95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mech. Eng. , 18 March 2022

Sec. Biomechanical Engineering

Volume 8 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmech.2022.849283

This article is part of the Research Topic The Mechanobiology of Collagen Remodeling in Health and Disease View all 5 articles

Chronic joint pain is a major health problem that can result from abnormal loading of the innervated ligamentous capsule that surrounds synovial joints. The matrix metalloproteinases-1 (MMP-1) and MMP-9 are hypothesized pain mediators from stretch-induced injuries since they increase in pathologic joint tissues and are implicated in biomechanical and nociceptive pathways that underlay painful joint injuries. There is also emerging evidence that MMP-1 and MMP-9 have mechanistic interactions with the nociceptive neuropeptide substance P. Yet, how a ligament stretch induces painful responses during sub-failure loading and whether MMP-1 or MMP-9 modulates nociception via substance P are unknown. We used a neuron–fibroblast co-culture collagen gel model of the capsular ligament to test whether a sub-failure equibiaxial stretch above the magnitude for initiating nociceptive responses in neurons also regulates MMP-1 and MMP-9. Pre-stretch treatment with the MMP inhibitor ilomastat also tested whether inhibiting MMPs attenuates the stretch-induced nociceptive responses. Because of the role of MMPs in collagen remodeling, collagen microstructural kinematics were measured in all tests. Co-culture gels were incubated for one week in either normal conditions, with five days of ilomastat treatment, or with five days of a vehicle control solution before a planar equibiaxial stretch that imposed strains at magnitudes that induce pain in vivo and increase nociceptive modulators in vitro. Force, displacement, and strain were measured, and polarized light imaging captured collagen fiber kinematics during loading. At 24 h after stretch, immunolabeling quantified substance P, MMP-1, and MMP-9 protein expression. The same sub-failure equibiaxial stretch was imposed on all co-cultures, inducing a significant re-organization of collagen fibers (p ≤ 0.031) indicative of fiber realignment. Stretch induces a doubling of substance P expression in normal and vehicle-treated co-cultures (p = 0.038) that is prevented with ilomastat treatment (p = 0.114). Although MMP-1 and MMP-9 expression are unaffected by the stretch in all co-culture groups, ilomastat treatment abolishes the correlative relationships between MMP-1 and substance P (p = 0.002; R2 = 0.13) and between MMP-1 and MMP-9 (p = 0.007; R2 = 0.11) that are detected without an inhibitor. Collectively, these findings implicate MMPs in a painful ligamentous injury and contribute to a growing body of work linking MMPs to nociceptive-related signaling pathways and/or pain.

Pathologies of synovial joints are a leading cause of chronic pain and present a substantial socioeconomic burden (IBM Corporation, 2019; National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2020). The bilateral facet joints of the spine are among the most common sources of neck and lower back pain (Hogg-Johnson et al., 2008; Perolat et al., 2018). As with other synovial joints, pain can result from an inciting injury to the innervated tissues of the joint or from damage that accumulates over time, compromising the biomechanical properties of the articular tissues (Elliott et al., 2009; Loeser et al., 2012; Sperry et al., 2017). In either case, loading of the joint’s ligamentous capsule, in particular, can initiate pathophysiological cascades that lead to pain by activating the innervating nociceptive fibers embedded in the predominantly type-I collagen matrix that makes up the ligament (Lu et al., 2005; Kallakuri et al., 2008; Lee et al., 2008).

When the facet capsule is stretched beyond its physiologic limit, a variety of physiological responses in the afferent neurons that innervate the ligamentous capsule are altered. Those stretch-induced physiological responses are directly related to the magnitude of the strain experienced by the ligament during its mechanical stretch. For example, the extent of pain is modulated by the magnitude of strain across the facet capsular ligament (Pearson et al., 2004; Dong et al., 2012; Ita et al., 2017a; Kartha et al., 2018). The same graded response is also observed with the amount of neurotransmitters and nociceptive pain-related molecules expressed by neurons embedded in collagen gels undergoing similar loading conditions (Zhang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017) and the extent of neuronal activity generated after capsular stretch (Chen et al., 2006; Quinn et al., 2010a; Quinn et al., 2010b). Although facet joint stretch-induced pain symptoms in rats depend on facet capsular strain magnitude (Lee and Winkelstein, 2009; Dong and Winkelstein, 2010; Dong et al., 2012), pain is not further increased if the capsule is stretched to failure (Lee et al., 2008; Winkelstein and Santos, 2008). Despite the counterintuitive finding that a more severe injury (i.e., ligament failure) in vivo is less detrimental than a mechanical injury in the sub-failure regime (Lee et al., 2008; Winkelstein and Santos, 2008), those behavioral studies demonstrate that afferent fiber signaling is requisite for mechanotransduction in the capsular ligament and necessary for both the development and maintenance of injury-induced pain (Dong et al., 2012; Crosby et al., 2015; Ita et al., 2017a). Despite findings in animal models showing that sub-failure mechanical injury can result in pain, the mechanisms by which such sub-failure facet capsule stretch induces pain are not well defined.

Neuronal physiological responses induced by a sub-failure mechanical injury of capsular ligaments may be directly or indirectly related to the abnormal kinematics and/or restructuring of the collagen network in which the afferent nerve fibers are embedded. For example, collagen fiber alignment relates to regional neuronal expression of phosphorylated extracellular signal-regulated kinase (pERK), an indicator of signal transduction caused by a noxious stimuli (Obata and Noguchi, 2004; Zhang et al., 2016). Furthermore, quantitative polarized light imaging (QPLI) (Tower et al., 2002; Quinn and Winkelstein, 2008; Sander et al., 2009) showed that the neuronal expression of pERK increased at the same strain threshold (∼11.3%) as collagen fiber re-organization occurs under tensile load in the same system (Zhang et al., 2016). Those findings support that collagen fiber re-orientation and neuronal dysfunction are related, which is further supported by integrin–collagen binding sites being directly implicated in strain-induced increases in substance P in a dorsal root ganglia (DRG)–collagen gel model (Zhang et al., 2017). Although the kinematics of collagen fibers have been implicated in stretch-induced neuronal signaling (Zhang et al., 2016), how the network microstructure responds to sub-failure loading during biaxial loading and whether microstructural kinematics affect neuronal responses are not fully understood, despite collagen fiber kinematics depending on loading modality (Sander et al., 2011; Ban et al., 2017).

Both matrix metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) and MMP-9 are possible mediators of stretch-induced nociception in the sub-failure regime. They both increase in the tissues of painful synovial joints, and they both contribute biomechanically and biochemically to disease progression (Cohen et al., 2007; Haller et al., 2015). For example, the collagenase MMP-1 is well known for degrading triple-helical type-I collagen (Visse and Nagase, 2003), which can alter whole joint mechanics (Otterness et al., 2000; Varady and Grodzinsky, 2016) and is increasingly being recognized for its role in extracellular signaling cascades (Conant et al., 2002; Conant et al., 2004; Boire et al., 2005; Allen et al., 2016). Given that another member of the collagenase family, MMP-8, remodels collagen on the fibril level (Flynn et al., 2010), it is also possible that MMP-1 acts within the capsular ligament’s network by a similar mechanism and may reconstruct the collagen microstructure and have subsequent effects on afferent fibers (Zhang et al., 2016). MMP-1 activates and stimulates the release of MMP-9 (Conant et al., 2002), which is upstream of pain signaling pathways and sensitizes DRG neurons rapidly after nerve injury (Kawasaki et al., 2008). Furthermore, MMP-9 is known to cleave the neuropeptide substance P, which makes it a direct and indirect mediator of neuronal transmission of noxious stimuli (Diekmann and Tschesche, 1994; Backstrom and Tökés, 1995; Rawlings et al., 2014). Substance P is found in the nerve fibers innervating human facet joint capsules and plays a critical role in transmitting nociceptive signals from the periphery to the brain via peptidergic ascending pathways (Kallakuri et al., 2004; Braz et al., 2005). Therefore, it is possible that MMP-1 and/or MMP-9 modulate nociception via their mechanistic interactions with substance P, yet this is unknown.

In fact, our group has recently established a connection between collagenases and substance P during pain-like behavioral states in rats (Ita et al., 2020a; Ita et al. submitted). Intra-articular bacterial collagenase, an enzyme that shares extracellular matrix (ECM) substrates with MMP-1 (Fields, 2013), increases both of the substance P and MMP-1 protein expression in DRG neurons and the spinal cord along with sustained behavioral sensitivity when injected into the spinal facet joint (Ita et al., 2020b). Furthermore, intra-articular MMP-1 alone is sufficient to induce sustained behavioral sensitivity while increasing the levels of substance P in DRG neurons and the spinal cord (Ita et al. submitted). We have also demonstrated in our DRG–fibroblast-like synoviocyte (FLS) co-culture collagen gel model of the capsular ligament that a tensile stretch to failure increases neuronal MMP-1, MMP-9, and substance P expression, concomitantly (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019b). Together, those studies show that MMP-1 alone can induce pain-like behavioral sensitivity and suggest a regulatory role for MMP-1 in mechanically evoked neuronal dysregulation. Furthermore, the parallel increases in MMP-1 and MMP-9 support a possible mechanistic relationship between them that is established by prior clinical work in a patient population with painful joint diseases (Ita et al., 2021). However, although failure stretch induces strains that are sufficient to modulate MMP-1 and MMP-9 (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019b), whether a less severe sub-failure stretch affects MMPs and/or substance P is unknown despite such a loading regime being relevant for pain (Lee and Winkelstein, 2009; Dong and Winkelstein, 2010; Dong et al., 2012). Moreover, although prior work suggests possible mechanistic relationships between MMPs and substance P (Conant et al., 2002; Haller et al., 2015; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019b; Ita et al., 2020a; Ita et al., 2021), neither MMP-1 nor MMP-9 has been examined or implicated in mechanically-induced nociception in capsular ligaments.

The primary goal of this study was to define the effects of a sub-failure equibiaxial stretch on substance P, MMP-1, and MMP-9 protein expression in neurons and to contextualize those responses relative to the surrounding collagen microstructural kinematics. In addition, MMP inhibition was used to probe the role of MMPs in neuronal dysregulation and the kinematic behavior of collagen fibers. We utilized our DRG-FLS co-culture collagen gel system that mimics capsular ligaments (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a) to test the hypothesis that sub-failure stretch above the magnitude that increases substance P expression in peripheral neurons also regulates MMP-1 and MMP-9 expression in those peripheral neurons. The magnitude of stretch imposed on the gels was chosen to generate strains exceeding the ∼11% strain threshold (at 1–7%/sec) that has been identified in other neuron–collagen gels to induce an increase in substance P and pERK expression in neurons (Zhang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018a). The sub-failure stretch was imposed equibiaxially since biaxial loading configurations better mimic the physiological boundaries and constraints of the facet joint’s ligament–bone complex and to simulate the complex loading profiles of the facet capsular ligament in vivo (Jaumard et al., 2011; Dong et al., 2012; Ita et al., 2017b). QPLI was integrated with mechanical testing to quantify network microstructure of the co-culture collagen gels under load in the sub-failure regime.

Based on those findings and the literature suggesting molecular interactions exist between substance P and each of MMP-1 and/or MMP-9 (Diekmann and Tschesche, 1994; Conant et al., 2002; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019b; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a), we utilized the broad-spectrum MMP inhibitor ilomastat to probe whether inhibiting MMP-1 and MMP-9 decreases the stretch-induced substance P expression in DRG neurons during the same experimental design as described previously. Ilomastat is a hydroxamate-based inhibitor that competitively inhibits substrate binding at the Zn2+-containing catalytic domain (Grobelny et al., 1992; Galardy et al., 1994; Vandenbroucke and Libert, 2014). It acts on MMPs where the Zn2+-containing catalytic domain is preserved but has different Ki inhibitor dissociation constants, an indication of inhibitor potency, across MMPs (Galardy et al., 1994). As such, by tuning the concentration, the inhibitor can be made more selective and less broad spectrum. In this study, a 25 nM dose of ilomastat was used to optimize MMP-1 and MMP-9 inhibition while preventing undesired inhibition of other MMPs with higher Ki values (i.e., MMP-2 and MMP-3) (Grobelny et al., 1992). Since collagenases degrade the triple-helical collagen that composes most of the capsule’s ECM and because collagen degradation may cause tissue laxity and alter the collagen fiber microstructure (van Osch et al., 1995; Otterness et al., 2000; Varady and Grodzinsky, 2016), it is possible that ilomastat may disrupt any effect of load-induced MMP-1 on the collagen matrix. As such, we also quantified collagen fiber kinematics using QPLI with ilomastat inhibition to assess whether inhibiting MMP-1 alters the microstructural re-organization of collagen fibers during a sub-failure mechanical exposure.

DRG–FLS co-culture gels (n = 36) were fabricated and allocated to an equibiaxial stretch under normal culture conditions (naïve n = 12); equibiaxial stretch after five days of incubation with an ilomastat inhibitor (inhibitor n = 14) or equibiaxial stretch after five days of incubation with dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) was taken as a vehicle control group since the ilomastat was dissolved in DMSO (vehicle n = 10). Half of the co-cultures from each group underwent an equibiaxial stretch, and the other half served as unstretched controls to account for the effect of each of the stretch and the incubation procedures at five days before the testing.

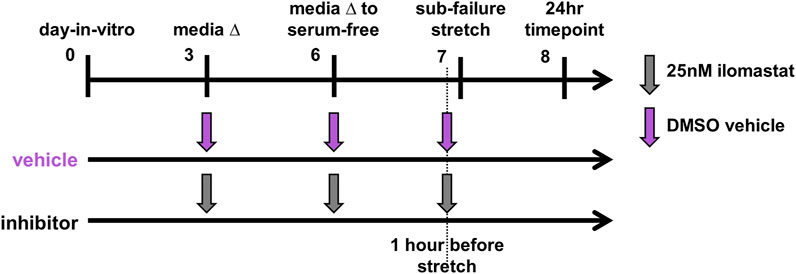

The culture media of co-culture gels receiving inhibitor were treated at each of day-in-vitro (DIV) 3, DIV6, and DIV7 with a 25 nM dose of ilomastat (Figure 1). Doses added to the culture media on DIV7 before the sub-failure stretch were given one hour before testing (Figure 1). The 25 nM ilomastat dose (GM6001; Millipore Sigma; Burlington, MA) was prepared from a 2.5 mM stock solution in DMSO (5 μL) dissolved into sterile cell culture H2O to a concentration of 0.5 μM (Conant et al., 2004; Rogers et al., 2014); 25 μL of the 0.5 μM dilution was then added to the media to achieve a final concentration of 25 nM. The matched vehicle group was prepared accordingly with DMSO since the purchased stock ilomastat was stored in DMSO. The DMSO vehicle was prepared identically to the ilomastat with sterile DMSO (Invitrogen; Waltham, MA) dissolved in sterile H2O to a concentration of 25 nM.

FIGURE 1. Study design for co-culture gels receiving the ilomastat inhibitor (n = 14) or DMSO vehicle (n = 10). Co-cultures received either the ilomastat inhibitor (25 nM) or DMSO vehicle into their media at day-in-vitro 3 and 6 and one hour before an equibiaxial stretch on day-in-vitro 7. All co-cultures were fixed for immunolabeling assays 24 h after sub-failure stretch.

All cells were harvested from Sprague Dawley male rats under University of Pennsylvania IACUC-approved conditions and using sterile procedures as previously described (Zhang et al., 2018a; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a). In brief, DRGs from all spinal levels were taken from embryonic day 18 Sprague Dawley rats obtained from the CNS Cell Culture Service Center of the Mahoney Institute of Neuroscience at the University of Pennsylvania. DRGs were dissected using fine forceps to remove individual DRG explants after exposing the rat’s spine and removing the spinal cord (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a). In a monocellular, isolated culture, a DRG feeding medium consisted of Neurobasal feeding medium supplemented with 1% GlutaMAX, 2% B-27, 1% fetal bovine serum (FBS), and 10 ng/ml 2.5S nerve growth factor (all from Thermo Fisher; Waltham, MA) and 2 mg/ml glucose, 10 mM FdU, and 10 mM uridine (all from Sigma-Aldrich) (Zhang et al., 2018a).

FLS were harvested from both hind knees of a sexually mature adult rat by finely dissecting the capsular tissue surrounding the knee joints and dicing the isolated tissue (Saravanan et al., 2014; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a). The diced tissue from both knee capsules was incubated together in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium (DMEM; Thermo Fisher) with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), 1% penicillin–streptomycin (P–S) (Thermo Fisher), and 2 mg/ml crude bacterial collagenase (C0130; Sigma-Aldrich) for six hours at 37°C under gentle agitation (Saravanan et al., 2014; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a). Digested tissue was filtered with a 70 μm cell strainer, spun down at 300 g for five minutes, and resuspended in DMEM with 10% FBS and 1% P–S. The culture medium was changed every other day, and cells were passaged at 90% confluence.

Collagen gels were fabricated with rat tail type-I collagen (2 mg/ml; Corning Inc.; Corning, NY) cast in 12-well plates (1ml/well) with re-suspended FLS from passages three–five (∼5 × 104 cells/mL) (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a) and cultured for one day in DMEM media. At DIV1, DRGs (6-10/gel) were seeded onto the gel surface in 100 μL in supplemented Neurobasal medium. After allowing 24 h for DRGs to attach, the media were changed to supplemented Neurobasal media with 5% FBS that was optimized for the DRG-FLS co-culture system (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a). Co-cultures underwent a full media change on DIV3. On DIV6, gels were triple-rinsed with 1X phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) and an additional layer of 2 mg/ml collagen (125 μL) was added to encapsulate the DRGs (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a). After the PBS washes, the media were changed to supplemented Neurobasal media without serum (Attia et al., 2014). On DIV7, gels were cut into a cruciform shape with each arm having the dimensions of 6.25 mm by 8 mm (Zhang et al., 2017) and marked with a grid of fiducial markers defining elements using black India ink (Koh-I-Noor) to enable mechanical testing (Figure 2A).

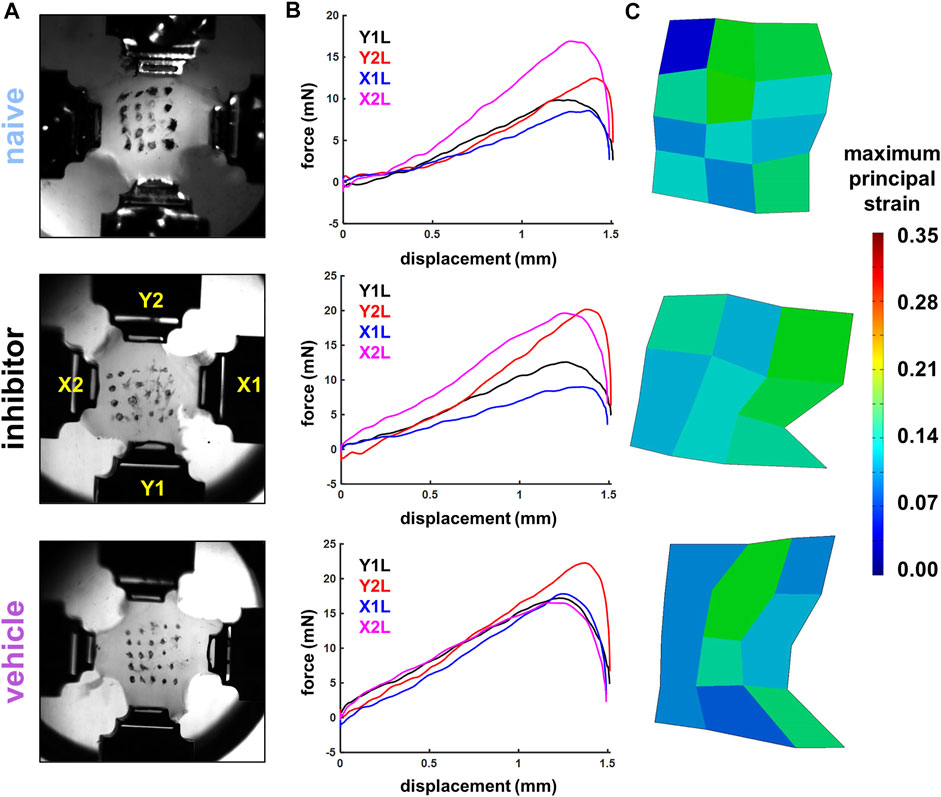

FIGURE 2. Exemplary high-speed images (A), force-displacement curves (B), and maximum principal strain surface maps (C) from stretched co-culture gels showing gels from the naïve (gel S18), inhibitor (gel S72), and vehicle (gel S54) groups. Image stills in (A) show gels affixed in four actuator grips in the image still captured immediately before the peak force was achieved, which was identified as the maximum magnitude of force during a gel stretch recorded by any of the four load cells (B). Strain maps in (C) show that a 1.5 mm/arm equibiaxial stretch imposes similar average (S18: 9.21%; S72: 10.79%; S54: 9.21%) and maximum surface principal strains (S18: 17.35%; S72: 17.26%; S54: 18.09%) across the groups.

The arms of the gels were loaded into grips attached to actuators with 500 g load cells immersed in a 37°C 1X PBS bio-bath (Figure 2A). Gels were pre-loaded until taut (less than 2 mN/arm) and then stretched in equibiaxial tension for one loading cycle at 4 mm/s to a displacement of 1.5 mm for each arm in a planar testing machine (574LE2; Test Resources; Shakopee, MN) to impose strains at magnitudes that induce pain in vivo and also increase nociceptive modulators in vitro (Dong et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017). The mechanical system was integrated with a polarized light imaging system and high-speed cameras (Phantom-v9.1; Vision Research Inc.; Wayne, NJ) that acquired collagen alignment maps and tracked fiducial marker coordinates during loading (Tower et al., 2002; Quinn and Winkelstein, 2008; Quinn et al., 2010a). Force and displacement data were acquired at 200 Hz from each arm, and high-speed cameras (500 Hz) tracked the grid of fiducial markers to enable strain calculations (Figure 2) (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a).

Immediately after loading, the gels were released from the grips, washed with 1X PBS with 1% P–S, and transferred to a pre-warmed serum-free supplemented Neurobasal culture media with 1% P–S (Zhang et al., 2017). After 24 h, the gels were washed with 1X PBS and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde (PFA) for immunolabeling. Protein expression was assayed 24 h after the stretch to allow for the MMP transcriptional and/or post-translational regulation that occurs hours-to-days after the initiation of mechanical loading in cell-seeded constructs (Kessler et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2005; Petersen et al., 2012). Matched gels for each group (naïve n = 6; inhibitor n = 7; vehicle n = 5) underwent the same protocol but did not undergo any stretch and served as unloaded controls.

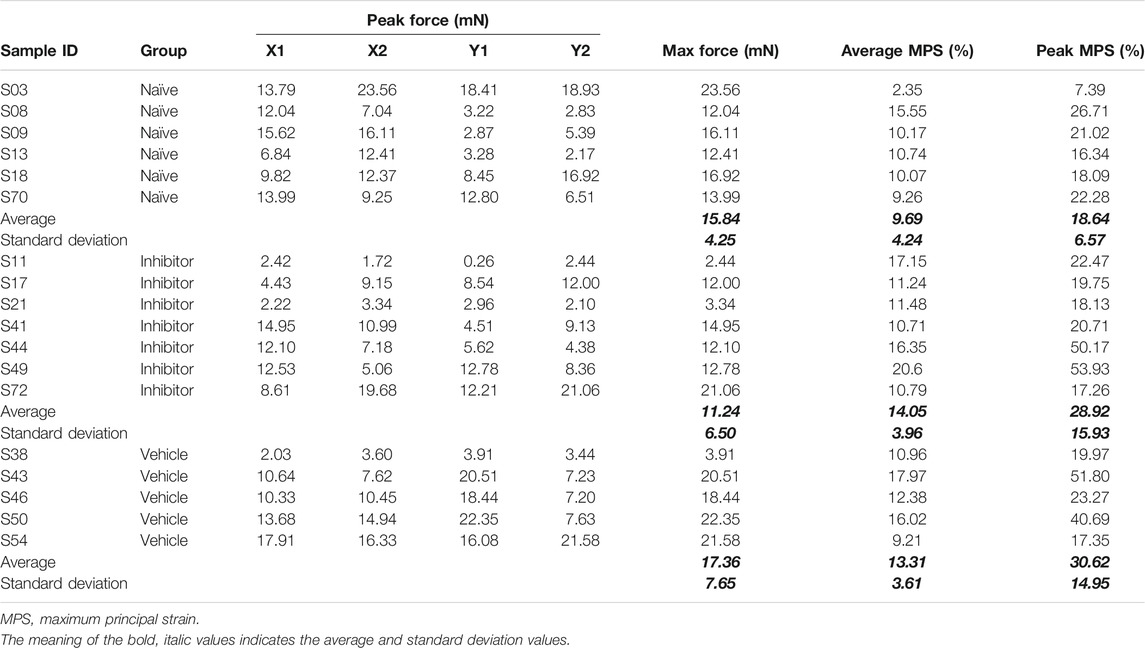

Force data were filtered using a 10-point moving average filter (Zhang et al., 2018a; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a); the maximum force sustained during a gel stretch that was recorded by any of the four load cells (i.e., arms; X1, X2, Y1, or Y2; Figure 2A) was taken as the peak force for that gel (Table 1). The marker locations in the unloaded reference image and the image immediately after the peak force were digitized with FIJI software (NIH) (Schindelin et al., 2012). Positional data for the markers were processed in LS-DYNA (Livermore Software Technology Corp.; Livermore, CA) to calculate the maximum principal strain (MPS) for each element of each gel (Figure 2C) (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a); each group of four nodes designated by fiducial markers was designated as an element. The largest magnitude MPS sustained in any of the elements for each gel was taken as the peak MPS for that gel, and the average MPS of all elements was also calculated (Table 1).

TABLE 1. Summary of force and maximum principal strain (MPS) recorded during equibiaxial sub-failure stretch. The peak force recorded from each load cell is separately detailed (X1, X2, Y1, and Y2).

Pixel-wise fiber alignment maps were created using 20 consecutive high-speed images acquired both before stretch (at unloaded reference) and immediately prior to the time of peak force using a custom script based on a harmonic equation in MATLAB (R2018; MathWorks Inc., Natick, MA) (Tower et al., 2002; Quinn and Winkelstein, 2008; Quinn et al., 2010a). Using fiber angle distributions, collagen organization was quantified by the circular variance (CV) of the spread of fiber angles, with a higher CV indicating a larger spread in the distribution of collagen fiber angles (Zhang et al., 2018a).

To visualize the protein expression of substance P, MMP-1, and MMP-9, fixed co-culture gels were blocked in 1X PBS with 10% goat serum and 0.03% Triton-X and incubated overnight at 4°C with primary antibodies to substance P (1:250, Neuromics Inc.; Minneapolis, MN; Cat# GP14103; RRID:AB_2629484), MMP-1 (1:400, Proteintech; Rosemont, IL; Cat# 10371-2-AP; RRID:AB_2297741), and MMP-9 (1:250, Thermo Fisher; Cat# MA5-15886; RRID:AB_11157246). Gels were then washed four times with 1X PBS and incubated with the secondary antibodies goat anti-guinea pig 633, goat anti-rabbit 488, and goat anti-mouse 568 (all Alexa Fluor 1:1000; Invitrogen) and DAPI (1:750, Thermo Fisher). Following incubation in secondary antibodies, gels were washed three times with 1X PBS and one time with deionized water and then cover-slipped with a fluoro-gel mounting medium (Electron Microscopy Sciences; Hatfield, MA). All washes were performed for 10 min each on a rocker plate. Gels undergoing the same protocol except with no primary antibodies were included as negative controls to verify the specificity of each antibody throughout the imaging process.

Confocal images (1024 × 1024 pixels) were acquired on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope (Leica Microsystems; Wetzlar, Germany) using a ×20 objective (HC PL APO CS2 20x/0.75 dry; Leica Microsystems). All images were acquired at 400 Hz with a 2.5 airy unit pinhole size resulting in a total pixel dwell time of 600 ns. Lasers at excitation lines of 405, 488, 552, and 638 nm were used to excite the DAPI stain and secondary antibodies labeling MMP-1 (488 nm), MMP-9 (568 nm), and substance P (633 nm), respectively. Images were acquired for each gel (6 images/gel) in regions containing DRG soma and/or axons (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a). Each image was acquired from a distinct region, with no DRG soma or its axons imaged twice.

The amount of positive labeling was quantified separately for each channel for each image using a custom MATLAB script that computes the number of pixels with fluorescence exceeding a threshold on a scale from 0–255 for 8-bit images (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a). Thresholds for positive labeling were determined from samples with no primary antibodies to verify antibody specificity. The number of positive pixels for each of substance P, MMP-1, and MMP-9 was normalized to the number of positive pixels for DAPI to account for different cell densities in each image; this calculation was performed for all sub-failure stretched and unstretched gels, separately. Then, each of the DAPI-normalized positive pixels for substance P, MMP-1, and MMP-9 of gels undergoing sub-failure stretch were divided by the positive pixels in the respective unloaded control gel, separately for each label. As such, protein expression is represented as the fold-change of stretched co-culture gels over that for unstretched control gels and accounts for differences in cell density in the acquired images.

All statistical analyses were performed with α = 0.05 using JMP-Prov15.2.0 (SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC). Peak forces and maximum principal strains (peak and average) were compared across groups (naïve, inhibitor, vehicle) with a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) by group. The hypothesis that the circular variance increases with equibiaxial stretch was tested between the reference (unstretched) state and the sub-failure peak stretch state using a matched paired t-test for each group, separately. The effect of sub-failure stretch on the immunolabeling outcomes of substance P, MMP-1, and MMP-9 was tested using a multivariate ANOVA (MANOVA) separately for each group (naïve, inhibitor treated, and vehicle treated) to account for possible dependence between the proteins themselves (Tabachnick and Fidell, 2007; Shin et al., 2015). To further explore the relationships between MMP-1 and each of the MMP-9 and substance P after sub-failure stretch, the linear regressions and strength of correlations were separately tested for co-cultures that did or did not receive inhibitor treatment; MANOVA analyses on groups that did or did not receive inhibitor were also performed. Naïve and vehicle-treated stretched gels were included in that analysis as controls representing co-cultures that did not receive ilomastat.

The 1.5 mm/arm equibiaxial stretch that was imposed does not produce any evidence of visible tears or macroscopic rupture for any gel (Figure 2A). In the naïve co-culture group, the stretch generates a peak force of 15.84 ± 4.25 mN, an average MPS of 9.69 ± 4.24%, and a peak MPS of 18.63 ± 6.57% (Table 1). The measured forces and strains are not altered with the addition of either the inhibitor (11.24 ± 6.50 mN; 14.05 ± 3.96% average MPS; 28.92 ± 15.93% peak MPS) or the DMSO vehicle alone (17.36 ± 7.65 mN; 13.31 ± 3.61%; average MPS; 30.62 ± 14.95% peak MPS) (Table 1). Indeed, none of the peak force (p = 0.228), peak MPS (p = 0.277) nor average MPS (p = 0.153) differs across groups (Table 1) verifying that all co-culture gels in this study received the same intensity and profile of mechanical stimulus.

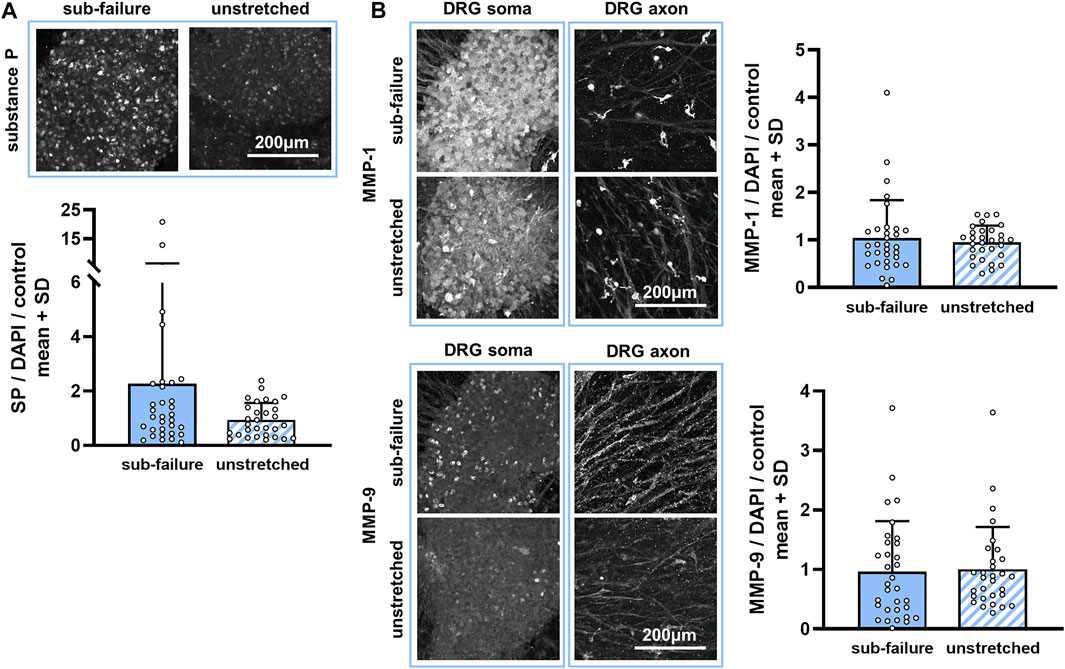

This sub-failure stretch alters the collagen microstructure in the DRG-FLS co-cultures. Stretch significantly changes the collagen microstructural organization of co-culture gels (p = 0.031), increasing the CV from the unloaded (reference) state (Figure 3). An increase in CV with stretch for most gels in the naïve group (5 out of 6) (Figure 3) indicates that the angle distribution of the collagen fibers moves from a less-clustered to a more-clustered orientation and suggests that the equibiaxial stretch aligns the collagen fibers (Figure 3). This reorganization in the collagen microstructure for a sub-failure stretch is accompanied by a nearly two-fold increase in substance P expression (Figure 4A). Despite that two-fold increase (Figure 4A), no significant effect of stretch is detected for any of the three protein outcomes (p = 0.404) (Figure 4).

FIGURE 3. Sub-failure equibiaxial stretch alters collagen microstructure in the FLS-DRG co-culture gels. Exemplary high-speed images with superimposed vector maps are shown displaying the pixel-wise raw fiber alignment; angles are relative to the horizontal, as marked in the image on the left. Histograms for gel S03 show the probability that collagen will orient at a given angle for both the reference state and at the point when peak force is detected for the sub-failure stretch. The stretch significantly increases the circular variance (p = 0.031; matched paired t-test, n = 6) indicating fiber reorganization during loading. Superimposed data points represent quantification for each gel and CV = circular variance.

FIGURE 4. Sub-failure stretch alters substance P, but not statistically significantly, and does not change MMP expression. (A) Substance P labeling is primarily evident in neuronal cell bodies (soma) and increases to 2.20 ± 3.96-fold over unstretched controls (p = 0.404; MANOVA, n = 6/stretch condition). (B) Abundant MMP-1 and MMP-9 labeling is observed in the DRG soma and in cells surrounding the DRG axons in co-culture gels. Expression levels of MMP-1 and MMP-9 (p = 0.404; MANOVA, n = 6/stretch condition) do not differ between sub-failure stretch and unstretched gels. Superimposed data points represent quantification in each confocal image acquired (n = 6/gel). The scale bar in each protein panel applies to all images in that panel.

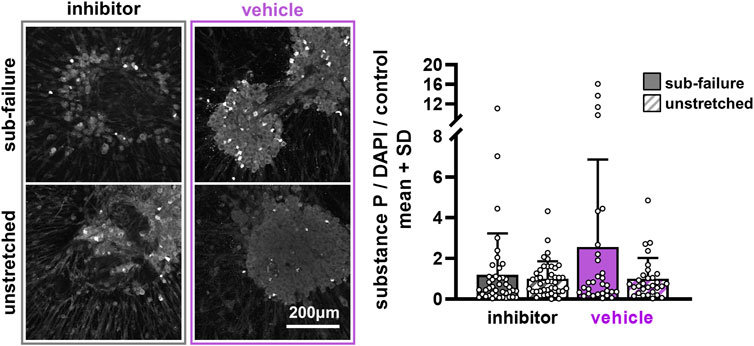

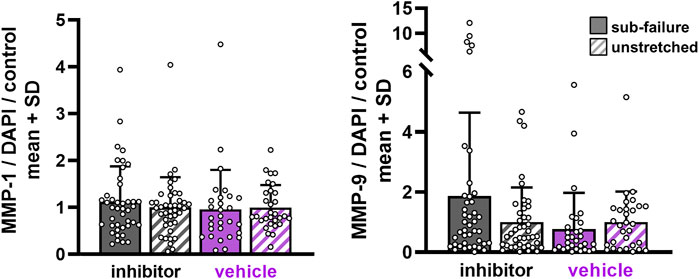

Ilomastat treatment attenuates stretch-induced increases in substance P expression without affecting the collagen fiber organization during sub-failure loading. Sub-failure stretch increases the CV for both inhibitor (p = 0.006) and vehicle groups (p = 0.028) (Figure 5), similar to that observed in the naïve co-culture group (Figure 3), with the CV increasing for each gel (Figure 5). Also similar to naïve co-culture gels (Figure 4), there is no significant effect of stretch on the protein outcomes with ilomastat (p = 0.114) or vehicle (p = 0.165) (Figures 6, 7), despite a 2.5-fold increase in substance P expression with stretch in the vehicle group (Figure 6). Furthermore, substance P expression in stretched inhibitor-treated co-cultures is over 2-fold lower than in stretched co-cultures receiving vehicle (inhibitor 1.19 ± 2.04; vehicle 2.56 ± 4.29) (Figure 6).

FIGURE 5. Sub-failure stretch-induced collagen reorganization is similar in gels receiving vehicle and inhibitor treatment. Histograms show the probability that collagen will orient at a given angle for the reference condition and at the peak force of the sub-failure stretch for a gel receiving inhibitor (S49) and vehicle (S46). Matched paired t-tests reveal that stretch increases the circular variance for all gels in both groups (inhibitor: p = 0.006, n = 7; vehicle: p = 0.028, n = 4). Superimposed data points represent quantification per gel. CV = circular variance.

FIGURE 6. Substance P is largely unchanged at 24 h after pre-treatment with ilomastat inhibitor or vehicle solution. Exemplary images of substance P labeling 24 h after stretch demonstrate similar expression levels between sub-failure and unstretched gels in inhibitor-treated DRG soma that are reflected in the summary data (p = 0.114; MANOVA, n = 7/stretch condition). Vehicle-treated soma, however, show more abundant labeling in the gels undergoing sub-failure stretch, with stretch increasing substance P levels to 2.56 ± 4.29-fold over unstretched gels (p = 0.165; MANOVA, n = 5/stretch condition). Superimposed data points represent quantification in each confocal image acquired (n = 6/gel). The scale bar applies to all images.

FIGURE 7. MMP expression with sub-failure equibiaxial stretch is unchanged regardless of ilomastat or vehicle treatment. Separate MANOVA analyses between sub-failure and unstretched gels in the inhibitor (p = 0.114; MANOVA n = 7/stretch condition) and vehicle (p = 0.165; MANOVA, n = 5/stretch condition) groups reveal similar expression levels. Superimposed data points represent quantification in each confocal image acquired (n = 6/gel).

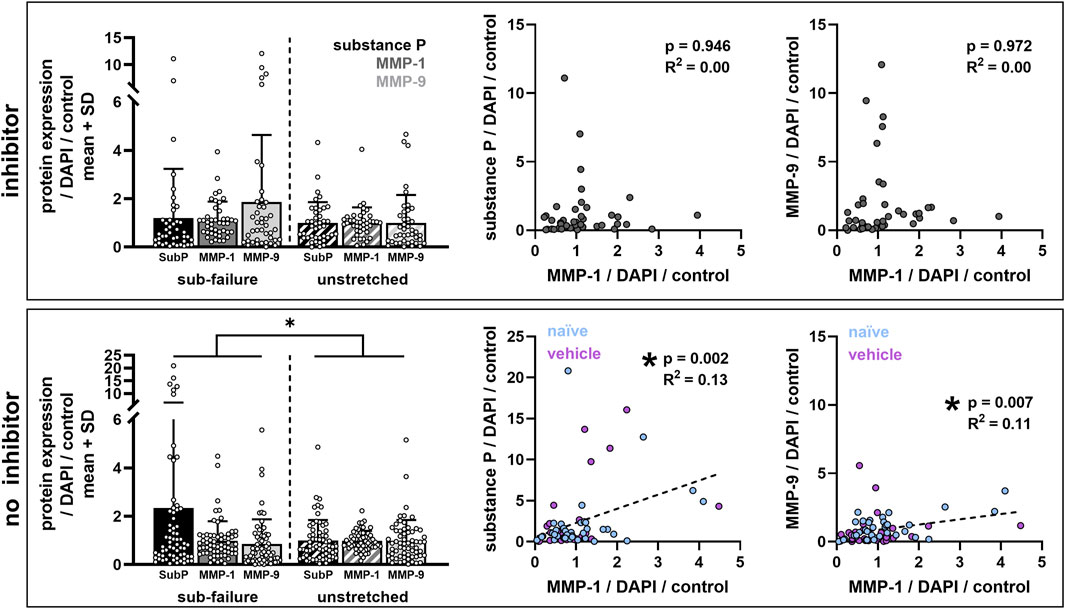

Despite the finding that sub-failure stretch does not significantly alter protein outcomes by group (Figures 4, 6), ilomastat treatment appears to attenuate stretch-induced increases in substance P and to abolish the correlative relationships that are observed between MMP-1 and substance P and between MMP-1 and MMP-9 in the groups without ilomastat (Figure 8). There is a significant effect of stretch on substance P expression in co-cultures that do not receive inhibitor (p = 0.038) that is driven by the elevated substance P in both naïve (Figure 4) and vehicle-treated co-cultures (Figure 6). Furthermore, a weak but significant correlation exists (p = 0.002) between MMP-1 and substance P after stretch only in the co-cultures that do not receive inhibitor (Figure 8). A significant correlation (p = 0.007) is also only detected between MMP-1 and MMP-9 for co-cultures with no inhibitor dosing (Figure 8). In contrast, in the presence of ilomastat inhibitor treatment, those significant correlations are not detected between MMPs with each other (p = 0.972) nor between MMP-1 and substance P (p = 0.946) (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8. Ilomastat treatment prevents stretch-induced increases in substance P and abolishes the correlations between MMP-1 and substance P and between MMPs with each other. Bar plots show protein expression data grouped by co-cultures that did (inhibitor) or did not (no inhibitor) receive ilomastat pre-treatment. Sub-failure stretch significantly effects protein expression outcomes (no inhibitor: *p = 0.038; MANOVA) only in the absence of an inhibitor (inhibitor: p = 0.114; MANOVA). Scatter plots show linear regressions between expression levels of different proteins (left: MMP-1 vs. substance P; right: MMP-1 versus MMP-9) with each data point representing labeling in a single confocal image. Significant correlations are detected between MMP-1 and substance P (p = 0.002; R2 = 0.13) and between MMP-1 and MMP-9 (p = 0.007; R2 = 0.11) in co-cultures without an inhibitor (naïve and vehicle; n = 11 gels). Correlations are not significant with inhibitor (n = 7 gels).

This study demonstrates that a sub-failure, equibiaxial stretch that imposes strains (Table 1) exceeding the threshold for neuronal dysregulation (Zhang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017) is sufficient to induce nociceptive signaling (Figure 8) and significant reorganization of collagen fibers (Figures 3, 5) in a DRG-FLS co-culture model mimicking the capsular ligament. However, despite that, the findings do not support our hypothesis that such a sub-failure stretch also regulates MMP-1 and MMP-9 expression in those peripheral neurons (Figure 4). Since that stretch does not increase expression of either of the MMPs probed here in the absence of ilomastat (Figure 4), it is not surprising that both MMP-1 and MMP-9 remained at similar levels regardless of stretch condition and pre-treatment exposure (Figure 7). However, the findings that ilomastat prevents stretch-induced substance P expression and suppresses interactions between MMP-1 and substance P and between MMP-1 and MMP-9 (Figure 8) suggest that MMP-1 and MMP-9 may be implicated in stretch-regulation of substance P.

The significant change in collagen kinematics observed with stretch likely underlies the elevated substance P in co-cultures without an inhibitor (Figure 8). This notion is supported by a body of work demonstrating that, in collagen networks, load-induced cellular responses are triggered by reorganization of the local fiber network surrounding its embedded cells (Sander et al., 2009; Bottini and Firestein, 2013; Zhang et al., 2016; Zarei et al., 2017). Such cellular responses include nociceptive signaling (Zhang et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018b; Zarei et al., 2017). In particular, stretch-induced kinematic rearrangement of collagen fibers disrupts the α2ß1-integrin adhesion between collagen molecules and the neuronal cell surface (Jokinen et al., 2004). This disruption of adhesion sites in stretched collagen networks mediates substance P expression in DRGs (Zhang et al., 2017). As such, it is likely that α2ß1-integrin receptors are involved in the interactions between DRGs and the collagen network under the sub-failure stretch imposed here (Figure 8). Of note, the collagen fibers are not expected to be directly affected by ilomastat treatment even though ilomastat inhibits the catabolic functionality of MMP-1 to cleave type-I collagen (Grobelny et al., 1992).

Moreover, MMP-1 and MMP-9 are likely involved in the cell–matrix interactions under load, despite remaining unchanged by sub-failure stretch across all groups (Figure 8). At the 24 h time point after a noxious stretch, the gene and protein expression levels of MMP-1 and MMP-9 may increase from transcriptional and/or post-translational regulation of MMPs (Bartok and Firestein 2010; Murphy and Nagase 2009; Petersen et al., 2012; Yang et al., 2005). Furthermore, MMP-1 can itself bind with the neuronal α2-integrin receptors and type-I collagen fibers to form a trimeric complex on the neuronal cell surface, activating intracellular ERK cascades and subsequent substance P release (Dumin et al., 2001; Campos et al., 2004; Conant et al., 2004). Although results suggest that MMPs do not increase on the neuronal cell surface (Figures 4, 7), it is possible that the FLS in the co-culture gels regulate MMPs via mechanisms such as MMP sequestration and/or retention (Bottini and Firestein, 2013). If this were the case, altered MMP expression might be localized to FLS cells and not in the neuronal regions that were assessed in this study (Figures 4, 6). Indeed, the possibility that FLS cells retain MMPs is supported by the finding that MMP-1 and MMP-9 localize to FLS cells after a uniaxial stretch to failure in this same co-culture system (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019b).

The fact that the kinematics of the collagen fibers are the same regardless of pre-treatment may be a result of the degradation changes not being captured by the CV measurements that were made using the full gel or could further amplify the non-ECM dependent roles of MMP-1 and MMP-9 in mediating neuronal dysregulation (Dumin et al., 2001; Conant et al., 2002; Conant et al., 2004; Visse and Nagase, 2003; Boire et al., 2005; Allen et al., 2016). Quantifying the regional localization of gel-entrapped MMPs would reveal if the matrix sites undergo MMP-mediated remodeling and/or degradation. If that were the case, regions with MMP-mediated alterations could have consequences on the bulk mechanics of the collagen gel and change microstructural collagen fiber kinematics under load. This suggestion is supported by the evidence of localized collagen degradation and anomalous collagen realignment events in the rat facet ligament after intra-articular MMP-1, both at its physiological configuration (no load) and in the sub-failure loading regime (Ita et al., submitted).

Increased substance P at a peak maximum principal strain of 18.64 ± 6.57% for naïve co-cultures and 30.62 ± 14.95% for co-cultures treated with the DMSO vehicle (Figure 8; Table 1) is consistent with prior reports that stretch at strain magnitudes between 8 and 40% induces pain in rats and increases substance P protein expression in neuron-seeded collagen gels (Dong et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2017; Zhang et al., 2018a). The fact that substance P is significantly elevated when these two groups (naïve; vehicle) are pooled (Figure 8) indicates a limitation in sample size for each group individually (Figures 4, 6). The forces produced by the sub-failure stretch in this study (14.47 ± 6.43 mN) (Table 1) are lower in magnitude than those reported in collagen gels with only DRGs exposed to a uniaxial configuration (26.25 ± 13.00 mN) (Zhang et al., 2018a). This difference in peak forces between collagen gels with only DRGs (Zhang et al., 2018a) and DRG-FLS co-cultures (Table 1) may be due to the effects of the FLS cells on their surrounding collagen environment or may be due to the different boundary conditions and stretch modalities in the studies (equibiaxial vs. uniaxial). Indeed, fibroblasts embedded in collagen networks exert forces on and remodel collagen in a manner that has well-documented effects on collagen gel mechanics when loaded (Evans and Barocas, 2009; Sander et al., 2011; Kural and Billiar, 2013; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a).

The finding that the equibiaxial stretch imposed here induces the same strains but lower forces than previous work without FLS (Zhang et al., 2018a) has implications for injury thresholds defined by strain and/or force magnitudes. Furthermore, the imposed forces and strains, although not significantly different, vary (Table 1). This spatial variability in strain fields produced by the equibiaxial loading paradigm translates to spatial variability in mechano-regulated cellular responses. The findings highlight the necessity that the complexities of in situ ligament boundaries be considered, and incorporated, when defining cellular responses to stretch using in vitro modeling.

The lack of effect of a sub-failure stretch on MMP expression levels (Figures 4, 7) may be due to technical considerations of the immunolabeling approach with respect to the pro- and active states of MMPs. For example, the primary antibodies used to visualize MMP-1 and MMP-9 bind to the pro- and active forms of the enzyme; furthermore, the antibody interaction is not expected to be altered if the MMP is in a bound state with the ilomastat inhibitor. As such, the MMP expression levels measured by immunolabeling cannot distinguish between inhibitor-bound MMP or between the pro- and active forms. As such, it is possible that an effect of ilomastat treatment on MMP enzyme activity may be missed using this approach. Nonetheless, ilomastat inhibition may lower the total MMP levels, regardless of their state, especially since ilomastat is present from DIV3 to DIV7 in the culture (Figure 1) when baseline FLS secretion of MMP-1 begins to plateau (Attia et al., 2014).

An alternative explanation to the lack of the effect of stretch on MMP levels in the ilomastat-treated gels could be that the catabolically inactive roles of MMP-1 and MMP-9 dominate in nociceptive-related signaling because ilomastat only inhibits the active forms of MMPs. Since ilomastat inhibits MMP activity by binding to the Zn2+ binding site of MMP-1 and MMP-9 (Grobelny et al., 1992; Galardy et al., 1994), ilomastat is expected to decrease the amount of active enzyme forms and to not affect the amount of pro-enzymes. As such, any inhibitory effect of ilomastat would likely only act on the collagenolytic functionality of MMP-1. This assumption that ilomastat only interferes with Zn2+-dependent MMP functionalities suggests that the myriad cell signaling roles of MMP-1 that are independent of its Zn2+ binding site (Dumin et al., 2001; Conant et al., 2002; Conant et al., 2004; Visse and Nagase, 2003; Boire et al., 2005; Allen et al., 2016) remain unaltered. This notion supports that ECM substrates of MMP-1 and/or MMP-9 (namely, type-I collagen as a substrate for MMP-1) are involved in nociceptive transmission and implies that any clinical intervention targeting MMP-1 and/or MMP-9 in pain from ligament injury or joint disorders must interfere with at least the active enzymatic form, although any role of the pro (zymogen)-enzyme forms cannot be ruled out.

Although the 25 nM ilomastat dose was chosen as the maximum dose expected to inhibit MMP-1 and MMP-9 without inhibiting MMP-3 (Grobelny et al., 1992; Galardy et al., 1994), it is possible that this concentration is too low to consistently inhibit MMP-1 and MMP-9. In fact, concentrations of ilomastat between 1 and 100 μM reduce the contractile function and collagen production of smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts in a dose-dependent manner (Daniels et al., 2003; Rogers et al., 2014). So, it is possible that higher doses of ilomastat would have more robust effects on MMP expression levels. Nevertheless, the 25 nM concentration and dosing beginning DIV3 (Figure 1) attenuates stretch-induced substance P levels (Figure 8), suggesting it to be sufficient to interfere with MMP pathways that regulate nociceptive pathways, at least to some extent.

The timepoint of 24 h after a stretch that was used for immunolabeling was chosen to allow for transcriptional and post-translational regulation to occur in the DRG and FLS cells; yet, it may not have captured the faster MMP regulatory processes. For example, a failure stretch quickly (within 3 min) increases neuronally localized MMP-1 and MMP-9 expressions (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a; 2019b) and is likely due to an existing extracellular MMP rapidly localizing to the neuronal cell surface, endocytic/exocytotic processes, or even cell rupture caused by the severity of the mechanical insult (Visse and Nagase, 2003; Bottini and Firestein, 2013). Studies of cyclic loading in tendons and dermal fibroblasts, however, show that MMP-1 gene expression is elevated after 4–24 h (Kessler et al., 2001; Yang et al., 2005). Responses that indicate neuronal dysregulation have also been shown to be evident after 24 h; for example, an expression of neuronal substance P increases after a mechanical stretch and intracellular calcium peaks in response to exogenous MMP-1 exposure (Zhang et al., 2017; Ita et al., 2018). Although the timepoint chosen in this study has limitations in capturing rapid cellular responses, it is advantageous in detecting regulators of more sustained nociception (Figure 8).

Despite the limitations pointed out, the ability of ilomastat to abolish the relationships between MMP-1 with MMP-9 and substance P (Figure 8) supports these biochemical mediators having mechanistic relationships in the context of stretch-induced nociception in the ligament. The positive correlative relationships demonstrated here (Figure 8) are consistent with parallel increases in MMP-1, MMP-9, and substance P immediately after a gel stretch that induces its failure (Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a; 2019b). Since active MMP-1 catalyzes pro-MMP-9 by cleaving its bait region (Conant et al., 2002; Visse and Nagase, 2003) and MMP-9 cleaves substance P (Diekmann and Tschesche, 1994; Rawlings et al., 2014), all three proteins could be related in their response to noxious stimulus (i.e., stretch) here (Figure 8). However, since ilomastat also inhibits MMP-9 at a higher affinity than MMP-1 (Grobelny et al., 1992; Galardy et al., 1994), a definitive relationship between MMP-1 and MMP-9 cannot be concluded since ilomastat acts on both active forms of the enzymes. Studies utilizing siRNA silencing techniques in cell cultures could be exploited to target MMP-1 synthesis (Rogers et al., 2014). siRNA-induced post-transcriptional silencing would suppress the translation of MMP-1 (Agrawal et al., 2003), selectively removing MMP-1 production by cells without the off-target effects on other MMPs that is unavoidable with the ilomastat synthetic inhibitor. In fact, separately silencing MMP-1 synthesis in FLS cultures and/or DRG cultures before their co-culture could be helpful in fully defining the role of cell-specific MMP-1 in nociceptive responses. That approach would also directly determine if the complete obliteration of MMP-1 affects the pro- and/or active levels of MMP-9.

Collectively, the findings in this study implicate MMPs in painful ligamentous injuries and contribute to a growing body of work linking MMPs to nociceptive-related signaling pathways and/or pain (Kawasaki et al., 2008; Sbardella et al., 2012; Allen et al., 2016; Ita and Winkelstein, 2019a; Ita et al., 2020a; Ita et al., 2021). Although MMP-9 has a well-established role in nociception, particularly for neuropathic pain (Kawasaki et al., 2008), studies examining the role of MMP-1 in nociception are sparse by comparison. Since MMP-1 is generally only expressed in pathologic disease and/or injury states in in vivo systems (Sbardella et al., 2012), investigating techniques that selectively inhibit MMP-1 may be of use since less detrimental off-target effects are expected. Selective MMP inhibition is particularly important if inhibition studies are pursued in vivo, since the primary reason that broad-spectrum MMP inhibitors such as ilomastat have failed in clinical trials is due to off-target effects in part from their systemic administration (Coussens et al., 2002; Fingleton, 2008; Vandenbroucke and Libert, 2014). Although those same off-target effects are not expected to be at play in the co-culture model used in this study, ilomastat may also have unanticipated actions such as binding to non-MMP enzymes that contain metals or interfering with ADAMTS released by fibroblasts (Fingleton, 2008; Bottini and Firestein, 2013; Ernberg, 2017). No selective inhibitors for MMP-1 exist currently; yet, selective inhibition of MMP-13 has been successfully achieved by targeting regions other than the preserved Zn2+ binding site (Baragi et al., 2009; Jüngel et al., 2010; Gege et al., 2012). Pursuing MMP-1 inhibition by this same selective approach may provide a promising opportunity to define the effect of isolated blocking of MMP-1 activity on other MMPs, such as MMP-9, and to determine if selective MMP-1 inhibition in vivo has the potential to reduce pain without clinical side effects.

The raw data supporting the conclusion of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

All cells were harvested from Sprague Dawley male rats under University of Pennsylvania IACUC-approved conditions.

MI and BW contributed to the conception and design of the study. MI performed all experiments, immunolabeling assays, data acquisition and analyses, and statistical analyses. MI and BW interpreted the findings and drafted the manuscript. Both authors critically reviewed and approved the final manuscript. BW (d2lua2Vsc3RAc2Vhcy51cGVubi5lZHU=) takes responsibility for the integrity of the work from inception to the finished article. Both authors agree to be accountable for the content of the work.

This project was performed with funding from the NCCIH (AT010326-07). The study sponsors had no role in study design, data collection, analysis, and interpretation, manuscript drafting, and in the decision to submit this article for publication.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The authors thank the Cell and Developmental Biology Microscopy Core at the University of Pennsylvania for assistance with confocal microscopy.

Agrawal, N., Dasaradhi, P. V. N., Mohmmed, A., Malhotra, P., Bhatnagar, R. K., and Mukherjee, S. K. (2003). RNA Interference: Biology, Mechanism, and Applications. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 67, 657–685. doi:10.1128/mmbr.67.4.657-685.2003

Allen, M., Ghosh, S., Ahern, G. P., Villapol, S., Maguire-Zeiss, K. A., and Conant, K. (2016). Protease Induced Plasticity: Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 Promotes Neurostructural Changes through Activation of Protease Activated Receptor 1. Sci. Rep. 6, 35497. doi:10.1038/srep35497

Attia, E., Bohnert, K., Brown, H., Bhargava, M., and Hannafin, J. A. (2014). Characterization of Total and Active Matrix Metalloproteinases-1, -3, and -13 Synthesized and Secreted by Anterior Cruciate Ligament Fibroblasts in Three-Dimensional Collagen Gels. Tissue Eng. A 20, 171–177. doi:10.1089/ten.tea.2012.0669

Backstrom, J. R., and Tökés, Z. A. (1995). The 84-kDa Form of Human Matrix Metalloproteinase-9 Degrades Substance P and Gelatin. J. Neurochem. 64, 1312–1318. doi:10.1046/J.1471-4159.1995.64031312.X

Ban, E., Zhang, S., Zarei, V., Barocas, V. H., Winkelstein, B. A., and Picu, C. R. (2017). Collagen Organization in Facet Capsular Ligaments Varies with Spinal Region and with Ligament Deformation. J. Biomech. Eng. 139, 071009. doi:10.1115/1.4036019

Bartok, B., and Firestein, G. S. (2010). Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes: Key Effector Cells in Rheumatoid Arthritis. Immunol. Rev. 233, 233–255. doi:10.1111/j.0105-2896.2009.00859.x

Baragi, V. M., Becher, G., Bendele, A. M., Biesinger, R., Bluhm, H., Boer, J., et al. (2009). A New Class of Potent Matrix Metalloproteinase 13 Inhibitors for Potential Treatment of Osteoarthritis: Evidence of Histologic and Clinical Efficacy without Musculoskeletal Toxicity in Rat Models. Arthritis Rheum. 60, 2008–2018. doi:10.1002/art.24629

Boire, A., Covic, L., Agarwal, A., Jacques, S., Sherifi, S., and Kuliopulos, A. (2005). PAR1 Is a Matrix Metalloprotease-1 Receptor that Promotes Invasion and Tumorigenesis of Breast Cancer Cells. Cell 120, 303–313. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2004.12.018

Bottini, N., and Firestein, G. S. (2013). Duality of Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes in RA: Passive Responders and Imprinted Aggressors. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 9, 24–33. doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2012.190

Braz, J. M., Nassar, M. A., Wood, J. N., and Basbaum, A. I. (2005). Parallel “Pain” Pathways Arise from Subpopulations of Primary Afferent Nociceptor. Neuron 47, 787–793. doi:10.1016/j.neuron.2005.08.015

Campos, L. S., Leone, D. P., Relvas, J. B., Brakebusch, C., Fässler, R., Suter, U., et al. (2004). β1 Integrins Activate a MAPK Signalling Pathway in Neural Stem Cells that Contributes to Their Maintenance. Development 131, 3433–3444. doi:10.1242/dev.01199

Chen, C., Lu, Y., Kallakuri, S., Patwardhan, A., and Cavanaugh, J. M. (2006). Distribution of A-δ and C-Fiber Receptors in the Cervical Facet Joint Capsule and Their Response to Stretch. J. Bone Jt. Surg. 88, 1807–1816. doi:10.2106/JBJS.E.00880

Cohen, M. S., Schimmel, D. R., Masuda, K., Hastings, H., and Muehleman, C. (2007). Structural and Biochemical Evaluation of the Elbow Capsule after Trauma. J. Shoulder Elbow Surg. 16, 484–490. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2006.06.018

Conant, K., Haughey, N., Nath, A., Hillaire, C. S., Gary, D. S., Pardo, C. A., et al. (2002). Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 Activates a Pertussis Toxin-Sensitive Signaling Pathway that Stimulates the Release of Matrix Metalloproteinase-9. J. Neurochem. 82, 885–893. doi:10.1046/j.1471-4159.2002.01038.x

Conant, K., Hillaire, C. S., Nagase, H., Visse, R., Gary, D., Haughey, N., et al. (2004). Matrix Metalloproteinase 1 Interacts with Neuronal Integrins and Stimulates Dephosphorylation of Akt. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 8056–8062. doi:10.1074/jbc.M307051200

Coussens, L. M., Fingleton, B., and Matrisian, L. M. (2002). Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors and Cancer-Trials and Tribulations. Science 295, 2387–2392. doi:10.1126/science.1067100

Crosby, N. D., Zaucke, F., Kras, J. V., Dong, L., Luo, Z. D., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2015). Thrombospondin-4 and Excitatory Synaptogenesis Promote Spinal Sensitization after Painful Mechanical Joint Injury. Exp. Neurol. 264, 111–120. doi:10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.11.015

Daniels, J. T., Cambrey, A. D., Occleston, N. L., Garrett, Q., Tarnuzzer, R. W., Schultz, G. S., et al. (2003). Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibition Modulates Fibroblast-Mediated Matrix Contraction and Collagen Production In Vitro. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 44, 1104–1110. doi:10.1167/iovs.02-0412

Diekmann, O., and Tschesche, H. (1994). Degradation of Kinins, Angiotensins and Substance P by Polymorphonuclear Matrix Metalloproteinases MMP 8 and MMP 9. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 27, 1865–1876. Available at: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7538373 (Accessed March 1, 2019).

Dong, L., Quindlen, J. C., Lipschutz, D. E., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2012). Whiplash-like Facet Joint Loading Initiates Glutamatergic Responses in the DRG and Spinal Cord Associated with Behavioral Hypersensitivity. Brain Res. 1461, 51–63. doi:10.1016/j.brainres.2012.04.026

Dong, L., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2010). Simulated Whiplash Modulates Expression of the Glutamatergic System in the Spinal Cord Suggesting Spinal Plasticity Is Associated with Painful Dynamic Cervical Facet Loading. J. Neurotrauma 27, 163–174. doi:10.1089/neu.2009.0999

Dumin, J. A., Dickeson, S. K., Stricker, T. P., Bhattacharyya-Pakrasi, M., Roby, J. D., Santoro, S. A., et al. (2001). Pro-collagenase-1 (Matrix Metalloproteinase-1) Binds the α2β1 Integrin upon Release from Keratinocytes Migrating on Type I Collagen. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 29368–29374. doi:10.1074/jbc.M104179200

Elliott, J. M., Noteboom, J. T., Flynn, T. W., and Sterling, M. (2009). Characterization of Acute and Chronic Whiplash-Associated Disorders. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 39, 312–323. doi:10.2519/jospt.2009.2826

Ernberg, M. (2017). The Role of Molecular Pain Biomarkers in Temporomandibular Joint Internal Derangement. J. Oral Rehabil. 44, 481–491. doi:10.1111/joor.12480

Evans, M. C., and Barocas, V. H. (2009). The Modulus of Fibroblast-Populated Collagen Gels Is Not Determined by Final Collagen and Cell Concentration: Experiments and an Inclusion-Based Model. J. Biomech. Eng. 131, 101014. doi:10.1115/1.4000064

Fields, G. B. (2013). Interstitial Collagen Catabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 288, 8785–8793. doi:10.1074/jbc.R113.451211

Fingleton, B. (2008). MMPs as Therapeutic Targets-Still a Viable Option? Semin. Cel Dev. Biol. 19, 61–68. doi:10.1016/j.semcdb.2007.06.006

Flynn, B. P., Bhole, A. P., Saeidi, N., Liles, M., Dimarzio, C. A., and Ruberti, J. W. (2010). Mechanical Strain Stabilizes Reconstituted Collagen Fibrils against Enzymatic Degradation by Mammalian Collagenase Matrix Metalloproteinase 8 (MMP-8). PLoS One 5, e12337. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012337

Galardy, R. E., Cassabonne, M. E., Giese, C., Gilbert, J. H., Lapierre, F., Lopez, H., et al. (1994). Low Molecular Weight Inhibitors in Corneal Ulceration. Ann. NY Acad. Sci. 732, 315–323. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1994.tb24746.x

Gege, C., Bao, B., Bluhm, H., Boer, J., Gallagher, B. M., Korniski, B., et al. (2012). Discovery and Evaluation of a Non-zn Chelating, Selective Matrix Metalloproteinase 13 (MMP-13) Inhibitor for Potential Intra-articular Treatment of Osteoarthritis. J. Med. Chem. 55, 709–716. doi:10.1021/jm201152u

Grobelny, D., Poncz, L., and Galardy, R. E. (1992). Inhibition of Human Skin Fibroblast Collagenase, Thermolysin, and Pseudomonas aeruginosa Elastase by Peptide Hydroxamic Acids. Biochemistry 31, 7152–7154. doi:10.1021/bi00146a017

Haller, J. M., Swearingen, C. A., Partridge, D., McFadden, M., Thirunavukkarasu, K., and Higgins, T. F. (2015). Intraarticular Matrix Metalloproteinases and Aggrecan Degradation Are Elevated after Articular Fracture. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 473, 3280–3288. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4441-4

Hogg-Johnson, S., van der Velde, G., Carroll, L. J., Holm, L. W., Cassidy, J. D., Guzman, J., et al. (20081976). The Burden and Determinants of Neck Pain in the General Population. Eur. Spine J. 17, 39–51. doi:10.1016/j.jmpt.2008.11.01010.1007/s00586-008-0624-y

Ita, M. E., Crosby, N. D., Bulka, B. A., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2017a). Painful Cervical Facet Joint Injury Is Accompanied by Changes in the Number of Excitatory and Inhibitory Synapses in the Superficial Dorsal Horn that Differentially Relate to Local Tissue Injury Severity. Spine (Phila. Pa. 1976) 42, E695–E701. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000001934

Ita, M. E., Ghimire, P., Granquist, E. J., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2021). MMPs in Tissues Retrieved during Surgery from Patients with TMJ Disorders Relate to Pain More Than to Radiological Damage Score. J. Orthopaedic Res. 40, 338–347. doi:10.1002/jor.25048

Ita, M. E., Ghimire, P., Welch, R. L., Troche, H. R., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2020a). Intra-articular Collagenase in the Spinal Facet Joint Induces Pain, DRG Neuron Dysregulation and Increased MMP-1 Absent Evidence of Joint Destruction. Sci. Rep. 10. doi:10.1038/S41598-020-78811-3

Ita, M. E., Leavitt, O. M. E., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2018). “MMP-1 Induces Joint Pain that May Be Mediated by Increased Activity in Peripheral Neurons,” in Orthopaedic Research Society Annual Meeting (New Orleans, LA). #2184.

Ita, M. E., Singh, S., Troche, H. R., Welch, R. L., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2020b). Intra-Articular MMP-1 in the Spinal Facet Joint Induces Pain, Modified Ligament Kinematics, & Neuronal Dysregulation in the DRG & Spinal Cord. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol.

Ita, M. E., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2019a). Concentration-Dependent Effects of Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes on Collagen Gel Multiscale Biomechanics and Neuronal Signaling: Implications for Modeling Human Ligamentous Tissues. J. Biomech. Eng. 141, 0910131–09101312. doi:10.1115/1.4044051

Ita, M. E., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2019b). MMP-1 & MMP-9 Increase after Tensile Stretch: Lessons from Neuronal-Fibroblast Co-cultures Simulating Joint Capsules. Philadelphia, PA: Biomedical Engineering Society Annual Meeting. #767.

Ita, M. E., Zhang, S., Holsgrove, T. P., Kartha, S., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2017b). The Physiological Basis of Cervical Facet-Mediated Persistent Pain: Basic Science and Clinical Challenges. J. Orthop. Sports Phys. Ther. 47, 450–461. doi:10.2519/jospt.2017.7255

Jaumard, N. V., Welch, W. C., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2011). Spinal Facet Joint Biomechanics and Mechanotransduction in normal, Injury and Degenerative Conditions. J. Biomech. Eng. 133, 071010. doi:10.1115/1.4004493

Jokinen, J., Dadu, E., Nykvist, P., Käpylä, J., White, D. J., Ivaska, J., et al. (2004). Integrin-mediated Cell Adhesion to Type I Collagen Fibrils. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 31956–31963. doi:10.1074/jbc.M401409200

Jungel, A., Ospelt, C., Lesch, M., Thiel, M., Sunyer, T., Schorr, O., et al. (2010). Effect of the Oral Application of a Highly Selective MMP-13 Inhibitor in Three Different Animal Models of Rheumatoid Arthritis. Ann. Rheum. Dis. 69, 898–902. doi:10.1136/ard.2008.106021

Kallakuri, S., Singh, A., Chen, C., and Cavanaugh, J. M. (2004). Demonstration of Substance P, Calcitonin Gene-Related Peptide, and Protein Gene Product 9.5 Containing Nerve Fibers in Human Cervical Facet Joint Capsules. Spine 29, 1182–1186. 1976. doi:10.1097/00007632-200406010-00005

Kallakuri, S., Singh, A., Lu, Y., Chen, C., Patwardhan, A., and Cavanaugh, J. M. (2008). Tensile Stretching of Cervical Facet Joint Capsule and Related Axonal Changes. Eur. Spine J. 17, 556–563. doi:10.1007/s00586-007-0562-0

Kartha, S., Bulka, B. A., Stiansen, N. S., Troche, H. R., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2018). Repeated High Rate Facet Capsular Stretch at Strains that Are below the Pain Threshold Induces Pain and Spinal Inflammation with Decreased Ligament Strength in the Rat. J. Biomech. Eng. 140, 0810021. doi:10.1115/1.4040023

Kawasaki, Y., Xu, Z.-Z., Wang, X., Park, J. Y., Zhuang, Z.-Y., Tan, P.-H., et al. (2008). Distinct Roles of Matrix Metalloproteases in the Early- and Late-phase Development of Neuropathic Pain. Nat. Med. 14, 331–336. doi:10.1038/nm1723

Kessler, D., Dethlefsen, S., Haase, I., Plomann, M., Hirche, F., Krieg, T., et al. (2001). Fibroblasts in Mechanically Stressed Collagen Lattices Assume a “Synthetic” Phenotype. J. Biol. Chem. 276, 36575–36585. doi:10.1074/JBC.M101602200

Kural, M. H., and Billiar, K. L. (2013). Regulating Tension in Three-Dimensional Culture Environments. Exp. Cel Res. 319, 2447–2459. doi:10.1016/j.yexcr.2013.06.019

Lee, K. E., Davis, M. B., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2008). Capsular Ligament Involvement in the Development of Mechanical Hyperalgesia after Facet Joint Loading: Behavioral and Inflammatory Outcomes in a Rodent Model of Pain. J. Neurotrauma 25, 1383–1393. doi:10.1089/neu.2008.0700

Lee, K. E., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2009). Joint Distraction Magnitude Is Associated with Different Behavioral Outcomes and Substance P Levels for Cervical Facet Joint Loading in the Rat. The J. Pain 10, 436–445. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2008.11.009

Loeser, R. F., Goldring, S. R., Scanzello, C. R., and Goldring, M. B. (2012). Osteoarthritis: A Disease of the Joint as an Organ. Arthritis Rheum. 64, 1697–1707. doi:10.1002/art.34453

Lu, Y., Chen, C., Kallakuri, S., Patwardhan, A., and Cavanaugh, J. M. (2005). Neural Response of Cervical Facet Joint Capsule to Stretch: A Study of Whiplash Pain Mechanism. Stapp Car Crash J. 49, 49–65. doi:10.4271/2005-22-0003

Murphy, G., and Nagase, H. (2009). Progress in Matrix Metalloproteinase Research. Mol. Aspects Med. 29, 290–308. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2008.05.002

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine (2020). Temporomandibular Disorders: Priorities for Research and Care. Washington, DC. doi:10.17226/25652

Obata, K., and Noguchi, K. (2004). MAPK Activation in Nociceptive Neurons and Pain Hypersensitivity. Life Sci. 74, 2643–2653. doi:10.1016/j.lfs.2004.01.007

Otterness, I. G., Bliven, M. L., Eskra, J. D., Te Koppele, J. M., Stukenbrok, H. A., and Milici, A.-J. (2000). Cartilage Damage after Intraarticular Exposure to Collagenase 3. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 8, 366–373. doi:10.1053/joca.1999.0311

Pearson, A. M., Ivancic, P. C., Ito, S., and Panjabi, M. M. (2004). Facet Joint Kinematics and Injury Mechanisms during Simulated Whiplash. Spine 29, 390–397. 1976. doi:10.1097/01.BRS.0000090836.50508.F7

Perolat, R., Kastler, A., Nicot, B., Pellat, J.-M., Tahon, F., Attye, A., et al. (2018). Facet Joint Syndrome: from Diagnosis to Interventional Management. Insights Imaging 9, 773–789. doi:10.1007/S13244-018-0638-X

Petersen, A., Joly, P., Bergmann, C., Korus, G., and Duda, G. N. (2012). The Impact of Substrate Stiffness and Mechanical Loading on Fibroblast-Induced Scaffold Remodeling. Tissue Eng. Part A 18, 1804–1817. doi:10.1089/ten.tea.2011.0514

Quinn, K. P., Bauman, J. A., Crosby, N. D., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2010a). Anomalous Fiber Realignment during Tensile Loading of the Rat Facet Capsular Ligament Identifies Mechanically Induced Damage and Physiological Dysfunction. J. Biomech. 43, 1870–1875. doi:10.1016/j.jbiomech.2010.03.032

Quinn, K. P., Dong, L., Golder, F. J., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2010b). Neuronal Hyperexcitability in the Dorsal Horn after Painful Facet Joint Injury. Pain 151, 414–421. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2010.07.034

Quinn, K. P., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2008). Altered Collagen Fiber Kinematics Define the Onset of Localized Ligament Damage during Loading. J. Appl. Physiol. 105, 1881–1888. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.90792.2008

Rawlings, N. D., Waller, M., Barrett, A. J., and Bateman, A. (2014). MEROPS: the Database of Proteolytic Enzymes, Their Substrates and Inhibitors. Nucl. Acids Res. 42, D503–D509. doi:10.1093/NAR/GKT953

Rogers, N. K., Clements, D., Dongre, A., Harrison, T. W., Shaw, D., and Johnson, S. R. (2014). Extra-Cellular Matrix Proteins Induce Matrix Metalloproteinase-1 (MMP-1) Activity and Increase Airway Smooth Muscle Contraction in Asthma. PLoS One 9, e90565. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0090565

Sander, E. A., Barocas, V. H., and Tranquillo, R. T. (2011). Initial Fiber Alignment Pattern Alters Extracellular Matrix Synthesis in Fibroblast-Populated Fibrin Gel Cruciforms and Correlates with Predicted Tension. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 39, 714–729. doi:10.1007/s10439-010-0192-2

Sander, E. A., Stylianopoulos, T., Tranquillo, R. T., and Barocas, V. H. (2009). Image-based Multiscale Modeling Predicts Tissue-Level and Network-Level Fiber Reorganization in Stretched Cell-Compacted Collagen Gels. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 106, 17675–17680. doi:10.1073/pnas.0903716106

Saravanan, S., Hairul Islam, V. I., Thirugnanasambantham, K., Pazhanivel, N., Raghuraman, N., Gabriel Paulraj, M., et al. (2014). Swertiamarin Ameliorates Inflammation and Osteoclastogenesis Intermediates in IL-1β Induced Rat Fibroblast-like Synoviocytes. Inflamm. Res. 63, 451–462. doi:10.1007/s00011-014-0717-5

Sbardella, D., Fasciglione, G. F., Gioia, M., Ciaccio, C., Tundo, G. R., Marini, S., et al. (2012). Human Matrix Metalloproteinases: An Ubiquitarian Class of Enzymes Involved in Several Pathological Processes. Mol. Aspects Med. 33, 119–208. doi:10.1016/j.mam.2011.10.015

Schindelin, J., Arganda-Carreras, I., Frise, E., Kaynig, V., Longair, M., Pietzsch, T., et al. (2012). Fiji: an Open-Source Platform for Biological-Image Analysis. Nat. Methods 9, 676–682. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2019

Shin, S. Y., Pozzi, A., Boyd, S. K., and Clark, A. L. (2016). Integrin α1β1 Protects against Signs of post-traumatic Osteoarthritis in the Female Murine Knee Partially via Regulation of Epidermal Growth Factor Receptor Signalling. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 24, 1795–1806. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2016.05.013

Sperry, M. M., Ita, M. E., Kartha, S., Zhang, S., Yu, Y.-H., and Winkelstein, B. (2017). The Interface of Mechanics and Nociception in Joint Pathophysiology: Insights from the Facet and Temporomandibular Joints. J. Biomech. Eng. 139, 021003–1021003–13. doi:10.1115/1.4035647

Tabachnick, B. G., and Fidell, L. S. (2007). Using Multivariate Statistics. 5th Editio. Boston, MA: Pearson/Allyn and Bacon.

Tower, T. T., Neidert, M. R., and Tranquillo, R. T. (2002). Fiber Alignment Imaging during Mechanical Testing of Soft Tissues. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 30, 1221–1233. doi:10.1114/1.1527047

van Osch, G. J. V. M., Blankevoort, L., van der Kraan, P. M., Janssen, B., Hekman, E., Huiskes, R., et al. (1995). Laxity Characteristics of normal and Pathological Murine Knee Jointsin Vitro. J. Orthop. Res. 13, 783–791. doi:10.1002/jor.1100130519

Vandenbroucke, R. E., and Libert, C. (2014). Is There new hope for Therapeutic Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibition? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 13, 904–927. doi:10.1038/nrd4390

Varady, N. H., and Grodzinsky, A. J. (2016). Osteoarthritis Year in Review 2015: Mechanics. Osteoarthritis and Cartilage 24, 27–35. doi:10.1016/j.joca.2015.07.02610.1016/j.joca.2015.08.018

Visse, R., and Nagase, H. (2003). Matrix Metalloproteinases and Tissue Inhibitors of Metalloproteinases. Circ. Res. 92, 827–839. doi:10.1161/01.RES.0000070112.80711.3D

Winkelstein, B. A., and Santos, D. G. (20081976). An Intact Facet Capsular Ligament Modulates Behavioral Sensitivity and Spinal Glial Activation Produced by Cervical Facet Joint Tension. Spine 33, 856–862. doi:10.1097/BRS.0b013e31816b4710

Yang, G., Im, H.-J., and Wang, J. H.-C. (2005). Repetitive Mechanical Stretching Modulates IL-1β Induced COX-2, MMP-1 Expression, and PGE2 Production in Human Patellar Tendon Fibroblasts. Gene 363, 166–172. doi:10.1016/J.GENE.2005.08.006

Zarei, V., Zhang, S., Winkelstein, B. A., and Barocas, V. H. (2017). Tissue Loading and Microstructure Regulate the Deformation of Embedded Nerve Fibres: Predictions from Single-Scale and Multiscale Simulations. J. R. Soc. Interf. 14, 20170326. doi:10.1098/rsif.2017.0326

Zhang, S., Cao, X., Stablow, A. M., Shenoy, V. B., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2016). Tissue Strain Reorganizes Collagen with a Switchlike Response that Regulates Neuronal Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase Phosphorylation In Vitro: Implications for Ligamentous Injury and Mechanotransduction. J. Biomech. Eng. 138, 021013. doi:10.1115/1.4031975

Zhang, S., Singh, S., and Winkelstein, B. A. (2018a). Collagen Organization Regulates Stretch-Initiated Pain-Related Neuronal Signals In Vitro: Implications for Structure-Function Relationships in Innervated Ligaments. J. Orthop. Res. 36, 770–777. doi:10.1002/jor.23657

Zhang, S., Zarei, V., Winkelstein, B. A., and Barocas, V. H. (2018b). Multiscale Mechanics of the Cervical Facet Capsular Ligament, with Particular Emphasis on Anomalous Fiber Realignment Prior to Tissue Failure. Biomech. Model. Mechanobiol. 17, 133–145. doi:10.1007/s10237-017-0949-8

Keywords: matrix metalloproteinase-1, matrix metalloproteinase-9, nociception, ligament, collagen, injury, pain

Citation: Ita ME and Winkelstein BA (2022) MMPs Regulate Neuronal Substance P After a Painful Equibiaxial Stretch in a Co-Culture Collagen Gel Model Simulating Injury of an Innervated Ligament. Front. Mech. Eng 8:849283. doi: 10.3389/fmech.2022.849283

Received: 05 January 2022; Accepted: 28 February 2022;

Published: 18 March 2022.

Edited by:

Ehsan Ban, Yale University, United StatesReviewed by:

Eng Kuan Moo, University of Calgary, CanadaCopyright © 2022 Ita and Winkelstein. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Beth A. Winkelstein, d2lua2Vsc3RAc2Vhcy51cGVubi5lZHU=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.