95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mech. Eng. , 29 May 2020

Sec. Engine and Automotive Engineering

Volume 6 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmech.2020.00021

This article is part of the Research Topic Fundamental Characterization and Performance of Alternative Fuels View all 9 articles

The necessity of neutralizing the increase of the temperature of the atmosphere by the reduction of greenhouse gas emissions, in particular carbon dioxide (CO2), as well as replacing fossil fuels, leads to a necessary energy transition that is already happening. This energy transition requires the deployment of renewable energies that will replace gradually the fossil fuels. As the renewable energy share increases, energy storage will become key to avoid curtailment or polluting back-up systems. This paper considers a chemical storage process based on the use of electricity to produce hydrogen by electrolysis of water. The obtained hydrogen (H2) can then be stored directly or further converted into methane (CH4 from methanation, if CO2 is available, e.g., from a carbon capture facility), methanol (CH3OH, again if CO2 is available), and/or ammonia (NH3 by an electrochemical process). These different fuels can be stored in liquid or gaseous forms, and therefore with different energy densities depending on their physical and chemical nature. This work aims at evaluating the energy and the economic costs of the production, storage and transport of these different fuels derived from renewable electricity sources. This applied study on chemical storage underlines the advantages and disadvantages of each fuel in the frame of the energy transition.

The massive shift to renewable energy is crucial to meet the long-term objective of CO2 neutrality by 2050. The integration of renewables will lead to a huge need in electricity storage at different time scales. To keep a continuous electricity supply, even when wind turbines and photovoltaic panels do not produce sufficiently, energy storage becomes one of the key component of the energy system.

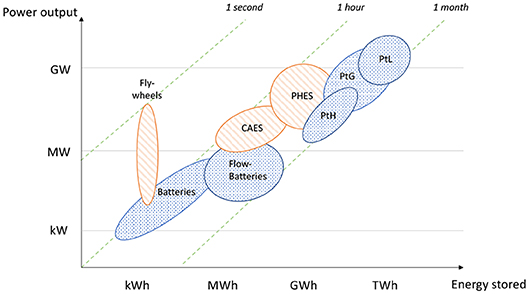

Different forms of storage are currently available: mechanical [Pumped Hydro Energy Storage (PHES), Compressed Air Energy Storage (CAES), Liquid Air Energy Storage (LAES), Flywheels], electrical [capacitors, super capacitors, Superconducting Magnetic Energy Storage (SMES)], electrochemical (batteries, flow batteries), thermal [low (cryogenic) and high (heating systems) temperatures], and chemical (hydrogen, methane, ammonia, methanol …). These different storage techniques make it possible to diversify the nature of the stored energy (mechanical, thermal, electrochemical and chemical) according to the required capacity and the desired storage time. Many authors present these different storage technologies in detail (see e.g., Ibrahim et al., 2008; Chen et al., 2009; Hadjipaschalis et al., 2009; Ferreira et al., 2013; Koohi-Kamali et al., 2013; Kousksou et al., 2014; Lund et al., 2015; Luo et al., 2015; Zakeri and Syri, 2015; Aneke and Wang, 2016; Gallo et al., 2016; Kyriakopoulos and Arabatzis, 2016; Das et al., 2018). Depending on the storage capacity and the restitution duration, a classification of these technologies is given in Figure 1. For small amounts of energy (from 1 kWh to 1 MWh) and short discharging period (seconds to hours), storage by capacitors, flywheels, batteries and flow-batteries are optimal. For larger capacities from 10 MWh to 100 GWh, mechanical storage, such as CAES and PHES are more suitable. These techniques can be used to provide electricity across a country for a few hours or even a day.

Figure 1. Link between the restituted electrical power and the stored energy capacity for different storage techniques: mechanical storage in orange and chemical storage in blue—based on Limpens and Jeanmart (2018).

For larger amounts of energy (up to 100 TWh) and longer-term storage (weeks), electricity can be stored through the production of fuels, by the power-to-X technique, where “X” represents gas (Power-to-Gas, PtG) or liquid (Power-to-L, PtL), commonly called Power-to-Fuel (PtF); or chemicals for the chemical industry. Power-to-Hydrogen (PtH) is shown separately in Figure 1. The advantages of PtF for long-term storage and large capacity can be explained by the high energy density of the fuels compared to other storage technologies, and also by the low cost of their storage. These techniques are described in detail in several reference articles, such as Lehner et al. (2014), Vandewalle et al. (2015), Walker et al. (2015), Connolly et al. (2016), Götz et al. (2016), Gallo et al. (2016), Kotter et al. (2016), Mesfun et al. (2017), and Simonis and Newborough (2017).

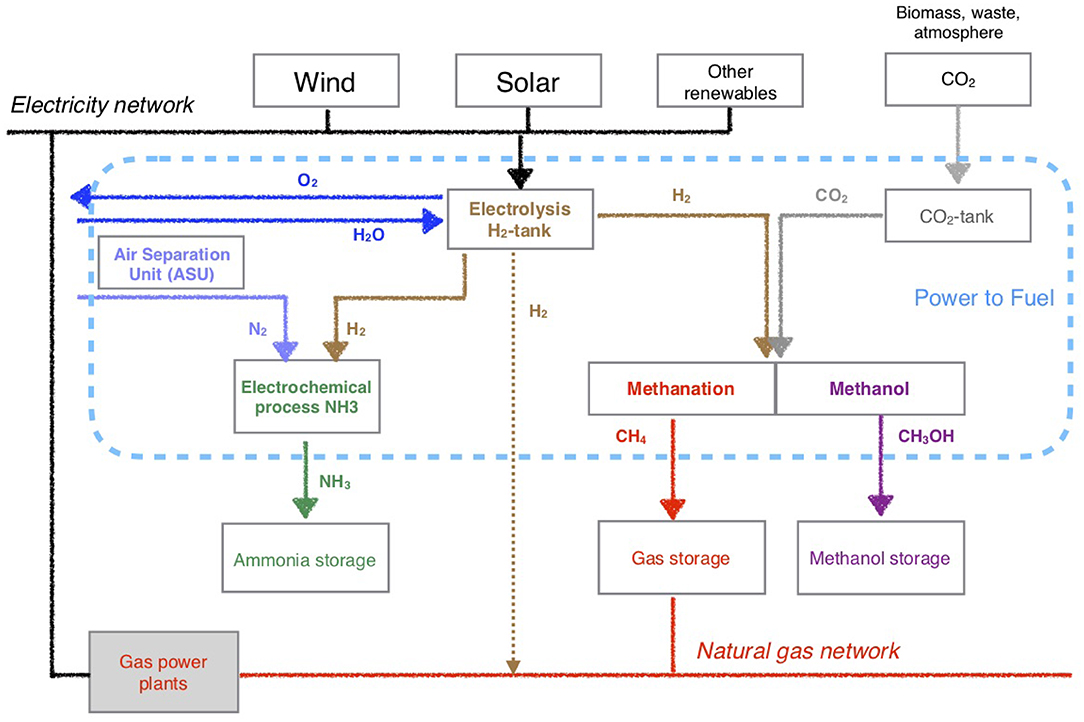

The Power-to-Fuel process involves the use of electricity, produced directly by the wind or the sun, to convert, by electrolysis, water into hydrogen (PtH, H2), the useful product, and oxygen, the by-product. The hydrogen can then react with CO2 to form methane by methanation (CH4), and/or methanol (CH3OH). Finally, the hydrogen produced can also react with nitrogen (N2) from the air, obtained by an ASU (Air Separation Unit) to form ammonia (NH3). In this Power-to-Fuel paradigm, four fuels can therefore be considered as fuels from renewable sources: H2, CH4, CH3OH, and NH3. These “fuels of interest” commonly called “e-fuels,” are selected based on the ease of production by renewable energy sources. In this study, ethanol, dimethylether (DME), oxy-methylene dimethyl ether (OME) and heavier compounds (e-gasoline, e-diesel, e-jet) are not considered because of their longer chemical chains. However, these e-fuels derived also from PtF should not be excluded from the future energy system, especially as intermediate products and/or for mobility. Depending on their chemical properties, these e-fuels may have several potential primary uses for mobility and transport, such as passenger cars, heavy-duty vehicles, shipping, and air transport.

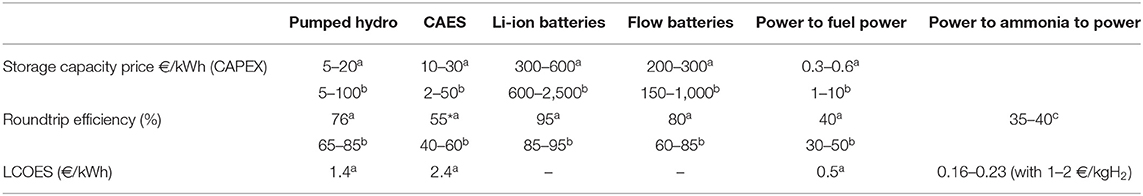

A comparison of the CAPEX (Capital Expenditures), the roundtrip efficiency and the LCOES (Levelized Cost of Energy Storage) of all storages is presented in Table 1. The LCOES method is derived from LCOE, but accounts only for the storage system. According to these data, the efficiency is higher for the battery technology but its CAPEX points to an expensive storage process. Mechanical storage (CAES and PHES) presents a good round-trip efficiency with a reasonable storage cost. The Power-to-X storage is the cheapest with its low LCOES. Such a storage technology is therefore pertinent and to consider when huge energy quantities are to be stored, although the overall efficiency is quite low (40%).

Table 1. Comparison of storage technologies according to the global efficiency, CAPEX and LCOES—based onaHedegaard and Meibom (2012) and Jülch (2016), bGallo et al. (2016), cElishav et al. (2017).

With respect to these observations, the chemical storage is one of the promising options for long term storage of energy.

From all these previous studies, this paper presents a complete evaluation of the energy (section 2) and economic (section 3) costs for the four selected fuels: H2, NH3, CH4, and CH3OH. In this work, their chemical properties are presented, as well as their energy efficiencies for the production, the chemical storage and their electrical restitution. Then, for each fuel, an overall economic cost is performed by taking into account the cost of production (electrolyser, ASU, or carbon capture), storage and transport, as well as that of electricity restitution. It is important to mention that the efficiency data come from previous studies in the literature. Different values could be estimated by other authors. The purpose of our study is to present a global and coherent overview of the energy cost of these four electrofuels, although we know that the large uncertainties affect some parameters.

The chemical properties of the four fuels (H2, CH4, CH3OH, and NH3) are presented in Table 2. All the chemical properties should be taken into account in the global energy cost for these fuels.

One of the advantages of hydrogen is its high gravimetric energy content with a Lower Heating Value (LHV) of 119.9 MJ.kg−1. In addition, H2 is non-toxic and its complete combustion produces only H2O. However, hydrogen as a gas has a low energy density (0.089 kg/m3) and its storage is expensive. To facilitate the storage, four techniques exist: compression at 700 bar (4.5 GJ/m3), liquefaction (8.5 GJ/m3), liquefaction in organic liquids (Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers), LOHC (10 GJ/m3) (Wang et al., 2016; Reuss et al., 2017), or absorbtion to produce hydride metal (15 GJ/m3) (Aslam et al., 2016).

Currently, the main production routes for H2 are based on natural gas (48%), oil (30%), coal (18%) and electrolysis (4%). Its main use is for ammonia production (50%) but hydrogen is also used in refineries (37%), to produce methanol (8%), used as a fuel (4%), and for space application (1%) (Lan et al., 2012). For some applications, the production of hydrogen is justifiable, mainly for direct use without storage. The hydrogen production can be directly injected into the natural gas network with a current European restriction set at 2% in volume fraction (Altfeld and Pinchbeck, 2013; Environment and Energie, 2014), which bypasses partially the storage cost (Qadrdan et al., 2015).

Methane (CH4) is a very interesting fuel for the energy transition due to its proximity to natural gas (more than 80% of CH4). Indeed, transport and storage infrastructures for natural gas are already in place. Moreover, all combustion systems based on natural gas are compatible with CH4. The main disadvantage of this gas is the CO2 needed for the its production and, also, emitted during combustion. Moreover, the methane is a strong greenhouse gas.

The CH4 production comes either from biomass by fermentation or from two main methanation processes: CO + 3 H2 → CH4 + H2O (Fisher-Tropsch process), CO2 + 4 H2 → CH4 + 2 H2O (Sabatier process).

In this study, the combination of electrolysis from renewable electricity and the Sabatier process is considered. This pathway is perceived as the most direct in the context of CO2 reuse.

The main advantage of methanol over the other fuels, is its high volumetric energy density: 15.8 MJ.l−1, being a liquid at ambient temperature and atmospheric pressure. Like methane, the disadvantage of this compound is the CO2 needed for its production and emitted during the combustion process. Today, 85% of the methanol production comes from natural gas: CH4 + 1/2 O2 → CH3OH (Kauw et al., 2015). Still, reactions similar to those of the Fisher-Tropsch and Sabatier processes can be used to produce methanol from hydrogen: CO + 2 H2 → CH3OH and CO2 + 3 H2 → CH3OH + H2O. From syngas (CO + H2), the formation of methanol is energetically more favorable.

In this study, the most direct methanol production from renewable resources (water electrolysis for H2 production and CO2 from combustion process) is analyzed in detail.

Ammonia is an interesting fuel because it does not contain carbon, it is not a greenhouse gas and its flammability region in ambient air is very narrow. At 10 atm, the ammonia is liquid and its LHV equals 12.7 MJ.l−1. Moreover, NH3 contains a high volume of H2 and can be used as a hydrogen storage molecule. The drawbacks concern its significant toxicity by inhalation and its corrosive effects on several metals. Moreover, the combustion of NH3 produces NOx emission and can also damage steel combustion appliances. The production of NH3 comes mainly from the Haber-Bosch process: N2 + 3 H2 → 2 NH3. Another route of formation from water exists: 2 N2 + 6 H2O → 4 NH3 + 3 O2 (Lan et al., 2012) but at a relatively early stage of development. The Haber-Bosch process, the most common and well-known, will be considered in this study as the ammonia production process.

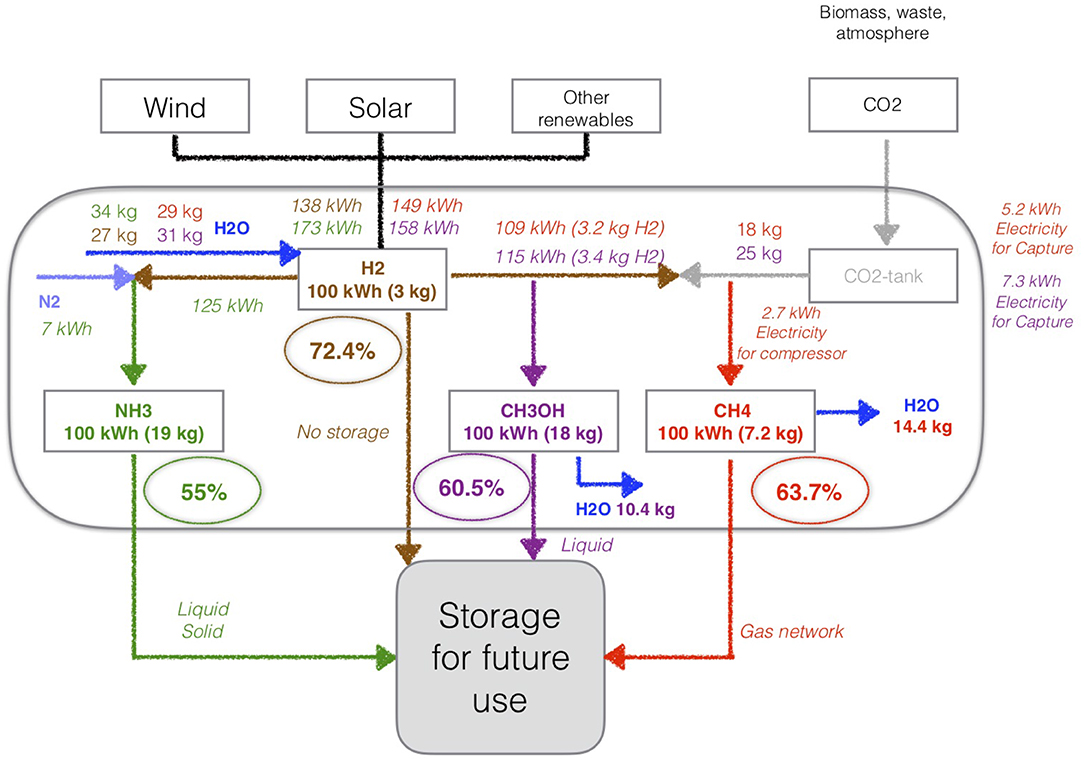

To produce the four fuels (hydrogen, methane, methanol, and ammonia) from renewable energy, state of the art industrial applications use different production pathways (see Figure 2). To have a fair and clear comparison across these pathways, we considered an output of 100 kWh for each fuel. Of course, this does not provide information about the production size which may vary according to intrinsic production parameters (e.g., renewable electricity available, critical size for the production unit).

Figure 2. Energy efficiency of production for hydrogen (H2), methane (CH4), methanol (CH3OH), and ammonia (NH3) from the renewable energy sources—based on Connolly et al. (2015, 2016) and Matzen et al. (2015).

To produce 100 kWh of hydrogen (H2), 138 kWh of electricity from renewable energy sources and 27 kg of water (H2O) are needed for the endothermic water electrolysis:

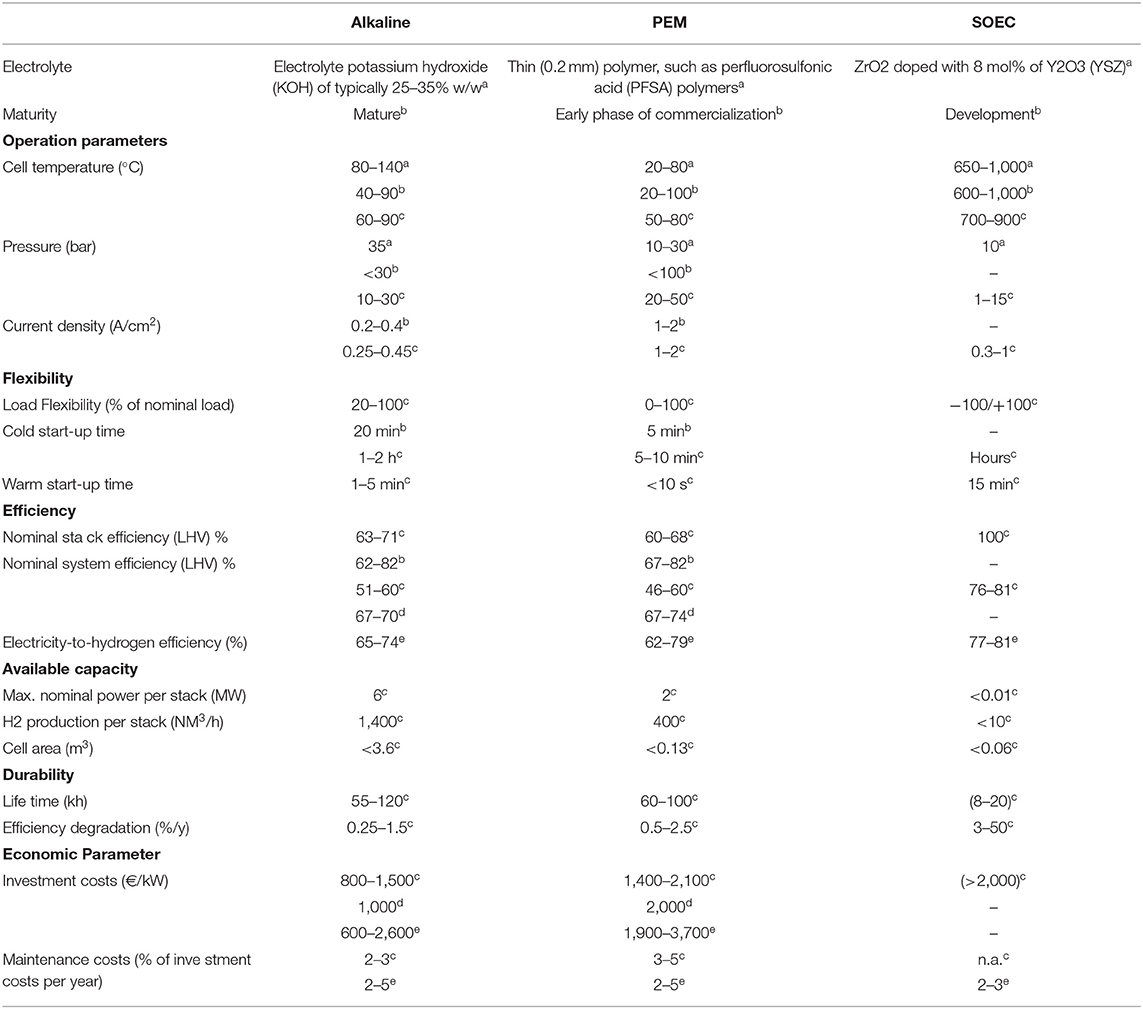

Moreover, the efficiency of the H2 production from water depends on the nature of the electrolyser. Three main types of electrolysers are considered: Alkaline, Proton Exchange Membrane (PEM) and Solid Oxide Electrolytic Cell (SOEC). Several studies present in detail the characteristics of these electrolysers (Schiebahn et al., 2015; Brynolf et al., 2018; Ghaib and Ben-Fares, 2018). A recent review of Buttler and Spliethoff (2018) provides a comprehensive and very detailed overview of the current status for these three electrolysers, for use in power-to-fuel. The three technologies are briefly described below:

The alkaline electrolyser is composed of two electrodes immersed in a liquid electrolyte separated by a membrane. The electrolyte is recirculated for removal of product gas bubbles and heat either by pumps or by natural circulation due to the temperature gradient. The electrolyte is stored in two separate tanks for H2 and O2, which also serve as gas-liquid separator. The carrier ions are, in this case, OH−. The reactions at the electrodes are given by two half-reactions: oxidation (anode) and reduction (cathode):

The PEM separates two half-cells, and the electrodes are usually mounted on the membrane. The polymer electrolyte membrane allows a very low permeation, and a higher purity of hydrogen than with an alkaline process. In addition, the solid electrolyte allows a compact module design. The carriers ions are protons H+ and the reactions at the electrodes are:

The SOEC operates at high temperatures (700–900°C). The higher temperature increases the efficiency of the process compared to alkaline and PEM, but implies a high resistance for the stability of the material. Like PEM, SOEC is composed of a solid electrolyte. It begins to be permeable to O2− ions, at high temperature. At the electrodes, the reactions are:

For all the fuels, we took the efficiency of the water electrolyser (alkaline electrolyser) determined by Connolly et al. (2015): 72.4% (ratio of H2 energy output to input electric energy). The hydrogen output gas produced from this electrolyzer is assumed highly pure (>99.9%) (Atsonios et al., 2016).

For the formation of methane and methanol, carbon dioxide is needed and its energy costs depends on the capture technique used. Three main capture processes are presented in section 3.3: pre-combustion capture, oxy-fuel capture and post-combustion capture. In recent years, these different capture methods have been studied in detail (Gibbins and Chalmers, 2008; Kanniche et al., 2010; Pires et al., 2011; Azapagic and Cue, 2015); a recent review is presented by Abdul et al. (2017). The application of these capture techniques depends on the combustion system, the temperature, the nature of the initial mixture and the concentration of CO2 (Abdul et al., 2017). The purity of the CO2 captured can reach 99.98%, depending on the capture process and the cost of CO2 purification (Matzen et al., 2015).

To produce 100 kWh of methane, the methanation process (Sabatier) requires: 109 kWh of H2, 5.2 kWh of electricity for the CO2 capture (post-combustion technology) and 2.7 kWh of electricity for the compression (Figure 2):

The reaction is exothermic, and releases a large amount of heat that must be evacuated to avoid damaging the reactor. The process is promoted at high pressure and low temperature.

The total efficiency of the process (water electrolysis and methanation) is equal to 63.7% and 14.4 kg of H2O are produced and can be reused (Connolly et al., 2016). The purity of the CH4 obtained from the methanation process depends on the purity of the carbon dioxide. A CO2 conversion of nearly 98% is required to reach a methane content >90%, while a CO2 conversion of 99% corresponds to a methane content of 95%. Inert gases or hyperstoichiometric H2/CO2 ratios prevent reaching higher levels of methane (Götz et al., 2016).

The methanol process from renewables can be used to form CH3OH, with 115 kWh of H2 and 7.3 kWh of electricity for the CO2 capture, with a total efficiency of 60.5% (Connolly et al., 2015) (Figure 2):

During this process, 10.4 kg of water are produced. In order to achieve high levels of purity in the methanol (> 99.2%), a special purification technique, similar to the RectisolTM process, is followed to avoid the production of by-products, such as hydrocarbons (Atsonios et al., 2016). The technology of this industrial application is described in the work of Atsonios et al. (2016).

The latest fuel of interest is ammonia (NH3), a carbon-free fuel, and it can be produced from H2 (from water electrolysis) and N2 obtained from air with an ASU (Air Separation Unit), when combined at around 400–600°C and 200–400 atm (Haber-Bosch process):

The production of 100 kWh of NH3 needs 7 kWh of N2 with the ASU, 125 kWh of H2 and 34 kg of water (Figure 2). The total efficiency is about 55% (Fuhrmann et al., 2013). The NH3 purity can reach a value of 99.999%, if the H2 and N2 reactants are themselves pure (Fuhrmann et al., 2013; Matzen et al., 2015).

During these processes, the electrolysis of water also produces oxygen as a by-product. One kg of H2 produced allows the formation of 8 kg of O2, due to the reaction H2O = H2 + 1/2 O2. Oxygen is a valuable product with several applications in the medical sector, in the iron and steel industry and in other industrial processes. O2 is an added-value in the water electrolysis and it can be captured and stored, thanks to its very high purity (>99.2%) (Atsonios et al., 2016).

Overall, synthetic fuels produced with PtF (hydrogen, methane, ammonia, methanol) are significantly higher in quality, during their combustion, than conventional fossil fuels, which can reduce the constraints on conventional exhaust gas treatment systems (catalytic converters, particulate filters). The purity of the hydrogen produced by PtF is 99.999% (Matzen et al., 2015), that of methane is between 90 and 92% (due to inert gases or hyperstoichiometric H2/CO2 ratios) (Er-rbib and Bouallou, 2014; Götz et al., 2016) and that of methanol and ammonia around 99.99% (Matzen et al., 2015). The use of these pure fuels, of better quality, also increases the efficiency of combustion in the existing systems.

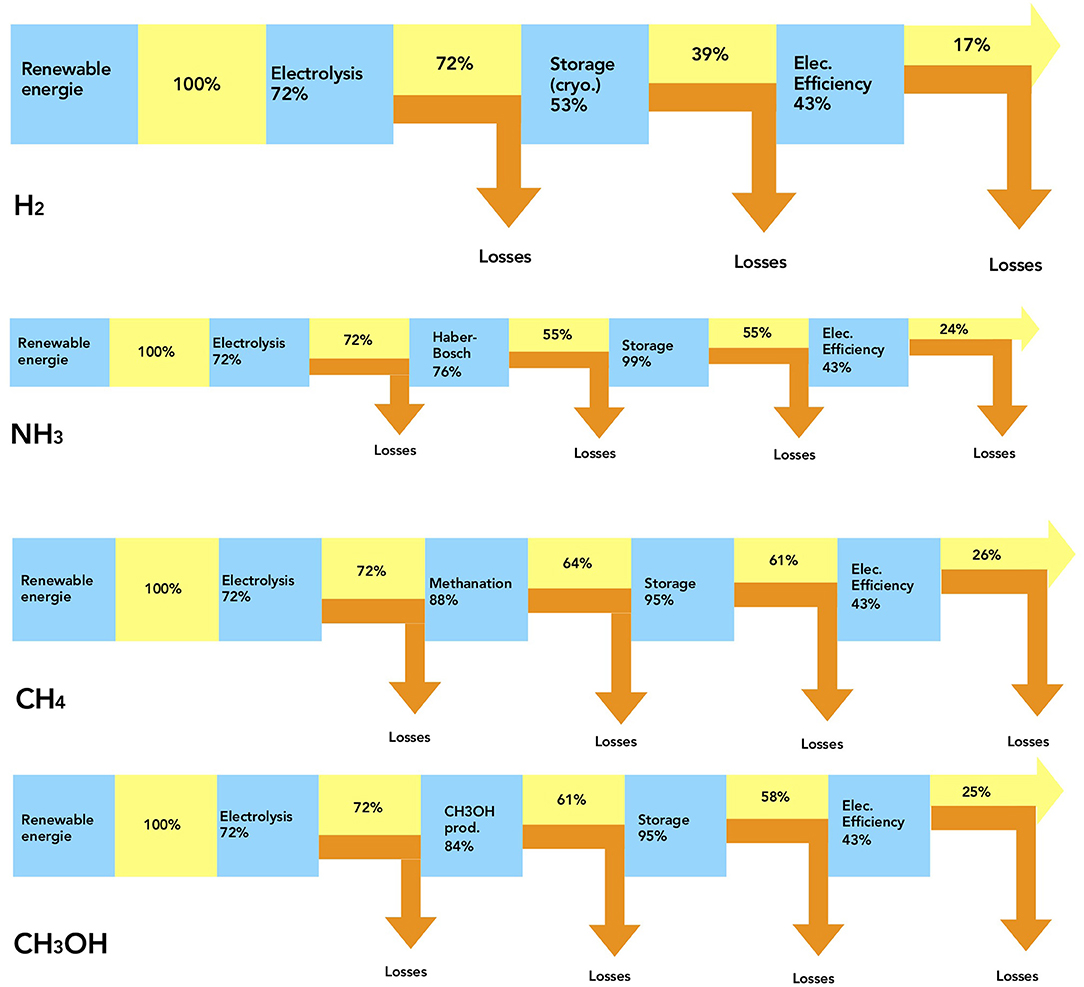

To compare the global energy cost of each fuel (H2, CH4, CH3OH, and NH3), several stages are considered: production of H2, fuel production, storage, transport and electrical restitution. Different storage costs are considered because of the different chemical properties of each fuel. In this work, the efficiency of the conversion to electricity is set at 43% (Stock and Bauder, 1990) for these four fuels. Depending on the nature of the fuel and the technical process of restitution, this efficiency can be improved.

Hydrogen can be stored in different phases: compressed gas, liquid (cryogenic, cryo-compressed, organic compound), high pressure solid, sorbents, hydrides (metal, complex, chemical).

Considering the first source of electricity obtained from 100% of renewable resources (wind turbine, photovoltaic panel…), the efficiency of water electrolysis is evaluated at 72.4% and the liquid storage is estimated at 53%—with a cost of liquefaction (atmospheric pressure and −254°C) about 44.7% of the energy contained in the gas phase and with a storage cost of 2.3% due to losses (Olson and Holbrook, 2007). Then, considering the electrical restitution at 43%, the net return of electrical energy for hydrogen is thus around 17%.

From this calculation, the energy in the stored liquid H2 contains only 39.1% of the input electrical energy. In this case, the hydrogen cryogenic storage (liquid phase) is very expensive energetically. It is thus better to avoid liquid storage and to prefer the compressed gas storage, to inject it into the natural gas network (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Electric energy restitution, cumulative and step efficiency for H2, NH3, CH4, and CH3OH—based on Olson and Holbrook (2007), Bartels (2008), Connolly et al. (2014, 2015, 2016), and Matzen et al. (2015).

Storage of ammonia is straightforward with a liquid phase obtained at atmospheric pressure and −33°C, or at ambient temperature and 8 bar. Only 0.1% of the energy is needed to liquefy NH3 from the gas phase. Storage of liquid ammonia is not energetically expensive with only 0.6% on the total NH3 energy content (Olson and Holbrook, 2007). NH3 can also be stored in solid phase (metal amino complexes, urea). A comprehensive work on ammonia is presented in the report of the Institute for Sustainable Process Technology (ISPT), published in 2016 (Institute for sustainable Process Technology, 2016).

To estimate the power-to-NH3-to-power, different energy efficiencies are taken into account: 72.4% for the electrolyser (production of hydrogen), 76% for the Haber-Bosch process, 99.3% for the storage, and 43% for the electrical efficiency in a SI engine. The total electrical restitution is thus equal to 24.4% (Figure 3).

CH4 can be stored as a gas at different pressures, or as a liquid. The liquefaction of methane is less expensive than that of hydrogen, with only 10% of the initial energy, at atmospheric pressure and −162°C. To compress and store methane up to 210 bar, the energy cost is lower, about 5% of the initial energy (Bartels, 2008).

To calculate the total energy efficiency of renewable resources, we take into account the efficiency of hydrogen production equals to 72.4%, the methanation process at 87.9%, the CH4 storage (in gaseous phase at 60 bar, similar to the gas network) at 95%; and electric efficiency with a SI engine at 43%. Thus, the total electrical energy restitution of methane is about 26% (Figure 3).

For methanol, which is in liquid state at atmospheric pressure and ambient temperature, storage is easy and very stable. Moreover, its transport is very affordable with negligible losses. From renewable resources, hydrogen is still produced with an efficiency of 72.4%. Then, the efficiency of the methanol process is equal to 83.5%, the storage and transport to 95%, with an efficiency for the restitution of about 43% in a SI engine. So, the net return of electrical energy from methanol is about 24.7%, slightly lower than that of methane (Figure 3).

The stage efficiencies are summarized in Figure 3, for the four fuels. According to all these results, the storage step is underlined as crucial for hydrogen, in the total electrical efficiency. Moreover, the efficiency of the conversion to electricity is set at 43% for these four fuels but this efficiency can be improved depending on each fuel.

In the context of the energy transition, Power-to-Fuel (PtF) technology appears to be a promising option in combination with batteries. Indeed, some studies claim that long-term storage (PtF type) will be unavoidable to reach 70–80% of renewable energy share in the electricity production (Jentsch et al., 2014; Mathiesen et al., 2015; Connolly et al., 2016; Limpens and Jeanmart, 2018). PtF could be used not only as a technique of electricity storage, but also as a production of fuels for transport over long distances (Environment, 2016), as well as other industrial sectors.

In this study, each step of the power-to-fuel-to power is analyzed (Figure 4): the electrolyser (investment, stack replacement, O&M, electricity), the ASU (investment of ASU, O&M ASU), the CO2 capture, and the fuels costs (production—with investment and O&M for fuel synthesis, storage and transport, electrical restitution).

Figure 4. Schematic pathway of Power-to-Fuel: production of H2, NH3, CH4, and CH3OH from renewable resources; and integration to gas and electrical networks.

Based on previous works (Schiebahn et al., 2015; Balcombe et al., 2018; Brynolf et al., 2018; Buttler and Spliethoff, 2018; Ghaib and Ben-Fares, 2018), a comparison of the three electrolyser technologies is presented in Table 3 as follows: the nature of the electrolyte, the current maturity, the operation parameters (temperature, pressure, density), the flexibility, the efficiency, the available capacity, the durability, and the economic parameters.

Table 3. Parameters of water electrolysis technologies: alkaline, PEM and SOEC—based on aBalcombe et al. (2018), bGhaib and Ben-Fares (2018), cButtler and Spliethoff (2018), dSchiebahn et al. (2015), eBrynolf et al. (2018).

Alkaline is considered as mature technology, it is currently the cheapest and most reliable technology (Ghaib and Ben-Fares, 2018). It has been available for industrial purposes for many years. However, its disadvantages concern the minimum load (20%) and the relatively long cold start time (10 min to h). PEM is in the early phase of commercialization and is thought to be the best choice for PtF plants in order to absorb intermittent amounts of energy. Indeed, the PEM electrolyser could reach full power from the cold start in a few minutes (Balcombe et al., 2018). The main disadvantage is the cost of the catalysts, with a noble material (platinum group metal) (Brynolf et al., 2018). Finally, the SOEC has the potential to increase the efficiency of hydrogen production in the future, but it is in the development phase.

According to the review of Buttler and Spliethoff (2018), the price ranges for each electrolyser are: Alkaline between 800 and 1,500 €/kW, PEM between 1,400 and 2,100 €/kW and SOEC above 2,000 €/kW.

A possible upgrading route for the O2 produced from water electrolysis is to use it, instead of air, in the combustion of synthesized methane, after dilution with CO2. Oxy-combustion increases the energy efficiency of a gas turbine combined cycle above 60%, compared to 40% of energy efficiency with a simple power generation by a steam turbine (Hashimoto et al., 2016).

According to the nature of the electrolyser, the oxygen cost will be impacted. Indeed, one sub-product of the water electrolysis is oxygen, with a high purity whose exact value depends on the process configuration. From a Report of Tractebel in 2017 (Tractebel and Hinicio, 2017), the prize of O2, in gas phase and produced from alkaline electrolyser, is estimated at 20–35 €/tonO2 for the on-site production oxygen, 30–40 €/tonO2 for oxygen delivered by pipeline, and 80 €/tonO2 for oxygen delivered by truck. Atsonios et al. (2016) estimate the oxygen selling price at 87.4 €/tonO2 produced from alkaline electrolyser, including the compression, cooling and liquefaction costs.

The composition of air is 78% nitrogen, 21% oxygen, and 1% argon. These compounds can be separated by an Air Separation Unit (ASU) thanks to their different boiling points: N2 at −196°C, O2 at −183°C, and Ar at −186°C. This process is described in several articles, mainly on the ASU cryogenic process (Smith and Klosek, 2001; Darde et al., 2009; Banaszkiewicz et al., 2014; Zhang et al., 2014; Mehrpooya et al., 2016).

The ASU process is only used for the ammonia production and the ASU cost is estimated at 1/4 of the total capital required for an entire conventional ammonia plant by Bartels (2008).

Recently, Bañares-Alcántara et al. (2014) detailed the cost of each step for a production of ammonia of 750 tons per year (with a service factor of 75%). From this work, the ASU process is evaluated at 340 €/kW, including in a Mini Ammonia Production Unit, from Proton Ventures, with a total cost (CAPEX and OPEX) around 6,780 €/kW. This unit is able to produce 3 tons/day of anhydrous ammonia with a purity of 99.9%. The costs of the ASU process are very sensitive to the size of the production unit.

The main sources of CO2 come from carbon capture, biomass (by fermentation, gasification, or combustion), industrial processes (such as by-product), and air.

The CO2 capture is already well-developed and three processes are used in industrial installations: post-combustion capture, pre-combustion capture and oxy-fuel capture. These capture techniques are described in detail in several articles in the literature (Gibbins and Chalmers, 2008; Kanniche et al., 2010; Atsonios et al., 2016; Brynolf et al., 2018):

- The post-combustion capture: the objective is to remove CO2 from the combustion products before the release of the gas into the atmosphere. The most common solution is the chemical absorption technique with amine scrubbing, at low temperature (50°C). The solvent is regenerated by heat (120°C), before being cooled and recycled to the process. This CO2 capture is the most mature technology in the short-midterm and it has already been implemented in large scale applications. Some others technologies exist in the post-combustion process: physical absorption, adsorption, gas particle reactions, membrane separation and cryogenic separation (Song et al., 2018).

- The pre-combustion capture: Removing the CO2 before the combustion process is not the classic method. However, all types of fossil fuels can be gasified, which means partially oxidized or reformed with the addition of oxygen, at high pressures (30–70 atm). The produced synthesis gas is composed mainly of CO and H2. By the addition of water and the reduction of the temperature, the equilibrium reaction of “water-gas shift” allows the formation of CO2: CO + H2O = CO2 + H2. The separation process of CO2 uses a solvent, at high pressure. This capture technique is less efficient than post-combustion because of the energy involved in the water-shift reaction.

- The oxy-fuel recycle combustion capture: The fuel (gas and coal) is burned in a mixture of oxygen separated from the air, and recycled flue gases. A mixture of flue gas is thus produced, composed of mainly CO2 and water. This water is condensed and easily removed from CO2 during a compression process. For coal, oxides of nitrogen and sulfur (NOX, SOX) and other pollutants must be removed from the product gas prior the CO2 compression process.

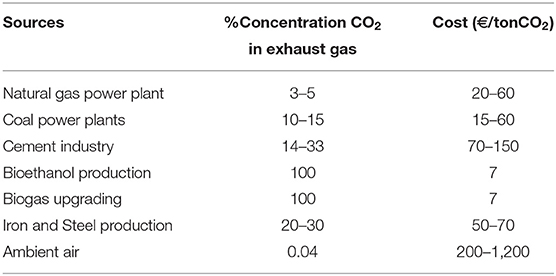

The price of CO2 depends on the capture process and the sources of production. Table 4 presents CO2 costs according to production sources and their concentration. The concentration of CO2 in the ambient air is very low (0.04%), and its extraction very expensive with a price of up to 1,200 €/tonCO2. From the biogas upgrading and the bioethanol production, the CO2 concentration can reach almost 100% in exhaust gas, which decreases the cost to 7 €/tonCO2.

Table 4. CO2 costs according to different sources and their concentration—based on Gibbins and Chalmers (2008), Ranjan and Herzog (2011), Schiebahn et al. (2015), Atsonios et al. (2016), Bailera et al. (2016), Brynolf et al. (2018), Ghaib and Ben-Fares (2018), and Song et al. (2018).

Currently, in the cement plant output, the carbon capture cost can be evaluated at 70 €/tonCO2, but the objective is to decrease it below 40 €/tonCO2 in 2020 (US DOE).

To compare the suitability of the four fuels, the economic costs of production, storage and transport need to be assessed. In the recent review by Brynolf et al. (2018), the costs of production for H2, CH4 and CH3OH are compared with specific hypotheses on prices. To evaluate the cost of ammonia and compare it with other fuels, the same assumptions as in Brynolf et al. (2018) are considered for a synthesis plant size of 5 MW:

- Electrolyser cost (alkaline): 1,100 €/kWelect

- Electricity price: 50 €/MWh

- Water cost: 1 €/ton

- Carbon capture cost: 30 €/ton

Ammonia production costs come from the study of Bañares-Alcántara et al. (2014). They estimated ammonia costs for a plant size of 0.59 MW (125 kgNH3/h at 75% service factor):

- ASU cost: 200 k€

- Haber Bosch process: 1,600 k€

The capital cost of a chemical plant can be approximately related to the capacity by the equation: C2/ C1 = (P2/P1)k with C2, capital cost of the plant with the capacity P2; C1, the capital cost of the plant with the capacity P1; k is the scaling factor estimated at 0.7 (Trop and Goricanec, 2016).

For scaling the values of Bañares-Alcántara et al. (2014) for NH3 with the plant size of 5 MW (Brynolf et al., 2018), and with the same capacity factor (0.8), the C2/C1 ratio is equal to 4.46.

The electrolyser cost from Bañares-Alcántara et al. (2014) must be adapted to the same capacity plant of 5 MW, the efficiency being evaluated at 65% (Brynolf et al., 2018). From Bañares-Alcántara et al. (2014), the electrolyser cost is equal to 1,360 k€ for a 0.59 MW power plant. The correction factor is evaluated at 6.22, by using the scaling factor for a capacity plant of 5 MW. Moreover, the H2 quantity needed for the production of NH3 leads to an additional factor of 1.14.

So, the global factor of 6.22 × 1.14 is used to calculate, for a plant of 5 MW, the cost of the electrolyser, the Air Separation Unit (ASU) and the Haber-Bosch process.

To evaluate the cost of the electricity contained into each fuel, the LCOE (Levelized Cost of Electricity) is calculated for each step of production, storage, transport and electrical restitution (Equation 1):

with: It: investment expenditures in the year t, Mt: operations and maintenance expenditures in the year t, Ft: fuel expenditures in the year t, Et: electrical energy generated in the year t, r: discount rate, n: expected lifetime of system.

In the project of Brynolf et al. (2018), the discount rate (r) is evaluated at 5%, the expected lifetime of the systems (n) at 25 years, the yearly operation and maintenance expenditures (Mt) are estimated at 4% of capital cost. Moreover, the electrical energy generated for 1 year (Et) is calculated from the plant power (5 MW), the number of hour in 1 year (8,760 h) and the capacity factor (0.8), and it is equal to 35.040 MWhfuel.

The expenditures are the cost of the electrolyser (investment, electrolyser stack replacement), the air separation unit (ASU), the electricity, the investment for the fuel synthesis (Haber-Bosch process, methanation, methanol process), and the OPEX.

Figure 5 presents the total cost of production for each fuel, in €/MWhfuel. These results are calculated according to all the previous hypotheses and only take into account the production without storage and transport costs. From Figure 5, ammonia is the most expensive fuel with a cost of 240 €/MWhNH3 due to the Haber-Bosch process, then, methanol with a cost of 210 €/MWhCH3OH, methane with 203 €/MWhCH4 and hydrogen with a cost of 138 €/MWhH2. Hydrogen is the cheapest fuel because its production does not require any additional process.

With respect to these results, for the four fuels, the electrolysis process appears to be, by far, the most expensive part of the fuel production due to the electricity price.

Nevertheless, these production costs depend on the initial hypotheses. For example, if the cost of carbon capture is estimated at 1,000 €/tonCO2 (price to capture CO2 from ambient air) instead of 30 €/tonCO2 considered in this project (price to capture CO2 from a plant), the total production cost of CH4 and CH3OH will increase up to 406 €/MWhCH4 and 491 €/MWhCH3OH, respectively. In this case, hydrogen and ammonia become more interesting than hydrocarbons, due to their lower prices (Figure 5).

Moreover, the production costs depend on the technology used. For example, if the PEM electrolyser is chosen instead of the alkaline one, with a price of 2,400 €/kW (Brynolf et al., 2018) instead of 1,100 €/kW (Brynolf et al., 2018), the total production cost will increase for the four fuels (Figure 6). Indeed, the hydrogen production increases from 138 €/MWhH2 to 195 €/MWhH2, the ammonia from 240 €/MWhNH3 to 304 €/MWhNH3, the methane from 203 €/MWhCH4 to 277 €/MWhCH4; and the methanol cost from 210 €/MWhCH3OH to 281 €/MWhCH3OH. The comparison cannot be performed with the SOEC electrolyser due to the high uncertainties on prices. Indeed, this technology is at the development stage. As of today, the production cost would drastically increase compared to alkaline and PEM electrolysers.

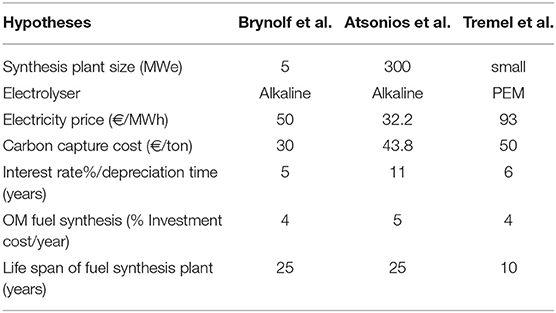

Three previous studies working on the production costs are compared to emphasize the sensitivity to the initial hypotheses (Table 5). The study of Brynolf et al. (2018), in 2018, focuses on the electrofuels for the transport sector (H2, CH4, and CH3OH). In 2016, Atsonios et al. (2016) investigated the technical and economic aspect of methanol production. In 2015, Tremel et al. (2015) studied the production costs of liquid and gaseous fuels (H2, NH3, CH4 and CH3OH).

Table 5. Hypotheses for the production costs—based on Tremel et al. (2015), Atsonios et al. (2016), and Brynolf et al. (2018).

Different hypotheses are considered in each study. From the Atsonios et al. study (Atsonios et al., 2016), the capacity factor is evaluated at 85%, instead of 80% in the work of Brynolf et al. (2018). In the work of Tremel et al. (2015), the hydrogen cost is estimated at 3,000 €/ton. Due to all these difference of costs, the production value of each fuel is quite different but the trend of the production cost between the different fuels is the same. The production costs for H2, NH3, CH4, and CH3OH from the three literature studies (Tremel et al., 2015; Atsonios et al., 2016; Brynolf et al., 2018) are presented in Figure S1 with the analysis of NH3 from our work based on hypotheses of Brynolf et al. (2018). From these comparisons, ammonia is still the most expensive fuel, followed by methanol, methane and hydrogen. The additional costs for storage and transportation could influence the total costs.

After the production, each fuel should be stored and transported to the place where it will be used. The storage and transport of fuels require a specific energy, which varies because of the different properties of the fuels (see Table 2). The estimations of the storage and transport costs are taken from several studies from the literature (Bartels, 2008; Rivarolo et al., 2014; Connolly et al., 2016; Jülch, 2016; Laborelec, 2016; Reuss et al., 2017). H2 is the most difficult to store due the properties of the molecule. Recently, Reuss et al. (2017) studied the hydrogen supply chain model, for three storage processes: in gaseous phase (compressed hydrogen), in liquid phase and in LOHC (Liquid Organic Hydrogen Carriers). In their work, different stages are considered, such as conversion, storage (in a cavern or in a tank) and transport of H2 (by truck or by pipeline). They estimated a conversion cost for hydrogen between the production and the storage stage, but also between the storage and the transport. Their article provides a comprehensive overview of infrastructure technologies and economics of the hydrogen supply chain.

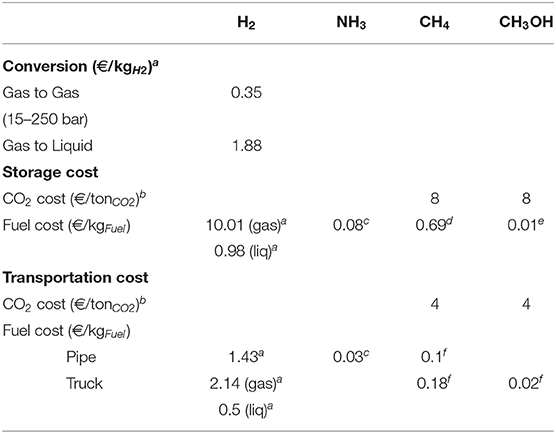

In our study, only two forms of hydrogen storage (gaseous and liquid) are considered and only one form for NH3 (gas), CH4 (gas), and CH3OH (liquid), and the transport is estimated by truck or pipeline, over a distance of 250 km. According to the data of the literature, the costs for the H2 conversion phase, for the storage and for the transport are presented in Table 6, with the costs for NH3, CH4, and CH3OH. The cost of gas compression is included in the cost of storage and transport.

Table 6. Storage and transportation costs—based on aReuss et al. (2017), bLaborelec (2016), cBartels (2008), d Connolly et al. (2016), eEstimated, fRivarolo et al. (2014).

A global cost for each fuel is generated with the data from Table 6 added to the production costs. The initial hypotheses are the same as previously and taken from Brynolf et al. (2018).

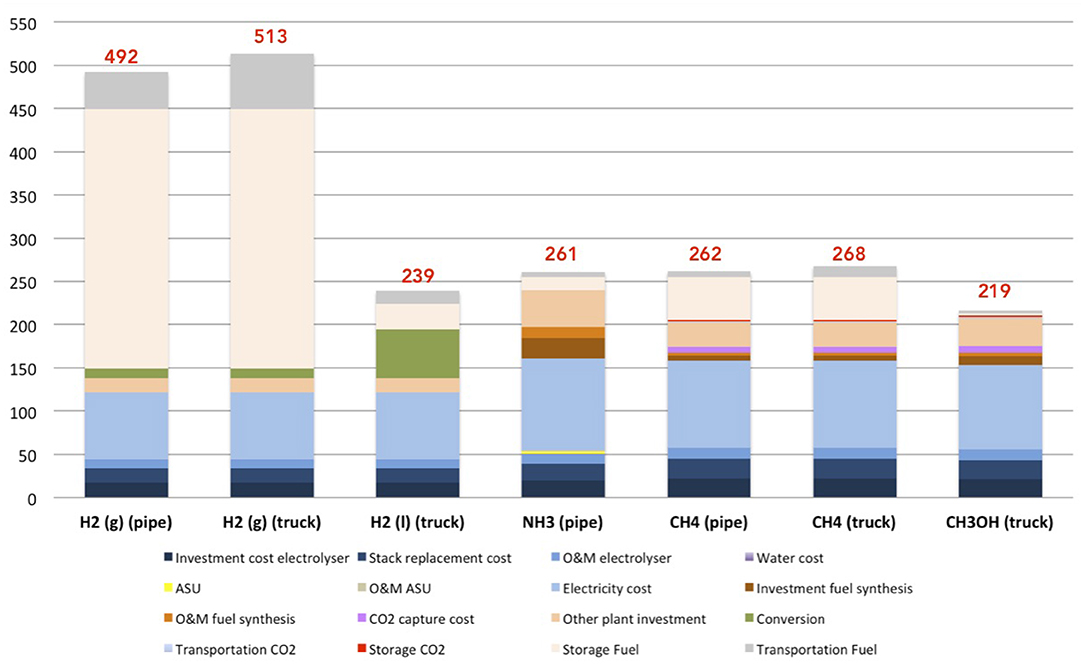

Figure 7 presents the overall cost for each fuel, in different phases (gas or liquid) and for different transport means (truck or pipeline). From these results, methanol is the cheapest fuel produced from the renewable resources with a cost of 219 €/MWhCH3OH.

Figure 7. Global costs (production, storage, and transportation) for each fuel in €/MWhfuel, with 30 €/tonCO2.

Hydrogen in gas phase, transported in a truck is the most expensive (513 €/MWhH2). Hydrogen in gas phase transported by pipeline is evaluated at 492 €/MWhH2, and 239 €/MWhH2 in liquid phase (in a truck). Storage of hydrogen in gas phase is the most expensive part of the process. This cost is due to the huge volume of storage required for 1 kg of hydrogen gas. The total cost of ammonia is moderate at 261 €/MWhNH3, by pipeline. Methane transported in pipeline costs 262 €/MWhCH4, and 268 €/MWhCH4 transported in a truck.

According to initial hypotheses, a relative comparison can be presented: for example, if the cost of carbon capture is evaluated at 1,000 €/tonCO2 as in ambient air (instead of 30 €/tonCO2 as Brynolf et al., 2018 estimated), the global costs increase up to 466 €/MWhCH4 for CH4 (pipeline), 472 €/MWhCH4 for CH4 (truck) and 500 €/MWhCH3OH for CH3OH. In this case, methanol is considered the most expensive carbon-fuel, due to the carbon capture price. The cost of carbon capture is an important parameter for the global cost, due to the significant impact for hydrocarbons, such as methane and methanol, as presented in Figure S2.

With regard to these results, the storage of H2 in gas phase is the most expensive process of the hydrogen cost. For other fuels, the electrolysis process (formation of H2) remains the most expensive part of the fuel production, as long as the CO2 cost is <196 €/tonCO2.

To estimate the cost of the electric restitution, a gas engine is considered in this work, with again some hypotheses. The CAPEX of electricity restitution is evaluated at 400 €/kW installed with a capacity of 5,000 h pear year. The lifetime of such an engine is 12 years. Thus, two gas engines will be needed throughout the lifetime of the synthesis facility (25 years). And, the discount rate is estimated at 7%, and 5% for the OPEX. The LCOE indicates a cost of 11.35 €/MWhfuel and 7.04 €/MWhfuel for the OPEX cost.

All previous costs for fuel production, storage and transport must be added to these costs for the electricity restitution. With the same hypotheses as above (see sections 3.4.1 and 3.4.2), the overall costs for each fuel, power-to-power, can be evaluated at 510 €/MWhH2 for H2 in gas phase in pipe and 532 €/MWhH2 for gas H2 in truck, for the liquid phase at 257 €/MWhH2 in truck; 279 €/MWhNH3 for NH3; 281 €/MWhCH4 for CH4 in pipe and 287 €/MWhCH4 in truck; and finally, 237 €/MWhCH3OH for CH3OH in truck.

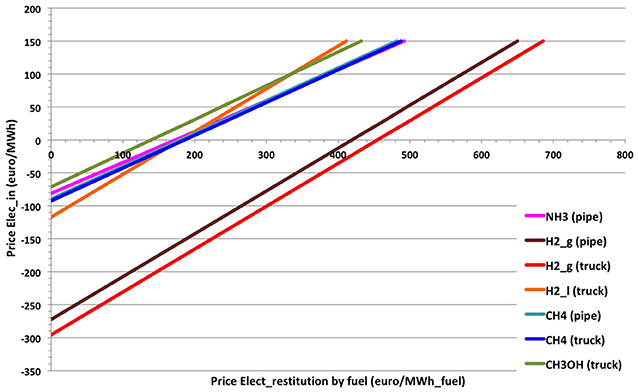

A comparison is presented in Figure 8 to highlight the evolution of the cost of the electricity produced from each fuel based on the price of electricity consumed for their production. Note: The different prices of the input electricity concerns only the electricity required for the electrolysis process (production of H2). The electricity costs used for the others, such as Haber-Bosch, ASU, methanation, methanol process, conversion, storage, and transport, are not taken into account because of the complexity of their assessment. Nevertheless, the required electricity is mainly used in the electrolysis process, presented in Figure 8 and is representative of the electricity cost for the global process, from production to electrical restitution.

Figure 8. Price of electricity restored by fuel, according to the initial electricity price injected in the global process.

From Figure 8, the electrical restitution from hydrogen in gas phase is expensive regardless the cost of electricity. This means that for a very low negative price of the electricity injected (about −280 €/MWh), the electricity restitution from hydrogen could be produced free of charge. This negative price of electricity injected can be reduced to −60 €/MWh for methanol.

In addition, the slope for H2 (liquid and gas) is different due to the large fraction of the electricity cost in the total cost which is lower for the other fuels. This can lead to a reversal of the trend from a certain price of electricity. For example, the price of electricity produced from methanol is cheaper than the liquid hydrogen (stored in truck) one. But, for a price of the consumed electricity >99.5 €/MWh, electricity restituted from methanol becomes more expensive than that restored from liquid hydrogen.

The objective of this study is to present the energy and economic costs for the production, storage and transport of H2, NH3, CH4, and CH3OH. These costs are different depending on the chemical properties of the molecule, the production process, the storage and the transport. To improve this work, the uncertainties of each parameter should be taken into account and additional analysis should be performed to accurately assess these costs. Currently, several processes are still in the development phase and their costs are quite difficult to determine with precision. In this section, for each fuel, an optimized scenario is proposed to reduce the cost and increase the global energy efficiency.

H2 is a small molecule, produced from renewable electricity with an electrolyser. Considering the different electrolyser technologies, the hydrogen production is cheaper with the alkaline one. And the cheapest global cost of H2 is evaluated at 239 €/MWhH2, by storing hydrogen in liquid form and by transporting it by truck.

Hydrogen can be used to produce electricity in a fuel cell or in a conventional gas turbine. But the main disadvantage of H2 is the gas phase storage, which is very expensive. The best H2 application is to produce hydrogen in a local plant and use it directly to form CH4 or CH3OH. The storage of H2 in a small buffer would still be acceptable. Another application of H2 is its connection to the natural gas network with up to 2% of energy content. Similarly, hydrogen can be used for the production of ammonia.

The other option is the liquefaction of hydrogen, because of its lower costs for storage and transportation. But the conversion between gas and liquid phases of H2 is very expensive and the interest is quite limited. This liquefaction should thus be used only to transport H2 over very long distance, with a specific purpose, such as the mobility (hydrogen cars, buses, trucks).

NH3 is a toxic and corrosive molecule but with a suitable technology, this fuel can be used in several combustion processes, mainly mixed with H2 to improve the flammability. As a reminder, liquid ammonia contains more hydrogen than liquid hydrogen, so it can be used as a hydrogen storage molecule.

The production of NH3 involves an electrolyser, an ASU and an Haber-Bosch processes. This last technology is not negligible in the final cost but the most expensive process remains the electrolysis.

One of the disadvantage of NH3 is the lack of a grid for this fuel in Europe, unlike the USA where some partial grids are already present. Fortunately, it can be stored in a tank and its storage and transport are very affordable, with a high energy density. Still, its main advantage is that it only needs water, air and electricity to be produced and there is no need for CO2. Ammonia is a very good candidate for transportation fuel (Giddey et al., 2017), with a global cost of 261 €/MWhNH3.

Methane production is composed of an electrolyser, a carbon capture and methanation process. As previously, the electrolyser still remains the most expensive process in the formation of CH4. Indeed, the economic contribution of the capture and the storage of CO2 is small relative to the global cost.

The storage and the transport of CH4 are not problematic, with a reduced cost. The global cost of CH4 is estimated at 262 €/MWhCH4, with a transport by pipeline. The CH4 production can be directly connected to the already well-established natural gas network. The entire industrial combustion processes are also suitable for this fuel. The use of CH4 will not require additional costs.

The best scenario is thus to produce H2 close to the grid to react with CO2 (produced locally or imported due to its low costs of storage and transport) for the formation of CH4. Then, CH4 could be connected to the natural gas network or stored in a tank. This fuel could be used for transportation or stationary applications.

The production of methanol is similar to CH4 one, with the same processes. Again, the electrolyser is the most expensive part of the production and should decrease in the future.

According to this work and the initial hypotheses, methanol is the cheapest fuel (219 €/MWhCH3OH), taking into account the costs of production, storage and transport. The main advantage of CH3OH is its liquid phase which is stable at atmospheric pressure and ambient temperature. Its storage cost is therefore negligible. As its storage is straightforward, the methanol can be stored for long term, without losses, and it can be used as a pure fuel in engines and other combustion processes.

The capture of CO2 is cheaper when the concentrations are higher than in the air (400 ppm). Due to its low cost of storage and transportation, the CO2 could be readily imported. An H2 buffer is sufficient for use in the plant and to optimize the production of CH4 or/and CH3OH.

A last molecule involved in such a process is oxygen. Indeed, thanks to the water electrolysis or the ASU process, the O2 is produced with a high level of purity (99.2%). This molecule is not taken into account in this study but it should be included in the full scenario to optimize the global cost of these fuels.

In a future work, in order to contribute to the optimization of the energy system, the production, transport, importation, storage and restitution of these electrofuels will be quantified taking into account a deterministic optimization. Instead of traditional optimization, the work will consist to include uncertainty quantification (aleatoric and epistemic) to the energy costs and economic costs, to perform robust optimization.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

VD performed all the calculations for the energy and economic costs of the chemical storage. MP has contributed to the inputs to run the calculations. FC and HJ advised this work.

The authors would like to thank Engie Electrabel for the funding.

The authors declare that this study received funding from Engie Electrabel. The funder was not involved in the study design, collection, analysis, interpretation of data, the writing of this article or the decision to submit it for publication.

The authors would like to thank Dr. Selma Brynolf (Chalmers University of Technology) for sending the data from her study (Brynolf et al., 2018).

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmech.2020.00021/full#supplementary-material

Abdul, F., Aziz, M. A., Saidur, R., Wan, W. A., Bakar, A., Hainin, M. R., et al. (2017). Pollution to solution: capture and sequestration of carbon dioxide (CO2) and its utilization as a renewable energy source for a sustainable future. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 71, 112–126. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.01.011

Altfeld, K., and Pinchbeck, D. (2013). Admissible Hydrogen Concentrations in Natural Gas Systems. Reprint Gas for energy 03/2013. DIV Deutscher Industrieverlag GmbH. Available online at: www.gas-for-energy.com

Aneke, M., and Wang, M. (2016). Energy storage technologies and real life applications–a state of the art review. Appl. Energy 179, 350–377. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.06.097

Aslam, R., Mu, K., Mu, M., Koch, M., Wasserscheid, P., and Arlt, W. (2016). Measurement of hydrogen solubility in potential liquid organic hydrogen carriers. J. Chem. Eng. Data 61, 643–649. doi: 10.1021/acs.jced.5b00789

Atsonios, K., Panopoulos, K. D., and Kakaras, E. (2016). Investigation of technical and economic aspects for methanol production through CO2 hydrogenation. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 41, 2202–2214. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.12.074

Azapagic, A., and Cue, R. M. (2015). Carbon capture, storage and utilisation technologies: a critical analysis and comparison of their life cycle environmental impacts. J. CO2 Utiliz. 9, 82–102. doi: 10.1016/j.jcou.2014.12.001

Bailera, M., Lisbona, P., Romeo, L. M., and Espatolero, S. (2016). Power to Gas-biomass oxycombustion hybrid system: energy integration and potential applications. Appl. Energy 167, 221–229. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.10.014

Balcombe, P., Speirs, J., Johnson, E., Martin, J., Brandon, N., and Hawkes, A. (2018). The carbon credentials of hydrogen gas networks and supply chains. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 91, 1077–1088. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.04.089

Bañares-Alcántara, R., Dericks, G. III, Fiaschetti, M., Grunewald, P., Lopez, J. M., Tsang, E., Yang, A., et al. (2014). Analysis of Islanded Ammonia-Based Energy Storage Systems. Technical report, University of Oxford.

Banaszkiewicz, T., Chorowski, M., and Gizicki, W. (2014). Comparative analysis of cryogenic and PTSA technologies for systems of oxygen production. AIP Conf. Proc. 1573, 1373–1378. doi: 10.1063/1.4860866

Bartels, J. R. (2008). A feasibility study of implementing an Ammonia Economy (PhD thesis), Iowa State University.

Brynolf, S., Taljegard, M., Grahn, M., and Hansson, J. (2018). Electrofuels for the transport sector: a review of production costs. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 1887–1905. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.05.288

Buttler, A., and Spliethoff, H. (2018). Current status of water electrolysis for energy storage, grid balancing and sector coupling via power-to-gas and power-to-liquids: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 2440–2454. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.09.003

Chen, H., Cong, T. N., Yang, W., Tan, C., Li, Y., and Ding, Y. (2009). Progress in electrical energy storage system: a critical review. Prog. Nat. Sci. 19, 291–312. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2008.07.014

Connolly, D., Lund, H., and Mathiesen, B. V. (2016). Smart Energy Europe: The technical and economic impact of one potential 100% renewable energy scenario for the European Union. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 60, 1634–1653. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.02.025

Connolly, D., Mathiesen, B. V., and Ridjan, I. (2014). A comparison between renewable transport fuels that can supplement or replace biofuels in a 100% renewable energy system. Energy 73, 110–125. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2014.05.104

Connolly, D., Mathiesen, B. V., and Ridjan, I. (2015). Corrigendum to “'A comparison between renewable transport fuels that can supplement or replace biofuels in a 100% renewable energy system”. Energy 83, 807–808. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2015.03.008

Darde, A., Prabhakar, R., Tranier, J.-P., and Perrin, N. (2009). Air separation and flue gas compression and purification units for oxy-coal combustion systems. Energy Proc. 1, 527–534. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2009.01.070

Das, C. K., Bass, O., Kothapalli, G., Mahmoud, T. S., and Habibi, D. (2018). Overview of energy storage systems in distribution networks: placement, sizing, operation, and power quality. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 91, 1205–1230. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2018.03.068

Elishav, O., Lewin, D. R., Shter, G. E., and Grader, G. S. (2017). The nitrogen economy: economic feasibility analysis of nitrogen-based fuels as energy carriers. Appl. Energy 185, 183–188. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.10.088

Environment and Energie (2014). Etude portant sur l'hydrogéne et la méthanation comme procédé de valorisation de l'électricité excédentaire. Technical report, GRTGaz.

Environment, G. (2016). Potentials and Perspectives for the Future Supply of Renewable Aviation Fuel. Technical Report September, Umwelt Bundesamt.

Er-rbib, H., and Bouallou, C. (2014). Modeling and simulation of CO methanation process for renewable electricity storage. Energy 75, 81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2014.05.115

Ferreira, H. L., Garde, R., Fulli, G., Kling, W., and Lopes, J. P. (2013). Characterisation of electrical energy storage technologies. Energy 53, 288–298. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2013.02.037

Fuhrmann, J., Hülsebrock, M., and Krewer, U. (2013). “Energy storage based on electrochemical conversion of ammonia,” in Transition to Renewable Energy Systems, eds D. Stolten and V. Scherer, 1–15. doi: 10.1002/9783527673872.ch33

Gallo, A. B., Simões-Moreira, J. R., Costa, H. K. M., Santos, M. M., and dos Santos, E. (2016). Energy storage in the energy transition context: a technology review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 65, 800–822. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2016.07.028

Ghaib, K., and Ben-Fares, F. Z. (2018). Power-to-methane: a state-of-the-art review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 81, 433–446. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.08.004

Gibbins, J., and Chalmers, H. (2008). Carbon capture and storage. Energy Policy 36, 4317–4322. doi: 10.1016/j.enpol.2008.09.058

Giddey, S., Badwal, S. P. S., Munnings, C., and Dolan, M. (2017). Ammonia as a renewable energy transportation media. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 5, 10231–10239. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.7b02219

Götz, M., Lefebvre, J., Mörs, F., McDaniel Koch, A., Graf, F., Bajohr, S., et al. (2016). Renewable power-to-gas: a technological and economic review. Renew. Energy 85, 1371–1390. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2015.07.066

Hadjipaschalis, I., Poullikkas, A., and Efthimiou, V. (2009). Overview of current and future energy storage technologies for electric power applications. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 13, 1513–1522. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2008.09.028

Hashimoto, K., Kumagai, N., Izumiya, K., Takano, H., Shinomiya, H., Sasaki, Y., et al. (2016). The use of renewable energy in the form of methane via electrolytic hydrogen generation using carbon dioxide as the feedstock. Appl. Surf. Sci. 388, 608–615. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2016.02.130

Hedegaard, K., and Meibom, P. (2012). Wind power impacts and electricity storage e a time scale perspective. Renew. Energy 37, 318–324. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2011.06.034

Ibrahim, H., Ilinca, A., and Perron, J. (2008). Energy storage systems–characteristics and comparisons. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 12, 1221–1250. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2007.01.023

Institute for Sustainable Process Technology (2016). Power to Ammonia. Technical report, Consortium: Nuon, Stedin, OCI Nitrogen, CE Delft, Proton Ventures, TU Delft, TU Twente, AkzoNobel, ECN.

Jentsch, M., Trost, T., and Sterner, M. (2014). Optimal use of power-to-gas energy storage systems in an 85% renewable energy scenario. Energy Proc. 46, 254–261. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2014.01.180

Jülch, V. (2016). Comparison of electricity storage options using levelized cost of storage (LCOS) method. Appl. Energy 183, 1594–1606. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2016.08.165

Kanniche, M., Gros-Bonnivard, R., Jaud, P., Valle-Marcos, J., Amann, J. M., and Bouallou, C. (2010). Pre-combustion, post-combustion and oxy-combustion in thermal power plant for CO2 capture. Appl. Thermal Eng. 30, 53–62. doi: 10.1016/j.applthermaleng.2009.05.005

Kauw, M., Benders, R. M. J., and Visser, C. (2015). Green methanol from hydrogen and carbon dioxide using geothermal energy and/or hydropower in Iceland or excess renewable electricity in Germany. Energy 90, 208–217. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2015.06.002

Koohi-Kamali, S., Tyagi, V. V., Rahim, N. A., Panwar, N. L., and Mokhlis, H. (2013). Emergence of energy storage technologies as the solution for reliable operation of smart power systems: a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 25, 135–165. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2013.03.056

Kotter, E., Schneider, L., Sehnke, F., Ohnmeiss, K., and Schroer, R. (2016). The future electric power system: impact of power-to-gas by interacting with other renewable energy components. J. Energy Storage 5, 113–119. doi: 10.1016/j.est.2015.11.012

Kousksou, T., Bruel, P., Jamil, A., Rhafiki, T. E., and Zeraouli, Y. (2014). Energy storage: applications and challenges. Solar Energy Mater. Solar Cells 120, 59–80. doi: 10.1016/j.solmat.2013.08.015

Kyriakopoulos, G. L., and Arabatzis, G. (2016). Electrical energy storage systems in electricity generation: energy policies, innovative technologies, and regulatory regimes. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 56, 1044–1067. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.12.046

Laborelec (2016). Levelised Costs of Electricity for Full CCS Chain for Coal Fired Power Plant and CCGTS. Energy Report.

Lan, R., Irvine, J. T. S., and Tao, S. (2012). Ammonia and related chemicals as potential indirect hydrogen storage materials. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 37, 1482–1494. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2011.10.004

Lehner, M., Tichler, R., and Koppe, M. (2014). Power-to-Gas: Technology and Business Models. Edition Springer. doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-03995-4

Limpens, G., and Jeanmart, H. (2018). Electricity storage needs for the energy transition: an eroi based analysis illustrated by the case of belgium. Energy 152, 960–973. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2018.03.180

Lund, P. D., Lindgren, J., Mikkola, J., and Salpakari, J. (2015). Review of energy system flexibility measures to enable high levels of variable renewable electricity. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 45, 785–807. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2015.01.057

Luo, X., Wang, J., Dooner, M., and Clarke, J. (2015). Overview of current development in electrical energy storage technologies and the application potential in power system operation Q. Appl. Energy 137, 511–536. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2014.09.081

Mathiesen, B. V., Lund, H., Connolly, D., Wenzel, H., Østergaard, P. A., Möller, B., et al. (2015). Smart energy systems for coherent 100% renewable energy and transport solutions. Appl. Energy 145, 139–154. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2015.01.075

Matzen, M., Alhajji, M., and Demirel, Y. (2015). Technoeconomics and sustainability of renewable methanol and ammonia productions using wind power-based hydrogen. Adv. Chem. Eng. 5, 1–12. doi: 10.4172/2090-4568.1000128

Mehrpooya, M., Kalhorzadeh, M., and Chahartaghi, M. (2016). Investigation of novel integrated air separation processes, cold energy recovery of liquefied natural gas and carbon dioxide power cycle. J. Clean. Prod. 113, 411–425. doi: 10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.12.058

Mesfun, S., Sanchez, D. L., Leduc, S., Wetterlund, E., Lundgren, J., Biberacher, M., et al. (2017). Power-to-gas and power-to-liquid for managing renewable electricity intermittency in the Alpine region. Renew. Energy 107, 361–372. doi: 10.1016/j.renene.2017.02.020

Olson, N., and Holbrook, J. (2007). “NH3 - The other hydrogen,” in Paper presented at the National Hydrogen Association Annual Conference.

Pires, J. C. M., Martins, F. G., Alvim-Ferraz, M. C. M., and Simoes, M. (2011). Recent developments on carbon capture and storage: an overview. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 89, 1446–1460. doi: 10.1016/j.cherd.2011.01.028

Qadrdan, M., Abeysekera, M., Chaudry, M., Wu, J., and Jenkins, N. (2015). Role of power-to-gas in an integrated gas and electricity system in Great Britain. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 40, 5763–5775. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.03.004

Ranjan, M., and Herzog, H. J. (2011). Feasibility of air capture. Energy Proc. 4, 2869–2876. doi: 10.1016/j.egypro.2011.02.193

Reuss, M., Grube, T., Robinius, M., Preuster, P., Wasserscheid, P., and Stolten, D. (2017). Seasonal storage and alternative carriers: a flexible hydrogen supply chain model. Appl. Energy 200, 290–302. doi: 10.1016/j.apenergy.2017.05.050

Rivarolo, M., Marmi, S., Riveros-Godoy, G., and Magistri, L. (2014). Development and assessment of a distribution network of hydro-methane, methanol, oxygen and carbon dioxide in paraguay. Energy Convers. Manag. 77, 680–689. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2013.09.062

Schiebahn, S., Grube, T., Robinius, M., Tietze, V., Kumar, B., and Stolten, D. (2015). Power to gas: technological overview, systems analysis and economic assessment for a case study in Germany. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 40, 4285–4294. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.01.123

Simonis, B., and Newborough, M. (2017). Sizing and operating power-to-gas systems to absorb excess renewable electricity. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 42, 21635–21647. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2017.07.121

Smith, A., and Klosek, J. (2001). A review of air separation technologies and their integration with energy conversion processes. Fuel Process. Technol. 70, 115–134. doi: 10.1016/S0378-3820(01)00131-X

Song, C., Liu, Q., Ji, N., Deng, S., Zhao, J., Li, Y., et al. (2018). Alternative pathways for efficient CO2 capture by hybrid processes–a review. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 82, 215–231. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2017.09.040

Stock, D., and Bauder, R. (1990). The New Audi 5-Cylinder Turbo Diesel Engine: The First Passenger Car Diesel Engine with Second Generation Direct Injection. SAE Technical Paper 900648. doi: 10.4271/900648

Tractebel and Hinicio (2017). Study on Early Business Cases for H2 in Energy Storage and More Broadly Power to H2 Applications. Technical report, Fuel cells and Hydrogen Joint Undertaking.

Tremel, A., Wasserscheid, P., Baldauf, M., and Hammer, T. (2015). Techno-economic analysis for the synthesis of liquid and gaseous fuels based on hydrogen production via electrolysis. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 40, 11457–11464. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.01.097

Trop, P., and Goricanec, D. (2016). Comparisons between energy carriers' productions for exploiting renewable energy sources. Energy 108, 155–161. doi: 10.1016/j.energy.2015.07.033

Vandewalle, J., Bruninx, K., and D'Haeseleer, W. (2015). Effects of large-scale power to gas conversion on the power, gas and carbon sectors and their interactions. Energy Convers. Manag. 94, 28–39. doi: 10.1016/j.enconman.2015.01.038

Walker, S. B., Mukherjee, U., Fowler, M., and Elkamel, A. (2015). Benchmarking and selection of power-to-gas utilizing electrolytic hydrogen as an energy storage alternative. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 41, 7717–7731. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2015.09.008

Wang, H., Zhou, X., and Ouyang, M. (2016). Efficiency analysis of novel liquid organic hydrogen carrier technology and comparison with high pressure storage pathway. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 41, 18062–18071. doi: 10.1016/j.ijhydene.2016.08.003

Zakeri, B., and Syri, S. (2015). Electrical energy storage systems: a comparative life cycle cost analysis. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 42, 569–596. doi: 10.1016/j.rser.2014.10.011

Keywords: chemical storage, hydrogen, methane, methanol, ammonia, carbon dioxide, power to fuel

Citation: Dias V, Pochet M, Contino F and Jeanmart H (2020) Energy and Economic Costs of Chemical Storage. Front. Mech. Eng. 6:21. doi: 10.3389/fmech.2020.00021

Received: 09 January 2020; Accepted: 08 April 2020;

Published: 29 May 2020.

Edited by:

Evangelos G. Giakoumis, National Technical University of Athens, GreeceReviewed by:

Milana Gutesa Bozo, Termoinzinjering d.o.o, SerbiaCopyright © 2020 Dias, Pochet, Contino and Jeanmart. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Véronique Dias, dmVyb25pcXVlLmRpYXNAdWNsb3V2YWluLmJl

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.