- 1Ningbo Cigarette Factory, China Tobacco Zhejiang Industrial Co., Ltd., Ningbo, China

- 2Faculty of Mechanical Engineering and Mechanics, Ningbo University, Ningbo, China

- 3Center for Mechanics Plus Under Extreme Environments, Ningbo University, Ningbo, China

- 4Technology Center, China Tobacco Zhejiang Industrial Co., Ltd., Hangzhou, China

- 5Faculty of Chemical Engineering and Biological Engineering, Zhejiang University, Hangzhou, China

Wettability has widespread applications in everyday life such as waterproof clothing, moisture-proof materials, and self-cleaning surfaces. It is also a common phenomenon observed in plants like the lotus, where superhydrophobicity is primarily influenced by chemical composition and microstructure, with the latter playing the most critical role. In this paper, we explore how microstructure affects the wettability of tobacco leaves and examine the relationship between microstructure and contact angle. We select three different Roast tobacco leaves and use Neumann models and Owens-Wendt-Rabel-Kaelble (OWRK) models to calculate the surface energy, and the surface energy is between 28 and 31 mN/m and the Young’s contact angle is around 90°. Based on the Cassie–Baxter model, we develop theoretical models of venation and foliage for predicting contact angles. The results show that the surface of the tobacco leaves can transition from hydrophilic to hydrophobic by modifying the size of the surface microstructure. Also we develop a method that use SEM and ImageJ to predict contact angle on leaves by analyzing solid-liquid contact area. The results indicate that the discrepancy between the theoretical and experimental results is within 5%. These findings may provide a better understanding of the wettability in natural plants and may pave a new way of realizing surface fabrications with specific infiltrating properties in industries.

1 Introduction

Hydrophobic and superhydrophobic surfaces play a significant role in self-cleaning, antifouling, and waterproofing applications. Hydrophobic properties are crucial in various scenarios, including manufacturing and textile industries. For example, wettability can significantly impact the taste of tobacco leaves in cigarette production, making the understanding of wettability is important. Consequently, the hydrophobicity of materials has attracted great interest from many scholars in the past decades (Liu et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2020; Guo and Liu, 2006). Inspired by the hydrophobic wettability of certain plant leaves, researchers have delved into the study of material wettability and its potential applications (Author Anonymous et al., 2018; Guo et al., 2011). Several natural interfacial materials exhibit functional properties, such as the low adhesive, self-cleaning, superhydrophobic lotus leaf; the structurally colored, superhydrophobic red rose petal; the superhydrophobic peanut leaf; and the superhydrophobic taro leaf (Jang et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015; Ghosh et al., 2019).

To elucidate the mechanisms behind such superhydrophobic behavior, we can examine the lotus leaf as an exemplary case. The lotus leaf demonstrates superhydrophobic characteristics, allowing water droplets to effortlessly roll off its surface in a spherical shape. This phenomenon is attributed to a waxy layer and the microscopic structures on the surface of the lotus leaf, which impart roughness to an otherwise smooth surface (Avrămescu et al., 2018). The organic wax can effectively reduce the surface energy, and in combination with the micro-nanostructures, it alters the droplet’s contact line and area, disrupting its continuity on the substrate. This reduction in contact leads to the surface’s superhydrophobicity (Barthlott et al., 2010). Similarly, nanostructures on the surface decrease particle adhesion, enabling droplets to more effectively remove particulate matter during full infiltration.

Research into the superhydrophobicity of diverse plant species has revealed that the factors affecting contact angle and wetting behavior are predominantly governed by the arrangement of micro-array structures, chemical composition, and multilevel hierarchical structures, with the latter two exerting the most significant influence. In this article, we primarily focus on the influence of microstructure on wettability, a topic that has garnered considerable attention from researchers. Investigations into the wettability and anisotropic flow properties of rice leaf surfaces have led to the analysis of their microscopic morphology and the implementation of rapid prototyping simulations. These studies have demonstrated that the asymmetric projections on rice leaves substantially affect the flow characteristics of droplets (Jang et al., 2020). Additionally, researchers have created bioinspired surfaces with hexagonal microcavities reminiscent of a honeycomb structure. Observations reveal that the contact angle of the taro leaf increases monotonically with the thickness of the cell walls, and these findings align well with the Cassie–Baxter model’s predictions for taro leaf contact angles (Kim et al., 2009; Kumar and Bhardwaj, 2020). This suggests that the configuration of micro-array structures can significantly influence the behavior of water droplets on these surfaces (Wang and Wallach, 2022; Feng et al., 2002).

Recognizing the role of microstructures in influencing wettability prompts the need for predictive methods and simulations under various conditions, such as those involving different plant leaves. For example, researchers conducted experiments on taro leaves, meticulously observing their microstructures and measuring the contact angles across varying cell wall thicknesses. By applying the Cassie–Baxter model, they successfully aligned the theoretical prediction curve with their experimental findings (Kumar and Bhardwaj, 2020). In a complementary approach, the team of Wang (Wang et al., 2022) employed the Surface Evolver software for numerical simulations and discovered that the degree of superhydrophobicity is largely dependent on the surface area exposed atop microstructural columns (Wang et al., 2022; Brown and Bhushan, 2016; Author Anonymous et al., 2018; Elzaabalawy and Meguid, 2020). Both approaches established equations based on Cassie–Baxter model, facilitating a comparison between the theoretical predictions and the experimental results. However, these existing studies often overlook the diverse microtopographies and structural variations across various parts of plant leaves, including the venation and foliage.

Numerous researchers have studied various leaf morphologies, which can be summarized as roughness, often linked to wettability. Hydrophilic materials become more hydrophilic with increasing roughness, while hydrophobic materials become more hydrophobic (Wang and Zhang, 2020; Yolcu, 2017). The determination of roughness is essential, with various techniques available, such as SEM and AFM, each having specific limitations. SEM and AFM typically require special sample preparation, such as coating the samples. Additionaly, AFM is constrained by a maximum scan height of 7–10 μm, which limits its effectiveness to very flat surfaces without prominent features, as this can result in considerable difficulty and time consumption. To address these limitations and enhance our analysis of contact angles on tobacco leaves, this study evaluates the use of a 3D optical surface profiler as a new method for measuring leaf surface roughness. This method is faster, taking only seconds to scan a measurement, does not require preparation time as SEM, is less cumbersome, and potentially more accurate than the fractal dimension analysis and other methods, providing a full depth field (Abbott and Zhu, 2019; Prajapati and Rowthu, 2022). Our study uniquely addresses this gap by integrating detailed two-dimensional modeling and simulation to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the wettability characteristics of tobacco leaves. We analyze the microscopic structures of the venation and foliage of tobacco leaves and establish a two-dimensional model of venation to prediction contact angle. Subsequently, we derive equations for these structures and develop a new method to calculate the contact angle of smooth part of foliage. We also determine the contact angles of tobacco leaves through experimental measurements, finding good agreement between the experimental results and theoretical predictions. Additionally, we simulate the contact angle of venation by using finite elements method, obtaining different contact angle with varying droplet infiltration depths.

The role of wettability in tobacco and cigarette manufacturing is pivotal, impacting multiple facets of production from process efficiency to product quality. This characteristic is fundamentally significant for processing performance, ensuring the chemical integrity of the tobacco, influencing combustion behavior, enhancing filler properties, and facilitating storage and transportation logistics. This work not only offers guidance for regulating wettability properties in tobacco leaf production, but also provides insights for the design and manufacture of novel smart hydrophobic surface materials.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 The imaging process of SEM

The microstructure of the leaves is observed using the Phenom ProX scanning electron microscope (SEM) manufactured by Phenom. Samples of three different roasted tobacco leaves, processed into cured leaves using the same curing method, measuring 2 mm

2.2 The measurement of contact angle

The primary apparatus used in this experiment is a contact angle measuring instrument (SDC-100S). The tobacco leaf sample is meticulously positioned at the center of the sample stage. An electric injection system, located directly above the stage, facilitates the release of droplets. Adjacent to this, an LED light source is installed. The stage is then elevated to allow droplets to impinge on the surface of the tobacco leaf. Once stabilized, the stage is lowered to capture the droplet’s morphology. The contact angle is subsequently obtained from the captured image of the droplet’s shape. The volume of the liquid used (water and diiodomethane) is 1 μL, the humidity of the test environment is 45%, and the drops are set to take pictures 15 s after deposition. The corresponding image size is 4,000 μm

2.3 The measurement of roughness

In order to obtain the roughness of Roast tobacco leaves, an optical profilometer with Vertical Scanning Interferometry (NT9100) manufactured by Veeco company is used. It provides fast and high-precision 3D surface topography measurement in the vertical scanning range of 0.1 nm–1 mm, suitable for micron measurement. The minimum measurable piece size is 50 μm

3 The microstructure of venation and foliage

3.1 The microstructure and contact angle of leaves

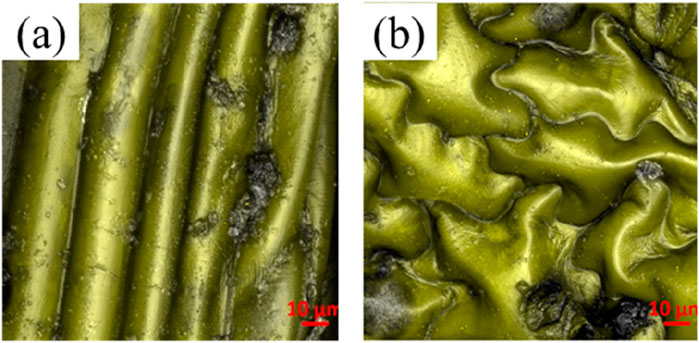

Upon utilizing scanning electron microscope (SEM), we discern two unique microstructures within tobacco leaves, subsequently classifying the leaf tissue into two primary components: the venation and the foliage. We choose three specimens of tobacco leaves, specifically Roast tobacco leaves 1, 2, and 3, to further investigate the interplay between these microstructures and their influence on the wettability and overall functionality of the leaf surfaces. The preliminary phase of our study entails the documentation of the surface microscopic morphology of tobacco leaves. In our investigation of the selected tobacco samples, we employ SEM to capture representative surface morphologies, which are depicted in Figure 1. The findings reveal the microscopic morphology of the venation in tobacco leaves, characterized by a predominantly regular groove-ridge pattern like Figure 1A. In contrast, Figure 1B illustrates the microscopic morphology of the foliage, which diverges from the venation by exhibiting an irregular, bulging topography.

Figure 1. SEM images of the surface micromorphology of tobacco leave at the ten-micron scale: (A) The venation; (B) The foliage.

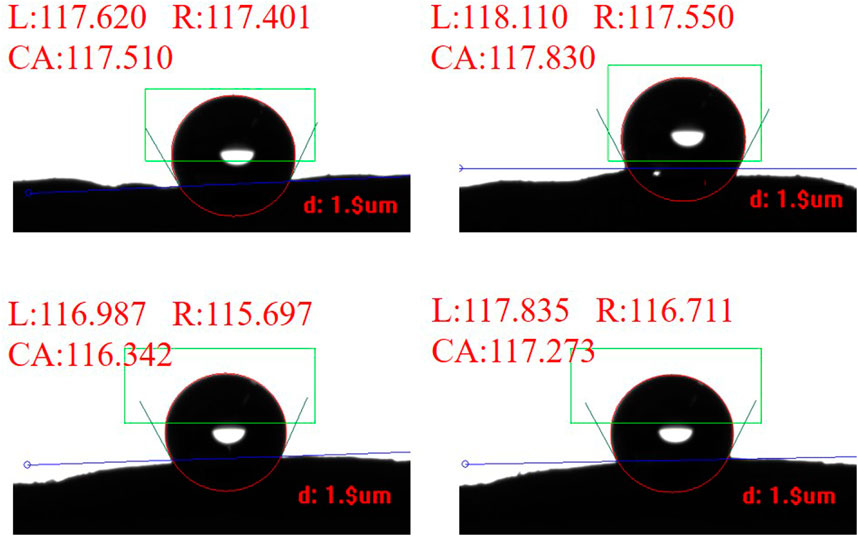

To investigate the wetting properties of the venation and foliage of tobacco leaves, we conduct experiments to measure the contact angle of water droplets on their respective surface morphologies. However, on these microstructured surfaces, the droplets exhibit varying degrees of anisotropy. Specifically, the shape and contact angle of water droplets perpendicular to the venation differ from those along the long axis of the veins. This phenomenon occurs because the water droplets spread along the long axis of the venation, resulting in a smaller contact angle in that direction (Calvimontes et al., 2012; Timoshenko et al., 2012; Wang et al., 2018). In our experiments, we primarily focused on the contact angle perpendicular to the venation direction. Figure 2 presents some results from our experiments, showing the measured contact angles perpendicular to the venation direction. We selected one Roast tobacco and measured the contact angles of different areas on the venation. The average contact angle is 117.2° ± 2.3°. This result demonstrates that the venation of tobacco leaves primarily exhibit hydrophobic properties. The results of the contact angles for the other venations are included in Supplementary Figure S1, as the measurement process is consistent across all samples.

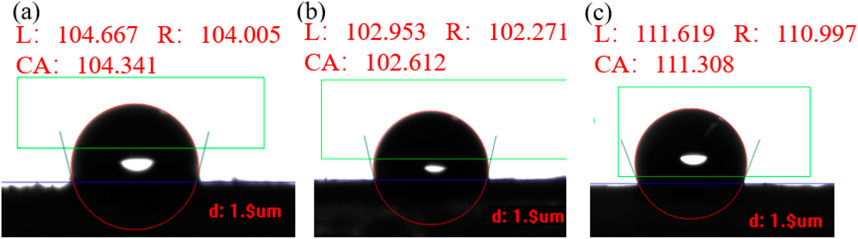

After measuring the contact angles on the venation, we similarly assess the contact angle on the foliage. Figure 3 exhibits one of experimental contact angles for Roast tobacco leaf 1, Roast tobacco leaf 2, and Roast tobacco leaf 3. Numerous experiments are conducted to obtained the average contact angles for the different tobaccos, which are found to be 103.578°, 99.290°, 108.113°, respectively. These results indicate that different tobacco leaves exhibit varying degrees of hydrophobicity. However, our experimental results demonstrate that the variation in contact angle across different areas of the same tobacco leaves is minimal, it can be saw in Supplementary Figures S2–S4. The experimental results indicate that the foliage also possesses a contact angle suggestive of hydrophobic properties, thereby confirming that the tobacco leaves exhibit hydrophobicity in our study.

Figure 3. The contact angle on foliage of three different roast tobacco: (A) Roast tobacco leave 1; (B) Roast tobacco leave 2; (C) Roast tobacco 3.

In order to establish the prediction model of tobacco leave contact angle, we also need to measure Young’s contact angle of plants. Therefore, in the following chapters, we will describe in detail how to measure and obtain an approximate value of Young’s contact angle of tobacco leaves.

3.2 Measurement of Young’s contact angle

The concept of the contact angle is first introduced by Thomas Young in 1805, which is expressed as follows (Lin et al., 2014):

where

To obtain Young’s contact angle, it is necessary to know the values of three interfacial tensions from Equation 1 (Zhu et al., 2007a; Zhu et al., 2007b). Using these surface tension values, we can calculate Young’s contact angle. To ensure the accuracy of Young’s contact angle calculation, we reviewed varous works conducted by numerous scholars to calculate the surface tension and ultimately arrive at a method that yields more satisfactory results (Chindam et al., 2015; Chindam et al., 2016; Zenkiewicz et al., 2006). We selected three different types of tobacco leaves for the experiment. The method used to measure these leaves is called Neumann method and the team applied this method to calculate the surface energy of paper and found it has minor error (Fan et al., 2022; Chindam et al., 2015; Chindam et al., 2016; Zenkiewicz et al., 2006). The relationship between interfacial tensions and Young’s contact angle is as follows:

Where

where

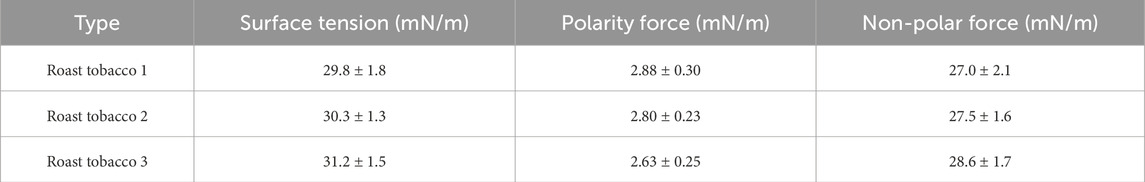

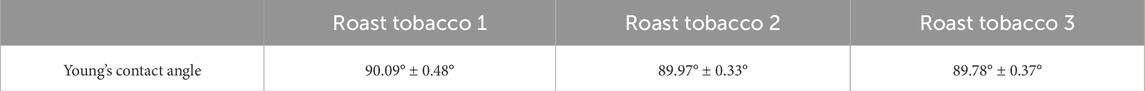

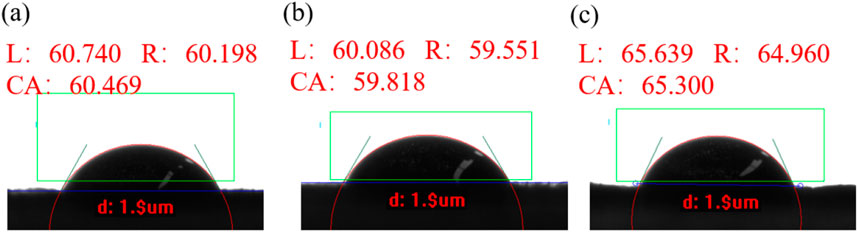

In this experiment, two physical quantities are required: the interfacial tension at solid-gas interface, the interfacial tension at liquid-gas interface. The measurement procedure is as follows: First, diiodomethane is used to measure the contact angles of the three different smooth tobacco leaves as shown in Figure 4, three tobacco leaves’ contact angles are approximately 60°. Multiple measurements are taken for each type of tobacco leaf to calculate the average values, which are found to be 62.801°, 61.923°, and 60.000°, respectively. The contact angles show small differences among different tobacco leaves. Additionally, when measuring various areas of the same tobacco leaf, only minor differences in the contact angles are observed, as shown in Supplementary Figures S5–S7. Then, the average contact angles of diiodomethane are substituted into Equation 2 to obtain the surface tension of solid

Figure 4. Diiodomethane’s contact angle on tobacco leaf: (A) Roast tobacco 1; (B) Roast tobacco 2; (C) Roast tobacco 3.

Finally, by substituting the polar and nonpolar forces of water into Equation 3, we obtain an approximate Young’s contact angle between water and an ideal solid, and we consider both venation and foliage have the same Young’s contact angle, the results are presented in Table 2. The results indicate that the Young’s contact angles for the three types of tobacco leaves are closely aligned, approximately 90°. However, the experimental contact angle significantly deviates from the Young’s contact angle, primarily due to variations in chemical composition and surface microstructure.

4 Theoricital model for predicting contact angle of leaves

There are three models for wettability: the ideal surface model of Young’s equation, (the rough surface Wenzel model) quoted (Wenzel, 1949), and the Cassie–Baxter model. The latter two are a refinement of the former. Young’s equation is based on an ideal surface and is not realistic for most practical applications, whereas the Wenzel and Cassie–Baxter models account for surface roughness. The Wenzel model assumes no air gaps under the microstructure, while the Cassie–Baxter model, which is more widely used, assumes the presence of air gaps under the microstructure. In this section, we will systematically present two models derived from the Cassie–Baxter framework for predicting the contact angles on tobacco leaves. For the sake of brevity, detailed descriptions of the three models are provided in the Supplementary Material. The Cassie–Baxter model can be expressed as (Cassie, 1948; Genzer and Efimenko, 2006):

Where

4.1 Theoretical model of venation

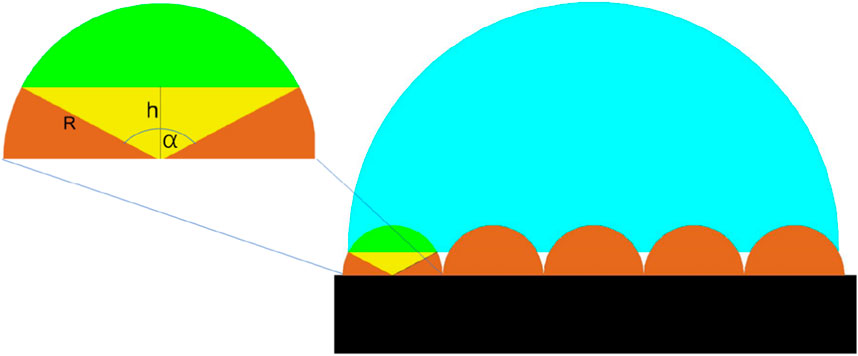

Figure 1 depicts a regular groove-ridge pattern on the surface of venation. As a result, we propose a two-dimensional model composed of a flat base, semi-cylindrical venation, and wetting droplets, as demonstrated in Figure 5. In this theoretical model, the radius of the semi-cylindrical venation is denoted by R, and h represents the height difference between the radius of the tobacco venation and the depth of droplet infiltration into the venation. The angle

Figure 5. The two-dimensional model represents the venation pattern of a tobacco leaf. In this model, the black region corresponds to the base of the tobacco leaf. The brown semi-cylindrical structures depict the venations, while the blue portions indicate the droplets. The green area signifies the regions where droplets have the potential to infiltrate.

For a single venation, the solid and liquid contact area is expressed as

Within the framework of the Cassie–Baxter model, which considers the two previously mentioned physical properties, the ratio of solid-liquid contact is acknowledged as being of utmost importance. This critical physical parameter reflects the proportion of the liquid’s contact area with the leaf venation compared to the venation’s projected area (AuthorAnonymous et al., 2018; Jiang et al., 2011; Hsieh et al., 2008; Milne and Amirfazli, 2012). This ratio is critical for understanding the wetting behavior and adhesion characteristics of a droplet on the leaf surface (Ye and Mizutani, 2023; Xue et al., 2012). Combined the Equation 5 and Equation 6, the fraction f can be calculated as follows:

Based on the Cassie–Baxter model, by substituting Equation 7 into Equation 4, we derive an explicit equation that can be used to predict the contact angle on venation of tobacco leave

where

4.2 Theoretical model of foliage

Contrary to the venation of leaves, the foliage presents an irregular shape, complicating the development of either two-dimensional or three-dimensional models. To overcome this obstacle, we employ an innovative approach to calculate the contact angle of foliage by introducing the ratio of the actual surface area to its projected area.

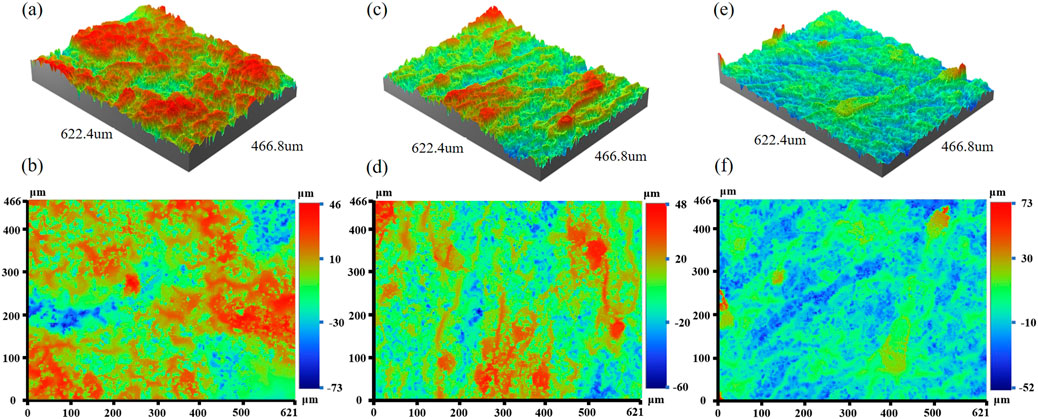

We use a profilometer and select a slice of tobacco to calculate the surface area and its projected area. Figure 6 shows the roughness of three different types of tobacco under a profiler. The projected area of the samples is 0.289 mm2. Areas of higher elevation are marked in red, transitioning to green and blue with decreasing height, indicating lower elevations. The total surface area is calculated as the sum of these surface folds. Table 3 presents the surface area, projected area, and the ratio of surface area to projected area for three different types of tobacco. It is evident that the surface of Roast tobacco 3 exhibits greater smoothness compared to Roast tobacco 1.

Figure 6. The three-dimensional and two-dimensional image under profiler. (A, B) Roast tobacco 1, (C, D) Roast tobacco 2, (E, F) Roast tobacco 3.

Table 3. The surface area, projected area and the ratio of them for three different types of tobacco.

The solid-liquid contact area is denoted as

Since the contact angle depends on the solid-liquid contact area, we can link Equations 4, 9 with percentage of contact area

This expression captures the interplay between the contact angle and the specific geometry of the solid-liquid interface on the foliage surface. It can be seen that the contact angle expression for foliage can be characterized by a single unknown parameter

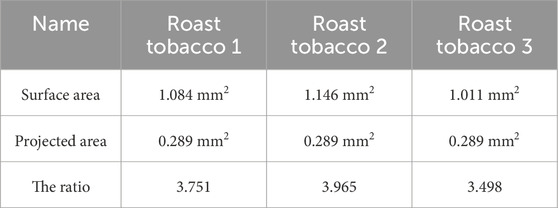

4.3 A method to calculate contact angle of foliage

During the process of SEM imaging, we discover an interesting phenomenon: for some foliage surfaces that are relatively smooth and flat, the solid-liquid ratio in the Cassie–Baxter model can be directly obtained by binarizing the partially observed foliage images. This occurs because, when a liquid contacts a solid surface with a micro-nano structure, the liquid does not completely fill all the grooves and holes but instead forms a continuous layer of air that supports the liquid along with the solid surface, allowing water droplets to rest on the solid surface (Bormashenko, 2010; Shi et al., 2012). Based on this mechanism, the air in the surface voids of the flat tobacco leaf supports the water droplets, leading to an observable solid-liquid contact area. This phenomenon provides a new method to calculate the contact angle.

We employ a method that involves characterizing the micromorphology of the foliage using an electron microscope and analyzing it with ImageJ software. The characterized area is divided into regions representing the solid-liquid contact area and the non-contact area. The software then computes the ratio of these areas, which is subsequently utilized in the Cassie–Baxter model to determine the corresponding contact angle. In this study, we examine various types of tobacco leaves and different foliage blocks. Figure 7 demonstrates the alterations resulting rom image binarization and segmentation. We select a part of area of tobacco leaves under SEM as shown in Figure 7A. Specifically, in Figure 7B, the solid-liquid contact area is represented by the white regions, while the non-contact areas are depicted in black. This visual representation aids in understanding of the distribution and extent of contact between the solid and liquid phases on the surface being analyzed. Each cell is individually separated, labeled, and its area calculated. Upon completing these calculations for all cells, the sum of the areas corresponding to the white regions, which represent the solid-liquid contact area, can be determined. The ratio of this sum to the selected area provides the percentage of the solid-liquid contact area.

Figure 7. Binarized SEM images and segmented cells to calculate area (269 μm

5 Results and discussion

In our study, we primarily focus on the wettability of the venation and foliage of tobacco leaves. Firstly, we compare the theoretically predicted contact angle with the experimentally measured one. Subsequently, we use the model to analyze the factors influencing the contact angle and verify our model using the finite element method.

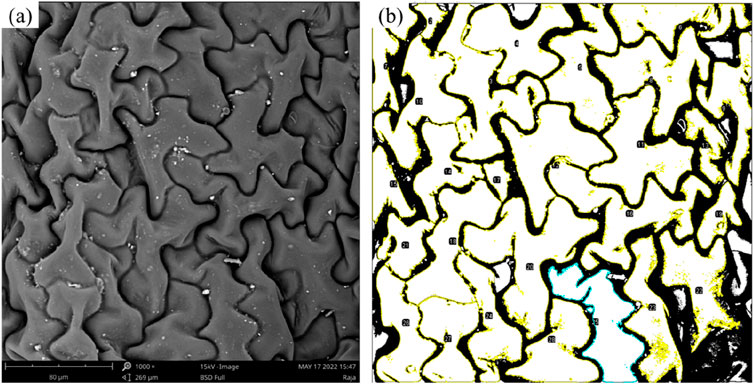

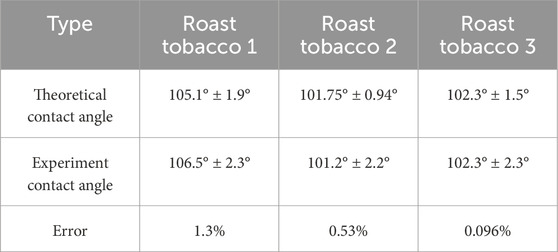

5.1 The results of foliage

Table 4 presents the contact angles calculated through the method in Section 4.3, the solid-liquid area of the contact and non-contact are identified by ImageJ, and the percentage of the two are substituted into Equation 4, theoretically predicted contact angles for three types of tobacco leaves. For each identical Roast tobacco leaf, we take 10 different foliage parts to obtain the contact area of solid-liquid. As shown in this Table, the average contact angle for the different types of tobacco are 105.130°, 101.750°, and 102.250°, respectively. The observed variations in error are minor across different tobacco types, resulting in an overall negligible deviation. For roasted tobaccos, the average theoretical contact angle closely approximates the experimental contact angle, with an error margin of approximately 2%. This indicates that the theoretical predictions for contact angles closely align with the experimental data.

Table 4. The theoretical contact angle and the experiment contact angle with the error between them.

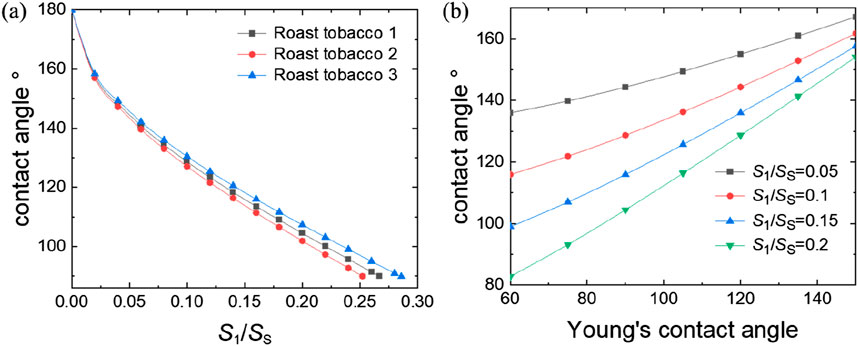

From the Equation 10, it can be seen that the value of the contact angle can be adjusted by modifying the ratio of solid-liquid contact area to surface area

Figure 8. The relationship between contact angle with parameters from Equation 10: (A) the ratio of solid-liquid contact surface area to the projected area

5.2 The results of venation

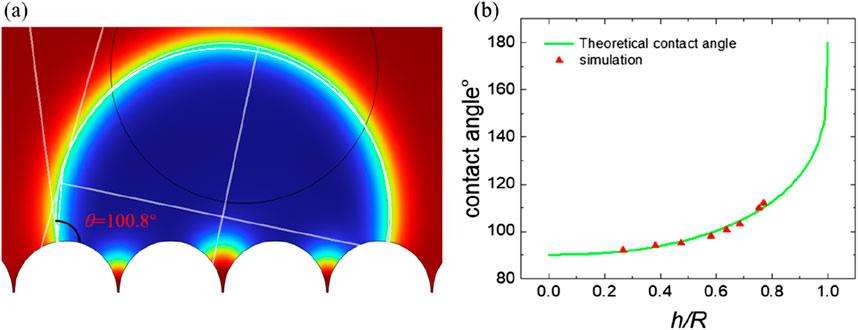

Some researchers have conducted extensive simulations to replicate the contact angle of droplets on various microstructures. For instance, they employed Evolver to simulate the infiltration process on Nepenthesand discovered that the contact angle ranged from 155° to 155.400° under an infiltration ratio of 0.700–0.800, providing theoretical insights into the superhydrophobic mechanism of Nepenthes (Wang et al., 2022). To validate the contact angle prediction model for the venation, we also simulate the contact angle of tobacco leaves by using COMSOL Multiphysics. This approach allows us to test and refine our understanding of the hydrophobic properties exhibited by intricate structures found in nature.

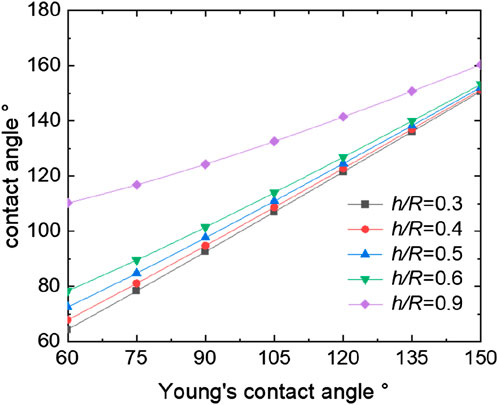

We establish a two-dimensional venation model in COMSOL using the two-phase flow module in fluid flow, employing phase filed method. As calculated in previous sections, the intrinsic contact angles of various tobacco leaves are approximately 90°. Thus, within our simulation, we set the intrinsic contact angle of the wetting wall to 90° to accurately represent these tobacco leaves. A corresponding micro-morphology is constructed on this basis. We apply phase field and laminar flow boundary conditions, designating outlets, inlets, and open boundaries accordingly, while ensuring of mass conservation. The grid type is a free triangular grid, and the grid size is very fine, with the software automatically dividing it. Upon stabilization of the droplet, we measure the contact angles and the ratio of h/R. The results of the venation’ theoretical model is shown in Figure 9, which illustrates the simulated contact angle of a water droplet in comparison to the predictions of the model for the Cassie–Baxter state. For the venation of tobacco leaves, the contact angle also increases with the increasing of the ratio h/R. The contact angle of the droplet is time-dependent during the dynamic simulation, and the contact angle decreases until it remains constant with the passage of time. Based on this behavior, we extend the simulation time until the droplet at a stable state (Dezellus et al., 2002; Wang et al., 2022). Both the simulation and the model exhibit reasonably good agreement, with the model accurately capturing the trend observed in the simulation. This congruence between the simulation and the model further validates our understanding of the hydrophobic properties of the venation structure and its interaction with water droplets.

Figure 9. The simulation of contact angle for venation and relationship between theoretical and simulation: (A) the static contact angle; (B) relationship between contact angle and h/R.

From the Equation 8 of venation, it can be seen that the value of the contact angle can be regulated by changing the ratio of h/R and the Young’s contact angle. Figure 9 presents the trend of contact angle variations in accordance with the theoretical model. Figure 9 demonstrates that an increase in the h/R ratio leads to an enlargement of the contact angle. The ratio h/R quantifies the solid-liquid contact area, with a higher value indicating a decreased contact area between the solid and liquid phases. As this ratio approaches zero, the contact angle reaches its minimum, indicative of complete liquid infiltration into the solid surface, achieving the Wenzel state. Conversely, as the ratio h/R approaches 1, the contact angle reaches its maximum, indicating an almost non-existent contact between the liquid and the solid surface. This condition corresponds to the Cassie state, which is an ideal scenario for superhydrophobic surfaces. In this state, the liquid appears to hover above the surface rather than making direct contact. This relationship highlights the direct influence of geometric parameters on the wetting properties of surfaces, as predicted by our theoretical model. Figure 10 presents the trend of contact angle variations in accordance with the theoretical model of venation from Equation 8. From Figure 10, we find the same phenomenon with foliage that the larger of the Young’s contact angle, the larger the contact angle. Similarly, by modifying the microstructural morphology, plants displaying Young’s contact angles less than 90° can be transformed into hydrophobic plants with contact angles greater than 90°. This adjustment demonstrates the impact of surface structure on the hydrophobic properties of plant surfaces, highlighting the practical application of altering wetting characteristics through morphological changes.

The results indicate that both the foliage and venation of tobacco leaves exhibit hydrophobic properties. The variations in contact angles among different tobacco leaves are primarily attributed to the magnitude of the Young’s contact angle and the percentage of the liquid droplet’s wetted area. By manipulating the percentage of the wetted area on the venation and foliage parts and adjusting their respective proportions, one can achieve the desired wetting effects. This approach underscores the potential for targeted modifications of plant surface hydrophobicity through alterations of the surface micromorphology.

6 Conclusion

In summary, this study presents a comprehensive analysis of the wettability on tobacco leaves. Utilizing SEM, we examined the intricate microstructures of various tobacco leaves, observing a uniform semi-cylindrical pattern in the venation while noting the irregular patterns of the leaf’s foliage. For the venation patterns on tobacco leaves, we developed a theoretical model for prediction and computed the surface energy for various types of tobacco. We observed that the contact angles increase with the ratio h/R of the microstructures. Additionally, we developed a contact angle model for leaf foliage that considers its roughness and applied the Cassie–Baxter model to address droplet infiltration on the microscopic irregularities. The results agree very well with both the experimental results and the finite element simulations. Our findings indicate that both venation and foliage models substantially improve the accuracy of contact angle predictions. By establishing a theoretical prediction model of contact angle, we can roughly predict the wettability of leaf surfaces with similar microstructures. By altering different parameters in the theoretical formula, we can modify the wettability of the object’s surface. This highlights the microstructure’s pivotal role in influencing wettability characteristics and offers essential insights for evaluating the wettability of botanical surfaces as well as other materials.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Author contributions

JT: Methodology, Writing–original draft. BS: Methodology, Writing–original draft. YQ: Conceptualization, Writing–original draft. WZ: Data curation, Writing–original draft. RX: Formal Analysis, Writing–original draft. MW: Formal Analysis, Writing–original draft. KL: Conceptualization, Writing–review and editing. JQ: Investigation, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LQ24A020005).

Conflict of interest

Authors JT, RX, MW, JQ, and YQ were employed by China Tobacco Zhejiang Industrial Co., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmats.2024.1485713/full#supplementary-material

References

Abbott, J. R., and Zhu, H. (2019). 3D optical surface profiler for quantifying leaf surface roughness. Surf. Topogr. Metrology Prop. 7 (4), 045016. doi:10.1088/2051-672x/ab4cc6

Asai, B., Tan, H., and Siddique, A. U. (2022). Droplet impact on a micro-structured hydrophilic surface: maximum spreading, jetting, and partial rebound. Int. J. Multiph. Flow 157, 104235. doi:10.2139/ssrn.4154042

Avrămescu, R. E., Ghica, M. V., Dinu-Pîrvu, C., Prisada, R., and Popa, L. (2018). Superhydrophobic natural and artificial surfaces—a structural approach. Materials 11 (5), 866. doi:10.3390/ma11050866

Barthlott, W., Schimmel, T., Wiersch, S., Koch, K., Brede, M., Barczewski, M., et al. (2010). Superhydrophobic coatings: the salvinia paradox: superhydrophobic surfaces with hydrophilic pins for air retention under water (adv. Mater. 21/2010). Adv. Mater. 22 (21), 2325–2328. doi:10.1002/adma.200904411

Bormashenko, E. (2010). Wetting transitions on biomimetic surfaces. Philos. Trans. 368 (1929), 4695–4711. doi:10.1098/rsta.2010.0121

Brown, P. S., and Bhushan, B. (2016). Designing bioinspired superoleophobic surfaces. Apl. Mater. 4 (1). doi:10.1063/1.4935126

Cai, L., Jiang, G., Zheng, S., and Hu, Z. (2008). Observation of glandular hairs morphology on tobacco leaves by scanning electron microscopy. Chin. Agric. Sci. Bull. doi:10.11924/j.issn.1000-6850.20086049

Calvimontes, A., Mauermann, M., and Bellmann, C. (2012). Topographical anisotropy and wetting of ground stainless steel surfaces. Materials 5 (12), 2773–2787. doi:10.3390/ma5122773

Chindam, C., Lakhtakia, A., and Awadelkarim, O. O. (2015). Surface energy of parylene C. Mater. Lett. 153, 18–19. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2015.04.009

Chindam, C., Lakhtakia, A., and Awadelkarim, O. O. (2016). Reply to “comment on ‘surface energy of parylene C’”. Mater. Lett. 166, 325–326. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2015.12.127

Cui, Z., Binks, B. P., and Clint, J. H. (2004). Determination of surface tension and surface tension components of porous particle with sub-pores by thin-layer wicking technique. China Surfactant Dettrgent And Cosmet. 34 (4), 207–210. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1001-1803.2004.04.001

Decker, E. L., Frank, B., Suo, Y., and Garoff, S. (1999). Physics of contact angle measurement. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 156 (1-3), 177–189. doi:10.1016/s0927-7757(99)00069-2

Dezellus, O., Hodaj, F., and Eustathopoulos, N. (2002). Chemical reaction-limited spreading: the triple line velocity versus contact angle relation. Acta Mater. 50 (19), 4741–4753. doi:10.1016/S1359-6454(02)00309-9

Du, F., Lv, P., Li, H., Wang, J., and Shao, L. (2024). A theoretical model to determine solid surface tension through droplet on film configuration and experimental verification. J. Mech. Phys. Solids 183, 105504. doi:10.1016/j.jmps.2023.105504

E, J., Yu, J., Deng, Y., Zuo, W., Zhao, X., Han, D., et al. (2018). Wetting models and working mechanisms of typical surfaces existing in nature and their application on superhydrophobic surfaces: a review. Adv. Mater. Interfaces 5, 1701052. doi:10.1002/admi.201701052

Elzaabalawy, A., and Meguid, S. A. (2020). Effect of surface topology on the wettability of superhydrophobic surfaces. J. Dispersion Sci. Technol. 41 (3), 470–478. doi:10.1080/01932691.2019.1587299

Fan, H., Liao, Y., Li, F., Huang, S., Zhang, K., Zeng, D., et al. (2022). Exploration on the surface free energy testing method of paper literature. China Pulp & Pap. 41 (12), 95–101. doi:10.11980/j.issn.0254-508X.2022.12.014

Feng, L., Li, S., Li, Y., Li, H., Zhang, L., Zhai, J., et al. (2002). Super-hydrophobic surfaces: from natural to artificial. Adv. Mater. 14 (24), 1857–1860. doi:10.1002/chin.200307200

Genzer, J., and Efimenko, K. (2006). Recent developments in superhydrophobic surfaces and their relevance to marine fouling: a review. Biofouling 22 (5), 339–360. doi:10.1080/08927010600980223

Ghosh, U. U., Nair, S., Das, A., Mukherjee, R., and DasGupta, S. (2019). Replicating and resolving wetting and adhesion characteristics of a rose petal. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 561, 9–17. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2018.10.028

Guo, Z., and Liu, W. (2006). Progress in biomimicing of super-hydrophobic surface. Prog. Chem. 18 (06), 721. doi:10.3321/j.issn:1005-281X.2006.06.005

Guo, Z., Liu, W., and Su, B. (2011). Superhydrophobic surfaces: from natural to biomimetic to functional. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 353 (2), 335–355. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2010.08.047

Hsieh, C. T., Chen, W. Y., Wu, F. L., and Shen, Y. S. (2008). Fabrication and superhydrophobic behavior of fluorinated silica nanosphere arrays. J. Adhesion Sci. Technol. 22 (3-4), 265–275. doi:10.1163/156856108x295365

Jang, M. Y., Park, J. W., Baek, S. Y., and Kim, T. W. (2020). Anisotropic wetting characteristics of biomimetic rice leaf surface with asymmetric asperities. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 20 (7), 4331–4335. doi:10.1166/jnn.2020.17570

Jiang, Z., Geng, L., Huang, Y., Guan, S., Dong, W., and Ma, Z. (2011). The model of rough wetting for hydrophobic steel meshes that mimic Asparagus setaceus leaf. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 354 (2), 866–872. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2010.11.006

Kim, G. H., Jeon, H. J., and Yoon, H. (2009). Electric field-aided formation combined with a nanoimprinting technique for replicating a plant leaf. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 30 (12), 991–996. doi:10.1002/marc.200900076

Kim, J. H., Kavehpour, H. P., and Rothstein, J. P. (2015). Dynamic contact angle measurements on superhydrophobic surfaces. Phys. Fluids 27 (3). doi:10.1063/1.4915112

Kumar, M., and Bhardwaj, R. (2020). Wetting characteristics of Colocasia esculenta (Taro) leaf and a bioinspired surface thereof. Sci. Rep. 10 (1), 935. doi:10.1038/s41598-020-57410-2

Lim, J., Powell, N., Lee, H., and Michielsen, S. (2016). Integration of yarn compression in modeling structural geometry of liquid resistant–repellent fabric surfaces and its impact on liquid behavior. J. Mater. Sci. 51, 7199–7210. doi:10.1007/s10853-016-0001-x

Lin, J., Cai, X., Lu, P., Liao, L., Cai, X., Liu, X., et al. (2014). Progress in trisiloxane superspreader and its superspreading mechanism on the surface of plant leaves. Chem. Industry Eng. Progree 32 (12), 3342–3348. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1000-6613.2014.12.035

Liu, M., Wang, S., and Jiang, L. (2017). Nature-inspired superwettability systems. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2 (7), 17036–17117. doi:10.1038/natrevmats.2017.36

Liu, Y., Dong, H., Hu, J., Zhao, M., Liu, S., and Zeng, S. (2013). Surface free energies and their fractions of different tobacco leaves in Yunnan. J. Northwest A & F University-Natural Sci. Ed. 41 (7), 75–78. doi:10.13207/j.cnki.jnwafu.2013.07.017

Ma, J., Sun, Y., Gleichauf, K., Lou, J., and Li, Q. (2011). Nanostructure on taro leaves resists fouling by colloids and bacteria under submerged conditions. Langmuir 27 (16), 10035–10040. doi:10.1021/la2010024

Marmur, A. (1996). Equilibrium contact angles: theory and measurement. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 116 (1-2), 55–61. doi:10.1016/0927-7757(96)03585-6

Milne, A. J. B., and Amirfazli, A. (2012). The Cassie equation: how it is meant to be used. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 170 (1-2), 48–55. doi:10.1016/j.cis.2011.12.001

Pak, H., and Kim, J. H. (2023). Static and dynamic contact angle measurements using a custom-made contact angle goniometer. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 37 (8), 4117–4124. doi:10.1007/s12206-023-0728-7

Prajapati, D. G., and Rowthu, S. (2022). Unravelling the anisotropic wetting properties of banana leaves with water and human urine. Surfaces Interfaces 29, 101742. doi:10.1016/j.surfin.2022.101742

Shi, X., Lu, S., and Xu, W. (2012). Fabrication of cuzn5–zno–cuo micro–nano binary superhydrophobic surfaces of cassie–baxter and gecko model on zinc substrates. Mater. Chem. Phys. 134 (2-3), 657–663. doi:10.1016/j.matchemphys.2012.03.046

Shim, M. H., Kim, J., and Park, C. H. (2014). The effects of surface energy and roughness on the hydrophobicity of woven fabrics. Text. Res. J. 84 (12), 1268–1278. doi:10.1177/0040517513495945

Strobel, M., and Lyons, C. S. (2011). An essay on contact angle measurements. Plasma Process. Polym. 8 (1), 8–13. doi:10.1002/ppap.201000041

Tavana, H., Simon, F., Grundke, K., Kwok, D. Y., Hair, M. L., and Neumann, A. W. (2005). Interpretation of contact angle measurements on two different fluoropolymers for the determination of solid surface tension. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 291 (2), 497–506. doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2005.05.001

Timoshenko, V., Bochenkov, V., Traskine, V., and Protsenko, P. (2012). Anisotropy of wetting and spreading in binary Cu-Pb metallic system: experimental facts and MD modeling. J. Mater. Eng. Perform. 21, 575–584. doi:10.1007/s11665-012-0184-5

Wang, H., Yin, Y., Wang, B., Liu, J., Xiong, W., Xiang, H., et al. (2014). Screening of the key factors from the physical characteristic of paper process reconstituted tobacco. Pap. Pap. Mak. 33 (2), 43–46. doi:10.13472/j.ppm.2014.02.012

Wang, L., Zhang, S., Yan, S., and Dong, S. (2022). Numerical simulation of droplet infiltration of micro-nano structure in Nepenthes slippery zone. J. Mech. Eng. 58 (3), 203–212. doi:10.3901/jme.2022.03.203

Wang, S., Liu, K., Yao, x., and Jiang, L. (2015). Bioinspired surfaces with superwettability: new insight on theory, design, and applications. Chem. Rev. 115 (16), 8230–8293. doi:10.1021/cr400083y

Wang, X., and Zhang, Q. (2020). Insight into the influence of surface roughness on the wettability of apatite and dolomite. Minerals 10 (2), 114. doi:10.3390/min10020114

Wang, Z., Chen, E., and Zhao, Y. (2018). The effect of surface anisotropy on contact angles and the characterization of elliptical cap droplets. Sci. China Technol. Sci. 61, 309–316. doi:10.1007/s11431-017-9149-1

Wang, Z., and Wallach, R. (2022). Modeling gravity-driven unstable flow in subcritical water-repellent soils with a time-dependent contact angle. Water Resour. Res. 58 (6). doi:10.1029/2021WR031859

Wenzel, R. N. (1949). Surface roughness and contact angle. J. Phys. Chem. 53 (9), 1466–1467. doi:10.1021/j150474a015

Xue, Z., Liu, M., and Jiang, L. (2012). Recent developments in polymeric superoleophobic surfaces. J. Polym. Sci. Part B Polym. Phys. 50 (17), 1209–1224. doi:10.1002/polb.23115

Ye, Z., and Mizutani, M. (2023). Apparent contact angle of curved and structured surfaces. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Aspects 677, 132337. doi:10.1016/j.colsurfa.2023.132337

Yolcu, H. (2017). Analogies to demonstrate the effect of roughness on surface wettability. Sci. Activities 54 (3-4), 70–73. doi:10.1080/00368121.2017.1364686

Yu, C., Sasic, S., Liu, K., Salameh, S., Ras, R. H., and van Ommen, J. R. (2020). Nature–Inspired self–cleaning surfaces: mechanisms, modelling, and manufacturing. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 155, 48–65. doi:10.1016/j.cherd.2019.11.038

Żenkiewicz, M. (2006). New method of analysis of the surface free energy of polymeric materials calculated with Owens-Wendt and Neumann methods. Polimery 51 (7-8), 584–587. doi:10.14314/polimery.2006.584

Zhang, Y., Yue, C., Li, J., Zou, C., Chen, Y., and Lei, L. (2020). Preliminary report on the scanning electron microscope observation of epidermal micromorphology during tobacco flue-curing. J. Yunnan Agric. Univ. 35 (1), 88–93. doi:10.12101/j.issn.1004-390X(n).201909009

Zhu, D., Zhang, Y., and Dai, P. (2007a). Novel characterization of wetting properties and the calculation of liquid-solid interface tension (Ⅱ). Sci. Technol. Eng. 7 (13), 3063–3069. doi:10.3969/j.issn.1671-1815.2007.13.005

Keywords: contact angle, wettability, surface microstructure, roughness, simulation

Citation: Tie J, Shen B, Qiao Y, Zhao W, Xu R, Wang M, Li K and Qian J (2024) Influence of microstructure on the wettability of tobacco leaves: a theoretical model and quantitative analysis. Front. Mater. 11:1485713. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2024.1485713

Received: 24 August 2024; Accepted: 25 November 2024;

Published: 11 December 2024.

Edited by:

Pierre J. J. Dumont, Institut National des Sciences Appliquées de Lyon (INSA Lyon), FranceReviewed by:

Martin Munz, Helmholtz Association of German Research Centers (HZ), GermanyJungang Jiang, Hubei University of Technology, China

Copyright © 2024 Tie, Shen, Qiao, Zhao, Xu, Wang, Li and Qian. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kecheng Li, bGlrZWNoZW5nQG5idS5lZHUuY24=; Jie Qian, cWlhbmppZUB6anRvYmFjY28uY29t

Jinxin Tie1

Jinxin Tie1 Wei Zhao

Wei Zhao Kecheng Li

Kecheng Li