- 1Department of Anesthesia, Critical Care and Emergency, Fondazione Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico (IRCCS) Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy

- 2Department of Pathophysiology and Transplantation, University of Milan, Milan, Italy

- 3Department of Biomedical Surgical and Dental Sciences, University of Milan, Milan, Italy

- 4Division of Thoracic Surgery and Lung Transplantation, Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy

- 5Center for Preclinical Research, Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda, Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy

- 6Division of Pathology, Fondazione IRCCS Ca' Granda Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico, Milan, Italy

Background: Unilateral ligation of the pulmonary artery (UPAL) induces bilateral lung injury in pigs undergoing controlled mechanical ventilation. Possible mechanisms include redistribution of ventilation toward the non-ligated lung and hypoperfusion of the ligated lung. The addition of 5% CO2 to the inspiratory gas (FiCO2) prevents the injury, but it is not clear whether lung protection is a direct effect of CO2 inhalation or it is mediated by plasmatic hypercapnia. This study aims to compare the effects and mechanisms of FiCO2 vs. hypercapnia induced by low tidal volume ventilation or instrumental dead space.

Methods: Healthy pigs underwent left UPAL and were allocated for 48 h to the following: Volume-controlled ventilation (VCV) with VT 10 ml/kg (injury, n = 6); VCV plus 5% FiCO2 (FiCO2, n = 7); VCV with VT 6 ml/kg (low VT, n = 6); VCV plus additional circuit dead space (instrumental VD, n = 6). Histological score, regional compliance, wet-to-dry ratio, and inflammatory infiltrate were assessed to evaluate lung injury at the end of the study. To investigate the mechanisms of protection, we quantified the redistribution of ventilation to the non-ligated lung, as the ratio between the percentage of tidal volume to the right and to the left lung (VTRIGHT/LEFT), and the hypoperfusion of the ligated lung as the percentage of blood flow reaching the left lung (PerfusionLEFT).

Results: In the left ligated lung, injury was prevented only in the FiCO2 group, as indicated by lower histological score, higher regional compliance, lower wet-to-dry ratio and lower density of inflammatory cells compared to other groups. For the right lung, the histological score was lower both in the FiCO2 and in the low VT groups, but the other measures of injury showed lower intensity only in the FiCO2 group. VTRIGHT/LEFT was lower and PerfusionLEFT was higher in the FiCO2 group compared to other groups.

Conclusion: In a model of UPAL, inhaled CO2 but not hypercapnia grants bilateral lung protection. Mechanisms of protection include reduced overdistension of the non-ligated and increased perfusion of the ligated lung.

Introduction

Pathologic changes in lung perfusion in acute respiratory failure include a spectrum of functional and anatomical alterations ranging from impaired regional vaso-regulation to perfusion micro-thrombotic defects to pulmonary embolism (1, 2). These changes might contribute to ventilation-induced lung injury (VILI) through several mechanisms, including alveolar hypocapnia (3, 4), inhomogeneous distribution of ventilation (5–7), and regional hypoperfusion (8, 9). Notably, these mechanisms may be at play even when ventilation is delivered within protective limits. In the current clinical practice, prevention of VILI is based on the minimization of the injurious effects of tidal volume and pressure (10), the cornerstone of protective ventilation (11). On the contrary, prevention of VILI through correction of pathological alterations due to ventilation and perfusion inhomogeneity has received little attention.

A previous study conducted by our group showed that the addition of 5% CO2 to inspiratory gas prevents bilateral VILI in an experimental model of ligation of the left pulmonary artery (12). Mechanisms of protection included decreased inflammation in both lungs and more homogeneous distribution of ventilation, with reduced overdistension of the right lung.

Inhalation of 5% CO2 corrects alveolar hypocapnia in the ligated lung but also induces plasmatic hypercapnia. A few studies showed that plasmatic hypercapnia per se exerts anti-inflammatory actions and could prevent lung injury (13–15). Inhaled CO2 limits the deleterious consequences of alveolar hypocapnia in the ligated lung dampening pneumoconstriction (16) and surfactant depletion (4, 17). Thus, the question of the mechanism by which CO2 protects the lung (through a specific effect of the inhalation route or by plasmatic hypercapnia) still remains unanswered. Moreover, while the addition of CO2 to inspiratory gas has the unique potential of correcting alveolar hypocapnia, plasmatic hypercapnia can be obtained by clinically easier methods, such as low tidal volume ventilation or the addition of instrumental dead space.

We designed this experimental study to compare the lung-protective effects of inhalation of 5% CO2 vs. hypercapnia obtained either by low tidal volume or instrumental dead space in our model of unilateral pulmonary artery ligation. Our hypothesis was that the effects of inhaled CO2 might be more comprehensive in the presence of unilateral perfusion block, possibly leading to more effective protection of the lungs. We also explored the mechanisms of protection for each lung by monitoring regional ventilation and perfusion by electrical impedance tomography (EIT).

Materials and Methods

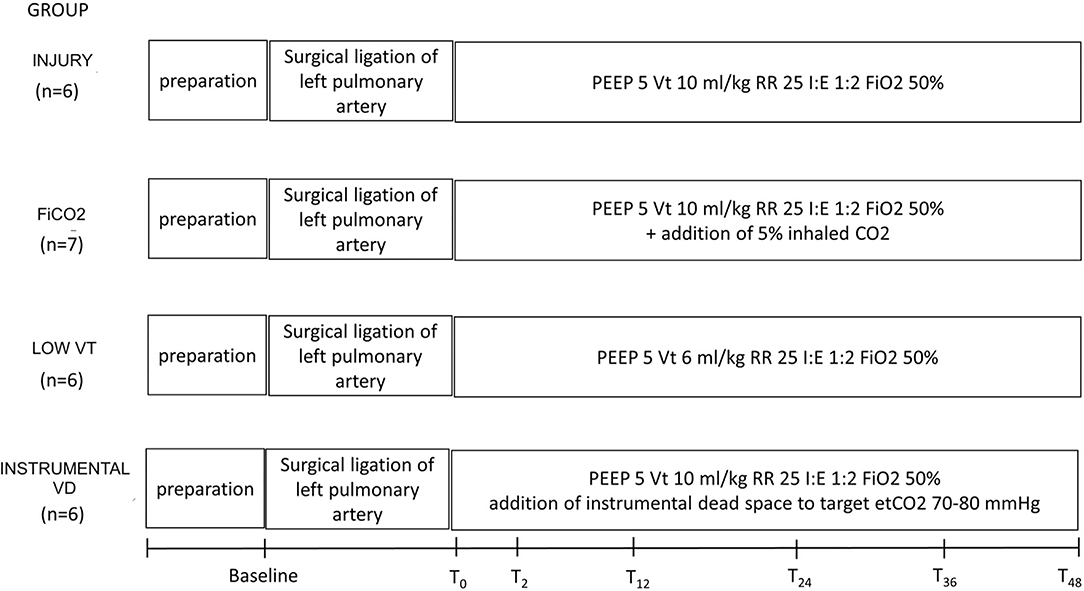

Figure 1 summarizes the study design. The study was approved by the Italian Ministry of Health (protocol No. 543/2018-PR) and conducted according to the European Directive 2010/63/EU on the protection of animals used for scientific purposes and Italian legislative decree 26/2014. Approval by the Institutional Animal Care Committee was obtained before starting the experiments.

Figure 1. Study design and timeline. Preparation corresponds to anesthesia and invasive monitoring, which took about 1 h. After baseline measurements, animals underwent surgical ligation of the left pulmonary artery. T0 to 48 corresponds to the study period, during which each group received a specific treatment, according to the study group. VT, tidal volume; PEEP, positive end-expiratory pressure in cm H2O; RR, respiratory rate in breaths/min.

Animal Preparation

Twenty-five healthy female pigs (36 ± 5 Kg) were anesthetized, intubated through surgical tracheostomy, and ventilated in the prone position using volume-controlled ventilation with tidal volume (VT) 10 ml/kg, respiratory rate (RR) 25 bpm, inspiratory/expiratory time ratio (I/E) 1:2, positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP) 5-cm H2O, and FIO2 0.5 (baseline settings).

General anesthesia and neuromuscular blockade were maintained by IV propofol 5–10 mg/kg/h, medetomidine 2.5–10.0 μg/kg/h, and pancuronium bromide 0.3–0.5 mg/kg/h for the whole study period.

After baseline measurements, surgical ligation of the left pulmonary artery was performed as previously described (12). Briefly, a left mini-thoracotomy was performed with the animal in the right lateral position and the main left pulmonary artery was isolated and progressively (5 minutes) occluded and then ligated.

Study Groups

Right after the ligation procedure, animals were turned prone and allocated to one of four study groups:

Left pulmonary artery ligation (injury, n = 6) with the following standard ventilation settings: VT 10 ml/kg, RR 25 bpm, I:E 1:2, PEEP 5 cmH2O, FiO2 0.5.

Left pulmonary artery ligation + inhaled CO2 (FiCO2, n = 7) with standard ventilation settings except for inspired gases switched to a mixture of 50% O2, 5% CO2, and 45% N2.

Left pulmonary artery ligation with low tidal volume (low VT, n = 6) with standard ventilation settings except for VT 6 ml/kg, as recommended by the American Thoracic Society's guidelines of protective ventilation in Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome (ARDS) patients (18).

Left pulmonary artery ligation with increased instrumental dead space (instrumental VD, n = 6) with standard ventilation settings plus additional tubing positioned after the circuit Y-targeted to end-tidal CO2 of 70–80 mmHg (similar to end-tidal CO2 levels obtained in the low VT group).

All animals were ventilated for 48 h.

Study Measurements

Data from respiratory mechanics, hemodynamics, blood gas analysis, and EIT were collected at baseline and after 2, 12, 24, 36, and 48 h from end of the ligation procedure (T2, T12, T24, T36, T48). The EIT data were recorded and stored for offline analysis by dedicated software (Dräger EIT Data Analysis Tool 6.3, Lübeck, Germany). From EIT ventilation maps we measured regional VT distribution for the right lung (VTRIGHT) and left lung (VTLEFT), the ratio between the two lungs (VTRIGHT/LEFT) and regional respiratory system compliance of each lung as the ratio between regional VT and driving pressure. The EIT perfusion maps were derived from offline analysis of the time–impedance curve obtained during the first pass of a 10-ml bolus of 5% saline solution during end-inspiratory occlusion, as previously described (19), and used to measure the percentage of perfusion to the left lung (PerfusionLEFT).

End of the Experiment

At T48, animals were euthanized, and lung tissue samples were collected for the following:

- Histology: the severity of regional lung injury in each lung was quantified by using a composite histological score, ranging from 0 (no injury) to 30 (severe), as previously described (12).

- Wet-to-dry calculation (12).

- Quantitative immunohistochemical analysis for measuring the percentage of cells positive for myeloperoxidase (MPO, i.e., neutrophils) and allograft inflammatory factor 1 (AIF-1, i.e., macrophages) (20).

- the Terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase dUTP nick end labeling (TUNEL) assay (ApopTag Plus Peroxidase In Situ Apoptosis Kit from Merck-Millipore) was employed to evaluate apoptosis on tissue samples of the left lungs from two representative animals for each study group as previously described (21).

Sample Size

The difference in histological scoring of the lungs of the four study groups was the primary endpoint of the study. The sample size was similar to the previous animal studies on the same topic (6, 13). However, we performed an exploratory power analysis and we hypothesized, based on our previous study (12), an effect size of 0.75; to obtain the power of 0.8 with alpha 0.05, the minimum sample size resulted in n = 6 per group.

Statistical Analysis

The data are shown as mean ± standard deviation or median [quartiles], as appropriate. The data measured at the end of the experiment were compared using one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test, followed by Dunnett or Dunn's test for multiple comparisons. Longitudinal data (physiological and EIT variables along the study time points) was analyzed using repeated measures two-way ANOVA or mixed-effect analysis, as appropriate, with time and group as a covariate. Statistical significance was defined by p < 0.05. Analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.

Additional details are available in the online supplement.

Results

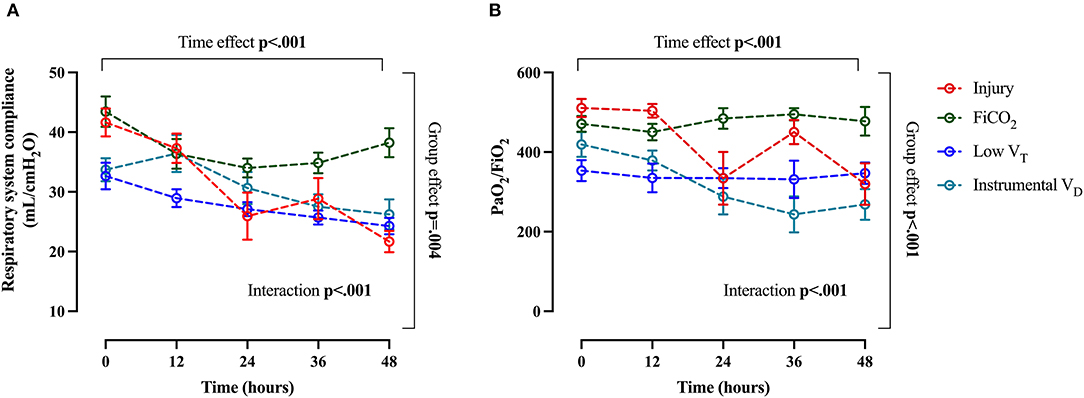

Alterations of Gas Exchange and Respiratory Mechanics

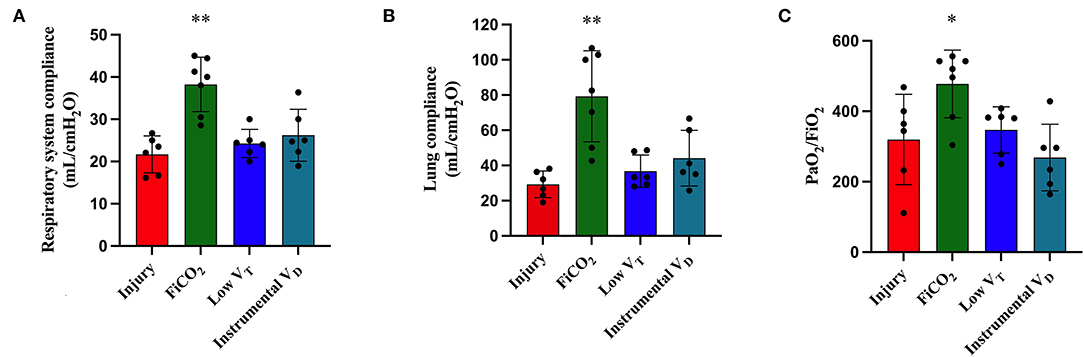

At T48, animals in the FiCO2 group had significantly higher respiratory system and lung compliance and PaO2/FiO2 ratio in comparison to all the other study groups. Indeed, the low VT and instrumental VD groups showed global signs of lung injury in terms of decreased compliance of the respiratory system due to decreased lung compliance and decreased PaO2/FiO2 ratio (Figures 2A–C).

Figure 2. Respiratory mechanics and gas exchanges at the end of the experiment. Respiratory system compliance (A), lung compliance (B), and PaO2/FiO2 ratio (C) were higher in the FiCO2 group compared to the other groups. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons are obtained with ordinary one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test for normally and non-normally distributed values, respectively, followed by Dunnett or Dunn's multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. Injury group.

Complete data on respiratory mechanics, blood gases, and hemodynamics at T48 in the four study groups are reported in Supplementary Table S1.

Protection of the Left Ligated Lung

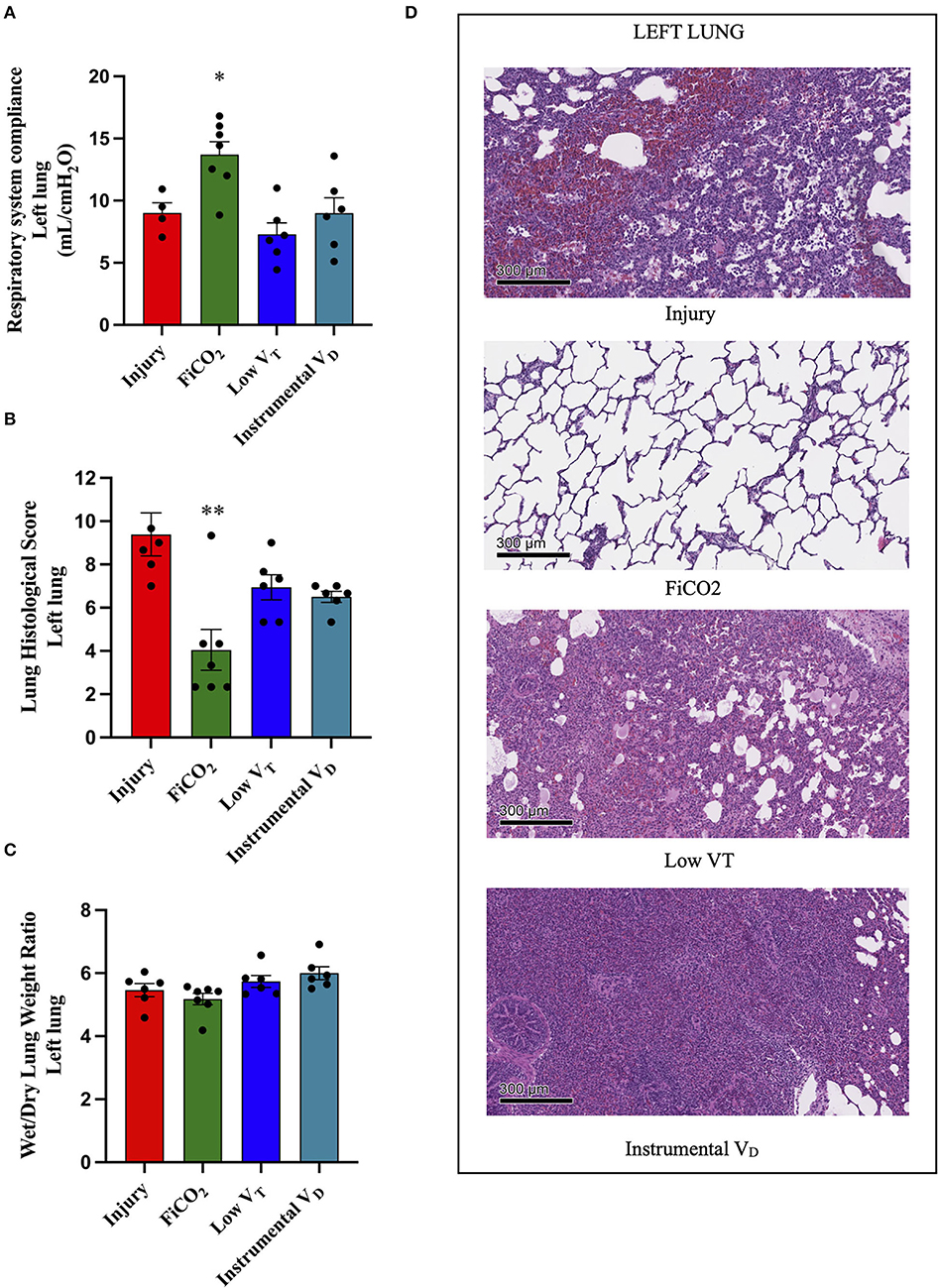

The signs of lung injury for the left ligated lung, including left-side respiratory system compliance measured by EIT, histological score, and wet-to dry ratio, were significantly different between the four study groups (p = 0.005, p = 0.0015, p = 0.026, respectively) (Figures 3A–C). The most efficient lung protection was found in the FiCO2 group, which showed higher regional compliance [14 (12 – 16) vs. 9 (7 – 11), p = 0.02] and lower histological score [3 (2 – 4) vs. 9 (8 – 11), p = 0.01] compared to the injury group.

Figure 3. Left lung injury. Left-side respiratory system compliance at the end of the experiment (A). Histological score of left lungs from each study group (B). Wet-to-dry of left lungs (C). Microscopic appearance of the lungs at the end of the experiment (D). Representative microphotographs of the left ligated lungs from the four study groups (H&E, original magnification 100 ×). Data are expressed as scatter dot plots with mean ± SEM. Comparisons are obtained with ordinary one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test for normally and non-normally distributed values, respectively, followed by Dunnett or Dunn's multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. Injury group.

The left lungs of animals in the FiCO2 group showed nearly normal histologic appearance, while injury was evident in all the other study groups. Hemorrhagic areas and inflammatory infiltrate composed mainly of macrophages characterized the injury group; vascular congestion, edema, and inflammatory infiltrate composed of macrophages and lymphocytes were prevalent in the low VT group; extensive consolidation by inflammatory infiltrate composed of macrophages, granulocytes, and lymphocytes described the instrumental VD group (Figure 3D).

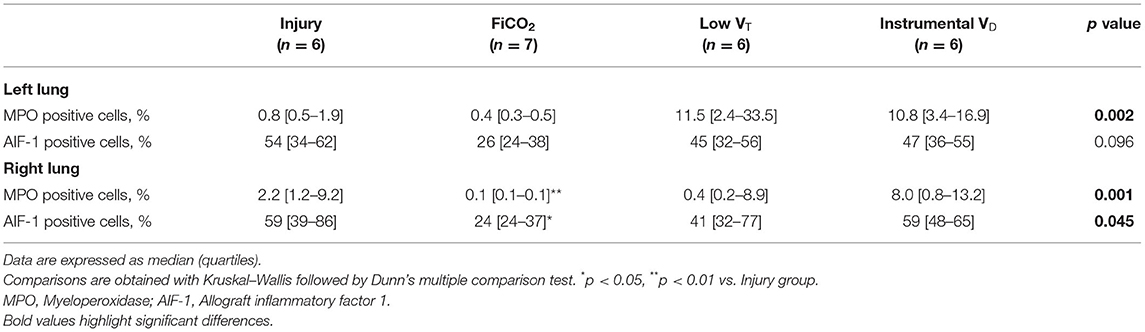

Immunohistochemical analyses showed significantly different densities of MPO-positive neutrophils in the left lungs of the four groups (p = 0.002). Interestingly, lungs from the FiCO2 showed the lowest values, while the low VT and instrumental VD groups had very high values (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1).

Table 1. Characterization by immunohistochemistry of the lung immune cell infiltrates in the different groups.

Left lungs from the FiCO2 group also showed the lowest presence of apoptotic cells as detected by the TUNEL assay (Supplementary Figure S2). Conversely, the lungs from the injury, low VT, and instrumental VD showed a high prevalence of apoptotic cells within the lung parenchyma (Supplementary Figure S2).

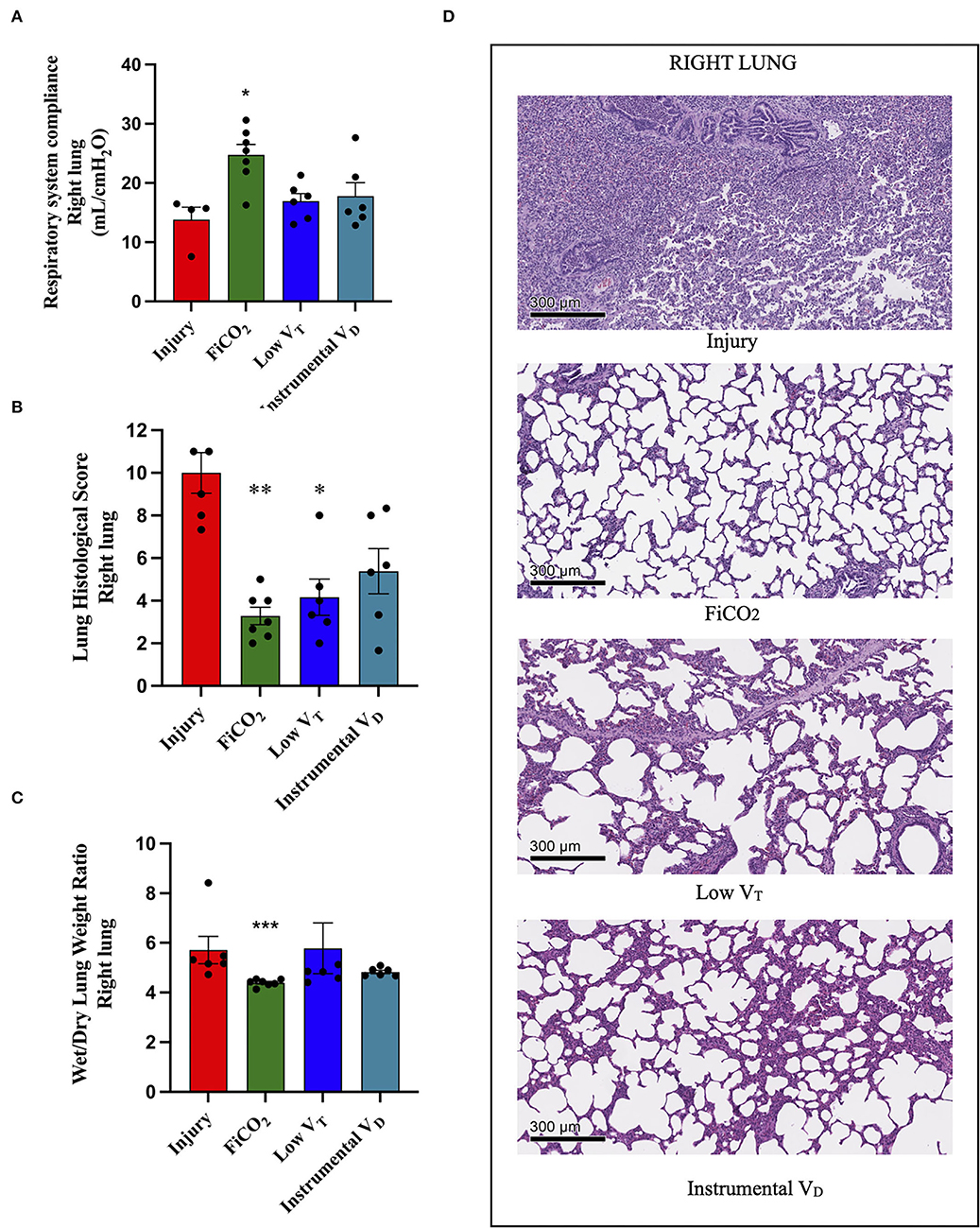

Protection of the Right Lung

The signs of injury in the right lung differed between groups (p = 0.021 for right-side compliance, p = 0.005 for histological score, p = 0.001 for wet-to-dry ratio). The right-side compliance was higher in the FiCO2 [25 (22 – 28)], while the other two hypercapnic groups did not differ from the injury group [17 (14 – 19) in low VT vs. 16 (14 – 23) in instrumental VD vs. 16 (10 – 16) in the injury] (Figure 4A). However, the histological score was lower both in the FiCO2 (3 ± 1) and in the low VT groups (4 ± 2) as compared to the injury (10 ± 2) (Figure 4B). Like the right-side compliance, the wet-to-dry ratio was lower only in the FiCO2 group [4.4 (4.3–4.5) vs 4.8 (4.5–6.6) in the low VT, 4.8 (4.7–5.0) in the instrumental VD, 5.2 (5.1–6.2) in the injury] (Figure 4C).

Figure 4. Right lung injury. Right-side respiratory system compliance at the end of the experiment (A). Histological score of right lungs from each study group (B). Wet-to-dry of right lungs (C). Microscopic appearance of the lungs at the end of the experiment (D). representative microphotographs of the right lungs from the four study groups (H&E, original magnification 100 ×). Data are expressed as scatter dot plots with mean ± SEM. Comparisons are obtained with ordinary one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test for normally and non-normally distributed values, respectively, followed by Dunnett or Dunn's multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01 vs. Injury group, and *** p < 0.001 vs. Injury group.

Again, except for the right lung of the FiCO2 group – which showed nearly normal histologic appearance – various patterns of injury were observed in all the study groups at histological microscopic analysis. The right lungs of the injury group presented almost complete consolidation with a dense inflammatory infiltrate, composed of granulocytes, histiocytes, and lymphocytes, while right lung injury in the low VT and instrumental VD consisted in a mild macrophagic infiltrate with focal areas of emphysema (Figure 4D).

Inflammation in the right lung measured by immunohistochemistry was decreased only in the FiCO2 group, in which MPO-positive neutrophils were almost absent, while the low VT and instrumental VD groups showed similar or even higher levels of neutrophils compared to the injury group (Table 1 and Supplementary Figure S1).

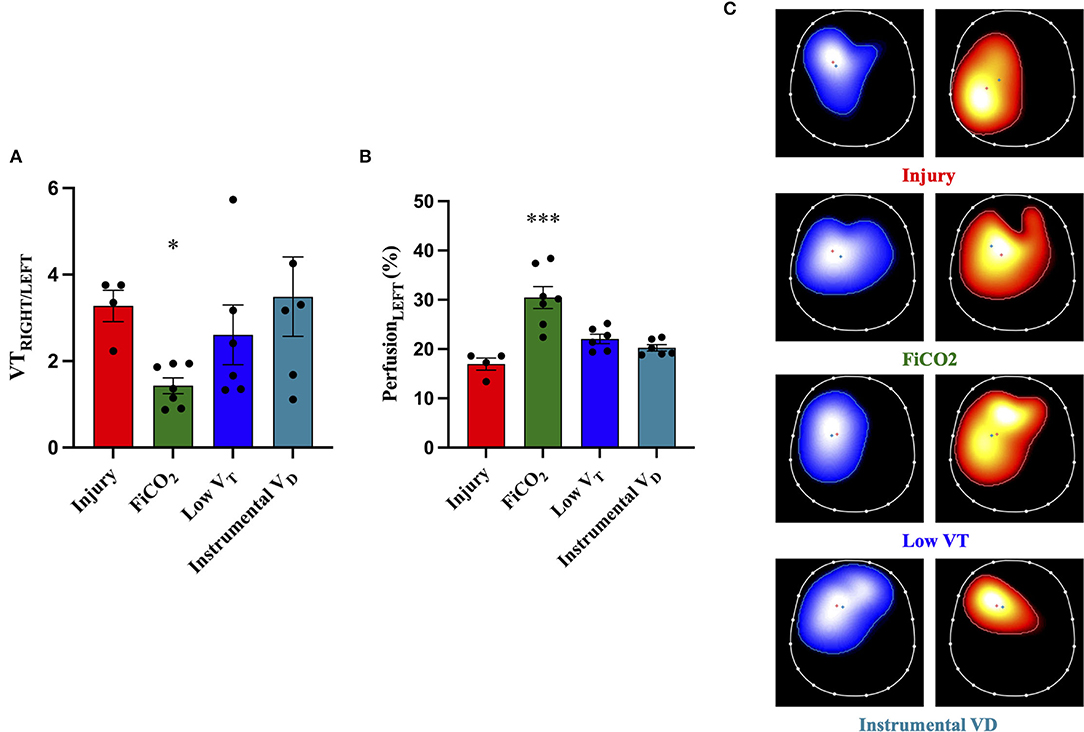

Distribution of Ventilation and Perfusion by EIT

The EIT analysis performed 2 h after pulmonary artery ligation (i.e., a time-point at which mechanisms of injury were already at play but lungs were not injured yet) showed that the ratio between the percentage of tidal volume to the right and the percentage of tidal volume to the left lung was significantly lower in the FiCO2 group as compared to all the other study groups (Figure 5A).

Figure 5. Distribution of ventilation and perfusion by EIT. The ratio between tidal volume distending the right and the left lung [VTRIGHT/LEFT, (A)] at 2 h after ligation of the left pulmonary artery shows significant imbalance in all the study groups, which was decreased only by FiCO2. The percentage of blood flow to the left lung [PerfusionLEFT, (B)] throughout the experiment (average between T2 and T48) was higher in the FiCO2 group compared to the other groups. Representative EIT images for ventilation (blue maps), perfusion (red maps), and distribution (C) showed increased ventilation and perfusion of the left lung in the FiCO2 group. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons are obtained with ordinary one-way ANOVA or Kruskal–Wallis test for normally and non-normally distributed values, respectively, followed by Dunnett or Dunn's multiple comparison test. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.001 vs. Injury group.

Regional perfusion measured by EIT throughout the study showed that the percentage of blood flow reaching the left ligated lung was higher in the group FiCO2 compared to the other groups (Figure 5B).

Representative EIT images showing the distribution of ventilation and perfusion in the four study groups are displayed in Figure 5C.

Baseline

Before the start of the experiment (i.e., at baseline, measured before the ligation procedure with standard ventilation settings), there were no differences between the animals allocated to the four groups in terms of respiratory mechanics, gas exchange, and hemodynamics (Supplementary Table S2).

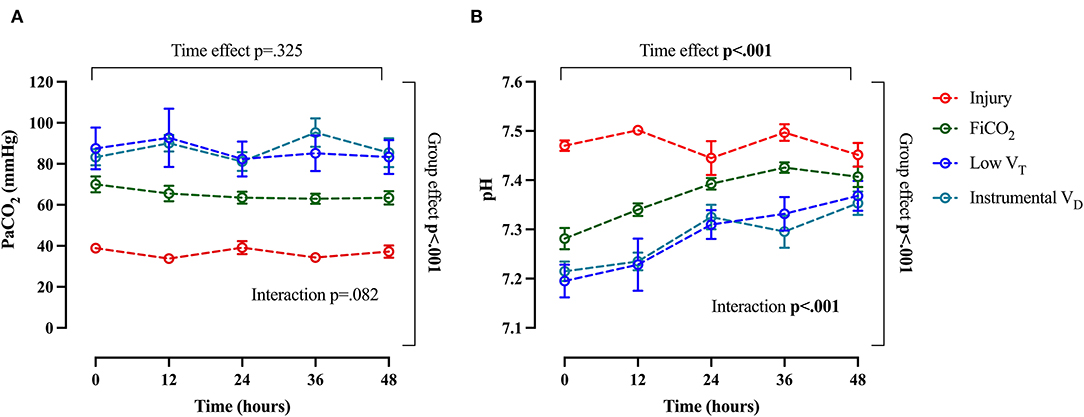

Trends of Physiological Variables Over Time

The course of arterial CO2 and arterial pH throughout the study are shown in Figures 6A,B. The evolution of injury through changes in respiratory system compliance and PaO2/FiO2 is shown in Figures 7A,B. The data collected for each variable at all time-points in the four study groups can be found in Supplementary Table S3 and confirm that the most differences appeared after 24 h.

Figure 6. Trend of arterial CO2 and arterial pH throughout the study. Arterial pCO2 (A) and pH (B). Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons are obtained with a two-way ANOVA test for normally distributed values followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test.

Figure 7. Main global markers of injury. Trend of respiratory system compliance (A) and PaO2/FiO2 (B) throughout the study. Data are expressed as mean ± SEM. Comparisons are obtained with two-way ANOVA test for normally distributed values followed by Dunnett's multiple comparisons test.

Discussion

The main findings of this study can be summarized as follows: The addition of 5% CO2 to inhaled gas confers full bilateral lung protection in experimental unilateral pulmonary artery ligation; hypercapnia is obtained by lowering the tidal volume and by increasing the instrumental dead space, instead, offers limited lung protection, if any, to the right perfused lung and fails to protect the left ligated lung. Mechanisms of lung protection by inhaled CO2 were confirmed in terms of reduced overdistension of the right lung and dampened bilateral lung inflammation. In this context, this study provides novel evidence of the additional role of increased regional perfusion reaching the left ligated lung (probably through the bronchial circulation) in preventing left lung injury.

This experimental study assessed the protection from VILI conferred by inhaled CO2 compared to hypercapnia induced by the low tidal volume and by the increased instrumental dead space in a model of unilateral pulmonary artery ligation. We confirmed that the protection of the left ligated lung is effectively achieved by addition of 5% CO2 to the inspired gas while the alternative methods used to induce hypercapnia were not effective. Our results confirm the mechanisms of injury for the left lung previously described as follows: Inflammation (12) and apoptosis triggered by alveolar hypocapnia (4), which could be effectively prevented by inhaled CO2. Interestingly, our results also showed that, in the left lung, plasmatic hypercapnia induced by the decreased tidal volume or the increased instrumental dead space did not prevent infiltration and activation of immune cells and did not prevent apoptosis. In contrast to adding inspired CO2, alveolar hypoventilation due to instrumental dead space might result in an uneven distribution of CO2 within the lungs, with a limited increase of CO2 content in the left lung due to the dilution with external gases and pulmonary artery perfusion block. A new finding is that inhalation of CO2, but not plasmatic hypercapnia obtained by the other two methods, increases blood flow to the left ligated lung. Our methods do not provide evidence for the source of this higher regional blood flow, but it is likely to derive from bronchial circulation (22). Indeed, bronchial perfusion increases in the presence of higher alveolar O2 and CO2 (23); both might have been obtained by inhaled CO2 through direct effect (for CO2) and higher regional ventilation of the left lung (for O2). Our observation suggests that the reduction of tissue hypoperfusion might be a novel mechanism underlying the protective effect of inhaled CO2 (8, 9, 24).

Concerning the right lung, protection was granted by addition of inhaled 5% CO2 – confirming the previous data (12) – but also by ventilation with low tidal volume. Plasmatic hypercapnia induced by the increased instrumental dead space, instead, was not effective. We have previously reported that hyperventilation and activation of inflammation are the key injurious mechanisms for the right non-ligated lung, which can be effectively prevented by inhaled CO2 (12). In the low VT group, reduced over-distension and plasmatic hypercapnia seemed to protect the right non-ligated lung. However, in our model, right lung protection by low VT was inferior to inhaled CO2, as suggested. However, in our model, lung protection conferred by the low tidal volume was inferior compared to the inhaled CO2, as suggested by higher regional markers of inflammation, lower right-side respiratory system compliance, and higher wet-to-dry ratio. A reason for partial right lung protection by reduced VT might be a lack of prevention of left ligated lung injury yielding organs cross-talk (25).

When we consider the global physiological consequences of lung injury in terms of impairment of oxygenation and respiratory mechanics, they once again confirm that only inhaled CO2 appears to confer effective protection from VILI in this model.

Experimental studies have demonstrated that therapeutic hypercapnia induced by inhaled CO2 is effective in attenuating lung injury in ARDS (15) and in protecting from VILI induced by high tidal volume ventilation (13, 14, 26). Regarding the role of hypercapnia induced by reduction of tidal volume (“permissive hypercapnia”), it has been difficult to separate the protective effect of hypercapnia per se from the established benefit due to the reduction of lung stress and strain (27). Clinical studies indicate that the permissive hypercapnia could improve clinical outcomes (28), but, at the same time, ARDS patients ventilated by a protective strategy developing severe hypercapnia are at higher risk of mortality (29). Experimental studies aimed at dissecting the protective effects of hypercapnia vs. those of low tidal volume have been scarce and led to conflicting results. Hypercapnia induced by reduced tidal volume and the respiratory rate has been shown to amplify inflammatory lung injury in experimental lipopolysaccharide-induced ARDS (30). On the contrary, ventilation with low tidal volumes and associated hypercapnia was proved protective in a model of surfactant depletion (31), although the protective effect seemed to depend mainly upon lower tidal volume (32). In contrast to adding inspired CO2, alveolar hypoventilation by low tidal volumes might result in an uneven distribution of CO2 within the lungs (33), and this could lead to failure to correct areas of alveolar hypocapnia. In conclusion, the reduced tidal volume ventilation with or without the permissive hypercapnia remains a cornerstone of ARDS treatment, but the evidence is growing on the potential role of inhaled CO2 as a complementary strategy leading to full lung protection.

This study has limitations. First, the results partially overlap with our previous work (12); however, we present alternative methods to obtain hypercapnia, as well as new data on regional lung perfusion and apoptosis, which increased our understanding of pathophysiological mechanisms. Second, we applied pragmatic methods to obtain plasmatic hypercapnia using a fixed value for low tidal volume and adding instrumental dead space targeted to a target CO2 level. Other methods might have led to different results; however, our methods reflected values normally used in clinical practice and increase potential clinical translation. Third, alveolar hypocapnia, which is a key mechanism of injury in our model, was not measured, so we can only hypothesize its role to explain the differences between groups. Finally, EIT is a technique with limitations, including imaging limited to a portion of the lung and the relative nature of the measures of regional ventilation and perfusion.

Conclusion

This study shows that inhaled CO2 allows more effective bilateral lung protection compared to plasmatic hypercapnia induced by low tidal volume and additional instrumental dead space in a model of left pulmonary artery ligation. Further studies are needed to understand whether a protective strategy combining low tidal volume and inhaled CO2 might be beneficial in patients with large perfusion defects (e.g., ARDS with high dead space fraction).

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Italian Ministry of Health (protocol n. 543/2018-PR).

Author Contributions

ES, AP, and TM conceived, planned, carried out the experiments, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript. GL, AD, FD, EG, GD, AC, GG, VF, OB, MB, and CL carried out the experiments and collected the results. VV processed experimental data. OB and MB helped in the implementation of the experiments. GL, VV, and SF collected and processed biological samples and analyzed the results. LR, SF, and SG provided critical feedback, helped shape the research, analysis, and manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

The work was funded by Ricerca Finalizzata 2016 from the Italian Ministry of Health, Rome, Italy to TM, project GR-2016-02362428 and Ricerca Corrente 2021 from Ospedale Maggiore Policlinico of Milan, Italy to AP.

Conflict of Interest

AP reports personal fess from Baxter, Maquet, Boehringer Ingelheim and Xenios outside the submitted work. TM reports personal fees from Drager, Fisher and Paykel, Hamilton and BBraun outside the submitted work.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher's Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2022.901809/full#supplementary-material

References

1. Zapol WM, Jones R. Vascular components of ARDS. Clinical pulmonary hemodynamics and morphology. Am Rev Respir Dis. (1987) 136:471–4. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm/136.2.471

2. Patel BV, Arachchillage DJ, Ridge CA, Bianchi P, Doyle JF, Garfield B, et al. Pulmonary angiopathy in severe COVID-19: physiologic, imaging, and hematologic observations. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2020) 202:690–9. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202004-1412OC

3. Laffey JG, Engelberts D, Kavanagh BP. Injurious effects of hypocapnic alkalosis in the isolated lung. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2000) 162:399–405. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.162.2.9911026

4. Kiefmann M, Tank S, Keller P, Bornchen C, Rinnenthal JL, Tritt MO, et al. IDH3 mediates apoptosis of alveolar epithelial cells type 2 due to mitochondrial Ca(2+) uptake during hypocapnia. Cell Death Dis. (2017) 8:e3005. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.403

5. Tsang JY, Lamm WJ, Swenson ER. Regional CO2 tension quantitatively mediates homeostatic redistribution of ventilation following acute pulmonary thromboembolism in pigs. J Appl Physiol (1985). (2009) 107:755–62. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00245.2009

6. Cambiaghi B, Vasques F, Morer O, Ritter C, Mauri T, Kunze-Szikszay N, et al. Effects of regional perfusion block in healthy and injured lungs. Intensive Care Med Exp. (2017) 5:46. doi: 10.1186/s40635-017-0161-2

7. Langer T, Castagna V, Brusatori S, Santini A, Mauri T, Zanella A, et al. Short-term physiologic consequences of regional pulmonary vascular occlusion in pigs. Anesthesiology. (2019) 131:336–43. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0000000000002735

8. Tojo K, Nagamine Y, Yazawa T, Mihara T, Baba Y, Ota S, et al. Atelectasis causes alveolar hypoxia-induced inflammation during uneven mechanical ventilation in rats. Intensive Care Med Exp. (2015) 3:56. doi: 10.1186/s40635-015-0056-z

9. Kawabata Y, Shimizu Y, Hoshi E, Ikeya T, Kurashima K, Takayanagi N. Acute ischaemic lung injury due to pulmonary vascular obstruction. Histopathology. (2016) 69:647–54. doi: 10.1111/his.12979

10. Gattinoni L, Protti A, Caironi P, Carlesso E. Ventilator-induced lung injury: the anatomical and physiological framework. Crit Care Med. (2010) 38:S539–548. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e3181f1fcf7

11. Henderson WR, Chen L, Amato MBP, Brochard LJ. Fifty years of research in ARDS. Respiratory mechanics in acute respiratory distress syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2017) 196:822–33. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201612-2495CI

12. Marongiu I, Spinelli E, Scotti E, Mazzucco A, Wang YM, Manesso L, et al. Addition of 5% CO2 to inspiratory gas prevents lung injury in an experimental model of pulmonary artery ligation. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2021) 204:933–42. doi: 10.1164/rccm.202101-0122OC

13. Broccard AF, Hotchkiss JR, Vannay C, Markert M, Sauty A, Feihl F, et al. Protective effects of hypercapnic acidosis on ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2001) 164:802–6. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.164.5.2007060

14. Sinclair SE, Kregenow DA, Lamm WJ, Starr IR, Chi EY, Hlastala MP. Hypercapnic acidosis is protective in an in vivo model of ventilator-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2002) 166:403–8. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200112-117OC

15. Laffey JG, Honan D, Hopkins N, Hyvelin JM, Boylan JF, McLoughlin P. Hypercapnic acidosis attenuates endotoxin-induced acute lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2004) 169:46–56. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200205-394OC

16. Severinghaus JW, Swenson EW, Finley TN, Lategola MT, Williams J. Unilateral hypoventilation produced in dogs by occluding one pulmonary artery. J Appl Physiol. (1961) 16:53–60. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1961.16.1.53

17. Shepard JW Jr, Hauer D, Miyai K, Moser KM. Lamellar body depletion in dogs undergoing pulmonary artery occlusion. J Clin Invest. (1980) 66:36–42. doi: 10.1172/JCI109832

18. Fan E, Del Sorbo L, Goligher EC, Hodgson CL, Munshi L, Walkey AJ, et al. American Thoracic Society ESoICM, Society of Critical Care M. An Official American Thoracic Society/European Society of Intensive Care Medicine/Society of Critical Care Medicine Clinical Practice Guideline: Mechanical Ventilation in Adult Patients with Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2017) 195:1253–63. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201703-0548ST

19. Spinelli E, Kircher M, Stender B, Ottaviani I, Basile MC, Marongiu I, et al. Unmatched ventilation and perfusion measured by electrical impedance tomography predicts the outcome of ARDS. Crit Care. (2021) 25:192. doi: 10.1186/s13054-021-03615-4

20. Meyerholz DK, Lambertz AM, Reznikov LR, Ofori-Amanfo GK, Karp PH, McCray PB Jr, et al. Immunohistochemical detection of markers for translational studies of lung disease in pigs and humans. Toxicol Pathol. (2016) 44:434–41. doi: 10.1177/0192623315609691

21. Faversani A, Vaira V, Moro GP, Tosi D, Lopergolo A, Schultz DC, et al. Survivin family proteins as novel molecular determinants of doxorubicin resistance in organotypic human breast tumors. Breast Cancer Res. (2014) 16:R55. doi: 10.1186/bcr3666

22. Jindal SK, Lakshminarayan S, Kirk W, Butler J. Acute increase in anastomotic bronchial blood flow after pulmonary arterial obstruction. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. (1984) 57:424–8. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1984.57.2.424

23. Baile EM, Pare PD. Response of the bronchial circulation to acute hypoxemia and hypercarbia in the dog. J Appl Physiol Respir Environ Exerc Physiol. (1983) 55:1474–9. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1983.55.5.1474

24. Frohlich S, Boylan J, McLoughlin P. Hypoxia-induced inflammation in the lung: a potential therapeutic target in acute lung injury? Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. (2013) 48:271–9. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2012-0137TR

25. Setzer F, Schmidt B, Hueter L, Schwarzkopf K, Sanger J, Schreiber T. Characterization of the seven-day course of pulmonary response following unilateral lung acid injury in rats. PLoS ONE. (2018) 13:e0198440. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198440

26. Laffey JG, Engelberts D, Duggan M, Veldhuizen R, Lewis JF, Kavanagh BP. Carbon dioxide attenuates pulmonary impairment resulting from hyperventilation. Crit Care Med. (2003) 31:2634–40. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000089646.52395.BA

27. Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome N, Brower RG, Matthay MA, Morris A, Schoenfeld D, Thompson BT, et al. Ventilation with lower tidal volumes as compared with traditional tidal volumes for acute lung injury and the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med. (2000) 342:1301–8. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005043421801

28. Hickling KG, Henderson SJ, Jackson R. Low mortality associated with low volume pressure limited ventilation with permissive hypercapnia in severe adult respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. (1990) 16:372–7. doi: 10.1007/BF01735174

29. Nin N, Muriel A, Penuelas O, Brochard L, Lorente JA, Ferguson ND, et al. Severe hypercapnia and outcome of mechanically ventilated patients with moderate or severe acute respiratory distress syndrome. Intensive Care Med. (2017) 43:200–8. doi: 10.1007/s00134-016-4611-1

30. Lang JD, Figueroa M, Sanders KD, Aslan M, Liu Y, Chumley P, et al. Hypercapnia via reduced rate and tidal volume contributes to lipopolysaccharide-induced lung injury. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2005) 171:147–57. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200302-305OC

31. Fuchs H, Mendler MR, Scharnbeck D, Ebsen M, Hummler HD. Very low tidal volume ventilation with associated hypercapnia–effects on lung injury in a model for acute respiratory distress syndrome. PLoS ONE. (2011) 6:e23816. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023816

32. Hummler HD, Banke K, Wolfson MR, Buonocore G, Ebsen M, Bernhard W, et al. The effects of lung protective ventilation or hypercapnic acidosis on gas exchange and lung injury in surfactant deficient rabbits. PLoS ONE. (2016) 11:e0147807. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0147807

Keywords: ventilator-induced lung injury, pulmonary perfusion, inhaled CO2, therapeutic hypercapnia, mechanical ventilation

Citation: Spinelli E, Pesenti A, Lopez G, Damia A, Damarco F, Garbelli E, Dal Santo G, Caccioppola A, Giudici G, Figgiaconi V, Biancolilli O, Battistin M, Lonati C, Vaira V, Rosso L, Ferrero S, Gatti S and Mauri T (2022) Inhaled CO2 vs. Hypercapnia Obtained by Low Tidal Volume or Instrumental Dead Space in Unilateral Pulmonary Artery Ligation: Any Difference for Lung Protection? Front. Med. 9:901809. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.901809

Received: 22 March 2022; Accepted: 19 April 2022;

Published: 20 May 2022.

Edited by:

Savino Spadaro, University of Ferrara, ItalyReviewed by:

John Laffey, National University of Ireland Galway, IrelandStephan Böhm, University Hospital Rostock, Germany

Copyright © 2022 Spinelli, Pesenti, Lopez, Damia, Damarco, Garbelli, Dal Santo, Caccioppola, Giudici, Figgiaconi, Biancolilli, Battistin, Lonati, Vaira, Rosso, Ferrero, Gatti and Mauri. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tommaso Mauri, dG9tbWFzby5tYXVyaUB1bmltaS5pdA==

Elena Spinelli

Elena Spinelli Antonio Pesenti1,2

Antonio Pesenti1,2 Francesco Damarco

Francesco Damarco Gaia Dal Santo

Gaia Dal Santo Caterina Lonati

Caterina Lonati Valentina Vaira

Valentina Vaira Lorenzo Rosso

Lorenzo Rosso Stefano Ferrero

Stefano Ferrero Tommaso Mauri

Tommaso Mauri