94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mater., 20 April 2021

Sec. Smart Materials

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2021.667685

This article is part of the Research TopicSynthesis, Characterization and Applications of Magneto-Responsive Functional MaterialsView all 11 articles

Hard-magnetic barium ferrite (BF) nanoparticles with a hexagonal plate-like structure were used as an additive to a carbonyl iron (CI) microparticle-based magnetorheological (MR) fluid. The morphology of the pristine CI and CI/BF mixture particles was examined by scanning electron microscopy. The saturation magnetization and coercivity values of each particle were measured in the powder state by vibrating sample magnetometry. The MR characteristics of the CI/BF MR fluid measured using a rotation rheometer under a range of magnetic field strengths were compared with those of the CI-based MR fluid. The flow behavior of both MR fluids was fitted using a Herschel–Bulkley model, and their stress relaxation phenomenon was examined using the Schwarzl equation. The MR fluid with the BF additive showed higher dynamic and elastic yield stresses than the MR fluid without the BF additive as the magnetic field strength increased. Furthermore, the BF nanoparticles embedded in the space between the CI microparticles improved the dispersion stability and the MR performance of the MR fluid.

Magnetorheological (MR) fluids consisting of soft-magnetic particles suspended in a medium liquid, including silicone oil and mineral oil, are field-responsive functional materials that can be finely controlled from the liquid-like state to a solid-like phase under an applied magnetic field strength (H) (Svåsand et al., 2009; Sedlačík et al., 2010; Susan-Resiga et al., 2010; Qiao et al., 2012; Ashtiani et al., 2015). Without H, the particles in an MR fluid are dispersed randomly in the MR suspension, following a Newtonian fluid-like behavior at their low-particle volume concentrations. Under an applied H, the field-induced magnetic polarization interactions of the magnetic particles result in the formation of a chain-like form in the parallel direction of the applied H within several tens of milliseconds (Vasiliev et al., 2016). During this rapid and reversible phase transition, the chain structures in the MR fluid undergo breaking and reformation processes, resulting in changes in their viscoelastic characteristics, including shear stress, shear viscosity, and dynamic moduli under an applied magnetic field (Li et al., 2000, 2004; Ahamed et al., 2016). This technology has been introduced to industrial sections, such as damping devices, engine mounts, and MR polishing machines (Choi et al., 2003; Yang et al., 2010; Mao et al., 2014).

Soft-magnetic particles are widely adopted as the dispersed part of the MR fluids, owing to their negligible magnetic hysteresis and supreme magnetization value of saturation (Kordonskii et al., 1999). Among their family, carbonyl iron (CI) microparticles have attracted considerable attention as disperse particles owing to their large magnetic permeability, low coercivity, spherical shape, and appropriate micron size (Bombard et al., 2005). Despite these advantages, the high density of CI microparticles can lead to problems, such as sedimentation and abrasion, which are of concern with long-term industrial applications.

Several techniques have been introduced to overcome these problems, including coating the surface of magnetic microspheres with polymeric or inorganic materials and adding various additives, such as organic clay and inorganic nanoparticles (Vicente et al., 2003; Fang and Choi, 2008; López-López et al., 2008; Aruna et al., 2019). On the other hand, the process of applying a polymeric coating of CI microparticles to decrease the difference in density between the CI microspheres and the non-magnetic fluid is too difficult and complex for industrial application. This is because the coating process is strongly influenced by various factors, such as the reaction temperature, time, and the molar ratio between monomer and initiator. Therefore, the addition of additives to CI-based MR suspensions is rather simple and reliable (Jang et al., 2005; Liu et al., 2015; Han et al., 2019; Aruna et al., 2020; Maurya and Sarkar, 2020).

Various additives, such as organic clays, carbon nanotubes, celluloses, and inorganic particles, have been introduced in MR fluid systems to enhance the sedimentation stability of magnetic particles composed predominantly of MR fluids (Machovsky et al., 2014; Bae et al., 2017; Bossis et al., 2019; Gopinath et al., 2021). On the other hand, non-magnetic additives tend to reduce the MR effect, even though they can solve the sedimentation problem. Thus, the addition of magnetic materials as an additive is an efficient method to increase the sedimentation stability and MR effect of suspensions (Hajalilou et al., 2016; Zhang et al., 2020). Ngatu and Wereley (2007) added iron nanowires of diameter ranging from 5 to 250 nm to the MR fluid to improve the MR effect and the dispersion stability. Han et al. (2020) used hollow-Fe3O4 particles fabricated using a solvothermal process as an additive to reduce the sedimentation problem and enhance MR properties of CI-based MR fluid. Recently, Jang et al. (2015) and Kim et al. (2017) added hard-magnetic particles, such as γ-Fe2O3 and CrO2, respectively, to CI-based MR fluids and reported improvement in both the MR behavior and suspension stability.

Barium ferrite (BaFe12O19) (BF) with a non-circular plate-like structure and the perpendicular magnetic moment has attracted considerable interest as a high-performance permanent magnet because of its high magnetocrystalline anisotropy, high Curie point, relatively high magnetic saturation (Ms) value and coercive force, and superior chemical stability and corrosion resistance (Choi et al., 2000; Wei et al., 2020). Furthermore, non-circular hexagonal plate-like particles have a slower sedimentation rate than spherical or rod-like particles, such as γ-Fe2O3 and CrO2. These hard magnetic particles that have a special shape could increase the Ms value of the CI particles, which is related directly to improving the MR efficiency of MR suspensions. In addition, hard magnetic particles are better able to adhere to the surface of CI particles as an additive, thus increasing the strength of the chain and the tendency to reform broken chain structures during operation. Therefore, BF particles were newly introduced as an additive, and their sedimentation stability was expected to be superior to previously reported additives.

This study examined the sedimentation stability and MR performance of MR suspensions by adding nano-sized BF particles as an additive between micron-sized CI particles. CI-based MR fluids were fabricated using silicone oil, and the BF additive was added to examine the effect of the additive. Their MR behaviors were measured using a rotation rheometer, and the sedimentation stability was recorded using a Turbiscan (MA2000, Formulaction, Toulouse, France).

The CI [Badische Anilin-und-Soda-Fabrik (BASF), standard CM grade, particle density: 7.90 g/cc, diameter: about 4 μm, Germany] microspheres with their Ms of 209.5 emu/g and silicone oil (Shin-Etsu Chemical Co., Ltd., KF-96, viscosity: 100 cSt, Japan) were used as a dispersed and a continuous part of the MR fluids, respectively. The hard-magnetic BF (density: 5.28 g/cm3, Toda Co., Tokyo, Japan) particle was introduced as an additive material. The physical properties of the BF are well-reported with its diameter of 0.13 μm and the aspect ratio of 0.1, corresponding to its thickness of 0.013 μm (Kwon et al., 1997; Choi et al., 2000).

Barium ferrite nanoparticles, used as an additive, were prepared by sonication for 1 h and dried. Three different MR fluids were prepared. The CI microparticle-based MR fluid without the additive was made by suspending 50 wt% of CI microspheres in silicone oil (50 wt%). To examine the additive effect, a 0.5 wt% concentration of BF particles with Ms of 63.8 emu/g was mixed in silicone oil (49.5 wt%), and CI microparticles (50 wt%) were then added. Furthermore, the pure BF nanoparticle-based MR fluid (50 wt%) was also prepared for comparison. The MR fluid with the additive is called a CI/BF-based MR fluid. A vortex (IKA, Korea. Ltd., GENIUS3) and sonicator (HWASHIN CO., Ltd., Powersonic 410) were used to disperse the magnetic particles uniformly during sample preparation.

The surface morphologies of the CI, BF, and CI/BF systems were observed using a high-resolution scanning electron microscopy (HR-SEM, SU-8010, Hitachi, Tokyo, Japan). The dispersion stability of the MR fluids was investigated using a Turbiscan (MA2000, Formulaction, Toulouse, France), and the static magnetic characteristics of the magnetic particles were examined by making them in a powder form through a vibrating sample magnetometer (VSM) (7307, Lakeshore, LA, USA). The particle densities were measured using a gas pycnometer (AccuPyc 1330, Micromeritics, Norcross, GA, USA). Their MR properties were examined using a rotation rheometer (MCR 302, Anton-Paar, Graz, Austria) attached to a device for applying the magnetic field.

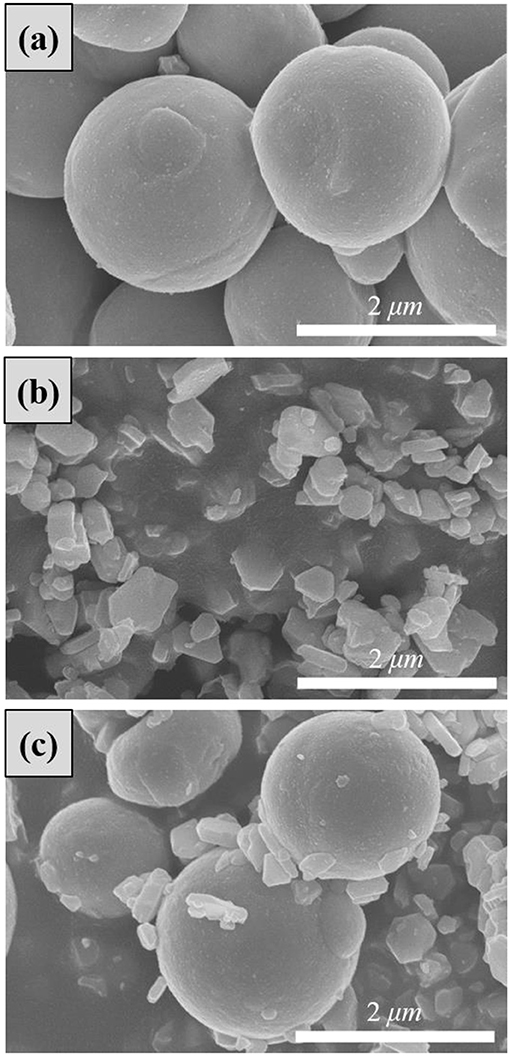

Figures 1a–c present SEM images of pristine CI, BF, and their mixtures, respectively. Figure 1a shows the pristine CI with a spherical shape and a smooth surface. The mean diameter of the pure CI particle was ~3 μm. As shown in Figure 1b, BaFe12O19 had a hexagonal plate-like structure with a mean size of 700 nm. Figure 1c exhibited a mixture of pure CI particles and a small amount of BaFe12O19 particles. Hexagonal plate-like BaFe12O19 particles were attached to the space between pure CI particles. Their hard-magnetic properties, nano size, and unique structure were expected to enhance the MR efficiency and suspension stability by occupying the space between the CI microspheres.

Figure 1. Scanning electron microscopy images of (a) pure carbonyl iron (CI) microparticles, (b) BaFe12O19 nanoparticles, and (c) CI/ BaFe12O19 mixture.

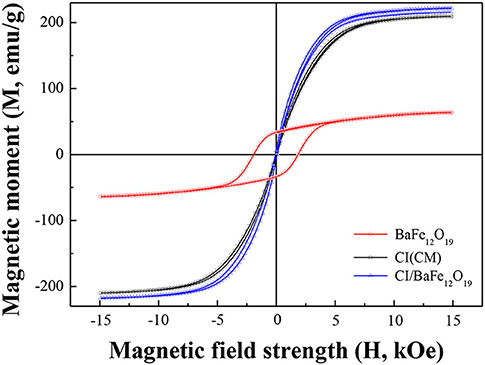

The static magnetic characteristics of the pristine CI, BF, and CI/ BF mixture particles were measured in the powder form via VSM, with an applied H from −15 to 15 kOe at room temperature. Figure 2 shows the magnetic moment as a function of H, in which the measured Ms and coercivity (Hc) of the BF particles were 63.8 emu/g and 1.74 kOe, respectively (Ko et al., 2009). When the 0.5 wt.% of BF particles were added to pure CI, the Ms value of the CI/BF mixture particles appeared to be slightly increased. Overall, BF particles, which exhibit hard-magnetic properties with magnetic hysteresis, could improve the MR performance in the magnetic response of a CI microparticle-based MR fluid, as shown in Figure 2 (Moon et al., 2016).

Figure 2. Vibrating sample magnetometer data of pure carbonyl iron (CI) (CM grade), BaFe12O19, and CI/BaFe12O19 0.5 wt% mixture.

Two types of MR fluids were used to measure the MR property. One contained 50 wt.% pure CI microparticles dispersed in 100 cS of silicone oil, and the other contained 0.5 wt.% BaFe12O19 particles added at the same ratio as the CI microparticles in the same silicone oil. The measurements were taken using a parallel-plate rotation rheometer under a controlled shear rate mode. For each test, a certain amount of MR suspensions was dropped in the gap of the parallel-plate geometry device and the base plate.

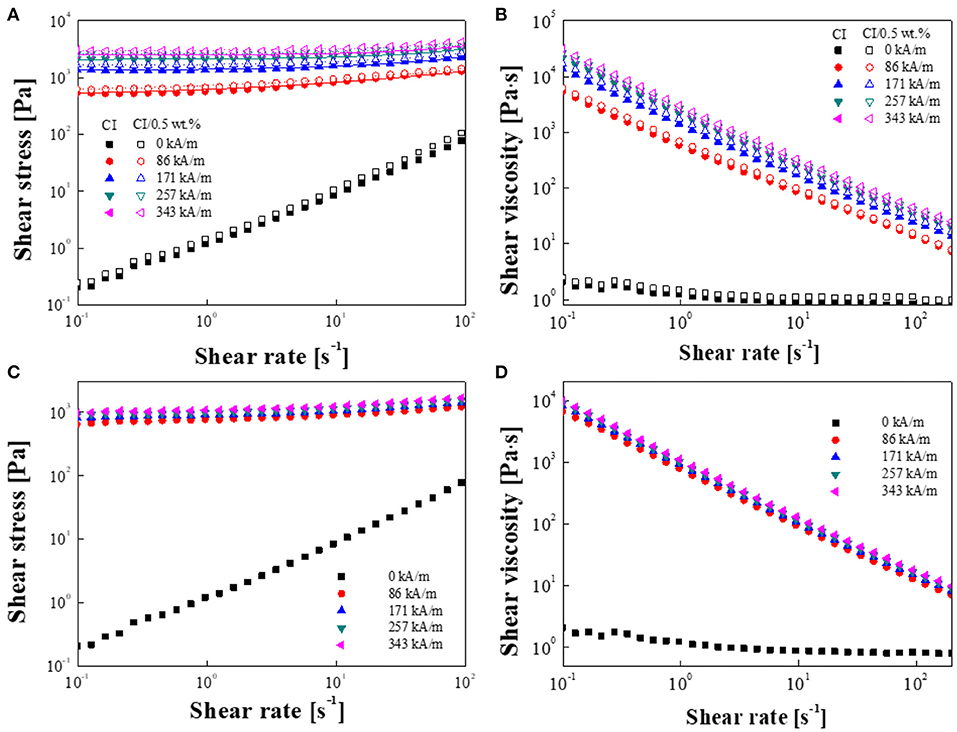

The flow tests were carried out at shear rates in the range of 0.1 to 200 s−1 under an applied H of 0 to 343 kA/m. Figure 3 shows the shear stress τ (a, c) and shear viscosity (b, d) data as a function of the shear rate () under various H for all of the three MR fluids, in which the closed and open symbols refer to an MR fluid without and with BF additive, respectively. According to Figures 3A,C, τ of the three MR suspensions increased linearly with increasing shear rate without an applied H, indicating that three MR fluids exhibited Newtonian fluid-like characteristics. On the other hand, the non-Newtonian fluid property of non-linearity between τ and , when exposed to external H, was prominent in the three MR samples. This is because the chain-like structure of the magnetized particles was built up by strong magnetic dipole–dipole (D–D) interactions (Zhang and Widom, 1995). In particular, at each H, a CI-based MR fluid containing the BF additive showed higher τ values than those without BF nanoparticles over the entire shear rate range. By applying H, hexagonal plate-like structured BF particles, which were relatively smaller than CI microparticles, filled the space between the CI microparticles. These structural characteristics promoted the response to the magnetic field, forming stronger chain structures and improving the MR performance. The 0.5 wt% additive concentration was used because too much additive in the MR fluid resulted in a significant increase in shear viscosity without increasing the MR performance (Iglesias et al., 2012; Moon et al., 2016). In addition, the pure BF-based MR fluid has relatively less shear stress and shear viscosity, which can also be predicted and explained with its low Ms value and hard-magnetic property.

Figure 3. (A) Shear stress and (B) shear viscosity of CI/ BaFe12O19 mixture-based MR fluid (open symbol) and pure carbonyl iron (CI)-based magnetorheological (MR) fluid (closed symbol), shear stress (C), and shear viscosity (D) of pure barium ferrite (BF)-based MR fluid as a function of shear rate under various magnetic field strengths.

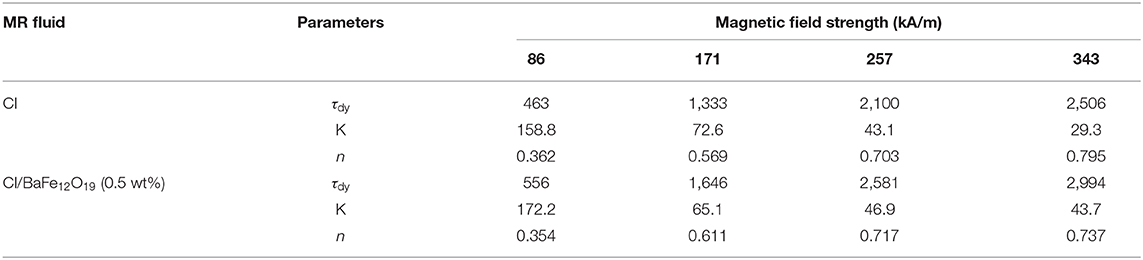

On the other hand, the flow behaviors of the two MR suspensions were fitted using the Herschel–Bulkley model to analyze typical steady-shear behavior. This model was expressed as follows:

where τy is the yield stress, depending on the applied H, shape, and particle concentration, and is the shear rate (Choi et al., 2001; Jang et al., 2015). Both K and n are denoted as the consistency index and power-law exponent, respectively. The τ curves of pristine CI and CI/BF-based MR suspensions were fitted very well to the Herschel–Bulkley Equation (1) at each magnetic field strength. Figure 3A presents two MR fluids as a solid line and dotted line (Cvek et al., 2016). Table 1 lists the optimal parameters obtained from Equation (1), showing the Herschel–Bulkley model.

Table 1. The optimal parameters in Herschel–Bulkley (HB) model equation obtained from shear stress data.

Similarly, the shear viscosity graphs for both MR fluids showed the same behavior over the shear rates at various H, as presented in Figure 3B. The viscosities of both MR fluids increased with increasing H and exhibited shear-thinning behavior; hence, the viscosity decreased with increasing shear rate. Note that the increase in shear viscosity had an important influence on the MR characteristics (Hong et al., 2013). As H increased, the magnetization of the CI microspheres also increased consistently, interfering with the free movement of the particles due to chain formation, thereby increasing the shear viscosity of the MR suspension. While the magnetic D–D interactions between the magnetic microspheres are parallel to the applied stimuli direction, the flow is perpendicular to the stimuli direction. Therefore, the shear viscosity is represented as apparent shear-thinning behavior, resulting from the shear-deformation of the chain structure over the entire range (Hong et al., 2013; Wang et al., 2019).

Without H, the CI/BF-based MR suspension showed slightly larger shear viscosity than the MR suspension without the BF nanoparticles because of the reduced hydrodynamic volume by the added BF particle concentration. Under an applied H, the shear viscosity of the MR suspension containing the BF additive was higher than that without BF nanoparticles. This suggests that the strength of the chain structure was increased by the added hard magnetic nanoparticles, and the shear stress was increased.

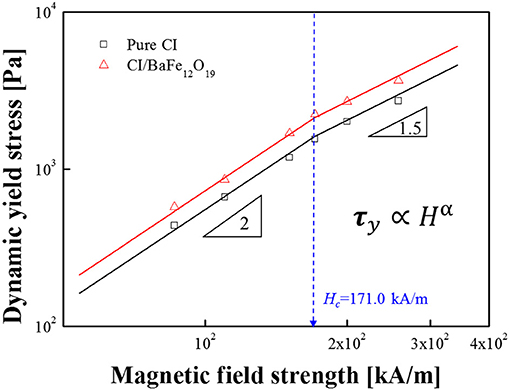

Figure 4 shows the relationship between the τy and H for both CI microparticles and CI/BF-based MR suspensions. Dynamic τy, which is one of the important rheological parameters, was acquired by extrapolating the τ at zero limit for each H. In general, the τy is expressed by the power-law of H, as given in Equation (2):

The magnetic-field-dependent τy can be divided into two parts depending on the applied H (Ginder et al., 1996). At a low H, τy is proportional to H2, following the polarization model due to the attraction force between the magnetized particles (Bossis et al., 1997, 2019). When the magnetic field strength increases to an intermediate value, τy will change to H3/2, which is similar to the conduction model (Choi et al., 2001). This can be considered an increase in localized magnetization saturation that can decrease the MR performance. At the intermediate value, where local saturation becomes dominant, the equation for the τy is given as follows:

where φ is the magnetic particle volume fraction and μ0 is the free space permeability (Genç and Phulé, 2002). When a sufficient H was applied, all of the particles reached full saturation and became an independent relationship with H.

To analyze the flow effect for MR fluids more accurately and to determine the relationship between τy and H, the universal yield stress equation was proposed in the presence of a critical H (Hc) as follows (Fang et al., 2009):

where α is dependent on the susceptibility of the MR fluid, φ, and particle shape (Ginder et al., 1996; Bossis et al., 2019). Hc is a boundary value dividing the τy behavior of the MR suspensions, in which τy represents two limiting values with respect to H as follows (Chae et al., 2015):

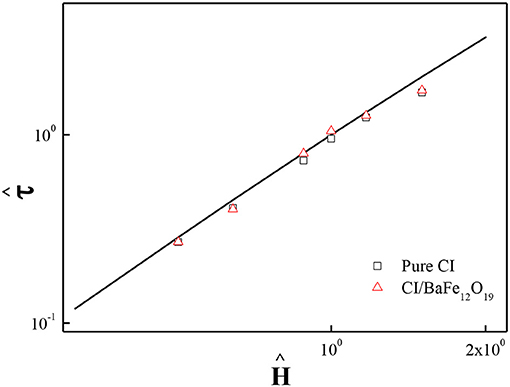

Figure 4 shows the relationship between τy and H for both MR suspensions. The Hc values of both the CI- and CI/BF-based MR fluids were 171 kA m−1. A universal yield stress function was obtained using the following: Hc and τy (Hc) = 0.762αH,

The results were fitted onto a single line using this generalized universal yield stress function, as demonstrated in Figure 5.

Figure 4. Dynamic yield stress as a function of magnetic field strength for both pure carbonyl iron (CI)-(square symbol) and CI/BaFe12O19 mixture-based magnetorheological (MR) fluids (triangle symbol).

Figure 5. Universal plot of for pure carbonyl iron (CI; square symbol) and CI/BaFe12O19 mixture-based magnetorheological (MR) fluids (triangle symbol). The solid line is obtained using Equation (7).

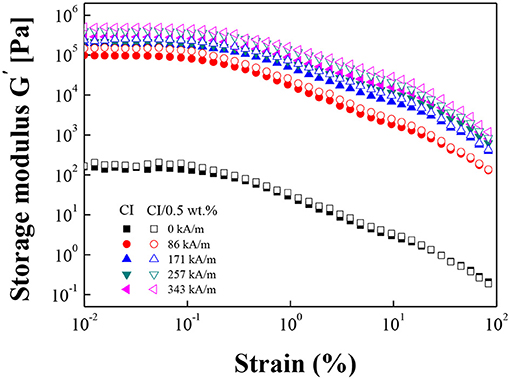

The dynamic oscillation measurements of the MR samples include both the strain amplitude and frequency sweep tests to examine the viscoelastic characteristics of both MR suspensions with and without BF nanoparticles under different H up to 343 kA/m. Figure 6 presents data from the strain amplitude sweep measurements in the strain value from 10−2 to 102 at a fixed angular frequency (ω). This test was carried out to select the linear viscoelastic region (γLVE) before performing the frequency sweep test. Overall, the storage modulus (G′) of the CI/BF MR fluid was slightly larger than that of the MR fluid without an additive in the entire strain range, suggesting that the fluid rigidity was enhanced by the BF additive (Wei et al., 2010). In particular, the G′ of both MR suspensions showed a steady plateau region up to 3 × 10−2 %, which was called the LVE region. When the strain exceeded a certain level, the storage modulus decreased sharply with increasing strain. This behavior is called the Payne effect, and it was attributed to an irreversible change in the microstructure of the material because of a sufficiently large strain (Gong et al., 2012).

Figure 6. Strain amplitude sweep test for pure carbonyl iron (CI; closed symbol) and CI/BaFe12O19 mixture–(open symbol) based magnetorheological (MR) fluids under various magnetic field strengths.

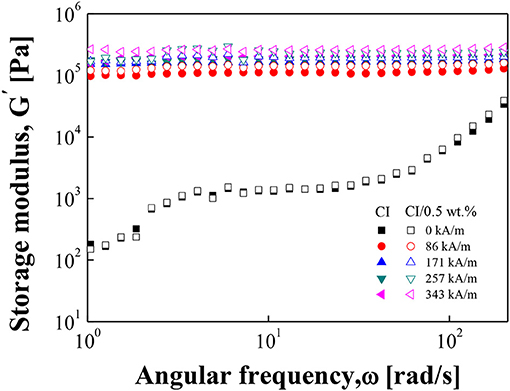

The frequency sweep test was taken with a given strain of 3 × 10−2%, as determined by the previous amplitude sweep test. Figure 7 presents G′ as a function of ω at a constant strain for two MR fluids. When H was not applied, the G′ of both MR fluids was not large enough, and fluid-like characteristics were observed. When the H was applied, the G' of both MR fluids showed a stable region over the entire ω, and the value increased gradually with increasing H. This suggests that the two MR fluids transitioned from a fluid-like state to a solid-like state under the influence of H, and a stronger chain structure was formed as H increased. Furthermore, when comparing the two MR fluids over the entire frequency range, the G′ of the MR fluid containing the additive was larger than that of the fluid without an additive.

Figure 7. Angular frequency sweep test for pure carbonyl iron (CI; closed symbol) and CI/BaFe12O19 mixture–(open symbol) based MR fluids at constant strain (0.03%).

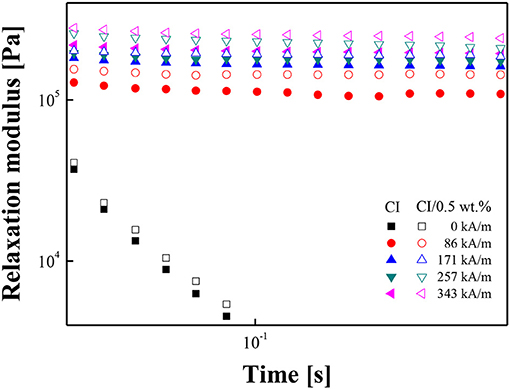

As shown in Figure 8, the solid-like behaviors of the two MR fluids can be interpreted more closely by the Schwarzl equation for deriving their stress relaxation modulus, G(t), which was calculated using the G′ and loss (G″) modulus values obtained in the frequency sweep experiment shown in Figure 7. The Schwarzl equation is expressed as Equation 8 below (Chae et al., 2015):

The G(t) of both MR suspensions showed steady plateau behaviors under an applied magnetic field, unlike G(t) in the absence of a magnetic field over time. In other words, the relaxation feature did not appear as a function of time (Figure 8). Thus, the stable solid-like behavior of both MR fluids was studied as a function of time because of the strongly increased interactions between the CI particles under an external H.

Figure 8. Relaxation modulus of the pure carbonyl iron (CI; closed symbol) and CI/BaFe12O19 (open symbol) -based MR fluids as a function of time.

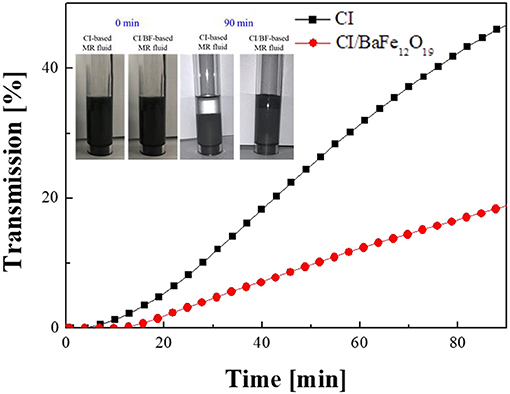

As shown in Figure 9, the sedimentation stability of both MR fluids was investigated using Turbiscan in cylindrical glass cells, each containing a 40-mm MR fluid. The measurements were carried out by illuminating a light source from the bottom to the top at regular intervals (Buron et al., 2004). From the measurements, the transmission was plotted as a function of time (Upadhyay et al., 2013). Initially, the transmission of both MR fluids was close to zero. The absence of transmitted light indicates that the scattered light was not transmitted through the uniformly suspended particles in the MR fluid. After a few minutes, the transmission of a pristine CI-based MR fluid increased faster than that of a fluid containing the BaFe12O19 additive for the same time. This is because pure CI-based MR fluid particles aggregated more easily than the CI/BaFe12O19-based MR fluid particles and precipitated quickly to the bottom of the cell over time, showing slightly higher transmission. On the other hand, the CI/BaFe12O19-based MR fluid exhibited a low transmission due to the additive, showing a stable and improved dispersion state. This was attributed to the reduced particle density from the BaFe12O19 nanoparticles attached between the CI particles. The distance between the centers of the two magnetic particles determined the interaction between the particles, and for the two magnetic plates, this distance is the thickness of the particles. However, this value is significantly less than that of two spherical or elongated particles (Lisjak and Mertelj, 2018). As a result, the D–D interactions between two plate-like particles are strong, resulting in better stability of the MR suspension. Therefore, the addition of BaFe12O19 magnetic particles improved the sedimentation stability compared with the pristine CI-based MR suspension.

Figure 9. Sedimentation stability curve verse time for pure carbonyl iron (CI; square symbol) and CI/BaFe12O19 mixture-based MR fluids (circle symbol).

This study examined the effects of a hard-magnetic BF additive on a CI-based MR fluid. SEM and TEM revealed the morphology of the BF nanoparticles adsorbed in empty spaces between CI microspheres. The magnetic characteristics of the BF nanoparticles were confirmed using VSM. Two types of MR fluids with and without the BaFe12O19 additive in CI-based MR fluids were prepared to compare the rheological behavior and sedimentation stability under various H. The flow behavior of both MR fluids followed a typical Herschel–Bulkley model when an external H was applied, and a CI-based MR fluid with the BaFe12O19 additive exhibited improved MR characteristics, such as the yield stress, shear viscosity, and dynamic modulus with increasing H. Furthermore, the sedimentation stability of the CI-based MR fluid with the BaFe12O19 additive was improved remarkably by the reduced particle density due to the effect of the additive in the space between CI microspheres. Based on these results, synergistic effects were demonstrated to improve the MR properties and sedimentation stability of the ferromagnetic BaFe12O19 additive for a pure CI-based MR fluid.

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

HJC and HSJ designed the experiments. HSJ conducted the measurements. HSJ and QL analyzed the experimental data. HJC acquired the funding. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was supported by the National Research Foundation of Korea (2021R1A4A2001403).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Ahamed, R., Ferdaus, M. M., and Li, Y. (2016). Advancement in energy harvesting magneto-rheological fluid damper: a review. Korea Aust. Rheol. J. 28, 355–379. doi: 10.1007/s13367-016-0035-2

Aruna, M. N., Rahman, M. R., Joladarashi, S., and Kumar, H. (2019). Influence of additives on the synthesis of carbonyl iron suspension on rheological and sedimentation properties of magnetorheological (MR) fluids. Mater. Res. Express 6:086105. doi: 10.1088/2053-1591/ab1e03

Aruna, M. N., Rahman, M. R., Joladarashi, S., and Kumar, H. (2020). Investigation of sedimentation, rheological, and damping force characteristics of carbonyl iron magnetorheological fluid with/without additives. J. Braz. Soc. Mech. Sci. Eng. 42:228. doi: 10.1007/s40430-020-02322-5

Ashtiani, M., Hashemabadi, S. H., and Ghaffari, A. (2015). A review on the magnetorheological fluid preparation and stabilization. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 374, 716–730. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2014.09.020

Bae, D. H., Choi, H. J., Choi, K., Nam, J. D., Islam, M. S., and Kao, N. (2017). Microcrystalline cellulose added carbonyl iron suspension and its magnetorheology. Colloids Surf. A 514, 161–167. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.11.052

Bombard, A. J. F., Alcântara, M. R., Knobel, M., and Volpe, P. L. O. (2005). Experimental study of mr suspensions of carbonyl iron powders with different particle sizes. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 19, 1332–1338. doi: 10.1142/S0217979205030268

Bossis, G., Lemaire, E., Volkova, O., and Clercx, H. (1997). Yield stress in magnetorheological and electrorheological fluids: a comparison between microscopic and macroscopic structural models. J. Rheol. 41, 687–704. doi: 10.1122/1.550838

Bossis, G., Volkova, O., Grasselli, Y., and Ciffreo, A. (2019). The role of volume fraction and additives on the rheology of suspensions of micron sized iron particles. Front. Mater. 6:4. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2019.00004

Buron, H., Mengual, O., Meunier, G., Cayr,é, I., and Snabre, P. (2004). Optical characterization of concentrated dispersions: applications to laboratory analyses and on-line process monitoring and control. Polym. Int. 53, 1205–1209. doi: 10.1002/pi.1231

Chae, H. S., Piao, S. H., Maity, A., and Choi, H. J. (2015). Additive role of attapulgite nanoclay on carbonyl iron-based magnetorheological suspension. Colloid Polym. Sci. 293, 89–95. doi: 10.1007/s00396-014-3389-3

Choi, H. J., Cho, M. S., Kim, J. W., Kim, C. A., and Jhon, M. S. (2001). A yield stress scaling function for electrorheological fluids. Appl. Phys. Lett. 78, 3806–3808. doi: 10.1063/1.1379058

Choi, H. J., Kwon, T. M., and Jhon, M. S. (2000). Effects of shear rate and particle concentration on rheological properties of magnetic particle suspensions. J. Mater. Sci. 35, 889–894. doi: 10.1023/A:1004742223080

Choi, S. B., Song, H., Lee, H., Lim, S., Kim, J., and Choi, H. J. (2003). Vibration control of a passenger vehicle featuring magnetorheological engine mounts. Int. J. Veh. Des. 33, 2–16. doi: 10.1504/IJVD.2003.003567

Cvek, M., Mrlik, M., and Pavlinek, V. (2016). A rheological evaluation of steady shear magnetorheological flow behavior using three-parameter viscoplastic models. J. Rheol. 60, 687–694. doi: 10.1122/1.4954249

Fang, F. F., and Choi, H. J. (2008). Noncovalent self-assembly of carbon nanotube wrapped carbonyl iron particles and their magnetorheology. J. Appl. Phys. 103:07A301. doi: 10.1063/1.2829019

Fang, F. F., Choi, H. J., and Jhon, M. S. (2009). Magnetorheology of soft magnetic carbonyl iron suspension with single-walled carbon nanotube additive and its yield stress scaling function. Colloids Surf. A 351, 46–51. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.09.032

Genç, S., and Phulé, P. P. (2002). Rheological properties of magnetorheological fluids. Smart Mater. Struct. 11, 140–146. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/11/1/316

Ginder, J. M., Davis, L. C., and Elie, L. D. (1996). Rheology of magnetorheological fluids: models and measurements. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 10, 3293–3303. doi: 10.1142/S0217979296001744

Gong, X., Xu, Y., Xuan, S., Guo, C., Zong, L., and Jiang, W. (2012). The investigation on the nonlinearity of plasticine-like magnetorheological material under oscillatory shear rheometry. J. Rheol. 56, 1375–1391. doi: 10.1122/1.4739263

Gopinath, B., Sathishkumar, G. K., Karthik, P., Martin Charles, M., Ashok, K. G., Ibrahim, M., et al. (2021). A systematic study of the impact of additives on structural and mechanical properties of Magnetorheological fluids. Mater. Today Proc. 37, 1721–1728. doi: 10.1016/j.matpr.2020.07.246

Hajalilou, A., Mazlan, S. A., and Shila, S. T. (2016). Magnetic carbonyl iron suspension with Ni-Zn ferrite additive and its magnetorheological properties. Mater. Lett. 181, 196–199. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2016.06.041

Han, J. K., Lee, J. Y., and Choi, H. J. (2019). Rheological effect of Zn-doped ferrite nanoparticle additive with enhanced magnetism on micro-spherical carbonyl iron based magnetorheological suspension. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 571, 168–173. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.03.084

Han, W. J., An, J. S., and Choi, H. J. (2020). Enhanced magnetorheological characteristics of hollow magnetite nanoparticle-carbonyl iron microsphere suspension. Smart Mater. Struct. 29:055022. doi: 10.1088/1361-665X/ab7f43

Hong, C. H., Liu, Y. D., and Choi, H. J. (2013). Carbonyl iron suspension with halloysite additive and its magnetorheology. Appl. Clay Sci. 80–81, 366–371. doi: 10.1016/j.clay.2013.06.033

Iglesias, G. R., López-López, M. T., Durán, J. D. G., González-Caballero, F., and Delgado, A. V. (2012). Dynamic characterization of extremely bidisperse magnetorheological fluids. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 377, 153–159. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.03.077

Jang, D. S., Liu, Y. D., Kim, J. H., and Choi, H. J. (2015). Enhanced magnetorheology of soft magnetic carbonyl iron suspension with hard magnetic γ-Fe2O3 nanoparticle additive. Colloid Polym. Sci. 293, 641–647. doi: 10.1007/s00396-014-3475-6

Jang, I. B., Kim, H. B., Lee, J. Y., You, J. L., Choi, H. J., and Jhon, M. S. (2005). Role of organic coating on carbonyl iron suspended particles in magnetorheological fluids. J. Appl. Phys. 97:10Q912. doi: 10.1063/1.1853835

Kim, M. H., Choi, K., Nam, J. D., and Choi, H. J. (2017). Enhanced magnetorheological response of magnetic chromium dioxide nanoparticle added carbonyl iron suspension. Smart Mater. Struct. 26:095006. doi: 10.1088/1361-665X/aa7cb9

Ko, S. W., Yang, M. S., and Choi, H. J. (2009). Adsorption of polymer coated magnetite composite particles onto carbon nanotubes and their magnetorheology. Mater. Lett. 63, 861–863. doi: 10.1016/j.matlet.2009.01.037

Kordonskii, V. I., Demchuk, S. A., and Kuz'min, V. A. (1999). Viscoelastic properties of magnetorheological fluids. J. Eng. Phys. Thermophys. 72, 841–844. doi: 10.1007/BF02699403

Kwon, T. M., Jhon, M. S., and Choi, H. J. (1997). Rheological study of magnetic particle suspensions. Mater. Chem. Phys. 49, 225–228. doi: 10.1016/S0254-0584(97)80168-X

Li, W. H., Du, H., and Guo, N. Q. (2004). Dynamic behavior of MR suspensions at moderate flux densities. Mater. Sci. Eng. A 371, 9–15. doi: 10.1016/S0921-5093(02)00932-2

Li, W. H., Yao, G. Z., Chen, G., Yeo, S. H., and Yap, F. F. (2000). Testing and steady state modeling of a linear MR damper under sinusoidal loading. Smart Mater. Struct. 9, 95–102. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/9/1/310

Lisjak, D., and Mertelj, A. (2018). Anisotropic magnetic nanoparticles: a review of their properties, syntheses and potential applications. Prog. Mater. Sci. 95, 286–328. doi: 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2018.03.003

Liu, J., Wang, X., Tang, X., Hong, R., Wang, Y., and Feng, W. (2015). Preparation and characterization of carbonyl iron/strontium hexaferrite magnetorheological fluids. Particuology 22, 134–144. doi: 10.1016/j.partic.2014.04.021

López-López, M. T., Gómez-Ramírez, A., Durán, J. D. G., and González-Caballero, F. (2008). Preparation and characterization of iron-based magnetorheological fluids stabilized by addition of organoclay particles. Langmuir 24, 7076–7084. doi: 10.1021/la703519p

Machovsky, M., Mrlik, M., Kuritka, I., Pavlinek, V., and Babayan, V. (2014). Novel synthesis of core–shell urchin-like ZnO coated carbonyl iron microparticles and their magnetorheological activity. RSC Adv. 4, 996–1003. doi: 10.1039/C3RA44982C

Mao, M., Hu, W., Choi, Y. T., Wereley, N., Browne, A. L., and Ulicny, J. (2014). Experimental validation of a magnetorheological energy absorber design analysis. J. Intell. Mater. Syst. Struct. 25, 352–363. doi: 10.1177/1045389X13494934

Maurya, C. S., and Sarkar, S. (2020). Effect of Fe3O4 nanoparticles on magnetorheological properties of flake-shaped carbonyl iron water-based suspension. IEEE Trans. Magn. 56, 1–8. doi: 10.1109/TMAG.2020.3031239

Moon, I. J., Kim, M. W., Choi, H. J., Kim, N., and You, C.-Y. (2016). Fabrication of dopamine grafted polyaniline/carbonyl iron core-shell typed microspheres and their magnetorheology. Colloids Surf. A 500, 137–145. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2016.04.037

Ngatu, G. T., and Wereley, N. M. (2007). High versus low field viscometric characterization of bidisperse mr fluids. Int. J. Mod. Phys. B 21, 4922–4928. doi: 10.1142/S0217979207045840

Qiao, X., Zhou, J., Binks, B. P., Gong, X., and Sun, K. (2012). Magnetorheological behavior of Pickering emulsions stabilized by surface-modified Fe3O4 nanoparticles. Colloids Surf. A 412, 20–28. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2012.06.026

Sedlačík, M., Pavlínek, V., Sáha, P., Švrčinová, P., Filip, P., and Stejskal, J. (2010). Rheological properties of magnetorheological suspensions based on core–shell structured polyaniline-coated carbonyl iron particles. Smart Mater. Struct. 19:115008. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/19/11/115008

Susan-Resiga, D., Bica, D., and Vékás, L. (2010). Flow behaviour of extremely bidisperse magnetizable fluids. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 322, 3166–3172. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2010.05.055

Svåsand, E., Kristiansen, K. D. L., Martinsen, Ø. G., Helgesen, G., Grimnes, S., et al. (2009). Behavior of carbon cone particle dispersions in electric and magnetic fields. Colloids Surf. A 339, 211–216. doi: 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2009.02.025

Upadhyay, R. V., Laherisheth, Z., and Shah, K. (2013). Rheological properties of soft magnetic flake shaped iron particle based magnetorheological fluid in dynamic mode. Smart Mater. Struct. 23:015002. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/23/1/015002

Vasiliev, V. G., Sheremetyeva, N. A., Buzin, M. I., Turenko, D. V., Papkov, V. S., Klepikov, I. A., et al. (2016). Magnetorheological fluids based on a hyperbranched polycarbosilane matrix and iron microparticles. Smart Mater. Struct. 25:055016. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/25/5/055016

Vicente, J. D., López-López, M. T., González-Caballero, F., and Durán, J. D. G. (2003). Rheological study of the stabilization of magnetizable colloidal suspensions by addition of silica nanoparticles. J. Rheol. 47, 1093–1109. doi: 10.1122/1.1595094

Wang, H., Li, Y., Zhang, G., and Wang, J. (2019). Effect of temperature on rheological properties of lithium-based magnetorheological grease. Smart Mater. Struct. 28:035002. doi: 10.1088/1361-665X/aaf32b

Wei, B., Gong, X., Jiang, W., Qin, L., and Fan, Y. (2010). Study on the properties of magnetorheological gel based on polyurethane. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 118, 2765–2771. doi: 10.1002/app.32688

Wei, X., Liu, Y., Zhao, D., Mao, X., Jiang, W., and Ge, S. S. (2020). Net-shaped barium and strontium ferrites by 3D printing with enhancedmagnetic performance from milled powders. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 493:165664. doi: 10.1016/j.jmmm.2019.165664

Yang, T.-H., Kwon, H.-J., Lee, S. S., An, J., Koo, J.-H., Kim, S.-Y., et al. (2010). Development of a miniature tunable stiffness display using MR fluids for haptic application. Sens. Actuat. A Phys. 163, 180–190. doi: 10.1016/j.sna.2010.07.004

Zhang, H., and Widom, M. (1995). Field-induced forces in colloidal particle chains. Phys. Rev. E 51, 2099–2103. doi: 10.1103/PhysRevE.51.2099

Keywords: carbonyl iron, barium ferrite, magnetorheological, additive, sedimentation

Citation: Jang HS, Lu Q and Choi HJ (2021) Enhanced Magnetorheological Performance of Carbonyl Iron Suspension Added With Barium Ferrite Nanoparticle. Front. Mater. 8:667685. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2021.667685

Received: 14 February 2021; Accepted: 19 March 2021;

Published: 20 April 2021.

Edited by:

Jinbo Wu, Shanghai University, ChinaReviewed by:

Yancheng Li, University of Technology Sydney, AustraliaCopyright © 2021 Jang, Lu and Choi. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Hyoung Jin Choi, aGpjaG9pQGluaGEuYWMua3I=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.