- 1School of Materials Science and Engineering, Hanoi University of Science and Technology, Hanoi, Vietnam

- 2College of Technology and Trading, Thai Nguyen, Vietnam

- 3Multifunctional Ferroics Materials Lab, School of Engineering Physics, Hanoi University of Science and Technology, Hanoi, Vietnam

In this work, an in-situ Al3Ti–Al2O3 composite was optimally synthesized from raw powders via mechanical milling and conventional sintering processes. The strong influence of milling time on the promotion of the phase reaction between the initial TiO2 and Al materials was proven by using X-ray diffraction and surface morphology analysis. The obtained results showed that the milling process did not initiate any reaction between the raw TiO2 and Al materials. However, the milling process was important for creating a homogeneous powder mixture and refining the particle size of the powders. The Al3Ti–Al2O3 composites were completely formed after conventional sintering at 750°C for 30 min for a milling time of over 4 h. The highest obtained microhardness of the composite was approximately 130 HV, which was suggested to be related to the microstructure of the bulk composite specimen consisting of two main phases, the Al3Ti matrix and the Al2O3 particles dispersed in the matrix. A small portion of an unidentified phase, a Ti-rich compound, was found in the matrix together with a tiny fraction of AlTi3. We suggest that the optimal sintering process and mechanical milling are important key factors in fabricating bulk hardness Al3Ti–Al2O3 composite materials.

1 Introduction

Aluminum matrix composites, which benefit from a uniform microstructure, desirable phases, and superior mechanical properties in comparison with aluminum alloys, have been tried and used in numerous structural, nonstructural, and functional applications in different engineering sectors (Reddy et al., 2007; Singh and Chauhan, 2016; Yashpal et al., 2017; Chao et al., 2019; Zhang et al., 2020; Akhlaghi et al., 2022). Particulate-reinforced aluminum matrix composites have a growing demand in the aircraft and automotive industries due to their light weight, high specific strength, and corrosion resistance (Tang et al., 2014; Mitra, 2018; Salari et al., 2021). The use of aluminum intermetallic instead of aluminum as a matrix led to further improvement in the mechanical properties of the composite at higher temperatures (Milman et al., 2001); thus, aluminum intermetallic matrix composites have been widely developed for high-temperature applications. Among the intermetallics, tri-aluminide intermetallic Al3Ti has been commonly selected as a matrix due to its high specific strength at high temperature, relatively high melting point, and low density (Uenishi and Kobayashi, 1996; Mitra, 2018; Nayak and Murty, 2004; Schmidt et al., 2018). Furthermore, when reinforcement, such as Al2O3 particles, is introduced into the matrix, the composite exhibits good wear resistance and high-temperature strength. The Al3Ti–Al2O3 intermetallic matrix composite has shown potential application in the fields of aerospace, aircraft, and high-speed transportation (Schmidt et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2020).

Al3Ti–Al2O3 composites have been fabricated in different ways. Fukunaga and Wang used reactive melt infiltration of TiO2 whisker preforms with molten Al to fabricate in-situ Al3Ti–Al2O3 (Fukunaga et al., 1991). Their product was a composite material with a nonuniform microstructure, and thus, a large variation in the hardness of the composite was reported, that is, between 30 and 1050 HV (Fukunaga et al., 1991). Wang et al. prepared TiO2/Al mixtures by squeeze casting and subsequent sintering at 810°C and 910°C to produce Al2O3/TixAly in-situ composites, but an incomplete reaction was experienced in these works (Wang et al., 1993). A combination of squeeze casting and combustion synthesis has successfully been used to fabricate in-situ Al3Ti–Al2O3 from TiO2 and Al, and the fabricated composite showed superior compressive strength at high temperature (Peng et al., 2000). Another in-situ process using mechanical alloying in combination with chemical reaction in molten salt also successfully fabricated an Al3Ti-Al2O3 composite in powder form, and the powder was then consolidated into a bulk composite material (Verdian, 2010). Attempts were also successfully made to fabricate Al2O3/TiAl3-reinforced aluminum composites via the in-situ reaction between TiO2 and the Al matrix by using multiple friction stir processing or powder metallurgy (Zhang et al., 2011; Zhang et al., 2012; Binh et al., 2021). In one of these attempts, a composite with a high content of reinforcing particles (Al2O3 and Al3Ti) was fabricated by accumulative roll-bonding and spark plasma sintering. The composite exhibited high microhardness, high strength, and a good strength–ductility combination at elevated temperatures (Zhang et al., 2020). However, the main issues during fabrication were mixing the raw materials Al and TiO2 by controlling the ball-mining time before thermal treatment, which were not well investigated for archiving the optical processing. In particular, the TiO2 raw materials were homogenously distributed on the matrix surface of an aluminum foil to enhance the reaction. As mentioned above, dispersed aluminum intermetallic composites, especially tri-aluminide, such as Al3Ti, have been synthesized and tried in numerous structural, nonstructural, and functional applications in different engineering sectors due to their high melting points, ability to retain strength at elevated temperatures, and appreciable resistance to environmental degradation. The materials were successfully synthesized, either ex situ or in-situ, via different routes that included chemical reaction, combustion, and even casting. However, the properties of the fabricated composite materials varied depending on the synthesis process. In other words, the optimal fabrication process must be investigated to control the in-situ phase reaction.

In this work, an in-situ Al3Ti–Al2O3 composite was synthesized from aluminum and titanium dioxide powders via mechanical milling and conventional sintering. The in-situ formation of Al3Ti and Al2O3 during mechanical milling and sintering is expected to offer improved dispersion of the fine reinforcing particles, resulting in improved mechanical properties of the composite.

2 Experimental

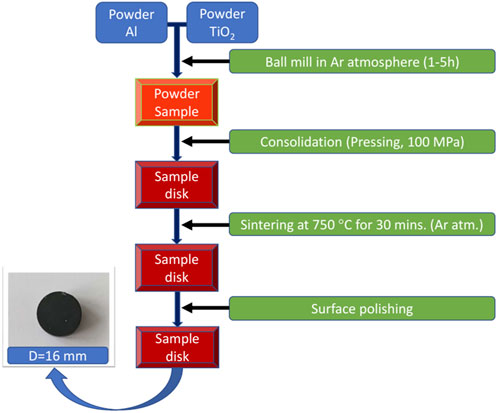

Aluminum (Al) and titanium dioxide (TiO2) powders were used as the starting materials for the fabrication of in-situ Al3Ti–Al2O3 composites. Aluminum (Al) powder was obtained from Merck, Germany, had a purity of 99% and average of 125 µm in particle size. Titanium dioxide powder was obtained from Xilong Chemical, China, had a purity of 99.5% and average of 0.2 µm in particle size. The Al and TiO2 powders were weighed according to the stoichiometric ratio of the reaction: 13Al + 3TiO2 → 3Al3Ti + 2Al2O3 by using the balance (KERN ABS220-4N). The raw powders were mixed and the mixture was then placed in a sealed grinding jar with a hardened steel ball as the grinding media. The ball-to-powder weight ratio was 10:1. The powder mixture was then milled in an planetary ball mill (NQM-4 planetary ball mill, China) at a rotation speed of 300 rpm. The mining time was changed from 1 h to 5 h with a step of 1 h. The milled sample was compressed into pellets 16 mm in diameter under 100 MPa pressure. Afterward, the sample disks were thermally treated at 750 °C for 30 min in an argon atmosphere using an electric furnace (Lenton EF11/8B, England). The surface of the as-fabricated samples was polished by using sandpaper, increasing in roughness from 80 CC-Cw to 2000 CC-Cw, and finally using Al2O3 powder. A sketch of the sample fabrication process is shown in detail in Figure 1. The phase composition was determined using X-ray diffraction (XRD, Smart Lab, Rigaku Corp., Japan). The surface morphologies and of the samples were characterized by using scanning electron microscopy (SEM, JSM7001FD, JEOL Ltd., Japan). The mapping of elements of samples were characterized by using energy dispersive X-ray (EDS, JSM7001FD, JEOL Ltd., Japan) spectroscopy. Microhardness was measured with the Vickers HMV-1 tester (Shimadzu Corp., Japan) under 245.2 mN and 15 s. The microhardness of samples was measured in at least three positions. The density of samples were measured based on Archimedes’ method by using the balance (OHAUS PX224).

3 Results and discussion

3.1 Microstructure and phase composition of the Al3Ti–Al2O3 composites

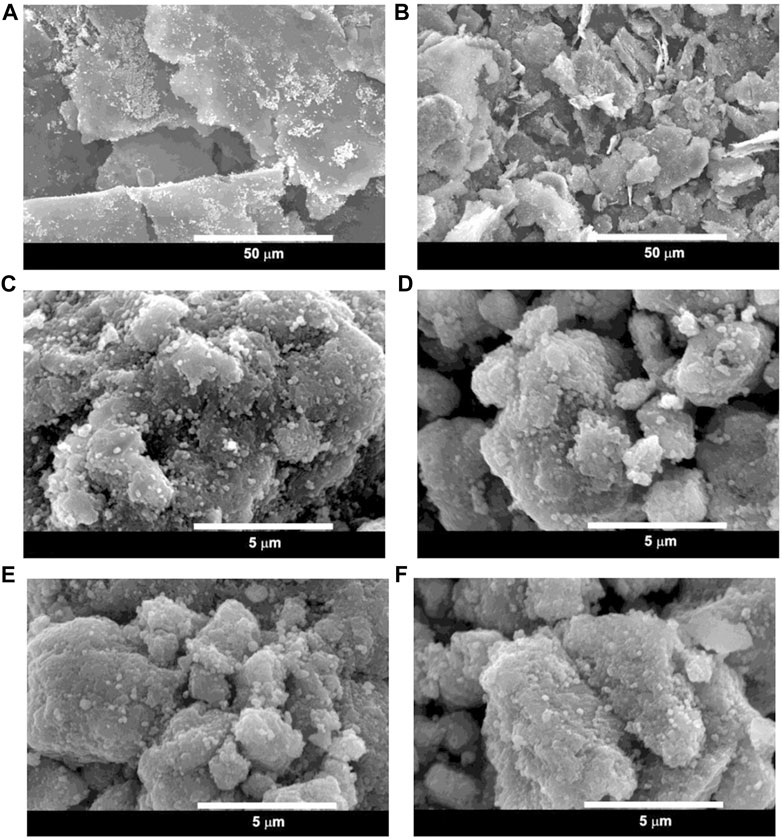

Figure 2 shows the SEM images of the Al–TiO2 powder mixture milled from the initial and milling times of up to 5 h. The results showed that the image of the nonmilling powder depicted that the raw aluminum powder has a relatively large particle size of approximately 70 ÷ 140 µm, and the size of titanium oxide powder is relatively smaller, i.e., approximately 250 ÷ 350 nm, as shown in Figure 2A. Before milling, the titanium dioxide particles were unevenly dispersed and adhered to the surface of the aluminum foil. After 1 h of milling, an improved distribution of TiO2 in the mixture was achieved, and the aluminum foils were broken down to approximately 20–30 µm in size, as shown Figure 2B. The surface morphologies of the Al–TiO2 powder mixture with increasing grinding time from 2 to 4 h are shown in Figures 2C–E. The results clearly showed that the aluminum particles no longer existed in the foiled form but changed to a rounded shape with fine TiO2 particles distributed evenly on the surface. Until ball milling, the raw Al–TiO2 powder for 5 h, the raw materials were well blended, and the TiO2 particles were almost indistinguishable from aluminum, as shown in Figure 2F. The results indicated that the milling time enhanced the distribution of TiO2 powder in the host Al matrix. In other words, the mechanical milling process has shown its effectiveness in producing deformations and defects in the raw powders and increasing the temperature in the jar during milling might facilitate the diffusion process. As the milling time increased, the aluminum particles were broken, crushed, and mixed with the titanium dioxide particles. The increase in temperature in the jar during milling also increased.

FIGURE 2. SEM images of (A) initial Al–TiO2 powders and Al–TiO2 milled at different milling times: (B) 1 h, (C) 2 h, (D) 3 h, (E) 4 h, and (F) 5 h.

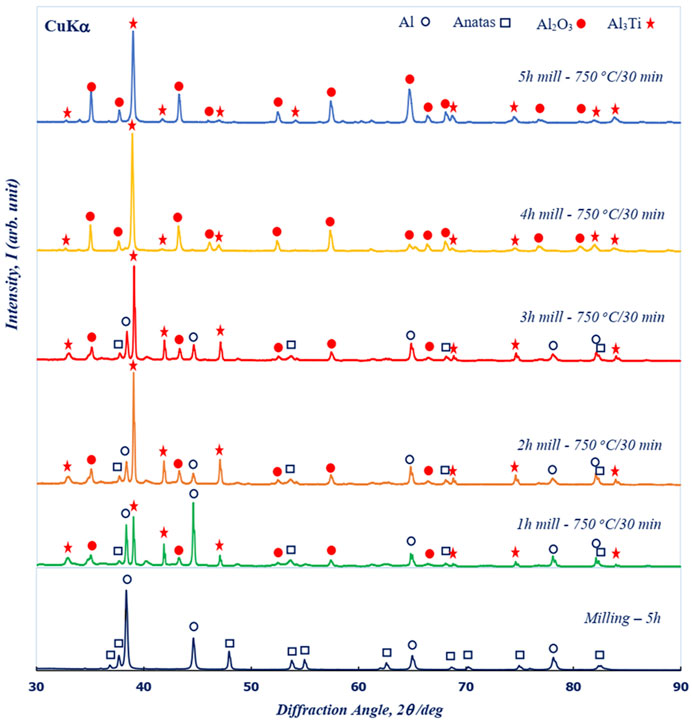

The phase forms in Al–TiO2 powder before and after thermal treatment as a function of milting time are shown in Figure 3. The XRD patterns of samples with 5 h of milled powder showed that only Al and TiO2 phases were obtained in the XRD patterns, indicating that the milling process only promoted the homogeneous distribution of TiO2 (PDF Card No. 01-075-1537) into the host Al matrix (PDF Card No. 00-001-1176), whereas no reaction to form the new phase occurred. The observation results further confirmed that the milling process only enhanced the mixing between raw Al and TiO2 powders. In other words, the milling process simply refines the sizes of the aluminum particles and creates an even distribution of the TiO2 particles in the powder mixture. Evidence of the influence of milling time on the phase form was clearly obtained in the XRD pattern, as shown for various milling times. The main diffraction peaks of the Al2O3 (PDF Card No. 00-005-0712) and Al3Ti (PDF card No. 03-065-4202) phases were obtained in the XRD spectra for 1 h milling, indicating that the reaction between TiO2 and Al already occurred after thermal treatment at 750°C for 30 min. Our results were consistent with recently reported characterization of the reaction of TiO2 and Al (Zhang et al., 2011). The observation results showed that the Al2O3 and Al3Ti phases already formed even with a low milling time of 1 h. However, the strong main diffraction peaks of Al and TiO2 still appeared in the XRD patterns for samples fabricated with milling times from 1 h to 3 h. The main intensity of the Al and TiO2 peaks tended to decrease as the milling time increased and completely disappeared when the milling time increased over 4 h. Thus, we suggested that a short milling time could not evenly distribute the TiO2 into the aluminum, resulting in low energy for the full formation of Al3Ti and Al2O3. The observation results indicated that controlling the milling time was one of the key factors for enhancing the phase form during thermal treatment.

FIGURE 3. XRD pattern of sintered composites at 750°C for 30 min in an Ar environment as a function of milling time. The XRD pattern in the lowest figure is that of milling at 5 h before thermal treatment.

The formation of Al-Ti intermetallic in the system was the results of the following reactions (Khoshhal et al., 2010; Zhang et al., 2011; Binh et al., 2021):

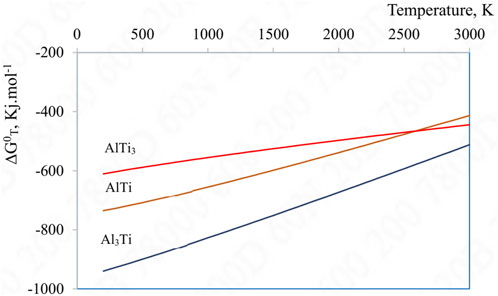

For further information, the Gibbs free energy of the reactions were calculated based on thermodynamic data from literatures which were shown in Figure 4 (Kattner et al., 1992; Gui-rong et al., 2010; Khoshhal et al., 2010). Thermodynamic calculations indicated that the Gibbs free energy of the (3.1) reaction was the lowest in a wide range of temperature, followed by the (3.2) and finally the (3.3) reaction. Therefore, the (3.1) reaction was in favor and the Al3Ti was the favorable intermetallic to be formed. Other thermodynamic assessment of the Al-Ti intermetallic formation also concluded this order of intermetallic formation, the Al3Ti has the lowest Gibbs free energy of formation, followed by the AlTi, and finally the AlTi3 (Kattner et al., 1992; Khoshhal et al., 2010).

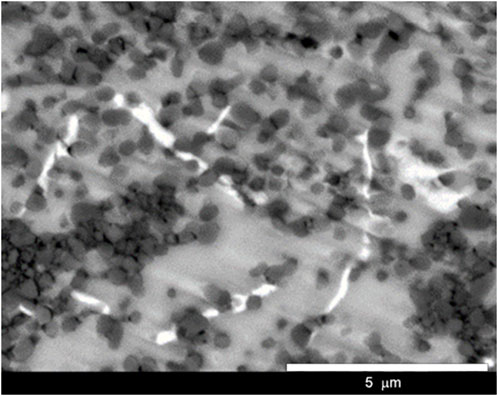

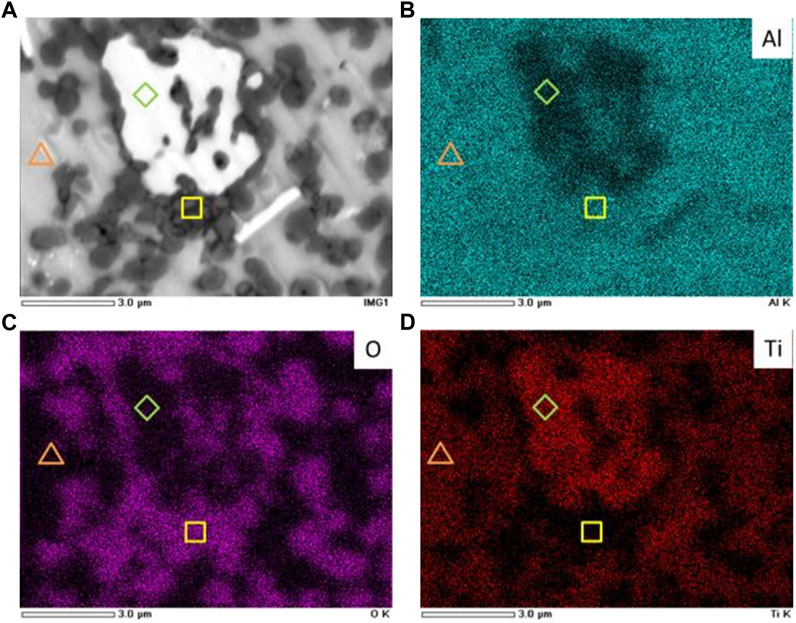

To investigate further the distribution of the phases in the samples, samples were fabricated with a ball milling time of 4 h. The surface morphology of the samples is shown in Figure 5A. The SEM results exhibited three regions consisting of bright, gray, and dark regions. The observation results suggested that the microstructure of the samples consisted of three components, where small dark particles were distributed on a gray matrix and a small white grain was occasionally present. The size of the dark particle was approximately 1–2 µm, and its distribution was not uniform throughout the matrix. Furthermore, EDS mapping for Al, O, and Ti, as shown in Figures 5B–D, respectively, suggested that the dark particles were aluminum–oxygen compounds, the gray matrix was a compound of aluminum and titanium, and the bright grain was a Ti-rich phase. On the basis of the crystal structural analysis, we suggested that the gray matrix was Al3Ti, whereas the dark particles were Al2O3, and the white grain composition remained unidentified.

FIGURE 5. (A) SEM image and selected EDS mappings of (B) Al, (C) O, and (D) Ti for samples milled for 4 h.

The formation of the in situ Al3Ti–Al2O3 composite could be divided into two stages. Initially, the reaction between the two raw materials, i.e., aluminum and titanium dioxide, leads to the formation of alumina and titanium metal by the following reaction equation:

Thus, the titanium metal then reacts with aluminum and forms Al3Ti by the following reaction equation:

Thermodynamically, the formation of Al3Ti is favored because of the subzero Gibbs free energy of the reaction. The mechanism of the reaction is believed to be that the titanium atom diffuses into the crystal lattice of aluminum; thus, Al3Ti has the lattice structure of aluminum (FCC). This reaction continues until the titanium metal is exhausted.

If the raw material had excess aluminum, then the final product includes Al2O3, Al3Ti, and Al. If there was excess titanium, AlTi and AlTi3 could be formed in accordance with the following reaction processing steps:

On the basis of the observation of crystal structural analysis combined with surface morphology, a Ti-rich phase was found in the composite specimen, which indicated the presence of excess titanium in the raw material. In this case, the excess titanium might have caused the formation of the unidentified Al–Ti compound in the composite. Furthermore, the surface morphologies of samples fabricated at a milling time of 5 h are shown in Figure 6. The results showed that the Al2O3 particles were finer in size and had a better distribution in the matrix than those of samples fabricated with a milling time of 4 h, as shown in Figure 5A. The surface morphologies of the samples showed that the Ti-rich grains broke into thin streaks and remained in the composite. The observation results were consistent with the XRD characterization observations. In addition, the archived results further confirmed that the milling time was a key factor for enhancing the reaction of raw materials to form the phase during thermal treatment.

An increase in milling time provides extra energy for the reactions. Given that a change in the Ti-rich phase structure occurred, the Ti-rich phase can possibly react with other components to form a new phase. As suggested above, AlTi and AlTi3 intermetallics could be formed in the matrix. The energy provided after 5 h of milling and sintering at 750°C for 30 min was not enough to initiate the formation of large-scale AlTi/AlTi3 intermetallics, and the phases might appear after longer milling and/or higher temperature sintering.

3.2 Densification and microhardness of the synthesized Al3Ti–Al2O3 composites

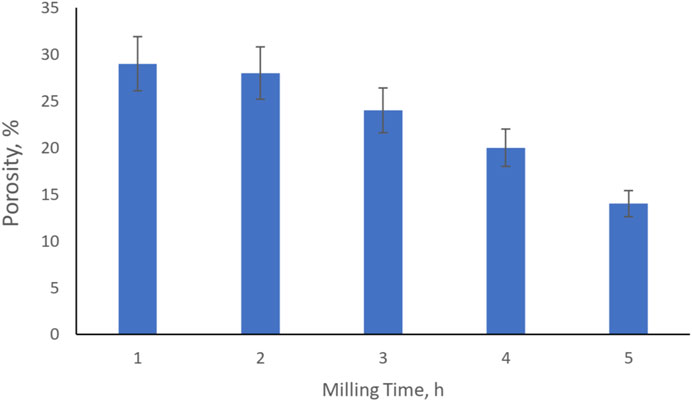

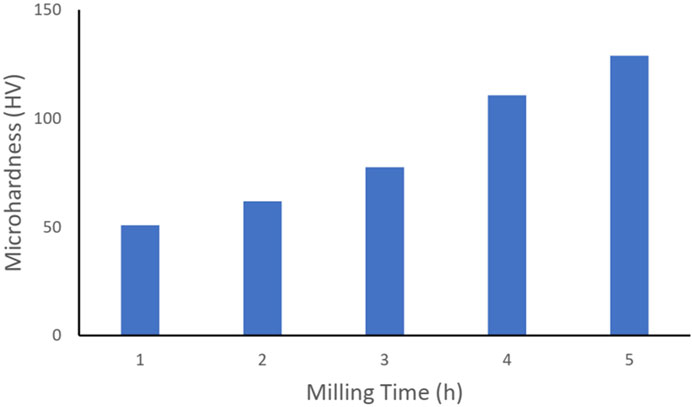

The influence of milling time on the porosity and the microhardness of the Al3Ti–Al2O3 composites is shown in Figures 7, 8, respectively.

As depicted in Figure 7, the porosity of the material ranges from approx. 14 ÷ 28%, which is relatively large for composite material. Low compaction pressure during compaction could be one of the causes while the others might be short milling time and relatively low sintering temperature. Longer milling time might help refine the particles and give better distribution of the components, as the porosity decreased from approx. 20% down to 14% when milling time increased from 4 to 5 h.

The observation results showed that the microhardness of the composite dramatically increased as the milling time increased from 1 h to 5 h, as shown in Figure 8. At a short milling time of 1 h, the microhardness was approximately 50 HV but dramatically increased to approximately 130 HV when the milling time was raised to 5 h. The microhardness obtained in this work was comparable to those reported for the Al–Al3Ti–Al2O3 composite, also fabricated by the powder metallurgy route, which is approximately 140 HV (Lakra et al., 2020). Similar composites prepared by other methods, such as thermal decomposition, have considerably lower microhardness, i.e., approximately 50 HV (Azarniya and Hosseini, 2015). Increasing the milling time was expected to enhance the Al3Ti distribution in the Al2O3 matrix, resulting in an enhancement in the microhardness. Thus, we suggested that an increase in milling time resulted in a smaller grain size, improved material diffusion, and thus created a more uniform structure, resulting in an improved microhardness of the composite.

4 Conclusion

An in situ Al3Ti–Al2O3 intermetallic matrix composite was successfully fabricated from aluminum and titanium dioxide powders via mechanical milling and conventional sintering. The mechanical milling process alone was unable to initiate any reaction between the raw materials, and the formation of Al3Ti and Al2O3 only took place after sintering. The microstructure of the composites consisted of two main phases, a fine Al2O3 particle distributed on the Al3Ti matrix. An unidentified Al–Ti compound was also found in small portions together with a tiny AlTi3 intermetallic compound on the matrix. The highest measured microhardness was approximately 130 HV.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BND: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Software, Visualization, Writing–original draft. BTD: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Methodology, Resources, Software, Validation, Writing–review and editing. DD: Data curation, Formal Analysis, Software, Validation, Writing–review and editing. HT: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Visualization, Writing–original draft, Writing–review and editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. The work was supported by The National Foundation for Science and Technology Development of Vietnam under Grant No. 103.02-2017.349.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Akhlaghi, M., Salahi, E., Tayebifard, S. A., and Schmidt, G. (2022). Role of SPS temperature and holding time on the properties of Ti3AlC2-doped TiAl composites. Synthesis Sinter. 2, 138–145. doi:10.53063/synsint.2022.2383

Azarniya, A., and Hosseini, H. R. M. (2015). A new method for fabrication of in situ Al/Al3Ti–Al2O3 nanocomposites based on thermal decomposition of nanostructured tialite. J. Alloys Comp. 643, 64–73. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2015.04.145

Binh, D. T., Huy, T. D., Thuong, T. V., Binh, D. N., and Miyamoto, H. (2021). Fabrication, microstructure, and microhardness at high temperature of in situ synthesized Ti3Al/Al2O3 composite. Metals 11, 617. doi:10.3390/met11040617

Chao, Z. L., Zhang, L. C., Jiang, L. T., Qiao, J., Xu, Z. G., Chi, H. T., et al. (2019). Design, microstructure and high temperature properties of in-situ Al3Ti and nano-Al2O3 reinforced 2024Al matrix composites from Al-TiO2 system. J. Alloys Comp. 775, 290–297. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2018.09.376

Fukunaga, H., Wang, X., and Aramaki, Y. (1991). Preparation of intermetallic compound matrix composites by reaction squeeze casting. J. Mat. Sci. Lett. 10, 23–25. doi:10.1007/BF00724421

Gui-rong, L., Hong-ming, W., Yu-tao, H., Deng-bin, C., Gang, C., and Xiao-nong, C. (2010). Microstructure of in situ Al3Ti/6351Al composites fabricated with electromagnetic stirring and fluxes. Trans. Non. Mater. China 20, 577–583. doi:10.1016/S1003-6326(09)60181-3

Kattner, U. R., Lin, J. C., and Chang, Y. A. (1992). Thermodynamic assessment and calculation of the Ti-Al system. Metall. Mat. Trans. A Phys. 23, 2081–2090. doi:10.1007/BF02646001

Khoshhal, R., Soltanieh, M., and Mirjalili, M. (2010). Formation and growth of titanium aluminide layer at the surface of titanium sheets immersed in molten aluminum, Iran. J. Mat. Sci. 7, 24–31.

Lakra, S., Bandyopadhyay, T. K., Das, S., and Das, K. (2020). Synthesis and characterization of in-situ (Al–Al3Ti–Al2O3)/Al dual matrix composite. J. Alloys Comp. 842, 155745. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.155745

Milman, Y. V., Miracle, D. B., Chugunova, S. I., Voskoboinik, I. V., Korzhova, N. P., Legkaya, T. N., et al. (2001). Mechanical behaviour of Al3Ti intermetallic and L12 phases on its basis. Intermetallics 9, 839–845. doi:10.1016/S0966-9795(01)00073-5

Mitra, R. (2018). Chapter 1: Structural intermetallics and intermetallic matrix composites: An introduction. Sawston, United Kingdom: Woodhead Publishing, 1–18. doi:10.1016/B978-0-85709-346-2.00001-7

Nayak, S. S., and Murty, B. S. (2004). Synthesis and stability of L12–Al3Ti by mechanical alloying. Mat. Sci. Eng. A 367, 218–224. doi:10.1016/j.msea.2003.09.097

Peng, H. X., Fan, Z., and Wang, D. Z. (2000). In situ Al3Ti-Al2O3 intermetallic matrix composite: synthesis, microstructure, and compressive behavior. J. Mat. Res. 15, 1943–1949. doi:10.1557/JMR.2000.0280

Reddy, B. S. B., Das, K., and Das, S. (2007). A review on the synthesis of in situ aluminum based composites by thermal, mechanical and mechanical–thermal activation of chemical reactions. J. Mat. Sci. 42, 9366–9378. doi:10.1007/s10853-007-1827-z

Salari, M. A., Muglu, G. M., Rezaei, M., Kumar, M. S., Pulikkalparambil, H., and Siengchin, S. (2021). In-situ synthesis of TiN and TiB2 compounds during reactive spark plasma sintering of BN-Ti composites. Synthesis Sinter. 1, 48–53. doi:10.53063/synsint.2021.119

Schmidt, A., Siebeck, S., Götze, U., Wagner, G., and Nestler, D. (2018). Particle-reinforced aluminum matrix composites (AMCs)—Selected results of an integrated technology, user, and market analysis and forecast. Metals 8, 143–154. doi:10.3390/met8020143

Singh, J., and Chauhan, A. (2016). Characterization of hybrid aluminum matrix composites for advanced applications – A review. J. Mat. Res. Tech. 5, 159–169. doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2015.05.004

Tang, P. Y., Li, J. Y., Huang, G. H., and Xie, Q. L. (2014). Uniaxial loading response of one dimensional long period structures of Al3Ti. Comp. Mat. Sci. 91, 153–158. doi:10.1016/j.commatsci.2014.04.061

Uenishi, K., and Kobayashi, K. F. (1996). Processing of intermetallic compounds for structural applications at high temperature. Intermetallics 4, 95–101. doi:10.1016/0966-9795(96)00016-7

Verdian, M. M. (2010). Synthesis of TiAl3-Al2O3 composite particles by chemical reactions in molten salts. Mat. manu. Proc. 25, 953–955. doi:10.1080/10426911003720748

Wang, D. Z., Liu, Z. R., Yao, C. K., and Yao, M. (1993). A novel technique for fabricating in situ Al2O3/TixAly composites. J. Mat. Sci. Lett. 12, 1420–1421. doi:10.1007/BF00591594

Wang, P., Eckert, J., Prashanth, K. G., Wu, M. W., Kaban, I., Xi, L. X., et al. (2020). A review of particulate-reinforced aluminum matrix composites fabricated by selective laser melting. Tran. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 30, 2001–2034. doi:10.1016/S1003-6326(20)65357-2

Yashpal, Sumankant, Jawalkar, C. S., Verma, A. S., and Suri, N. M. (2017). Fabrication of aluminium metal matrix composites with particulate reinforcement: A review. Mat. Today Proc. 4, 2927–2936. doi:10.1016/j.matpr.2017.02.174

Zhang, G. P., Mei, Q. S., Li, C. L., Chen, F., Mei, X. M., Li, J. Y., et al. (2020). Fabrication and properties of Al-TiAl3-Al2O3 composites with high content of reinforcing particles by accumulative roll-bonding and spark plasma sintering. Mat. Today Commun. 24, 101060. doi:10.1016/j.mtcomm.2020.101060

Zhang, Q., Xiao, B. L., Wang, Q. Z., and Ma, Z. Y. (2011). In situ Al3Ti and Al2O3 nanoparticles reinforced Al composites produced by friction stir processing in an Al-TiO2 system. Mat. Lett. 65, 2070–2072. doi:10.1016/j.matlet.2011.04.030

Keywords: Al3Ti–Al2O3, intermetallic matrix composite, in-situ synthesis, mechanical milling, powder metallurgy

Citation: Duong BN, Do BT, Dang DD and Tran HD (2023) Fabrication and hardness of in-situ Al3Ti–Al2O3 composite. Front. Mater. 10:1265903. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2023.1265903

Received: 24 July 2023; Accepted: 24 August 2023;

Published: 05 September 2023.

Edited by:

Amir Motallebzadeh, Koç University, TürkiyeReviewed by:

Hadi Jahangiri, Koç University, TürkiyeMehdi Shahedi Asl, University of Kyrenia, Cyprus

Copyright © 2023 Duong, Do, Dang and Tran. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Huy D. Tran, aHV5LnRyYW5kdWNAaHVzdC5lZHUudm4=

Binh N. Duong

Binh N. Duong Binh T. Do1,2

Binh T. Do1,2 Dung D. Dang

Dung D. Dang Huy D. Tran

Huy D. Tran