- 1School of Materials Science and Engineering, Institute of Graphene at Shaanxi Key Laboratory of Catalysis, Shaanxi University of Technology, Hanzhong, China

- 2School of Physics and Telecommunication Engineering, Shaanxi University of Technology, Hanzhong, China

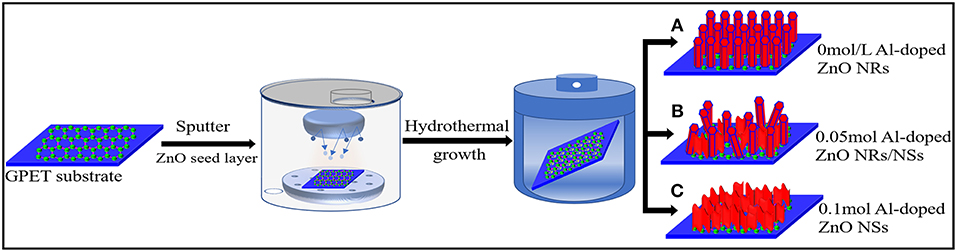

In this work, Al-doped ZnO (AZO) nanosheets (NSs) were successfully synthesized on graphene-coated polyethylene terephthalate (GPET) flexible substrate via hydrothermal method. Studies have indicated that with the addition of Al3+, the nanostructure of ZnO gradually grows from nanorods (NRs) to NSs, and the (100), (002), and (101) diffraction peak strength of ZnO that grows perpendicularly to the substrate along the c-axis weakened. The mechanism of hydrothermal growth of AZO/GPET was also studied. The electrochemical properties of the samples were investigated by cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS), and it was concluded that AZO NSs grown on GPET substrates has better capacitance performance than undoped ZnO NRs.

Introduction

Up to now, energy reserves and environmental contamination are still the focus of extensive attention, especially the problems of air pollution, water pollution, global warming, and renewable energy, which are closely linked with our lives. In order to solve these problems, batteries and supercapacitors have become research hotspots of electrochemical energy storage systems. Among them, supercapacitor (SC), is of great attention in the fields of automobiles (Cao and Emadi, 2011; Biplab et al., 2017), wind power systems (Abbey and Joos, 2007), solar cells (Narayanan et al., 2015; Xu et al., 2015), and so on, because of its great power density, lack of required maintenance, wide operating temperature range, green environmental protection, long cycling life, etc. (Zhao et al., 2011). In addition to those, SCs can provide high power pulses in a short period of time compared to conventional capacitors or storage batteries. SCs, for example, are often used for intelligent start-stop control systems (lightweight hybrid power system), which are particularly prominent in plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (Cao and Emadi, 2011). Due to the different energy storage mechanism, SCs can be divided into electric double-layer capacitors (EDLCs) and faraday pseudo-capacitors. The former generates and stores energy by adsorption of a pure electrostatic charge on the electrode surface and the latter uses redox reaction to store electrical energy in an electrochemical manner (Liu et al., 2014). The properties of SCs are closely related to the electrode materials used, and examples of materials used in current research are: carbon materials (Salinas-Torres et al., 2019), metal oxides (Wu et al., 2018) and conductive polymers. Of all electrode materials, carbon materials with high specific surface area and low internal resistance receive more attention, including activated carbon fibers (Ren et al., 2013), carbon aerogel (Liu et al., 2018), carbon nanotubes (Futaba et al., 2006), activated carbon (Wang et al., 2014; Isabel et al., 2016), porous carbon (Yang et al., 2019), and graphene (Zhang et al., 2016; Ren et al., 2018).

The theoretical specific capacity of semiconductor oxides such as ZnO, SnO2, and TiO2 is 2,3 times that of graphite, which has attracted enormous attention. Among them, ZnO, as a n-type semiconductor, has tremendous senses for the fields of chemicals, electronics, and optics owing to its superior properties [i.e., a large exciton binding energy (60 meV) and a wide bandgap of about 3.3 eV at room temperature] (Klingshirn, 2010). In addition, as the electrode material of supercapacitor, ZnO has been paid more and more attention because of its advantages of high chemical stability and thermal stability, low cost, environment friendly, and easy doping. However, ZnO has the disadvantages of poor conductivity and large volume effect in the process of charging and discharging, which affects the practical application of ZnO as an electrode material. Graphene, a two-dimensional carbon nanomaterial with zero bandgap, is attracted much attention that as a prospective candidate electrode material for EDLCs due to its high carrier mobility, great chemical resistance, large surface area, high conductivity, and transparency (Han et al., 2014; Ren et al., 2018). However, the presence of Van der Waals makes graphene easy to reunite, thus reducing the specific surface area and specific capacity of graphene. Therefore, ZnO and graphene materials composite and doped, can achieve the complementary advantages of material properties.

Bhirud et al. prepared N-doped ZnO/graphene (NZO/GR) by situ wet chemical method and studied their electrochemical properties. It was observed, the specific capacitance of NZO/GR was 555 Fg−1, which was 529 Fg−1 and 20% higher than pure ZnO/GR (Bhirud et al., 2015). Cu/ZnO doped graphene nanocomposites was investigated by Jacob et al. (2018). Electrochemical analysis showed that the material has a specific capacity of 630 mAhg−1 and retains around 95% of this capacity after 100 cycles. Faraji and Ani (2014) reviewed the application of microwave-assisted metal oxide thin film electrodes in supercapacitors. And they noted that ZnO/GR composites have high specific capacitance and good reversible charge-discharge performance. Many previous studies have used the hummer method to prepare graphene to prepare ZnO/graphene nanoparticles (Wang et al., 2011; Bu and Huang, 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). Therefore, it is necessary to explore the preparation of ZnO nanofilms based on transparent conductive flexible graphene-coated polyethylene terephthalate (GPET) substrates.

In this paper, ZnO nanosheets (NSs) with different Al doped concentration on GPET substrates were fabricated by a simple-green hydrothermal method, and their electrochemical properties were studied. The effect of adding different concentrations of Al on electrochemical properties of ZnO composite nanostructures was compared.

Experimental

Synthesis of ZnO Nanosheets

The Al-doped ZnO (AZO) NSs with different concentrations were prepared on GPET substrates. The ZnO seed layer (about 30 nm thickness) was sputtered by radio frequency magnetron sputtering on the surface of GPET substrates, which used acetone (10 min), methanol (10 min), and deionized (DI) water to clean in turn by ultrasonic cleaning machines. In the hydrothermal growth process of AZO NSs, zinc nitrate hexahydrate (Zn (NO3)2·6H2O), and hexamethylenetetramine (C6H12N4) were mixed in DI water to prepare precursor solutions (30 ml). Then added aluminum oxide (Al2O3) as dopant to the solutions with the concentration of 0.1 and 0.05 mol/L, and kept stirring for 30 min under mild magnets. The precursor solutions were transferred to a Teflon-lined stainless-steel autoclave, and then the GPET substrates were immersed in it. After that, the autoclave was sealed and put into an oven, and heated at a temperature of 95°C for 6 h. The products on the substrates were washed with DI water and dried naturally at room temperature.

Structural Characteristics

Field emission scanning electron microscope (FESEM, by FEI Magellan 400) and X-ray diffraction (XRD, by Rigaku D/MAX-Ultima with Cu Kα radiation) were used to characterize the microscopic morphology and crystal structure of the samples, respectively.

Electrochemical Measurement

The cyclic voltammetry (CV) and electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) of the samples have used electrochemical workstation (CHI760E) to test. AZO NSs on GPET substrates as a working electrode, Ag/AgCl as a reference electrode, and platinum foil as counter electrode comprise the three-electrode test system. 1 mol/L Na2SO4 solution be used as electrolyte in this process of electrochemical measurement.

Results and Discussion

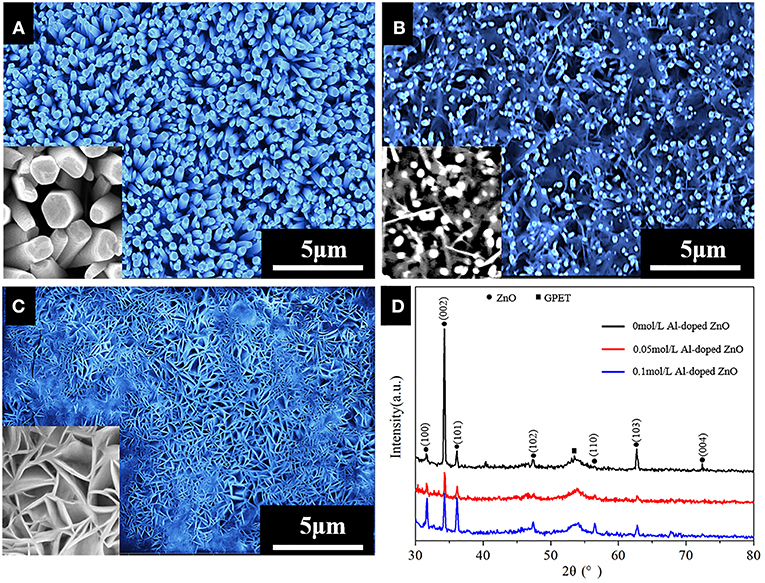

The SEM and XRD images of ZnO with different Al doped concentration (doping concentrations of 0, 0.05, and 0.1 mol/L) prepared on GPET substrates are seen in Figure 1. As shown in Figure 1A, in the case of the undoped Al elements, ZnO has a vertically arranged NR structure with hexagon of its top and a uniformly dense cover on the surface of GPET substrate, suggesting that undoped ZnO has a good degree of orientation. With the addition of Al elements, the structure of ZnO is gradually changed from NR to NS, which clearly observed in Figures 1B,C. It is not difficult to see that AZO NSs, with its smooth surface, still grow perpendicularly to the GPET substrate and are connected together to form a network structure. Compared with the ZnO NRs, the conductivity of obtained electrodes of the AZO NSs can be improved due to the fact that the AZO NSs array can develope the branched network. And the pseudo-capacitance of ZnO nanostructure may improve its capacitance value and thus obtain an excellent electrochemical property (Zhang et al., 2015). As can be seen from the XRD image (Figure 1D), except for the characteristic peaks belonging to graphene and GPET substrate appearing at 26° and 54°, the other peaks are the diffraction peaks of ZnO, which are basically in agreement with the standard PDF card (JCPDS 89-1397) of ZnO. Moreover, the (002) diffraction peak strength is higher than (100) and (101), which indicates that AZO grow preferentially perpendicular to the substrate along the c-axis. The doping of Al generates stress during crystallization, and the crystal structure of ZnO changes accordingly. Further, the intensity of the diffraction peaks of (002) may become weak due to the incorporation of Al elements.

Figure 1. (A–C) FE-SEM image of Al-doped ZnO nanostructure grown on GPET substrate at different Al doped concentration: (A) 0 mol/L; (B) 0.05 mol/L; (C) 0.1 mol/L; (D) XRD spectra of all samples. The inset in (A–C) correspond high-magnification images.

Schematic diagram of hydrothermal growth mechanism of ZnO NSs in Figure 2 revealed that incorporation of Al inhibits the growth of ZnO NRs, thereby forming AZO NSs. The ZnO crystal has a (0001) plane and a (0001) plane, that is, a Zn positive polar surface and an O negative polar surface and six non-polar surfaces. Al2O3 dissolved in the solution to produce complexing ions, and the positive polar surface (0001) of the ZnO lattice is more likely to adsorb the Al complexing ions with negative charges, which can hinder the growth of ZnO along the [0001] direction. The growth of NRs was inhibited along c-axis, which promoted the lateral growth of ZnO, and then formed ZnO NSs (Figure 2C; Koh et al., 2004). The main chemical reactions occurring in the solution during the formation of the ZnO NSs were involved in the following Equations (1) and (4):

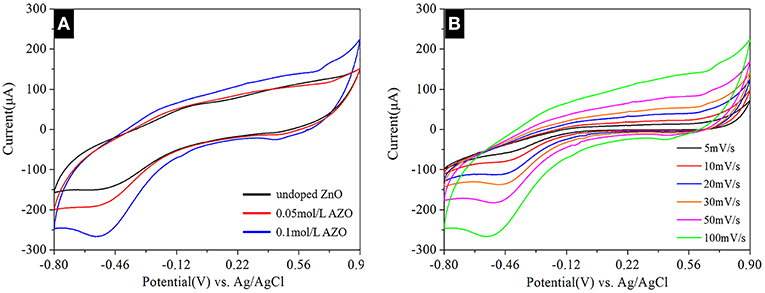

In order to study the effects of different concentrations of Al doping on the electrochemical characteristics of ZnO nanostructures, the CV curves of three different samples were analyzed under a potential range of −0.8 to 0.9 V at scanning rates of 100 mV/s.

The CV curves, which has been clearly observed by Figure 3A, revealed that redox peaks of 0.1 mol/L AZO NSs can be significant observed, which indicated that the synthesized active substances are beneficial for rapid redox reactions (Pu et al., 2014). Comparing the integrated area of the samples on the current-potential axis (Figure 3A), it is well-known that the integrated area of the 0.1 mol/L AZO NSs is larger, indicating that the 0.1 mol/L AZO NSs has a stronger charge storage capacity. Further study on the of different scanning rates of 5, 10, 20, 30, 50, and 100 mV/s on the electrochemical characteristics of 0.1 mol/L AZO NSs nanostructures (Figure 3B), and the results showed that the electrical current density increases with the increases of scan rates, which confirmed that 0.1 mol/L AZO NSs nanomaterials have excellent scanning ability.

Figure 3. (A) CV curves of all samples at a scan rate of 50 mV/s. (B) CV curves of 0.1 mol/L AZO nanostructures grown on GPET substrates with different scan rates in the range of 5–100 mV/s.

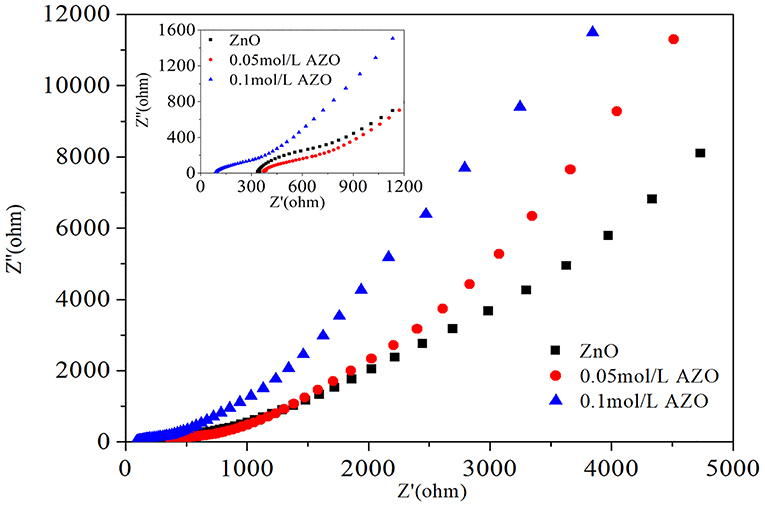

The Nyquist plots of AZO/GPET electrodes are shown in Figure 4. The impedance curves of all obtained samples consisted of high frequency zones (shown as semicircle), which reflects the charge transfer resistance (Rct) of the electrode, and low frequency zones (shown as slash), which mirrors the diffusion resistance of the ions of the electrode. The semicircular diameter of the high-frequency zone is basically the same, indicating that the addition of Al does not enhance the charge transfer ability of ZnO/GPET electrode. In the low frequency zones the diffusion rate of electrode is proportional to the slope of impedance curve. The diffusion rate of AZO/GPET electrode is significantly greater than that of ZnO/GPET electrode, which indicated that AZO/GPET electrode has better electrochemical properties.

Figure 4. Nyquist plots of 0 mol/L ZnO, 0.05 mol/L AZO, and 0.1 mol/L AZO. Inset is the enlarged high frequency zones.

Conclusions

In summary, AZO NSs, which are evenly grown perpendicular to the GPET substrate, were successfully prepared using hydrothermal method assisted by ion sputtering. The structure, microscopic morphology and growth mechanism of the samples were analyzed, and it was concluded that the incorporation of Al3+ inhibited the growth of ZnO NRs, but promoted the formation of ZnO NSs, and weakened the characteristic diffraction peak intensity of ZnO growing perpendicular to the substrate along the c-axis. The electrochemical performance test of the samples concluded that the AZO NSs have better electrochemical performance than the undoped ZnO NRs, which have broad application prospects in the field of capacitors.

Data Availability

All datasets generated for this study are included in the manuscript/supplementary files.

Author Contributions

QY contributed to the research and result analysis and discussion. SR, PR, YL, and LJ assisted in the synthesis and analysis of the materials. All authors contributed to the general discussion.

Funding

This work was financially supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant no. 51502166), Scientific Research Program Funded by Shaanxi Provincial Department (Grant no. 17JK0130), and the Industrial Field of Key Research and Development Plan of Shaanxi Province (Grant no. 2018GY-040).

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

Abbey, C., and Joos, G. (2007). Supercapacitor energy storage for wind energy applications. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 43, 769–776. doi: 10.1109/TIA.2007.895768

Bhirud, A., Sathaye, S., Waichal, R., Park, C. J, and Kale, B. (2015). In situ preparation of N– ZnO/graphene nanocomposites: excellent candidate as a photocatalyst for enhanced solar hydrogen generation and high performance supercapacitor electrode. J. Mater. Chem. A 3, 17050–17063. doi: 10.1039/C5TA03955J

Biplab, K. D., Ankita, H., and Jisoo, K. (2017). Recent development and challenges of multifunctional structural supercapacitors for automotive industries. Int. J. Energ. Res. 41, 1397–1411. doi: 10.1002/er.3707

Bu, I. Y. Y., and Huang, R. (2015). One-pot synthesis of ZnO/reduced graphene oxide nanocomposite for supercapacitor applications. Mat. Sci. Semicon. Proc. 31, 131–138. doi: 10.1016/j.mssp.2014.11.037

Cao, J., and Emadi, A. (2011). A new battery/ultracapacitor hybrid energy storage system for electric, hybrid, and plug-in hybrid electric vehicles. IEEE Trans. Power Electr. 27, 122–132. doi: 10.1109/TPEL.2011.2151206

Faraji, S., and Ani, F. N. (2014). Microwave-assisted synthesis of metal oxide/hydroxide composite electrodes for high power supercapacitors – a review. J. Power Sources 263, 338–360. doi: 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.03.144

Futaba, D. N., Hata, K., Yamada, T., Hiraoka, T., Hayamizu, Y., Kakudate, Y., et al. (2006). Shape-engineerable and highly densely packed single-walled carbon nanotubes and their application as super-capacitor electrodes. Nat. Mater. 5, 987–994. doi: 10.1038/nmat1782

Han, W. J., Ren, L., Gong, L. J., Qi, X., Liu, Y. D., Yang, L. W., et al. (2014). Self-assembled three- dimensional graphene-based aerogel with embedded multifarious functional nanoparticles and its excellent photoelectrochemical activities. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2, 741–748. doi: 10.1021/sc400417u

Isabel, P. P., David, S. T., Ramiro, R. R., Emilia, M., and Diego, C. A. (2016). Design of activated carbon/activated carbon asymmetric capacitors. Front. Mater. 3:16. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2016.00016

Jacob, L., Prasanna, K., Vengatesan, M. R., Santhoshkumar, P., Lee, C. W., and Mittal, V. (2018). Binary Cu/ZnO decorated graphene nanocomposites as an efficient anode for lithium ion batteries. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 59, 108–114. doi: 10.1016/j.jiec.2017.10.012

Klingshirn, C. (2010). The luminescence of ZnO under high one- and two-quantum excitation. Scripta Mater. 71, 547–556. doi: 10.1002/pssb.2220710216

Koh, Y. W., Ming, L., Tan, C. K., Yong, L. F., and Loh, K. P. (2004). Self-assembly and selected area growth of zinc oxide nanorods on any surface promoted by an aluminum precoat. J. Phys. Chem. B 108, 11419–11425. doi: 10.1021/jp049134f

Liu, W. J., Kao, T. W., Dai, Y. M., and Jehng, J. (2014). M. Ni-based nanocomposites supported on graphene nano sheet (GNS) for supercapacitor applications. J. Solid State Electrochem. 18, 18189–18196. doi: 10.1007/s10008-013-2263-4

Liu, X., Sheng, G., Zhong, M., and Zhou, X. (2018). Hybrid nanowires and nanoparticles of WO3 in a carbon aerogel for supercapacitor applications. Nanoscale 10, 4209–4217. doi: 10.1039/C7NR07191D

Narayanan, R., Kumar, P. N., Deepa, M., and Srivastava, A. K. (2015). Combining energy conversion and storage: a solar powered supercapacitor. Electrochim. Acta 178, 113–126. doi: 10.1016/j.electacta.2015.07.121

Pu, J., Wang, Z., Wu, K., Yu, N., and Sheng, E. (2014). Co9S8 nanotubes arrays supported on nickel foam for high-performance supercapacitors. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 16, 16785–16791. doi: 10.1039/C3CP54192D

Ren, J., Li, L., Chen, C., Chen, X., Cai, Z., Qiu, L., et al. (2013). Twisting carbon nanotube fibers for both wire-shaped micro-supercapacitor and micro-battery. Adv. Mater. 25, 1155–1159. doi: 10.1002/adma.201203445

Ren, S., Rong, P., and Yu, Q. (2018). Preparations, properties and applications of graphene in functional devices: a concise review. Ceram. Int. 44, 11940–11955. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2018.04.089

Salinas-Torres, D., Ruiz-Rosas, R., Morallón, E., and Cazorla-Amorós, D. (2019). Strategies to enhance the performance of electrochemical capacitors based on carbon materials. Front. Mater. 6:115. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2019.00115

Wang, G., Wang, H., Lu, X., Ling, Y., Yu, M., Zhai, T., et al. (2014). Solid-state supercapacitor based on activated carbon cloths exhibits excellent rate capability. Adv. Mater. 26, 2676–2682. doi: 10.1002/adma.201304756

Wang, J., Zan, G., Li, Z. S., Wang, B., Yan, Y. X., Liu, Q., et al. (2011). Green synthesis of graphene nanosheets/ZnO composites and electrochemical properties. J. Solid State Chem. 184, 1421–1427. doi: 10.1016/j.jssc.2011.03.006

Wu, C., Chen, L., Lou, X., Ding, M., and Jia, C. (2018). Fabrication of cobalt-nickel-zinc ternary oxide nanosheet and applications for supercapacitor electrode. Front. Chem. 6:597. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2018.00597

Xu, X., Li, S., Zhang, H., Shen, Y., Zakeeruddin, S. M., Graetzel, M., et al. (2015). A power pack based on organometallic perovskite solar cell and supercapacitor. ACS Nano 9, 1782–1787. doi: 10.1021/nn506651m

Yang, H., Ye, S., Zhou, J., and Liang, T. (2019). Biomass-derived porous carbon materials for supercapacitor. Front Chem. 7:274. doi: 10.3389/fchem.2019.00274

Zhang, Y., Zou, Q., Hsu, H. S., Raina, S., Xu, Y., and Kang, J. B. (2016). Morphology effect of vertical graphene on the high performance of supercapacitor electrode. ACS Appl. Mater. Inter. 8, 7363–7369. doi: 10.1021/acsami.5b12652

Zhang, Z., Ren, L., Han, W. J., Meng, L., Wei, X., and Qi, X. (2015). One-pot electrodeposition synthesis of ZnO/graphene composite and its use as binder-free electrode for supercapacitor. Ceram. Int. 41, 4374–4380. doi: 10.1016/j.ceramint.2014.11.127

Keywords: ZnO, Al-doped, hydrothermal method, graphene-based flexible substrates, electrochemical performance

Citation: Yu Q, Rong P, Ren S, Jiang L and Li Y (2019) Fabrication and Electrochemical Performance of Al-Doped ZnO Nanosheets on Graphene-Based Flexible Substrates. Front. Mater. 6:208. doi: 10.3389/fmats.2019.00208

Received: 22 June 2019; Accepted: 12 August 2019;

Published: 04 September 2019.

Edited by:

Wenyao Li, Shanghai University of Engineering Sciences, ChinaCopyright © 2019 Yu, Rong, Ren, Jiang and Li. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Qi Yu, a3VrdWtva28yMDA0QDE2My5jb20=

Qi Yu

Qi Yu Ping Rong

Ping Rong Shuai Ren

Shuai Ren Liyun Jiang

Liyun Jiang Yapeng Li

Yapeng Li