- 1College of Engineering, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, China

- 2School of Mechanical Engineering, Hubei University of Arts and Science, Xiangyang, China

- 3USC-SJTU Institute of Cultural and Creative Industry, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China

- 4Xingzhi College, Zhejiang Normal University, Jinhua, China

- 5Department of Orthopedics, Shengli Oilfield Central Hospital, Dongying, China

Photothermal therapy is an efficient cancer treatment method. The development of nanoagents with high biocompatibility and a near-infrared (NIR) photoabsorption band is a prerequisite to the success of this method. However, the therapeutic efficiency of photothermal therapy is rather limited because most nanoagents have a low photothermal conversion efficiency. In this study, we aimed to develop CuFeS2 nanoassemblies with an excellent photothermal effect using the liquid-solid-solution method. The CuFeS2 nanoassemblies we developed are composed of ultrasmall CuFeS2 nanoparticles with an average size of 5 nm, which have strong NIR photoabsorption. Under NIR laser illumination at 808 nm at the output power intensity of 1.0 W cm–2, the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies could rapidly convert NIR light into heat, achieving a high photothermal conversion efficiency of 46.8%. When K7M2 cells were incubated with the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies and then exposed to irradiation, their viability decreased progressively as the concentration of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies increased. Furthermore, a concentration of 40 ppm of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies was lethal to the cells. Importantly, after an intratumoral injection of 40 ppm of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies, the tumor showed a high contrast in the thermal image after laser irradiation, and tumor cells with condensed nuclei and a loss of cell morphology could be thermally ablated. Therefore, the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies we synthesized have a high biocompatibility and robust photothermal effect and can, thus, be utilized as a novel and efficient photothermal agent for tumor therapy.

Introduction

Photothermal therapy, which utilizes ex vivo near-infrared (NIR) lasers to irradiate photothermal materials within a tumor to generate heat (>45°C) so that tumor cells can be thermally ablated, is an emerging treatment modality for killing cancer cells with high therapeutic efficiency (Zou et al., 2016; Vankayala and Hwang, 2018). The use of photothermal materials with broad and strong photoabsorption in the NIR region (650–1100 nm) is essential for successful photothermal therapy. Photothermal therapy using NIR lasers attracts increasing attention from researchers all over the world due to its safety and high tissue-penetration capacity compared to visible and ultraviolet light. Up to date, several kinds of photothermal materials have been investigated and used for treating malignant tumors, including organic nanoparticles, such as polypyrrole nanoparticles (Zha et al., 2013) and melanin nanoparticles (Liu et al., 2013), reduced graphene oxide nanosheets (Yang et al., 2010; Robinson et al., 2011) and carbon dots (Ge et al., 2015), metal nanostructures (Au nanorods (Dreaden et al., 2011), Pd nanosheets (Huang et al., 2011), and Bi nanoparticles (Yu et al., 2018b), and semiconductor nanomaterials, such as mental sulfides and oxide-based nanocrystals (Tian et al., 2011b; Huang et al., 2017; Yu et al., 2017, 2018a). In particular, a number of semiconductor nanomaterials have received tremendous attention due to their tunable composites, easy synthesis, and strong and stable photothermal effect. For example, CuS-based photothermal nanomaterials have been reported with varied ratios of Cu/S and different morphologies, such as CuS nanodots (Li et al., 2010), flower-like CuS superstructures (Tian et al., 2011b), Cu9S5 nanocrystals (Tian et al., 2011a), and Cu7.2S4 nanocrystals (Ling et al., 2014). These photothermal nanomaterials have exhibited strong photothermal effects under the irradiation of NIR lasers at different wavelengths (808, 915, 980, and 1064 nm). However, the application of semiconductor nanomaterials is rather hindered because of their unsatisfactory biocompatibility and hydrophobic surface. Thus, it is still necessary to develop semiconductor nanomaterials with high photothermal conversion efficiency and biocompatibility for photothermal therapy of malignant tumors.

Most recent research has increasingly focused on ternary nanostructures instead of metal mono- and dichalcogenides. Ternary nanostructures are capable of strong photoabsorption and also have a tunable feature for adjusting their intrinsic photoabsorption band and adding imaging properties, which can be employed for multimodal imaging and enhanced therapies (Jiang et al., 2017). For example, ternary Cu5FeS4 cubes with an average size of 5 nm and a strong NIR photoabsorption and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) ability, which enables them to be used as T1-weighted MRI contrast and photothermal nanoagents, have been developed by using the pyrolysis route (Wang et al., 2018). The Cu-Fe-S and Cu-Fe-Se nanostructures, with different compositions, such as Cu5FeS4 particles, Cu5FeS4 nanocrystals, Cu1.1Fe1.1S2 nanocrystals, and CuFeS2 nanocrystals, are one of the most interesting ternary systems (Pei et al., 2011; Gabka et al., 2016; Zhao et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2018). Among these Cu-Fe-S nanostructures, CuFeS2 nanocrystals are antiferromagnetic semiconductors, showing an excellent photoabsorption band ranging from the ultraviolet region to the NIR region. Currently, there are only a few available methods for preparing CuFeS2 nanocrystals. For example, one method involves the injection of sodium diethyldithiocarbamate to a mixture of CuCl2, FeCl3, and oleic acid in 1-dodecanethiol. The CuFeS2 nanocrystals obtained by using this method have an average size of ∼6 nm and an optical band gap of 1.2 eV, which is much higher than that (0.6–0.7 eV) of bulk CuFeS2 (Wang et al., 2010; Kumar et al., 2013). However, these synthesis methods require a complex operation and usually lead to water solubility problems, which limits their bio-applications. It has been revealed that nanoassemblies, similar to self-assembled WO3–x hierarchical nanostructures (Li et al., 2014) and CuS superstructures (Tian et al., 2011b) could serve as excellent laser-cavity mirrors which could make near-infrared light reflect multiple times on the surface of nanoassemblies, and thus can be used to promote the photothermal conversion efficiency. Therefore, it is vital to develop a simple method for synthesizing CuFeS2 nanocrystals with strong NIR photoabsorption, a high photothermal conversion efficiency, and hydrophilicity.

The aim of this study was to synthesize CuFeS2 nanoassemblies to be used as efficient photothermal nanoagents for photothermal therapy of cancer cells both in vitro and in vivo. The CuFeS2 nanoassemblies are prepared by using the liquid-solid-solution method, in which the metal ions of Cu2+ and Fe3+ react with the S precursor in the mixed solution containing deionized water, ethanol, oleic acid, sodium oleate, and poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) at 180°C for 48 h. The obtained CuFeS2 nanoassemblies are composed of ultrasmall CuFeS2 nanoparticles, and they exhibit a strong and broad NIR photoabsorption. Under laser irradiation at 808 nm, the aqueous solution containing the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies can rapidly convert laser energy into heat, achieving a high photothermal conversion efficiency of 46.8%. Importantly, after incubation with CuFeS2 nanoassemblies, cancer cells show high activity without laser irradiation, indicating that the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies are highly biocompatible. Moreover, when the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies are injected into tumors, the tumors show high contrast in thermal images and can be thermally ablated using laser irradiation at 808 nm. Therefore, the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies can be utilized as novel and efficient photothermal nanoagents for tumor therapy.

Materials and Methods

Synthesis of CuFeS2 Nanoassemblies

CuCl2⋅2H2O, FeCl3⋅6H2O, 1-dodecanethiol, oleic acid, sodium oleate, poly(N-vinyl-2-pyrrolidone) (PVP, K30), and anhydro ethanol were purchased from Sigma and were used without further purification. The CuFeS2 nanoassemblies were prepared by using the liquid-solid-solution method. In a typical synthesis route, CuCl2⋅2H2O (0.5 mmol) and FeCl3⋅6H2O (0.5 mmol) were introduced to a mixed solution containing deionized water (5 mL), ethanol (10 mL), oleic acid (10 mL), sodium oleate (5 mmol), and PVP (0.5 mg), and the mixture was stirred for 30 min at room temperature (∼23°C). Then, 10 mmol of 1-dodecanethiol was introduced into the above solution, which was stirred again for 60 min. The solution was sealed and treated in an autoclave at 180°C for 48 h. Then, the black precipitates were washed three times with a solution of ethanol/water (8/2 vol.). One part of the black precipitates was dispersed into the deionized water while another part was vacuum dried at 60°C.

Characterization of the CuFeS2 Nanoassemblies

The morphology of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies was studied by using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, JEOL2100F). The composites and phase of the CuFeS2 powder were measured by using x-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS, EscaLab) and an x-ray diffractometer (XRD, Bruker D4). The photoabsorption of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies in deionized water was tested by using a spectrophotometer (Shimadzu, UV-1900). The photothermal performance was investigated using a laser at 808 nm to illuminate the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies in deionized water, and their temperature change was recorded using a thermal imaging camera (FLIR A300).

Cytotoxicity Test

Cytotoxicity testing of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies was carried out by using the methyl thiazolyl tetrazolium (MTT) assay. In a typical procedure, K7M2 cells were seeded into 96-well culture plates at a density of 1 × 104/well under standard conditions for 12 h. Then, the medium was replaced with a new medium that contained CuFeS2 nanoassemblies at the final concentrations of 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 ppm, followed by incubation for 24 h. Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS, and fresh medium containing MTT (5 mg mL–1) was introduced to each well. After incubation for 2 h, the old medium was discarded, followed by the addition of 100 μL of dimethyl sulfoxide solution, and the absorption intensity at 570 nm was measured.

Photothermal Cell Therapy

To measure the efficiency of photothermal therapy in vitro, K7M2 cells were cultured into 96-well plates (1 × 104 cells/well) under standard conditions. After 12 h, the cell medium was replaced with fresh medium containing the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies at the final concentrations of 0, 10, 20, and 40 ppm. A total 1 h later, the K7M2 cells were exposed to laser illumination at 808 nm (1.0 W cm–2, 5 min). Subsequently, the cells were washed with PBS for the MTT test. In the meantime, after photothermal therapy, cells in the parallel group were stained with Calcein AM and Propidium iodide (PI) using the Calcein AM/PI assay for 1 h and imaged by using a microscope (Leica).

Photothermal Therapy of Solid Tumors

Mice bearing K7M2 tumors with a surface diameter of ∼0.5 cm were divided into two groups (n = 3/group) and they were anesthetized with pentobarbital (50 mg kg–1) before laser irradiation. The mice in the first group (PBS + Laser) were intratumorally injected with a PBS solution (50 μL) and irradiated at 808 nm with a laser (1.0 W cm–2, 5 min). The mice in the second group (CuFeS2 + Laser) were intratumorally injected with CuFeS2 nanoassemblies in PBS solution (50 μL, 40 ppm) and then irradiated at 808 nm with a laser (1.0 W cm–2 for 5 min). During the irradiation, the thermal image of the mouse body was monitored, and the surface temperature of the tumor was recorded.

Histological Examination

After photothermal therapy for 1 day, mice in all groups were sacrificed to harvest the tumors and main organs which were subsequently fixed in paraffin and then cryosectioned. The tissue slices were subsequently stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E), and examined using a digital microscope (Zeiss AxioCam MRc5).

Biocompatibility in vivo

The biodistribution of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies was evaluated using healthy mice intravenously injected with 12 mg⋅kg–1 of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies. Major organs, such as kidney, liver, spleen, heart, and lungs were achieved at different time points (i.e., 1, 7, 14, 20 days) after administration. Copper content in these organs were determined by ICP-AES analysis. Meanwhile, blood samples were collected at different time points (i.e., 0, 1, 7, 14, 20 days) after the intravenous injection of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies (12 mg⋅kg–1) or PBS solution.

Results and Discussion

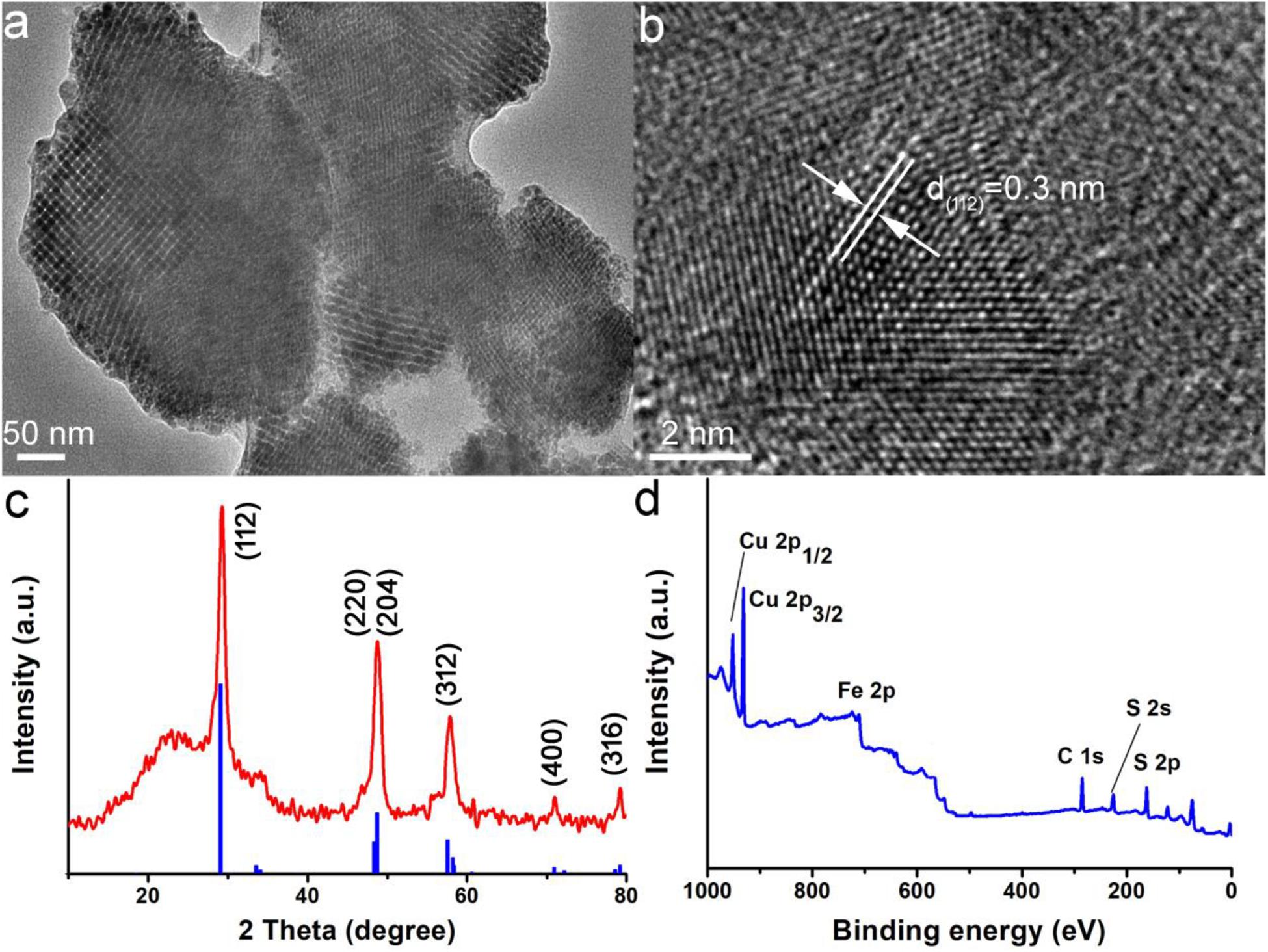

The CuFeS2 nanoassemblies were prepared by using the liquid-solid-solution method, in which the metal ions of Cu2+ and Fe3+ reacted with the S precursor in a mixed solution containing deionized water, ethanol, oleic acid, sodium oleate, and PVP at 180°C for 48 h. After the end of the reaction, black precipitates were obtained, and their morphology and size were first characterized by using TEM. The TEM image in Figure 1a reveals that the black precipitates are composed of nanoparticles with a size of 200–500 nm and do not have a clear morphology. The size of as-prepared products in water measured by dynamic light scattering (DLS) were around 400 nm (Supplementary Figure S1A), indicating that those products were mostly individually dispersed. Moreover, the size of the products in PBS determined by DLS showed very little change over time (Supplementary Figure S1B), also indicating a good dispersion. It should be noted that the term nanoassemblies is used to describe the sample as it is composed of a number of ultrasmall particles, which have an average size of ∼5 nm. The high resolution TEM image in Figure 1b exhibits a clear lattice with an interplane spacing of ∼0.3 nm, which corresponds to the (112) plane of the tetragonal CuFeS2 (JCPDS card no. 81–1959), indicating that the ultrasmall particles are CuFeS2. Furthermore, the phase of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies was also studied by using the XRD pattern (Figure 1c); there were three prominent diffraction peaks at 27.9°, 46.4°, and 55.0° which can be well indexed to (112), (220), and (312) of the tetragonal CuFeS2 (JCPDS no. 81–1959), respectively. Therefore, the above TEM and XRD analyses, demonstrate the successful synthesis of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies.

Figure 1. Characterization of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies using transmission electron microscopy (TEM) (a) TEM image, (b) High resolution (HR)-TEM image, (c) X-ray diffraction (XRD) pattern, and (d) X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) survey spectrum of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies.

Subsequently, the elements of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies were investigated using XPS. The XPS survey spectrum (Figure 1d) confirmed the obvious signals of Cu 2p, Fe 2p, and S 2p, which suggested that the nanoassemblies are made of Cu/Fe/S elements. In addition, the average Cu:Fe:S composition of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies was determined to be 1.00:0.97:2.12, which is quite close to the ideal ratio of 1:1:2. From the Cu 2p core-level spectrum (Supplementary Figure S2A), we could observe Cu1+ 2p3/2 at 932.6 eV and Cu1+ 2p2/2 at 952.5 eV while there was no trace of a satellite peak for Cu2+ 2p3/2 at around 942 eV, verifying that the Cu element in the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies is Cu1+. For the Fe2p core-level spectrum (Supplementary Figure S2B), Fe 2p3/2 and 2p1/2 are, respectively, centered at 710.6 eV and 723.6 eV which are in good agreement with Fe3+, indicating that the Fe element in the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies is at the state of + 3. Thus, XPS analysis confirmed the presence of Cu1+ and Fe3+ in the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies.

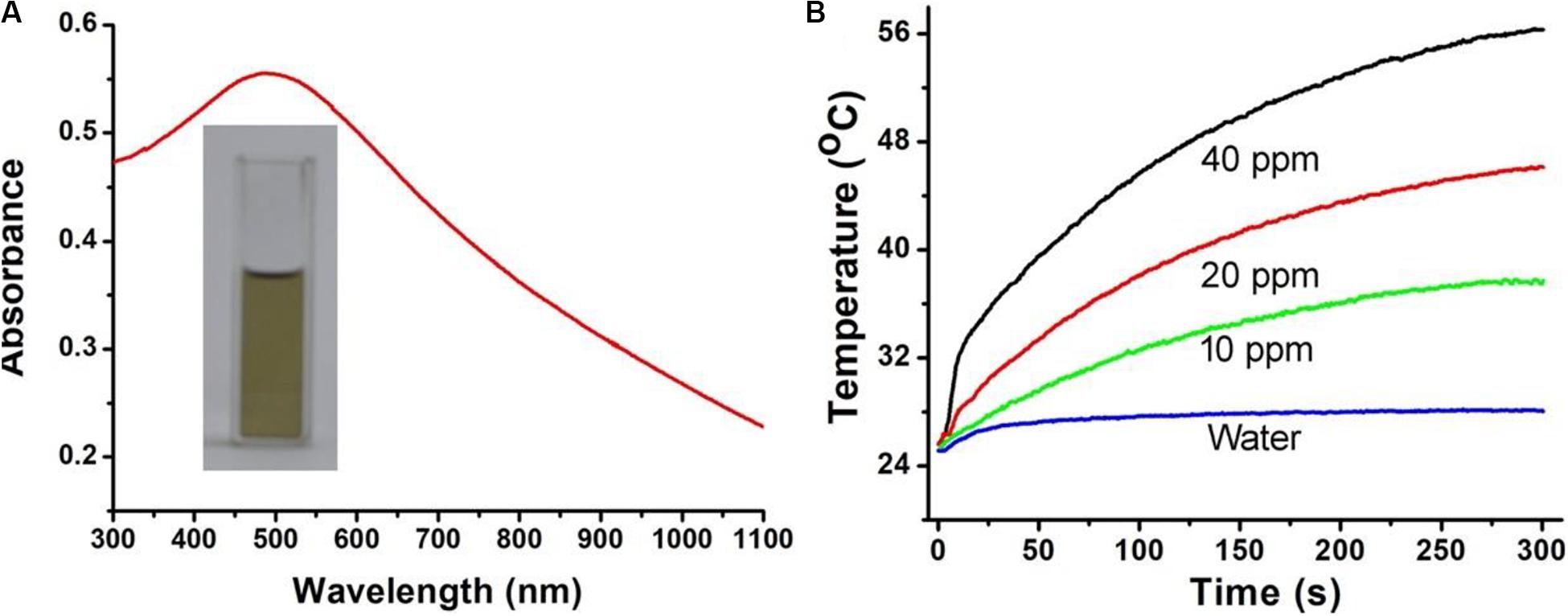

It has been reported that CuFeS2 nanomaterials are capable of NIR absorbance. To study the photoabsorption performance, CuFeS2 nanoassemblies were dispersed into deionized water and tested by using a UV-vis-NIR spectrophotometer. The solution of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies is dark yellow, and it shows a strong and broad absorbance ranging from 300 to 1100 nm with the peak centered at 500 nm (Figure 2A). Subsequently, we investigated the NIR-laser-induced photothermal effect by using an 808 nm laser to illuminate the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies in deionized water. Under the illumination of the laser at 1.0 cm–2, the temperature of deionized water goes up by less than 1.8°C after irradiation for 5 min, indicating no obvious photothermal effect for deionized water (Figure 2B). With the addition of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies, the temperature goes up quickly and the temperature elevation is determined to be 10.8, 20.4, or 29.7°C for the concentrations of 10, 20, or 40 ppm, respectively, indicating a rapid laser response and a high photothermal conversion. The above results confirm the strong and concentration-related performance of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies when illuminated by a NIR laser at 808 nm.

Figure 2. (A) A representative photograph and photoabsorption spectrum of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies dispersed in water. (B) Temperature elevation curves of the solution containing CuFeS2 nanoassemblies at a concentration of 0–40 ppm.

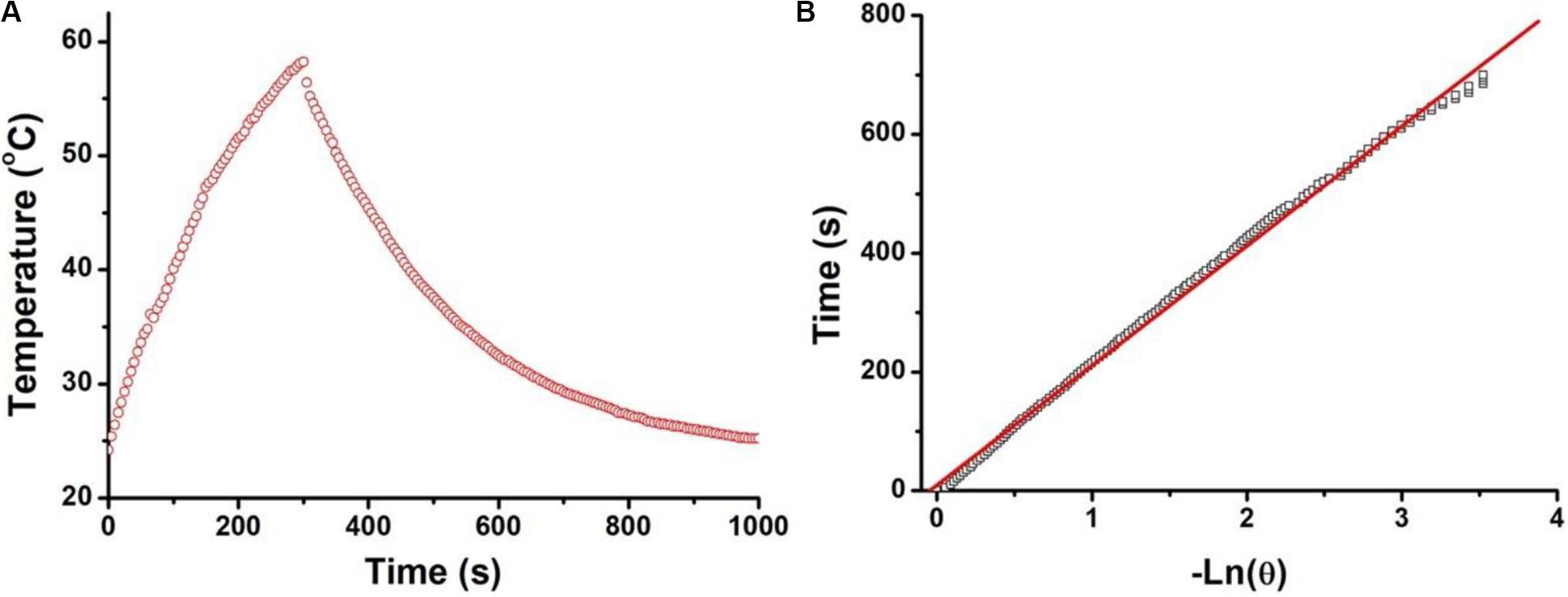

In order to calculate the photothermal conversion efficiency (η) of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies, we dispersed them into deionized water, which was then exposed to 808 nm NIR laser (1.0 cm–2, 5 min) irradiation. The temperature curve during the laser’s on and off periods was recorded, as demonstrated in Figure 3A. The temperature quickly increased once the nanoassemblies were exposed to 808 nm irradiation and then it decreased when the laser was turned off. Figure 3B shows the system time constant τs which was obtained from the cooling period when the laser was switched off, and was determined to be 168.4 s. The photothermal conversion efficiency was calculated by using the following equations:

Figure 3. (A) Temperature curve of a solution containing the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies during the periods the 808 nm laser was switched on and off. (B) The system time constant τs by linear fitting time data with ln(θ).

where I and A808 stand for the NIR laser power and the absorbance of dispersion at 808 nm, respectively. The value of hA can be calculated from the equation used to calculate the system time constant τs with the help of the mass (mD, 0.2 g) and the heat capacity (CD, 4.2 J g–1) of deionized water. ΔTmax,dis and ΔTmax,H2O are the temperature changes of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies and of deionized water, respectively. The photothermal conversion efficiency of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies was calculated to be 46.8%. Therefore, the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies have a high photothermal conversion efficiency, indicating a great potential to be utilized as an efficient photothermal nanoagent for treating cancer cells.

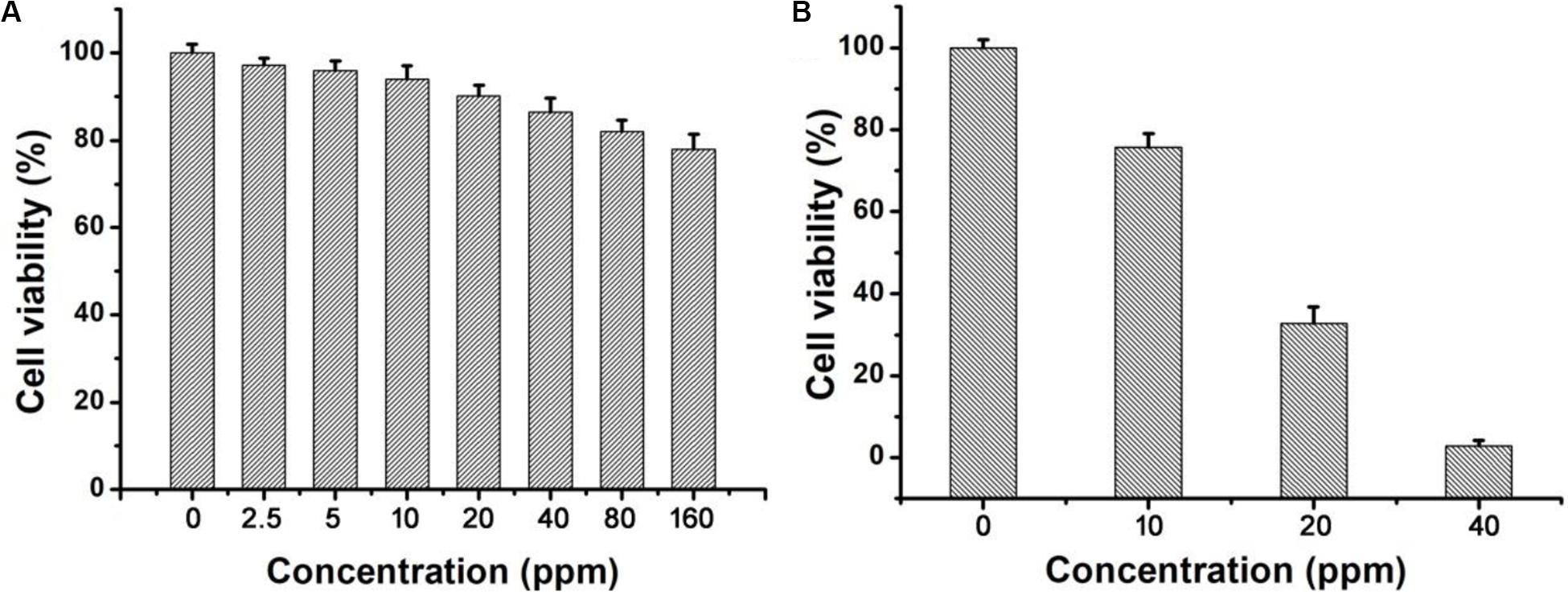

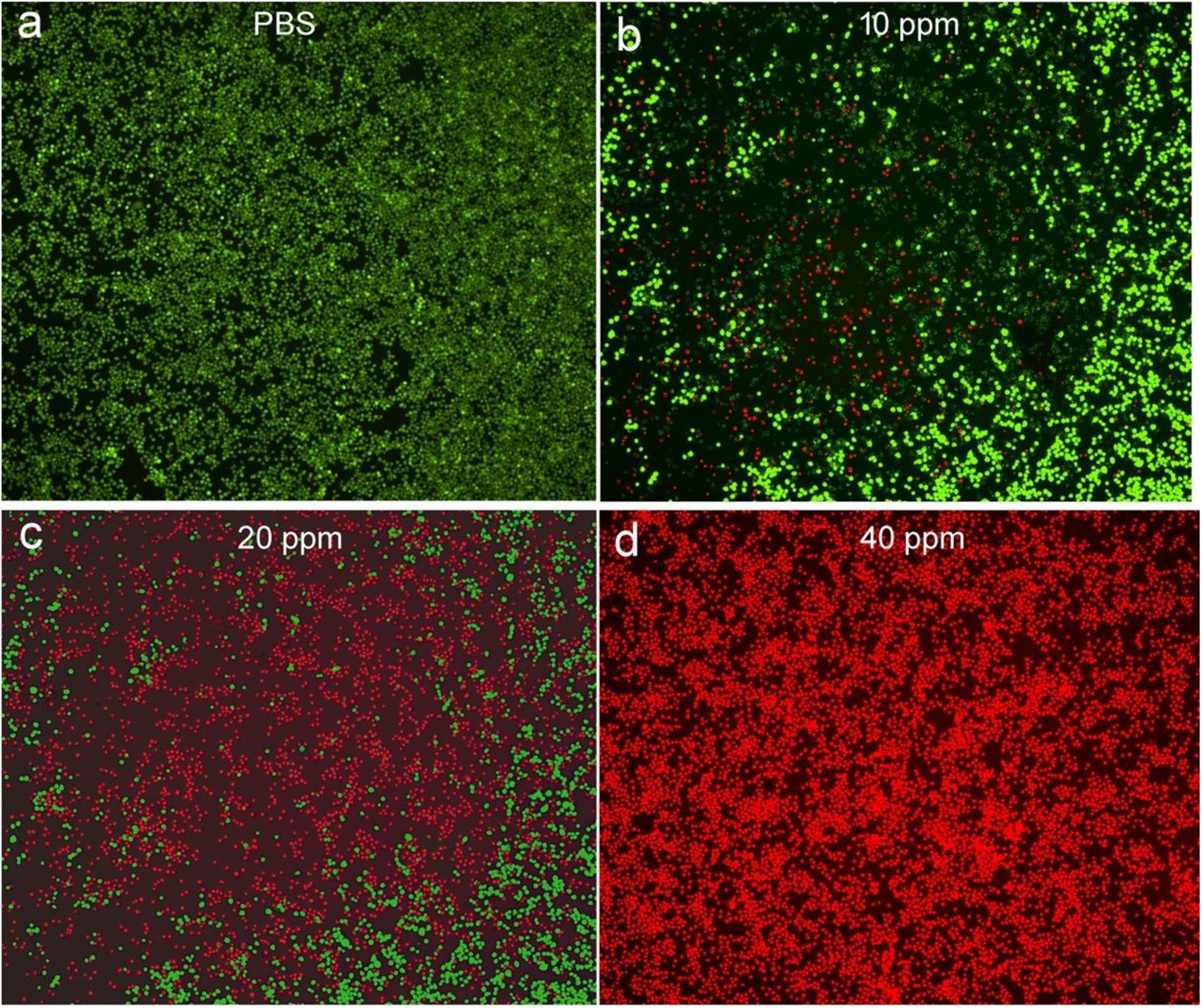

Next, we investigated the effects of these CuFeS2 nanoassemblies on the viability of K7M2 cells in vitro through the MTT method. After incubation with the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies at the concentrations of 0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 ppm for 24 h (Figure 4A), K7M2 cells retained high viability. Their viability at 160 ppm was determined to be as high as >85%, indicating the low cytotoxicity of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies. Moreover, we have investigated the photothermal therapeutic ability of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies by incubating them with cells and then irradiating them with a laser at 808 nm (1.0 cm–2, 5 min). Compared to the cells that were not incubated with CuFeS2 nanoassemblies, the viability of the cells treated with CuFeS2 nanoassemblies decreased as the concentration of the added CuFeS2 nanoassemblies increased. The average viability of the K7M2 cells was 78, 36.5, and 8.6% at the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies concentrations of 10, 20, and 40 ppm (Figure 4B), respectively. In the meantime, the treated cells were treated with a Calcine AM/PI assay to clarify the therapeutic photothermal effects of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies. Laser-irradiated cells treated with PBS showed green fluorescence (Figure 5a), which indicated that the laser had no effect on the activity of these cells. In contrast, laser-irradiated cells incubated with the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies simultaneously showed green and red fluorescence at the concentration of 10 ppm, whereas only red fluorescence appeared at the concentration of 40 ppm, indicating all cells were killed (Figures 5b–d). Thus, we can confirm that, when exposed to the 808 nm NIR laser, the high photothermal effect of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies has a high therapeutic efficiency in K7M2 cells.

Figure 4. (A) The relative viability of K7M2 cells after incubation with the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies at a series of concentrations (0, 2.5, 5, 10, 20, 40, 80, and 160 ppm). (B) The relative viability of K7M2 cells after incubation with the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies (0, 10, 20, and 40 ppm) followed by laser irradiation at 808 nm.

Figure 5. Fluorescence images of Calcein AM/Propidium iodine-stained K7M2 cells after incubation with (a) PBS solution and (b–d) the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies at different concentrations (10, 20, and 40 ppm) followed by laser irradiation at 808 nm.

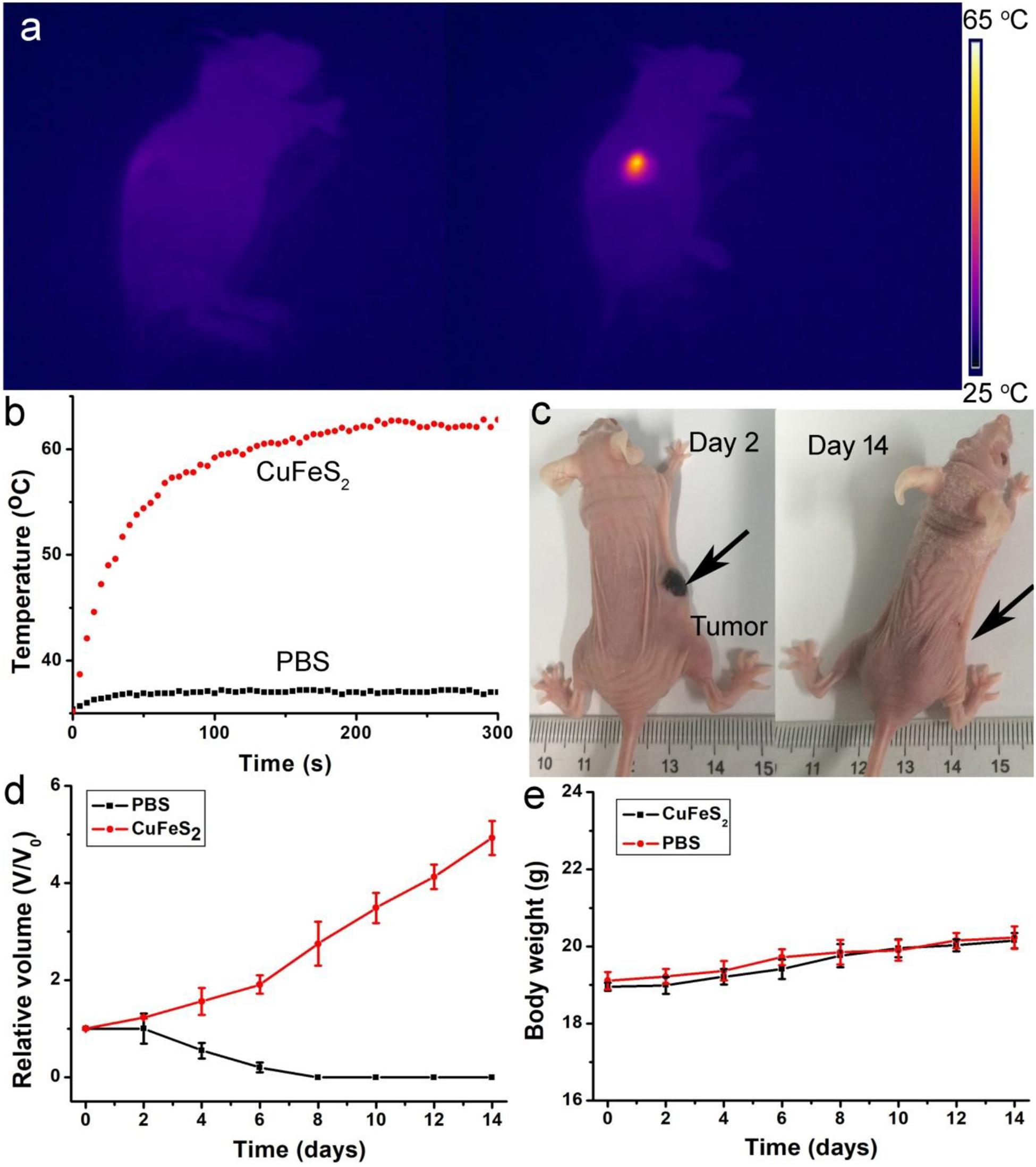

After establishing the high photothermal ablation efficiency in vitro, we further examined the photothermal therapy in vivo. Mice bearing K7M2 tumors with a surface diameter of ∼0.5 cm were divided into two groups: (1) PBS + Laser, (2) CuFeS2 + Laser. The center of the tumors of mice in group (1) was injected with PBS solution (50 μL), while the tumor center of mice in group (2) was injected with a CuFeS2 PBS solution (50 μL, 40 ppm). The tumors in groups (1) and (2) were then laser-illuminated at 808 nm with an output power intensity of 1.0 cm–2 for 5 min, and the thermal image of the mouse body was captured. Figure 6a demonstrates the thermal image of mice in groups (1) and (2), demonstrating that the tumor treated with the CuFeS2 PBS solution showed a much brighter red fluorescence than that of the tumor treated with the PBS solution. The temperature profile of tumors in groups (1) and (2) is shown in Figure 6b. The tumor treated with the CuFeS2 PBS solution showed a high max temperature of 63°C whereas the PBS-treated tumor exhibited a max temperature of 38°C. The high temperature in the tumor area is attributed to the high photothermal conversion efficiency of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies, which can result in a high therapeutic effect. After the photothermal therapy, a scar could be found at the site of the CuFeS2-treated tumor at day 2, while the original tumor and scar disappeared at day 14 (Figure 6c). Additionally, the tumors of mice in group (2) were disappeared and there was no reoccurrence observed (Figure 6d), while the tumors gradually increased in group (1). What’s more, there was almost no difference in body weight among the two groups of mice (Figure 6e), indicating the low toxicity of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies at the given conditions.

Figure 6. (a) Thermal image of a mouse body showing the tumor area injected with PBS (left) and CuFeS2 nanoassemblies (right) and exposed to 808 nm NIR laser irradiation. (b) Typical temperature elevation curves of the treated tumors. (c) Photographs of mice after photothermal therapy. (d) Growth curves of tumors over time in the two groups after the treatments. (e) Body weight curves over time in the two groups after the treatments.

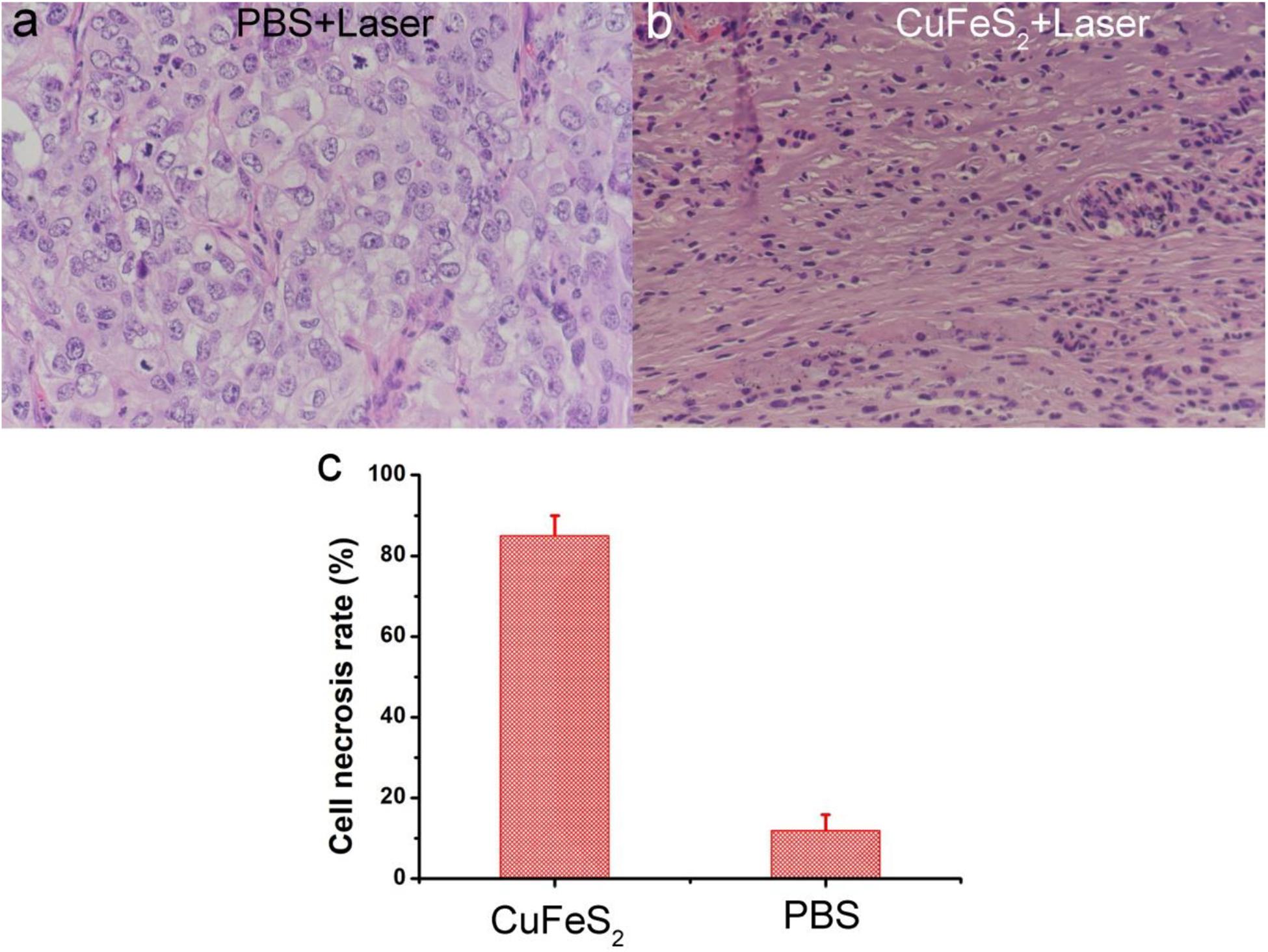

After photothermal therapy, the mice in the two groups were sacrificed, and tumors were extracted and sectioned for H&E staining. The typical images of H&E-stained tumor slices are shown in Figures 7a,b. The cells of the tumor which were injected with PBS and irradiated have a normal morphology, indicating the laser had no effect on tumor cells at the given intensity. On the contrary, the cells of the tumor which were injected with the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies and irradiated by 808 nm lasers had condensed nuclei. In addition, the loss of normal cell morphology can be observed. Furthermore, the average cell necrosis rate was 88.4% in tumors treated with CuFeS2 and laser irradiation which was significantly higher than that (11.8%) of tumors treated with PBS and laser irradiation (Figure 7c). Therefore, the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies developed in this study have been demonstrated to have excellent photothermal performance in vivo, and can, thus, be employed as an efficient nanomaterials for photothermal therapy of solid tumors.

Figure 7. Photographs of hematoxylin and eosin (H&E)-stained tumor slices (a) Tumor treated with PBS and laser irradiation and (b) Tumor treated with CuFeS2 nanoassemblies and laser irradiation. (c) The cell necrosis rate of the treated tumors.

The ideal photothermal agents should have excellent biocompatibility for biological applications. The biodistribution of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies was evaluated using healthy mice intravenously injected with 12 mg⋅kg–1 of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies. Major organs, such as the kidney, liver, spleen, heart, and lungs were achieved at different time points (i.e., 1, 7, 14, 20 days) after administration. Copper content in these organs were determined by ICP-AES analysis. It showed (Supplementary Figure S3) that the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies mainly accumulated in the liver and spleen after the intravenous administration. The content in these two organs gradually decreased over time, indicating that CuFeS2 nanoassemblies were mainly degraded through these two organs. The cytotoxicity of CuFeS2 nanoassemblies on major organs was evaluated via H&E analysis. A total 20 days of the intravenous injection of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies (12 mg⋅kg–1) or PBS solution, major organs were collected for H&E analysis. The shape and size of the organs in the two groups almost showed no change (Supplementary Figure S4). Meanwhile, blood samples were collected at the different time points (i.e., 0, 1, 7, 14, 20 days) after the intravenous injection of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies (12 mg⋅kg–1) or PBS solution. There was no obvious difference in the alanine aminotransferase (ALT, Supplementary Figure S5A) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST, Supplementary Figure S5B), which indicated that CuFeS2 nanoassemblies at the given dose showed almost no effect on the liver and kidney. Therefore, the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies showed excellent biocompatibility.

Conclusion

In summary, the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies we synthesized in this study are efficient photothermal nanoagents for photothermal therapy of cancer cells in vitro and in vivo. The CuFeS2 nanoassemblies are synthesized by using the liquid-solid-solution method, and are composed of ultrasmall CuFeS2 nanoparticles with an average size of 5 nm. Furthermore, the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies exhibit strong NIR photoabsorption and can rapidly convert laser energy into heat, achieving a high photothermal conversion efficiency of 46.8%. Following incubation with CuFeS2 nanoassemblies without laser irradiation, cancer cells retain high activity indicating the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies have high biocompatibility. However, under laser irradiation at 808 nm the cells can be thermally ablated due to the high photothermal effect of the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies. Furthermore, when the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies are injected into tumors, the tumors show a high contrast in thermal images when laser-irradiated, and the tumor cells are then thermally ablated. Therefore, the CuFeS2 nanoassemblies can be utilized as novel and efficient photothermal nanoagents for tumor therapy and inspire the development of other novel nanoagents using an assembly strategy.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material.

Ethics Statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by Shengli Oilfield Central Hospital.

Author Contributions

SH and GL designed the project. SH, ZYa, MH, ZYu, and XJ carried out the experiment. SH, MH, and GL performed the experimental data analysis. SH, GL, and XJ wrote the manuscript. All the authors contributed to the discussion of the results.

Funding

This study was supported by the Zhejiang Province Public Welfare Technology Application Research Project of China (No. LGF19G010005) and the Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China (No. LQ19E050011).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmats.2020.00289/full#supplementary-material

References

Dreaden, E. C., Mackey, M. A., Huang, X. H., Kang, B., and El-Sayed, M. A. (2011). Beating cancer in multiple ways using nanogold. Chem. Soc. Rev. 40, 3391–3404. doi: 10.1039/c0cs00180e

Gabka, G., Bujak, P., Zukrowski, J., Zabost, D., Kotwica, K., Malinowska, K., et al. (2016). Non-injection synthesis of monodisperse Cu-Fe-S nanocrystals and their size dependent properties. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 18, 15091–15101. doi: 10.1039/C6CP01887D

Ge, J. C., Jia, Q. Y., Liu, W. M., Guo, L., Liu, Q. Y., Lan, M. H., et al. (2015). Red-emissive carbon dots for fluorescent, photoacoustic, and thermal theranostics in living mice. Adv. Mater. 27, 4169–4177. doi: 10.1002/adma.201500323

Huang, X., Zhang, W., Guan, G., Song, G., Zou, R., and Hu, J. (2017). Design and functionalization of the nir-responsive photothermal semiconductor nanomaterials for cancer theranostics. Acc. Chem. Res. 50, 2529–2538. doi: 10.1021/acs.accounts.7b00294

Huang, X. Q., Tang, S. H., Mu, X. L., Dai, Y., Chen, G. X., Zhou, Z. Y., et al. (2011). Freestanding palladium nanosheets with plasmonic and catalytic properties. Nature Nanotechnol. 6, 28–32. doi: 10.1038/nnano.2010.235

Jiang, X., Zhang, S., Feng, R., Lei, C., Zeng, J., Mo, Z., et al. (2017). Ultra-small magnetic CuFeSe2 ternary nanocrystals for multimodal imaging guided photothermal therapy of cancer. Acs Nano 11, 5633–5645. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.7b01032

Kumar, P., Uma, S., and Nagarajan, R. (2013). Precursor driven one pot synthesis of wurtzite and chalcopyrite CuFeS2. Chem. Commun. 49, 7316–7318. doi: 10.1039/c3cc43456g

Li, B., Zhang, Y., Zou, R., Wang, Q., Zhang, B., An, L., et al. (2014). Self-assembled WO3-x hierarchical nanostructures for photothermal therapy with a 915 nm laser rather than the common 980 nm laser. Dalton Trans. 43, 6244–6250. doi: 10.1039/c3dt53396d

Li, Y. B., Lu, W., Huang, Q. A., Huang, M. A., Li, C., and Chen, W. (2010). Copper sulfide nanoparticles for photothermal ablation of tumor cells. Nanomedicine 5, 1161–1171. doi: 10.2217/nnm.10.85

Ling, C., Zhou, L. Q., and Jia, H. (2014). First-principles study of crystalline CoWO4 as oxygen evolution reaction catalyst. RSC Adv. 4, 24692–24697. doi: 10.1039/c4ra03893b

Liu, Y. L., Ai, K. L., Liu, J. H., Deng, M., He, Y. Y., and Lu, L. H. (2013). Dopamine-melanin colloidal nanospheres: An efficient near-infrared photothermal therapeutic agent for in vivo cancer therapy. Adv. Mater. 25, 1353–1359. doi: 10.1002/adma.201204683

Pei, L. Z., Wang, J. F., Tao, X. X., Wang, S. B., Dong, Y. P., Fan, C. G., et al. (2011). Synthesis of CuS and Cu1.1Fe1.1S2 crystals and their electrochemical properties. Mater. Charact. 62, 354–359. doi: 10.1016/j.matchar.2011.01.001

Robinson, J. T., Tabakman, S. M., Liang, Y. Y., Wang, H. L., Casalongue, H. S., Vinh, D., et al. (2011). Ultrasmall reduced graphene oxide with high near-infrared absorbance for photothermal therapy. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 133, 6825–6831. doi: 10.1021/ja2010175

Tian, Q. W., Jiang, F. R., Zou, R. J., Liu, Q., Chen, Z. G., Zhu, M. F., et al. (2011a). Hydrophilic Cu9S5 nanocrystals: A photothermal agent with a 25.7% heat conversion efficiency for photothermal ablation of cancer cells in vivo. ACS Nano 5, 9761–9771. doi: 10.1021/nn203293t

Tian, Q. W., Tang, M. H., Sun, Y. G., Zou, R. J., Chen, Z. G., Zhu, M. F., et al. (2011b). Hydrophilic flower-like CuS superstructures as an efficient 980 nm laser-driven photothermal agent for ablation of cancer cells. Adv. Mater. 23, 3542–3547. doi: 10.1002/adma.201101295

Vankayala, R., and Hwang, K. C. (2018). Near-Infrared-light-activatable nanomaterial-mediated phototheranostic nanomedicines: An emerging paradigm for cancer treatment. Adv. Mater. 30:e1706320. doi: 10.1002/adma.201706320

Wang, D., Zhang, Y. W., and Guo, Q. (2018). Sub-10 nm Cu5FeS4 cube for magnetic resonance imaging-guided photothermal therapy of cancer. Int. J. Nanomed. 13, 7987–7996. doi: 10.2147/IJN.S181056

Wang, Y.-H. A., Bao, N., and Gupta, A. (2010). Shape-controlled synthesis of semiconducting CuFeS2 nanocrystals. Solid State Sci. 12, 387–390. doi: 10.1016/j.solidstatesciences.2009.11.019

Yang, K., Zhang, S., Zhang, G. X., Sun, X. M., Lee, S. T., and Liu, Z. (2010). Graphene in mice: Ultrahigh in vivo tumor uptake and efficient photothermal therapy. Nano Lett. 10, 3318–3323. doi: 10.1021/nl100996u

Yu, N., Hu, Y., Wang, X., Liu, G., Wang, Z., Liu, Z., et al. (2017). Dynamically tuning near-infrared-induced photothermal performances of TiO2 nanocrystals by Nb doping for imaging-guided photothermal therapy of tumors. Nanoscale 9, 9148–9159. doi: 10.1039/C7NR02180A

Yu, N., Peng, C., Wang, Z., Liu, Z., Zhu, B., Yi, Z., et al. (2018a). Dopant-dependent crystallization and photothermal effect of Sb-doped SnO2 nanoparticles as stable theranostic nanoagents for tumor ablation. Nanoscale 10, 2542–2554. doi: 10.1039/C7NR08811F

Yu, N., Wang, Z., Zhang, J., Liu, Z., Zhu, B., Yu, J., et al. (2018b). Thiol-capped Bi nanoparticles as stable and all-in-one type theranostic nanoagents for tumor imaging and thermoradiotherapy. Biomaterials 161, 279–291. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.01.047

Zha, Z., Yue, X., Ren, Q., and Dai, Z. (2013). Uniform polypyrrole nanoparticles with high photothermal conversion efficiency for photothermal ablation of cancer cells. Adv. Mater. 25, 777–782. doi: 10.1002/adma.201202211

Zhao, Q., Yi, X., Li, M., Zhong, X., Shi, Q., and Yang, K. (2016). High near-infrared absorbing Cu5FeS4 nanoparticles for dual-modal imaging and photothermal therapy. Nanoscale 8, 13368–13376. doi: 10.1039/C6NR04444A

Keywords: near infrared light, bioimaging, photothermal conversion, CuFeS2 nanoassemblies, cancer therapy

Citation: Huang S, Li G, Yang Z, Hua M, Yuan Z and Jin X (2020) CuFeS2 Nanoassemblies With Intense Near-Infrared Absorbance for Photothermal Therapy of Tumors. Front. Mater. 7:289. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2020.00289

Received: 11 June 2020; Accepted: 30 July 2020;

Published: 25 September 2020.

Edited by:

Ming Ma, Shanghai Institute of Ceramics (CAS), ChinaReviewed by:

Wenlong Zhang, Xinxiang Medical University, ChinaGuoying Deng, Shanghai General Hospital, China

Copyright © 2020 Huang, Li, Yang, Hua, Yuan and Jin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gang Li, bGlnYW5nQHpqbnUuY24=; Xin Jin, c2x5dGp4QDE2My5jb20=

Shan Huang1

Shan Huang1 Gang Li

Gang Li