- Department of Hepatology, The Third Hospital of Zhenjiang Affiliated Jiangsu University, Zhenjiang, Jiangsu, China

Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is a rare but serious immune-mediated life-threatening skin and mucous membrane reaction that is mainly caused by drugs, infections, vaccines, and malignant tumors. A 74-year-old woman presented with a moderate fever of unknown cause, which was relieved after 2 days, but with weakness and decreased appetite. Red maculopapules appeared successively on the neck, trunk, and limbs, expanding gradually, forming herpes and fusion, containing a yellow turbidous liquid and rupturing to reveal a bright red erosive surface spreading around the eyes and mouth. The affected body surface area was >90%. The severity of illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis was 2 points. The drug eruption area and severity index score was 77. She was diagnosed with TEN caused by hepatitis A virus and treated with 160 mg/day methylprednisolone, 300 mg/day cyclosporine, and 20 g/day gammaglobulin. Her skin showed improvements after 3 days of treatment and returned to nearly normal after 1 month, and liver function was completely normal after 2 months.

Introduction

Stevens–Johnson syndrome (SJS) is an uncommon but severe immune-mediated skin disorder. Toxic epidermal necrolysis (TEN) is an exacerbated manifestation of SJS, affecting more than 30% of the total body surface area (1). Its main causes include drug use and infections. Drugs that cause TEN include non-steroidal anti-inflammatory, aromatic anti-epileptic, anti-gout, antibacterial drugs, biological agents, and proprietary Chinese medicines. The related pathogens are Mycoplasma spp. and herpes simplex viruses. Human herpes virus (HHV)-6 (1), Epstein–Barr virus (EBV) (2), Mycoplasma pneumoniae (3–5), and novel coronavirus infection (6, 7) are associated with the occurrence and progression of SJS/TEN. M. pneumoniae and novel coronaviruses can directly cause SJS/TEN. Although TEN caused by viral hepatitis is rare, we report a new case of TEN caused by the hepatitis A virus with severe liver function impairment.

Case presentation

A 74-year-old woman developed fever with a maximum temperature of 38.4°C. She did not presented the symptoms cough, runny nose, or sore throat, and was not treated with any drugs. Two days later, her body temperature returned to normal; however, she developed fatigue and nausea, and a maculopapular rash appeared on her face, neck, chest, and back without pain. On Day 3, the fatigue symptoms worsened, appetite remained poor, and erythema of the trunk and limbs continued to expand progressively. On Day 5, the rash increased gradually and became herpetic, merging gradually into the bulla with partial epidermal exfoliation and skin tearing. After dermatological consultation, the patient was admitted to the hospital for the treatment of TEN.

At the physical examination on admission, body temperature, pulse, blood pressure, and respiration was 37.4°C, 82 beats/min, 137/82 mmHg, 20 breaths/min, respectively; the breathing sound was clear in both lungs without dry and wet rales in the lower lungs and cardiac rhythm was regular with no pathological murmurs. The mental condition was slightly poor; the patient could answer questions correctly but was uncooperative with the physical examination. Dermatological examination revealed multiple erythematous lesions, maculopapules, bullosa of the trunk and limbs, erythema fused into pieces, positive Nishler’s sign, bullovesicular wall relaxation, and yellow turbidous fluid. The vulva, perianal fold area, and compressed parts of the large area of collapse revealed a bright red erosive surface with evident seepage. The skin around the eye and external ear canal were broken, conjunctiva was congested, and eye was slightly photophobic. The lips were covered with dark red crusting that was bleeding; however, the oral mucosa remained unaffected. The affected body surface area was >90%, severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis (SCORTEN) (8) was 2 (age > 40 years, 1 point; epidermal exudation area was >10% of the total surface area, 1 point), drug eruption area and severity index (DASI) (9) score was 77, and Zubrod–ECOG–WHO physical status score was 3.

Blood tests 6 days after the initial fever showed a white blood cell count of 12.9 × 109/L [reference value: (3.5–9.5) × 109/L], lymphocyte ratio of 0.42 (0.200–0.500), lymphocyte count of 4.9 × 109/L [(1.1–3.2) × 109/L], neutrophil ratio 0.694 (0.400–0.750), neutral granulocyte count of 7.9 × 109/L[(1.8–6.3) × 109/L], and eosinophil count of 0.23 × 109/L [(0.02–0.52) × 109/L]. The blood biochemistry was as follows: creatinine 77 μmol/L (59–104 μmol/L), urea 4.3 mmol/L (2.8–7.1 mmol/L), uric acid 344 μmol/L (89–420 μmol/L), and albumin 34.6 g/L (35.0–50.0 g/L). The patient was prescribed 160 mg/day methylprednisolone, 300 mg/day cyclosporine, 20 g/day gamma globulin, and external aureomycin eye cream twice daily for both eyes and face to prevent adhesion.

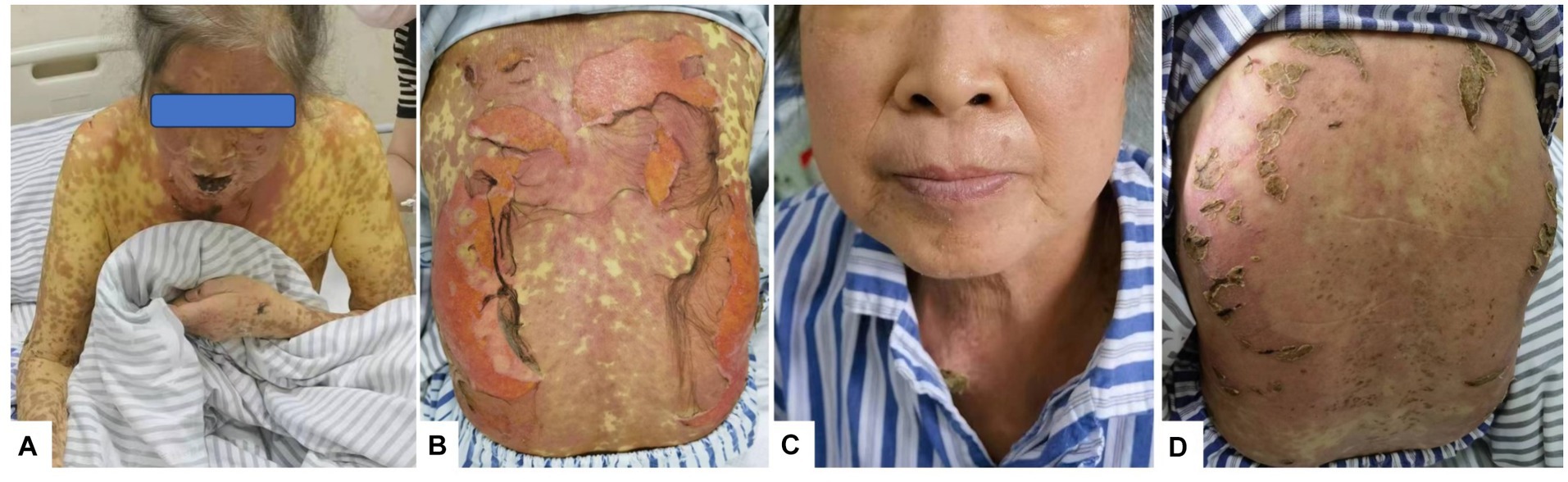

One week later, the skin lesions on the exposed parts of the patient’s face, torso, limbs, and other areas continued to improve, the skin in the areas of compression and folding was dry and healed gradually, but the pigmentation remained (Figure 1A); the DASI score was 42.8, no new maculopapules appeared on the limbs, and herpes absorption was observed. However, the back still had a large area of ulceration and exudation with pain (Figure 1B), fatigue improved, and appetite remained poor. Therefore, cyclosporine and immunoglobulin were discontinued and the methylprednisolone dose was reduced to 60 mg/day.

Figure 1. Rash changes. (A) On Day 10 of the disease course, the skin on the face and arms began to peel, forming scabs. (B) On Day 12 of the disease course, lesions on the back broke, exfoliated, and oozed. (C) On Day 26 of the disease course, facial skin appeared normal. (D) By Day 26, the skin on the back had healed and formed crusts.

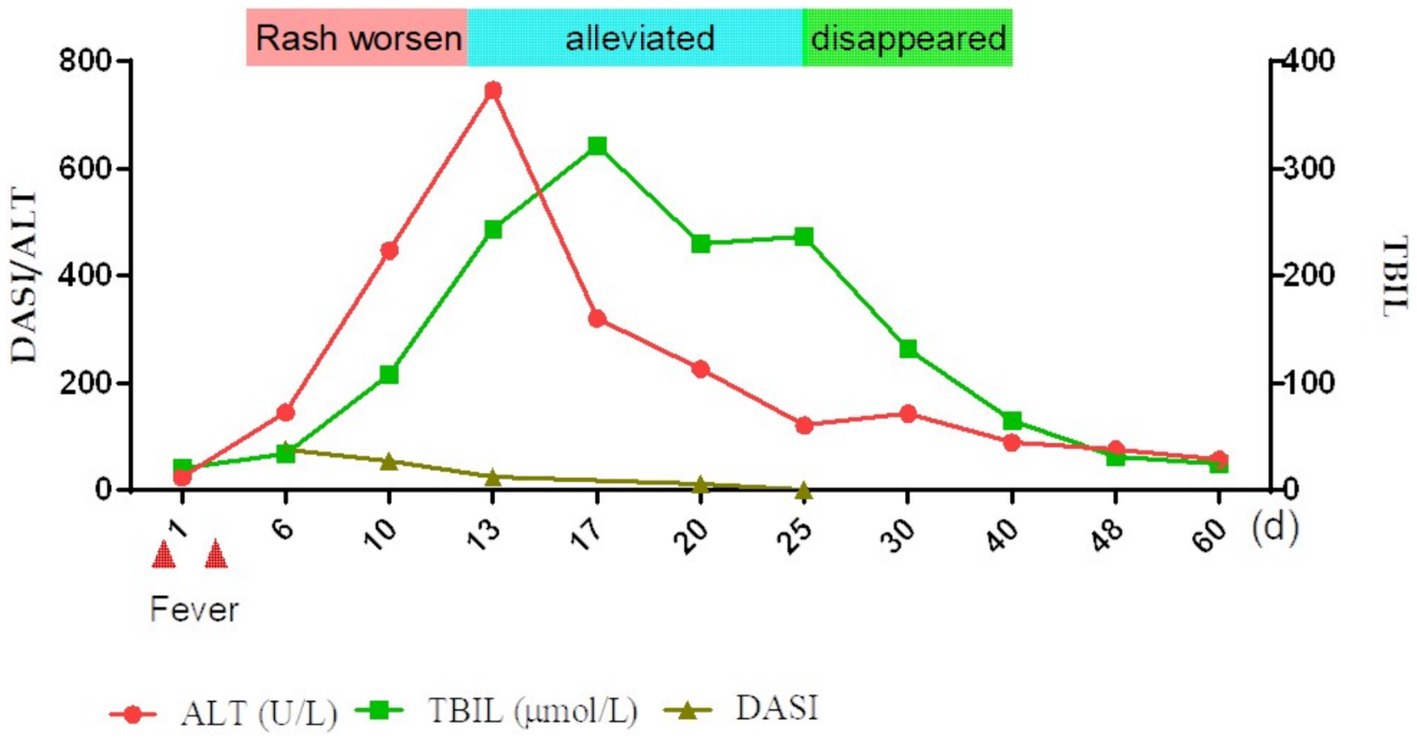

Nine days after the initial fever, liver function was significantly abnormal: total bilirubin (TBIL) 34.4μmo1/L, direct bilirubin (DBIL) 24.2 μmol/L, aspartate aminotransferase (AST) 146 U/L, alanine aminotransferase (ALT) 145 U/L, alkaline phosphatase (ALP) 209 U/L, glutamyl aminotransferase (GGT) 414 U/L, and prothrombin time 13 s. Prothrombin activity was 98% and the international normalized ratio (INR) was 1.12. The anti-HAV-IgM test results were strongly positive. An infectious disease physician diagnosed acute hepatitis A (AHA) and transferred the patient to the infectious disease department for treatment with adenosine, methionine, and ursodeoxycholic acid. The patient’s back was still ruptured and exudated, but other parts had improved gradually; however, the liver function indexes continued to deteriorate even a week later (TBIL 243.2 μmo1/L, ALT 746 U/L, ALP 674 U/L, GGT 1387 U/L). The skin had improved significantly on October 5 (Figures 1C,D). Therefore, the methylprednisolone treatment was discontinued. An overall disease progression flowchart is shown in Figure 2. Tests for Epstein–Barr virus (EBV), adenovirus, influenza A and B viruses, and SARS-CoV-2 were negative. Liver function indicators improved gradually and were completely normal after 2 months, with no alcohol consumption, history of other drug use or toxic exposure within 3 months before hospitalization, and history of allergy, B-E viral hepatitis markers, or anti-mitochondrial antibodies. Tests for antinuclear antibodies, anti-smooth muscle antibodies, anti-liver and anti-kidney microsomal antibodies, and other autoantibodies yielded negative results. The patient was diagnosed with TEN caused by hepatitis A virus (HAV).

Figure 2. Overall brief disease flowchart. TBIL, total bilirubin; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; DASI, severity index.

Discussion

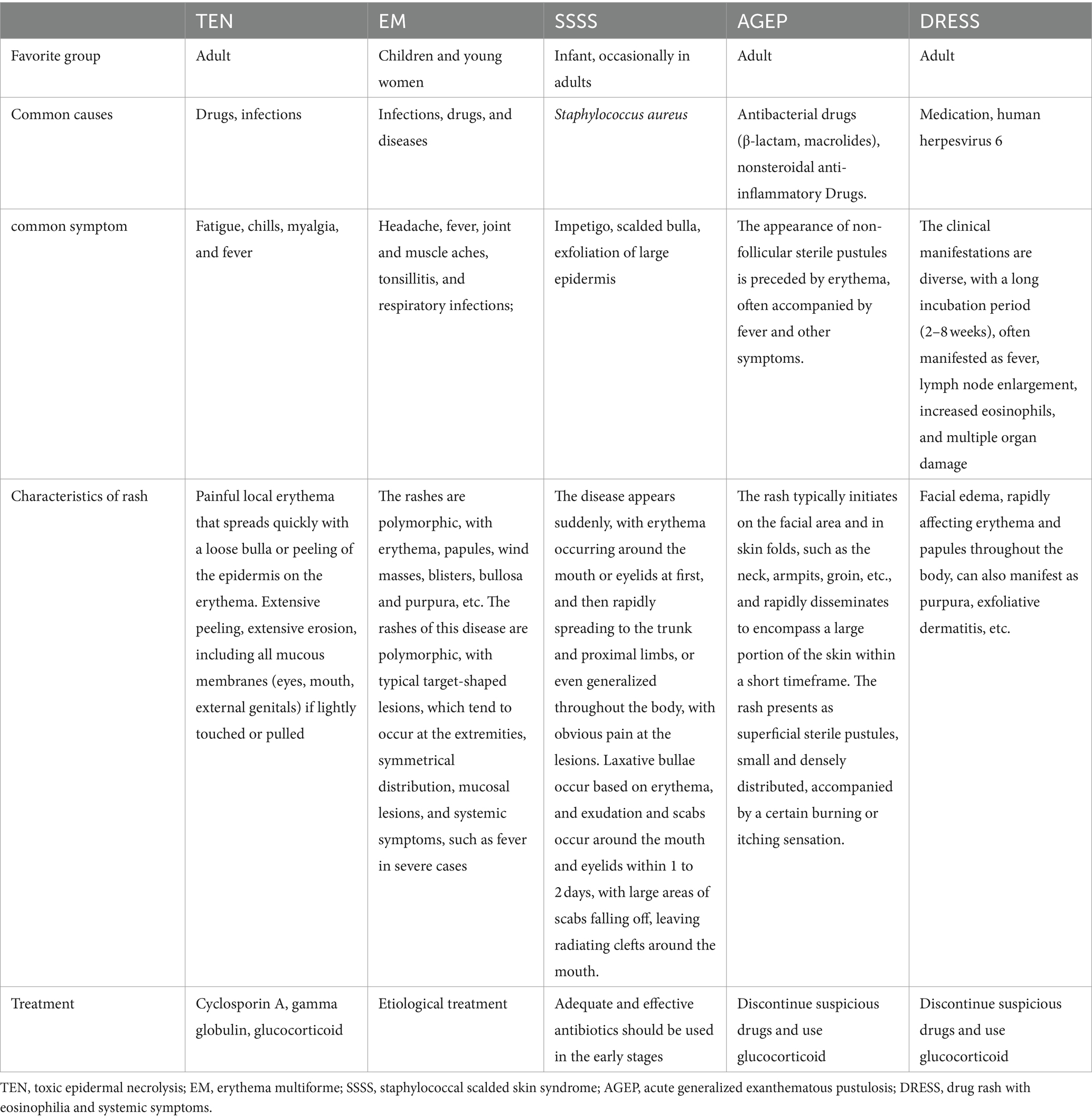

TEN is a serious, life-threatening cutaneous mucosal reaction that can occur at any age. The main causes are drug use and infections. The typical clinical manifestations include extensive skin/mucosal erythema, blisters, and severe epidermal necrolysis. This disease progresses rapidly. Multiple organs may be involved, with high mortality rate (14.8–48%) (10). TEN is a severe rash that must be differentiated from other types of rashes (Table 1). TEN pathogenesis involves T cell-mediated type IV hypersensitivity triggered by stimulants, such as drugs, with the cytokines associated with its pathogenesis serving as suitable biomarkers. Specific biomarkers, including galectin-7 (11) and receptor interaction protein 3 (12), and non-specific biomarkers, such as granolysin (13), chemokine ligand 27 (14), and soluble apoptosis-related factor ligand, contribute to the early diagnosis of TEN (15). However, no biomarkers with high specificity for pathogenic factors have been identified so far. In this patient, the dermatologist initially considered the cause to be drug-induced; however, a careful inquiry into the medical history showed no history of toxicant or drug exposure, and no suspected causative agents were found in the environment. Infection is considered another important cause of TEN; human herpesvirus (HHV)-6, EBV, M. pneumoniae, and novel coronavirus infections are associated with the development of TEN (16). The patient initially presented with a brief fever that resolved after 2 days. We considered this infection to have caused TEN. We observed that common respiratory viruses and bacteria were not the causative agents, and the positivity for anti-HAV-IgM was unexpectedly strong (three tests within 1 month). Positive anti-HAV-IgM is insufficient evidence to diagnose AHA; however, the patient had symptoms, such as fever, fatigue, and decreased appetite, accompanied by significant abnormalities in liver function; after ruling out other common causes of liver damage, the final diagnosis was AHA.

Hepatitis A, caused by HAV, is a self-limiting disease that is mainly transmitted via the fecal–oral route (17). China established a national self-funded vaccination program from 1992 to 2002 (18), including live attenuated and inactivated hepatitis A vaccines. The program effectively reduced the number of people susceptible to hepatitis A, and the incidence of hepatitis A decreased from 55.7 per 100,000 people in 1991 to less than 2 per 100,000 people in 2017. The hepatitis A epidemic in China has changed gradually from a high to a medium–low level (19). Hepatitis A infections are sporadic. In non-endemic areas, the diagnosis of hepatitis A is no longer dependent on the detection of HAV RNA, but on positive anti-HAV-IgM, clinical manifestations, and biochemical indicators of liver injury, such as abnormal ALT and TBIL levels.

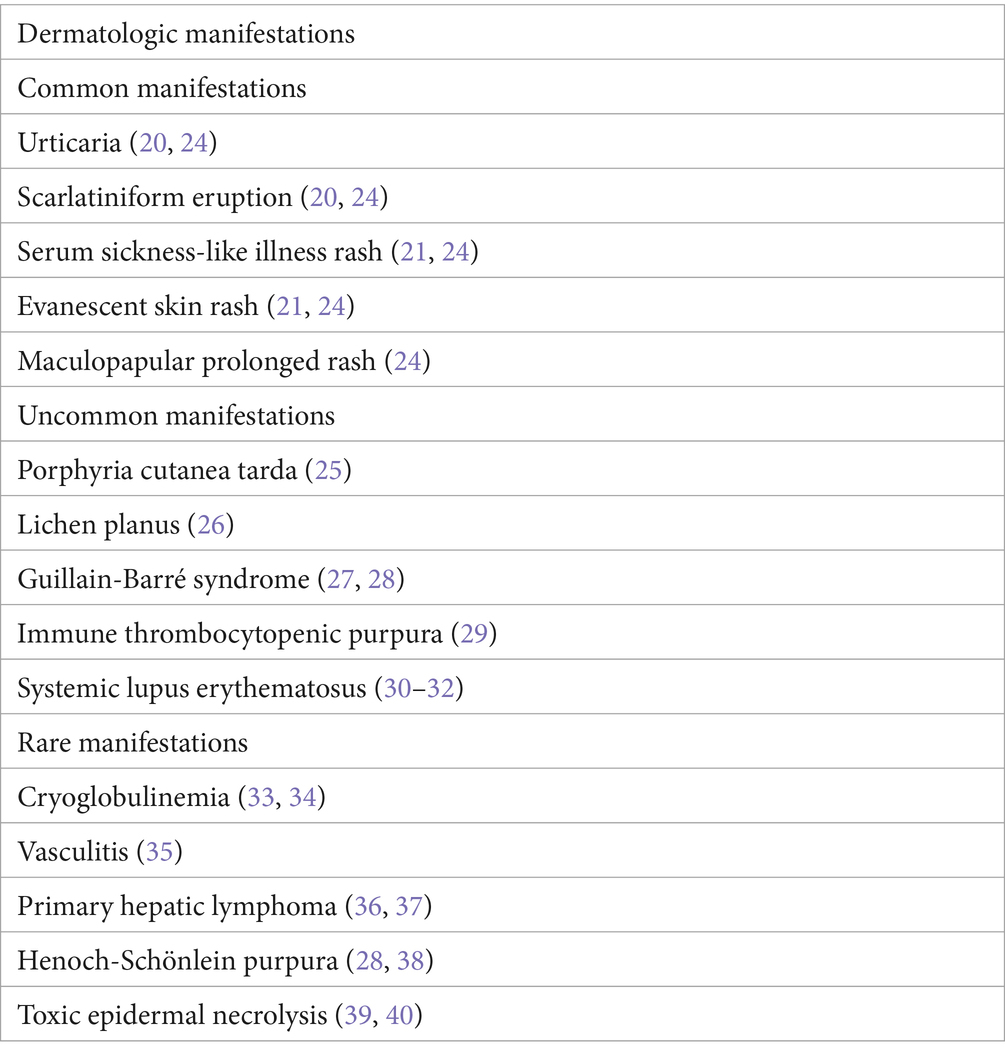

Skin manifestations of AHA are rare. A transient rash occurs before or simultaneously with an acute illness (20). The rashes observed are usually macular erythema, papular rash, and, less commonly, urticaria, purpura, or petechia (21). A few other cases of unusual rashes, including Gianotti–Crosti syndrome, Henoch–Schönlein purpura (22), and cutaneous vasculitis, have been reported (23) (Table 2). HAV-induced TEN caused by HAV is rare. In 1989, Werblowsky–Constantini (39) first reported the case of a 35-year-old man with fever for 3 weeks, 50% skin lesions, hyperbilirubinemia, and high ALP levels, similar to our patient’s liver function. Zang et al. (40) also reported a case of TEN related to HAV infection in a 38-year-old male with cirrhosis and preexisting liver failure. The patient developed skin lesions 15 days after the TBIL reached its peak, accompanied by fever with a maximum body temperature of 39.0°C, and sustained remission was achieved with intravenous corticosteroids.

It is a self-limiting disease that rarely causes liver failure. In our case, rapid deterioration of liver function occurred, especially with a progressive increase in total bilirubin and ALT levels, but no symptoms, such as high fatigue, ascites, or confusion, occurred. The prothrombin time and INR indices were normal, and acute liver failure could not be diagnosed. Multiple organ injuries often involve the liver and kidneys. Moreover, TEN can damage multiple organs, including the liver and kidneys. SJS/TEN can also be used to assess severity according to SCORTEN (8) and predict mortality. The score included the following seven factors, with one point for each risk factor: age > 40 years, complications of malignant tumor, exfoliation area > 10% of the total surface area, heart rate > 120 beats/min, serum urea nitrogen >10 mmol/L, venous blood glucose >14 mmol/L, and blood bicarbonate level < 20 mmol/L. The total score was 0–7 points, and the corresponding predicted mortality rates were 3.2% (0–1 point), 12.1% (2 points), 35.8% (3 points), 58.3% (4 points), and 90.0% (>5 points). The patient’s mean score was 2 points. Currently, no specific drug has been established for the treatment of SJS/TEN. However, supportive therapy can confer tangible benefits. Using systemic corticosteroids remains contentious, as initial observational studies have indicated markedly elevated rates of infection, including Candida sepsis and overall complications, leading to higher mortality (8) in patients receiving corticosteroid treatment. In contrast, recent investigations have proposed a survival advantage for patients treated with corticosteroids compared with those receiving supportive measures (41) alone.

A recent systematic review and meta-analysis (42) including 96 studies (3,248 patients) reported that the applied therapies included supportive or systemic immunomodulatory therapies, such as glucocorticoids, intravenous immunoglobulin, cyclosporine, plasma exchange, thalidomide, cyclophosphamide, hemoperfusion, tumor necrosis factor inhibitors, and granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. Glucocorticoids were associated with survival benefits in all three analyses but were statistically significant in only one analysis. Despite the small number of patients, cyclosporine was associated with promising significant results only in the feasibility analysis of the unstratified models (OR, 0.1; 95%CI, 0.0–0.4). No beneficial effects were observed with other therapies, including intravenous immunoglobulin.

This study had certain limitations. First, the patient was not tested for M. pneumoniae in the present study. Although patients do not develop respiratory symptoms, TEN is common. However, this possibility cannot be excluded. Second, no skin biopsy was performed, which is of great diagnostic significance. Third, HAV RNA was not detected in the present study. Finally, although the patient did not take any drugs, the possibility of drug-induced TEN could not be ruled out because trace amounts of drugs, especially antibiotics, may be present in certain foods.

In conclusion, we present a case of TEN caused by hepatitis A virus infection and severe liver function injury. Although drugs remain the primary pathogenic factors for TEN, in cases where physicians are unable to obtain a clear history of drug use and exposure to sensitizing substances, biological factors, including the uncommon pathogenic viruses and bacteria associated with TEN, must be considered. Furthermore, when there is evidence of organ damage, rare pathogenic factors, such as the liver injury observed in this case, must be investigated; this led us to believe that the hepatitis A virus was the causative agent. This case report also serves as a reminder to infectious disease specialists that hepatitis A virus infection may lead to rare severe skin reactions that can be effectively managed with early corticosteroid treatment, resulting in satisfactory recovery.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

The requirement of ethical approval was waived by The Third Hospital of Zhenjiang Affiliated Jiangsu University for the studies involving humans because The Third Hospital of Zhenjiang Affiliated Jiangsu University. The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study. Written informed consent was obtained from the individual(s) for the publication of any potentially identifiable images or data included in this article. Written informed consent was obtained from the participant/patient(s) for the publication of this case report.

Author contributions

YY: Investigation, Writing – original draft. QZ: Data curation, Investigation, Writing – review & editing. Y-WT: Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

1. Teraki, Y, Murota, H, and Izaki, S. Toxic epidermal necrolysis due to zonisamide associated with reactivation of human herpesvirus 6. Arch Dermatol. (2008) 144:232–5. doi: 10.1001/archdermatol.2007.48

2. Ishida, T, Kano, Y, Mizukawa, Y, and Shiohara, T. The dynamics of herpesvirus reactivations during and after severe drug eruptions: their relation to the clinical phenotype and therapeutic outcome. Allergy. (2014) 69:798–805. doi: 10.1111/all.12410

3. Yachoui, R, Kolasinski, SL, and Feinstein, DE. Mycoplasma pneumoniae with atypical Stevens-Johnson syndrome: a diagnostic challenge. Case Rep Infect Dis. (2013) 2013:457161. doi: 10.1155/2013/457161

4. Beheshti, R, and Cusack, B. Atypical Stevens-Johnson syndrome associated with Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Cureus. (2022) 14:e21825. doi: 10.7759/cureus.21825

5. Lofgren, D, and Lenkeit, C. Mycoplasma pneumoniae-induced rash and mucositis: a systematic review of the literature. Spartan Med Res J. (2021) 6:25284. doi: 10.51894/001c.25284

6. Pagh, P, and Rossau, AK. COVID-19 induced Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ugeskr Laeger. (2022) 184:V10210804

7. Grover, D, Singha, M, and Parikh, R. COVID-19: a curious abettor in the occurrence of Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Cureus. (2022) 14:e23562. doi: 10.7759/cureus.23562

8. Bastuji-Garin, S, Fouchard, N, Bertocchi, M, Roujeau, JC, Revuz, J, and Wolkenstein, P. SCORTEN: a severity-of-illness score for toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. (2000) 115:149–53. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1747.2000.00061.x

9. Schwartz, RA, McDonough, PH, and Lee, BW. Toxic epidermal necrolysis: part II. Prognosis, sequelae, diagnosis, differential diagnosis, prevention, and treatment. J Am Acad Dermatol. (2013) 69:187 e1-16. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2013.05.002

10. Hoffman, M, Chansky, PB, Bashyam, AR, Boettler, MA, Challa, N, Dominguez, A, et al. Long-term physical and psychological outcomes of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis. JAMA Dermatol. (2021) 157:712–5. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2021.1136

11. Hama, N, Nishimura, K, Hasegawa, A, Yuki, A, Kume, H, Adachi, J, et al. Galectin-7 as a potential biomarker of Stevens-Johnson syndrome/toxic epidermal necrolysis: identification by targeted proteomics using causative drug-exposed peripheral blood cells. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2019) 7:2894–2897.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.05.002

12. Hasegawa, A, Shinkuma, S, Hayashi, R, Hama, N, Watanabe, H, Kinoshita, M, et al. RIP3 as a diagnostic and severity marker for Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2020) 8:1768–1771.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.01.006

13. Abe, R, Yoshioka, N, Murata, J, Fujita, Y, and Shimizu, H. Granulysin as a marker for early diagnosis of the Stevens-Johnson syndrome. Ann Intern Med. (2009) 151:514–5. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-151-7-200910060-00016

14. Lavergne, M, Hernández-Castañeda, MA, Mantel, PY, Martinvalet, D, and Walch, M. Oxidative and non-oxidative antimicrobial activities of the granzymes. Front Immunol. (2021) 12:750512. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2021.750512

15. Chen, CB, Kuo, KL, Wang, CW, Lu, CW, Chung-Yee Hui, R, Lu, KL, et al. Detecting lesional granulysin levels for rapid diagnosis of cytotoxic t lymphocyte-mediated bullous skin disorders. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. (2021) 9:1327–1337.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.09.048

16. Pavlos, R, White, KD, Wanjalla, C, Mallal, SA, and Phillips, EJ. Severe delayed drug reactions: role of genetics and viral infections. Immunol Allergy Clin N Am. (2017) 37:785–815. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2017.07.007

17. Desai, AN, and Kim, AY. Management of Hepatitis a in 2020-2021. JAMA. (2020) 324:383–4. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4017

18. Zhang, L. Hepatitis A vaccination. Hum Vaccin Immunother. (2020) 16:1565–73. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2020.1769389

19. Li, YS, Zhang, BB, Zhang, X, Fan, S, Fei, LP, Yang, C, et al. Trend in the incidence of hepatitis A in mainland China from 2004 to 2017: a joinpoint regression analysis. BMC Infect Dis. (2022) 22:663. doi: 10.1186/s12879-022-07651-5

20. Bamber, M, Thomas, HC, Bannister, B, and Sherlock, S. Acute type a, B, and non-a, non-B hepatitis in a hospital population in London: clinical and epidemiological features. Gut. (1983) 24:561–4. doi: 10.1136/gut.24.6.561

21. Routenberg, JA, Dienstag, JL, Harrison, WO, Kilpatrick, ME, Hooper, RR, Chisari, FV, et al. Foodborne outbreak of hepatitis A: clinical and laboratory features of acute and protracted illness. Am J Med Sci. (1979) 278:123–38. doi: 10.1097/00000441-197909000-00003

22. Garty, BZ, Danon, YL, and Nitzan, M. Schoenlein-Henoch purpura associated with hepatitis A infection. Am J Dis Child. (1985) 139:547. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.1985.02140080017017

23. Inman, RD, Hodge, M, Johnston, ME, Wright, J, and Heathcote, J. Arthritis, vasculitis, and cryoglobulinemia associated with relapsing hepatitis A virus infection. Ann Intern Med. (1986) 105:700–3. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-105-5-700

24. Cozzani, E, Herzum, A, Burlando, M, and Parodi, A. Cutaneous manifestations of HAV, HBV, HCV. Ital J Dermatol Venerol. (2021) 156:5–12. doi: 10.23736/S2784-8671.19.06488-5

25. Abourached, A, Grimbert, S, and Beaugrand, M. Porphyria cutanea tarda appearing during prolonged viral hepatitis A. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. (1994) 18:661.

26. Rebora, A, and Rongioletti, F. Lichen planus and chronic active hepatitis. A retrospective survey. Acta Derm Venereol. (1984) 64:52–6. doi: 10.2340/00015555645256

27. Joshi, MS, Cherian, SS, Bhalla, S, and Chitambar, SD. Longer duration of viremia and unique amino acid substitutions in a hepatitis A virus strain [corrected] associated with Guillain-Barre syndrome (GBS). J Med Virol. (2010) 82:913–9. doi: 10.1002/jmv.21757

28. Chitambar, SD, Fadnis, RS, Joshi, MS, Habbu, A, and Bhatia, SG. Case report: hepatitis A preceding Guillain-Barre syndrome. J Med Virol. (2006) 78:1011–4. doi: 10.1002/jmv.20656

29. Urganci, N, Kilicaslan, O, Kalyoncu, D, and Yilmaz, S. Immune thrombocytopenic Purpura associated with hepatitis A infection in a five-year old boy: a case report. West Indian Med J. (2014) 63:536–8. doi: 10.7727/wimj.2013.176

30. Segev, A, Hadari, R, Zehavi, T, Schneider, M, Hershkoviz, R, and Mekori, YA. Lupus-like syndrome with submassive hepatic necrosis associated with hepatitis A. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. (2001) 16:112–4. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1746.2001.02314.x

31. Al-Dohayan, ND, Al-Batniji, F, Alotaibi, HA, and Elbaage, AT. Hepatitis-A infection-induced secondary antiphospholipid syndrome with neuro-ophthalmological manifestations. Cureus. (2021) 13:e20603. doi: 10.7759/cureus.20603

32. Chen, JL, Yu, X, Luo, R, and Liu, M. Severe digital ischemia coexists with thrombocytopenia in malignancy-associated antiphospholipid syndrome: a case report and review of literature. World J Clin Cases. (2021) 9:11457–66. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v9.i36.11457

33. Pappoppula, L, Zaidi, SMH, Iskander, PA, Iskander, A, Saeed, B, Elawad, A, et al. A rare manifestation of hepatitis A associated Cryoglobulinemia. Cureus. (2023) 15:e36948. doi: 10.7759/cureus.36948

34. Shalit, M, Wollner, S, and Levo, Y. Cryoglobulinemia in acute type-A hepatitis. Clin Exp Immunol. (1982) 47:613–6.

35. Ilan, Y, Hillman, M, Oren, R, Zlotogorski, A, and Shouval, D. Vasculitis and cryoglobulinemia associated with persisting cholestatic hepatitis A virus infection. Am J Gastroenterol. (1990) 85:586–7.

36. El Nouwar, R, and El Murr, T. Primary hepatic diffuse large B-cell lymphoma mimicking acute fulminant hepatitis: a case report and review of the literature. Eur J Case Rep Intern Med. (2018) 5:878. doi: 10.12890/2018_000878

37. Murakami, J, Fukushima, N, Ueno, H, Saito, T, Watanabe, T, Tanosaki, R, et al. Primary hepatic low-grade B-cell lymphoma of the mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue type: a case report and review of the literature. Int J Hematol. (2002) 75:85–90. doi: 10.1007/BF02981985

38. Chemli, J, Zouari, N, Belkadhi, A, Abroug, S, and Harbi, A. Hepatitis A infection and Henoch-Schonlein purpura: a rare association. Arch Pediatr. (2004) 11:1202–4. doi: 10.1016/j.arcped.2004.06.014

39. Werblowsky-Constantini, N, Livshin, R, Burstein, M, Zeligowski, A, and Tur-Kaspa, R. Toxic epidermal necrolysis associated with acute cholestatic viral hepatitis A. J Clin Gastroenterol. (1989) 11:691–3. doi: 10.1097/00004836-198912000-00020

40. Zang, X, Chen, S, Zhang, L, and Zhai, Y. Toxic epidermal necrolysis in hepatitis A infection with acute-on-chronic liver failure: case report and literature review. Front Med. (2022) 9:964062. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.964062

41. Sekula, P, Dunant, A, Mockenhaupt, M, Naldi, L, Bouwes Bavinck, JN, Halevy, S, et al. Comprehensive survival analysis of a cohort of patients with Stevens-Johnson syndrome and toxic epidermal necrolysis. J Invest Dermatol. (2013) 133:1197–204. doi: 10.1038/jid.2012.510

Keywords: toxic epidermal necrolysis, hepatitis A virus, treatments, skin, immune-mediated

Citation: Ye Y, Zhang Q and Tan Y-W (2024) Toxic epidermal necrolysis caused by viral hepatitis A: a case report and literature review. Front. Med. 11:1395236. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2024.1395236

Edited by:

Andreas Recke, University of Lübeck, GermanyReviewed by:

Indrashis Podder, College of Medicine & Sagore Dutta Hospital, IndiaYa-gang Zuo, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (CAMS), China

Copyright © 2024 Ye, Zhang and Tan. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: You-Wen Tan, dHl3OTE1QHNpbmEuY29t

Yun Ye

Yun Ye You-Wen Tan

You-Wen Tan