- 1Law School, Shanghai Maritime University, Shanghai, China

- 2Department of Law, Korea University, Seoul, Republic of Korea

The possession of the paper B/Ls is the basis of the function of a B/L as a document of title in common law systems and the delivery effect of B/Ls in civil law systems. The “possession problem” of eB/Ls is how to ensure that eB/Ls, as intangible objects, continue to have this basis. In the international level, the MLETR creates the concept of “control” of electronic transferable records as a functional equivalent to possession of paper B/Ls. Although the CMI Rules and the Rotterdam Rules involve control, neither of them makes specific provisions for control. In the national level, there are three solutions to the “possession problem”: First, expand the objects of possession to cover eB/Ls, such as the United Kingdom. Second, adopt the same approach as the MLETR, creating a concept of control as a functional equivalent of possession, such as Singapore and Japan, which is in the process of legislating, as well as Abu Dhabi Global Market and other 6 jurisdictions which have directly transplanted Article 11 of the MLETR. Third, establish a central registry system so that possession of eB/Ls does not have to be demonstrated. A typical example is South Korea, where the legislation on eB/Ls preceded the MLETR. The revision of Chinese Maritime Code currently does not pay sufficient attention to the “possession problem” of eB/Ls. The countermeasure should be to first stipulate the delivery effect of paper B/Ls, and then provide a solution to the “possession problem” of eB/Ls.

1 Introduction

The revolution in information and communications technology and electronic communication and processing has profoundly affected most spheres of commercial activity. Although the shipping industry is in many ways conservative in terms of speed of change to its documentation and practices, e-commerce is of increasing importance (Aikens et al., 2021). Whether it is called electronic bill of lading (Korean Commercial Code), electronic transport record (the Rotterdam Rules), electronic bill of lading record (the Interim Draft for Reviewing Regulations Related to Bills of Lading, Japan), electronic trade document (the Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023, UK) or other terms, the electronification of bills of lading (hereinafter referred to as “B/Ls”) is one of the most important features of the current trend of digitalization in shipping industry, and it is also a direct result of the development of e-commerce in the shipping industry. However, after nearly 40 years of development, eB/Ls have not yet achieved widespread and stable application. One of the reasons the use of electronic commerce is not developing in line with technological capability is that there is little law governing its use. The exchange of data electronically does not itself pose a problem. However, when the data represents negotiable documents that cover valuable assets, an established legal structure is needed (Dubovec, 2006).

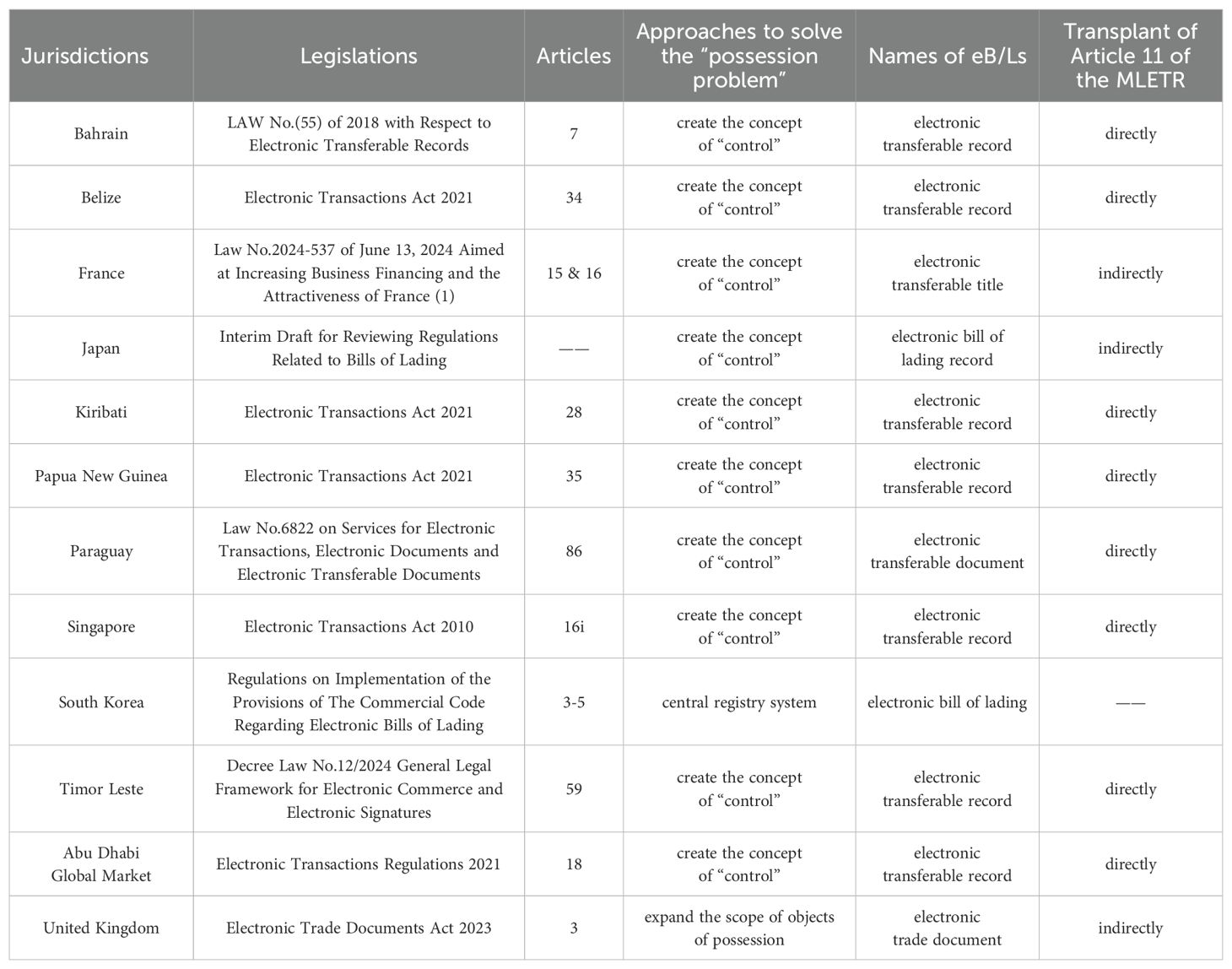

In response to this trend, the legislation of electronic bills of lading (hereinafter referred to as “eB/Ls”) has become the focus of both international and domestic maritime legislation since the 2010s. South Korea is the first country to enact special legislation for eB/Ls, and formulated the Regulations on Implementation of the Provisions of The Commercial Code Regarding Electronic Bills of Lading in accordance with the Korean Commercial Code in 2008. The UNCITRAL Model Law on Electronic Transferable Records (hereinafter referred to as “MLETR”) was adopted on 13 July 2017. The MLETR aims to enable the legal use of electronic transferable records (hereinafter referred to as “ETRs”) both domestically and across borders. The MLETR applies to ETRs that are functionally equivalent to transferable documents or instruments, including B/Ls. Until August 2024, legislation based on or influenced by the MLETR has been adopted in 10 jurisdictions, including Bahrain (2018), Belize (2021), Kiribati (2021), Paraguay (2021), Singapore (2021), Abu Dhabi Global Market of United Arab Emirates (2021), Papua New Guinea (2022), United Kingdom (2023), Timor Leste (2024) and France (2024). In addition, Japan is currently working on eB/Ls legislation based on the revision of Japanese Commercial Code and has published an interim draft.

Whether in common law systems or civil law systems, possession of the B/L is the basis for the B/L to be used as a transferable transport document in international trade. Due to the key characteristic of eB/Ls as intangible objects, how to maintain this basis when using eB/Ls has also become the focus and difficulty of eB/Ls legislation, which is called the “possession problem”. Although eB/Ls, as electronic information, should be the most transferable form of trade documents, but in terms of practicability, it is well known that the most cardinal drawback of the eB/L is the lack of negotiability. In contrast to the traditional B/L, whose negotiability is of great significance, the electronic bill is devoid of the particular feature on the ground that it is intangible. Especially at common law, the fact that the electronic bill is intangible means automatically that it is not negotiable, since negotiability derives from the bill’s qualification as a document of title (Ziakas, 2018). Based on the perspective of comparative law, this paper will analyze the legislation or legislative progress on the “possession problem” of eB/Ls in international maritime legislation and major jurisdictions, and compare it with the ongoing revision of Chinese Maritime Code.

2 Why is possession important?

The B/L originated, as its name would imply, as no more than a receipt issued to merchants as a copy from the entries in the ship’s books which were required to be kept by the ship by local law to evidence receipt by the carriers, in good condition, of cargoes laden on board their vessels (Bugden and Lamont-Black, 2013). But nowadays in international sales of goods, the most important value of the B/L is as a document representing the goods, which in the common law system is usually regarded as a document of title. This makes the B/L clearly distinguishable from other shipping documents such as sea waybills, as well as transport documents issued by rail, road and air carriers (often known as “consignment notes”), which are typically non-negotiable.

UNCITRAL is currently working on international legislation on negotiable cargo documents, which specifically explains why is there a demand for negotiable cargo documents and negotiable electronic cargo records. Documents of title can be transferred to another person, making it easier to buy and sell goods while in transit. This is particularly valuable in international trade where shipments can take some time or have to be reloaded during the voyage and the parties may wish to be able to sell or otherwise dispose of the goods for financial, operational, or strategic reasons. In addition, documents of title can provide better security for banks and financial institutions providing trade finance, such as the letter of credit. By becoming holders of documents of title, banks and financial institutions could exercise control over the goods. To sum up, documents of title can provide flexibility in international trade and can also facilitate the use of trade finance (United Nations Commission on International Trade Law, 2024). This makes documentary trade possible. The most important of these is that possession of the B/L is the basis for its transferability. Possession is a basic concept of property law in the civil law system, which means having actual control. And possession in common law systems means the fact of having or holding property in one’s power (Garner, 2019). It can be seen that there is no substantial difference between the concept of possession itself in the civil law system and the common law system.

2.1 Common law systems

In common law systems, serving as a document of title is one of the three functions of a B/L. Although some statutory laws do provide for the definition of “document of title”, such as Article 1(4) of Factors Act 1889 of UK and Article 1-201 of Uniform Commercial Code of USA, there is no authoritative definition of the document of title at common law, but it is submitted that in its original or traditional meaning the phrase refers to a document, the transfer of which operates as a transfer of the constructive possession of the goods covered by the document and may, if so intended, operate as a transfer of the property in them (Bridge, 2010). Therefore, the document of title is generally a document attesting title or possession (Greenberg, 2015), and the word “title” in document of title refers to the narrower concept of a right to possession (Rose and Reynolds, 2022). The ocean B/L is the only document of title to goods at common law presently recognized under the English common law. As such, the transfer of a B/L is capable of transferring to the transferee the constructive/symbolic possession of the goods (Aikens et al., 2021), and constructive possession means the control over a property without actual possession of it (Garner, 2019).

There are three purposes for which possession of the B/L may be regarded as equivalent to possession of the goods covered by it: (a) The holder of the B/L is entitled to delivery of the goods at the port of discharge. (b) The holder can transfer the ownership of the goods during transit merely by indorsing the B/L. (c) The B/L can be used as security for a debt. The development of the B/L as a document of title has been so successful that, over the years, it has come to exercise a tripartite function in relation to the contract of carriage, to the sale of goods in transit, and to the raising of a financial credit (Wilson, 2010). Therefore, possession of the B/L is the basis for the B/L to serve as a document of title. Therefore, the eB/L must establish the right of its holder to take possession of the goods. It must transfer rights and (where appropriate) liabilities under the carriage contract. It must be capable of transferring property, and the right to possess the goods. Crucially also though, if the carrier delivers goods against presentation, or if he refuses to deliver except against presentation, he should be protected from action, just as he is with a paper bill. Carrier defenses are problematic for an eB/L (Todd, 2019).

2.2 Civil law systems

In civil law systems, there are documents corresponding to documents of title, but a different approach is taken. The term “document of title” itself is alien to civil law systems, and it created serious difficulties as to how to translate this term into civil law systems (Pejović, 2020). The corresponding function of the B/L as a document of title in the civil law systems is the effect to property rights of the B/L, also known as the delivery effect of the B/L, which shows that the B/L is a document representing the right to request delivery of goods (Nakamura and Hakoi, 2013). For example, Article 524 of German Commercial Code provides that: “Provided the carrier is in possession of the goods, the transfer of a bill of lading to the consignee identified therein shall have the same effects, in terms of the acquisition of rights to the goods, as does the delivery of the goods for carriage.” Similar provisions can also be found in Article 763 of Japanese Commercial Code, Article 133 of Korean Commercial Code and many other jurisdictions.

In most jurisdictions of civil law systems, transfer of property rights of goods as movable properties requires the delivery of goods. For example, Paragraph 1 of Article 188 of Korean Civil Code provides that: “The assignment of real rights over movables takes effect by delivery of the Article.” Even the Japanese Civil Code, which adopts the principle of agreement, requires only the agreement between the transferor and transferee to transfer of property rights, also requires the delivery for the acquisition of movable property as a requirement without which the transferee shall not be able to assert a priority of his/her acquisition against a third party (Article 178) (Matsuo, 2021). However, if the goods in transit need to be resold, it is usually impossible to actually deliver them.

Possession at civil law systems means having actual control, and indirect possession is also recognized as possession (Chang et al., 2023). Based on the delivery effect of the B/L, possession of B/Ls is equivalent to indirect possession of goods, and delivery of B/Ls is also equivalent to symbolic delivery of goods, which can meet the delivery required in transfer of property rights of goods. This makes it possible to substitute delivery of goods with the delivery of B/Ls (Kobayashi et al., 2022). There are different theories on the delivery effect of B/Ls, such as Representation Theory, Strictly Relative Theory and Absolutely Theory. According to the Representation Theory as mainstream theory, possession of a B/L is also the basis for a B/L to have delivery effect. Therefore, there is no substantive difference between common law systems and civil law systems on this problem, and possession of B/Ls is the premise to play the value of negotiable cargo documents.

One of the legal difficulties of eB/Ls is that the traditional concept of possession requires actual control over the object. But the essence of an eB/L is information, and it does not have the physical form like a traditional paper B/L. For example, Article 2 of the MLETR provides that electronic record means information generated, communicated, received or stored by electronic means. Intangible objects are excluded from the scope of possession in most jurisdictions. This entails ensuring that the electronic document can embrace the notions of delivery and possession that are bound up in the paper version of B/Ls and which have established for centuries. Likewise, the use of B/Ls to transfer possession and pass property may be difficult to achieve electronically unless proper provision is made for this (Girvin, 2022). Functional equivalence is one of the basic principles of e-commerce legislation, and how to deal with the functional equivalence of possession is one of the key points of eB/Ls legislation.

3 Legislation on the international level

There are currently three international legislations closely related to eB/Ls, i.e. CMI Rules for Electronic Bills of Lading (hereinafter referred to as “CMI Rules”), United Nations Convention on Contracts for the International Carriage of Goods Wholly or Partly by Sea, (hereinafter referred to as “Rotterdam Rules”) and the MLETR. Neither the CMI Rules nor the MLETR are mandatory rules. The former are voluntary and are effective only when the parties contractually incorporate then, and the latter is a model law. The Rotterdam Rules have not yet come into effect. The concept that is functionally equivalent to possession in international legislations is usually “control”.

3.1 The CMI rules

Under the CMI rules, a Holder means the party who is entitled to the rights described in Article 7(a) by virtue of its possession of a valid Private Key (Article 2). The control is used in the term “right of control”, which includes a series of rights that the holder of a paper B/L has, including claim delivery of the goods, nominate the consignee or substitute a nominated consignee for any other party, transfer the right of control, instruct the carrier on any other subject concerning the goods in accordance with the contract of carriage [Article 7(a)]. In this sense, the “control” used by CMI rules refers to a substantive controlling rights over the goods (Jiang, 2023). Therefore, it is not or not only a functional equivalent concept to possession of B/Ls.

3.2 The Rotterdam Rules

The Rotterdam Rules were the first to create the concept of “electronic transport record” in the legislations on international transport of goods. Article 8(b) of the Rotterdam Rules sets out in terms the principle of equivalence, i.e. the principle that the “issuance, exclusive control or transfer of an electronic transport record has the same effect as the issuance, possession or transfer of a transport document”. The phrase “exclusive control” is nowhere defined but is used in the definition of the word “issuance” at Article 1.21, where “issuance” is defined as the “issuance of the record in accordance with procedures that ensure that the record is subject to exclusive control from its creation until it ceases to have any effect or validity” (Baatz et al., 2009). Nevertheless, exclusive control should be considered as a functional equivalent of possession.

The main obstacle to the transfer of electronic transferable transport documents is the need to create a way for the holder of a legitimate transfer to feel assured that there is indeed a document, that there are no defects on the surface of the document, and that the signature or other substitute is genuine and that the document is transferable. This approach makes control of the electronic document equivalent to physical possession of the paper document in law. Whether it is possession or control, the purpose is to avoid conflicts of interest between parties over the same goods. Two people cannot own a certain product or hold a certain transport document at the same time. Possession or control ensures the orderliness of the chain of transfer of goods and documents. The purpose of the Rotterdam Rules is to replace this function by establishing an electronic system that ensures that at any given point in time, only one person can exercise exclusive control over a negotiable electronic transport record by linking the transferability of the electronic transport record to established procedures. However, since the Rotterdam Rules do not specifically define “exclusive control”, they are unable to provide definitive guidance for commercial practices. In addition, the Rotterdam Rules have not yet come into effect, and the electronic transport record system established therein has also lacked the opportunity to be tested in practice.

In addition, the Rotterdam Rules also provide for a similar concept, i.e. the right of control of the goods, which consists of the right of disposal of the goods while in transit (Berlingieri, 2014). Although both contain the expression “control”, the object of control of eB/Ls is eB/Ls as information, while the object of the right of control is goods. The right of control applies to both situations where a paper B/L or an electronic B/L is issued. Therefore, the right of control and the control of eB/Ls are two completely different concepts.

3.3 The MLETR

The MLETR is the latest legal instrument proposed internationally as a way of enabling the use of electronic functional equivalents to negotiable instruments and documents of title, including eB/Ls. There are three main functional equivalence provisions laid down by the MLETR designed to enable this transition. Article 11 is one of them, which is the requirement that exclusive control be given over the electronic substitute and that the person in control be identifiable (Goldby, 2019). The concept of “control” is also one of the core concepts of the MLETR. Article 11 provides a functional equivalence rule for the possession of a transferable document or instrument. Functional equivalence of possession is achieved when a reliable method is employed to establish control of that record by a person and to identify the person in control. The concept of “control” is not defined in the MLETR since it is the functional equivalent of possession, which, in turn, may vary in each jurisdiction (United Nations, 2018).

It can be seen that the approach taken by the MLETR to solve the “possession problem” of eB/Ls is to create a new concept as the functional equivalent of possession, so as not to affect the concept of possession that has been formed in various legal jurisdictions over a long period of time. This option is obviously more feasible for international legislation than expanding the concept of possession or its scope of application.

Paragraph 1 of Article 11 provides that: “Where the law requires or permits the possession of a transferable document or instrument, that requirement is met with respect to an electronic transferable record if a reliable method is used: (a) To establish exclusive control of that electronic transferable record by a person; and (b) To identify that person as the person in control.” Paragraph 1(a) use the same expression “exclusive control” as the Rotterdam Rules, and the requirement for “exclusive” is obviously intended to correspond to the concept of possession. Paragraph 1(b) requires the person in control of the electronic transferable record to be reliably identified as such. The person in control of an electronic transferable record is in the same legal position as the possessor of an equivalent transferable document or instrument (United Nations, 2018), such as the B/L holder.

Paragraph 2 of Article 11 provides that: “Where the law requires or permits transfer of possession of a transferable document or instrument, that requirement is met with respect to an electronic transferable record through the transfer of control over the electronic transferable record.” Under this provision, transferring control of an eB/L will have the same effect as transferring possession of a paper B/L, which is also equivalent to symbolic delivery of goods. Therefore, the eB/L can have the function of the paper B/L as a document of title under the common law systems, as well as the delivery effect under the civil law systems.

In the current discussion, there is little criticism of the creation of the concept of possession, because from the perspective of the hypothetical effect, the concept of control is indeed an ideal choice and is also in line with the principle of functional equivalence in e-commerce legislation. This can be easily seen from the fact that many jurisdictions are currently following the MLETR. However, creating the concept of control is not difficult; all that is needed is a few lines of legislation. What is more important is how to implement control so that it can be effectively identified in practice and not apply overly cumbersome processes, because what international trade and shipping value most is transaction efficiency. It may be acceptable for the MLETR not to define controls, but the criteria for controls should be a key issue in ensuring that the control regime is effective. Although Article 12 of the MLETR has made some provisions on the general reliability standard, it is still only a principle provision in general, and its operability is still unknown. What is certain is that the identification of control, especially the implementation of the reliability standard, must be based on sufficient electronic information technology support, and the issues involved are probably far more complicated than the law.

4 Legislation on the national level

Among the jurisdictions that have completed or are in the process of enacting eB/Ls legislation, five jurisdictions deserve special attention. Firstly, South Korea was the first jurisdiction to enact domestic legislation on eB/L, and this was long before the MLETR, thus providing a perspective different from that of subsequent jurisdictions. Secondly, the United Kingdom and Singapore are typical common law jurisdictions. Thirdly, France is the only typical civil law jurisdiction among the countries that has enacted legislation based on the MLETR. Fourthly, as a typical civil law jurisdiction, Japan’s interim draft provides multiple options for most provisions. Most of the other jurisdictions that have enacted legislation based on the MLETR are not shipping countries, so the reference value is relatively small.

4.1 The United Kingdom

The law of England and Wales – like that of many other significant trade jurisdictions around the world – does not recognize intangible things as being amenable to possession. This means that electronic documents, which are considered to be intangible, cannot be possessed and therefore cannot presently function in the same way as their paper counterparts (Law Commission, 2022).

The UK has enacted the Electronic Trade Documents Act 2023 (hereinafter referred to as “ETDA”) as a separate act to regulate electronic trade documents including bills of lading. The ETDA did not directly transplant the provisions of the MLETR, but rather redesigned some provisions based on the purpose of the MLETR. According to the ETDA, a paper trade document is a document of a type commonly used in connection with trade in or transport of goods, or financing such trade or transport, and possession of the document is required as a matter of law or commercial custom, usage or practice for a person to claim performance of an obligation [Article 1(1)]. It can be seen that the requirement for possession is also one of the basic characteristics of the paper trade document that the electronic trade document is used to replace.

Article 3 of the ETDA provides that a person may possess, indorse and part with possession of an electronic trade document, and an electronic trade document has the same effect as an equivalent paper trade document. Anything done in relation to an electronic trade document has the same effect in relation to the document as it would have in relation to an equivalent paper trade document. This section is intended to remove the legal blocker that historically has prevented trade documents in electronic form from being possessed. As a result of this section, electronic trade documents are capable of possession (Great Britain, 2023). Therefore, the approach of the ETDA to solving the “possession problem” is different from the MLETR, and it does not create a new concept such as control that is functionally equivalent to possession, but chooses to expand the concept of possession so that its object can cover electronic trade documents that are intangible objects, including eB/Ls.

As the MLETR and the Rotterdam Rules do not provide for a definition of control, the ETDA does not set out what constitutes possession of an electronic trade document. Since possession is a relative and fact-specific concept, what constitutes possession of an electronic trade document in any particular context will be assessed as a matter of common law. The common law approach to establishing possession as a matter of fact considers two elements: factual control and intention. Who has possession of something at any one time will therefore depend on the type of control they have in respect of it and their intentions in relation to it, assessed against the control and intentions of other people who may also have a claim. Although existing case law concerning possession relates to tangible assets, many of the principles are capable of application to electronic trade documents (Great Britain, 2023).

4.2 Singapore

Singapore enacted the Electronic Transactions (Amendment) Act 2021 in February 2021, amending the Electronic Transactions Act 2010 (hereinafter referred to as “ETA”). The latter thus was inserted a new Part 2A “Electronic Transferable Records”. The ETA was first enacted in 1998 to provide legal certainty for digital transactions, which supports legal enforceability of electronic records and signatures, the ETA provides for the legal recognition of electronic records, and expressly allows for them to satisfy any requirement for writing in the written law (Hsu, 2021).

After the amendment, the ETA adopts most of the provisions of the MLETR, and the wording of most articles is basically consistent with the MLETR. According to Paragraph 2(a) of Article 16A of the ETA, in the interpretation of any provision of Part 2A, regard is to be had to the international origin of the MLETR and the need to promote uniformity in its application. Article 16B also provides that: “(1) This Part adopts the Model Law in its application to an electronic transferable record in accordance with the provisions of this Part. (2) Unless otherwise provided, nothing in this Part affects the application to an electronic transferable record of any rule of law governing a transferable document or instrument.”

Article 16I of the ETA basically transplants Article 11 of the MLETR, but an obvious difference is that it uses “Requirement for possession or transfer of possession” instead of “control” as the title. However, the actual term used in the article for ETRs is still “control”. Therefore, the ETA essentially still creates a new concept of “control” for eB/Ls as the functional equivalent of possession. According to the explanation in the Explanatory Note to the MLETR, the title of article 11 refers to “control” and not to “possession”, thus departing from the naming style of other articles of the MLETR, since the notion of “control” is particularly relevant in the MLETR. While a notion of “control” may exist in national legislation, the notion of “control” contained in article 11 needs to be interpreted autonomously in light of the international character of the MLETR (United Nations, 2018). Similar to MLETR, the ETA also does not specify the definition of control.

4.3 South Korea

After the revision of 2007, Article 862 of Korean Commercial Code is the provision on eB/Ls. Paragraph 1 provides that an eB/L shall have the same legal effect as a B/L. Paragraph 5 provides that: “Eligibility requirements for a designated registry agency of electronic bills of lading, electronic methods for the issuance and endorsement thereof, detailed procedures for receiving cargo, and other necessary matters shall be prescribed by Presidential Decree.” Thus Korean law first stipulates the basic validity of eB/Ls, while other specific issues regarding eB/Ls will be stipulated by Presidential Decree. This model can take into account both the efficiency and flexibility of legislation.

The Regulations on Implementation of the Provisions of The Commercial Code Regarding Electronic Bills of Lading (hereinafter referred to as “Presidential Decree”) took effect on August 4 2008, nearly a decade earlier than the MLETR, and has been amended for three times in May and November 2010 and March 2013. Based on the Presidential Decree, South Korea established a central registry system that is completely different from the MLETR. According to Article 3 to 5 of the Presidential Decree, the law recognizes only the registry method of granting exclusive control, because only eB/Ls managed in the electronic title registry set up by the law itself are granted functional equivalence. The operators of the system, Korea Trade Net (KTNET) and KL-Net, were selected by the Korean Ministry of Justice as the title registry in accordance with the Presidential Decree, under which the Ministry also has the authority to supervise the registry operator and audit its operations. Therefore, in order to be functionally equivalent to a paper B/L under Korean law, an eB/L must be registered in a quasi-public registry operated by a state-selected operator and supervised by the state (Goldby, 2019). When a carrier intends to issue an eB/L, he should transmit an application for issuance and registration by an electronic document, containing the required information, to a registry agency along with the carrier’s certified digital signature affixed thereon and a document (including an electronic document) that certifies that the shipper has consented to the issuance of the eB/L (Paragraph 1 of Article 6).

This model of central registry removes the need to create a functional equivalent of possession so as to determine the priority of various rights and obligations that accompany the electronic alternative to the document of title; in effect, this model creates an independent system governing the electronic alternative, and neither need, nor attempt, to fit the electronic alternative into the existing legal framework (Goldby and Yang, 2022). At the same time, there is a problem that there is no mechanism to guarantee the international convertibility even in the Presidential Decree. If the eB/L is involved in international trade, a foreigner should record it as a party in the title registry (Kim, 2017). This is actually a traditional problem in the electronicization of B/Ls. According to an admittedly outdated survey report commissioned by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) in 2003, the biggest obstacles to adoption included a need for more suitable infrastructure and market readiness, legal uncertainty, security concerns, high costs and confidentiality issues. In particular, the inability of users to trade with non-members, anyone who wants to use the eB/L must join a closed system and a group of participating members (Ioannou, 2023).

The advantage of the centralized registry system lies in fostering potential users’ confidence in the emerging system through state support (Goldby, 2019). Taking the Korea Trade Network (KTNET), one of the electronic bill of lading registration agencies designated by the Minister of Justice of South Korea, as an example, the KTNET system records each step of the circulation of electronic bills of lading to ensure their secure transfer. The record of rights transfer on the electronic bill of lading register has the legal effect of transferring rights, thus establishing the proprietary nature of the electronic bill of lading. However, some scholars in South Korea have highlighted drawbacks in the current centralized registry system. Notably, the closed nature of the electronic bill of lading system is seen as conflicting with the principle of technological neutrality and lacking in the concept and requirements based on functional equivalence (Lee, 2023). Moreover, as mentioned previously, the law does not provide a conversion mechanism for domestic electronic bills of lading recognized internationally. Consequently, foreign parties using electronic bills of lading in international trade must also register with South Korea’s centralized registry (Kim, 2017), creating inconvenience for international trade participants.

4.4 Japan

The transport and maritime sections of Japanese Commercial Code were revised in 2018, but eB/Ls are not included in the revision. The contents related to electronic transport documents focused on invoices and sea waybills. Paragraph 2 of Article 571 provides that: “In lieu of issuing an invoice, the shipper referred to in the preceding paragraph may provide the information that is required to be contained in an invoice by electronic or magnetic means (meaning a means of using an electronic data processing system, or of otherwise employing information and communications technology, which is specified by Ministry of Justice Order; the same applies hereinafter), with the carrier’s consent, pursuant to the provisions of Ministry of Justice Order. In this case, the shipper is deemed to have issued an invoice.” And Paragraph 3 of Article 770 also allows for the issuance of sea waybills by electromagnetic means. But this provision does not apply to B/Ls. Although electronic services provided by Bolero International Ltd and essDOCS Exchange Ltd have recently seen some use in the Japanese market mainly due to demand from shippers, their legal position is unclear as there are no provisions in the Japanese Commercial Code or publicized court precedents dealing with the subject (Kobayashi et al., 2022).

Japan launched the legislation on eB/Ls in April 2022, with the goal of regulating eB/Ls by amending laws including Japanese Commercial Code and the International Carriage of Goods by Sea Act, and the Interim Draft for Reviewing Regulations Related to Bills of Lading (hereinafter referred to as “Interim Draft”) was released in March 2023. Preparing an interim draft is a common legislative practice in Japan. The Interim Draft did not directly transplant the provisions of the MLETR, but instead amended the existing provisions of the Japanese Commercial Code and the International Carriage of Goods by Sea Act with reference to the MLETR, and added a few new provisions.

The formal name used in the Interim Draft for eB/Ls is “electronic bill of lading record”. Similar to the MLETR, the Interim Draft creates the concept of “control” as the functional equivalent of possession. The reasons are mainly in four aspects: (1) electronic records cannot be recognized as “things”, as defined as tangible things under the Japanese Civil Code, and therefore, they cannot be subject to possession; (2) it would be inappropriate to apply the concept of quasi-possession, such as for intangible property rights (bonds, patents, etc.), in governing the legal relationship involving electronic records, as it would complicate matters further; (3) it is necessary to conceptualize the state of exclusive control to recognize the functional equivalence between paper and electronic records; and (4) the adoption of the concept of control can be harmonized with the approach of the MLETR (Pejović and Lee, 2024).

The Interim Draft also creates the concept of control as a functional equivalent of possession, and provides two legislative options for the definition of control. According to the first option, control of an eB/L is defined as a state in which exclusive use can be made of the eB/L record. The second option does not set a legal definition for the control of eB/Ls, and the main considerations are three aspects: (1) The MLETR does not define “control”. (2) Although there are currently no examples of the use of the concept of control in relation to electromagnetic records in Japanese law, there are concepts such as “control of operations”, “control of activities” and “control of shipping” that are used to evaluate objects other than physical objects, and most of these laws do not define “control”. For example, Paragraph 3 of Article 7 provides that: “To control or interfere with the formation or management of a labor union by workers or to give financial assistance in paying the labor union’s operational expenditures;” (3) The term “exclusive right” is widely used in Japanese law for intellectual property rights such as patents and copyrights, which are intangible property rights. However, the law also does not define the concept of “exclusive right”, but instead leaves it to legal interpretation (Counselor’s Office et al., 2023).

4.5 France

Part II (Articles 14 to 17) of the Law No.2024-537 of June 13, 2024 Aimed at Increasing Business Financing and the Attractiveness of France (1) (hereinafter referred to as “Law No.2024-537”) is “Facilitating the International Growth of French Companies Through the Dematerialization of Transferable Securities”, which incorporates the main provisions of the MLETR. According to Article 14, a transferable security is a document that represents property or a right and that gives its bearer the right to demand performance of the obligation specified therein and to transfer this right, including B/Ls to order or to bearer governed by Section 2 of Chapter II of Title II of Book IV of Part V of the French Transport Code.

The Law No.2024-537 also created the concept of “control”. The provisions of Article 11 of the MLETR are reflected in Paragraph 2 of Article 15 and Paragraph 1 of Article 16 of the Law No.2024-537. According to these provisions, the bearer of the electronic transferable title is the person who has, for himself or for a third party, exclusive control over it. This control allows him to exercise the rights conferred by this title, to modify it or have it modified and to transfer it, under the conditions provided for in this title. The electronic transferable title has the same effects as the transferable title established on paper when it contains the information required for a transferable title established on paper and a reliable method is used to: (1) Ensure the uniqueness of the electronic transferable title; (2) Identify the bearer as the person who has exclusive control over it; (3) Establish the bearer’s exclusive control over this electronic transferable title; (4) Identify its signatories and successive bearers, from its creation until the time when it ceases to produce its effects or to be valid; (5) Preserve its integrity and attest to any modifications made to it, such as additions or deletions permitted by law, customs, usage or the agreement of the parties, from its creation until the time when it ceases to produce its effects or to be valid.

4.6 Other jurisdictions

Except for the United Kingdom, Singapore and France, the legislations on eB/Ls of other seven jurisdictions that have adopted the MLETR have all directly transplanted the provisions of Article 11 of the MLETR, and created the concept of control as the functional equivalent of possession.1 For a comprehensive overview of the current legislative status of electronic bills of lading across various countries and the influence of the MLETR, please refer to Table 1.

5 The “possession problem” in China

The revision of Chinese Maritime Code of 1992 began in 2017, and four formal drafts have been formed so far. The three drafts in March 2018, November 2018 and May 2020 only added electronic transport records as a type of transport documents parallel to B/Ls, but did not provide for the possession or control of electronic transport records.

The Revised Draft for Comments of April 2024 added Section 5 “Electronic Transport Records” to Chapter IV “Contracts of Carriage of Goods by Sea”, in which Article 85 provides that the electronic transport record issued by the carrier shall adopt a reliable method, and the fifth requirement of the reliable method is that the holder is able to prove his or her identity and have exclusive control over the electronic transport record. Apart from this, the Revised Draft for Comments does not define control or make other provisions for control. This provision is rather vague and does not seem to be sufficient to solve the “possession problem” of eB/Ls. Because under the MLETR, control is clearly defined as a functional equivalent to possession. Article 11, which specifically stipulates control, is also located in Chapter II “Provisions on functional equivalence”. Although Article 11 does have provisions regarding to use a reliable method, the emphasis of these provisions is still on the control of ETRs, which can meet the legal requirements for possession of transferable documents. At the same time, the transfer of control is equivalent to meeting the requirement of transfer of possession. The provisions concerning control in Article 85 of the Revised Draft for Comments fail to reflect such functional equivalence. In summary, requiring the electronic transport record issued by the carrier to ensure that the holder has exclusive control over the electronic transport record does not mean that the law gives the control of the electronic transport record the same legal effect as possession of the B/Ls. The electronic transport record cannot therefore have the function as a document of title.

In short, the control of eB/Ls can serve as the basis for the transferability of eB/Ls only if the law makes the same evaluation on the control of eB/Ls and the possession of paper B/Ls. Without such functional equivalence, it is meaningless to simply create the concept of control. The result may be that in practice merchants still cannot trust that eB/Ls can represent the goods like paper B/Ls, nor can they believe that transferring control of eB/Ls can transfer the rights to the goods.

One of the reasons for this situation is that Chinese law currently has no provisions regarding whether a B/L is a document of title or the delivery effect of the B/L. According to Article 71 of Chinese Maritime Code, a B/L is a document based on which the carrier undertakes to deliver the goods against surrendering the same, but this does not mean that a B/L is recognized as a document of title. At the same time, there has always been great controversy in China’s maritime law theory about the legal nature of B/Ls. Not only are there few discussions on the delivery effect of the B/L with reference to existing theories of the civil legal systems, but there is also no consensus on the corresponding meaning of document of lading in Chinese law. For example, in the famous Guiding Case No.111 of the Supreme People’s Court of China, namely, Liwan Subbranch, Guangzhou Branch of China Construction Bank Co., Ltd. v. Guangdong Lanyue Energy Development Co., Ltd. et al. (dispute over issuance of a letter of credit), the bank held the B/L based on the issuance of the letter of credit, but there was a dispute as to whether the bank enjoyed the ownership of the goods recorded in the B/L. The Supreme People’s Court held that a B/L had dual attributes including certificate of creditor’s rights and certificate of ownership, but it did not mean that the holder of a B/L would necessarily enjoy the ownership of the goods under the B/L. As for the holder of the B/L, whether it could obtain the real right and which type of real right it could obtain depended on the contractual stipulations of the parties. When the issuing bank holds the B/L in accordance with the contractual stipulations between it and the applicant, the people’s court should, in light of the characteristics of the letter of credit transactions, make reasonable interpretation of the contract involved and determine the true intentions of the issuing bank for holding the B/L.

Not stipulating the delivery effect or the nature as document of tile of the B/L would not have a significant impact on paper B/Ls. The reason is that the nature of bills of lading is the result of hundreds of years of international trade and shipping practices, and has a solid basis in merchant custom law. In practice, no one would deny that a bill of lading can represent the goods, whether the basis of this function is the effect of delivery or the document of title. However, eB/Ls are new things after all, and there is no such custom law basis. At this time, it is particularly important to find the basis for the transferability of paper B/Ls, because this is the object that the legislation of eB/Ls hopes to achieve functional equivalence.

Therefore, the significance of possession to the function of B/Ls is not clear under Chinese law, and the functional equivalence of possession will naturally not be taken seriously. It can even be said that the “possession problem” is still not a problem that has received sufficient attention under Chinese law. According to the first author’s experience in participating in the legislative work as a member of the Working Group of Revision of Chinese Maritime Code, the legislators do not deny that MLETR provides a set of generally effective legislative rules on eB/Ls. Including MLETR, UNCITRAL’s e-commerce legislations and the principles of non-discrimination against the use of electronic means, functional equivalence and technology neutrality established by UNCITRAL are indeed the most important reference blueprints for Chinese legislators. Unfortunately, the concept of the delivery effect of the B/L, which is common in the civil law system, is too unfamiliar to Chinese legislators and scholars, which has cut off the logical chain of directly transplanting the control regime stipulated in MLETR into Chinese law.

Based on the above situation, the revision of Chinese Maritime Code may need to first stipulate the delivery effect of B/Ls, and then provide a solution to the “possession problem” by expanding the object of possession to electronic transport records, or stipulating that control of electronic transport records is a functional equivalent of possession. The former is even more important than the latter. Regarding the former, it is recommended that the following provisions be made: “Delivery of a bill of lading for the purpose of transferring the ownership of the goods shall be deemed as delivery of the goods.” The delivery effect of the B/L is limited to the ownership of the goods here, mainly considering that Chinese Civil Code has clearly defined the pledge of the B/L as a right pledge, avoiding system conflicts between the Chinese Maritime Code and Chinese Civil Code. The provision can be placed after the current Article 71, that is, following the function of the B/L to stipulate the delivery effect of the B/L. The latter can directly transplant the provisions of Article 11 of the MLETR and appropriately integrate them with other provisions on eB/Ls. The key point is to emphasize that controlling an eB/L has the same effect as possessing a paper B/L, that is, delivering the B/L is equivalent to delivering the goods, and controlling an eB/L is equivalent to possessing a paper B/L, thereby achieving the delivery effect of the eB/L by two sets of equivalence. As for the specific standards of control, they can be handed over to administrative regulations formulated by the State Council or departmental regulations formulated by the Ministry of Transport. Such normative documents have greater flexibility in modification and can better adapt to the evolving electronic information technology.

6 Conclusions

From the above analysis, the following conclusions may be drawn:

1. The possession of the paper B/Ls is the basis of the function of a B/L as a document of title in common law systems and the delivery effect of B/Ls in civil law systems. The “possession problem” of eB/Ls is how to ensure that eB/Ls, as intangible objects, continue to have this basis.

2. In the international level, the MLETR creates the concept of control of electronic transferable records as a functional equivalent to possession of paper B/Ls. Although the CMI Rules and the Rotterdam Rules involve control, neither of them makes specific provisions for control.

3. In the national level, there are three solutions to the “possession problem”: (a) Expanding the objects of possession to cover eB/Ls, such as the United Kingdom. (b) Adopting the same approach as the MLETR, creating a concept of control as a functional equivalent of possession, such as Singapore and Japan, which is in the process of legislating, as well as Abu Dhabi Global Market and other 6 jurisdictions which have directly transplanted Article 11 of the MLETR. (c) Establishing a central registry system so that possession of eB/Ls does not have to be demonstrated. A typical example is South Korea, where the legislation on eB/Ls preceded the MLETR.

4. The revision of Chinese Maritime Code currently does not pay sufficient attention to the “possession problem” of eB/Ls. The countermeasure should be to first stipulate the delivery effect of paper B/Ls, and then provide a solution to the “possession problem” of eB/Ls.

5. According to the current legislative trends in major jurisdictions and the demonstration model established by MLETR, it can be foreseen that solving the possession problem of eB/Ls by creating the concept of control will become the mainstream legislative model in the future. Even in South Korea, which adopts a central registration system, theorists and practitioners generally propose that the concept of control should be introduced as a functional equivalent to possession. However, creating a concept is only the beginning of establishing an effective possession regime. What is more important is to clarify the identification criteria for exclusive control and enable it to be judged more conveniently in business practices that always pursue efficiency. Among these, the support of electronic information technology is probably far more important than the law.

Author contributions

SS: Formal analysis, Supervision, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RH: Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare that no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ Including Article 7 of the LAW No.(55) of 2018 with Respect to Electronic Transferable Records of Bahrain, Article 34 of the Electronic Transactions Act 2021 of Belize, Article 28 of the Electronic Transactions Act 2021 of Kiribati, Article 35 of the Electronic Transactions Act 2021 of Papua New Guinea, Article 86 of the Law No.6822 on Services for Electronic Transactions, Electronic Documents and Electronic Transferable Documents of Paraguay, Article 59 of the Decree Law No.12/2024 General Legal Framework for Electronic Commerce and Electronic Signatures of Timor Leste and Article 18 of the Electronic Transactions Regulations 2021 of Abu Dhabi Global Market.

References

Aikens R., Lord R., Bools M., Bolding M., Toh K. S. (2021). Bills of lading Vol. 47 (London, UK: Informa Law from Routledge), 164.

Baatz Y., Debattista C., Lorenzon F., Serdy A., Staniland H., Tsimplis M., et al. (2009). Rotterdam rules: A practical annotation (London, UK: Informa Law from Routledge), 8–07.

Berlingieri F. (2014). International maritime conventions volume I: the carriage of goods and passengers by sea (London, UK: Informa Law from Routledge), 205.

Bugden P. M., Lamont-Black S. (2013). Goods in transit and freight forwarding (London, UK: Sweet & Maxwell), 133.

Counselor’s Office, Civil Affairs Bureau, Ministry of Justice (2023). Supplementary instructions of the interim draft for reviewing regulations related to bills of lading. (Tokyo, Japan: Shoji Homu), 20–21.

Dubovec M. (2006). The problems and possibilities for using electronic bills of lading as collateral. Arizona J. Int. Comp. Law 23, 465.

Goldby M. (2019). Electronic documents in maritime trade: law and practice Vol. 204 (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press), 332–333.

Goldby M., Yang W. (2022). Solving the possession problem: An examination of the Law Commission’s proposal on electronic trade documents. Lloyd’s Maritime Commercial Law Q. 605, 618.

Great Britain (2023). Electronic trade documents act 2023 explanatory notes (London, UK: The Stationery Office), 13.

Ioannou I. (2023). Is enabling legislation sufficient to promote the uptake of electronic paperless trading systems? 5–6, NUS Law Working Paper, 2023/017. Available online at: https://law.nus.edu.sg/cml/wp-content/uploads/sites/8/2023/06/CML-WPS-2304.pdf (Accessed November 14, 2024).

Jiang T. (2023). Regulating electronic bills of lading on a national level. J. Business Law 604, 610.

Kobayashi N., Hiratsuka M., Yamashita S., Miyazaki Y., Tadano Y. (2022). Transport law in Japan Vol. 100 (Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer), 104.

Law Commission (2022). Electronic trade documents: Report and Bill (London, UK: Law Commission), 78.

Lee U. (2023). Direction and analysis of electronic bill of lading legislation of major countries: focusing on the UK and Japan. J. Korea Maritime Law Assoc. 45, 171–221.

Matsuo H. (2021). Property and trust law in Japan (Alphen aan den Rijn, Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer), 137.

Pejović ČCheckt. a. e. (2020). Transport documents in carriage of goods by sea: international law and practice (London, UK: Informa Law from Routledge), 113.

Pejović Č., Lee U. (2024). Towards global legal recognition of electronic trade documents: control or possession? Texas Int. Law J. 59, 101.

Todd P. (2019). Electronic bills of lading, blockchains and smart contracts. Int. J. Law Inf. Technol. 27, 342. doi: 10.1093/ijlit/eaaa002

United Nations (2018). UNCITRAL model law on electronic transferable records Vol. 42 (New York, NY: United Nations), 43–44.

United Nations Commission on International Trade Law (2024). Fact sheet: UNCITRAL project on negotiable cargo documents. 102, A/CN.9/WG.VI/WP. Available online at: https://documents.un.org/doc/undoc/ltd/v23/101/20/pdf/v2310120.pdf (Accessed November 14, 2024)

Keywords: electronic bills of lading, possession, control, MLETR, functional equivalent, Chinese Maritime Code

Citation: Sun S and He R (2024) How to possess an electronic bill of lading as information? A comparative perspective of the legislation on the “possession problem” of electronic bills of lading. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1493647. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1493647

Received: 09 September 2024; Accepted: 04 November 2024;

Published: 21 November 2024.

Edited by:

Yen-Chiang Chang, Dalian Maritime University, ChinaReviewed by:

Qiuwen Wang, East China University of Political Science and Law, ChinaBarbara Stępień, Jagiellonian University, Poland

Copyright © 2024 Sun and He. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Ran He, aGVyYW4wMTI5QGtvcmVhLmVkdQ==

Siqi Sun

Siqi Sun Ran He

Ran He