94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mater., 13 October 2021

Sec. Polymeric and Composite Materials

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2021.719833

An MoSi2–borosilicate glass coating with high emissivity and oxidation resistance was prepared on the surface of the fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel composite by the slurry method combined with the embedding sintering method under the micro-oxygen atmosphere. The microstructure and phase composition of the coatings with different MoSi2 contents before and after static oxidation were investigated. This composite material has both excellent radiating properties and outstanding oxidation resistance. The total emissivity values of the as-prepared coatings are all above 0.8450 in the wavelength of 300∼2,500 nm. Meanwhile, the as-prepared M40 coating also has superior thermal endurance after the isothermal oxidation of 1,200°C for 180 min with only 0.27% weight loss, which contributes to the appropriate viscosity of the binder to relieve thermal stress defects. This material has broad application prospects in thermal protection.

With the development of hypersonic aircraft and spacecraft, the external surfaces of vehicles experience an intense aerodynamic heating load, which will lead to the failure of internal structures (Levchenko et al., 2018). Therefore, the vehicles must be protected by a lightweight and stable thermal protection, which possesses high emissivity, anti-oxidation coating, and low thermal conductivity insulation (Shao et al., 2019). For spacecraft, thermal radiation is considered to be the most important way to dissipate heat, while thermal conduction and thermal convection are negligible under a vacuum environment (Sun et al., 2017). Thus, high emissivity coating has drawn more and more attention in the aerospace thermal protection system. The substrate material plays a vital role in this system including mechanical load-bearing, anti-erosion, and further isolated heat. Therefore, the choice of the substrate directly affects the efficient and stable service of the thermal protection system. At present, the thermal insulation materials for thermal protection systems mostly focus on high-temperature ceramic matrix composites (Cui et al., 2018; Savino et al., 2018; Grigoriev et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2021), carbon/carbon composites (Paul et al., 2017; Du et al., 2018a; Liu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2020a), etc. These thermal insulation materials function to protect the internal structure of aircraft, which also exhibit deficiencies such as high thermal conductivity, insufficient temperature resistance, and high brittleness. To meet the requirements of complex space environments, it is of great significance to develop a new thermal insulation material with low thermal conductivity, low density, excellent temperature resistance, and high mechanical strength.

Aerogel, a kind of nano-porous material, exhibits excellent properties such as low density (Zhu et al., 2020), high specific area (Wu et al., 2017), high porosity (Li et al., 2019a; Zhao et al., 2020), and low thermal conductivity (Su et al., 2020), which receives great attention, becoming one of the most potential materials for the high-temperature thermal insulator in a thermal protection system. However, traditional SiO2 aerogel cannot maintain its thermal stability in the long-time working temperature exceeding 800°C (Cai et al., 2020). Though Al2O3 aerogel shows improved thermal resistance, the metastable alumina phase converts to stable α-Al2O3 after temperature over 1,050°C and contributes to the collapse of the nano-porous structure and a considerable loss of surface area (Yang et al., 2020). Compared with SiO2 aerogel and Al2O3 aerogel, carbon aerogel has the highest thermal stability and can maintain a mesoporous structure even over 2000°C in an inert atmosphere (Lee and Park, 2020). However, carbon aerogel has insufficient mechanical strength, which is fragile and easily collapses (Li et al., 2019b). Reinforcing the carbon-based aerogel with fibers is an effective way to overcome the problems of brittleness and liner shrinkage (Feng et al., 2011). Moreover, carbon aerogel will be oxidized above 500°C in an aerobic environment. Therefore, high emissivity and anti-oxidation coating are essential for carbon-based aerogel (Li et al., 2019b), which can protect the substrate from oxygen erosion and plays the role of radiating surface heat.

Generally, high emissivity and anti-oxidation coating are mainly composed of the radiation agent (Du et al., 2018b) and binder agent (Shao et al., 2017a). The radiation agent plays the role of absorbing and reradiating thermal energy. And the binder agent, which is generally of the amorphous phase, can connect with the substrate and adjust the thermal expansion coefficient and improve the antioxidant performance. The intermetallic silicide MoSi2 is a typical radiation agent (Du et al., 2016; Li et al., 2018) with high melting point (2020°C), low density (6.24 g/cm3), and excellent oxidation resistance (Shao et al., 2017b). MoSi2 forms a dense SiO2 layer during high-temperature oxidation, which prevents oxygen from permeating into the substrate (Liu et al., 2020; Xiao et al., 2020). Wang et al. (2019a) prepared an MoSi2-based oxidation protective coating on carbon/carbon composites by combining pack cementation and supersonic atmospheric plasma spraying techniques. The weight loss of MoSi2-based coating at 900°C for 15 h, 1,200°C for 25 h, and 1,500°C for 50 h was 20.57, 4.24, and 2.61%, respectively. Borosilicate glass (BSG) is an excellent binder agent with an amorphous structure. Its low thermal expansion coefficient can effectively adapt to the substrate, which also shows appropriate fluidity and viscosity under high-temperature melting conditions to heal the holes and cracks due to thermal stress (Guan et al., 2020). Wu et al. (2020) prepared scale-like MoSi2–borosilicate coatings with MoSi2 as the emittance agent, flake-fused quartz as coarse fillers, and silica sol as a dispersive medium of coating slurry on rigid mullite fibrous ceramics. The scale-like coatings with the crack network went through 25 thermal cycles between 1,500°C and room temperature without peeling and spalling because of the bonding effect of borosilicate glass.

In this work, C/SiO2 aerogel is selected as the thermal insulation matrix material, and the fiber is used to improve the mechanical properties of the substrate. The fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel composition was prepared by precursor conversion, supercritical drying, and subsequent high-temperature treatment. The borosilicate glass selected as a binder agent was prepared by high-temperature melting combined with water quenching. A gradient coating was designed to alleviate the thermal stress defects caused by thermal expansion mismatch, which was prepared using slurry brushing and rapid sintering methods. The microstructure, radiative property, and static oxidation resistance were investigated in detail.

The C/SiO2 gel was synthesized by using catechol (C), formaldehyde (F), and 3-aminopropyltriethoxysilane (APTES) as precursors and ethanol (EtOH) as the solvent. Catechol and formaldehyde are used as the carbon sources, and APTES not only functions as a silica source but also plays a part as a gelation agent. Firstly, a mixture is prepared with a molar ratio of C: F: EtOH = 1:2:15, stirring for about 60 min at room temperature. Subsequently, the desired amounts of APTES (molar ratio of APTES: C = 0.75:1) were dropped into a clear solution. After stirring for 10 min at room temperature, the carbon fiber felt was impregnated with the sol prepared above. After gelation, aging, and solvent exchange, the fiber felt/wet gel was dried under supercritical CO2 conditions (315 K, 10 MPa) to produce the fiber-reinforced CF/SiO2 precursor aerogel composite. The precursor aerogel composite was put into the furnace at a rate of 3 K/min to 1073 K under the protection of the argon atmosphere for 150 min. After cooling to room temperature, the composite was heat-treated again at a rate of 3 K/min to 1473 K in a flow of high-purity argon for 180 min.

Fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel composites (ρ = 0.31 g/cm3) were used as the substrates. The borosilicate glass was prepared by high-temperature melting and subsequent water quenching methods, which has been reported in our previous work (Shao et al., 2015). The raw materials including MoSi2, borosilicate glass powder, and SiB6 were weighed in the mass ratio 5:44:1. The raw materials, ethanol, and carboxymethylcellulose (CMC) aqueous solution (1 wt%) were mixed in nylon containers and ball-milled by a planetary mill at a rotation speed of 280 rpm for 2 h. The mass ratio of the powders, ethanol, and CMC aqueous solution in the outer coating and inner coating was 6.11:4:1 and 3.33:4:1, respectively. The obtained slurry was uniformly coated on the surface of fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel by wool brush and dried in a drying oven at 373 K for 12 h. Then, the as-coated samples were embedded in graphite powder and put into the furnace at 1473 K for 30 min in air. Three coatings were obtained by changing the contents of MoSi2 in the outer layer (30, 40, and 50%), namely, M30, M40, and M50, respectively.

Static oxidation tests were carried out in the air in an electrical furnace in order to obtain isothermal oxidation behavior of the multilayer MoSi2–borosilicate glass–coated fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel at 1473 K. The samples were directly placed inside a furnace at 1473 K for a certain time. Subsequently, they were taken out and cooled at room temperature. After weighing the samples’ mass, they were put into the furnace again for oxidation tests. The mass loss ∆m% was calculated using the following equation:

where

The room temperature spectral reflectance of the coatings was measured by using a UV-Vis-NIR spectrophotometer in the wavelength range of 0.3–2.5 μm, with BaSO4 as the reflectance sample. The total emissivity can be calculated according to the following equations:

where λ is the wavelength, R(λ) is the reflectance, PB(λ) is given by Planck’s law, C1 = 3.743 × 10−16 Wm2, and C2 = 1.4387 × 10−2 mK.

The phase composition of glass and the coating surface were examined using a Rigaku Miniflex X-ray diffractometer (XRD) with Cu-Kα radiation (λ= 0.15406 nm). The microstructure of the composites was surveyed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM, Hitachi S-4800, Japan). X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) measurements were performed on a Thermo K-Alpha spectrometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc., MA). Thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out with a thermogravimetric analyzer (STA449F3, Netsch, Germany) under constant nitrogen flow at a heating rate of 10°C/min to 1,400°C. A Nexus 670 Fourier infrared spectrometer (FT-IR spectrometer, Thermo Nicolet Corporation, United States) was employed to analyze the chemical bonds in the aerogel composite and borosilicate glass.

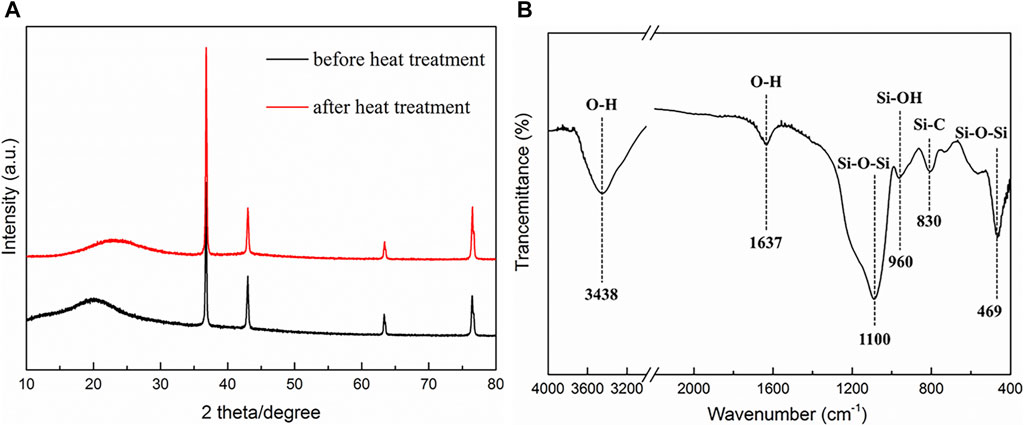

The fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel composite exhibits low density (0.31 g/cm3) and low thermal conductivity (0.044 W/m*k), which is suitable for high-efficiency thermal insulation uses. The XRD patterns and FT-IR spectrum are shown in Figure 1. The XRD spectrum contains a broad bump at 22° after heat treatment. This is because the organic groups in the precursor aerogel are decomposed to generate H2O, CO2, and other gases in high-temperature environments, which makes the composite present an amorphous structure. In particular, peaks at 36°, 43°, 63°, and 76° assign to the aluminum phase, which attributes to the fact that the sample tray is made of aluminum. As we can see in the FT-IR spectrum, the absorption peaks at the wavenumber of 3,438 cm−1 and 1,637 cm−1 come from the water molecules adsorbed inside the aerogel structure. The vibration at 1,100 cm−1 belongs to the Si-O-Si asymmetrical stretching vibration peak, and the vibration at 469 cm−1 assigns to the Si-O-Si bending vibration peak. Moreover, the appearance of the Si-C absorption peak at the wavenumber of 830 cm−1 shows that the aerogel structure changes from organic to inorganic after heat treatment.

FIGURE 1. (A) XRD patterns of the fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel composite before and after heat treatment. (B) FT-IR spectrum of the fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel composite.

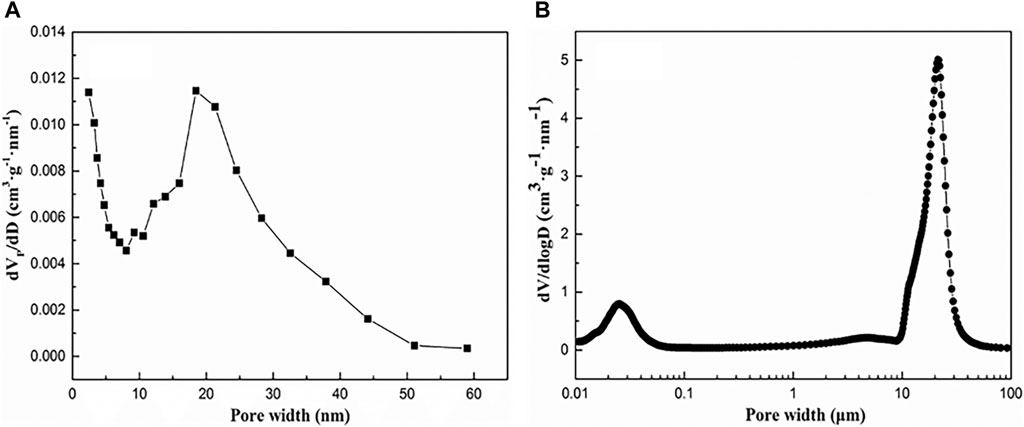

Figure 2 presents that the particle and the pore structure distribution of C/SiO2 aerogel are relatively uniform with a three-dimensional network structure after heat treatment. Aerogel particles are attached to the surface of carbon fibers through physical adsorption. The pore size distribution of the fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel composite is shown in Figure 3. The average pore size of the composite is 18.46 nm and mainly distributed between 15 and 25 nm. The Brunauer–Emmett–Teller (BET) test has limitations, so the result of the mercury intrusion method is shown in Figure 3B. The composite presents a macro-porous structure, and its pore size is distributed between 10 and 30 μm, which corresponds to the characteristic of the fiber. The TG curve of the fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel composite in the argon environment from room temperature to 1,200°C is presented in Figure 4. The composite has excellent thermal stability with a weight loss of 1.89% at 1,200°C, which is suitable for use as a high-efficiency insulation material.

FIGURE 3. Pore size distributions of the fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel composite using the (A) BJH method and (B) mercury intrusion method.

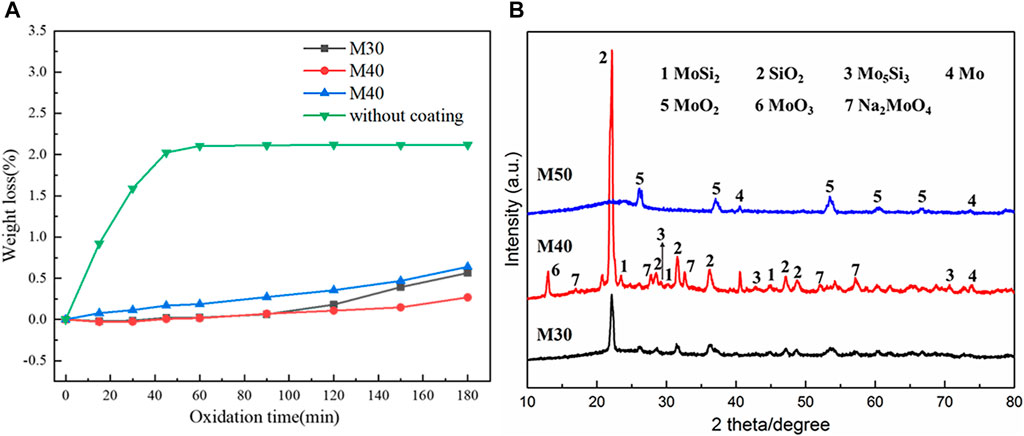

The component proportion of three coatings is shown in Table 1. To analyze the phase of the coating surface, XRD patterns are presented in Figure 5. A broad peak appears near 22° due to the presence of the glass phase with an amorphous structure. With the increase of MoSi2 content in the original component, the intensity of the MoSi2 diffraction peak in the spectrum also increases synchronously. In addition to the oxidation of MoSi2, the formation of the SiO2 phase also resulted from the cooling of the borosilicate glass component. Mo5Si3, Mo, MoO2, and MoO3 phases are identified in the coating because of the oxidation of the radiation agent MoSi2. The relevant chemical reaction formula is as follows:

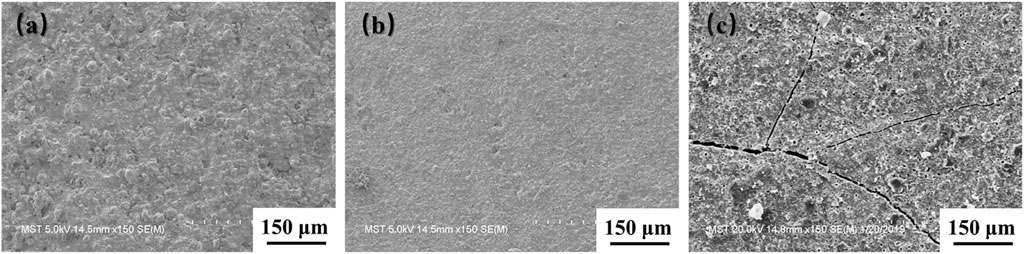

Figure 6 displays the surface SEM images of coatings with different contents of MoSi2. The M30 coating surface presents a rough morphology, while the M50 coating exhibits visibly spreading cracks. In addition to the mismatch of thermal expansion coefficients (Wang et al., 2019b), the formation of cracks is also due to the volume effect of the SiO2 crystal transformation. Comparing the SEM images of M30 and M50 coatings, the surface of the M40 coating is relatively flat and dense and has no obvious thermal stress defects. The M40 coating contains appropriate content of borosilicate glass, which provides suitable fluidity during the preparation process and effectively alleviates thermal stress defects.

FIGURE 6. Surface SEM images of the coatings with different contents of MoSi2: (A) M30; (B) M40; (C) M50.

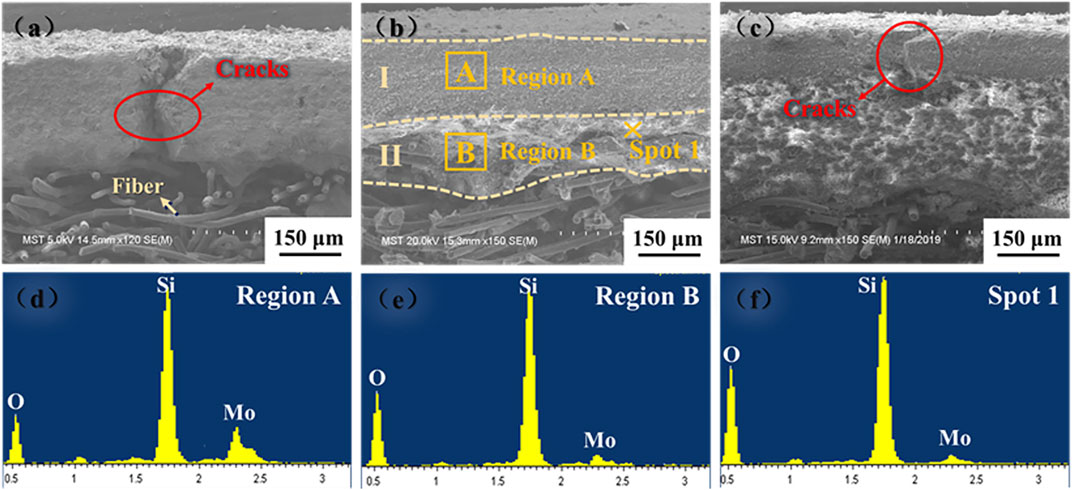

Figure 7 presents that coatings show a gradient structure. From the further analysis of the EDX spectrum, the content of MoSi2 presents a decreasing trend from top to bottom, which relieves the mismatch of thermal expansion coefficients between the coatings and the substrate. The M40 coating has a thickness of 350 μm, mainly consisting of two parts: the surface coating layer (zone Ⅰ) of 190 μm and the interfacial transition layer (zone Ⅱ) of 160 μm. It can be clearly observed that the M40 coating has an excellent combination with the substrate and no obvious cracks are discovered. Compared with the M40 coating, cracks with different sizes form on the section of M30- and M50-coated samples, which may result in the failure of the sample during use.

FIGURE 7. Sectional SEM images of the coatings with different contents of MoSi2: (A) M30; (B) M40; (C) M50; (D–F) EDX analyses of the coatings.

Figure 8 reveals the emissivity curves of coatings with different contents of MoSi2. The emissivity values gradually increase in the wavelength range of 300–800 nm and reduce in the wavelength range of 801–2,500 nm. The M30 and M40 coatings exhibit higher emissivity than the M50 coating and exceed 0.80 in the wavelength range of 350–2,500 nm. Table 2 shows the calculated total emissivity values in all kinds of wavelength ranges. According to Wien’s displacement law, λmax = b/T, with b = 2.898 × 10−3 m K; as temperature increases, the maximum spectral emissive power shifts to smaller wavelengths. Therefore, when the temperature is in the range of 1,473–2273 K, the largest radiation wavelength corresponds to the range of 1,270–1967 nm. In this range of wavelengths, the MoSi2–borosilicate glass coatings exhibit a higher emissivity than 0.8, and the total emissivity of M30 and M40 coatings exceeds 0.85.

It can be seen from Figure 9A that fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel without coating basically oxidized and failed at 60 min, while other coated samples present great oxidation resistance. Especially, the M40 coating has the mass loss of only 0.27%. The M40 coating has suitable viscosity because of the appropriate component of binder, which can bridge defects and block oxygen diffusion channels. However, only the static oxidation test is incapable of deciding the strength of oxidation resistance. The morphology of coating after oxidation and interface between the coating and the substrate still needs further investigation.

FIGURE 9. Isothermal oxidation at 1,200°C for 180 min in air. (A) Mass loss curves of the coatings. (B) XRD patterns of the coatings with different contents of MoSi2.

The XRD pattern of coatings after isothermal static oxidation at 1,200°C for 180 min is demonstrated in Figure 9B. Compared with the original components of coatings before oxidation, the diffraction peak of MoSi2 is significantly reduced, while the diffraction of crystalline SiO2 is enhanced. The oxidation of MoSi2 forms volatile MoO3 and crystalline SiO2. Comparing the phase composition of the coatings with different MoSi2 contents after oxidation, the amorphous nature of glass near 22° can be observed in all samples, indicating the coating surfaces include the borosilicate glass. Especially, the surface of M40 and M50 coatings has more content of borosilicate glass. Moreover, Mo, MoO2, Mo5Si3, and MoO3 are supposed to form under different partial pressure of oxygen.

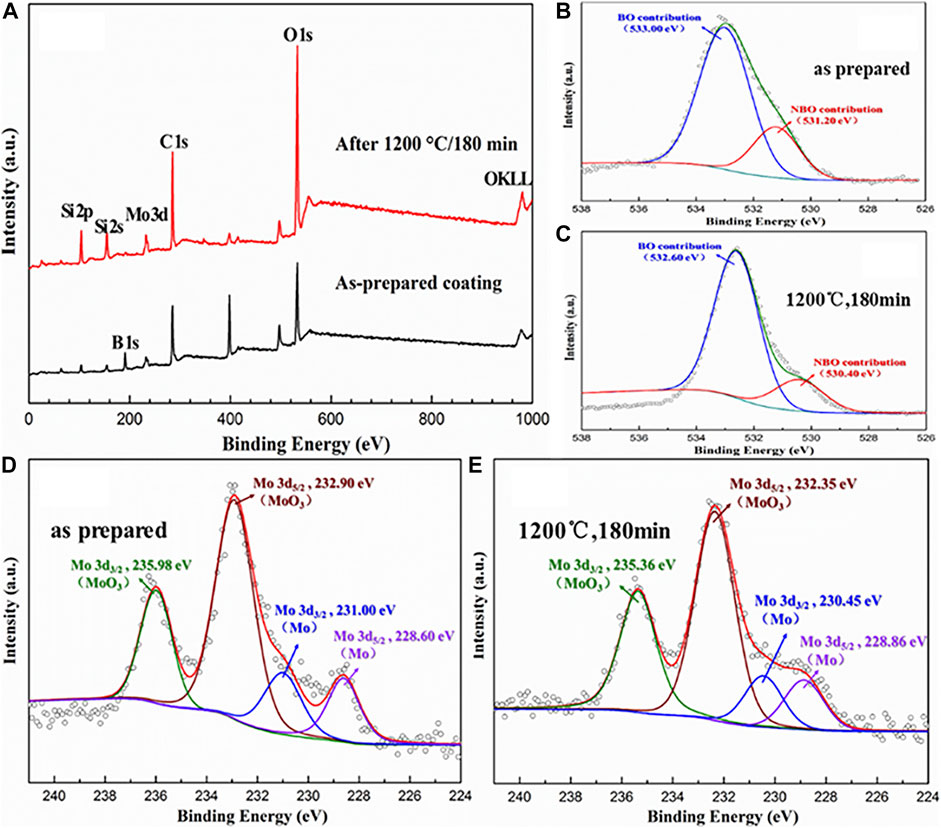

As shown in Figure 10A, O1s, Mo3d, B1s, Si2s, and Si2p peaks exist on the surface of coating before oxidation. After isothermal oxidation for 180 min, the intensity of the O1s and Mo3d peaks increased significantly. It is well known that XPS is a useful tool for directly measuring relatively bridging oxygen (BO) and non-bridging oxygen (NBO) concentrations (Sossaman and Perepezko, 2015). It can be seen from Figure 10B that a BO atom contains two bands with energies at 533.00 eV, while NBO atoms possess a single bond and a partial negative charge with the binding energy at 531.20 eV. Similarly, Figure 10C displays the O1s spectrum can be described by two components with binding energies at 532.60 eV (BO) and 530.40 eV (NBO) after oxidation. By calculating the peak area, the NBO concentration of the oxidized layer (19.84%) is reduced by 4.67% compared to that of the original layer (24.51%). It presents crystallization of SiO2, volatilization of B2O3, and an increase in viscosity during the oxidation test, which corresponds to the result of XRD. Figures 10D,E present high-resolution core-level XPS spectra of the Mo3d peak of the as-prepared coating and the coating after oxidation at 1,200°C for 180 min. The binding energies of Mo3d3/2 and Mo3d5/2 for the as-prepared coating are 235.98 and 28.1 eV, respectively. After oxidation at 1,200°C for 180 min, the coating presented Mo3d3/2 and Mo3d5/2 values of 235.36 and 232.35 eV, respectively, which are a characteristic of MoO3 (Sun et al., 2020). In particular, the peaks of Mo3d3/2 at 231.00 eV before oxidation and 230.45 eV after oxidation and the peaks of Mo3d5/2 at 228.60 eV before oxidation and 228.86 eV after oxidation are all derived from Mo, which has a good match with the XRD result. However, the diffraction peak of MoO2 shown in the XRD was not detected in XPS. It may be because the XRD penetration depth is within tens of micrometers related to the tested materials, while the photoelectron escape depth of the tested material is only approximately 10 nm. These results indicate that MoO2 mainly formed at a depth of tens of micrometers, which is consistent with the fact that MoO2 formed under low oxygen partial pressure.

FIGURE 10. XPS pattern of the M40 coating before and after isothermal oxidation. (A) Wide scan XPS spectra; (B) O1s of the prepared coating; (C) O1s of the coating after oxidation at 1,200°C for 180 min; (D) Mo3d of the prepared coating; (E) core-level XPS spectra of Mo3d of the coating after oxidation at 1,200°C for 180 min.

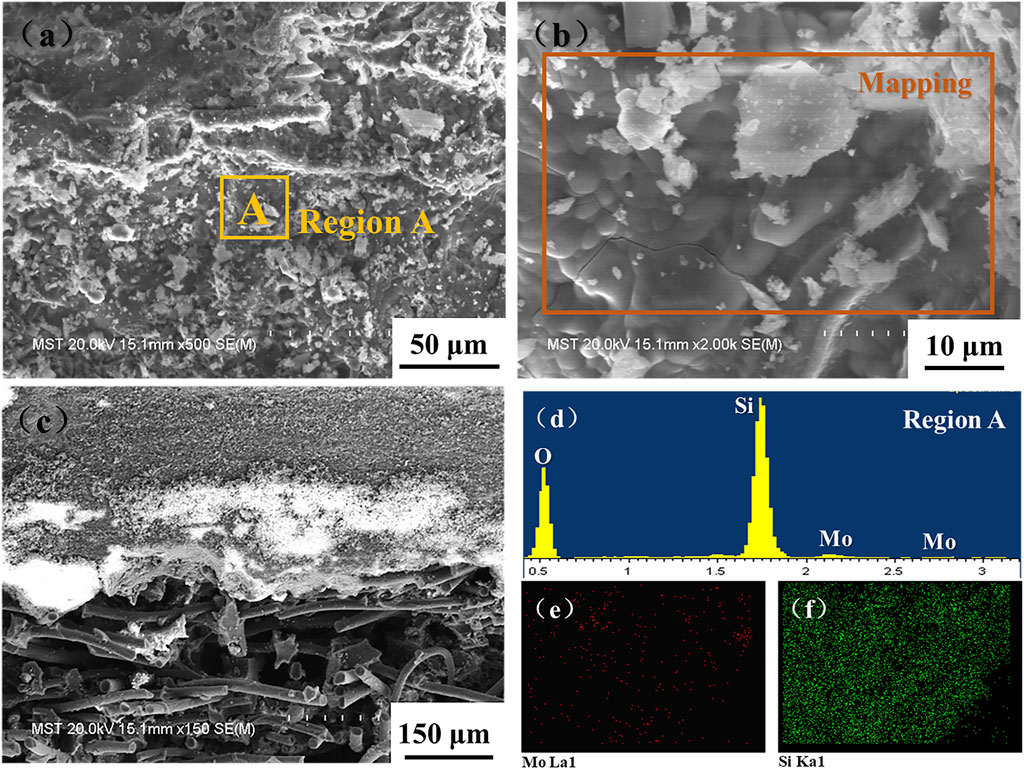

The surface and cross-sectional SEM images of the M40 coating oxidized at 1,200°C for 180 min are shown in Figure 11. Compared to the original coating surface, it can be seen from Figure 11A that the surface of the coating has no obvious pores and cracks after oxidation. It is mainly because the volatile products are blocked and then “covered” by borosilicate glass during high-temperature oxidation, resulting in unevenness morphology. According to EDX analysis (Figure 11D, E, F), the coating surface exhibits a large amount of elements Si and O, which indicates that amorphous glass formed during oxidation plays roles of healing pores and cracks, while the element of Mo is rare on the coating surface, which is basically consistent with the XRD result.

FIGURE 11. SEM images of the coatings after isothermal oxidation at 1,200°C for 180 min in air: (A, B) surface; (C) section; (D) EDX analyses; (E, F) EDX mapping analysis.

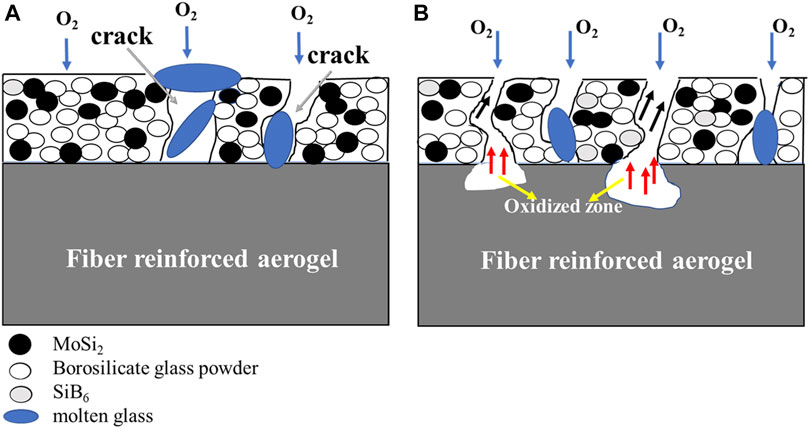

To explain the oxidation mechanisms of the MoSi2–borosilicate glass–coated fiber-reinforced aerogel samples during isothermal oxidation, a schematic diagram is displayed in Figure 12. During the oxidation process, the thermal stress due to the mismatch of coefficients of thermal expansion between the coating and the substrate would lead to the cracking of the coating (Chu et al., 2015). However, the borosilicate glass exhibits appropriate fluidity and viscosity at high temperature, which could seal the penetrated cracks in the coating, as presented in Figure 12A. With the increasing time of oxidation, the cracks of coating are getting larger and borosilicate glass consumes gradually. On the one hand, some oxygen diffuses to the MoSi2–borosilicate glass coating through cracks and then reacts with coating and releases some gases such as SiO and MoO3 (indicated by black arrows in Figure 12B). On the other hand, some oxygen diffuses to fiber-reinforced aerogel through penetrating cracks, resulting in the oxidation of the substrate and generating CO2 and CO gases (indicated by red arrows in Figure 12B). These gases would accumulate with the gases produced by the oxidation of coating, forming bubbles on the surface of the coating. At this time, if borosilicate glass still has good fluidity, it would cover the bubbles and form a “bulge” morphology, as shown in Figure 11B, whereas the bubbles would break and form pores due to the pressure of gases exceeding the surface tension of bubbles. And oxygen further diffuses to fiber-reinforced aerogel, resulting in the failure of samples (Li et al., 2020b).

FIGURE 12. Schematic diagram of possible oxidation mechanisms of the coated fiber-reinforced aerogel samples during isothermal oxidation. (A) oxidation early period; (B) oxidation later period.

This new thermal protection system is based on fiber-reinforced C/SiO2 aerogel as the matrix, and the slurry method combined with the embedding sintering method is used to prepare a gradient MoSi2–borosilicate coating on its surface. The coating has a thickness of 350 μm and exhibits a gradient structure: an outer surface coating of 190 μm and a transition coating of 160 μm inside. It also alleviates the thermal expansion coefficient mismatch of each part, which contributes to the acquisition of excellent high-temperature thermal stability. The M30 coating exhibits excellent radiation property with a total emissivity of 0.8722 in the wavelength range of 1,270∼1967 nm. The MoSi2–borosilicate coatings were oxidized at a static temperature of 1,200°C for 180 min, showing excellent thermal stability. The M40 coating has remarkable antioxidant property with a weight loss of only 0.27%. This is mainly attributed to the appropriate viscosity and fluidity of the binder, which not only has the function of bridging defects but also has the effect of blocking oxygen diffusion channels. This composite material has broad application prospects in thermal protection.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

TD performed the experiment. ZS contributed significantly to manuscript preparation. YD and ZS performed the data analyses. YZ helped perform the analysis with constructive discussions. SC contributed to the conception of the study.

This work was financially supported by the Key Research and Development Project of Jiangsu Province (BE2019734), the Major Program of Natural Science Fund in Colleges and Universities of Jiangsu Province (15KJA430005), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51702156, 81471183), the Postgraduate Research and Practice Innovation Program of Jiangsu Province (KYCX19_0837), and the General Program of Natural Science Fund in Colleges and Universities of Jiangsu Province (19KJB430023).

Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this paper are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of these programs.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors, and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Cai, H., Jiang, Y., Feng, J., Chen, Q., Zhang, S., Li, L., et al. (2020). Nanostructure Evolution of Silica Aerogels under Rapid Heating from 600 °C to 1300 °C via In-Situ TEM Observation. Ceramics Int. 46, 12489–12498. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.02.011

Chu, Y., Li, H., Luo, H., Li, L., and Qi, L. (2015). Oxidation protection of Carbon/carbon Composites by a Novel SiC Nanoribbon-Reinforced SiC-Si Ceramic Coating. Corrosion Sci. 92, 272–279. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2014.12.013

Cui, Y. J., Wang, B. L., Wang, K. F., and Li, J. E. (2018). Fracture Mechanics Analysis of Delamination Buckling of a Porous Ceramic Foam Coating from Elastic Substrates. Ceramics Int. 44, 17986–17991. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.06.276

Du, B., Hong, C., Zhang, X., Wang, J., and Qu, Q. (2018). Preparation and Mechanical Behaviors of SiOC-Modified Carbon-Bonded Carbon Fiber Composite with In-Situ Growth of Three-Dimensional SiC Nanowires. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 38, 2272–2278. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2018.01.002

Du, B., Hong, C., Zhou, S., Liu, C., and Zhang, X. (2016). Multi-composition Coating for Oxidation protection of Modified Carbon-Bonded Carbon Fiber Composites. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 36, 3303–3310. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2016.05.028

Du, B., Zhou, S., Zhang, X., Hong, C., and Qu, Q. (2018). Preparation of a High Spectral Emissivity TaSi2-Based Hybrid Coating on SiOC-Modified Carbon-Bonded Carbon Fiber Composite by a Flash Sintering Method. Surf. Coat. Technology 350, 146–153. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2018.07.019

Feng, J., Zhang, C., Feng, J., Jiang, Y., and Zhao, N. (2011). Carbon Aerogel Composites Prepared by Ambient Drying and Using Oxidized Polyacrylonitrile Fibers as Reinforcements. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 3, 4796–4803. doi:10.1021/am201287a

Grigoriev, S. N., Volosova, M. A., Vereschaka, A. A., Sitnikov, N. N., Milovich, F., Bublikov, J. I., et al. (2020). Properties of (Cr,Al,Si)N-(DLC-Si) Composite Coatings Deposited on a Cutting Ceramic Substrate. Ceramics Int. 46, 18241–18255. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2020.04.147

Guan, X., Xu, X., Hong, W., Tao, X., Wu, J., Du, H., et al. (2020). Double-layer Gradient MoSi2-Borosilicate Glass Coating Prepared by In-Situ Reaction Method with High Contact Damage Resistance and Interface Bonding Strength. J. Alloys Compounds 822, 153720. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.153720

Lee, J.-H., and Park, S.-J. (2020). Recent Advances in Preparations and Applications of Carbon Aerogels: A Review. Carbon 163, 1–18. doi:10.1016/j.carbon.2020.02.073

Levchenko, I., Xu, S., Teel, G., Mariotti, D., Walker, M. L. R., and Keidar, M. (2018). Publisher Correction: Recent Progress and Perspectives of Space Electric Propulsion Systems Based on Smart Nanomaterials. Nat. Commun. 9, 1–19. doi:10.1038/s41467-018-03818-4

Li, J., Zhang, Y., Wang, H., Fu, Y., Chen, G., and Xi, Z. (2020). Long-life Ablation Resistance ZrB2-SiC-TiSi2 Ceramic Coating for SiC Coated C/C Composites under Oxidizing Environments up to 2200 K. J. Alloys Compounds 824, 153934. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2020.153934

Li, M., Xia, K., Wei, W., Du, Q. B., Zhao, X. B., and Hu, J. (2020). Thermal Shock Behaviours of Atmospheric Plasma Sprayed NiCrAlY/Al2O3 - 20% TiO2 Gradient Coating on Cu-Be alloy. Surf. Eng. 36, 1113–1120. doi:10.1080/02670844.2020.1766866

Li, X., Feng, J., Jiang, Y., Li, L., and Feng, J. (2019). Preparation and Properties of PAN-Based Carbon Fiber-Reinforced SiCO Aerogel Composites. Ceramics Int. 45, 17064–17072. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.05.258

Li, X., Feng, J., Jiang, Y., Lin, H., and Feng, J. (2018). Preparation and Properties of TaSi2-MoSi2-ZrO2-Borosilicate Glass Coating on Porous SiCO Ceramic Composites for thermal protection. Ceramics Int. 44, 19143–19150. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.06.159

Li, Y., Wu, J., Wu, X., Suo, H., Shen, X., and Cui, S. (2019). Synthesis of Bulk BaTiO3 Aerogel and Characterization of Photocatalytic Properties. J. Sol-gel Sci. Technol. 90, 313–322. doi:10.1007/s10971-019-04948-x

Liu, F., Li, H., Gu, S., Yao, X., and Fu, Q. (2019). Ablation Behavior and thermal protection Performance of TaSi2 Coating for SiC Coated Carbon/carbon Composites. Ceramics Int. 45, 3256–3262. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.10.230

Liu, L., Zhang, H. Q., Lei, H., Li, H. Q., Gong, J., and Sun, C. (2020). Influence of Different Coating Structures on the Oxidation Resistance of MoSi2 Coatings. Ceramics Int. 46, 5993–5997. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.11.055

Paul, A., Rubio, V., Binner, J., Vaidhyanathan, B., Heaton, A., and Brown, P. (2017). Evaluation of the High Temperature Performance of HfB2UHTC Particulate Filled Cf/C Composites. Int. J. Appl. Ceram. Technol. 14, 344–353. doi:10.1111/ijac.12659

Savino, R., Criscuolo, L., Di Martino, G. D., and Mungiguerra, S. (2018). Aero-thermo-chemical Characterization of Ultra-high-temperature Ceramics for Aerospace Applications. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 38, 2937–2953. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2017.12.043

Shao, G., Lu, Y., Hanaor, D. A. H., Cui, S., Jiao, J., and Shen, X. (2019). Improved Oxidation Resistance of High Emissivity Coatings on Fibrous Ceramic for Reusable Space Systems. Corrosion Sci. 146, 233–246. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2018.11.006

Shao, G., Wang, Q., Wu, X., Jiao, C., Cui, S., Kong, Y., et al. (2017). Evolution of Microstructure and Radiative Property of Metal Silicide-Glass Hybrid Coating for Fibrous ZrO 2 Ceramic during High Temperature Oxidizing Atmosphere. Corrosion Sci. 126, 78–93. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2017.06.017

Shao, G., Wu, X., Cui, S., Shen, X., Lu, Y., Zhang, Q., et al. (2017). High Emissivity MoSi2-TaSi2-Borosilicate Glass Porous Coating for Fibrous ZrO2 Ceramic by a Rapid Sintering Method. J. Alloys Compounds 690, 63–71. doi:10.1016/j.jallcom.2016.08.073

Shao, G., Wu, X., Kong, Y., Cui, S., Shen, X., Jiao, C., et al. (2015). Thermal Shock Behavior and Infrared Radiation Property of Integrative Insulations Consisting of MoSi2/borosilicate Glass Coating and Fibrous ZrO2 Ceramic Substrate. Surf. Coat. Technology 270, 154–163. doi:10.1016/j.surfcoat.2015.03.008

Sossaman, T., and Perepezko, J. H. (2015). Viscosity Control of Borosilica by Fe Doping in Mo-Si-B Environmentally Resistant Alloys. Corrosion Sci. 98, 406–416. doi:10.1016/j.corsci.2015.05.051

Su, L., Wang, H., Niu, M., Dai, S., Cai, Z., Yang, B., et al. (2020). Anisotropic and Hierarchical SiC@SiO2 Nanowire Aerogel with Exceptional Stiffness and Stability for thermal Superinsulation. Sci. Adv. 6, eaay6689. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aay6689

Sun, F., Yao, Y., Li, X., Yu, P., Ding, G., and Zou, M. (2017). The Flow and Heat Transfer Characteristics of Superheated Steam in Offshore wells and Analysis of Superheated Steam Performance. Comput. Chem. Eng. 100, 80–93. doi:10.1016/j.compchemeng.2017.01.045

Sun, P., Lu, Q., Zhang, J., Xiao, T., Liu, W., Ma, J., et al. (2020). Mo-ion Doping Evoked Visible Light Response in TiO2 Nanocrystals for Highly-Efficient Removal of Benzene. Chem. Eng. J. 397, 125444. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2020.125444

Sun, S., Liu, Y., Ma, Z., Jiao, J., Jiao, C., and Yang, J. (2021). Microstructure and Mechanical Properties of the ZrB2-SiC Eutectic Phase Obtained via Induction Plasma Spheroidization. Ceramics Int. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2021.07.074

Wang, C.-C., Li, K.-Z., He, D.-Y., Huo, C.-X., He, Q.-C., and Shi, X.-H. (2019). Microstructure and Oxidation Behavior of MoSi2-Based Coating on Carbon/carbon Composites. Ceramics Int. 45, 21960–21967. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.07.210

Wang, L., Di, Y., Wang, H., Li, X., Dong, L., and Liu, T. (2019). Effect of Lanthanum Zirconate on High Temperature Resistance of Thermal Barrier Coatings. Trans. Indian Ceram. Soc. 78, 212–218. doi:10.1080/0371750X.2019.1690582

Wu, J., Xu, X., Xiong, Y., Guan, X., Jiao, M., Yao, X., et al. (2020). Preparation and Structure Control of a Scalelike MoSi2-Borosilicate Glass Coating with Improved Contact Damage and thermal Shock Resistance. Ceramics Int. 46, 7178–7186. doi:10.1016/j.ceramint.2019.11.212

Wu, X., Shao, G., Shen, X., Cui, S., and Chen, X. (2017). Evolution of the Novel C/SiO2/SiC Ternary Aerogel with High Specific Surface Area and Improved Oxidation Resistance. Chem. Eng. J. 330, 1022–1034. doi:10.1016/j.cej.2017.08.052

Xiao, L., Xu, X., Liu, S., Shen, Z., Huang, S., Liu, W., et al. (2020). Oxidation Behaviour and Microstructure of a Dense MoSi2 Ceramic Coating on Ta Substrate Prepared Using a Novel Two-step Process. J. Eur. Ceram. Soc. 40, 3555–3561. doi:10.1016/j.jeurceramsoc.2020.03.064

Yang, Z., Zhu, D., and Li, H. (2020). A Chitosan-Assisted Co-assembly Synthetic Route to Low-Shrinkage Al2O3-SiO2 Aerogel via Ambient Pressure Drying. Microporous Mesoporous Mater. 293, 109781. doi:10.1016/j.micromeso.2019.109781

Zhao, Y., Zhong, K., Liu, W., Cui, S., Zhong, Y., and Jiang, S. (2020). Preparation and Oil Adsorption Properties of Hydrophobic Microcrystalline Cellulose Aerogel. Cellulose 27, 7663–7675. doi:10.1007/s10570-020-03309-0

Keywords: oxidation resistance, MoSi2–borosilicate glass coating, fiber-reinforced aerogel, thermal protection material, oxidation mechanism

Citation: Dai T, Song Z, Du Y, Zhao Y and Cui S (2021) Oxidation Resistance of Double-Layer MoSi2–Borosilicate Glass Coating on Fiber-Reinforced C/SiO2 Aerogel Composite. Front. Mater. 8:719833. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2021.719833

Received: 03 June 2021; Accepted: 29 July 2021;

Published: 13 October 2021.

Edited by:

Gaofeng Shao, Nanjing University of Information Science and Technology, ChinaReviewed by:

Bin Du, South China University of Technology, ChinaCopyright © 2021 Dai, Song, Du, Zhao and Cui. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Sheng Cui, Y3VpMjAwMnNoZW5nQDEyNi5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.