- ARC Centre of Excellence for Coral Reef Studies, James Cook University, Townsville, QLD, Australia

This paper reviews the concept of governance in protected areas, providing details about nine key principles of governance as they relate to marine protected areas (MPAs). Following a theoretical description of each principle, real-world examples of the principles are presented from the Great Barrier Reef (GBR) Marine Park, where marine governance has evolved over 45 years as part of adaptive management. Examples of good governance in the GBR include the intergovernmental arrangements that enable both federal and state governments to co-operate effectively across adjoining marine jurisdictions. In addition, the application of multiple layers of management adds to an effective integrated approach, considered to be the most appropriate for managing a large MPA. The nine governance principles discussed in the paper are applicable to all MPAs, but how they are applied will vary in dissimilar settings because of differing environmental, social, economic, cultural, and political contexts - clearly, one size does not fit all. The analogy of the nine principles being part of an interlaced or woven ‘lattice’ is also introduced. Collectively the lattice is stronger than any individual principle, and together all principles contribute to the totality of effective governance. The paper provides information for those involved in MPA management who are keen to understand marine governance and how it might apply to their MPA, recognising there will be differences in how the principles will apply.

Introduction

What is governance in natural resource management?

In its simplest terms, ‘governance’ may be described as the process of decision-making, and the subsequent process by which decisions are, or are not, implemented. As Ruhanen et al. (2010) explain, governance is not a synonym for government, as governance involves a multitude of stakeholders and is therefore much broader than government.

Governance is a fundamentally important component of natural resource management. As Borrini-Feyerabend et al. (2013, p. xii) assert, “Governance is a main factor in determining the effectiveness and efficiency of management. Because of this, it is of great interest to governments, funding agencies, regulatory bodies and society in general”.

The difference between governance and management in natural areas is clarified in the Guidelines published by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN):

● “Management is about … what is done in pursuit of given objectives - the means and actions to achieve such objectives;

● Governance is about … who decides what the objectives are, what to do to pursue them, and with what means - how those decisions are taken - who holds power, authority and responsibility - who is (or should be) held accountable.” (Borrini-Feyerabend et al., 2013, p. 11)

The concept of governance has been discussed and documented by a multitude of authors; for example, Weiss (2000) provides a wide variety of definitions from various international organisations. Other examples, each defining ‘governance’ in a slightly different way; include:

● “The involvement of a wide range of institutions and actors in the production of policy outcomes … involving coordination through networks and partnerships” (Johnston et al., 2000, p.317).

● “… a process whereby societies or organizations make their important decisions, determine whom they involve in the process … - that is, the agreements, procedures, conventions or policies that define who gets power, how decisions are taken and how accountability is rendered” (Graham et al., 2003, p.1).

● “The processes and structures of public policy decision making and management that engage people constructively across the boundaries of public agencies, levels of government, and/or the public, private and civic spheres in order to carry out a public purpose that could not otherwise be accomplished” (Emerson et al., 2012, p.2).

● “Adaptive governance refers to flexible and learning-based collaborations and decision-making processes involving both state and nonstate actors, often at multiple levels, with the aim to adaptively negotiate and coordinate management of social– ecological systems and ecosystem services across landscapes and seascapes” (Schultz et al., 2015, p.7369).

● “Governance is generally defined as the institutions, structures, and processes that determine who makes decisions, how and for whom decisions are made, whether, how and what actions are taken and by whom and to what effect” (Bennett and Satterfield, 2018, p. 2).

Although there are some common elements within all the above definitions, there seems no firm agreement on what precisely constitutes governance. There are different ways in which environmental governance structures and processes may be applied - they may be ‘top-down’ (driven from the top by governments or private individuals, especially in countries with relatively well developed legal, bureaucratic and political systems), ‘bottom-up’ (driven by local communities or user-led), or a combination including ”…shared decision-making and authority through formal co-management arrangements or informal networks of actors and organizations” (Bennett and Satterfield, 2018, p.6). Jones (2012) notes that top-down approaches tend to dominate, but this does not mean that they cannot be combined with bottom-up approaches. As Christie and White (2007) report, there are advantages of bottom-up strategies as they can engage resource users more effectively, leading to a sense of trust, collaboration and ownership amongst participants. In some countries, top-down strategies may be perceived as having the benefits of a sound scientific basis, or there may be statutory requirements for consultative participation or implementation end-products such as a zoning plan. Jones and Long (2021) assessed 28 case studies of marine protected areas (MPAs) that used a range of governance approaches, and concluded each approach had their respective strengths and weaknesses, and there were benefits if various approaches were functionally integrated.

Given the fact that governance can be applied in different ways, and there appears no firm agreement as to what constitutes governance, the advice of Borrini-Feyerabend et al. (2013), seems appropriate, given they state:

“There is no “ideal governance setting” for all protected areas, nor an ideal to which governance models can be compared, but a set of “good governance” principles [that] can be taken into account vis-à-vis any protected area system or site. These principles provide insights about how a specific governance setting will advance or hinder conservation, sustainable livelihoods and the rights and values of the people and country concerned”. (2013, p. xii).

What are the key principles of good governance?

What constitutes the principles of good governance for protected areas have similarly been described by many authors; for example:

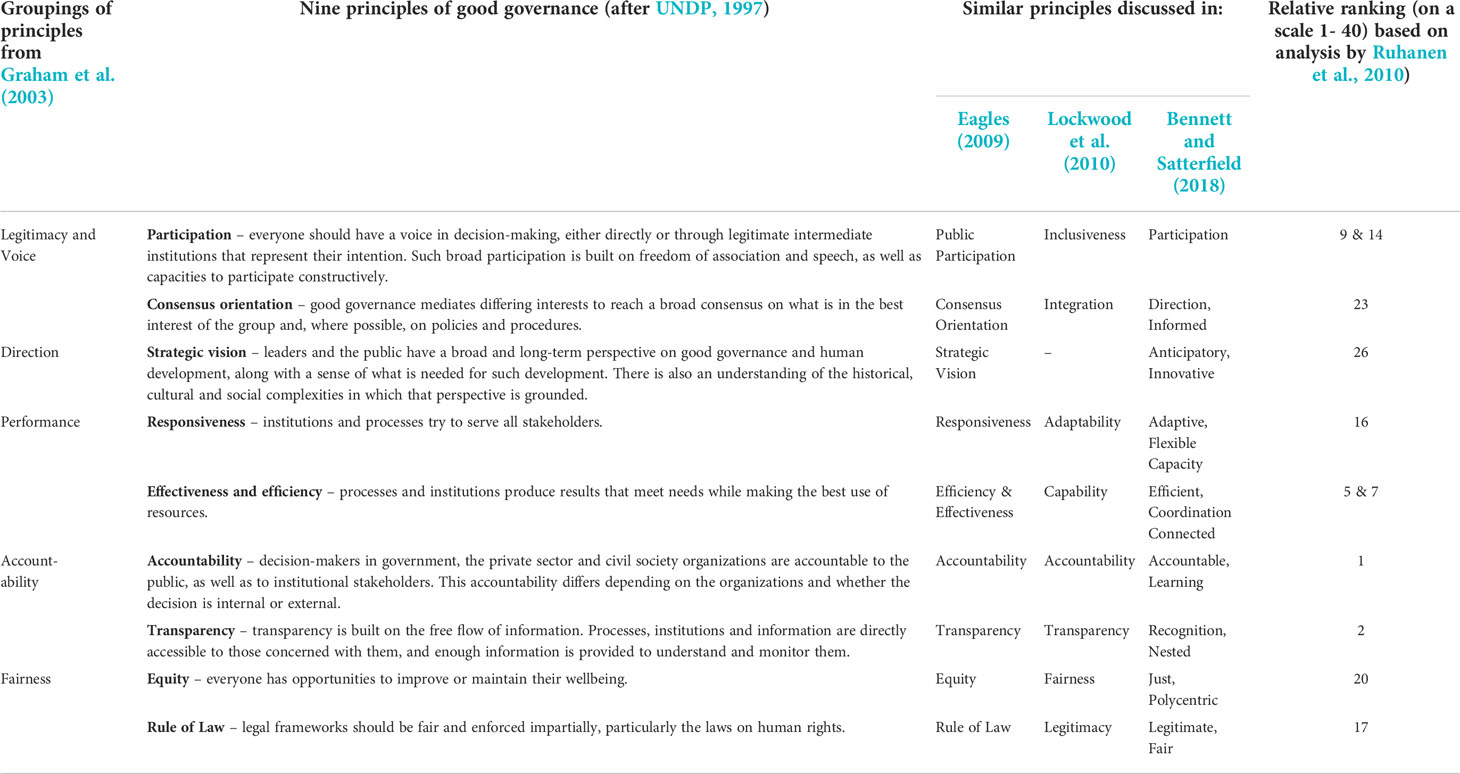

● UNDP (1997) listed nine principles of good governance (Table 1)

● Graham et al. (2003) grouped some of the nine principles from UNDP (1997), suggesting there are five principles of good governance

● Lockwood et al. (2010) characterized good governance according to a set of eight principles very similar to those promoted by UNDP (1997)

● Young et al. (2007) proposed four core principles that are particularly relevant to the place-based management of marine ecosystems

● Jones (2014) provided a governance framework that considered 36 incentives grouped into five broad categories; economic, communication, knowledge, legal and participation.

● Ruhanen et al. (2010) conducted a meta-analysis of 53 published governance studies, identifying and ranking 40 different dimensions or principles of governance.

● Bennett and Satterfield (2018) developed a list of 19 attributes that were then assigned to four overarching categories.

Table 1 Nine key principles of good governance [after UNDP (1997) and adapted by Graham et al. (2003) ].

When considering what might be the principles of good governance, Graham et al. (2003) recognise “… these principles often overlap or are conflicting at some point, that they play out in practice according to the actual social context, that applying such principles is complex, and that they are all about not only the results of power but how well it is exercised” (p. 3). Nevertheless, Graham et al. (2003) concluded that the principles of governance “… can be usefully applied to help deal with current governance challenges”. However, they also warn, “When they are applied it becomes apparent that there are no absolutes; that principles often conflict; that the ‘devil is in the detail’; that context matters.” (p. 6).

Table 1 has been developed to show the correlations between the various governance principles put forward by well-respected authors in the governance field. It lists the nine principles of good governance from UNDP (1997), shows how these principles have been clustered into five broad groups (Graham et al., 2003), and the corresponding principles as defined by others (e.g., Eagles, 2009; Lockwood et al., 2010; Bennett and Satterfield, 2018). As shown in Table 1, there is considerable overlap between the UNDP list and the 40 different dimensions or principles of governance identified by Ruhanen et al. (2010); the relative ranking of each principle is also shown based on a frequency count derived by Ruhanen et al. (2010) from their analysis of the published articles.

As Jones et al. (2013) point out, when considering the various approaches to natural resource governance, there is “… a vast literature on the relative merits … and many definitions of governance”. A similar view is expressed by Weiss (2008); Borrini-Feyerabend et al. (2013); Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill (2015), and Bennett and Satterfield (2018). Increasingly there is a focus specifically on marine governance (e.g., Christie and White, 2007; Fanning et al., 2007; Jones et al., 2011; McCay and Jones, 2011; Bown et al., 2013; Day and Dobbs, 2013; Jones et al., 2013; Gaymer et al., 2014; Jones, 2014; Jones and Long, 2021). However, many of these papers are comparatively theoretical, or are so comprehensive that they are consequently less useful for those specifically involved in practical MPA management.

How might this information help those responsible for MPA management?

The principles of ‘good governance’ outlined in this paper can be applied in all types of protected areas, whether they are in terrestrial or marine environments. However, how some of the principles are applied in the marine environment may differ given the differences compared to the terrestrial realm. As Rice (1985) warned, “marine ecosystems are not simply wet salty terrestrial ones”; problems can arise if it is assumed that knowledge gained from managing terrestrial ecosystems can be applied directly to marine contexts. The fact most of the marine environment is hidden from human sight (‘out of sight, out of mind’) and the vastness of the oceans have contributed to many misunderstandings about the marine environment and how it needs to be managed. For example, identifying MPA or zone boundaries at sea, and effectively communicating those boundaries to users is far harder than on land. Widely differing components of the marine realm (e.g. littoral, epipelagic, mesopelagic, bathypelagic, benthic) may also need to be managed differently.

Having considered many of the available references, there appears to be no agreed, conclusive or definitive list of principles for good governance that is specifically applicable to MPAs. Given that some principles overlap, and others may conflict at some point (Graham et al., 2003), I have chosen to revert to the original nine principles from UNDP (1997) while recognising there are many similarities with other lists and groupings of principles as shown in Table 1. From my experience, the comparatively simple list of nine key governance principles provides a sufficient level of complexity to be useful for MPA managers.

The specific information relating the principles to the marine environment is intended to provide those involved in all aspects of MPA management with a better understanding of marine governance, thereby enabling them to move incrementally toward more effective governance in their MPA. Having identified these principles, Part 2 explains each principle in more detail providing a marine focus. Some real-world examples (both good and bad) of each principle are then provided in Part 3, drawing upon the experience in the Great Barrier Reef (GBR), a globally recognised MPA that has been functioning since the mid-1970s. Finally, Part 4 discusses how these principles might be applied in an individual MPA, recognising the wide degree of divergence across the world’s MPAs.

Explaining the nine key principles of good governance

Participation

Public participation (sometimes referred to as ‘public engagement’, ‘community participation’, or ‘stakeholder involvement’) is widely acknowledged as a key component of effective governance. Defined as the involvement of those affected by a decision in a decision-making process, public participation is an essential part of effective decision-making. VAGO (2015: p.2) maintains “… the credibility of a decision is enhanced when it is perceived to be the product of an open and deliberative process”, and Appelstrand (2002: p.289) refers to public participation as constituting “a prerequisite for legitimacy - and thus acceptance of laws … and decisions.”

Some critics, however, suggest that public participation programs only exist to satisfy legal requirements or perceived ethical ones; others maintain public participation is ineffective and inefficient. Considering Arnstein’s (1969) ‘ladder of participation’, public participation needs to be more than simply informing or educating the public, rather it must involve effectively consulting the public and negotiating options, and with more than a few select stakeholders or just the local community. The time and resources required for effective public engagement are not insignificant; consequently, it is not uncommon for effective public engagement to necessitate more time and resources than were initially envisaged (Day, 2017).

Notwithstanding the critics, the value of effective public participation is endorsed by many authors (e.g., Petts and Leach, 2000; Bäckstrand, 2003; Rowe and Frewer, 2005; Petts, 2006; Innes and Booher, 2007; Petts 2008; Reed, 2008; Birnbaum et al., 2015; VAGO, 2015). Advocates maintain it improves the quality and legitimacy of a decision, while building the capacity of all involved to engage more effectively in the policy process (Stern and Dietz, 2008). Lundquist and Granek (2005) also observe that one characteristic emphasized in most successful global marine conservation efforts is the importance of incorporating stakeholders at all phases of the process. Bennett et al. (2019) found that employing good governance processes and managing social impacts was more important than ecological effectiveness for maintaining local support for conservation. Few authors, however, specifically discuss how public participation should be undertaken for different aspects of governance; for example, during different stages of a planning process, or tailoring key messages in different but appropriate ways for different groups of stakeholders. Dehens and Fanning (2018) do discuss ten indicators spread across different stages of the MPA process.

Consensus orientation

Good governance aims to mediate differing interests to reach broad agreement on what is in the best interest of the constituents and, where possible, on policies and procedures. Many decision makers are keen to encourage consensus-based decisions, seeking agreement that meets the interests of all stakeholders. A consensus building approach may maximize possible gains for the stakeholders involved but may not necessarily be the best decision when evaluated against the ecological objectives for an MPA or against what the broader society desires for the area (e.g., the national or international community rather than just the local community). To ensure a consensus view among stakeholders is not in direct opposition to the statutory or regulatory directives or objectives, it is important to clearly explain those objectives before entering any negotiations.

In a similar way, the concept of a ‘win-win’ for all those concerned may seem a worthy aim, but it is rarely a realistic outcome in large complex MPAs where no single solution is likely to satisfy all users, stakeholders, and rights-holders. Some stakeholders may form coalitions with others who share similar goals, and this may enable them to reach new and innovative solutions to problems; however, sometimes such coalitions fail over time due to power struggles or infighting. Bennett and Dearden (2014) also caution against this win-win way of thinking:

‘The proposition that MPAs both can and should lead to win-win outcomes for conservation and development thus satisfying the needs of conservationists, governments, fishers, tourism operators, and local communities is becoming the dominant paradigm. However, the successful achievement of this dual mandate is more complex in reality than in theory….’ (Bennett and Dearden, 2014, p.96).

Brueckner-Irwin et al. (2019) describe how many MPA processes fit poorly with the local context because they do not effectively consider social and ecological dynamics. They suggest that decision makers need to consider how communities define effective collaboration and create transparent opportunities for participation to improve perceptions of fairness.

Strategic vision

A strategic vision provides a sense of purpose and a broad direction and goals for any organisation. A good vision needs to define the short and long-term goals (“where we are going”) and guide the decisions that need to be made along the way (“what is needed to achieve this vision?”). Nanus (1992) and Zaccaro and Banks (2001) consider that to be most effective, a strategic vision should contain five elements:

i. a picture of the future that is better than the status quo

ii. a change, moving towards something more positive (usually taking the best features of a previous system and strengthening them)

iii. values or the ideas and beliefs that people find worthwhile or desirable

iv. a ‘roadmap’ that sets out the route and milestones, so followers know if they are on the right course; and

v. a challenge.

Covey (1991) suggests having a clear strategic vision is one of the seven habits of highly effective people. An effective leader should therefore be able to successfully communicate their vision, thereby providing a clear direction for their organisation or team. If an organisation is undergoing transformational change (i.e., change that is radical, comprehensive or large scale), the key steps identified by Kotter (1995) include creating a new vision, communicating that vision, empowering others to act on that vision, and institutionalising the necessary changes by revamping the organisational culture.

Responsiveness

Responsiveness means responding to an issue with a timely decision(s) that leads to appropriate and timely action(s). This may contribute to the achievement of existing goals and objectives but may also address an unforeseen issue. Any successful marine management system must be responsive and able to incorporate changes such as new information becoming available or changing circumstances. Irrespective of whether the change results from ‘in-the-field’ experience, from new data, or because of an unexpected event (e.g., a ship grounding or an oil spill), marine management practices must be periodically reviewed and updated. Some pre-planning should be undertaken (e.g., risk management preparedness), as a complex or unwieldy hierarchical organisation can hamper being able to react quickly, and delays or an inability to respond in a timely way may exacerbate the problem.

As noted by Graham et al. (2003), some governance principles may conflict at some point (e.g., responsiveness can sometimes conflict with either public participation or consensus decision-making); when this becomes apparent, it is important to consider the relevant principles in the overall context and the objectives of the MPA (usually defined in the legislation). When managing natural resources, adaptive management is a responsive approach for simultaneously managing and learning (‘learning from implementation’). It is purposely conducted in a manner that explicitly increases knowledge and reduces uncertainty (Rist et al., 2013), and is a key aspect of managing any marine area (Schultz et al., 2015). Adaptive management enables managers to be flexible and to expect and respond to the unexpected.

Effectiveness and efficiency

These two words are often used interchangeably, but both are necessary for effective governance and a well-functioning workplace. Effectiveness is the ability to produce a better result, deliver more value or achieve a better outcome. Efficiency is the ability to produce an intended outcome resulting from the optimal use of time, effort, and/or available resources. Drucker (2001) puts it simply, “Effectiveness is doing the right thing, while efficiency is doing things right”. Both assume an MPA practitioner is able to define what is the right outcome and what things need to be done. As with some other principles, effectiveness and efficiency may also potentially be in tension with public participation and consensus decision-making.

Wooll (2022) explains that increased effectiveness may occur in many ways:

● Being open to change (e.g., encourage flexibility in how things are done)

● Embracing collaboration and encouraging new ideas (listen to input from everyone on the team, as everyone has something to offer)

● Relinquishing control and trusting your colleagues to do what they need to do

● Looking at the big picture, not just the problem at hand.

Accountability

Ruhanen et al. (2010) ranked accountability as the #1 aspect of governance (see Table 1). Accountability includes ensuring that tasks and objectives are completed on time and funds are spent appropriately (Dearden et al., 2005). In an MPA, this relates to who holds the main decision-making authority for the area? Who is responsible and can be held accountable for the decisions and outcomes? Sometimes performance standards are used to ensure accountability, but an over-application of such mechanisms can detract from getting on with ‘the real work’ of MPA management. A more effective way is when all those involved in the key aspects of MPA management take specific responsibility for their actions and behaviour, and demonstrate their performance by their actions and outcomes. Lockwood (2010) explains accountability requires:

● the allocation of responsibilities to those institutional levels that best match the scale of issues and values being addressed;

● the allocation and acceptance of responsibility for decisions and actions, through clear plans and activities; and

● identifying the extent to which a governing body is answerable to its constituency and also answerable to ‘higher-level’ authorities.

Decision-makers in government are accountable to the public, as well as to the relevant stakeholders. It is important that this accountability is linked to appropriate reports clearly justifying performance and outcomes. The stakeholders therefore need to know what is at stake in decision-making, who is responsible for what; how their performance can be evaluated, and how those responsible can be made accountable.

NGOs can also play significant roles holding government agencies accountable for their actions (or lack of action) in marine conservation or in a specific MPA. However, unlike governments, NGOs are not elected or dependent upon the support of national citizens, and therefore are less accountable for the results of their actions. NGOs may also inadvertently have negative impacts by “…overstepping their roles, absorbing all the available resources or centralising upon themselves all technical issues, thereby disempowering the local actors… “ (Borrini-Feyerabend and Hill, 2015, p. 138); this is a particular concern in developing countries.

Transparency

Transparency in governance means an organisation facilitates the availability of information, enabling others to see and understand how the organisation operates in a publicly available, accurate, and timely way. Transparency is becoming an increasingly important element of governance at all levels of society, from global to local (Mitchell, 2011). Sufficient information needs to be available to anyone concerned to understand and monitor the processes, budgets, laws and decisions of an organisation.

Freedom of information (FOI) regulations differ between countries but generally require government agencies to publish a broad range of material and give a citizen the right to request access to government-held information. There may be some exceptions for FOI including private information (e.g., personal records), ‘commercial-in-confidence’ material, high-level government decisions (e.g., ‘Cabinet in confidence’ documents) or vexatious requests.

Equity

Equity relates to fairness in the distribution of benefits and costs associated with conservation (Jones et al., 2013). Österblom et al. (2020) maintain that access to ocean resources and sectors is rarely equitably distributed; many of the benefits are accumulated by a few, while most harms are borne by the most vulnerable. Most ocean policies are largely equity-blind, poorly implemented and fail to address inequity. A high level of perceived inequity can undermine resource users’ willingness to comply with conservation rules or participate in MPA processes, thus limiting the effectiveness of governance incentives and exacerbating the likelihood of over-exploitation (Jones et al., 2013).

Bennet (2019; p. 10) defines environmental justice and equity as ‘… the degree to which stakeholder rights, knowledge and values are taken into account ….in decision making, and distributional to the allocation of benefits (goods) and burdens (bads) of resource-based developments and environmental laws, policies, and management actions’. Equity also relates to sustainable use that meets the needs of the current generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs (WCED, 1987) — these include basic human needs, economic needs, environmental needs, and subjective well-being. Climate change will worsen the challenges of fairness and equity faced by developing countries, and regions and communities reliant on marine livelihoods (Weiss, 2008). Climate change and the continuing depletion of natural resources will also be significant burdens for future generations. Addressing these inequities requires strong leadership, inclusive governance and long-term planning as equity is integral to a sustainable ocean economy.

Bennett et al. (2021) outline a variety of ways that social equity may be better integrated into marine conservation policy and practice. They advocate the need to acknowledge and respect diverse peoples and perspectives; the fair distribution of impacts through maximizing benefits and minimizing burdens; fostering participation in decision-making; championing and supporting local involvement; ensuring benefits to both nature and people; and addressing contextual barriers to and structural roots of inequity in conservation. However, they also recognise these need to be based on the social, economic, cultural and political realities of each context.

Rule of law

At its most basic level, the rule of law is the concept that all persons and organisations (including the government) are subject to, and accountable to, the law, and that the law is readily accessible and therefore widely known. The principles1 of the rule of law include: fairness (governments and the courts must follow the law); rationality (laws must be clear and able to be followed); predictability (the outcome for breaking the law must be clear); consistency (the law is applied to all in the same way, and no retrospective laws) and impartiality (an independent decision maker ensures legal processes are fair and just).

Specific examples of the nine principles of governance from the Great Barrier Reef

As the largest coral reef ecosystem on the planet, the GBR has undeniable scientific, cultural and conservation significance. It is arguably one of the richest and most complex natural ecosystems globally (Day, 2016), and the GBR Marine Park is one of the better known MPAs in the world.

The governance of such a large and iconic area is complex due to its size and the overlapping federal and state (Queensland) jurisdictions. In addition to the involvement of two governments, management of the GBR also involves Traditional Owners, industry, researchers, community organizations, local government, and individuals. Governance is therefore subject to diverse influences that transcend jurisdictional boundaries. Managing the GBR therefore requires balancing reasonable human use with the maintenance of the area’s natural and cultural integrity.

As the GBR has been adaptively managed for over 45 years, the governance approach has evolved (e.g., Olsson et al., 2008; Day and Dobbs, 2013; Evans et al., 2014). Morrison (2017) summarises many of the issues influencing GBR governance over the decades, showing that the pinnacle of success as marine managers occurred in 2004 when the GBR-wide rezoning was implemented. Morrison (2017) also outlines some of major influences on GBR governance from 2006 onwards contributing to a decline in management effectiveness; these influences include a reduction in agency independence, budget fluctuations; increased attention from the UNESCO World Heritage Committee, legislative changes and repeals of some policy positions. At the same time, external pressures have also increased including increasing impacts of climate changes and declining water quality.

Outlined below are specific examples (both good and bad) from the GBR against each of the nine principles of governance. Examples of some of the more formal governance arrangements in the GBR are provided in the Supplementary Information. This includes various committees and agreements that have been specifically developed to assist management and coordination in the GBR (this information is too detailed for the main paper but provides an overview of some of the key components of governance in a large and complex MPA like the GBR).

Participation in the GBR

A good example of participation in the GBR was the comprehensive public engagement process associated with the major rezoning program between 1999-2004. The level of effective public engagement was one of four key elements that significantly influenced the rezoning outcome (Day, 2020). This occurred after it was recognized that effective engagement was essential to understand community concerns, and a wide range of engagement techniques were applied to ensure community involvement. This included very high levels of public participation that went way beyond the requirements of the legislation (e.g., 35,000 written public submissions contributed to major changes between the original zoning plan, the draft plan and the final zoning plan, and attest to the participation being more than just token consultation (Day, 2017)).

A wide range of engagement techniques were adopted enabling anyone who was interested to participate constructively (e.g., the community information sessions were shown to be far more effective than public meetings) and the very high levels of participation (including information tailored for specific stakeholders) contributed to the successful outcome of the entire program. Day (2017) provides a detailed analysis of 25 elements of effective public participation programs across all phases of planning and implementation. The effective ongoing engagement of the community through Local Marine Advisory Committees (LMACs) is another example of successful public participation in the GBR.

Consensus orientation in the GBR

In the GBR, consensus operates at many levels of generality and specificity. There is widespread consensus that the GBR is important, with many industries depending upon its health, and accepting that it is worth protecting. It is also one of the most iconic tourist destinations in Australia and that leads to widespread levels of socio-political support. More specific decisions in the GBR, however, lead to a greater fragmentation of interests and less ability to achieve true consensus, shifting governance to acceptable compromises.

A good example of a specific consensus was the comprehensive 2017 Scientific Consensus Statement (Waterhouse et al., 2017) prepared by a multidisciplinary panel of scientists with expertise in GBR water quality science and management. The panel reviewed and synthesised the significant advances in scientific knowledge from the 2013 Scientific Consensus Statement, drawing upon the regional water quality improvement plans, specific research and monitoring results as well as relevant science published to date on the ecological processes operating in the GBR.

An example of a fragmentation of interests and no clear consensus, was the process to revise the zoning for the entire GBR Marine Park. When the GBR Zoning Plan was finalised in 2004, it included various compromises that left virtually all sectors feeling a little disappointed. There was widespread acceptance that the extent of public engagement and participation had led to significant changes during the planning process (Day, 2017), but no single sector got exactly what they wanted. Any expectation that a comprehensive public engagement process would be either conflict-free or lead to total consensus was unrealistic; there is no easy way of creating a conflict-free consultative mechanism or achieving total consensus when planning an area of such complexity as the GBR.

Strategic vision in the GBR

The overall management approach for the GBR is ecosystem-based management (EBM), including management influence over a wider context than just the federal Marine Park. This vision has existed for decades; the 25-year vision in the 1994 GBR Strategic Plan (GBRMPA, 1994) provided a comprehensive picture of what the GBR should be like, highlighting some key values that were fundamental for the GBR, and outlining various areas where changes were required. In contrast, a poor example of a strategic vision is the one in the current Reef 2050 Plan which simply states: The Great Barrier Reef is sustained as a living natural and cultural wonder of the world (Commonwealth of Australia, 2021).

The comprehensive rezoning of the GBR between 1999-2004 had the broad objective to protect the full range of biodiversity across the entire area by increasing the extent no-take zones, ensuring they included examples of all habitat types. This was effectively a strategic vision for a specific program, but it had far wider implications for the entire GBR. Using a range of public engagement methods, this objective became widely known with a high level of public understanding of the GBR being an interconnected ecosystem, the need for increased protection, and the fact there was a systematic planning process in which everyone could be involved.

A previous CEO of the agency responsible for managing the GBR demonstrated that a well-defined strategic vision is not always an essential prerequisite for a new leader. Numerous interviewees in Day (2020) were highly praiseworthy of that particular CEO (who sadly is now deceased); but one said “…she didn’t necessarily have a vision to start, but she knew a good vision. She was very good at building on other people’s visions … and once she owned a vision, she really owned it”. Another interviewee said “… [the CEO] grew to have a vision and a passion for the Reef. I don’t think she started that way … but it certainly grew in her…”.

Responsiveness in the GBR

There is well developed and integrated management for all relevant federal and state agencies in the GBR, enabling an immediate and effective management response if required (e.g., responding to an incident like a ship grounding or an oil spill).

A widely acclaimed example of a longer-term but widespread response in the GBR was the comprehensive rezoning that occurred following the realisation there was a need to increase protection of the range of biodiversity that existed the GBR. The level of effective engagement outlined above (Participation in the GBR) and the subsequent changes to the draft zoning plan following the public submissions and other sectoral inputs in 2003 is an example of the effective and responsive planning process. The resulting zoning network led to an increase in the extent of no-take zones from 4.6% of the GBR to 33.3% (or 114,530 km2). More importantly, the new network protected representative example of all 70 bioregions identified within the GBR while minimising the impacts on all users, including fishers.

The grounding of the ship Shen Neng 1 on a remote reef in the GBR in April 2010 provides both good and poor examples of responsiveness. The initial incident response was relatively well handled, with the ship removed from the reef and three assessments undertaken of the impact area within a month. A longer-term response resulted in the vessel tracking system known as REEFVTS being subsequently extended to apply throughout the entire length of the GBR (for an example of a poor response after the grounding, see below (Accountability in the GBR) which outlines the ineffectual accountability resulting from an unforeseen combination of events).

Effectiveness and efficiency in the GBR

The comprehensive intergovernmental arrangements, both formal and informal, between the federal government and the state government provide for effective ecosystem-level management for all waters in the GBR, irrespective of the jurisdiction (Commonwealth of Australia and State of Queensland, 2015). The fact there is relatively stable governance at all levels of government and many complementary management tools also assists in effective co-management.

One specific and detailed example of integrating efficiency and effectiveness in the GBR was the automated process used to generate the 150 pages of detailed legal boundary descriptions covering every zone boundary in the 2003 Zoning Plan. This needed to occur with a high degree of accuracy and, as explained by Lewis et al. (2003, p. 7), “… there is no tolerance for error because the boundary description, not the [zoning] map, is the legal definition of each boundary … we automated the process and generated a boundary description schedule directly from the GIS coverage…”.

Day (2020) highlights other innovative and complex aspects of the rezoning process that were both effective and efficient (e.g., the legal complexities of moving from the old zoning plan to the new plan while ensuring all related legal instruments such as ongoing permits, were seamlessly transitioned). Another example of an effective process is the coordination of a wide range of federal and state enforcement agencies to produce a comprehensive and targeted compliance and surveillance program across the GBR. Various Australian and Queensland government agencies including the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority, Queensland Parks and Wildlife Service, Queensland Boating and Fisheries Patrol, Queensland Water Police and Maritime Border Command, are all coordinated by a central unit – the Field Management Compliance Unit, to ensure an efficient and effective compliance program.

Accountability in the GBR

High levels of accountability are facilitated by the substantial expertise within the managing agencies, including long-standing staff with considerable corporate knowledge. A highly regarded example of long-term accountability is the GBR Outlook Report prepared every five years to fulfill specific legislative requirements2. The report is prepared by the managing agency (the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority), is accountable to the Minister, the federal parliament and the people of Australia (GBRMPA, 2019) and is widely acknowledged as being ‘best practice’ for systematic and transparent reporting.

An admirable short-term example of accountability and teamwork in the GBR was shown by the extremely high level of commitment by staff of the managing agency between August and December 2003. The monumental tasks included assessing 21, 000 written public submissions, amending the draft plan in the light of those submissions, and finalising the Zoning Plan and all the accompanying documentation for submission to Parliament (including the zone boundary descriptions, new legal provisions, and a Regulatory Impact Statement), all within four months. This was because of a ‘political window’ (unbeknown to staff but due to a forthcoming election) that meant that years of effort could have been wasted if the necessary documentation had not been submitted in time. GBRMPA staff worked incredibly hard, and all essential documentation was finalised and tabled in the Parliament by the Minister by early December 2003, within the required timeframe.

In contrast, an example of ineffectual accountability at various levels (political, legal, organizational) collectively resulted in delays in the remediation of a major ship grounding site after the Shen Neng 1 went aground in a remote part of the GBR in 2010. A lamentable combination of political uncertainties, international political differences, legal disputes, remoteness, logistical delays, operational difficulties and various personnel, have led to delays in the clean-up of the area for more than a decade. The consequence of this slow response is that some of the antifoulant paints that initially impacted Douglas Shoal may never be recovered, having subsequently been eroded over the years and dispersed by the very strong tidal currents over a broader area.

Transparency in the GBR

One example of transparency in the GBR is the systematic planning process specified in the legislation including the requirement to formally engage the public on at least two occasions during the preparation of a statutory zoning plan. Another is the detailed guidance that is publicly available regarding what activities require a permit to operate in the GBR, how permit assessments are undertaken, and how decisions are made about the acceptable level of environmental impact.

One of the most transparent aspects of current GBR-management is the 5-yearly Outlook Report introduced above (Accountability in the GBR). The assessment grades at the end of each chapter, along with the trend arrows since the last report and the assessment of the level of confidence for each value are all extremely clear, functional and informative. The eight initial chapters in the Outlook Report document the evidence in a systematic way that is then integrated to produce the final long-term outlook for the Region’s values (GBRMPA, 2019).

A poor example of transparency was the federal Government’s decision in 2018 to grant AUD$444 million to a small charity (the GBR Foundation) for the Foundation to allocate to environmental projects in the GBR. The federal auditor-general subsequently found the responsible federal department did not comply with the procedures designed to ensure transparency and value for money, resulting in “…non-compliance with elements of the grants administration framework” (ANAO, 2019).

Equity in the GBR

For thousands of years, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have used the coastal waters, islands and reefs for traditional resources and customary/spiritual practices in the area that today is known as the GBR. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are therefore recognised as the Traditional Owners of the GBR, and today there are approximately 70 Traditional Owner clan groups whose land and sea country (‘country’) includes the GBR Marine Park.

GBRMPA’s stated aims include establishing effective and meaningful partnerships with Traditional Owners to protect Indigenous heritage values, conserve biodiversity and enhance the resilience of the GBR (GBRMPA, nd). Aspects of governance of the GBR which contribute to these aims include Indigenous membership on the Marine Park Authority Board, an Indigenous Reef Advisory Committee (see Supplementary Information), an Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Heritage Strategy for the Marine Park, a major program of Traditional Use of Marine Resources Agreements with specific Traditional Owner groups, funding for Indigenous Rangers and Indigenous compliance training, GBRMPA’s Reflect Reconciliation Action Plan, and Sea Country values mapping.

During the GBR-rezoning the public engagement process was comprehensive, and overall was considered both equitable and effective (Day, 2020). Among the reasons were the ongoing public engagement throughout the program, the willingness of community members and stakeholders to engage on matters that are important to them, and on the commitment of the GBRMPA staff to the wide range of engagement methods that were used with rightsholders and stakeholders. In hindsight, some improvements in engagement could have been made, particularly given what worked, and what did not work effectively for Traditional Owners and other Indigenous people34. This was primarily a mismatch of the timeframes considered adequate for public engagement and the timing some Indigenous groups considered appropriate; lessons have therefore been learned and these need to be applied in future engagement programs.

Gooch et al. (2018) consider that the GBR-dependent industries (e.g., tourism, fisheries, research) generally have comparable equity with other industries because of the rezoning. Marshall and Pert (2017) also suggest that GBR management has considered future generations by the statutory protection of one-third of the entire GBR as no-take zones, effectively providing ‘insurance’ for the future.

Rule of Law in the GBR

The sound governance/legislative framework specific to the GBR, including complementary state and federal legislation, is fully listed on the GBRMPA webpages; this shows the range of applicable national and state legislation, along with a number of relevant international conventions. One good example in the GBR legislation is the primary objective developed specifically for the Marine Park, which today provides for ‘… the long-term protection and conservation of the environment, biodiversity and heritage values of the GBR Region’. There are also subordinate objectives, but the Act stipulates they must be consistent with the primary objective.

The Zoning Plan and the Regulations are both statutory instruments that have the force of law. When both were recently amended, they needed to be legally compliant and accord with other legislation before they could be passed by both federal Houses of Parliament. The GBRMPA legal team also worked with the Commonwealth Director of Public Prosecutions to ensure the legislation’s enforceability.

The comprehensive compliance and surveillance program outlined above (Accountability in the GBR) includes a range of surveillance operations using vessels, aircraft, drones, and land-based activities occurring night and day, remote vessel tracking, as well as compiling intelligence from a wide range of sources. The aim is to achieve high levels of voluntary compliance, while also maintaining a strong enforcement approach to deter and detect illegal activity. Penalties for offences against Marine Park and other environmental legislation are substantial4 and reflect the environmental value of the GBR and the significant impact that illegal activities can cause.

Another example of how the rule of law is consistently and impartially applied in the GBR is the online feature associated with the Environmental Management Charge (EMC). The EMC is a legal charge associated with most commercial activities, including tourism operations, non-tourist charter operations and facilities, operated under a permit granted by the GBRMPA. EMC Online is a user-friendly way for Marine Park users to manage their EMC obligations (e.g., allowing online remittance of the EMC), while enabling users to customise the system to suit their operations. The penalties for not adhering to the EMC legislation are such that the level of compliance is extremely high.

Applying the principles in your MPA

The nine principles outlined above should be applicable to all MPAs, but how they are applied will differ depending upon the objectives of specific MPAs, varying socio-political expectations, and the social–ecological context in which the MPA exists. As demonstrated by Gaymer et al. (2014), one size does not fit all. Consequently, the emphasis given to the different principles of governance and how they are applied will vary in dissimilar settings because each society values outcomes and priorities differently (Graham et al., 2003).

Gaymer et al. (2014, p. 138) advocate for “…a good balance and integration between bottom-up and top-down approaches…”. Contemporary modes of marine governance now range from a more traditional approach (driven from the top by a government authority), through to a wide variety of partnerships, co-management and informal arrangements involving multiple agencies, NGOs, communities, and individuals. Paraphrasing Lockwood (2010), “…this emerging polycentric regime offers both promises and pitfalls…. [It] has the potential to deliver a more just system of protected areas … [and] more effective management may result from enhanced cooperation and mobilization of local and indigenous communities”. There are, however, significant challenges to achieving the right balance, and it is important to recognise that many of the principles of governance are likely to have multiple applications in a specific MPA (as shown by the multiple examples of each principle from the GBR). Most of the principles should also be enduring and ongoing in their application (e.g., the legal frameworks that are part of the rule of law need to be ongoing, as is the need for accountability and transparency). However, some applications of the principles may only occur for a specified period (e.g., a defined period of public participation as part of a planning program, or how responsive an organisation is to specific issue or incident, or if an organisation is undergoing transformational change, a new strategic vision may be required).

For some MPAs, good governance needs to occur utilising various formal arrangements such as those shown in Supplementary Information for the GBR; these include:

● consideration of international environmental conventions at the global level;

● coordination between federal and State/provincial governments at the national and regional level (i.e., vertical integration)

● coordination within federal and State/provincial governments (i.e., horizontal integration)

● active Indigenous involvement;

● community and NGO-driven participation at the local level; and.

● coordinated research and monitoring, prioritised to address agreed priorities.

One useful analogy is to look at the nine principles as being part of an interlaced or woven lattice, with each application of the principle corresponding to one strand in the lattice, remembering there are likely to be multiple applications (i.e., multiple strands) of each principle. Collectively the lattice is stronger than any individual strand, and together all principles contribute to the totality of governance. At certain times, some strands (principles) will be at the front because they are a current priority, while other principles will be less prominent and therefore sit behind. Being a woven lattice, this varies, so at other times, the principles that were at the back will become more prominent (i.e., more current and relevant at that point in time) while other principles may become less relevant.

The planning and ongoing management of an MPA and its values may be the responsibility of a single agency or organisation (whether it is a federal, state or a provincial authority, or at the community level) or be undertaken by a collective of organisations. Most MPAs exist, however, within a context where decisions that affect the MPA may also be made by other agencies and authorities, other jurisdictions and other interested parties, all of which have the potential to influence the ecological, economic and social aspects of the MPA. These all need to be considered as part of the overall governance of the area. Furthermore, where First Nations are involved, effective governance also requires a balanced approach that maintains and incorporates the cultural values, customs and knowledge of First Nation peoples living within and/or adjacent to the MPA. The Indigenous Advisory Committee established in the GBR, and outlined in the Supplementary Information, is one example how this may be addressed.

Finally, and importantly, undertaking all nine principles shown in Table 1 assumes that those responsible for MPA management have sufficient discretion, resources, and authority to ensure most, if not all of these, happen. The reality in most MPAs, however, is that resource constraints and the managerial and legal context are such that it is not easy to implement and achieve ‘best-practice’ across all nine principles. This paper provides an outline of each principle in a way that all those involved in MPA management (including relevant decision-makers, the MPA agency(ies), the MPA managers and some parts of the community), having made a frank assessment of how their MPA is currently governed, understand each of the key aspects sufficiently well to enable them to incrementally improve their governance.

Conclusion

In most MPAs, there are wide-ranging requirements, incorporating a diverse range of rights-holders, stakeholders, obligations and knowledge. However, the associated actions and decisions will be enhanced and sustained if they are effectively managed through a sound governance framework. This should include:

● a clear and agreed set of arrangements addressing all nine principles of good governance as outlined in this paper;

● the unambiguous prioritisation of any management actions, strategies or procedures;

● an agreed set of arrangements for effective partnerships at all relevant levels enabling the real and transparent sharing of decision-making powers;

● an active role for Indigenous and local communities in MPA management;

● a willingness of all relevant players to adhere to the principles of good governance and to work together toward an agreed goal or a prioritised list of objectives; and

● a means to mediate differing interests to reach a broad consensus on what is in the best interests of all parties and, where possible, on policies and procedures.

The concept of adaptive governance is also an important aspect of ongoing MPA management; as Schultz et al. (2015, p.7373) conclude, “…adaptive governance will always involve a continuous learning process, nurturing of trust, reflection of procedures and structures, and developing collaboration toward common goals. These initiatives are continuously subject to new challenges, whether political, environmental, and economic…”

Finally, while it may be useful to learn from the experience gained in long-standing MPAs like the GBR, it is important to recognise that other MPAs, irrespective of where they occur around the world, will have differing political, economic, social, cultural and managerial contexts and hence are likely to require a different management approach and objectives when compared to the GBR. Every MPA is unique, so it is therefore essential to consider the specific context and objectives of a particular MPA when considering what lessons from elsewhere might apply.

Author contributions

JD is the sole author of this paper.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to the Topic Editors for the Special Edition on Marine Governance in the Ocean Decade for the invitation to prepare this paper and their comments on my initial submission. Thanks also to editor and two reviewers whose comments and suggestions contributed immensely to improving this paper; lastly thanks to Di Tarte for providing comments on the Supplementary Material.

Conflict of interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organization, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Supplementary material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fmars.2022.972228/full#supplementary-material

Footnotes

- ^ See https://www.ruleoflaw.org.au/principles/

- ^ The Outlook Report is required under legislation to include nine specific assessments covering biodiversity, ecosystem health, heritage values, commercial and non-commercial use, factors influencing the Reef’s values, existing protection and management, resilience, risks to the values and the long-term outlook.

- ^ In addition to the approximately 70 Traditional Owner clan groups whose Country is recognised within the GBR region, there are also other Indigenous people (e.g., Aboriginals from elsewhere and Pacific Islanders) living adjacent to the GBR, but their traditional lands and seas are not within the GBR.

- ^ One example of the penalties - fishing in a no-take zone can be addressed by an infringement notice of 10 penalty units (currently equivalent to AUD$2,220), but if prosecuted in court, the possible maximum penalty is 1000 penalty units (=AUD$222,000).

References

ANAO (Australian National Audit Office) (2019). Award of a $443.3 million grant to the Great Barrier Reef foundation - department of environment and energy. performance audit, auditor-general report No.22 2018–19 (Commonwealth of Australia). Available at: https://www.anao.gov.au/work/performance-audit/award-4433-million-grant-to-the-great-barrier-reef-foundation.

Appelstrand M. (2002). Participation and societal values: the challenge for lawmakers and policy practitioners. For. Policy Economics 4 (4), 281–290. doi: 10.1016/S1389-9341(02)00070-9

Arnstein S. R. (1969). A ladder of citizen participation. J. Am. Plann. Assoc. 35 (4), 216–224. doi: 10.1080/01944366908977225

Bäckstrand K. (2003). Civic science for sustainability: Reframing the role of experts, policymakers and Citizens in environmental governance. Global Environmental Politics 3 (4), 24–41. doi: 10.1162/152638003322757916

Bennett N. J. (2019). In political seas: Engaging with political ecology in the ocean and coastal environment. Coast. Manage. 47 (1), 67–87. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2019.1540905

Bennett N. J., Dearden P. (2014). From measuring outcomes to providing inputs: Governance, management, and local development for more effective marine protected areas. Mar. Policy 50, 96–110. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.05.005

Bennett N. J., Di Franco A., Calò A., Nethery E., Niccolini F., Milazzo M., et al. (2019). Local support for conservation is associated with perceptions of good governance, social impacts, and ecological effectiveness. Conserv. Lett. 12 (4), e12640. doi: 10.1111/conl.12640

Bennett N. J., Katz L., Yadao-Evans W., Ahmadia G. N., Atkinson S., Ban N. C., et al. (2021). Advancing social equity in and through marine conservation. Front. Mar. Sci. 994. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.711538

Bennett N. J., Satterfield T. (2018). Environmental governance: A practical framework to guide design, evaluation, and analysis. Conserv. Lett. 11 (6), 12600. doi: 10.1111/conl.12600

Birnbaum S., Bodin Ö., Sandström A. (2015). Tracing the sources of legitimacy: The impact of deliberation in participatory natural resource management. Policy Sci. 48 (4), 443–461. doi: 10.1007/s11077-015-9230-0

Borrini-Feyerabend G., Dudley N., Jaeger T., Lassen B., Pathak Broome N., Phillips A., et al. (2013). Governance of protected areas: From understanding to action. Best Practice Protected Area Guidelines Series No. 20 (Gland, Switzerland: IUCN), 124pp.

Borrini-Feyerabend G., Hill R. (2015). “‘Governance for the conservation of nature’,” in Protected Area Governance and Management. Eds. Worboys G. L., Lockwood M., Kothari A., Feary S., Pulsford I. (ANU Press: Canberra), 169–206.

Bown N., Gray T., Stead S. M. (2013). “Contested forms of governance in marine protected areas,” in A study of co-management and adaptive co-management (Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge).

Brueckner-Irwin I., Armitage D., Courtenay S. (2019). Applying a social-ecological well-being approach to enhance opportunities for marine protected area governance. Ecol. Soc. 24 (3), 7. doi: 10.5751/ES-10995-240307

Christie P., White A. T. (2007). Best practices for improved governance of coral reef marine protected areas. Coral Reefs 26 (4), 1047–1056. doi: 10.1007/s00338-007-0235-9

Commonwealth of Australia (2021). Reef 2050 long-term sustainability plan 2021–2025 (Australia: Department of Agriculture, Water and the Environment). Available at: https://www.awe.gov.au/sites/default/files/documents/reef-2050-long-term-sustainability-plan-2021-2025.pdf.

Commonwealth of Australia and State of Queensland (2015) Great Barrier Reef Intergovernmental Agreement. Available at: http://www.environment.gov.au/system/files/pages/7a85531d-9086-4c22-bdca-282491321e46/files/gbr-iga-2015.pdf.

Covey S. R. (1991). The seven habits of highly effective people (Provo, UT: Covey Leadership Center).

Day J. C. (2016). “The Great Barrier Reef Marine Park – the grandfather of modern MPAs,” in Big, Bold and Blue: Lessons from Australia’s marine protected areas. Eds. Fitzsimmons J., Wescott G. (Victoria, Australia: CSIRO Publishing), 65–97. Chapter 5.

Day J. C. (2017). Effective public participation is fundamental for marine conservation–lessons from a large-scale MPA. Coast. Manage. 45 (6), 470–486. doi: 10.1080/08920753.2017.1373452

Day J. C. (2020). Ensuring effective and transformative policy reform: lessons from rezoning australia's Great Barrier Reef 1999-2004. (Australia: Doctoral dissertation, ResearchOnline@JCU, James Cook University). Available at: https://researchonline.jcu.edu.au/67706/.

Day J. C., Dobbs K. (2013). Effective governance of a large and complex cross-jurisdictional marine protected area: Australia's Great Barrier Reef. Mar. Policy 41, 4–24. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.12.020

Dearden P., Bennett M., Johnston J. (2005). ‘Trends in global protected area governance 1992– 2002’. Environ. Manage. 36 (1), 89–100. doi: 10.1007/s00267-004-0131-9

Dehens L. A., Fanning L. M. (2018). What counts in making marine protected areas (MPAs) count? The role of legitimacy in MPA success in Canada. Ecol. Indic. 86, 45–57. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolind.2017.12.026

Drucker P. F. (2001). “The essential Drucker: Selections from the management works of Peter F. Drucker” (New York, NY: Harper Business).

Eagles P. J. F. (2009). Governance of recreation and tourism partnerships in parks and protected areas. J. Sustain. Tourism 17 (2), 231–248. doi: 10.1080/09669580802495725

Emerson K., Nabatchi T., Balogh S. (2012). An integrative framework for collaborative governance. J. Public Administration Res. Theory 22 (1), 1–29. doi: 10.1093/jopart/mur011

Evans L. S., Ban N. C., Schoon M., Nenadovic M. (2014). Keeping the ‘Great’ in the Great Barrier Reef: large-scale governance of the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park. Int. J. Commons 8 (2), 396–427. doi: 10.18352/ijc.405

Fanning L., Mahon R., McConney P., Angulo J., Burrows F., Chakalall B., et al. (2007). ‘A large marine ecosystem governance framework’. Mar. Policy 31, 434–443. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2007.01.003

Gaymer C. F., Stadel A. V., Ban N. C., Cárcamo P. F., Ierna J., Lieberknecht L. M. (2014). Merging top-down and bottom-up approaches in marine protected areas planning: Experiences from around the globe. Aquatic Conservation: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 24, 128–144. doi: 10.1002/aqc.2508

GBRMPA (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority). (nd). ‘Traditional owners’. Available at: https://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/our-partners/traditional-owners.

GBRMPA (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority) (1994). “The Great Barrier Reef: keeping it Great:,” in A 25-year strategic plan for the Great Barrier Reef world heritage area 1994-2019 (Townsville, Australia: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority). Available at: https://www.gbrmpa.gov.au/:data/assets/pdf_file/0004/5476/the-25-year-strategic-plan-1994.pdf.

GBRMPA (Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority) (2019). Great Barrier Reef Outlook Report 2019 (Townsville, Australia: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority). Available at: https://elibrary.gbrmpa.gov.au/jspui/handle/11017/3474.

Gooch M., Dale A., Marshall N., Vella K. (2018). “Assessing the human dimensions of the Great Barrier Reef: A Wet Tropics Region focus,” in National environmental science programme (Cairns: Reef and Rainforest Research Centre Limited), 61pp.

Graham J., Plumptre T. W., Amos B. (2003). Principles for good governance in the 21st century. Policy Brief No. 15 (Ottawa, Canada: Institute on governance). Available at: https://www.academia.edu/2463793/Principles_for_good_governance_in_the_21st_century.

Innes J., Booher E. (2007). Re-framing public participation: Strategies for the 21st century. Plann. Theory Pract. 5 (4), 419–436. doi: 10.1080/1464935042000293170

Johnston R. J., Gregory D., Pratt G., Watts M. (2000). The dictionary of human geography. 4th Edition (Oxford: Wiley-Blackwell).

Jones P. J. S. (2012). ‘Marine protected areas in the UK: Challenges in combining top-down and bottom-up approaches to governance’. Environ. Conserv. 39, 248–258. doi: 10.1017/S0376892912000136

Jones P. J. S. (2014). Governing Marine Protected Areas: Resilience through Diversity. (London: Earthscan Series, Routledge), 256 pp. doi: 10.4324/9780203126295

Jones P. J. S., De Santo E. M., Qiu W., Vestergaard O. (2013). Introduction: An empirical framework for deconstructing the realities of governing marine protected areas. Mar. Policy 41, 1–4. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2012.12.025

Jones P. J. S., Long S. D. (2021). Analysis and discussion of 28 recent marine protected area governance (MPAG) case studies: Challenges of decentralisation in the shadow of hierarchy. Mar. Policy 127, 104362. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104362

Jones P. J. S., Qiu W., De Santo E. M. (2011) Governing MPAs. In: Getting the balance right (UNEP). Available at: http://www.mpag.info (Accessed 12 March 2013).

Kotter J. P. (1995). “Leading change: Why transformation efforts fail,” in Harvard Business review (May–June 1995). (Boston, Mass: Harvard Business School Publishing). Available at: https://hbr.org/1995/05/leading-change-why-transformation-efforts-fail-2.

Lewis A., Slegers S., Lowe D., Muller L., Fernandes L., Day J. C. (2003). “Use of spatial analysis and GIS techniques to rezone the Great Barrier Reef Marine Park,” in Coastal GIS workshop, July 7-8, 2003 (Australia: University of Wollongong).

Lockwood M. (2010). Good governance for terrestrial protected areas: A framework, principles and performance outcomes. J. Environ. Manage. 91 (3), 754–766. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2009.10.005

Lockwood M., Davidson J., Curtis A., Stratford E., Griffith R. (2010). Governance principles for natural resource management. Soc. Natural Resour. 23 (10), 986–1001. doi: 10.1080/08941920802178214

Lundquist C. J., Granek E. F. (2005). Strategies for successful marine conservation: integrating socio-economic, political, and scientific factors. Conserv. Biol. 19 (6), 1771–1778. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2005.00279.x

Marshall N., Pert P. (2017). The social and economic long term monitoring program for the Great Barrier Reef (Townsville: Great Barrier Reef Marine Park Authority).

McCay B. J., Jones P. J. S. (2011). Marine protected areas and the governance of marine ecosystems and fisheries. Conserv. Biol. 25, 1130–1133. doi: 10.1111/j.1523-1739.2011.01771.x

Mitchell R. B. (2011). Transparency for governance: The mechanisms and effectiveness of disclosure-based and education-based transparency policies. Ecol. Economics 70 (11), 1882–1890. doi: 10.1016/j.ecolecon.2011.03.006

Morrison T. H. (2017). Evolving polycentric governance of the Great Barrier Reef. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 114 (15), E3013–E3021. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1620830114

Nanus B. (1992). Visionary Leadership: Creating a Compelling Sense of Direction for Your Organization (San Francisco, California: Jossey-Bass Inc.).

Olsson P., Folke C., Hughes T. P. (2008). Navigating the transition to ecosystem-based management of the Great Barrier Reef, Australia. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 105, 9489–9494. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706905105

Österblom H., Wabnitz C. C., Tladi D., Allison E., Arnaud-Haond S., Bebbington J., et al. (2020). Towards ocean equity (Washington, DC: World Resources Institute).

Petts J. (2006). Managing public engagement to optimize learning: Reflections from urban river restoration. Hum. Ecol. Rev. 13 (2), 172–181.

Petts J. (2008). Public engagement to build trust: false hopes? J. Risk Res. 11 (6), 821–835. doi: 10.1080/13669870701715592

Petts J., Leach B. (2000). “Evaluating methods for public participation: Literature review”. Technical Report E135 (Bristol, UK: Environment Agency R&D).

Reed M. S. (2008). Stakeholder participation for environmental management: A literature review. Biol. Conserv. 141 (10), 2417–2431. doi: 10.1016/j.biocon.2008.07.014

Rice J. (1985). “New ecosystems present new challenges,” in Marine parks and conservation; challenge and promise, vol. 1. (The National and Provincial Parks of Canada). Henderson Book Series No. 10.

Rist L., Campbell B. M., Frost P. (2013). Adaptive management: where are we now? Environ. Conserv. 40 (1), 5–18. doi: 10.1017/S0376892912000240

Rowe G., Frewer L. J. (2005). A typology of public engagement mechanisms. Sci. Technol. Hum. Values 30 (2), 251–290. doi: 10.1177/0162243904271724

Ruhanen L., Scott N., Ritchie B., Tkaczynski A. (2010). Governance: a review and synthesis of the literature. Tourism Rev. 65 (4), 4–16. doi: 10.1108/16605371011093836/full/pdf?title=governance-a-review-and-synthesis-of-the-literature

Schultz L., Folke C., Österblom H., Olsson P. (2015). Adaptive governance, ecosystem management, and natural capital. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 112 (24), 7369–7374. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1406493112

Stern P. C., Dietz T. (2008). Public participation in environmental assessment and decision making (Washington, DC: National Academies Press).

UNDP (United Nations Development Programme) (1997). “Governance for sustainable human development,” in A UNDP policy document (New York: United Nations Development Program). Available at: https://digitallibrary.un.org/record/492551?ln=en.

VAGO (Victorian Auditor-General’s Office) (2015). “Public participation in government decision-making,” in Better practice guide. (Melbourne: Victorian Auditor-General’s Office), 23 pp. http://www.audit.vic.gov.au

Waterhouse J., Schaffelke B., Bartley R., Eberhard R., Brodie J., Star M., et al. (2017). 2017 Scientific Consensus Statement. Land use impacts on Great Barrier Reef water quality and ecosystem condition. (Brisbane Australia: Queensland Government). Available at: https://www.reefplan.qld.gov.au/about/assets/2017-scientific-consensus-statement-summary.pdf.

WCED (World Commission on Environment and Development). (1987). Our Common Future. United Nations General Assembly, Annex to document A/42/427. https://www.are.admin.ch/are/en/home/media/publications/sustainable-development/brundtland-report.html.

Weiss T. G. (2000). Governance, good governance and global governance: Conceptual and actual challenges. Third World Q. 21 (5), 795–814. doi: 10.1080/713701075

Weiss E. B. (2008). Climate change, intergenerational equity, and international law (Washington DC: Georgetown University Law Faculty Publications), 1625. Available at: https://scholarship.law.georgetown.edu/facpub/1625.

Wooll M. (2022) Still chasing efficiency? find out why effectiveness is a better goal. online, BetterUp, 6th march 2022. Available at: https://www.betterup.com/blog/efficiency-vs-effectiveness#:~:text=Efficiency%20is%20the%20ability%20to,or%20achieves%20a%20better%20outcome.

Young O. R., Osherenko G., Ekstrom J., Crowder L. B., Ogden J., Wilson J. A., et al. (2007). Solving the crisis in ocean governance: place-based management of marine ecosystems. Environment: Sci. Policy Sustain. Dev. 49 (4), 20–32. doi: 10.3200/ENVT.49.4.20-33

Keywords: marine, marine protected area (MPA), governance, management, integration, planning

Citation: Day JC (2022) Key principles for effective marine governance, including lessons learned after decades of adaptive management in the Great Barrier Reef. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:972228. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.972228

Received: 18 June 2022; Accepted: 09 August 2022;

Published: 14 September 2022.

Edited by:

Catarina Frazão Santos, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Robin Kundis Craig, University of Southern California, United StatesMichael Kenneth Orbach, Duke University, United States

Copyright © 2022 Day. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Jon C. Day, am9uLmRheUBteS5qY3UuZWR1LmF1

Jon C. Day

Jon C. Day