- 1Department of Clinical Laboratory, Hebei Yiling Hospital, Shijiazhuang, China

- 2Department of Clinical Laboratory, Hebei Medical University Third Hospital, Shijiazhuang, China

- 3Department of Orthopedics, Hebei Medical University Third Hospital, Shijiazhuang, China

- 4Department of Myasthenia Gravis, Hebei Yiling Hospital, Shijiazhuang, China

- 5Hebei Key Laboratory of Intractable Pathogens, Shijiazhuang Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Shijiazhuang, China

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease. Patients with MG due to compromised autoimmune regulation, progressive muscle weakness, and prolonged use of immunosuppressants and glucocorticoid, often present with concomitant infections. However, cases of MG complicated by Nocardia infection are rare. In this case, we report MG complicated with pulmonary infection by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica. A 71-year-old male farmer who was admitted for management of MG. After 7 weeks of treatment of MG, the patient reported improvement. However, clinical presentation, inflammatory markers, and imaging findings supported a diagnosis of pulmonary infection. To further elucidate the etiology, Nocardia was identified in sputum smear microscopy and sputum culture, with 16S rRNA gene sequencing confirming N. cyriacigeorgica. The patient was prescribed trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole. After 1 month of treatment, clinical symptoms of MG and pulmonary nocardiosis showed significant improvement. Additionally, we searched PubMed for case reports of Nocardia cyriacigeorgica pulmonary infection from 2010 to 2024 and conducted a statistical analysis of the case information. This report aims to highlights the increased risk of pulmonary Nocardia infection in MG patients after the use of steroids and immunosuppressants, thereby enhancing clinical awareness.

Introduction

Myasthenia gravis (MG) is an autoimmune disease characterized by neuromuscular junction transmission impairment mediated by autoantibodies. Nocardia spp. are commonly found in soil, rotten plants and dust particles. Nocardiosis most commonly presents as primary skin infections, pulmonary infections, and disseminated infections (1). Nocardia infections are predominantly observed in immunocompromised individuals or those on long-term immunosuppressive therapy (2), also in patients with underlying lung disease (3). Patients with MG due to compromised autoimmune regulation, progressive muscle weakness, and prolonged use of immunosuppressants and glucocorticoids, often present with concomitant infections. Muralidhar Reddy et al. reviewed 21 cases of MG patients with concurrent nocardiosis (4). Until now, only one case of pulmonary nocardiosis caused by N. cyriacigeorgica has been identified in a patient with MG at the species level (5).

Case presentation

A 71-year-old male farmer from Hebei, China, presented with left upper eyelid ptosis in July 2021. He sought medical attention at a local hospital where the edrophonium test yielded positive results. The symptoms fluctuated while receiving treatment with acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. Gradually, weakness in the limbs and difficulty swallowing emerged. In September 2021, further consultation was sought at Hebei Yiling Hospital. The clinical manifestations included bilateral ptosis of the upper eyelids; weakness and easy fatigue of the muscles in the face, neck and limbs; and shortness of breath, with symptoms worsening after activity. The absolute score for myasthenia gravis (MG) was 31 points. Repetitive nerve stimulation demonstrates a wave amplitude decrement >10% in the accessory nerve and bilateral facial nerves. Admitted on September 2nd for MG, with a medical history including right eye enucleation and coronary artery stent placement (regularly taking aspirin enteric-coated tablets, isosorbide dinitrate tablets, and metoprolol tartrate tablets).

Upon hospital admission, arterial blood gas analysis revealed a respiratory acidosis concomitant with metabolic alkalosis (pH 7.39, PO2 40.0 mmHg, PCO2 52.0 mmHg, HCO3 31.5 mmol/L). Some indicators in the blood routine were slightly elevated (WBC 7.53 × 10^9/L, NEUT% 75.8). Additionally, the patient exhibited elevated blood glucose levels (2-h postprandial blood glucose >11 mmol/L). In summary, the patient was treated diabetes with repaglinide tablets (1 mg, tid). For the treatment of MG, in September 2021, acetylcholinesterase inhibitor pyridostigmine bromide (60 mg, qid), glucocorticoid methylprednisolone tablets (20 mg, qd), and immunosuppressants tacrolimus and cyclophosphamide (tacrolimus capsules 2 mg qd AM, followed by 1 mg qd PM. IV infusion of 500 mL 0.9% NaCl with cyclophosphamide 0.4 g, biw). Concurrent traditional Chinese medicine can enhance the therapeutic effects. The efficacy of traditional Chinese medicine mainly lies in enhancing the body's yang energy through warming and tonifying methods, while simultaneously regulating the meridians to promote the circulation of qi and blood, supplementing nutrients or energy, and regulating the extraordinary meridians. The main components of the traditional Chinese medicine are Astragalus, Ginseng, Ophiopogon, Schisandra, Reishi Mushroom, Angelica, Deer Antler, Dodder Seed, Cistanche, Morinda, Platycodon, and Cimicifuga. After 7 weeks of treatment, the patient reported slight improvement in bilateral upper eyelid ptosis, reduced fatigue during swallowing, alleviated limb weakness, less neck fatigue, and improved shortness of breath than before.

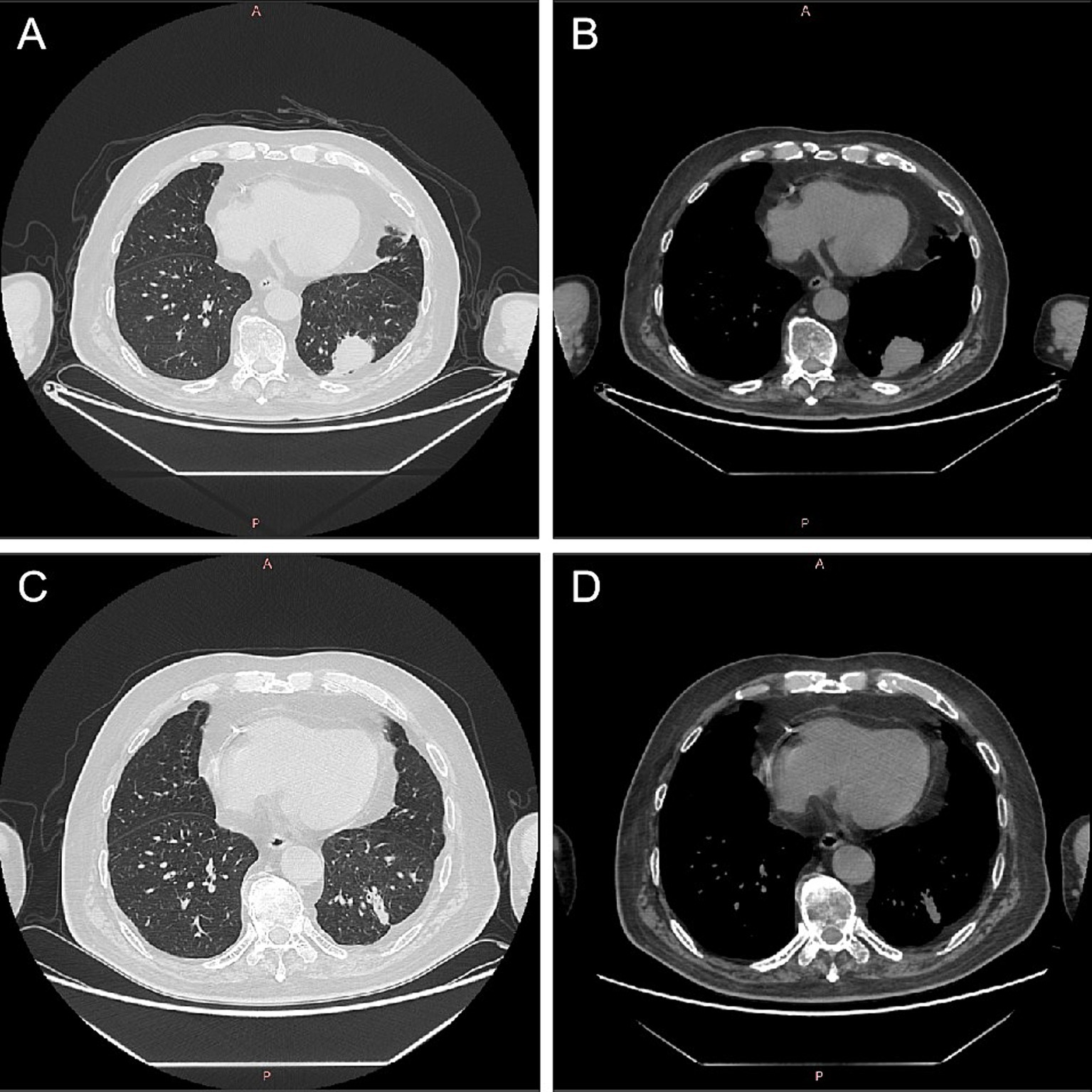

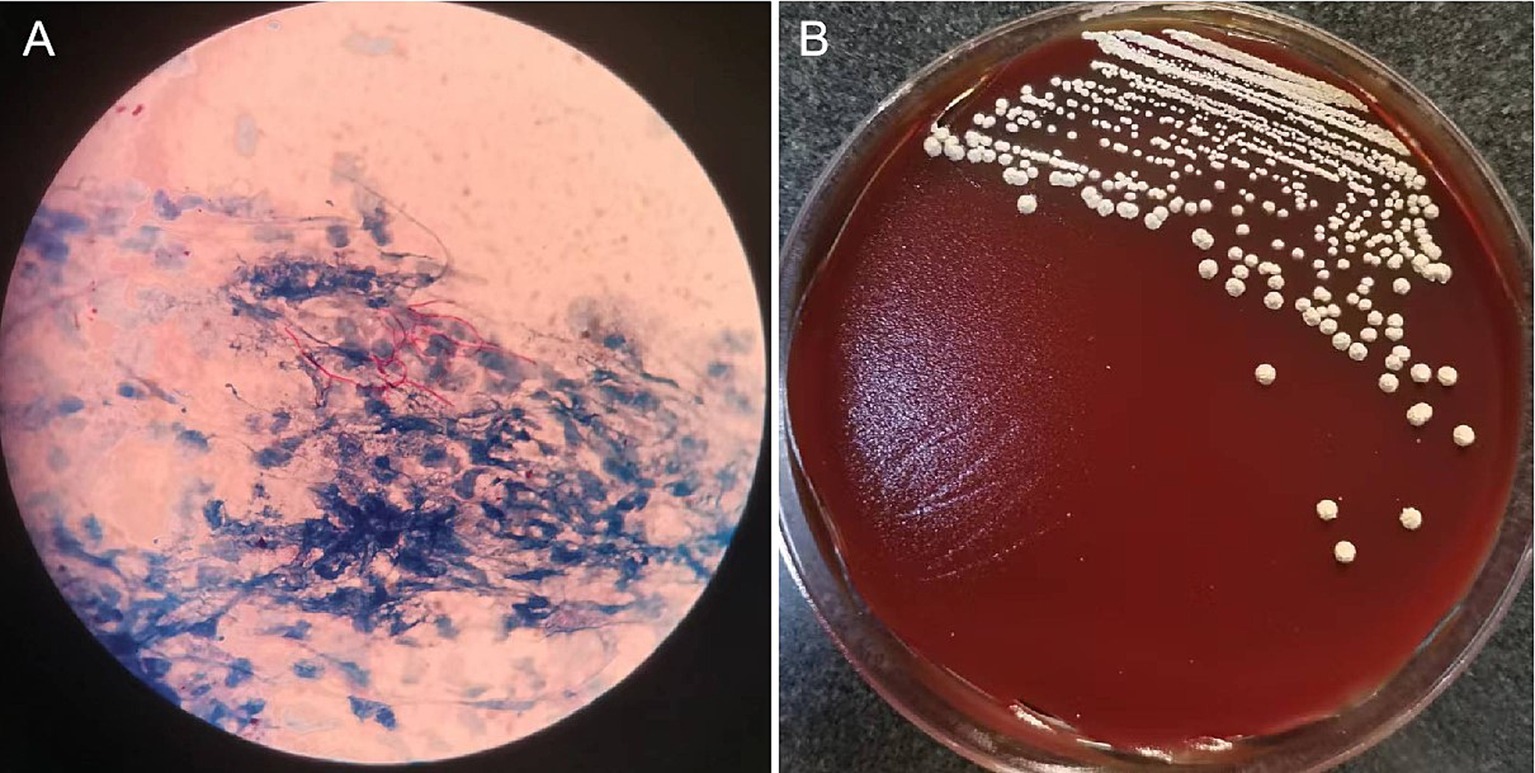

On October 23, 2021, the patient presented with coughing, sputum production, nasal congestion, and rhinorrhea. Monitoring revealed blood glucose level of 18.2 mmol/L, and elevated inflammatory markers in blood routine (WBC 13.09 × 10^9/L, NEUT% 93.5, CRP 120.7 mg/L). Chest CT showed newly developed localized consolidation in the basal segment of the left lower lobe (Figures 1A,B). Clinical symptoms, inflammatory markers, and imaging support the diagnosis of pulmonary infection. Treatment with ceftriaxone sodium/tazobactam sodium for 5 days showed unsatisfactory results. To further clarify the etiology, filamentous rods with positive weak acid-fast staining were found in 3 days' consecutive sputum smears (Figure 2A), highly suggestive of Nocardia. White candida growth was observed in microbial culture after 48 h, with negative results in the G test, ruling out Candida infection. Dry, biting agar-like colonies grew on blood agar after 3 days. After 5 days, the colonies become wrinkled and stacked like leather, with velvety aerial mycelia on the surface (Figure 2B). Upon sequencing of the 16S rRNA gene, exhibited a 99.9% nucleotide homology with N. cyriacigeorgica (NR117334.1) in the NCBI database. These sequences were submitted to the SRA database at NCBI with the accession number PP178562.

Figure 1. Computed tomography images of lungs before and after Nocardia treatment. After 2 months of treatment for myasthenia gravis, there was localized consolidation in the basal segment of the left lower lobe of the lung (A,B). Following 1 month of treatment with trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole for Nocardia cyriacigeorgica, chest CT showed a localized solid lesion in the basal segment of the lower lobe of the left lung, which was less extensive than before (C,D). CT, computed tomography.

Figure 2. Microscopic pictures of Nocardia and colonies isolated from sputum sample.The sputum sample revealed filamentous rods with weak acid-fast staining (A). On Colombia blood agar, grown at 37°C for 5 days, the colonies become wrinkled and stacked like leather, with velvety aerial mycelia on the surface (B).

Considering the possibility of infection related to immunosuppression, cyclophosphamide and methylprednisolone were discontinued while retaining traditional Chinese medicine, tacrolimus and pyridostigmine bromide. Additionally, the patient was prescribed trimethoprim–sulfamethoxazole (TMP-SMX; 2 tablets bid) for the treatment of N. cyriacigeorgica infection. After 7 weeks of treatment for MG, the patient reported slight improvement in bilateral upper eyelid ptosis, reduced fatigue during swallowing, alleviated limb weakness, reduced neck fatigue, and improved shortness of breath. After 1 month of standardized treatment for N. cyriacigeorgica infection, on December 1, 2021, the inflammatory indicators in the routine blood tests showed a significant decrease (WBC 7.25 × 109/L, 78.4% neutrophils, 16.4% lymphocytes, and CRP 16.9 mg/L). Chest CT showed a localized solid lesion in the basal segment of the lower lobe of the left lung, which was less extensive than before (Figures 1C,D). Bilateral drooping eyelids, shortness of breath, weakness in chewing, and weakness in both lower limbs improved. The absolute score for MG was 6 points, and the treatment outcome was judged as essentially cured. The clinical symptoms of MG and pulmonary Nocardia infection had improved, and it was agreed to discharge the patient. Until now, there has been no recurrence of the Nocardia infection in the lungs.

Discussion

MG is an autoimmune disorder characterized by impaired neuromuscular transmission mediated by autoantibodies. Patients are categorized into early-onset (≥18 and <50 years), late-onset (>50 years) and very late-onset MG (≥65 years) (6). Skeletal muscles throughout the body can be affected, manifesting as fluctuating weakness and fatigability, with symptoms showing a pattern of worsening in the morning and improving in the evening, they are exacerbated by activity and alleviated by rest. The genus Nocardia is a group of aerobic actinomycetes, Gram-positive bacteria, with some species exhibiting weak acid-fast staining. They are commonly found in soil, rotten plants and dust particles (2). The disease caused by Nocardia mainly manifests in three forms: pulmonary infection (the most common), disseminated infection, and primary cutaneous and soft tissue infections (7). Nocardiosis is prevalent among individuals with immunodeficiency or long-term use of immunosuppressive agents.

Research shows that patients with MG often experience concomitant infections due to the combined effects of compromised autoimmune regulation, progressive deterioration of myasthenia, and long-term use of immunosuppressants and hormones (8, 9). Muralidhar Reddy et al. conducted a statistical analysis on 21 cases of nocardiosis in MG patients, identifying risk factors for Nocardia infection, including elderly men, thymoma, immunosuppressive therapy, and pre-existing pulmonary diseases (4). Nocardia farcinica and Nocardia asteroides were more common pathogens (4). The investigation into the etiology of N. cyriacigeorgica infection in the patient reveals several key points. The patient in this case was an older man working in agriculture. It is possible that he inhaled Nocardia while working in the fields, initially resulting in colonization throughout the body. MG can induce respiratory muscle weakness, leading to symptoms such as respiratory distress, weak coughing, dyspnea, and dysphagia, which impede the clearance of pathogens. Systemic hormone therapy, especially when used in conjunction with other immunosuppressants, compromises the immune system. Misra et al. indicated that 88% of patients exhibit comorbidities, notably prevalent in the late-onset group, with cardiovascular diseases being common (10). Our patient had multiple comorbidities, including type 2 diabetes mellitus and a history of coronary artery stenting, which exacerbated the risk of infection.

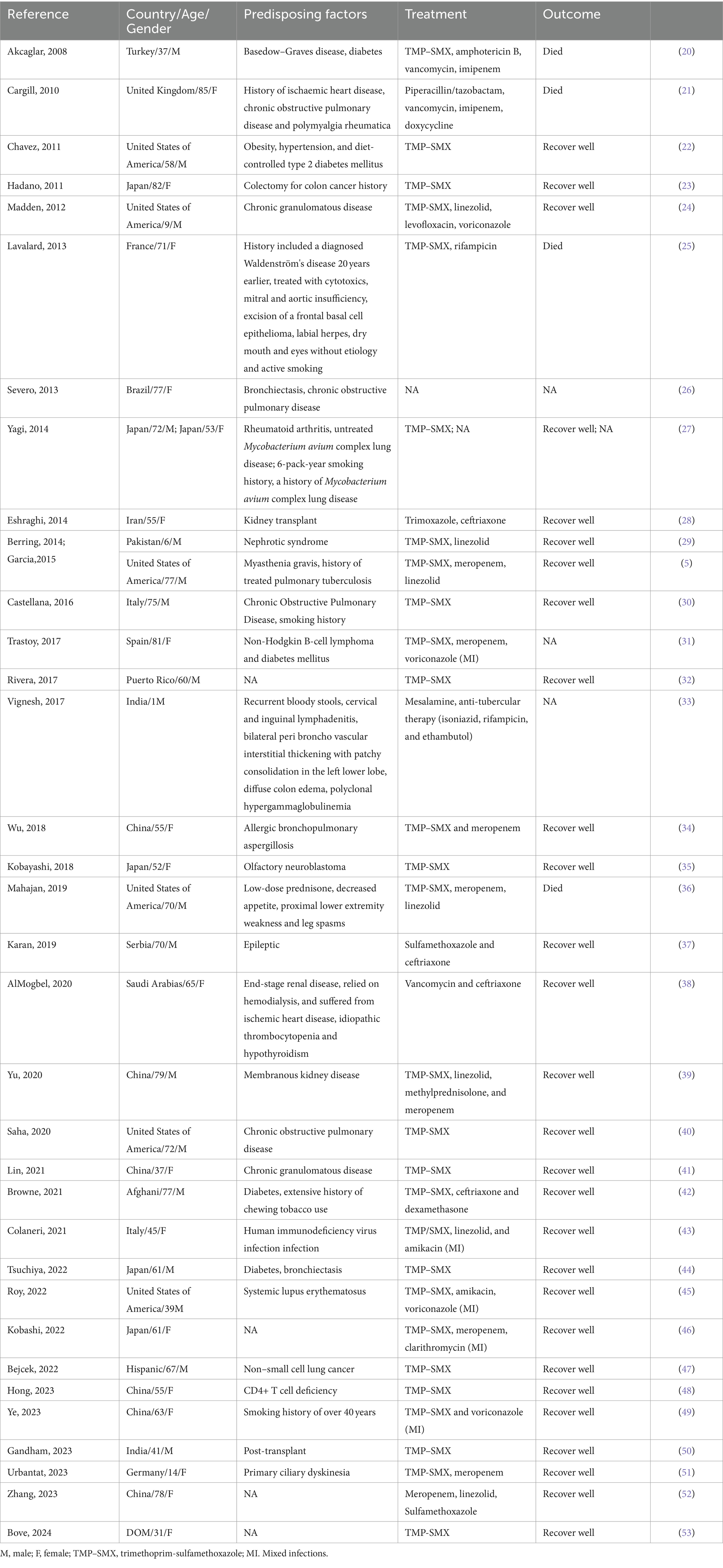

Nocardiosis has three primary forms: primary cutaneous infection, pulmonary infection, and disseminated infection (1, 11). It can also present as central nervous system infections, eye infections, osteomyelitis, and septic arthritis (7). Nocardia infections are commonly seen in immunocompromised hosts undergoing immunosuppressive therapy, such as in cases of prolonged corticosteroid use, malignancies, organ transplants, and HIV. They can also occur in non-immunocompromised hosts, primarily those with structural lung diseases like cystic fibrosis and bronchiectasis (2). We have searched for case reports and case series of N. cyriacigeorgica pulmonary infection during 2010-2024 in PubMed using the key words “(pulmonary) AND (Nocardia cyriacigeorgica).” Our search yielded 35 case reports that are summarized in Table 1. The total number of patients was 36, with an equal distribution of 18 males and 18 females (50%). Among them, 27 patients (75%) were over the age of 50. Nocardia pulmonary infections are commonly seen in immunosuppressed patients and those with underlying pulmonary conditions. Our statistics revealed that 9 patients (25%) had underlying pulmonary diseases, and 21 patients (58%) were immunosuppressed. Among the immunosuppressed, 6 patients (17%) had a history of cancer, and 5 patients (14%) had autoimmune diseases. Moreover, we found that 5 patients (14%) had diabetes, and 5 patients (14%) were smokers. Regarding treatment, a significant number of patients, 28 (78%), were treated with TMP-SMX, and 28 patients (78%) showed a good recovery from their Nocardial lung infection symptoms.

Table 1. Case reports and case series of N. cyriacigeorgica pulmonary infection during 2010-2024 in PubMed.

On the basis of typical clinical manifestations such as fluctuating muscle weakness, diagnosis can be made by meeting any of the following three criteria: pharmacological examinations, electrophysiological characteristics, and serum anti-acetylcholinesterase receptor or other antibody detection. The clinical manifestations and pulmonary imaging of pulmonary nocardiosis lack specificity, posing challenges for early diagnosis. In the present case, the patient's sputum smear exhibited morphological features highly suggestive of Nocardia infection under the microscope. Combined with the slow growth characteristics of Nocardia species, it was cultured successfully through extending the incubation period. Therefore, for slow-growing bacteria like Nocardia, direct smear staining microscopy and prolonged incubation time are crucial.

Currently, the treatment of MG primarily revolves around cholinesterase inhibitors, glucocorticoids, immunosuppressants, intravenous immunoglobulin, plasmapheresis, and thymectomy (12). Many studies have indicated that some Chinese medical approaches demonstrate promising outcomes in managing MG. Integrating Chinese and western medical practices can reduce the recurrence rate of the disease, minimize adverse reactions and complications, as well as modulate the immune function (13–16). The relative severity of MG in patients is reflected by the absolute score of clinical evaluation, which assesses the degree of muscle weakness and fatigue without necessitating any instrumentation. Scoring ranges from 0 to 60 points, with higher scores indicating more severe symptoms. The approach utilized in this case involved integrating both traditional Chinese medicine and western medicine to treat severe MG. Upon admission, the absolute score was 31, which significantly decreased to 6 following treatment, indicating remarkable therapeutic efficacy. TMP–SMX is the preferred treatment for nocardiosis, with monotherapy often used for nonsevere cases. Empiric multidrug therapy (such as carbapenems, TMP–SMX, amikacin, linezolid, or parenteral cephalosporins) is recommended for severe pulmonary infections, disseminated infections, and central nervous system infections (17, 18). Sulfonamide–carbapenem combination therapy is used empirically for nocardiosis, but all Nocardia isolates should ideally be identified to the species level and subjected to susceptibility testing to guide optimal treatment. Patients with localized pulmonary infections should receive treatment for >6 months, while those with complicated or disseminated diseases should undergo antibacterial therapy for >9 months (18, 19). The present case utilized the TMP–SMX for anti-infective therapy. The significant decrease in inflammatory markers and improvement in clinical symptoms before and after treatment suggested a pronounced therapeutic effect. Based on the comprehensive assessment, the clinical symptoms of MG and pulmonary Nocardia infection improved, and reached the criteria for clinical cure. Therefore, the patient was approved for discharge. Until now, there has been no recurrence of the Nocardia infection in the lungs.

Conclusion

To our knowledge, cases of coexisting MG and Nocardia infection are relatively rare. This present case represents the second instance, which was aimed at further elucidating the relationship between MG and pulmonary Nocardia infection by adding another clinical example. It underscores the heightened risk of developing pulmonary Nocardiosis following the use of hormone and immunosuppressive agents in MG patients. Clinicians should be cognizant of this and consider the possibility of Nocardia infection when conventional empirical treatments fail, thereby facilitating timely communication with microbiology laboratories to appropriately extend culture duration and prevent misdiagnosis.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics statement

Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article.

Author contributions

HZ: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. JY: Conceptualization, Writing – original draft. CL: Methodology, Writing – original draft. SL: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. JG: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. ND: Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. YZ: Writing – original draft, Data curation. JH: Data curation, Writing – original draft. MS: Data curation, Writing – original draft. YG: Writing – review & editing. WG: Writing – review & editing. ZZ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing. LZ: Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was fund by research project of Hebei Provincial Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine (No. 2024143).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Brown-Elliott, BA, Brown, JM, Conville, PS, and Wallace, RJ Jr. Clinical and laboratory features of the Nocardia spp. based on current molecular taxonomy. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2006) 19:259–82. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.2.259-282.2006

2. Ambrosioni, J, Lew, D, and Garbino, J. Nocardiosis: updated clinical review and experience at a tertiary center. Infection. (2010) 38:89–97. doi: 10.1007/s15010-009-9193-9

3. Martínez, R, Reyes, S, and Menéndez, R. Pulmonary nocardiosis: risk factors, clinical features, diagnosis and prognosis. Curr Opin Pulm Med. (2008) 14:219–27. doi: 10.1097/MCP.0b013e3282f85dd3

4. Muralidhar Reddy, Y, Parida, S, Jaiswal, SK, and Murthy, JM. Nocardiosis-an uncommon infection in patients with myasthenia gravis: report of three cases and review of literature. BMJ Case Rep. (2020) 13:e237208. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-237208

5. Garcia, RR, Bhanot, N, and Min, Z. A mimic's imitator: a cavitary pneumonia in a myasthenic patient with history of tuberculosis. BMJ Case Rep. (2015) 2015:bcr2015210264. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2015-210264

6. Tang, YL, Ruan, Z, Su, Y, Guo, RJ, Gao, T, Liu, Y, et al. Clinical characteristics and prognosis of very late-onset myasthenia gravis in China. Neuromuscul Disord. (2023) 33:358–66. doi: 10.1016/j.nmd.2023.02.013

7. Traxler, RM, Bell, ME, Lasker, B, Headd, B, Shieh, WJ, and McQuiston, JR. Updated review on Nocardia species: 2006-2021. Clin Microbiol Rev. (2022) 35:e0002721. doi: 10.1128/cmr.00027-21

8. Neumann, B, Angstwurm, K, Mergenthaler, P, Kohler, S, Schönenberger, S, Bösel, J, et al. Myasthenic crisis demanding mechanical ventilation: a multicenter analysis of 250 cases. Neurology. (2020) 94:e299–313. doi: 10.1212/WNL.0000000000008688

9. Liu, Z, Lai, Y, Yao, S, Feng, H, Zou, J, Liu, W, et al. Clinical outcomes of Thymectomy in myasthenia gravis patients with a history of crisis. World J Surg. (2016) 40:2681–7. doi: 10.1007/s00268-016-3599-6

10. Misra, UK, Kalita, J, Singh, VK, and Kumar, S. A study of comorbidities in myasthenia gravis. Acta Neurol Belg. (2020) 120:59–64. doi: 10.1007/s13760-019-01102-w

11. Dumic, I, Brown, A, Magee, K, Elwasila, S, Kaljevic, M, Antic, M, et al. Primary lymphocutaneous Nocardia brasiliensis in an immunocompetent host: case report and literature review. Medicina (Kaunas, Lithuania). (2022) 58:488. doi: 10.3390/medicina58040488

12. Dalakas, MC. Immunotherapy in myasthenia gravis in the era of biologics. Nat Rev Neurol. (2019) 15:113–24. doi: 10.1038/s41582-018-0110-z.30573759

13. Aragonès, JM, Altimiras, J, Roura, P, Alonso, F, Bufill, E, Munmany, A, et al. Prevalence of myasthenia gravis in the Catalan county of Osona. Neurologia. (2017) 32:1–5. doi: 10.1016/j.nrl.2014.09.007

14. Melzer, N, Ruck, T, Fuhr, P, Gold, R, Hohlfeld, R, Marx, A, et al. Clinical features, pathogenesis, and treatment of myasthenia gravis: a supplement to the guidelines of the German neurological society. J Neurol. (2016) 263:1473–94. doi: 10.1007/s00415-016-8045-z

15. Park, SY, Lee, JY, Lim, NG, and Hong, YH. Incidence and prevalence of myasthenia gravis in Korea: a population-based study using the National Health Insurance Claims Database. J Clin Neurol. (2016) 12:340–4. doi: 10.3988/jcn.2016.12.3.340

16. Xie, R, Liu, L, Wang, R, and Huang, C. Traditional Chinese medicine for myasthenia gravis: study protocol for a network meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). (2020) 99:e21294. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000021294

17. Lafont, E, Conan, PL, Rodriguez-Nava, V, and Lebeaux, D. Invasive Nocardiosis: disease presentation, diagnosis and treatment - old questions, new answers? Infect Drug Resist. (2020) 13:4601–13. doi: 10.2147/IDR.S249761

18. Restrepo, A, and Clark, NM. Nocardia infections in solid organ transplantation: guidelines from the infectious diseases Community of Practice of the American Society of Transplantation. Clin Transpl. (2019) 33:e13509. doi: 10.1111/ctr.13509

19. Welsh, O, Vera-Cabrera, L, and Salinas-Carmona, MC. Current treatment for nocardia infections. Expert Opin Pharmacother. (2013) 14:2387–98. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.842553

20. Akcaglar, S, Yilmaz, E, Heper, Y, Alver, O, Akalin, H, Ener, B, et al. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica: pulmonary infection in a patient with Basedow-graves disease and a short review of reported cases. Int J Infect Dis. (2008) 12:335–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ijid.2007.06.014

21. Cargill, JS, Boyd, GJ, and Weightman, NC. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica: a case of endocarditis with disseminated soft-tissue infection. J Med Microbiol. (2010) 59:224–30. doi: 10.1099/jmm.0.011593-0

22. Chavez, TT, Fraser, SL, Kassop, D, Bowden, LP 3rd, and Skidmore, PJ. Disseminated nocardia cyriacigeorgica presenting as right lung abscess and skin nodule. Mil Med. (2011) 176:586–8. doi: 10.7205/MILMED-D-10-00346

23. Hadano, Y, Ohmagari, N, Suzuki, J, Kawamura, I, Okinaka, K, Kurai, H, et al. A case of pulmonary nocardiosis due to Nocardia cyriacigeorgica with prompt diagnosis by gram stain. Nihon Kokyuki Gakkai zasshi. (2011) 49:592–6.

24. Madden, JL, Schober, ME, Meyers, RL, Bratton, SL, Holland, SM, Hill, HR, et al. Successful use of extracorporeal membrane oxygenation for acute respiratory failure in a patient with chronic granulomatous disease. J Pediatr Surg. (2012) 47:E21–3. doi: 10.1016/j.jpedsurg.2011.12.029

25. Lavalard, E, Guillard, T, Baumard, S, Grillon, A, Brasme, L, Rodríguez-Nava, V, et al. Brain abscess due to Nocardia cyriacigeorgica simulating an ischemic stroke. Ann Biol Clin. (2013) 71:345–8. doi: 10.1684/abc.2013.0816

26. Severo, CB, Oliveira Fde, M, Hochhegger, B, and Severo, LC. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica intracavitary lung colonization: first report of an actinomycetic rather than fungal ball in bronchiectasis. BMJ Case Rep. (2013) 2013:bcr2012007900. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2012-007900

27. Yagi, K, Ishii, M, Namkoong, H, Asami, T, Fujiwara, H, Nishimura, T, et al. Pulmonary nocardiosis caused by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in patients with Mycobacterium avium complex lung disease: two case reports. BMC Infect Dis. (2014) 14:684. doi: 10.1186/s12879-014-0684-z

28. Eshraghi, SS, Heidarzadeh, S, Soodbakhsh, A, Pourmand, M, Ghasemi, A, GramiShoar, M, et al. Pulmonary nocardiosis associated with cerebral abscess successfully treated by co-trimoxazole: a case report. Folia Microbiol. (2014) 59:277–81. doi: 10.1007/s12223-013-0298-7

29. Berring, DC, and Nygaard, U. Lung cavities caused by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in an immunosuppressed boy. Ugeskr Laeger. (2014) 176:V01140077.

30. Castellana, G, Grimaldi, A, Castellana, M, Farina, C, and Castellana, G. Pulmonary nocardiosis in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: a new clinical challenge. Respir Med Case Rep. (2016) 18:14–21. doi: 10.1016/j.rmcr.2016.03.004

31. Trastoy, R, Manso, T, García, X, Barbeito, G, Navarro, D, Rascado, P, et al. Pulmonary co-infection due to Nocardia cyriacigeorgica and Aspergillus fumigatus. Rev espanola de quimioterapia. (2017) 30:123–6.

32. Rivera, K, Maldonado, J, Dones, A, Betancourt, M, Fernández, R, and Colón, M. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica threatening an immunocompetent host; a rare case of paramediastinal abscess. Oxf Med Case Rep. (2017):omx061. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omx061

33. Vignesh, P, Rawat, A, Kumar, A, Suri, D, Gupta, A, Lau, YL, et al. Chronic granulomatous disease due to neutrophil cytosolic factor (NCF2) gene mutations in three unrelated families. J Clin Immunol. (2017) 37:109–12. doi: 10.1007/s10875-016-0366-2

34. Wu, J, Wu, Y, and Zhu, Z. Pulmonary infection caused by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in a patient with allergic bronchopulmonary aspergillosis: a case report. Medicine. (2018) 97:e13023. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000013023

35. Kobayashi, K, Asakura, T, Ishii, M, Ueda, S, Irie, H, Ozawa, H, et al. Pulmonary nocardiosis mimicking small cell lung cancer in ectopic ACTH syndrome associated with transformation of olfactory neuroblastoma: a case report. BMC Pulm Med. (2018) 18:142. doi: 10.1186/s12890-018-0710-9

36. Mahajan, KR. Disseminated nocardiosis with cerebral and subcutaneous lesions on low-dose prednisone. Pract Neurol. (2019) 19:62–3. doi: 10.1136/practneurol-2018-002038

37. Karan, M, Vučković, N, Vuleković, P, Rotim, A, Lasica, N, and Rasulić, L. Nocardial brain abscess mimicking lung cancer metastasis in immunocompetent patient with pulmonary nocardiasis: a case report. Acta Clin Croat. (2019) 58:540–5. doi: 10.20471/acc.2019.58.03.20

38. AlMogbel, M, AlBolbol, M, Elkhizzi, N, AlAjlan, H, Hays, JP, and Khan, MA. Rapid identification of Nocardia cyriacigeorgica from a brain abscess patient using MALDI-TOF-MS. Oxf Med Case Rep. (2020):omaa088. doi: 10.1093/omcr/omaa088

39. Yu, MH, Wu, XX, Chen, CL, Tang, SJ, Jin, JD, Zhong, CL, et al. Disseminated Nocardia infection with a lesion occupying the intracranial space complicated with coma: a case report. BMC Infect Dis. (2020) 20:856. doi: 10.1186/s12879-020-05569-4

40. Saha, BK, and Chong, WHH. Trimethoprim-induced hyponatremia mimicking SIADH in a patient with pulmonary nocardiosis: use of point-of-care ultrasound in apparent euvolemic hypotonic hyponatremia. BMJ Case Rep. (2020):13. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2020-235558

41. Lin, J, Wu, XM, and Peng, MF. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica infection in a patient with pulmonary sequestration: a case report. World J Clin Cases. (2021) 9:2367–72. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i10.2367

42. Browne, WD, Lieberson, RE, and Kabbesh, MJ. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica brain and lung abscesses in 77-year-old man with diabetes. Cureus. (2021) 13:e19373. doi: 10.7759/cureus.19373

43. Colaneri, M, Lupi, M, Sachs, M, Ludovisi, S, Di Matteo, A, Pagnucco, L, et al. A challenging case of SARS-CoV-2-AIDS and Nocardiosis coinfection from the SMatteo COvid19 REgistry (SMACORE). New Microbiol. (2021) 44:129–34.

44. Tsuchiya, Y, Nakamura, M, Oguri, T, Taniyama, D, and Sasada, S. A case of asymptomatic pulmonary Nocardia cyriacigeorgica infection with mild diabetes mellitus. Cureus. (2022) 14:e24023. doi: 10.7759/cureus.24023

45. Roy, M, Lin, RC, and Farrell, JJ. Case of coexisting Nocardia cyriacigeorgica and Aspergillus fumigatus lung infection with metastatic disease of the central nervous system. BMJ Case Rep. (2022):15. doi: 10.1136/bcr-2021-248381

46. Kobashi, Y, Yoshioka, D, Kato, S, and Oga, T. Pneumococcal pneumonia co-infection with Mycobacterium avium and Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in an immunocompetent patient. Int Med. (2022) 61:1285–90. doi: 10.2169/internalmedicine.6895-20

47. Bejcek, A, Owens, J, Marella, A, and George, A. Multiple rim-enhancing brain lesions and pulmonary cavitary nodules as the presentation of Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in a patient with non-small cell lung cancer. Proc (Baylor Univ Med Cent). (2022) 35:555–6. doi: 10.1080/08998280.2022.2058831

48. Hong, X, Ji, YQ, Chen, MY, Gou, XY, and Ge, YM. Nocardia cyriacigeorgica infection in a patient with repeated fever and CD4(+) T cell deficiency: a case report. World J Clin Cases. (2023) 11:1175–81. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v11.i5.1175

49. Ye, J, Li, Y, Hao, J, Song, M, Guo, Y, Gao, W, et al. Rare occurrence of pulmonary coinfection involving Aspergillus fumigatus and Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in immunocompetent patients based on NGS: a case report and literature review. Medicine. (2023) 102:e36692. doi: 10.1097/MD.0000000000036692

50. Gandham, N, Kannuri, S, Gupta, A, Mukhida, S, Das, N, and Mirza, S. A post-transplant infection by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica. Access Microbiol. (2023):5. doi: 10.1099/acmi.0.000569.v3

51. Urbantat, RM, Pioch, CO, Ziegahn, N, Stegemann, MS, Stahl, M, Mall, MA, et al. Pleuropneumonia caused by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica in a 14-year-old girl with primary ciliary dyskinesia. Pediatr Pulmonol. (2023) 58:2656–8. doi: 10.1002/ppul.26536

52. Zhang, LZ, Shan, CT, Zhang, SZ, Pei, HY, and Wang, XW. Disseminated nocardiosis caused by Nocardia otitidiscaviarum in an immunocompetent host: a case report. Zhonghua jie he he hu xi za zhi. (2023) 46:1127–30. doi: 10.3760/cma.j.cn112147-20230516-00243

Keywords: Nocardia cyriacigeorgica , myasthenia gravis, pulmonary infection, trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole, immunosuppression

Citation: Zuo H, Ye J, Li C, Li S, Gu J, Dong N, Zhao Y, Hao J, Song M, Guo Y, Gao W, Zhao Z and Zhang L (2024) Myasthenia gravis complicated with pulmonary infection by Nocardia cyriacigeorgica: a case report and literature review. Front. Med. 11:1423895. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1423895

Edited by:

Uday Kishore, United Arab Emirates University, United Arab EmiratesReviewed by:

Jorge García García, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Albacete, SpainYanchang shang, Chinese PLA General Hospital, China

Haijian Zhou, National Institute for Communicable Disease Control and Prevention, China CDC, China

Copyright © 2024 Zuo, Ye, Li, Li, Gu, Dong, Zhao, Hao, Song, Guo, Gao, Zhao and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Zhenjun Zhao, enpqaG9zcGl0YWxAc2luYS5jb20=; Lijie Zhang, emhhbmdsaWppZUBoZWJtdS5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Huifen Zuo1†

Huifen Zuo1† Yumei Guo

Yumei Guo Lijie Zhang

Lijie Zhang