94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mater., 05 May 2022

Sec. Quantum Materials

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2022.894097

This article is part of the Research TopicInnovators in Quantum MaterialsView all 5 articles

The defects contained in amorphous SiO2/Si (a-SiO2/Si) interface have a considerable impact on the efficiency and stability of the device. Since the device is exposed to the atmospheric environmental conditions chronically, its performance will be limited by water diffusion and penetration. Here, we simulated the interaction of H2O and interface defects in a-SiO2/Si(100) by using the first-principles method. Our results suggest that H2O penetrated into Pb0 defect is more inclined to interact with the network in the form of silanol (Si-OH) group, while H2O incorporated into Pb1 defect is more likely to remain intact, which can be attributed to the location of Pb1 defect closer to the interface than that of Pb0 defect. Our research provides a powerful theoretical guidance for the interaction of H2O and interface defects in a-SiO2/Si(100).

Amorphous silicon dioxide (a-SiO2) is an important component of Metal-Oxide-Semiconductor Field-Effect Transistors (MOSFET) (Sheikholeslam et al., 2016), optical fibers and solar cells (Stesmans and Afanas’ev, 1998; Watanabe et al., 1998; Matsudo et al., 2002; Kajihara et al., 2005; Pamungkas et al., 2011), which has a huge impact on the reliability of the device as a basic element of modern technology (Gerardi et al., 1986; Rochet et al., 1997; Lenahan and Conley, 1998; Kovačević and Pivac, 2014). In practical applications, it is usually plagued by defects and impurities such as hydrogen (H) (McLean, 1980; Stesmans, 1996; Chadi, 2001; Pantelides et al., 2007), water (H2O) (Takahashi et al., 1993; Batyrev et al., 2008) and alkali metal (Perez-Beltran et al., 2015), and these factors will change the mechanical, electronic (Blöchl and Stathis, 1999) and optical (Griscom, 1991) properties of a-SiO2. Among the electroactive defects in a-SiO2/Si interface with different Si surface orientations, Pb center occupies a principal position. It is essentially a tripod-like structure consisting of an isolated Si dangling bond and three reverse-bonded Si atoms (∙Si-(-Si)3) (Helms and Poindexter, 1994). The most technologically crucial Si surface with (100) orientation contains two Pb variants, namely Pb0 (Haneji et al., 1991; Yamasaki et al., 2003; Thoan et al., 2011) and Pb1 (Stirling et al., 2000; Campbell and Lenahan, 2002; Kato et al., 2006). Although both of them have a common form of ∙Si-(-Si)3, they are quite different in terms of orientation and hyperfine parameters, and these interface defects are the main factors affecting device performance.

In reality, the interface dangling bond defects in device preparation can be passivated by H into a non-electrically active Si-H structure, which will not influence the quality of the device. However, if exposed to the environment of ionizing radiation for a long time, the defects that have been passivated will be reactivated by the protons generated by the radiation, and the activated dangling bonds will accumulate charges by trapping the carriers, which may cause the degradation and even failure of the device performance (Michalske and Freiman, 1983; Lu et al., 1993; Kosowsky et al., 1997). Besides, H2O plays a significant role in the properties of a-SiO2/Si interface (Pfeffer and Ohring, 1981; Tomozawa, 1985; Bourg and Steefel, 2012). Due to the fascinating network pattern, it can form an amorphous structure with SiO2 surface according to the strength of the interaction between them. Especially the interaction of H2O and interface defects in a-SiO2/Si(100), which is the main concern of scientific research. Since H2O always exists in the atmosphere, its role in experiments is ineluctable under any achievable ultra-high vacuum pressure conditions. The interaction of H2O and interface defects may cause hydrolysis in a-SiO2/Si(100), which is possible to form a silanol (Si-OH) site attached to the silicon defect atom (Li et al., 2009; Yeon and Van Duin, 2016), and the remaining proton (H+) after hydrolysis can continue to interact with Pb0-H that has been passivated to generate

The present work focuses on the interaction of H2O and Pb0/Pb1 defects in a-SiO2/Si(100) interface, and clearly reproduces the specific process of the reaction, as well as the variation of bond length and potential barrier during the reaction. The framework of the manuscript is as follows: The Section 2 introduces the calculation method. The Section 3 contains the simulation results and discussion, and the conclusion is drawn in the Section 4.

All of the calculations are performed based on the density functional theory (DFT) using the projector augmented wave (PAW) method, which is implemented in Vienna ab-initio simulation package (VASP) (Parr, 1983; Blöchl, 1994; Hafner, 2008). Perdew-Burke-Ernzerhof (PBE) parametric generalized gradient approximation (GGA) is applied to deal with the exchange-correlation functional (Perdew et al., 1996). In addition, the models of Pb0 and Pb1 defects used in our study are both derived from Li et al. (Li et al., 2019a). Considering the large number of atoms in the system (more details in Supplementary Material S1), a step-by-step iterative method is adopted to optimize the structure to minimize the consumption of computing resources, where the cut-off kinetic energies are set to 300 and 500 eV, and the atomic positions are fully relaxed until the total energy and residual force ultimately converge to 10−5 eV and 0.01 eV/Å, respectively. The Brillouin zone (BZ) is only selected for sampling and integration at the Γ point (Monkhorst and Pack, 1976). Finally, the activation energy of H2O embedded in a-SiO2/Si(100) interface is measured by using the Climbing Image Nudged Elastic Band (CI-NEB) method, which makes a corrective improvement on the traditional NEB method by combining the climbing mirror image and the definition of the tangent, so as to search for more accurate saddle points with fewer intermediate images (Henkelman et al., 2000; Sheppard et al., 2012).

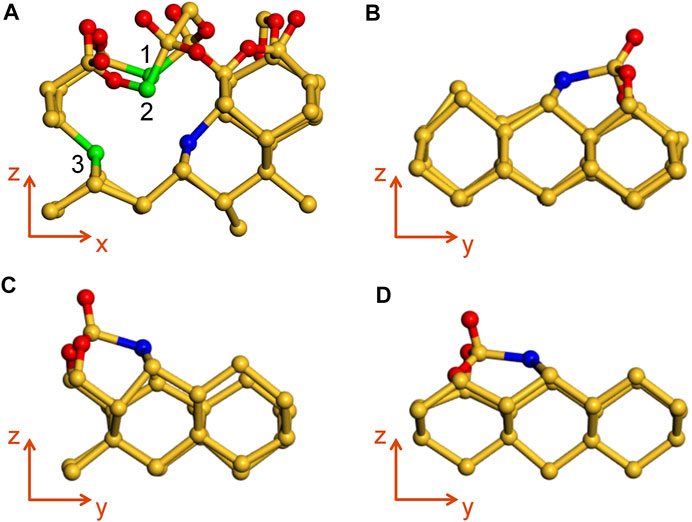

Firstly, the defects in a-SiO2/Si(100) interface are briefly introduced to facilitate the subsequent simulation of its reaction with H2O. There are two different types of defects in a-SiO2/Si(100) interface, namely Pb0 and Pb1 defects. Among them, Pb0 defect is located in the second unoxidized silicon atomic layer adjacent to the interface transition zone, and it is constructed by removing one of the Si atoms from the unoxidized top layer on the silicon side, which can be represented as ∙Si-(-Si)3, as shown by the blue Si defect atom in Figure 1A. The dangling bond of it lies along the [111] direction (54.74°) (Li et al., 2019b), and the remaining dangling bonds of three defect atoms (silicon atoms 1, 2 and 3 in Figure 1A) can be passivated by hydrogen atoms into the form of Si-H, which has no effect on the defect model due to the lack of electrical activity.

FIGURE 1. (A) The schematic diagram of Pb0 defect model. (B–D) Pb1 defect models with AOD configuration at three randomly selected positions. Blue spheres indicate the location of Pb0/Pb1 defects; green silicon atoms will be passivated by hydrogen atoms to saturate dangling bonds in subsequent reaction simulations; yellow and red spheres represent Si and O atoms, respectively.

In addition to Pb0 defect, the a-SiO2/Si(100) interface also involves another dangling bond defect, whose defect density is lower than that of Pb0, which is called Pb1 defect. Different from Pb0 defect, Pb1 is created by removing one of the oxygen atoms from a-SiO2/Si(100) interface, resulting in it being located on the top layer of bulk silicon and the dangling bond is roughly along the [112] direction (30–36°) (Li et al., 2019b), which is not consistent with any chemical bond orientation. A more intuitive schematic diagram of the location of Pb0 and Pb1 defects in a-SiO2/Si(100) is shown in Supplementary Figure S2. Moreover, Pb1 defect is extremely sensitive to the local structure deformation. Depending on the different positions of the defect, it can be divided into dimer, bridge and AOD (asymmetric oxidized dimer) models, and the latter has been verified to be superior to the former two in terms of Fermi contact value and dangling bond orientation (Poindexter et al., 1981) (more details in Supplementary Figure S3). Considering that the interface transition region of the amorphous model is more complicated than that of the crystal model, the atomic configuration around the defects of a-SiO2/Si(100) interface will significantly influence the simulation results. In order to make the results more convincing, we simulated the reaction process between Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at three random positions (as shown in Figures 1B–D) and H2O, and compared the reaction results to obtain a more reliable conclusion.

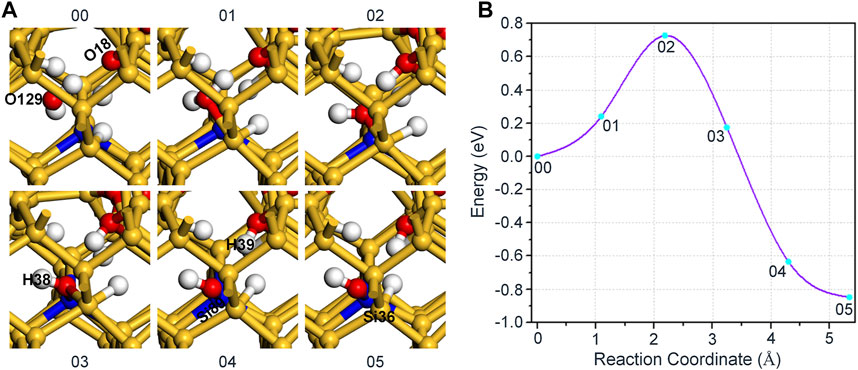

Here, we will simulate the interaction of H2O and Pb0 defect concretely. First, place a H2O at an appropriate position around the defect atom (Si89), and make sure that it does not bond with other atoms near the defect, so the initial state 00 for the reaction of Pb0 defect and H2O is constructed, as shown in Figure 2A. For the final state 05, one hydrogen atom (H39) in H2O is attached to the nearest neighboring oxygen atom (O18) with a form of proton, while the remaining hydroxyl group is bonded with Si89 to passivate the dangling bond defect, so that the system can reach a stable structure. Furthermore, we have subtracted an electron from the initial state to ensure the conservation of the electron numbers before and after the reaction, whose equation can be expressed as:

FIGURE 2. (A) The schematic diagram of the reaction between Pb0 defect and H2O. H2O in the initial state 00 exists freely around the defect atom (Si89), and three unsaturated silicon atoms marked by green spheres in Figure 1A are passivated by the adhesion of H atoms. (B) The variation of the energy with different reaction coordinates for the reaction of H2O and Pb0 defect.

After determining the initial and final state of the reaction, the CI-NEB method based on first-principles calculation is employed to simulate the reaction process of H2O and Pb0 defect in a-SiO2/Si(100) interface, as shown in Figure 2A. Compared with Si89, H2O is closer to the silicon atom (Si36) passivated by H atom (2.500 Å), thereby the oxygen atom (O129) in H2O prefers to connect with Si36 in the initial stage. This step can cause Si36 to change from a quadruple to a quintuple coordination, which will further increase the energy of the system, as shown in Figure 2B. Next, H39 in H2O detaches from its parent and gradually approaches the position of O18 until after connection with it, thus reaching the saddle point 02 of the reaction. As the reaction continues, the distance between H2O and Si89 gradually becomes smaller, so that they are linked to each other, and the energy of the system begins to show a downward trend. Moreover, the increase in the distance between H2O and Si36 passivated by hydrogen atom leads to the cleavage of the Si36-O129 bond, then Si36 is also restored to a stable quadruple coordination from the preceding quintuple coordination. Finally, H39 in H2O is bonded with O18 (1.006 Å) in a form of proton, while the remaining hydroxyl group is bonded with Si89 (1.685 Å) in order to passivate the dangling bond defect, so that the system reaches the most stable state. As shown in Figure 2B, the forward and reverse reaction barriers are 0.73 and 1.58 eV, respectively. In the whole reaction, the variation of interatomic bond length around the defect is shown in Table 1.

In the above reaction, we noticed that when the hydroxyl group in H2O passivates the dangling bond, the position of O129 is closer to Si36 passivated by hydrogen atom than Si89. As a result, the hydroxyl group in H2O is easier to interact with Si36, which makes Si36 vary from quadruple to quintuple coordination, resulting in an overall increase of the energy. In order to avoid this situation from adversely affecting the reaction, we adjusted the spatial position of Si36 accordingly. At the same time, the direction of the dangling bond passivated by hydrogen atom is also changed from the original

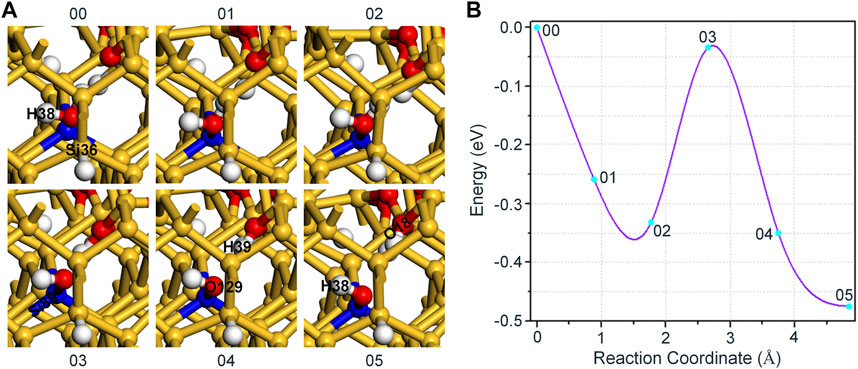

As shown in Figure 3A, we reconstructed the initial and final state of the reaction according to Eq. 1. On this occasion, H2O first moves towards the position of Si89 and bonds with it to achieve the expected purpose of passivating dangling bond, which results the energy of intermediate states 01 and 02 being lower than initial state 00 of the system, as shown in Figure 3B. Subsequently, the distance between O129 in H2O and Si89 gradually decreases, and H39 in H2O also combines with O18 in a form of proton, which makes the reaction reach the saddle point 03. Finally, with the continuous optimization of the positions about the hydroxyl group and proton, the energy of the system is also reduced to a minimum. In the entire reaction, the variation of interatomic bond length around the defect is shown in Table 2. Remarkably, the hydroxyl group used to passivate the dangling bond in the reaction is no longer interfered by Si36, which also proves that our adjustment to Pb0 defect model is more conducive to simulate the real reaction of H2O and Pb0 defect in a-SiO2/Si(100).

FIGURE 3. (A) The schematic diagram of the reaction between Pb0 defect and H2O. The orientation of the dangling bond (Si36) is changed from

In addition, we can observe from Figure 3B that the energy of the intermediate state 02 is about 0.33 eV lower than that of the initial state 00. Taking into account that the structure of the intermediate state 02 can also meet the requirement of Eq. 1 for the reactants. Therefore, the intermediate state 02 is subsequently selected as the initial state structure of the reaction between H2O and Pb0 defect, but the final state structure remains unchanged. In the following simulation, we directly choose the model with a lower energy as the initial state of the reaction, which enables H2O to passivate the dangling bond defect rather than existing in a free form.

In Figure 4A, the slight movement of H2O towards Si89 leads to a decrease in the distance between H39 and O18, which in turn increases the energy of the system by 0.11 eV. When the absorbed energy reaches 0.44 eV, H39 in H2O breaks with the oxygen atom connected to it, and combines with O18 in a form of proton to reach the highest energy state, which is the saddle point of the reaction. After that, with the continuous optimization of the positions about the hydroxyl group and proton, the system finally reaches an equilibrium state. In the whole reaction, the variation of interatomic bond length around the defect is shown in Table 3. Also, Figure 4B shows that, the forward and reverse reaction barriers are approximately the same, 0.44 and 0.46 eV, respectively. It is worth noting that the energy of the final state 05 is lower than that of the initial state 00 in all three cases, which indicates that the passivation of dangling bond defect by hydroxyl group is more stable than that by H2O for the interaction of H2O and Pb0 defect in a-SiO2/Si(100) interface.

FIGURE 4. (A) The schematic diagram of the reaction between Pb0 defect and H2O. H2O in the initial state 00 takes the form connected with Si89 instead of the free form. (B) The variation of the energy with different reaction coordinates for the reaction of H2O and Pb0 defect.

Now, we perform computational simulations on the interaction of H2O and Pb1 defects at three random locations. According to the analysis in the last section, the initial state 00 of this part adopts the form of bonding between H2O and triple coordinated silicon defect atom (Si84). In addition, in order to ensure the conservation of the number of electrons in the system before and after the reaction, we have subtracted an electron from the structural model of the initial state 00. The reaction equation can be written as:

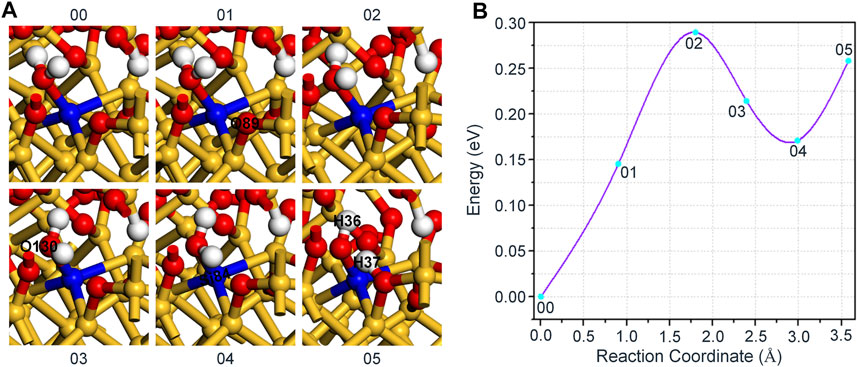

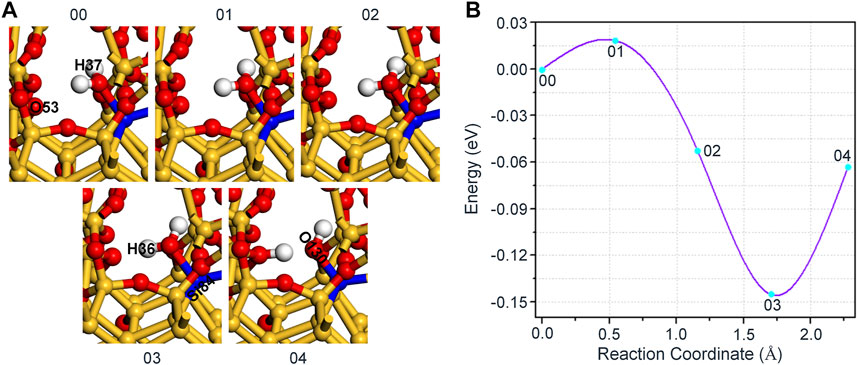

For the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 1, two oxygen atoms with different coordinates are selected to establish the final state, where the length of O-H bond is 1.502 Å and 1.907 Å, respectively. The relaxation results show that the hydrogen atom in H2O cannot combine with the nearest oxygen atom in a form of proton, and it still appears that H2O is intactly attached to the triple coordinated Si84. Our solution is to specify an oxygen atom (O89) that is relatively far away (3.153 Å) from the hydrogen atom (H37) in H2O and bond with it as the final state 05 of the reaction. Hereby, we speculate that it is relatively stable to passivate the dangling bond defect with H2O for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 1.

The detailed reaction process is shown in Figure 5A. At first, H37 in H2O gradually approaches the position of O89 and the reaction can reach the saddle point 02 when the distance between these two atoms is reduced to 2.083 Å. After that, the distance between H37 and O89 in H2O keeps the trend of decreasing and eventually connects to each other (1.069 Å) after continuous optimization of the intermediate states. Intriguingly, the structural difference between any of the intermediate states (01, 02, 03 or 04) and the initial state 00 is only reflected in the bond length, as shown in Table 4. It also demonstrates that the passivation of dangling bond defect by H2O is more stable than that by hydroxyl group for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 1. Figure 5B shows the variation of the energy fluctuation during the whole reaction process, it can be seen that the forward reaction barrier of this reaction is 0.29 eV. In addition, the energy of the final state 00 is nearly 0.26 eV higher than that of the initial state 00, which again proves the stability of passivating Pb1 defect with H2O.

FIGURE 5. (A) The schematic diagram of the reaction between Pb1 defect and H2O. (B) The variation of the energy with different reaction coordinates for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 1.

TABLE 4. Changes in bond length for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 1.

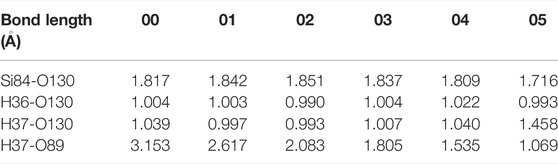

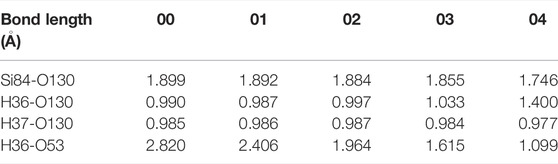

Next, for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 2, we conventionally choose an oxygen atom (O53) that is relatively far away (2.820 Å) from the hydrogen atom (H36) in H2O and combine with it as the final state 04. In this reaction, the distance between O53 and H36 in H2O gradually decreases, and the saddle point 01 can be attained when the distance between these two atoms is minished to 2.406 Å, as shown in Figure 6A. Since then, the position of H36 is getting closer and closer to that of O53, and finally bonds with it in a form of proton (1.099 Å), thus reaching the final state 04 of the reaction. As in the previous case, the structural difference between any of the intermediate states (01, 02 or 03) and the initial state 00 is only embodied in the bond length, as shown in Table 5.

FIGURE 6. (A) The schematic diagram of the reaction between Pb1 defect and H2O. (B) The variation of the energy with different reaction coordinates for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 2.

TABLE 5. Changes in bond length for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 2.

Figure 6B displays the change of the energy with different reaction coordinates in the interaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 2. It can be seen that the forward reaction barrier of this reaction is only 0.02 eV. What’s more, the energy of the final state 04 has a smaller raise (∼0.08 eV) compared with that of the intermediate state 03, which verifies that the passivation of dangling bond defect by H2O is more stable than that by hydroxyl group for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 2.

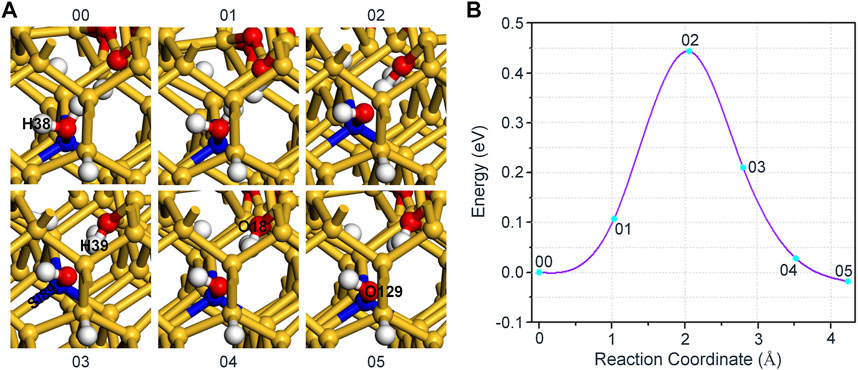

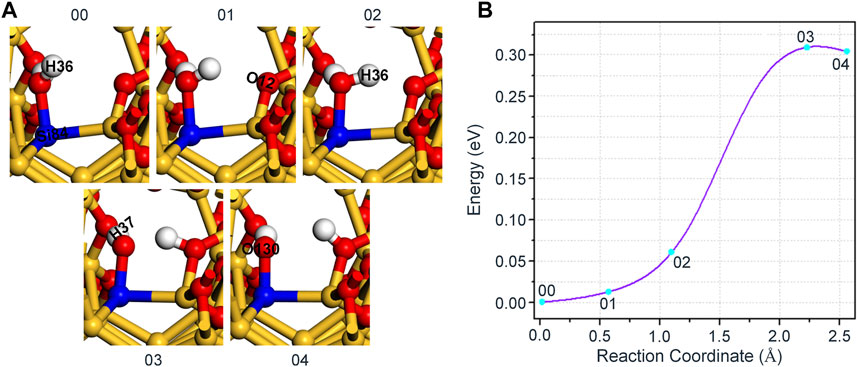

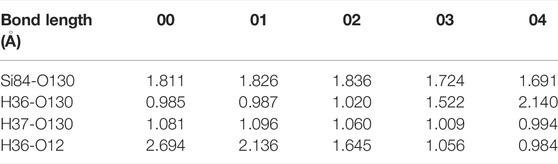

Finally, we simulated and analyzed the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 3. Based on the above experience in constructing the final state, we still opt for an oxygen atom (O12) that is relatively far away (2.694 Å) from the hydrogen atom (H36) in H2O and combine with it as the final state 04. As shown in Figure 7A, the movement of H36 in H2O towards O12 leads to an increase in the bond length of O130 and H36. As the reaction proceeds, H36 in H2O firstly breaks with O130 attached to it, and then combines with O12 in a form of proton (1.056 Å), thereby reaching the saddle point 03 of the reaction. Afterwards, with the continuous optimization of the positions about the hydroxyl group connected to Si84 and the proton bonded to O12, the system finally reaches the final state 04. The variation of interatomic bond length around the defect in the whole reaction is shown in Table 6.

FIGURE 7. (A) The schematic diagram of the reaction between Pb1 defect and H2O. (B) The variation of the energy with different reaction coordinates for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 3.

TABLE 6. Changes in bond length for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 3.

In Figure 7B, we can see from the energy change curve that the forward reaction barrier of this reaction is 0.31 eV. Besides, the energy of the final state 04 is only inferior to that of the saddle point 03, which is 0.30 eV higher than that of the initial state 00. It further indicates that the passivation of dangling bond defect by H2O is more stable than that by hydroxyl group for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect with AOD configuration at random position 3.

In summary, we have systematically simulated and analyzed the interaction of H2O and interface defects in a-SiO2/Si(100) by using the first-principles method. The reaction barrier is about 0.4 ∼ 0.7 eV for the reaction of H2O and Pb0 defect, and the hydroxyl group is more liable to passivate dangling bond defect than H2O. Conversely, for the reaction of H2O and Pb1 defect, the passivation of dangling bond defect by H2O is more stable than that by hydroxyl group, which can be attributed to the position of Pb1 defect closer to the interface than that of Pb0 defect. And there has been a precedent that high-pressure H2O vapor heating can passivate the a-SiO2/Si interface experimentally (Sakamoto and Sameshima, 2000). Our study offers a convictive theoretical guidance for the interaction of H2O and interface defects in a-SiO2/Si(100).

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

All authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work and approved it for publication.

This research is supported by the Science Challenge Project (Grant No. TZ2016003-1-105), Tianjin Natural Science Foundation (Grant No. 20JCZDJC00750), Tianjin Graduate Research and Innovation Project (Grant No. 2021YJSB015), and the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities, Nankai University (Grant Nos 63211107 and 63201182).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmats.2022.894097/full#supplementary-material

Batyrev, I. G., Tuttle, B., Fleetwood, D. M., Schrimpf, R. D., Tsetseris, L., and Pantelides, S. T. (2008). Reactions of Water Molecules in Silica-Based Network Glasses. Phys. Rev. Lett. 100 (10), 105503. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.100.105503

Blöchl, P. E. (1994). Projector Augmented-Wave Method. Phys. Rev. B 50 (24), 17953. doi:10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953

Blöchl, P. E., and Stathis, J. H. (1999). Hydrogen Electrochemistry and Stress-Induced Leakage Current in Silica. Phys. Rev. Lett. 83 (2), 372. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.83.372

Bourg, I. C., and Steefel, C. I. (2012). Molecular Dynamics Simulations of Water Structure and Diffusion in Silica Nanopores. J. Phys. Chem. C 116 (21), 11556–11564. doi:10.1021/jp301299a

Campbell, J. P., and Lenahan, P. M. (2002). Density of States of Pb1 Si/SiO2 Interface Trap Centers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 80 (11), 1945–1947. doi:10.1063/1.1461053

Chadi, D. J. (2001). Intrinsic and H-Induced Defects at Si-SiO2 Interfaces. Phys. Rev. B 64 (19), 195403. doi:10.1103/physrevb.64.195403

Gerardi, G. J., Poindexter, E. H., Caplan, P. J., and Johnson, N. M. (1986). Interface Traps and Pb Centers in Oxidized (100) Silicon Wafers. Appl. Phys. Lett. 49 (6), 348–350. doi:10.1063/1.97611

Griscom, D. L. (1991). Optical Properties and Structure of Defects in Silica Glass. J. Ceram. Soc. Jpn. 99 (1154), 923–942. doi:10.2109/jcersj.99.923

Hafner, J. (2008). Ab-initiosimulations of Materials Using VASP: Density-Functional Theory and beyond. J. Comput. Chem. 29 (13), 2044–2078. doi:10.1002/jcc.21057

Haneji, N., Vishnubhotla, L., and Ma, T. P. (1991). Possible Observation of Pb0 and Pb1 Centers at Irradiated (100)Si/SiO2 Interface from Electrical Measurements. Appl. Phys. Lett. 59 (26), 3416–3418. doi:10.1063/1.105693

Helms, C. R., and Poindexter, E. H. (1994). The Silicon-Silicon Dioxide System: Its Microstructure and Imperfections. Rep. Prog. Phys. 57 (8), 791–852. doi:10.1088/0034-4885/57/8/002

Henkelman, G., Uberuaga, B. P., and Jónsson, H. (2000). A Climbing Image Nudged Elastic Band Method for Finding Saddle Points and Minimum Energy Paths. J. Chem. Phys. 113 (22), 9901–9904. doi:10.1063/1.1329672

Kajihara, K., Kamioka, H., Hirano, M., Miura, T., Skuja, L., and Hosono, H. (2005). Nterstitial Oxygen Molecules in Amorphous SiO2. III. Measurements of Dissolution Kinetics, Diffusion Coefficient, and Solubility by Infrared Photoluminescence. J. Appl. Phys. 98 (1), 013529. doi:10.1063/1.1943506

Kato, K., Yamasaki, T., and Uda, T. (2006). Origin of Pb1 Center at SiO2/Si(100) Interface: First-Principles Calculations. Phys. Rev. B 73 (7), 073302. doi:10.1103/physrevb.73.073302

Kosowsky, S. D., Pershan, P. S., Krisch, K. S., Bevk, J., Green, M. L., Brasen, D., et al. (1997). Evidence of Annealing Effects on a High-Density Si/SiO2 Interfacial Layer. Appl. Phys. Lett. 70 (23), 3119–3121. doi:10.1063/1.119090

Kovačević, G., and Pivac, B. (2014). Structure, Defects, and Strain in Silicon-Silicon Oxide Interfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 115 (4), 043531. doi:10.1063/1.4862809

Lenahan, P. M., and Conley, J. F. (1998). What Can Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Tell Us about the Si/SiO2 System. J. Vac. Sci. Technol. B 16 (4), 2134–2153. doi:10.1116/1.590301

Li, J., Wu, J., Zhou, C., Han, B., Karwacki, E. J., Xiao, M., et al. (2009). On the Dissociative Chemisorption of Tris(dimethylamino)silane on Hydroxylated SiO2(001) Surface. J. Phys. Chem. C 113 (22), 9731–9736. doi:10.1021/jp900119b

Li, P., Chen, Z., Yao, P., Zhang, F., Wang, J., Song, Y., et al. (2019). First-Principles Study of Defects in Amorphous-SiO2/Si Interfaces. Appl. Surf. Sci. 483, 231–240. doi:10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.03.216

Li, P., Song, Y., and Zuo, X. (2019). Computational Study on Interfaces and Interface Defects of Amorphous Silica and Silicon. Phys. Status Solidi RRL 13 (3), 1800547. doi:10.1002/pssr.201800547

Lu, Z. H., Graham, M. J., Jiang, D. T., and Tan, K. H. (1993). SiO2/Si(100) Interface Studied by Al Kα x‐ray and Synchrotron Radiation Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Appl. Phys. Lett. 63 (21), 2941–2943. doi:10.1063/1.110279

Matsudo, T., Ohta, T., Yasuda, T., Nishizawa, M., Miyata, N., Yamasaki, S., et al. (2002). Observation of Oscillating Behavior in the Reflectance Difference Spectra of Oxidized Si(001) Surfaces. J. Appl. Phys. 91 (6), 3637–3643. doi:10.1063/1.1452764

McLean, F. B. (1980). A Framework for Understanding Radiation-Induced Interface States in SiO2 MOS Structures. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 27 (6), 1651–1657. doi:10.1109/tns.1980.4331084

Michalske, T. A., and Freiman, S. W. (1983). A Molecular Mechanism for Stress Corrosion in Vitreous Silica. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 66 (4), 284–288. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1983.tb15715.x

Monkhorst, H. J., and Pack, J. D. (1976). Special Points for Brillouin-Zone Integrations. Phys. Rev. B 13 (12), 5188–5192. doi:10.1103/physrevb.13.5188

Pamungkas, M. A., Joe, M., Kim, B.-H., and Lee, K.-R. (2011). Reactive Molecular Dynamics Simulation of Early Stage of Dry Oxidation of Si(100) Surface. J. Appl. Phys. 110 (5), 053513. doi:10.1063/1.3632968

Pantelides, S. T., Tsetseris, L., Rashkeev, S. N., Zhou, X. J., Fleetwood, D. M., and Schrimpf, R. D. (2007). Hydrogen in MOSFETs-A Primary Agent of Reliability Issues. Microelectron. Reliab. 47 (6), 903–911. doi:10.1016/j.microrel.2006.10.011

Parr, R. G. (1983). Density Functional Theory. Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 34 (1), 631–656. doi:10.1146/annurev.pc.34.100183.003215

Perdew, J. P., Burke, K., and Ernzerhof, M. (1996). Generalized Gradient Approximation Made Simple. Phys. Rev. Lett. 77 (18), 3865–3868. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.77.3865

Perez-Beltran, S., Ramírez-Caballero, G. E., and Balbuena, P. B. (2015). First-Principles Calculations of Lithiation of a Hydroxylated Surface of Amorphous Silicon Dioxide. J. Phys. Chem. C 119 (29), 16424–16431. doi:10.1021/acs.jpcc.5b02992

Pfeffer, R., and Ohring, M. (1981). Network Oxygen Exchange during Water Diffusion in SiO2. J. Appl. Phys. 52 (2), 777–784. doi:10.1063/1.328762

Poindexter, E. H., Caplan, P. J., Deal, B. E., and Razouk, R. R. (1981). Interface States and Electron Spin Resonance Centers in Thermally Oxidized (111) and (100) Silicon Wafers. J. Appl. Phys. 52 (2), 879–884. doi:10.1063/1.328771

Rochet, F., Poncey, C., Dufour, G., Roulet, H., Guillot, C., and Sirotti, F. (1997). Suboxides at the Si/SiO2 Interface: A Si2p Core Level Study with Synchrotron Radiation. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 216, 148–155. doi:10.1016/s0022-3093(97)00181-6

Sakamoto, K., and Sameshima, T. (2000). Passivation of SiO2/Si Interfaces Using High-Pressure-H2O-Vapor Heating. Jpn. J. Appl. Phys. 39, 2492–2496. doi:10.1143/jjap.39.2492

Schwank, J. R., Shaneyfelt, M. R., Fleetwood, D. M., Felix, J. A., Dodd, P. E., Paillet, P., et al. (2008). Radiation Effects in MOS Oxides. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 55 (4), 1833–1853. doi:10.1109/tns.2008.2001040

Sheikholeslam, S. A., Manzano, H., Grecu, C., and Ivanov, A. (2016). Reduced Hydrogen Diffusion in Strained Amorphous SiO2: Understanding Ageing in MOSFET Devices. J. Mat. Chem. C 4 (34), 8104–8110. doi:10.1039/c6tc02647h

Sheppard, D., Xiao, P., Chemelewski, W., Johnson, D. D., and Henkelman, G. (2012). A Generalized Solid-State Nudged Elastic Band Method. J. Chem. Phys. 136 (7), 074103. doi:10.1063/1.3684549

Stesmans, A., and Afanas’ev, V. V. (1998). Electron Spin Resonance Features of Interface Defects in Thermal (100)Si/SiO2. J. Appl. Phys. 83 (5), 2449–2457. doi:10.1063/1.367005

Stesmans, A. (1996). Passivation of Pb0 and Pb1 Interface Defects in Thermal (100) Si/SiO2 with Molecular Hydrogen. Appl. Phys. Lett. 68 (15), 2076–2078. doi:10.1063/1.116308

Stirling, A., Pasquarello, A., Charlier, J.-C., and Car, R. (2000). Dangling Bond Defects at Si-SiO2 Interfaces: Atomic Structure of the Pb1 Center. Phys. Rev. Lett. 85 (13), 2773–2776. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.85.2773

Takahashi, J. I., Machida, K., Shimoyama, N., and Minegishi, K. (1993). Water Trapping of Point Defects in Interlayer SiO2 Films and its Contribution to the Reduction of Hot-Carrier Degradation. Appl. Phys. Lett. 62 (19), 2365–2366. doi:10.1063/1.109391

Thoan, N. H., Keunen, K., Afanas’ev, V. V., and Stesmans, A. (2011). Interface State Energy Distribution and Pb Defects at Si(110)/SiO2 Interfaces: Comparison to (111) and (100) Silicon Orientations. J. Appl. Phys. 109 (1), 013710. doi:10.1063/1.3527909

Tomozawa, M. (1985). Concentration Dependence of the Diffusion Coefficient of Water in SiO2 Glass. J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 68 (9), C‐251-C‐252. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1985.tb15804.x

Watanabe, H., Kato, K., Uda, T., Fujita, K., Ichikawa, M., Kawamura, T., et al. (1998). Kinetics of Initial Layer-By-Layer Oxidation of Si(001) Surfaces. Phys. Rev. Lett. 80 (2), 345–348. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.80.345

Yamasaki, T., Kato, K., and Uda, T. (2003). Oxidation of the Si(001) Surface: Lateral Growth and Formation of Pb0 Centers. Phys. Rev. Lett. 91 (14), 146102. doi:10.1103/physrevlett.91.146102

Keywords: first-principles calculation, Pb0 and Pb1 defect, reaction barrier, hydroxyl group and H2O, passivation

Citation: Zhang W, Zhang J, Liu Y, Zhu H, Yao P, Liu X, Liu X and Zuo X (2022) First-Principles Study on the Interaction of H2O and Interface Defects in A-SiO2/Si(100). Front. Mater. 9:894097. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2022.894097

Received: 11 March 2022; Accepted: 20 April 2022;

Published: 05 May 2022.

Edited by:

Vincent G. Harris, Northeastern University, United StatesReviewed by:

Piero Ugliengo, University of Turin, ItalyCopyright © 2022 Zhang, Zhang, Liu, Zhu, Yao, Liu, Liu and Zuo. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Xu Zuo, eHp1b0BuYW5rYWkuZWR1LmNu

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.