94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Med. , 05 April 2022

Sec. Intensive Care Medicine and Anesthesiology

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2022.871515

This article is part of the Research Topic Clinical Teaching and Practice in Intensive Care Medicine and Anesthesiology View all 17 articles

Enda O'Connor1,2*†

Enda O'Connor1,2*† Evin Doyle1,2†

Evin Doyle1,2†Introduction: Anesthesia and intensive care medicine are relatively new undergraduate medical placements. Both present unique learning opportunities and educational challenges to trainers and medical students. In the context of ongoing advances in medical education assessment and the importance of robust assessment methods, our scoping review sought to describe current research around medical student assessment after anesthesia and intensive care placements.

Methods: Following Levac's 6 step scoping review guide, we searched PubMed, EMBASE, EBSCO, SCOPUS, and Web of Science from 1980 to August 2021, including English-language original articles describing assessment after undergraduate medical placements in anesthesia and intensive care medicine. Results were reported in accordance with PRISMA scoping review guidelines.

Results: Nineteen articles published between 1983 and 2021 were selected for detailed review, with a mean of 119 participants and a median placement duration of 4 weeks. The most common assessment tools used were multiple-choice questions (7 studies), written assessment (6 studies) and simulation (6 studies). Seven studies used more than one assessment tool. All pre-/post-test studies showed an improvement in learning outcomes following clinical placements. No studies used workplace-based assessments or entrustable professional activities. One study included an account of theoretical considerations in study design.

Discussion: A diverse range of evidence-based assessment tools have been used in undergraduate medical assessment after anesthesia and intensive care placements. There is little evidence that recent developments in workplace assessment, entrustable activities and programmatic assessment have translated to undergraduate anesthesia or intensive care practice. This represents an area for further research as well as for curricular and assessment developments.

The inclusion of anesthesia and intensive care medicine (ICM) in undergraduate medical student placements is a relatively new development (1). Recent publications have sought to define suitable curricula in these disciplines (2, 3). With expanding placement opportunities come an ever-increasing obligation to ensure that student learning is effective and efficient, that student time is “well-spent,” and that we “maximize assessment for learning while at the same time arriving at robust decisions about learner's progress” (4).

The ICU and the anesthetic room can be challenging areas for student learning. Opportunities for history-taking and clinical examination are variable (1, 5). Patients undergoing anesthesia require a focused history and examination tailored to the upcoming anesthetic and surgical procedure (5). ICM patients are commonly sedated and/or confused, impeding history-taking. Clinical examination in the intensive care unit (ICU) is more challenging in the context of an immobile, unresponsive patient on extracorporeal devices (dialysis, mechanical ventilation). Furthermore, in both disciplines, procedural learning is often limited by the complex, high-stakes, time-sensitive aspects of common tasks (1, 5).

Conversely, anesthesia and ICM share learning opportunities not readily available during other placements. They are ideal environments for the vertical integration of primary and clinical sciences (6). Many learning topics are unique to these disciplines (e.g., acute respiratory distress syndrome, clinical brainstem death evaluation, inhalation anesthesia, pharmacological neuromuscular blockade). Other key elements of their curricula (e.g., the management of acute respiratory failure, shock, acute airway emergencies, sedation administration) are generic, high-stakes, transferrable clinical skills that could be viewed as important competencies for all doctors.

Current evidence suggests that ICM and anesthesia placements can achieve effective student learning outcomes (7). Nonetheless, the unique nature of their curricula may require a bespoke approach to learner assessment. Furthermore, valid and reliable tools are central to assessment decisions regarding high stakes competencies such as effective acute and perioperative patient care. Despite this, three recent papers on curriculum and effective teaching in the ICU and anesthetic room make no recommendations about student assessment (2, 3, 5). The first objective of our review therefore was to evaluate the nature and robustness of published assessment strategies in these high-stakes clinical specialties, incorporating an analysis of the theoretical bases for these publications.

The expansion of undergraduate anesthesia and ICM placements has occurred contemporaneously with an evolution in medical education assessment. Accordingly, practice is moving away from evaluating low-level cognitive learning objectives such as knowledge and understanding (using MCQs, written examinations) toward knowledge application (using extended matching questions, OSCEs) and most recently to clinical performance, either in a simulated or workplace environment (8–11). Furthermore, longitudinal methods such as programmatic assessment have in recent years gained in popularity (12). The extent to which this evolution has translated to assessment in undergraduate anesthesia and ICM education was the second objective of our review.

A scoping review methodology was used for two reasons. First, the authors had prior knowledge of the research topic and recognized that the range of published literature was unlikely to yield research of sufficient quality to enable a systematic review or a meta-analysis. Second, in light of recent advances in assessment practice, we anticipated a knowledge and/or research gap in the areas of anesthesia and ICM assessment. Our study methodology therefore needed to be tailored to identifying these gaps were they to exist (13, 14).

We used the 6-step adaptation of Arksey and O'Malley's (15) scoping review framework as proposed by Levac et al. (13). These steps are (1) identifying research questions, (2) identifying relevant articles, (3) study selection, (4) charting the data, (5) collating, summarizing, and reporting the results and (6) consulting with stakeholders. In addition, we applied a scoping review quality checklist to enhance the rigor of our findings (16). The overarching purposes of our scoping review were (a) to describe the nature of existing research about undergraduate assessment after anesthesia/ICM placements and (b) to identify research gaps in this area.

The following six steps were applied.

The scoping research questions were:

1. What methods and practices of assessment have been reported in the literature for students undertaking clinical placements in anesthesia and/or intensive care medicine?

2. What educational theories have been articulated for the assessment methods published in the literature?

Using five online databases (EMBASE, SCOPUS, EBSCO, PubMed, Web of Science) we conducted a search for all available papers from January 1980 to 31/12/2020, using the search terms “medical student,” and several variations on “anesthesia” and “intensive care” to account for differences in regional terminology (see Figure 1). A librarian was used to assist with accessing articles. Reference lists of relevant articles were also included in the search. Due to the pandemic, the high intensive care and anesthesia workload in early 2021 led to a reallocation of research to clinical time, delaying the completion of the scoping review. Accordingly, a further search was performed up to 31/08/2021.

To be included, studies had to describe original research using an assessment tool following an undergraduate placement in anesthesia and/or intensive care medicine. Studies were excluded if they were not published in English, if they enrolled postgraduate or non-medical learners, or if the assessment followed a standalone courses rather than a clinical placement.

The three stages of study selection were based on title, abstract, and full-text searches respectively. Mendeley© software was used. The two authors independently screened the publications for study inclusion. A Cohen's kappa coefficient was calculated to quantify author agreement at each stage of study selection. The authors met regularly to discuss and resolve any disagreements about study inclusion. The number of studies included in each stage of selection, and the exclusion criteria are shown in the flowchart in Figure 1.

Evaluating each study involved a combination of numerical description and general thematic analysis. For the former, the following information was extracted from each article: lead author; country of authorship; journal title; the year of publication; study design; number of research sites; sample size; assessment tools used; quantitative outcomes; Miller's learning outcomes (17); MERQSI score (18). Through thematic analysis, other details about the studies were recorded, including qualitative outcomes, important author's quotes, theoretical considerations and any insights pertinent to the research area. In accordance with Levac et al. (13) scoping review methodology, the 2 authors met following data extraction of the first 6 articles to determine whether the approach was “consistent with the research question and purpose” (page 4). Study authors were contacted directly if further information or clarification about their findings were deemed appropriate.

The information drawn from each article was summarized and tabulated (see Table 1).

Consultation was undertaken via email with 3 stakeholders involved in undergraduate education and/or anaesthesiology/intensive care medicine teaching, each working in a different academic institution. Preliminary study results were shared with them. The purpose of the consultation was to seek opinions about any omitted sources of study information, to gain additional perspectives on the study topics, and to invite opinions about the study findings.

A total of 2,435 results were returned from the initial search between the 5 databases, of which 17, published between 1983 and 2020, were selected for full-text review (6, 20–34, 36). The second search performed in August 2021 returned 2 further studies published in 2021 (19, 35). The findings of these 19 studies are shown in Table 1.

Of the 19 studies, 9 (47.4%) involved anesthesia (21, 23–25, 28–32), 8 (42.1%) intensive care medicine (6, 19, 20, 26, 27, 33–35) and 2 (10.5%) a combination of both disciplines (22, 36). The primary research focus was on the assessment instrument and on student learning in 9 (22–26, 28–30, 36) and 7 (19–21, 27, 32, 33, 35) studies respectively. The remaining 3 studies had equal research focus on learning and the assessment tool.

All were single-center studies, 14 of which (73.7%) were conducted in Canada, USA and Hong Kong. The average sample size across all studies was 119 students (range 5–466). Clinical placements lasted 2–12 weeks, with a median duration of 4 weeks. Fourteen studies (73.7%) had 2 or 4 week placements.

Twelve of 19 studies (63.2%) had a non-randomized design and collected assessment data at one timepoint only (20–25, 28–32, 36). Conversely, the remaining 7 studies (36.8%) were either RCTs and/or had a pre-/post-test study design (6, 19, 26, 27, 33–35). Despite all studies reporting solely or mainly quantitative data, none conducted a power analysis to evaluate the required sample size. Ten studies (52.6%) considered the issues of the reliability and/or validity of their assessment tools (6, 21–26, 28, 30, 31). Two additional studies used standardized assessment questions from the Society of Critical Care Medicine and the American College of Physicians (20, 35). The average MERQSI score was 12.3 (range 5–15) out of a maximum of 18.

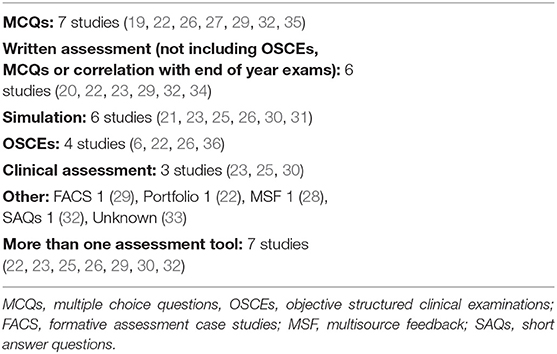

A wide variety of student assessment tools were used across the 19 included studies. These are shown in Table 2. The most common methods were multiple choice questions (7 studies; 36.8%) (19, 22, 26, 27, 29, 32, 35), written assessment (6 studies; 31.6%) (20, 22, 23, 29, 32, 34) and simulation (6 studies; 31.6%) (21, 23, 25, 26, 30, 31).

Table 2. Assessment tools used following clinical placements in Anaesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine.

Seven studies (36.8%) used a combination of more than one assessment tool (22, 23, 25, 26, 29, 30, 32), which in 3 studies included final end-of-year examinations (22, 25, 30).

All 7 studies with a pre-/post-test design showed an improvement in assessment outcomes after clinical placements. All had a 4 week/1 month clinical placement and all were in intensive care medicine. Only 2 of these 7 studies evaluated student performance using simulation and/or OSCE stations (6, 26). The remaining 5 studies evaluated student knowledge using MCQs or written assessment tools (19, 27, 33–35).

Of the five studies with a primary research focus on student learning, contextual learning theory was used as the theoretical basis for one study (20). No other study made any methodological references to an underlying educational theory.

Though seldom articulated, Miller's Pyramid of learning outcomes was an important theoretical foundation in most of the studies (17). Nine studies (47.4% evaluated learning outcomes in the “shows how” level 3 domain using simulation (21, 23, 25, 26, 30, 31) and/or OSCEs (6, 22, 26, 36). Ten studies had learning outcomes in the “knows” or “knows how” domains, using a combination of MCQs, SAQs, essay questions or online case studies (19, 20, 22, 23, 26, 27, 29, 32, 34, 35). One study did not describe the assessment tool used (33). Finally, two studies evaluated student performance in the workplace using subjective observation (24) and multi-source feedback (28), thereby targeting Miller level 4 “does” learning outcomes. No study used workplace assessment tools (WPAs) to assess undergraduate learning outcomes.

Our scoping review illustrates the heterogeneity of literature around assessment in undergraduate anesthesia and intensive care medicine. Published studies used numerous assessment instruments targeting learning outcomes that were either knowledge-based (using selected-response MCQs and constructed-response written tests) or performance-based (using OSCEs or a simulated clinical environment). The findings of the review also attest to the meaningful undergraduate learning that can occur in these clinical settings.

Though heterogenous, a majority of the included studies used evidence-based assessment strategies insofar as either the chosen tools have strong evidence supporting their use in UGME (MCQs, written exams, simulation, OSCEs) or more than one method was used to inform assessment decisions (8, 9, 37). Furthermore, all except one study (33) used an assessment strategy appropriate to the learning outcomes mapped to Miller's pyramid.

A key objective of undergraduate medical education is to equip students with the competencies to deliver effective and safe patient care in their first year of medical practice and beyond. The assessment of knowledge, or the theoretical application of that knowledge alone may not be sufficient to judge whether students are equipped with those skills (38). Accordingly, 9 studies in our review adopted a competency-based approach and used OSCEs or simulation to evaluate student performance. Only 3 of these studies however used complementary tools to evaluate learning in the domains of knowledge and understanding as well as competence (22, 23, 26). These are the most informative studies in our review for educators making instructional design decisions about student assessment after anesthesia and ICM placements.

The most frequent tool used to evaluate student performance in our review was simulation, whereby learners were assessed in the “show how” learning domain. Performance in a simulated environment however correlated poorly with written assessments, suggesting a role for both tools in reaching a more complete assessment decision about a student's learning outcomes. There was scant evidence in the studies however of observed performance assessment in the workplace–the “does” domain of Miller's pyramid–which likely reflects a lack of active student work in ICUs and anesthetic rooms; students in these environments are more likely to learn by observing than by doing.

Nonetheless, recent trends in undergraduate assessment have led to greater emphasis on workplace performance and to the use of entrustable professional activities (EPAs) (39–41). EPAs entail assessors observing students performing “units of work” (42) (p2) thereby judging the level of supervision each student needs with that activity–the entrustment decision (11). They are mapped to learning curricula and are commonly informed by assessment in the workplace (11). To date, most EPA studies in UGME centre around internal medicine and general surgery. While we identified no studies using EPAs solely for the purposes of undergraduate anesthesia/ICM assessment, some include anesthesia or ICM placements as part of a broad learning curriculum (43–45). Furthermore, of the 13 undergraduate EPAs published by the Association of American Medical Colleges, 3 (e.g., recognize a patient requiring urgent or emergent care and initiate evaluation and management) have direct relevance to ICM and anesthesia (46). The use of EPAs also helps address long-standing concerns about graduating student's readiness to commence internship (47). A strong case can therefore be made for applying EPAs to anesthesia and ICM.

We did not identify any studies using a programmatic approach to assessment, though our literature search may not have found studies which included anesthesia or ICM as part of a broader programme-wide assessment strategy. Moreover, programmatic assessment challenges the “module-specific” nature of traditional UGME, viewing a clinical placement within a broader context of an overall curriculum (12). Therefore, it does not readily apply to our review, which ab initio focused on the assessment of a specific placement in anesthesia or ICM.

A common criticism of education research is that theoretical considerations are not brought to the fore. This also applies to the majority of articles in our review. Notwithstanding this, most of the included studies were designed in such a way that the use of a theoretical paradigm could be implied. Moreover, some of the studies used instructional design methodology. The primary use of technology to enhance learning in 3 studies (27, 29, 32) draws from eLearning theory (48). Adopting problem-based learning in 3 further studies acknowledged the importance of constructivism in effective education (6, 26, 34). Aspects of workplace learning theory were evident in the numerous studies that promoted learning within the operating theater and/or the intensive care unit (6, 20, 22, 23, 26, 29, 30, 33, 34, 36). The 6 studies using simulation for assessment (21, 23, 25, 26, 30, 31) likely reflected the importance of experiential learning theory and reflection (49).

A recent development that is difficult to ignore is the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on undergraduate education. Accounts of formal assessment in the context of students working or learning during the pandemic appear to be rare (19). This likely reflects the time constraints and staff redeployment during the pandemic when clinical activities took precedence over faculty pursuits (50). Paradoxically, when viewed through the lens of Miller's pyramid, at a time when students may have been more actively involved in clinical care–in “doing” work–they were least likely to be formally assessed.

Our study therefore highlights a gap between published research in anesthesia/ICM assessment and recent advances in undergraduate assessment. However, for practice to change in these disciplines, the approach to student education in anesthetic rooms and ICUs must first evolve to allow more active student participation in daily clinical activities. Observed workplace assessment can only occur in environments where learners play a legitimate role in patient care. This is the main research gap identified in our review and is an important area for future research into the undergraduate study of anesthesia and intensive care medicine.

Our study results may be limited by the omission of some relevant articles. Each author however individually performed the search and results were then combined. Studies were individually evaluated for inclusion and though Cohen's coefficient showed a suboptimal correlation, author discussion at each step of study selection addressed any differences in opinion. We included any study where discussion did not resolve perceived differences. To improve the rigor of our study, we used the guidelines published by Maggio et al. in all stages of our review (16). We consulted with key external stakeholders but this step yielded no additional information.

In conclusion, our findings yield three useful insights. First, they act as a practice guide for educators directly involved in the design, delivery, and assessment of undergraduate learning in anesthesia and intensive care medicine. Second, they are informative for university educators tasked with the general organization and design of undergraduate medical education, helping them position anesthesia and intensive care medicine in strategies around programmatic assessment and workplace-based entrustable decision-making. Finally, they identify a large research gap for future studies to focus upon.

EO'C and ED were equally involved in all aspects of this study including design, literature searches, data collection, and manuscript writing. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

1. Whereat S, McLean A. Survey of the current status of teaching intensive care medicine in Australia and New Zealand medical schools. Crit Care Med. (2012) 40:430–4. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31823295fe

2. Smith A, Brainard J, Campbell K. Development of an undergraduate medical education critical care content outline utilizing the delphi method. Crit Care Med. (2020) 48:98–103. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0000000000004086

3. Smith A, Carey C, Sadler J, Smith H, Stephens R, Frith C. Undergraduate education in anaesthesia, intensive care, pain, and perioperative medicine: the development of a national curriculum framework. Med Teach. (2018) 41:340–6. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1472373

4. van der Vleuten C, Schuwirth L, Driessen E, Dijkstra J, Tigelaar D, Baartman L, et al. A model for programmatic assessment fit for purpose. Med Teach. (2012) 34:205–14. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2012.652239

5. Doyle S, Sharp M, Winter G, Khan M, Holden R, Djondo D, et al. Twelve tips for teaching in the ICU. Med Teach. (2021) 43:1005–9. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2020.1859097

6. Rajan S, Jacob T, Sathyendra S. Vertical integration of basic science in final year of medical education. Int J Appl Basic Med Res. (2016) 6:182. doi: 10.4103/2229-516X.186958

7. Rogers P, Jacob H, Thomas E, Harwell M, Willenkin R, Pinsky M. Medical students can learn the basic application, analytic, evaluative, and psychomotor skills of critical care medicine. Crit Care Med. (2000) 28:550–4. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200002000-00043

8. Norcini J, Anderson B, Bollela V, Burch V, Costa M, Duvivier R, et al. Criteria for good assessment: consensus statement and recommendations from the Ottawa 2010 conference. Med Teach. (2011) 33:206–14. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2011.551559

9. Norcini J, Anderson M, Bollela V, Burch V, Costa M, Duvivier R, et al. 2018 Consensus framework for good assessment. Med Teach. (2018) 40:1102–9. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1500016

10. Heeneman S, de Jong L, Dawson L, Wilkinson T, Ryan A, Tait G, et al. Ottawa 2020 consensus statement for programmatic assessment – 1. agreement on the principles. Med Teach. (2021) 43:1139–48. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2021.1957088

11. ten Cate O, Chen H, Hoff R, Peters H, Bok H, van der Schaaf M. Curriculum development for the workplace using entrustable professional activities (EPAs): AMEE guide No. 99. Med Teach. (2015) 37:983–1002. doi: 10.3109/0142159X.2015.1060308

12. Torre D, Schuwirth L, Van der Vleuten C. Theoretical considerations on programmatic assessment. Med Teach. (2019) 42:213–20. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2019.1672863

13. Levac D, Colquhoun H, O'Brien K. Scoping studies: advancing the methodology. Implement Sci. (2010) 5:69. doi: 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69

14. Munn Z, Peters M, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. (2018) 18:143. doi: 10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

15. Arksey H, O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int J Soc Res Methodol. (2005) 8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616

16. Maggio L, Larsen K, Thomas A, Costello J, Artino A. Scoping reviews in medical education: a scoping review. Med Educ. (2020) 55:689–700. doi: 10.1111/medu.14431

17. Miller G. The assessment of clinical skills/competence/performance. Academic Medicine. (1990) 65:S63–7. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199009000-00045

18. Reed D, Beckman T, Wright S, Levine R, Kern D, Cook D. Predictive validity evidence for medical education research study quality instrument scores: quality of submissions to JGIM's medical education special issue. J Gen Intern Med. (2008) 23:903–7. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0664-3

19. Ho J, Susser P, Christian C, DeLisser H, Scott M, Pauls L, et al. Developing the eMedical Student (eMS)—a pilot project integrating medical students into the tele-ICU during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond. Healthcare. (2021) 9:73. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9010073

20. Lofaro M, Abernathy C. An innovative course in surgical critical care for second-year medical students. Acad Med. (1994) 69:241–3. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199403000-00022

21. Moll-Khosrawi P, Kamphausen A, Hampe W, Schulte-Uentrop L, Zimmermann S, Kubitz J. Anaesthesiology students' non-technical skills: development and evaluation of a behavioural marker system for students (AS-NTS). BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:205. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1609-8

22. Shams T, El-Masry R. al Wadani H, Amr M. Assessment of current undergraduate anaesthesia course in a Saudi University. Saudi J Anaesth. (2013) 7:122. doi: 10.4103/1658-354X.114049

23. Morgan PJ, Cleave-Hogg D. Evaluation of medical students' performance using the anaesthesia simulator. Med Educ. (2000) 34:42–5. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2923.2000.00462.x

24. Hamid A, Schmuck M, Cordovani D. The lack of construct validity when assessing clinical clerks during their anesthesia rotations. Can J Anesth. (2020) 67:1081–2. doi: 10.1007/s12630-020-01597-5

25. Morgan P, Cleave-Hogg D, DeSousa S, Tarshis J. High-fidelity patient simulation: validation of performance checklists. Br J Anaesth. (2004) 92:388–92. doi: 10.1093/bja/aeh081

26. Rogers P, Jacob H, Rashwan A, Pinsky M. Quantifying learning in medical students during a critical care medicine elective: a comparison of three evaluation instruments. Crit Care Med. (2001) 29:1268–73. doi: 10.1097/00003246-200106000-00039

27. Skinner J, Knowles G, Armstrong R, Ingram D. The use of computerized Learning in intensive care: an evaluation of a new teaching program. Med Educ. (1983) 17:49–53. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.1983.tb01093.x

28. Sharma N, White J. The use of multi-source feedback in assessing undergraduate students in a general surgery/anesthesiology clerkship. Med Educ. (2010) 44:5–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03702.x

29. Critchley L, Kumta S, Ware J, Wong J. Web-based formative assessment case studies: role in a final year medicine two-week anaesthesia course. Anaesth Intensive Care. (2009) 37:637–45. doi: 10.1177/0310057X0903700408

30. Morgan P, Cleave-Hogg D, Guest C, Herold J. Validity and reliability of undergraduate performance assessments in an anesthesia simulator. Can J Anesth. (2001) 48:225–33. doi: 10.1007/BF03019750

31. Morgan PJ, Cleave-Hogg D, DeSousa S, Tarshis J. Identification of gaps in the achievement of undergraduate anesthesia educational objectives using high-fidelity patient simulation. Anesth Analg. (2003) 97:1690–4. doi: 10.1213/01.ANE.0000086893.39567.D0

32. Leung J, Critchley L, Yung A, Kumta S. Evidence of virtual patients as a facilitative learning tool on an anesthesia course. Adv Health Sci Educ. (2014) 20:885–901. doi: 10.1007/s10459-014-9570-0

33. Kapur N, Birk V, Trivedi A. Implementation of a formal medical intensive care unit (MICU) curriculum for medical students. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. (2019) 199:A4789. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm-conference.2019.199.1_MeetingAbstracts.A4789

34. Rogers P, Grenvik A, Willenkin R. Teaching medical students complex cognitive skills in the intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. (1995) 23:575–81. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199503000-00025

35. Gergen D, Raines J, Lublin B, Neumeier A, Quach B, King C. Integrated critical care curriculum for the third-year internal medicine clerkship. MedEdPORTAL. (2020) 16:11032. doi: 10.15766/mep_2374-8265.11032

36. Critchley L, Short T, Buckley T, Gin T, O'Meara M, Oh T. An adaptation of the objective structured clinical examination to a final year medical student course in anaesthesia and intensive care. Anaesthesia. (1995) 50:354–8. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2044.1995.tb04617.x

37. Gordon C, Ryall T, Judd B. Simulation-based assessments in health professional education: a systematic review. J Multidiscip Healthc. (2016) 9:69–82. doi: 10.2147/JMDH.S92695

38. Shumway JM, Harden RM. AMEE education guide No 25: the assessment of learning outcomes for the competent and reflective physician. Med Teach. (2003) 25:569–84. doi: 10.1080/0142159032000151907

39. Shorey S, Lau T, Lau S, Ang E. Entrustable professional activities in health care education: a scoping review. Med Educ. (2019) 53:766–77. doi: 10.1111/medu.13879

40. Meyer E, Chen H, Uijtdehaage S, Durning S, Maggio L. Scoping review of entrustable professional activities in undergraduate medical education. Acad Med. (2019) 94:1040–9. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000002735

41. Pinilla S, Lenouvel E, Cantisani A, Klöppel S, Strik W, Huwendiek S, et al. Working with entrustable professional activities in clinical education in undergraduate medical education: a scoping review. BMC Med Educ. (2021) 21:172. doi: 10.1186/s12909-021-02608-9

42. Peters H, Holzhausen Y, Maaz A, Driessen E, Czeskleba A. Introducing an assessment tool based on a full set of end-of-training EPAs to capture the workplace performance of final-year medical students. BMC Med Educ. (2019) 19:207. doi: 10.1186/s12909-019-1600-4

43. Barrett J, Trumble S, McColl G. Novice students navigating the clinical environment in an early medical clerkship. Med Educ. (2017) 51:1014–24. doi: 10.1111/medu.13357

44. Jonker G, Booij E, Otte W, Vlijm C, Ten Cate O, Hoff R. An elective entrustable professional activity-based thematic final medical school year: an appreciative inquiry study among students, graduates, and supervisors. Adv Med Educ Pract. (2018) 9:837–45. doi: 10.2147/AMEP.S176649

45. ten Cate O, Graafmans L, Posthumus I, Welink L, van Dijk M. The EPA-based Utrecht undergraduate clinical curriculum: development and implementation. Med Teach. (2018) 40:506–13. doi: 10.1080/0142159X.2018.1435856

46. Englander R, Flynn T, Call S, Carraccio C, Cleary L, Fulton T, et al. Toward defining the foundation of the MD degree: core entrustable professional activities for entering residency. Acad Med. (2016) 91:1352–8. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001204

47. Bosch J, Maaz A, Hitzblech T, Holzhausen Y, Peters H. Medical students' preparedness for professional activities in early clerkships. BMC Med Educ. (2017) 17:140. doi: 10.1186/s12909-017-0971-7

48. Mayer RE. Elements of a science of e-learning. J Educ Comput Res. (2003) 29:297–313. doi: 10.2190/YJLG-09F9-XKAX-753D

Keywords: intensive care, undergraduate education best practices, assessment and education, anesthesia, scoping review methodology

Citation: O'Connor E and Doyle E (2022) A Scoping Review of Assessment Methods Following Undergraduate Clinical Placements in Anesthesia and Intensive Care Medicine. Front. Med. 9:871515. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2022.871515

Received: 08 February 2022; Accepted: 09 March 2022;

Published: 05 April 2022.

Edited by:

Longxiang Su, Peking Union Medical College Hospital (CAMS), ChinaReviewed by:

Heather Braund, Queen's University, CanadaCopyright © 2022 O'Connor and Doyle. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Enda O'Connor, b2Nvbm5vZW5AdGNkLmll

†ORCID: Enda O'Connor orcid.org/0000-0002-9558-6061

Evin Doyle orcid.org/0000-0003-3179-9436

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.