- Fudan Institute of Belt and Road & Global Governance, Fudan University, Shanghai, China

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) is a widely ratified multilateral treaty that defines and codifies the standards and principles of international law for the governance and management of the oceans. One of its key features is the facilitation of the peaceful settlement of disputes on maritime affairs. Article 281 constitutes an equality test by which the courts or tribunals can distinguish voluntary procedures from compulsory proceedings. Existing cases under Part XV did not provide a clear routine what circumstances might make a treaty under Article 281 “unequal”. Article 311 deals with the tension between prioritizing the regional arrangements and maintaining UNCLOS as a closed, self-contained system. This research aims to provide insights into the proper application of these two articles in future UNCLOS disputes, as the Timor Sea Conciliation (Timor-Leste v. Australia) is the first instance of the conciliation mechanism under UNCLOS. Through the methods of doctrinal research and comparing the different argumentations in previous cases, the research found that the recent Timor Sea Conciliation was decided on the basis of a controversial understanding of UNCLOS Articles 281 and 311; that a treaty featuring specific and feasible arrangements for dispute settlement would be easier in passing Article 281’s test; and that Article 311 favors UNCLOS’s integrity and considers the permitted derogations as exceptions. It is suggested that the courts or tribunals under UNCLOS Part XV interpret Articles 281 and 311 in a systematic manner, which is believed to benefit the development of voluntary dispute settlement mechanism under UNCLOS in the long run.

1 Introduction

Treaties bind parties based on consent through signature and ratification and contains laboriously negotiated commitments (International Law Commission, 1980; Abbott and Snidal, 2000). In contrast to soft, non-binding international agreements, treaties represent hard rules and are less susceptible to self-serving interpretations by the parties involved. However, similar to agreements in private law (Lauterpacht, 1927), consent sometimes does not represent a true willingness. It can also happen that a party decides to withdraw from its existing treaty obligations even if its consent was true earlier. In these circumstances, the party must have a legitimate basis for terminating unwanted, unduly burdensome, but binding agreements (Craven, 2005). One direct way to opt out is to invalidate the treaty. A common way to achieve this is to claim that treaties are unequal (Denby, 1924; Fishel, 1952; Gong, 1984; Turner, 1929; Vincent, 1970; Woodhead, 1931). In bilateral treaties, the party that deems the treaty beneficial will support it and insist that the complaining party continue fulfilling its obligations. Different ways to interpret treaties as “unequal” cause confusion in legal scholarship and hinder peaceful dispute settlement. What types of treaties are unequal? Which party can declare this? Is the mere claim of inequality sufficient to constitute a legitimate basis for deviating from pacta sunt servanda, an ancient general principle recognized by civilized nations in international law by which a promise made by a party in an agreement must be maintained (Lauterpacht, 1927)? Is there a limitation on the scope (what is the extent of the required inequality)? What other options do the parties have? Is there something parties can do to avoid future disputes when negotiating a treaty?

The international disputes awaiting settlement highlight the need for further inquiry (Koskenniemi, 2006). One example of unequal treaties came into play in the law of the sea when the recent Timor Sea Commission moved to negate Timor-Leste’s binding of the Certain Maritime Arrangements in the Timor Sea (CMATS) with Australia because of equality. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) plays a significant role in this field. Its DSMs are the focus of this study. Part XV, “Settlement of Disputes,” contains three sections, namely, general provisions (Articles 279 to 285), compulsory procedures entailing binding decisions (Articles 286 to 296), and limitations and exceptions to the applicability of section 2 (Articles 297 to 299). These Articles articulate both voluntary and compulsory proceedings and specify when each applies (I.C.J. Reports, 1985; Rosenne, 2006; Shihata, 1965; Tamada, 2019).

Article 281 is a crucial provision because it contains a law of conflict that addresses the order of the two categories of proceedings (Jia, 2015). If the parties fully satisfy the elements of Article 281, they will not have to bring their dispute to arbitration under the compulsory proceedings in section 2. The wording of the Article signals a preference for limiting the use of compulsory proceedings or at least a preference for the parties’ “settlement of a dispute by a peaceful means of their own choice.” Article 281 requires persuasive evidence to show that “the two parties have agreed” (Yee, 2014). This raises the question of the type of agreement that qualifies. Opinions in the literature vary regarding what Article 281(1) requires (Yee, 2013). In practice, language leaves a large margin of discretion for courts, tribunals, or commissions (Tanaka, 2019). Article 286 recognizes the seisin of these bodies, which, through treaties or special agreements, gives them certain jurisdictions to decide a dispute (Rosenne, 1989). This manifests as the doctrine of la competence de la competence, which is incidental to exercising substantive jurisdiction (Fitzmaurice, 1986). Whether the court, tribunal, or Commission regards Article 281(1) as satisfying the competence decision determines whether the disputants will invoke compulsory proceedings. Controversies over competence arise easily when one party submits a dispute to a compulsory proceeding unilaterally following the parties’ previous attempts to reach a voluntary settlement. If the decision sustains the other party’s objection that there was an agreement allegedly consistent with Article 281, it will not invoke compulsory proceedings. In turn, the initiating party might try to eliminate the existing treaty, either by invalidating it or changing its arrangements in front of the decision.

As the first well-known conciliation case under Annex V of UNCLOS, the Timor-Leste and Australia Conciliation has a unique bargaining history, including an exchange of letters between the parties and the signing of CMATS. The status of these documents is an essential point of disagreement. Some seemingly neutral arrangements that turned out to have a potentially oppressive effect in CMATS make the case ideal for exploring how unequal treaties and Part XV’s compulsory proceedings under UNCLOS interact (leaving aside the question of whether CMATS itself is unequal). This case also evokes Article 311, which discusses the relationship between UNCLOS and other arrangements; that is, whether Article 311 could tolerate the CMATS including an article that precludes the application of UNCLOS Part XV.

The objective of this research is to draw a line on what kind of treaties may pass the Article 281 test and to sketch a benchmark of Article 311 through the reasonable interpretation of integrity and compatibility. To achieve this objective, the methods of doctrinal and comparative research are adopted through the whole research. In Section 2, the method of game theory is used to evaluate the three essential indicators’ interaction in this case. The passage below will go into whether CMATS is an unequal treaty under UNCLOS Article 281 and its legal consequences if yes; also, it analyzes the elements of a so-called unequal treaty and summarizes the features of a treaty that easily pass the Article 281 test; last but not least, it observes how the previous cases apply Article 311 and give a reasonable interpretation of the compatibility under UNCLOS. For the development of passage, the research regards permanent or temporal bodies for solving disputes as Global Governance Bodies (GGBs) (Benvenisti, 2014). If not explicit otherwise, their role is presumed to contribute to the peaceful settlement of disputes and promote the rule of law in the international community. The study below will first look into the framework for evaluating the equality of a treaty, the Article 281 test, with the contents of the Conciliation (Section 2); second, compare the interpretation of Article 281 by the Conciliation Commission with that of other existing rulings and find the regularities in international judicial practice; third, analyze the Commission’s interpretation of Article 311 and compare it with other GGBs’ rulings. The conclusion will be summarized based on the findings of these sub-questions.

2 Framework for evaluating treaty inequality: how do “unequal treaties” coordinate with UNCLOS?

The existing literature on unequal treaties mainly focuses on the status of the parties (subjects), the contents of the provisions (the distribution of rights and obligations), and negotiation history (Detter, 1966). Positivist analyses frequently examine these three indicators separately to determine whether a treaty remains valid (Davis et al., 2012). However, whether a treaty is valid only touches the issue’s surface. This study believes that a systematic framework for evaluating treaty inequality, a three-indicator pattern, can depict the scope of inequality (i.e., how unequal a treaty is). To increase clarity and maintain accuracy, this part adopts the traditional legal approach to interpretation when analyzing the content of provisions, as mentioned above in Section 1. To illustrate the dynamic, changeable, and somewhat mysterious interactions among the three indicators, it also employs game theory to analyze potential inequality in the status of parties and uses a sociological approach to examine the parties’ negotiation history. The analysis below in this section shows a full picture of the Timor Sea Conciliation and the unique relation between the two parties.

2.1 Party status: role of game theory

The original status concern mainly refers to the inequality charge that a treaty might cement an inferior relationship between two parties; in other words, the establishment of extraterritorial jurisdiction (Willoughby, 1922). The rationale behind this concern is that territorial sovereignty entails exclusive jurisdiction over the people and property within a state (Wheaton, 1880; Piggott, 1907). Thus, it is unlikely that the two parties can reach an equal treaty if either party is not fully sovereign (De Jonge, 2014; Simpson, 2000). The condition of sovereignty is not comprehensive enough to cover all issues relevant to status, and inequality is broader than the context of colonization. The statuses of parties can be unbalanced in various ways, even if both have full sovereignty.

In international relationship studies, game theory is an ideal tool to identify the degree of balance between parties, one that comes into play before any treaty analysis. Several possible game theory scenarios are appropriate for different areas of international law, as parties face varying opportunity costs depending on the situation (Raustiala, 2005). In specialized areas of international law, such as the Law of the Sea, the status of each party in a dispute has considerable influence on the game they will play and how they will play it.

2.1.1 Instability of asymmetric bargaining in prisoners’ dilemma

In theory, as a means of cooperation between two parties, a binding treaty deters cheating by increasing the cost of non-compliance. This makes it particularly advantageous in the Prisoners Dilemma (the “PD”) situations (Abbott and Snidal, 2000). The prisoner’s dilemma is a game theory thought experiment involving two rational agents, each of whom can either cooperate for mutual benefit or betray their partner (“defect”) for individual gain. The dilemma arises from the fact that while defecting is rational for each agent, cooperation yields a higher payoff for each. In PD, the potential for costly opportunism is high and cheating is difficult to detect. When incentives to defect from agreed upon commitments are low, a binding treaty with enforceable commitments seems less valuable (Braford, 2010). This resembles a Coordination Game (a “CG”) situation, where the parties are not motivated to deviate from their agreement once they have established the focal point of coordination (Abbott, 1989; Martin, 1993). Therefore, including a dispute settlement mechanism in their treaty might not be necessary. Soft law can work in a CG where the rules can be precise, giving parties confidence that they will not be sued (Abbott and Snidal, 2000).

A stable PD situation relies on the fact that the two parties, A and B, have a similar capacity to hurt each other once they are betrayed; therefore, it requires that A and B have equal, or at least balanced, bargaining powers. In a situation where A is disproportionally stronger than B, A will have less concern about B’s betrayal since B cannot cause great harm. In addition, any defect in B’s part is easily visible to A’s more sophisticated monitoring techniques and strategies.

UNCLOS has dominated maritime law since 1994 (Adi, 2009). Although the signing parties recognize UNCLOS as a comprehensive regime, it cannot cover all specific maritime rules (Boyle, 2005). Sometimes, general provisions are not broad enough to resolve complicated disputes among the parties. This explains why parties to UNCLOS negotiate regional or bilateral agreements, including binding treaties and non-binding soft agreements. Parties to regional or bilateral agreements reached before and after the effective date of UNCLOS can consider these parallel agreements under Article 281. Australia and the Democratic Republic of Timor-Leste, for example, agreed that CMATS would be a binding treaty. This choice might represent a PD situation in which both parties wanted to enhance the results of their negotiations and prevent the other party from defecting. However, bargaining power between the two parties is far from balanced. Australia has long been a strong marine power, while Timor-Leste did not achieve independent status as a sovereign state until 2002. Their strengths of threat to each other’s potential betrayal are unequal, making the PD situation unstable.

A PD situation usually remains stable when the two parties suffer from the same lack of information: A cannot know whether B will defect (or has defected) and vice versa. Australia ratified UNCLOS in 1994, whereas Timor-Leste did not become a party until 2013. In 2006, when the two reached the CMAT, it was fair to assume that Australia had a much more sophisticated understanding of the Law of the Sea regime and maritime arrangements than Timor-Leste.

2.1.2 UNCLOS’s role in redressing the unbalanced regional agreement

When the contents of UNCLOS were settled in 1982, several regional maritime agreements existed among the parties (Bateman, 2007). The incorporation of Article 311, dealing with UNCLOS’s relationship with other conventions and international agreements, suggests that the framers recognized this situation and expected it to continue. Article 311(2) of UNCLOS explicitly maintains the rights and obligations of state parties arising from other agreements compatible with the Convention as long as they do not affect other parties’ enjoyment of their rights or the performance of their obligations under the Convention. Article 311(3) of UNCLOS permits the parties to conclude agreements modifying or suspending the operation of the Convention, applicable solely to the relations between them, through the procedure of the depositary under Article 311(4), which calls for them to notify the other State parties of their intention to do so. However, this permission does not apply if (a) the agreements relate to a provisional derogation that is incompatible with the effective execution of the object and purpose of the Convention, (b) the agreements affect the application of the basic principles embodied in the Convention, or (c) the agreements affect other State parties’ enjoyment of their rights or performance of their obligations under the Convention.

The second and third paragraphs of Article 311 are complementary. Article 311(2) deals with parties’ relations to existing agreements before the Convention, and Article 311(3) focuses on newly negotiated agreements based on the Convention. The requirement of non-derogation from the object, purpose, and basic principles of Article 311 demonstrates the framers’ intent to redress the imbalance that can arise from regional or bilateral agreements. By excluding arrangements that deviate from the object and purpose of the Convention, Article 311 takes the basic principles of UNCLOS as a benchmark from which “declares” an imbalance arising from parallel treaties.

2.1.3 Who will redress the imbalance in UNCLOS?

What if the benchmark were unbalanced? As the Third United Nations Conference negotiated the Law of the Sea, a huge gap in bargaining power among all UNCLOS parties became evident (Beesley, 1983). The parties that signed and ratified UNCLOS after it took effect in 1994 felt that the Convention did not adequately reflect their interests. This has made the overall status of UNCLOS parties even more unbalanced. Timor-Leste became a party to UNCLOS in 2013; it did not have a voice in 1982 when other parties negotiated the Convention’s rules. However, this history has not excused any signing party from its obligations under UNCLOS. Many theories may justify this apparent inequality. There is an implied assumption that by joining the agreement, a new party accepts all the rights and obligations that it imposes by default (Weisburd, 1996), or, more aggressively, that the role of UNCLOS amounts to customs under the Law of the Sea and therefore binds even newly entering parties (Caminos and Molitor, 1985).

UNCLOS framers attempted to redress the regional or bilateral maritime agreements imbalance through the Convention (Boyle, 2005). However, the parties’ unbalanced status affects their negotiation ability to enter UNCLOS. Some regard the voluntary dispute settlement procedures in Part XV as reserved for party autonomy to rebalance the imbalance from UNCLOS. This efficacy relies on properly interpreting the relevant provisions in the parallel treaty for voluntary settlements and essential articles in UNCLOS Part XV.

2.2 Contents of provisions: the pros and cons of interpretation

Interpretation is the most commonly used approach in dispute settlement analyses (Van Damme, 2010). When the bodies established (or authorized) in the dispute settlement arrangement turn to this method, at least one party has already defected. Interpretations of relevant articles in a competence decision are significant when weighing whether the challenge from the betraying party is reasonable and whether the changes this party seeks are worth considering. How GGBs interpret specific articles reflects their attitudes toward the equality (or inequality) of the content of provisions and their inclination to change or maintain the status quo.

2.2.1 What types of provisions are unequal?

The existing literature on unequal provisions is substantial (Ku, 1994; Trinity College Library, 1927; Wong, 2003). Unequal treaties usually fall into one of three categories: (a) treaties containing formally unequal obligations, regardless of their actual effect; (b) treaties with formally equal provisions that impose unequal obligations in reality; and (c) treaties in scenario (b), the unequal obligations that occur as a result of unforeseen developments (Malawer, 1977). However, most existing analyses of these categories focus on the parties’ bad faith rather than on the influence of the provisions (Craven, 2005). This study posits that the latter aspect deserves attention.

Of the three categories, scenario (a) presents the most apparent circumstance of inequality because it can contain extreme, non-reciprocal arrangements of duties and rights. When a treaty confers almost all rights to one party and imposes all corresponding duties on the other, its inequality is self-evident. In scenario (b), the parties may or may not have been aware of the inequality. In evaluating this category of articles, we must examine the extent to which the vulnerable party’s enjoyment of its equal rights speaks louder than whether bad incentives exist under the cover of apparently equal provisions. Scenario (c) makes it difficult to prove the incentive to create or even the foreseeability of inequality. However, some adjustments are necessary if one party has unequal obligations.

Few treaties in the UNCLOS era (since it entered into force in 1994) have contained nonreciprocal distributions of rights and duties. Most circumstances that GGBs have confronted resemble scenarios (b) and (c), so they require careful interpretation. GGBs with jurisdiction under Section 2 must apply the Convention and other international law rules in ways compatible with the Convention. Article 31 of the Vienna Convention, recognized as the customary standard in treaty interpretation, also binds to GGBs (Merkouris, 2017).

Therefore, a GGB is expected to perform its interpretation using the applicable laws of UNCLOS, the framework of the Vienna Convention’s interpretation rules, and good faith (Villiger, 2011).

2.2.2 Interpretation of treaty provisions in the context of UNCLOS Article 281

Timor-Leste commenced its conciliation with Australia through a notification under Section 2 of Annex V, announcing that it sought to solve a dispute concerning “the interpretation and application of Articles 74 and 83 of UNCLOS for the determination of the exclusive economic zone and the continental shelf between Timor-Leste and Australia including the establishment of the permanent maritime boundaries between the two States” (Notification instituting Conciliation, 2016). The Conciliation Commission was established under Article 298(1)(a)(i). Australia did not object, although it did object to six other areas. The first, second, and third objections relate to the status of CMATS and the exchange of letters in the context of Article 281, namely, whether their contents and negotiation history consisted of an agreement for the purpose of Article 281(1). On September 19, 2016, the Commission issued its “Decision on Australia’s Objections to Competence,” in which its members unanimously rejected all of Australia’s objections, although to different extents. This section examines the Commission’s analysis of how the unequal properties of the CMATS negated voluntary settlements.

2.2.2.1 How did the Commission interpret the CMAT provisions and Article 281?

Australia’s third objection suggests that exchanging letters constituted an agreement to resolve delimitations through negotiations within Article 281 (Alkatiri, 2003; Howard, 2003). The Commission interpreted Article 281 as requiring a legally binding agreement and rejected this suggestion, stating that letters on the subject did not reflect a binding agreement (the Commission). This interpretation relied mainly on the Commission’s perception that Article 281 was parallel to Article 282 and that Article 282 required a binding agreement. Under Article 282, parties that agree to a general, regional, or bilateral agreement to submit their dispute to a procedure entailing a binding decision are explicitly permitted to opt out of the UNCLOS DSM. According to the Commission, allowing a nonbinding agreement to create the same opting-out effect would be logically inconsistent.

Australia based its first and second objections on the moratorium provisions in the CMATS. It claimed that Article 4 of this treaty was consistent with Article 281(1) of UNCLOS and thus should exclude the parties from compulsory proceedings (Australia). CMATS is a binding treaty in which Article 4, entitled “moratorium,” provides that “neither Australia nor Timor-Leste shall assert, pursue or further by any means in relation to the other Party its claims to sovereign rights and jurisdiction and maritime boundaries for the period of this Treaty,” and that “neither Party shall commence or pursue any proceedings against the other Party before any court, tribunal or other dispute settlement mechanism that would raise or result in, either directly or indirectly, issues or findings of relevance to maritime boundaries or delimitation in the Timor Sea (CMATS).” The Commission regarded the contents of that article as “not to seek settlement of the Parties’ dispute over maritime boundaries for the duration of moratorium,” and rejected these two objections for that reason (the Commission).

2.2.2.2 Was there any problem with the Commission’s word game analysis?

There were some problems with the Commission’s word game analysis. First, the Commission did not explain what “parallel” means in this context, nor did it offer its reasons for interpreting the two articles as parallel. As Article 282 clarifies that it deals with situations in which there are binding agreements between parties, Article 281 might have been designed exactly for situations requiring voluntary dispute settlement in which there are no binding agreements. This is also consistent with the purpose of Article 280, which emphasizes that the parties’ right to settle a dispute between them “by any peaceful means of their own choice” should not be impaired. However, adjacent articles do not necessarily have the same meaning. They serve similar purposes from different perspectives. The requirement of “binding” in Article 282 mainly focuses on the procedural dimension, such as the signature and ratification of the general, regional, or bilateral agreement. Without such a formal procedure, if an agreement contained specific language about how the parties would voluntarily settle a dispute, it would seem to qualify under Article 281(1).

Second, why can a binding convention not tolerate some nonbinding arrangements as long as they are compatible with the convention? Several binding conventions include voluntary multi-lateral arrangements (WTO Ministerial Conferences, 2019). Soft rules should not be excluded from the Convention because they are nonbinding. In reality, the degree to which hard provisions can bind parties varies. Articles 281 and 282 constitute the coordination of international legalization in which hard and soft rules have complementary roles. Soft rules are advantageous in terms of their precision (Abbott and Snidal, 2000). Permitting parties to opt out of a binding convention through a soft arrangement does not create logical inconsistency as long as the arrangement does not contradict the Convention. Additionally, if the arrangement in soft form incorporates the “close-to-binding” contents in substance, this resolves the logical inconsistency.

The Commission was silent on whether to interpret Article 4 of the CMATS as an unequal provision. Negating this for voluntary settlement under UNCLOS Article 281(1) does not amount to a declaration of inequality. GGBs use extreme caution and never speak of this point. However, in strict compliance with the textualism of the Vienna Convention, the literal meaning of CMATS Article 4 merely implies the intention to enhance existing treaty remedies and avoid further disputes. Evaluating whether this provision is unequal requires weighing whether an overconfident assumption that there will not be any dispute in the future can create the effect of oppressing either party and disproportionally balance the contents of the treaty. Same or similar rights and obligations can mean considerably different things for the two parties in asymmetric bargaining. The contents of Article 4 appear to bind parties with the same obligation, that is, to refrain from submitting their disputes to GGBs outside the CMATS. In this instance, the seemingly identical obligations in this article would have had a different effect on each party; they might have deprived Timor-Leste of its core interests. This reasoning emphasizes unequal influence, but the evidence is not strong enough to imply that one party had such bad faith that it was willing to deprive the other party of the chance to seek external judicial or arbitral remedies. Therefore, a combined influence-incentive analysis outperforms Malawer’s classic incentive-oriented view of feasibility. The question of whether negative incentives exist goes beyond mere interpretation. A sociological approach to deepening the background will help us better understand the incentive aspect of this matter.

2.3 Negotiation history: a deep sociological analysis of the treaty’s background

Among the three indicators of unequal treaties – the status of parties, the contents of provisions, and negotiation history – the history of bargaining is the most dynamic. Unique stories in the negotiation history (the “NH”) might also reflect the unbalanced status of the parties and even affect what information they choose to include in their draft complaint. NH is the basis of the three-indicator pattern, which maps a general model of their interaction. Much scholarship has focused on the NH, especially examining the number of invalidated treaties after the end of the colonial period, but some questions remain unanswered.

2.3.1 Existing international law governing NH of treaties

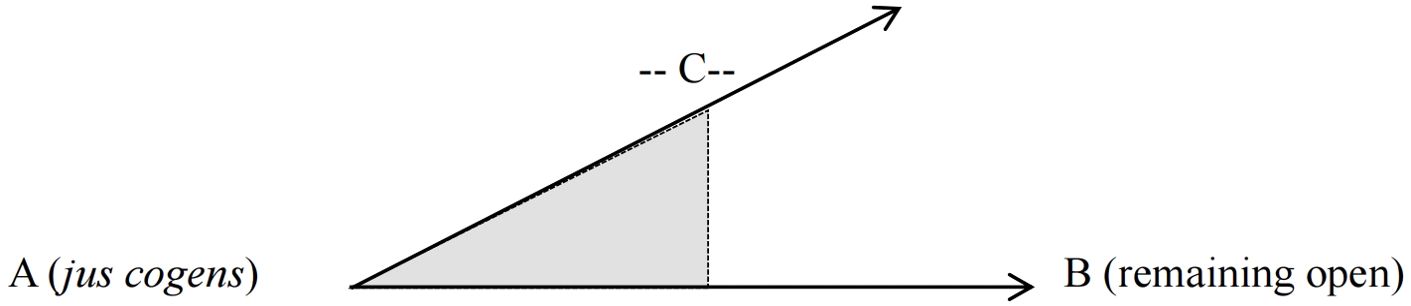

The contemporary rules governing the NH of treaties describe a ray of the matrix (Figure 1) (Crawford, 2006; Kritsiotis, 1998). One end (point A) was fixed by preventing the use of force (Dinstein, 2005; Frowein and Cogens, 2009). To different extents, Articles 51 and 52 of the Vienna Convention invalidate treaties procured through the unlawful use of force. The species was established as jus cogens. The justification for invalidating a treaty that a party procures in this manner lies in the lack of free consent and the behavior of the party that, under duress, cannot express its true preference (Lauterpacht, 1927). This implies an imbalance in the bargaining positions of the two parties when a treaty is concluded (Craven, 2005). The unequal status of the parties does not necessarily result in an unbalanced treaty. However, an extreme disparity in their NH automatically makes a treaty unequal (and even invalid) based on the jus cogens violation.

Figure 1. One end (point A) was fixed by preventing the use of force. To different extents, Articles 51 and 52 of the Vienna Convention invalidate treaties procured through the unlawful use of force. The species was established as jus cogens. Treaties within the shaded zone might be unequal treaties, or they might merely be asymmetric bargained agreements. This depends on how line C (representing the degree to which the parties are unbalanced in bargaining) moves along the ray. The indicator NH provides a playing field in which the status of parties can change and, in so doing, can bring about a change in the content of provisions. This happens when a strong power incidentally suffers from an unexpected development that decreases its bargaining strength and increases its willingness to accept less beneficial arrangements than those it had once hoped for. This change may have saved the treaty from potential charges of inequality.

Therefore, NH is a decisive indicator. A history of negotiations without extreme oppression is a prerequisite for an equal treaty.

What was the other end of the ray? This is merely asymmetric bargaining, which can describe a variety of treaties in the contemporary, unbalanced international community. Model Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) in the investment regime provide a good comparison (Bedrosyan, 2018). This asymmetry cannot be automatically defined as equivalent to inequality. Treaties within the shaded zone (Figure 1) might be unequal treaties, or they might merely be asymmetric bargained agreements. This depends on how line C (representing the degree to which the parties are unbalanced in bargaining) moves along the ray. The indicator NH provides a playing field in which the status of parties can change and, in so doing, can bring about a change in the content of provisions. This happens when a strong power incidentally suffers from an unexpected development that decreases its bargaining strength and increases its willingness to accept less beneficial arrangements than those it had once hoped for. This change may have saved the treaty from potential charges of inequality.

The indicator NH can depict how unique stories influence the positions of the parties and might cause further differences in the content of treaty provisions.

2.3.2 What happened in the negotiation history of CMATS?

This section briefly introduces the notorious spying scandal and analyzes how it relates to the imbalance between the two parties, the contents of the treaty, and Australia’s bad faith. It began in 2004 when the Australian Secret Intelligence Service (“ASIS”) clandestinely planted covert listening devices in a room adjacent to the Timor-Leste Prime Minister’s Office in Dili, the country’s capital, to obtain information that would ensure that Australia held the upper hand in its negotiations with Timor-Leste over the rich oil and gas fields in the Timor Gap (Collaery, 2013). Although the Timor-Leste government was unaware of Australia’s espionage operations, negotiations were hostile. The first Prime Minister of Timor-Leste, Mari Alkatiri, bluntly accused Australia’s Prime Minister, John Howard, of plundering the oil and gas in the Timor Sea, stating: “Timor-Leste loses $1 million a day due to Australia’s unlawful exploitation of resources in the disputed area. Timor-Leste cannot be deprived of its rights or territory due to crime (Marian and Cronau, 2014).” Ironically, Australian Foreign Minister Alexander Downer responded, “I think they’ve made a very big mistake thinking that the best way to handle this negotiation is trying to shame Australia, is mounting abuse on our country and accusing us of being bullying and rich and so on, when you consider all that we are done for East Timor (Marian and Cronau, 2014).”

Witness K, a former senior ASIS intelligence officer who led the bugging operation, confidentially noted that in 2012, the Australian Government had accessed top-secret, high-level discussions in Dili and exploited these during negotiations over the Timor Sea Treaty (Steve, 2016), which CMATS later superseded. Timor’s Prime Minister, Xanana Gusmao, discovered the bugging and, in December 2012, told the Australian Prime Minister, Julia Gillard, that he knew of the operation and wanted the treaty to be invalidated, as a breach of good faith had occurred during the treaty negotiations (Marian and Cronau, 2014). Prime Minister Gillard did not agree with the invalidation of the treaty. The first public revelation of an allegation of the 2004 espionage in Timor-Leste appeared in 2013 in an official Australian government press release. Interviews with Australian Foreign Minister Bob Carr and Attorney-General Mark Dreyfus detailed the alleged espionage and several subsequent media reports (Marian and Cronau, 2014). The knowledge of the espionage led Timor-Leste to reject the treaty on the Timor Sea and refer the matter to the International Court of Justice (the “ICJ”) in The Hague (Allard, 2014). Timor’s lawyers, including Bernard Collaery, intended to call Witness K as a confidential witness in an “in camera” hearing in March 2014. However, in December 2013, the ASIO and the Australian Federal Police raided the homes and offices of both Bernard Collaery and K, confiscating many legal documents. Timor-Leste immediately sought an order from the ICJ to seal and return documents (Allard, 2014). In March 2014, the ICJ ordered Australia to stop spying on Timor-Leste and not interfere with the communication between East Timor and its legal advisors in arbitral proceedings and related matters (Allard, 2014; Allard, 2016).

In April 2013, Timor-Leste launched a case in the Permanent Court of Arbitration in the Hague to pull out a gas treaty that it had signed with Australia, accusing the latter of having had an ASIS bug in the East Timorese cabinet room in Dili in 2004 (I.C.J, 2015; International Court of Justice, 2015). Timor-Leste initiated a conciliation case over the sea border shared with Australia in April 2016. Timor-Leste believes that much of the Greater Sunrise oilfield falls under its jurisdiction, and that it has lost $US5 billion to Australian companies as a result of the treaty that it now disputes (Allard, 2014; Gusmao et al., 2013).

The imbalance of their bargaining status is obvious from this story. Australia’s spying thoroughly and flagrantly took advantage of Timor-Leste’s weaknesses in strength, techniques, and information. Subsequent attempts to hide evidence and punish whistleblowers further proved the government’s willingness to use its superior position. The ICJ’s order to stop spying had the effect of declaring it illegal.

2.3.2.1 Did Australia’s spying in NH constitute coercion?

Article 51 of the Vienna Convention prohibits the coercion of representatives of other negotiating states. If one party procured the State’s consent through an act or threat directed against the State’s representative, that consent would not have any legal effect. Is spying on a representative act or a threat to him? The negotiations were hostile, but the Prime Minister of Timor-Leste did not feel threatened during the bargaining. The spying process is secret, and it is difficult to argue that a given act imposes a threat on someone who has no knowledge of it.

Article 52 voids any treaty concluded through a threat or the use of force in violation of the principles of international law embodied by the UN Charter (International Court of Justice, 1986). Is espionage the use of force in violation of UN principles? The UN has never explicitly addressed this issue outside the context of war (Chesterman, 2006; Demarest, 1996). The convergence of international law and peacetime espionage is highly controversial (Prochko, 2018).

The ICJ officially removed the case, “Questions relating to the Seizure and Detention of Certain Documents and Data,” from its to-do list on June 12, 2015, after Timor-Leste confirmed that Australia had handed back the relevant papers (I.C.J, 2015). Timor-Leste’s agent explained that “following the return of the seized documents and data by Australia on May 12, 2015, Timor-Leste has successfully achieved the purpose of its Application to the Court, namely the return of Timor-Leste’s rightful property, and therefore implicit recognition by Australia that its actions were in violation of Timor-Leste’s sovereign rights.” Leaving aside the question of whether Australia had confirmed a violation of sovereignty, there was no use of force.

Therefore, the existing law governing NH did not apply to Australia’s spying activities.

2.3.2.2 What was Australia’s real incentive behind Article 4 of CMATS?

Seemingly balanced provisions can impose unequal effects on the parties [see Scenario (b)]. Evaluating such circumstances requires us to consider both the incentives and influences.

Peter Galbraith, the lead negotiator for Timor-Leste, laid out the motives behind ASIS’s espionage, “What would be the most valuable thing for Australia to learn is what our bottom line is, what we were prepared to settle for. There’s another thing that gives you an advantage, you know what the instructions the prime minister has given to the lead negotiator. And finally, if you’re able to eavesdrop you’ll know about the divisions within the East Timor delegation and there certainly were divisions, different advice being given, so you might be able to lean on one way or another during the negotiations (Marian and Cronau, 2014).” A statement from a victim’s agent may be vulnerable to claims that it lacks objectivity. Nevertheless, there is a gap between seeking advantageous bargaining status by exploring the counterpart’s information and the incentive to oppress that party. Australia’s spying exacerbated its already unbalanced status and widened the gaps in techniques, intelligence, and negotiation strategies between the two powers. Article 4 of CMATS restricts further sea claims by Timor-Leste until 2057, which may lead to a continuing or even expanding imbalance between the two parties. This is consistent with the suggestion that the status of the parties was “unequal.”

Australia’s spying intensified its superior bargaining position, aggravated the existing imbalance, and exposed its bad faith, which affected the parties’ NH. CMATS enhanced the unbalanced results of the negotiations, which might have had an unfair effect on Timor-Leste. Such an influence, together with the bad incentives of the superior party, makes the apparently neutral Article 4 of CMATS an unequal provision. This part believes that the Commission implicitly relied on this analysis to negate the treaty for the purposes of Article 281(1). The three-indicator pattern shows how the concept and analysis of unequal treaties coordinates with UNCLOS Part XV.

2.4 Further implications: how would the Commission’s interpretations influence future treaty negotiations and international law practices?

The influence on future negotiations and international law practices could not be ignored by GGBs, though a case ruling is not binding in the international community. Coherence in homogeneous or similar issues is always a pursuit of international judicial decision making. This influence does only affect the future interpretations of the articles concerned, but also the enforcement mechanism of a convention as a whole, especially when a convention dominates a field of rules in a systematic manner. UNCLOS is regarded as a Charter in the law of the sea, which provides an apparent necessity to look into its enforcement mechanisms when we discuss its articles’ interpretations.

2.4.1 The harms of a defective interpretation on the predictability of international law development

It is difficult to recognize the Timor Sea Conciliation competence decision without defects. In sum, the interpretation approach excels in identifying the primary evidence of the parties’ intentions (preventing future disputes) through the terms adopted in the provision. However, textualism cannot locate the exact incentives for any party without going deeper into the negotiation history behind a treaty. The frequent ambiguity in treaty terms contributes to this difficulty. This research analyzes the logic of this ruling from the perspective of unequal treaties and finds that CMATS, the parallel treaty between Timor-Leste and Australia, embodies some inequality characteristics that might have justified the Commission’s expansion of jurisdiction. The Commission’s word game analysis of Article 281 reveals that GGBs are willing to be selective when they interpret UNCLOS articles at the jurisdictional stage. The Commission’s interpretation of the explicit exclusion of further procedures as “not to seek settlement” damages the predictability of international judicial making, which, according to some scholars, caused an apparent expansion of the Commission’s competence.

2.4.2 The interpretation between the equality test and the enforcement mechanism under UNCLOS

The life of a legal rule lies in its enforcement. The probable hardship in enforcing a ruling would to a large extent affect the dignity or the authority of the GGB that made the ruling. The overreaching statement of the Commission on the equality test was intended to achieve effectiveness, meaning that GGBs should consider the consequences of their decisions (on whether the dispute could be settled after decision-making) in their ruling process in dispute settlement (as is further implied in Section 3.3 below), would increase the obstacles in enforcing the ruling, lower the feasibility in fulfilling the contents in the decision, and in turn harm the objective of effectiveness. However, the Annex V Conciliation is located by UNCLOS Part XV as a voluntary, non-compulsory proceedings, which is not as binding as the other proceedings, such as the ITLOS litigations in Annex VI and the arbitrations in Annex VII.

The GGB aims to adjust the unbalanced situation in international treaty negotiation through setting a strict standard while making voice on the equality test. This action does not contribute to the solution, while it even adds the difficulties in realizing the contents in a non-compulsory conciliation decision from the beginning. In the context of enforcement and effectiveness, the previous cases under the compulsory proceedings of UNCLOS deserve more attention, as we would look into in Section 3 below.

3 Paradox of jurisdiction: the equality test of Article 281 in conjunction with merits

Section 2 above discussed the Timor Sea case as the first Conciliation under UNCLOS in detail, showing how the Commission interpreted Article 281. However, existing rulings made by other courts or tribunals under UNCLOS did not always consist with the Timor Sea Commission. Scholars have examined Article 281 in previous competence decisions, seeking to analyze various parties’ attempts to solve disputes voluntarily. They used four criteria relevant to this article: whether the agreement between the parties for voluntary settlement needs to be a binding treaty; whether the agreement substantially covers the issues under dispute; whether the agreed means in the parallel treaty need to be exhausted; and whether its provisions need to contain an explicit exclusion of the compulsory proceedings in UNCLOS. This section goes into how the existing rulings interpret Article 281 by answering these four questions one by one and make comparisons with that of the Commission when necessary. Some previous cases made obvious counterarguments against our Timor Sea Conciliation, which in turn outstands the value in conducting comparative studies.

3.1 Existing rulings on Article 281

In various cases, the defendant parties quoted Article 281 to object to the jurisdiction of GGBs based on evidence of their previous attempts to reach a voluntary settlement. Broadly, the GGBs deciding the cases below agree that indefinite negotiation is unnecessary, but the agreement must cover the substantive issues in dispute. However, the GGBs’ opinions differ regarding what the Article requires to avoid triggering compulsory proceedings.

3.1.1 The Southern Bluefin Tuna Case (Australia and New Zealand v. Japan), 2000

One issue in the Southern Bluefin Tuna Case was how the two treaties with parallel articles bore upon a particular dispute. The “Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility of Southern Bluefin Tuna Case” in 2000 determined that the rights and duties under the two treaties were inextricably linked, “for the reason that the Convention for the Conservation of Southern Bluefin Tuna (CCSBT) was designed to implement broad principles set out in UNCLOS” (Southern Bluefin Tuna Case, 2000). Although the court declared that Japan’s reliance on the lex specialis (a legal principle prioritizing the rules in a special field against others in general fields when they contradict) was erroneous, the tribunal held that the parties had addressed all the main elements of the dispute under the CCSBT framework. Even if Article 281(1) did not require the parties to “negotiate indefinitely,” the tribunal found that the parties had not exhausted the options in Article 16(1) of CCSBT and that their failure to reach an agreement for referral of the dispute did not absolve them of the responsibility to continue to seek its resolution by the peaceful means that the Article provides. Since the 1993 CCSBT was a binding treaty, the tribunal did not shed light on whether the ruling would have changed, and there was no binding agreement. Instead, the ruling focused on whether the explicit exclusion of other dispute settlement procedures was necessary for the purpose of Article 281. As the applicant parties, Australia and New Zealand, argued, the contents of Article 16(2) of the CCSBT did not expressly exclude further dispute settlement procedures. Finally, the tribunal determined that the implicit exclusion was sufficient.

3.1.2 MOX Plant Case (Ireland v. United Kingdom), 2003

In the “Order on Suspension of Proceedings on Jurisdiction and Merits” and the “Request for Further Provisional Measures of MOX Plant Case” in 2003, the focus was on whether the Convention for the Protection of the Marine Environment of the North-East Atlantic (OSPAR) substantially covered the field of the dispute (MOX Plant Case, 2000). ITLOS believes that OSPAR did not pass the substantive coverage test to an extent that would trigger the application of UNCLOS Articles 281 and 282.

3.1.3 Land reclamation case (Malaysia v. Singapore), 2003

In the “Order of Provisional Measures on the Case concerning Land Reclamation by Singapore in and around the Straits of Johor” in 2003 (Pinto et al., 2003), ITLOS determined that Article 281 was inapplicable since both Malaysia and Singapore agreed that their meetings would be without prejudice to Malaysia’s right to proceed with the arbitration, according to Annex VII to the Convention, or to its right to request the Tribunal to prescribe provisional measures (Pinto, 2003). ITLOS based its jurisdiction on the agreement between the parties that meetings would not affect Malaysia’s right to seek remedies through UNCLOS compulsory proceedings. This ruling promoted the non-exclusion of Article 281 over its other elements. Effectively, the tribunal determined that it has jurisdiction as long as the parties explicitly permit compulsory procedures in their agreement, regardless of whether the agreement is binding, what it covers, or whether the parties have reached a settlement by the agreed means.

3.1.4 Maritime delimitation case (Barbados v. Trinidad and Tobago), 2006

The “Award of the Arbitral Tribunal concerning the Maritime Boundary between Barbados and the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago” in 2006 made an unprecedented pronouncement concerning the relationship between Articles 281 and 282. The tribunal noted that Article 282, which covers bilateral or multilateral treaties that provide for a resort to compulsory procedures that can be applied in lieu of Section 2 procedures, was inapplicable to the dispute (Schwebel et al., 2006). Its sister Article 281 the dispute, however, “is intended primarily to cover the situation where the Parties come to an ad hoc agreement as to the means to be adopted to settle the particular dispute which has arisen.” This interpretation is the opposite of the Timor Sea Conciliation Commission’s view of parallel structures. The tribunal admitted that the parties had agreed in practice, although not by any formal agreement, to settle their disputes through negotiation, which was in any event that Articles 74(1) and 83(1) imposed on them. This amounts to the admission that an agreement with no binding form can pass the threshold of Article 281(1) as long as it covers the issues in dispute. The tribunal concluded that it had jurisdiction over the merits since the parties’ de facto agreement did not exclude any further procedures under Article 281(1) and because their chosen peaceful procedure settlement procedure – negotiation – had failed to result in a settlement of their dispute.

3.1.5 South China Sea case (The Philippines v. China), 2015

The “Award on Jurisdiction and Admissibility of South China Sea Arbitration” in 2015 presented an extremely strict interpretation of Article 281. The tribunal generated three elements that form the basis of this article (overlapping three of the four focal points: whether the agreement between the parties for voluntary settlement needs to be a binding treaty, whether the agreement substantially covers the issues under dispute, whether the agreed means in the parallel treaty need to be exhausted, and whether its provisions need to contain an explicit exclusion of the compulsory proceedings in UNCLOS, regarding all of them as necessary) (Yee, 2014).

The tribunal determined that the parties did not intend the “Declaration on the Conduct of Parties in the South China Sea” (DOC) to be a legally binding agreement; this finding would have been sufficient to dispose of this issue for purposes of Article 281. According to the tribunal, the terms of the DOC reaffirmed existing obligations rather than reflecting a clear intention to establish rights and obligations between the parties, irrespective of the form or name of a document. The tribunal did not delve into the question of whether the contents of the DOC covered the dispute since its form did not conform to Article 281(1)’s requirement for a binding agreement.

The tribunal ruled that neither of the other two elements – whether the parties reached a settlement by recourse to the agreed means or whether the agreement excluded any further procedures – had been satisfied. It noted that Article 281 did not require the parties to pursue any agreed means of settlement indefinitely but said that they should abide by any limit that their agreement laid out. The lack of a time limit for the DOC and many years of futile discussions between the Philippines and China led the Tribunal to conclude that the parties had not reached a settlement.

Regarding the exclusion of Part XV procedures, the Tribunal considered both views in Southern Bluefin Tuna and adopted the dissenting view of Judge Kenneth Keith that explicit exclusion was required. By concluding that “the better view is that Article 281 requires some clear statement of exclusion of further procedures,” the tribunal broadened the availability and scope of compulsory jurisdiction under UNCLOS. It examined the “Treaty of Amity and Cooperation in Southeast Asia” (the Treaty of Amity) and other bilateral statements using the same benchmark and disqualified them under Article 281(1).

3.2 The approach in rulings on Article 281: a treaty with a specific DSM

From the start of Timor Sea Conciliation to existing rulings, opinions of the UNCLOS courts or tribunals regarding Article 281 demonstrate no consistency regarding whether it requires a binding agreement and whether it needs to be explicit about excluding further procedures to avoid the jurisdiction of the GGBs. However, based on these rulings, it is possible to roughly determine the kind of treaty that would pass the Article 281 test. The capacity of a parallel treaty to contribute to voluntary settlements, according to the GGBs’ previous decisions, is an approach in coordination with the equality test, although not readily apparent.

3.2.1 What is special about the CCSBT in the Southern Bluefin Tuna Case?

The CCSBT in the Southern Bluefin Tuna case contained a list of means for dispute settlement, including negotiation, inquiry, mediation, conciliation, arbitration, and judicial settlement. These are all routes through which future parties can reach peaceful settlements without the tribunal’s involvement. Some procedures on the list, such as arbitration and judicial settlement, can lead to a binding decision, creating an enforceable remedy similar to compulsory proceedings under Part XV. The Southern Bluefin Tuna case is the only one thus far that has been concluded with no jurisdiction. It seems far-fetched to imply that the tribunal made this decision because it thought that the parties were likely to resolve the matter on their own using the dispute settlement options in the CCSBT. However, the apparently balanced arrangements in the CCSBT may have led the tribunal to rely on the treaty’s capacity to contribute to settling disputes. Similarly, the MOX Plant tribunal suspended its jurisdiction on the merits, noting that “the essentially internal problems within the European Community legal order may involve decisions that are final and binding.” A procedure that could result in two conflicting decisions would not be helpful in resolving the dispute, and this understanding motivated the MOX tribunal to wait rather than proceed.

3.2.2 Common features of the treaties that failed the Article 281 test

The Timor Sea Conciliation is not a classic case that failed the Article 281 test. Parallel treaties concerning jurisdiction in other cases that failed Article 281 had much in common. The dispute settlement procedures in the DOC before the South China Sea Tribunal allowed only the option of negotiation, which was not a procedure that led to a binding decision. Negotiations, as the most flexible means of dispute settlement, cannot guarantee peaceful settlement within a specified period. This arrangement in the parallel treaty could easily lead a GGB to assume that a given dispute will continue or even intensify despite years of negotiation if left unsupervised. The South China Sea Tribunal interpreted Article 281 as requiring a binding treaty, namely an agreement intended to establish rights or obligations. It disqualified the DOC for the purpose of Article 281 primarily because the agreement repeated the existing arrangements without establishing any new rights or obligations. It was its dissatisfaction with the efficacy of the existing arrangements or, more directly, the risk of unending negotiations which made the tribunal unwilling to rely on this document. Of all the decisions, the Barbados/Trinidad and Tobago Tribunals made the most flexible interpretation of this form of agreement by ruling that an ad hoc agreement was sufficient.

Nevertheless, it still found jurisdiction since the parties had not managed to settle their disputes through negotiation, as they had agreed, and it was determined that their agreement contained no exclusion of further procedures. Similar to the South China Sea case, this tribunal’s analysis partly relied on the limitations of the negotiations. Without the tribunal’s intervention, it would have been almost impossible for the parties to reach a settlement merely through negotiations.

The Barbados/Trinidad and Tobago Tribunal ruled against the Timor Sea Commission on the relationship between Articles 281 and 282 and whether Article 281 requires a binding treaty. However, the root of the parties’ disagreement was the form of the parallel treaty and not its content. The Commission’s expectations of the content of a parallel treaty were similar. Specific arrangements determining the means of settlement led GGBs to believe that the parties could and would settle their disputes voluntarily, equally, and peacefully. An agreement without these would represent inequality between the parties and could contribute to a settlement. Allowing the substance of an act (especially the intention behind it) to prevail over its form is a classic tendency in international judicial rule (Acharya, 1994). The fact that the South China Sea Tribunal and the Timor Sea Commission focused on the binding form of relevant parallel agreements without examining their contents is unusual.

A preliminary conclusion is that Article 281 might not require a formally binding agreement, as Article 282 does in the procedural dimension, but that an agreement “to seek settlement of the dispute by a peaceful means of their own choice” should contain some workable arrangements by which to solve the dispute. When a parallel treaty confines the dispute to the parties without providing any feasible means of settlement, it conveys a signal of inequality and little likelihood of voluntary settlement. GGBs tend to interfere in this kind of dispute to adjust the unbalanced situation and assist the parties in reaching a settlement. Article 281 provides the equality test. While examining the equality (or inequality) of parallel treaties, the GGBs follow the following approach: whether parallel treaties between parties can come to a voluntary settlement.

3.3 The expansion of jurisdiction: judicial enthusiasm or a last resort?

Despite the lack of consistency in the existing rulings regarding the elements of Article 281, the relevant tribunals established jurisdiction for all of the above cases except for the Southern Bluefin Tuna case. The GGBs since the Southern Bluefin Tuna have all headed toward the same destination, although by divergent routes. One well-recognized justification for the expansion of jurisdiction is the principle of effectiveness, as is mentioned above in Section 2.4. This section explores the second justification for this expansion: necessity. When GGBs conduct equality tests on parallel treaties, the elements they need to observe are generally linked to the merits of the case.

3.3.1 Two principles in tension: effectiveness v. consent

Interpretations of Article 281 provide an insight into the casualty of GGBs on their own jurisdictions. Many foresaw the potential expansion of jurisdiction from the start of the UNCLOS. “It is most unlikely that a dynamic court exercising its powers will have much difficulty, both in finding that it possesses jurisdiction in a particular case and in finding that the Convention contains rules appropriate for the resolution of virtually all disputes arising under it (de Mestral, 1984).” Some regard this as judicial activism, which is not merely valuable but sometimes even necessary (Lowe, 2005). The principle of effectiveness, which allows GGBs to fulfill their judicial function, provides one justification for the judicial activism we saw above (Wolfrum, 2006; Buga, 2012). However, there is some tension between this principle and that of consent, which refers to sovereign states’ willingness to be bound by GGBs’ decisions as the foundation of jurisdiction (Permanent Court of International Justice, PCIJ, 1923). We cannot overemphasize the importance of a reasonable balance between these two principles in dispute settlement.

3.3.2 Necessity in expansion: issues not of exclusively preliminary character

It seems that expansion of jurisdiction is sometimes necessary. When the defendant party objects to jurisdiction relying on an agreement to which it is bound, initiating compulsory proceedings in UNCLOS could violate obligations under that parallel treaty. No GGB has ruled on the nature or consequences of such breaches. GGBs dealing with a binding treaty face the potential risk of challenging pacta sunt servanda. Establishing a degree of inequality that might invalidate a parallel treaty could be a persuasive justification for this deviation. The equality test of Article 281 regarding a parallel treaty involves determining whether the status of the parties is unbalanced, whether the distribution of rights and obligations in the treaty’s contents is unfair, and whether there are any coercive factors in negotiating history. These details, however, easily penetrate the substance of the case, and according to the procedural rules of UNCLOS, they are not exclusively preliminary characters.

This paradox demonstrates the necessity of GGBs’ broadening the availability and scope of compulsory jurisdiction under UNCLOS and provides another justification, or at least an explanation, for the GGBs’ keenness to expand their competence. Without the capacity to look into the substantive issues, they cannot determine whether they have jurisdiction on issues “not of an exclusively preliminary character” in a competence decision for a given dispute. In the “Jurisdiction and Admissibility Award of Guyana/Suriname Arbitration” in 2007, the tribunal considered it appropriate to rule on the Preliminary Objections in its final award. Suriname’s objections were not exclusively preliminary since “the facts and arguments are in significant measure the same as the facts and arguments on which the merits of the case depend” (Judge et al., 2007). The 2015 South China Sea award left jurisdiction over certain submissions to a substantive award for the same reason.

3.3.3 How would inconsistencies between the conciliation and former rulings on Article 281 influence the future of UNCLOS dispute settlement?

As is the case in our Timor Sea Conciliation, designing decisions regarding competence as a prerequisite involves an inherent paradox. The equality test in Article 281 touches on substantive issues, sometimes making an expansion of GGBs’ competence unavoidable. This paradox provides a second justification for expanding jurisdiction, apart from effectiveness.

According to the GGBs, the equality test in Article 281 blocks unequal parallel treaties and contributes to the peaceful settlement of disputes in the long run. Parties seeking to avoid Part XV proceedings in the future may consider attaching more importance to the agreed means of settlement in their bilateral or regional treaty negotiations, which, according to the GGBs, may increase the likelihood of reaching a peaceful settlement. These findings may inform future treaty negotiations and dispute resolutions under UNCLOS in such a manner: the parties seeking to avoid Part XV proceedings may attach more importance to the agreed means of settlement. This would in turn influence the future interpretations of Article 281, such as promoting the benchmarks again and again, influencing the predictability in UNCLOS dispute resolution mechanisms and international law practices in future.

4 The dilemma of compatibility: Article 311’s lack of clarity regarding benchmarks in UNCLOS

Section 3 above discusses the existing rulings on Article 281, which focuses on whether a parallel agreement under UNCLOS is an unequal treaty. Apart from the equality test, the compatibility benchmark under Article 311 is another controversial point in this case. Most state parties choose binding agreements when negotiating regional or bilateral marine rights and obligations; however, asymmetric bargaining easily makes agreements unbalanced. UNCLOS framers intended to redress regional or bilateral bargaining imbalance by imposing a uniform regime. However, UNCLOS resulted from asymmetric multilateral negotiations, so it had to leave space for voluntary arrangements between specific parties to remedy this issue. The benchmark regarding which regional or bilateral agreements the UNCLOS respects lies in Article 311, in which the GGBs’ decisions have rarely been discussed. This section posits that the compatibility requirement in Article 311 is as important as that in Article 281 and, therefore, deserves more attention than it has received. It can be difficult, however, to determine what “compatible” means. This section compares the Commission’s answer to those of other GGBs under UNCLOS and explores how they interpret compatibility under Article 311.

4.1 The Commission’s Understanding: a unidirectional compatibility

The Commission did not examine CMATS through the lens of Article 311 because, in its view, CMATS is not a treaty that derogates from the terms of the Convention. First, CMATS is the first of the two treaties. Second, Australia and Timor-Leste did not notify any other UNCLOS parties, as Article 311(4) requires. Third, Article 4 of CMATS did not state that the parties must be willing to modify or suspend any obligations under the Convention (the Commission). However, these reasons for ignoring Article 311 reflect the Commission’s limited assessment of its value.

Article 311 governs both the existing and later agreements through various sub-articles. Article 311(2) expressly applies to agreements that parties made before the UNCLOS came into effect. The notification requirement in Article 311(4) applies only under the circumstances of Article 311(3), which permits two or more parties to conclude agreements by modifying or suspending the operations of some UNCLOS provisions. In the existing agreements to which Article 311(2) applies, the intent to derogate from UNCLOS’ Articles need not necessarily be explicit; when parties negotiated a regional or bilateral agreement before UNCLOS, they would have had no way of knowing which articles to modify or suspend.

The Commission implicitly ruled on the meaning of “compatible,” even though it did not see Article 311 as relevant to the case. When examining CMATS Article 4 in the context of Article 281(1), it was stated that all discussions on competence must start from the Convention rather than from the CMATS (the Commission). This statement implies that all external agreements must be compatible with UNCLOS, not vice versa. The Commission did not consider the need to rebalance the inequalities inherent in the UNCLOS negotiations through regional or bilateral arrangements. This amounts to the rule that there is no basis for permitting derogation. The latter will always prevail whenever there is a controversy between other agreements and UNCLOS. This renders Article 311’s permitted derogation meaningless.

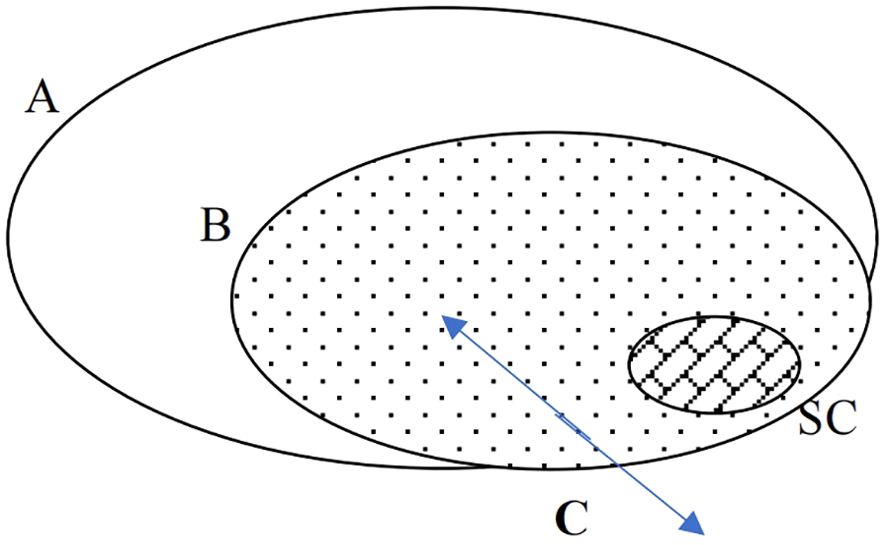

Sections (2) and (3) of Article 311 are phrased in the exception-in-exception mode. They appear in UNCLOS, where exceptions can derogate some UNCLOS articles. The second exception is to prevent that derogation from affecting the purpose, object, or basic principles of the convention. What derogation means in theory, as Figure 2 shows, is that some part of circle B (the relevant agreement for Article 281) may move out of circle A (the Convention) and that this partial exception is acceptable as long as it does not fall into the second exception (the smallest circle SC, representing the provisions against the object and purpose). C is the point at which Article 311 came into play.

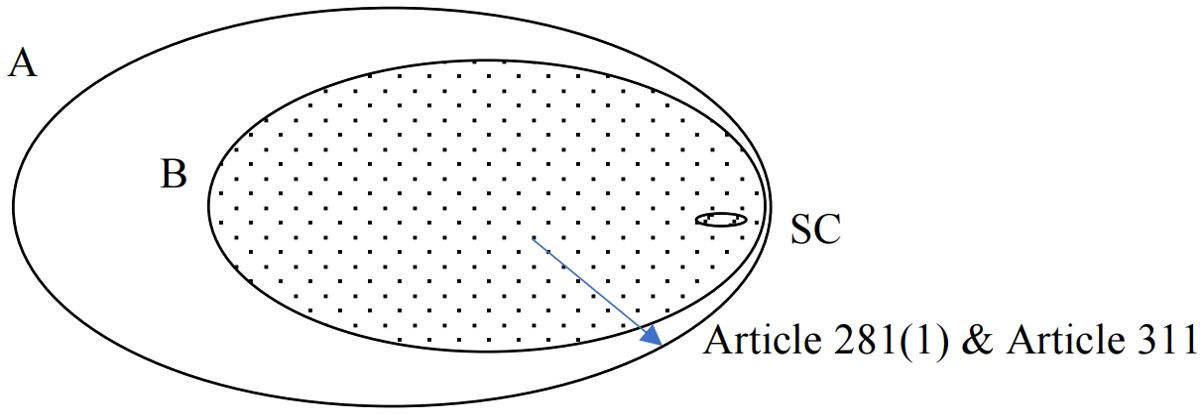

Figure 2. Sections (2) and (3) of Article 311 are phrased in the exception-in-exception mode. They appear in UNCLOS, where exceptions can derogate some UNCLOS articles. The second exception is to prevent that derogation from affecting the purpose, object, or basic principles of the convention. What derogation means in theory, as Figure 3 shows, is that some part of circle (B) (the relevant agreement for Article 281) may move out of circle (A) (the Convention) and that this partial exception is acceptable as long as it does not fall into the second exception (the smallest circle SC, representing the provisions against the object and purpose). (C) is the point at which Article 311 came into play. Imagine reasoning starting with a parallel treaty. The exception-in-exception mode becomes an exception-to-principles mode when parties incorporate a regional or bilateral agreement compatible with UNCLOS Articles into the UNCLOS framework. This parallel treaty will remain compatible with UNCLOS if it does not contradict its object and purpose. This compatibility (Figure 3) works in two ways. According to the Commission, any voluntary arrangement chosen by the parties (circle B) must remain completely within the framework of UNCLOS (circle A). The smallest circle will disappear, as nothing in circle B will contradict UNCLOS’s object or purpose. This understanding largely restricts the function of Article 281(1) and further limits the potential for voluntary dispute settlement under Article XV. Ultimately, this makes the so-called compatibility unidirectional, as the arrow in Figure 2 points outward.

Imagine reasoning starting with a parallel treaty. The exception-in-exception mode becomes an exception-to-principles mode when parties incorporate a regional or bilateral agreement compatible with UNCLOS Articles into the UNCLOS framework. This parallel treaty will remain compatible with UNCLOS if it does not contradict its object and purpose. This compatibility (Figure 2) works in two ways. According to the Commission, any voluntary arrangement chosen by the parties (circle B) must remain completely within the framework of UNCLOS (circle A). The smallest circle will disappear, as nothing in circle B will contradict UNCLOS’s object or purpose. This understanding largely restricts the function of Article 281(1) and further limits the potential for voluntary dispute settlement under Article XV. Ultimately, this makes the so-called compatibility unidirectional, as the arrow in Figure 3 points outward.

Figure 3. Sections (2) and (3) of Article 311 are phrased in the exception-in-exception mode. They appear in UNCLOS, where exceptions can derogate some UNCLOS articles. The second exception is to prevent that derogation from affecting the purpose, object, or basic principles of the convention. What derogation means in theory, as Figure 2 shows, is that some part of circle (B) (the relevant agreement for Article 281) may move out of circle (A) (the Convention) and that this partial exception is acceptable as long as it does not fall into the second exception (the smallest circle SC, representing the provisions against the object and purpose). (C) is the point at which Article 311 came into play. Imagine reasoning starting with a parallel treaty. The exception-in-exception mode becomes an exception-to-principles mode when parties incorporate a regional or bilateral agreement compatible with UNCLOS Articles into the UNCLOS framework. This parallel treaty will remain compatible with UNCLOS if it does not contradict its object and purpose. This compatibility (Figure 2) works in two ways. According to the Commission, any voluntary arrangement chosen by the parties (circle B) must remain completely within the framework of UNCLOS (circle A). The smallest circle will disappear, as nothing in circle B will contradict UNCLOS’s object or purpose. This understanding largely restricts the function of Article 281(1) and further limits the potential for voluntary dispute settlement under Article XV. Ultimately, this makes the so-called compatibility unidirectional, as the arrow in Figure 2 points outward.

What are the objectives and purposes of UNCLOS as a benchmark? For instance, it is easy to imagine a circumstance in which parties with geo-economic relationships agree to exploit the marine resources of adjacent marine areas in a manner different from the relevant regimes in UNCLOS, and it is difficult to imagine a scenario in which one State party gives up almost all of its essential interests in a submissive gesture. Nevertheless, parties cannot use Article 311 to justify unequal treaties, as they would easily fall into the second exception. Unequal provisions go against “the maintenance of peace, justice and progress of all” and the basic principles of “strengthening security, cooperation and friendly relations” in UNCLOS’s Preamble. The significance of the non-derogation requirement lies in maintaining regional and bilateral agreements, including unequal provisions. In Article 311, unequal treaties derogate protected non-derogatory values. Compatibility complements the equality tests for voluntary settlements in Article 281.

4.2 A divergent “voice” from other GGBs: possibly dual-directional

In contrast to Article 281, few decisions have discussed Article 311, as noted above, but these limited rulings also represent a strong value in making comparisons, comparing the similar rulings to the potential counterarguments. This part goes into other opinions on Article 311, as it was conducted above on Article 281 in Section 3 above. The Southern Bluefin Tuna case is the only one that has analyzed a parallel agreement in the context of Article 311, and the tribunal drew its conclusions based partly on that analysis. At least one other case addressed issues concerning the relationship between the Convention and other sources of international law, such as whether historical rights were compatible with the UNCLOS regime. Regarding the relationship between Articles 281 and 311, the history of judicial decision-making under UNCLOS’s compulsory proceedings is almost blank. Some cases did not involve parallel treaties or raise issues relevant to compatibility; in others, the GGBs were reluctant to speak to the subtle and complicated link between the two articles, even when voluntary settlement and compatibility were directly at issue. Nonetheless, we can extrapolate the tribunals’ positions from their rulings without explicit statements. This section analyzes previous Article 311 decisions, especially regarding compatibility, to understand the GGBs’ view of the relationship between Articles 281 and 311.

4.2.1 Existing ruling on Article 311

Article 311 defines how a treaty derogates UNCLOS’s terms and the extent to which a derogation is compatible with UNCLOS. Of the existing rulings concerning jurisdiction and admissibility, the Southern Bluefin Tuna case offers only an analysis of Article 311. Japan, Australia, and New Zealand agreed that the 1993 CCSBT was compatible with UNCLOS. However, they disputed whether the CCSBT was a treaty derogated from UNCLOS. To some extent, this disagreement represents a divergence in their interpretations of “compatible” in Article 311. Japan believed that the CCSBT should prevail as a lex specialis and regarded the compatibility requirement in Article 311 as evidence supporting this analysis. In Japan’s view, the list of procedures in Article 16 of the CCSBT constitutes a derogation with no detraction of other parties’ enjoyment of rights under UNCLOS. According to Australia and New Zealand, the CCSBT is compatible with UNCLOS. Still, there is no indication in travaux (the materials regarding the parties’ preparation when they negotiate a treaty) that Japan intended to opt out of the UNCLOS dispute settlement.

The focal point of the parties’ controversy was whether a parallel treaty “compatible” with UNCLOS could justify a derogation from the compulsory proceedings. Australia and New Zealand emphasized that the CCSBT is compatible but not a treaty derogating from UNCLOS since they did not agree with those in negotiations. Japan claimed that as long as the CCSBT is compatible with Article 311, derogation is automatically permitted based on the parallelism of jurisdiction. The arguments of Australia and New Zealand imply that the explicit exclusion of further procedures is proof of agreement on derogation in negotiations. Articles 281 and 311 are linked because the terms of exclusion in the former might serve as evidence of an agreement on derogation in the latter. Japan’s argument that an agreement on derogation can be presumed based on the parallelism of jurisdictions amounts to saying that an implicit exclusion of the compulsory proceedings in UNCLOS in its parallel treaty is enough to prove its agreement on derogation.