- 1Department of Industrial Biotechnology, Atta-ur-Rahman School of Applied Biosciences (ASAB), National University of Sciences & Technology (NUST), Islamabad, Pakistan

- 2Materials Research Laboratory, Department of Physics, Faculty of Basic and Applied Sciences (FBAS), International Islamic University (IIU), Islamabad, Pakistan

- 3Pakistan Institute of Medical Sciences (PIMS), Islamabad, Pakistan

- 4School of Textile and Design (STD), University of Management and Technology, Lahore, Pakistan

Synthesis of efficient antibacterial agents has become extremely important due to the emergence of antibiotic resistant bacteria. This is especially true for Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an opportunistic pathogen having ability to rapidly develop resistance to multiple classes of antibiotics thus limiting the efficacy of antibiotics approved for clinical use. Aluminum (Al)-doped NiO nanoparticles are of special interest due to their enhanced antipseudomonal properties at certain Al-doping levels. The composite hydroxide mediated (CHM) approach was opted for the synthesis of pure nickel oxide (NiO) and Al-doped nickel oxide (Ni1–xAlxO; x = 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 wt.%) nanoparticles. X-ray diffraction (XRD) technique was used for structural analysis of these nanoparticles. Morphology and elemental composition of these nanoparticles were investigated by scanning electron microscopy (SEM) and energy dispersive X-ray (EDX) spectroscopy, respectively. The optical properties were investigated by using UV-visible spectroscopy and Kubelka-Munk Theory and Tauc relation were employed for energy bandgap calculation of these nanoparticles. The antibacterial activity of representative Al-doped NiO nanoparticles was assessed on multidrug-resistant clinical P. aeruginosa strains. The agar well and disc-diffusion methods were used to assess the antibacterial efficacy of (Al)-doped NiO compared to pure NiO nanoparticles. Interestingly, a gradual increase in the antibacterial activity was observed with increasing Al-doping concentration and the highest antibacterial activity was observed at x = 15 wt.% Al-doping concentration. The antipseudomonal efficacy of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles was comparable to aztreonam antibiotic, primarily used for Gram-negative bacterial infections. Hence, it is proposed that these nanoparticles can be used for coating surgical devices, bone prostheses, medical implants, antibacterial clothing and in pharmaceutical formulations as burn ointments to produce the antimicrobial effect.

Introduction

In medical sciences, the role of nanotechnology has become vital particularly in targeted therapies with better outcomes and fewer side effects (Kirui et al., 2013). Various metal oxide nanoparticles have already been used in different areas i.e., as a catalyst in wastewater treatment to replace the bleaching process (Srihasam et al., 2020), in commercial paints to kill airborne pathogens, as sensors, semiconductors, for controlled drug release and as antimicrobial agents. There is emerging interest in the synthesis of magnetic NPs of Fe, Co and Ni due to their superior properties in magnetically controlled drug delivery, hypothermia cancer cell treatment and magnetic resonance imaging (Imran Din and Rani, 2016). The applications of metal oxide nanoparticles have gained a lot more interest in antibacterial studies due to their significant concentration-dependent antimicrobial properties (Dizaj et al., 2014; Iqbal et al., 2014). The nanoparticles interact with the surfaces of bacteria as they exhibit high specific surface area (Wang L. et al., 2017).

P. aeruginosa is one of the most important pathogenic bacteria of humans, plants and animals (Wang K. et al., 2017). Infections caused by this notorious pathogen are often difficult to eradicate despite intense antibiotic treatments (Lister et al., 2009). The morbidity and mortality rates due to rapidly evolving MDR P. aeruginosa are on the rise (Waters and Smyth, 2015). In the last report by World Health Organization (WHO), this pathogen has been classified as a top priority critical pathogen against which there is a dire need to develop novel antimicrobial therapeutics (Tacconelli et al., 2017). Different metal-oxide nanoparticles such as cobalt oxide, nickel oxide, zinc oxide, cerium oxide, titanium dioxide, copper oxide, magnesium oxide, silicon dioxide, iron oxide, cadmium oxides, and tin dioxide have shown significant antibacterial activities against various bacteria (Parham et al., 2016; Gupta et al., 2020b). The antibacterial activity of pure-NiO nanoparticles against Gram-negative bacteria (Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Escherichia coli) and Gram-Positive bacteria (Staphylococcus aureus, Streptococcus pneumonia) has been reported (Baek and An, 2011). NiO nanoparticles were found better antibacterial agents than tetracycline and gentamicin antibiotics against Gram-negative and Gram-positive bacteria (Gupta et al., 2020a). The antibacterial activity of NiO nanoparticles using different antimicrobial and biophysical studies revealed that these nanoparticles have stronger antibacterial activity against Gram-positive bacteria compared to Gram-negative bacteria (Behera et al., 2019). In comparison to the previously reported antibacterial activity of pure NiO as well as CuO-NiO composites against different bacteria, the Al-doped NiO nanoparticles have better antibacterial efficacy against Gram-negative bacteria “Pseudomonas aeruginosa”. The Al-doped NiO nanoparticles were found effective for curbing P. aeruginosa growth and population similar to other reported materials (Argueta-Figueroa et al., 2014; Paul and Neogi, 2019). NiO-NPs synthesized from stevia plant leaves have also been found effective against Gram −ive E. coli than the Gram +ive bacteria, Bacillus (12 mm) and Streptococcus pneumoniae (14 mm) [2]. Similarly, NiO nanoparticles biosynthesized from fresh leaves of the Neem plant have shown bacterial cell membrane disruption, which resulted in the death of bacterial cells (Helan et al., 2016). Moreover, the inhibition efficiency of bacterial growth was enhanced in the presence of amoxicillin together with Ni nanoparticles (Jeyaraj Pandian et al., 2016).

The antibacterial activity of Al-doped NiO nanoparticles has not been studied yet. Hence, we attempted to work and understand the antibacterial activity of variably Al-doped NiO nanoparticles against MDR P. aeruginosa clinical isolates. Different methods like wet chemical co-precipitation, sol-gel, hydrothermal or composite hydroxide mediated (CHM) were exercised for the synthesis of nanoparticles (Hulteen et al., 1999; Xu et al., 2007). The composite hydroxide mediated (CHM) route can be preferred to other wet chemical routes to achieve uniform particles’ size with less impurities. The major benefits of this method are; (1) particle distribution in large scale, (2) fast to work at low temperatures, (3) completion of well dispersed nanoparticles, (4) reduction agents influence on the properties of nanomaterial etc. By using CHM method at a lower temperature, the uniform preparation of nanostructures can only be achieved due to the eutectic point of composite hydroxides (Hu et al., 2009). In the present work, CHM route was used for the synthesis of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles. These nanoparticles were structurally analyzed by the XRD technique and optical properties were investigated by using UV-visible spectroscopy. Kubelka-Munk Theory and Tauc relation were employed for the calculation of the energy band gap of these nanoparticles. The morphology and elemental composition of these nanoparticles were investigated by SEM and EDX spectroscopies, respectively. Antibacterial activity of Al-doped and pure NiO samples was tested using agar well and disk-diffusion methods. The zone of inhibition of bacterial growth was measured in millimeters (mm). Kinetic growth curves were recorded to further evaluate the growth dynamics of bacteria in the presence of Al-doped NiO nanoparticles by measuring the optical density of the cultures as a qualitative measure of culture turbidity at 600 nm.

Experimental

Synthesis of Ni1–xAlxO Nanoparticles

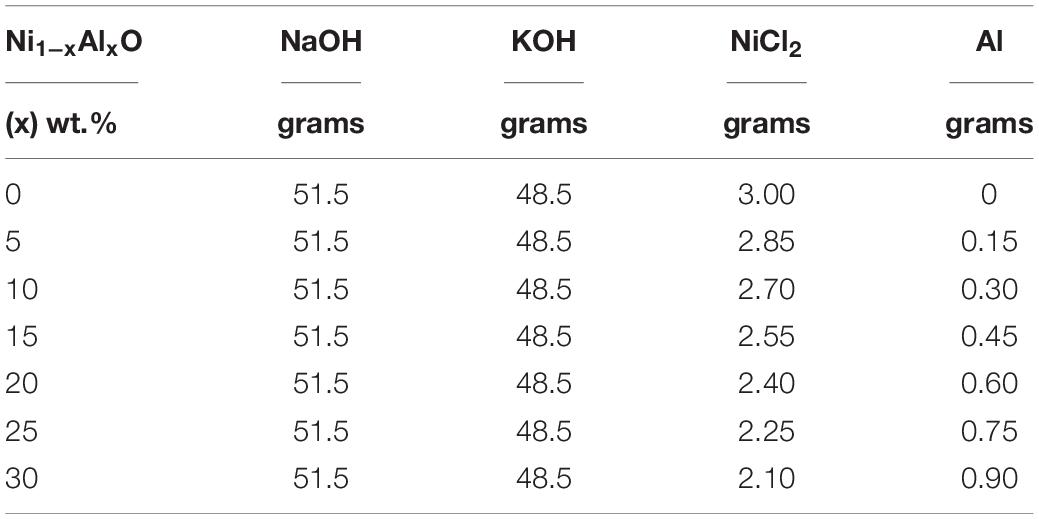

The CHM method was used for the synthesis of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 wt.% nanoparticles due to its eco-friendly characteristics. Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles were prepared from the reaction of nickel chloride and aluminum in the presence of sodium and potassium hydroxide as given by Eqs 1 and 2 and Table 1;

All desired chemicals according to their concentrations as specified in Table 1 were taken in seven Teflon beakers separately and placed in the furnace at 200°C for 24 h. Usually, CHM method is based on the molten form of composite hydroxide as a solvent in reaction at 200°C to synthesize nanostructures. The separately placed Teflon beakers were taken out from the furnace after 24 h and let them cool at room temperature. Then the samples were washed with double-distilled water to remove the deposited hydroxides on the surface of particles. Subsequently, the samples were filtered to obtain the desired grayish-black powder of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles.

Structural, Morphological, and Optical Characterizations

Stoe Stadi P Combi X-ray diffractometer with CuKα source of radiations of wavelength 1.5405 Å was used to determine the crystal structure of these nanoparticles at room temperature. The JEOL - Model JSM-6390 - Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) was used to visualize the microstructures and elemental composition of these nanoparticles. The optical properties of these nanoparticles were investigated by using a UV-visible spectrometer. Kubelka-Munk Theory and Tauc relation were used for computation of energy band gap of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 10, 20 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles.

Microbiology, Culture Conditions, and Antibacterial Activity

The antibacterial activity of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles was checked against MDR P. aeruginosa. Pure cultures of the clinically isolated P. aeruginosa were obtained and sub-cultured on Pseudomonas cetrimide agar (a selective media for P. aeruginosa growth) and incubated for 24 h at 35 °C. For bacterial growth, a 0.5 McFarland suspension of pure bacterial colonies in normal saline was prepared and 100 μL of the suspension was spread onto Muller Hinton agar (MHA) plates. The plates were left for 10 min to let the culture absorb into the agar. Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles suspension of all samples (x = 5∼30 wt.%) ranging from 20,000 to 1.95 μg/ml concentrations were freshly prepared before use. The antibacterial activity was performed by agar well-diffusion and disk-diffusion methods (Kourmouli et al., 2018). The culture plates were seeded with tested organisms and allowed to solidify thereafter punched with a sterile cork borer (5.0 mm diameter) to cut uniform wells. For the agar well diffusion method the Petri plates seeded with culture were punched with a sterile cork borer (6.0 mm diameter) and 100 μl of the nanoparticles suspension was poured into each well with the help of a micropipette. Filter paper discs (6 mm) were saturated with 10 μl of respective nanoparticles suspension and placed on agar plates and incubated at 35°C ± 2°C for 18∼24 h. The zones of inhibition (ZOI) of bacterial growth around wells and discs were measured in millimeters (mm). Nuclease-free water was used as a blank or negative control while aztreonam antibiotic disks were used as a positive control (Luangtongkum et al., 2007). We further check the effects of the doped and pure NiO nanoparticles on the growth dynamics of P. aeruginosa. The bacterial culture was prepared in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth in the presence of colloidal suspension (1 mg/ml) of nanoparticles in 5 ml test tubes. Nanoparticle-free microbial culture under the same growth conditions was used as a control. The bacterial growth was monitored by UV-vis Spectrophotometer at a wavelength of 600 nm for every 2 h.

Results and Discussion

Structure and Morphology

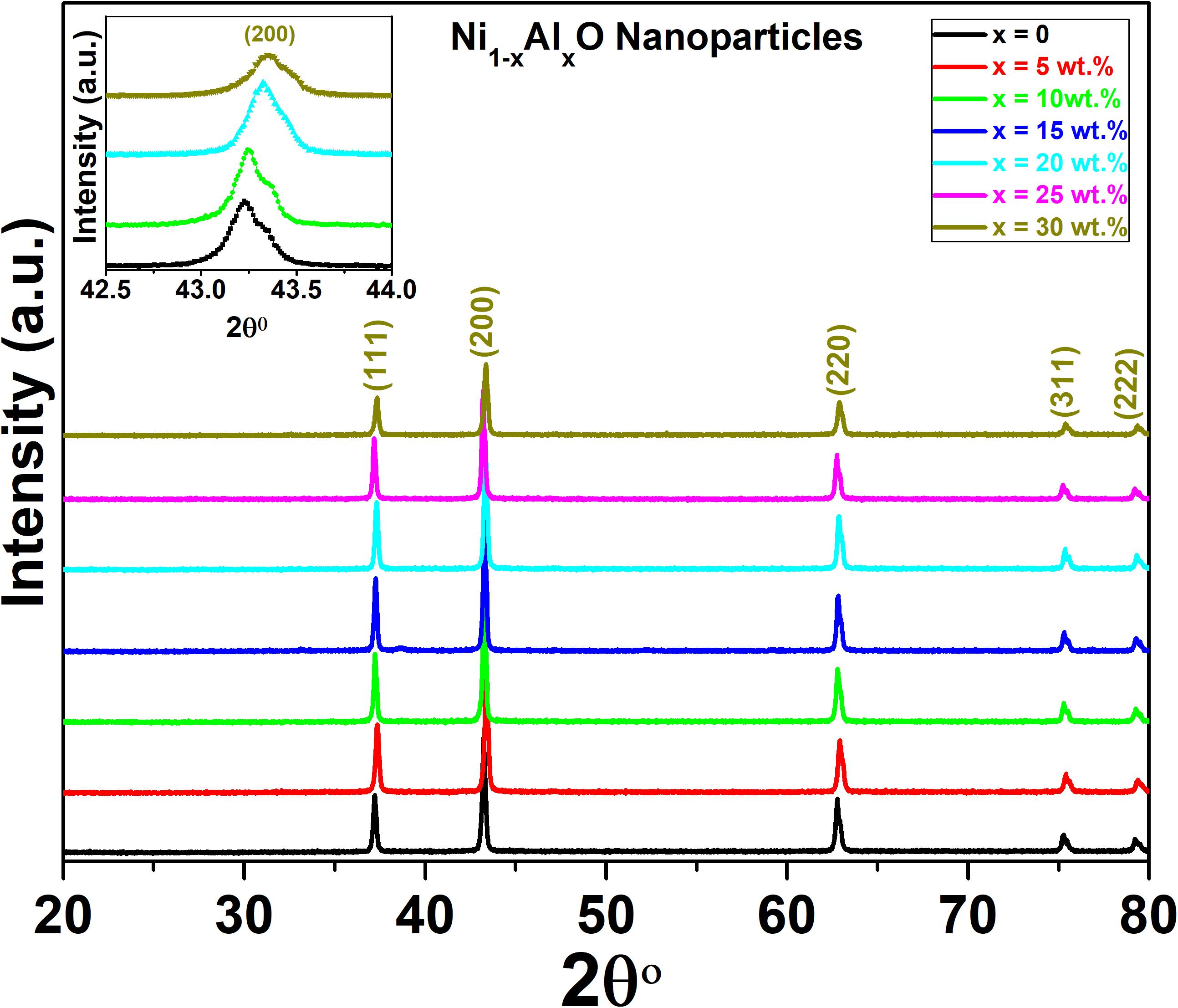

The crystal structure and phase purity of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles were determined by X-ray diffraction (XRD). The XRD spectra of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles from 2θ = 20° to 80° are shown in Figure 1. The diffraction peaks for Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles were properly indexed according to FCC crystal structure using X’pert High Score software and the peaks were found to exactly match with JCPDS card # 01-073-1523. The diffraction planes (111), (200), (220), (311) and (222) correspond to Bragg’s diffraction angles of 38.2°, 43.2°, 63.1°, 76° and 79.5° respectively as shown in Figure 1. Moreover, no impurity peak was observed in XRD spectra and the characteristics peak at 43.2° corresponds to (200) plane of FCC crystal structure of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles. The intensity of the diffraction peaks was found to increase with increasing contents of Al in Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles. It was also observed that the characteristic peaks were slightly shifted toward a higher angle with increasing contents of Al as shown in the inset of Figure 1. The change in the intensity and position of diffraction peaks confirmed Al-doping at Ni sites in Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles (Stuart, 2015). This may also indicate the changing in crystal structure due to vacancies and defects creation at the lattice sites or the charge imbalance through Al-doping at Ni lattice sites (Thermo Nicolet Corporation, 2001). The average crystallite size of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles was calculated by Debye-Scherrer’ formula (Mersian et al., 2018) and observed to be 22, 21.2, 18, 16.3, 14.8, 13.1, and 12.7 nm for x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.%, respectively. The decrease in average crystallite size of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles can be associated with smaller ionic radius of Al as compared to ionic radius of Ni, which may cause a decrease in bond length of the unit cell and ultimately cause the decrease in crystallite size of these nanoparticles.

Figure 1. XRD spectra of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 wt.% nanoparticles. In the inset there is shown the shifting of characteristic peak corresponding to (200) plane of FCC crystal structure of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles.

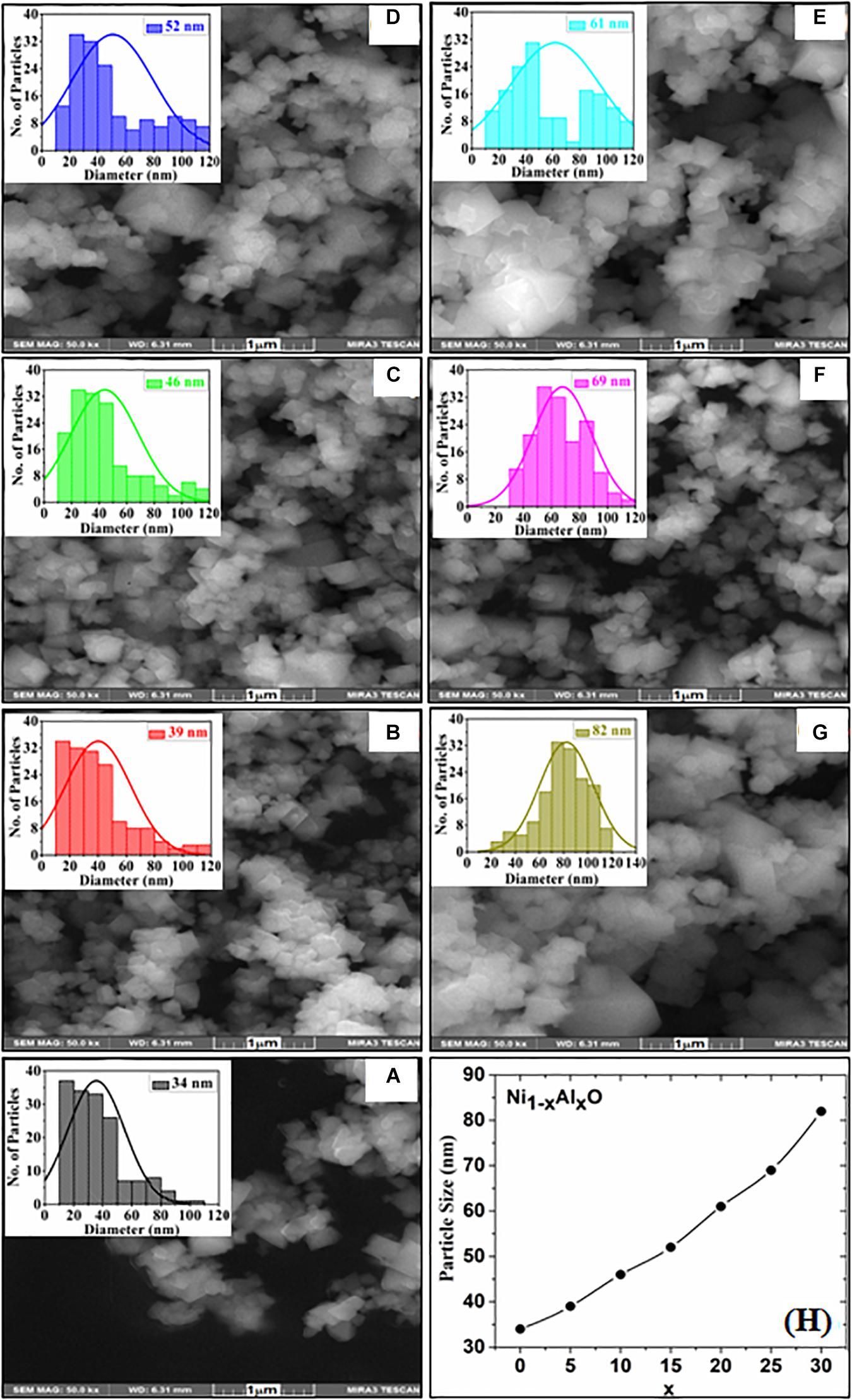

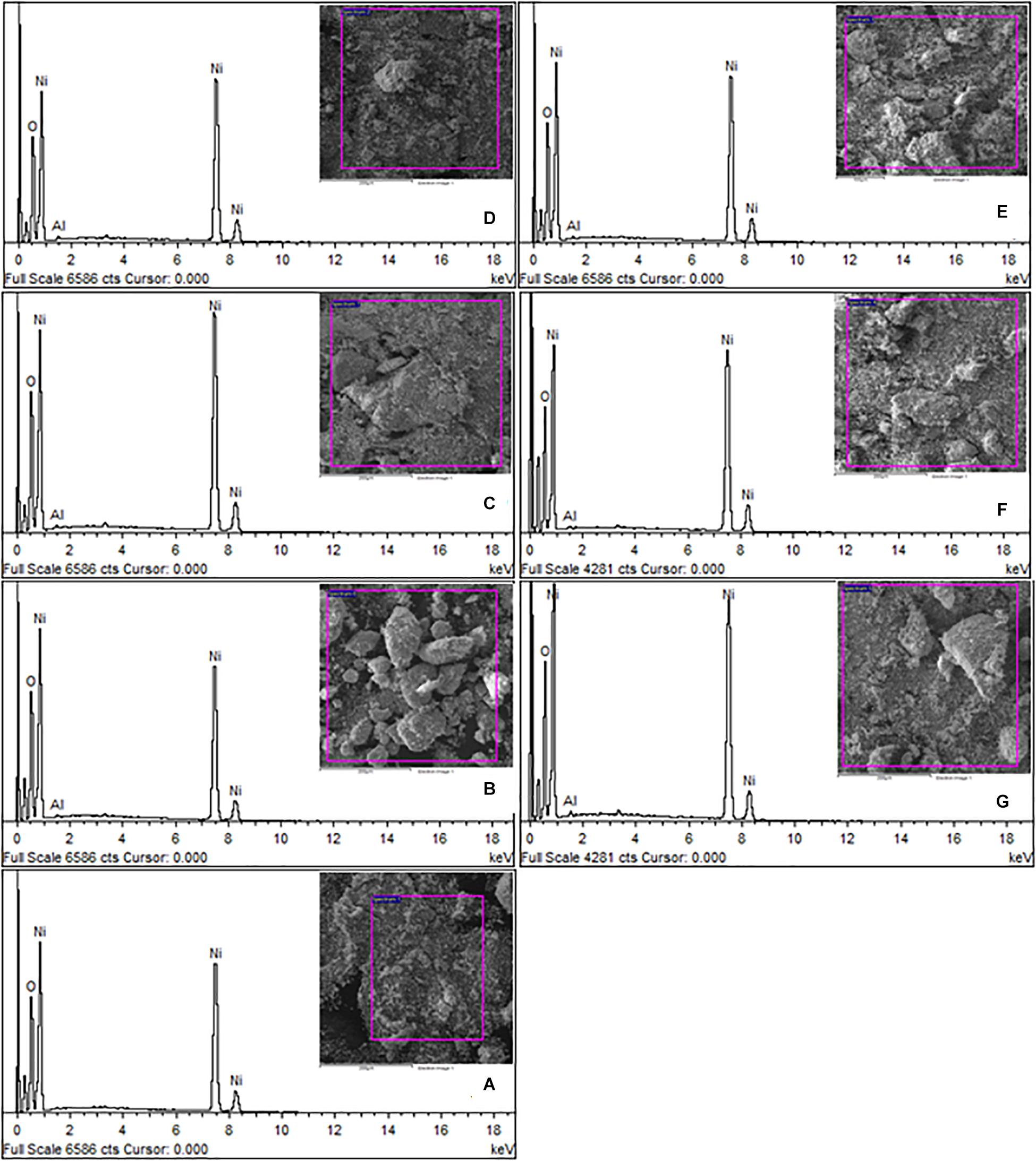

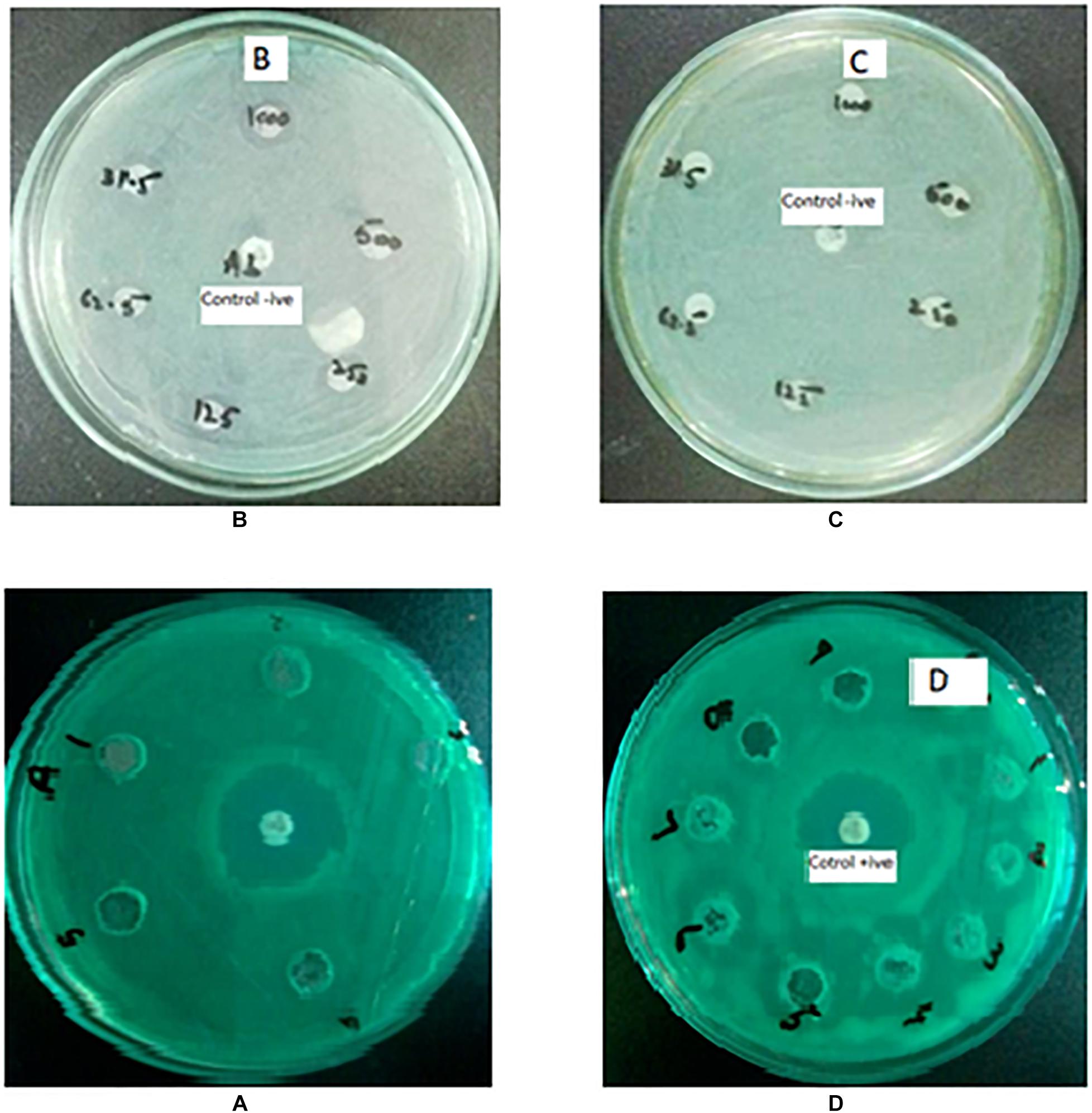

Surface morphology, shape and size of these Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles were visualized by SEM images as shown in Figures 2A–G. The variation of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles’ size from 30∼85 nm with Al contents (x) is shown in Figure 2H. Some nanoparticles were observed to be agglomerated and clustered due to magnetic interaction among these magnetic nanoparticles (Muhammed Shafi and Chandra Bose, 2015). The average particle sizes of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles were further calculated through histograms and standard deviation as shown in the insets of respective SEM images in Figures 2A–G. The mean diameter of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles was found to be 34, 39, 46, 52, 61, 69, 82 nm for x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.%, respectively. The morphology of the nanostructures can be controlled by varying the synthesis parameters. The basic parameters that can affect the grain-growth or the particle size are; (i) Stirring, (ii) Concentration of dopants, (iii) Reaction temperature, (iv) Reaction time, (v) pH-scale value, and (vi) Reagents rate etc. In current study, these nanoparticles have been synthesized under the same synthesis conditions, but the different sizes of ionic radii of Al and Ni caused the strain field that can disturb the grain growth process. Thus, the interactions between the dopants and surface/grain boundaries may vary the surface energy, thus leading the stabilization of the surfaces/grain boundaries, as a result, the particle size of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles has been increased with increasing contents of Al. Moreover, Al doping has decreased the crystallite size as evident from XRD and large number of crystallites have merged together during nucleation process to form nanoparticles of relatively large in size as clear from Figure 2F. The EDX spectroscopy was used to determine the quantitative elemental composition of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles. The EDX spectra of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles are shown in Figures 3A–G. The percentage values of Ni, Al and O contents in Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles are given in Table 2.

Figure 2. (A–G) SEM images with inset histograms of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 wt.% nanoparticles, respectively, (H) Variation of particles size verses Al contents (x).

Figure 3. (A–G) EDX spectra of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 wt.% nanoparticles, respectively.

Table 2. Variation of chemical compositions of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 wt.% nanoparticles.

Optical Properties

The optical properties of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles were investigated by UV-visible spectroscopy in the ranges of 250 to 1,000 nm. The Kubelka-Munk model was employed to determine the energy bandgap “Eg” of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles. The Kubelka-Munk F(R)2 and Tauc’s relation are given in Eqs 3 and 4 below (Shahid et al., 2018).

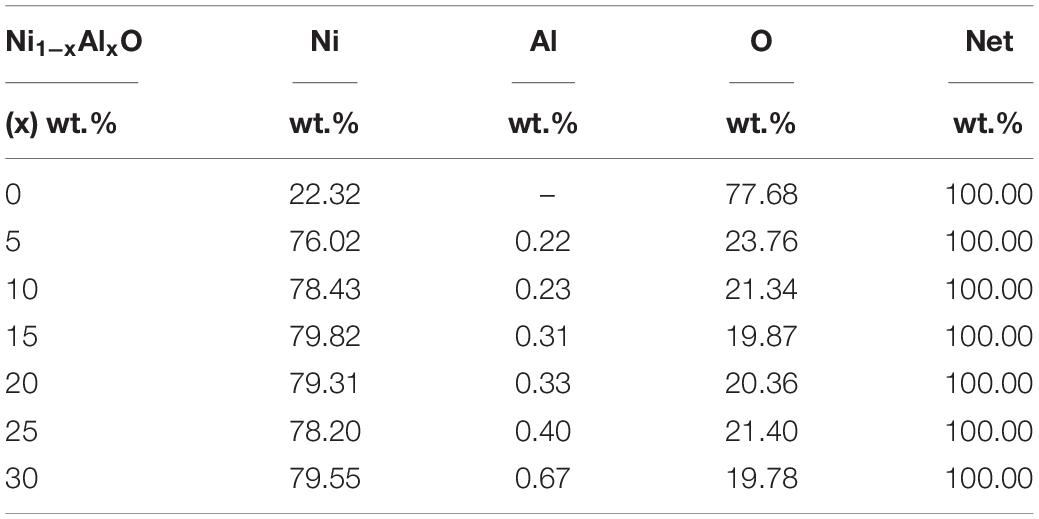

where “n” represents an exponent which is “2” for indirect and “½” for direct bandgap transition, “h” is Plank’s constant, “hυ” is the energy associated with photon in eV and “R” represents the reflectance. The representative UV-visible spectra of representative Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 10, 20 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles are given in Figures 4A–D. The values of Eg calculated by Kubulka-Munk theory and Tauc’s relation of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles were found to be 2.3, 3.2, 4.5 and 3.3 eV for x = 0, 10, 20 and 30 wt.%, respectively. The value of Eg was increased overall with increasing contents of Al in Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles, which could be attributed to the increased particle size. Generally, semiconductor nanomaterials absorb light due to which valence electrons jump from valence band to conduction band which creates a hole behind if the nanoparticles have size comparable to that of de-Broglie wavelength. As there are different energies for conduction band and free electrons that cause quantization of their energy levels (Shahid et al., 2016) thus, the Eg of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles was increased due to an increase in particle size as compared to bulk NiO.

Figure 4. (A–D) Variation of energy band gaps of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 10, 20 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles, respectively.

Antipseudomonal Activity of Nanoparticles

Disc-Diffusion and Agar Well Diffusion Method

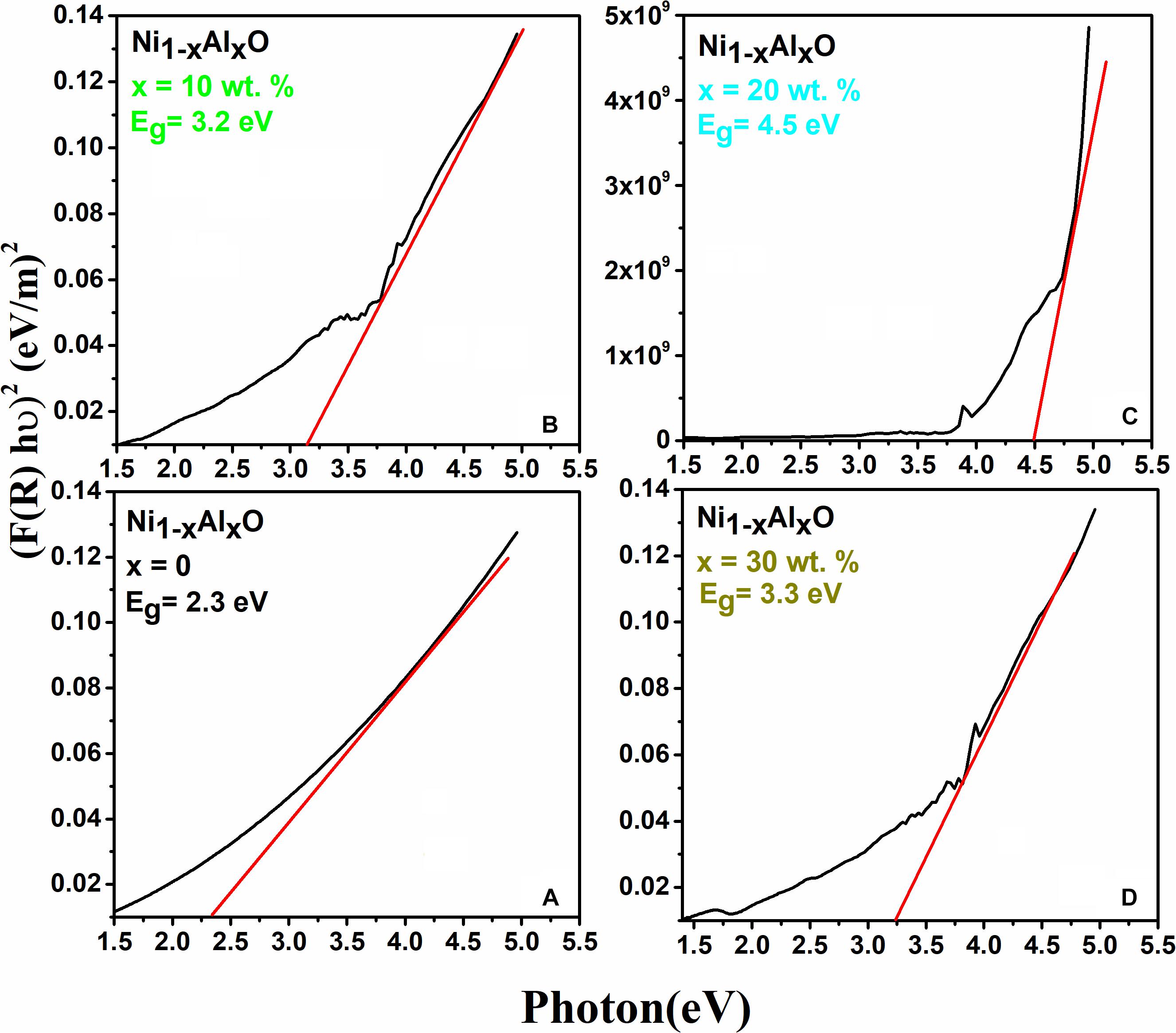

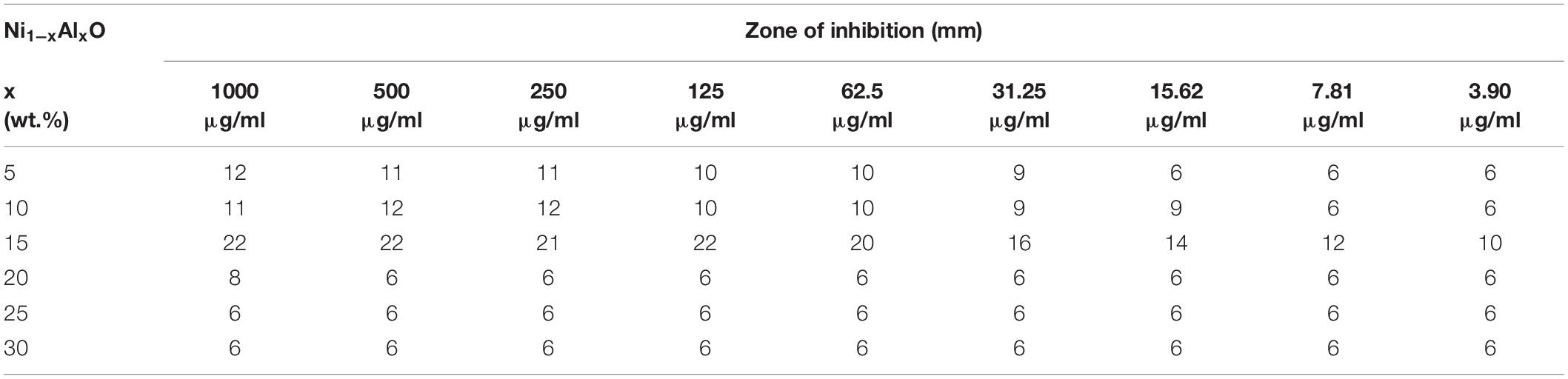

The antibacterial activity of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles was assessed by agar well and disc-diffusion method as given in Figures 5A–D. No significant antibacterial activity was observed for pure NiO nanoparticles. Relatively significant antibacterial activities were observed for Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles with x = 5 and 10 wt.% as shown in Figures 5B,C. Surprisingly, a remarkable increase in anti-Pseudomonal activity was observed for Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles with x = 15 wt.% as shown in Figure 5D. The ZOI of bacterial growth for Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles with x = 15 wt.% was comparable with ZOI of aztreonam antibiotic used in the form of a disk as a positive control. Aztreonam is used primarily to treat the infections caused by most of the Gram-negative bacteria i.e., P. aeruginosa (Lemke et al., 2017). For Al-doped NiO nanoparticles area/size of ZOI ranging from 10 to 22 mm were observed at concentrations of 3.90 to 1,000 μg/ml. A remarkable increase in ZOI is suggestive of enhanced antibacterial activity of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles with x = 15 wt.% (Table 3). NiO NPs have been found to have bactericidal activity depending on the bacterial species and NPs concentrations (Nikolova and Chavali, 2020). Promising antibacterial activity of NiO against Gram-negative bacteria has already been reported in which they have suggested that the release of metal ions from metal oxide nanoparticles could be one of the key factors behind their antibacterial properties (Wang et al., 2010). One of the advantages of doping metal oxides with metal dopants is that they decrease VB to VC bandgap and help to convert low efficient UV- visible light-absorbing materials into highly efficient light-absorbing materials (Djerdj et al., 2010) and also affect the overall surface area and morphology of inactive metal oxides (Lin et al., 2005). A decrease in the bandgap effectively generates photo-induced charge carriers and eventually helps to generate •OH, O2-•, HOO•, which are highly oxidized species. These highly oxidized species directly attack the cell membrane leading to plasmolysis and cell death (Guillard et al., 2008). The antimicrobial characteristics of Fe-doped TiO2 have been observed to increase in the fluorescent light more efficiently than un-doped TiO2 (Yadav et al., 2016). Enhanced antibacterial properties of Co-doped in ZnO nanoparticles against Klebsiella pneumoniae, Salmonella typhi, P. aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus subtilis and Shigella dysenteriae bacterial strains has been reported (Nair et al., 2011). Similarly, surface functionalization of NiO NPs with 5-amino-2-mercaptobenzimidazole enhanced both the bactericidal (against P. aeruginosa and S. aureus) and antifungal activity compared with the non-functionalized NiO NPs (Nikolova and Chavali, 2020).

Figure 5. (A–D) Antibacterial effects against P. aeruginosa (A) Pure NiO nanoparticles with no antibacterial activity, antibiotic aztreonam in middle was used as positive control. (B–D) Zone of inhibition produced by Al-doped NiO nanoparticles at x = 5, 10, and 15 wt.%, respectively.

Table 3. Estimation of zone of inhibition (ZOI) of Ni1–xAlxO; x = 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 wt.% nanoparticles.

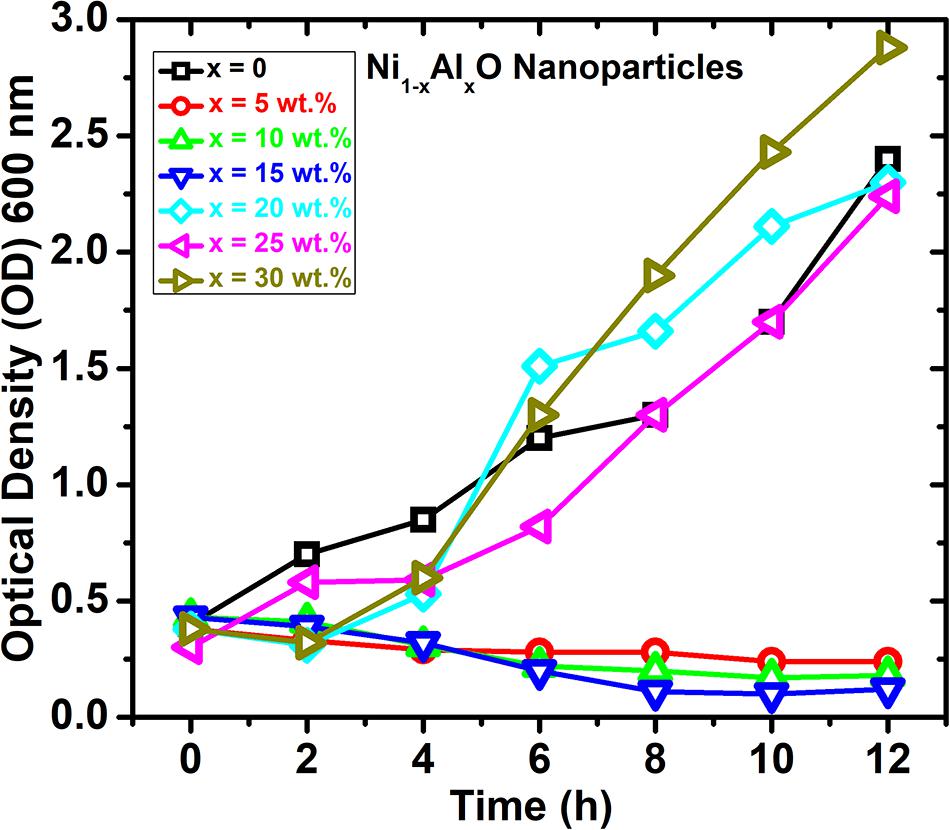

Bacterial Growth Curve Analysis

The growth curve kinetics of P. aeruginosa in the presence of pure and Al-doped NiO nanoparticles is shown in Figure 6. These results indicate that the antibacterial activity of Al-doped NiO nanoparticles is effectively improved by increasing Al-doping concentrations. The maximum bactericidal activity has been observed at 15 wt.% of Al-doping in NiO nanoparticles.

Figure 6. Growth dynamics and variation of optical density of the P. aeruginosa culture in the presence of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles.

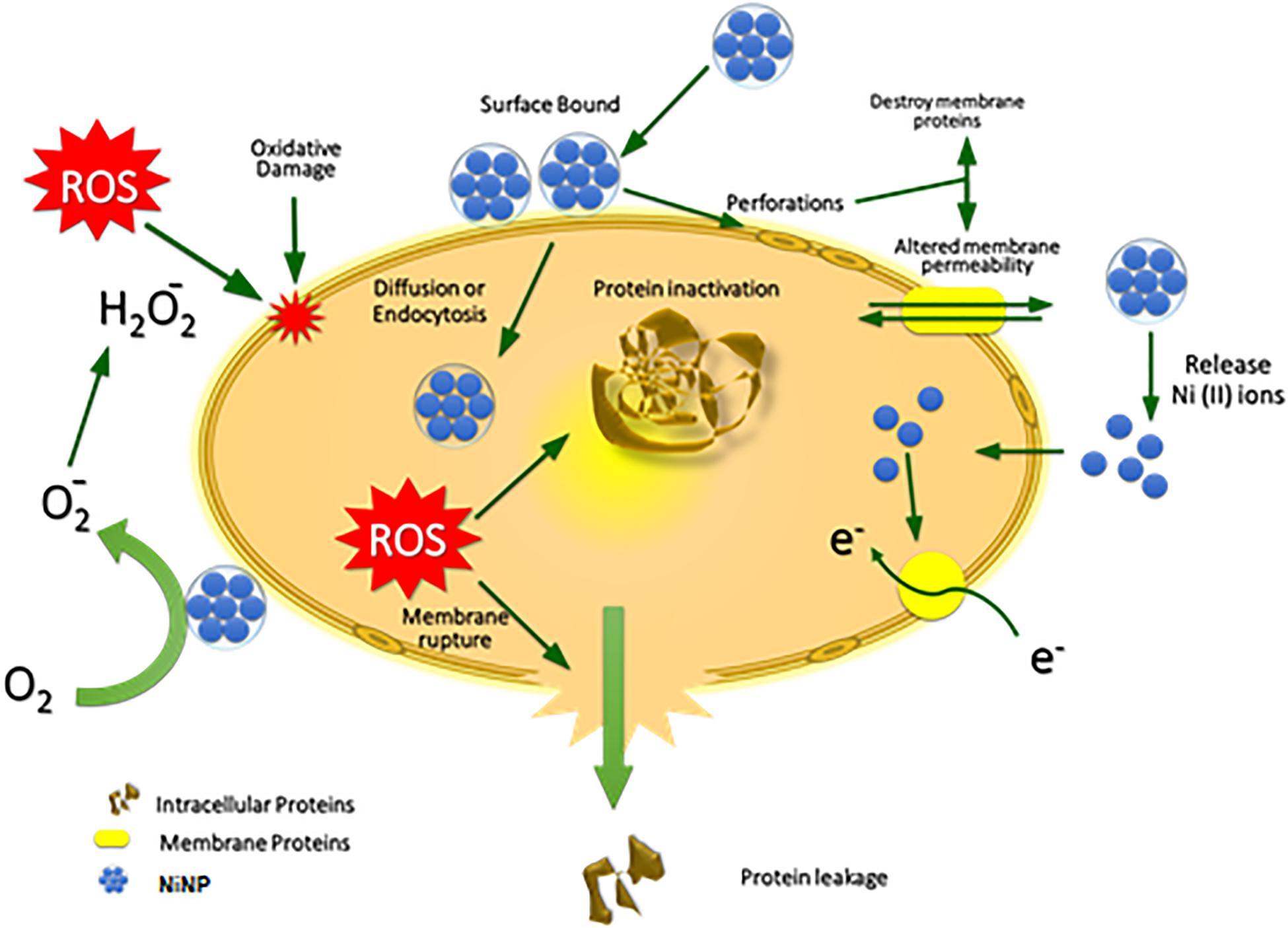

The hypothetical antibacterial mechanism of the NiO-NPs is shown in Figure 7. The electrostatic forces of attraction between nanoparticles and cell membrane cause membrane disruption and cell apoptosis leading to leakage of intracellular components from the cell (Alzahrani et al., 2018). Another possible mechanism could be the release of metal ions from nanoparticles which neutralize the surface charge of Gram-negative bacteria, slowing down their growth rate thus, ultimately leading to malfunction of core proteins for survival resulting in cell death (Paul and Neogi, 2019). NiO NPs released Ni ions which might interfere with the intracellular metabolism of Ca2+ ions leading to cellular damage. NiO NPs have also been shown to interact with phosphorous and sulfur of bacterial DNA and other functional groups of proteins leading to protein leakage and bacterial death (Ezhilarasi et al., 2018).

Moreover, the penetration of nanoparticles inside the bacterial cell interacts and inhibits the electron transport chain, damaging the DNA by breaking hydrogen and phosphate bonds, denaturing tertiary structures of proteins and damaging the powerhouse (mitochondria) of the bacterial cell by oxidative stress due to generation of ROS by inorganic metallic oxides (Srihasam et al., 2020). The potential antibacterial properties mainly depend on the size, shape, concentration, stability, morphology and exposure/treatment time (Jesudoss et al., 2016).

Conclusion

The Ni1–xAlxO; x = 0, 5, 10, 15, 20, 25 and 30 wt.% nanoparticles were successfully synthesized by CHM method. The FFC crystal structure, phase purity and Al-doping at Ni sites in Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles were probed by the XRD technique. The slight shift in the characteristic diffraction peaks toward a higher angle indicated the stresses produced with Al-doing in Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles. The particle size of Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles was found to be 30∼85 nm. The value of Eg was observed to be 2.3∼4.5 eV with increasing Al-doping in Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles, which was due to the increased particle size of these nanoparticles. A gradual increase in antibacterial activity was observed with increasing Al-doping up to x = 15 wt.% in Ni1–xAlxO nanoparticles. Maximum bacterial growth inhibition was observed at doping level x = 15 wt.% while exceeding this doping has negatively impacted the antipseudomonal activity. These measurements and analysis suggest that Al is a suitable candidate for doping in NiO nanoparticles to enhance antipseudomonal properties.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author Contributions

SI and MM designed the study and wrote the draft. SS, ZM, and GG helped in performing experiments. Mubasher and MAb helped in the characterization of synthesized nanoparticles. MAr provided bacterial strains for experiments. SA reviewed and approved the final draft. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Alzahrani, K. E., Niazy, A. A., Alswieleh, A. M., Wahab, R., El-Toni, A. M., and Alghamdi, H. S. (2018). Antibacterial activity of trimetal (CuZnFe) oxide nanoparticles. Int. J. Nanomed. 13:77. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S154218

Argueta-Figueroa, L., Morales-Luckie, R. A., Scougall-Vilchis, R. J., and Olea-Mejía, O. F. (2014). Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of copper, nickel and bimetallic Cu–Ni nanoparticles for potential use in dental materials. Prog. Nat. Sci. Mater. Int. 24, 321–328. doi: 10.1016/j.pnsc.2014.07.002

Baek, Y.-W., and An, Y.-J. (2011). Microbial toxicity of metal oxide nanoparticles (CuO, NiO, ZnO, and Sb2O3) to Escherichia coli, Bacillus subtilis, and Streptococcus aureus. Sci. Total Environ. 409, 1603–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2011.01.014

Behera, N., Arakha, M., Priyadarshinee, M., Pattanayak, B. S., Soren, S., Jha, S., et al. (2019). Oxidative stress generated at nickel oxide nanoparticle interface results in bacterial membrane damage leading to cell death. RSC Adv. 9, 24888–24894. doi: 10.1039/C9RA02082A

Dizaj, S. M., Lotfipour, F., Barzegar-Jalali, M., Zarrintan, M. H., and Adibkia, K. (2014). Antimicrobial activity of the metals and metal oxide nanoparticles. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 44, 278–284. doi: 10.1016/j.msec.2014.08.031

Djerdj, I., Jagličić, Z., Arčon, D., and Niederberger, M. (2010). Co-doped ZnO nanoparticles: minireview. Nanoscale 2, 1096–1104. doi: 10.1039/C0NR00148A

Ezhilarasi, A. A., Vijaya, J. J., Kaviyarasu, K., Kennedy, L. J., Ramalingam, R. J., and Al-Lohedan, H. A. (2018). Green synthesis of NiO nanoparticles using Aegle marmelos leaf extract for the evaluation of in-vitro cytotoxicity, antibacterial and photocatalytic properties. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B Biol. 180, 39–50. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.01.023

Guillard, C., Bui, T.-H., Felix, C., Moules, V., Lina, B., and Lejeune, P. (2008). Microbiological disinfection of water and air by photocatalysis. C. R. Chim. 11, 107–113. doi: 10.1016/j.crci.2007.06.007

Gupta, V., Kant, V., Gupta, A., and Sharma, M. (2020a). Synthesis, characterization and concentration dependant antibacterial potentials of nickel oxide nanoparticles against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. Nanosyst. Phys. Chem. Math. 11, 237–245. doi: 10.17586/2220-8054-2020-11-2-237-245

Gupta, V., Kant, V., Sharma, A., and Sharma, M. (2020b). Comparative assessment of antibacterial efficacy for cobalt nanoparticles, bulk cobalt and standard antibiotics: a concentration dependant study. Nanosyst. Phys. Chem. Math. 11, 78–85. doi: 10.17586/2220-8054-2020-11-1-78-85

Helan, V., Prince, J. J., Al-Dhabi, N. A., Arasu, M. V., Ayeshamariam, A., Madhumitha, G., et al. (2016). Neem leaves mediated preparation of NiO nanoparticles and its magnetization, coercivity and antibacterial analysis. Results Phys. 6, 712–718. doi: 10.1016/j.rinp.2016.10.005

Hu, C., Xi, Y., Liu, H., and Wang, Z. L. (2009). Composite-hydroxide-mediated approach as a general methodology for synthesizing nanostructures. J. Mater. Chem. 19, 858–868. doi: 10.1039/B816304A

Hulteen, J. C., Treichel, D. A., Smith, M. T., Duval, M. L., Jensen, T. R., and Van Duyne, R. P. (1999). Nanosphere lithography: size-tunable silver nanoparticle and surface cluster arrays. J. Phys. Chem. B 103, 3854–3863. doi: 10.1021/jp9904771

Imran Din, M., and Rani, A. (2016). Recent advances in the synthesis and stabilization of nickel and nickel oxide nanoparticles: a green adeptness. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2016:3512145. doi: 10.1155/2016/3512145

Iqbal, J., Jan, T., Ismail, M., Ahmad, N., Arif, A., Khan, M., et al. (2014). Influence of Mg doping level on morphology, optical, electrical properties and antibacterial activity of ZnO nanostructures. Ceram. Int. 40, 7487–7493. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2013.12.099

Jesudoss, S., Vijaya, J. J., Selvam, N. C. S., Kombaiah, K., Sivachidambaram, M., Adinaveen, T., et al. (2016). Effects of Ba doping on structural, morphological, optical, and photocatalytic properties of self-assembled ZnO nanospheres. Clean Technol. Environ. Policy 18, 729–741. doi: 10.1007/s10098-015-1047-1

Jeyaraj Pandian, C., Palanivel, R., and Dhanasekaran, S. (2016). Screening antimicrobial activity of nickel nanoparticles synthesized using Ocimum sanctum leaf extract. J. Nanopart. 2016:4694367. doi: 10.1155/2016/4694367

Kirui, D. K., Khalidov, I., Wang, Y., and Batt, C. A. (2013). Targeted near-IR hybrid magnetic nanoparticles for in vivo cancer therapy and imaging. Nanomed. Nanotechnol. Biol. Med. 9, 702–711. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2012.11.009

Kourmouli, A., Valenti, M., van Rijn, E., Beaumont, H. J., Kalantzi, O.-I., Schmidt-Ott, A., et al. (2018). Can disc diffusion susceptibility tests assess the antimicrobial activity of engineered nanoparticles? J. Nanopart. Res. 20, 1–6. doi: 10.1007/s11051-018-4152-3

Lemke, A. A., Hutten Selkirk, C. G., Glaser, N. S., Sereika, A. W., Wake, D. T., Hulick, P. J., et al. (2017). Primary care physician experiences with integrated pharmacogenomic testing in a community health system. Pers. Med. 14, 389–400. doi: 10.2217/pme-2017-0036

Lin, H.-F., Liao, S.-C., and Hung, S.-W. (2005). The dc thermal plasma synthesis of ZnO nanoparticles for visible-light photocatalyst. J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 174, 82–87. doi: 10.1016/j.jphotochem.2005.02.015

Lister, P. D., Wolter, D. J., and Hanson, N. D. (2009). Antibacterial-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: clinical impact and complex regulation of chromosomally encoded resistance mechanisms. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 22, 582–610. doi: 10.1128/CMR.00040-09

Luangtongkum, T., Morishita, T. Y., El-Tayeb, A. B., Ison, A. J., and Zhang, Q. (2007). Comparison of antimicrobial susceptibility testing of Campylobacter spp. by the agar dilution and the agar disk diffusion methods. J. Clin. Microbiol. 45, 590–594. doi: 10.1128/JCM.00986-06

Mersian, H., Alizadeh, M., and Hadi, N. (2018). Synthesis of zirconium doped copper oxide (CuO) nanoparticles by the Pechini route and investigation of their structural and antibacterial properties. Ceram. Int. 44, 20399–20408. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.08.033

Muhammed Shafi, P., and Chandra Bose, A. (2015). Impact of crystalline defects and size on X-ray line broadening: a phenomenological approach for tetragonal SnO2 nanocrystals. AIP Adv. 5:057137. doi: 10.1063/1.4921452

Nair, M. G., Nirmala, M., Rekha, K., and Anukaliani, A. (2011). Structural, optical, photo catalytic and antibacterial activity of ZnO and Co doped ZnO nanoparticles. Mater. Lett. 65, 1797–1800. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2011.03.079

Nikolova, M. P., and Chavali, M. S. (2020). Metal oxide nanoparticles as biomedical materials. Biomimetics 5:27. doi: 10.3390/biomimetics5020027

Parham, S., Wicaksono, D. H., Bagherbaigi, S., Lee, S. L., and Nur, H. (2016). Antimicrobial treatment of different metal oxide nanoparticles: a critical review. J. Chin. Chem. Soc. 63, 385–393. doi: 10.1002/jccs.201500446

Paul, D., and Neogi, S. (2019). Synthesis, characterization and a comparative antibacterial study of CuO, NiO and CuO-NiO mixed metal oxide. Mater. Res. Express 6:055004. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/ab003c

Shahid, T., Arfan, M., Zeb, A., BiBi, T., and Khan, T. M. (2018). Preparation and physical properties of functional barium carbonate nanostructures by a facile composite-hydroxide-mediated route. Nanomater. Nanotechnol. 8:184. doi: 10.1177/1847980418761775

Shahid, T., Khan, T., Zakria, M., Shakoor, R., and Arfan, M. (2016). Synthesis of pyramid-shaped NiO nanostructures using low-temperature composite-hydroxide-mediated approach. J. Mater. Sci. Eng. 5:6. doi: 10.4172/2169-0022.1000287

Srihasam, S., Thyagarajan, K., Korivi, M., Lebaka, V. R., and Mallem, S. P. R. (2020). Phytogenic generation of NiO nanoparticles using Stevia leaf extract and evaluation of their in-vitro antioxidant and antimicrobial properties. Biomolecules 10:89. doi: 10.3390/biom10010089

Stuart, B. (2015). “Infrared spectroscopy,” in Kirk-Othmer Encyclopedia of Chemical Technology (New York, NY: John Wiley & Sons, Inc). doi: 10.1002/0471238961.0914061810151405.a01.pub3

Tacconelli, E., Magrini, N., Kahlmeter, G., and Singh, N. (2017). Global priority list of antibiotic-resistant bacteria to guide research, discovery, and development of new antibiotics. World Health Organ. 27, 318–327. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(17)30753-3

Thermo Nicolet Corporation (2001). Introduction to Fourier Transform Infrared Spectrometry. Madison, WI: Thermo Nicolet Corporation.

Wang, K., Chen, Y.-Q., Salido, M. M., Kohli, G. S., Kong, J.-l, Liang, H.-J., et al. (2017). The rapid in vivo evolution of Pseudomonas aeruginosa in ventilator-associated pneumonia patients leads to attenuated virulence. Open Biol. 7:170029.

Wang, L., Hu, C., and Shao, L. (2017). The antimicrobial activity of nanoparticles: present situation and prospects for the future. Int. J. Nanomed. 12:1227. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S121956

Wang, Z., Lee, Y.-H., Wu, B., Horst, A., Kang, Y., Tang, Y. J., et al. (2010). Anti-microbial activities of aerosolized transition metal oxide nanoparticles. Chemosphere 80, 525–529. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2010.04.047

Waters, V., and Smyth, A. (2015). Cystic fibrosis microbiology: advances in antimicrobial therapy. J. Cyst. Fibros. 14, 551–560. doi: 10.1016/j.jcf.2015.02.005

Xu, J., Yang, H., Fu, W., Du, K., Sui, Y., Chen, J., et al. (2007). Preparation and magnetic properties of magnetite nanoparticles by sol–gel method. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 309, 307–311. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2006.07.037

Keywords: NiO nanoparticles, Al-doping, Pseudomonas aeruginosa, antipseudomonal activity, antimicrobial surface coatings

Citation: Irum S, Andleeb S, Sardar S, Mustafa Z, Ghaffar G, Mumtaz M, Mubasher, Arslan M and Abbas M (2021) Chemical Synthesis and Antipseudomonal Activity of Al-Doped NiO Nanoparticles. Front. Mater. 8:673458. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2021.673458

Received: 27 February 2021; Accepted: 29 March 2021;

Published: 20 April 2021.

Edited by:

Asma Tufail Shah, COMSATS University Islamabad, PakistanReviewed by:

Khurram Shehzad, Zhejiang University, ChinaSumaira Naeem, University of Gujrat, Pakistan

Copyright © 2021 Irum, Andleeb, Sardar, Mustafa, Ghaffar, Mumtaz, Mubasher, Arslan and Abbas. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Saadia Andleeb, c2FhZGlhLmFuZGxlZWJAYXNhYi5udXN0LmVkdS5waw==; c2FhZGlhbWFyd2F0QHlhaG9vLmNvbQ==

Sidra Irum

Sidra Irum Saadia Andleeb

Saadia Andleeb Sumbal Sardar

Sumbal Sardar M. Mumtaz

M. Mumtaz Mubasher

Mubasher Mudassar Abbas

Mudassar Abbas