94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mater. , 19 June 2020

Sec. Structural Materials

Volume 7 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmats.2020.00165

This article is part of the Research Topic Enhancement of Ductility of FRP-Concrete Structures View all 8 articles

The behavior of the bond between Engineering Cementitious Composites (ECC) and Glass Fiber Reinforced Polymer (GFRP) bar has a strong effect on the behavior of this composite structure. However, it is difficult to detect the failure mode and damage status of the interface using traditional testing methods. This is due to the strain-hardening mechanical behavior of ECC. An effective monitoring method using patch lead zirconate titanate (PZT) transducers and active sensing technology was used to detect the internal damage. In this active sensing technology, a PZT smart aggregate was bonded onto the middle surface of ECC, acting as a sensor. This study conducted a series of experimental studies on the bond behavior of GFRP-reinforced ECC based on pull-out tests. The test results are presented and discussed to investigate the bond-slip relationship and failure mechanism between FRP reinforcing bars and the ECC matrix. The status of interfacial damage between ECC and GFRP can be represented by the attenuation change of the stress wave. Finally, a damage index (DI) obtained using wavelet packet analysis is proposed to evaluate and quantify the level of FRP–ECC interaction damage. The analytical results reveal that the debonding and failure mechanism can be detected by using this DI index value, and the influence of the diameter of reinforcing bars should be considered, as should the Poisson's effect.

Engineering cementitious composites (ECC) are strain-hardening materials (Li et al., 2001; Lepech and Li, 2010; Chai et al., 2018). The mechanical properties of ECC include high strain-hardening, high shear resistance, and low density (Li et al., 1997; Li, 1998; Caner et al., 2002; Sui et al., 2018; Zheng et al., 2018a). ECC, as a fiber-reinforced cement composite material, has a tensile strain of more than 3% (Li, 1998). The average crack width of ECC has been found to be below 0.1 mm (Özbay et al., 2013; Sherir et al., 2015). The ECC material can be utilized as a good choice for solving durability problems of structures caused by the brittleness of concrete. The corrosion of steel rebar in reinforced concrete structures leads to serious structural safety problems. Fiber-reinforced polymer (FRP) reinforcement has been considered a promising way of overcoming this issue (Nayal and Rasheed, 2006; Martinelli and Caggiano, 2014). FRP reinforcement has advantages such as high strength, low weight and elastic modulus, low cost, and excellent corrosion resistance (Yuan et al., 2013; Ge et al., 2019). The replacement of steel bar by FRP bar has become an accepted practice for enhancing the durability of structures (Martinelli and Caggiano, 2014).

Combining with ECC and FRP reinforcement is an effective method of improving the ductility and durability of this component (Zheng et al., 2018a). Previous studies demonstrate that the combination of ECC and GFRP can effectively improve the workability and energy dissipation capacity of these components (Yuan et al., 2013; Zhou et al., 2017; Ge et al., 2019). A study by Firas et al. indicated that the use of ECC has a positive effect on the behavior of the bond due to the inter-laminar rupture mechanism (Firas et al., 2011). Zheng et al. found that the bond behavior of ECC and FRP provides an improvement in the deformation capacity of these components (Zheng et al., 2018a). The behavior of the bond has a significant effect on the performance of FRP-reinforced components (Hossain, 2018; Zhou L. Z. et al., 2020). It was reported in a study by Kim et al. that the fibers in concrete changed the bond behavior and resulted in significant improvement in bond strength (Kim et al., 2013), which agreed with the results reported by Won et al. (2008) and Mazaheripour et al. (2013). Zhou et al. showed that the lower elastic modulus of FRP bar leads to a different failure mode than in steel-reinforced components (Zhou L. Z. et al., 2020). The damage mechanism and failure mode have a significant effect on the performance of FRP-reinforced components (Zhou L. Z. et al., 2020). It was reported that the existing experimental results for the bond behavior of FRP-reinforced concrete were not suitable for ECC-reinforced FRP (Bai et al., 2019; Gao et al., 2019). However, few related studies have been reported that investigated the damage mechanism and failure mode of FRP in ECC. Previous studies indicated that the bond behavior of FRP and ECC was a key factor affecting the workability and failure mechanism of this kind of reinforced components (Firas et al., 2011; Wang et al., 2015; Hossain, 2018; Zhou et al., 2018; Zhou L. Z. et al., 2020). To investigate the damage mechanism and failure mode of FRP bar in ECC, more studies need to be undertaken to look at premature and failure debonding of the interface between ECC and FRP bars.

Piezoceramic materials have been adopted as sensors in structural health monitoring in recent years (Song et al., 2007a; Zheng et al., 2018b; Han et al., 2019) due to the strong piezoelectric effect, high sensitivity, wide frequency range, energy harvesting, and low cost (Wang et al., 2018; Xu et al., 2018a). Test results have indicated that the debonding of a chemical connection can be detected by using the piezoelectric method (Song et al., 2007a,b; Xu et al., 2013, 2018b; Wang et al., 2017; Zheng et al., 2018b; Zhou Y. et al., 2020). A piezoceramic-based smart aggregate (SA) sensor was proposed by Song et al. and has been utilized to detect structural interface damage (Song et al., 2007a). It was reported by Qin et al. that this active sensing method can be used to detect the damage process of bond-slip between steel plate and concrete. It was reported that the proposed damage index based on SA can detect the debonding condition of FRP-reinforced concrete (Jiang et al., 2017). Though some researchers have successfully detected mechanical debonding damage between steel and concrete using SA sensors, the detection of both premature and failure debonding has not been reported for FRP-reinforced ECC. The bond behavior of these structures has been found to be different from that of FRP-reinforced concrete due to strain hardening of the ECC material (Xu et al., 2012; Zhang and Li, 2014). The failure process of ECC material at the interface is different from that of concrete, which is mainly determined by the fiber bridge stress. It is significant to study the bond-slip behavior of ECC and GFRP bars based on a piezoceramic transducer.

To study the bond-slip behavior and failure modes of ECC reinforced with FRP bar, a wavelet energy ratio index method was used to detect the damage status and failure modes of ECC and GFPR bars. In this paper, pull-out tests were conducted, and the active piezoceramic transducer method was implemented. A piezoceramic-based patch was bonded to the surface of FRP bar as the actuator, and a smart aggregate (SA) was bonded onto the ECC as the sensor. The test variable is the diameter of the GFPR bar. The damage status and failure modes of bond-slip behavior were detected effectively. The premature and failure debonding of the interface between ECC and GFRP bars were captured successfully based on the wavelet packet method. It can be summarized that the bond-slip behavior of ECC and GFRP bars could feasibly be detected based on the piezoceramic transducers and the wavelet packet method.

To investigate the bond-slip behavior of ECC and GFRP bars based on the active sensing method, the effect of the FRP bar diameter will be investigated in this study. A suitable mix proportion for the ECC was selected by using different binding materials (Zheng et al., 2018a). Type I Portland cement, type F fly ash, and fine silica sand (109–212 μm) were utilized as the matrix of the ECC. The sand-binder ratio is ~0.35. To improve the fluidity of the mixture, a superplasticizer and the thickener were used. PE fiber (2.0%) was used as the reinforcement in the mix. The work performance and flow property of the ECC mixture satisfied the requirements of standard (ACI 440.3R-04, 2004). The diameters of the GFRP bar used in this study were 13, 16, and 19 mm. In this paper, GFRP bar with a sand-coated surface was used. The corresponding ultimate strengths of the GFRP bars (13, 16, and 19 mm) are 1,003, 920, and 882 MPa, respectively. The elastic moduli of the adopted GFRP bars are 52, 48, and 48 GPa (13, 16, and 19 mm), respectively.

Nine specimens were divided into three series with different diameters. The dimension of ECC in the specimen was Φ160 mm × 200 mm. The embedded length of the GFRP bar was 5 d (five times the diameter of the GFRP bar) (Zhou L. Z. et al., 2020; see Figure 1). The non-bonded length was protected by PVC tubes to avoid the adhesion of ECC. The specimens were poured in one step and demolded after 24 h. The specimens were cured under the environment of a temperature of 20 ± 2°C and a humidity of 95% for 28 days (Zheng et al., 2018a).

To detect the interfacial damage status and the failure modes of ECC and FRP, the PZT and SA were bonded to the surface of FRP bar and ECC, respectively (see Figure 1). The PZT patch transducer was used as an actuator, and the SA was used to sense the signal. The SA was bonded to the middle surface of the ECC correctly.

The experimental setup in this study is shown in Figure 2. A universal material testing machine was used to control the applied load. The force datum and the corresponding displacement datum were collected by a TDS-540 device. A NI USB 6363 single drive device was utilized to generate the initial signal and send it to the power amplifier and the laptop computer. The received signal was detected by the NI USB 6363 through the SA. The initial transmitted signal has a frequency range from 100 Hz to 100 kHz (Xu et al., 2018c). The voltage amplitude is 5 V, and the sweep period set was 1 s (Zheng et al., 2018b). The sampling rate of the signal response is 2 MHz. The constant displacement rate of the experiment is 0.5 mm/min. The loading scheme was composed of about 28 operating conditions (OC). At the beginning of the test, the interval of an OC is small to detect premature debonding information. Subsequently, the step was set every 1 mm. The load was put on hold between each step for the data acquisition (Jiang et al., 2017). During the loading test, the SA signal received was recorded in each operating condition.

Piezoceramic-based material has been utilized as sensors due to the piezoceramic effect (see Figure 1) (Dumoulin et al., 2014; Huo et al., 2017). Lead zirconate titanate is a widely used piezoelectric material (Zou et al., 2015). The surfaces of the PZT (lead zirconate titanate) patch are covered with copper sheets. A piezoceramic-based smart aggregate (SA) sensor, which was proposed by Song et al. (2007a), has been used as an effective method for detecting the damage of reinforced components successfully. The SA has a sandwich structure, including a PZT patch and two marble blocks (Zhang et al., 2018). Due to the protection of the marble shell, the SA can be used to detect damage (Feng et al., 2016). An active sensing approach based on SA has previously been utilized as the sensor method to detect the bond-slip mechanical behavior between steel plate and concrete (Qin et al., 2015). Obviously, the SA detection method has great potential for the detection of the debonding of ECC and FRP. To generate an equal amplitude stress wave, a PZT patch was bonded as shown in Figure 1. The stress wave with the interface damage information was transmitted to the SA on the surface of the ECC. Before the loading process of the test, the received signal reflects the health status of the specimen, and this signal was also used as the baseline signal for analysis. The amplitude of the stress wave is changed after the original stress wave passes through the damage interface between ECC and FRP (Jiang et al., 2017). The debonding deterioration of the interface affects the energy dissipation of the stress wave during the pull-out tests. The debonding damage of premature debonding and failure debonding of ECC and FRP can be quantified based on this method.

To analyze the information on damage in the received signal, the wavelet packet method was utilized due to the frequency coverage of both high- and low-frequency bands (Song et al., 2007b; Xu et al., 2012; Han et al., 2019). The interfacial degradation was quantified through comparative analysis of the received signal (Qin et al., 2015). In this paper, different loading conditions of premature debonding and failure debonding were imposed to study the bond-slip process. Based on n-level wavelet packet decomposition, the received signal S can be decomposed into 2n signal sets {S1,S2,…,Sn2}. The decomposed signal Sj is shown as,

where n is the sequence number of the decomposed signal. j (j= 1 …2n) is the frequency band. The energy of the decomposed signal can be expressed as

where I is the operating condition of the experiment. The signal energy vector can be expressed as

DI can be defined as

where E1.j means the energy vector of the baseline signal before the pull-out test and Ei.j means the energy vector of that specific operating condition. DI represents the interfacial damage state. In the healthy state of the specimen, the DI value is zero. During the pull-out test, the value of DI increases with the interfacial damage state. The value of DI is 1 when the interface between ECC and FRP has experienced total debonding.

The specimens were designated according to bar diameter (13, 16, and 19 mm). The embedded length is 5 times the diameter. The average bond stress was defined as:

where P is the load (kN), d is the diameter of GFRP bars (mm), and l is the embedded length (mm). The test results of specimens are summarized in Table 1. In this table, τche and τmax are the premature debonding and the maximum bond strength. tpre and tfai are the corresponding slip value of the free end. τre is the residual bond stress.

The bond stress-slip curves are plotted in Figure 3. The bond-slip curves can be divided into three phases: (1) the elastic phase, (2) the nonlinear phase, and (3) the failure phase. An increase in diameter from 13 to 19 mm resulted in a decrease in bond strength by about 80% due to the Poisson's effect of GFRP bars (Di et al., 2018). The average corresponding slip value of bond strength was increased by 257%. This phenomenon can also be found in the literature (Baena et al., 2009; Li et al., 2017; Di et al., 2018; Naik et al., 2019). Interestingly, the G16 specimens have different failure modes in the non-linear phase. The bond stress of G16-1 and G16-3 degraded rapidly after the peak load. They then decreased gradually and remained stable with the loading process due to the peeling of ECC (see Figure 4, G16-1 and G16-3). The bond behavior has a secondary damage status, and the load will be reduced rapidly after a slip of 5 mm. During the pull-out tests of G16-1 and G16-3, the ECC at the interface is more prone to cohesive failure than to interfacial debonding from GFRP with a diameter of 16 mm. However, interfacial debonding of G16-2 would happen due to there being a higher fiber content of ECC at the interface than in G16-1 and G16-3.

The differences in bond behavior between G13 and G19 are not significant, except the bond strength. The interface damage areas of specimens are shown in Figure 4. Dark areas can be clearly observed on the surfaces of GFRP bars; these illustrate the splitting of their sand coating. The interfaces between GFRP bars and G13 ECC were totally damaged due to the slight Poisson's effect. Increasing Poisson's effect due to diameter increase resulted in different failure modes in the G16 specimens. In this study, the Poisson's effect is reflected in the reduction of the bond strength of specimens and different failure modes of the interface between ECC and GFRP. Different failure modes of bonds can also be found in the study of Zhou L. Z. et al. (2020). The applied load of the FRP bar leads to transverse deformation. Then, the transverse deformation leads to premature debonding of FRP bar and ECC and influences the bond behavior. An increase in diameter from 13 to 19 mm resulted in a significant Poisson's effect. Slight damage was observed in the interface of G19 specimens due to the increasing Poisson's effect. This phenomenon can also be found in the literature (Baena et al., 2009; Li et al., 2017; Di et al., 2018; Naik et al., 2019). It can be summarized that the Poisson's effect influences the bond behavior of GFRP bars more significantly than steel bars for the following reasons: (1) the low elastic modulus of FRP bars; (2) the small height of FRP ribs; (3) the low strength of FRP ribs.

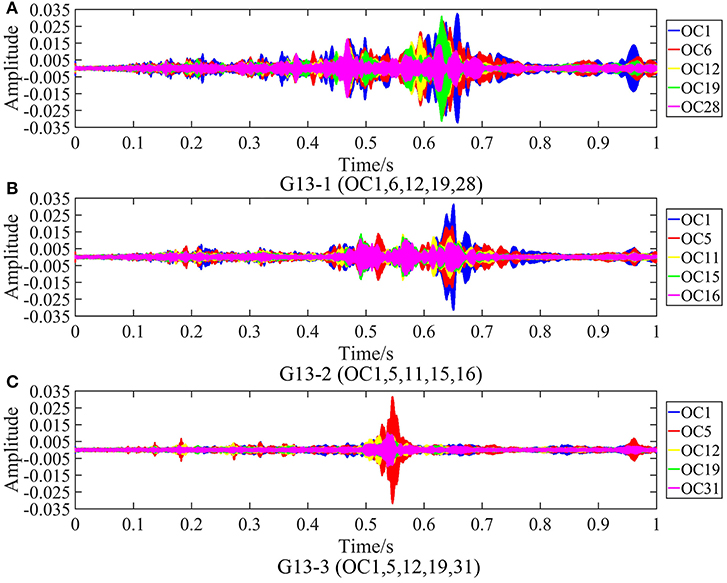

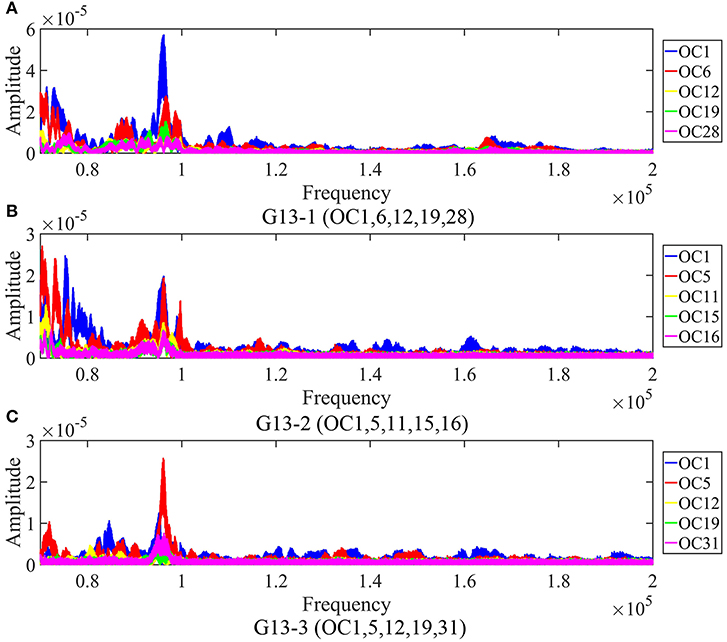

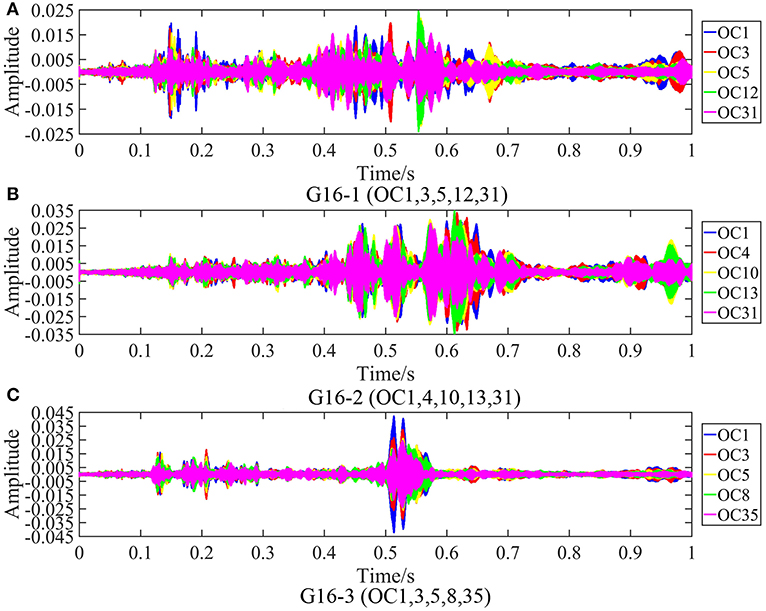

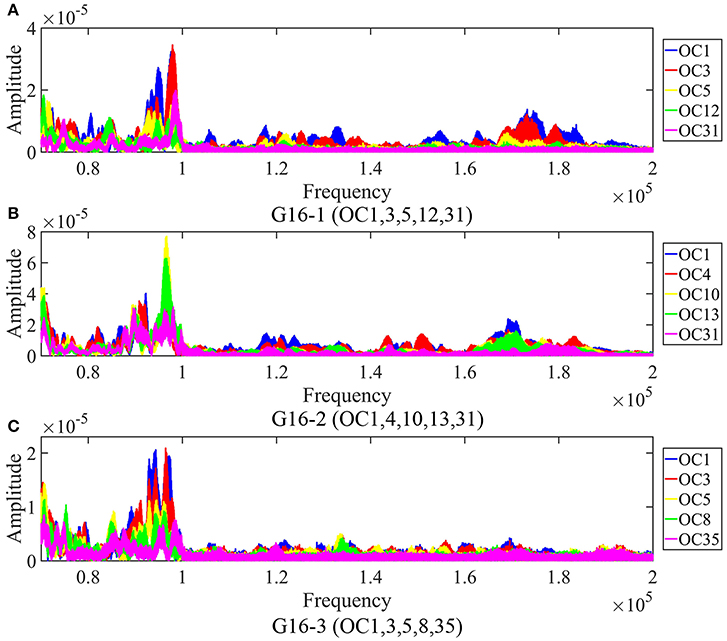

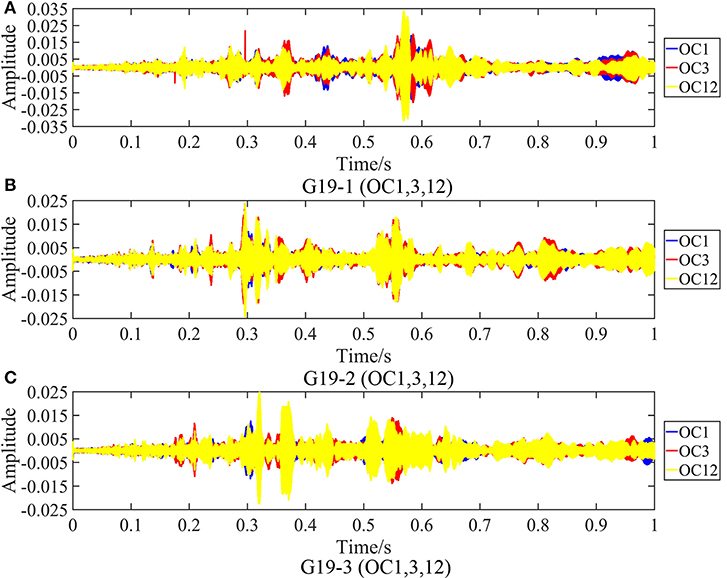

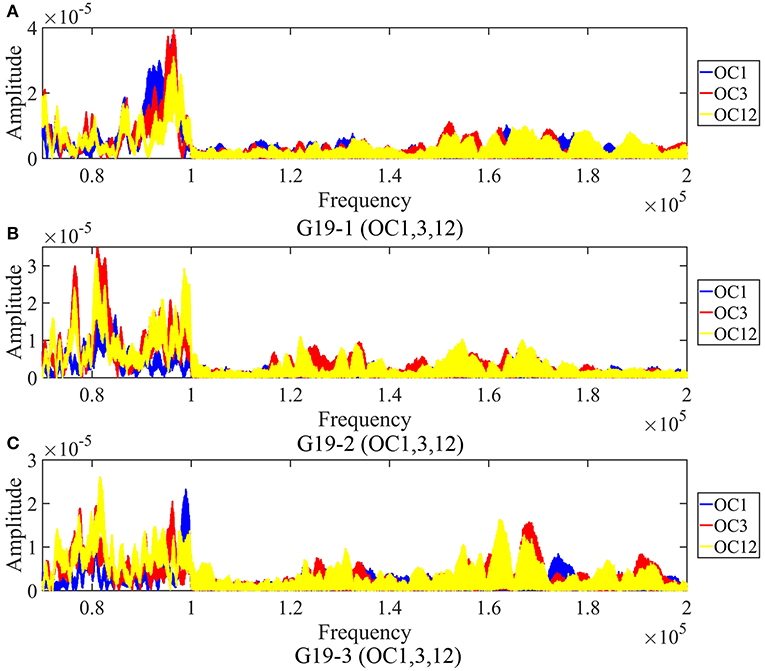

Time- and frequency-domain analysis can be used to investigate the damage status of specimens (Wu and Chang, 2006a,b; Han et al., 2019; Zhou Y. et al., 2020). The signals received are shown in Figures 5–10. An obvious decrease in the amplitude and the signal attenuation intensity of the time-domain signal was observed after operating condition 1 (see Figure 5). This is due to the failure of the bolted connection of the interface between GFRP bars and ECC. The signal amplitude reflects the damage status of the interface between ECC and GFRP bars. The premature debonding can be detected in the G13 specimens in operating condition 5. After testing under operating condition 12 (the operating condition of specimen G13-2 is 11), the amplitude of the time-domain signal remains steady due to failure debonding of the interface. Compared with the time-domain signal, the premature debonding can be more clearly observed through frequency-domain signal analysis due to the decomposition of stress wave frequency (see Figure 6). The increase in Poisson's effect of GFRP bars with a diameter of 16 mm compared to G13 leads to moderate degeneration of the received single (see Figure 7). The signal attenuations of G16-1 and G16-3 are more remarkable than that of G16-2, as shown in Figures 7A,C, due to the cohesive failure of the interface between GFRP bars and ECC. The cohesive failure of G16-1 and G16-3 resulted in significant energy dissipation of the stress wave, and the large signal energy dissipation of G16-1 and G16-3 then leads to significant signal attenuation. Due to the interfacial debonding at the interface between ECC and FRP bars, the attenuation of the received signal of G16-2 is less than that of G16-1 and G16-3 (see Figure 7B). Different failure modes can be investigated through both the time- and the frequency-domain signal (see Figure 8). However, the frequency-domain signal is more suitable for GFRP bar with a diameter of 16 mm, and the attenuation of the received signal of G16-1 and G16-3 can be observed more clearly than that of G16-2 due to the significant damage of the interface. The time-domain signal amplitude of G19 decreased slowly due to the remarkable Poisson's effect (see Figure 9). This is also evidenced by the fact that no severe damage was observed of the interface between ECC and GFPR bars, as described above. The attenuation trend of the frequency-domain signal is similar to that of the time-domain signal, as shown in Figure 10. The amplitude of the frequency-domain signal decreased slightly during the loading process. Frequency within the range 120–200 kHz is suitable for detecting the interfacial damage status.

Figure 5. Time domain of G13 after testing under different operating conditions. (A) Time domain of G13-1 under different operating conditions. (B) Time domain of G13-2 under different operating conditions. (C) Time domain of G13-3 under different operating conditions.

Figure 6. Frequency-domain signal of G13 after testing under different operating conditions. (A) Frequency domain of G13-1 under different operating conditions. (B) Frequency domain of G13-2 under different operating conditions. (C) Frequency domain of G13-3 under different operating conditions.

Figure 7. Time domain of G16 after testing under different operating conditions. (A) Time domain of G16-1 under different operating conditions. (B) Time domain of G16-2 under different operating conditions. (C) Time domain of G16-3 under different operating conditions.

Figure 8. Frequency-domain signal of G16 after testing under different operating conditions. (A) Frequency domain of G16-1 under different operating conditions. (B) Frequency domain of G16-2 under different operating conditions. (C) Frequency domain of G16-3 under different operating conditions.

Figure 9. Time domain of G16 after testing under different operating conditions. (A) Time domain of G19-1 under different operating conditions. (B) Time domain of G19-2 under different operating conditions. (C) Time domain of G19-3 under different operating conditions.

Figure 10. Frequency-domain signal of G16 after testing under different operating conditions. (A) Frequency domain of G19-1 under different operating conditions. (B) Frequency domain of G19-2 under different operating conditions. (C) Frequency domain of G19-3 under different operating conditions.

To quantify the interfacial damage status of the interface between GFRP bars and ECC, a DI analysis method was used in this paper, as shown in Figures 11–13. OC1 means the healthy status of the specimen before the pull-out test, which means chemical debonding of the interface. The DI values of G13 increased to 0.312, 0.4, and 0.3, while the extensions under this operating condition are relatively small (0.0302, 0.035, and 0.08 mm, respectively). After maximum load had been reached, the average DI value of G13 increased to about 0.6. It is noted that the sand coat damage of GFRP bars results in deterioration of the interface after the peak bond strength. After the mechanical bond failure, the DI values of G13 are increased slightly. At the end of loading, the DI of G13 was maintained at a high level (about 0.7) due to the small diameter and the sand-coat splitting of the GFRP bars, as shown in Figure 4. The bond-slip behavior of G13 can be detected precisely. Compared to the time-domain signal and frequency-domain signal, the DI method is more sensitive to debonding defects in ECC and GFPR bar pull-out tests with a reinforcement diameter of 13 mm. Moreover, the DI method can be utilized to quantify the damage severity of the pull-out specimen.

The cohesive failures of G16 were observed at the early stage of the experiment (see Figure 12). After the chemical failure, the DI values of G16-1 and G16-3 increased to 0.25 and 0.4. The slip values at this operating condition are relatively small (0.302 and 0.9 mm). It is indicated that the mechanical failure was affected by the partial damage of the interface. The initial debonding displacement of G16-2 is smaller than that of G16-1 and G16-3 (see Figure 12) due to the integration of the interface between ECC and FRP bar. After the mechanical failure of G16-2, the subsequent interfacial degeneration of G16-2 developed more slowly than that of G16-1 and G16-3. The damage status of the interface between ECC and FRP bars has a significant effect on the degradation after mechanical failure. The final DI values of G16 were lower than that of G13 due to the Poisson's effect of GFRP bar. It can be concluded that not only can the DI method be used to detect the change in the degree of interface damage with change in the diameter of the reinforcement but can also detect the interface failure mode.

It is obvious that a large diameter GFPR bar resulted in low bond strength, as shown in Figure 13. At the beginning of the pull-out tests for G19, the DI values increased significantly due to the chemical debonding of the interface between ECC and FRP bars, caused by a significant Poisson's effect. Decreasing the load of the experiment after the peak load leads to a decrease in the Poisson's effect of the GFRP bars. The DI values began to decline again. The chemical debonding of the interface can be clearly observed by DI values, unlike with the time- and frequency-domain signals. It is necessary to consider the influence of the Poisson's effect on the DI method for specimens with large-diameter GFRP bar.

The slip values of the premature debonding and failure debonding corresponding to the DI method are listed in Table 2. In this table, spre and sfai are the slip values of the premature debonding and the failure debonding based on the DI method. DIpre and DIfai are the DI values corresponding to the spre and sfai. tpre and tfai are the premature debonding and the failure debonding based on the experimental results, respectively. According to the calculated results, the slip values based on the DI method coincide with the test results. The interfacial damage of ECC and GFRP bars causes part of the stress wave to be reflected, passed, and bypassed. Change in the load process affected the proportion of reflected, passed, and bypassed waves. Therefore, there is little deviation between the DI change and the loading process. The average values of spre and sfai for G13 are 0.276 and 0.64, respectively. The spalling of ECC affected the DI of G16. According to the G16-1 and G16-3 specimens, the average DI of the premature debonding is 0.33. After the failure debonding, the average DI is 0.367. The development of the DI is relatively slow compared with that of G13 due to the interface damage. The GFRP bar with a diameter of 16 mm has a lower DI than that of G13. The DI values of the premature debonding and the failure debonding of G16-2 are 0.058 and 0.1, respectively. It can be summarized that the DI method can be utilized to detect the different interfacial failure modes. GFRP bar with a diameter of 16 mm has a positive effect on the cooperative deformation ability of the GFRP and ECC. However, it is necessary to calculate the appropriate anchorage length to avoid ECC spalling. Specimens of G19 have the largest DI values for the premature debonding and failure debonding compared with G13 and G16. The corresponding average values of DI are 0.619 (excluding the data of G19-3) and 0.678, respectively. The remarkable Poissons' effect of GFRP bar with a diameter of 19 mm has a negative effect on the bond-slip behavior of ECC and GFRP bars. The DI of the premature debonding is 124% higher than that of G13. It can be summarized that the bond failure of 19 mm GFRP will occur prematurely in ECC. According to the analysis results, it is reasonable that the DI is no more than 0.5.

As a means of studying the bond behavior of ECC and GFRP bars, a series of pull-out experiments were conducted. A theoretical analysis of wavelet packet-based DI was then performed. The experimental results match well and show that the degeneration of the interface can be detected by smart aggregate. The main findings are summarized as follows:

1. The Poisson's effect can be reflected in the reduction of the bond strength of ECC and GFRP. The Poisson's effect influences the bond behavior of GFRP bars significantly for the following reasons: (1) the low elastic modulus of FRP bars; (2) the small height of FRP rib; (3) the low strength of FRP rib.

2. It is evident that the specimens of G16 have different failure modes due to the Poisson's effect, which indicates that the bond-slip behavior and the Poisson's effect combined can extend the understanding of pull-out tests of FRP and ECC.

3. The damage of ECC results in sudden mechanical damage at the interface between ECC and FRP bar. The DI method is sensitive to detecting this brittle bond failure, which is crucial for investigating the bond interface damage of ECC and GFRP bar.

4. Compared with the time- and frequency-domain signals, the DI method based on the wavelet packet is more sensitive and accurate regarding the debonding behavior of the pull-out specimen.

5. The residual DI decreased with an increase in the diameter of the reinforcement. The Poisson's effect should be considered in the analysis of the DI of large-diameter reinforcement.

6. The slip values obtained via the DI method coincide with those from the experimental results. The DI of GFRP in ECC should be no more than 0.5. Bond failure of GFRP with a diameter of 19 mm will occur prematurely in ECC.

7. It is feasible to detect the interfacial damage behavior between ECC and FRP bars by using piezoceramic transducers. The detection method in this paper warrants a more detailed investigation into the bond-slip behavior of ECC and FRP bars.

All datasets generated for this study are included in the article/supplementary material.

YZ, SH, and LZ conceived and designed the study. LZ, JY, and LX performed the experiments. LZ and YZ wrote the paper. YZ, SH, and LZ reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was financially supported by the Key Research Project by Department of Education of Guangdong Province, China (2018KZDXM068 and 20185071401603), the Key Platforms and Major Scientific Research Projects in Universities in Guangdong Province (Grant No. 2016KZDXM053), the Innovation Group Supported by Department of Education of Guangdong Province (2019KCXTD013), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant number 51678149), the Key Program of National Natural Science of China (Grant number 51739008 and 51527811), the National Key Research and Development Program of China (No.2016YFC0401902), and Guangdong Science and Technology Planning (2016A010103045).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

I would like to show my deepest gratitude to my supervisors, YZ and SH, who have provided me with valuable guidance in every stage of the writing of this article. I would also like to thank JY and LX, who helped me to develop the experiment.

ACI 440.3R-04 (2004). Guide Test Methods for Fiber-Reinforced Polymers (FRPs) for Reinforcing or Strengthening Concrete Structures, ACI Committee 440. Farmington Hillsm MI: American Concrete Institute.

Baena, M., Torres, L., Turon, A., and Barris, C. (2009). Experimental study of bond behaviour between concrete and FRP bars using a pull-out test. Compos. Part B Eng. 40, 784–797. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2009.07.003

Bai, L., Yu, J., Zhang, M., and Zhou, T. (2019). Experimental study on the bond behaviour between H-shaped steel and engineered cementitious composites. Construct. Build. Mater. 196, 214–232. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.117

Caner, A., Dogan, E., and Zia, P. (2002). Seismic performance of multisimple-span bridges retrofitted with link slabs. J. Bridge Eng. 7, 85–93. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)1084-0702(2002)7:2(85)

Chai, L. J., Guo, L. P., Chen, B., and Xu, Y. H. (2018). Interactive effects of freeze-thaw cycle and carbonation on tensile property of ecological high ductility cementitious composites for bridge deck link slab. Construct. Build. Mater. 186, 773–781. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.07.248

Di, B., Wang, J. K., Li, H. T., Zheng, J. H., Zheng, Y., and Song, G. B. (2018). Investigation of bonding behavior of FRP and steel bars in self-compacting concrete structures using acoustic emission method. Sensors 19:159. doi: 10.3390/s19010159

Dumoulin, C., Karaiskos, G., Sener, J. Y., and Deraemaeker, A. (2014). Online monitoring of cracking in concrete structures using embedded piezoelectric transducers. Smart Mater. Struct. 23:115016. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/23/11/115016

Feng, Q., Kong, Q., and Song, G. (2016). Damage detection of concrete piles subject to typical damage types based on stress wave measurement using embedded smart aggregates transducers. Measurement 19:425. doi: 10.1016/j.measurement.2016.01.042

Firas, S. A., Gilles, F., and Robert, L. R. (2011). Bond between carbon fiber-reinforced polymer (CFRP) bars and ultra high performance fiber reinforced concrete (UHPFRC): experimental study. Constr. Build. Mater. 25, 479–485. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2010.02.006

Gao, S., Zhao, X., Qiao, J., Guo, Y., and Hu, G. (2019). Study on the bonding properties of Engineered Cementitious Composites (ECC) and existing concrete exposed to high temperature. Constr. Build. Mater. 196, 330–344. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.11.136

Ge, W. J., Ashour, A. F., Cao, D. F., Lu, W. G., Gao, P. Q., Yu, J. M., et al. (2019). Experimental study on flexural behaviour of ECC-concrete composite beams reinforced with FRP bars. Comp. Struct. 208, 454–465. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2018.10.026

Han, F., Jiang, J., Xu, K., and Wang, N. (2019). Damage detection of common timber connections using piezoceramic transducers and active sensing. Sensors 19:2486. doi: 10.3390/s19112486

Hossain, K. M. A. (2018). Bond strength of GFRP bars embedded in engineered cementitious composite using RILEM beam testing. Int. J. Concrete Struct. Mater. 12:6. doi: 10.1186/s40069-018-0240-0

Huo, L., Li, X., Chen, D., Li, H., Zhang, C., Hao, J., et al. (2017). Identification of the impact direction using the beat signals detected by piezoceramic sensors. Smart Mater. Struct. 26:085020. doi: 10.1088/1361-665X/aa7254

Jiang, T., Kong, Q., Patil, D., Luo, Z., Huo, L., and Song, G. (2017). Detection of debonding between fiber reinforced polymer bar and concrete structure using piezoceramic transducers and wavelet packet analysis. IEEE Sens. J. 17, 1992–1998. doi: 10.1109/JSEN.2017.2660301

Kim, B., Doh, J. H., Yi, C. K., and Lee, J. Y. (2013). Effects of structural fibres on bonding mechanism changes in interface between GFRP bar and concrete. Compos. Part B 45, 768–779. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2012.09.039

Lepech, M. D., and Li, V. C. (2010). Sustainable pavement overlays using engineered cementitious composites. Int. J. Pavement Res. Technol. 3, 241–250. doi: 10.6135/ijprt.org.tw/2010.3(5).241

Li, C. C., Gao, D. Y., Wang, Y. L., and Tang, J. Y. (2017). Effect of high temperature on the bond performance between basalt fiber reinforced polymer (BFRP) bars and concrete. Constr. Build. Mater. 141, 44–51. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2017.02.125

Li, S., Geissert, D. G., Li, S. E., Frantz, G. C., and Stephens, E. J. (1997). Durability and bond of high-performance concrete and repaired Portland cement concrete. Diss. Abstr. Int. 58:2022.

Li, V. C. (1998). Engineered cementitious composites–tailored composites through micromechanical modeing. Fiber Reinforced Concr. Pres. Fut. 1, 1–38. doi: 10.3151/jact.1.215

Li, V. C., Wang, S., and Wu, C. (2001). Tensile strain-hardening behaviour of PVA-ECC. ACI Mater. J. 98, 483–492. doi: 10.1016/S0379-6779(01)00519-7

Martinelli, E., and Caggiano, A. (2014). A unified theoretical model for the monotonic and cyclic response of FRP strips glued to concrete. Polymers 6, 370–381. doi: 10.3390/polym6020370

Mazaheripour, H., Barros, J. A. O., Sena-Cruz, J. M., Pepe, M., and Martinelli, E. (2013). Experimental study on bond performance of GFRP bars in self-compacting steel fiber reinforced concrete. Compos. Struct. 95, 202–212. doi: 10.1016/j.compstruct.2012.07.009

Naik, D. L., Sharma, A., Chada, R. R., Kiran, R., and Sirotiak, T. (2019). Modified pull-out test for indirect characterization of natural fiber and cementitious matrix interface properties. Construct. Build. Mater. 208, 381–393. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2019.03.021

Nayal, R., and Rasheed, H. A. (2006). Tension stiffening model for concrete beam reinforced with steel and FRP bars. J. Mater. Civ. Eng. 18, 831–841. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0899-1561(2006)18:6(831)

Özbay, E., Sahmaran, M., Yücel, H. E., Erdem, T. K., Lachemi, M., and Li, V. C. (2013). Effect of sustained flexural loading on self-healing of engineered cementitious composites. J. Adv. Concrete Technol. 11, 167–179. doi: 10.3151/jact.11.167

Qin, F., Kong, Q., Li, M., Mo, Y. L., Song, G., and Fan, F. (2015). Bond slip detection of steel plate and concrete beams using smart aggregates. Smart Mater. Struct. 24:115039. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/24/11/115039

Sherir, M., Hossain, K., and Lachemi, M. (2015). Structural performance of polymer fiber reinforced engineered cementitious composites subjected to static and fatigue flexural loading. Polymers 7, 1299–1330. doi: 10.3390/polym7071299

Song, G., Gu, H., Mo, Y. L., Hsu, T. T. C., and Dhonde, H. (2007a). Concrete structural health monitoring using embedded piezoceramic transducers. Smart Mater. Struct. 16, 959–968. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/16/4/003

Song, G., Olmi, C., and Gu, H. (2007b). An overheight vehicle–bridge collision monitoring system using piezoelectric transducers. Smart Mater. Struct. 16:462. doi: 10.1088/0964-1726/16/2/026

Sui, L., Zhong, Q., Yu, K., Xing, F., Li, P., and Zhou, Y. (2018). Flexural fatigue properties of ultra-high performance engineered cementitious composites (UHP-ECC) reinforced by polymer fibers. Polymers 10:892. doi: 10.3390/polym10080892

Wang, B., Huo, L., Chen, D., Li, W., and Song, G. (2017). Impedance-based prestress monitoring of rock bolts using a piezoceramic-based smart washer—a feasibility study. Sensors. 17:0250. doi: 10.3390/s17020250

Wang, F., Ho, S., Huo, L., and Song, G. (2018). A novel fractal contact-electromechanical impedance model for quantitative monitoring of bolted joint looseness. IEEE Access 6, 40212–40220. doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2018.2855693

Wang, H., Sun, X., Peng, G., Luo, Y., and Ying, Q. (2015). Experimental study on bond behaviour between BFRP bar and engineered cementitious composite. Construct. Build. Mater. 95, 448–456. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2015.07.135

Won, J. P., Park, C. G., Kim, H. H., Lee, S. W., and Won, C. (2008). Effect of fibers on the bonds between FRP reinforcing bars and high-strength concrete. Compos. Part B 39, 749–755. doi: 10.1016/j.compositesb.2007.11.005

Wu, F., and Chang, F. K. (2006a). Debond detection using embedded piezoelectric elements for reinforced concrete structures—Part II: analysis and algorithm. Struct. Health Monitor. 5, 5–15. doi: 10.1177/1475921706057978

Wu, F., and Chang, F. K. (2006b). Debond detection using embedded piezoelectric elements for reinforced concrete structures—Part II: analysis and algorithm. Struct. Health Monitor. 5, 17–28. doi: 10.1177/1475921706057979

Xu, B., Li, B., and Song, G. (2012). Active debonding detection for large rectangular CFSTs based on wavelet packet energy spectrum with piezoceramics. J. Struct. Eng. 139, 1435–1443. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)ST.1943-541X.0000632

Xu, B., Zhang, T., Song, G., and Gu, H. (2013). Active interface debonding detection of a concrete-filled steel tube with piezeoelectric techniques using wavelet packet analysis. Mech. Syst. Signal Process 36, 7–17. doi: 10.1016/j.ymssp.2011.07.029

Xu, J., Wang, C., Li, H., Zhang, C., Hao, J., and Fan, S. (2018c). Health monitoring of bolted spherical joint connection based on active sensing technique using piezoceramic transducers. Sensors 18:1727. doi: 10.3390/s18061727

Xu, K., Deng, Q., Cai, L., Ho, S., and Song, G. (2018a). Damage detection of a concrete column subject to blast loads using embedded piezoceramic transducers. Sensors. 18:1377. doi: 10.3390/s18051377

Xu, K., Ren, C., Deng, Q., Jin, Q., and Chen, X. (2018b). Real-time monitoring of bond slip between GFRP bar and concrete structure using piezoceramic transducer-enabled active sensing. Sensors. 18:2653. doi: 10.3390/s18082653

Yuan, F., Pan, J. L., and Leung, C. K. Y. (2013). Flexural behaviours of ECC and concrete/ECC composite beams reinforced with basalt fiber-reinforced polymer. J. Compos. Construct. 17, 591–602. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)CC.1943-5614.0000381

Zhang, J., Xu, J., Guan, W., and Du, G. (2018). Damage detection of concrete-filled square steel tube (CFSST) column joints under cyclic loading using piezoceramic transducers. Sensors 18:3266. doi: 10.3390/s18103266

Zhang, Q., and Li, V. C. (2014). Adhesive bonding of fire-resistive engineered cementitious composites (ECC) to steel. Construct. Build. Mater. 64, 431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2014.04.059

Zheng, Y., Zhang, L. F., and Xia, L. P. (2018a). Investigation of the behaviour of flexible and ductile ECC link slab reinforced with FRP. Construct. Build. Mater. 166, 694–711. doi: 10.1016/j.conbuildmat.2018.01.188

Zheng, Y., Zhou, L., Xia, L., Luo, Y., and Taylor, S. E. (2018b). Investigation of the behaviour of SCC bridge deck slabs reinforced with BFRP bars under concentrated loads. Eng. Struct. 171, 500–515. doi: 10.1016/j.engstruct.2018.05.105

Zhou, L. Z., Zheng, Y., Li, H. T., and Song, G. B. (2020). Identification of bond behaviour between FRP/steel bars and self-compacting concrete using piezoceramic transducers based on wavelet energy analysis. Arch. Civil Mech. Eng. 37, 1–36. doi: 10.1007/s43452-020-00041-1

Zhou, Y., Cai, J., Hou, D., Chang, H., and Yu, J. (2020). The inhibiting effect and mechanisms of smart polymers on the transport of fluids throughout nano-channels. Appl. Surf. Sci. 500:144019. doi: 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.144019

Zhou, Y., Hou, D., Jiang, J., Liu, L., She, W., and Yu, J. (2018). Experimental and molecular dynamics studies on the transport and adsorption of chloride ions in the nano-pores of calcium silicate phase: the influence of calcium to silicate ratios. Micropor. Mesopor. Mater. 255, 23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.micromeso.2017.07.024

Zhou, Y., Hou, D., Manzano, H., Orozco, C. A., Geng, G., Monteiro, P. J., et al. (2017). Interfacial connection mechanisms in calcium–silicate–hydrates/polymer nanocomposites: a molecular dynamics study. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 9, 41014–41025. doi: 10.1021/acsami.7b12795

Keywords: ECC, GFRP bar, pull-out test, smart aggregate, damage index

Citation: Zhang L, Zheng Y, Hu S, Yang J and Xia L (2020) Identification of Bond-Slip Behavior of GFRP-ECC Using Smart Aggregate Transducers. Front. Mater. 7:165. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2020.00165

Received: 28 December 2019; Accepted: 05 May 2020;

Published: 19 June 2020.

Edited by:

Yingwu Zhou, Shenzhen University, ChinaReviewed by:

Faiz Uddin Ahmed Shaikh, Curtin University, AustraliaCopyright © 2020 Zhang, Zheng, Hu, Yang and Xia. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yu Zheng, emhlbmd5QGRndXQuZWR1LmNu; Shaowei Hu, aHVzaGFvd2VpQG5ocmkuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.