- School of International Law, East China University of Political Science and Law, Shanghai, China

With the development of marine protected areas (MPAs) on the high seas in the international community and an international agreement protecting biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction, how to reasonably restrict the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs has become a controversial issue in theory and in practice. This article will use doctrinal research method. It will discuss existing provisions regarding restricting the freedom of fishing on the high seas including the high seas MPAs. These provisions have been codified in international treaties, international resolutions, and international soft law. In addition, since regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs) also take part in fishery management in the high seas MPAs, this article will refer to measures of relevant RFMOs to discuss how restriction is going in terms of the freedom of fish in the high seas MPAs. This article finds that the fishing-restriction measures stipulated in international documents represented by the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea are too general. In addition, some treaties do not address certain issues of restricting fishing methods by non-contracting parties. Therefore, these treaties are limited. The fishing practices of the four high seas MPAs that have been established by the international community reveals the establishment of several reasonable fishing restrictions. However, their shortcomings are evident. From the perspective of international law, it is important to improve the principle of reasonably restricting the freedom of fishing in MPAs on the high seas based on practice and positive law while proceeding steadily. Moreover, restriction measures cannot be too broad or narrow. Specifically, we should continue to develop mechanisms such as exceptions, ways of restricting fishing, advocacy provisions for non- contracting parties and measures to strengthen international information exchange.

1 Introduction

The international community decided to establish a legally binding document based on the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) regarding on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (ABNJ). Since then, the protection of the ABNJ including the high seas has become a significant topic for international negotiation. In addition, marine protected areas (MPAs) appear to become one of the potential instruments for protecting the environment and biological diversity in the ABNJ. However, there is no unified definition of MPAs in the international community at present. The draft text of an agreement under the UNCLOS on preserving biological diversity of ABNJ (BBNJ Agreement) tends to define a “marine protected area” as an area whose purpose is to conserve or sustainably use specific biological resources (United Nations General Assembly, 2019). However, the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) proposed to exclude sustainable use as one of the purposes of the MPAs during negotiation (United Nations General Assembly, 2022a). This is because the addition of sustainable use may contradict with the definitions of protected areas made by the IUCN, Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and the OSPAR convention (United Nations General Assembly, 2022b). For discussion, this article prefers to define high seas MPAs as geographical spaces formed by international treaties or arrangements relevant to conserve fishery resources on the high seas (Day et al., 2019).

The freedom of fishing has not only developed into customary international law but has also been codified in the UNCLOS, which is known as the “Constitution of the Sea”. However, it should be noted that the principle of the freedom of fishing on the high seas is not absolute. Since the signing of the 1958 Convention on Fishing and Conservation of the High Seas (1958 Convention on Fishing), the international community has begun to restrict the freedom of fishing on the high seas to a certain extent. This has been reflected further in international treaties such as the UNCLOS and practices taken by the regional fisheries management organizations (RFMOs).

However, at present, how to reasonably restrict the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs appears controversial. First, the freedom of the high seas doctrine appears not to specifically define rights and obligations for states regarding fisheries resources on the high seas (Henriksen et al., 2006). Some radical criticisms contend that management measures taken by fishery managing authorities and MPAs fail to “adequately” restrict fishing efforts (Grafton et al., 2010). Second, the effectiveness of the RFMOs may be questioned. Every part of the high seas is managed by at least one RFMO (Cullis-Suzuki and Pauly, 2010). However, these RFMOs may only manage fishery of specific species (Molenaar, 2007). These management measures may not be comprehensive enough to meet the requirements set by the high seas MPAs. Third, there have been numerous disagreements on restricting freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs during international negotiation. At the meeting of the Preparatory Committee for the BBNJ Agreement, participating states had debated the relationship among the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs, management measures and approaches to establishing the high seas MPAs, identification of areas and effectiveness of management measures on non-parties (Chair of Preparatory Committee established by General Assembly resolution 69/292, 2017). However, the BBNJ Working Groups co-chairs’ 2014 report did emphasize that some unsustainable fishing practices such as overfishing and IUU fishing greatly endangered marine biodiversity in the relevant areas, particularly the high seas (United Nations General Assembly, 2014).

Therefore, it is significant to analyze reasonable restrictions that can be put on fishing measures in the high seas MPAs from the perspective of international law. First, it is beneficial for regulating states’ fishing practices in the high seas MPAs to better protect the environment of the high seas and fishery resources in them. Second, it is beneficial to achieve a balance between protection and sustainable use of fishery resources in the high seas MPAs, thereby promoting a holistic development of the high seas MPAs. Sustainable development refers to development that satisfies current demands without impairing the capability of future generations to satisfy their own needs (Sands et al., 2018). Reasonable restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas will encourage the sustainable use of fishery resources. Third, it is beneficial for the development of international laws of the sea. The issue of reasonable restrictions on fishing in the high seas MPAs involves not only international law of the sea, international environmental law, and international treaty law, but also many issues such as environmental science and technology, fishing industry, and domestic fishery policies.

This article will aim to analyze restrictions on the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs. In terms of the methods, this article will use doctrinal research method. It will discuss existing provisions regarding restricting the freedom of fishing on the high seas including the high seas MPAs. These provisions have been codified in international treaties, international resolutions, and international soft law. In addition, since RFMOs also take part in fishery management in the high seas MPAs, this article will also refer to measures of relevant RFMOs to discuss how restriction is going in terms of freedom of fish in the high seas MPAs (Freestone, 2018). Last but not last, this article will make suggestions for the high seas MPAs to improve restrictions on freedom of fishing on the high seas. We hope that these suggestions may not only contribute to the development of the current high seas MPAs but also provide references regarding restricting freedom of fishing on the high seas when establishing other high seas MPAs in the future.

2 Analysis of main international law provisions on reasonable restriction in the high seas MPAs fishing measures

Since the high seas MPAs cover the ABNJ especially the high seas, treaty provisions regarding restricting freedom of fishing on the high seas are applicable to them. Therefore, it appears necessary to analyze relevant provisions.

2.1 A review of the main provisions of international law on measures to reasonably restrict fishing in the high seas MPAs

Main provisions refer to provisions applicable to all high seas MPAs mentioned in this article. They are significantly related to the international law of the sea.

2.1.1 The 1958 Convention on Fishing

This Convention made three restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas. Those restrictions are concentrated mainly in Article 1 of the Convention: a state and its nationals engaging in fishing on the high seas should be based on the treaty obligations, the interests and rights of coastal States and conservation provisions stemming from this Convention. This can be seen as the centralisation and clarification of the obligation of “reasonable regard” in Article 2 of the Geneva Convention on the High Seas (The Convention on the High Seas, 1958, art. 2). According to Article 3 of the Convention, a contracting State is required to take conservation measures to control its nationals if they capture fish or other marine living resources on the high seas without participation of any other contracting states’ nationals.

2.1.2 The UNCLOS

Articles 87 (1) (e), 87 (2) and 116 of Part VII of the UNCLOS clearly stipulate the principle of the freedom of fishing on the high seas. According to the aforementioned articles, high seas are open to all countries, whether coastal or land-locked. Furthermore, all states have the right of fishing on the high seas by their nationals. The UNCLOS impose restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas to the States through both general and special perspectives. Three factors represent the general restrictions on the freedom of the high seas doctrine. First, other States’ interests should be taken into account when a State exercises its freedom of the high seas (UNCLOS, 1982, art. 87). Due regard to rights of activities in the relevant area should be taken when a State exercises those freedoms (UNCLOS, 1982, art. 87). Third, the high seas must not be used for any violent means. (UNCLOS, 1982, art. 88).

The special restrictions are concentrated mainly in Articles 63 to 67 and Articles 116 to 120 of the UNCLOS. Articles 63 to 67 prescribe that States shall conserve fish stock “occurring within the exclusive economic zones of two or more coastal States or both within the exclusive economic zone and in an area beyond and adjacent to it” (UNCLOS, 1982, art. 63), “Highly migratory species” (UNCLOS, 1982, art. 64), “Marine mammals” (UNCLOS, 1982, art. 65), “Anadromous stocks” (UNCLOS, 1982, art. 66) and “Catadromous species” (UNCLOS, 1982, art. 67). Combining other international treaties, Article 66 of the UNCLOS may be able to support aggressive non-flag enforcement taken by several RFMOs (Rayfuse, 2005). According to Article 116 of the UNCLOS, though all States may enjoy the rights of fishing on the high seas by their nationals, such rights should be subject to their obligations stemming from Article 63, paragraph 2, and Articles 64 to 67 of the UNCLOS, obligations prescribed in section 2 of the UNCLOS and obligations stemming from other treaties. It associates the rights and duties of high seas fishing under the UNCLOS to other international legal documents regulating high seas fishery. If a State is a member of more than one regional fishery treaties or arrangements, it shall undertake all of the obligations relating to high seas fishery in these legal regimes concurrently (Schwabach and Cockfield, 2009). Article 117 regulates that conserving the living resources of the high seas shall be regarded as the purpose of the legal obligation prescribed in Articles 116 to 120 of the UNCLOS (Spijkers and Jevglevskaja, 2013). Article 118 requires States to cooperate with one another when conserving and managing living resources in the areas of the high seas. In order to take necessary measures regarding this kind of conservation, negotiation should be completed among States whose nationals catch or use living resources in the same area. Establishing sub-regional or regional fisheries organisations appears a proper approach. States may take part in conservation measures by joining RFMOs based on their own consideration (Roucou, 2017). Article 119 set a basic principle for States to take measures to determine allowable catches for each species of fish and each sea area so that the number of fished species is maintained or restored to a level capable of producing the highest sustainable yield (Freestone, 1999). Therefore, when determining fishing, countries should be based on the most reliable scientific evidence, within the constraints of various environmental and economic factors, including the special requirements of developing countries and taking into account the connection among fishing methods and stocks so the numbers of fish species associated and dependent on fish species are maintained or restored above levels at which their reproduction is not seriously threatened (Fu, 2005). Article 120 extends the restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas to the category of marine mammals.

2.1.3 The UN fish stocks agreement

After six rounds of negotiations, on 4 August 1995, a legally binding international convention was finally adopted unanimously. This agreement restricts fishing measures mainly in Articles 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20 and 21.

The aforementioned articles require state parties to consider the impact of fishing methods on the environment and to take measures to eliminate overfishing and overcapacity. In addition, the agreement also requires States Parties to cooperate on a sub-regional or regional basis to protect the fishes that are included in the Agreement (IUCN, 2006). Article 21 of the agreement specifies some serious violations of fishing activities, including fishing in closed areas, during closed periods, or in the absence of or after quotas have been established by the relevant fisheries-management organizations, utilization of prohibited fishing gears and exploiting a stock which is protected from being caught (UN Fish Stocks Agreement, 1995, art. 21).

Although this agreement is only an executive document, its influence cannot be underestimated. It is a concentrated expression of the international community’s strict management of high seas fishery resources in recent years, and it is a relatively complete global international fishery agreement. Its most significant aspect is that it provides an operational mechanism for interstate cooperation between coastal States and countries that fish on the high seas in fulfilling their obligations to conserve and manage straddling fish stocks and highly migratory fish stocks (Zhang, 2007).

2.1.4 The 1995 code of conduct for responsible fisheries

This is an international guiding document or “soft law” for fisheries management which was adopted by the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) in October 1995 (Grafton et al., 2010). When states conduct research and other activities, the Code of Conduct requires them to assume their responsibilities by setting principles and international standards of fishing efforts (Spijkers and Jevglevskaja, 2013). With regard to specific provisions relating to restrictions on the freedom of fishing, the Code of Conduct suggests that develop and apply selective, environmentally sound fishing gears and fishing methods in order to maintain biodiversity and aquatic ecosystems (Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, 1995 Para 6.6). At the same time, due publicity to conservation and management measures shall be ensured by States and fisheries-management organisations and arrangements (Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, 1995, p. Para 7.1.10). With regard to restrictions on fishing methods and fishing capacity, the Code of Conduct requires that states should investigate the status of all existing fishing gears and fishing methods and take steps to discard gears and fishing methods which are not in line with responsible fisheries and replace them with more acceptable ones (Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, 1995 Para 7.6.4). If there is excess fishing capacity, it should be necessary to establish mechanisms of fishing capacity reduction to a level consistent with the sustainable utilization of fishery resources (Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, 1995 Para 7.6.3).

2.2 Analysis

First, the aforementioned international legal documents have enforced restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas including the high seas MPAs, indicating that restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas are turning into practice rather than mere theory. The freedom of fishing on the high seas should be limited to a certain extent. This was recognized by the international community to some extent based on the consensus that some detrimental fishing practices such as overfishing became increasingly serious (Higginson, 1993). These fishing practices may influence the biodiversity in the high seas (Helm et al., 2021). In addition, international disputes relevant to the freedom of fishing on the high seas occurred. For example, to protect its Grand Banks from overfishing, Canada promulgated the Fisheries Zone Act in 1976, establishing an exclusive fishing zone and implementing stricter fishery management rules (Dunlap, 1994). Two corners of the Grand Banks, which account for 10% of its total area, are outside the 200-mile exclusive fishing zone of Canada (Dunlap, 1994). Because those two corners are not under the jurisdiction of Canada, they have long been overfished by foreign fishing vessels. This has seriously endangered straddling fish species in Canadian exclusive fishing zone and those in the high seas (Teece, 1997). Later, Canada amended the Coastal Fisheries Protection Act on 12 May 1994, authorising itself to seize and search foreign fishing vessels that fish near the Grand Banks. Moreover, the amendment declared Canada’s jurisdiction over relating fishing vessels on the high seas. The Coastal Fisheries Protection Act Amendment of 12 May 1994 violated the widely accepted practice of international law and international usage, which ensures that vessels are free from interference by other countries except their flag states on the high seas. Therefore, the Council of Europe, the United States and other countries strongly protested and opposed the Amendment through diplomatic channels. It seemed that lack of provisions restricting fishing on the high seas may lead to more international disputes.

On the basis of both ecological and political concerns, the international community had to pay increasing attention to restricting the freedom of fishing on the high seas. Prescribing relevant provisions appears a significant approach. These provisions include various obligations. For example, in terms of general obligation, the 1958 Convention on Fishing requires the contracting parties to abide by the provisions on the conservation of the living resources of the high seas when exercising the freedom of fishing based on respecting treaty obligations and respecting the interests and rights of coastal States.

Regarding the obligation of protecting special fish stock, Article 63 of the UNCLOS stipulates that if fish stocks straddle among EEZs and the high seas, international cooperation to the establishment of RFMOs shall be carried out among the coastal States and other States in order to manage relevant fish stocks in the high seas (Roucou, 2017). Article 64 of the UNCLOS codifies that States shall cooperate when their nationals fish highly migratory fish stocks. This cooperation could be done through bilateral or multilateral arrangement or an international organization. It may not be proper for a State to prohibit relevant fishing activities unless there is an adequate exchange of views and information among relevant states (Burke, 1984; Islam, 1991).

Concerning standard of conservation, Article 119 of the UNCLOS requires States to take measures aimed at maintaining the number of species harvested within or return to a level capable of producing the highest sustainable yield, taking into account fishing practices, the interconnections among stocks and any generally recommended international minimum standards. Concerning kinds of prohibited fishing practices, the UN Fish Stocks Agreement prescribes “fishing in a closed area” (UN Fish Stocks Agreement, 1995, art. 21), “fishing during a closed season” (UN Fish Stocks Agreement, 1995, art. 21), and directed fishing for a stock that is protected by a fishing ban or a moratorium (UN Fish Stocks Agreement, 1995, art. 21) and requires that coastal States and States that fish on the high seas to use “selective, environmentally safe and cost-effective fishing gear and techniques” (UN Fish Stocks Agreement, 1995, art. 5 (f)). The Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries requires investigation of existing fishing practices and replacement of fishing gears and methods which are not environmentally friendly (Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries, 1995 Para 7.6.4).

In addition, it should be noted that international treaties such as the 1958 Convention on Fishing, the UNCLOS and the UN Fish Stocks Agreement are legally binding. If a State party fails to reasonably manage fishing on the high seas in accordance with these treaties, it might be liable for having violated international law. Besides liability prescribed in other regional fishery treaties or arrangements, this State may have to repair for injury according to customary international law. Such reparation may include restitution, compensation, satisfaction or interest by referring to Article 34 to 38 of the Draft articles on Responsibility of States for internationally wrongful acts. Although this is only a draft regarding customary international law, it presents a legal consensus by the international community on the state obligation to some extent (Crawford, 2002). Therefore, the liability codified in this draft may be applicable in this context. However, this may just be a theoretical approach because there is no practice of customary international law in this context.

Second, restrictive measures prescribed in the aforementioned international legal documents seem general and not practical (Tyler, 2006). For example, none of these documents makes specific restrictions on the kinds of fishing gears. For another example, these documents do not stipulate specific fish stocks to be protected. In addition, the “due regard” stipulated in Article 87 of the UNCLOS appears ambiguous. First, it is not clear to what extent “due regard” should be achieved in the context of restricting the freedom of fishing on the high seas. Should it mean “not seriously affect other States” freedom of the high seas” or “must balance interests of all other States”? Second, regarding the scope of such restrictions, “due regard” should include “the interests of other States in their exercise of the freedom of the high seas”. It is not clear how a state should apply “due regard” to other States” interests when its freedom of fishing conflicts with other States” high seas freedoms.

Third, some of these documents directly impose obligations on non-contracting parties, whereas others do not. This seems insufficient. First, Article 8 of the UN Fish Stocks Agreement restricts the freedom of fishing on the high seas by non-contracting states. Its Article 8 (4) indicates that if a state is neither a member of a sub-regional or regional fisheries management organization or a participant in an arrangement nor willing to apply conservation and management measures established by a relevant organization or arrangement, it will not be eligible for catching relevant fishing resources. Therefore, States which depend on high seas fisheries significantly should join relevant organization or arrangements in order to catch relevant fish stocks. In comparison, the 1958 Convention on Fishing and the UNCLOS do not restrict fishing on the high seas by non-contracting states. If treaties cannot restrict fishing on the high seas by non-contracting states, states might be reluctant to accede to those treaties based on their own economic or political concerns. Given this, a number of States may become “free riders” by not joining the Fish Stocks Agreement or any RFMOs while keeping fishing on the high seas (Henriksen et al., 2006). These free riders may enjoy the benefits of conservation by the other States without taking any responsibility for conserving fish stocks. However, this is not conducive to encouraging participation in such treaties and does not contribute to the conservation of high seas fishery resources.

3 Practical analysis of fishing restrictions in the high seas MPAs

The high seas MPAs each established fishing restrictions. These restrictions are established based on various international instruments or by different organizations. Nevertheless, their main objective appears the same. That is to achieve the conservation or protection of fishery resources. Given that these restrictions appear various in content, it seems necessary to analyze them to explore how the high seas MPAs make effort to restrict the freedom of fishing on the high seas.

3.1 The practice of reasonable restriction on the freedom of fishing in the four high seas MPAs

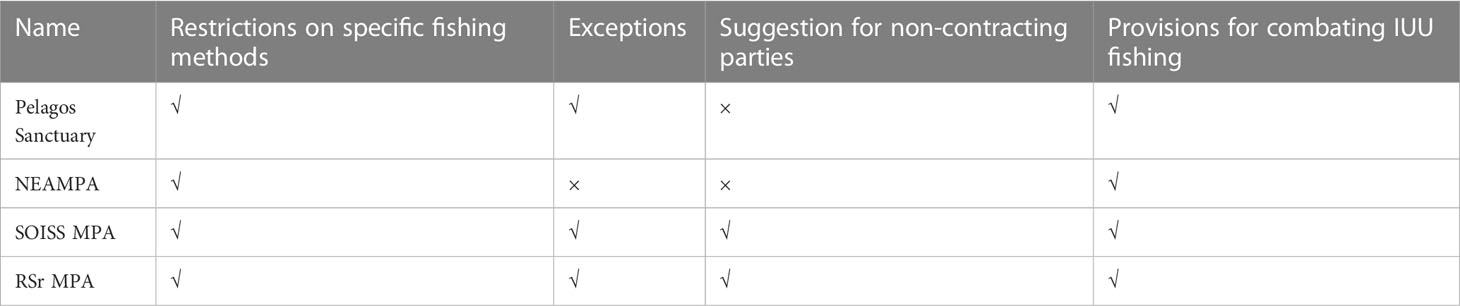

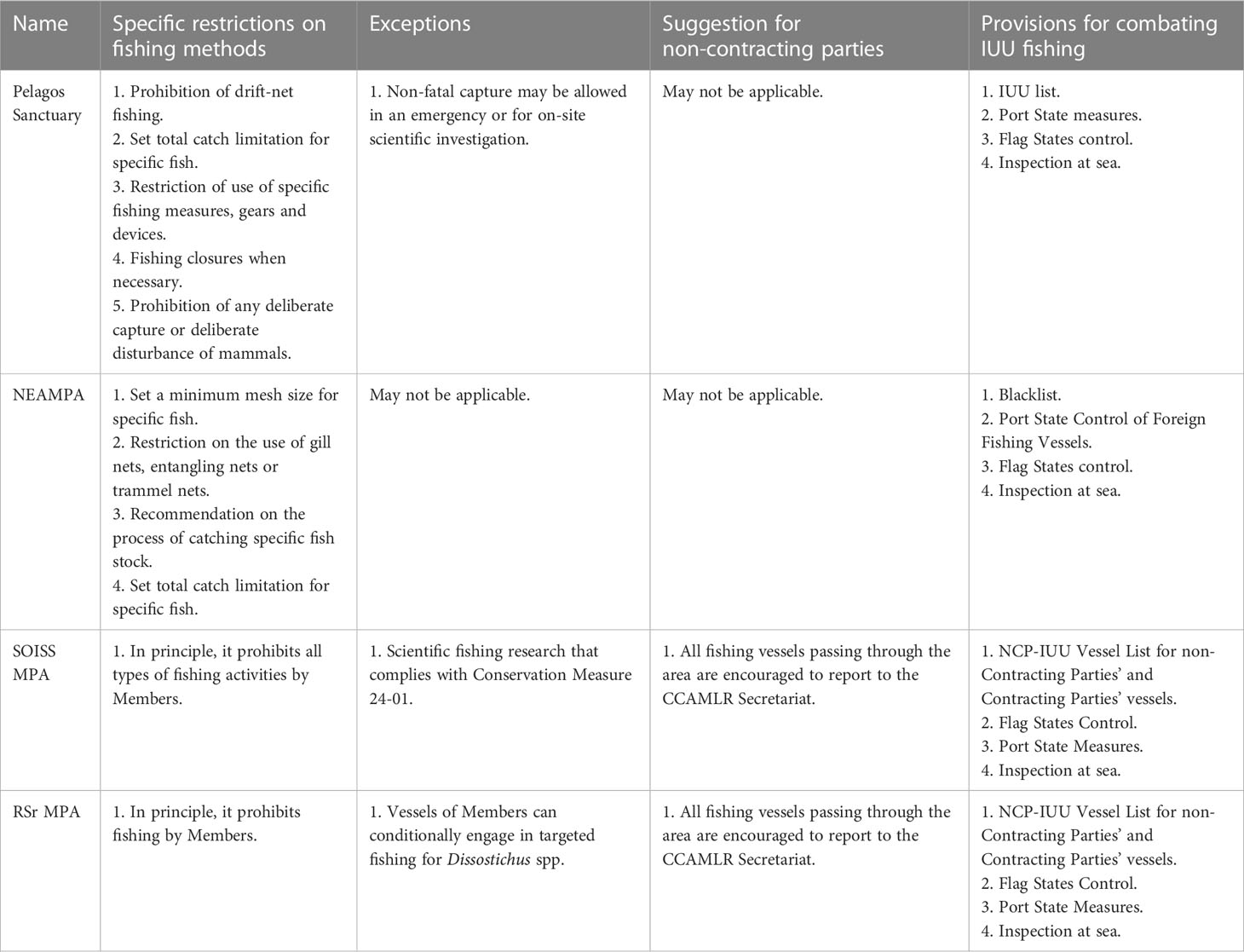

Currently, four high seas MPAs have been established, namely, the Pelagos Sanctuary, the NEAMPA, the SOISS MPA (Druel, 2011) and the RSr MPA. The Pelagos Sanctuary is an area of about 90,000 square kilometres (Pelagos Sanctuary, 2022b), covering waters of three countries and part of the high seas, of which more than 50% is outside the jurisdictional waters of neighbouring countries. By 1 October 2018, the NEAMPA included seven MPAs collectively designated in the ABNJ (OSPAR Commission, 2018). The SOISS MPA is in the concave area of the western Antarctic Peninsula, covering about 100,000 square kilometres of water (Scott, 2012). The RSr MPA covers 2.09 million square kilometres (CCAMLR, 2016d). Other basic information is attached in the Table 1 below.

The priorities of conservation measures of the four high seas MPAs are different. For example, the Pelagos Sanctuary aims to protect local marine mammals (Pelagos Sanctuary, 2022a). The SOISS MPA aims to protect important feeding areas for albatross, petrel and penguin. The main conservation measures for the RSr MPA are for fishery resources in the area. Conservation measures of the NEAMPA are basically for the water bodies of the high seas in protected areas and the ecological environment of the international seabed area. The details of the fishing restrictions in the four high seas MPAs are as follows (see Tables 2, 3 for details).

First, four high seas MPAs restrict contracting parties’ freedom of fishing from the perspective of specific fishing methods. To begin with, in terms of the specific means of restricting fishing measures, the Pelagos Sanctuary prohibit “drift-net fishing” and any deliberate capture or deliberate disturbance of mammals. In addition, measures established by the General Fisheries Commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) include total catch limitation for specific fish (GFCM, 2023a; GFCM, 2023b), restriction on the use of specific fishing measures (GFCM, 2006; GFCM, 2019), gears and devices and fishing closures when necessary (GFCM, 2023b). There are four kinds of restrictions on the freedom of fishing in the NEAMPA: the mesh size of fishing nets is restricted; the use of gill nets, entanglements or trawls is prohibited; the process of catching specific types of fish is limited and, finally, fishing quotas are set for certain types of fish (Grafton et al., 2010). Both the SOISS MPA and the RSr MPA prohibit all types of fishing by Members. It should also be pointed out that once a State joins in as a Member of these MPAs, it has to obey these restrictions even if it is a “new entrant” (Vicuna, 1992).

However, there are exceptions to these restriction measures. In terms of the Pelagos Sanctuary, according to Article 7 (a) of the Agreement Concerning the Creation in the Mediterranean of a Sanctuary for Marine Mammals, non-lethal capture is permitted in case of emergencies or scientific research in the field in accordance with the aforementioned agreement (Accord Relatif A La Creation En Mediterranee D’un Sanctuaire Pour Les Mammiferes Marins, 1999, art. 7 (a)). Although the SOISS MPA in principle prohibits all types of fishing activities by Members, there are exceptions that scientific fishing research activities which have obtained approval from the Commission or other purposes on advice from the Scientific Committee and compliant with Conservation Measure 24-01 are permitted (CCAMLR, 2009 Para 2). As far as the RSr MPA is concerned, an exception is codified under paragraphs 8, 9 and 21 of Conservation Measure 91-05 (2016) (CCAMLR, 2016c Para 7). The conditions of this exception include limiting the fishing zone and setting the release rate and total catch limit in accordance with the specific objectives set out in paragraph 3 (CCAMLR, 2016c Para 8,9 and 21).

Second, two high seas MPAs establish suggestions for non-contracting parties. The SOISS MPA and the RSr MPA encourage that before entering the defined area, all transiting fishing vessels are recommended to inform the CCAMLR Secretariat with details of their flag state, size, IMO number and intended course. (CCAMLR, 2009 Para 5, CCAMLR, 2016c Para 26). As a soft-law clause, this is likely to contribute to the control of vessels’ activities in these two high seas MPAs.

Third, all of the high seas MPAs establish measures for combating IUU fishing. According to Articles 117 to 119 of the UNCLOS and Article 19 of the Fish Stock Agreement, flag States of the vessels are obliged to regulate the activities including fishing on the high seas (Lodge et al., 2007). This jurisdiction is also applicable in the high seas MPAs. Therefore, all of the high seas MPAs may be able to use flag States control to combat IUU fishing. Besides, all of the MPAs establish port state control to combat IUU fishing. In addition, all of the high seas MPAs have established inspection at sea according to RFMOs’ conservation measures and Articles 21 and 22 of the Fish Stock Agreement. Last but not least, there are IUU vessels lists in all of the MPAs.

3.2 Analysis opinion

First, management measures regarding reasonably restricting the freedom of fishing in the four high seas MPAs appear very specific. Some regulations even specify fishing methods or fishing gears for specific species, which makes these regulations practical.

For example, in 2015, the NEAFC adopted a recommendation on shark fishing. According to this recommendation, the Committee requests that Contracting Parties are responsible for taking necessary measures which ensure that the entire catches of sharks are landed. This means retention of all parts of the shark excepting a few of the organs to the first landing point (NEAFC, 2015). These procedures included the following requirements. First, all sharks were to be landed. Second, Contracting Parties shall prevent shark fins from being removed at sea, being kept on board, transhipment and landing. Third, regarding fisheries which are not directly aimed at sharks, Contracting Parties are responsible for releasing alive sharks that are caught incidentally and are not used for making a living. Fourth, Contracting Parties are required to conduct research to identify ways to improve the selectivity of fishing gears in order to diminish by-catches of sharks if it is possible. Compared with the general provisions of the UNCLOS, the aforementioned regulation is obviously more practical. In addition, fishing is a technical skill that includes a number of technical processes. A general rule without specific documents and stipulations will not effectively regulate fishing. Therefore, such measures to reasonably restrict fishing in the four high seas MPAs are further associated with realistic observations of fishing in those areas and appear more reasonable than general rules.

Second, legal instruments restricting fishing in the high seas MPAs have made advocacy provisions for non-Contracting Parties. These advocacy provisions seem to be able to nudge non-Contracting Parties to protect the high seas without violating the principles of international law. Taking the SOISS MPA and the RSr MPA as examples, in order to monitor traffic in the protected areas, before entering the defined area, all transiting fishing vessels are recommended to inform the CCAMLR Secretariat with details of their flag state, size, IMO number and intended course (CCAMLR, 2009 Para 2). As a soft-law clause, it is likely to contribute to the control or monitor of vessels’ activities in the MPAs.

Third, four high seas MPAs’ fishing practices are mainly managed by relevant RFMOs. These four MPAs rely on the measures set by the relevant RFMOs. For example, the Pelagos Sanctuary was established for protecting marine mammals. Given this, traditional fishery management may not be particularly concerned by this MPA unless fishing practices such as using driftnet endanger mammals living in this MPA. Resolution GFCM/37/2013/1 confirms that the GFCM should establish of Fisheries Restricted Areas for the conservation of fisheries resources, particularly for areas on the high seas or areas located totally or partially in Specially Protected Areas of Mediterranean Importance (SPAMI) (GFCM, 2013). The Pelagos Sanctuary is one of the SPAMIs (The Regional Activity Centre for Specially Protected Areas, 2020) so the GFCM is capable of management of fishery practices in the Pelagos Sanctuary. In terms of the NEAMPA, according to article 4 of the OSPAR Convention Annex V, fisheries management may not be adopted by the OSPAR convention. Management of fishing practices is mainly carried out by North East Atlantic Fisheries Commission (NEAFC) since OSPAR establishes objectives of conservation of the high seas without prescription of specific measures regarding fishing (Reeve et al., 2012). The SOISS MPA and the RSr MPA are established based on the CCAMLR conservation measures. According to Article I, IX and XX of the Convention for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CAMLR Convention), the CCAMLR is responsible for the conservation of living resources including fish stock in the Convention area. Therefore, the CCAMLR becomes the most important organization in the Convention area including the SOISS MPA and the RSr MPA and should be regarded as an RFMO.

Fourth, all of the high seas MPAs put emphasis on combating IUU fishing. IUU fishing appears the most significant issue which influences the conservation of fishery resources in the high seas (OECD, 2004). Therefore, it appears necessary to deal with this problem.

The IUU vessels lists play an important role in combating IUU fishing in the high seas MPAs. The NEAFC inspects fishing vessels to confirm whether the fishing activities of those vessels comply with management measures. Those that violate the management measures will be regarded as participating in IUU fishing and will be added to NEAFC’s lists (NEAFC, 2005). Based on these practices, it seems that RFMOs tend not to consider whether IUU vessels’ states should fulfil any treaty obligation or not. Instead, they adopt a series of measures such as “blacklists”, “observation lists” and “fishing restrictions”, which directly regulate IUU fishing (Wei, 2017). IUU fishing also attracts the CCAMLR’s attention because it has regularly been put forward by the CCAMLR since 1997 (Grafton et al., 2010). The CCAMLR Commission shall identify non-Contracting Parties’ and Contracting Parties’ vessels which may undermine the effectiveness of CCAMLR conservation measures by engaging in IUU fishing within the Convention Area and establish a list of such vessels (NCP-IUU Vessel List) at its annual conference (CCAMLR, 2016b Para 2, CCAMLR, 2016a Para 1).

Inspection at sea appears another useful measure of combating IUU fishing. Articles 15 to 19 of the NEAFC Scheme of Control and Enforcement set the procedures of inspection at sea for contracting parties. Article 38 of this scheme requires NEAFC inspectors to request permission to board non-Contracting Parties’ vessels. Not only the flag states of the vessels but also other Members Parties of the NEAFC may be able to inspect vessels at sea (NEAFC, 2022, art. 15). This may be useful when flag States may not be able to control IUU fishing. For another example, Resolution 25/XXV of the CCAMRL requires all Contracting Parties, individually and collectively, “to the extent possible in accordance with their applicable laws and regulations … to grant permission for boarding and inspection by designated CCAMLR inspectors of their flag vessels suspected of, or found to be, fishing in an IUU manner in the Convention Area” [CCAMLR, 2006 Para 1 (iv)].

In addition, port state measures are applied to make it more costly to sell fish caught by IUU fishing. These measures include request notification before entry into the port, landing or transhipment at port and inspection at port. It is worth mentioning that port state measures may be extended to states which are not the members of the RFMOs. For example, CCAMLR requests that when IUU fishing vessels seek utilization of the ports of non-Contracting Parties, Contracting Parties shall cooperate with non-Contracting Party Port States to prompt their regulating actions in the light of Conservation Measure 10-07 (CCAMLR, 2006 Para 2). Resolution 32/XXIX encourages the collaboration of non-Contracting Parties to take part in the implementation of the CCAMLR’s Catch Documentation Scheme for Dissostichus spp at their ports in order to verify the origin of Dissostichus spp which will be imported and/or re-exported from its territory and ensure that these fishes were harvested in approaches that complied with CCAMLR’s conservation measures as stipulated for Contracting Parties in Conservation Measure 10-05 (Resolution 32/XXIX, Prevention, deterrence and elimination of IUU fishing in the Convention Area, 2010 Para 5).

Besides, traditional flag states control may also be enhanced by the RFMOs. This may be done by reaffirming the obligation of flag states based on RFMOs’ documents. For example, in 2021 the GFCM adopted a resolution to encourage Contracting Parties of the GFCM Agreement to keep self-assessments of flag state performance and submit reports to the Compliance Committee so as to “prevent, deter and eliminate IUU fishing” (GFCM, 2021).

Fifth, several exceptions are established in the Pelagos Sanctuary, the SOISS MPA and the RSr MPA, thus achieving a balance between normality and flexibility. These high seas MPAs pay attention to balancing scientific research and fishery management. This may be because they realize that traditional fishery regimes might not put enough emphasis on scientific information including various factors for the local ecosystem when managing fishery practice (Hemphill and Shillinger, 2006). To restrict the freedom of fishing on the high seas MPAs, it seems necessary to consider a series of factors such as ecological and environmental effects, economic-development interests of relevant states and scientific research. By offering exceptions for scientific research, these high seas MPAs may be able to gather information regarding other activities which may influence the environment in the relevant areas. This may be beneficial for developing further conservation measures.

For example, the Pelagos Sanctuary prohibits any deliberate capture or deliberate disturbance of mammals. However, non-lethal capture is permitted in case of emergencies or scientific research in the field. For another example, the SOISS MPA prohibits all types of fishing activities by Members. However, there are exceptions in those scientific fishing research activities which have obtained approval from the Commission or other purposes on advice from the Scientific Committee and compliant with Conservation Measure 24-01 are permitted (CCAMLR, 2009 Para 2). In the case of the RSr MPA, fishing by Members is also prohibited. However, there are three kinds of zone in the RSr MPA, namely, the General Protected Area (GPZ), the Special Research Zone (SRZ) and the Krill Research Zone, each of which has applied somewhat different management measures. Vessels of Members can conditionally engage in targeted fishing for Dissostichus spp. in Statistical Subarea 88.1 and SSRUs 882A–B and should be conducted in accordance with Conservation Measures 41-09 and 41-10 (CCAMLR, 2016c Para 28). In addition, for the 2017/18, 2018/19 and 2019/20 fishing seasons, “the catch limit in the Special Research Zone shall be fixed at 15% of the total” (CCAMLR, 2016c Para 28).

Sixth, several legal instruments of the high seas MPAs do not stipulate technical details of fishing restrictions. That might not be beneficial for restricting the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs effectively. For example, in the Pelagos Sanctuary, French fishermen often use a traditional fishing gear called “thonaille”. It is of certain cultural and historical value but will cause 4% of the by-catch, which is harmful to marine mammals in the Pelagos Sanctuary (Pelagos Sanctuary, 2022c). However, Article 7 of the Agreement on the Establishment of a Mediterranean Marine Mammal Sanctuary provides only for the prohibition of drift-net fishing but does not provide for the definition and technical details of drift nets. In addition, there are various definitions for drift nets in the international community. It appears difficult to identify that thonaille should be regarded as a kind of drift net and should be prohibited according to Article 7 of the Agreement on the Establishment of a Mediterranean Marine Mammal Sanctuary. Therefore, thonaille fishing has not been prohibited based on the lack of a specific definition of drift-net fishing.

However, in 2007, the European Union Fisheries Council approved a regulation whose definition of “drift net” definitely included thonaille (European Commission, 2007; Oceana Europe, 2008). In addition, in March 2009, the European Court of Justice held that France failed to fulfil its obligations under the EU regulations by failing sufficiently to prohibit the use of drift nets for capture of certain species (ECJ, 2009). Therefore, thonaille eventually was regarded as an illegal fishing gear based on regulations of the European Union instead of legal instruments regarding the Pelagos Sanctuary. In summary, it can be seen that lacking technical details of restrictions on the freedom of fishing in some high seas MPAs might lead to certain difficulties in the implementation of protecting fishery resources in the high seas MPAs.

4 Suggestions for reasonably restricting the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs from the perspective of international law

Besides these four high seas MPAs, other high seas MPAs proposals such as the East Antarctic Marine Protected Area proposal, the Weddell Sea Marine Protected Area proposal and the Domain 1 Marine Protected Area are in procedures of negotiation (CCAMLR, 2021). The protection of the ABNJ’s environment appears to attract more attention internationally. This article will put forward a number of suggestions for future establishment and development of the high MPAs from the perspective of restricting the freedom of fishing on the high seas.

4.1 The general observation of the principle of reasonably restricting the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs

Reasonably restricting the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs should be developed based on reality and must be a gradual process. First, according to Article 87 of the UNCLOS, the principle of the freedom of the high seas stipulates that high seas should be accessed by all States regardless of their geographical locations. Neither participating in the negotiations of the BBNJ Agreement nor any negotiation outcome will influence the legal position of contracting parties to the UNCLOS, including the high seas freedoms under the UNCLOS (United Nations General Assembly, 2015). Furthermore, 63% of the states supported the position that high seas freedom should be regarded as a principle in the four pre-committee negotiations of the BBNJ Agreement (IISD Reporting Services, 2016a; IISD Reporting Services, 2016b; IISD Reporting Services, 2017a; IISD Reporting Services, 2017b). It seems that the principle of freedom of the high seas is still the basis for states to negotiate the BBNJ Agreement. This is also because the BBNJ Agreement is an international agreement that aims to implement the UNCLOS whose principles should be maintained and developed (Payne, 2019). The freedom of fishing is an important part of the freedom of the high seas. Although this freedom has been limited somewhat on the high seas freedoms to protect the marine environment, such a limitation is based on a theoretical and realistic foundation. In addition, the conflict between the principles of state sovereignty and the freedom of fishing may remain for a long time. On the one hand, the trend of protecting the marine environment cannot be resisted. Because the marine environment is deteriorating and marine biodiversity is threatened, an increasing number of states, international organisations and individuals are concerned about marine environmental protection. Thus, the traditional freedom of fishing has been restricted increasingly. On the other hand, it seems difficult to take any step towards restricting the freedom of fishing in the modern international community, which consists of sovereign states (Wang, 2019). The interests of all states should be taken into account and balanced cautiously, keep perfecting global governance mechanisms and establish restrictions on the freedom of fishing gradually. Consequently, restrictions on the freedom of fishing by sovereign states shall not move forward quickly or develop without any limitation (Wang, 2019). In contrast, the restriction on the freedom of fishing is a slow process. The tendency of the coastal States and the flag States to achieve sophisticated power balances throughout time has led to the development of the high seas freedoms system for a considerable amount of time.

Second, reasonable restrictions on the freedom of fishing should be based on positive law. Natural-law theory prefers to universally apply morality and justice while positive law puts more emphasis on law based on codification or prescription (Singh, 2008). By invoking the natural-law theory, Grotius argued that the marine should be open to any country for sailing and it should not belong to any country (Bull et al., 1992). However, it is not the basis of the modern international law of the sea any longer (Davenport, 2018). This basis has been replaced by the positive-law theory contended by Bynkershoek (Bijnkershoek et al., 1923). Positive law refers to law which stems from a certain sort of source and content (Murphy, 2005). As mentioned above, there are a number of international treaties regulating fishing on the high seas. According to Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), these treaties shall be regarded as applicable law or legal authority of the ICJ when international disputes arise. In addition, the provisions of these treaties have certain content about restricting the freedom of fishing on the high seas as mentioned above. Therefore, the treaties which include these provisions should be regarded as a kind of positive law of the international law. In comparison, the natural-law theory seems to play a far less significant role in the modern international law of the sea because it has been seldom invoked directly by the international community when a fishing dispute arises. One of the reasons may be that the provisions prescribed in international treaties appear more specific and clearer than natural law. They may be more useful for international dispute settlement. Additionally, all states should be subject to limits under the positive-law-based principle of the freedom of the high seas in accordance with their actual needs and with their consent (Wang, 2019). Therefore, on the basis of positive law, high seas freedoms, including the freedom of fishing, cannot be regarded as sacred, inviolable or as a moral advantage used by its supporters. Rather, judgement concerning this freedom shall be in accordance with actual situations (Zhang, 2015).

Third, the establishment of the high seas MPAs is on the basis of the common interests of relevant states. Because countries are still playing the main roles in the practice of international law, the implementation of conservation measures for the high seas MPAs may not succeed without their performance in good faith. The substantial basis of this implementation rests on checks and balances among stakeholders in the current international community. One of the most significant reasons why the establishment of the high seas MPAs can be added to the agenda of the United Nations is that there are common interests among relevant states, particularly the environmental interest. The practices of the four high seas MPAs specifically show that the conservation and management measures of the high seas MPAs to restrict the freedoms of fishing cannot directly impose any legal responsibility to non-contracting parties, but only contracting parties on the basis of their consent (Wang, 2019).

Fourth, restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas cannot be too broad or too narrow. On one hand, as mentioned earlier, the UNCLOS imposes restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas from both general and special perspectives. The terms of these restrictions are relatively broad and might not be implemented well in practice. Therefore, it is important to specify fishing restrictions in the high seas MPAs rather than using general terms or expressions. Specifically, these restrictions should include the following actions: (1) establish a list of species that should be protected in an MPA; (2) establish a prohibited list of fish species, fishing techniques and fishing gears; (3) establish a list of exceptions to restrictions on the freedom of fishing and (4) establish a list of legal consequences for violating conservation and management measures. For example, fishing vessels engaged in IUU fishing should be sanctioned by port states to cooperate with corresponding conservation and management measures or should be prohibited from fishing in relevant high seas MPAs.

On the other hand, fishing in high seas protected areas should not be banned arbitrarily. In 2020, marine fishing captures were 78.8 million tonnes, accounting for 87% of the world’s capture production (FAO, 2022c). In addition, a number of Pacific countries increasingly depend on canned tuna made from tuna caught in the high seas for daily nutrition (Cheung et al., 2019). If the high seas MPAs prohibit all types of fishing, global production of fish might be impacted, which is likely to impact some countries’ food supply to some extent. Therefore, restrictions that are too wide might not achieve the purpose of effectively protecting high seas fishery resources, whereas restrictions that are too narrow might not be conducive to using fishery resources. A balance between protection and sustainably using fishery resources should be achieved by restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas.

4.2 Suggestions for specific measures in the high seas MPAs

Based on lessons of practices in the four high MPAs mentioned above, this article would like to make suggestions for future establishment and development of the high seas MPAs from the perspective of restricting freedom of fishing.

First, restrictions on fishing in the high seas MPAs should be explicit and detailed. First, fishing techniques or fishing gears that have been regarded as harmful to high seas fishery resources should be prohibited explicitly and recorded in the treaties. Resolution 46/215 of the United Nations General Assembly required the international community to take action to ensure that large-scale pelagic drift-net fishing is completely prohibited in the high seas, including enclosed and semi-enclosed seas, by 31 December 1992 (United Nations General Assembly, 1991). Because the resolution did not stipulate a period of prohibition, it seemed that large-scale pelagic drift-net fishing has been banned forever based on that resolution (Zhou, 2006). Therefore, it appears crucial to explicitly prohibit fishing techniques or fishing gears that have been identified by the international community or scientific research as destructive to fishery resources. In addition, restrictions on fishing techniques and fishing gears should be recorded in detail, based on fishing practice and scientific research. For example, there are various types of gill nets to catch different fish during long-term fishing practices (dela Cruz, 1983; NOAA Fisheries, 2021). If the use of certain gill nets in certain high seas MPAs results in an overcatch, a restriction measure can directly prohibit the use of that type of gill net. It should be noted that when setting restrictions on specific fishing techniques or fishing gears, flag states of fishing vessels and RFMOs are supposed to consider relevant fisheries, species and ecosystems (Mooney-Seus and Rosenberg, 2007). In addition, they are expected to refer to the “International Guidelines to Manage Deep-Sea Fisheries in the High Seas”, pay attention to characteristics of various fisheries and promote low-impact fishing techniques and fishing gears (He, 2009).

Second, there should be some exceptions to fishing restrictions in the high seas MPAs. Besides specific situations of other parts of the high seas, the following examples seem worth reference: (1) fishing for the purpose of scientific research that is authorised should be allowed; (2) in emergencies related to human life at sea, conservation or management measures, including reasonable restrictions on the freedom of fishing on the high seas, shall be temporarily inapplicable. These exceptions are likely to contribute to protecting fishery resources in the high seas MPAs while protecting human life in emergencies. In addition, given that scientific research plays a crucial role in protecting designated MPAs or other marine areas (Miller, 2011), scientific research should not be ignored either.

However, the following should be noted when making exceptions: (1) it is important to specify the institution that has the power of making exceptions and granting authorisations; the institution should be an international organisation established by relevant high seas MPA member states. (2) Exceptions should be sufficiently clear and specific to prevent misuse. In addition, it is suggested that the right to interpret exceptions should be granted to institutions that have the power to make exceptions and authorisations. This may facilitate a unified interpretation of relevant rules.

Third, it appears appropriate to establish more advocacy provisions for non-contracting parties in the future. As a fundamental principle of international treaty law, treaties shall not be legally binding to any non-contracting states. As a result, non-contracting parties shall not be subject to any legal obligations under any treaty that seeks to limit the freedom of fishing on the high seas. In other words, those treaties cannot restrict the freedom of fishing of non-contracting parties directly. Nevertheless, that does not mean that non-contracting parties are absolutely free from any obligation of protecting high seas fishery resources.

As mentioned previously, the SOISS MPA and RSr MPA have established advocacy provisions for non-contracting parties. These provisions are not likely to bring burdens to non-contracting parties but can better protect high seas fish resources. Other high seas MPAs can consider setting provisions that encourage non-contracting parties’ fishing vessels to notify competent authorities of their intended transit when passing through the high seas MPAs and can provide their flag state, size, IMO Number and intended course. In terms of terminology, it is recommended that when prescribing advocacy provisions, phrases such as “as far as possible”, “best effort”, “cooperation”, “intensified prevention” and “gradual reduction” should be used. These terms can reflect respect for non-contracting states and do not impose mandatory international law obligations compared to words such as “shall”. Moreover, compared with “might”, expressions such as “as far as possible” suggest that non-contracting parties should make their best efforts in good faith instead of taking action casually.

Fourth, regarding combating IUU fishing, international cooperation should be strengthened through global information exchange (IUCN, 2006). The reason IUU fishing has not been eliminated is the insufficient control capacity of flag states and weak enforcement of coastal States (Liu, 2016). If port states cannot exchange information with relevant states or fishery organisations in time, it will be difficult for them to effectively control IUU fishing vessels in their port in time. However, based on the current practice of RFMOs, a number of States may tend not to take part in relevant organizations or arrangements since they may not be incentive enough to fulfil the relevant obligations (Constable, 2011). Stakeholders including the organizations and the States of the high seas MPAs may not be able to acquire enough information regarding fishery in the relevant areas. The effectiveness of measures combating IUU fishing may be influenced. A better approach for future restriction on the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs appears cooperation based on an international instrument applicable to more states. The Agreement on Port State Measures (PSMA), which was established in 2009 and put into effect in 2016, is the most significant international legal document involving regulation of IUU fishing by port states as it was the first legally binding agreement to expressly combat IUU fishing. From 31 May to 4 June 2021, the FAO held the third Conference of the Parties on the PSMA (FAO, 2022b). During this meeting, the consensus was that contracting parties are expected to achieve adequate international cooperation and adequate institutional capacity to implement port state measures, particularly by developing states (FAO, 2021b). In addition, it is intended to foster better regional collaboration and international information sharing.

At present, contracting parties to the PSMA have agreed to the FAO to establish the PSMA Global Information Exchange System (GIES) (FAO, 2021a). This system enables the transmission of crucial information such as refusals of port entry (FAO, 2021a). In addition, inspection reports regarding fishing vessels under suspicion of having engaged in IUU fishing can also be uploaded in real time (FAO, 2021a). Furthermore, non-contracting parties of the PSMA can also access information related to them through the system (FAO, 2022a). In other words, the system is open for information exchange. Non-contracting parties can access important information even though they have not acceded to the PSMA. That might encourage them to take part in the international cooperation in combating IUU fishing. To strengthen global information exchange regarding regulating IUU fishing, the high seas MPAs are expected to encourage their members who are contracting parties of the PSMA to promote the GIES and encourage their members who are non-contracting parties of the PSMA to take part in the system or to access relevant information regularly. This might contribute to maintaining appropriate restrictions on IUU fishing by improving port state measures and protecting fish resources in the high seas MPAs.

5 Conclusions

The freedom of the high seas based on traditional theories is becoming increasingly restricted. Practitioners and scholars have been aware that the reasonable restriction of the freedom of fishing in the high seas MPAs is worth concern and further research. The fishing-restriction measures stipulated in international treaties represented by the UNCLOS seem too general for practice. In addition, some treaties do not address certain issues, such as how to restrict fishing methods by non-contracting parties. Regarding the practice of the four high seas MPAs that have been established by the international community, several reasonable fishing restrictions have been established, but there is a lack of stipulations in relation to the technical details of fishing restrictions. From the perspective of international law, to protect the environment of the high seas and sustainably use fishery resources in the high seas, it is important to improve the principle of reasonably restricting the freedom of fishing in MPAs on the high seas based on practice and positive law while proceeding steadily. In addition, restriction measures cannot be too broad or narrow. Specifically, we should continue to develop mechanisms such as exceptions, ways of restricting fishing, advocacy provisions for non-contracting parties and measures to strengthen international information exchange for combating IUU fishing.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/supplementary material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author/s.

Author contributions

YW and XP contributed to conception and design of the study. YW and XP wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to manuscript revision, read, and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work is supported by 2023 doctoral dissertation funding project of East China University of political science and Law — Study on the application of the Principle of Common but Differentiated Responsibilities in the environmental governance of the high seas.

Acknowledgments

Shiqi Liu provided proofreading and gathered basic information for a number of sections.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Accord Relatif A La Creation En Mediterranee D’un Sanctuaire Pour Les Mammiferes Marins (1999). Available at: https://www.sanctuaire-pelagos.org/en/resources/official-documents/version-francaise/texte-de-l-accord/20-accord-relatif-a-la-creation-d-un-sanctuaire-pour-les-mammiferes-marins-en-mediterranee/file (Accessed 11 June 2022).

Bijnkershoek C. V., et al. (1923) De dominio maris dissertatio. new York: Oxford university press (Classics of international law, no. 11). Available at: https://libproxy.berkeley.edu/login?qurl=http%3A%2F%2Fheinonline.org%2FHOL%2FIndex%3Findex%3Dbeal%2Fcilnr%26collection%3Djournals (Accessed 11 June 2022).

Bull H., Kingsbury B., Roberts A. (Eds.) (1992). Hugo Grotius and international relations (New York, the United States: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/0198277717.001.0001. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/book/26924. (Accessed 30 March 2023).

Burke W. T. (1984). Highly migratory species in the new law of the sea. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 14 (3), 273–314. doi: 10.1080/00908328409545756

CCAMLR (2006) Resolution 25/XXV combating illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing in the convention area by the flag vessels of non-contracting parties. Available at: https://cm.ccamlr.org/sites/default/files/r25-xxv_4.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2022).

CCAMLR (2009) Conservation measure 91-03 (2009) protection of the south Orkney islands southern shelf. Available at: https://cm.ccamlr.org/en/measure-91-03-2009 (Accessed 11 June 2022).

CCAMLR (2016a) Conservation measure 10-06 (2016), scheme to promote compliance by non-contracting party vessels with CCAMLR conservation measures. Available at: https://cm.ccamlr.org/measure-10-06-2016 (Accessed 11 June 2022).

CCAMLR (2016b) Conservation measure 10-07 (2016), scheme to promote compliance by non-contracting party vessels with CCAMLR conservation measures. Available at: https://cm.ccamlr.org/en/measure-10-07-2016 (Accessed 11 June 2022).

CCAMLR (2016c) Conservation measure 91-05 (2016) Ross Sea region marine protected area. Available at: https://cm.ccamlr.org/en/measure-91-05-2016 (Accessed 11 June 2022).

CCAMLR (2016d) Ross Sea Region marine protected area (RSr MPA) | CCAMLR MPA information repository. Available at: https://cmir.ccamlr.org/node/1 (Accessed 11 June 2022).

CCAMLR (2021) Report of the fortieth meeting of the commission. Available at: https://www.ccamlr.org/en/system/files/e-cc-40-rep.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2022).

Chair of Preparatory Committee established by General Assembly resolution 69/292 (2017) Chair’s streamlined non-paper on elements of a draft text of an international legally binding instrument under the united nations convention on the law of the Sea on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. Available at: https://www.un.org/depts/los/biodiversity/prepcom_files/Chairs_streamlined_non-paper_to_delegations.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2022).

Cheung W., Lam V., Wabnitz C. (2019). Future scenarios and projections for fisheries on the high seas under a changing climate. IEED Working Paper, 1–43. doi: 10.13140/RG.2.2.11043.81440

Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries (1995). Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/v9878e/v9878e.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2022).

Constable A. J. (2011). Lessons from CCAMLR on the implementation of the ecosystem approach to managing fisheries: Lessons from CCAMLR on EBFM. Fish. Fish. 12 (2), 138–151. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-2979.2011.00410.x

Crawford J. (2002). The ILC’s articles on responsibility of states for internationally wrongful acts: A retrospect. Am. J. Int. Law 96 (4), 874–890. doi: 10.2307/3070683

Cullis-Suzuki S., Pauly D. (2010). Failing the high seas: A global evaluation of regional fisheries management organizations. Mar. Policy 34 (5), 1036–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2010.03.002

Davenport T. (2018). The high seas freedom to lay submarine cables and the protection of the marine environment: Challenges in high seas governance. American Journal of International Law Unbound (AJIL Unbound) 112, 139–143. doi: 10.1017/aju.2018.48

Day J., Dudley N., Hockings M., Holmes G., Laffoley D., Stolton S., et al (2019) Guidelines for applying the IUCN protected area management categories to marine protected areas (IUCN). Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/48887 (Accessed 27 January 2023).

dela Cruz C. R. (1983) Fishpond engineering: A technical manual for small-and medium-scale coastal fish farms in southeast Asia (FAO). Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/e7171e/E7171E07.htm (Accessed 11 June 2022).

Druel E. (2011)Marine protected areas in areas beyond national jurisdiction: The state of play. In: SciencesPo. IDDRI working paper. Available at: https://www.iddri.org/sites/default/files/import/publications/wp-0711-abnj-e.-druel.pdf (Accessed 11 September 2011).

Dunlap W. V. (1994). “Canada Asserts jurisdiction over high seas fisheries,” in IBRU boundary and security bulletin. (Durham, the United Kindom: IBRU Centre for Borders Research), vol. 63.

ECJ (2009) Commission of the European communities v French republic. failure of a member state to fulfil obligations - common fisheries policy - regulation (EC) no 894/97 - drift net - meaning - ‘Thonaille’ fishing net - prohibition on the fishing of certain species - regulations (EEC) no 2847/93 and (EC) no 2371/2002 - lack of an effective system of monitoring to ensure compliance with that prohibition. the European court of justice. case c-556/07. Available at: https://curia.europa.eu/juris/document/document.jsf?docid=78094&mode=req&pageIndex=1&dir=&occ=first&part=1&text=&doclang=EN&cid=1185518 (Accessed 11 June 2022).

European Commission (2007) Council regulation (EC) no 809/2007 of 28 June 2007 amending regulations (EC) no 894/97, (EC) no 812/2004 and (EC) no 2187/2005 as concerns drift nets., OJ l. Available at: http://data.europa.eu/eli/reg/2007/809/oj/eng (Accessed 11 June 2022).

FAO (2021a) PSMA parties launch GIES pilot phase. global capacity development portal online | agreement on port state measures (PSMA) | food and agriculture organization of the united nations. Available at: https://www.fao.org/port-state-measures/news-events/detail/en/c/1403823/ (Accessed 11 June 2022).

FAO (2021b). Report of the third meeting of the parties to the agreement on port state measures to prevent, deter and eliminate illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing. FAO. doi: 10.4060/cb6596en

FAO (2022a) Frequently asked questions | FAO global record. Available at: https://psma-gies.review.fao.org/zh/faq (Accessed 11 June 2022).

FAO (2022b) Meetings of the parties | agreement on port state measures (PSMA) | food and agriculture organization of the united nations. :1–42 Available at: https://www.fao.org/port-state-measures/meetings/meetings-parties/en/ (Accessed 11 June 2022).

FAO (2022c). Towards blue transformation (Rome: The state of world fisheries and aquaculture). Available at: https://doi.org/10.4060/cc0461en.

Freestone D. (1999). “International fisheries law since Rio: The continued rise of the precautionary principle,” in International law and sustainable development: Past achievements and future challenges. Eds. Boyle A., Freestone D. (New York, the United States: Oxford University Press). doi: 10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198298076.003.0007. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/book/34680/chapter-abstract/295618273?redirectedFrom=fullt. (Accessed 30 March 2023).

Freestone D. (2018). The limits of sectoral and regional efforts to designate high seas marine protected areas. AJIL Unbound 112, 129–133. doi: 10.1017/aju.2018.45

Fu K. (2005). Related Conventions on the Law of the Sea with A Chinese English Index. (Xiamen, Fujian, China: Xiamen University Press).

GFCM (2006) Recommendation GFCM/30/2006/2 on the establishment of a closed season for common dolphinfish fisheries using FADs. Available at: https://www.fao.org/gfcm/managementplan-dolphinfish (Accessed 29 January 2023).

GFCM (2013) Resolution GFCM/37/2013/1 on area based management of fisheries, including through the establishment of fisheries restricted areas (FRAs) in the GFCM convention area and coordination with the UNEP-MAP initiatives on the establishment of SPAMIs. Available at: https://gfcmsitestorage.blob.core.windows.net/documents/Decisions/GFCM-Decision–RES-GFCM_37_2013_1-en.pdf (Accessed 28 January 2023).

GFCM (2019) Recommendation GFCM/43/2019/1 on a set of management measures for the use of anchored fish aggregating devices in common dolphinfish fisheries in the Mediterranean Sea. Available at: https://gfcm.sharepoint.com/CoC/Decisions%20Texts/Forms/AllItems.aspx?id=%2FCoC%2FDecisions%20Texts%2FREC%2ECM%5FGFCM%5F43%5F2019%5F1%2De%2Epdf&parent=%2FCoC%2FDecisions%20Texts&p=true&originalPath=aHR0cHM6Ly9nZmNtLnNoYXJlcG9pbnQuY29tLzpiOi9nL0NvQy9FWE8wNnJDSTkyTkdneHdBaHhYZ3JKOEJYUUF2VnAyYnoyQV9oRE5naEhNQ1dBP3J0aW1lPUNpUDZ2N3ZjMkVn (Accessed 29 January 2023).

GFCM (2021) GFCM/44/2021/10 on flag state performance. In: Available at: https://gfcm.sharepoint.com/CoC/Decisions%20Texts/Forms/AllItems.aspx?id=%2FCoC%2FDecisions%20Texts%2FRES%2DGFCM%5F44%5F2021%5F10%2De%2Epdf&parent=%2FCoC%2FDecisions%20Texts&p=true&ga=1.

GFCM (2023a) Dolphinfish management plan | general fisheries commission for the Mediterranean - GFCM | food and agriculture organization of the united nations | general fisheries commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) | food and agriculture organization of the united nations. Available at: https://www.fao.org/gfcm/managementplan-dolphinfish (Accessed 27 January 2023).

GFCM (2023b) European Eel management plan | general fisheries commission for the Mediterranean - GFCM | food and agriculture organization of the united nations | general fisheries commission for the Mediterranean (GFCM) | food and agriculture organization of the united nations. Available at: https://www.fao.org/gfcm/managementplan-europeaneel (Accessed 27 January 2023).

Grafton R. Q., Hilborn R., Squires D., Tait M., Williams M. J. (Ed.) (2010). Handbook of marine fisheries conservation and management (New York: Oxford University Press).

He X. (2009). Research on the legal issues of the fisheries management system in the high seas. [master's thesis]. (Chongqing: Southwest University of Political Science and Law). Available at: https://scholar.google.com/scholar?hl=zh-CN&as_sdt=0%2C5&q=%E5%85%AC%E6%B5%B7%E6%B8%94%E4%B8%9A%E7%AE%A1%E7%90%86%E5%88%B6%E5%BA%A6%E6%B3%95%E5%BE%8B%E9%97%AE%E9%A2%98%E7%A0%94%E7%A9%B&&btnG=.

Helm R. R., Clark N., Harden-Davies H., Amon D., Girguis P., Bordehore C. (2021). Protect high seas biodiversity. Sci. (New York N.Y.) 372 (6546), 1048–1049. doi: 10.1126/science.abj0581

Hemphill A., Shillinger G. (2006). Casting the net broadly: Ecosystem-based management beyond national jurisdiction. Sustain. Dev. Law Policy 7 (1), 56–59.

Henriksen T., Hønneland G., Sydnes A. K. (2006). Law and politics in ocean governance: the UN fish stocks agreement and regional fisheries management regimes Vol. 52 (Leiden Boston: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers (Publications on ocean development).

Higginson C. (1993). The UN conference on high seas fishing. Rev. Eur. Community Int. Environ. Law 2 (3), 237–243. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-9388.1993.tb00118.x

IISD Reporting Services (2016a). Summary of the first session of the preparatory committee on marine biodiversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction:28 march – 8 April 2016. Earth Negotiations Bull. 25 (106), 1–21. Available at: https://enb.iisd.org/download/pdf/enb25106e.pdf. (Accessed: 11 June 2022).

IISD Reporting Services (2016b). Summary of the second session of the preparatory committee on marine biodiversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction:26 august – 9 September 2016. Earth Negotiations Bull. 25 (118), 1–22. Available at: https://enb.iisd.org/download/pdf/enb25118e.pdf (Accessed: 11 June 2022).

IISD Reporting Services (2017a) Summary of the fourth session of the preparatory committee on marine biodiversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction: 10-21 July 2017. Available at: https://s3.us-west-2.amazonaws.com/enb.iisd.org/archive/download/pdf/enb25141e.pdf?X-Amz-Content-Sha256=UNSIGNED-PAYLOAD&X-Amz-Algorithm=AWS4-HMAC-SHA256&X-Amz-Credential=AKIA6QW3YWTJ6YORWEEL%2F20220611%2Fus-west-2%2Fs3%2Faws4_request&X-Amz-Date=20220611T095844Z&X-Amz-SignedHeaders=host&X-Amz-Expires=60&X-Amz-Signature=97dfd6d1a0bca91b12b2e50fb28d98479616d2a4f5dcd9c792960358786e9be5 (Accessed 11 June 2022).

IISD Reporting Services (2017b) Summary of the third session of the preparatory committee on marine biodiversity beyond areas of national jurisdiction: 27 march – 7 April 2017. Available at: http://enb.iisd.org/download/pdf/enb25129e.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2022).

Islam M. R. (1991). The proposed “Driftnet-free zone” in the south pacific and the law of the Sea convention. Int. Comp. Law Q. 40 (1), 184–198. doi: 10.1093/iclqaj/40.1.184

IUCN (2006) Closing the net : stopping illegal fishing on the high seas (UK: High Seas Task Force). Available at: https://portals.iucn.org/library/node/8890 (Accessed 27 January 2023).

Liu N. (2016). Analysis of port states' measures to Limit IUU Fishing. Ocean Develop. Manage. 7, 74–77. doi: 10.20016/j.cnki.hykfygl.2016.07.015

Lodge M. W., Anderson D., Løbach T., Munro G., Sainsbury K., Willock A. (2007). Recommended best practices for regional fisheries management organizations: Report of an independent panel to develop a model for improved governance by regional fisheries management organizations. report (Chatham House: Chatham House). Available at: https://doi.org/10.25607/OBP-958.

Miller D. (2011). “Sustainable management in the southern ocean: CCAMLR science,” in Science diplomacy: Science, Antarctica, and the governance of international spaces (Washington D.C., The United States: Smithsonian Institution Scholarly Press), 103–121. doi: 10.5479/si.9781935623069.103

Molenaar E. J. (2007)Current legal and institutional issues relating to the conservation and management of high seas deep-sea fisheries. In: FAO fisheries report (FAO). expert consultation on deep-sea fisheries in the high seas, Bangkok (Thailand), 21-23 Nov 2006 (FAO). Available at: http://www.fao.org/docrep/010/a1341e/a1341e00.htm (Accessed 27 January 2023).

Mooney-Seus M. L., Rosenberg A. A. (2007). Best practices for high seas fisheries management: Lessons learned (London, England, the United Kindom: Chatham House). doi: 10.25607/OBP-957

Murphy J. B. (2005). “Natural, customary, and positive law,” in The philosophy of positive law: Foundations of jurisprudence. Ed. Murphy J. B. (New Haven and London: Yale University Press). doi: 10.12987/yale/9780300107883.003.0001. Available at: https://academic.oup.com/yale-scholarship-online/book/14323/chapter-abstract/168243102?redirectedFrom=fulltext.

NEAFC (2005) NEAFC a and b lists | north-East Atlantic fisheries commission. Available at: https://www.neafc.org/mcs/iuu (Accessed 11 June 2022).

NEAFC (2015) Recommendation on conservation of sharks caught in association with fisheries managed by the north-East Atlantic fisheries commission. Available at: https://www.neafc.org/system/files/Rec10_Shark-fins.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2022).

NEAFC (2022) NEAFC scheme of control and enforcement. Available at: https://www.neafc.org/scheme (Accessed 28 January 2023).

NOAA Fisheries (2021) Fishing gear: Gillnets | NOAA fisheries. Available at: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/national/bycatch/fishing-gear-gillnets (Accessed 11 June 2022).

Oceana Europe (2008) Thonaille: The use of driftnets by the French fleet in the mediterranean. results of the oceana 2007 campaign. Available at: https://europe.oceana.org/sites/default/files/reports/Rederos_Franceses_2007_ING.pdf (Accessed 11 June 2022).