Abstract

Marine plastic governance has become one of the most pressing challenges facing the marine environment. The existing international legal framework is inadequate to address this issue, characterized by a lack of systemic comprehensiveness and targeted measures. Furthermore, imperfect implementation and monitoring mechanisms make it difficult to ensure effective compliance by states. Although the “Legally Binding International Instrument on Plastic Pollution (including Marine Plastic Pollution)” (hereinafter referred to as the Global Plastics Treaty) proposes a series of ambitious governance measures, its negotiations reached a deadlock after the Geneva session in August 2025. This stalemate underscores the conflicting interests and divergent views among nations and stakeholder groups regarding global plastic governance. This paper analyzes perspectives on marine plastic governance drawn from existing treaties and literature, proposes principled constraints together with feasible technical solutions and pathways, and offers potential options for the next phase of the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations. The analysis demonstrates that effective marine plastic governance depends on pragmatic political commitment and the active cooperation of all nations. The Global Plastics Treaty should adopt a progressive, standards-driven framework that implements the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) through political commitments to appropriate standards, supported by technical and financial assistance. The non-regression principle should be implemented through mandatory national reporting and unified monitoring. Building upon these two principles, marine plastic governance can be strengthened through the development, adoption, and implementation of progressive standards.

1 Introduction

Plastic pollution represents a critical global challenge to marine ecosystems, posing significant threats not only to marine biodiversity and ecosystem functions but also to human health and socio-economic development (Yu et al., 2023). Marine plastic debris is broadly categorized by source into land-based and sea-based waste, encompassing domestic litter, industrial and agricultural waste, detached ship coatings, and abandoned fishing gear, including nets and other fishing equipment. Since 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic has triggered the widespread use of single-use plastic products, resulting in a substantial surge in plastic waste generation and establishing these disposable items as the predominant contributors to global plastic contamination (Dauvergne, 2023). When exposed to environmental forces such as solar radiation, wind, and ocean currents, plastic waste fragments into microplastic and nanoplastic particles, thereby exacerbating its detrimental impact on the marine environment (IUCN, 2024). According to projections by the United Nations Environment Programme, without immediate intervention, the annual discharge of plastic waste into aquatic ecosystems could nearly triple by 2040, potentially imposing an annual financial burden of approximately $100 billion on businesses responsible for managing the anticipated waste volumes (UNEP, 2023b).

At the international level, three categories of conventions—addressing marine pollution, biodiversity, and chemicals and waste management—currently constitute the principal normative frameworks relevant to marine plastic governance (UNEP, 2018). These include the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships and its 1978 Protocol (MARPOL 73/78), the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), the Convention on the Prevention of Marine Pollution by Dumping of Wastes and Other Matter (London Convention), the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the Basel Convention on the Control of Transboundary Movements of Hazardous Wastes and Their Disposal (Basel Convention), and the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants (Stockholm Convention). However, the existing legal framework is characterized by fragmentation, limited regulatory scope, vague delineation of responsibilities, and insufficient monitoring and enforcement mechanisms (Raubenheimer et al., 2018). Regional and national legislation concerning marine plastic pollution prevention has gradually matured across various regions and countries, supported by increasingly robust practical experience. In recent years, the European Union, China, India, Australia, the United States, and other countries have enacted laws and policies to prohibit or restrict plastic use and address marine pollution. Nevertheless, measures in certain regions remain insufficiently stringent and lack cohesive coordination and effective governance mechanisms.

The United Nations has shown increasing focus on marine plastic governance. The resolution “End Plastic Pollution: Towards an International Legally Binding Instrument”, adopted at the fifth session of the UN Environment Assembly in March 2022, set a new direction for global cooperation on this issue. Between 2022 and 2025, the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) devoted efforts to negotiating a global plastics treaty. However, both segments of its fifth session, held in December 2024 and August 2025, concluded without producing a final text due to significant divergences, leaving the negotiations at an impasse. This stalemate primarily stems from differing visions among nations and stakeholders regarding the desired level of ambition and process for global plastic governance, reflecting underlying divergences of interest among negotiating blocs and developmental disparities across regions. A pressing challenge requiring concrete responses is how to advance the global plastics treaty negotiations within the framework of international law and leverage the treaty’s potential to establish a comprehensive, effective, and coordinated governance mechanism for marine plastics.

2 Methodology

In line with the research theme, this study employs three methodological approaches: literature review, comparative analysis, and the standardization approach. The literature review systematically examines existing international legal instruments, including current international conventions and the ongoing negotiating texts of the Global Plastics Treaty (such as the compilation text, the Chair’s text, and party submissions), to identify pathways for marine plastic governance, governance gaps, and negotiation divergences. Concurrently, it synthesizes academic research on the scientific, economic, and political dimensions of marine plastic governance to establish a theoretical foundation. The comparative analysis draws governance insights by contrasting the draft Global Plastics Treaty with successful environmental agreements, such as the Paris Agreement, in terms of institutional design and implementation mechanisms. It also compares the positions of major negotiating blocs, such as the “High Ambition Coalition” and the “Like-Minded Group”, to uncover the root causes of the negotiation deadlock. These two methods are mutually reinforcing: the literature review provides foundational evidence, while the comparative analysis offers structured insights based on it, thereby proposing actionable governance pathways to address institutional challenges in global plastic governance. This study proposes the standardization approach as a means to resolve the deadlock in global plastics treaty negotiations. By conceptualizing the norms for technical practice as well as legal obligations established by a global plastics treaty as standards, this study explores their rationality, consistency, and flexibility, thereby deriving corresponding standards and application schemes for marine plastic governance. Existing research indicates that the standardization approach helps clarify obligations, making them both enforceable and comparable. Furthermore, standardization serves as an integral component of governance mechanisms, contributing to clearer institutional structures and lower compliance costs (ECOS, 2021; Steffek and Wegmann, 2021). The “standardization approach” adopted in this study differs conceptually from both harmonization and compliance frameworks traditionally used in international environmental law. Whereas harmonization seeks the convergence of national as well as international laws through uniform treaty provisions, and compliance focuses on the enforcement of pre-defined obligations, standardization refers to the iterative development of evolving norms and technical benchmarks that gradually shape state behavior. In the context of the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations, this approach captures the dynamic interplay between legal norms and technical practices—such as ISO standards on recyclability or design-for-reuse—that progressively acquire normative force through repeated adoption and reporting. Standard-setting could function as a bridge between soft and hard law, creating a flexible architecture suitable for issues characterized by scientific uncertainty and technological diversity (Abbott, 2000). Hence, standardization is an appropriate analytical method for evaluating a treaty still in negotiation, where binding obligations remain emergent rather than fixed.

3 Challenges in marine plastic governance: limitations of the existing legal framework and the negotiation deadlock of the global plastics treaty

The study begins by examining the current limitations of marine plastic governance—covering both the inadequacies of the existing legal framework and the ongoing deadlock in global plastics treaty negotiations. Although manifested differently, these challenges collectively reflect the core difficulties of marine plastic governance: the inherent complexity of the regulatory subject and the resulting divergences in interests and technical hurdles that such complexity entails.

3.1 Limitations of the existing legal framework for marine plastic governance

3.1.1 Absence of a specialized legal framework for marine plastic governance

The governance of marine plastic pollution has long suffered from a notable absence of targeted legal instruments. Existing legal norms pertaining to marine plastic governance are fragmented across various international conventions, with different texts often containing overlapping, duplicate, or even contradictory provisions (Raubenheimer et al., 2018; Wang, 2023). The UNCLOS, the London Convention, the Basel Convention, and the Stockholm Convention all encompass general obligations relating to the protecting of the ecological environment, the control of pollution, and the prohibit of the dumping or transferring pollutants. However, owing to the distinct primary functions of each convention, they have failed to form an integrated framework. For example, the Landon Convention and the Basel Convention use different approaches regarding the transfer of wastes over boundaries. The London Convention prohibits parties from exporting waste to other countries for dumping or incineration, allowing waste management and partial transfers only under appropriate regional cooperation frameworks1. In contrast, the Basel Convention takes a slightly different approach, allowing the transfer of waste to parties with the capacity for environmentally sound treatment, provided that prior notification and written consent are obtained2.

Moreover, Existing international instruments on plastic and chemical management—most notably the Basel Convention and the Stockholm Convention—address certain aspects of marine plastic pollution but remain fragmented in scope and implementation. The Basel regime focuses on transboundary waste control, while the Stockholm regime targets specific Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs). Yet neither provides an integrated, comprehensive framework for the entire life cycle of different kinds of plastics (UNEP, 2019; Wang, 2023). As summarized in Table 1, the two conventions differ in objectives, mechanisms, and coverage, leaving major regulatory gaps, including the lack of standards for additives, limited attention to microplastics, and weak coordination across treaty regimes. These gaps highlight the need for a coherent legal foundation under the emerging Global Plastics Treaty.

Table 1

| Comparison between the Basel convention and the Stockholm convention and regulatory gaps regarding modern plastic governance | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Dimension | Basel convention | Stockholm convention | Regulatory gaps |

| Primary Objective | Controls transboundary movement and disposal of hazardous wastes | Eliminates or restricts Persistent Organic Pollutants (POPs) | No comprehensive life-cycle framework for plastics |

| Scope of Application | Includes hazardous plastic waste (2019, 2022 amendments) | Covers POPs and some plastic additives (e.g., PBDEs) | Most polymers and additives unregulated |

| Regulatory Mechanism | Prior informed consent (PIC); requires ESM | Prohibits or restricts chemicals in Annexes A-C | No control for biodegradable, nano- and microplastics |

| Implementation & Monitoring | National authorities; uneven implementation | Overseen by COP; limited technical support | No global tracking or cross-treaty monitoring system |

| Annexes/Provisions | Annexes VIII-IX define hazardous plastic waste | Annexes A-C list restricted/banned POPs | No harmonized criteria for complex additives |

| Inter-Treaty Coordination | Overlaps with the London Convention | Partial overlap in POPs waste management | Fragmented governance and overlapping mandates |

| Emerging Pollutants Response | COP-15 (2022) adopted new plastic waste guidelines | COP-11 (2023) added new POPs linked to plastics | No binding measures for microplastics or fishing gear |

Regulation gaps in existing conventions and potential improvements of global plastics treaty.

Author’s compilation based on UNEP (2022), Global Chemicals Outlook II; Raubenheimer & Urho (2020); Basel COP-15 Decision BC-15/13; Stockholm COP-11 Decision SC-11/14.

3.1.2 Absence of enforceable rules and coordinated governance mechanisms

Current international norms lack effective enforcement mechanisms. Many international conventions fall within the domain of soft law, lacking binding force and relying solely on political commitments (Vince and Hardesty, 2017). Even those conventions considered hard law frequently lack concrete implementation standards. For instance, the UNCLOS requires states to “endeavor” to use the “best practicable means” “in accordance with their capabilities” to reduce marine pollution, and to “use the most effective practicable approach according to their capabilities while endeavoring to harmonize their policies”.3 The fulfillment of these obligations largely depends on the voluntary actions of contracting states (Wang, 2023). In terms of implementation and accountability, contracting states have also failed to clearly and effectively transpose these conventions into domestic law or fully fulfill their obligations. Following the adoption of the International Convention for the Prevention of Pollution from Ships (MARPOL), several European Union countries were slow to incorporate it into national legislation or failed to clearly define their implementation commitments (Chen, 2015). After the Basel Convention entered into force, illegal waste trafficking persisted on a large scale because many contracting states failed to submit reports as required (Guggisberg, 2024). The lack of enforcement is also evident in the deficiencies of existing international conventions concerning dispute resolution. Although the UNCLOS, the London Convention, the Basel Convention, and the Stockholm Convention all include dispute settlement mechanisms—allowing parties to opt voluntarily for arbitration or bring cases before the International Court of Justice in transboundary environmental pollution disputes—their practical effectiveness remains limited. Many contracting parties have lodged reservations against these clauses, refusing or delaying acceptance of the jurisdiction of international judicial bodies. Furthermore, even when disputes are resolved, the enforcement of rulings often relies on the cooperative will of the involved parties and therefore lacks mandatory authority and deterrent effect (Tessnow-von Wysocki and Le Billon, 2019; Mendenhall, 2023).

From a technical perspective, the absence of standardized methodologies and protocols for monitoring marine plastics poses significant challenges to global cooperative governance (Stoett et al., 2024). Effective marine monitoring can track the sources, distribution, and mobility of marine plastic debris, providing crucial data for assessing and improving global marine plastic governance policies (Tessnow-von Wysocki and Le Billon, 2019). However, there is currently a global lack of unified methods for sampling, analysis, and monitoring that can be applied to different plastic pollutants and across diverse marine environments. This deficiency results in monitoring data collected from different countries and various marine settings being incompatible with global comparative analysis. Consequently, it hinders comprehensive assessment of national-level plastic production, consumption, and waste management practices, ultimately impairing the implementation and evaluation of international marine environmental protection norms (Xu, 2024).

3.2 The negotiation deadlock of the global plastics treaty and its causes

The Global Plastics Treaty aims to regulate the production, consumption, disposal, and recycling of plastics at the global level. Compared with existing international law, its draft represents significant progress in the legal framework, scope of regulation, policy instruments, implementation mechanisms, and international cooperation, marking a major milestone in global marine plastic governance. However, due to varying national conditions, interests, and perceptions regarding plastic governance among different countries, a final agreement has not yet been reached. Substantial disagreements remain, particularly concerning policy support and compensation mechanisms for developing countries, the standards and stringency of convention obligations, and the allocation of responsibilities and implementation measures. This situation led to a deadlock during the fifth session of the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations (Busan, Geneva), effectively stalling the process. Synthesizing the perspectives of participating nations reveals that the causes of the impasse can be attributed to divergences in vision and interests, as well as disagreements arising from new governance technologies.

3.2.1 Absence of a coordinated vision and divergences of interests

During the fifth round of negotiations for the Global Plastics Treaty, participating nations failed to reach a consensus on a shared vision, highlighting significant divergences in interests among countries and stakeholder groups. The draft treaty employs predominantly aspirational language in numerous provisions. While previous research indicates that such non-binding phrasing can provide states with flexibility in implementation and interpretation, it inherently undermines the enforceability and effectiveness of the convention. This approach has directly provoked dissatisfaction among high-ambition countries and contributed to the deadlock in the Geneva talks (European Union, 2023; World Economic Forum, 2025). To date, members of the High Ambition Coalition—including the European Union and Japan—are advocating for a comprehensive lifecycle management approach to plastics governance, including production caps. Conversely, major petrochemical-producing nations such as Saudi Arabia, Iran, and the United States, which hold substantial economic interests in the plastics industry, have resisted including production reduction targets in the negotiations. Instead, they emphasize end-of-pipe solutions such as recycling and waste management (Khan, 2025). Furthermore, although high-ambition countries have expressed willingness to provide technological assistance to developing nations, they maintain reservations regarding Article 12 No. 7 bis, which restricts the use of trade measures in treaty-related disputes and prevents the establishment of green trade barriers (UNEP, 2025). Given these persistent disagreements, what may be termed the “ghosts” of past environmental agreements—soft-law provisions, weak enforceability, and fragmented governance—have reemerged. With countries firmly entrenched in their respective positions, the negotiations have reached a stalemate.

Divergences of interest are not confined to those between nations. During the Geneva negotiations, lobbying groups were exceptionally active. These groups represent diverse interest claims within individual countries, while shared demands among different constituencies can also transcend national boundaries (Williment, 2025; World Economic Forum, 2025). The Union of Scientists has declared that the Global Plastics Treaty must incorporate full lifecycle management (ENB, 2025). Waste picker communities, whose livelihoods depend on the plastic recycling industry, could face significant challenges if comprehensive biodegradable material substitution and plastic lifecycle management are fully implemented. As nations on the front lines of marine plastic pollution, small island and fishing states endure environmental and economic damage that far exceeds their own contribution to the problem. With plastic waste threatening the two key economic pillars—fisheries and tourism—and the issue being beyond the capacity of small islands states to solve unilaterally, they have the strongest impetus to advocate for binding global action. However, fishing nations may also confront restrictions related to the use of fishing gear and nets. Furthermore, a delicate competitive relationship exists between the petrochemical and green materials industries. The former is unlikely to support timelines for phasing out plastic products, while the latter may actively promote agendas to ban plastic products but tend to hold reservations about transferring green technologies to developing countries, often citing considerations such as patent protection.

3.2.2 Divergences arising from new regulatory techniques

The draft Global Plastics Treaty adopts a full life-cycle approach to plastic management and enumerates, in its annexes, effective measures that can be implemented at each stage of the plastic life cycle. Life-Cycle Assessment (LCA) is a methodology for evaluating the environmental impacts of a product throughout its entire life cycle, including raw material extraction, production, transportation, consumption, and disposal. Comprehensive life-cycle management of plastics considers the complete stages of plastic products—from raw material extraction and processing to product manufacturing, distribution, use, and end-of-life management—as well as all potential impacts on ecosystems, society, and the economy. This approach facilitates the analysis and selection of optimal environmental solutions that yield the most favorable socio-economic outcomes (Life Cycle Initiative, 2021; Khan et al., 2024). During the negotiations, the European Union proposed that the entire convention should be grounded in a waste-hierarchy framework, where waste prevention and reuse constitute the preferred options, followed by waste treatment, and advocated for the establishment of corresponding waste management systems (UNEP, 2023a). However, many developing countries currently lack the comprehensive infrastructure and managerial capacity for waste recycling and recovery. Additionally, regarding the development of alternative materials promoted for the production phase, EU countries have expressed skepticism, warning that substitutes may not guarantee safety and could result in unforeseen adverse consequences (UNEP, 2023a). Given these considerations, the full life-cycle management measures have been the subject of ongoing debate throughout the negotiations. During the Geneva talks, delegates debated whether Article 1 of the Chair’s text should include the phrase “[based on a comprehensive approach that addresses the full life cycle of plastics]” (ENB, 2025).

Beyond the disputes concerning life-cycle management, divergent perspectives among nations on whether to establish a mandatory phase-out list for plastic products emerged during the discussions on Article 3 of the Chair’s text concerning plastic production (ENB, 2025). This divergence is reflected in the concessions evident in the revised Chair’s text, where the product phase-out list included in the discussion draft was subsequently removed (INC, 2024, 2025).

To summarize the divergencies in the negotiation of the Global Plastics Treaty, especially those leading to a deadlock in INC-2, we provide Table 2 to this end.

Table 2

| Comparison between negotiating group’s positions in the global plastics treaty (as of INC-5.2) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Group/country | Production caps/ reduction | Chemical restrictions | Recycling & waste management | Finance & tech support | Legal nature/binding obligations |

| High Ambition Coalition (HAC) | Strongly supports global production limits and sustainable consumption | Endorses bans on high-risk plastics and toxic additives | Promotes circular economy; recycling alone seen as insufficient | Advocates robust funding and tech transfer for developing nations and SIDS | Demands legally binding treaty covering full life cycle |

| Like-Minded Countries (Petrochemical producers, OPEC members) | Oppose caps; prefer national waste-management approaches | Reject broad bans; emphasize national discretion | Focus on domestic waste management systems | Request unconditional funding; reject performance-based finance | Favor voluntary, flexible national commitments |

| Emerging Economies (e.g., China, Brazil, Indonesia) | Accept phased or sector-based limits | Support targeted restrictions with local feasibility | Strengthen domestic recycling and reuse systems | Seek fair access to finance and technology | Prefer differentiated obligations reflecting capacity |

| Small Island Developing States (SIDS) | Strongly support strict production limits due to vulnerability | Support bans on toxic and persistent plastics | Focus on marine litter and fishing gear cleanup | Require dedicated funding and capacity-building | Support binding treaty aligned with CBDR |

Divergencies in the negotiation of global plastics treaty.

4 A progressive, standards-driven approach for the global plastics treaty

Notwithstanding various controversies surrounding marine plastic governance, the essence of most disputes fundamentally pertains to issues of governance standards. Standards refer to evolving norms of conduct—typically advancing alongside socio-economic development—that are either widely accepted within specific communities or established by competent authorities, and are expected to achieve universal adherence. These norms impose certain requirements on production and lifestyle patterns. In some instances, standards may assume non-binding forms, serving aspirational or certification purposes instead. The most common types include national standards, industry standards, regional standards, and corporate standards. The governance of marine plastics constitutes a standards issue precisely because international treaties establish binding norms governing activities related to plastic production, utilization, recycling, and management for contracting states. Through implementation measures such as domestic legal incorporation, these norms further extend their binding force to individuals and organizations within member states. From a long-term perspective, such normative frameworks will inevitably reshape production and consumption patterns across nations, thereby fulfilling the guiding function characteristic of standards. The primary controversies in the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations essentially revolve around plastic governance standards. The subsequent analysis will adopt a standards perspective, integrate the principles of common but differentiated responsibilities and non-regression, establish a standardized pathway for marine plastic governance, and propose viable future options for the Global Plastics Treaty.

4.1 Developing appropriate standards in accordance with the principle of common but differentiated responsibilities

The formulation and implementation of standards primarily involve two dimensions: on the positive side, the beneficial transformations they generate—such as product quality standards that protect consumer interests—and on the negative side, issues of capacity and fairness, where excessively high standards may exclude small and medium-sized enterprises lacking technical capability from the market (Fernandes et al., 2019; Curzi et al., 2025). The same applies to marine plastic governance, where disparities in national governance capacities can hinder the harmonization of feasible and equitable standards. Developed countries typically possess advanced environmental technologies and ample financial resources, prioritize marine protection within their policy frameworks, and are therefore better positioned to design and enforce plastic bans and recycling systems. In contrast, many developing regions—particularly in Southeast Asia and Africa, where plastic pollution is most acute—suffer from limited innovation capacity, insufficient funding, and underdeveloped infrastructure, making compliance with green production and advanced recycling requirements difficult (Cowan and Tiller, 2021). When developing a unified global agreement, it is therefore crucial to identify standards tailored to the distinct socio-economic and institutional contexts of different regions. Moreover, because plastic production serves as a pillar industry in many economies—particularly for low-value single-use plastics and packaging materials—overly restrictive production controls could result in market exclusion for these enterprises (Dauvergne, 2018). These dynamics have prompted concerns that the Global Plastics Treaty might evolve into a form of trade barrier (ENB, 2025). Large-scale recycling efforts could also disrupt the livelihoods of waste picker communities (ENB, 2025). Determining how to develop appropriate standards while balancing these competing interests represents a central challenge in the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations.

4.2 The adoption of standards and national reporting obligations

The text of the Global Plastics Treaty grants developing countries flexibility to pursue progressive governance trajectories, enabling them to establish targets, timelines, and standards aligned with their economic, social, and environmental realities. However, EU member states contend that nationally determined commitments alone cannot adequately serve as binding treaty objectives (UNEP, 2023a). Scholars similarly argue that the UNCLOS confers excessive flexibility on developing nations, thereby diluting expectations for effective governance and constraining its capacity to deliver substantive outcomes on marine plastic pollution (Guggisberg, 2024). In response, some scholars advocate limiting the application of the common but differentiated responsibilities (CBDR) principle to financial assistance, while implementing environmental measures uniformly across parties (Tangri, 2023).

This discourse, however, overlooks the intermediate space between rigidly binding obligations and entirely voluntary pledges. Given the profound asymmetries in technological capability, financing, and institutional strength among nations, the draft Global Plastics Treaty could adopt a tiered commitment model. Under such a model, each party would “adopt” governance standards commensurate with its development stage and capacity. Similar approaches have gained traction in international climate regimes, where differentiated and voluntary commitments have been shown to facilitate cooperative participation (Weiss, 2014; Farias and Roger, n.d.). Furthermore, Orlando observes that many international organizations establish broad-based standards that states and non-state actors may voluntarily adopt, thereby enhancing national autonomy while promoting globally coordinated governance (Orlando, 2020).

Within the global plastics governance framework, this study proposes a flexible three-tiered standard commitment structure that enables countries to “adopt” governance targets appropriate to their respective capacities and developmental contexts. This approach not only accommodates national diversity but also ensures the convention’s universality and equity through incentive mechanisms. At the foundational tier, Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and resource-constrained nations would commit to implementing basic plastic governance measures, such as prohibitions on certain high-risk plastic products outlined in Article 3 of the Chair’s text. Achievement of these targets would be facilitated through financial and technical support. The intermediate tier would apply to middle-income countries, requiring them to enhance recycling rates, reduce pollution, and promote the adoption of alternatives. These nations would retain autonomy in selecting specific targets while receiving corresponding international support. The advanced tier would oblige developed countries to assume higher-standard governance responsibilities, including establishing stringent production limits and advancing global technological innovation, while providing technical and financial assistance to developing nations. Research has confirmed the viability of this “adoption mechanism” by demonstrating differing implementation capacities for Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) across various countries (Zhou and Luo, 2024). Further studies suggest that flexible, tiered governance can effectively incentivize nations to assume responsibilities in line with their capabilities and willingness, while ensuring the steady advancement of global cooperation (Luo et al., 2025).

To encourage states to proactively fulfill treaty obligations and adopt higher standards with greater ambition, a targeted incentive mechanism must be established. This can be achieved by linking financial and technical support to the implementation of standards: the level of ambition reflected in a country’s adopted targets, together with its progress toward achieving them, should determine both its eligibility for and the extent of such support. To ensure effective implementation, states should submit regular compliance reports, which should be verified by expert teams to confirm that national commitments and progress align with international standards. Linking support to ambition and performance implies that funding pools and technical assistance programs under the Global Plastics Treaty should not operate solely on a needs-based principle but should instead align with states’ responsibilities—shifting from a “more for developing countries” model to a “more for contributors” philosophy. This does not negate the primary financial and technological responsibilities of developed nations; rather, it underscores the importance of directing a greater share of resources toward ambitious developing countries. This model establishes a competitive, conditional financing channel where developing countries submit ambitious project proposals. Funding and technical support from developed nations are then allocated to the most robust and impactful bids, transforming assistance into a reward for demonstrated performance. (See Figure 1).

Figure 1

Adoption model for tiered standards with conditional finance and technical support according to contribution.

A critical appraisal of this “more for contributors” model necessitates confronting its potential to perpetuate inequity, should it fail to account for the vast disparities in capacity among developing nations. To preemptively address this—and to answer the legitimate concern that it might penalize those Least Developed Countries (LDCs) lacking initial infrastructure—the proposed framework explicitly differentiates between “emerging economies” and “LDCs”. For emerging economies with stronger industrial bases and state capacity, the model channels funds through a performance-based competitive track, incentivizing ambitious climate action. Concurrently, for LDCs, the system mandates a foundational “just transition” mechanism, which allocates a fixed proportion of the core funding (e.g., 30%) exclusively for upfront capacity-building and “seed funding”. This dual structure is further refined by evaluating all recipients, and particularly LDCs, on their “relative progress” against national baselines, rather than on absolute performance alone. By moving beyond the monolithic category of “developing countries”, this tailored approach ensures that the mechanism builds equity in from the start, transforming the most vulnerable from passive aid recipients into active, capable participants in the global climate effort. The mandatory baseline creates a “floor of ambition” without sacrificing flexibility, as the latter is achieved by granting emerging economies the option to undertake greater responsibilities in higher-tier mechanisms.

4.3 Unified monitoring standards and the principle of non-regression

To ensure equity, the oversight of treaty implementation should be entrusted to an expert committee and guided by unified monitoring standards, while the governance standards adopted by nations should be safeguarded against regression. The principles of unified monitoring standards and non-regression have gained recognition both within the negotiating text and throughout the discussions. The draft Global Plastics Treaty demonstrates increased clarity and specificity in its implementation and oversight requirements. The compilation text references “establishing a review mechanism to facilitate Parties’ implementation of the instrument’s provisions”, stating that “each Party shall, through the Secretariat, report to the governing body on its national action plans for implementing the instrument, the progress achieved, and potential challenges encountered.” It further stipulates that “Parties shall, within their capabilities, develop programs to assess and monitor plastic emissions and releases into the environment, including the marine environment”, and emphasizes that the process “shall be transparent, non-punitive, and non-confrontational, expert-based, and shall allow flexibility for developing country Parties, particularly Small Island Developing States, taking their capacities into account” (UNEP, 2024). Through its reinforced monitoring and implementation provisions, the draft Global Plastics Treaty not only enhances accountability among Parties but also establishes a transparent and operational framework for global plastic governance. Provisions concerning monitoring marine plastic pollution and national reporting obligations have also received endorsement within discussion groups at the Geneva session (ENB, 2025).

The non-regression principle, which is widely recognized in the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations and suggested by this study, differs from the ratcheting mechanism of the Paris Agreement, which seeks continuous ambition enhancement. The non-regression principle, rooted in environmental law, prohibits states from weakening existing environmental protections once adopted, thereby serving as a safeguard against policy backsliding. By contrast, the ratcheting mechanism under the Paris Agreement4 institutionalizes a cyclical process of ambition-raising, in which Parties submit and update Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) every five years to progressively strengthen climate actions. Under our proposed design, the progressive advancement of treaty standards would rely on nationally determined pledges and incentive-based financial and technological support for committed parties, rather than on a formalized mechanism of periodic ambition escalation.

To realize unified monitoring standards and operationalize the non-regression principle, the establishment of an open global information platform would serve as an optimal implementation mechanism. This would not only ensure openness and transparency of information but also enhance international cooperation, providing a scientific basis for policy formulation (Xu, 2024). The platform could become a hub for technological collaboration and innovation, supporting the development and application of new technologies in plastic recycling, biodegradable materials, and marine plastic pollution monitoring, thereby helping countries overcome technical bottlenecks in addressing plastic pollution (Tessnow-von Wysocki and Le Billon, 2019). In the context of marine plastic governance, an ideal information platform should encompass the entire continuum from land to sea, including the generation, movement, accumulation, and ultimate entry pathways of plastic waste into the ocean. It should cover key areas of marine plastic pollution, such as garbage patches, marine litter “dead zones”, and major river estuaries where plastic enters the ocean. Global monitoring stations should be established, utilizing advanced technologies like satellite remote sensing, drones, and underwater robots to obtain real-time and accurate data on marine plastic pollution worldwide (Bilawal Khaskheli et al., 2023; Yu et al., 2023). The compilation text of the Global Plastics Treaty also mentions “encouraging Parties to exchange information on best practices, research, and technologies in a transparent manner” and “establishing a cooperation mechanism under this instrument for communication through an information exchange platform” (UNEP, 2024). Therefore, in future negotiations, participating states could further promote the development of such an information platform and commit to participation by regularly providing monitoring data and progress reports. While promoting information sharing, the platform should also address data security and privacy protection concerns. Countries need to enact relevant laws to ensure the security of sensitive data and personal information, preventing data leaks or misuse (Bilawal Khaskheli et al., 2023).

4.4 A Comprehensive support system integrating funding and technology

Multilateral cooperation should be encouraged within the marine plastic governance framework, including under the Global Plastics Treaty, as it can enhance the effectiveness of legal implementation (Xu et al., 2023). The Chair’s text mentions that financial and technological support should be provided to developing countries, with special assistance programs for Least Developed Countries and Small Island Developing States. Simultaneously, the text proposes establishing dedicated funds. During the Geneva talks, in addition to discussing dedicated funds, it was also proposed to use the Global Environment Facility (GEF) as an interim financial mechanism (ENB, 2025). The aforementioned provisions and proposed mechanisms merit recognition. Beyond setting mandatory standards and general assistance, the Global Plastics Treaty could also establish incentive rules to reward countries that proactively adopt and fulfill standards.

In addition to the direct forms of support recognized in international law—namely financial and technical assistance—attention should also be given to the soft support system built through the participation of all sectors of society. Marine plastic governance spans multiple fields and presents an interdisciplinary challenge, making cross-sectoral collaboration essential for the effective implementation of the law (Riechers et al., 2021). Throughout the negotiation process of the Global Plastics Treaty, stakeholders including academia, indigenous peoples, women, and waste pickers have participated fully (ENB, 2025). The compilation text mentions “promoting the active involvement of stakeholders in the development and implementation of the instrument” and “providing a space for stakeholders to share knowledge and experiences” (UNEP, 2024). Governments can establish bottom-up mechanisms to strengthen coordination among government, industry, and civil society (Ferraro and Failler, 2020; Cowan and Tiller, 2021). They should facilitate public participation, conduct education and training to raise citizens’ awareness of marine environmental protection (Xu et al., 2023), and maintain ties with academia in the formulation and implementation of domestic policies to foster a virtuous cycle of scientific progress and policy improvement (Ferraro and Failler, 2020). Through extended producer responsibility systems, governments can provide policy guidance and regulatory constraints to encourage corporate innovation in reducing plastic use, increasing recycling rates, and developing alternative materials, thereby promoting greater corporate social responsibility. Governments can also use market-based guidance to incentivize businesses and consumers to make more environmentally friendly choices in consumption, production, and recycling (Cowan and Tiller, 2021). For example, products certified with “green labels” or “recyclable” logos can attract greater market demand, thereby encouraging businesses to transition to more sustainable production methods. Governments may also impose environmental taxes on the production and sale of plastic products or provide financial incentives for plastic alternatives and recycling enterprises (Raubenheimer and Urho, 2020). Financial instruments and market mechanisms complement each other; governments can issue green bonds to raise funds for marine plastic pollution control projects. When implementing policies such as large-scale recycling, attention must also be paid to protecting the interests of waste picker communities (Dauvergne, 2023; ENB, 2025).

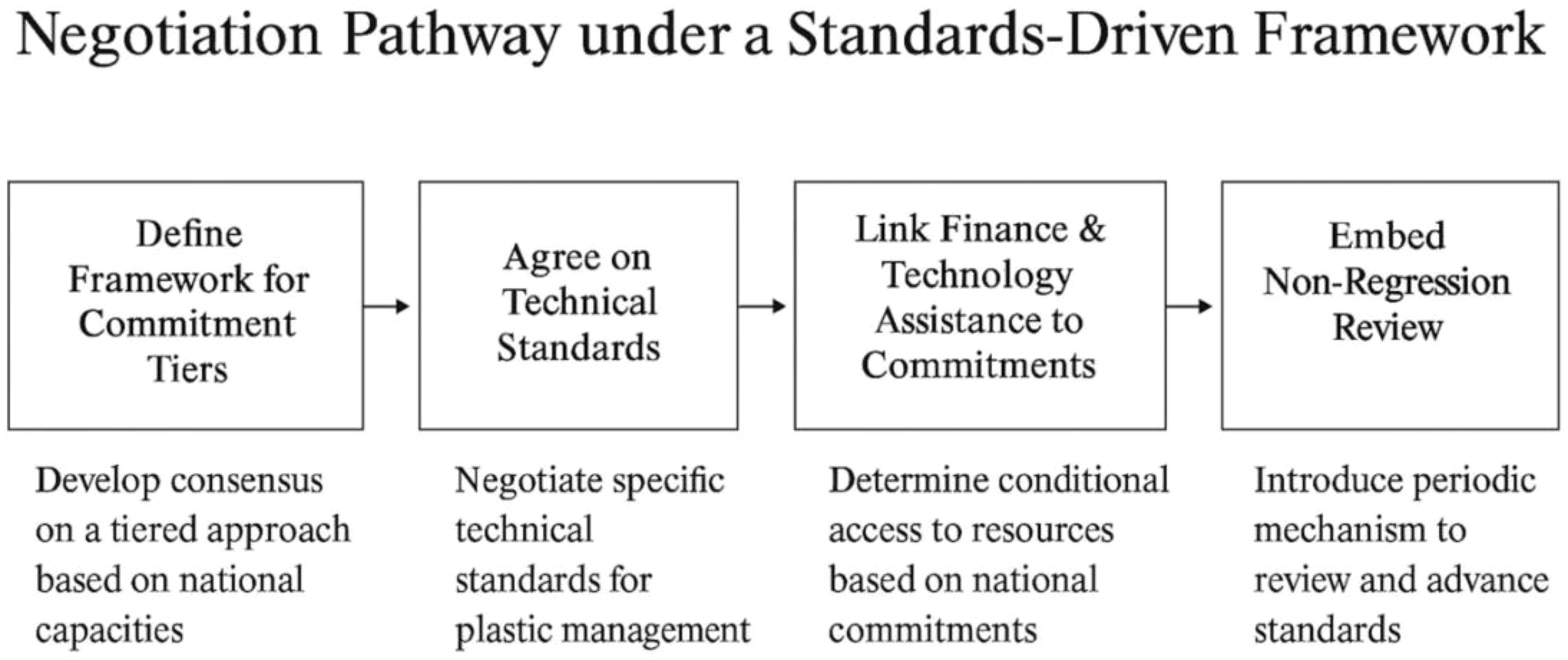

4.5 Negotiation pathway under a standards-driven framework

To operationalize the “standards-driven” approach proposed in this paper, Figure 2 illustrates a negotiation pathway designed to transform political polarization into iterative cooperation. The pathway proceeds through four stages: (1) reframing negotiations around tiered progressive standards; (2) codifying measurable technical benchmarks; (3) aligning financial and technological mechanisms with demonstrated progress; and (4) embedding a periodic non-regression review to sustain upward ambition. This model demonstrates how standardization can convert distributive conflicts into cooperative calibration, offering a politically feasible route for advancing the Global Plastics Treaty negotiation.

Figure 2

Negotiation pathway to break the deadlock in the negotiation of global plastics treaty under the standards-driven framework.

5 Conclusion

The persistent deadlock in the Global Plastics Treaty negotiations reflects deep structural divisions between developed and developing countries, particularly regarding financial responsibilities, production limits, and enforcement flexibility. This study situates its proposal within this broader treaty context, recognizing that any viable solution must bridge political asymmetries while maintaining legal ambition. The proposed “progressive, standards-driven governance framework” addresses these challenges by combining the non-regression principle with a flexible, tiered commitment system. This dual mechanism allows states to adopt governance standards aligned with their capacities, supported by financial and technological incentives. Consequently, the framework balances differentiation with accountability: it offers high-ambition states a pathway for leadership, while enabling developing and small island states to participate meaningfully without disproportionate burdens. Such design makes the framework politically realistic and normatively coherent, offering a credible route for unlocking the negotiation stalemate.

Statements

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

BX: Methodology, Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Writing – original draft.

Funding

The author(s) declared that financial support was received for this work and/or its publication. This study is funded by National Social Science Funds (Project No. 24CFX035) and the Fundamental Research Funds for Central Universities (Project No. 3132025367).

Conflict of interest

The author(s) declared that this work was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Generative AI statement

The author(s) declared that generative AI was not used in the creation of this manuscript.

Any alternative text (alt text) provided alongside figures in this article has been generated by Frontiers with the support of artificial intelligence and reasonable efforts have been made to ensure accuracy, including review by the authors wherever possible. If you identify any issues, please contact us.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

1.^See Art. 6, 12 London Convention.

2.^See Art. 6, 7 Basel Convention.

3.^See Art. 192, 194 UNCLOS.

4.^See Art. 4 & 14 Paris Agreement.

References

1

Abbott K. (2000). Hard and soft law in international governance. Int. Organ.54, 421. doi: 10.1162/002081800551280

2

Bilawal Khaskheli M. Wang S. Zhang X. Shamsi I. H. Shen C. Rasheed S. et al . (2023). Technology advancement and international law in marine policy, challenges, solutions and future prospective. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1258924

3

Chen C.-L. (2015). “ Regulation and management of marine litter,” in Marine Anthropogenic Litter (Cham ZG, Switzerland: Springer), 395–428.

4

Cowan E. Tiller R. (2021). What shall we do with a sea of plastics? A systematic literature review on how to pave the road toward a global comprehensive plastic governance agreement. Front. Mar. Sci.8. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.798534

5

Curzi D. Schuster M. Maertens M. Alessandro O. (2025). Standards, trade margins and product quality: Firm-level evidence from Peru | Request PDF. Food Policy91, 101834. doi: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2020.101834

6

Dauvergne P. (2018). Why is the global governance of plastic failing the oceans? Global Environ. Change51, 22–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2018.05.002

7

Dauvergne P. (2023). The necessity of justice for a fair, legitimate, and effective treaty on plastic pollution. Mar. Policy155, 105785. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105785

8

ECOS (2021). International standardisation that works for the environment. Available online at: https://ecostandard.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/ECOS-PAPER-International-standardisation-that-works-for-the-environment.pdf (Accessed September 8, 2025).

9

ENB (2025). “ Summary report 5–15 August 2025,” in IISD Earth Negotiations Bulletin. Winnipeg: International Institute for Sustainable Development, IISD. Available online at: https://enb.iisd.org/plastic-pollution-marine-environment-negotiating-committee-inc5.2-summary.

10

European Union (2023). Proposed response template on written submissions prior to INC-3 (part a). Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/eums_14092023_a.pdf (Accessed December 20, 2024).

11

Farias D. B. L. Roger C. Differentiation in environmental treaty making: measuring provisions and how they reshape the depth–participation dilemma. Global Environ. Politics (2023) 23, 117–132.

12

Fernandes A. M. Ferro E. Wilson J. S. (2019). Product standards and firms’ Export decisions. World Bank Economic Rev.33, 353–374. doi: 10.1093/wber/lhw071

13

Ferraro G. Failler P. (2020). Governing plastic pollution in the oceans: Institutional challenges and areas for action. Environ. Sci. Policy112, 453–460. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2020.06.015

14

Guggisberg S. (2024). Finding equitable solutions to the land-based sources of marine plastic pollution: Sovereignty as a double-edged sword. Mar. Policy159, 105960. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105960

15

INC (2024). Chair’s Text of Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment. Busan, Korea: Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee

16

INC (2025). Revised Chair’s Text of Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee to develop an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment. Geneva: Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee

17

IUCN (2024). Plastic Pollution. Available online at: https://iucn.org/resources/issues-brief/plastic-pollution (Accessed December 12, 2024).

18

Khan M. T. Rashid S. Yaman U. Khalid S. A. Kamal A. Ahmad M. et al . (2024). Microplastic pollution in aquatic ecosystem: A review of existing policies and regulations. Chemosphere364, 143221. doi: 10.1016/j.chemosphere.2024.143221

19

Khan U. (2025). Plastic promises, fragile progress: The stalemate in global plastics treaty talks. Available online at: https://thebulletin.brandtschool.de/plastic-promises-fragile-progress-the-stalemate-in-global-plastics-treaty-talks (Accessed October 30, 2025).

20

Life Cycle Initiative (2021). Life Cycle Approach to Plastic Pollution - Life Cycle Initiative. Available online at: https://www.lifecycleinitiative.org/activities/life-cycle-assessment-in-high-impact-sectors/life-cycle-approach-to-plastic-pollution/ (Accessed January 28, 2025).

21

Luo B. Cao X. Sun K. (2025). Dilemma in global governance of marine plastic pollution and regulatory coordination: convention reconstruction via integrated international law. Front. Mar. Sci.12. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1687898

22

Mendenhall E. (2023). Making the most of what we already have: Activating UNCLOS to combat marine plastic pollution. Mar. Policy155, 105786. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2023.105786

23

Orlando E. (2020). “ Principles, standards and voluntary commitments in international environmental law,” in Routledge Handbook of International Environmental Law (London: Routledge).

24

Raubenheimer K. McIlgorm A. Oral N. (2018). Towards an improved international framework to govern the life cycle of plastics. Rev. European Comp. Int. Environ. Law27, 210–221. doi: 10.1111/reel.12267

25

Raubenheimer K. Urho N. (2020). Rethinking global governance of plastics – The role of industry. Mar. Policy113, 103802. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103802

26

Riechers M. Fanini L. Apicella A. Galván C. B. Blondel E. Espiña B. et al . (2021). Plastics in our ocean as transdisciplinary challenge. Mar. pollut. Bull.164, 112051. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2021.112051

27

Steffek J. Wegmann P. (2021). The standardization of “Good governance” in the age of reflexive modernity. Global Stud. Q.1, 1–10. doi: 10.1093/isagsq/ksab029

28

Stoett P. Scrich V. M. Elliff C. I. Andrade M. M. de M. Grilli N. Turra A. (2024). Global plastic pollution, sustainable development, and plastic justice. World Dev.184, 106756. doi: 10.1016/j.worlddev.2024.106756

29

Tangri N. (2023). POLICY BRIEF: Common But Differentiated Responsibility in the Global Plastics Treaty. Available online at: https://scholars.org/sites/scholars/files/2023-11/Tangri%202023%20CBDR%20in%20GPT%20(1).pdf (Accessed December 20, 2024).

30

Tessnow-von Wysocki I. Le Billon P. (2019). Plastics at sea: Treaty design for a global solution to marine plastic pollution. Environ. Sci. Policy100, 94–104. doi: 10.1016/j.envsci.2019.06.005

31

UNEP (2018). Combating marine plastic litter and microplastics: an assessment of the effectiveness of relevant international, regional and subregional governance strategies and approaches: Summary for Policymakers. Available online at: https://apps1.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/unep_aheg_2018_inf3_summary_assessment_ch.pdf (Accessed December 20, 2024).

32

UNEP (2019). Global Chemicals Outlook II - From Legacies to Innovative Solutions: Implementing the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Nairobi, Kenya: UNEP

33

UNEP (2023a). EU and its Member States statement delivered in CG1 on 31 May 2023. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/resolutions/uploads/eu_0.pdf (Accessed September 8, 2025).

34

UNEP (2023b). Plastic pollution & marine litter | UNEP - UN Environment Programme. Available online at: https://www.unep.org/topics/ocean-seas-and-coasts/ecosystem-degradation-pollution/plastic-pollution-marine-litter (Accessed September 8, 2025).

35

UNEP (2024). Compilation of draft text of the international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment. Available online at: https://wedocs.unep.org/bitstream/handle/20.500.11822/45858/Compilation_Text.pdf (Accessed December 20, 2024).

36

UNEP (2025). Assembled text of preparation of an international legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment. Available online at: https://resolutions.unep.org/incres/uploads/k2512852e_-_unep-pp-inc-5-crp.1_-_amended_final.pdf (Accessed October 30, 2025).

37

Vince J. Hardesty B. D. (2017). Plastic pollution challenges in marine and coastal environments: from local to global governance. Restor. Ecol.25, 123–128. doi: 10.1111/rec.12388

38

Wang S. (2023). International law-making process of combating plastic pollution: Status Quo, debates and prospects. Mar. Policy147, 105376. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2022.105376

39

Weiss E. B. (2014). Voluntary commitments as emerging instruments in international environmental law. Envtl. Pol’y L.44, 83.

40

Williment C. (2025). Why did The UN’s INC-5.2 Fail to Organise a Plastic Treaty? Available online at: https://sustainabilitymag.com/news/why-did-the-uns-inc-5-2-fail-to-organise-a-plastic-treaty (Accessed October 30, 2025).

41

World Economic Forum (2025). “ INC-5.2: The global plastics treaty talks - here’s what just happened,” in World Economic Forum. Available online at: https://www.weforum.org/stories/2025/08/global-plastics-treaty-inc-5-2-explainer/ (Accessed September 8, 2025).

42

Xu S. (2024). Environmental legislation analysis improvement approach of global marine plastic pollution from the perspective of holistic system view. Front. Mar. Sci.11. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1481635

43

Xu Q. Zhang M. Guo P. (2023). Reflections on Japan’s participation in negotiations of the global plastic pollution instrument under international environmental law. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1323748

44

Yu R.-S. Yang Y.-F. Singh S. (2023). Global analysis of marine plastics and implications of control measure strategies. Front. Mar. Sci.10. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1305091

45

Zhou J. Luo D. (2024). The global governance of marine plastic pollution: rethinking the extended producer responsibility system. Front. Mar. Sci.11, 1363269. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1363269

Summary

Keywords

common but differentiated principle, global plastics treaty, marine plastic governance, non-regression, progressive standards, unified monitoring

Citation

Xu B (2025) Marine plastic governance driven by progressive standards: against the backdrop of global plastics treaty negotiations. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1751123. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1751123

Received

21 November 2025

Revised

30 November 2025

Accepted

03 December 2025

Published

17 December 2025

Volume

12 - 2025

Edited by

Yi-Che Shih, National Cheng Kung University, Taiwan

Reviewed by

Muhammad Rheza Ramadhan, Ministry of Finance of the Republic of Indonesia, Indonesia

Wei-Chung Chen, Hokkaido University, Japan

Updates

Copyright

© 2025 Xu.

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Bohan Xu, bohan.xu@hotmail.com

Disclaimer

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.