- 1State Key Laboratory of Water Environment Simulation, School of Environment, Beijing Normal University, Beijing, China

- 2Qingdao Key Laboratory of Coastal Ecological Restoration and Security, Marine Science Research Institute of Shandong Province, Qingdao, China

Identifying the relationship between fish aggregations and artificial reefs (ARs) is important for optimizing reef structures and protecting marine resources subjected to external disturbance. Yet, knowledge remains limited of how the distribution of fish is affected by shelter availability provided by different AR structures. Here, we tested the effects of two structural attributes on the distribution of a benthic juvenile reef fish (fat greenling, Hexagrammos otakii). We used a laboratory mesocosm experiment with a simplified reef unit that was made of covered structure and non-covered structure. The covered structure was defined as the area inside ARs that provided effective shelter. The non-covered structure was defined as the area along the edge of ARs, which attracts fish but has lower sheltering effects. Four scenarios of two orthogonal structural attributes contained in a reef unit were implemented: size of covered structure (small shelter versus large shelter) and size of non-covered structure (small edge versus large edge), forming three size ratios of shelters to edges (low, medium, and high). The sheltering effects of the four scenarios were evaluated based on changes to the distribution patterns of fish under disturbance. We found that the reef with a large shelter had a better sheltering effect than the reef with a small shelter, but was limited by its small edge, especially when fish density was high. In contrast, the sheltering effect of the reef with a small shelter was limited by its large edge compared to the small edge. Thus, a moderate shelter-edge ratio enhanced the ability of juvenile fat greenling to elude external disturbance. Our findings highlight the importance of quantifying how the structural composition of reefs affects fish distributions, providing guidance to optimize AR structures.

1 Introduction

Artificial reefs (ARs) are submerged structures that are placed on substratum, and are used globally for the protection, regeneration, and concentration of marine resources, and/or to enhance fisheries (Becker et al., 2018; Lima et al., 2019). ARs have been widely implemented to enhance biological communities globally (Ramm et al., 2021). How ARs impact marine resources is typically assessed by comparing the abundance, diversity, and community composition of fish between ARs and adjacent habitats (Komyakova et al., 2019; Lemoine et al., 2019; Wu et al., 2019; Paxton et al., 2020), with a focus on the spatial distribution of fish aggregations (Smith et al., 2017; Becker et al., 2019). Shelter availability provided by ARs contributes towards regulating population density, especially for fish that use shelter (Johnson, 2006; Ford and Swearer, 2013; Teichert et al., 2017; Pondella et al., 2022). Dense aggregations of fish typically form in areas containing ARs (Smith et al., 2015). However, such aggregations might also negatively impact the protection of biological resources, because of potential increased fishing (Islam et al., 2014) and predation (White et al., 2010; Fernandez-Betelu et al., 2022), or intraspecific competition of reef fish for limiting resources of shelter (Kerry and Bellwood, 2016).

Caley and StJohn (1996) proposed that ARs could provide different amounts of two types of shelter: permanent shelter, such as small holes, which physically excludes predators; and transient shelter, such as increased structural complexity, which increases the probability of prey escaping, rather than excluding predators. The authors conducted an experiment to separate how these two types of shelter affected the assemblage structure of reef fish, but found no indication that permanent shelter provides greater protection to prey species than transient shelter. One artificial reef module contains two types of structure: covered structure and non-covered structure, which are respectively similar to internal complexity (or “void space”) and external complexity (or “rugosity”) proposed by Blount et al. (2021). The cavities in the reef are characterized by number of holes and volume of space (Lindberg et al., 2006; Langhamer and Wilhelmsson, 2009). These cavities form the covered structure that limits the entry of predators. The outer walls (surface) of the reef are characterized by the total size and surface area of the reef (Blount et al., 2021). These walls serve as the non-covered structure, which has lower sheltering effects than the covered structure.

Enhancing the sheltering effect is important in the design of ARs. Field observations show that a higher level of the non-covered structure factors of the reef enhances its capacity to support more fish accumulating (Lindberg et al., 2006; Menard et al., 2012). In parallel, lower non-covered structure sometimes supports higher fish densities (Gatts et al., 2014; Granneman and Steele, 2015; Hylkema et al., 2020), due to a high level of the covered structure factors such as more holes, internal space, and spacing between structures, enhancing the survival of reef fish (Hackradt et al., 2011; Ford et al., 2016; Gregor and Anderson, 2016).

Because environmental conditions and intraspecific relationships vary widely in the natural environment (Sinopoli et al., 2015), it is often difficult to establish how covered and non-covered structures affect the distributions of fish under field conditions. AR structures tend to be optimized by measuring their hydrodynamic effects (e.g., upwellings and back eddies) under laboratory settings (Kim et al., 2016; Ma et al., 2022; Nie et al., 2022). For example, a smaller opening ratio (i.e., ratio of the projected area of the cut-opening hole to the whole projected area of the reef surface) could enhance the upwelling and back eddy fields to provide favorable conditions for reef fish (Fu et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2018; Yu et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021). Reef structures are optimized based on hydrodynamic processes because the distributions of fish are hypothesized to be controlled by the stress of environmental factors. However, such hypotheses do not consider how AR structures affect intraspecific relationships, which could lead to a misunderstanding of the non-linear relationship between reef structures and biological distributions.

Here, we explored how the availability of shelter in ARs affects the distribution of a juvenile reef fish (Hexagrammos otakii). To do this, we used a laboratory mesocosm experiment with simplified reef units. Specifically, we: (1) investigated how covered and non-covered structures of reef units affected fish distributions at the laboratory scale, and (2) identified which structural combinations (covered and non-covered structures of different relative sizes) were more likely to enhance the sheltering effect of reefs. Two structural attributes (i.e., size of covered shelter × size of non-covered edge) of the reef unit were tested in relation to different fish densities to quantify how they distribute around the reef unit. Then, the sheltering effect of each reef unit under disturbance conditions was analyzed, and the optimal ratio for the size of the shelter to edge was identified. We expected that the shelter and edge would have a combined effect on fish distribution. We predicted that: (1) the reef unit with a larger shelter would have a better sheltering effect; and (2) the relative size of the shelter to edge of the reef unit would limit sheltering effects. Our results are expected to help optimize the design of AR structures and provide quantitative methods to assess AR performance.

2 Materials and methods

2.1 Study species

Fat greenling, Hexagrammos otakii, is a benthic cold-water reef fish that is widely distributed on temperate rocky reefs in the coastal areas of northern China, Korea, and Japan (Kwak et al., 2005; Kimura and Munehara, 2010; Liu et al., 2019). Larvae develop as plankton. After settlement, reef-associated juvenile and adult fish inhabit benthic habitat (Li et al., 2020). Fat greenling is an economically important species for fisheries, and is a key species for breed-and-release programs along the coasts of the Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea of China (Sui et al., 2017; Zhao et al., 2021). However, this species has been overharvested, and captured individuals have become smaller in size (Sun et al., 2014). Therefore, we selected fat greenling as a model species to examine aggregation patterns around ARs and to propose the optimal design of these structures. Juvenile fat greenling have similar behavioral characteristics to adults, but are more dependent on reefs. Fat greenling are relatively inactive compared to other fish species (Zhang et al., 2021), and juveniles mostly rest on the bottom surface when not foraging (Liu et al., 2018). They are ideal subjects for experimental tests on the simplified attributes of reef structures, as the horizontal distribution of these fish can be easily observed.

2.2 Experimental design

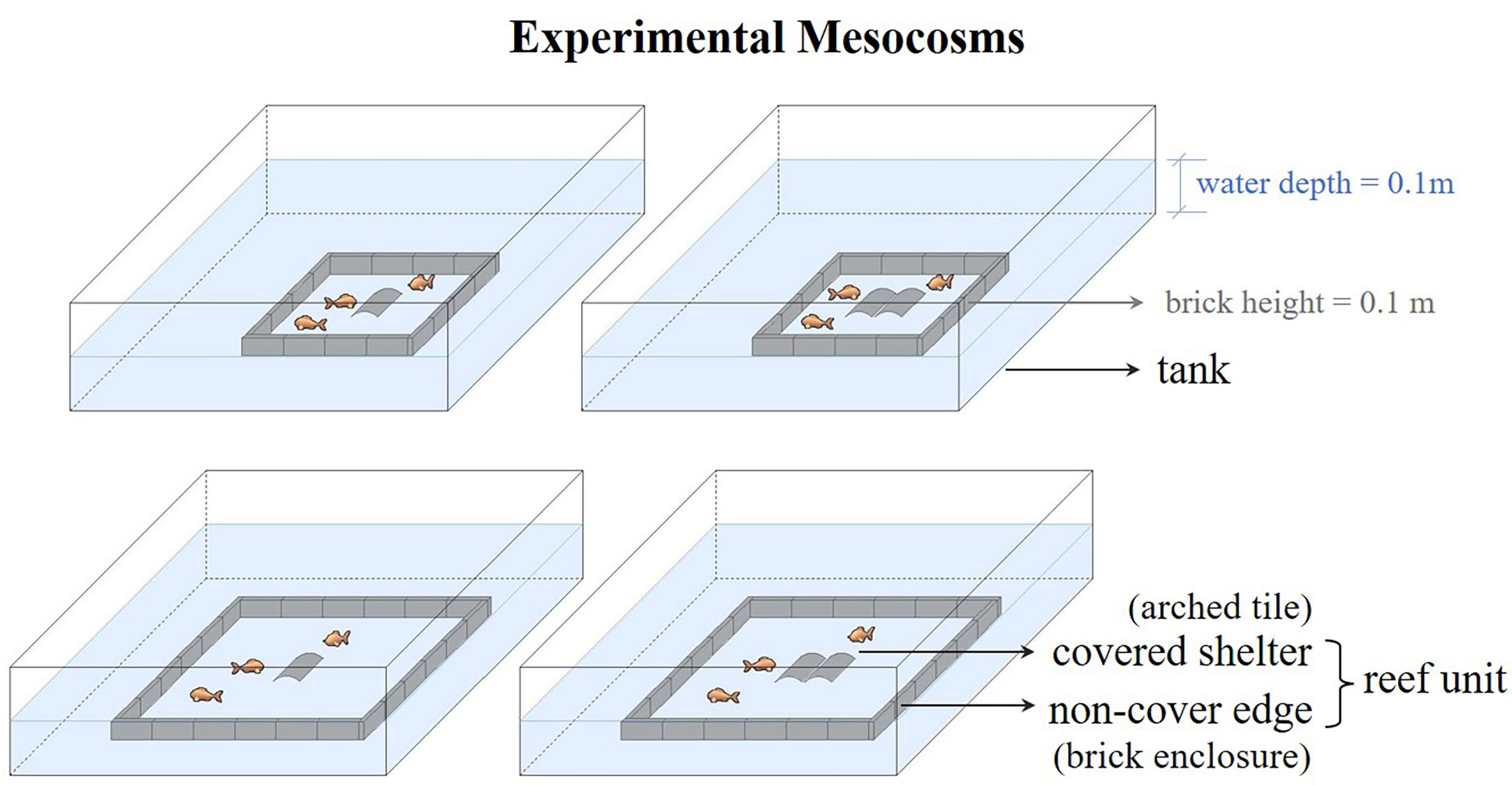

The mesocosm experiment was conducted from October 25 to December 7, 2020, in an aquaculture workshop at Shandong, China (37.19 N, 122.58 E). The experimental tanks (2.0 × 2.0 × 0.5 m, width × length × depth) were part of an indoor flow-through seawater system equipped with mechanical and biological filters. The water temperature in the tank was maintained at 8.6 ± 0.5 °C, and the salinity was close to that of natural seawater (32.44 ± 0.07 ppt [mean ± SE]). One experimental reef unit was constructed in the center of each tank. Each tank was provided with air stones in four corners to provide dissolved oxygen (6.33 ± 0.59 mg/L [mean ± SE]). The air stones did not affect the static water environment around the reef unit, and were positioned to avoid disturbing fish and obstructing observations. Each tank was illuminated with white LED lights during the day, to simulate the local photoperiod (11 light: 13 dark). Each reef unit was designed to contain both covered and non-covered structures. Specifically, the reef unit was composed of a square enclosure made of bricks, and a central shelter made of arched tile(s) (Figure 1). Fish movement was restricted to within the brick enclosure during the experiment by keeping the water level at brick height (height = 0.1 m). The opening of the arched tile (arch height = 0.06 m) allowed fish to enter. The arched tile(s) had a covered shelter with an internal space for effective protection. In contrast, the brick enclosure could attract fish but still expose them to risk (e.g., predation, fishing, and anthropogenic noise as if in the wild). This simplified structure of the reef unit was based on the solid cubic reef with a cavity in the center. The cubic reef was manipulated for the shelter experiment of Lindberg et al. (2006). However, it was possible to observed the internal distribution of fish in the reef unit in our experiment because it was not solid in the vertical plane. We considered the brick enclosure to be the non-covered edge, and used the perimeter of the projected area of the arched tile(s) to describe the size of the covered shelter.

Figure 1 Schematic of the experimental mesocosms designed to detect how shelter availability affected the distribution of juvenile fat greenling, Hexagrammos otakii, a benthic reef fish. The covered shelter (made of arched tile(s)) and non-covered edge (made of a brick enclosure) made up one reef unit placed in the tank. Water level was kept at brick height to restrict fish to move to within the reef unit.

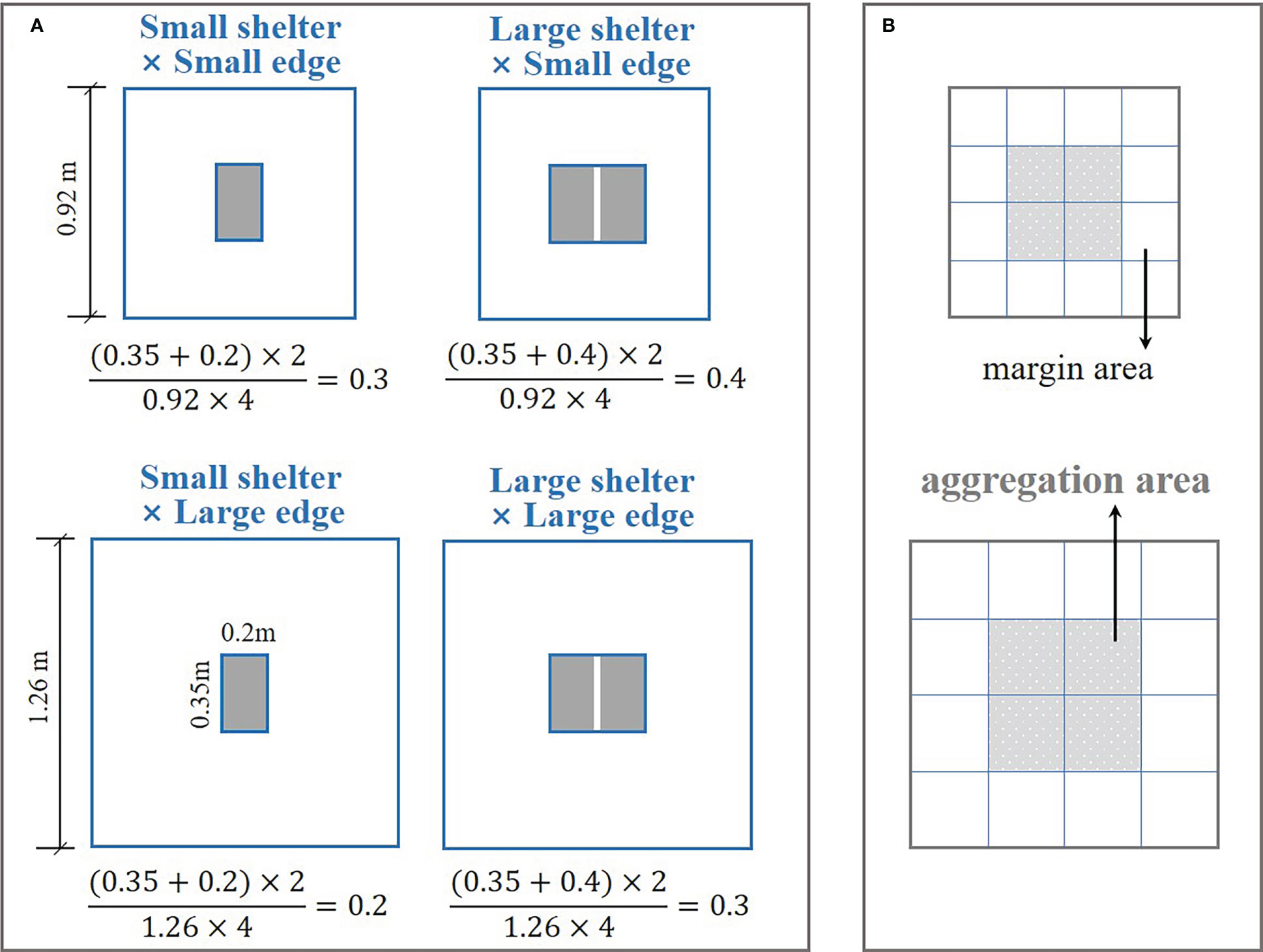

Two covered shelters of different size (small shelter and large shelter) were paired with two non-covered edges of different size (small edge and large edge) orthogonally to generate four treatments for reef unit structure (Figure 2A). Three relative sizes of shelters to edges were set: (1) small shelter × large edge, low ratio = 0.2; (2) small shelter × small edge and large shelter × large edge, medium ratio = 0.3; (3) large shelter × small edge, high ratio = 0.4. The bottom surface of each reef unit was divided into a 4 × 4 grid with a thin string (diameter = 1 mm), which allowed the distribution of fish to be recorded. The central 2 × 2 grid was termed the aggregation area, and the remaining grid was termed the margin area (Figure 2B). A fisheye camera was hung above the tank, and was connected to the computer to monitor fish activity remotely in real-time.

Figure 2 Schematic of the reef unit platform showing the size of the structural attributes. (A) Four treatments of reef unit structure: small shelter × small edge (medium ratio = 0.3), large shelter × small edge (high ratio = 0.4), small shelter × large edge (low ratio = 0.2), large shelter × large edge (medium ratio = 0.3). The equations show the calculation process for the size ratio of the shelter to edge. (B) Bottom partition of the reef unit (i.e., 4 × 4 grid). Gray squares represent the aggregation area around the central shelter, and blank squares represent the margin area.

Juvenile fat greenling were reared from artificially fertilized eggs that hatched in November, 2019. Healthy fish (standard length: 108.9 ± 10.2 mm; wet weight: 16.37 ± 2.91 g [mean ± SE]) were housed in a temporary tank for one week to acclimatize. Fish were fed commercial dry pellets (moisture ≤ 10.0%; crude protein ≥ 51.0%; crude lipid ≥ 10.0%; crude fiber ≤ 2.0%; crude ash ≤ 16.0%; lysine ≥ 2.5%; total phosphorus: 1.5–3.0%) once a day before the experiment. Fish were randomly selected and divided into seven density groups: 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, 28, and 31 individuals per reef unit (ind/unit). No fish died during the experimental period. Therefore, the experiment was a three-factor, fully crossed design (conspecific density [seven levels], shelter size [two levels], and edge size [two levels]), with 28 treatments. The experiment was run six times for each fish density (i.e., six different groups of fish), with six replicates per treatment.

2.3 Data collection and analysis

Fish from each trial were transferred from the temporary tank to the experimental reef unit, and were allowed to acclimatize for 24 h. On the subsequent day, the experiment was implemented and the distribution of fish was recorded on the camera every 20 min for 7 h, with 20 records per trial. The mean value of these 20 records was used to delineate fish distributions in each trial. Fish were not fed during the observation period to avoid disturbance. After the fish distribution was observed, we added an external disturbance to startle fish. This involved striking the surface of the water with a stick. We then recorded the distribution data again.

The aggregation rate (R) and number of occupants (N) (i.e., the number of fish per occupied tile) were used to quantify the full distribution dataset for the condition without disturbance. The aggregation rate (R) was defined as the ratio of the number of fish distributed in the central 2 × 2 grid (aggregation area in Figure 2B) relative to the total number of fish. The aggregation rate (R) in each trial was calculated as:

where di is the number of fish distributed in the aggregation area at time point i; d is the total number of fish in the reef unit; n is the number of experimental records in a trial, and n = 20.

The number of occupants (N) was calculated by subtracting the number of fish outside the shelter from the total number of fish, and then dividing this value by the number of tiles. This calculation produced the average number of fish in each tile when two tiles were present. The number of occupants (N) in each trial was calculated as:

where fi is the number of fish outside shelter at time point i; m is the number of tiles, and m = (1, 2).

It was assumed that fish that entered shelter after being frightened obtained effective protection; thus, we defined the protection rate (P) of every reef unit structure as the proportion of fish in the shelter after disturbance to the total number of fish, to evaluate the sheltering effect of the reef. The average number of fish in each tile after disturbance (Nafter) was also calculated.

We first used three-way ANOVA to test whether the aggregation rate (R) differed among the following factors: shelter size, edge size, conspecific density, and we included all interaction terms. Post-hoc multiple comparisons were made with Tukey’s tests, to find which mean values differed significantly. We then used a linear regression between the aggregation rate (R) and protection rate (P) across all reef unit structures to test whether the pattern of fish distribution could be used to infer the sheltering effect of the reef unit. We also compared the effect of the three listed factors on the number of occupants (N) and Nafter respectively, using one-way ANOVA (followed by Tukey’s test if the ANOVA result was significant). In addition, we used the T-test to compare the difference between N and Nafter for each combination of reef structure and conspecific density. All analyses were preceded by a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test to detect normality of data, and by Levene’s test to detect heterogeneity of variance. All statistics were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics 22.

3 Results

3.1 Distribution patterns

3.1.1 Aggregation rate

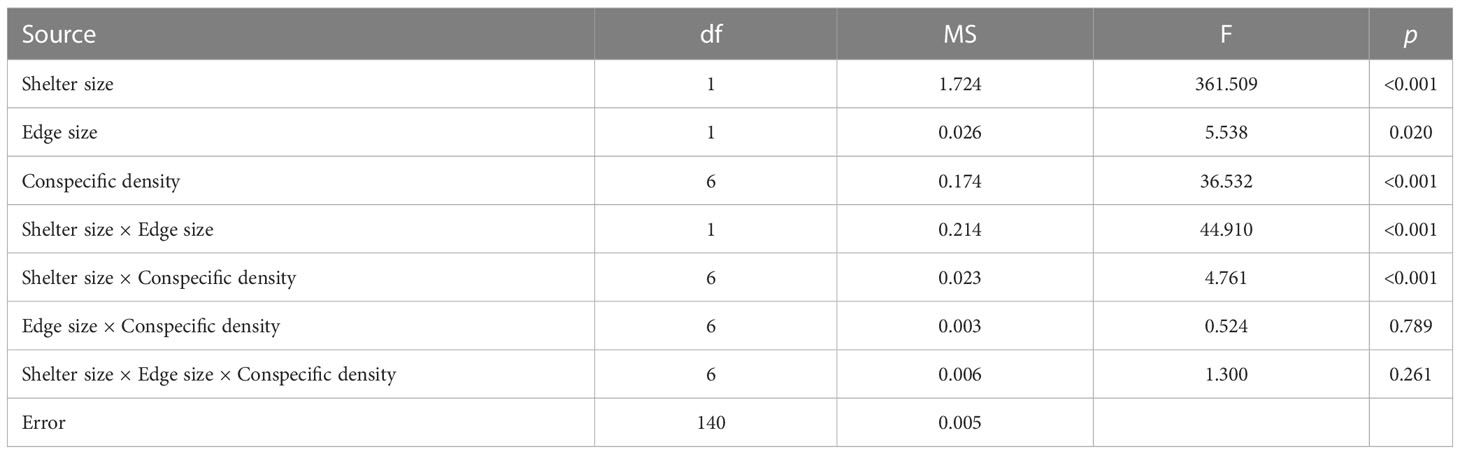

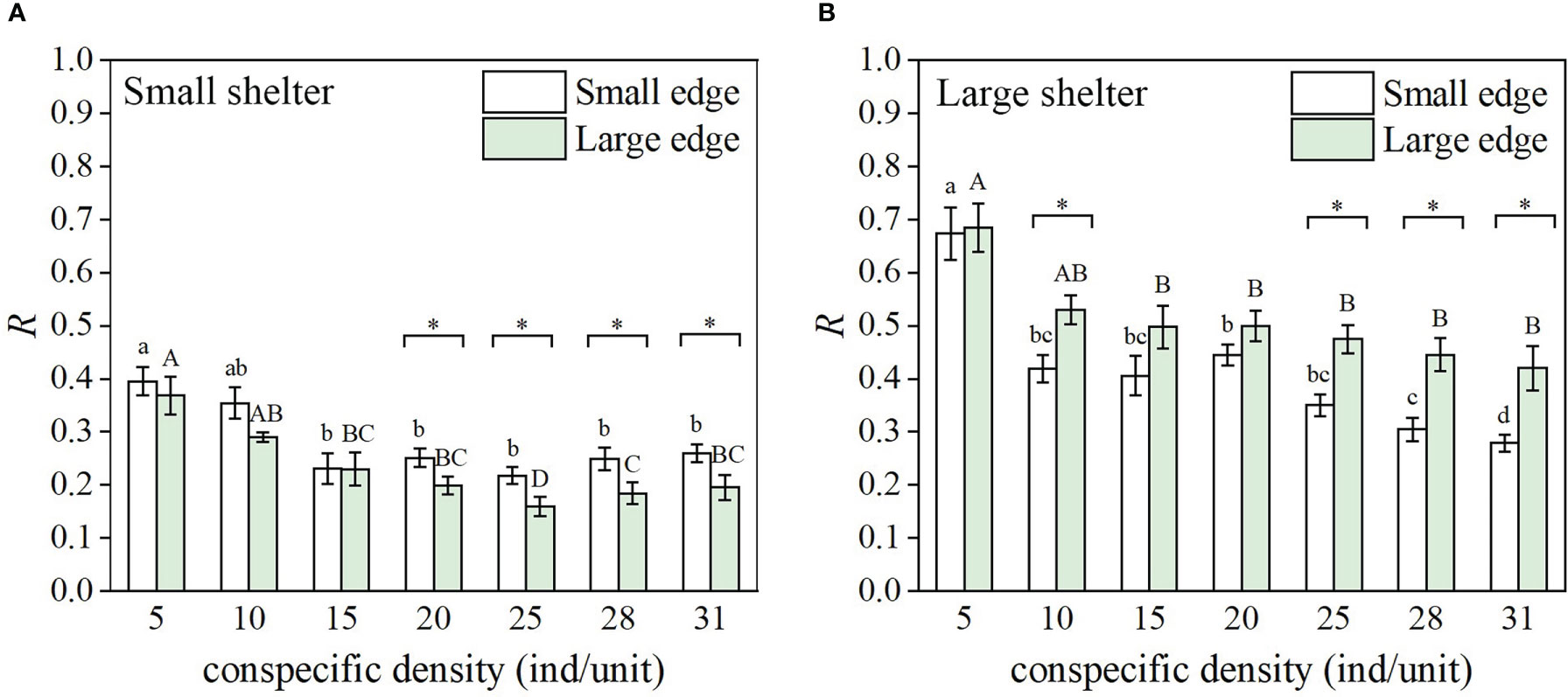

The size of the covered shelter significantly affected the aggregation rate (R) (Table 1). At each density, the reef unit with a large shelter significantly supported more aggregations compared to the small shelter (Figure 3, except for 10 ind/unit [p = 0.133], 28 ind/unit [p = 0.096], and 31 ind/unit [p = 0.410] in the small edge treatment). Significant shelter size × edge size interactions were recorded with aggregation rate (Table 1). In the small shelter treatment, the aggregation rate was significantly higher for the small edge (i.e., small shelter × small edge, medium ratio) compared to the large edge (i.e., small shelter × large edge, low ratio) at densities of 20, 25, 28, and 31 ind/unit (Figure 3A). In the large shelter treatment, the aggregation rate was significantly higher for the large edge (i.e., large shelter × large edge, medium ratio) compared to the small edge (i.e., large shelter × small edge, high ratio) at densities of 10, 25, 28 and 31 ind/unit (Figure 3B).

Table 1 Three-way ANOVA showing the effects of the shelter size, edge size, and conspecific density on the aggregation rate of fish.

Figure 3 Aggregation rate (R) (n = 6, mean ± SE) of fat greenling (Hexagrammos otakii) under the seven density treatments in the reef unit with (A) small shelter and (B) large shelter. Different lower-case letters represent significant differences among densities for the small edge (Tukey’s test, p< 0.05); different capital letters represent significant differences among densities for the large edge (Tukey’s test, p< 0.05); * indicates a significant difference between the small edge and large edge for same density and shelter (Tukey’s test, p< 0.05).

Conspecific density and shelter size × conspecific density interactions also significantly affected the aggregation rate (Table 1). In the small shelter treatment, the aggregation rate decreased with density when density was low (density ≤15 ind/unit), but showed a nonsignificant change at higher densities (Figure 3A). In the large shelter treatment, the aggregation rate had no significant difference at low densities (5 ind/unit< density ≤20 ind/unit), but began to decrease (significantly for small edge, Figure 3B) with increasing density.

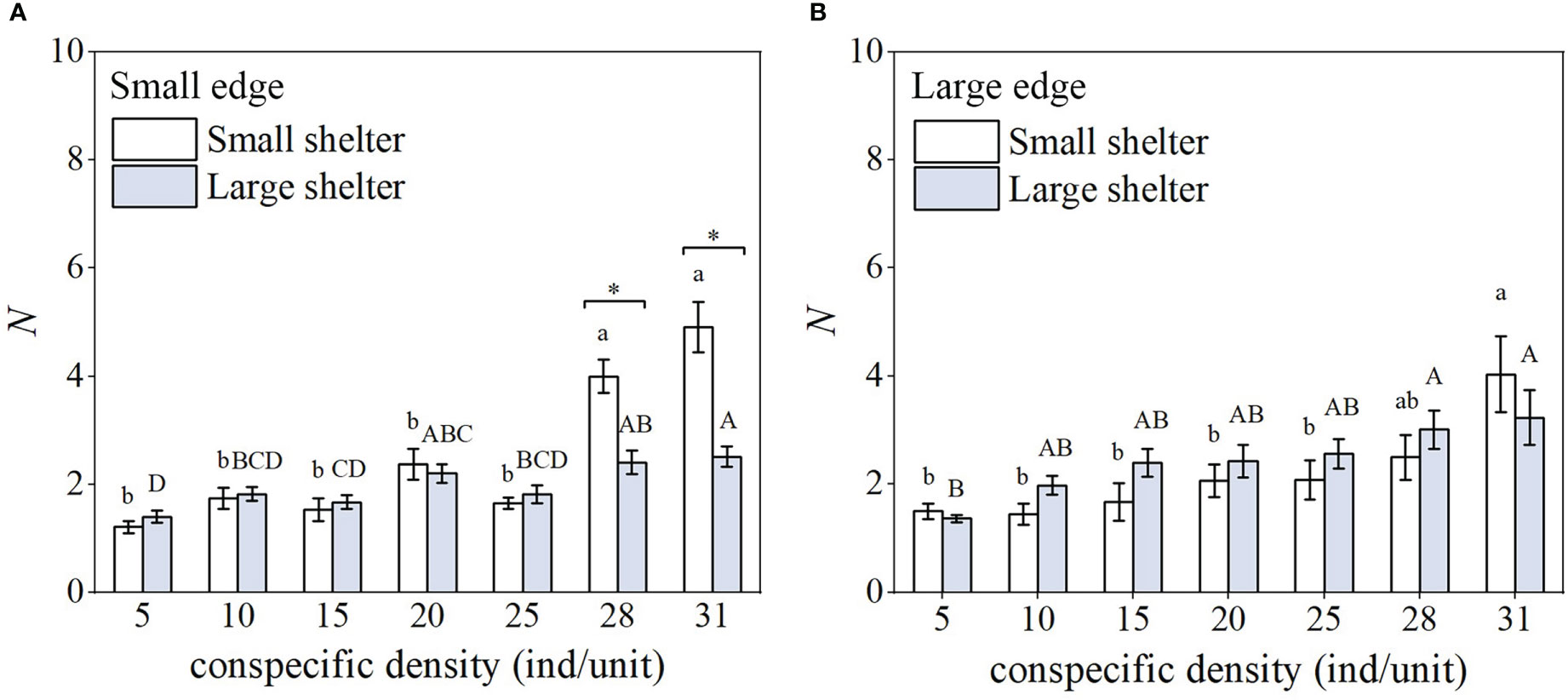

3.1.2 Number of occupants

In the small edge treatment, there was no significant difference in the number of occupants (N) for small shelter versus large shelter when density was ≤25 ind/unit, which was about two individuals (Figure 4A). As density increased, the number of occupants increased significantly (to 4–5 individuals) for the small shelter, and to a lesser extent for the large shelter. In contrast, for the large edge treatment, the number of occupants rose with density for both the small and large shelter; however, there was no significant difference between the small and large shelter at every density (Figure 4B).

Figure 4 Number of occupants (N) (n = 6, mean ± SE) under the seven density treatments in the reef unit with (A) small edge and (B) large edge. Different lower-case letters represent significant differences among densities for the small shelter (Tukey’s test, p< 0.05); different capital letters represent significant differences among densities for the large shelter (Tukey’s test, p< 0.05); * indicates a significant difference between small shelter and large shelter for same density and edge (Tukey’s test, p< 0.05).

3.2 Distribution under external disturbance

3.2.1 Protection rate

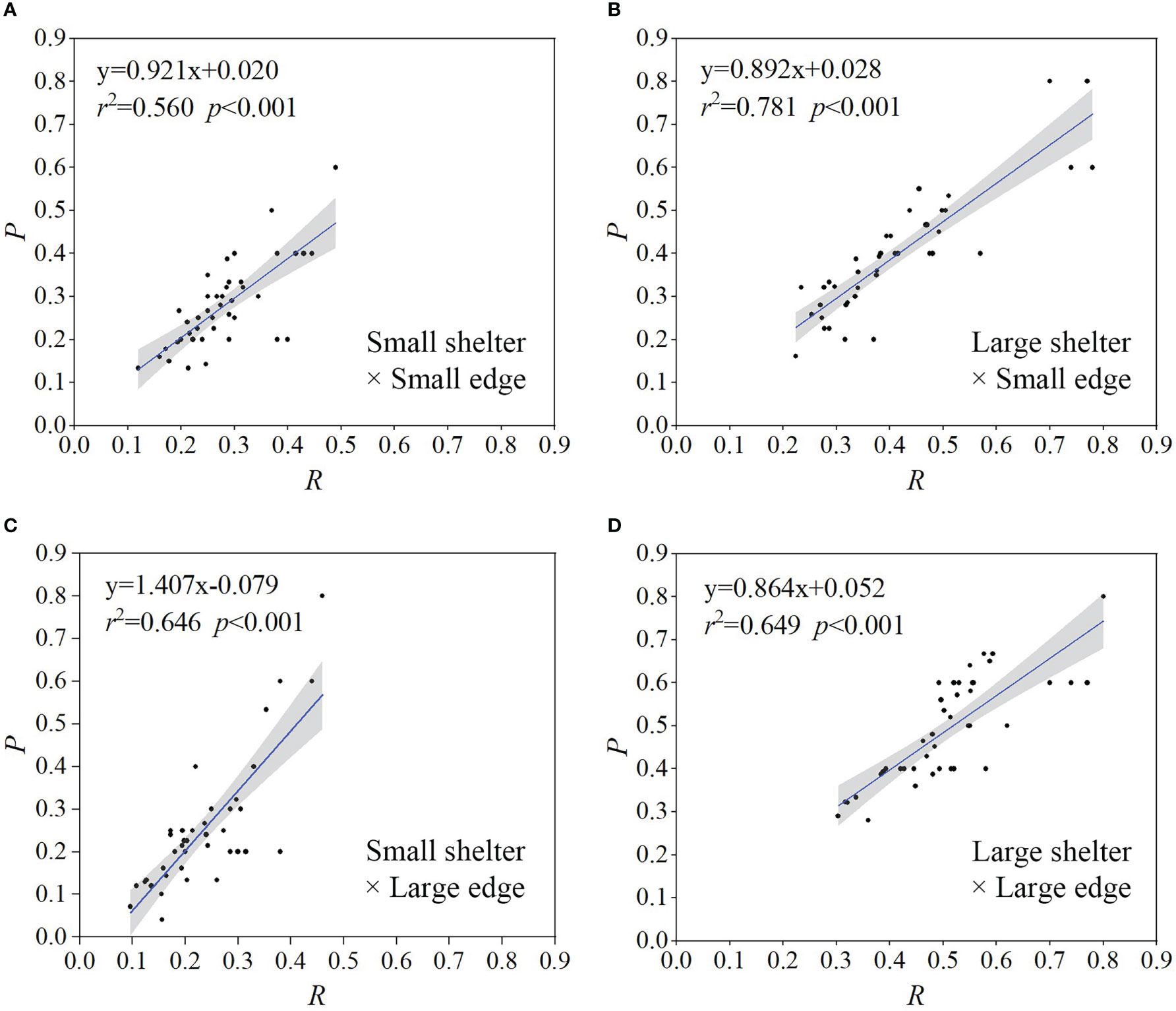

The protection rate (P) and aggregation rate (R) were positively correlated for all four reef unit structures, with the slope of regression equation > 1 for the small shelter × large edge treatment (Figure 5C) and < 1 for the other three structures (Figures 5A, B, D). These results showed that fish aggregating around a shelter (i.e., aggregation area in Figure 2B) entered the shelter more often after disturbance. Furthermore, fish distributed in the margin area of the reef unit that were also disturbed and moved closer to enclosing bricks (Figure S1), but obtained less effective protection compared to those that entered the shelter. Therefore, the sheltering effect was determined from the aggregation rate (R) in experiments. Specifically, when the aggregation rate was higher, the sheltering effect was better. Our results showed that when combining the aggregation rates under four reef unit structures, a medium shelter-edge ratio (= 0.3) had the best sheltering effect both for large and small shelters.

Figure 5 Relationship between the protection rate (P) and aggregation rate (R) for the four reef unit structures: (A) small shelter and small edge, (B) large shelter and small edge, (C) small shelter and large edge, (D) large shelter and large edge. Regression lines were generated using linear regression. Black dots represent raw data points. Shaded regions represent 95% confidence intervals.

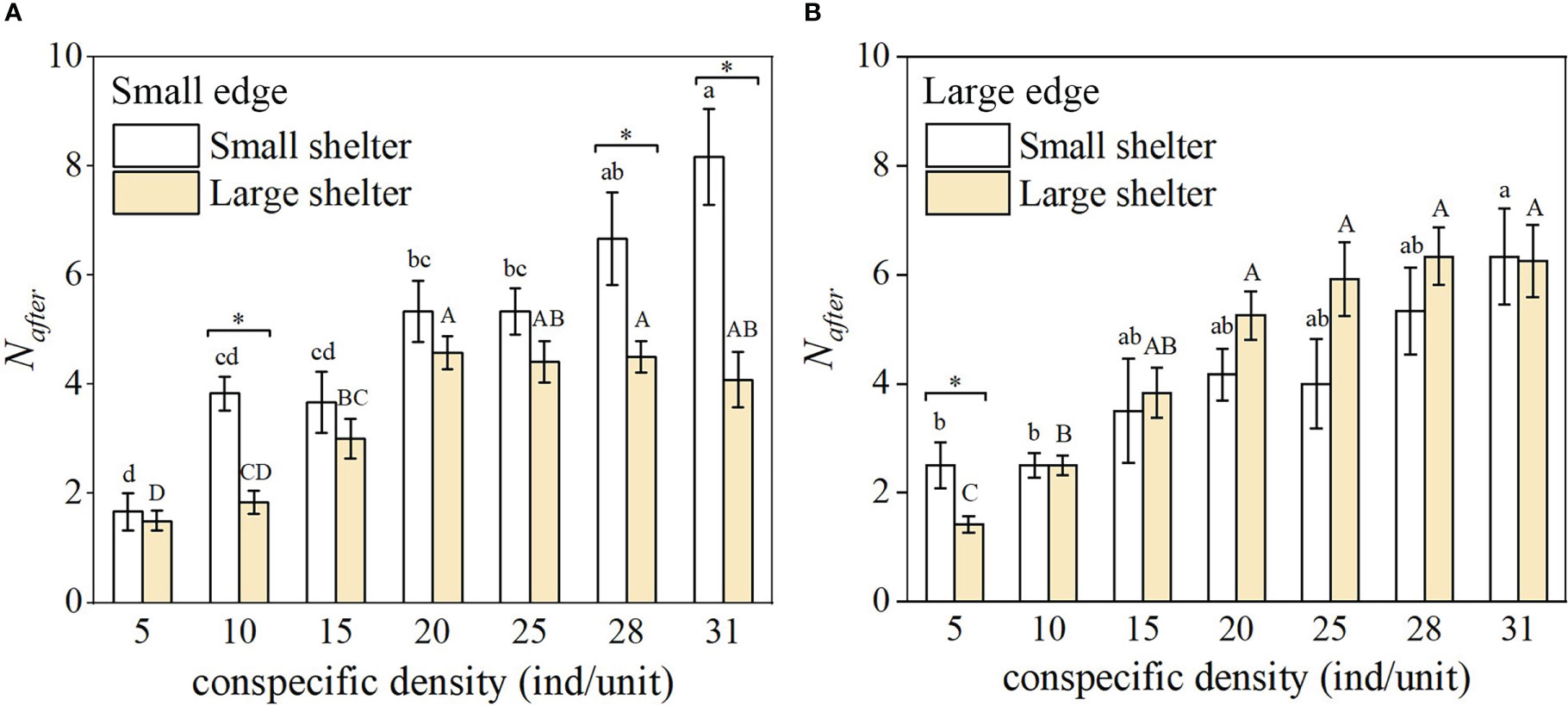

3.2.2 Number of fish in shelter after disturbance

In the small edge treatment, Nafter was higher for the small shelter compared to the large shelter (Figure 6A, significant at 10, 28, and 31 ind/unit). In the large edge treatment, Nafter was higher for the large shelter compared to the small shelter when density was 15, 20, 25, and 28, although these differences were not significant (Figure 6B). For each reef unit structure, Nafter was significantly higher than N when density was >10 ind/unit (Table S1, except for 15, 25, and 31 ind/unit in the small shelter × large edge treatment).

Figure 6 Number of fish in the shelter after disturbance (Nafter) (n = 6, mean ± SE) under the seven density treatments in the reef unit with (A) small edge and (B) large edge. Different lower-case letters represent significant differences among densities for the small shelter (Tukey’s test, p< 0.05); different capital letters represent significant differences among densities for the large shelter (Tukey’s test, p< 0.05); * indicates a significant difference between the small and large shelter for the same density and edge (Tukey’s test, p< 0.05).

4 Discussion

This study demonstrated the combined effect of covered and non-covered reef structures on fish distributions, and identified the optimal ratio for the size of these two types of structures under laboratory conditions. A reef with a large covered shelter had a better sheltering effect compared to that with a small shelter, but was limited by a small non-covered edge. In contrast, the sheltering effect of the reef with a small covered shelter was limited by a large non-covered edge compared to that with a small edge. Thus, the relative size of the shelter and edge of a reef must be moderate to enhance the sheltering effect, verifying our predictions.

4.1 Effects of reef structures on fish distribution

Our experiments showed that the aggregation rate (R) of juvenile fat greenling primarily depended on the size of the covered shelter. The reef unit with a large shelter supported more aggregations for various edge sizes. Juvenile fat greenling preferred shelter with an internal space (Liu et al., 2018), and their aggregations were density-dependent (Figure 3, aggregation rate decreased with conspecific density). This phenomenon was driven by intraspecific competition (Bostrom-Einarsson et al., 2013), which is common for various marine organisms, such as macrobenthos (Eggleston and Lipcius, 1992; Moksnes, 2004; Liu et al., 2014; Mirera and Moksnes, 2015). Density-dependent aggregations occurred at low densities in the treatment with a small shelter (Figure 3A, density ≤15 ind/unit) and at higher densities with a large shelter (Figure 3B, density >20 ind/unit). This phenomenon might be attributed to competition for shelter based on the ratio of the total number of individuals to the number of tiles (Berryman, 2004; Samhouri et al., 2009). Adding a tile for shelter also increased the carrying capacity, supporting more fish aggregations; consequently, density-dependent aggregations in the treatment with a larger shelter only became visible later in the gradient of fish density. Furthermore, the two sizes of edges had opposing effects on aggregations for the small and large shelter treatments, especially when fish density was higher (see Results 3.1.1). Increasing the size of the edge might attract more fish that are squeezed out of the shelter with competition, but could also interfere with the fish aggregation more strongly around the small shelter compared to the large shelter. This phenomenon might be due to the difference in attraction between the shelter and edge. Consequently, the ratio between the size of the shelter and edge represents a key factor regulating the strength of density-dependent aggregations.

Intraspecific competition changes the distribution patterns of animals by influencing individual behavior (Davey et al., 2009; Larranaga and Steingrimsson, 2015). Before being startled, two fish or so tended to be present in each central tile for the low density treatments (Figure 4A), supporting that fat greenling are solitary and defend their shelter against conspecifics (Zhang et al., 2021). This occupancy of the shelter might be attributed to interference competition (Holbrook and Schmitt, 2002; Kaspersson et al., 2013; Grabowska et al., 2016). While not analyzed statistically, we observed that individuals in the tile performed aggressive behaviors (e.g., threat and attack), forcing some individuals out of it. Furthermore, individuals outside of the tile also made several attempts to enter it. This phenomenon became more frequent as fish density increased.

4.2 Sheltering effects under external disturbance

Juvenile fat greenling exhibited shelter-seeking behavior under external disturbance, resulting in a positive relationship between the protection rate (P) and aggregation rate (R) (Figure 5). Of note, the slope of the regression equation for the small shelter × large edge treatment was greater than 1 compared to other treatments, showing that fish in the margin area preferentially entered the shelter after being startled. Furthermore, fish aggregated in the covered shelter (Table S1) and temporarily gave up their territorial monopoly under disturbance, due to antipredator tactics (Kintzing and Butler, 2014; Sinopoli et al., 2015). This type of aggregation behavior is similar to a safety–in–numbers effect of social species, which helps reduce predation risk to individuals (Sandin and Pacala, 2005; White and Warner, 2007).

In the marine ecosystem, fish exhibit startle responses to a variety of stimulus, including the approach of predators or non-living objects and anthropogenic noise (McCormick and Larson, 2007; Benevides et al., 2018; Harding et al., 2020; Mwaffo and Vernerey, 2022). Previous studies conducted laboratory mesocosm experiments to investigate how various parameters of fish (e.g., growth, condition, physiology, and behaviors) were impacted in response to stress caused by chemical alarm cues (Lonnstedt and McCormick, 2015; Faria et al., 2019), sight of predator (Meager et al., 2006; Goldenberg et al., 2014), and/or mechanical disturbance (Ramasamy et al., 2017; Hess et al., 2019) such as knocking the wall of the tank and waving a fishing net inside the water (Gesto and Jokumsen, 2022). Our experiments used mechanical disturbance, in the form of an acute startling stimulus that mimicked the sudden strike of a predator. Although different to a real predator, the disturbance represents a perceived threat (Ramasamy et al., 2017), which elicits a shelter seeking response in fish, especially juveniles. Juveniles represent a particularly vulnerable life stage of reef fish, with survival being strongly influenced by the sheltering effect of ARs over a relatively short period of time (Ross et al., 2007; Fobert et al., 2020).

4.3 Designs of AR structures for sheltering

Caley and StJohn (1996) considered that the effects of the two types of shelter (permanent and transient shelter) on fish were unavoidably confounded. Here, we assessed two types of structures in one reef (covered and non-covered structure), rather than different types of reefs. This classification of the structure is based on their differences in sheltering capacity. We proposed that the covered shelter should have a certain ratio with the non-covered edge to enhance the sheltering effect. Based on our experimental results, we proposed a ratio value (0.3) as optimal for juvenile fat greenling; however, a moderate shelter-edge ratio likely exists for the structural design of ARs, when considering the combined effects of interspecific interactions and environmental stresses. Moreover, although the reef with large shelter and edge had a better sheltering effect compared to that with small shelter and edge under the same shelter-edge ratio, it is necessary to weigh the ecological benefits versus construction costs. Intermediate reef sizes are often suggested to produce the best ratio of biomass to cost (Jan et al., 2003; Pondella et al., 2022). The trade-offs between costs and design criteria are also important considerations to enhance the sheltering effect of ARs.

Our study serves as a primary model for estimating the sheltering effects of reefs, before more levels of the shelter-edge ratio are considered. More complex designs (e.g., combinations of vertical reliefs and/or spacing) should be explored in future studies to identify optimal AR structures (Davis and Smith, 2017; Paxton et al., 2022; Taormina et al., 2022). In addition, the indicator of shelter-edge ratio might be species-dependent, due to the specific behavioral characteristics of fat greenling. However, this ratio would likely be viable for other reef fish and benthic organisms that are attracted to reefs that might not necessarily provide effective shelters. In conclusion, more research on the relationship between other species and reef structures should be explored to validate the novel findings of the current study.

5 Conclusion

Our study highlights that the size of the covered shelter and the size of the non-covered edge are key attributes of reef structures that strongly affect the distribution of juvenile fat greenling at the laboratory scale. The relative size of the shelter and edge regulates the strength of density-dependent aggregations driven by intraspecific competition. A moderate relative size of shelter and edge is beneficial in protecting juvenile fat greenling from external disturbance. The shelter-edge ratio could be used as an indicator of shelter availability, and could be incorporated to optimize the design of AR structures.

Data availability statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics statement

The animal study was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Beijing Normal University.

Author contributions

YZ, TS, GD, DY, and WY contributed to design of the study. YZ, GD, DY, and QS performed the experiments. YZ performed the statistical analysis and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. TS, XW and HL reviewed drafts of the manuscript. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China [Grant No. 2018YFC1406400]; the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. U1806217]; and the Beijing Advanced Innovation Program for Land Surface Science.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2023.1130626/full#supplementary-material

References

Becker A., Smith J. A., Taylor M. D., McLeod J., Lowry M. B. (2019). Distribution of pelagic and epi-benthic fish around a multi-module artificial reef-field: Close module spacing supports a connected assemblage. Fisheries Res. 209, 75–85. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2018.09.020

Becker A., Taylor M. D., Folpp H., Lowry M. B. (2018). Managing the development of artificial reef systems: The need for quantitative goals. Fish Fisheries 19 (4), 740–752. doi: 10.1111/faf.12288

Benevides L. J., Pinto T. K., Nunes J., Sampaio C. L. S. (2018). Fish escape behavior as a monitoring tool in the largest Brazilian multiple-use marine protected area. Ocean Coast. Manage. 152, 154–162. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.11.029

Berryman A. A. (2004). Limiting factors and population regulation. Oikos 105 (3), 667–670. doi: 10.1111/j.0030-1299.2004.13381.x

Blount C., Komyakova V., Barnes L., Smith M. L., Zhang D., Reeds K., et al. (2021). Using ecological evidence to refine approaches to deploying offshore artificial reefs for recreational fisheries. Bull. Mar. Sci. 97 (4), 665–698. doi: 10.5343/bms.2020.0059

Bostrom-Einarsson L., Bonin M. C., Munday P. L., Jones G. P. (2013). Strong intraspecific competition and habitat selectivity influence abundance of a coral-dwelling damselfish. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 448, 85–92. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.06.017

Caley M. J., StJohn J. (1996). Refuge availability structures assemblages of tropical reef fishes. J. Anim. Ecol. 65 (4), 414–428. doi: 10.2307/5777

Davey A. J. H., Doncaster C. P., Jones O. D. (2009). Distinguishing between interference and exploitation competition for shelter in a mobile fish population. Environ. Modeling Assess. 14 (5), 555–562. doi: 10.1007/s10666-008-9171-5

Davis T. R., Smith S. D. A. (2017). Proximity effects of natural and artificial reef walls on fish assemblages. Regional Stud. Mar. Sci. 9, 17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.rsma.2016.10.007

Eggleston D. B., Lipcius R. N. (1992). Shelter selection by spiny lobster under variable predation risk, social conditions, and shelter size. Ecology 73 (3), 992–1011. doi: 10.2307/1940175

Faria M., Bedrossiantz J., Prats E., Rovira Garcia X., Gomez-Canela C., Pina B., et al. (2019). Deciphering the mode of action of pollutants impairing the fish larvae escape response with the vibrational startle response assay. Sci. Total Environ. 672, 121–128. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.03.469

Fernandez-Betelu O., Graham I. M., Thompson P. M. (2022). Reef effect of offshore structures on the occurrence and foraging activity of harbour porpoises. Front. Mar. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.980388

Fobert E. K., Reeves S. E., Swearer S. E. (2020). Ontogenetic shifts in social aggregation and habitat use in a temperate reef fish. Ecosphere 11 (12). doi: 10.1002/ecs2.3300

Ford J. R., Shima J. S., Swearer S. E. (2016). Interactive effects of shelter and conspecific density shape mortality, growth, and condition in juvenile reef fish. Ecology 97 (6), 1373–1380. doi: 10.1002/ecy.1436

Ford J. R., Swearer S. E. (2013). Two’s company, three’s a crowd: Food and shelter limitation outweigh the benefits of group living in a shoaling fish. Ecology 94 (5), 1069–1077. doi: 10.1890/12-1891.1

Fu D., Chen Y., Chen Y., Luan S. (2014). PIV experiment of artificial monomer reefs on the flowing field. J. Dalian Ocean Univ. 29 (1), 82–85. doi: 10.3969/J.ISSN.2095-1388.2014.01.017

Gatts P. V., Franco M. A. L., Santos L. N., Rocha D. F., Zalmon I. R. (2014). Influence of the artificial reef size configuration on transient ichthyofauna - southeastern Brazil. Ocean Coast. Manage. 98, 111–119. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2014.06.022

Gesto M., Jokumsen A. (2022). Effects of simple shelters on growth performance and welfare of rainbow trout juveniles. Aquaculture 551. doi: 10.1016/j.aquaculture.2022.737930

Goldenberg S. U., Borcherding J., Heynen M. (2014). Balancing the response to predation-the effects of shoal size, predation risk and habituation on behaviour of juvenile perch. Behav. Ecol. Sociobiol 68 (6), 989–998. doi: 10.1007/s00265-014-1711-1

Grabowska J., Kakareko T., Blonska D., Przybylski M., Kobak J., Jermacz L., et al. (2016). Interspecific competition for a shelter between non-native racer goby and native European bullhead under experimental conditions - effects of season, fish size and light conditions. Limnologica 56, 30–38. doi: 10.1016/j.limno.2015.11.004

Granneman J. E., Steele M. A. (2015). Effects of reef attributes on fish assemblage similarity between artificial and natural reefs. Ices J. Mar. Sci. 72 (8), 2385–2397. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsv094

Gregor C. A., Anderson T. W. (2016). Relative importance of habitat attributes to predation risk in a temperate reef fish. Environ. Biol. Fishes 99 (6-7), 539–556. doi: 10.1007/s10641-016-0496-7

Hackradt C. W., Felix-Hackradt F. C., Garcia-Charton J. A. (2011). Influence of habitat structure on fish assemblage of an artificial reef in southern Brazil. Mar. Environ. Res. 72 (5), 235–247. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2011.09.006

Harding H. R., Gordon T. A. C., Wong K., McCormick M. I., Simpson S. D., Radford A. N. (2020). Condition-dependent responses of fish to motorboats. Biol. Lett. 16 (11). doi: 10.1098/rsbl.2020.0401

Hess S., Allan B. J. M., Hoey A. S., Jarrold M. D., Wenger A. S., Rummer J. L. (2019). Enhanced fast-start performance and anti-predator behaviour in a coral reef fish in response to suspended sediment exposure. Coral Reefs 38 (1), 103–108. doi: 10.1007/s00338-018-01757-6

Holbrook S. J., Schmitt R. J. (2002). Competition for shelter space causes density-dependent predation mortality in damselfishes. Ecology 83 (10), 2855–2868. doi: 10.2307/3072021

Hylkema A., Debrot A. O., Osinga R., Bron P. S., Heesink D. B., Izioka A. K., et al. (2020). Fish assemblages of three common artificial reef designs during early colonization. Ecol. Eng. 157. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2020.105994

Islam G. M. N., Noh K. M., Sidique S. F., Noh A. F. M., Ali A. (2014). Economic impacts of artificial eeefs on small-scale fishers in peninsular Malaysia. Hum. Ecol. 42 (6), 989–998. doi: 10.1007/s10745-014-9692-2

Jan R. Q., Liu Y. H., Chen C. Y., Wang M. C., Song G. S., Lin H. C., et al. (2003). Effects of pile size of artificial reefs on the standing stocks of fishes. Fisheries Res. 63 (3), 327–337. doi: 10.1016/s0165-7836(03)00081-x

Johnson D. W. (2006). Predation, habitat complexity, and variation in density-dependent mortality of temperate reef fishes. Ecology 87 (5), 1179–1188. doi: 10.1890/0012-9658(2006)87[1179:phcavi]2.0.co;2

Kaspersson R., Sundstrom F., Bohlin T., Johnsson J. I. (2013). Modes of competition: Adding and removing brown trout in the wild to understand the mechanisms of density-dependence. PloS One 8 (5). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0062517

Kerry J. T., Bellwood D. R. (2016). Competition for shelter in a high-diversity system: Structure use by large reef fishes. Coral Reefs 35 (1), 245–252. doi: 10.1007/s00338-015-1362-3

Kim D., Woo J., Yoon H.-S., Na W.-B. (2016). Efficiency, tranquillity and stability indices to evaluate performance in the artificial reef wake region. Ocean Eng. 122, 253–261. doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2016.06.030

Kimura M. R., Munehara H. (2010). The disruption of habitat isolation among three hexagrammos species by artificial habitat alterations that create mosaic-habitat. Ecol. Res. 25 (1), 41–50. doi: 10.1007/s11284-009-0624-3

Kintzing M. D., Butler M. J. (2014). The influence of shelter, conspecifics, and threat of predation on the behavior of the long-spined sea urchin (Diadema antillarum). J. Shellfish Res. 33 (3), 781–785. doi: 10.2983/035.033.0312

Komyakova V., Chamberlain D., Jones G. P., Swearer S. E. (2019). Assessing the performance of artificial reefs as substitute habitat for temperate reef fishes: Implications for reef design and placement. Sci. Total Environ. 668, 139–152. doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2019.02.357

Kwak S. N., Baeck G. W., Klumpp D. W. (2005). Comparative feeding ecology of two sympatric greenling species, Hexagrammos otakii and Hexagrammos agrammus in eelgrass zostera marina beds. Environ. Biol. Fishes 74 (2), 129–140. doi: 10.1007/s10641-005-7429-1

Langhamer O., Wilhelmsson D. (2009). Colonisation of fish and crabs of wave energy foundations and the effects of manufactured holes - a field experiment. Mar. Environ. Res. 68 (4), 151–157. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2009.06.003

Larranaga N., Steingrimsson S. O. (2015). Shelter availability alters diel activity and space use in a stream fish. Behav. Ecol. 26 (2), 578–586. doi: 10.1093/beheco/aru234

Lemoine H. R., Paxton A. B., Anisfeld S. C., Rosemond R. C., Peterson C. H. (2019). Selecting the optimal artificial reefs to achieve fish habitat enhancement goals. Biol. Conserv. 238. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2019.108200

Li J., Gong P., Chang Q., Meng Z., Guan C., Li J. (2020). Research progress on behavioral ecology of reef fish. Prog. Fishery Sci. 41 (6), 192–199. doi: 10.19663/j.issn2095-9869.20200224001

Li J. J., Li J., Gong P. H., Guan C. T. (2021). Effects of the artificial reef and flow field environment on the habitat selection behavior of Sebastes schlegelii juveniles. Appl. Anim. Behav. Sci. 245. doi: 10.1016/j.applanim.2021.105492

Lima J. S., Zalmon I. R., Love M. (2019). Overview and trends of ecological and socioeconomic research on artificial reefs. Mar. Environ. Res. 145, 81–96. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2019.01.010

Lindberg W. J., Frazer T. K., Portier K. M., Vose F., Loftin J., Murie D. J., et al. (2006). Density-dependent habitat selection and performance by a large mobile reef fish. Ecol. Appl. 16 (2), 731–746. doi: 10.1890/1051-0761(2006)016[0731:dhsapb]2.0.co;2

Liu Q. X., Herman P. M., Mooij W. M., Huisman J., Scheffer M., Olff H., et al. (2014). Pattern formation at multiple spatial scales drives the resilience of mussel bed ecosystems. Nat. Commun. 5, 5234. doi: 10.1038/ncomms6234

Liu H., Lu H., Zhang P., Li W., Zhang X. (2018). Attraction effect of artificial reef model and macroalgae on juvenile Sebastes schlegelii and Hexagrammos otakii. J. Fisheries China 42 (1), 48–59. doi: 10.11964/jfc.20161210634

Liu X. X., Wang J., Zhang Y. L., Yu H. M., Xu B. D., Zhang C. L., et al. (2019). Comparison between two GAMs in quantifying the spatial distribution of Hexagrammos otakii in haizhou bay, China. Fisheries Res. 218, 209–217. doi: 10.1016/j.fishres.2019.05.019

Lonnstedt O. M., McCormick M. I. (2015). Damsel in distress: captured damselfish prey emit chemical cues that attract secondary predators and improve escape chances. Proc. R. Soc. B-Biological Sci. 282 (1818). doi: 10.1098/rspb.2015.2038

Ma Q. F., Ding J., Xi Y. B., Song J., Liang S. X., Zhang R. J. (2022). An evaluation method for determining the optimal structure of artificial reefs based on their flow field effects. Front. Mar. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.962821

McCormick M. I., Larson J. K. (2007). Field verification of the use of chemical alarm cues in a coral reef fish. Coral Reefs 26 (3), 571–576. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0221-2

Meager J. J., Domenici P., Shingles A., Utne-Palm A. C. (2006). Escape responses in juvenile Atlantic cod Gadus morhua l.: The effects of turbidity and predator speed. J. Exp. Biol. 209 (20), 4174–4184. doi: 10.1242/jeb.02489

Menard A., Turgeon K., Roche D. G., Binning S. A., Kramer D. L. (2012). Shelters and their use by fishes on fringing coral reefs. PloS One 7 (6). doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0038450

Mirera D. O., Moksnes P. O. (2015). Comparative performance of wild juvenile mud crab (Scylla serrata) in different culture systems in East Africa: effect of shelter, crab size and stocking density. Aquaculture Int. 23 (1), 155–173. doi: 10.1007/s10499-014-9805-3

Moksnes P. O. (2004). Interference competition for space in nursery habitats: density-dependent effects on growth and dispersal in juvenile shore crabs Carcinus maenas. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 281, 181–191. doi: 10.3354/meps281181

Mwaffo V., Vernerey F. (2022). Analysis of group of fish response to startle reaction. J. Nonlinear Sci. 32 (6). doi: 10.1007/s00332-022-09855-0

Nie Z. Y., Zhu L. X., Xie W. D., Zhang J. T., Wang J. H., Jiang Z. Y., et al. (2022). Research on the influence of cut-opening factors on flow field effect of artificial reef. Ocean Eng. 249. doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2022.110890

Paxton A. B., Shertzer K. W., Bacheler N. M., Kellison G. T., Riley K. L., Taylor J. C. (2020). Meta-analysis reveals artificial reefs can be effective tools for fish community enhancement but are not one-size-fits-all. Front. Mar. Sci. 7. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.00282

Paxton A. B., Steward D. N., Harrison Z. H., Taylor J. C. (2022). Fitting ecological principles of artificial reefs into the ocean planning puzzle. Ecosphere 13 (2). doi: 10.1002/ecs2.3924

Pondella D. J., Claisse J. T., Williams C. M. (2022). Theory, practice, and design criteria for utilizing artificial reefs to increase production of marine fishes. Front. Mar. Sci. 9. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.983253

Ramasamy R. A., Allan B. J. M., McCormick M. I., Chivers D. P., Mitchell M. D., Ferrari M. C. O. (2017). Juvenile coral reef fish alter escape responses when exposed to changes in background and acute risk levels. Anim. Behav. 134, 15–22. doi: 10.1016/j.anbehav.2017.09.026

Ramm L. A. W., Florisson J. H., Watts S. L., Becker A., Tweedley J. R. (2021). Artificial reefs in the anthropocene: a review of geographical and historical trends in their design, purpose, and monitoring. Bull. Mar. Sci. 97 (4), 699–728. doi: 10.5343/bms.2020.0046

Ross P. M., Thrush S. F., Montgomery J. C., Walker J. W., Parsons D. M. (2007). Habitat complexity and predation risk determine juvenile snapper (Pagrus auratus) and goatfish (Upeneichthys lineatus) behaviour and distribution. Mar. Freshw. Res. 58 (12), 1144–1151. doi: 10.1071/mf07017

Samhouri J. F., Vance R. R., Forrester G. E., Steele M. A. (2009). Musical chairs mortality functions: density-dependent deaths caused by competition for unguarded refuges. Oecologia 160 (2), 257–265. doi: 10.1007/s00442-009-1307-z

Sandin S. A., Pacala S. W. (2005). Fish aggregation results in inversely density-dependent predation on continuous coral reefs. Ecology 86 (6), 1520–1530. doi: 10.1890/03-0654

Sinopoli M., Cattano C., Andaloro F., Sara G., Butler C. M., Gristina M. (2015). Influence of fish aggregating devices (FADs) on anti-predator behaviour within experimental mesocosms. Mar. Environ. Res. 112, 152–159. doi: 10.1016/j.marenvres.2015.10.008

Smith J. A., Cornwell W. K., Lowry M. B., Suthers I. M. (2017). Modelling the distribution of fish around an artificial reef. Mar. Freshw. Res. 68 (10), 1955–1964. doi: 10.1071/mf16019

Smith J. A., Lowry M. B., Suthers I. M. (2015). Fish attraction to artificial reefs not always harmful: a simulation study. Ecol. Evol. 5 (20), 4590–4602. doi: 10.1002/ece3.1730

Sui H., Xue Y., Ren Y., Zou Y., Yu L. (2017). Studies on the ecological groups of fish communities in haizhou bay, China. Periodical Ocean Univ. China 47 (12), 59–71. doi: 10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.20160282

Sun Y., Zan X., Xu B., Ren Y. (2014). Growth, mortality and optimum catchable size of Hexagrammos otakii in haizhou bay and its adjacent waters. Periodical Ocean Univ. China 44 (9), 46–52. doi: 10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.2014.09.006

Taormina B., Claquin P., Vivier B., Navon M., Pezy J. P., Raoux A., et al. (2022). A review of methods and indicators used to evaluate the ecological modifications generated by artificial structures on marine ecosystems. J. Environ. Manage. 310. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2022.114646

Teichert M. A. K., Foldvik A., Einum S., Finstad A. G., Forseth T., Ugedal O. (2017). Interactions between local population density and limited habitat resources determine movements of juvenile Atlantic salmon. Can. J. Fisheries Aquat. Sci. 74 (12), 2153–2160. doi: 10.1139/cjfas-2016-0047

Wang G., Wan R., Wang X. X., Zhao F. F., Lan X. Z., Cheng H., et al. (2018). Study on the influence of cut-opening ratio, cut-opening shape, and cut-opening number on the flow field of a cubic artificial reef. Ocean Eng. 162, 341–352. doi: 10.1016/j.oceaneng.2018.05.007

White J. W., Samhouri J. F., Stier A. C., Wormald C. L., Hamilton S. L., Sandin S. A. (2010). Synthesizing mechanisms of density dependence in reef fishes: behavior, habitat configuration, and observational scale. Ecology 91 (7), 1949–1961. doi: 10.1890/09-0298.1

White J. W., Warner R. R. (2007). Safety in numbers and the spatial scaling of density-dependent mortality in a coral reef fish. Ecology 88 (12), 3044–3054. doi: 10.1890/06-1949.1

Wu Z. X., Tweedley J. R., Loneragan N. R., Zhang X. M. (2019). Artificial reefs can mimic natural habitats for fish and macroinvertebrates in temperate coastal waters of the yellow Sea. Ecol. Eng. 139. doi: 10.1016/j.ecoleng.2019.08.009

Yu D., Yang Y., Li Y. (2019). Research on hydrodynamic characteristics and stability of artificial reefs with different opening ratios. Periodical Ocean Univ. China 49 (4), 128–136. doi: 10.16441/j.cnki.hdxb.20160322

Zhang Z. H., Fu Y. Q., Zhang Z., Zhang X. M., Chen S. C. (2021). A comparative study on two territorial fishes: The influence of physical enrichment on aggressive behavior. Animals 11 (7). doi: 10.3390/ani11071868

Keywords: artificial reef, structural attribute, sheltering effect, distribution, shelter availability, reef fish

Citation: Zhang Y, Sun T, Ding G, Yu D, Yang W, Sun Q, Wang X and Lin H (2023) Moderate relative size of covered and non-covered structures of artificial reef enhances the sheltering effect on reef fish. Front. Mar. Sci. 10:1130626. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2023.1130626

Received: 23 December 2022; Accepted: 22 March 2023;

Published: 30 March 2023.

Edited by:

James Scott Maki, Marquette University, United StatesReviewed by:

Joshua Patterson, University of Florida, United StatesWon-Bae Na, Pukyong National University, Republic of Korea

Copyright © 2023 Zhang, Sun, Ding, Yu, Yang, Sun, Wang and Lin. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Tao Sun, c3VudGFvQGJudS5lZHUuY24=

Yue Zhang

Yue Zhang Tao Sun

Tao Sun Gang Ding2

Gang Ding2 Daode Yu

Daode Yu Wei Yang

Wei Yang Xiaoling Wang

Xiaoling Wang