94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Mar. Sci., 11 April 2025

Sec. Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture and Living Resources

Volume 12 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2025.1556758

Xiaodie Yan1

Xiaodie Yan1 Cong Zhang2*

Cong Zhang2*Crab is a traditional Chinese culinary ingredient with significant cultural, archaeological, and artistic research value. As a prized aquatic product in China, it has become a cornerstone of the nation’s aquaculture industry. Throughout history, crab culture has evolved, developing distinct temporal characteristics and cultural connotations. However, controversies surrounding the cultural significance of crabs and the disorganization of related research materials have hindered the study and dissemination of crab culture. This paper systematically reviews and analyzes crab culture data from various historical periods, exploring cultural features in ancient literary works, artistic appreciation, and crab-eating customs. It reexamines the cultural connotation of Chinese crabs from a novel perspective encompassing literature, art, and culinary practices, aiming to enrich the temporal aspects of crab culture and promote the harmonious development of crab culture alongside the modern aquaculture industry.

Crabs are traditional aquatic products in China, with crab farming being a pillar industry in the country’s aquaculture sector. The China Fisheries Yearbook 2024 reports an annual crab production of 1,177,408 tons, comprising 888,629 tons of freshwater cultured crabs (Chinese mitten crab) and 288,779 tons of marine cultured crabs (101,614 tons of swimming crabs and 157,012 tons of mud crabs) (Yearbook, 2024). Chinese mitten crabs, also known as hairy crabs or river crabs, play a more significant role in traditional Chinese crab culture than marine crabs. Historically, they were referred to as “rampant warrior,” “Guosuo,” and “non-intestine prince.” Today, the Chinese mitten crab aquaculture industry is crucial for rural economic development and revitalization in China. Furthermore, its rich cultural and artistic value is evident throughout history. In contrast, marine crabs have a less prominent position in traditional Chinese crab culture due to their primary distribution in China’s southeastern coastal regions, which were historically less economically and politically significant areas.

To systematically explore the cultural significance of Chinese crabs and their temporal characteristics, this paper primarily focuses on freshwater crabs, particularly the Chinese mitten crab. The practice of crab consumption in China dates back over five millennia. Archaeological excavations in the Yangtze River Delta, specifically of the Songze culture in Qingpu, Shanghai, and the Liangzhu culture in Yuhang, Zhejiang, have unearthed numerous crab shells among ancestral waste, indicating a long-standing tradition of crab consumption in Chinese society. Culture represents not only spiritual wealth but also the manifestation of social material civilization. This tradition, spanning thousands of years, has been preserved and evolved through the contributions of literati and artists, giving rise to various cultural expressions in painting, literature, and cuisine. Countless scholars and artists have left behind a rich crab-related cultural heritage through literary works (such as poems, ci-poems, ballads, essays, and novels) and artistic creations (including paintings, calligraphy, and sculptures). These works not only highlight the biological characteristics and nutritional value of crabs but also encapsulate the emotions and philosophical reflections of the literati, imbuing them with deeper cultural significance and establishing crab culture as a unique symbol within Chinese tradition. Currently, the concept and definition of crab culture remain ambiguous, with relevant research scattered across literary and artistic domains, lacking systematic and academic analysis. This paper aims to refine the concept and definition of crab culture by collecting and analyzing data from various historical periods. It also seeks to enrich and appreciate the influence of crab culture by examining its characteristics in literature, art, and crab-eating customs, thereby promoting the development of crab culture and enriching the content of Chinese traditional culture.

During the golden autumn season, the tradition of enjoying crabs and appreciating chrysanthemums has been a cherished pleasure for countless scholars and ordinary individuals alike. As a traditional Chinese culinary ingredient, crab is renowned for its delectable taste and nutritional value. Numerous literati have extolled its virtues through poetry and prose, resulting in a rich corpus of literary and artistic works dedicated to this delicacy. With the development of the times and the renewal of people’s cognition, the connotations of crab culture are constantly enriched. Zhao (2004) proposed that crab culture generally refers to people’s understanding of crabs, including utilization and industry (Zhao, 2004). Zhu (2006) divided crab culture into three aspects: crab hometown culture, crab-eating culture, and crab chant culture (Zhu, 2006). Specifically, Crab hometown culture focuses on geographical regions renowned for crab production, integrating the crab's physiological morphology, flavor profiles, and culinary practices. This cultural dimension employs poetic narratives to document, celebrate, and articulate regional identity through crustacean-centered discourse.

Historical evidence indicates that three primary regions in China are renowned for producing crabs of exceptional quality: Yangcheng Lake in Jiangsu, Baiyangdian in Hebei, and the ancient Danyang Lake area spanning the Jiangsu and Anhui provinces. The superior quality of Yangcheng Lake crabs is notably highlighted in a poem by Tang Guoli (wife of Zhang Taiyan), which states, “If Yangcheng Lake crabs weren’t so delicious, why bother living in Suzhou?” Crab consumption culture encompasses the creation of various flavored crab dishes, including drunken crabs, honey crabs, and sugar crabs. Technological advancements have led to a diversification of crab processing products, primarily categorized into food (such as crab roe sauce, crab roe meal, dried crab meat products, and quick-frozen crab meat) and health supplements (including astaxanthin and organic calcium) (Xu et al., 2024). Despite the appeal of crab’s flavor, the peculiar morphological characteristics of crabs are often subject to ridicule. This paradoxical aspect has evolved into a significant component of crab-related literary and cultural traditions. Xu Wei, a famous writer and painter in the Ming Dynasty, once wrote a poem, which reads as follows: “In the village alongside rivers, the crabs are plump when the rice is ripe. The two cheliped of the crabs stand up like a halberd in the green mud of the paddy field. If you turn them over, you see a round and bulging navel like Dong Zhuo’s belly button.” While praising the fatness of crab meat, this poem also uses metaphor to satirize Dong Zhuo, a tyrannical traitor. Naturally, this kind of direct metaphor with the appearance characteristics of crab is slightly shallow.

Cui and Ning (2019) propose that crab culture encompasses the collective material and spiritual achievements formed through human interaction with and utilization of crabs (Cui and Ning, 2019). The concept of crab culture is multifaceted and extensive, encompassing human understanding of crab biology, fishing practices, culinary traditions, cultural appreciation, and associated techniques. This includes fishing methods, breeding techniques, folk traditions, food preservation processes, anecdotes, and linguistic customs. Furthermore, it encompasses literary and artistic expressions such as poetry, essays, novels, paintings, and sculptures. Crab culture is dynamic, continually evolving with societal progress and development, intersecting with various aspects of literature, art, cuisine, biology, and spiritual civilization. It has become an integral part of Chinese lifestyle and cultural identity, representing a unique cultural resource developed over a long historical period. As such, crab culture holds significant theoretical and practical value in areas including cultural theory development, spiritual civilization construction, promotional applications, and multidimensional industry growth.

Chinese culture boasts a rich history, with the literati’s deep-rooted love for poetry stemming from millennia of cultural heritage and natural philosophy. Poetry serves as a medium for expressing emotions and aspirations, encapsulating life experiences, the grandeur of landscapes, historical shifts, and even subtle emotional nuances within its verses, creating a distinct cultural tapestry. The crab, with its unique appearance and flavor, has emerged as a favored subject for poetic contemplation, particularly following the Tang Dynasty when crab-themed poetry reached new heights. The Complete Collection of Tang Poetry features numerous crab-related works by renowned poets. Notably, most authors of crab poetry in the Tang Dynasty were distinguished literary figures, with ordinary poets rarely addressing the subject. This suggests that upper and middle-class literati had greater exposure to and understanding of crab culture, enabling them to produce related works. The distribution of crab poems in the Tang Dynasty can be broadly categorized into four periods: early, prosperous, middle, and late Tang, with the majority being from the middle and late eras. This pattern indicates a potential correlation between crab-eating culture and socioeconomic development. During the early and prosperous Tang periods, the economic and political center was primarily Chang’an, distant from the southern Yangtze River region where crabs originated, limiting literati’s exposure to crab culture. However, following the Anshi Rebellion, Jiangnan’s economy and culture flourished rapidly, popularizing crab-eating culture. Poets across various social strata began to appreciate and focus on crab culture, resulting in an increase in crab-related literary works, including those by renowned poets such as Li Bai (701-762), Zhang Zhihe (732-774), Liu Zongyuan (773-819), and Du Mu (803-852) (Liu and Lai, 2019).

An important feature of crab poetry in the Tang Dynasty is that the content and subject matter are relatively single, and most of them are used by the authors to express feelings, among which the most frequently used is the crab cheliped. Li Bai, a famous poet in the Tang Dynasty, wrote in Drinking Alone Under the Moon that “The crab cheliped are like the delicious wine, and the hill piled up by the wine lees is like the Penglai fairy mountain; Let’s drink fine wine and get drunk on the high platform by the moonlight.” (Table 1). This allusion cites the description in the Bi Zhuo Biography in Jin Shu in which Bi Zhuo states that holding crab cheliped and drinking is the greatest pleasure in life (Table 2). Li Bai borrows this allusion in this poem to express his love for life and his yearning and pursuit of a better life. It is the embodiment of the unique understanding and aesthetic pursuit of dietary life in ancient Chinese culture to elevate the ordinary dietary life to the height of art and philosophy. Zhu Zhenbai, a poet in the Southern Tang Dynasty, wrote in Chanting Crabs that “Crabs’ eyes are like cicadas, body like turtles, and legs like spiders, they never goes towards people in the front. Now placed on the plate in a banquet, they can never roam about the world like before.” (Table 1). This poem vividly describes the biological characteristics of the Chinese mitten crab, such as its eyestalks, limbs, and horizontal crawling. The author expresses the general’s achievements in resisting the enemy and maintaining order by satirizing the crabs that are now cooked and can no longer run rampant. Therefore, the Chinese mitten crab is often used as a metaphor for the image of negative characters, such as the evil man who is rampant or evil (Qian, 2007).

Throughout China’s historical evolution, cultural development reached its zenith during the Song Dynasty. Chen Yinke observed that the culture of the Chinese nation, having evolved over millennia, attained its pinnacle in this era. Distinct from other dynasties, the Song Dynasty’s societal ethos of “respecting civil officials and diminishing military generals” fostered widespread improvement in the populace’s quality and cultural dissemination. This manifested in literature and art transcending clan boundaries and progressively becoming more civilian-oriented, secular, and universal. Concurrently, crab culture flourished within this context, as evidenced by a substantial increase in crab-related works and thematic diversity. Unlike the Tang Dynasty, the Song period witnessed a significant surge in crab-themed poetry. Notably, individual authors produced an impressive volume of such works: Lu You composed 51 poems, Mei Yaochen and Fang Yue each created 21, while Su Shi and Huang Tingjian both authored 20. This proliferation indicates that during the Song Dynasty, crabs were no longer exclusive to the elite but had permeated ordinary households, becoming a commonplace element in secular life.

The literati in the Song Dynasty created a large number of poems about crabs, indicating the popularity of crab-eating customs and the literati’s purposeful enrichment and construction of the crab cultural connotation, which reflected the changes in the aesthetic lives of the literati in the Song Dynasty. With the surge in the number of works, the themes also became rich and diverse. In addition to the crab-like lyrics in the Tang Dynasty, there are also simple crab-chanting poems, crab-tasting poems, pastoral poems, inscription poems, and game poems. For example, Liu Ban, a famous historian in the Song Dynasty, wrote in Crab that “Rice paddies ripen in the fall, and the water is rippled with microwaves. The autumn crabs have been caught in the net. They taste good and are perfect with wine, the flavor is the best match for oranges. The thin shells are as if stained by rouge, and the crab paste is like congealed amber. If the crabs had known that they would be cooked in big pod, would they have been rampant?” (Table 1). The poem refers to the time when the frost falls and the rice and oranges are ripe, which is suitable for crab fishing and eating, and wine and oranges are the best condiments. In addition, the crab shell seems to have been stained with rouge because the cooked crab shell denatures the protein and separates from astaxanthin due to high temperature, and astaxanthin appears red, and the plump crab paste refers to the mature gonads. It shows that the author is experienced and skilled in eating and tasting crabs, and at the end of this poem, he uses crabs to satirize tyranny that will have evil consequences. Lu You, a patriotic poet in the Southern Song Dynasty, had a poor life and poor vision in his later years, but he preferred to eat crabs. In the Recovery, he wrote, “The sight of crab paste makes my mouth salivate, and the first sip of liquor brightens my old eyes.” (Table 1). He uses plump crabs as appetizers, and his faint old eyes brightened with joy, which showed his love for eating crabs. In Traveling Lushan Get Crabs, Xu Sidao wrote, “Not visiting Lushan fails the eyes, and not eating crab fails appetite” (Table 1), which is a more figurative presentation of delicious crab. Su Shi, a great writer in the Northern Song Dynasty, not only liked to cook and eat crabs but also liked to write about and paint crabs. In Ding Gongmo Sends Mud Crab, he wrote, “Half the shell filled with crab roe is perfect for sipping wine, while the two cheliped with snowy white meat encourage one to eat more.” (Table 1). Although the crab is not plump, the aroma of crab roe is still a delicacy, and with the help of wine, the narrator’s appetite soars. With just a few words, the appearance of gluttonousness is presented, which has an intoxicating artistic appeal.

In addition, there is a large number of singing and game poetry works in Song ci-poems where friends give crabs to each other, such as Ginger Fish Crab of Qin Guan, Send Preserved Crab to Zhao Jinchen of Xin Qiji, Divide Preserved Crab and Send to Shen Shou Rhyme Again of Chen Zao, and Preserved Crab Presented to Yu Chayuan of Jiang Teli (Table 1). Therefore, people usually liked to give preserved crabs to friends in the Song Dynasty. In ancient times, crab preservation technology was primitive, and it was easy to cause death when transported. The use of rice wine and other condiments made by farmers to make a drunken sauce not only prolongs the shelf life of the crab but also makes it delicious, which may be the main reason for giving away liquor-saturated crabs (preserved crabs). Moreover, poetry, wine, and tea were elegant things preferred by literati in ancient times. Pickling crabs with wine also increased the interest in and elegance of crab tasting.

The Song Dynasty literati composed numerous poems about crabs, focusing on ordinary and trivial aspects of daily life. This emphasis reflected similarities in the daily experiences and diets of scholars and the general public. Such a shift in the scholars’ life attitudes and ideological perspectives represents a progression, illustrating the convergence of scholarly culture with secular everyday life and recreational pursuits through crab-related themes. Crab consumption transcended mere physiological sustenance, achieving an emotional, spiritual, and aesthetic sublimation. The Complete Collection of Tang Poetry contains 48 crab-related poems, while the Complete Collection of Song Poem includes 891, marking a substantial increase. Another significant literary form of the Song Dynasty, the Complete Collection of Song Ci-poem, features 82 works about crabs (Table 2). The creators of these works represent a diverse range of identities, including renowned literary figures such as Ouyang Xiu, Wang Anshi, Su Zhe, Su Shi, Mei Yaochen, Huang Tingjian, Xin Qiji, Lu You, Fan Chengda, and Yang Wanli, as well as lesser-known authors such as He Jiezhi, Huang Fuzhi, Cao Xun, Chen Junqing, and Ge Qigeng. The contributors also encompass emperors, nobles, generals, and officials such as Song Gaozong, Cai Xiang, Jia Sidao, and Wen Tianxiang, alongside religious figures such as Bai Yuchan and Shi Chongyue. In essence, crab culture in the Song Dynasty reached a zenith, with the consumption, appreciation, and poetic celebration of crabs becoming a ubiquitous aspect of life across all social strata. Furthermore, this cultural phenomenon demonstrates the widespread appreciation for crabs and integrates the spiritual connotations of crab culture with folk traditions, forging a new paradigm of aesthetic living in the Song Dynasty. For the people of this era, crab culture extended beyond physiological enjoyment, evolving into a means of emotional expression and aesthetic elevation.

The Yuan Dynasty marks a significant period in Chinese history as the first unified nation established by ethnic minorities. However, due to complex social class and ethnic tensions, economic and social development remained stagnant for an extended period. The Han people, who were the primary carriers of crab culture, experienced a decline in social status, leading to a gradual diminishment in the propagation of crab-related customs. Nonetheless, the Yuan Dynasty’s frequent foreign expeditions and exchanges resulted in an influx of diverse foreign spices. This culinary expansion had a notable impact on the preparation and consumption methods of crabs, contributing to the evolution of crab cuisine during this era.

By the Ming and Qing Dynasties, due to the country’s social stability and economic prosperity, crab culture was gradually revived and developed. In the poem Inscription Crab by Xu Wei in the Ming Dynasty wrote, “In the village alongside rivers, the crabs are plump when the rice is ripe. The two cheliped of the crabs stand up like a halberd in the green mud of the paddy field. If you turn them over, you see a round and bulging navel like Dong Zhuo ‘s belly button” (Lan, 2016) (Table 1). Xu Wei was a famous painter in the Ming Dynasty. He gave the crab in the painting a fresh life, and used it to ridicule the incompetent feudal dignitaries. As one of the four great masterpieces in Chinese literature, the Dream of Red Mansions (Table 2) occupies a significant position in literary history. Its author, Cao Xueqin, was not only a renowned writer but also a connoisseur of crab consumption. The text frequently describes, through its characters, the methods and precautions associated with eating crabs. During the Qing Dynasty, Sun Zhilu authored Crab Record, Later Crab Record, and Continued Crab Record (Table 2). These works compiled extensive information about crabs, encompassing their understanding, historical tracing, consumption taboos, emotional associations, and related literary works. This wealth of data stems from the millennia-long accumulation of crab culture. By the reigns of Emperors Kangxi and Qianlong in the Qing Dynasty, crab culture had flourished considerably. In the Ming and Qing Dynasties, the literati class gradually refined the art of crab consumption (Liu, 2008). The initial set of three utensils evolved to include 4, 6, 8, 10, 12, and even up to 64 pieces. The emergence and increasing complexity of crab-eating utensils reflect the further development and sophistication of crab culture.

The cultural significance of crabs extends beyond literary works, manifesting prominently in various artistic domains, including painting and sculpture.

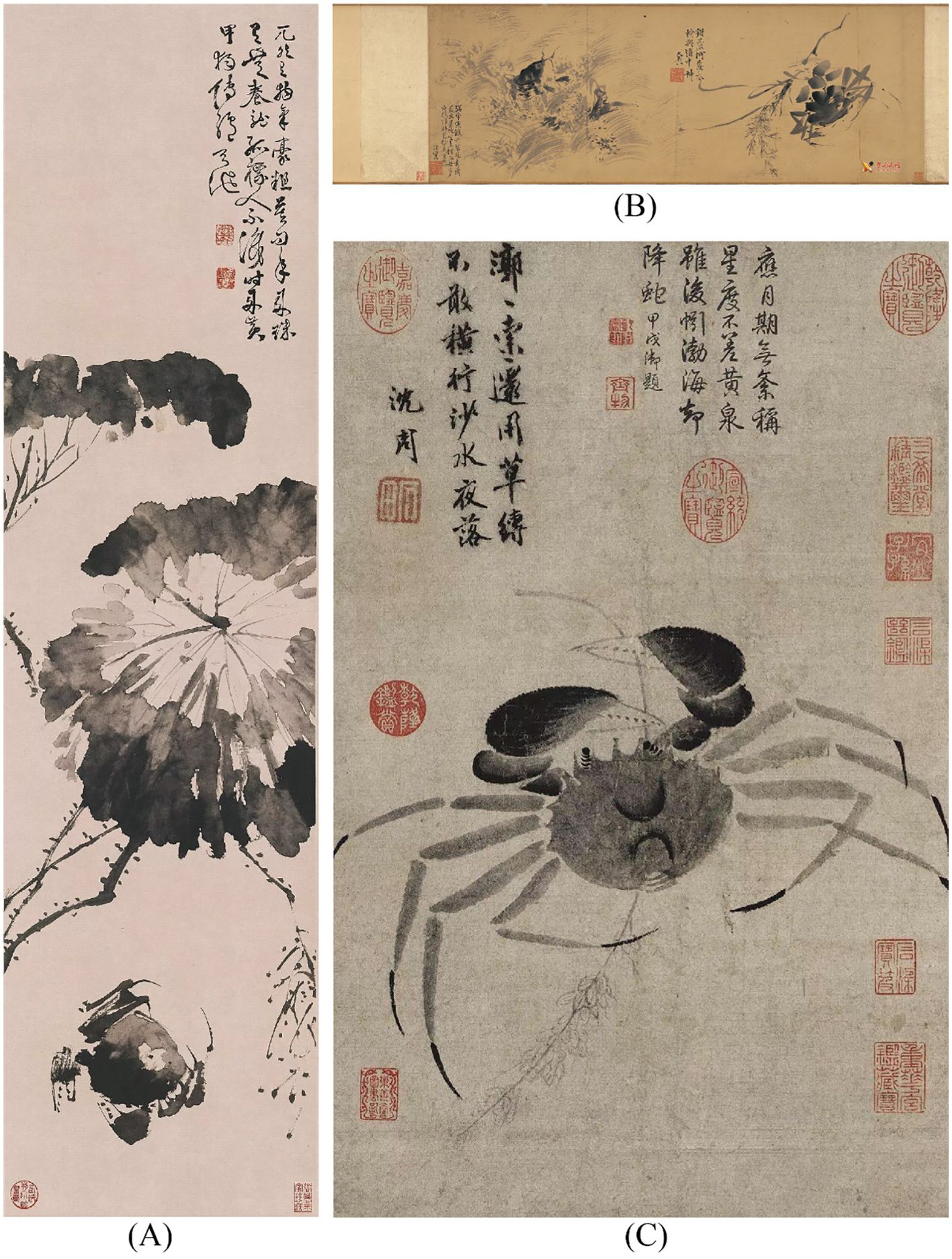

Since ancient times, Chinese painters have depicted crabs, infusing them with emotions and conveying the pride, frustration, satire, and self-mockery of the literati, thereby greatly enriching the cultural significance of crabs in art. Among the numerous crab paintings, those by Ming Dynasty artist Xu Wei stand out as particularly distinctive. Xu Wei, renowned for his artistic prowess, built upon and expanded the creative calligraphic style in painting that originated in the Song and Yuan Dynasties. He incorporated wild cursive lines and dripping ink techniques into his artwork with exceptional brush and ink skills, thus establishing a new pinnacle in freehand painting. Xu Wei created numerous crab-themed paintings, often utilizing the diverse characteristics of crabs to critique social phenomena. For instance, in Golden Armor Chart (Figure 1A) (Table 2), the composition is succinct and the layout innovative. It depicts withering lotus leaves and a crab crawling slowly, appearing rather ungainly. Although this crab painting comprises only a few strokes, it incorporates various brushwork techniques such as thick, light, dry, hook, point, and erase. The crab’s form is rendered in a freehand style, yet its texture, shape, and expression are all vividly portrayed. In the upper right corner of this painting, Xu Wei inscribed a poem. The term “Golden Armor” in the poem refers to the crab, symbolizing the list of successful candidates in ancient imperial examinations. Similarly, in the painting, the awkward crab represents those who lack literary talent but pass the imperial examination through improper means. Through this clever symbolic technique, Xu Wei expressed his criticism of social phenomena and his disdain for those who achieved success through power and wealth rather than merit. This painting is not merely an artistic display but also a sharp satire on the social atmosphere of that era. As a crab painting, Golden Armor Chart has become a classic masterpiece of Chinese painting and a testament to Xu Wei’s artistic talent. Beyond expressing satire, the painter also demonstrated genuine appreciation for crabs themselves. For example, Crab and Fish (Figure 1B) (Table 2) is a poetic and enigmatic ink painting. On the left side, it depicts a crab holding a reed with its cheliped, as if making an offering to the sea god; on the right, it portrays a fish leaping from the water, resembling a dragon, full of mystery. Xu Wei vividly captured the images of crabs and fish and inscribed poems describing the scenes in the painting, thereby imbuing the artwork with additional artistic depth.

Figure 1. (A) Xu Wei, Ming Dynasty, Golden Armor Chart, collection of the Beijing Palace Museum, China; (B) Xu Wei, Ming Dynasty, Crab and Fish, collection of Tianjin Museum, China; (C) Shen Zhou, Ming Dynasty, Guosuo Chart, collection of the Beijing Palace Museum, China.

Furthermore, the Guosuo Chart (Figure 1C) (Table 2), created during the Ming Dynasty by the artist Shen Zhou, employs light ink to delineate crab shells and limbs while utilizing burnt ink to depict claw tips and the contours of the crab shell. The thick ink renders the double chelipeds, vividly portraying a scene of a vibrant freshwater crab amid aquatic vegetation. This painting effectively captures both the fierce and endearing aspects of the crab, presenting a unique artistic perspective.

During the Qing Dynasty, Zhang Pan created Double Crabs Fan (Figure 2A) (Table 2), which portrays two crabs traversing grass with remarkable vitality. The crabs are rendered using the mogu (boneless) technique, featuring refined pigmentation and simple brushwork. The inscription’s placement complements the painting’s theme, reflecting the literati’s leisurely elegance, exemplifying an intriguing late-career work by Zhang Pan. Additionally, Crab Selling (Figure 2B) (Table 2), a genre painting by artist Luo Ping in the Qing Dynasty, depicts a market scene where a crab seller and buyers engage in a dispute. The overturned crab basket draws onlookers who either join the argument or attempt mediation. Only a child remains detached, observing with fascination as the crabs escape. The painting features six individuals, each with distinct identities and expressions vividly portrayed. This small-scale fan captures a lively market confrontation, transforming life’s unpleasantries into artistic beauty, showcasing the painter’s skill and the noble aspirations of literati painting.

Figure 2. (A) Zhang Pan, Qing Dynasty, Double Crab Fan, collection of the Beijing Palace Museum, China; (B) Luo Pin, Qing Dynasty, Crab Selling, collection of Central Academy of Fine Arts, China.

Among modern painters renowned for crab paintings, Qi Baishi stands out as the most significant painter. His works frequently depict autumn crabs alongside wine kettles and glasses, portraying warm scenes of wine consumption and crab tasting. Qi Baishi’s extensive crab-themed portfolio includes works such as Two Crab Walking, Reed Crab, Ink Crab, Crab, Basket Crab, Crab Swarm, and Five Crabs (Figure 3) (Table 2). His depictions of crab and wine consumption are characteristically simple, with bright red crabs rendered in a few strokes, complemented by fine wine. These images evoke viewers’ appetites and resonate with a sense of contentment and joy. Qi Baishi once remarked, “Behind my Jiping Hall, there is a well beside a stone. On the ground around the well, autumn moss is spread evenly, green and gray, intertwined, and there are often plump crabs running across it. I observed them carefully and found that although the crabs had many limbs, they did not walk disorderly, which was not known to the painters.” This statement reflects his meticulous observation, resulting in beautifully vivid crab paintings. Moreover, Qi Baishi imbued crabs with symbolic meaning in his works. During the Anti-Japanese War, he painted a crab with the inscription “See how long you can keep your arrogant ways,” expressing his disdain for the Japanese invaders and his faith in China’s eventual victory. Qi Baishi’s crab paintings thus demonstrate not only high artistic achievement but also the painter’s patriotic sentiments.

Lu Xun once proposed that the first person to eat crabs was admirable, and only warriors dared to eat it. So, who was the first person to eat crab? According to folklore, in the Dayu period, crabs were called pinch-human insects. There was a flood control supervisor called Ba Jie during the Dayu period. When he boiled the crab with boiling water, he smelled a unique fragrance and tasted it to find a unique delicacy. This was the first attempt. Since then, the crab has been passed down from generation to generation as a human delicacy. In order to better reflect crab culture and water culture and carry forward the courage and spirit of daring to be the first in the world, Ba Jie Park was built in Kunshan City, China.

In Ba Jie Park, there are many sculptures of crabs. For example, when one enters the park, the first thing that catches one’s eyes is a huge marble sculpture (Figure 4A). The pond is full of clear green water, and a crab has climbed on the top of a white boulder to look up at the sky, which is very artistic. The citizens of Kunshan City have a deep relationship with crabs, and this stone sculpture, weighing more than 10 tons, is a testament to it. Children playing on the backs of crabs show that people are living happily (Figure 4B). In addition, crabs have had a connotation with wealth since ancient times, and people expect themselves to be full of wealth or talent (Figure 4C). There are a variety of tableware for tasting crabs on the stone round platform in the crab tasting pavilion, and the eight crabs for eating in Jiangnan are very famous, turning eating crab into a thing of elegance and pleasure (Figure 4D).

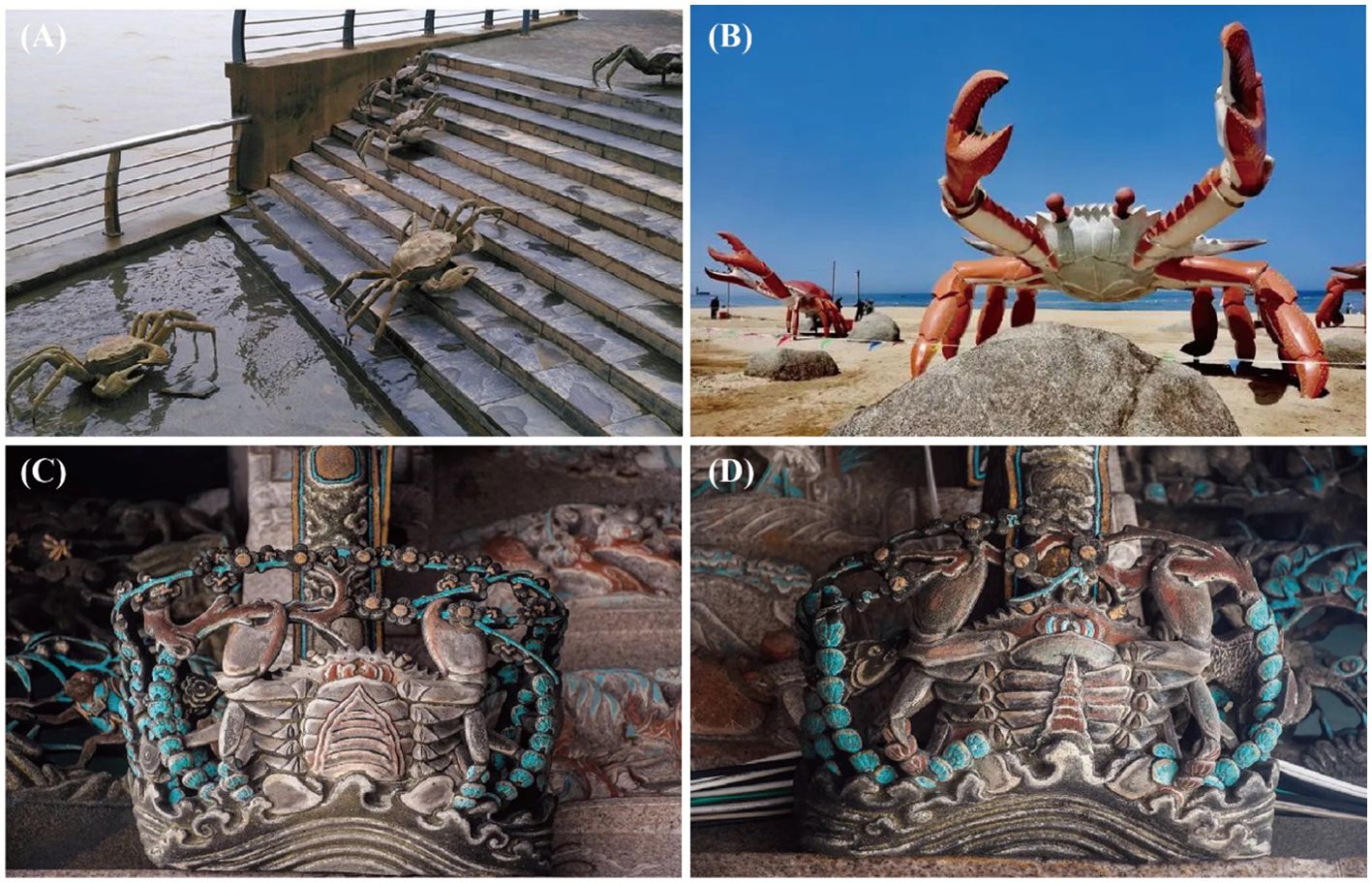

In the Wuhu Riverside Park (Wuhu City, China), there are several crab sculptures (Figure 5A) that climb up the marble steps, make threatening gestures, and run amuck. This styling is exaggerated and witty. Zhaoyuan City, with the reputation of being the gold capital, has the largest gold reserves in China and the coast is known as the sandy gold coast. If the desire for gold is the pursuit of the material, the yearning for mountains and seas is the enjoyment of the spirit. The most brilliant sculpture on this seaside is the crab with threatening gestures, commonly known as the crab general, showing the mighty majesty of the general (Figure 5B).

Figure 5. (A) Crab sculpture in Wuhu Riverside Park, Wuhu City, China; (B) Crab sculpture on the coast of Zhaoyuan City, China; (C, D) Crab sculptures at Congxi Ancestral Hall, Chaozhou City, China.

In addition to sculptures, there are records of crab culture in stone carving. In the Congxi Ancestral Hall (Chaozhou City, China), the stone carving of the shrimp and crab basket shows the scene of shrimp and crab swimming into the bamboo basket, which means a great harvest. The species recorded here are mainly marine crabs. The stone carvings include lobsters, crabs, and other marine fish, reflecting Congxi’s preference for seafood and coastal people’s yearning for a harvest and diet (Figure 5C, male crab; Figure 5D, female crab).

China has a long history of crab eating, and in the long accumulation of food culture, a unique crab-eating culture has been formed. In the Western Zhou Dynasty, the Annotation of Hu People in Tian Gong of Zhou Li had a record of eating crabs, which were mainly made into crab paste as a tribute for the King of Zhou. Although eating crabs has a long history, the real trend prevailed in the Ming and Qing Dynasties. Cao Xueqin describes the scene of holding crabs and appreciating osmanthus flowers with more space in Dream of Red Mansions, and the protagonists in the book, Jia Baoyu, Lin Daiyu, and Xue Baochai, all wrote crab poems. From the perspective of literature, the crab poems of the different characters in the book have their own merits, and the description of crabs is very penetrating, indicating that the author is familiar with crab biology and crab-eating culture. From the perspective of folk culture, the three poems make many intriguing comments on crab-eating behavior. There are many ways to eat crabs, such as steamed, boiled, and drunk crabs, among which the most common way is steamed, with onion and ginger the most important ingredients. There are many precautions one must take when eating crabs, as the crab stomach, heart, intestines, and gills are inedible. Therefore, in the development of crab eating, many important crab-eating utensils have been derived, the most famous is the Eight Pieces of Crabs, including a hammer, anvil, pliers, shovel, spoon, fork, scraper, and needle. It is rumored that the Eight Pieces of Crabs in Suzhou City is one of the indispensable dowries, which shows that crab-eating culture has been integrated into the daily life of the people in Jiangnan, China.

During the Mid-Autumn Festival, drinking and eating crabs gradually became a cultural enjoyment of lyricism, and literati are active advocates of this fashion. Literati actively promoted this custom, resulting in the continuous emergence of elaborate verses praising crabs. For thousands of years, many popular works have been handed down, deriving and developing China’s endless crab culture. Many of the literary and artistic works of crab-chanting have already been described above and will not be repeated here.

Crab-eating, crab-tasting, crab-chanting, and crab-appreciating are integrated into Chinese life. Crab-eating is not only a kind of elegance and lyricism, its rich nutritional value is a powerful boost to the popularity of crab eating. The ancients usually used ‘‘Crab roe, crab paste, and crab jade’’ to describe the plumpness and deliciousness of crabs, which actually refers to different tissues of crabs, and the nutrients are different.

In general, the main nutrients of the edible part of crab include proteins, lipids, and mineral elements (Wang et al., 2024). Crab roe refers to the hepatopancreas and ovaries, and the main nutrients are lipids, mainly unsaturated fatty acids, with high contents of oleic acid, palmitic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), and docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) (Tang et al., 2014, 2013). Fatty acids are one of the main energy sources for the body, and have a variety of physiological functions, such as lowering blood lipid, mental development, and memory (Wang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2013). In addition, fatty acids, especially polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs), are essential for meat to produce an aroma after heating (Kimata et al., 2001; Pedraja, 1970). It was reported that n-3 and n-6 unsaturated fatty acids are one of the main sources of volatile flavor substances in fish (Turchini et al., 2004). The rich lipid composition of crab roe is closely related to its unique flavor (Ying et al., 2006). Crab jade usually refers to crab meat, which is mainly protein. Many studies have reported that the crude protein content of the edible parts of Chinese mitten crabs are approximately 15%–20% protein, and there is little difference between female and male crabs (Li et al., 2000; Yang et al., 2014; Zhao et al., 2016). Amino acids are the basic substance of protein. At present, 18 kinds of amino acids have been detected in the edible part of Chinese mitten crabs and the free amino acids mainly include proline, arginine, glycine, and alanine (Chen et al., 2007). Glutamic acid is a characteristic amino acid with an umami taste and sarcosine has a synergistic effect on sweetness and meat taste. Moreover, the metabolites of sulfur-containing amino acids, such as cystine, cysteine, and methionine, are precursors of many volatile aroma compounds. Therefore, crab meat is rich in amino acids and sulfur-containing amino acids, which is an important reason for its delicious flavor (Hayashi et al., 2022; Xu et al., 2003). Crab paste mainly refers to the gonads, accessory sex glands, and secretions of male crabs, and its main nutrients are amino acids. A study of Chinese mitten crab in Yangcheng Lake found that the content of 13 amino acids in male crabs were significant higher than that in female crabs, including glutamic acid (16.6% higher), proline (23.3% higher), and alanine (28.5% higher) (Li et al., 2000).

In addition, the higher nutritional value of Chinese mitten crab is also reflected in the rich mineral elements, such as zinc, iron, copper, and phosphorus (Huang et al., 2013). It was reported that in the edible part, the iron content was approximately 13 mg per 100 g, which is 10-fold that of freshwater prawn, and 5.5-fold that of carp and crucian carp. Furthermore, the content of calcium is approximately 129 mg per 100 g, which is 1.3-fold that of freshwater shrimp and 2.5-fold that of carp and crucian carp. The content of phosphorus is as high as 150–180 mg (Zhao, 2004). In addition, there are many kinds of substances that affect the flavor of Chinese mitten crab, including nitrogenous compounds, non-nitrogenous compounds, and volatile flavor compounds. Nitrogen-containing compounds include free amino acids, nucleotides, glycine, and betaine; non-nitrogen compounds mainly include lactic acid, glucose, and inorganic ions; volatile flavor substances mainly include hydrocarbons, alcohols, aldehydes, ketones, esters, nitrogen, and sulfur compounds (Wang et al., 2024).

The crab aquaculture industry in China has experienced rapid development, and the total output exceeded 1.1 million tons in 2023. The crab breeding industry is an important pillar industry in China ‘s aquaculture industry, and it is also a pillar industry for farmers in rural areas to get rich. The cultural integration of the whole process of industrial development has a strong role in promoting the development of the industry. Many scholars have proposed to integrate and promote the sustainable development of the crab industry by advocating for crab culture (Fan et al., 2005; Zhang, 2012). With the development of the crab industry and the expansion of the related industrial chain, the protection, utilization, and creative transformation of crab cultural resources should be paid attention to. Crab culture is a lifestyle and cultural phenomenon of the Chinese people that has been continuously accumulated and developed over thousands of years of history, and different stages of historical development have been endowed with richer cultural connotations. In modern society, crab culture has been rapidly spread with economic development. The development of crab culture is also nurturing and promoting economic development, and gradually forming a crab culture economy. Crab culture and economic development have the historical characteristics of synergy, which is mainly manifested in the fact that crab culture is the internal driving force to promote the development of the crab industry and market innovation, and its development can also promote economic development. In the era of the market economy, crab culture and the economy blend, and consciousness of cultural consumption is increasingly prominent. Although people no longer create chanting poetry or paintings when eating crabs, they have developed crab sculptures or other handicrafts as a new medium for the spread of crab culture. The spread of crab culture has made crab eating a unique food culture in Chinese culture, which has been inherited and developed while integrating with and developing alongside the crab industry.

XY: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. CZ: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This study was conducted with government support through the following grants: the Natural Science Foundation of Jiangsu Province (BK20240584), the Natural Science Foundation of the Higher Education Institutions of Jiangsu Province, China (24KJB240002), and the Scientific Research Foundation for Introduce Talent, Nanjing Normal University (184080H201B65).

We acknowledge TopEdit LLC for the linguistic editing and proofreading during the preparation of this manuscript.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Chen D. W., Zhang M., Shrestha S. (2007). Compositional characteristics and nutritional quality of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Food Chem. 103, 1343–1349. doi: 10.1016/j.foodchem.2006.10.047

Cui W., Ning B. (2019). Development and application of crab culture in the development of Chinese mitten crab industry of Shanghai. Aquac. Res. 50, 367–375. doi: 10.1111/are.2019.50.issue-2

Fan B., Luo F., Wang Y. (2005). Research on the development strategy of Jiangsu crab industry. China fish. econ. 6, 56-59.

Hayashi T., Asakawa A., Yamaguchik K. (2022). Studies on flavor components in bolied crabs sugors, organic acids and minerals in the extracts. Bull. Jpn. Soc Sci. Fish. 45, 1325–1329. doi: 10.2331/suisan.45.1325

Huang C., Yang P., Han Q. (2013). Nutrients analysis on the edible parts of Eriocheir sinensis H. Milne-Edwards. Food. Mach. (Chinese). 29, 61–65.

Kimata M., Ishibashi T., Kamada T. (2001). Studies on relationship between sensory evaluation and chemical composition in various breeds of pork. Jap. J. Swine. Sci. 38, 45–51. doi: 10.5938/youton.38.45

Li S., Cai W., Zou S., Zhao J., Wang C., Chen G. (2000). Quality analysis of Chinese mitten crab Eriocheir sinensis in Yangchenghu Lake. J. Fish. Sci. China. 7, 71–74.

Liu X., Lai X. (2019). On the aesthetic trend of crab culture in Song dynasty from the Tang and Song Dynasty poetry. Gastron. Res. (Chinese). 36, 18–22.

Liu Y. (2008). First “crab culture history” in China - Talking Crab. J. Libr. (Chinese) 27, 95–96. doi: 10.13663/j.cnki.lj.2008.08.007

Pedraja R. (1970). Change of composition of shrimp and other marine animals during processing. Food Technol. 24, 356.

Tang C., Fu N., Wang X., Tao N., Liu Y. (2014). Comparison of fatty acid composition in Eriocheir sinensis cultured by purse net and pond. Freshw. Fish. 44, 84–89.

Tang C., Songqian C., Fu N., Liu Y., Tao N., Wang X. (2013). Lipid content and fatty acid composition of Eriocheir sinensis at different stages of growth. Food Sci. 34, 174–178.

Turchini G., Mentasti T., Caprino F., Panseri S., Moretti V., Valfrè F. (2004). Effects of dietary lipid sources on flavour volatile compounds of brown trout (Salmo trutta L.) fillet. J. Appl. Ichthyol. 20, 71–75. doi: 10.1046/j.0175-8659.2003.00522.x

Wang X., Han G., Ma B., Song J., Mu Y., Meng T. (2024). Differences of nutritional components in Chinese Eriocheir sinensis: research progress. Chin. Agr. Sci. Bull. 35, 122–128.

Wang J., Zhao S., Song X., Pan H., Li W., Zhang Y., et al. (2012). Low protein diet up-regulate intramuscular lipogenic gene expression and down-regulate lipolytic gene expression in growth–finishing pigs. Livest. Sci. 148, 119–128. doi: 10.1016/j.livsci.2012.05.018

Xu Q., Cui T., Liu J. (2003). Processing technology and analysis of chemical components of frozen crabmeat and roasted ovary of Eriocheir sinensis. Fish. Sci. 22, 12–14.

Xu F., Xing X., Zhang K., Zhang C. (2024). Status and prospects of product processing and sustainable utilization of Chinese mitten crab (Eriocheir sinensis). Heliyon 10, e32922. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e32922

Yang P., Li M., Huang C., Luo Y., Li N., Chen H., et al. (2014). Nutrients analysis and quality assessment of Eriocheir sinensis from datong lake, Hunan province. Oceanol. Limnol. Sinica. 45, 199–205.

Yearbook, C.F.S (2024). China fishery statistical yearbook (Beijing, China, 24: China Agriculture Press).

Ying X.-P., Yang W.-X., Zhang Y.-P. (2006). Comparative studies on fatty acid composition of the ovaries and hepatopancreas at different physiological stages of the Chinese mitten crab. Aquaculture 256, 617–623. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2006.02.045

Zhang Y. (2012). SWOT analysis and development strategic on crab aquaculture industry of Panjin city. Mod. Agr. Sci. Technol. (Chinese). 13, 308–309.

Zhang J., Wu D., Liu D., Fang Z., Chen J., Hu Y., et al. (2013). Effect of cooking styles on the lipid oxidation and fatty acid composition of grass carp (Ctenopharynyodon idellus) fillet. J. Food Biochem. 37, 212–219. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-4514.2011.00626.x

Zhao H., Wu X., Long X., He J., Jiang X., Liu N., et al. (2016). Nutritional composition of cultured adult male Eriocheir sinensis from Yangtze River. J. Fish. Sci. China. 23, 1117–1129.

Keywords: Chinese crab, culture connotation, social cognition, literature, art, aquaculture

Citation: Yan X and Zhang C (2025) The connotation of Chinese crab culture: a comprehensive review from the perspectives of literature, art, and diet. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1556758. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1556758

Received: 14 January 2025; Accepted: 26 February 2025;

Published: 11 April 2025.

Edited by:

Hongbo Jiang, Shenyang Agricultural University, ChinaReviewed by:

Xiaowen Long, Dali University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Yan and Zhang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Cong Zhang, emhhbmdjQG5udS5lZHUuY24=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.