94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS article

Front. Med. , 09 March 2021

Sec. Regulatory Science

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.617625

This article is part of the Research Topic Women in Science - Regulatory Science 2021 View all 13 articles

Linda L. D. Zhong1,2,3*

Linda L. D. Zhong1,2,3* Wai Ching Lam1,2,4

Wai Ching Lam1,2,4 Fang Lu5

Fang Lu5 Xu Dong Tang5

Xu Dong Tang5 Aiping Lyu1,2

Aiping Lyu1,2 Zhaoxiang Bian1,2

Zhaoxiang Bian1,2 Heather Boon3*

Heather Boon3*Ethnopharmacological Relevance: Chinese Medicine plays a symbolic role among traditional medicines. As Chinese Medicine products are widely used around the globe, regulations for Chinese Medicine products are often used as models for the efficient regulation of natural products that are safe, and high-quality.

Aim of the Study: We aimed to compare the regulatory registration requirements for Proprietary Chinese Medicines in Hong Kong and Canada.

Materials and Methods: We compared registration requirements for Proprietary Chinese Medicine in Hong Kong and Canada based on publicly available information provided by the respective Regulators. A marketed product, Zhizhu Kuanzhong Capsule (SFDA approval number Z20020003; NPN approval number 80104354), was used as a case study to demonstrate the similarities and differences of the requirements in both Hong Kong and Canada.

Results: There were similarities and differences between the two regulatory systems in terms of the quality, safety and efficacy requirements. Despite the superficial appearance of similar categories and groups/classes, Hong Kong requires significantly more primary test data compared to Canada's reliance on attestation to manufacturing according the standards outlined in approved reference pharmacopeias/texts.

Conclusion: Improved understand of the similarity and differences will enable applicants to plan appropriate strategies for gaining product approval. Exploring ways to harmonize the regulatory process has the potential to benefit manufacturers, regulators, and patients by increasing efficiency and decreasing costs.

Regulation of health products is generally considered necessary to protect the public. The vast majority of countries have implemented policies and practices aimed at reviewing the safety and effectiveness of health products before allowing them to be marketed to the general population. In an increasingly globalized marketplace, manufacturers face a wide array of regulatory regimes as each country requests different information or evidence and often requires different standards for assessing products. While recognizing the right of each sovereign nation to set its own standards, one wonders whether voluntary harmonization of key standards and evidence requirements might save significant time and money ultimately increasing access of populations to safe, effective and high quality products.

The implementation of evidence-based reviews to avoid costly replication of efforts and facilitate timely access to medications has been a topic of global discussion and debate. For example, in the United States, the Prescription Drug User Fee Act VI and 21st Century Cures Act recommend a more effective and efficient regulatory review model, authorizing the Food and Drug Administration to enhance capacity to review products under a variety of models and pathways (1). In the European Union, the European Medicines Agency has been taking steps toward more flexible approaches to its drug approval system (2).

Traditional medicine is defined by the World Health Organization as “the sum total of the knowledge, skill, and practices based on the theories, beliefs, and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness” (3). Traditional medicine products often have long histories of use in their original cultural settings but may have limited translational research supporting their use. As demand for these products increases around the world, especially in markets outside the country of origin, there is an urgent need for regulation of traditional medicines. This creates challenges for regulators and manufactures. Regulators look for conventional scientific evidence of safety and efficacy, while consumers and manufacturers are concerned that over regulation may limit patient access to safe and effective medicines that have been used for hundreds of years in their country of origin. Unlike Western biomedicine, health claims of traditional medicines are sometimes difficult to evaluate in jurisdictions outside the country of origin where there may be limited experience or expertise in assessing the quality of traditional products. In addition, the significant variation in guidelines and requirements for product registration/licensing creates unnecessary barriers for manufacturers.

In order to explore these challenges, we conducted a case study of the regulatory requirements for obtaining a product license for Zhizhu Kuanzhong Capsule, a Proprietary Chinese Medicine in two policy environments: Hong Kong and Canada. Hong Kong and Canada were chosen because they both have well-developed regulatory systems for traditional medicines, but are based in very different cultures which allows the identification of similarities and differences that may have relevance for a range of systems. We focused on the quality control, safety, and effectiveness aspects of the regulatory process as these are arguably more amenable to possible harmonization across states and cultures. The paper concludes with a discussion of components of the regulatory process where harmonization may have the greatest impact to facilitate the efficiency of the regulatory approval process while also enhancing its rigor and ability to achieve the objective of protecting the public.

The regulatory pathway and requirements for Proprietary Chinese Medicine in Hong Kong and Canada are available online on their respective regulatory bodies' websites (4–7).

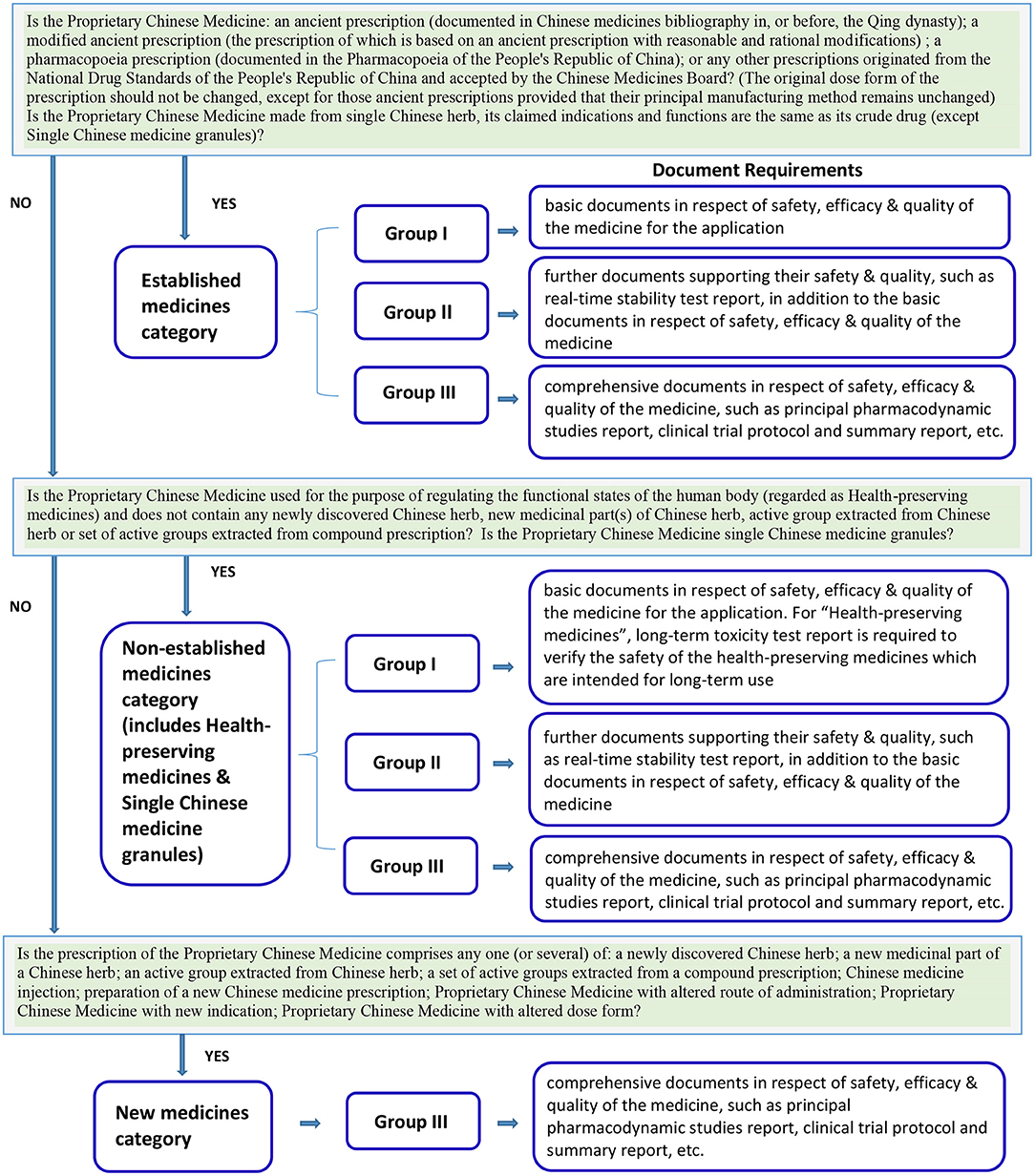

In Hong Kong, Proprietary Chinese Medicine is regulated by Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong, a statutory body established under the Chinese Medicine Ordinance established since 1999. Under the regulation, the selection of the classification category and the registration group of a Proprietary Chinese Medicine product license application is a decision made by the applicant and reviewed by the regulatory body. The registration requirements are dependent on the selected classification category and registration group (Figure 1). Other than the “New Medicine Category” that must be registered under Group III, for Proprietary Chinese Medicines under the “Established medicines category” (ancient or pharmacopeia prescriptions with original dose form) and “Non-established medicines category” (health-preserving medicines and single Chinese medicine granules), there are no distinctive guidelines which help the applicant to determine whether products should be registered under Group I, Group II or Group III. The applicants may choose to apply for registration in any of the three groups (8). This creates an incentive for applicants to select registration groups with fewer requirements, i.e., Group I with basic documents or Group II with further safety and quality supporting documents, instead of Group III which requires the submission of a dossier with comprehensive documents (see Table 1 for a summary of required materials). Though the applicants are encouraged to consult the Chinese Medicine Regulatory Office of the Department of Health, currently there is no official pre-submission meeting arrangement in Hong Kong to help ensure that the applicants have selected the right product license registration group.

Figure 1. The classification categories and registration groups of Proprietary Chinese Medicines and their requirements in Hong Kong (8).

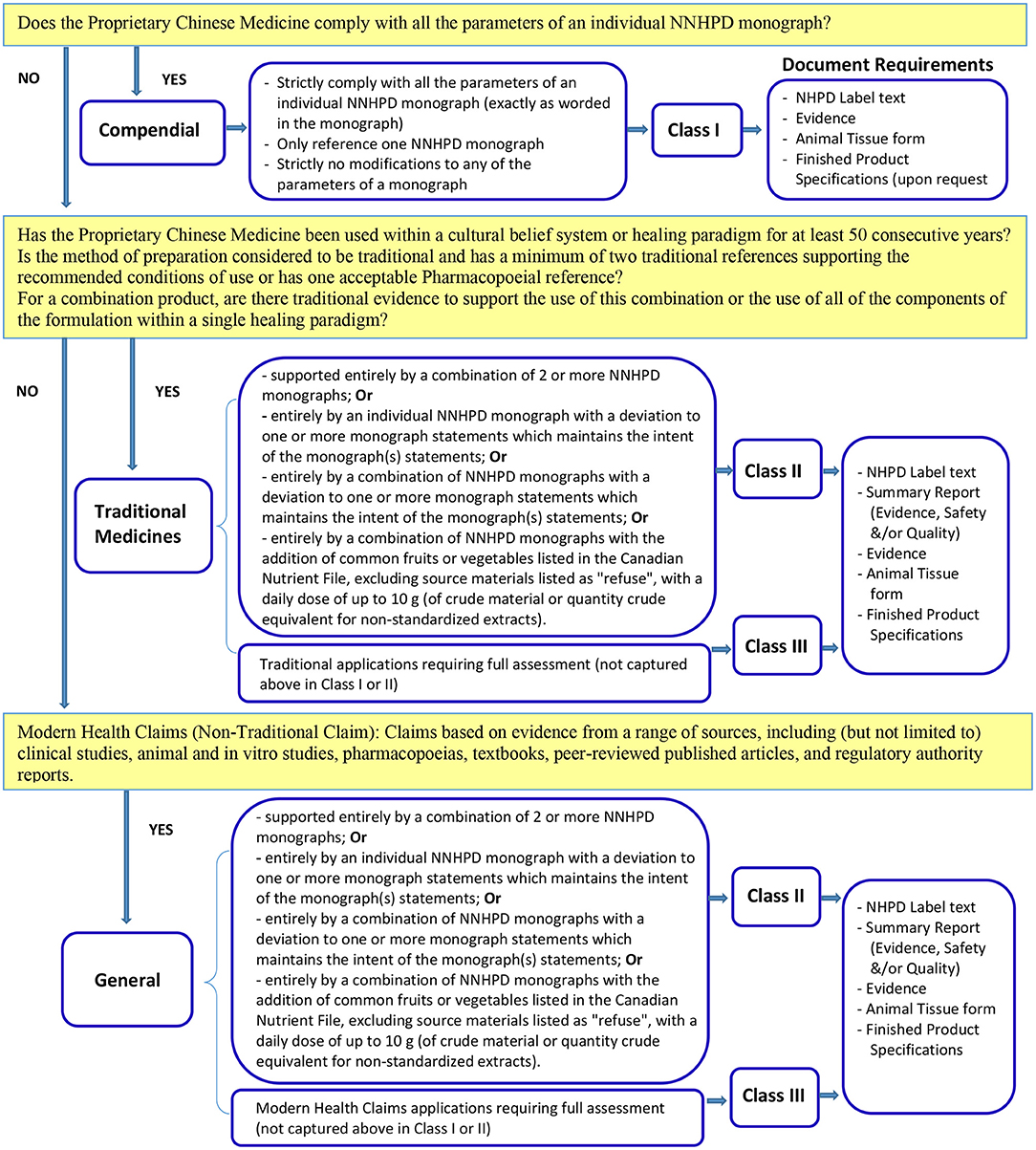

In Canada, Proprietary Chinese Medicine is defined as a natural health product (NHP) and regulated by Natural and Non-prescription Health Products Directorate of Health Canada under the Natural Health Products Regulations which came into effect on January 1, 2004. A wide range of health products whose active ingredients exist in nature and are used for self-limiting conditions fall within the category of natural health products including herbal medicines, vitamins and minerals, essential fatty acids and many different traditional medicines including most Proprietary Chinese Medicine. Proprietary Chinese Medicine can be registered under a Class I or Class II or Class III product license (9) (see Figure 2). For example, Proprietary Chinese Medicines which meet the Compendial requirements may submit an application under Class I. The well-defined application guidelines help applicants to determine the right type and class of the product license for which they should apply. If in doubt, applicants can request a Pre-submission Meeting to clarify the type of application required (9). In addition, if after reviewing all relevant regulations, guidance and tools, an applicant is unsure if a product is suitable for licensing as a natural health product, the applicant is encouraged to submit a product classification request prior to submitting a product licensing application. It should be noted that in the Canadian system, at least one “claim” must be approved as part of the licensing application. Recognizing that many Proprietary Chinese Medicines may be used for a wide variety of conditions (representing different claims), the regulatory system, which requires additional documentation for applications in Classes 2 and 3, creates an incentive for applicants to seek approval for a single claim in the lowest Class possible with the least regulatory burden.

Figure 2. The types and classes of Proprietary Chinese Medicines product license application and their requirements in Canada (9).

For Proprietary Chinese Medicines in the “Established medicines category” and “Non-established medicines category” to be registered under Group I, basic documents related to safety, efficacy & quality of the medicine are required for the application. For “Health-preserving medicines” in the “Non-established medicines category,” a long-term toxicity test is required to verify safety because these products are intended for long-term use.

For Proprietary Chinese Medicines in the “Established medicines category” and “Non-established medicines category” to be registered in Group II, further documents supporting their safety and quality are required, such as real-time stability testing, in addition to the basic documents related to the safety, efficacy, and quality of the medicine.

For Proprietary Chinese Medicines under the “Established medicines category,” “Non-established medicines category,” and “New medicines category” to be registered in Group III, comprehensive documents documenting the safety, efficacy, and quality of the medicine are required, such as principal pharmacodynamic studies, clinical trial protocol, and summary report, etc. (8).

The Natural and Non-prescription Health Products Directorate (NNHPD) requests that applicants identify the class under which they are applying in the cover letter of their application according to the definitions. If a Class is not identified correctly in the cover letter, the application will be refused.

By attesting to a monograph, the applicant is confirming that the application meets all of the monograph parameters (Class I) to which the applicant has attested. If applicants are not attesting to full monograph parameters in Class II or III applications, they must ensure that evidence or a rationale for not attesting to the monograph has been provided.

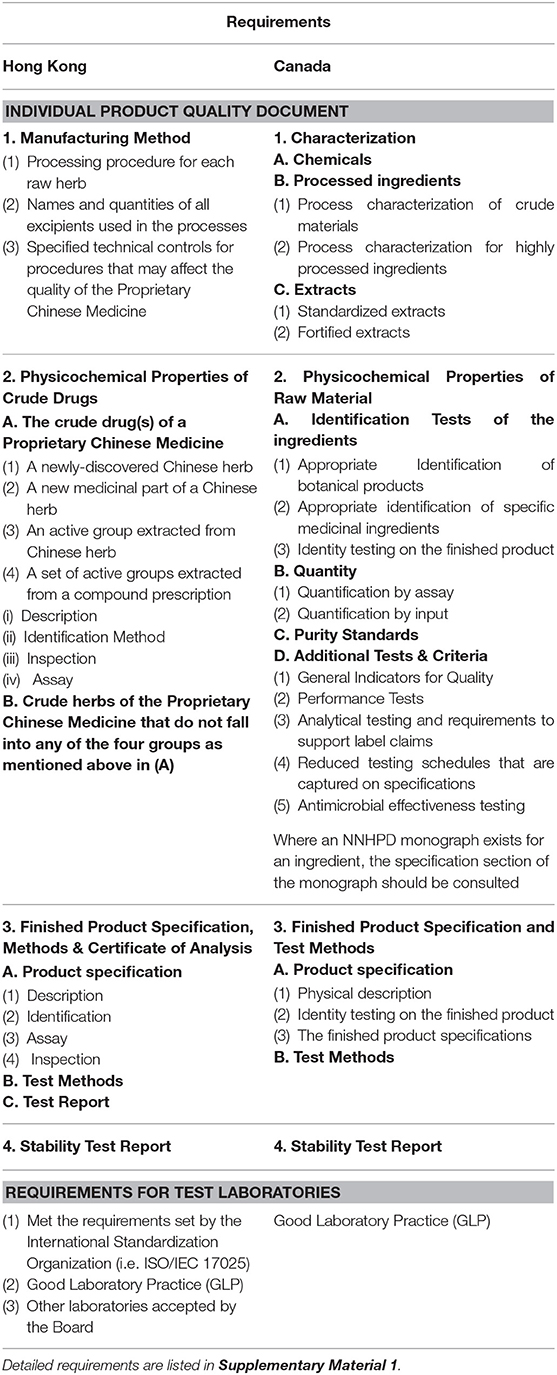

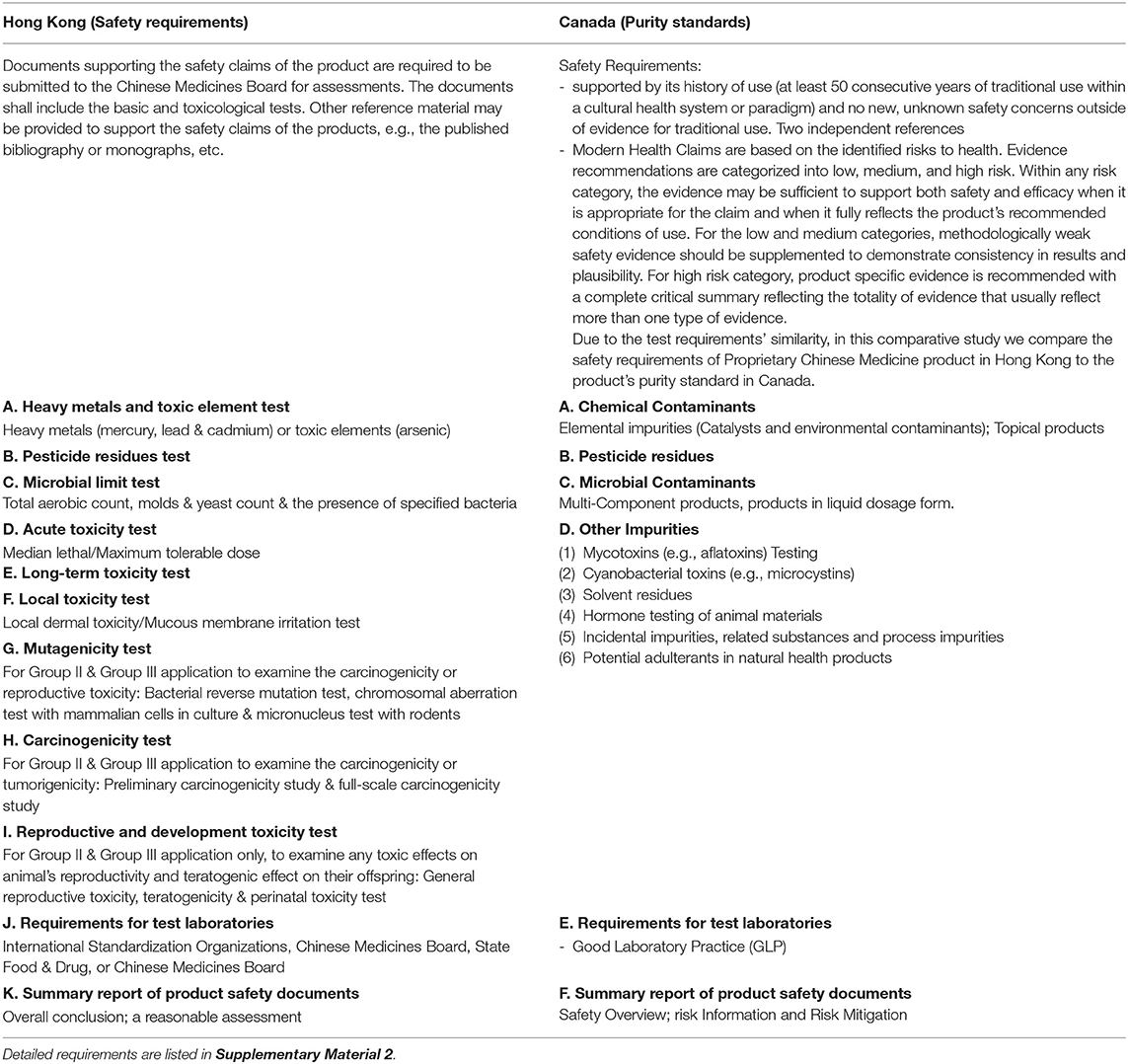

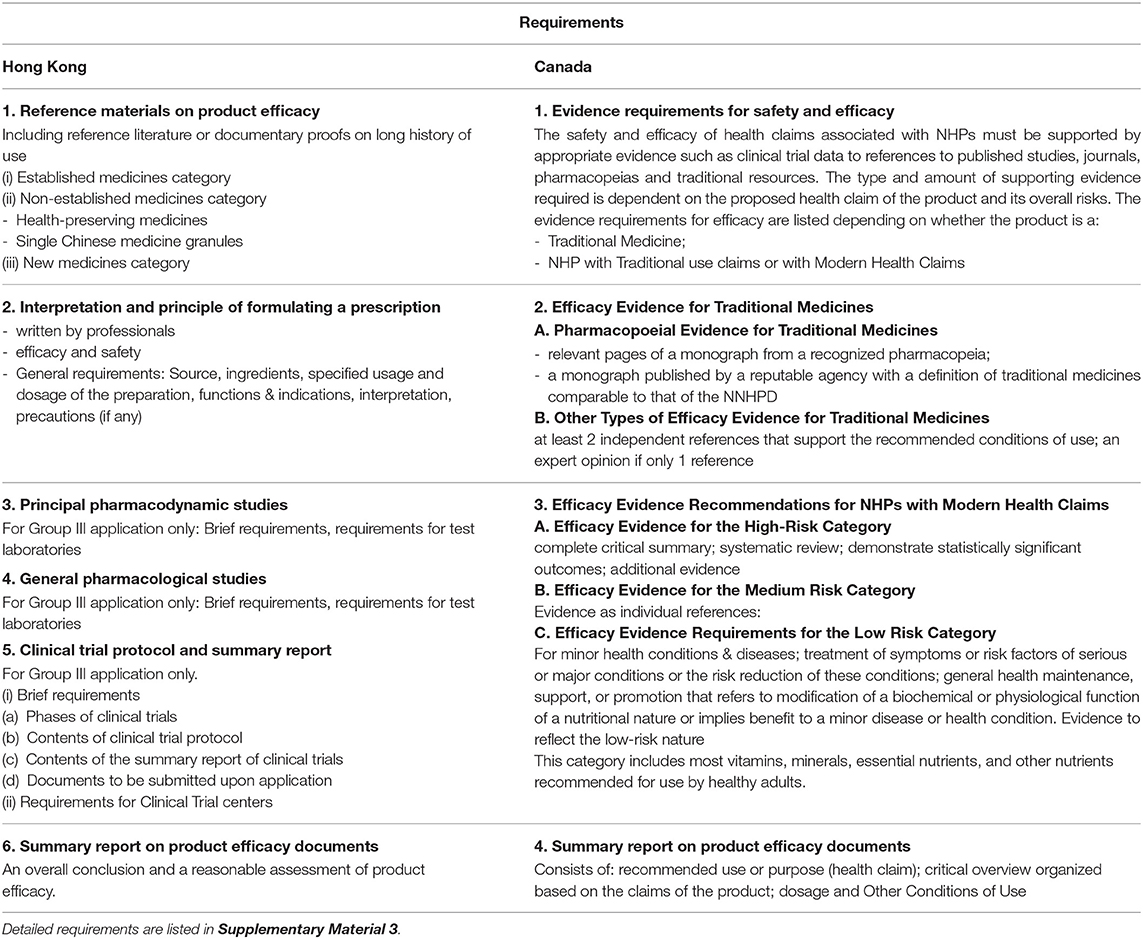

The details of the quality, safety and efficacy requirements for Hong Kong and Canada are listed in Tables 2–4, respectively (10–16).

Table 2. The quality requirements of proprietary Chinese medicines in Hong Kong and Canada (10, 11).

Table 3. The safety requirements and purity standards (under Quality Requirements' guidelines) of proprietary Chinese medicines in Hong Kong and Canada respectively (11, 12).

Table 4. The efficacy requirements of proprietary Chinese medicines in Hong Kong and Canada (11, 13).

Product regulations are the gates defending public health against health products without proven quality, safety, and effectiveness. They should ensure minimum quality of products provide the basis for quick action if post marketing reports identify issues with specific products. Although there is no international standard for regulation for Proprietary Chinese Medicines, the regulatory authorities of Hong Kong and Canada have both adopted a multi-pronged regulatory strategy by dividing applications into groups and classes.

In Hong Kong since registration of Proprietary Chinese Medicines took effect in 2003, more than 2,400 Proprietary Chinese Medicines products have been issued a certificate of registration (17). The registered products not only provide safe Chinese Medicine products to the public, but also have driven ancillary economic activities and created employment opportunities. In 2019, the Hong Kong government established the Hong Kong Chinese Medicine Development Fund with HKD 500 million to promote the development of the Chinese Medicine including support to enhance the overall standard of the industry (18). Manufacturers of Proprietary Chinese Medicines can apply the fund to design or purchase equipment that meets the requirements of Chinese Medicine Manufacturing Quality Management (GMP) (19). Moreover, the government will provide a list of accredited testing institutes to assist manufacturers to meet technical requirements and provide required documentation throughout the registration process (20).

In 2012, Canada established guidelines regarding product license application for traditional medicines including Chinese Medicine. Noteworthily, instead of evidence for ingredients that are already known to be safe and efficacious, Canada's regulatory approach allows assessment of traditional medicines based on efficacy and safety data from relevant traditional healing paradigms (21). However, Proprietary Chinese Medicines that consist of modified or inconsistent Chinese Medicine classical formulae are not eligible for this regulatory pathway and require detailed safety or efficacy documentation. For products that are eligible for Class I, manufacturers must attest that they are manufacturing the product according to the requirements outlined in the Canadian monograph which is based on the Canadian regulatory authority's review of the evidence and determination of what is required to ensure a product is safe and of sufficient quality (22).

ZZKZ Capsule (SFDA approval number Z20020003; NPN approval number 80104354), manufactured by Shuangren Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. of Lonch Group, has been marketed for more than 10 years in China. This Proprietary Chinese Medicine originates from the traditional prescription “Zhizhu Decoction.” ZZKZ Capsule is mainly composed of the following four commonly used Chinese herbs: Rhizoma Atractylodis Macrocephalae (plant Atractylodes macrocephala Koidz.), Fructus Aurantii Immaturus (plant Citrus × aurantium L.), Radix Bupleuri (plant Bupleurum chinense DC.), and Fructus Crataegi (plant Crataegus pinnatifida Bunge). The combination of these four herbs is commonly used to treat spleen deficiency, qi stagnation, liver-stomach disharmony as well as stomach duct and abdomen fullness within the traditional Chinese medicine paradigm (23). To illustrate the similarities and differences between the two regulatory processes, we summarized the requirement of documents for ZZKZ Capsule to register in both Hong Kong (Group I) and Canada (Class I) in Table 5.

Regulation in Hong Kong requires six different safety test reports including heavy metals and toxic elements report, pesticide residues report, microbial limit test report, etc. A summary of evidence including reference materials is required to support product efficacy. In addition, details of the manufacturing method, product specifications and stability testing are required.

In contrast, regulation in Canada requires confirmation that all ingredients are listed in the relevant tables of acceptable Traditional Chinese Medicine Ingredients in the Compendium of Monographs and attestation from the manufacturer that the product is manufactured according to the preparations and methods of processing outlined in one of five specific approved reference pharmacopeias/texts. Similarly, conditions of use and adverse effects identified on the label must be consistent with those outlined in one of the five acceptable reference pharmacopeias (24).

Thus, Hong Kong and Canada take very different approaches to the regulation of the same product which appear to entail very different amounts of effort, time and money on the part of manufacturers who wish to obtain a license to market the same product. This creates a “natural experiment” that would be worth investigating to explore which regulatory approach is the most efficient at supporting the licensing of safe, effective and high quality products available for consumers.

One of the biggest challenges facing manufacturers is the lack of consistency of regulatory requirements globally. In some cases, the documentation required is very similar; in other cases, it varies dramatically. The classification criteria for Proprietary Chinese Medicines registration are different in Hong Kong and Canada but both involve judgements based on historic records of Proprietary Chinese Medicines and include evidence of safety, efficacy and quality. What differs is the type of evidence that must be submitted.

For example, for Proprietary Chinese Medicines that qualify for registration in Group I (Hong Kong), manufacturers are asked to provide safety and efficacy data including product specification, toxicity test report and stability test report. In contrast, for a similar category of products (Class I) in Canada, manufacturers are only required to submit documentation that the Proprietary Chinese Medicines will be manufactured and used in line with traditional data and in strict compliance with all the parameters of a specific NNHPD monograph recognized by the Health Canada. It includes the information from Pharmacopeia published by a reputable agency (e.g., the Pharmacopeia of the People's Republic of China or translated version of the Drug Standard of People' Republic of China), ensures that there are sufficient data to demonstrate the quality, safety and efficacy of the Proprietary Chinese Medicines.

Applications for Proprietary Chinese Medicines that fall into the “non-established” or “new medicines” category in Hong Kong, and under the “modern health claims” category in Canada, will be assessed under the requirements outlined for Group III in Hong Kong and under requirements of Class II or Class III in Canada. The requirements in the two countries for these kinds of products also differ. For example, in Hong Kong, clinical trials with the new indications will required to be conducted in the Hong Kong population before registration. In Canada, depending on the health risk of the Proprietary Chinese Medicine, the claimed therapeutic functions or efficacy must be supported by evidence from the health care literature (including traditional Chinese medicine literature), by research studies assessing product efficacy including clinical trials, and/or a complete critical summary of a systemic review reflecting the totality of evidence.

The safety requirements for chemical contaminants such as heavy metals and toxic elements, pesticide residues and microbial contaminants are similar in Hong Kong and Canada, but there are important differences (Supplementary Material 2). For example, Hong Kong has put emphasis on the some toxicity tests including the mutagenicity test and the reproductive and development toxicity test, as well as dose related toxicity tests; whereas Canada has more emphasis on testing for impurities that may cause toxicity, such as mycotoxins, solvent residues and incidental impurities, related substances and process impurities. Canada also has listed clear guidelines on the performance tests of the finished products (11, 12). These differences significantly increase the time and cost burden to manufactures hoping to license/register products in multiple jurisdictions.

Finally, Proprietary Chinese Medicines manufacturers raise concerns about inconsistent requirements from regulatory authorities with respect to packaging and labeling (25). In 2020, the regulatory body in Hong Kong updated guidelines regarding labels and package inserts of Proprietary Chinese Medicines (26, 27) while requirements on labeling and packaging for Proprietary Chinese Medicines are comparatively less specified in Canada (28).

As a component of traditional medicine, Proprietary Chinese Medicines create unique challenges for regulators in countries outside those where the products are traditionally used due to their complex nature and use within health paradigms that differ from Western biomedicine. It appears that safety and quality parameters may be the easiest to think about harmonizing as these parameters may be the least impacted by health paradigm differences. Agreement across regulators regarding which tests are required/acceptable to prove safety and quality would significantly increase the efficiency of the regulatory process for both manufacturers and regulators (Supplementary Material 3). With the development of global standards on submission, review and authorization of these products, manufacturers could submit the same testing data to multiple regulatory agencies. And regulatory agencies could consider fast tracking the review of products that were already approved in other countries that share similar standards.

Knowledge of the Proprietary Chinese Medicines product license application procedure and requirements in Hong Kong and Canada, and understanding their similarity and differences will enable the applicants to develop an appropriate strategy for gaining product approval. Exploring ways to harmonize the regulatory process has potential to benefit manufacturers, regulators, and patients by increasing efficiency and decreasing costs.

LZ and HB shared the idea and supervised the study. WL collected policy documents from regulatory bodies and added the figures and tables. All authors were involved in drafting and revising the manuscript, reviewed, and approved the final manuscript.

This work was supported by a Visiting Professorship fund from the Leslie Dan Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Toronto, Faculty Research Fund (FRG2/16-17/094) from Hong Kong Baptist University and Special Research on Modernization of Traditional Chinese Medicine in the National Key Research and Development Program in China's 13th Five-Year Plan Demonstrative Research International Clinical Study of Zhizhu Kuanzhong Capsule (2017YFC1703703).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

We thank Ms. Sonia Low for translation and collection all the government's documents.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmed.2021.617625/full#supplementary-material

NHP, Natural Health Product; NNHPD, Natural and Non-prescription Health Products Directorate; NPN, (Canada) Natural Product Number; SFDA, (Mainland China and Hong Kong) State Food and Drug Administration; ZZKZ, Zhizhu Kuanzhong.

1. Franklin JM, Glynn RJ, Martin D, Schneeweiss S. Evaluating the use of nonrandomized real-world data analyses for regulatory decision making. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2019) 105:867–77. doi: 10.1002/cpt.1351

2. Eichler HG, Baird LG, Barker R, Bloechl-Daum B, Børlum-Kristensen F, Brown J, et al. From adaptive licensing to adaptive pathways: delivering a flexible life-span approach to bring new drugs to patients. Clin Pharmacol Ther. (2015) 97:234–46. doi: 10.1002/cpt.59

3. World Health Organization. Traditional, Complementary and Integrative Medicine. (2020). Available online at: https://www.who.int/health-topics/traditional-complementary-and-integrative-medicine#tab=tab_1 (accessed 6 October, 2020).

4. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Guidance Notes on “How to Classify Products as Proprietary Chinese Medicines”. (2011). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/class_guide_trade_ref_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

5. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Registration of Proprietary Chinese Medicines. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/eng/#main_down02.htm (accessed 6 October, 2020).

6. Health Canada. Natural Health Products. (2020). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/natural-non-prescription.html (accessed 6 October, 2020).

7. Government of Canada. Natural Health Products Regulations. (2020). Available online at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/regulations/sor-2003-196/page-1.html (accessed 6 October, 2020).

8. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Registration of Proprietary Chinese medicines: Application Handbook. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/reg_handbook_bfver_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

9. Health Canada. Natural Health Products Management of Applications Policy. (2019). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/documents/services/drugs-health-products/natural-health-products/legislation-guidelines/guidance-documents/management-product-licence-applications-attestations/nhp-map-2019-guidance-document-eng.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

10. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Registration of Proprietary Chinese Medicine: Product Quality Documents Technical Guidelines. (2004). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/guide_quality_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

11. Health Canada. Quality of Natural Health Products Guide. (2015). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/prodnatur/legislation/docs/eq-paq-eng.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

12. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Registration of Proprietary Chinese Medicine: Product Safety Documents Technical Guidelines. (2004). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/guide_save_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

13. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Registration of Proprietary Chinese Medicine: Product Efficacy Documents Technical Guidelines. (2004). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/guide_work_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

14. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Appendices: Product Quality Documents Technical Guidelines. (2004). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/guide_quality_n_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

15. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Appendices: Product Safety Documents Technical Guidelines. (2004). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/guide_save_n_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

16. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Appendices: Product Efficacy Documents Technical Guidelines. (2004). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/guide_work_n_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

17. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Lists of Applications for Proprietary Chinese Medicine Registration. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/eng/#main_listpcm_2018.htm (accessed 6 October, 2020).

18. The Government of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region. Press Releases: Chinese Medicine Development Fund launched today. (2019). Available online at: https://www.info.gov.hk/gia/general/201906/25/P2019062500526.htm?fontSize=1 (accessed 6 October, 2020).

19. Chinese Medicine Development Fund. Proprietary Chinese Medicine Quality and Manufacturing System Enhancement Funding Scheme (A2). (2020). Available online at: https://www.cmdevfund.hk/content-en.php?mid=3&id=17 (accessed 6 October, 2020).

20. Chinese Medicine Regulatory Office of the Department of Health. Government Chinese Medicines Testing Institute (GCMTI). (2020). Available online at: https://www.cmro.gov.hk/html/eng/GCMTI/org_chart.html (accessed 6 October, 2020).

21. Health Canada. Pathway for Licensing Natural Health Products used as Traditional Medicines, Version 1.0. (2012). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/content/dam/hc-sc/migration/hc-sc/dhp-mps/alt_formats/pdf/prodnatur/legislation/docs/tradit-eng.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

22. Health Canada. Compendium of Monographs. (2009). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/natural-non-prescription/applications-submissions/product-licensing/compendium-monographs.html (accessed 6 October, 2020).

23. Wen MY, Zhang FC, Wang YJ. Effect of Zhizhu Kuanzhong Capsules on treatment of functional dyspepsia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Chin J Integr Med. (2019) 25:625–30. doi: 10.1007/s11655-018-2846-0

24. Health Canada. Traditional Chinese Medicine Ingredients (TCMI). (2015). Available online at: http://webprod.hc-sc.gc.ca/nhpid-bdipsn/atReq.do?atid=tcm&lang=eng (accessed 6 October, 2020).

25. Office of The Ombudsman HK. Direct Investigation Report: Government's Regulation of Proprietary Chinese Medicine. (2018). Available online at: https://ofomb.ombudsman.hk/abc/files/2018_12_FR___3.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

26. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Guidelines on Labels of Proprietary Chinese Medicines. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/gl_pcm_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

27. Chinese Medicine Council of Hong Kong. Guidelines on Package Inserts of Proprietary Chinese Medicines. (2020). Available online at: https://www.cmchk.org.hk/pcm/pdf/gp_pcm_e.pdf (accessed 6 October, 2020).

28. Health Canada. Forward Regulatory Plan 2019-2021: Self-Care Framework. (2020). Available online at: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/corporate/about-health-canada/legislation-guidelines/acts-regulations/forward-regulatory-plan/plan/self-care-framework.html (accessed 6 October, 2020).

Keywords: proprietary Chinese medicine, traditional Chinese medicine, herbal medicine, natural health products, Chinese medicine regulation, Chinese medicine registration, product license application regulation, Zhizhu Kuanzhong

Citation: Zhong LLD, Lam WC, Lu F, Tang XD, Lyu A, Bian Z and Boon H (2021) A Comparative Study for License Application Regulations on Proprietary Chinese Medicines in Hong Kong and Canada. Front. Med. 8:617625. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2021.617625

Received: 10 November 2020; Accepted: 03 February 2021;

Published: 09 March 2021.

Edited by:

Mette Due Theilade Thomsen, PIP Adviser, DenmarkReviewed by:

Lawrence Liberti, Centre for Innovation in Regulatory Science, United KingdomCopyright © 2021 Zhong, Lam, Lu, Tang, Lyu, Bian and Boon. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Linda L. D. Zhong, bGR6aG9uZzAzMDVAZ21haWwuY29t; Heather Boon, aGVhdGhlci5ib29uQHV0b3JvbnRvLmNh

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.