94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

ORIGINAL RESEARCH article

Front. Mar. Sci., 21 March 2025

Sec. Global Change and the Future Ocean

Volume 12 - 2025 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2025.1454260

Plankton tow net samples collected during the HMS Challenger expedition (1872–1876) have highlighted the potential to provide an unique window into past oceanic conditions. This study aims to assess the suitability of HMS Challenger sediment samples as indicators of late 19th century surface oceanic conditions using X-ray micro-computed tomography (μCT). We used μCT to examine all 21 available Challenger samples from the global ocean that were labelled as ‘tow-net at dredge’, ‘weights’, or ‘trawl’. Our analysis reveals that most samples contain benthic foraminifera shells, along with high concentrations of foraminiferal fragments and detrital quartz grains, while the remaining samples consist of sedimentary material devoid of calcareous microfossils. These findings suggest that these tow-net samples include resuspended bottom sediments rather than exclusively surface-derived material. This distinction is critical because it demonstrates that two types of Challenger tow-net samples exist: surface ocean samples and deep-water tow-net samples that incorporate seafloor material. The surface tow-net samples were recently located and are referenced in this study. These findings highlight the importance of re-evaluating historical sediment collections with modern analytical techniques to ensure accurate paleoceanographic interpretations. Furthermore, the study demonstrates the effectiveness of μCT as a non-destructive tool for sediment analysis, allowing for the detailed examination of collections without the need for washing or wet sieving.

The HMS Challenger Expedition was a pioneering research cruise that took place from 1872 to 1876 and laid much of the foundation of modern oceanographic knowledge. The voyage covered over 68,000 NM (126,000 km) across all the world’s oceans, with an array of scientific observations made at 362 stations (Linklater, 1972). These included physical measures of temperature and circulation; chemical measures of dissolved acids; and animal, plant and sediment samples taken at all depths. Predominant focus was “devoted to deep-sea research” (Tizard et al., 1885), and much time was committed to collecting and observing samples from the ocean bottom by dredging and trawling. However, a conscious effort was made to collect surface and intermediate-depth pelagic samples for comparison with benthic samples, to determine how the nature of the plankton and nekton influenced the composition of the bottom sediment.

While of lesser importance to the Challenger Expedition, the physicochemical characteristics of the hard-bodied plankton collected at surface and intermediate depths could provide an insight into the physical and chemical nature of the water column during the years 1872-76. While this period post-dates the First Industrial Revolution (1760-1840), it marks the onset of the Second Industrial Revolution (1870-1914) (Landes, 2003) and predates ‘The Great Acceleration’ of the 1950s (Steffen et al., 2015). This would represent a useful benchmark for comparing contemporary samples, in which any change in biomineralisation intensity may relate to changes in stratification and nutrient supply, or ocean acidification, under the action of increased anthropogenic CO2 emissions and ocean change.

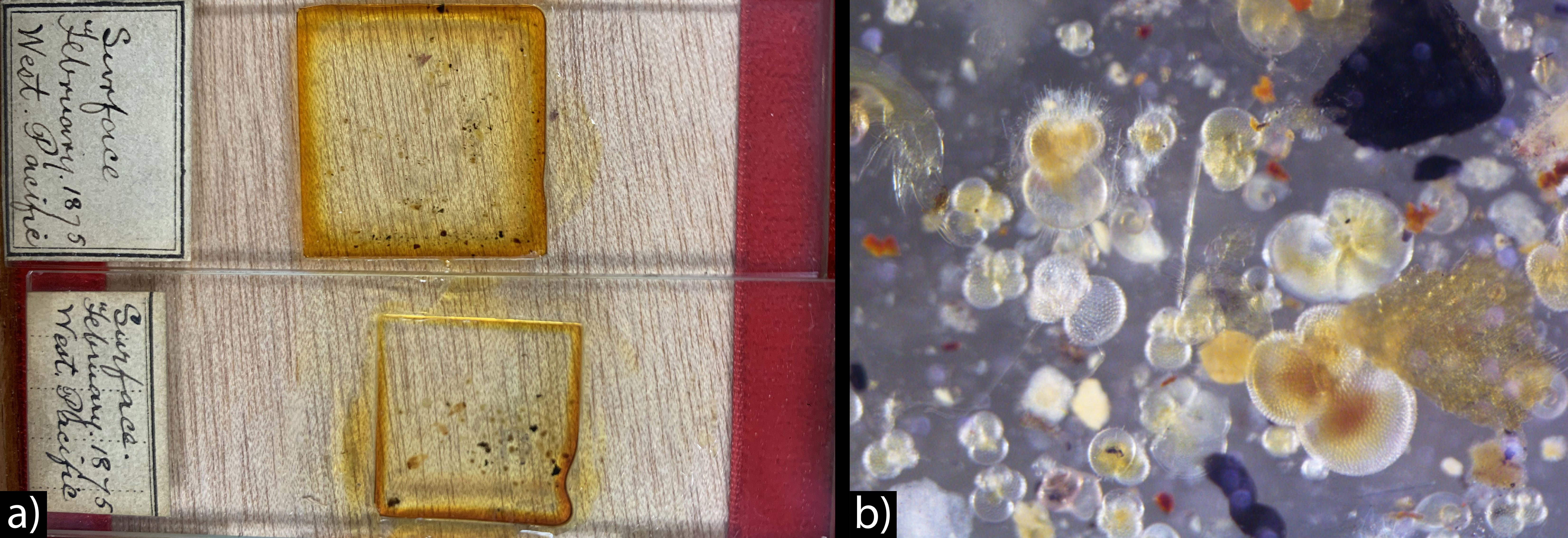

The Natural History Museum London, houses many of the natural history specimens collected as part of the Challenger Expedition, including John Murray’s sediment samples, which are now the nucleus of the Ocean Bottom Deposit (OBD) Collection at the Natural History Museum. Other collections at the museum include preparations of plankton from shallower water settings, in the form of diatom preparations or Canada Balsam slides made on the ship, to illustrate the micro and meso plankton collected in tow nets at depths of less than 100 m (Figure 1). However, the present study focuses on sediments collected during dredging and trawling that make up part of the OBD. The Murray Challenger collection contains sediment from the ocean bottoms that has previously been assessed by Rillo et al. (2019). They compared the foraminiferal content of these bottom sediments with foraminiferal datasets for the Holocene and Last Glacial Maximum and suggested that some, but not all, of these samples can be used to benchmark the state of the oceans in the 1870s and that there may be older foraminiferal specimens mixed with some of these sediments.

Figure 1. Photographs of (a) the original glass slides containing ocean surface plankton collected during the HMS Challenger Expedition (1872 - 1876) with plankton nets and fixed with Canada Balsam and (b) 60x magnification of the material fixed on the glass slides.

To counteract the possibility that the samples represent older benthic material, Fox et al. (2020) used samples labelled as ‘tow net at trawl’ or ‘tow net at dredge’ from the OBD Collection from HMS Challenger stations 272 and 299 (Figure 2). These were compared with modern samples collected during the Tara Oceans expeditions (Pesant et al., 2015) to assess the calcification of foraminifera. The present authors further analyzed these two HMS Challenger samples for planktonic foraminiferal shell weight. Following initial washing and coarse fraction sieving, some benthic foraminifera were found in both of these samples, potentially compromising their representation of ocean conditions in the 1870s. However, as certain species of benthic foraminifera have been identified within modern plankton (Kucera et al., 2017), these benthic occurrences in the HMS Challenger samples required further investigation.

This work outlines an X-ray micro-computed tomographic (μCT) method for assessing these sediments for benthic tracers by scanning all 21 of the samples marked as ‘tow net at trawl’, ‘tow net’, ‘tow net at dredge’ or ‘tow net at weights’ and one sample marked as ‘surface diatoms’ from John Murray’s Challenger Collection within the Natural History Museum’s OBD Collection. By using μCT to systematically analyze these historical samples, this study provides critical insights into their composition and clarifies the nature of any benthic material present. This is essential for correctly interpreting legacy oceanographic collections and ensuring their appropriate use in paleoceanographic reconstructions. Additionally, we identified Challenger surface (tow-net) glass slide samples can provide an improved framework for future historical oceanographic assessments. Similar materials could potentially be identified in other oceanographic slide collections.

The material examined in this investigation is housed in the Natural History Museum’s Ocean Bottom Deposits Collection and consists of sedimentary residues from 22 sampling stations (Figure 2). The sediments are housed in sealed glass jars that have original sample labels as well as additional labels depicting the ‘Murray Collection’ (M) number and other collection details. The ocean bottom deposits of the HMS Challenger expedition were chiefly managed by Sir John Murray, who catalogued the collection. The M numbers were later introduced by the British Museum, Natural History (BMNH) as part of their archival system and are distinct from the original Challenger sounding station numbers. Additionally, the new labels contained the Challenger sounding station number, a brief sample description, date, latitude and longitude, and the depth at which the sample was collected in fathoms. Photographs of some of the original containers are provided in Supplementary Figure 1. Initially, sample aliquots (~40 g) from Stations 272 and 299 used in the study of Fox et al. (2020) were washed and the coarse fraction (>63μm) was visually examined under a light stereoscope. Qualitative observations revealed the presence of both calcareous-walled and agglutinated benthic foraminifera forms in the samples. At Station 272, our visual assessment indicated a predominance of the calcareous genera Cassidulina, Bulimina, and Oridorsalis, along with the agglutinated genus Portatrochammina. At Station 299, specimens of the genus Uvigerina were predominant, with a single specimen of Pyrgo and agglutinated specimens from the genus Reophax observed. These observations are presented as qualitative descriptions rather than as quantitative abundance measurements. After the observation of benthic particles in both samples, the investigation was subsequently extended to the rest of the collection using non-destructive X-ray micro-computed tomography (μCT).

From the complete set of 20 wooden cabinets containing original Challenger sediments, 22 samples were identified (Table 1). All samples with labels that included the words ‘tow-net’, ‘townet’ or ‘tow net’ (hyphenated, compound, or spaced forms) were chosen and aliquoted for μCT analysis. This set includes 8 samples from the Atlantic, 13 from the Pacific, and one from the Indian Ocean. For simplicity, in the figures, we grouped the samples from the Indian and Pacific Oceans into a single Indo-Pacific category. All the sample containers were original and had been air-sealed with cork and adhesive wrap. 14 samples were contained within green, transparent glass ‘rock bottles’ 23 cm in height and 15 cm in diameter (Tizard et al., 1885); six samples were contained within white glass jars 9 cm in height and 5 cm in diameter; and two samples were contained in glass test tubes. One of the glass tubes (Sample 1; Table 1) was labelled ‘Surface net – Diatoms’ and its appearance was different to the rest. Most of the analyzed samples exhibited large volumes of loose sediment (see Supplementary Figure 1) or consolidated clumps, whereas Sample 1 was much lower volume and exhibited a whitish, felt-like appearance. Sample 1 was CT scanned but also examined under the light stereoscope.

The μCT analyses were carried out at the Imaging and Analysis Centre, Natural History Museum, London, using a Nikon Metrology HMX ST 225 system (Nikon Metrology, Tring, UK). This system is equipped with a 4-megapixel detector panel (2000 × 2000 pixels) with a maximum resolution (voxel size) of 5 μm, a maximum energy of 225 kV for the reflection target, and a maximum current output of 2000 μA. The sediment samples were aliquoted into 50 ml self-standing polypropylene centrifuge tubes. The samples were scanned in batches of 5 after being transferred into a straight-sided polypropene jar to secure the samples from moving. The scanning took place at a voltage of 120 kV and a 200 µA current. Specific scanning parameters are detailed in each accompanying data file. The duration of each acquisition lasted approximately an hour and the scanning resolution varied between the different batches from ~30 to 40 μm. The projections acquired during the scanning process were subsequently reconstructed using the software CT Pro (Nikon Metrology, Tring, UK), which employs a modified version of the Feldkamp et al. (1984) back-projection algorithm. This generated a stack of grayscale TIFF slice images, which were then imported into the Avizo 2019 software for visualization and analysis. In Avizo, the image stack for each sample was visually examined for its contents.

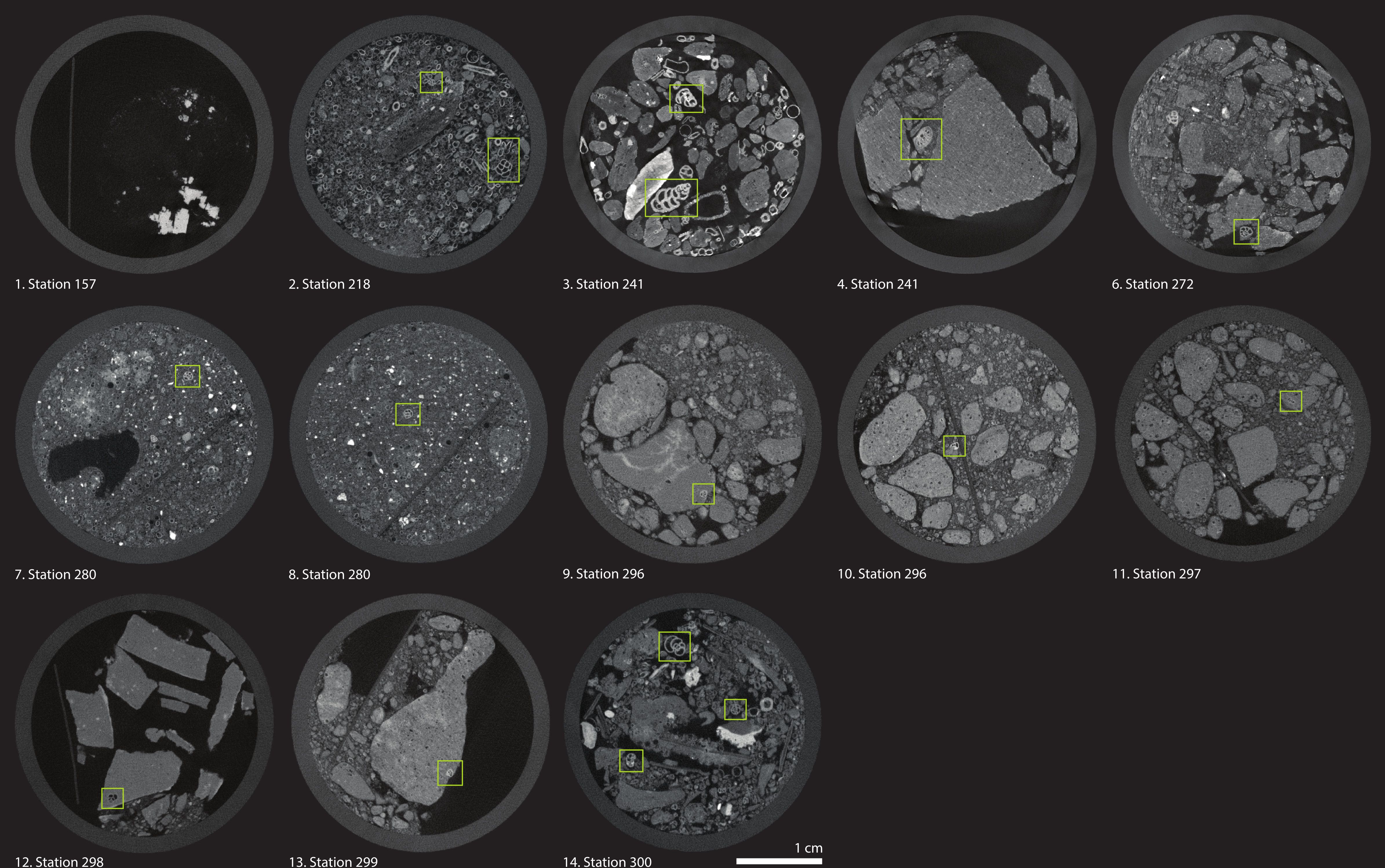

Characteristic snapshots that document the existence of benthic particles in each sample were cropped from the produced image stacks and compiled in the figures below. Figure 3 summarizes the tomographs of the Indo-Pacific samples. Sample 1 (Station 157) from the ‘Surface net’ from the southeast Indian Ocean appears as distinct dense, bright chunks and no benthic material was observed. The examination of this sample under the microscope confirmed that it consisted only of densely packed, fibrous diatomaceous remnants. The observed bright chunks might represent such dense aggregations of diatom silica, but individual diatoms could not be discerned. In contrast, the other samples from the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans that contained carbonate material consistently revealed the presence of benthic foraminiferal shells during the scanning analysis. At least 46 benthic foraminifera, gastropod, or coral specimens were identified across all the remaining 21 samples. Sample 5 (Station 253) contained no carbonate material due to its collection below the carbonate compensation depth, where carbonate preservation is not possible (Burton, 1998). In Sample 4 (Station 241) a coral fragment was also observed. The samples contained numerous fragmented foraminiferal shells and quartz grains. Sample 12 (Station 298) exhibited stronger consolidation and broke into chunks during sampling. In contrast, Sample 3 (Station 241), labelled as ‘washings’, lacked a matrix of very fine material and showed an increased concentration of benthic foraminiferal shells and fragments. According to (Murray, 1891) ‘washings’ refers to when “the ooze or clay was passed through sieves of various sizes” such that “all the larger particles from these sieves were then carefully collected and placed in bottles with spirit, and labelled ‘coarse’ and ‘fine washings’”, and likely explains why these tests and fragments were concentrated. This washing is related specifically to dredged or trawled material.

Figure 3. Tomographs of HMS Challenger tow net at trawl, dredge and weights samples from the Indo-Pacific Oceans. The yellow frames highlight characteristic sections of benthic foraminiferal shells in all samples and a coral fragment in sample 4 (Station 241). For exact description of sampling, see Table 1. Sample 5 (Station 253) is not shown due to lack of carbonate material. A close-up view of the specimens highlighted in the yellow frames is provided in Supplementary Figure 2.

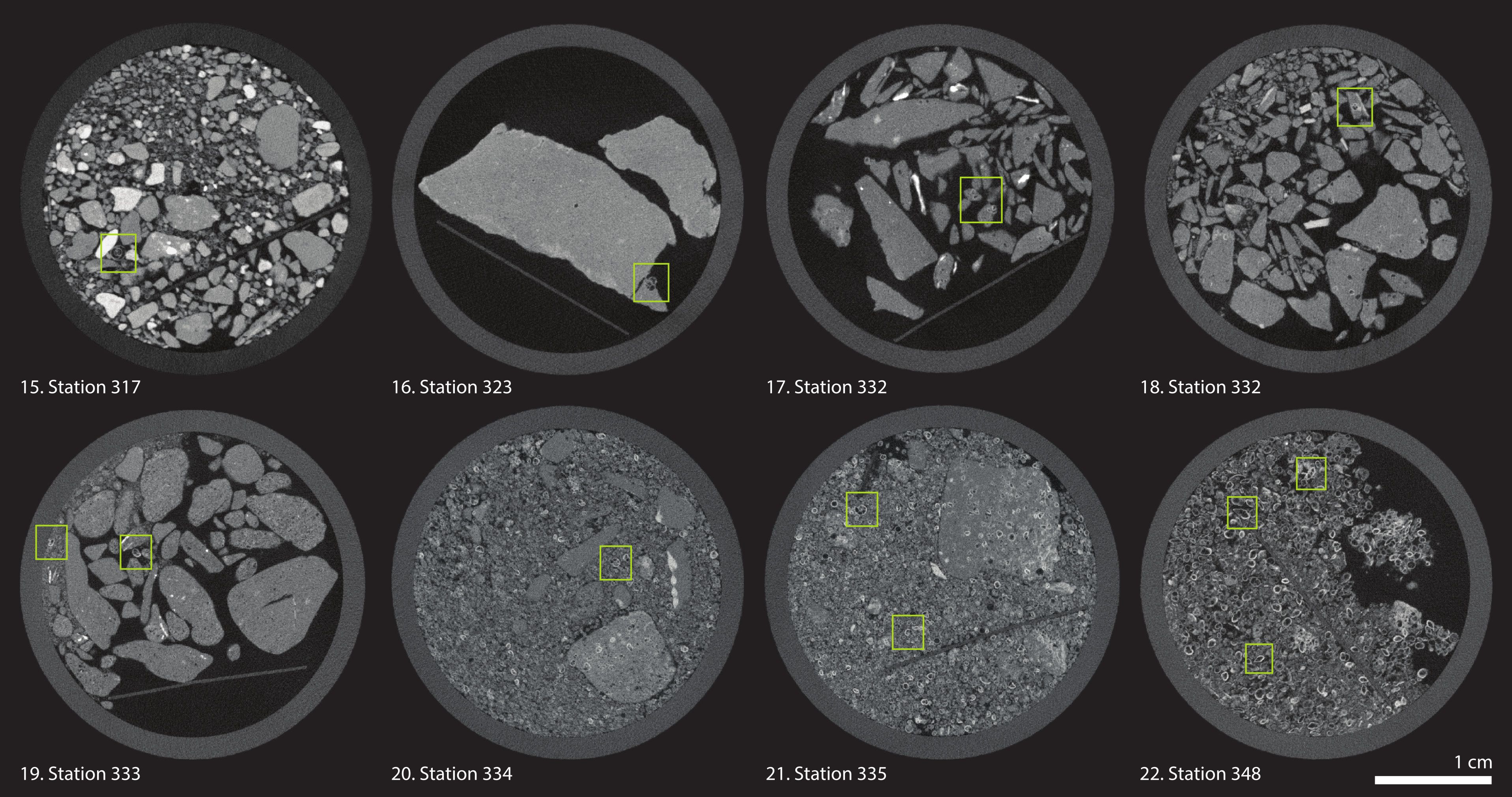

Atlantic samples (Figure 4) also appeared to contain many fragmented foraminifera shells and quartz grains. Most of the samples consisted of a mixture of agglomerates in a matrix of loosely consolidated material. Sample 16 consisted of larger agglomerates and samples 16 to 19 of medium agglomerates, while having only a small number of foraminiferal shells. The rest of the samples were mostly loose material rich in complete and fragmented foraminiferal shells, especially sample 22 from Station 348.

Figure 4. Tomographs of HMS Challenger tow net at trawl, dredge and weights samples from the Atlantic Ocean. The yellow frames highlight some characteristic sections of benthic foraminifera shells in all the samples. For further description of sampling, see Table 1. A close-up view of the specimens highlighted in the yellow frames is provided in Supplementary Figure 3.

Of all the studied samples housed in the OBD collection, only the ‘Surface net’ sample was found to consist of purely pelagic material. It was expected that the samples taken by ‘tow nets’ on the expedition should contain purely pelagic material, to be analyzed as a direct representation of the chemical and physical character of the water column on the given dates of sampling. The archival investigation into the written narrative and scientific reports of the expedition (Brady, 1884; Tizard et al., 1885; Murray, 1891) that was performed for the present study suggests that the term ‘tow net’ in isolation is ambiguous and was used in markedly different applications. Thus, it represents differing sampling techniques, not all of which were likely to collect purely pelagic material.

The Narrative of the cruise (Tizard et al., 1885) mentions that the pelagic foraminifera were “under almost daily observation during the cruise”. Furthermore, the collection of pelagic foraminifera is explicitly noted several times, with species and genus information given in nine of these instances (see Supplementary Table 1). Foraminiferal specimens from surface net samples were mounted on glass slides and are kept in the ‘Heron-Allen’ Library of the British Museum of Natural History (now: Natural History Museum, London) (Jones, 1994). A summary of the archival review key points is given in Supplementary Table 1.

‘Surface nets’ were “continually in use throughout the cruise” (Tizard et al., 1885) and were deployed predominantly to depths shallower than 100 fathoms (182.9 m). These nets consisted of a coarse cloth net that was held open by an iron hoop up to 18 inches (45.7 cm) in diameter (Figure 5d). During the expedition, the ‘dredge’ was an iron framework up to five feet (1.52 m) in length that held open a fine cloth bag to be dragged along the seafloor (Figure 5a). While the dredge remained in use throughout the voyage, it was complemented by the introduction of a wooden ‘beam-trawl’ (Tizard et al., 1885), which employed a wooden beam up to 17 feet (5.18 m) in length, attached to a V-shaped bag and weighted with lead to keep the net on the seafloor during trawling (Figure 5b).

Figure 5. Drawings showing the sampling equipment used on the HMS Challenger Expedition. (a) the ‘dredge’; (b) the ‘beam-trawl’; (c) the trawl after use, with a ‘tow net’ attached to the beam (yellow rectangle), notably close to the contact point of the trawl with the seafloor; (d) the ‘surface tow net’; (e) the ‘weights’ system used to ensure the trawl remained in contact with the seafloor. A tow net was attached to the weights which made contact with the seafloor at the red rectangle (Tizard et al., 1885).

Murray (1891) explained that the “ordinary surface tow-net was frequently attached to the beam of the trawl and iron frame of the dredge” (Figure 5c); we suggest this sampling method explains the sample labels ‘tow net at trawl’ (studied samples 2, 7, 9–12, 14, 16, 17, and 19–21) and ‘tow net at dredge’ (samples 5 and 22), as well as other similar wordings associating the ‘tow net’ with the ‘dredge’ or ‘trawl’. It is likely that this sampling method would not produce purely pelagic material, as these ‘tow nets’ were in such proximity to the benthic pedoturbation under the action of the ‘dredge’ or the ‘trawl’. Murray (1891) further explained that “a tow-net was in like manner sometimes fixed to the weights that were placed on the trawling line” (Figure 5e) which “occasionally came up filled with mud or ooze”. We suggest this defines the sample label ‘tow-net at weights’ (sample 15), and Murray’s second point implies that this material is also unlikely to be purely pelagic.

The visual examination of the coarse fraction of the aliquots of samples 6 (Station 272) and 13 (Station 299) indicated the existence of many foraminiferal shell fragments and quartz grains indicative of seafloor conditions. Furthermore, the volume of material in the identified samples with ‘tow net’ present on the labels, contained especially in the rock bottles, was likely too large to be considered a representation of pelagic plankton tows, and thus must be supplemented with bottom sediment. The only pelagic sample of high confidence analyzed in this study, sample 1 (Station 157; labelled ‘surface net’), was contained within a glass test tube and its material occupied a volume of less than a few cubic centimeters (Supplementary Figure 1). This is a dramatic contrast to other ‘tow net’ samples that sometimes occupied multiple 23 cm tall rock bottles. All these observations, along with the presence of seafloor material such as benthic shells or coral fragments (Figures 3, 4) revealed by μCT scanning, suggest that the studied samples may have contained resuspended sedimentary material from the seafloor. While these characteristics indicate general benthic contamination due to the sampling process, the tomographs could not differentiate between specific sampling techniques listed on the labels. Additionally, the species of benthic fauna, the volume of material, and the sizes of terrigenous grains varied even among samples collected using the same technique (e.g., sample 17, “Mud from townet at trawl,” and sample 20, “From net at trawl”).

It should be noted that some benthic foraminifera of the Bolivinitinae lineage have both a benthic and a pelagic lifestyle (Kucera et al., 2017), so their presence in these sediments does not necessarily indicate contamination of planktonic nets by benthic material. However, not all observed benthic foraminifera specimens in the tomographs resembled Bolivinitinae. Given the relatively coarse scanning resolution (~30 to 40 μm) used in this study, precise species identification of foraminifera was not possible. While our current resolution was insufficient for species-level identification, it was sufficient to distinguish between planktonic and benthic foraminifera. Planktonic foraminifera typically exhibit an evolute coiling pattern, giving them a more globular and spherical appearance, whereas benthic foraminifera can have both evolute and involute shell structures, as well as biserial, triserial, or other arrangements. Additionally, planktonic foraminifera tend to have thinner, more delicate walls, as they inhabit the surface layers of the ocean (Zarkogiannis et al., 2022), whereas benthic species often have thicker and more robust tests suited for life on or within the seafloor sediment (Davis et al., 2016). The method outlined here is crucial to further assessment of these sediments so that the foraminifera could be identified from each of the samples and interpretations made on the ecological niches of the benthic foraminifera and biota that they contain.

Our findings confirm that HMS Challenger samples labelled as tow-net at weights, dredge and trawl contain resuspended benthic material, demonstrating that these samples do not exclusively represent surface ocean conditions. This distinction fundamentally changes how these historical samples should be interpreted in palaeoceanographic research. We suggest that HMS Challenger tow-net surface slides present in the Micropalaeontology Collections at the Natural History Museum (Figure 1) and collected from the top 100 fathoms (182.9 m) of the water column, have potential to provide a more accurate historical baseline for oceanic conditions in the 1870s.

Beyond clarifying the nature of these samples, this study highlights the effectiveness of μCT as a non-destructive tool for analyzing legacy sediment collections. By providing a methodology that avoids destructive processing techniques, μCT allows for the reassessment of historical samples while preserving them for future research. These findings underscore the need for careful re-evaluation of historical datasets to ensure their accurate application in oceanographic reconstructions.

X-ray micro-computed tomography scanning has proven to be an efficient, non-destructive method for analyzing sedimentary collections with minimal disturbance. All 21 samples labelled as ‘tow net at dredge’, ‘trawl’, or ‘weights’ from the Murray Challenger Collection within the Ocean Bottom Deposits Collection at the Natural History Museum were found to contain varying concentrations of benthic foraminifera and some coral fragments. The dredge and trawl sampling methods used during the HMS Challenger expedition likely introduced resuspended sedimentary particles into the plankton tow nets, along with the planktonic material. The μCT scans enable further analysis of these benthic particles to determine if the species present may also be planktonic. Glass slides prepared on board Challenger from plankton tow-net material collected from the top 100 meters of the water column may contain foraminifera that serve as better physicochemical surface ocean indicators. These glass slides might offer a more accurate representation of the state of the ocean in the 1870s.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found in the article/Supplementary Material. The X-ray micro-tomographic datasets generated and analysed for this study can be found in the NHM Data Portal https://doi.org/10.5519/xuspw960.

SZ: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing – original draft, Funding acquisition, Methodology, Visualization. TW: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing – original draft. CM: Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Resources, Writing – review & editing. SS: Resources, Validation, Writing – review & editing. BC: Data curation, Resources, Writing – review & editing.

The author(s) declare that financial support was received for the research and/or publication of this article. This research was supported by UK Research and Innovation Grant (SODIOM) EP/Y004221/1.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2025.1454260/full#supplementary-material

Brady H. B. (1884). “Report on the Foraminifera,” in Report of the Scientific Results of the Voyage of the H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873-76 (H.M. Stationary Office, London).

Burton E. A. (1998). “Carbonate carbonatescompensation depthcompensation depth,” in Geochemistry (Springer Netherlands, Dordrecht), 73–73.

Davis C. V., Myhre S. E., Hill T. M. (2016). Benthic foraminiferal shell weight: Deglacial species-specific responses from the Santa Barbara Basin. Mar. Micropaleontol. 124, 45–53. doi: 10.1016/j.marmicro.2016.02.002

Feldkamp L. A., Davis L. C., Kress J. W. (1984). Practical cone-beam algorithm. J. Optical. Soc. America A. 1, 612–619. doi: 10.1364/JOSAA.1.000612

Fox L., Stukins S., Hill T., Miller C. G. (2020). Quantifying the effect of anthropogenic climate change on calcifying plankton. Sci. Rep. 10, 1620. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-58501-w

Kucera M., Silye L., Weiner A. K. M., Darling K., Lübben B., Holzmann M., et al. (2017). Caught in the act: anatomy of an ongoing benthic–planktonic transition in a marine protist. J. Plankton. Res. 39, 436–449. doi: 10.1093/plankt/fbx018

Landes D. S. (2003). The Unbound Prometheus: Technological Change and Industrial Development in Western Europe from 1750 to the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press).

Murray J. (1891). “Report on the deep-sea deposits,” in Report of the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873-76 (H.M. Stationary Office, London).

Pesant S., Not F., Picheral M., Kandels-Lewis S., Le Bescot N., Gorsky G., et al. (2015). Open science resources for the discovery and analysis of Tara Oceans data. Sci. Data 2, 150023. doi: 10.1038/sdata.2015.23

Rillo M. C., Kucera M., Ezard T. H. G., Miller C. G. (2019). Surface sediment samples from early age of seafloor exploration can provide a late 19th century baseline of the marine environment. Front. Mar. Sci. 5. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2018.00517

Steffen W., Broadgate W., Deutsch L., Gaffney O., Ludwig C. (2015). The trajectory of the anthropocene: the great acceleration . Anthropocene. Rev. 2, 81–98. doi: 10.1177/2053019614564785

Tizard T. H., Moseley H. N., Buchanan J. Y., Murray J. (1885). “Narrative of the cruise of H.M.S. Challenger with a general account of the scientific results of the expedition,” in Report of the Scientific Results of the Voyage of H.M.S. Challenger During the Years 1873-76 (H.M. Stationary Office, London).

Keywords: HMS Challenger, early-industrial era, tow-net samples, sediment contamination, Ocean Bottom Deposits, X-ray micro-computed tomography (μCT)

Citation: Zarkogiannis SD, Wood TJ, Miller CG, Stukins S and Clark B (2025) Reassessing the HMS Challenger collection as a late 19th century surface ocean indicator using X-ray micro-computed tomography. Front. Mar. Sci. 12:1454260. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2025.1454260

Received: 24 June 2024; Accepted: 26 February 2025;

Published: 21 March 2025.

Edited by:

Allan Douglas Cembella, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), GermanyReviewed by:

Alberto Sánchez-González, National Polytechnic Institute (IPN), MexicoCopyright © 2025 Zarkogiannis, Wood, Miller, Stukins and Clark. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Stergios D. Zarkogiannis, c3Rlcmdpb3MuemFya29naWFubmlzQGVhcnRoLm94LmFjLnVr; Thomas J. Wood, dGhvbWFzLndvb2RAZWFydGgub3guYWMudWs=

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.