94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci., 25 March 2025

Sec. Marine Fisheries, Aquaculture and Living Resources

Volume 12 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2025.1549055

The study aimed to evaluate the impact of guar gum (GG) with different viscosity on growth rate and gut health of pearl gentian grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀ × E. lanceolatus♂). Juvenile groupers (6.66 ± 0.08 g) were reared for 10 weeks and fed four different diets: three containing 8% GG with low, medium, and high viscosity (designated as GGL, GGM, and GGH, respectively), and a control diet, in which 8% GG was replaced with 8% cellulose. The results indicated that at an 8% inclusion level, all three viscosities of GG significantly reduced both growth rate and feed utilization, with the lowest values observed in the GGH group. Similarly, dietary inclusion of GG with various viscosity decreased the intestinal activities of lipase, alkaline phosphatase and lysozyme as well as the content of immunoglobulin M, increased the plasma diamine oxidase activity and endothelin-1 level. Additionally, dietary GG inclusion regardless of viscosity up-regulated the relative expressions of intestinal proinflammatory cytokines, while down-regulated the relative expressions of intestinal anti-inflammatory cytokines and tight junction proteins. Notably, dietary inclusion of 8% GGH decreased intestinal villus length and total antioxidant capacity but increased intestinal malondialdehyde and secretory immunoglobulin T contents. Dietary GG supplementation reduced the α-diversity of the intestinal microbiota and decreased the relative abundance of Proteobacteria and Firmicutes, while increasing the relative abundance of Fusobacteriota, particularly Cetobacterium. This shift in microbial composition was associated with decreased levels of acetic and valeric acids but increased levels of caproic and isovaleric acids. These findings indicated that when using GG as a feed binder, it is important to consider its viscosity, as excessively high viscosity may negatively impact growth rate and intestinal health.

Guar gum (GG), a viscous non-starch polysaccharides (NSPs) rich in galactomannan and derived from Cyamopsis tetragonolobus, is widely utilized in various industries due to its exceptional binding and thickening properties, making it a promising candidate for applications in food manufacturing and aquaculture (Tahmouzi et al., 2023). In mammals, GG has been extensively studied for its health benefits, including reductions in blood glucose level, cholesterol-lowering effect, modulation of gut microbiota, and alleviation of constipation (Owusu-Asiedu et al., 2006; Gee et al., 1983; Fu et al., 2019). Similarly, in fish, GG has shown potential to mitigate liver damage induced by high-fat diets and reduce endogenous glucose production (Enes et al., 2013; Zhao et al., 2024). Beyond its physiological benefits, GG is also valued in aquaculture for its ability to enhance feed quality by improving water stability, reducing nutrient leaching, and enhancing fecal stability, thereby minimizing water pollution and positioning it as an effective feed binder (Amirkolaie et al., 2005; Brinker, 2009).

However, as GG is added to feed, its inherent viscosity increases and liquidity decreases, which has been correlated with reduced nutrient digestibility in several fish species (Storebakken, 1985; Leenhouwers et al., 2006; Tu-Tran et al., 2020). Elevated dietary viscosity can impair nutrient absorption by altering the rheological properties of intestinal digesta, slowing down enzymatic hydrolysis, and reducing the diffusion of nutrients across the intestinal epithelium (Adebowale et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022a; Jang et al., 2024). Furthermore, high-viscosity diets may disrupt gut motility and microbial fermentation dynamics, potentially leading to suboptimal growth performance and compromised intestinal health (White et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2022b; Perera et al., 2022). Despite these concerns, previous researches in fish have primarily focused on the effects of GG at varying inclusion level on the growth performance across species, limited research has investigated how the viscosity of GG influences fish growth and nutrient absorption (Storebakken, 1985; Amirkolaie et al., 2005; Leenhouwers et al., 2006; Enes et al., 2013; Gao et al., 2019; Zhao et al., 2024). Furthermore, existing studies have demonstrated that GG exhibits higher viscosity in seawater than in freshwater, attributed to its ion-binding properties (Wang et al., 2015). Nonetheless, there is a significant gap in research regarding the effects of GG on marine fish species.

Grouper (Epinephelus spp.), a high-value marine fish prized for its superior meat quality, has witnessed a remarkable increase in aquaculture production. Driven by escalating market demand and advancements in farming technology, the worldwide output of grouper has increased thirtyfold over the past 20 years since the 21st century (FAO, 2022). China has consistently been at the forefront of global grouper production, with the pearl gentian grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀ × E. lanceolatus♂) emerging as the most significant cultured species for its rapid growth, high salinity tolerance, and robust disease resistance. In contrast to freshwater fish, groupers must continuously ingest seawater to maintain osmotic balance, which considerably affects the composition and viscosity of their intestinal contents. The gut, as the essential interface with the external environment, is crucial for preserving fish health by both facilitating nutrient digestion and absorption and defending against environmental toxins and pathogens (Su et al., 2020; Long et al., 2023; Liu et al., 2024). Furthermore, the intestinal microbiota further enhances fish health by aiding assimilation, modulating the immune system, and producing beneficial metabolites that improve resilience to diseases (Rajoka et al., 2021; Yu et al., 2024). Consequently, understanding the impact of GG viscosity in diets on intestinal health in groupers is of paramount importance. This study aims to explore the effects of GG, as a potential feed adhesive, on the growth and intestinal health of groupers, with a particular focus on how its varying viscosity influences these outcomes. The findings will provides foundational insights into how viscosity impacts intestinal health in fish, offering valuable information for the development of feed adhesives and their application in aquaculture.

Fish meal, chicken meal, soy isolate protein, and corn gluten meal were utilized as the primary protein sources, with soybean oil and fish oil serving as the lipid sources (Table 1). Four diets were formulated to be isoproteic and isolipidic, where the control diet used cellulose and wheat starch as carbohydrate sources, and 8% GG with low viscosity (GGL, 2500 mPa·s), middle viscosity (GGM, 5200 mPa·s), or high viscosity (GGH, 6000 mPa·s) respectively replaced cellulose in the other three diets. The guar gum with different viscosity was purchased from Guangrao Liuhe Chemical Co., Ltd. (Guangrao, China).

360 young fish (6.66 ± 0.08 g) were randomly assigned into 12 fiberglass tanks (0.5 m³), with 30 fish per tank, at the Marine Biological Research Base of Guangdong Ocean University (Zhanjiang, China) for feeding trial. Each diet was fed to three tanks, and the groupers were fed until they appeared satiated at 08:30 and 16:30 for 10 weeks, with water temperature maintained at 26-30°C and salinity at 27-30‰ throughout the trial. In compliance with the Experimental Animal Management Law of China, all animal experiments were approved by the Animal Ethics Committee of Guangdong Ocean University.

After the feeding trial, the groupers were starved for 24 hours. Prior to sampling, all groupers were anesthetized with a diluted eugenol solution (1:12000; Reagent, China), then counted and weighed. Blood was collected from the caudal vein and transferred to Eppendorf (EP) tubes. The samples were then centrifuged at 3500 rpm for 10 minutes, and the supernatant was collected as plasma. The plasma samples were stored at -80°C for subsequent biochemical analyses. Intestinal tissues from four groupers per tank were separated, frozen in liquid nitrogen, and transferred to a -80°C freezer for antioxidant parameter and other analyses. Two groupers were randomly selected from each tank, and their hindgut were collected for histological preparation. For each fish, two types of sections were prepared: one portion of the hindgut was fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde for transmission electron microscopy (TEM) analysis, while the other portion was fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining. This approach ensured that two distinct types of histological sections were obtained from each individual fish. Hindgut contents from eight fish per tank were randomly collected in collection tubes (with each tube containing contents from four fish), rapidly cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen, and kept at -80°C for intestinal microbiota profiling; and intestine tissues were collected in collection tubes, rapidly cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen, and kept at -80°C for enzyme activities and qPCR analysis.

On the basis of the recorded data, the indexes for the assessment of growth performance including WGR, DGC, SR, PER, and FCR were calculated as follows:

Tissue homogenate was prepared as described by Chen et al. (2024), the contents of total protein, malondialdehyde (MDA) and glutathione (GSH) as well as the activities of trypsin, lipase, amylase, creatine kinase, alkaline phosphatase (AKP), catalase, and superoxide dismutase (SOD) were determined by commercial kits (Nanjing Jiancheng, China; Cat# A045-2-2, A003-1-2, A006-2-1, C016-1-1, A054-2-1, A080-2-2, A059-2-2, A032-1-1, A007-1-1, A001-3-2) adhering to instructions. The plasma lipopolysaccharide (LPS), endothelin-1 (ET1) and D-lactic acid (D-LA) contents as well as glutathione peroxidase (GPX), diamine oxidase (DAO) activity, and intestinal mucoprotein 2 (MUC2), secretory immunoglobulin T (sIgT), immunoglobulin M (IgM), and polymeric immunoglobulin receptor (pIgR) levels, as well as lysozyme (LYS), histone deacetylase (HDAC), Na+/K+ ATPase, and Ca2+/Mg2+ ATPase activities were measured by commercial ELISA kits (Shanghai Enzyme-Link, China; Cat# YJ232256, YJ955101, YJ511201, YJ987714, YJ113425, YJ955010, YJ295636, YJ204791, YJ405356, YJ652391, YJ290715, YJ296520, YJ955010) following instructions.

Formalin-fixed intestinal tissue was paraffin-embedded and stained with H&E for microscopic observation (Nikon DS-U3, Japan). Villus height and width were measured from eight random villi, and muscularis thickness was measured at eight evenly distributed points on the intestinal cross-section, and then the average values were calculated. For ultrastructure, tissue was fixed in glutaraldehyde, post-fixed in osmium tetroxide, dehydrated, and embedded in resin. Sections were stained with uranyl acetate and lead citrate, and observed under a transmission electron microscope (Hitachi HT760, Japan).

Total RNA was extracted from intestinal tissue using a commercial kit (Vazyme, China), and its quality was assessed prior to reverse transcription to synthesize cDNA. The reverse transcription reaction was carried out under the following conditions: gDNA was removed by incubating the sample at 42°C for 2 minutes, followed by reverse transcription at 37°C for 15 minutes, and a final denaturation step at 85°C for 5 seconds. The resulting cDNA was used as the template for qPCR analysis on a Roche Light Cycler480 (Roche, Germany), using reagents from Takara (Japan). The qPCR reaction conditions were as follows: pre-denaturation at 95°C for 30 seconds, denaturation at 95°C for 10 seconds, and annealing/extension at 60°C for 30 seconds, repeated for 40 cycles. The melting curve analysis included an initial denaturation at 95°C for 5 minutes, followed by incubation at 60°C for 1 minute. The temperature was then gradually increased to 95°C, with fluorescence signals recorded at 1°C increments.

The primer sequences for each target gene and the reference gene (β-actin) are listed in Table 2.

Microbiota DNA was isolated using a commercial kit (Magen, China), and subjected to quality testing using agarose gels and purity testing with a UV spectrophotometer (Nanodrop 2000; ThermoFisher, USA). The DNA samples were amplified using the primer pair (Forward/Reverse: AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG/GGTTACCTTGTTACGACTT), and the amplification products were subsequently used for cDNA library construction. Sequencing was carried out on the HiSeq2500 PE250 platform (Illumina, Foster, CA, USA), and the resulting data were analyzed and visualized using the Novogene platform (Guangzhou, China). Subsequently, the data were annotated, analyzed for microbial diversity, and subjected to functional prediction using Tax4Fun. The Tax4Fun functional prediction is based on a nearest-neighbor method using the minimum 16S rRNA sequence similarity. This approach involves extracting prokaryotic full-genome 16S rRNA sequences from the KEGG database and aligning them to the SILVA SSU Ref NR database using the BLASTN algorithm to establish a related matrix. Functional annotations of the KEGG database prokaryotic genomes, derived from UProC and PAUDA methods, are then mapped onto the SILVA database for functional annotation. The sequencing samples are clustered into OTUs using the SILVA database sequences as reference, enabling the subsequent functional annotation of the microbiota.

The content and composition of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) in the digesta were determined using a method described by Chen et al. (2024). Briefly, 50 mg of digesta was mixed with a buffer solution concluding 50 μL of 15% phosphate buffer, 100 μL of isocaproic acid, and 400 μL of ether. The mixture was centrifuged at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4°C and then supernatant was collected for GC-MS analysis.

Data are shown as means ± standard error (means ± SEM) and analyzed using one-way variance analysis (ANOVA) with SPSS 18, followed by Tukey’s multiple range test. P< 0.05 reveals a significant difference between the datasets. The P-values from the regression analysis were calculated between feed viscosity and the parameters.

After the 10-week feeding trials, the survival rate of grouper ranged from 86.67% to 100%, with no significant differences among the dietary groups (P > 0.05; Figure 1). The final body weight, weight gain, daily growth coefficient, and protein efficiency ratio in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets were significantly lower than those in the control group (P< 0.05); however, the feed conversion ratio in these groups was significantly higher than that in the control group (P< 0.05). Moreover, the grouper in the GGH group exhibited a significantly lower protein efficiency than those in the GGL and GGM groups (P< 0.05), while its feed conversion ratio was significantly higher than that of the GGL and GGM groups (P< 0.05).

Figure 1. Growth performance and feed utilization of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity. FBW, final body weight; WGR, weight gain rate; DGC, daily growth coefficient; SR, survival rate; PER, protein efficiency ratio; FCR, feed conversion ratio. C, control diet; GGL, low-viscosity guar gum diet; GGM, middle-viscosity guar gum diet; GGH, high-viscosity guar gum diet. Values in vertical bars are presented as the means ± SE (n = 3), with different letters indicated significant difference (P< 0.05). The P-values from the regression analysis were calculated between feed viscosity and the parameters. The same as below.

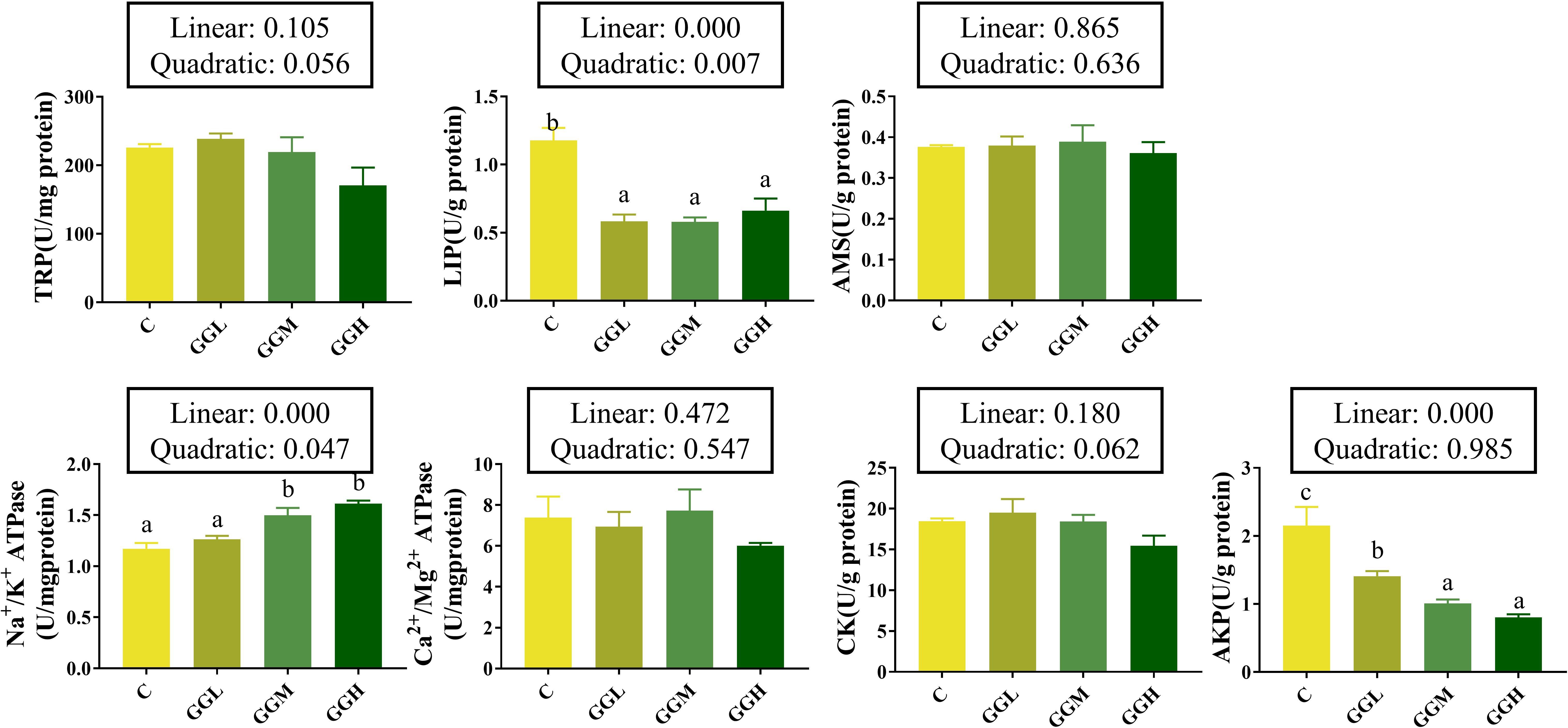

The intestinal lipase and AKP activities in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets were significantly lower than those in the control group (P< 0.05; Figure 2), while no significant differences were observed in trypsin, amylase, Ca²+/Mg²+ ATPase, or creatine kinase activities (P > 0.05). Na+/K+ ATPase activity was significantly higher in the GGM and GGH groups than that in the group (P< 0.05); however, AKP activity in the GGM and GGH groups was significantly lower than that in the GGL groups (P< 0.05).

Figure 2. Intestinal digestive and absorptive enzymes activities of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity. TRP, trypsin; AMS, amylase; LIP, lipase; CK, creatine kinase; AKP, alkline phosphatase.

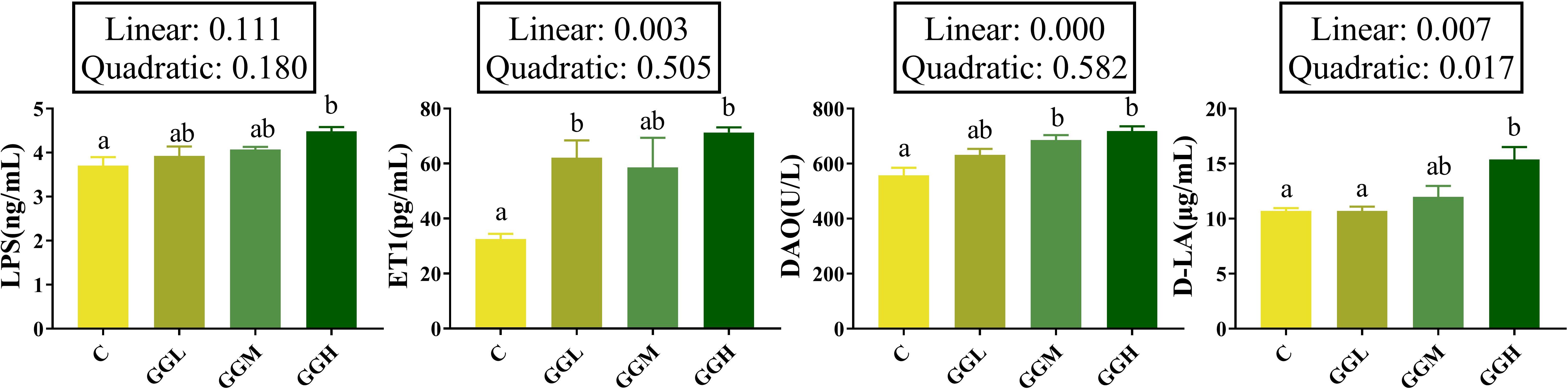

The plasma LPS and D-LA levels in the GGH group were significantly higher than those in the control group (P< 0.05; Figure 3) and the DAO activity in both the GGM and GGH groups was significantly higher than that in the control group (P< 0.05). Furthermore, plasma ET1 level in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets were significantly higher than that in the control group, with the highest levels observed in the GGH group (P< 0.05).

Figure 3. Intestinal mucosal barrier function-related indicators of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity. LPS, lipopolysaccharide; ET1, endothelin-1; DAO, diamine oxidase; D-LA, D-lactic acid.

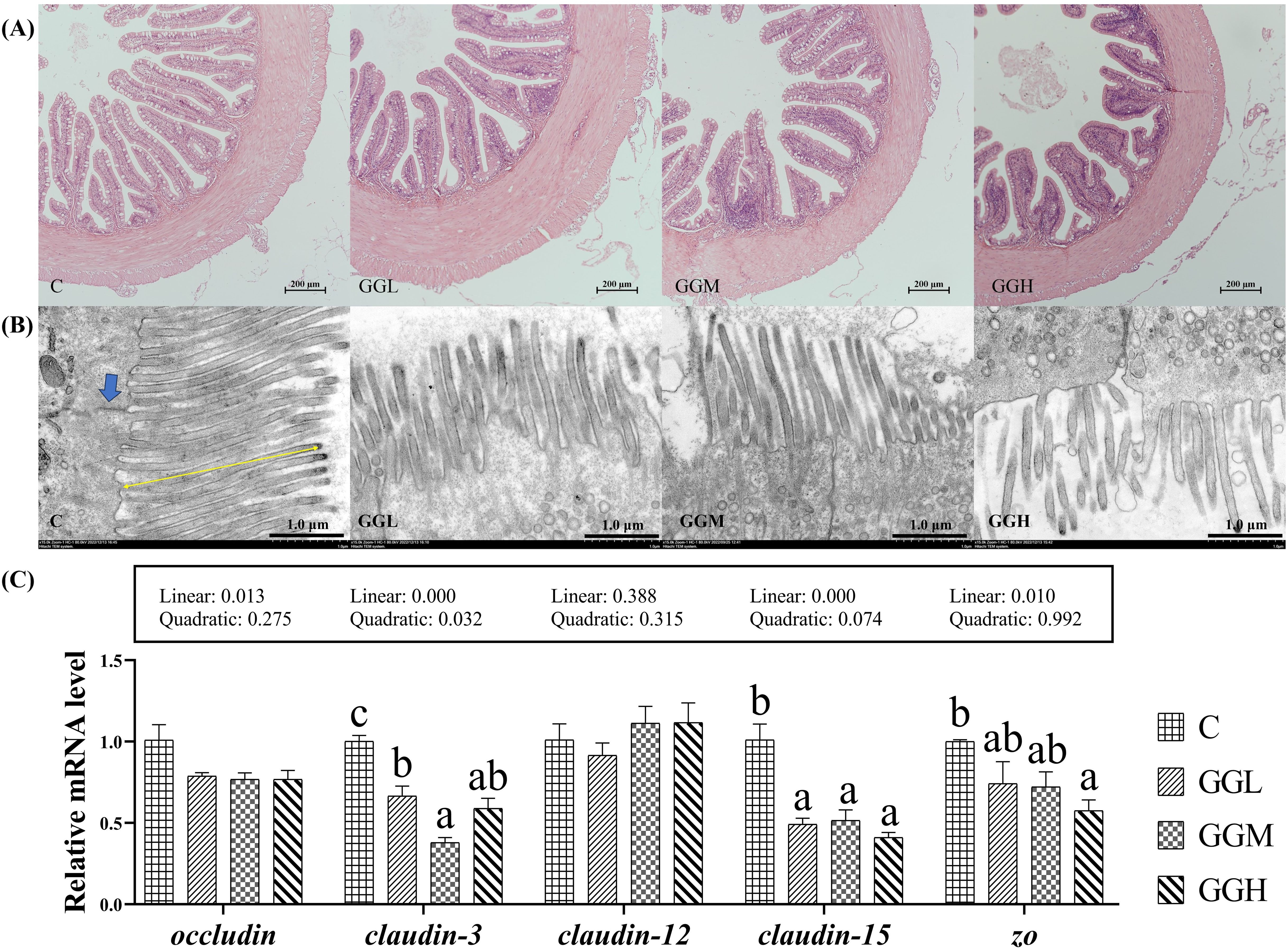

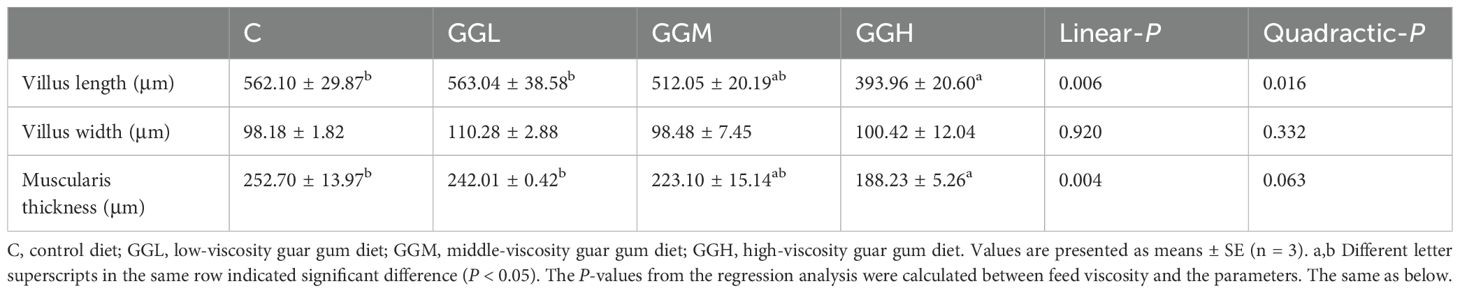

H&E staining (Figure 4A) revealed the inclusion of 8% GG with different viscosity caused intestinal structure alternations. Specifically, compared to the control group, the GGH group exhibited significantly increased intestinal villus length and muscularis thickness (P< 0.05; Table 3) while no significant difference was observed in villus width (P > 0.05). In addition, TEM analysis revealed that the inclusion of 8% GG with different viscosity led to disorganized arrangement of microvilli and damage to tight junctions in the intestinal cells, with the most prominent effects showed in the GGH group (Figure 4B). The intestinal relative expression levels of claudin-3 and claudin-15 in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets were significantly lower than those in the control group (P< 0.05; Figure 4C). Moreover, the level of zonula occludens (zo) in the GGH group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P< 0.05). No significant differences were observed in the relative expression levels of intestinal occludin among the dietary treatments (P > 0.05).

Figure 4. Intestinal mucosal physical barrier of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity. (A) Proximal intestine morphology (H&E; 100×); (B) Ultrastructure of distal intestinal epithelium (TEM; 5000×): Blue arrow: tight junctions; Yellow arrow: microvilli; (C) Relative mRNA expression levels of distal intestinal physical barrier-related genes.

Table 3. Morphology of the distal intestine of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity.

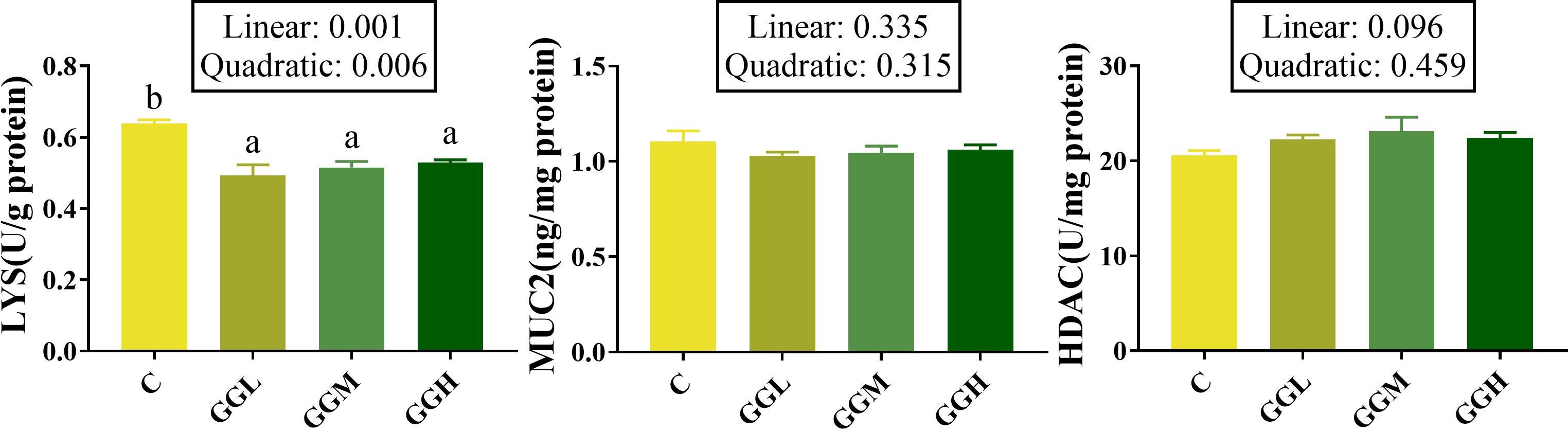

The intestinal LYS activity in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets was significantly lower than that in the control group (P< 0.05; Figure 5), while no significant differences were observed in the levels of MUC2 and HDAC compared to the control group (P > 0.05).

Figure 5. Intestinal mucosal chemical barrier-related indicators of pearl gentian grouper fed containing guar gum with varying viscosity. HDAC, histone deacetylase; LYS, lysozyme; MUC2, mucoprotein 2.

The intestinal IgM level in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets was significantly higher than that in the control group, and that in the GGH group was significantly higher than the GGL and GGM groups (P< 0.05; Figure 6). The sIgT level in the GGH group was significantly higher than that in the control group (P< 0.05); the pIgR level the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets had no significant difference compare to that in the control group (P > 0.05) but that in GGH group was significantly higher than GGL group (P< 0.05).

Figure 6. Intestinal humoral immune effector molecules-related indicators in distal intestine of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity. IgM, immunoglobulin M; sIgT, secretory immunoglobulin T; pIgR, polymeric immunoglobulin receptor.

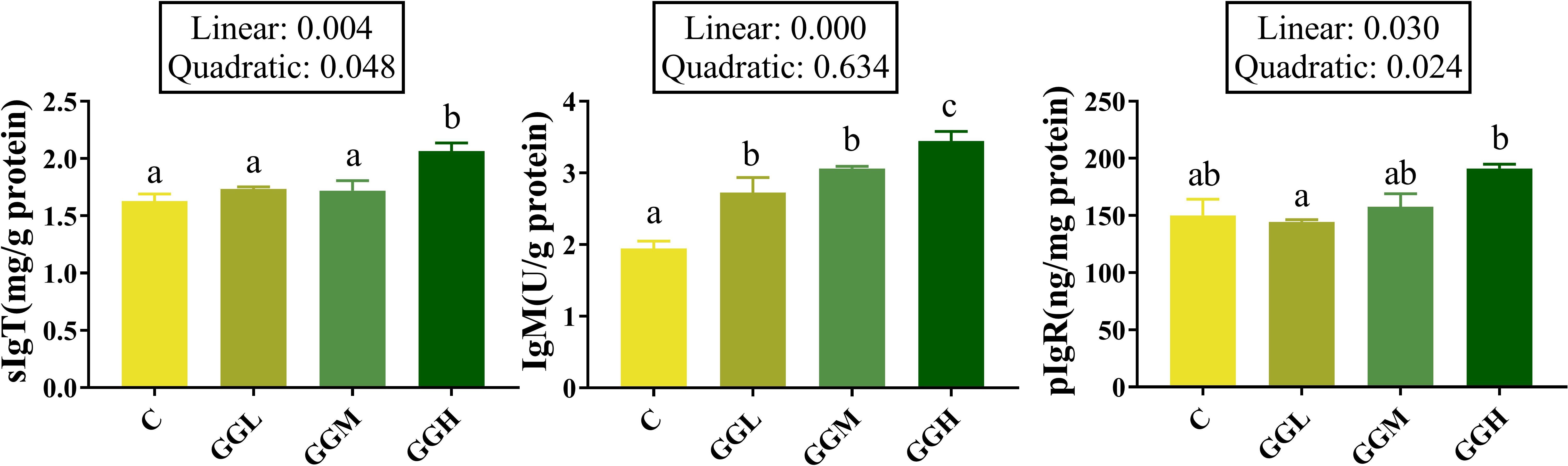

The expression levels of il-8 and il-10 in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets had no significant difference compare to those in the control group (P > 0.05; Figure 7), but the expression level of il-1β in GGH group were significantly higher than that in the control group (P< 0.05). The expression levels of tnf-α and il-6 in GGM and GGH groups were significantly higher than those in the control groups; the il-6 expression level in the GGH group significantly higher than that in the GGM group (P< 0.05). However, the expression level of tgf-β in GGL and GGH group were significantly higher than that in the control group (P< 0.05).

Figure 7. Relative mRNA expression levels of intestinal pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines in pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity.

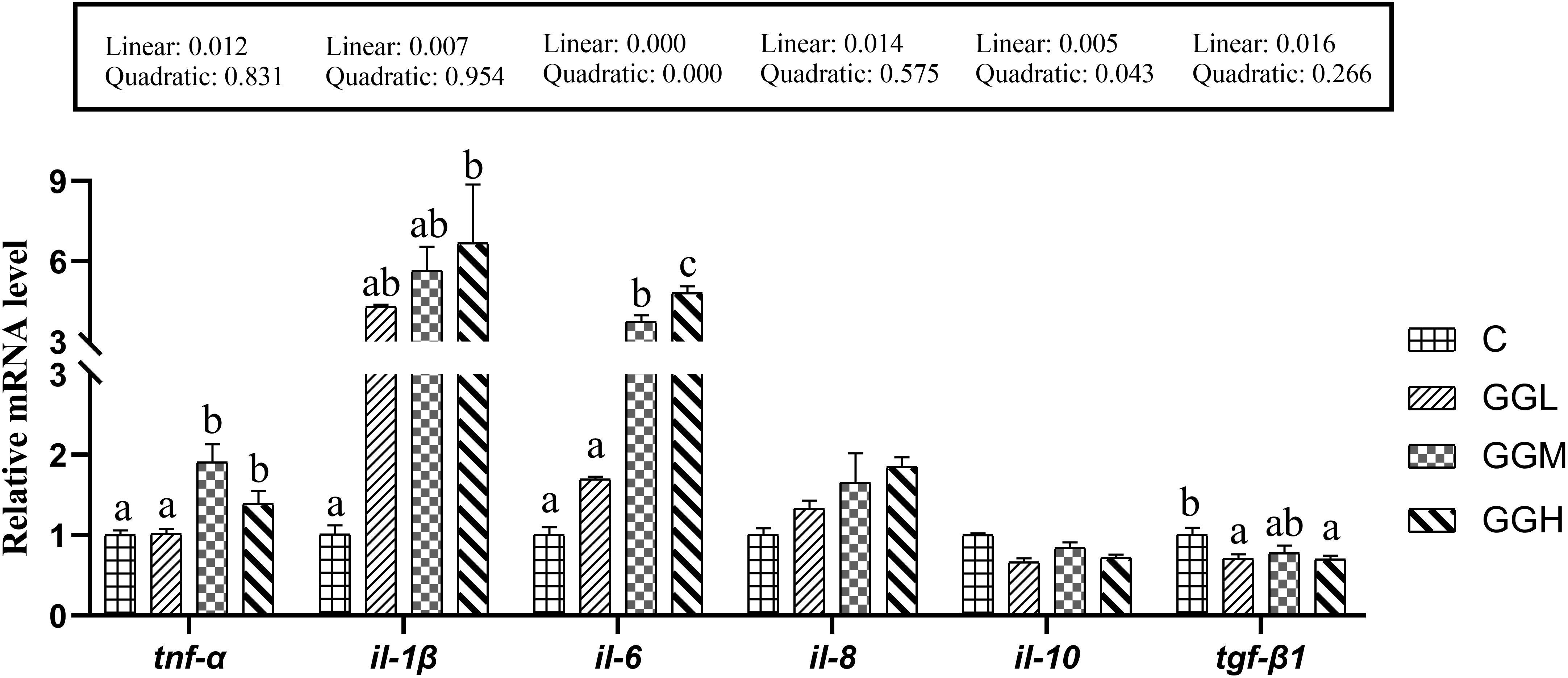

Dietary inclusion of 8% GG with different viscosity on The intestinal CAT activity in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets had no significant difference compared to that in the control group (P > 0.05; Figure 8). The MDA content in the GGH group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P< 0.05). However, the T-AOC level in the GGM and GGH groups were significantly higher than that in the control group (P< 0.05), and the GSH contents in the GGL and GGH groups were significantly higher than that in the control group (P< 0.05). Additionally, the GPX and SOD activities in the GGH group were significantly lower than that in the control group (P< 0.05).

Figure 8. Antioxidant function in distal intestine of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity. T-AOC, total antioxidant capacity; GPX, glutathione peroxidase; GSH, glutathione; SOD, superoxide dismutase; MDA, malondialdehyde.

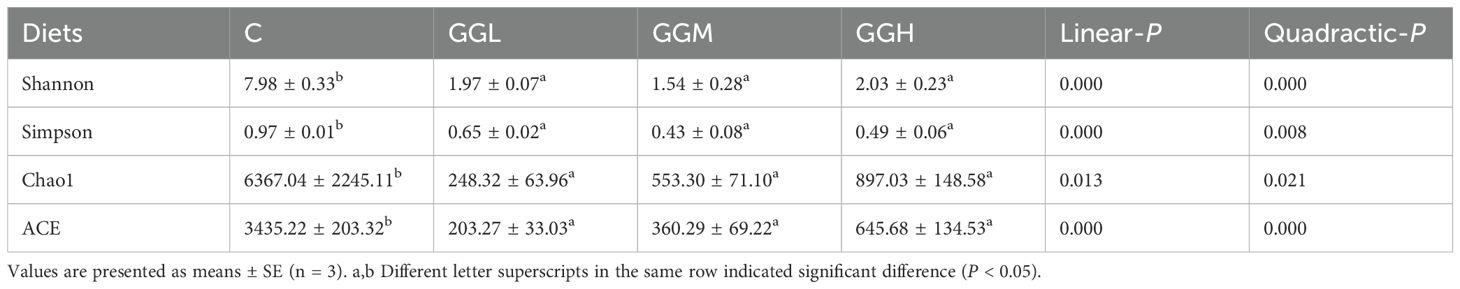

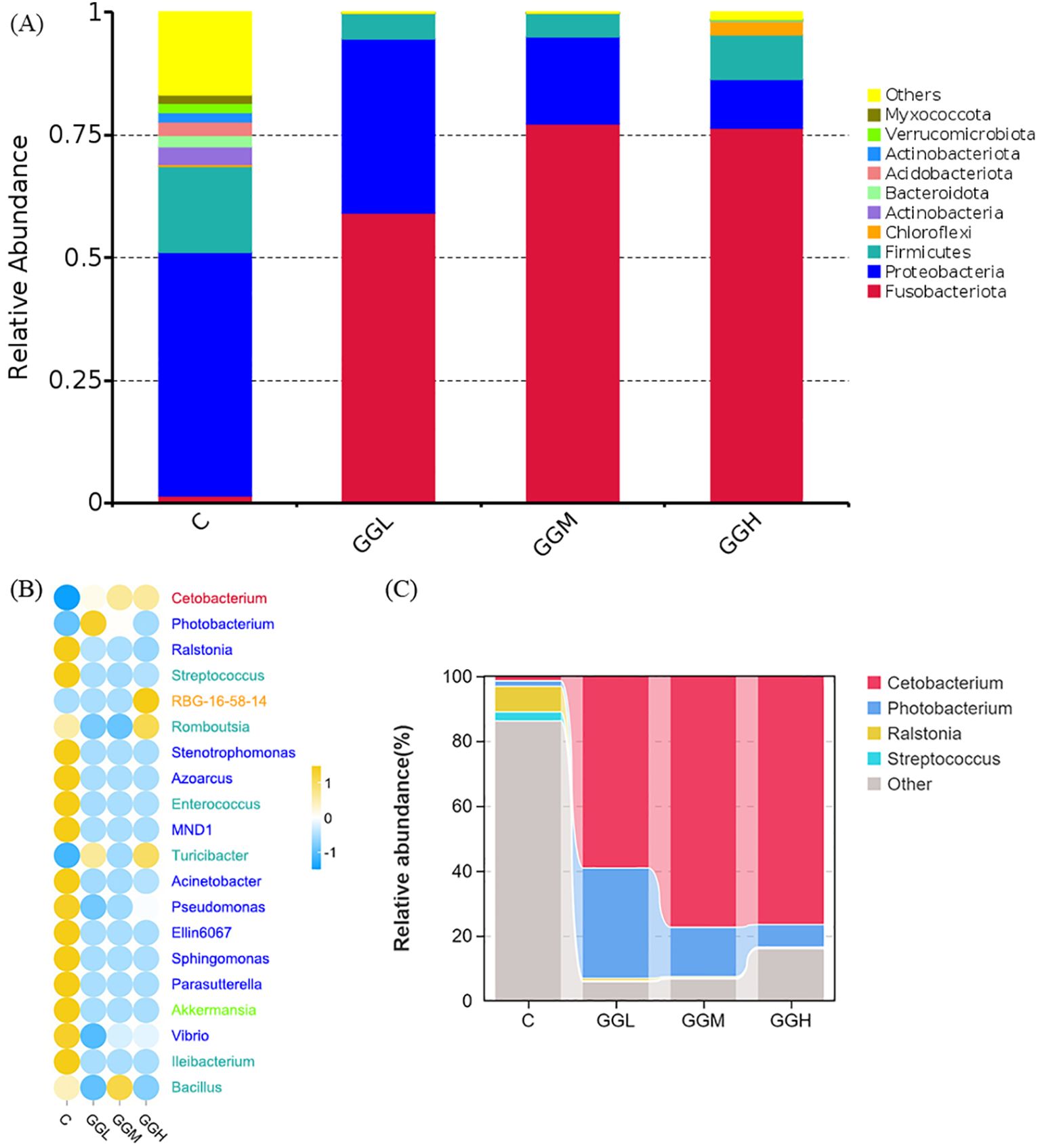

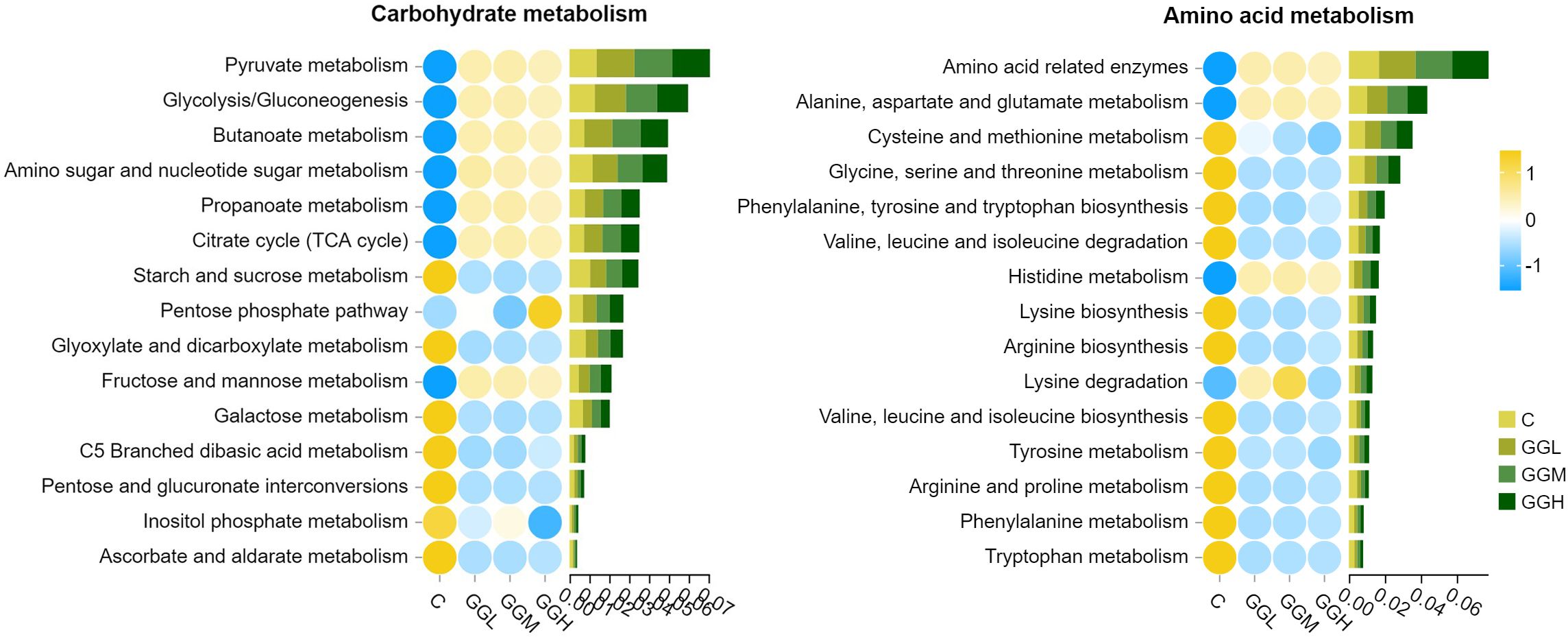

The ACE, Chao 1, Simpson, and Shannon indices of intestinal bacteria in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets was significantly lower than those in the control group (P< 0.05; Table 4). Shown as Figure 9A, the intestinal flora in hybrid grouper was primarily predominated by Fusobacteriota, Proteobacteria and Firmicutes. The changes in the top 20 genera are shown in Figure 9B, with Cetobacterium accounting for more than 59% of the relative abundance, and together with Photobacterium, they make up over 83% of the total abundance (Figure 9C). The results of Tax4Fun functional prediction on carbohydrate and amino acid metabolism are shown in Figure 10.

Table 4. Alpha diversity index of distal intestinal flora of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity.

Figure 9. Analysis of the intestinal microbiota composition of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity. The top 10 phylum-level composition (A), the top 10 genus-level difference (B) and the top 4 genus-level composition (C) are shown, respectively.

Figure 10. The predicted function (Level 3) in amino acid and carbohydrate metabolism of intestinal microbiota in pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity. The values on the x-axis represent the sum of the relative abundances annotated to the corresponding KEGG pathway.

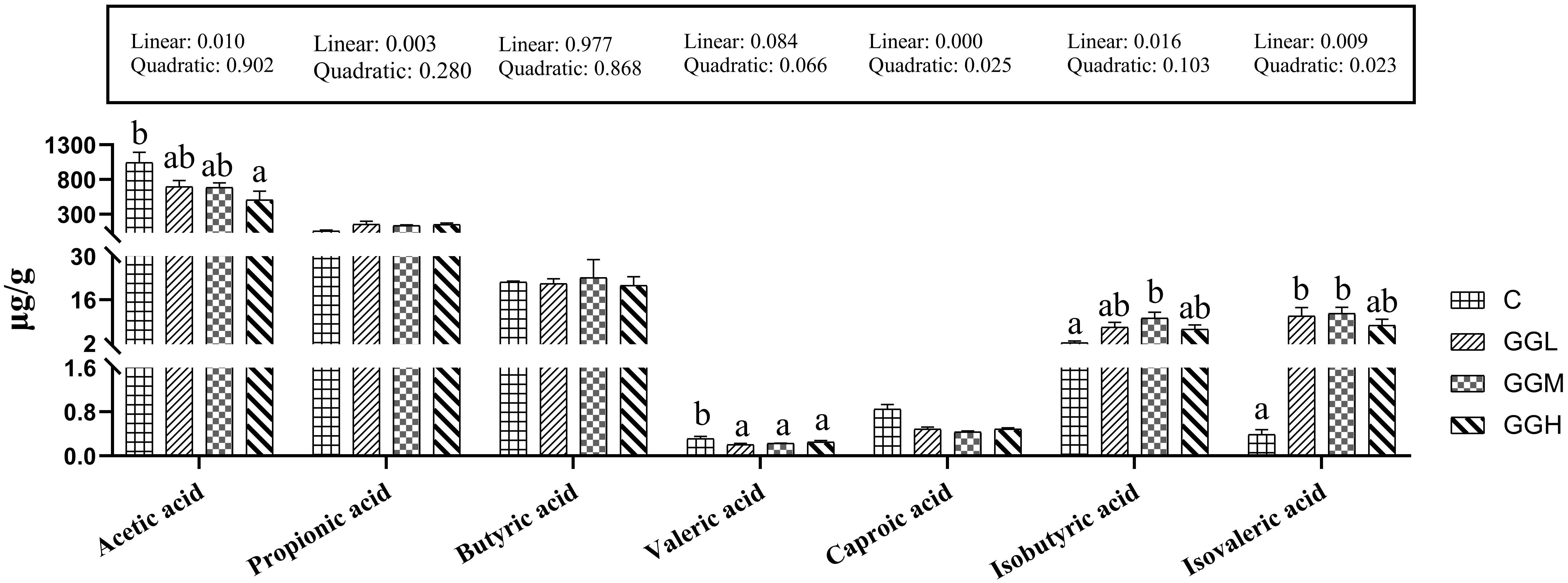

The valeric acid concentration of intestinal contents in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets was significantly lower than that in the control group (P< 0.05; Figure 11), but the propionic, butyric, and caproic acids concentrations in the groups fed different viscosities of GG diets had no significant difference compared to the those in the control group (P > 0.05). Moreover, the acetic acid concentration in the GGH group was significantly lower than that in the control group (P< 0.05). The isobutyric acid concentration in the GGM group was significantly lower than that in the control group, and the isovaleric acid concentration in GGL and GGM groups was significantly lower than that in the control group (P< 0.05).

Figure 11. Intestinal short-chain fatty acids of pearl gentian grouper fed diets containing guar gum with varying viscosity.

GG, a typical hemicellulose polysaccharide, possesses excellent thickening, stabilizing, and gelling properties, which render it widely applicable in the food and feed industries. Previous studies have demonstrated that dietary GG inclusion can inhibit growth performance in broiler chickens (1.7%), rats (10%) and pigs (7%), while also reducing nutrient digestibility and increasing the proportion of intestinal harmful bacteria (Poksay and Schneeman, 1983; Jha and Berrocoso, 2015; de Souza et al., 2023). In this study, dietary 8% GG significantly inhibited growth performance of grouper, and the inhibiting effect enhanced as the increase of viscosity of GG. Viscosity is a critical characteristic of GG, which escalates with higher inclusion levels in diet (Leenhouwers et al., 2006; Tu-Tran et al., 2020). A similar trend of growth reduction with increasing GG inclusion level has been observed in Pangasianodon hypophthalmus, Carassius gibelio, and Oncorhynchus mykiss (Storebakken, 1985; Gao et al., 2019; Tu-Tran et al., 2020). Conversely, low doses of GG have demonstrated growth-promoting effects in O. mykiss (2.5%) and Micropterus salmoides (0.3%) (Storebakken, 1985; Zhao et al., 2024). In terms of feed viscosity, the control group in this study had a viscosity of 2.1 mPa·s, whereas the viscosity in the guar gum supplementation groups increased from 188.7 mPa·s to 334.0 mPa·s. Growth in the supplementation groups was significantly lower than in the control group, but no significant differences were observed between the supplementation groups. In the Clarias gariepinus, the viscosity of the guar gum supplementation groups ranged from 16.9 mPa·s to 170.9 mPa·s, compared to 1.0 mPa·s in the control group, with no significant differences in growth. In the Oreochromis niloticus L. trial, the viscosity of the guar gum supplementation group was 42.9 mPa·s, compared to 0.9 mPa·s in the control group, and a significant decrease in growth was observed. Therefore, the varying effects of GG on growth performance are possibly due to its viscosity and the specific fish species involved.

In the present study, dietary GG significantly reduced the intestinal activities of lipase and AKP, which correlated with the observed decline in growth performance, consistent with findings in C. gibelio and M. salmoides (Gao et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2022c). Our experiment shows that an GG within the viscosity range of 188.7 mPa·s to 334.0 mPa·s did not significantly affect lipase activity in the intestines of grouper. However, at the feed viscosity of 273.8 mPa·s, a significant decrease in intestinal AKP enzyme activity was observed compared to the 188.7 mPa·s viscosity. The increase in feed viscosity, particularly beyond a certain threshold, likely leads to a higher viscosity of intestinal chyme, which could interfere with lipase-substrate interactions and potentially bind bile acids, thereby impairing fat emulsification and reducing lipase activity. Once the feed viscosity exceeds a specific threshold, further increases in viscosity may not result in a significant reduction in lipase activity. However, AKP activity appears to decrease continuously within the viscosity range of 188.7 to 273.8 mPa·s, suggesting that AKP activity has a different threshold for inhibition compared to lipase. AKP, involved in digestion and responsive to mechanical stimulation of intestinal cells (Chaturvedi et al., 2019), may be less stimulated due to slower chyme movement. This reduction in AKP secretion likely impairs nutrient absorption, contributing to inhibited growth. Thus, GG viscosity impacts both enzyme activity and digestive dynamics, ultimately reducing growth performance.

Intestinal morphology is pivotal for nutrient digestion and absorption, with the muscularis muscularis thickness closely tied to motility. In this study, increased GG viscosity correlated with reduced muscularis thickness, suggesting impairment of intestinal motility, which likely contributed to the decline in growth. The length of intestinal villi, which directly affects absorption, also decreased as GG viscosity increased, suggesting reduced absorptive capacity. Previous studies have shown that GG thickens the unstirred water layer near the intestinal mucosa, hindering absorption. This thickening, combined with decreased epithelial renewal, likely limits villus growth, further impairing nutrient absorption (Cerda et al., 1987; Jha and Berrocoso, 2015). Interestingly, in M. salmoides, GG addition improved both muscularis thickness and villus length (Liu et al., 2022d; Zhao et al., 2023), likely due to enhanced intestinal motility to process viscous chyme. In contrast, groupers appear to reduce motility, possibly to conserve energy in response to increased water retention from GG in the high-salinity marine environment. This could explain the increased Na+/K+ ATPase activity in the GGM and GGH groups, as marine fish require efficient ion regulation for water balance. Overall, the negative impact of GG viscosity on intestinal morphology and motility likely limits nutrient absorption and contributes to the observed growth inhibition.

The intestinal mucosal barrier is essential for protecting against pathogens. In our study, increased GG viscosity led to significant elevations in plasma markers of intestinal barrier damage (ET-1, D-LA, LPS, and DAO activity) in groupers, particularly in the GGH group. This indicates that higher GG viscosity impairs the intestinal barrier, which can limit nutrient absorption and increase vulnerability to pathogens. Similar effects have been observed in M. salmoides (Liu et al., 2022d). Disruption of the intestinal barrier, in turn, negatively impacts growth by compromising digestive efficiency and overall gut function. Thus, the viscosity of GG not only reduces nutrient absorption but also weakens intestinal defense, contributing to inhibited growth.

Claudins, zo, and occludin are key components of tight junctions in cells, essential for regulating intercellular permeability (Chen et al., 2024). The observed decrease in the relative mRNA expression of these genes in the dietary GG groups, especially with increasing GG viscosity, suggested a probable correlation with the disruption of tight junction function. This indicates that dietary GG, especially in its high-viscosity form (GGH), may compromise the integrity of intestinal mucosal barrier. These disruptions likely contribute to the observed growth inhibition, as the compromised barrier function hampers efficient digestion and nutrient uptake.

Lysozyme defends the intestinal mucosal barrier by enzymatically degrading bacterial cell walls, which prevents bacterial invasion and maintains gut homeostasis. In this study, the inclusion of 8% GG at three different viscosities significantly reduced intestinal lysozyme activity. Previous research also reported that dietary 8% GG increased the total bacterial count in the midgut and hindgut of mullet (Ramos et al., 2015). These findings suggest that dietary GG, especially at higher viscosities, may impair the intestinal barrier’s ability to defend against pathogens, potentially promoting gut dysbiosis. This disruption in intestinal health likely reduces nutrient absorption and increases the risk of inflammation, contributing to the observed growth inhibition. Thus, the viscosity of GG not only affects digestive function but also compromises gut immunity, further limiting growth potential.

Inflammatory responses are key to innate immunity, protecting against infections. In mice, dietary GG enhances the relative expression of il-6 and increase susceptibility to colonic inflammation (Paudel et al., 2024). In our study, dietary GG, particularly GGH, upregulated the pro-inflammatory cytokines (tnf-α, il-1β, and il-6) and downregulating the anti-inflammatory cytokine (tgf-β) in pearl gentian grouper. Similarly, the viscous enhancement resulting from higher inclusion levels of GG led to a reduction in pro-inflammatory cytokines in M. salmoides (Zhao et al., 2023). As GG viscosity increased, the inflammatory response intensified, indicating that higher viscosity could disrupt immune regulation in the gut. This inflammation may impair gut function, reduce nutrient absorption, and inhibit growth. Additionally, increased ROS levels and decreased antioxidant capacity (T-AOC, GPX, SOD, GSH) in GG-fed groupers, especially in the GGH group, highlighted oxidative stress in the intestine. Elevated MDA levels further supported this, indicating oxidative damage that could compromise cellular integrity. In response, the grouper increased intestinal IgM and sIgT levels, suggesting an enhanced immune response to oxidative stress and inflammation. However, the lack of significant changes in immunoglobulin transport via pIgR points to a more energy-efficient strategy of locally increasing immunoglobulin levels instead of enhancing systemic immune function. These immune system disruptions, alongside oxidative stress, likely impair nutrient absorption and contribute to the observed growth inhibition, as the energy spent on managing inflammation and oxidative damage diverts resources away from growth.

The intestinal microbiota is crucial for maintaining the function of intestinal barrier and influencing nutrient assimilation, immune defense, and epithelial cell differentiation (Piazzon et al., 2020; Wei et al., 2020). In present study, dietary GG supplementation at different viscosities reduced abundance decline of intestinal microbiota. A decline in α-diversity disrupts gut homeostasis, diminishing microbial richness and evenness, and making microbiota more susceptible to environmental stressor (Li et al., 2023). This imbalance can compromise intestinal function and nutrient absorption, ultimately impacting growth. In this study, the intestinal dominant phyla of grouper were Proteobacteria, Firmicutes, Actinobacteria and Bacteroidota, which was similar with previous study in grouper species (Li et al., 2022). Dietary GG at different viscosities reduced Firmicutes and increased Fusobacteriota, particularly Cetobacterium and Photobacterium. Cetobacterium, a beneficial bacterium, and Photobacterium, a pathogenic one, together accounted for over 83% of the microbial abundance, suggesting these genera respond to GG supplementation. GG also reduced the abundance of aerobic bacteria and may decrease oxygen levels in the gut, potentially limiting the growth of oxygen-demanding microbes. Functional analysis revealed GG altered microbial metabolism, upregulating pathways for simple carbohydrates and amino acids while downregulating those for complex carbohydrates. This shift in microbial preference may impact nutrient absorption and growth. The effects of GG viscosity on microbiota were similar across different viscosities, suggesting the overall impact of GG supplementation outweighs viscosity differences. In summary, GG’s impact on gut microbiota diversity, bacterial composition, and oxygen levels likely disrupts intestinal function, impairs nutrient absorption, and contributes to growth inhibition. These findings highlight that the viscosity of GG, in addition to altering microbial communities, may have broader implications for gut health and growth.

The observed increase in the relative abundance of Cetobacterium is significant, as this genus is known for its ability to produce SCFAs, which are essential energy sources for intestinal cells and play a crucial role in maintaining the structural and functional integrity of the intestine (Estensoro et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2022). However, dietary GG supplementation led to a reduction in intestinal SCFA levels, especially acetic acid, with the decline becoming more pronounced as GG viscosity increased. This contrasts with findings in M. salmoides, where GG was linked to increased SCFA levels (Liu et al., 2022d). We hypothesize that the higher viscosity of GG in grouper results in prolonged gastrointestinal transit time, reducing SCFA production by altering the gut’s oxygen environment. The slower transit may also facilitate more SCFA absorption, potentially impacting intestinal functionality. Similar gastrointestinal movements that affect gut bacteria and thus gut function have also been found in mice (Zhu et al., 2018). Furthermore, the reduction in hexanoic acid could reflect the accelerated absorption of acetic acid, inhibiting its further production. This suggests that GG may indirectly influence gut microbiota and intestinal physiology, possibly enhancing SCFA production to mitigate negative effects on intestinal function. Additionally, the observed increase in branched-chain SCFAs, such as isobutyrate and isovalerate, indicates a shift toward amino acid fermentation, which may reduce feed efficiency. A greater reliance on amino acid fermentation could lead to inefficient protein utilization, limiting growth.

In summary, dietary inclusion of 8% GG with three viscosities adversely impacted the growth performance and intestinal health of pearl gentian grouper, with these negative effects becoming more pronounced as the viscosity of GG increased.

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Animal Research and Ethics Committee of Guangdong Ocean University. The study was conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements.

LZ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Writing – original draft. SC: Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. SZ: Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. SX: Methodology, Project administration, Writing – review & editing. BT: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing – review & editing. JD: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32273152, 32330110), the Program for Scientific Research Start-up Funds of Guangdong Ocean University (060302022007) and the Special Project in Key Fields of Universities in Guangdong Province (2022ZDZX4013).

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declare that no Generative AI was used in the creation of this manuscript.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Adebowale T. O., Yao K., Oso A. O. (2019). Major cereal carbohydrates in relation to intestinal health of monogastric animals: A review. Anim. Nutr. 5, 331–339. doi: 10.1016/j.aninu.2019.09.001

Amirkolaie A. K., Leenhouwers J. I., Verreth J. A. J., Schrama J. W. (2005). Type of dietary fibre (soluble versus insoluble) influences digestion, faeces characteristics and faecal waste production in Nile tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus L.). Aquacult. Res. 36, 1157–1166. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2109.2005.01330.x

Brinker A. (2009). Improving the mechanical characteristics of faecal waste in rainbow trout: the influence of fish size and treatment with a non-starch polysaccharide (guar gum). Aquacult. Nutr. 15, 229–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2008.00587.x

Cerda J., Robbins F., Burgin C., Gerencser G. (1987). Unstirred water layers in rabbit intestine: effects of guar gum. J. Parenteral. Enteral. Nutr. 11, 63–66. doi: 10.1177/014860718701100163

Chaturvedi L. S., Wang Q., More S. K., Vomhof-DeKrey E. E., Basson M. D. (2019). Schlafen 12 mediates the effects of butyrate and repetitive mechanical deformation on intestinal epithelial differentiation in human Caco-2 intestinal epithelial cells. Hum. Cell 32, 240–250. doi: 10.1007/s13577-019-00247-3

Chen H., Wan X., He Q., Xiao G., Zheng Y., Luo M. (2024). Single-cell RNA sequencing reveals cellular dynamics and therapeutic effects of astragaloside IV in slow transit constipation. Biomol. Biomed. 24, 871–887. doi: 10.17305/bb.2024.10187

de Souza M., Eeckhaut V., Goossens E., Ducatelle R., Van Nieuwerburgh F., Poulsen K., et al. (2023). Guar gum as galactomannan source induces dysbiosis and reduces performance in broiler chickens and dietary β-mannanase restores the gut homeostasis. Poultry. Sci. 102, 102810. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2023.102810

Enes P., Pousão-Ferreira P., Salmerón C., Capilla E., Navarro I., Gutiérrez J. (2013). Effect of guar gum on glucose and lipid metabolism in white sea bream Diplodus sargus. Fish. Physiol. Biochem. 39, 159–169. doi: 10.1007/s10695-012-9687-0

Estensoro I., Ballester-Lozano G., Benedito-Palos L., Grammes F., Martos-Sitcha J. A., Mydland L.-T. (2016). Dietary butyrate helps to restore the intestinal status of a marine teleost (Sparus aurata) fed extreme diets low in fish meal and fish oil. PloS One 11, e0166564. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0166564

FAO (2022). The State of World Fisheries and Aquaculture 2022: Towards Blue Transformation (Rome: Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). Available at: https://www.fao.org/documents/card/en/c/cc0461en (Accessed December 11, 2024).

Fu X., Li R., Zhang T., Li M., Mou H. (2019). Study on the ability of partially hydrolyzed guar gum to modulate the gut microbiota and relieve constipation. J. Food Biochem. 43, e12715. doi: 10.1111/jfbc.12715

Gao S., Han D., Zhu X., Yang Y., Liu H., Xie S. (2019). Effects of guar gum on the growth performance and intestinal histology of gibel carp (Carassius gibelio). Aquaculture 501, 90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2018.11.009

Gee J. M., Blackburn N. A., Johnson I. T. (1983). The influence of guar gum on intestinal cholesterol transport in the rat. Br. J. Nutr. 50, 215–224. doi: 10.1079/BJN19830091

Jang K. B., Kim Y. I., Duarte M. E., Kim S. W. (2024). Effects of β-mannanase supplementation on intestinal health and growth of nursery pigs. J. Anim. Sci. 102, skae052. doi: 10.1093/jas/skae052

Jha R., Berrocoso J. D. (2015). Review: Dietary fiber utilization and its effects on physiological functions and gut health of swine. Animal 9, 1441–1452. doi: 10.1017/S1751731115000919

Leenhouwers J. I., Adjei-Boateng D., Verreth J. A. J., Schrama J. (2006). Digesta viscosity, nutrient digestibility and organ weights in African catfish (Clarias gariepinus) fed diets supplemented with different levels of a soluble non-starch polysaccharide. Aquacult. Nutr. 12, 111–116. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2095.2006.00389.x

Li Z., Zeng Q., Hu S., Liu Z., Wang S., Jin Y., et al. (2023b). Chaihu Shugan San ameliorated cognitive deficits through regulating gut microbiota in senescence-accelerated mouse prone 8. Front. Pharmacol. 14. doi: 10.3389/fphar.2023.1181226

Li X., Zhu D., Mao M., Wu J., Yang Q., Tan B., et al. (2022). Glycerol monolaurate alleviates oxidative stress and intestinal flora imbalance caused by salinity changes for juvenile grouper. Metabolites 12, 1268. doi: 10.3390/metabo12121268

Liu Y., Fan J., Zhou H., Zhang Y., Huang H., Cao Y., et al. (2022b). Feeding juvenile largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides) with carboxymethyl cellulose with different viscous: Impacts on nutrient digestibility, growth, and hepatic and gut morphology. Front. Mar. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1023872

Liu Y., Huang H., Fan J., Zhou H., Zhang Y., Cao Y., et al. (2022a). Effects of dietary non-starch polysaccharides level on the growth, intestinal flora and intestinal health of juvenile largemouth bass Micropterus salmoides. Aquaculture 557, 738343. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.738343

Liu H., Xie R., Huang W., Yang Y., Zhou M., Lu B., et al. (2024). Effects of Dietary Aflatoxin B1 on Hybrid Grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus ♀ × Epinephelus lanceolatus ♂) Growth, Intestinal Health, and Muscle Quality. Aquacult. Nutr. 2024, 3920254. doi: 10.1155/2024/3920254

Liu Y., Zhang Y., Fan J., Zhou H., Huang H., Cao Y., et al. (2022c). Effects of different viscous guar gums on growth, apparent nutrient digestibility, intestinal development and morphology in juvenile largemouth bass, Micropterus salmoides. Front. Physiol. 13. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2022.927819

Liu Y., Zhou H., Fan J., Huang H., Deng J., Tan B. (2022d). Assessing effects of guar gum viscosity on the growth, intestinal flora, and intestinal health of Micropterus salmoides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 222, 1037–1047. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2022.09.220

Long W., Luo J., Ou H., Jiang W., Zhou H., Liu Y., et al. (2023). Effects of dietary citrus pulp level on the growth and intestinal health of largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). J. Sci. Food Agric. 104, 2728–2743. doi: 10.1002/jsfa.13157

Owusu-Asiedu A., Patience J. F., Laarveld B., Van Kessel A. G., Simmins P. H., Zijlstra R. T. (2006). Effects of guar gum and cellulose on digesta passage rate, ileal microbial populations, energy and protein digestibility, and performance of grower pigs1,2. J. Anim. Sci. 84, 843–852. doi: 10.2527/2006.844843x

Paudel D., Nair D. V. T., Tian S., Hao F., Goand U. K., Joseph G., et al. (2024). Dietary fiber guar gum-induced shift in gut microbiota metabolism and intestinal immune activity enhances susceptibility to colonic inflammation. Gut. Microbes 16, 2341457. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2024.2341457

Perera W. N. U., Abdollahi M. R., Zaefarian F., Wester T. J., Ravindran V. (2022). Barley, an undervalued cereal for poultry diets: limitations and opportunities. Animals 12, 2525. doi: 10.3390/ani12192525

Piazzon M. C., Naya-Català F., Perera E., Palenzuela O., Sitjà-Bobadilla A., Pérez-Sánchez J. (2020). Genetic selection for growth drives differences in intestinal microbiota composition and parasite disease resistance in gilthead sea bream. Microbiome 8, 168. doi: 10.1186/s40168-020-00922-w

Poksay K. S., Schneeman B. O. (1983). Pancreatic and intestinal response to dietary guar gum in rats. J. Nutr. 113, 1544–1549. doi: 10.1093/jn/113.8.1544

Rajoka M. S., Thirumdas R., Mehwish H. M., Umair M., Khurshid M., Hayat H. F., et al. (2021). Role of food antioxidants in modulating gut microbial communities: novel understandings in intestinal oxidative stress damage and their impact on host health. Antioxidants 10, 1563. doi: 10.3390/antiox10101563

Ramos L. R. V., Romano L. A., Monserrat J. M., Abreu P. C., Verde P. E. (2015). Biological responses in mullet Mugil liza juveniles fed with guar gum supplemented diets. Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 205, 98–106. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2015.04.004

Storebakken T. (1985). Binders in fish feeds. Aquaculture 47, 11–26. doi: 10.1016/0044-8486(85)90004-3

Su C., Fan D., Pan L., Lu Y., Wang Y., Zhang M. (2020). Effects of Yu-Ping-Feng polysaccharides (YPS) on the immune response, intestinal microbiota, disease resistance and growth performance of Litopenaeus vannamei. Fish. Shellfish. Immunol. 105, 104–116. doi: 10.1016/j.fsi.2020.07.003

Tahmouzi S., Meftahizadeh H., Eyshi S., Mahmoudzadeh A., Alizadeh B., Mollakhalili-Meybodi N., et al. (2023). Application of guar (Cyamopsis tetragonoloba L.) gum in food technologies: A review of properties and mechanisms of action. Food Sci. Nutr. 11, 4869–4897. doi: 10.1002/fsn3.3383

Tu-Tran L. C., Nguyen T., Verreth J. A. J., Schrama J. W. (2020). Doses response of dietary viscosity on digestibility and faecal characteristics of striped catfish (Pangasionodon hypophthalmus). Aquacult. Res. 51, 595–604. doi: 10.1111/are.14406

Wang S., He L., Guo J., Zhao J., Tang H. (2015). Intrinsic viscosity and rheological properties of natural and substituted guar gums in seawater. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 76, 262–268. doi: 10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2015.03.002

Wang S., Li X., Liu P., Li J., Liu L. (2022). The relationship between Alzheimer’s disease and intestinal microflora structure and inflammatory factors. Front. Aging Neurosci. 14. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2022.972982

Wei Q., Qi L., Lin H., Liu D., Zhu X., Dai Y., et al. (2020). Pathological mechanisms in diabetes of the exocrine pancreas: What’s known and what’s to know. Front. Physiol. 11. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.570276

White D., Adhikari R., Wang J., Chen C., Lee J. H., Kim W. K. (2021). Effects of dietary protein, energy and β-mannanase on laying performance, egg quality, and ileal amino acid digestibility in laying hens. Poultry. Sci. 100, 101312. doi: 10.1016/j.psj.2021.101312

Yu F., Liu Y., Wang W., Yang S., Gao Y., Shi W., et al. (2024). Toxicity of TPhP on the gills and intestines of zebrafish from the perspectives of histopathology, oxidative stress and immune response. Sci. Total. Environ. 908, 168212. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2023.168212

Zhao X., Chen W., Tian E., Zhang Y., Huang Y., Ren H., et al. (2023). Effects of guar gum supplementation in high-fat diets on fish growth, gut histology, intestinal oxidative stress, inflammation, and apoptosis in juvenile largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Israeli J. Aquacul. Bamidgeh 9, 1–13. doi: 10.46989/001c.777976

Zhao X., Chen W., Zhang Y., Gao X., Huang Y., Ren H., et al. (2024). Dietary guar gum supplementation reduces the adverse effects of high-fat diets on the growth performance, antioxidant capacity, inflammation, and apoptosis of juvenile largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides). Anim. Feed. Sci. Technol. 308, 115881. doi: 10.1016/j.anifeedsci.2024.115881

Keywords: guar gum, viscosity, pearl gentian grouper, growth performance, intestinal health

Citation: Zhu L, Chi S, Zhang S, Xie S, Tan B and Deng J (2025) Effects of dietary guar gum with different viscosity on growth performance and intestinal health in pearl gentian grouper (Epinephelus fuscoguttatus♀ × E. lanceolatus♂). Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1549055. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1549055

Received: 20 December 2024; Accepted: 24 February 2025;

Published: 25 March 2025.

Edited by:

Xianyong Bu, Ocean University of China, ChinaReviewed by:

Min Jin, Ningbo University, ChinaCopyright © 2025 Zhu, Chi, Zhang, Xie, Tan and Deng. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Junming Deng, ZGp1bm1pbmdAMTYzLmNvbQ==

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.