, M. The impact of poverty and deprivation at the end of life: a critical review. Palliat Care Soc Pract. (2021) 15:26323524211033873. doi: 10.1177/26323524211033873

39. Sirag, A, and Mohamed Nor, N. Out-of-pocket health expenditure and poverty: evidence from a dynamic panel threshold analysis. Healthcare. (2021) 9:1–20. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9050536

40. Barnes, AJ, and Hanoch, Y. Knowledge and understanding of health insurance: challenges and remedies. Isr J Health Policy Res. (2017) 6:1–3. doi: 10.1186/s13584-017-0163-2

41. Harish, R, Suresh, RS, Rameesa, S, Laiveishiwo, P, Loktongbam, PS, Prajitha, K, et al. Health insurance coverage and its impact on out-of-pocket expenditures at a public sector hospital in Kerala, India. J Family Med Prim Care. (2020) 9:4956–61. doi: 10.4103/jfmpc.jfmpc_665_20

42. Chernew, M, Cutler, DM, and Keenan, PS. Increasing health insurance costs and the decline in insurance coverage. Health Serv Res. (2005) 40:1021–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2005.00409.x

43. Ekholuenetale, M, and Barrow, A. Inequalities in out-of-pocket health expenditure among women of reproductive age: after-effects of national health insurance scheme initiation in Ghana. J Egypt Public Health Assoc. (2021) 96:1–14. doi: 10.1186/s42506-020-00064-9

44. Sriram, S, and Khan, MM. Effect of health insurance program for the poor on out-of-pocket inpatient care cost in India: evidence from a nationally representative cross-sectional survey. BMC Health Serv Res. (2020) 20:1–21. doi: 10.1186/s12913-020-05692-7

45. Tobin, J . Estimation of relationships for limited dependent variables. Econometrica. (1958) 26:24–36. doi: 10.2307/1907382

46. Donaldson, C, Jones, AM, Mapp, TJ, and Olson, JA. Limited dependent variables in willingness to pay studies: applications in health care. Appl Econ. (1998) 30:667–77. doi: 10.1080/000368498325651

48. Manning, WG . The logged dependent variable, heteroscedasticity, and the retransformation problem. J Health Econ. (1998) 17:283–95. doi: 10.1016/S0167-6296(98)00025-3

49. da Silva, MT, Barros, AJ, Bertoldi, AD, de Andrade Jacinto, P, Matijasevich, A, Santos, IS, et al. Determinants of out-of-pocket health expenditure on children: an analysis of the 2004 Pelotas birth cohort. Int J Equity Health. (2015) 14:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12939-015-0180-0

50. Jeetoo, J, and Jaunky, VC. An empirical analysis of income elasticity of out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure in mauritius. Healthcare. (2022) 10:101. doi: 10.3390/healthcare10010101

51. Mugisha, F, Kouyate, B, Gbangou, A, and Sauerborn, R. Examining out-of-pocket expenditure on health care in Nouna, Burkina Faso: implications for health policy. Trop Med Int Health. (2002) 7:187–96. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3156.2002.00835.x

52. Ekstrand, C, and Carpenter, T. Using a tobit regression model to analyse risk factors for foot-pad dermatitis in commercially grown broilers. Prev Vet Med. (1998) 37:219–28. doi: 10.1016/S0167-5877(98)00090-7

53. McDonald, JF, and Moffitt, RA. The uses of Tobit analysis. Rev Econ Stat. (1980) 62:318–21. doi: 10.2307/1924766

54. Walston, S, Al-Harbi, Y, and Al-Omar, B. The changing face of healthcare in Saudi Arabia. Ann Saudi Med. (2008) 28:243–50. doi: 10.5144/0256-4947.2008.243

55. Chen, J, Zhao, M, Zhou, R, Ou, W, and Yao, P. How heavy is the medical expense burden among the older adults and what are the contributing factors? A literature review and problem-based analysis. Front Public Health. (2023) 11:1165381. doi: 10.3389/fpubh.2023.1165381

56. De Nardi, M, French, E, and Jones, JB. Why do the elderly save? The role of medical expenses. J Polit Econ. (2010) 118:39–75. doi: 10.1086/651674

57. Masnoon, N, Shakib, S, Kalisch-Ellett, L, and Caughey, GE. What is polypharmacy? A systematic review of definitions. BMC Geriatr. (2017) 17:1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12877-017-0621-2

58. Hong, GS, and Kim, SY. Out-of-pocket health care expenditure patterns and financial burden across the life cycle stages. J Consum Aff. (2000) 34:291–313. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6606.2000.tb00095.x

59. You, X, and Kobayashi, Y. Determinants of out-of-pocket health expenditure in China: analysis using China health and nutrition survey data. Appl Health Econ Health Policy. (2011) 9:39–49. doi: 10.2165/11530730-000000000-00000

60. Almalki, M, FitzGerald, G, and Clark, M. Health care system in Saudi Arabia: an overview. East Mediter Health J. (2011) 17:784–93, 2011. doi: 10.26719/2011.17.10.784

61. Blakely, T, Kvizhinadze, G, Atkinson, J, Dieleman, J, and Clarke, P. Health system costs for individual and comorbid noncommunicable diseases: an analysis of publicly funded health events from New Zealand. PLoS Med. (2019) 16:e1002716. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002716

62. Chen, H, Chen, Y, and Cui, B. The association of multimorbidity with healthcare expenditure among the elderly patients in Beijing, China. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. (2018) 79:32–8. doi: 10.1016/j.archger.2018.07.008

63. Zhao, Y, Zhang, P, Oldenburg, B, Hall, T, Lu, S, Haregu, TN, et al. The impact of mental and physical multimorbidity on healthcare utilization and health spending in China: a nationwide longitudinal population-based study. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. (2021) 36:500–10. doi: 10.1002/gps.5445

64. Larkin, J, Walsh, B, Moriarty, F, Clyne, B, Harrington, P, and Smith, SM. What is the impact of multimorbidity on out-of-pocket healthcare expenditure among community-dwelling older adults in Ireland? A cross-sectional study. BMJ Open. (2022) 12:e060502. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2021-060502

65. Van Minh, H, Phuong, NTK, Saksena, P, James, CD, and Xu, K. Financial burden of household out-of pocket health expenditure in Viet Nam: findings from the national living standard survey 2002–2010. Soc Sci Med. (2013) 96:258–63. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2012.11.028

66. Choi, JW, Kim, TH, Jang, SI, Jang, SY, Kim, W-R, and Park, EC. Catastrophic health expenditure according to employment status in South Korea: a population-based panel study. BMJ Open. (2016) 6:e011747. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-011747

Keywords: determinants, expenditure, out-of-pocket, medicines, Saudi Arabia

Citation: Al-Hanawi MK and Keetile M (2024) Determinants of out-of-pocket expenditure on medicines among adults in Saudi Arabia: a cross-sectional study. Front. Med. 11:1478412. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1478412

Edited by:

Redhwan Ahmed Al-Naggar, National University of Malaysia, MalaysiaReviewed by:

Dalia Almaghaslah, King Khalid University, Saudi ArabiaSultan Alotaibi, King Fahd Armed Forces Hospital, Saudi Arabia

Sameer Shaikh, University of Hail, Saudi Arabia

Copyright © 2024 Al-Hanawi and Keetile. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mohammed Khaled Al-Hanawi, bWthbGhhbmF3aUBrYXUuZWR1LnNh

Mohammed Khaled Al-Hanawi

Mohammed Khaled Al-Hanawi Mpho Keetile

Mpho Keetile