- 1Department of Women’s Studies, San Diego State University, San Diego, CA, United States

- 2Department of Geography, Memorial University of Newfoundland, St. John’s, NL, Canada

- 3Oceana Canada, Halifax, NS, Canada

- 4School of Environmental Studies, University of Victoria, Victoria, BC, Canada

Introduction: Ocean equity is a key aim of blue economy frameworks globally and is a pillar of the international High Level Panel for A Sustainable Ocean Economy. However, the Panel offers only a general definition of ocean equity, with limited guidance for countries. Canada, as a party to the High Level Panel’s blue economy agenda, is developing its own blue economy strategy, seeking to reshape its ocean-based industries and advocate for new ones. How equity will be incorporated across scales is not yet known but has implications for how countries like Canada will develop their ocean-based industries. This raises important questions, including what are Canada’s equity commitments in relation to its blue economy and how will they be met? Currently, the industries identified in Canada’s emerging blue economy narratives are governed through both federal and provincial legislation and policies. These will shape how equity is implemented at different scales.

Methods: In this paper, we examine how the term equity is defined in relevant federal and provincial legislation and look to how understandings of equity found in critical feminist, environmental justice, and climate justice scholarship could inform policy and its implementation within Canada’s blue economy. We focus on two industries that are important for Canada’s blue economy: offshore oil and marine salmon aquaculture in the Canadian province of Newfoundland and Labrador. We investigate how existing legislation and policy shapes the characterization, incorporation, and implementation of equity in these industries.

Results and discussion: Our analysis highlights how a cohesive approach to ocean equity across the scales of legislation and policy is needed to ensure more robust engagement with social and environmental equity issues in blue economy discourse and implementation.

Positionality statement

We are a group of settler academics from Canada and the United States with varied academic and personal backgrounds that have shaped our theoretical and methodological perspectives and approaches to ocean governance. These include human geography, policy and governance, critical political economy, and feminist scholarship. We are committed to understanding equity in ways that are informed by these theoretical and methodological approaches but also acknowledge that these are limited by our own world views and experiences. Therefore, we engage with climate justice, environmental justice, and critical feminist scholarship to inform our thinking and recommendations for Canada’s emerging blue economy. While we don’t take up an Indigenous framework, we do support efforts for decolonization and anti-colonization through recommendations of reparations via land/ocean back. This paper represents our efforts to think through equity in Canada’s emerging blue economy and collaboratively frame and analyze problems, identify important questions, and speak to both governments and scholars contemplating these issues. At the same time, we acknowledge that how we approach equity in this paper, including the guidelines we arrive at, fall within particular approaches to land/ocean governance and that other approaches to equity exist that we do not engage with. Our hope is that offering our perspective on ocean governance and offering some suggestions will be part of wider conversations that allow for a larger discussion on equity in oceans.

1 Introduction

“If we use the wrong frame to understand the problem, we come up with the wrong solution” (CRT Summer School, Janel George, July 20, 2022).

Coastal nation-states and international governance organizations have increasingly been promoting and adopting blue economy approaches to ocean governance, often as a way to address climate change while simultaneously growing ocean economies. These emerging blue economy approaches often rebrand existing ocean economies into new “blue” ones using amorphous and flexible language that paints blue economy frameworks as depoliticized ways to achieve holistic governance (Schutter et al., 2021). What this means is that blue economies vary in their overarching goals and how they are implemented. Some, for instance, emphasize conservation, ocean protection, or innovation and new technology (Voyer et al., 2018). Others focus on the economic, social, and political promotion of marginalized groups, thus bringing them in line with the emphasis on “no one left behind” (Ota et al., 2022) found in the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (for example see, Voyer et al., 2018; Fusco et al., 2022).

The High-Level Panel for A Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel) emerged as a way for coastal nations to come together on sustainable ocean governance and blue economies. It now represents seventeen coastal nations, including Canada, all with a shared vision of achieving ocean sustainability while also generating new economic development opportunities. Drawing on the United Nations SDGs, the Ocean Panel lays out “a new ocean agenda” to achieve transformative sustainable change in future ocean development, specifically through the creation of five ocean pillars: wealth, health, equity, knowledge, and finance (Frost and Teleki, 2020). While each pillar is explained individually, the agenda asserts that they necessarily intersect with each other. The Ocean Panel argues that “mutually reinforcing transformations” (FAO, 2022, 5) among all pillars are needed to achieve its goals. In other words, none of the pillars of a blue economy should be taken up in isolation if transformative change is to be achieved. Given that the Ocean Panel’s approach has been signed onto by member countries, we might expect each nation’s blue economy plans to look toward it for guidance on incorporating equity into ocean governance. Unfortunately, the Ocean Panel’s definition of equity is vague and offers limited direction on how to enact it. This leaves space for flexibility in how equity is interpreted and acted on at national and sub-national levels of policy and implementation, and thus, how regional blue economies and the economic activities included in them align with the High-Level Panel’s blue economy ideals.

In this paper, we investigate some of these regional blue economy activities in Canada to explore the existing Canadian governance context and its potential to foster the equitable blue economies envisioned by the Ocean Panel. Our approach centers not just if but also how different geographic scales of blue economy policies, activities, and discourses align. Canada may create a blue economy strategy at the federal level informed by the High-Level Panel, but the ocean economies and industries referenced in the strategy are governed by multiple scales of legislation, policies, and guidance, and thus regional governance spaces are also influential policy spaces. Therefore, we are interested in whether equity requirements at the federal level will (or even can, given the existing context) “trickle down” to project approval or implementation stages or if policy inconsistencies are leading to what we call policy “dead zones” within ocean governance. In other words, we examine what existing capacity, or equity scaffolding, there is within regional blue economies to enact Canada’s blue economy goals and ask what will need to change for these goals to be enacted in the future.

To do this, we identify equity commitments for the ocean at national and provincial levels and then analyze equity requirements and implementation for project approval processes for two Canadian blue economy industries, offshore oil and marine salmon aquaculture. Our geographical focus is the province of Newfoundland and Labrador (NL) because of a) the significant impact that federal blue economy policies will have in the province given its high dependence on ocean industries, and b) the importance of oil and aquaculture to the provincial economy and Canada’s broad blue economy vision. Both industries have been established in the province for over a decade, are economically significant, rely on technological advancement to solve their sustainability issues, and are partially federally regulated. Thus, they are good examples to explore the different scales of equity within Canada’s blue economy industries and how the understanding and practice of equity moves through and across these scales (or not). We use these examples as a way to link regional blue economies and the activities taking place within them to the broader blue economy planning of which they are part. Our approach and analysis in this paper draws on environmental justice, climate justice, and critical feminist theories because of how they engage with the complexity of social and environmental equity in ways that are often missing from current marine legislation and policy. This lack of complexity in addressing inequities risks recreating a business as usual approach to ocean governance. Establishing transformative blue economies will require understanding the complexity of equity within and across governance jurisdictions and scales. This is the issue we take up in this paper.

Our next section provides a description of our methods followed by a review of how equity has been taken up within ocean governance literatures. Following this, we explore what equity looks like in Canadian ocean policy by analyzing existing publicly available legislation, policies, and strategic frameworks at both a national level and within regional project approval processes, specifically the development of the Hebron oil field and the Grieg Aquaculture projects in NL. We investigate how equity is defined (or not) and how this informs implementation. This leads us to identify 1) what we call policy “dead zones” for equity, which are gaps in the incorporation and conceptualization of equity that may create challenges for regional blue economies and projects to align with Canada’s blue economy goals, and 2) equity zombies, which are instances where equity considerations are not completely absent but are undeveloped or without substance. Finally, we examine some possible avenues for how Canada’s ocean governance could include equity in clearer, more integrative, and more actionable ways at all levels of policy and implementation.

2 Methods

We began by trying to make sense of the interconnected policy web in which our case is situated and how equity is presented and enacted within it. This web includes the multiple scales and layers of governance, including law, policy, strategic documents, and consultations that apply to oceans. We created a list of relevant documents that are influencing the development of Canada’s blue economy. These included specific ocean policies and legislation that were relevant for the development of the aquaculture and oil industries, including the following: Transformations for a Sustainable Ocean Economy (Ocean Panel); Towards Ocean Equity (Ocean Panel); What We Heard Report (Canada, Department of Fisheries and Oceans); The Impact Assessment Act of Canada; The Canadian Fisheries Act; The Atlantic Accord Implementation Acts (“The Accord Acts1”); Canada’s Gender Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) policy framework; the Canadian Environmental Protection Act; the NL Environmental Protection Act; and the NL Aquaculture Act. We looked to these particular pieces of legislation, policies, and strategic documents because they were directly relevant to the governance of oil and aquaculture industries; however, we also recognize that there are many other laws, policies, treaties with Indigenous peoples, and international agreements that influence the development of oil and aquaculture. We focused on overarching policy documents that hierarchically regulate and guide the planning and development of these industries by Canadian federal and provincial governments who are building the blue economy policy. However, we also recognize that there are many other laws, policies, treaties with Indigenous peoples, and international agreements that influence the development of oil and aquaculture.

We wanted to understand how equity was understood and incorporated into these documents, thus we analyzed them using key search terms and questions related to social, environmental, and economic equity. Our approach was to search for the term equity and qualitatively code its use based on the following questions: 1) Is there an ‘equity’ vision? 2) Does this vision include sustainability? 3) Does the framing of sustainability include economic, social, and environmental considerations? 4) Are there specific requirements to actualize equity? and 5) Are there processes for accountability? However, we stopped after realizing that these documents were, for the most part, not engaging with equity even if the term was present in the document.

Our second attempt was more targeted. Rather than assuming that equity is included, we first asked whether it was mentioned at all. If it was, then we examined how it was incorporated in each document and the implications of this on ocean policy and development. Thus, our methods moved from trying to both qualitatively code and quantitatively count equity to more of an exploration of where and how equity shows up across policy scales and down to actual project approval. We don’t suggest here that we have explored all actual or potential uses of equity in the policies associated with ocean governance. Rather, our exploration focused on trends in how the Canadian government, provincial government, and industry are currently understanding and using the term. In other words, our approach is to take a snapshot of policy at different scales (federal and provincial) that is applicable to specific project approval processes for oil and aquaculture in NL’s blue economy.

Next, we turned our efforts toward exploring the specific project approval processes for Grieg Aquaculture and the Hebron oil field development project at the provincial level. Each project, as a result of its specific timeline, offered a different perspective on how equity is (and potentially could be) implemented in projects within Canada’s blue economies. The aquaculture industry, particularly Grieg Aquaculture in NL, provides a recent example of how current equity and diversity policies have been incorporated into environmental impact assessments (EIAs). However, the aquaculture project was delayed due to Covid-19 and was not yet fully operationalized when we conducted our analysis. This has resulted in a limited amount of data that were publicly accessible. What was accessible was restricted to mainly provincial press releases, newspaper stories, and company reports. In contrast, the Hebron oil field developed by Exxon Mobile (and other joint venture partners) began production in 2017 and provides ten years of data on how gender equity and diversity has been implemented in employment practices (see Supplementary document A). The Hebron project therefore provides a longer term analysis of how equity is understood and incorporated in the offshore oil industry. It also offers insight into how Grieg and other aquaculture projects may address equity in their projects going forward.

3 Equity in ocean governance: what makes ocean governance equitable?

Our paper builds on a growing body of scholarship that highlights the tension between maintaining the status quo and transforming it to achieve equitable and just change, specifically in ocean spaces. For example, some environmental justice, climate justice, and critical feminist scholars have pointed out how blue economic growth narratives have maintained and reproduced business as usual but that this is obfuscated by narratives that align with the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (for example see, Voyer et al., 2018; Fusco et al., 2022). As Collard et al. argue, there is a need “to advance social science, humanities, and ‘critical’ perspectives that acknowledge the social and power relations that shape environmental outcomes and relations - and as such understand that these linkages must be central to any treatment of ‘environment’ or ‘nature’, including associated political and policy responses” (2018, 6).

Environmental and climate justice approaches highlight how equity issues related to climate change are entwined with equity issues more broadly in society. They draw attention to the way racialized people of color, Indigenous peoples, low-income people, and disabled people (among others), face greater exposure to environmental racism and thus harm from industrial developments, toxic waste, pesticides, and climate change (Pellow, 2000; Pulido, 2000; Pellow and Park, 2002; Harrison, 2011; Bond, 2014; Piepzna-Samarasinha, 2020; Johnson et al., 2022). In addition, they highlight how social inequities are structural, resulting from patriarchal and white supremacist practices that maintain and institutionalize white privilege within governments (and other institutions). This may manifest overtly, for instance, as weak or badly enforced legislation and policies. Indeed, Pulido’s important work (2015) illustrates that white supremacy is often only associated with radical extremists while its more subtle manifestations and maintenance are overlooked. This includes how white supremacy is supported and facilitated through government and regulatory leniency that has led to constant contamination and ill-health of low income, racialized, and migrant communities (Pulido, 2015). Failure to enforce environmental regulations and policies in racialized communities can lead to ill-health and death of racialized people. In ocean contexts, examining the structural causes of social inequity would mean, for instance, incorporating racial analysis into how the United States is planning for sea-level rise (Hardy et al., 2017) or how legislation and regulation allows for the toxic waste dumping in the Gulf of Guinea (Okafor-Yarwood and Adewumi, 2020). Addressing structural inequities in ocean contexts would also mean starting from an understanding of how colonial relations have impacted small island nations, including the erasure of their lands, livelihoods, homes, and communities as a result of rising waters (Falzon and Batur, 2018). Additionally, including the voices and experiences of disabled people and how existing policies and structures often overlook their experiences is a critical aspect of equitable ocean policy. Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha states that “as we’re pushed out of coastal cities due to hypergentification and as the sea levels rise, what new disabled homes and communities will be built in the exurbs and wastelands?…What if all those promised green infrastructures and jobs centered disability justice from the beginning?” (2020, 260).

Feminist approaches often highlight how inequities impact those who have been marginalized in society due to compounding or intersectional social categories, such as race, class, disability, gender, and sexuality (Sultana, 2022). Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989), who coined the term intersectionality, specifically centered the experiences of black women in the US legal system and how these experiences are shaped by compounding aspects of gender and racialization processes. Intersectional analysis thus requires a consideration of how multiple intersecting identities shape the lived experience of individuals and how particular social and governance systems and structures can address or exacerbate social inequities. Intersectionality is therefore a crucial part of building equitable environmental governance frameworks; however, it will only be successful if it is incorporated in ways that reflect its original meaning and intent. Thus, a critical point we are making in this paper is that how intersectionality is done matters.

Therefore, we argue that place-based nuanced understandings of intersectional power relations within groups deemed vulnerable or resilient in the face of climate change in coastal regions in Canada is as critical as looking at intersectional power relations between groups for ensuring effective ocean/blue policies that do not maintain or exacerbate inequities. For instance, vulnerability has been critiqued for being vague and often used in inconsistent ways, which can be problematic if incorporated into law, policy, or programs. Its use may also mask the deeper structural causes of inequity (Katz et al., 2020) and contribute to the perspective that western knowledge systems are the only, or the most valid, knowledge system. As Collard et al. point out, “the politics of knowledge shapes what counts as ‘sustainable’, or ‘resilient’, or not” and thus critical scholarship must ask “for whom, for what, at what scale” these terms are applied (Collard et al., 2018, 8). For example, Johnson et al. (2022) argue for the use of a deeply intersectional lens in their study of climate change and vulnerability for coastal Maori communities in New Zealand. They argue that a limited focus on a population’s vulnerabilities to climate change may miss the variety of solutions and coping strategies within a population. In other words, by focusing on the negative aspects of what we term vulnerable populations, we can miss the strengths of different groups of people within that population. Deep intersectional analysis is therefore important because it reveals how commonly used terms in western science/knowledge systems, such as sustainability, resilience, adaptation, and vulnerability, may not adequately reflect real populations or what their social, economic, or cultural needs or strengths are.

Blue economies are both an emerging governance approach and area of scholarly study. We argue that scholarly approaches that draw on critical environmental justice, climate justice, and feminist approaches are needed to understand how ocean adjacent nations like Canada are redefining ocean spaces using blue economy frameworks. Here we draw attention to Bennett et al. (2021) because of how they build on understandings of equity conceptualized by environmental justice scholarship and apply it in the context of ocean governance. They draw on four overlapping types of equity often found in environmental justice literature: recognitional, procedural, distributional, and contextual/structural. Broadly speaking, recognitional justice acknowledges and respects pre-existing or pre-colonial governance arrangements as well as distinct rights of different groups in decision making (i.e., mutual respect); procedural justice refers to the quality of the governance process measured by the level of participation and inclusivity in decision-making (i.e., inclusiveness); distributional justice refers to how benefits and harms are distributed; and contextual/structural justice refers to the broader social context that frames and supports the three other types of justice. Bennett et al. (2021) build on these four types of justice by adding two additional areas, management and environment, which they argue are needed for just and equitable ocean governance. Through the addition of management, they highlight the key difference between specific policies and how those policies are implemented. Their addition of the environment brings attention to and centers the links between environmental concerns and social concerns in ways that align with social justice literature. This includes, for instance, how issues of health, food security, and livelihoods are key aspects of environmental equity (Bennett et al., 2021).

For Canada’s elected federal government, which is committed to feminism and reconciliation, understanding how environmental and social equity and justice are connected to patriarchal white supremacy and ableism should be fundamental. This is especially the case given its history and active experiences of injustices in ocean governance, including settler colonialism and its associated consequences for Indigenous peoples, cultures, livelihoods, and rights (Barsh, 2002; Kourantidou et al., 2021). Thus, in this paper, we use critical environmental justice, climate justice, and feminist approaches, including the core concepts and concerns related to environmental racism and intersectionality, to explore how the government engages with equity within legislation and policy across governance scales and to suggest ways this could be done to ensure commitments to feminism and reconciliation are met.

4 Equity at multiple scales: looking for equity

In this section, we examine findings from our analysis of the policy and implementation of equity in Canada’s ocean governance at multiple scales. In part 4.1, we examine equity in Canada’s broad policy context through its GBA+ framework, which uniquely cuts across multiple federal departments and is tied to equity in the blue economy strategy planning. This sets the broad context for ocean policy. We then look at how equity is being incorporated into Canada’s work toward a blue economy strategy via analysis of several federal pieces of legislation that will play a critical role in how blue economies are enacted at regional scales. Following this in section 4.2, we focus on two regional project approval processes in Newfoundland and Labrador to examine the interaction between federal and provincial policies and how equity is understood and enacted within and across government jurisdictions. Through this analysis of ocean equity policy and practice at multiple scales, we discuss where we found reference to equity, how equity is understood, what requirements (if any) are present for considering equity, and where actual or conceptual equity dead zones exist.

4.1 Equity across government: GBA+ as a cross-cutting government policy on equity in Canada

Equity has been invoked sporadically in Canadian policy discourses in the past. For instance, the term has been used in the context of reconciliation for past injustices and violence by the colonial state against the Indigenous peoples of Canada. This use has primarily been through commitments to policy change, such as through the internationally recognized Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC, 2015). However, most equity efforts have not applied across all government departments. One exception is Canada’s Gender Based Analysis Plus framework (GBA+), first introduced as GBA in the mid-1990s. GBA+ is described as a feminist-informed framework and has been mandated for use across all government departments as a way to address inequity (Pictou, 2020). It was originally focused solely on gender under the acronym GBA; however, this changed in 2012 with the addition of the “+” to allow for the consideration of multiple dimensions of people’s identity (including race, ability, age, sexual orientation, etc.), which the government described as an intersectional approach. According to the government, GBA+ assesses “how diverse groups of women, men and non-binary people may experience policies, programs, and initiatives. The ‘plus’ in GBA+ acknowledges that GBA goes beyond biological (sex) and socio-cultural (gender) differences” (Canada, 2022a; Canada, 2022b). We therefore focus our attention on this framework because of its unique application across government and its use in Canada’s blue economy planning [e.g. the incorporation of intersectionality and GBA+ in the Canadian government’s blue economy engagement paper (Canada, 2021)]. Moreover, as GBA+ is already built into the federal government’s policy infrastructure of the federal government, it should already be used in current and emerging blue economy spaces and industries that are federally regulated. Thus, we argue that GBA+ forms the broad government-wide context for equity in Canadian Government policy, including ocean policy.

The most common way that the GBA+ frame is used in the federal government is as a tool for corporate governance, for instance to work toward gender parity in staffing and increase racial, ethnic, and religious diversity within organizations. This use of GBA+ reflects how the corporate sector has adopted equity, diversity, and inclusivity programs (Seijts and Young, 2021). However, governments can also use GBA+ as an analytical tool to examine the outcomes of policy implementation on gender, racial, and gender-diverse groups historically excluded from consideration in policies (including the Indigenous peoples of Canada). This approach has been adopted specifically by the Impact Assessment Agency (IAAC) and the Department of Fisheries and Oceans (DFO), both of which are federal departments that play a key role in ocean industries, including oil and aquaculture, and thus the blue economy.

DFO, in addition to spearheading the development of Canada’s blue economy strategy, is one of the first federal departments to propose enshrining GBA+ in legislation that governs the department (DFO, 2017). In reference to GBA+, DFO states that “The Framework mandates a requirement to consider sex, gender, and diversity issues (through a GBA+ analysis) in the development of all initiatives, policy, or program proposals seeking new funds or Ministerial approval” (DFO, 2017). Departmental planning for fiscal years 2018-19 to 2021-22 shows that DFO’s plans for implementing GBA+ largely reflect the goals of corporate governance (i.e., increasing the participation of women in the workforce), rather than addressing social inequities within program implementation (DFO, 2022). Fisheries agreements represent a rare example of GBA+ in DFO’s program implementation. However, this has largely involved paternalistic approaches to ensuring gender diversity for Indigenous peoples and simultaneously ignores Canada’s past discrimination of Indigenous peoples through the Indian Act (Pictou, 2020). As Pictou (2020) argues, colonization of Indigenous peoples in Canada included the forced participation in western patriarchal social structures that enforced (and currently enforces) patriarchal hierarchies onto Indigenous peoples and their governance structures.

On the other hand, the Impact Assessment Agency of Canada adopted GBA+ as an analytical tool with the 2019 Impact Assessment Act (IAA), a completely new act that replaced the previous Canadian Environmental Assessment Act of 2012 (CEAA 2012). Unlike CEAA 2012, the new IAA now must include the consideration of “the intersection of sex and gender with other identity factors” when impact assessments are done. Since the enactment of the IAA, the agency has also released a guidance document on GBA+ in impact assessment, which is meant to “guide practitioners in identifying who is impacted by a project and assess how they may experience impacts differently” (IAIA, 2021). Despite this statement and guidance, impact assessments are typically the responsibility of project proponents (such as oil companies) and so how these companies (and the consultants who conduct the assessments) integrate GBA+ requirements is still in early stages. Therefore, at the broad federal level, how equity is being addressed via GBA+ is patchy, even when mandated across all departments. Consequently, the strength of GBA+ as a tool to guide and foster structural change is limited. We now turn to how equity, specifically through GBA+, shows up in ocean specific Canadian policies.

4.1.1 Equity in the ocean: policy dead zone #1

Interest in formalizing an equity-based approach to the ocean is reflected in Canada’s current work developing a blue economy strategy (Canada, 2021). Because this strategy has not been finalized, we used The Blue Economy Engagement Paper (BE engagement paper), a document released by DFO in 2021 and used to gather public feedback about the government’s forthcoming blue economy strategy. Equity shows up a total of five times in this document, with two irrelevant uses (specifically lending equity). The other three instances referenced equity generally, mentioning how a blue economy strategy could help “improve” and “promote” equity. In contrast, the Engaging on Canada’s Blue Economy Strategy - What we heard report (2022), contains feedback on Canada’s proposed blue economy strategy from the public. The document references equity 27 times (excluding table of contents). These were found in several key actions derived directly from the feedback from the public consultation process. References included equity (n=8), regional equity (n=6), gender equity (n=6), and intergenerational equity (n=4). Some specific recommendations from the public included, for example, to “[a]lign policies to achieve regional equity and greater consistency across sectors” (DFO, 2022, 16) and support “more accessible and affordable education and training options….[and] non-governmental initiatives helping under-represented groups become more involved in blue economy activities” (DFO, 2022, 20). This highlights how the general public is raising issues of equity in the context of emerging blue economies but also that more specific thinking around equity is desired.

GBA+ is specifically referenced in Canada’s BE engagement paper as an important aspect of the government’s new blue economy vision. The paper states that “[a]n intersectional Gender-Based Analysis Plus (GBA+) lens will be applied to the development of initiatives that fall under the blue economy strategy in order to anticipate potential impacts on diverse groups of Canadians. By identifying issues early, the blue economy strategy will be positioned to help mitigate inequalities and promote equity in the ocean sector based on the issues brought forward” (Canada, 2021, 15). GBA+ is invoked in Canada’s BE engagement paper specifically as an important tool for ensuring that equity is addressed. Yet, GBA+ has not proven to be a successful framework for addressing social equity issues anywhere within the Canadian government (Hankivsky and Mussell, 2018; Pictou, 2020; Christoffersen and Hankivsky, 2021; Bridges et al., 2023; Moran, 2023), and has not been widely adopted despite the government’s mandate to use it across all departments. Importantly, how GBA+ has been used thus far has focused on identities, which neglects broader systemic inequities that are built into Canada’s institutions and infrastructures. This type of patchy and limited use of GBA+ (as outlined above) focuses on gender/women instead of intersectionality and power and would limit the ability of Canada’s blue economy to address structural issues. While we think the inclusion of GBA+ in Canada’s blue economy planning is an important first step, GBA+ practice will have to continue to evolve beyond its current use in government to ensure that transformative social and environmental change will occur through ocean governance. Thus, we consider Canada’s forthcoming blue economy strategy as a potential policy dead zone if this evolution does not happen.

4.1.2 Equity (and equity zombies) in the blue economy: policy dead zone #2

In the remaining ocean relevant documents analyzed, we did find wording and phrases that addressed some aspects of what we would consider equity and justice, but these were not explicitly labeled as equity focused. For example, section 2.5 of the Fisheries Act considers factors that may be relevant to equity, including (1) Indigenous knowledge, (2) social, economic, and cultural factors, (3) the preservation or promotion of the independence of license holders in commercial inshore fisheries, and (4) the intersection of sex and gender with other identity factors (i.e., the inclusion of GBA+) (An Act to amend the Fisheries Act, 2019). These considerations are important to advancing equity but leave significant space for further definition in regulations and policies under the Fisheries Act as well as for the Minister’s discretion.

Similarly, the federal Impact Assessment Act includes equity-adjacent language in the “Factors to be Considered” in impact assessments. This includes the requirement that “the intersection of sex and gender with other identity factors” be considered, which suggests that impact assessments should take an intersectional approach. The factors also include specific attention to Indigenous people, including the requirement to consider Indigenous knowledge and culture and how projects will impact Indigenous groups and their rights. Critical for what this means for equity will be how Indigenous knowledge and culture are considered.

We found that the lack of explicit, comprehensive, and cohesive definitions of social equity was a second example of a policy dead zone. The way that equity is showing up in the legislation is patchy. This patchiness is most likely a result of how past legislative amendments have addressed social justice and environmental justice concerns in ways that lack overall cohesiveness but also the slowness with which policy change occurs. This is exemplified by the 2019 inclusion of Section 2.5. in the Fisheries Act, which addresses a broader scope of social equity issues than the Act did previously but does not make considering them a requirement. Equity is also referenced in regulations and policy made under the Fisheries Act, including, the New Access Framework 2002 (Andrews et al., 2022). Yet, while this is promising, it remains a decision-making consideration and not a requirement based in regulation. The emergence of gender and equity considerations in environmental legislation is progress, but without regulatory intent, the inclusion of this language risks fading into internal government relations (i.e., corporate governance) rather than policy delivery. We see this, for example in government reporting on the implementation of GBA+ requirements in the Fisheries Act, which highlights how the framework informs the government’s “outreach and engagement activities that showcase the work of scientists” (DFO, 2023 p.15). While our analysis illustrates that equity is becoming more prevalent in government legislation, it also points to how equity considerations are limited because of the broader governance context, specifically the lack of equity scaffolding across regulation and policy at the federal level.

Given the opaqueness regarding equity at the federal level and that Canada’s forthcoming national blue economy strategy will be implemented in regional spaces, we now turn to examples of project approval processes that will allow us to examine how existing equity requirements have played out in actual projects. Despite that impact assessment legislation at the federal level includes GBA+, some of the most important blue economy industries are assessed and approved provincially, such as aquaculture and some oil industry projects. In the next section, we look at two specific examples of regional project approval processes in Newfoundland and Labrador to examine where equity shows up at the regional level. We examine the existing equity scaffolding and whether it will allow for the easy incorporation of what the blue economy strategy is promising.

4.2 Equity zombies in regional project approval: oil and aquaculture

In Canada’s province of Newfoundland and Labrador (NL), both oil and aquaculture have been and continue to be important components of the economy and are emphasized in economic and strategic planning. This was particularly highlighted in 2016 when the provincial government launched its strategic plan, The way forward: A vision for sustainability and growth in Newfoundland and Labrador (Government of NL, 2016). In a press release announcing the plan, oil and aquaculture were not only included in this strategy but were identified as “priority sectors” that will involve technological advancements to solve their unsustainable practices (Government of NL, 2018). In this section we examine equity potential in these two high priority sectors by looking at project approval processes for the Hebron offshore oil project and the Grieg salmon aquaculture project.

4.2.1 Following equity in the oil industry in Newfoundland and Labrador

Exploration for oil in offshore NL began in the 1960s, with the first field, Hibernia, discovered in 1979. Hibernia began producing oil in 1997 and since then, three additional main fields have been developed. The oil industry has been significant economically, especially because of the cod fishery collapse in the early 1990s, which had long been the province’s primary source of economic revenue and employment. Offshore oil in NL is managed jointly by the federal and provincial levels of government through the Canada-NL offshore petroleum board (CNLOPB), the oil regulator. Joint federal-provincial legislation was created in the 1980s to regulate the oil industry, typically referred to as The Accord Acts. The Accord Acts require that both a benefits plan and an environmental assessment is submitted prior to project approval by the CNLOPB.

The Hebron project is NL’s fourth and most recent offshore oil field to be developed. An agreement between the project proponent and the provincial government to move forward on the project was made in 2008, final approval to develop the field was granted in 2012, and the field began producing oil in 2017.

4.2.1.1 Where is equity?

A benefits plan under the Accord Acts is largely focused on local employment and ensuring that provincial and Canadian businesses will benefit from oil industry activities Accord Act, 2015, section 45(1). The Acts do not specifically make reference to social equity; however, they do offer some limited, indirect mention of equity. The Acts state that the CNLOPB “may require” that the benefits “plan include[s] provisions to ensure that disadvantaged individuals or groups have access to training and employment opportunities and to enable those individuals or groups or corporations owned, or cooperatives operated by them to participate in the supply of goods and services used in any proposed work or activity referred to in the benefits plan” Accord Act, 2015, section 45(4).

The environmental assessment (EA) for Hibernia was done under the Canadian Environmental Assessment Act (CEAA), which was the previous legislation guiding EA. While there was no specific GBA+ requirement in this Act, the federal government wide GBA+ mandate would have applied. However, as discussed above, this mandate has not been widely implemented. A search of the Hebron comprehensive study (the specific type of impact assessment required for the Hebron project) found little evidence of equity. Where we did find equity issues and concerns highlighted was in the consultation report, which helps illustrate the kinds of equity concerns the public and stakeholders were expressing to the government (like in the BE What We Heard Report above). Some of these included concerns about diversity in hiring and access to childcare (Stantec, 2010, 12). The consultation report collects these comments and lists where the issues are addressed. For instance, the report lists that further information on concerns about women’s employment and childcare could be found in the benefits/diversity plan.

The Hebron project’s benefits plan includes a diversity plan, the purpose of which was to describe how it would “encourage members of the designated groups (women, visible minorities, Aboriginal peoples, and persons with disabilities) to participate in the Project” (Hebron Project Benefits Plan, 2011, section 3-32). Although the plan states that it includes women, visible minorities, Aboriginal peoples, and persons with disabilities, it also says that most emphasis was placed on women. It specifically states that “given the Benefits Agreement focus on women and considering that demographically women form the largest of the four designated groups, additional focus has been placed on evaluating gender-specific considerations, notably in supporting entry into and advancement within occupational categories where women are historically under-represented” (B-6). The diversity plan is based around four “diversity pillars.” The first is “skills development” which is based on the idea that for there to be diversity the designated groups need more access to education and training. The second pillar is about recruiting and selecting diverse candidates, particularly within the province. The third pillar addresses the workplace environment to ensure that it is supportive, for instance, through workplace training. The last pillar is about accountability and includes collecting and reporting data as well as monitoring. It is important to note that these pillars are all framed around employment.

4.2.1.2 What has this meant in practice?

The CNLOPB’s benefits plan guidelines (CNLOPB, 2022) require that proponents submit publicly available reports each year documenting progress in relation to the goals laid out in the benefits plan. Consequently, Hebron releases annual and quarterly reports on benefits, which involves reporting on how many people in the designated groups (women, aboriginal people, people with disabilities, and visible minorities) are employed in several different categories. It then provides an update on actions being taken under each of the pillars.

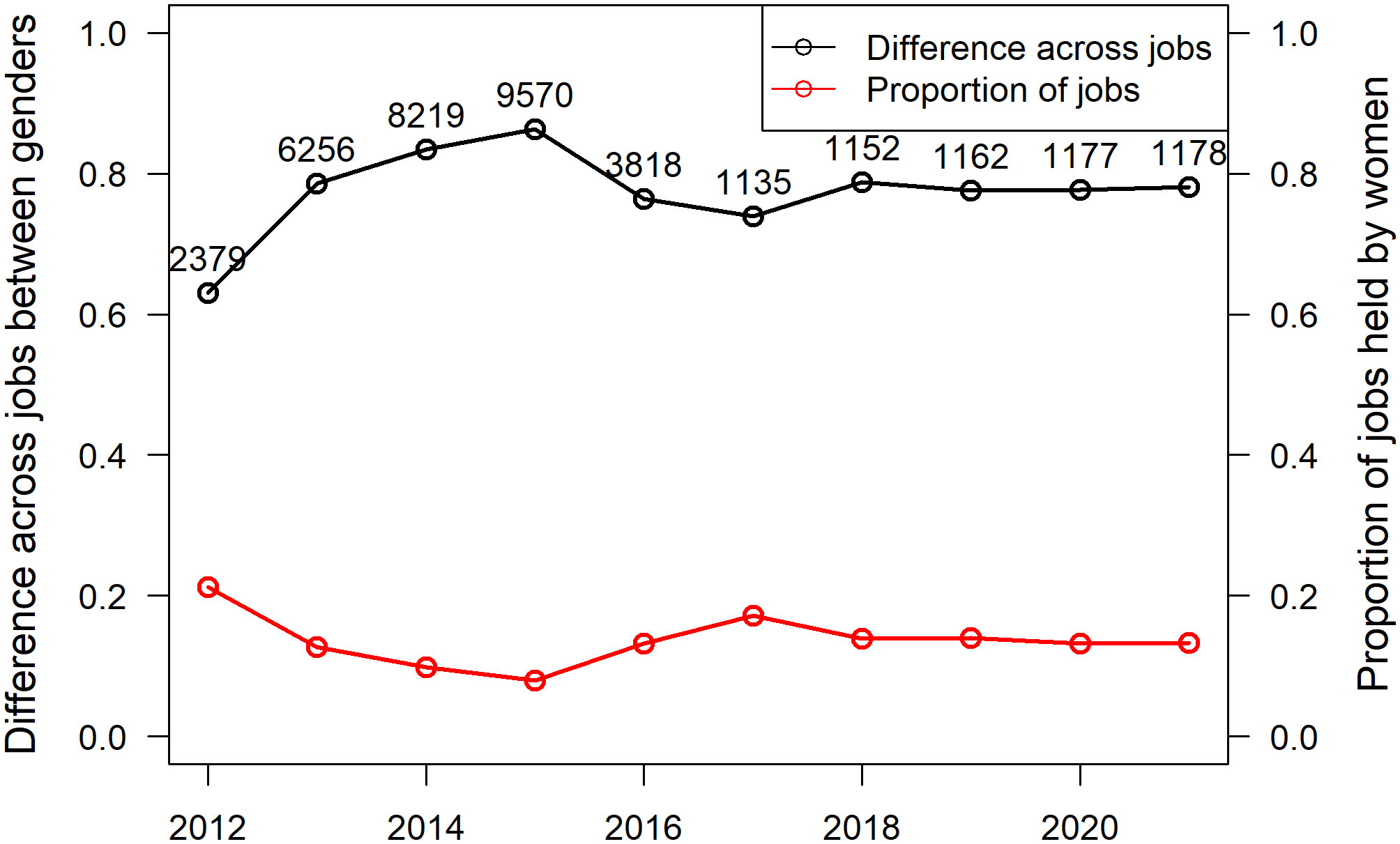

Looking across ten years of employment data for the Hebron project, we find that employment equity between men and women (Hebron did not account for non-binary employees) was greatest in 2012 (the first year of data availability). As the project rapidly hired more people from 2012-2015, the total number of employed men disproportionately grew, meaning that the proportion of employed women decreased with more people hired (Figure 1). When considering the composition of jobs that each gender was employed in, we also found that the multidimensional measure of difference between job compositions across genders increased during times of rapid employment (Figure 2). That is, as the total number of employed people increased, there was a greater division of labor between men and women, with women increasingly hired only for administrative roles and men increasingly hired for all other roles (technicians, management, engineers, labor, trades, etc.) Across all years, from 2012-2021, women never made up more than 26% of the workforce, and in most years, it was 10-15%.

Figure 1 Differences in employment between men and women over time in the Hebron project from 2012-2015. The black line shows the multidimensional difference in job composition between genders, while the red line shows the proportion of jobs held by women. The numbers above the black line shows the total number of employed people in each year.

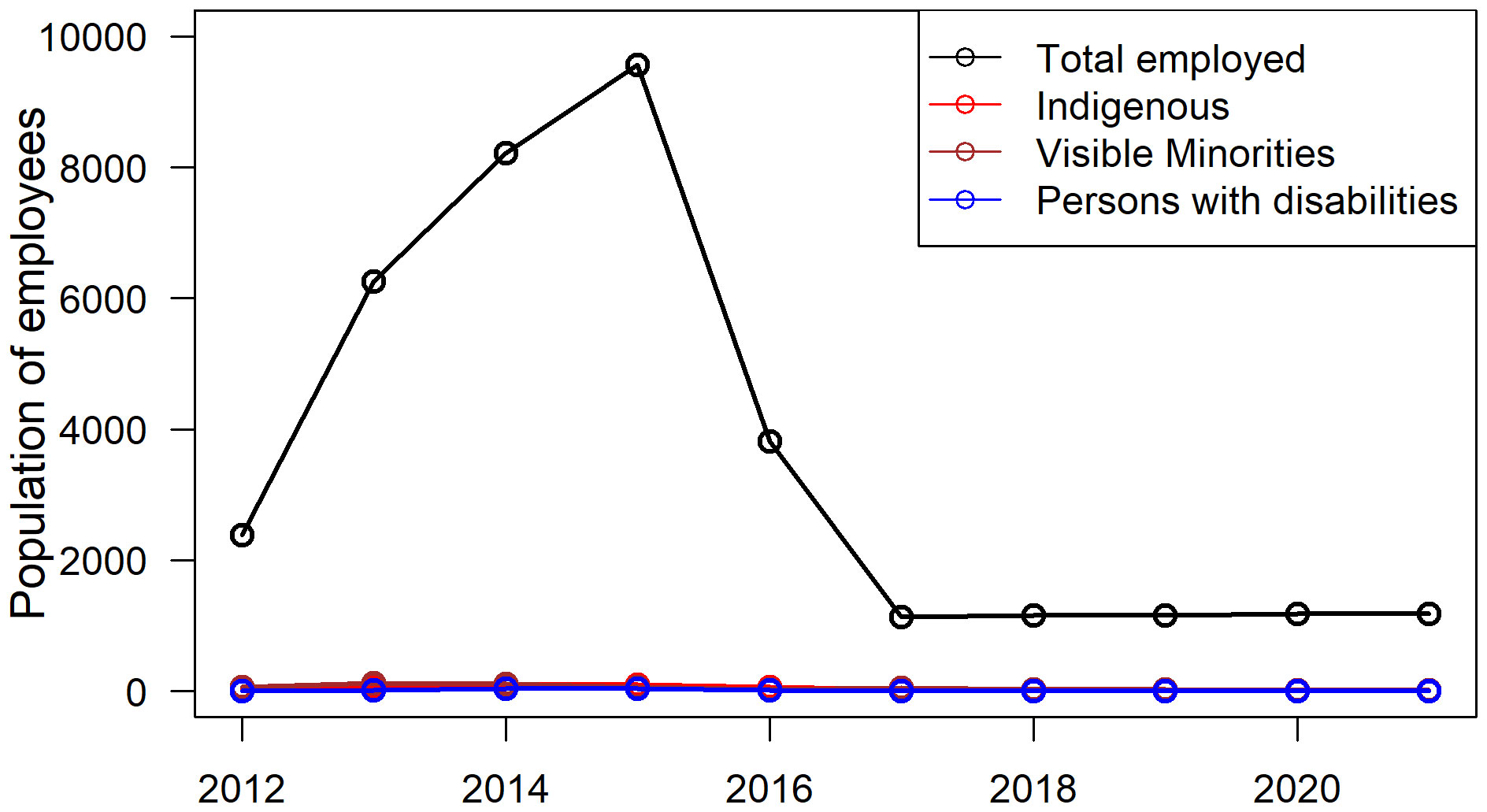

Figure 2 The multidimensional measure of difference between job compositions across genders between 2012-2021. The total number of employed people in the Hebron project (black line) from 2012-2021. The red, blue, and purple lines indicate the total number of employees representing Indigenous people, people with disabilities, and visible minorities.

When considering employment of other underrepresented groups (besides women), we found that the Hebron project rarely hired Indigenous people, members of non-white ethnicities (termed “visible minorities” in the reports), or people with disabilities. Again, during a period of rapid hiring (2012-2015), the employment of these underrepresented groups was stagnant. From 2012-2015, as the total number of employed people rose from 2379 to 9570 (a quadrupling in jobs), the total number of these underrepresented hires only doubled, and at most there were only 256 employees across these groups within a given year (representing very low total numbers of employed people from underrepresented groups). From 2012-2021 the proportion of underrepresented groups employed was between 2-4% of total employees.

4.2.1.3 Why is it important?

How did the benefits plan and its diversity plan address equity? The data discussed above shows that 1) attention to equity is focused on identity (women, Indigenous peoples, visible minorities, and people with disabilities) and, 2) attention is centered on employment. While there were periods where more women were hired, the diversity of women’s roles actually decreased and became more restricted over time. Thus, despite the effort, nothing really changed and even though equity is included, it is limited.

4.2.2 Following equity in the salmon aquaculture in Newfoundland and Labrador

Aquaculture in NL includes the farming of shellfish, aquatic plants, and finfish. Shellfish aquaculture in NL started in the 1960s while finfish aquaculture has been in place since the 1980s. Finfish, specifically salmon, makes up a significant portion of the industry in terms of both volume and value. Since 2016, two large multinational Norwegian salmon aquaculture companies, Mowi and Grieg, have started farming in NL. Mowi entered through the buyout of the New Brunswick company Northern Harvest, while Grieg NL entered through a Memorandum of Understanding (MOU) with the provincial government to farm in a new area of the province (Placentia Bay) with a new method (triploid salmon). Grieg argued that the introduction of triploid salmon would ensure that even if salmon escaped, they would not be able to breed with native Atlantic salmon populations (Grieg, 2016).

Aquaculture in NL is regulated via a memorandum of understanding (MOU) between the federal and provincial governments and multiple pieces of legislation across departments and jurisdictions, including (among others) the federal Fisheries Act, the provincial Fisheries Act, and provincial Aquaculture Act. However, the federal government is currently proposing the passage of a Federal Aquaculture Act, which will have implications for the federal-provincial regulatory relationship, and thus, aquaculture in NL. Within the province, the Department of Fisheries, Forestry and Agriculture (FFA) oversees licenses, permits, and the implementation of policies and regulations of the licenses related to aquaculture developments. The NL Aquaculture Act’s purpose is mainly to support industry development and streamline the provincial/federal policy landscape.

4.2.2.1 Where is equity?

Canada’s Fisheries Act itself does not address equity in any significant way. Section 2.4, rights of Indigenous peoples, and Section 2.5, The decision-making considerations, both pertain to equity. However, the attention to equity issues in Section 2.5 are considerations only. In other words, considerations are not required but optional - they may be considered - as discussed above.

The Provincial Aquaculture Act does not include the term equity at all. It does, however, include attention to Labrador Inuit rights (section 3.1), which means that the regulation of aquaculture in NL is mandated to align with, and be subjected to, the Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement Act (2005). Currently there is no salmon aquaculture in Labrador, so this is not relevant to how salmon aquaculture is being developed and regulated in the province at the moment. Section 4.6 of the NL Aquaculture Act (2016) states that the minister may incorporate into an aquaculture license a wide range of jurisdictional issues, including (health, safety, the environment, sustainable development, resource utilization, standards regarding production use, stocking, and investment of a facility (Aquaculture Act, 2016). This means that the minister holds significant power to incorporate multiple aspects of equity in this section of the Act.

4.2.2.2 What has this meant in practice?

The most recent aquaculture approval processes in NL, the salmon aquaculture project initiated by Greig NL (which was taken over by its parent company Grieg Seafood in February 2020), included 11 sea sites (3 approved, 3 soon to be approved, 5 in various stages of application) (Mutter, 2022). This approval process offers an ideal project to examine as it was subject to the most recent provincial policies and legislation, including GBA+.

The proposed project was registered for Environmental Assessment (EA) review under the Newfoundland and Labrador Environmental Protection Act (NL EPA, Part 10) in February 2016. On July 22, 2016, the project was released from the EA process, meaning that the government did not require a full EA to be conducted. Rather, the release was contingent on Grieg meeting five conditions: 1) limiting the type of salmon raised, 2) providing a report on phased approach to triploid salmon, 3) providing a list of all regulated substances that would be used in the project, 4) providing a report on the workforce and timeline for the project that would be submitted to the Department of Advanced Education and Skills before construction, and 5) creating a women’s employment plan for the project that meets the approval of the Deputy Minister and is submitted to the Women’s Policy Office.

The NL government’s decision to release Grieg from having to conduct a full EA was contentious and the Atlantic Salmon Federation filed legal challenges, which they won, to require Grieg to do a full EA (Quinn, 2017). Grieg was in and out of court between July 2017 and May 2018, but started the EA process as they simultaneously appealed the ruling. However, the requirement for the full EA was ultimately upheld. Grieg NL submitted its EA in May 2018 and the project was released in September with the above conditions still in place. Thus, Grieg was required to report on its women’s employment plan, including employment data on the number of individuals and total work hours for women working at Grieg. The women’s employment plan focuses on “the various measures that GNS will take to help ensure the involvement of a diverse and inclusive workforce during the implementation phase of the Project. This includes measures to enhance and maintain the participation of women in the Project during its various phases” (3).

4.2.2.3 Why is it important?

Did undergoing the full EA process add anything in the way of equity? This is contingent on how we look at and define equity. Without the full EA process, Grieg was already required to complete a women’s employment plan, which exemplifies one common approach to addressing equity. This approach is similar to the original GBA framework implemented by the Government of Canada in the 1990s, which sought to increase the number of women in trades and/or stem, something that is now standard practice in other industries (i.e. oil). However, Grieg does not publish any data on its progress on the women’s employment plan (it only goes to the minister), so we don’t know how this plan has been implemented and what impacts it is having. Additionally, the focus on environmental harms for project approval has increased significantly with the completion of the EA, which included both environmental protection plans and environmental effects monitoring plans (LGL Limited, 2019). Yet even though sustainability is a key term used in these monitoring plans, they do not address the linked social, ecological and economic aspects of the industry. Therefore, the project’s impacts are still siloed, and in ways that restrict considerations of how impacts are documented, who is affected, and how they overlap - an important basis for understanding how equity is advanced in a social-ecological context.

5 Canada’s equitable blue economy

Our two project approval processes in NL allowed us to look at the regional level to explore if and how some relevant legislation and guidance has informed regional and provincial blue economy industry implementation processes. Our findings illustrate that these project approval processes do not include or clearly define equity and sustainability or the mechanisms to implement equity considerations. This suggests that it may be difficult to implement the equitable blue economy Canada aspires to without attention to the multi-scale policy and approval process practices. In this section, we first explore what our two cases tell us about Canada’s ability to meet its blue economy equity ambitions. Social equity only shows up at the implementation stage through hollow, or not fully fleshed out, applications. Thus, we argue that these approval processes represent another type of a policy dead zone that we call an equity zombie. We then explore what might need to change to ensure ocean equity in Canadian blue economy industries at all scales.

5.1 Policy dead zone #3: equity zombies in blue economy project approval processes

In the case of Hebron, the incorporation of equity was a requirement of legislation that was meant to maximize the oil industry’s benefits to people and businesses in the province. In the Grieg project, the project was first approved by the provincial government without the requirement of an environmental assessment — that is, without the requirement for systematically considering environmental and socio-economic impacts of the project. It is interesting to note that in lieu of the full EA, one of the five conditions of approval was a report (with annual updates) on the state of women’s employment in the industry, something similar to the limited inclusion of equity in the Hebron project. This particular condition for Grieg’s project approval was likely required to fulfill a commitment made as part of phase two of The NL Government’s Way Forward initiative. Under this initiative, the government committed to require women’s employment plans on infrastructure projects in NL starting in 2017-18 (Government of NL, 2017). That being said, we could not make a direct link between this requirement and Greig’s women’s employment plan. Despite requirements to work toward equity in both the Hebron and Grieg projects, diversity seemed to be largely equated with the inclusion of women.

Additionally, when we looked at how women’s employment numbers by occupation had changed in the Hebron project, we found that women largely remained siloed in traditional gendered occupations and that this solidified over time. In fact, during periods of hiring booms, roles became more segregated by gender, as women were largely only hired for administrative roles and the difference in roles between genders became more pronounced. This suggests the importance of examining how other blue economy projects and industries are hiring and maintaining gender segregation in employment opportunities.

It is also important to consider whether the new Impact Assessment Act (IAA) will lead to any real changes in how equity is considered in project approval processes. The Hebron project was approved under the previous impact assessment legislation, which did not include GBA+ requirements. Projects assessed under the new IAA will most likely maintain a lens on employment equity, the question now is whether they will move beyond this. Moreover, if so, will the different areas assessed remain siloed or actually draw on the intersectional lens that GBA+ is built on? For instance, the new IAA not only has a requirement for incorporating “the intersection of sex and gender with other identity factors” but also an emphasis on Indigenous people and rights. For project approval processes to actually consider equity more fully, they would require, for instance, considering Indigenous identity and the colonial relations that led to land and decision making power over land being stolen. This involves more than consultation, which has long been a requirement of impact assessments. It would involve incorporating the history of colonialism and Indigenous identity and sovereignty into the process. Therefore, if Canada’s blue economy framework takes up equity with a feminist framework, including the current GBA+ framework that has already been mandated, the process would need to look different. For example, Indigenous involvements in EAs would be more than advisors or stakeholders in consultation. Indigenous values and management frameworks would be given as high a standing as western science, meaning that project approval processes could be stopped if Indigenous science deemed them harmful to people or environments.

In summary, our analysis showed that the term equity only showed up in ways unrelated to social equity or was used but not defined. This is not to say that equity is not addressed at all in the projects we examined, but rather that how it was used--and the existing policy and legislative context that governs these projects-- is not consistent with Canada’s emerging blue economy approach (i.e. as transforming social and environmental inequities and injustices). Equity as a term rarely shows up in documents that are relevant for ocean/blue economies and where it does it is weak or specific to women. In other words, equity is not completely absent but rather is undeveloped or without substance. Women and gender are conflated while the gendered dynamics that affect those who identify as man, woman, or non-binary are ignored. Thus we see that GBA+ has been limited in its ability to address equity beyond individual identity and that it has largely been used to address the employment of women. For example, Greig’s project approval processes included a women’s employment plan while Hebron included a diversity plan, which was slightly broader in who it was targeting, although in practice it was almost entirely women. Thus, we see again that GBA+ is used as a tool for corporate governance to work toward binary ideas of gender parity in staffing, which while important, is both narrow and shallow in its execution of addressing inequities because of the lack of intersectional analysis being included. This highlights a serious temporal and geographic incongruence in how equity is being used and offers an example for how equity is translated across governance jurisdictions.

We refer to this use of equity as an equity zombie. Just as most popular conceptions of zombies are reanimated physical shells of fully fleshed out people, equity is being referred to in ocean relevant policies and even reanimated (i.e. GBA+). Thus, similar to a zombie, current uses of equity and GBA+ (with its recommendation for an intersectional analysis) in ocean-based industries have been revived from older policy approaches (e.g. GBA) but in ways that do not add substance and in some cases provide cover for industries to advertise themselves as environmental and equity champions while continuing to do business as they always have. They remain empty shells and not fully fleshed out policies and practice, at least in the project approval cases we looked at.

6 Potential solutions: feminist climate justice equity framework

Business as usual economies (and this would include Canada’s blue economies both historically and currently) are structured and organized around “the logics of uninterrupted growth, social and geopolitical hierarchies, and anthropocentric conceptions of the non-human world” (Bell et al., 2020, 3). In other words, business as usual is inherently inequitable and unjust. Addressing this inequity requires questioning business as usual development plans. In the context of blue economies, this includes questioning the new technologies these plans often include to achieve sustainability. All too often, these technologies, and thus the plans based on them, are rooted in the same social, economic, governance, and scientific structures that created the current environmental/climate crisis. Consequently, an industry labeled “green” (or blue) is not necessarily or automatically just and equitable. For instance, the electric car industry is often framed as a climate crisis solution while the environmentally destructive practices of rare earth mineral mining needed for electric car batteries are overlooked (Widmer et al., 2015). Indeed, aquaculture and oil are often included in blue economies and framed as sustainable despite their significant negative environmental impacts. Yet, the Government of NL and the Government of Canada both include these industries in their planning for future blue economies based on expected future technological advancements that will make them sustainable. For instance, the government is supporting decarbonizing technologies in the oil industry that will make oil production “cleaner” all the while ignoring the broader climate and justice implications of maintaining and expanding fossil fuel production (Fusco et al., 2022). Even when there is a focus on achieving equitable blue economies by governments, efforts are easily co-opted by corporations, do not address structural inequities, and thus maintain or even exacerbate existing social and environmental injustice and inequity.

Our analysis highlights the need for a direct engagement with social and environmental equity issues, including a more cohesive approach to ocean equity that will cross scales of blue economy discourse, policy, and implementation. In other words, if Canada’s blue economy is going to represent a solution to climate change and climate inequities (which it has committed to through its participation in the Ocean Panel), it will need to think about and implement equity differently. Given that Canada has also committed to GBA+ and intersectionality broadly throughout government, it makes sense to draw on scholarship that has engaged with equity in comprehensive ways.

Critical feminist, environmental justice, and climate justice work on social and environmental equity could inform work toward transformative blue economies if incorporated into policy and management. Feminist insights on climate justice and energy transitions offer depth and breadth to understanding inequities that would reshape climate solutions. These perspectives are based on finding solutions that address underlying structural inequities and injustice, which would involve the analysis and incorporation of power dynamics in the creation of policy as well as the examination of how these dynamics play out in specific places and across temporal and geographic scales (Sultana, 2022; Mikulewicz et al., 2023). As Sultana argues, the climate crisis is about morality and justice as much as it is about the economy, finance, and technology, and thus we need to get at the root causes of the issue to achieve accountability and change. However, the policy infrastructure to put this work into practice would need to be built and dead zones addressed.

We offer a potential way to work towards building this policy infrastructure by drawing on insights from ocean scholars arguing for the inclusion of the environment as a key aspect of social equity (i.e Bennett et al., 2021) and critical scholars looking at energy justice (Bell et al., 2020; Sovacool et al., 2023). We find the Sovacool et al. (2023) paper, titled Pluralizing Energy Justice, particularly useful. While this paper provides a framework to guide future energy justice research and practice, its recommendations are pertinent to the development of Canada’s blue economies. Thus below, we rework Sovacool et al.'s (2023) key themes on equity from their engagement with feminist, Indigenous, anti-colonial and anti-racist scholarship to highlight key recommendations for Canada’s blue economy planning. Note, we did not rework the last theme as it also applies broadly to ocean justice and blue economies. We present these themes as seven questions that can enrich dialogue about moving existing and emerging ocean industries toward better alignment with equitable blue economy goals. Furthermore, since these questions arise from the need to fill in dead zones, we imagine them as important conversation starters that will most likely need to be expanded and adapted for geographical and cultural contexts. After considering context, these questions can be used to guide governments in the incorporation of equity in future blue economy planning, policies, and evaluation. The questions are as follows:

1) How can pluralist decision making that includes a voice/vote for affected people, other animals, and the environment be the standard for future ocean development?

2) How can the past and potential future harm and violence of ocean economies, including those happening across time and space, be acknowledged and mitigated?

3) How can reconciliation as well as anti-colonial and de-colonial initiatives that would give property and control over ocean spaces back to Indigenous peoples/communities/non-humans in Canada be achieved?

4) How can the ocean be recognized beyond commodification, including non-commodified types of ocean engagement of community members and organizations? This could include recognizing the economies of care and social reproduction within maritime communities as well as the importance of oceans for other animal communities.

5) How can the social economic systems and relations that create and maintain marginalized groups in Canadian society be addressed, redressed, and not further entrenched in future ocean developments? This could include addressing the economic systems/policies that lead to environmental externalities in the ocean, migrant labor unfreedoms in seafood and seafaring, and inequities caused by technological innovations in emerging blue economies.

6) How can power dynamics that create injustices and inequities be given adequate attention?

7) How can we achieve, “[i]nclusion, abolition, and disruptive justice, [and] actively correcting wrongs within and beyond the judicial system, to include reparations, land [and we would add ocean] reform, and debt cancellation” in Canada?

7 Conclusion

Despite a global increasing interest in ocean equity, equity is still often ill-defined at national and regional scales. In this paper, we asked whether Canada’s current legislative and policy frameworks (the ones under which many blue economy activities will fall) provide the necessary breadth and depth in their equity considerations to allow for the implementation of equitable blue economies. We found that Canada’s current ocean policies that aim to achieve economic development and conservation, while often ostensibly equity focused, ultimately lack a clear approach to the incorporation of equity. Indeed, we found that incorporation and implementation of equity in Canada is disjointed and inconsistent.

In looking for equity in and across policies and legislation relevant to Canadian blue economies, we took a scalar approach by following equity in these documents from the federal level through to project approval processes. This approach reveals policy areas - what we call dead zones, where equity gets lost in implementation. For example, federal impact assessment legislation now requires some analysis of equity through its requirement of GBA+. However, regional blue economy industries that will be included in the broad Canadian blue economy strategy sometimes fall under provincial legislation, where equity considerations are minimal or non-existent. Additionally, even when equity-adjacent actions were showing up (as was the case with women employment plans in both oil and aquaculture approval processes) the result was a narrow focus on increasing women (and sometimes Indigenous) people. However, there was no attention paid to the patriarchal structure of work and society in Canada or different Indigenous communities. Although dead zones are easily overlooked or hidden, our scalar approach allowed these dead zones to come to light, thus allowing us to identify where more attention may be needed to reach broader equity goals, such as those Canada has committed to through the Ocean Panel.

However, achieving these equity goals and transformative change in the oceans will require more than just identifying where more attention is needed. It will require understandings of equity that are more comprehensive, attuned to historic and structural factors that entrench and amplify advantages and disadvantages, and that are integrated across all scales of policies. Moreover, it will require consideration of the interplay among and across scales of policies and governance actors where policy dead zones are occurring. Our goal here is to highlight the opportunity that Canada has for truly transformational action as it reorients its ocean and marine governance with the adoption of international blue economy ambitions.

We began this paper with a quote from law professor Janel George when she spoke at the 2022 African American Policy Forum Critical Race Theory Summer School. She stated that, “If we use the wrong frame to understand the problem, we come up with the wrong solution” (CRT Summer School, Janel George, July 20, 2022). We come back to this now to highlight how the equity frame used in the development of Canada’s blue economy is incomplete at best. If Canada is intent on building equity into its future blue economy, it will need to move beyond existing understandings and practices of GBA+ to embrace and incorporate deeper and more rigorous engagements with equity that will lead to its implementation at (and across) different scales of policy and practice. This is also important for all coastal nation-states that have signed onto the Ocean Panel and are currently developing blue economies.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Author contributions

CK: Conceptualization, Methodology, Project administration, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. LF: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. JD: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. EA: Methodology, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. GS: Methodology, Writing – review & editing.

Funding

The author(s) declare financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article. Funding was received from the Nippon Foundation Ocean Nexus Center at EarthLab, University of Washington.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared that they were an editorial board member of Frontiers, at the time of submission. This had no impact on the peer review process and the final decision.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2024.1277581/full#supplementary-material

Supplementary Material A | Methods for Analysis of Employment Equity for Hebron Project.

References

Andrews E. J., Cheunpagdee R., Stanley N., Neis B., Foley P., Command R., et al. (2022). Thirty Years from the Brink: Governing through Principles for Newfoundland and Labrador’s Small-Scale Fisheries since the Groundfish Moratoria and Prospects for the Future. Ocean Yearbook 36, 239–267. doi: 10.1163/22116001-03601009

An Act to amend the Fisheries Act and other Acts in consequence, SC 2019, c 14. (2019). Available at: https://canlii.ca/t/53rg1 (Accessed August 11, 2023).

Labrador Inuit Land Claims Agreement Act (S.C. 2005, c. 27). (2005). Available at: https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/L-4.3/.

Barsh R. L. (2002). Netukulimk past and present: Mikmaw ethics and the Atlantic fishery. J. Can. Stud. 37 (1), 15–42. doi: 10.3138/jcs.37.1.15

Bell S. E., Daggett C., Labuski. C. (2020). Toward feminist energy systems: Why adding women and solar panels is not enough. Energy Res. Soc. Sci. 68, 101557. doi: 10.1016/j.erss.2020.101557

Bennett N. J., Katz L., Yadao-Evans W., Ahmadia G. N., Atkinson S., Ban N. C., et al. (2021). Advancing social equity in and through marine conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 711538. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.711538

Bond P. (2014). “Climate justice,” in Critical environmental politics. Ed. Death C. (London: Routledge).

Bridges A., Zacharuk B., Tuglavina. J. (2023). Shared Responsibilities: Indigenous Lens GBA+ in Impact Assessments (Impact Assessment Agency of Canada: Keepers of the Circle & AnânauKatiget Tumingit Regional Inuit Women’s Association of Canada. IAAC Invitation to Voices Project).

Canada (2021). The blue economy engagement paper. Department of Oceans and Fisheries Canada. Available at: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/about-notre-sujet/blue-economy-economie-bleue/engagement-paper-document-mobilisation/part1-eng.html (Accessed August 11, 2023).

Canada (2022a). Engaging on Canada’s Blue Economy Strategy, What We Heard. Available at: https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/library-bibliotheque/41030503.pdf (Accessed August 11, 2023).

Canada (2022b). What is Gender-based analysis plus. Available at: https://women-gender-equality.canada.ca/en/gender-based-analysis-plus/what-gender-based-analysis-plus.html (Accessed December 11, 2022).

Christoffersen A., Hankivsky O. (2021). Responding to inequities in public policy: Is GBA+ the right way to operationalize intersectionality? Can. Public Administration 64 (3), 524–532. doi: 10.1111/capa.12429

CNLOPB (2022). Canada Newfoundland and Labrador Benefits Plans Guidelines. Available at: https://www.cnlopb.ca/wp-content/uploads/guidelines/benplan.pdf (Accessed August 11, 2023).

Collard R. C., Harris L. M., Heynen N., Mehta L. (2018). The antinomies of nature and space. Environ. Plann. E: Nat. Space 1 (1–2), 3–24. doi: 10.1177/2514848618777162

Crenshaw K. (1989). Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist policies. Univ. Chicago Legal Forum 1, 139–167.

DFO. (2017). 2017-2018 Departmental Review Results. Available at: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/dpr-rmr/2017-18/drr-eng.html (Accessed December 19, 2023).

DFO. (2022). 2021-2022 Departmental Review. Available at: https://www.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/dpr-rmr/2021-22/SupplementaryTables/gba-eng.html#B3.2 (Accessed August 11, 2023).

DFO. (2023). 2023-24 Departmental Plan. Available at: https://waves-vagues.dfo-mpo.gc.ca/library-bibliotheque/41099977.pdf (Accessed December 20, 2023).

Falzon D., Batur P. (2018). “Lost and damaged: Environmental racism, climate justice, and conflict in the Pacific,” in Handbook of the sociology of racial and ethnic relations. Ed. Batur P. (New York: Springer Press), 401–412.

FAO. (2022). Blue Transformation - Roadmap 2022–2030 (Rome: A vision for FAO’s work on aquatic food systems). doi: 10.4060/cc0459en (Accessed August 11, 2023).

Frost N., Teleki K. (2020) December 2. 5 Pillars of a new ocean agenda (World Resources Institute). Available at: https://www.wri.org/insights/5-pillars-new-ocean-agenda (Accessed August 11, 2023).