- College of Forestry, Wildlife, and Environment, Auburn University, Auburn, AL, United States

Coastal and ocean management in the United States is a complex issue requiring an equally complex management policy. Federal policy has historically been carried out in a siloed (sector-by-sector) fashion causing inefficient and bureaucratic management by federal agencies. The Obama administration took a novel approach to coastal and ocean management by signing an executive order that brought together federal agencies and empowered regional stakeholders, creating a first of its kind comprehensive National Ocean Policy. In 2018, former President Donald Trump rescinded the Obama-era policy and enacted his own version of National Ocean Policy that shifted authority to the states and focused on the economic potential of American waters. This research addresses a significant challenge in federal management of a complex natural resource. Here we identify common management strategies between different administrations to provide insights for future attempts at National Ocean Policy. We collect policy documents, press releases, and congressional testimony from high-level stakeholders and identified the most common themes over a 12-year period from 2009-2021. We find three common themes between the administrations even though their policies varied in strategy and scope: 1) the importance of a strong and enduring marine economy, 2) creating a strategic and efficient ocean policy, and 3) devolving authority from the federal government to state and regional decision-makers. We argue that coastal and ocean management via executive order is too easily rescinded to have a lasting impact. These novel findings highlight potential strategies for bipartisan cooperation in future attempts at National Ocean Policy.

Introduction

The creation of the National Ocean Policy in the United States (U.S.) was unprecedented, addressing a significant gap in the American policy system–the lack of a single, unified strategy to manage coastal and ocean ecosystems. The coastal U.S. is home to one of the world’s longest coastlines, largest economies, and largest populations in the world. If the country’s coastal counties were their own country, they would have the world’s third largest economy and would make up 40% of the country’s population (Economics and Demographics, n.d). And yet, there has never been a comprehensive policy for managing the coastal and ocean ecosystems prior to the Obama administration.

The National Ocean Policy would balance diverse interests like biodiversity conservation and economic development. To develop the administration’s policy priorities, former president Barack Obama’s administration created the Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force (hereafter “Task Force”). The Task Force engaged the American public through an unprecedented 180-day online comment period, six regional public meetings, and 38 expert roundtables (The White House Council on Environmental Quality, 2010). This process synthesized approximately 5,000 public comments and expert input, ultimately sending the Final Recommendations Of The Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force to the president in 2010. Upon receipt of the Task Force’s final recommendations, and building off eight years of progress made by the George W. Bush administration1, Obama signed Executive Order 13547 Stewardship of the Ocean, Our Coasts, and the Great Lakes (hereafter National Ocean Policy).

Historically, coastal and ocean policy in the United States has been carried out in a siloed way. Federal agencies often implement laws and policies pertinent to their mandate without communicating with other agencies working in the same geographical ocean space or without sharing technical expertise and other resources to facilitate cohesive management. The first major ocean policy was the Coastal Zone Management Act of 1972. The act allowed for states to voluntarily participate in a partnership with the federal government for the purpose of “protecting, restoring, and responsibly developing” the coastal and ocean environment (NOAA Office for Coastal Management, n.d). The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration administers the Coastal Zone Management Act highlighting the siloed nature of previous management strategies.

In 2004, President Bush released the U.S. Ocean Action Plan, which outlined 88 goals and priorities to “better coordinate U.S. ocean policy” (U.S. Department of Interior, 2004). While it did aim to increase funding for ocean science research and broadly discussed conservation, it failed to explicitly describe how conservation would happen. Additionally, it failed to describe how the plan would balance competing uses and a changing climate. The plan broadly mentioned establishing partnerships with state, local, and tribal governments, but did not explicitly state who would have management and decision-making authority. Bush’s plan was never implemented via executive order, nor did it ever make its way through the legislative process.

Given how recent and unprecedented the creation of National Ocean Policy was, and the changes that it underwent between the Obama and Trump administrations, our research asks the following question: how has National Ocean Policy changed in the U.S. from the recommendations made by the Task Force in 2009 and its subsequent implementation in the Obama and Trump administrations? Understanding how ocean policy changes between presidential administrations is essential for understanding modern nuances of American natural resource policy, concentrated in the executive branch and implemented by federal agencies.

The Obama-era National Ocean Policy and the subsequent Trump Administration’s policy were both implemented via executive order. Executive orders are a unique way of implementing policy priorities. They have become more commonplace and stand in contrast to the way that we normally define lawmaking (e.g., the Endangered Species Act enacted through the Congressional lawmaking process in 1973) (University of California Santa Barbara, 2023). In the U.S., executive orders are policies that manage operations of the federal government, specifically the agencies that make up the executive branch. Executive orders are not the same as legislation passed through Congress and Congress cannot overturn them (American Bar Association, 2021). The U.S. Constitution does not explicitly mention a presidential power to issue executive orders (Rudalevige, 2021). In a political era of increasing polarization in which legislative action in Congress is harder to achieve, executive orders are one way to bypass gridlock (Rudalevige, 2021). Because the National Ocean Policy was created and then changed via executive order, our paper studies the difference in these policies between two presidential administrations beginning with the Obama Administration and following changes through the Trump administration.

Data and analysis

This research adopts a case study design because it covers contemporary events and relevant behaviors that cannot be manipulated (Yin, 2017). Case studies allow for the consideration of many kinds of evidence: documents, artifacts, interviews, and direct observations (Yin, 2017). We analyze changes and differences to the National Ocean Policy between the Obama and Trump administrations. We do this as a comparative case study between the administrations and use comparative analysis according to theoretically relevant variables, which include varying priorities in National Ocean Policies (Yin, 2017). We use the priorities of the National Ocean Policy of the Obama administration as a case of ocean policy priorities for the Democratic Party and compare that to the priorities of the National Ocean Policy of the Trump Administration and the Republican Party.

We adopt Framing Theory to determine the policy priorities of decision-makers. We use Framing Theory as an approach for investigating diverse policy priorities between the Obama and Trump administrations. Framing Theory instructs us on how to characterize the presentation of issues from multiple perspectives (Chong & Druckman, 2007). It sheds light on how politicians emphasize certain aspects of a policy, while purposely excluding other aspects, which might lead to people interpreting issues differently (Borah, 2011; Ardèvol-Abreu, 2015). Framing Theory illustrates policy priorities because policy-makers frequently choose the frame that is consistent with their values or principles (Chong and Druckman, 2007). Framing Theory therefore helps us to compare competing Democrat and Republican policy priorities for National Ocean Policy. The way that issues are framed appeals to the partisan beliefs of the audience (Chong and Druckman, 2007). Politicians will often frame issues along certain lines in an attempt to mobilize voters. They accomplish this by highlighting very specific aspects of an issue that appeals to certain values (Jacoby, 2000). Frames in communication also serve as a way to promote certain definitions and interpretations of policies, which we use as a proxy for priorities (Shah et al., 2002).

Most literature on Framing Theory details how the media frames issues (Carragee and Roefs, 2004). De Vreese and Lecheler (2016) note that public policies and politics can be defined in different ways by traditional news media. There is a gap in the literature into how different types of political actors (e.g., politicians, organizations, or social movements) create and use frames to their benefit (Borah, 2011). Our research aims to fill that gap as well as a case-related gap, analyzing how politicians, government officials, various private and public organizations, and news outlets frame ocean management issues in the U.S.

To compare policy priorities, we used qualitative methods to characterize priorities in policy-maker statements. We collected and analyzed the statements of policy entrepreneurs (e.g., members of Congress, NGO leaders, private sector actors, and federal and subnational government leaders) when describing National Ocean Policy priorities from 2009 to January 2021, just before President Joseph Biden took office2. Additionally, we analyzed the policy documents associated with National Ocean Policies that were published by federal agencies and the White House. To collect the statements, we searched the Nexis Uni database using specific keywords and collected official policy documents from the archived documents on each administration’s websites. As of the date of this writing, Trump’s executive order is still an active order.

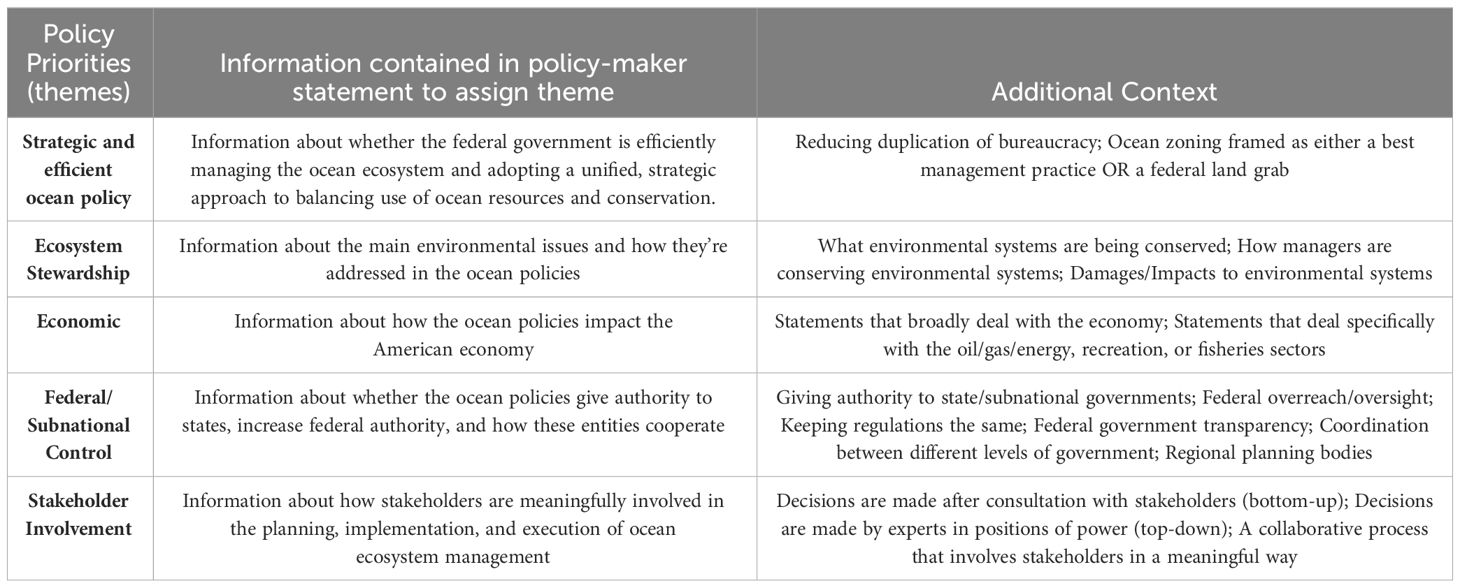

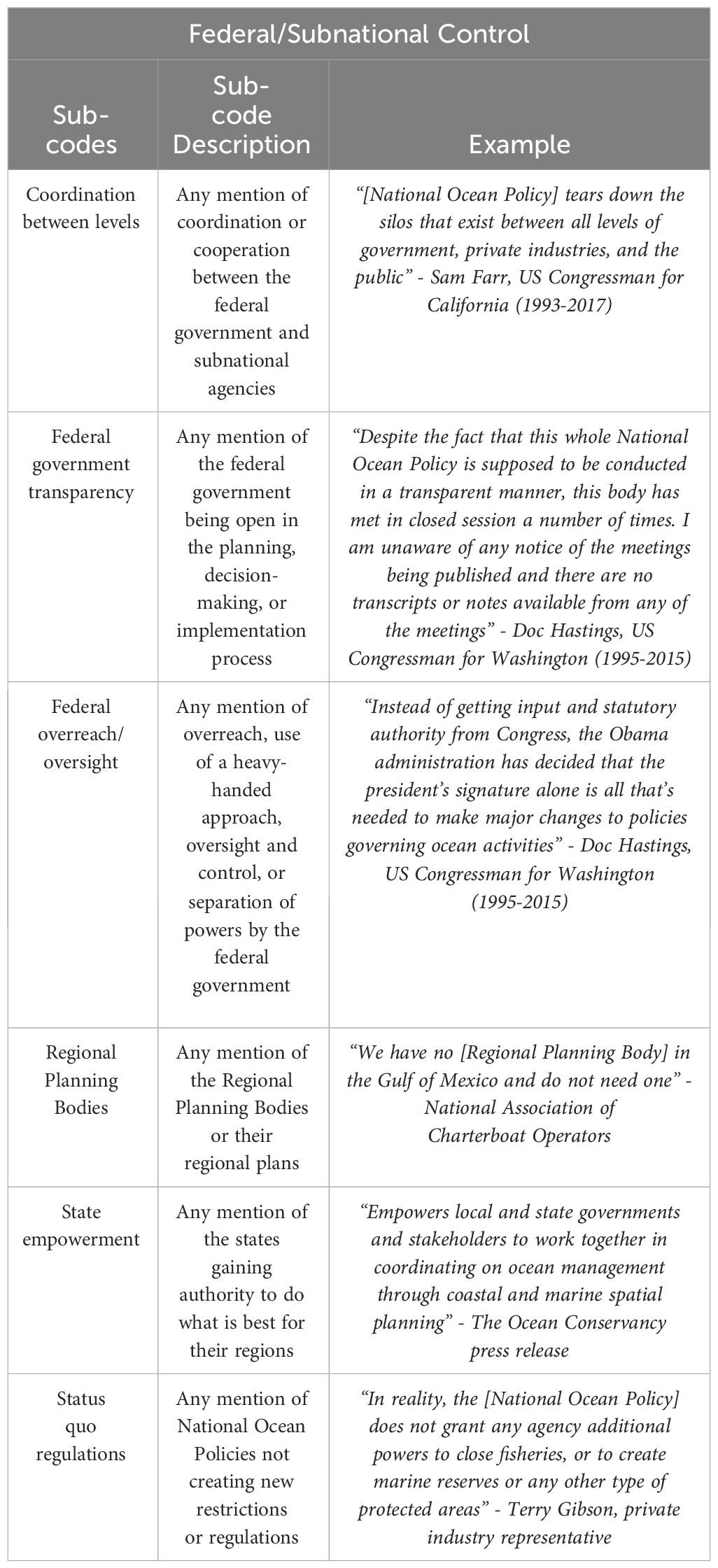

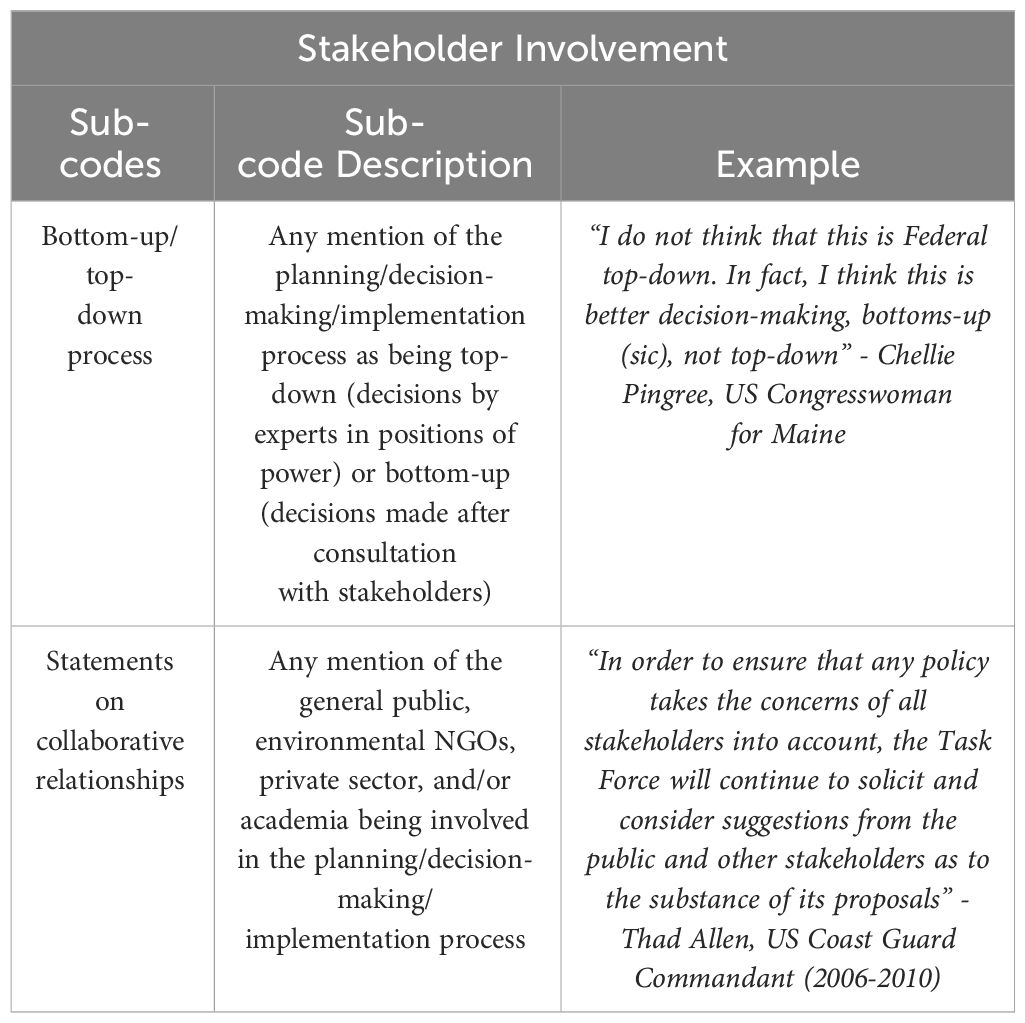

We used the Grounded Theory Methodology to code data that were separated into five main policy priorities (Table 1). Grounded Theory Methodology involves the construction of codes and categories directly from the collected data and “not from preconceived logically deduced hypotheses” (Charmaz, 2014). Inductive coding was used during this research as a way to find “emergent, data-driven” codes (Saldaña, 2015). We used the In Vivo coding method which uses the exact words and phrases from speakers and not the researchers’ interpretations of speakers’ words (Saldaña, 2015). After separating statements by policy priorities, we further separated each policy priority by what we refer to as sub-codes (more specific policy priorities). This categorization of data pairs well with Framing Theory because it highlights emphasis frames in the data. We use an emphasis frame to investigate how policy priorities are thematically portrayed, which help to provide a clear picture of the problems that were addressed by the two policies (Shulman and Sweitzer, 2018). After categorizing statements into sub-codes (n=20) (e.g., oil, gas, and energy as a specific policy priority of the economic broad policy priority), we were able to highlight in detail the focus of each message in the broader context of Framing Theory. We also employed the Focused Coding Method, a second cycle method that commonly follows In Vivo coding (Charmaz, 2014; Saldaña, 2015). Focused Coding is a way to find the most important or frequently used codes to develop the most important categories. This enabled us to theorize how ocean policy changes in the U.S. between Democrat and Republican administrations.

This process was a multiple coder effort. The lead researcher and first author coded 250 data points and four other researchers coded the remaining 198 data points after receiving detailed instruction and having access to the codebook. As the four additional researchers were coding data, the first author coded every tenth observation separately to check for intercoder reliability. Additional information on how we obtained intercoder reliability and quality control methods on our data can be found in Appendix 1.

Findings

Data summary

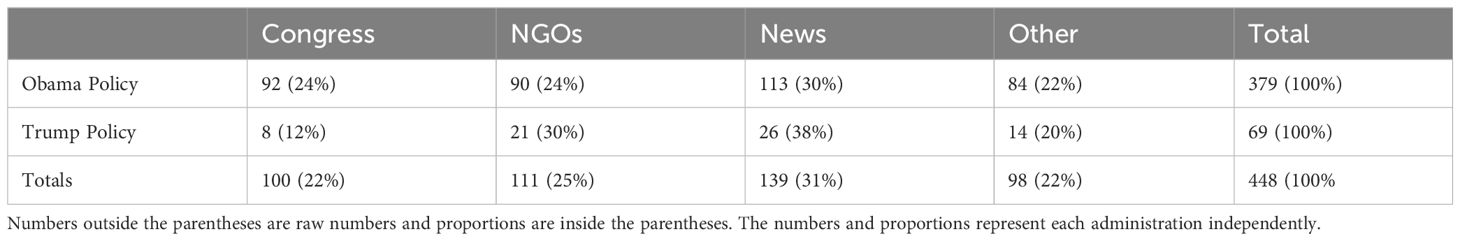

We compiled n=448 statements from policy-makers, of which n=379 were from the Obama-era policy and n=69 were from the Trump-era policy. Obama-era policy statements occurred between 2009-2018 and Trump-era policy statements between 2018-2021 (the end of the study period). The Obama-era policy statements occurred outside his administration because the policy remained active until the Trump-era policy was implemented in 2018.

The three largest sources of messages from both administrations came from Congress (e.g., testimonies, committee hearings, and opening statements by members of Congress), NGOs (e.g., press releases), and news outlets (see Table 2). Most of the NGOs focused on the environment, but some focused on economic and private business issues. The majority of the news outlets were national news sources such as the Associated Press, but there were also state and local news outlets represented. Sources of messaging during the Obama-era policy were evenly distributed between the three primary sources. Sources of messaging during the Trump-era policy were skewed towards news articles. The amount of Congressional messaging between the two administrations was significantly different (p-value=.004) Congressional stakeholders mentioned the Trump-era policy in n=8 (12%) of the total messages, while Congressional stakeholders doubled that percentage for the Obama-era policy (n=92, 24%).

Qualitative findings: policy priorities shared between administrations

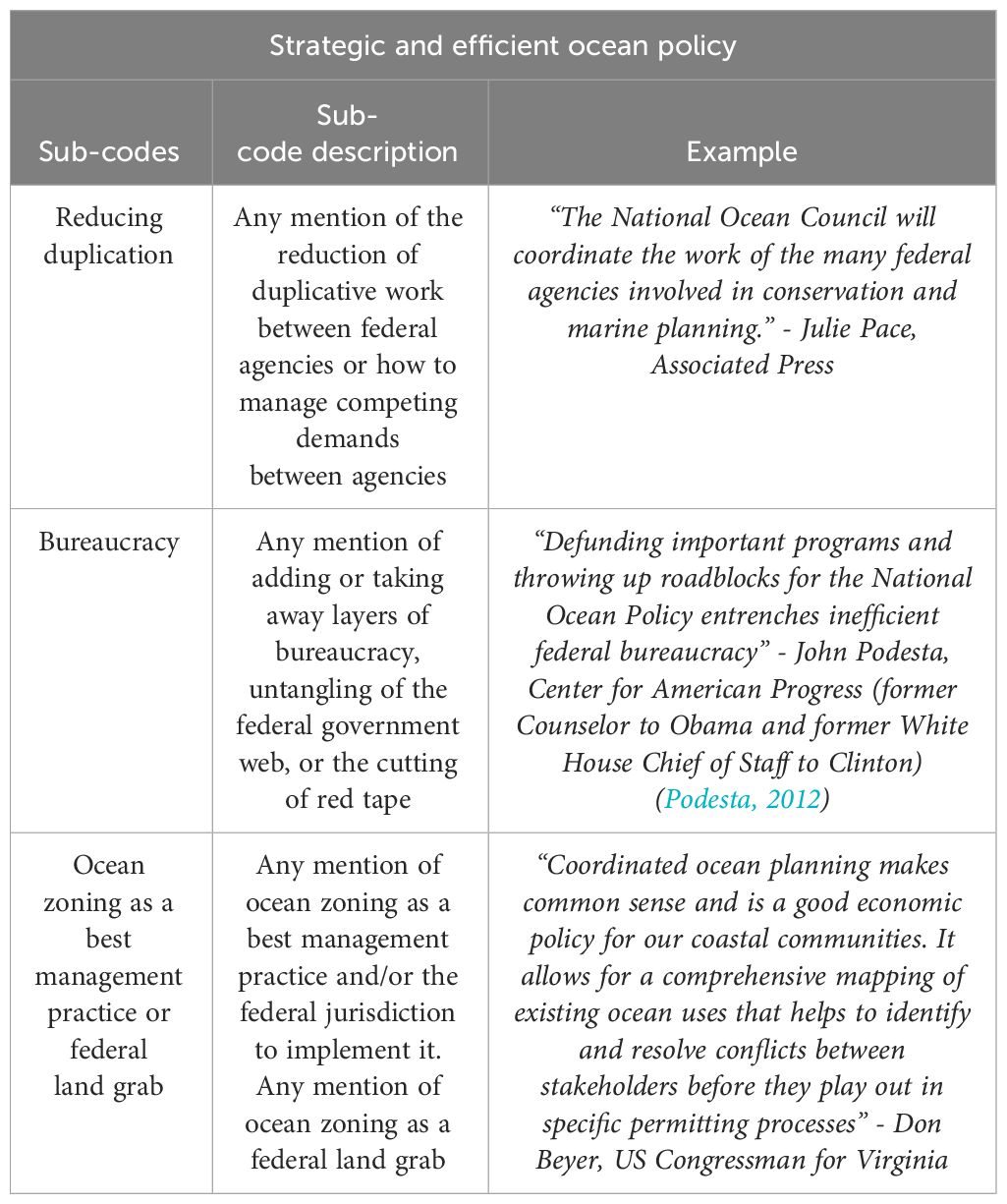

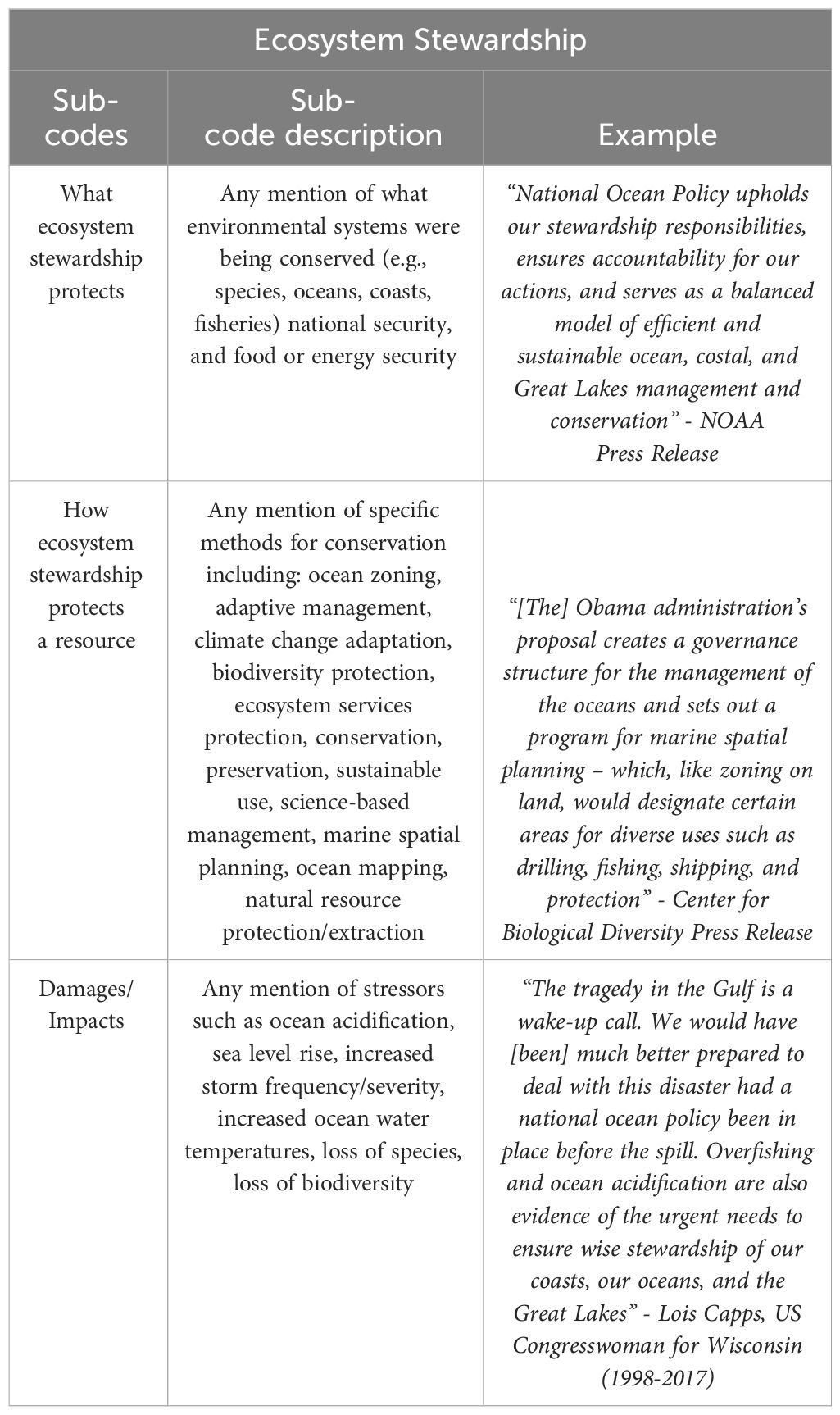

We identified five policy priorities shared between both administrations in the qualitative data, and explored differences in later quantitative data. The five policy priorities of the U.S. National Ocean Policy include: 1) strategic and efficient ocean policy, 2) ecosystem stewardship, 3) economic, 4) federal vs. subnational control, and 5) stakeholder involvement. These policy priorities and the sub-codes appear in Appendix 2 with more detailed definitions and examples.

National ocean policy and anticipatory management

The Obama-era policy focused on balancing its core policy priorities of strategic and efficient ocean policy, ecosystem stewardship, stakeholder involvement, and the economy (Exec. Order No. 13547, 75 Fed. Reg. 43021, 2010). It did this by introducing its most signature policy priority and with it, the administration’s most sweeping political change: to make ocean policy anticipatory. The administration did this by creating a new policy system, intentionally designed to foresee social, economic, and environmental challenges, and make efforts in advance to mitigate environmental change and conflict between resource users. The Obama-era policy did this by creating Regional Planning Bodies. They were the power centers that made sure that the unique social, economic, and ecological.

aspects of each U.S. region would be prioritized in a management plan (The Nation’s First Ocean Plans, 2016).3 The plans formally describe how states will coordinate with each other, engage the public, and implement coastal and marine spatial planning. Historically, coastal and ocean policy was reactionary (e.g., the response to the Exxon Valdez spill off the coast of Alaska in 1989 and the Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill in the Gulf of Mexico in 2010).

The most important example of institutions for the shift to anticipatory management can be found in the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic Regional Planning Bodies. The Regional Planning Bodies gathered stakeholders in state, federal, and tribal governments; fisheries decision-making organizations from the regions; and representatives from private industry.4,5 Planning processes required public participation, the use of science in decision-making, and using an ecosystem-based approach to management that considers the whole system. Each region could plan and implement policies for regionally specific needs. For example, the Northeast’s Ocean Plan included attempts at balancing the world-famous Maine Lobster and New England scallop industries with competing interests such as infrastructure (e.g., port dredging) and science (e.g., seafloor mapping projects). An example from the Mid-Atlantic Ocean Plan was the need to balance the $18 billion-dollar yearly fishing industry with future plans for ocean-based wind farms. By including all relevant regional stakeholders, the plans allowed for more flexible management, tailored to regional and local needs, that anticipates environmental change and user conflict.

Implementing anticipatory public policy in such a complex coastal nation required an equally complex implementation document to coordinate across scales, jurisdictions, and sectors. The complex, multi-stakeholder process of anticipatory management was codified in the 2013 National Ocean Policy Implementation Plan. This plan provided direction to governments and was the product of three years of input from stakeholders. It focused on anticipating change and user conflict in five areas: 1) the ocean economy, 2) safety and security, 3) coastal and ocean resilience, 4) prioritizing local choices, and 5) the use of science in decision-making (National Ocean Policy Implementation Plan, 2013).

Policy changes during the Trump administration

The Trump administration effectively ended American efforts at anticipatory and comprehensive ocean planning at the federal level and with it eight years’ worth of policy prioritization of a unified approach to ocean management. The Trump administration shifted its focus squarely on economic policy priorities. Trump’s executive order eliminated seven key federal entities established by Obama’s executive order. The most important being the National Ocean Council because it was essential to enacting a unified approach to ocean management. The Trump-era policy also eliminated the core institution responsible for ocean planning: Regional Planning Bodies.6 Federal agency involvement was not prohibited explicitly from the Trump administration, but there was a lack of financial support and technical assistance was optional, which left states to accomplish planning on their own or abandon it altogether (Goelz, 2022). A memo was also published shortly after Trump’s executive order that formally revoked the National Ocean Policy Implementation Plan, all formal documentation that provided the step-by-step implementation procedures7, and the already approved regional Ocean Plans for the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic (Guidance for Implementing Executive Order 13840, Titled “Ocean Policy to Advance the Economic, Security, and Environmental Interests of the United States, 2018).

With the elimination of Obama’s National Ocean Council and other initiatives, Trump’s executive order began its shift to focusing on its policy priorities of economic growth, energy production, and national security. To accomplish this, the Trump-era policy created the Ocean Policy Committee. This committee was largely made up of components from the Department of Defense, economic advisors, and cabinet agencies. An example of the prioritization of economic development is found in Trump’s creation of a national strategy for mapping and exploring the Exclusive Economic Zone of the U.S. with the hope that untapped natural resources would be discovered for future extraction (Trump, 2019). As this committee did not produce an implementation plan similar to the Obama-era National Ocean Council’s plan, it is difficult to know how the policy was carried out aside from their mandated objectives contained in the executive order (Exec. Order No. 13840, 83 Fed. Reg. 29431, 2018).

At the point that Trump left office in January 2021, minimal analysis has been done on the accomplishments of the Trump administration executive order and minimal analysis comparing the two administrations, which the following data aims to address. To date, the Biden administration has begun implementing a number of ocean policies related to climate change and environmental justice. The Ocean Policy Committee under the Biden administration released its Ocean Climate Action Plan in March 2023. The plan focuses on three main goals: 1) creating a carbon-neutral future, 2) moving forward solutions that harness the power of coastal and ocean ecosystems, and 3) improving coastal community resilience by leveraging ocean and coastal nature-based solutions. Additionally, the Ocean Policy Committee released its Ocean Justice Strategy in December 2023. The strategy’s vision includes five main topics for addressed environmental justice concerns related to ocean and coastal uses: 1) equitable access to the benefits provided by coastal and ocean ecosystems, 2) meaningfully engaging with coastal and ocean stakeholders, 3) recognition of traditional ecological knowledge and the value derived from it in policy-making, 4) improvement of coastal and ocean education, and 5) application of an environmental justice lens in ocean and coastal research. Many of the Biden administration’s policies relate back to the Obama administration’s objectives, with more focus on environmental justice and stronger attempts at combatting climate change. This research cannot fully analyze the Biden administration’s policies due to time limitations.

Quantitative findings

We analyzed statistically significant differences between policy priorities of the two administrations (see Table 3), using the frequency of the different policy themes detected and coded as a proxy for policy prioritization in the two administrations. Statistically significant differences between the Obama and Trump administrations include policy priorities of 1) Strategic and efficient ocean policy (appearing in 48% of Obama Administration statements and 27% of Trump Administration statements, p=.001); 2) the economy (appearing in 23% of Obama Administration statements and 55% of Trump Administration statements, p=0.001), and 3) stakeholder involvement (appearing in 24% of Obama Administration statements and 9% of Trump Administration statements, p=.001). We conclude that the key changes to ocean policy between the two administrations were an Obama Administration’s focus on an anticipatory and efficient ocean policy as well as on stakeholder involvement. By contrast, the Trump Administration focused on economic uses of U.S. oceans.

Table 3 Number (and proportion) of policy themes detected between Obama and Trump policy entrepreneurs and statistical differences.

We found there to be no statistically significant difference between Obama and Trump administration focus on ecosystem stewardship (appearing in 45% of Obama Administration statements and 46% of Trump Administration statements). We also found there to be no statistically significant difference between Obama and Trump administration focus on federal versus subnational control.

Strategic and efficient ocean policy

The Obama administration prioritized strategic and efficient ocean policy more in its policy documents, with 48% of its statements focused on this issue versus 27% from the Trump administration, making it the most frequently used policy priority (n=202). That said, actual implementation of this priority, such as decreasing jurisdictional overlap and ensuring strategic and efficient ocean policy in the many agencies managing the oceans, was nearly indistinguishable between administrations. The following examples from our data show how creating an efficient, unified, anticipatory ocean policy was a challenge for both administrations. An example from the Obama administration on reducing duplication comes from a senior member of the National Ocean Council during Congressional testimony: “The [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] sits at the table with departments and agencies that have not traditionally been in close coordination on ocean issues” (Lubchenco, 2011). A similar example from the Trump administration comes from a White House press release that stated the Trump-era policy “would streamline coordination of the many government agencies that have an interest in the oceans by establishing a new interagency Ocean Policy Committee,” suggesting that there still remained significant progress to be made on this priority issue (Exec. Order No. 13840, 83 Fed. Reg. 29431, 2018).

Ecosystem stewardship

The Obama and Trump administrations prioritized ecosystem stewardship equally, with 45% of Obama-era statements and 46% of Trump-era statements focused on this issue. Ecosystem stewardship was the most frequently used policy priority alongside strategic and efficient ocean policy (n=202). Despite a similar level of prioritization within public policy documents, real differences existed in how the two administrations actually implemented ecosystem stewardship policies. The Obama administration enacted stewardship through its Coastal and Marine Spatial Planning Program, defined by a high-ranking Obama administration official as “[A program that] facilitates a thoughtful, inclusive approach to harmonizing uses and minimizing adverse environmental impact” and that it would “replace the stove-piped, reactive approach now in place” (Lubchenco, 2011). Conversely, the Trump administration focused on managing ocean and coastal ecosystems to increase economic benefit and national security. An example of this goal was the Trump administration’s efforts at conducting scientific exploration of the ecosystems of the sea floor of the U.S. Exclusive Economic Zone to better understand American natural resources at sea.

Economy

The Trump administration prioritized the economy more in policy documents, with 55% of its statements focused on this issue versus 23% from the Obama administration. Additionally, implementation of economic policy priorities were also very different, albeit with one important overarching theme between the two administrations. Both administrations made it clear that they understood the importance of a healthy and robust ocean and coastal economy for the U.S. economy broadly. The differences rest in how the two administrations achieved that goal. The Obama administration focused on finding a way to balance economic growth with conservation. A private business representative in Congressional testimony highlights this priority by stating that the Obama-era policy “seeks to promote industry development that is sustainable and complements the variety of development activities already occurring in the ocean” (Lanard, 2016). Conversely, The Trump administration was focused on increasing offshore oil and gas drilling to become energy independent and increase U.S. security. A representative example of this priority comes from the executive order that states “domestic energy production from Federal waters strengthens the Nation’s security and reduces reliance on imported energy” (Exec. Order No. 13840, 83 Fed. Reg. 29431, 2018).

Federal and subnational control of ocean and coastal management

The Obama and Trump administrations prioritized federal versus subnational control of ocean and coastal management in similar ways in our review of public-facing policy documents, with 42% of Obama-era statements and 32% of Trump-era statements focused on this issue. Additionally, it was the third most frequently used policy priority in all of the data. The differences were, again, in how the two administrations actually implemented policy priorities. The Obama administration increased coordination between scales of government by creating the Governance Coordinating Committee. A representative example from a member of Congress stated that because of the Obama-era policy “for the first time ever, [states are] working with each other and with the federal government to better coordinate” (Natural Resources Defense Council, 2016). The Trump administration’s main policy priority was shifting authority on ocean-related matters back to the states. To accomplish this, the Trump-era policy disbanded the Governance Coordinating Committee. The Trump-era policy has been labeled “cooperative federalism” whereby state governments have more responsibility (Flesher, 2018). Beyond the dissolution of the Governance Coordinating Committee, policy documents contained no specific initiatives that detail how the Trump-era policy would implement the state empowerment priority.

Stakeholder involvement

The Obama administration prioritized stakeholder involvement more, with 24% of its statements focused on this issue versus 9% from the Trump administration. The Obama administration included stakeholders by conducting 24 listening sessions across the country in conjunction with the open comment period. A member of Congress highlighted this effort by stating in a hearing that “National Ocean Policy is merely a commonsense way to facilitate multi-stakeholder collaboration on complex ocean issues” (Lowenthal, 2017). Conversely, there was no mention of meaningful stakeholder involvement in the Trump-era policy. A White House press release only mentioned “engaging with stakeholders’’ with no specific outline of what the process would be like in practice. A national environmental magazine noted that the Trump-era policy “eliminate[d] the requirement for involving indigenous groups in decision-making” (Wei-Haas, 2019).

Discussion

Framing theory literature tells us that policy proponents and critics will purposely highlight certain aspects of a problem. At the same time, they will ignore other aspects to highlight a frame that is consistent with their values or principles (Chong and Druckman, 2007; Borah, 2011). For example, the Trump-era policy focused on robust offshore oil and gas drilling while ignoring previous oil spills. Meanwhile, the Obama-era policy focused on offshore renewable energy applications even though pursuing them might force thousands of people out of work. Additionally, Sniderman and Theriault (2004) noted that in political contexts, audiences are often exposed to multiple competing frames for a single issue (e.g., Obama-era policy attempting to lessen bureaucracy while critics were claiming it had actually increased bureaucracy). Specifically, the literature demonstrates that members of Congress carefully frame their messaging to advance their own personal policy preferences (Bergquist, 2020).

In this case study, we compare policy priorities for comprehensive ocean management between Democrat and Republican administrations. This research proposes a novel theoretical framework for how a future National Ocean Policy could be implemented with bipartisan support, leading to enduring legislation. We find that message framing around comprehensive ocean management varies in five key ways: 1) strategic and efficient ocean policy, 2) ecosystem stewardship, 3) economic, 4) federal versus subnational control, and 5) stakeholder involvement.

Perhaps the most significant finding was that both administrations, their policies, and their supporters communicated regularly about the importance of a productive ocean economy. The Obama-era policy prioritized conserving coastal and ocean ecosystems for future generations. Conversely, the Trump-era policy prioritized increasing offshore oil and gas drilling to promote energy independence. While the two policies took different approaches to growing the coastal and ocean economy, both recognized its importance to the strength of the broader U.S. economy.

Increasing strategic and efficient ocean policy was another similarity between the two administrations. Both administrations recognized that current efforts at coastal and ocean management were often being carried out in a siloed way, which led to duplicative and overly bureaucratic management. For example, a prominent environmental NGO noted that 20 federal agencies, with often conflicting goals, carry out more than 140 laws that manage American coasts and oceans (Ocean Conservancy, 2009). The Obama administration focused on reducing duplicative work by creating lines of communication between federal agencies, allowing them to share resources and expertise. The Trump administration focused on shifting authority back to the states. Even though the two administrations implemented this policy priority in different ways, both understood the importance of increasing strategic and efficient ocean policy as a way of better managing U.S. coasts and oceans.

The final significant similarity between the two administrations concerned state and regional empowerment. While these concepts were categorized differently in the dataset, they ended up being used in similar ways. Maack et al. (2014) noted that economic and personal ties to a region (e.g., the Gulf of Mexico) can create a culture in which people believe that it greatly impacts their local economy and everyday lives. Devolving authority from the federal government to subnational governments may be a way for states and regions to take more ownership of policy that impacts coastal livelihoods and local economies. The Obama-era policy focused on shifting decision-making and planning authority to the Regional Planning Bodies. Alternatively, Trump’s state empowerment policy priority was framed as a way of decreasing the overall size and authority of the federal government. Both administrations recognized the importance of subnational control of the coastal and ocean environments.

Governance via executive order

It is important to highlight that lawmaking in the U.S. has become increasingly difficult due to increased polarization in American politics (Lee, 2016; Heltzel and Laurin, 2020). Due to this, presidents often rely on executive orders to shift policy priorities (Howell, 2003). National Ocean Policy between the Obama and Trump administration were enacted via executive orders. Executive orders can be implemented and rescinded without input from Congress. The Trump and Obama administrations had different visions for a comprehensive ocean policy, which led to the Trump administration rescinding the Obama-era policy. The switch from the Obama-era policy to the Trump-era policy meant that eight years of planning and implementing ocean management objectives stopped and, in many cases, shifted in new directions. As goals shifted with the Trump-era policy, issues with efficient governance were exacerbated as agencies had to start implementing new policies. Deere (2021) noted that executive orders make sense during a natural disaster due to the speed at which they can be implemented. Additionally, Deere (2021) states that legislatures should implement laws and policies following normal legislative processes for issues that do not require immediate action. Fluharty (2012) notes that if Congress fails to make National Ocean Policy law through the legislative process, other efforts (e.g., executive orders) will likely never get the support or funding necessary to be effective long term. Lack of congressional support and funding was a noted issue in the Obama-era policy, which led to a number of priorities not being implemented.

Bipartisanship for future policy-making

Deere (2021) suggests that Congress should be the branch of government that implements comprehensive ocean management policy at the federal level. It is important to note that legislation through the current Congress would likely require some degree of bipartisanship. As of the 2022 elections, there are thin margins in the U.S. House of Representatives and Senate for at least the next two years. Lee (2016) suggests that when control is within reach for either party in the next election, bipartisan legislation is less likely because the minority party will not gain an advantage by working with the majority party. Conversely, bipartisanship is something that most Americans want from their representatives (Harbridge et al., 2014). If significant coastal and ocean management legislation is to be passed through traditional legislative processes, it will require Republicans and Democrats to work across the aisle and compromise. To achieve this, Van Boven et al. (2018) suggests that politicians need to look past their opposition to policy based on party membership and look at the policy itself. Additionally, Van Boven et al. (2018) notes the importance of environmental policy being enacted through traditional legislative methods due to the volatility of presidential directives between administrations (e.g., Trump rescinding the Obama-era policy in favor of his own, followed by Biden rescinding Trump policies in favor of his own). The Land and Water Conservation Fund of 2020 and the Clean Water Act of 1972 highlight that precedent exists for bipartisan agreement on environmental legislation.

This research focuses its findings and recommendations on how future policy-makers might be able to reach bipartisan consensus. We believe that Congress should focus on the three main areas of similarity between the Obama and Trump-era policies: 1) the reduction of duplicative work within federal agencies that work on ocean and coastal issues, 2) empowering states and regional bodies to plan and implement policies they deem to be most important for their areas, and 3) an understanding that a strong ocean and coastal economy that prioritizes conservation is imperative to the strength of the broader U.S. economy. If bipartisanship is necessary for the future of a comprehensive coastal and ocean policy, then these three areas may allow members of Congress to reach across the aisle and pass lasting legislation.

Conclusion

This research suggests that Framing Theory is a useful framework for identifying policy priorities between presidential administrations. As demonstrated in our analysis, Framing Theory provides a structure for uncovering nuanced policy positions for complex natural resource management issues. It also allows for complex issues and policies to be broken down into the primary issues needing to be addressed and how policy addresses those issues (Tewksbury and Scheufele, 2019). The inductive coding approach allows for discovery of policy priorities that can then be analyzed between administrations.

Exploration of policy preferences between different administrations may help to generate approaches for bipartisan cooperation in future attempts at comprehensive federal ocean policy. This research shows that the Obama and Trump administrations used three policy priorities in similar ways. Both administrations regularly communicated the importance of a robust ocean and coastal economy to the broader American economy. The two administrations also placed an emphasis on increasing strategic and efficient management of marine resources to lessen bureaucracy and create open lines of communication between levels of government. Lastly, both administrations took steps to shift decision-making authority from the federal government to state and regional management structures. They recognized that the complexity and diversity of issues in American waters are best addressed at the subnational scale.

This research contributes to Framing Theory by expanding its insights into how government actors frame messages to the public and to other high-level stakeholders to garner support for complex issues. Future research into natural resource management issues in the U.S. can further our understanding of potential areas of agreement between partisan government actors. As political polarization makes it difficult to pass meaningful legislation at the federal level, finding areas of bipartisan agreement will be an essential tool for conserving natural resources in the face of climate change and growing coastal populations.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author contributions

GJ: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. KD: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Methodology, Project administration, Supervision, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. RW: Formal analysis, Methodology, Validation, Writing – review & editing. CA: Funding acquisition, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Gulf Research Program, Health Ecosystems IV, Grant. Number: 200011513.

Acknowledgments

Amanda Alva, Sabine Bailey, Thomas Moorman, Kasen Wally.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ The National Ocean Policy was partly based on the U.S. Ocean Action Plan Implementation Update, a George W. Bush administration report based on recommendations provided by Congress, specifically its U.S. Commission on Ocean Policy (National Ocean Policy; Committee: House Natural Resources, 2011)

- ^ The study period officially ended in January 2021 after the creation of an Ocean Policy Committee at the White House following the 2021 National Defense Authorization Act, a now permanent committee at the federal level that coordinates policy across agencies and serves as a way to engage with ocean stakeholders broadly.

- ^ In total, nine regions were identified in the executive order: Alaska/Arctic, Caribbean, Great Lakes, Gulf of Mexico, Mid-Atlantic, Northeast, Pacific Islands, South Atlantic, and West Coast regions.

- ^ The states included Connecticut, Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, and Vermont. Along with these states, there were six federally recognized tribes, nine federal agencies, and the New England Fishery Management Council included in the planning and writing of the plan.

- ^ The states included Delaware, Maryland, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Virginia. Along with these states, there were eight federal agencies, two federally recognized tribes, and the Mid-Atlantic Fishery Management Council included in the planning and writing of the plan.

- ^ Also eliminated were: The National Ocean Council Deputies Committee, National Ocean Council Senior Policy Contact Committee, Governance Coordinating Committee, Ocean Resource Management Interagency Policy Committee and sub-committees, and the Ocean Science and Technology Interagency Policy Committee

- ^ The step-by-step implementation procedures were contained within the National Ocean Policy Technical Appendix.

References

American Bar Association (2021) What Is an Executive Order? Available online at: https://www.americanbar.org/groups/public_education/publications/teaching-legal-docs/what-is-an-executive-order-/.

Ardèvol-Abreu A. (2015). Framing theory in communication research. Origins, development and current situation in Spain. (Revista Latina de Comunicación Social). doi: 10.4185/rlcs-2015-1053en

Bergquist P. (2020). Congress as theatre: how advocates use ambiguity for political advantage. J. Public Policy 40, 51–71. doi: 10.1017/s0143814x18000284

Borah P. (2011). Conceptual issues in framing theory: A systematic examination of a decade’s literature. J. Communication 61, 246–263. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2011.01539.x

Carragee K. M., Roefs W. (2004). The neglect of power in recent framing research. J. Communication 54, 214–233. doi: 10.1111/j.1460-2466.2004.tb02625.x

Cheung K. K. C., Tai K. W. H. (2021). The use of intercoder reliability in qualitative interview data analysis in science education. Res. Sci. Technological Educ. 41 (3), 1–21. doi: 10.1080/02635143.2021.1993179

Chong D., Druckman J. N. (2007). Framing theory. Annu. Rev. Political Sci. 10, 103–126. doi: 10.1146/annurev.polisci.10.072805.103054

Deere K. J. (2021). Governing by executive order during the COVID-19 pandemic: preliminary observations concerning the proper balance between executive orders and more formal rule making. Soc. Sci. Res. Network. doi: 10.2139/ssrn.3794825

Economics and Demographics (n.d). Available online at: https://coast.noaa.gov/states/fast-facts/economics-and-demographics.html.

Flesher J. (2018). Trump scraps Obama policy on protecting oceans, Great Lakes (United States: AP NEWS). Available at: https://apnews.com/article/57d405229ba844f59f9f2d06c65c4318.

Fluharty D. (2012). Recent developments at the federal level in ocean policymaking in the United States. Coast. Manage. 40, 209–221. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2012.652509

Goelz T. (2022). Accounting for climate change in United States regional ocean planning: comparing obama and trump national ocean policies to a climate-forward approach. Sustain. Dev. Law Policy 21, 5.

Guidance for Implementing Executive Order 13840, Titled “Ocean Policy to Advance the Economic, Security, and Environmental Interests of the United States (2018). Trump White House Archives (United States: Executive Office of the President). Available at: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/20180628EO13840OceanPolicyGuidance.pdf.

Harbridge L., Malhotra N. R., Harrison B. (2014). Public preferences for bipartisanship in the policymaking process. Legislative Stud. Q. 39, 327–355. doi: 10.1111/lsq.12048

Heltzel G., Laurin K. (2020). Polarization in America: two possible futures. Curr. Opin. Behav. Sci. 34, 179–184. doi: 10.1016/j.cobeha.2020.03.008

Howell W. (2003). Power Without Persuasion: The Politics of Direct Presidential Action (United States: Princeton University Press).

Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force (2009) The White House. Available online at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/administration/eop/ceq/whats_new/Interagency-Ocean-Policy-Task-Force.

Jacoby W. G. (2000). Issue framing and public opinion on government spending. Am. J. Political Sci. 44, 750. doi: 10.2307/2669279

Lanard J. (2016). Industry, GOP Charge National Ocean Policy Imposes New Federal Oversight (United States: House Natural Resources Committee Hearing).

Lee F. E. (2016). Insecure Majorities: Congress and the Perpetual Campaign (United States: University of Chicago Press).

Lowenthal A. (2017). Department of the Interior, Environment, and Related Agencies Appropriations Act. (United States of America: Congressional Testimony).

Lubchenco J. (2011). The President’s New National Ocean Policy: a plan for further restrictions on ocean, coastal, and inland activities (House Natural Resources Committee Hearing).

Maack E., Mills S., Borick C. P., Gore C. J., Rabe B. G. (2014). “Environmental Policy in the Great Lakes Region: Current Issues and Public Opinion,” in Social Science Research Network. (Energy and Environmental Policy, No. 10). Available at: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/Delivery.cfm/SSRN_ID2652857_code1109496.pdf?abstractid=2652857&mirid=1&type=2.

McHugh M. L. (2012). Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochemia Med. 22, 276–282. doi: 10.11613/BM.2012.031

National Ocean Policy Implementation Plan (2013). Obama White House Archives. (United States: National Ocean Council). Available at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/sites/default/files/national_ocean_policy_implementation_plan.pdf.

NOAA Office for Coastal Management (n.d) The National Coastal Zone Management Program. Available online at: https://coast.noaa.gov/czm/.

Ocean Conservancy. (2009). The Future of Ocean Governance: Building our National Ocean Policy (Subcommittee on Oceans, Atmosphere, Fisheries, and Coast Guard Hearing).

Podesta J. (2012) John Podesta on U.S. Ocean Policy Report Card, Importance of Full Implementation of National Ocean Policy. Available online at: https://www.americanprogress.org/press/statement-john-podesta-on-u-s-ocean-policy-report-card-importance-of-full-implementation-of-national-ocean-policy/.

Rudalevige A. (2021). By Executive Order: Bureaucratic Management and the Limits of Presidential Power (United States: Princeton University Press).

Shah D. V., Watts M., Domke D., Fan D. P. (2002). News framing and cueing of issue regimes. Public Opin. Q. 66, 339–370. doi: 10.1086/341396

Shulman H. C., Sweitzer M. D. (2018). Advancing framing theory: designing an equivalency frame to improve political information processing. Hum. Communication Res. 44, 155–175. doi: 10.1093/hcr/hqx006

Sniderman P. M., Theriault S. M. (2004). “The Structure of Political Argument and the Logic of Issue Framing,” in Studies in Public Opinion (United States: Princeton University Press), 133–165.

Tewksbury D., Scheufele D. A. (2019). “News Framing Theory and Research,” in Routledge eBooks. (Routledge, United States), 51–68. doi: 10.4324/9780429491146-4

The Nation’s First Ocean Plans (2016) The White House. Available online at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/blog/2016/12/07/nations-first-ocean-plans.

The White House Council on Environmental Quality (2010). Final Recommendations of the Interagency Ocean Policy Task Force. (United States: Executive Office of the President of the United States). Available at: https://obamawhitehouse.archives.gov/files/documents/OPTF_FinalRecs.pdf.

Trump D. (2019). “Memorandum on Ocean Mapping of the United States Exclusive Economic Zone and the Shoreline and Nearshore of Alaska,” in Trump White House. Available at: https://trumpwhitehouse.archives.gov/presidential-actions/memorandum-ocean-mapping-united-states-exclusive-economic-zone-shoreline-nearshore-alaska/.

U.S. Department of Interior (2004) President Bush Continues His Strong Commitment To Our Oceans And Proposes Substantial New Funding For Oceans Priorities. Available online at: https://www.doi.gov/sites/default/files/archive/news/archive/07_News_Releases/070126_FACTSHEET.html.

Van Boven L., Ehret P. J., Sherman D. H. (2018). Psychological barriers to bipartisan public support for climate policy. Perspect. psychol. Sci. 13, 492–507. doi: 10.1177/1745691617748966

Vreese C. H., Lecheler S. (2016). Framing theory. Int. Encyclopedia Political Communication, 1–10. doi: 10.1002/9781118541555.wbiepc121

Yin R. K. (2017). Case Study Research and Applications: Design and Methods (6th ed.) (United States: SAGE Publications).

Appendix 1: Intercoder Reliability Testing

All four of the additional coders had experience qualitatively coding data and worked independently to avoid discussing coding disagreements until the end of the coding process (Cheung and Tai, 2021). We used the percentage of agreement for its simplicity and found that my coding and the other researchers’ coding were in agreement 93.7% of the time. To further strengthen the intercoder reliability testing, we used a Cohen’s kappa test. This statistical testing method was specifically designed to test for intercoder reliability. Cohen recognized that percent agreement does not account for the chance that coders could simply take a random guess if they were not sure about certain codes, which could lead to false agreement (McHugh, 2012). The output of Cohen’s kappa test ranges from -1 to 1 where 1 represents perfect agreement and values below 0 potentially indicate a serious problem in the collection of data or the need to retrain coders. Positive numbers in a Cohen’s kappa test indicate the level of agreement between coders. For the purpose of this research, we compared the primary researcher’s coding with that of the four assistant coders. The four Cohen’s kappa outputs were.81,.82,.87, and.89. These results indicate a strong level of agreement rating, bordering on an “almost perfect” level of agreement (McHugh, 2012). This suggests that the results of the two intercoder reliability tests indicate that coding between all researchers was consistent.

Appendix 2: Detailed breakdown of qualitative tables

Keywords: National Ocean Policy, executive orders, public policy, Obama, Trump

Citation: Johnson G, Anderson C, Dunning K and Williamson R (2024) National ocean policy in the United States: using framing theory to highlight policy priorities between presidential administrations. Front. Mar. Sci. 11:1370004. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2024.1370004

Received: 13 January 2024; Accepted: 28 March 2024;

Published: 24 April 2024.

Edited by:

Daniel Suman, University of Miami, United StatesReviewed by:

Lida Teneva, Independent Researcher, Sacramento, CA, United StatesDi Jin, Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, United States

Copyright © 2024 Johnson, Anderson, Dunning and Williamson. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Gregory Johnson, Z2FqMDAxMkBhdWJ1cm4uZWR1

†Present addresses: Gregory Johnson, Executive Office of the President, Washington, DC, United States

Kelly Dunning, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, United States

Ryan Williamson, University of Wyoming, Laramie, WY, United States

Gregory Johnson

Gregory Johnson Christopher Anderson

Christopher Anderson Kelly Dunning†

Kelly Dunning†