- 1Collaborative Innovation Center of Sustainable Energy Materials, Guangxi Key Laboratory of Processing for Non-Ferrous Metaland Featured Materials, Guangxi University, Nanning, China

- 2Guangxi Ramway New Energy Corp., Ltd., Wuzhou, China

- 3College of Chemistry Biology and Environmental Engineering, Xiangnan University, Chenzhou, China

- 4Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Advanced Materials for New Energy Storage and Conversion, Hunan University of Science and Technology, Xiangtan, China

Lithium-thionyl chloride batteries possess the highest specific energies of the batteries that are commercially available. These batteries also have high operating voltages, stable outputs, wide operating temperature ranges, and long storage lives and are of low cost. The main limitation of lithium-thionyl chloride batteries is their low discharge capacity at high discharge rates, which limits their commercial uses. In this study, a porous cathode carbon support was prepared by introducing ammonia bicarbonate as a pore-forming agent. The porous cathode carbon support that formed was systematically characterized by BET, SEM, and XRD. The support was then assembled into an ER18505M battery system, and the electrochemical performance of the battery was characterized. The effect of pore structure on the electrochemical performance was determined and enabled the preparation of a high capacity lithium-thionyl chloride battery with a high discharge rate.

Introduction

Lithium-thionyl chloride batteries have the highest specific energy of all of the batteries that are commercially available. Their volume-specific energy can be as high as 1,100 KWh/L, their weight-specific energy up to 590 WH/Kg, and storage lives up to 10 years. The annual self-discharge is <1%, and the battery can work in a wide temperature range from −45 to 85°C. They are widely used in instruments, computers, sensors, military applications, environmental detection, security, the Internet of things, and other fields. However, lithium-thionyl chloride batteries are only suitable for small- and micro-current power consumption applications, as the discharge capacity begins to reduce considerably at a rate of more than 0.05C (Iwamaru and Uetani, 1987; Holmes, 2001; Menachem and Yamin, 2004; Spotnitz et al., 2006; West et al., 2010; Li et al., 2011; Hu et al., 2019a,b).

The discharge reaction of lithium-thionyl chloride batteries is shown in reaction (1) (Schliakjer et al., 1979). The reaction products of the discharge reaction are sulfur and sulfur dioxide, which are dissolved in the remaining thionyl chloride. The lithium chloride that forms is insoluble in the thionyl chloride and is precipitated in the pores of the carbon cathode support. Lee et al. (2001) pointed out that in the battery discharge reaction process, the reaction product, lithium chloride, will block the pores of the carbon cathode support and strongly hinder the diffusion of thionyl chloride in the support. Thus the SOCl2 reduction rate control step changes from an “interface reaction between the cathode and electrolyte” to “diffusion of SOCl2 through the porous layer,” thus affecting the electrical performance of the lithium-thionyl chloride battery (Lee et al., 2001; Kim and Pyun, 2003; Zhang et al., 2018). The discharge performance of lithium-thionyl chloride batteries has previously been improved by adding metal phthalocyanine compounds to the cathode support (Liu et al., 2016; Gao et al., 2017, 2018). However, metal phthalocyanine compounds are expensive and difficult to synthesize. In addition to being able to catalyze the reduction of SOCl2, the metal phthalocyanine compounds have a characteristic annular structure with a large hole. In the current study, ammonia bicarbonate was rapidly decomposed into CO2, NH3, and H2O [reaction formula (2)] at high temperatures. The reaction products were completely discharged from the material in the form of gas to improve the pore-making ability of the cathode support. By adjusting the amount of NH4HCO3 used in the fabrication of the cathode support, holes of different sizes could be formed in the carbon support. This enabled the effect of pore structure on the electrical performance of lithium-thionyl chloride batteries to be studied.

Experimental

Fabrication of the Porous Cathode Carbon Support

Ammonium bicarbonate (NH4HCO3), diluted PTFE emulsion (60%), anhydrous ethanol (CH3CH2OH), and deionized water (H2O) were stirred in the mixer at a speed of 30 rpm for 2 min at a ratio of n%:5%:80%:16,000% (taking the weight of acetylene black as a reference, respectively, where n = 0, 1, 3, 5, 7). Next, 100 g of acetylene black and 5 g of electrolytic copper powder were added while stirring at a speed of 30 rpm. The slurry was stirred for 40 min to obtain a uniform dispersion. Finally, the slurry was dried at 180°C for 12 h, and the water, anhydrous ethanol, and ammonium bicarbonate were completely removed to furnish the porous carbon support material.

Characterization of the Porous Cathode Carbon Support

The porous cathode carbon support was examined using a scanning electron microscope (SU8820, Hitachi, Japan). Structural analysis of the porous cathode carbon support was conducted with a D/Max-III X-ray diffractometer (Rigaku, Japan) using a Cu Kα radiation source (λ = 0.154059 nm). The scanning range was set to 2θ = 5–80°, with a voltage of 40 kV and a current of 30 mA. The specific surface area, mesopores, and micropores of the cathode carbon support were measured with an ASAP 2460 surface area analyzer (Micrometeritics, USA). The specific surface area of the cathode support was measured by a multi-point BET, the mesoporous area (2~300 nm) was measured by the BJH adsorption method, and the micropores (<2 nm) were analyzed using the slit-pore HK method.

Electrochemical Testing

The cathode carbon support was immersed in analytically pure isopropanol [(CH3)2CHOH], pressed into a 0.65 ± 0.05 mm sheet film by a roller, and then cut into a diaphragm measuring 100 × 37 mm. The diaphragm was bonded to both sides of a nickel screen and then baked in an oven at 250°C for 10 min to prepare the positive electrode sheet. The positive plate, lithium foil, and a glass fiber membrane were then wound and assembled into the ER18505M cell under an atmosphere of nitrogen at a dew point humidity of −50°C. A total of 1.2 mol/L LiAlCl4/SOCl2 was then injected as electrolyte into the battery. The weights of the metal lithium foil and the injected electrolyte were measured on an analytical balance (BSA124S, Sartorius, Germany).

The AC impedance spectrum of the ER18505M battery before and after discharging was tested on an electrochemical workstation (Zahner IM6E, Germany). The test voltage was 3.65 V, the disturbance amplitude was 5 mV, and the frequency range was 10 KHz−0.01 Hz. The ER18505M battery was discharged at a current of 100 and 400 mA on a battery test system (Neware, China) at room temperature with the voltage discharge set to 2.0 V.

Results and Discussion

Morphology and Structure of the Porous Cathode Carbon Support

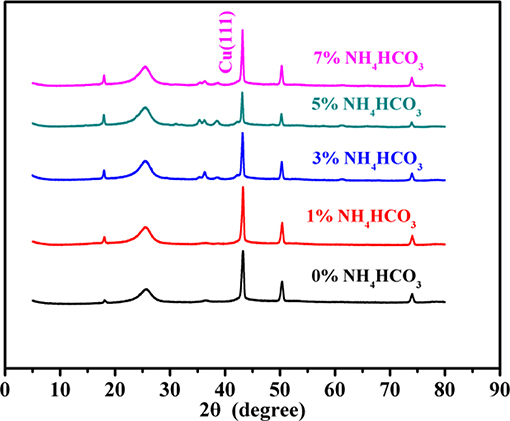

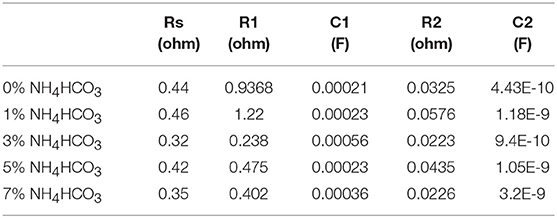

The macroscopic morphology of the carbon cathode support is shown in Figure 1A, an image of the uniform carbon-based Cathode carrier of the lithium-thionyl chloride battery, which has a flexible banded/membrane structure. The SEM images reveal (Figures 1B–F) that the carbon cathode support is formed through particle accumulation. The agglomerated surface particles are gradually dispersed from a compact to a loose configuration with increasing amounts of the pore-forming agent, NH4HCO3. XRD spectroscopy (Figure 2) reveals that the signal corresponding to carbon is the same in cathode supports formed in the presence of NH4HCO3 and without NH4HCO3. This indicates that ammonium bicarbonate decomposes into a gas at high temperatures. Thus, no NH4HCO3 or other nitrogen compounds exist within the carbon cathode support. The characteristic peaks for acetylene black (2θ = 25°) (Yang et al., 2007; Lian et al., 2008; Wei et al., 2017) and polytetrafluoroethylene (2θ = 36.7°, 37.1°, and 41.3°) (Shi et al., 2012) increased significantly after adding NH4HCO3, indicating an increase in the degree of crystallization. These results, combined with the SEM images, confirm that the PTFE and carbon units agglomerated into large particles in the cathode support. These were reduced in size by dispersion during the decomposition of NH4HCO3. At 2θ = 43.3°, 50.4°, and 74.1°, there was a characteristic peak corresponding to copper, and no peak corresponding to CuO or Cu2O was observed. However, the characteristic peak for copper did not appear to change before or after the addition of NH4HCO3, according to the “Scherrer equation” (Duan et al., 2018, 2019). Furthermore, the size of copper particles did not appear to change.

Figure 1. (A) Cathode carbon support, SEM images of carbon supports after annealing [(B): carbon support with 0% NH4HCO3, (C): carbon support with 1% NH4HCO3, (D): carbon support with 3% NH4HCO3, (E): carbon support with 5% NH4HCO3, (F): carbon support with 7% NH4HCO3).

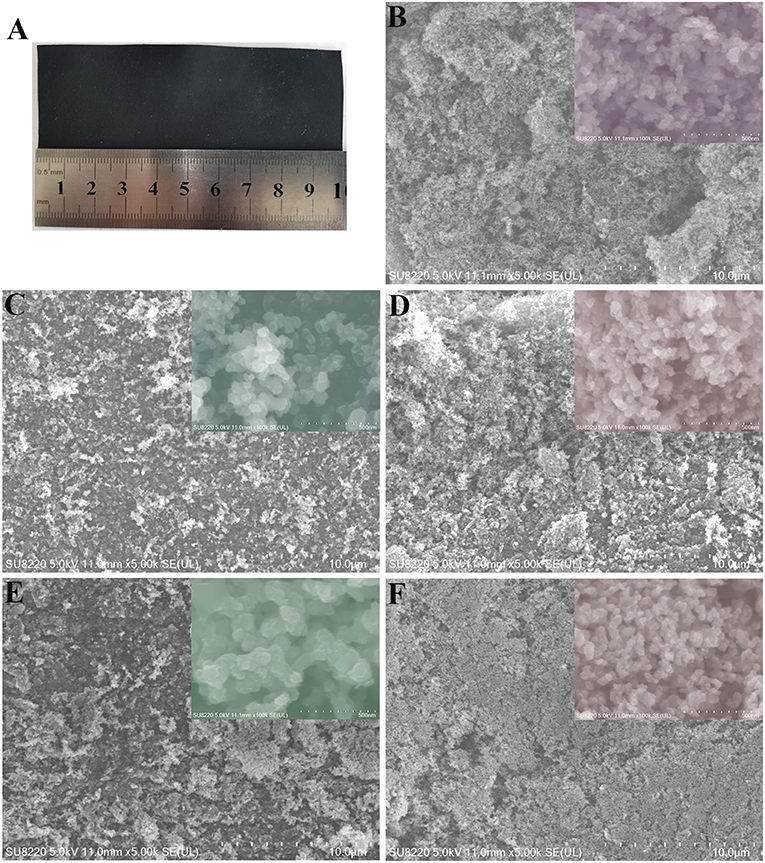

The isotherm adsorption and desorption curves for carbon cathode supports prepared with varying percentages of NH4HCO3 are shown in Figure 3A. The order of the BET specific surface areas of the five carbon cathode supports is as follows: 7% NH4HCO3 (51.41 m3/g) > 3% NH4HCO3 (49.496 m3/g) > 5% NH4HCO3 (48.316 m3/g) > 0% NH4HCO3 (48.303 m3/g) > 1% NH4HCO3 (47.375 m3/g). Figure 3B shows the pore size distribution of the different carbon cathode supports. There are a large number of micropores and mesopores in the carbon cathode support, of which micropores are dominant, which is a result of the non-qualitative carbon porous structure of acetylene black (Fan et al., 2009). The SEM images and XRD spectra together indicate that the gas overflow produced by the decomposition process of NH4HCO3 leads to the extension and fracturing of the PTFE, which acts as an adhesive. Extension of the PTFE chain produces more mesopores and increases the average diameter of the mesopores. When the PTFE chain breaks, the PTFE and carbon units form small particles, which will lead to a decrease in the mesoporous pore size and an increase in the number of micropores. Additionally, the degree of crystallization for acetylene black and PTFE increases. With increasing percentages of NH4HCO3, the extension of the PTFE chain gradually changes to fracturing, so that the volume and pore size of the mesopores formed initially increases and then decreases (Figures 3C,D). In this process, the micropores are largely unaffected by gas, so there is no corresponding relationship between the micropore structure and the NH4HCO3 content in the carbon cathode support (Figure 3C). Similarly, the specific surface area is determined by the dominant micropores, and no corresponding relationship was observed between the specific surface area and the amount of NH4HCO3.

Figure 3. (A) N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms, (B) Pore-size distribution curves, (C) Pore volume and the NH4HCO3 content curve, (D) Average pore size of mesopores and NH4HCO3 content curve.

Electrochemical Performance of the Battery

AC Impedance Spectrum

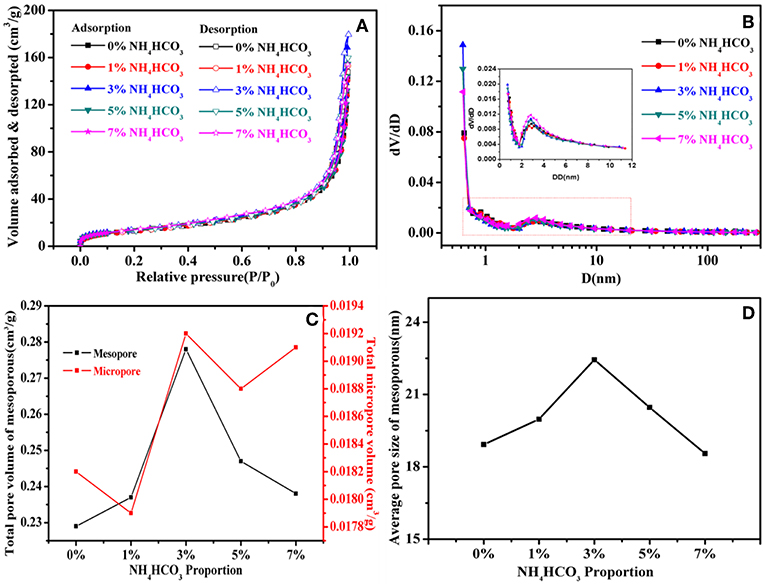

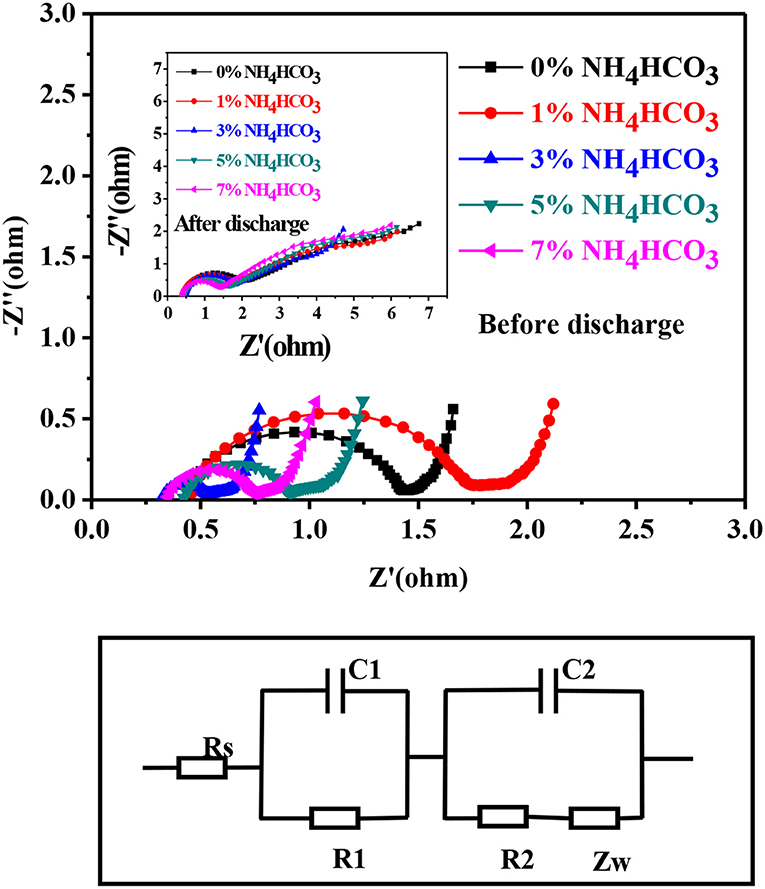

Figure 4 shows the Nyquist plots and the equivalent circuit diagram of the ER18505M cell before and after discharge at a current of 100 mA with different carbon cathode supports. The Nyquist plots are mainly composed of two semicircles, so they can be simulated with the equivalent circuit shown in Figure 4, where Rs, R1, R2, C1, C2, and Zw represent the solution resistance, porous carbon cathode surface film resistance, electron transfer resistance, film capacitance, double-layer capacitance, and diffusion impedance, respectively (Lee et al., 2001; Guo et al., 2009). The EIS-fitting results are shown in Table 1. The AC impedance spectrum before discharge shows that R1 (the diameter of the half arc in the high-frequency region) differs considerably for different cathode supports, which is due to the micropores and mesoporous holes in the carbon cathode support. The micropores play a dominant role in the pore composition, and differences in the size and number of micropores affect R1. The slope of the curve in the low-frequency region is near identical for the different supports, indicating that the diffusion rate of the lithium ions is comparable. This is because the lithium ions are adequately diffused in the SOCl2 solution before discharging. After discharging, the AC impedance spectrum shows that the Rs and R1 (semi-circular arc diameter in the high-frequency region) values of the different cathode carriers are similar, which indicates that the difference caused by the micropores has been lessened. It appears that the micropores are blocked by the reaction product LiCl (Zhang et al., 2018), so the resistance of the solution is dominated by the mesoporous holes, which are not completely blocked. The slope of the curve in the low-frequency region after discharging is lower than that before discharging. This indicates that diffusion of the lithium ions slows down due to the blockage of the pores as the battery is discharged (Wu et al., 2006; Zhu et al., 2019).

Figure 4. The Nyquist plot of an ER18505M cell before and after discharging at 100 mA (above), and the equivalent circuit of the ER18505M cell (below).

Battery Discharge Performance

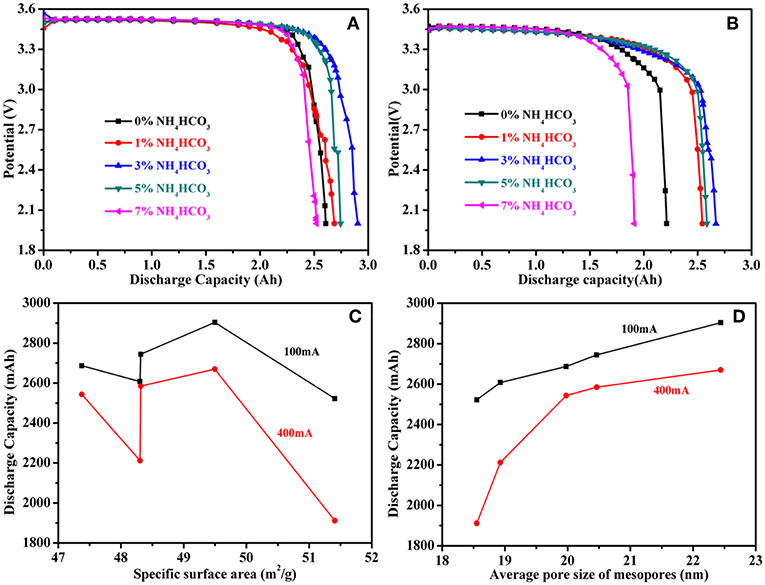

The ER18505M cells were continuously discharged at currents of 100 and 400 mA and voltages of down to 2.0 V at room temperature. The measured capacities at a current of 100 mA are 2.6076 Ah (0% NH4HCO3), 2.6869 Ah (1% NH4HCO3), 2.9037 Ah (3% NH4HCO3), 2.7443 Ah (5% NH4HCO3), and 2.522 Ah (7% NH4HCO3) (Figure 5A). The measured capacities at a current of 400 mA are 2.2119 Ah (0% NH4HCO3), 2.5431 Ah (1% NH4HCO3), 2.6697 Ah (3% NH4HCO3), 2.5849 Ah (5% NH4HCO3), and 1.9116 Ah (7% NH4HCO3) (Figure 5B). The discharge capacity with two modes of discharge show the same trend, 3% NH4HCO3 > 5% NH4HCO3 > 1% NH4HCO3 > 0% NH4HCO3 > 7% NH4HCO3. This indicates that the discharge performance of the battery can be improved by changing the pore structure of the carbon cathode support. Figure 5C shows the relationship between the specific surface area and the discharge capacity of the battery, and Figure 5D shows the relationship between the average pore size of the carbon cathode support and the discharge capacity of the battery. The discharge capacity shows no corresponding relationship with the specific surface area but has a positive correlation with the average size of the mesopores. The discharge capacity of the battery increases with an increase in the average pore size of the mesopores. This also shows that the discharge capacity of the battery is determined by the degree of blockage of the mesopores of the carbon cathode carrier. Because the micropores of the carbon cathode carrier are blocked during the discharge process of the battery, the final discharge capacity of the battery cannot be determined. No relationship therefore exists between the specific surface area within which the micropores are located and the discharge capacity of the battery. It can be seen from Figure 5D that the discharge capacity at 400 mA is more affected by the mesopore size than is the discharge capacity at 100 mA. This is because the larger the discharge current, the greater the sensitivity to the degree of pore blockage. It has been reported that porous carbon materials also show excellent high-rate capability and high energy storage capacity in other energy storage systems (Guo et al., 2018; Hou et al., 2018; Liu et al., 2018; Sun et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2019).

Figure 5. (A) The discharge capacity of the ER18505M cell at 100 mA, (B) the discharge capacity of the ER18505M cell at 400 mA, (C) the discharge capacity and specific surface area curve, (D) the discharge capacity vs. the average pore size of mesopores.

Conclusion

Micropores and mesopores in the carbon cathode support affect the discharge performance of lithium-thionyl chloride batteries. In the discharge reaction, the micropores are gradually blocked by LiCl, and the reduction rate of SOCl2 is determined by the mesopores, which are not completely blocked. The size of the mesopores determines the degree of blockage and directly affects the diffusion of thionyl chloride in the porous layer of the carbon cathode carrier. This, in turn, affects the discharge capacity of the battery. The structure of the mesopores in the carbon cathode support can be improved by the addition of ammonium bicarbonate during the fabrication of the carbon cathode support, and this therefore improves the discharge capacity of lithium-thionyl chloride batteries.

Data Availability Statement

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript/supplementary files.

Author Contributions

DW and JJ conducted the synthesis and parts of the characterization. ZP and QL carried out parts of the characterization and electrochemical measurements. DW, JZ, and LT co-wrote the manuscript. All authors discussed the data and commented on the manuscript.

Conflict of Interest

DW and QL were employed by company Guangxi RAMWAY New Energy Corp., Ltd.

The remaining authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (51962002), the Natural Science Foundation of Guangxi (2017GXNSFBA198103), Guangxi Science and Technology Project (AA18126006), and the Open Fund of Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Advanced Materials for New Energy Storage and Conversion (2018TP1037201903).

References

Duan, C., Cao, Y., Hu, L., Fu, D., Ma, J., and Youngblood, J. (2019). An efficient mechanochemical synthesis of alpha-aluminum hydride: synergistic effect of TiF3 on the crystallization rate and selective formation of alpha-aluminum hydride polymorph. J. Hazard. Mater. 373, 141–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2019.03.064

Duan, C. W., Hu, L. X., and Ma, J. L. (2018). Ionic liquids as an efficient medium for the mechanochemical synthesis of α-AlH3 nano-composites. J. Mater. Chem. A 6, 6309–6318. doi: 10.1039/C8TA00533H

Fan, C.-L., Su, Y.-C., and Xu, Z.-Y. (2009). The problem whether acetylene black should be added into the graphite negative electrode. J. Hunan Univ. 36, 66–69.

Gao, Y., Chen, L., Quan, M., Zhang, G., and Zhao, J. (2018). A series of new phthalocyanine derivatives with large conjugated system as catalysts for the Li/SOCl2 battery. J. Electroanal. Chem. 808, 8–13. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.11.062

Gao, Y., Li, S., Wang, X., Zhang, R., Zhang, G., Zheng, Y., et al. (2017). Binuclear metal phthalocyanines bonding with carbon nanotubes as catalyst for the Li/SOCl2 battery. J. Electroanal. Chem. 791, 75–82. doi: 10.1016/j.jelechem.2017.03.013

Guo, J. Z., Yang, Y., Liu, D. S., Wu, X. L., Hou, B. H., Pang, W. L., et al. (2018). A practicable Li/Na-ion hybrid full battery assembled by a high-voltage cathode and commercial graphite anode: superior energy storage performance and working mechanism. Adv. Energy Mater. 8:1702504. doi: 10.1002/aenm.201702504

Guo, Y.-S., Ge, H. H., Zhou, G. D., and Wu, Y. P. (2009). Comparative study on carbon cathodes with and without cobalt phthalocyanine in Li/(SOCl2 + BrCl) cells. J. Power Sources 194, 508–514. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2009.05.009

Holmes, C. F. (2001)The role of lithium batteries in modern health care. J. Power Sources. 97–98, 739–741. doi: 10.1016/S0378-7753(01)00601-2

Hou, B. H., Wang, Y. Y., Liu, D. S., Gu, Z. Y., Feng, X., Fan, H. S., et al. (2018). N-doped carbon-coated Ni1.8Co1.2Se4 nanoaggregates encapsulated in N-doped carbon nanoboxes as advanced anode with outstanding high-rate and low-temperature performance for sodium-ion half/full batteries, Adv. Funct. Mater. 28:1805444. doi: 10.1002/adfm.201805444

Hu, A., Shu, C., Qiu, X., Li, M., Zheng, R., and Long, J. (2019a). Improved cyclability of lithium–oxygen batteries by synergistic catalytic effects of two-dimensional MoS2 nanosheets anchored on hollow carbon spheres. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 7, 6929–6938. doi: 10.1021/acssuschemeng.8b06496

Hu, A., Shu, C., Xu, C., Liang, R., Li, J., Zheng, R., et al. (2019b). Design strategies toward catalytic materials and cathode structure for emerging Li–CO2 batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 7, 21605–21633. doi: 10.1039/C9TA06506G

Iwamaru, T., and Uetani, Y. (1987). Characteristics of a lithium-thionyl chloride battery as a memory back-up power source. J. Power Sources 20, 47–52. doi: 10.1016/0378-7753(87)80089-7

Kim, C.-H., and Pyun, S.-I. (2003). Growth kinetics of lithium chloride layer formed on porous carbon cathodes during discharge of Li-SOCl2 batteries. J. Eletrochem. Soc. 150, A1176–A1181. doi: 10.1149/1.1594728

Lee, S.-B., Pyun, S.-I., and Lee, E. -,J. (2001). Effect of the compactness of the lithium chloride layer formed on the carbon cathode on the electrochemical reduction of SOCl2 electrolyte in Li-SOCl2 batteries. Electrochim. Acta 47, 855–864. doi: 10.1016/S0013-4686(01)00813-1

Li, J., Daniel, C., and Wood, D. (2011). Materials processing for lithium-ion batteries. J. Power Sources 196, 2452–2460. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.11.001

Lian, W., Song, H., Chen, X., Li, L., Huo, J., Zhao, M., et al. (2008). The transformation of acetylene black into onion-like hollow carbon nanoparticles at 1000°C using an iron catalyst. Carbon 46, 525–530. doi: 10.1016/j.carbon.2007.12.024

Liu, D. S., Liu, D. H., Hou, B. H., Wang, Y. Y., Guo, J. Z., Ning, Q. L., et al. (2018). 1D porous MnO@N-doped carbon nanotubes with improved Li-storage properties as advanced anode material for lithium-ion batteries, Electrochim. Acta 264, 292–300. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2018.01.129

Liu, Z., Jiang, Q., Zhang, R., Gao, R., and Zhao, J. (2016). Graphene/phthalocyanine composites and binuclear metal phthalocyanines with excellent electrocatalytic performance to Li/SOCl2 battery. Electrochim. Acta 187, 81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2015.10.145

Menachem, C., and Yamin, H. (2004). High-energy, high-power Pulses Plus™ battery for long-term applications. J. Power Sources 136, 268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2004.03.011

Schliakjer, C. R., Goebel, F., and Marincic, N. (1979). Discharge reaction mechanisms in Li/SOCl2 cells. J. Eletrochem. Soc. 126, 513–522. doi: 10.1149/1.2129078

Shi, Z., Zhou, H., Dai, T., and Lu, Y. (2012). Poly(tetrafluoroethylene) composite membranes coated with urchin-like polyaniline hiberarchy: preparation and properties. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 385, 211–217. doi: 10.1016/j.jcis.2012.07.027

Spotnitz, R. M., Yeduvaka, G. S., Nagasubramanian, G., and Jungst, R. (2006). Modeling self-discharge of Li/SOCl2 cells. J. Power Sources 163, 578–583. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2006.09.025

Sun, Z., Wu, X. L., Peng, Z., Wang, J., Gan, S., Zhang, Y., et al. (2019). Compactly coupled nitrogen-doped carbon nanosheets/molybdenum phosphide nanocrystal hollow nanospheres as polysulfide reservoirs for high-performance lithium-sulfur chemistry. Small 15:1902491. doi: 10.1002/smll.201902491

Wang, Y. Y., Hou, B. H., Ning, Q. L., Pang, W. L., Rui, X. H., Liu, M. K., et al. (2019). Hierarchically porous nanosheetsconstructed 3D carbon network for ultrahigh-capacity supercapacitor and battery anode, Nanotechnology 30:214002. doi: 10.1088/1361-6528/ab043a

Wei, J. H., Gao, X. T., Tan, S. P., Wang, F., Zhu, X. D., and Yin, G. P. (2017). Acetylene black loaded on graphene as a cathode material for boosting the discharging performance of Li/SOCl2 battery. Int. J. Electrochem. Sci. 12, 898–905. doi: 10.20964/2017.02.01

West, W. C., Shevade, A., Soler, J., Kulleck, J., Smart, M. C., Ratnakumar, B. V., et al. (2010). Sulfuryl and thionyl halide-based ultralow temperature primary batteries. J. Electrochem. Soc. 157, A571–A577. doi: 10.1149/1.3353235

Wu, Y. P., Zhou, G. D., Ge, H. H., Xu, M. D., Wang, Q. J., and Qian, S. Y. (2006). AC impedance study on Li/SOCl2 cell. Battery Bimonthly 36, 175–177. doi: 10.3969/j.issn.1001-1579.2006.03.005

Yang, H.-M., Nam, W.-K., and Park, D.-W. (2007). Production of nanosized carbon black from hydrocarbon by a thermal plasma. J. Nanosci. Nano. 7, 3744–3749. doi: 10.1166/jnn.2007.003

Zhang, Z., Kong, L., Xiong, Y., Luo, Y., and Li, J. (2018). The synthesis of Cu(II), Zn(II), and Co(II) metalloporphyrins and their improvement to the property of Li/SOCl2 battery. J. Solid State Electrochem. 18, 3471–3477. doi: 10.1007/s10008-014-2571-3

Keywords: lithium-thionyl chloride battery, ammonia bicarbonate, carbon support, pore structure, capacity

Citation: Wang D, Jiang J, Pan Z, Li Q, Zhu J, Tian L and Shen PK (2019) The Effects of Pore Size on Electrical Performance in Lithium-Thionyl Chloride Batteries. Front. Mater. 6:245. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2019.00245

Received: 23 July 2019; Accepted: 18 September 2019;

Published: 14 October 2019.

Edited by:

Ru-Shi Liu, National Taiwan University, TaiwanReviewed by:

Fuming Chen, South China Normal University, ChinaXing-Long Wu, Northeast Normal University, China

Copyright © 2019 Wang, Jiang, Pan, Li, Zhu, Tian and Shen. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jinliang Zhu, amx6aHU4NUAxNjMuY29t; Li Tian, MTA2MDA3MkBobnVzdC5lZHUuY24=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work

Danghui Wang1,2†

Danghui Wang1,2† Jinliang Zhu

Jinliang Zhu