95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

POLICY AND PRACTICE REVIEWS article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 20 July 2022

Sec. Marine Affairs and Policy

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.906566

This article is part of the Research Topic New Frontiers of Marine Governance in the Ocean Decade View all 12 articles

Since the Brexit happened in January 2020, it is likely to impact the United Kingdom (UK) and the whole of Europe in different ways. The UK and other European countries will revise their preferences concerning fisheries, ports access and governance, and bilateral diplomatic relationships with the countries alongside the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR). However, this is not an end to uncertainties, but the beginning to show the double-edged effects of Brexit. This paper focuses on the opportunities and challenges for Sino-UK as well as European Union (EU) relations arising from Brexit. The present study considers Brexit’s impact on the MSR countries, especially China, Pakistan, and India. It examines what Brexit means for the Sino-UK/EU relationship, politically, economically, and culturally. It concludes with the potential impacts of Brexit on Sino-UK/EU trade relations, maritime security, marine resources usage, the safety of navigation, port governance and cooperation, and suggests the appropriate strategies that can be put in place to capitalise on opportunities to reap benefits while mitigating the challenges.

●Since the Brexit happened in 2020, it is likely to impact the United Kingdom (UK) and the whole of Europe in different ways. The UK and other European countries will revise their preferences concerning fisheries, ports access and governance, and bilateral diplomatic relationships with the countries alongside the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road (MSR). However, this is not an end to uncertainties, but the beginning to show the double-edged effects of Brexit. This paper focuses on the opportunities and challenges for Sino-UK as well as European Union (EU) relations arising from Brexit in context with the port governance.

●The present study considers Brexit’s impact on the MSR countries, especially China, Pakistan, and India. It adopts qualitative means to examine what Brexit means for the Sino-UK/EU relationship, politically, economically, and culturally. It also provides an analysis of the impact of Brexit on maritime security, marine resources usage, the safety of navigation, port governance and coopertion.

●This study concludes with the potential impacts of Brexit on Sino-UK/EU trade relations, and suggests the appropriate strategies that can be put in place to capitalise on opportunities to reap benefits while mitigating the challenges.

●The present study is a unique study of its kind which not only highlights the challenges the world may face after the Brexit but also proposes some prospects in context with the trade and business opportunities with China through Indian Ocean Regions, particularly from the Gwadar port of Pakistan and engaging India simultaneously.

In 2015, China officially launched its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI); the goal is to muster new growth services at home as well as abroad. The twenty-first century MSR and the new ‘Silk Road Economic Belt’ are expected to connect China with countries in Southeast Asia, Central Asia, Europe and Africa (NDRC, 2015). Hitherto, 68 States have signed memorandums of understanding (MoUs) with China aiming to benefit from the BRI (Global Times, 2017; Chang, 2018). The UK was not among these States; nevertheless, numerous projects in trade, energy, finance, and transportation have been planned and enforced under the umbrella of the BRI. The British government claims to be a ‘natural partner’ of China and has consequently welcomed the BRI as a stimulus to intensify Sino-UK relations. For example, there are four BRI projects in the UK, which are the Yiwu-London freight train route, the Hinkley nuclear power plant, the development of a new business district on the grounds of the London Royal Albert Dock, and the use of the City of London as a top-tier financial centre for financing BRI projects (Heiduk, 2018). However, these projects will have reverberations of Brexit, as the UK will lose its place as an economic, social and cultural centre of the EU. Further, the Chinese administration will also have to rethink about considering London as a financial centre or select one more destination in the EU for financing BRI projects in the EU. Currently, China faces a dichotomy as it has to successfully embed a plan of global cooperation and connectivity in a country that wants to carve a new path for itself by distancing from the EU and European Economic Area.

It is an admitted fact that with around 80% of the global trade volume and over 70% of global value trade at sea, maritime transport, including container shipping, is of fundamental importance for international trade and the global economy (Premti, 2016). Therefore, the maritime industry is also significant for Britain; it contributes to the UK economy for around £ 132 billion a year (Baker, 2019) which represents around 8.1% of the gross value (Stebbings et al., 2020), and secures around 240,000 jobs (Power et al., 2016). Also, on the Asia-Northern Europe routes, 15 out of 17 maritime shipping loops create a British port (John Goods, 2020), which makes it more significant for UK’s economy.

In the post-Brexit period, the UK will no longer be a part of the EU and will also lose its preferential status to 27 States that it enjoys under the EU (Her Majesty’s Government, 2016). Consequently, the UK government will negotiate trade agreements with Asian exporting States such as China. It may then also be able to devise new legislation and choice to make collaborations with other States along with BRI that suits explicitly to the UK (Braakman, 2017). Over the past 25 years, the value of goods traded in and out of UK ports has steadily increased. In 2017, exports and imports of goods to the UK in a total of £822 billion (ONS-UK, 2017). Not all of this will have passed through seaports; however, around 70% of goods transported into and out of the UK go through a seaport (MDS Transmodal, 2016). There are about 50 seaports, and they have been completed over the years and have become increasingly efficient. The main reason for the drop in the UK’s share of trade in the EU is that the growth of the EU’s gross domestic product (GDP) during this period was much weaker than elsewhere, especially when compared to China, India and the US. Considering exports and imports of goods to the UK as a relevant measure, trade with China has grown at an average annual rate of 15.6% over the past 15 years, with India 8.6% in a year and with the US of 3.8% a year (Taylor, 2019).

The UK approached China to promote maritime relations, and Brexit was finalised on 31 January 2020, which has led to the disintegration of its unity with the EU (WMN, 2017). Consequently, UK shipping has launched a trade mission to China to enhance the country’s investment potentials. The UK’s maritime and the Department of International Trade (DIT) will lead such negotiations with China. It could help the UK promote it as a global maritime centre and provide a comprehensive package for global maritime activities. It is pertinent to mention here that the 50 major seaports of the UK represent a successful and competitive private sector industry across the world (Taylor, 2019).

There are appropriate indications that China will adopt its BRI strategy to the UK for a number of reasons. Firstly, the UK will likely lose its preferred position for entry into EU markets. Further, unchanged access to the EU (27 States) is crucial for the Chinese economy, especially given the slowdown in growth rates across the world. In the post-Brexit period, China’s BRI strategy for the EU could lead to increasingly rapid infrastructure investments in Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), which could encourage Chinese corporations to move production to this region. Subsequently, Sino-UK trade can be diverted from land transport to passage into the Arctic Sea (Heiduk, 2018). Secondly, BRI investments in the UK energy sector have not yet been reduced. In any case, China must demonstrate how its new nuclear power plant works to obtain orders in other States. This could lead to political negotiation procedures in the context of Sino-UK commercial and investment agreements. Thirdly, London is expected to lose some of its attractiveness as a top-notch financial centre (Fairhead, 2018), creating a need for mega-business strategies such as BRI.

It can be expected that adjustments of activities concerning Chinese BRI in the UK will also lead to a change in various similar activities in the EU. This would be most evident in the commercial and transport infrastructure, and the CEE States could be the principal beneficiaries. China, although the BRI is a longstanding venture, may have to show success in its initial phase. It is a clear sign that China will adopt its BRI stratagem to the UK after Brexit, where it considers this important for its interests, but will maintain the status quo in all other cases. Besides, it is evident that the UK will look for novel associates after Brexit, and the Chinese BRI could offer a promising anchor. However, there are indications, as Kerry Brown (Brown, 2018) also mentioned, that the UK’s government has not convincingly communicated its vision of Brexit, which includes improving relations with China, without being a “Chinese vassal in EU or UK”.

While analysing the impact of Brexit on China-UK-EU relations, the role of India and Pakistan is also examined as they were an essential part of the Old MSR and presently sit at the main juncture of the New MSR. Further, China has also developed the ability to strategically engage in a constructive relationship with two or more quarrelling States by restraining itself from directly engaging in their disputes. This experience will help China to deal with changing dynamics of UK and EU relations effectively. Lastly, China needs to appease its neighbouring countries first before going global and engaging with distant countries as stability in the neighbouring region will help China fulfil its global ambitions. To this end, this study follows the qualitative method of content analysis and provides a critical analysis on the research gap concerning the port governance and new trade routes between China and EU/UK through the Gwadar Port and Indian Ocean. After providing an introduction and background, this study discusses the likely potential impacts of Brexit on the Sino-UK maritime economic relationship and Sino-EU post-Brexit relations in sections 2 and 3 subsequently. Whereas, section 4 presents an evaluation form the aspect of Indian port governance, and section 5 deals with the Sino-Pakistan port cooperation, which could connect China to the UK and EU with a shortest maritime route, followed by the way forward and clouding remarks in section 6.

Brexit is a by-product of a populous under the current narrative within the UK that it was compromising its sovereignty and national interests by staying in the EU. This belief was the reason the UK waited for 16 years before joining the EU, and this cynicism was also why the UK did not adopt the single currency policy launched in 1999. Nevertheless, two core issues that triggered Brexit were that: Firstly, the growing nationalism and the belief that immigrants were taking up their jobs, and the UK had enough clout to develop its economic relations. Secondly, scepticism and disbelief on the administrative system in Brussels and its ability to face global challenges in the wake of increasing complexity in the international world order. Subsequently, the much-hyped divorce between the UK and the EU took place in January 2020 (BBC, 2020b). Though, the EU Parliament approved the agreement on 29 January 2020 to avoid a “No Deal” Brexit and has provided the much-needed transition time till 31 December 2020. However, there is a lot of ambiguity and uncertainty surrounding the Brexit legislation, whether the designated time would be enough to crack a deal and what happens next (McCarthy, 2020). For example, if yes, then will the UK get access to the EU’s single market on the lines of Switzerland? If not, then will it end the era of free movement of goods and services and bring in tariffs, duties and other regulatory restrictions that would be agreeable for both the UK and the EU?

When the UK was an EU member State, it had to legally abide by the EU standards on labour rights, tax, and environmental protection (BBC, 2020a). However, in the Brexit legislation, Prime Minister Boris Johnson has moved these commitments into a separate non-binding political declaration (BBC, 2020a). This move will provide UK liberty in economic and trade policies with non-EU States. In the meantime, this move will make it hard for the UK to get a comprehensive economic deal with the EU as Brussels may not allow the UK access to its single market while undercutting the competitiveness of its member States (Evans, 2019). Hence, the second scenario is more likely to happen, which will result in a tremendous rise in cost and time for goods moving in and out of the English Channel. The UK-EU trade relations is based on a balance in which the UK has a services surplus on the EU, and the EU has a goods surplus in the UK. The second case scenario will result in increased prices of goods imported by the UK from the EU and simultaneously increasing the cost of services provided by the UK (Read, 2020). This scenario will not only have an adverse impact on industries of the UK and the EU but also on the industries of non-EU States who have their offices in the UK and the EU and trade goods and services across the English Channel. Additionally, the UK will also have to invest heavily in upgrading of its ports and entry points to be able to deal with checks, customs and other regulations (Whitfield, 2020). A study conducted by the Imperial College London shows that every extra minute to check goods at the UK ports will lead to additional traffic of 10 miles in queues (BBC, 2018).

All these developments will make the UK develop strong economic relations with non-EU States, and China serves as the best opportunity in the given circumstances. Currently, only China, which has the capacity to invest in the UK’s infrastructure development and emerge as a net exporter of commercial goods. In the 2018 bilateral declaration, the UK and China already agreed to safeguard multilateralism and promote an open world economy guided by World Trade Organization (WTO). Also, the UK and China signed around 12 deals in the fields of finance, trade, smart city and health care and pledged to further elevate their relations under the Golden Era (Bo, 2018). Most importantly, Brexit has given more impetus for the UK to combine Britain’s National Infrastructure Plan with China’s BRI.

The EU had included the UK in its strategies to negotiate a free trade agreement (FTA) with China, an ongoing process since 2013. The EU and China have entered into talks to offer investors predictable opportunities from both sides, longstanding access to the Chinese and European markets, and shelter investors along with their investments (Devonshire-Ellis, 2019). However, these discussions have stopped on various issues, not least concerning access to the markets of China. These talks are currently at a dead-end, and no progress is expected shortly since the Brexit. Consequently, an FTA between the UK and China would undoubtedly be of significance for the UK. However, it may fall behind the UK-US FTA. For example, in the US-Canada-Mexico Agreement (USMCA), Washington insisted on elements within the agreement that impact and prevent Mexico and Canada to limit their trade agreements with Beijing (Miller, 2018). It is noted that USMCA member States can terminate this agreement with a notice of six months and free to negotiate their new bilateral agreement if one of the partners enters into an FTA with China (Lester et al., 2019). Article 32.10 of the USMCA, has also reported causing controversy in Canada (Massot, 2018).

Given the situation, China may have a new partner for its ambitious plan to expand China’s economic cooperation and influence overseas. The UK’s Prime Minister Boris Johnson stated in the day before he chaired the country that his government would be very ‘pro-China’, “we are very excited about the BRI, and promise to keep Britain ‘the most open economy in the EU for Chinese investments” (Gehrke, 2019). The BRI is China’s strategic project to use infrastructure investments to gain influence over principal seaports, airports, and railways across the globe. On the other hand, Hua Chunying, the Chinese Foreign Ministry spokeswoman, stated that “China attaches importance to the China-UK relations and hopes that the UK will continue to work with China to ensure the sustained, steady, and sound development of China-UK relations in the spirit of mutual respect and win-win cooperation” (Chunying, 2019). The positive talks from both sides signal positive post-Brexit Sino-UK relationships.

Chinese commitment and response to Brexit will also depend on how the UK and the EU handle the situation and set their priorities. Additionally, the working of the transmission channels concerning trade and foreign direct investments can lead to deviations from the likely impact of the model that requires adjustments by trial and error. The present state of negotiations between the UK and the EU suggests that for various reasons, the Swiss-style bilateral agreement, the Norwegian-style European Economic Area Agreement, and the Turkish-style customs union are unlikely to happen (Dhingra and Sampson, 2020). All models are in a compromise dilemma between economic benefits and political costs. The negotiations to date show that the desire to maximise economic benefits and minimise administrative costs are not the options from the UK. However, the Chinese viewpoint demonstrates that economic relations with the UK as well as market access agreements for capital, goods, and services should be negotiated other than the current EU conditions. Besides, in the case of the Sino-UK trade deal, the UK, as a small State, will have limited bargaining capacity in trade and investment negotiations as compared to China. Consequently, China could negotiate additional approving market access conditions with the UK than the current conditions under the EU’s auspices and be able to make the best use of the British port industry to access the European markets. Further, China has an opportunity to invest in development projects of Wales, and Northern Ireland as post-Brexit, the EU’s regional development programmes will stop China’s funding in these regions (Dhingra and Sampson, 2020). Further, China also has an opportunity to invest in development projects of Wales and Northern Ireland since, in the post-Brexit era, the UK no longer be part of the EU. As a result, the EU’s regional development programmes will stop their funding in these regions (Dhingra and Sampson, 2020).

There are already vibes that Britain emphasised its role as a natural partner for the Chinese BRI project. A careful study of the chronological events portrays that the UK is interested in signing an FTA with China when it exited the EU. As China drives forward the BRI from the east, Britain can work as a natural partner in the West and be willing to collaborate with all BRI partner-States. The very aim is to make this initiative successful, maintain close as well as open commercial partnerships with its neighbours in Europe, FTAs with new partners, and protect old allies around the globe, especially China (Connor, 2017).

The long-pending Brexit divorce finally took place in January 2020. However, there is still much uncertainty surrounding the deal as the above sections clearly show that there are a number of issues that have not been solved yet and will take further one or two years of negotiations to settle them. Further, Brexit will not only affect the UK and the EU but also impact their relations with other major powers across the globe. Since the launch of BRI, China has become the bandwagon of multilateral economic collaborations all over the world. As uncertainty has become the new normal in the 21st century, it is essential to understand the impact of Brexit on the EU and its relations with China. This following (sub)sections will shed light on the challenges and opportunities in front of the EU and China in the post-Brexit world.

With Brexit, both the EU and China face few challenges as a well-established system will come to an end. The EU loses its most crucial partner, who had become an economic gateway of the EU to the world (Blockmans and Emerson, 2016). In the meantime, China lost its most crucial patron in the EU, which was enthusiastically negotiating an FTA between China and the EU. Various scholars and research institutions around the world have studied the impact and calculated various scenarios as possible outcomes of Brexit (See, e.g., Moschieri and Blake, 2019). However, whatever the outcome will be, the relationship between the EU and the UK will not be the same as in the pre-Brexit era. According to a study published by Germany’s Bertelsmann Foundation, Europeans will lose billions of Euros annually with soft or hard Brexit (Pandey, 2019). In 2018, the EU exported nearly 18 percent of its goods and services to the UK, excluding the trade among the 27 EU States (Walker, 2018). At the same time, the UK’s 45 percent total export and 53 percent of total import are sourced from the EU (Walker, 2018). If tariffs and other restrictions come up between them, the EU will suffer a loss of around €40 billion and €57 billion, respectively in their annual income (Pandey, 2019).

Brexit will also have a political impact on the EU; in particular, it will damage the EU image as a stable and robust united front in the aftermath of the second world war (WWII). The EU will also lose one of its two places in the United Nation Security Council (UNSC). Brexit will adversely impact the EU’s global status and soft power, which will reduce its ability to play a decisive role in a global security crisis (Blockmans and Emerson, 2016). Whenever the interests of the UK and the EU may differ, there are possibilities they may find themselves in opposite camp during negotiations of a particular issue in the United Nations. However, Brexit has been instrumental in bringing all the 27 EU member States together on one platform, which was never seen during any earlier issues. After seeing the chaotic and painful process of Brexit and its aftershocks, the demands of other States leaving the EU has disappeared. The populist voices of Frexit (France), Nexit (the Netherlands) and Italxit (Italy) have stopped popping up from the populist leaders in these States (Erlanger, 2020). Further, the EU will still remain the most influential transnational union and the single largest market in the world, and various reports are showing that if the EU is able to negotiate a favourable deal with the US and China, they are set to benefit from Brexit (Summers, 2017; Charlemagne, 2020).

Since the establishment of diplomatic ties between the EU and China, the relationship has seen gradual development. In the initial few years, the EU used to propagate its economic and political superiority and was keen to replicate its development model all over the world, and so do in China. However, at the beginning of the 21st century, China becomes the fastest trillion-dollar developing country based on its indigenous Chinese model. During the same period, Europe longed to come out of the US hegemony and proposed an independent foreign policy by engaging with emerging powers, particularly with China (Javier Solana, 2009). In 2003, the EU and China initiated the EU-China Comprehensive Strategic Partnership to strengthen and expand cooperation in a wide range of areas (Maher, 2016). The 2009 economic crisis saw a decline of the European economies, and China emerged as the vanguard of modern commercial and economic relations. Further, in 2013, the EU and China mutually adopted the EU-China 2020 Strategic Agenda for Cooperation to enhance their relationship and develop their new partnership. The year 2015 saw the peak of their relationship; China hosted the 16 + 1 summit for the Eastern European Countries. The UK and Germany became the founding member of the China-backed Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB), more so the UK promised to be China’s best partner in the West. However, since 2016 their relationship has faced few stumbling blocks, particularly Brexit, FTA, and differences over non-market and market economy status (Ewert, 2018). Now that the UK is out of the EU, it becomes essential for China and the EU to engage themselves with each other and try to develop a new relationship.

The EU-China relationship is of critical economic importance as China is the EU’s largest trading partner, and the EU is China’s second-largest trading partner. Though post-Brexit, these trade algorithms are set to change, this relationship will remain central to trade and commercial policies for both partners, as they play a significant role in the global economy. The exit of the UK from the EU will initially complicate the relationship between the EU and China, given the central role played by the UK in framing the EU’s China policy (Gaspers, 2016). However, given China’s growing influence in world affairs, these complications will be sorted out and resolved once the EU and China develop a post-Brexit mechanism for economic engagement either under BRI or FTA. There are different opinions among the EU Member States on the economic relationship with China. Some are in favour of giving China the status of a market economy. In contrast, others argue on practising a protectionist policy to protect their manufacturing industries against the competitive prices of Chinese goods. Nevertheless, they all agree that China has played an essential role in bringing economic prosperity in the region by providing huge investment in European infrastructure and a large market to European brands and companies (European Parliament, 2016).

China has primarily three main expectations from its relationship with the EU: firstly, access to the EU single market; secondly, a secure environment for Chinese investments and, willing partners for China’s BRI projects; thirdly, a profound diplomatic relation in the milieu of increasingly peevish relationship with the US (Yu, 2017). In the case of Europe, except Germany, most of the EU Member States are facing economic stagnation. Hence, they are in need of Chinese investment. The EU wants access to the Chinese market, which has become the biggest market for luxurious product reflecting the economic progress in the country. The EU is also dependent on China for rare earth metals. Lately, the EU is facing the wrath of the US, as divergence has increased between them on the issues of tariffs, defence spending, security policies, climate change and many more (European Parliament, 2018).

These conditions and expectancies provide much stimulus for the EU on China in order to overcome their trust deficit and form synergies in the areas of trade, economics and security (Garrie, 2020). In 2019, the EU and China signed a bilateral trade Geographical Indication Agreement on ‘hallmark’. It is the first high-level bilateral agreement China has ever signed with foreign businesses (Global Times, 2019). In the backdrop of the US freezing the Appellate Body at WTO, the EU, along with China and other 15 States joined hands to unblock the world’s trade arbiter by creating a temporary mechanism to settle trade disputes (Blenkinsop and Baker, 2020; Burden, 2020). The EU Member States, which would have been adversely affected by the Brexit, had already started developing new economic ties among themselves as well as with other States to whom they have shared common concerns and interest.

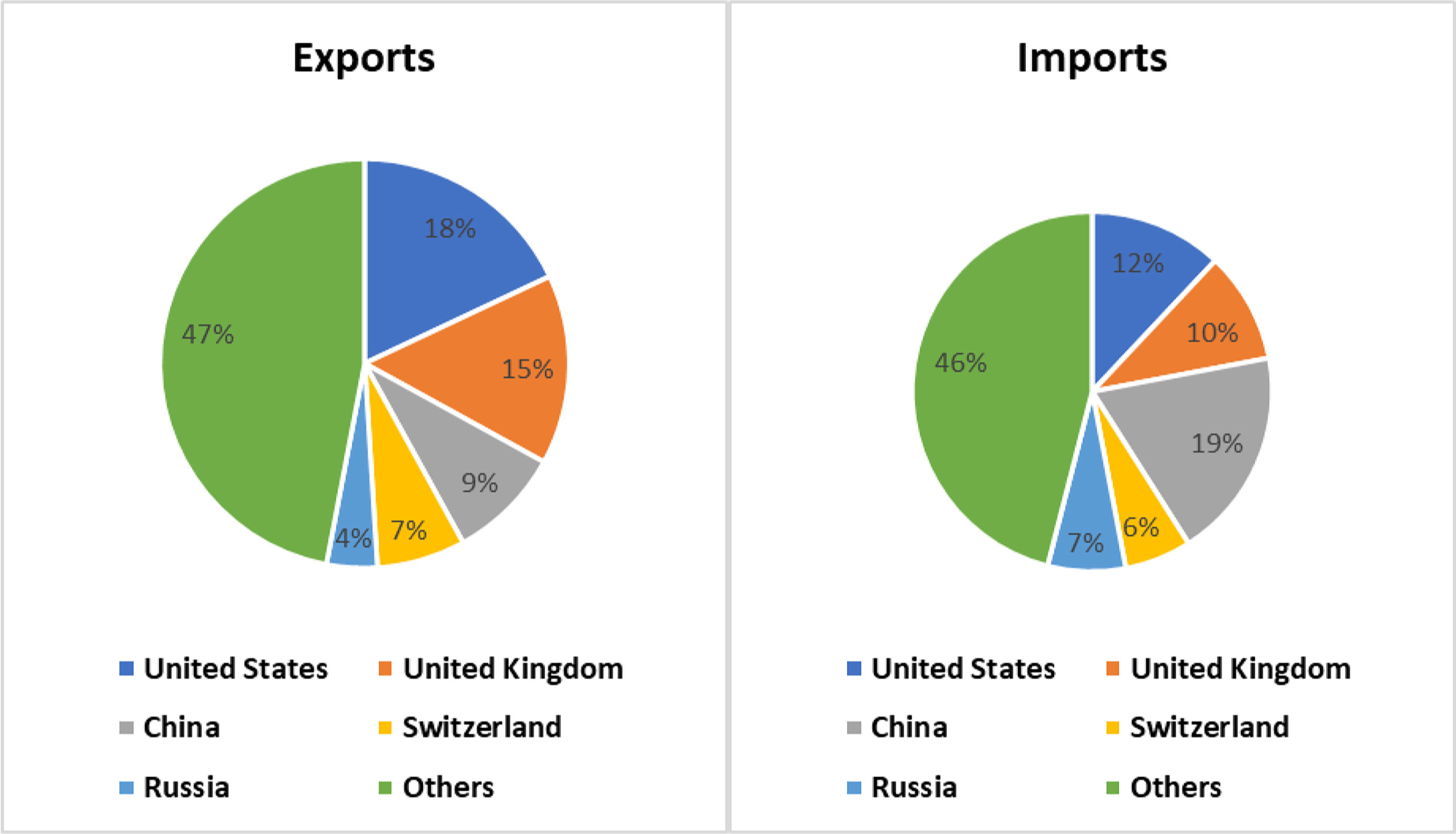

The trade partnership between China and EU member states has been tremendous as shown in Figure 1—China is one of the key trade partners of the EU (in both exports and imports). Many EU Member States which have not fully recovered from the financial crisis have looked at China for investment, for capital generation, infrastructure development and market access. Further, China has heavily invested in infrastructure development and operations of major European ports in Greece, France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. Greece and Hungry have already become close allies of China, Italy became the first G7 States to sign the BRI. If the EU and China overcome their differences and focus on building trust, there is plenty of room to create a win-win situation where everyone benefits.

Figure 1 EU-27 Trade Volume with China-2019. Source: European Commission (European Commission, 2019).

With 7500 km of coastal line strategically located at the centre of the most crucial trade lines gives enough logistic leverage to India to develop a trade centre in the Indian Ocean. Further, the Indian Ocean has emerged at the centre of Chinese maritime economic strategy, as most of its trade routes to Europe, Africa, the Middle East and South Asia cross through the Indian Ocean. Sino-Indian maritime cooperation has the potential to shape the economic nature of the Indian Ocean and, most importantly, bring peace and stability to the region (The Print, 2018). India and China’s economic relations with the world and especially the EU largely depends on peace and stability in the Indian Ocean region. The time has come for India and China to realise the true potential of their cooperative partnership. In the words of President Xi Jinping, “If the two countries speak in one voice, the whole world will attentively listen; if the two countries join hand in hand, the whole world will closely watch” (MOFA-PRC, 2014).

Currently, India is engaged in massive developments of its ports. If China and India cooperate on port construction and infrastructure development, it will undoubtedly create a win-win situation for both States. Indian ports on the western coast can be connected to West Bengal and have the potential to connect Kunming city in Yunnan Province of China under the Bangladesh–China–India–Myanmar (BCIM) Forum for Regional Cooperation. Further, India-China Transhipment cooperation will help China to reduce its distance not only to European and African continents but also to the eastern coast of North and South America (Valentine, 2017).

In the era of globalisation, the financial activities and trade of any State are highly influenced by the global market and modern technologies. However, most of the trade around the world is still carried out through the waterways, which is the most cost-efficient method. Currently, 90 percent of India’s trade by volume and 70 percent by price is handled by Indian ports (PIB-India, 2018). To facilitate its ever-increasing maritime trade, India has recently prioritised the up-gradation of its ports and maritime connectivity. Modern ports will enable India to enhance its cost-effectiveness through the improved maritime logistic system. In the meantime, China is not only ahead of India but has also developed world-class technology in the construction and development of deep seaports and has a desire to invest in development projects all over the world. India is one of the fastest-growing trillion-dollar economies and has the best potential to give out huge returns on Foreign Direct Investments (FDIs) (The Hindu Business Line, 2020). These circumstances have created more than enough reasons for India and China to cooperate in this domain.

On 13 January 2011, the Indian government declared the Maritime Agenda 2010-20 to rationalise measures for the public-private partnership (PPP) process by encouraging confidence in investors and making it more transparent (PIB-India, 2011). In order to accomplish India’s maritime infrastructure requirements from 2010-2020, the Maritime Agenda had categorised priority areas for government interference. It aimed at expanding the port capacity to 2,300 million metric tonnes (mmt) by 2016-17 and more than 3,000 mmt by 2020, and hence a comprehensive plan was laid out to meet the prerequisite (MoS-India, 2011). The Agenda focused on developing the existing small ports into all-weather, deep draught ports and encourage the creation of private greenfield ports (MoS-India, 2011). However, the overlapping of regulations among the state government agencies and port authorities in the management of the Indian ports caused huge delays in port development activities. Hence India needed a more robust and simplified regulatory framework to have swift administration and development of its maritime trade (Global Times, 2020). All these circumstances have created a suitable environment for India to join the MSR. As India played a major role in the ancient MSR, time has resurrected the journey and utilised the various opportunities.

Now the question arises, how will China and India successfully cooperate in their maritime sector in spite of having strategic differences and recent border tensions? It will largely depend on the mutual understanding among the current leadership and cooperative partnership between both the States. The world has become more complex and fragile due to the ongoing clash between the US and China (Swaine, 2019). Under the current circumstances, it becomes essential that India and China do not act against each other in favour of third parties, undermining their own-interest and mutual benefits (Basu, 2020; Hindustan Times, 2020; Zhu, 2020). In the international world order, no country is a permanent friend or foe; the only thing that makes countries cooperate or dispute is their national interest. At present, the national interests of both countries lie in the domestic development and economic prosperity of their combined 2.7 billion population. The US has upped the ante against China as it feels a rising China is a threat to its global hegemony. It has also initiated to beef up its strategic partnership with Japan and Australia. Further, it has urged India to play a bigger role in the Indo-Pacific (Habib, 2020; Zhu, 2020). Unlike Japan and Australia, India has been cautious, not to spoil its relations with China and has been persistent in its efforts, not to make QUAD nations (Japan, US, Australia, and India) into an anti-China alliance (Mehra, 2020).

However, after the recent border clashes, there is an outcry among the Indian nationalist groups to ban Chinese companies as well as cancel engineering and construction contracts given to Chinese companies (Zhu, 2020). Instead of taking decisions in rage, India should calculate its self-interest and act consequently. No one stops India from banning foreign investments in strategic security sectors; however, banning Chinese companies from infrastructure and other non-strategic sectors may harm the Indian economy more in future. Today China has the most advanced engineering and infrastructure technology, and it offers a very competitive price. The infrastructure contracts were given to the Chinese companies as they were the lowest bidders; cancelling such contracts will increase the cost of projects and cause unnecessary delays (Hindustan Times, 2020). If India wants to develop its port infrastructure, China is the best option available which already has experience in constructing and maintaining huge ports.

For China, the time has come, to look beyond its US-centric foreign policy and look for developing a constructive partnership with other developing countries and especially India (Zhu, 2020). Good relations with India will not only provide essay access to Indian markets, but if the trust increases and cooperation deepens, one cannot rule out the possibility India China Economic Corridor connecting Tibet and Yunnan Province of China to Eastern ports of India and further to the Western ports complementing India’s Sagarmala Programme (Summers, 2017; Ramesh, 2019). Hence China should also rein in its hardliners and try to develop a cooperative and constructive partnership with India (Feng, 2020; Singh, 2020).

The Impact of Brexit has been felt around the world, and so do in India. The UK has historical ties with India since the colonial era, and presently, it is the second-largest trading partner of India among the European states. Further, the UK has emerged as the seventh-largest FDI source for India (Statista, 2020). Whereas India, with over 120 projects, has emerged as the second-largest investor in the UK, just behind the US (Sonwalkar, 2020). During his 2019 general elections, UK Prime Minister Borris Jhonson had promised to develop a “Truly Special India-UK relationship” (Sonwalkar, 2020). The UK has also included India in the list of its ‘Ready to Trade’ campaign launched in February 2020, which aims at developing economic relations around the globe (Rai, 2020).

However, the future of Brexit is ambiguous in the current situation as the UK and EU have still not reached a breakthrough exit deal. Around 800 Indian companies are operating in the UK; most of these countries use it as a single point entry into the European market. If the UK is unable to get an FTA with the EU, Indian companies will have to relocate or establish additional offices in other European countries to access the European market. Further, India will also have to negotiate separate trade arrangements with the UK and EU. Presently, the EU is India’s largest trading partner. India and the EU have been in negotiations for a trade agreement since 2007, and in 2018, the EU adopted a new EU-India strategy that emphasis finalising the trade deal and enhance economic cooperation between them (Arthur Sullivan, 2019). The future of the India-UK relationship and the India-EU relationship will highly depend on the future of the UK-EU relationship.

From the aspect of India’s port governance and maritime trade, Brexit provides both positive and negative opportunities to India. However, from the aspect of MSR, it is essential to have a stable India-China relationship. The MSR will only be successful if there is stability along the sea lanes it passes, which is only possible when India-China along with other regional powers co-operate with each other. Hence, India and China need to readjust their current policy towards each other and make genuine efforts to utilise the maximum possible benefits from their potential cooperation.

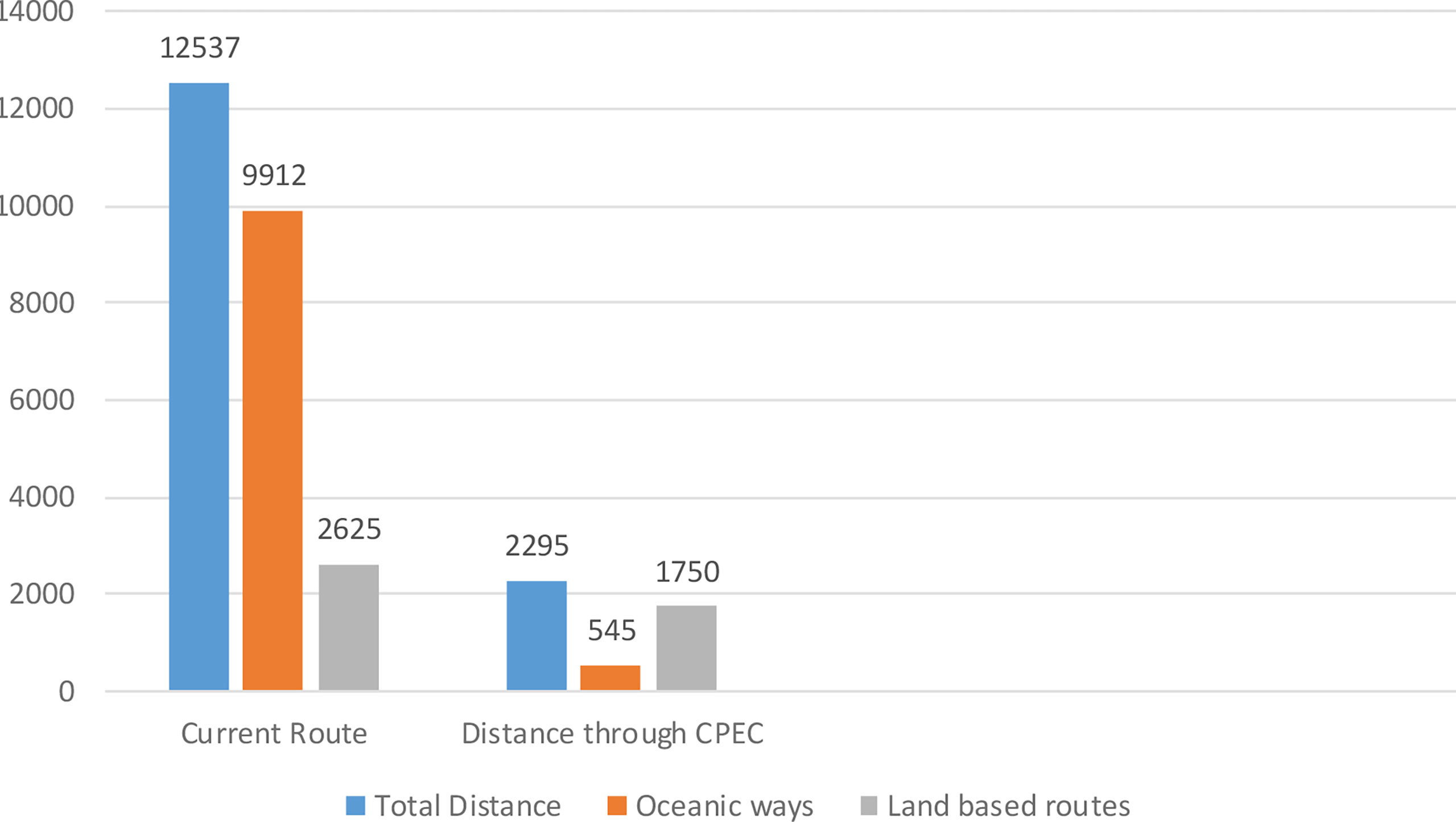

Pakistan is heading towards a more robust maritime and port governance with Chinese cooperation under the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) (Chang and Khan, 2019). The corridor will not only provide the roadways to China but also open it to the Indian Ocean and the Arabian Sea from the Gwadar port, that will tremendously help China to strengthen its maritime metier, and in a broader perspective, will link it to the European locations. The Middle Eastern oil reserves will be only approximately 2,295 miles (545 miles from ocean routes and 1,750 miles from roads) from China via the CEPC route, compared to the current distance of 12,537 miles; 9,912 miles from ocean routes and 2,625 miles land route (see Figure 2) (The Gulf Today, 2017). Since the sea flow over the port of Gwadar is expected to rise, therefore, maritime security and cooperation are essential. A multidimensional approach requires addressing the security challenges of this maritime region to ensure the security of the Gwadar port. This includes major security forces, coastal exercises and law enforcement agencies seeking to increase the region’s growing awareness in which maritime transport, piracy and human trafficking are among the key challenges. As a result, the Pakistani Navy is working with Chinese cooperation and support on three important issues: the security of the port of Gwadar, the safety of the seaways and the safety of the ships (The Value Walk, 2017).

Figure 2 Comparison of Mileage between the Current Route and Proposed Route under CPEC Project (Abu Dhabi to Shanghai, in Miles). Source:Created by the author.

Chinese interest in the port of Gwadar is momentous for several reasons. For example, in order to meet its energy needs more resourcefully, to address economic problems in western China and its unique economic development. China also plans to build a long oil pipeline from Gwadar to Xinjiang along with an oil refinery in Gwadar to facilitate the transport of oil from Africa and the Persian Gulf (The News, 2018). In addition, China has already provided a 3rd 600-tonne patrol vessel to Pakistan under an agreement signed in 2015. Besides, the Pakistani Ministry of Defence Production (MoDP) has entered into an agreement with China’s Shipbuilding and Trading Company to build four patrol vessels of 600 tons and two of 1,500 tons for the Pakistan Maritime Security Authority (PMSA). These ships were gained to enhance PMSA’s ability to protect the marine resources of Pakistan in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ) in addition to conduct operations against illegal immigration, drug and human trafficking under the provisions of international (maritime) law (Haider, 2015).

Maritime security cooperation between China and Pakistan is vital not only for political stability and regional peace, but also beyond that. With these goals in mind, Chinese collaboration under the CPEC shows that it has achieved its broader goal of gaining a foothold in the maritime sector and economic growth as a whole. For this purpose, the construction of ports and coastal structures represents a significant step forward in expanding China’s maritime approach athwart the Indian Ocean through the Suez Canal in the Mediterranean basin. China demonstrates the same collaborative approach across the globe so as to its intention to develop profound cooperation in the maritime sector of the UK after the Brexit. Among all other, one of the main objectives is to ensure the maritime communications route, which accounts for almost 90 percent of China’s trade and energy supply (Chang and Khan, 2019). This very Chinese strategy will significantly assist China in securing or remoting access to the European markets through the ports and shipping through the shortest available sea passage to connect China and the EU.

In 2017, UK’s Minister for International Trade Greg Hands said that the UK is a free trade influenced country and can be an important partner for both Pakistan and China in the implementation of massive infrastructure projects planned between the two countries, such as CPEC (The Economic Times, 2017). He also added that as part of an outward-looking global UK, the country has a clear goal of increasing trade with China and Pakistan, and UK businessmen are well-positioned to take advantage of the country’s new opportunities in the region (The Express Tribune, 2017). These developments offer British companies with new opportunities to bring their research and development (R&D) expertise to Pakistan through partnerships with the public and private sectors; there can be numerous ways to attract the UK government as well as private investors to move forward, including education, health, agro-technology, renewable energy, urban transport, including road freight and temperature-controlled logistics, infrastructure development, textile, fabrics and clothing, and so on (Jarral, 2019).

It is also pertinent to mention here that bilateral trade between the UK and Pakistan was £2,043 million in 2019, with Pakistan having an advantage (The Natnation, 2020b). The UK is currently the third-largest source of FDI in Pakistan after China and the Netherlands, and accounts for 8% of FDI in Pakistan (CPEC, 2020a). European investors would like to invest in Allama Iqbal Industrial City—a priority EEZ as part of the CPEC. To take full advantage of these opportunities, UK companies would like to see further progress in lowering corporate tax rates, protecting the privacy and making business easier (CPEC, 2020b). CPEC and Brexit are two significant developments, and as global economic gravity shifts to Asia, Pakistan opens up new prospects for business opportunities that will benefit people in both countries (The Natnation, 2020a). Besides, the UK has overtaken China and is now the second-largest export market and also the largest market in Europe (CPEC, 2020b).

The above facts can help to draw a clearer picture of the significance of the relationship between the post-Brexit UK and Sino-Pakistan maritime cooperation in the Gwadar port. Therefore, it is fair enough to comment that Gwadar is going to become the UK’s post-Brexit trade destination in Asia, connecting China and other Asian States connected under CPEC with not only the UK but the whole of Europe as well.

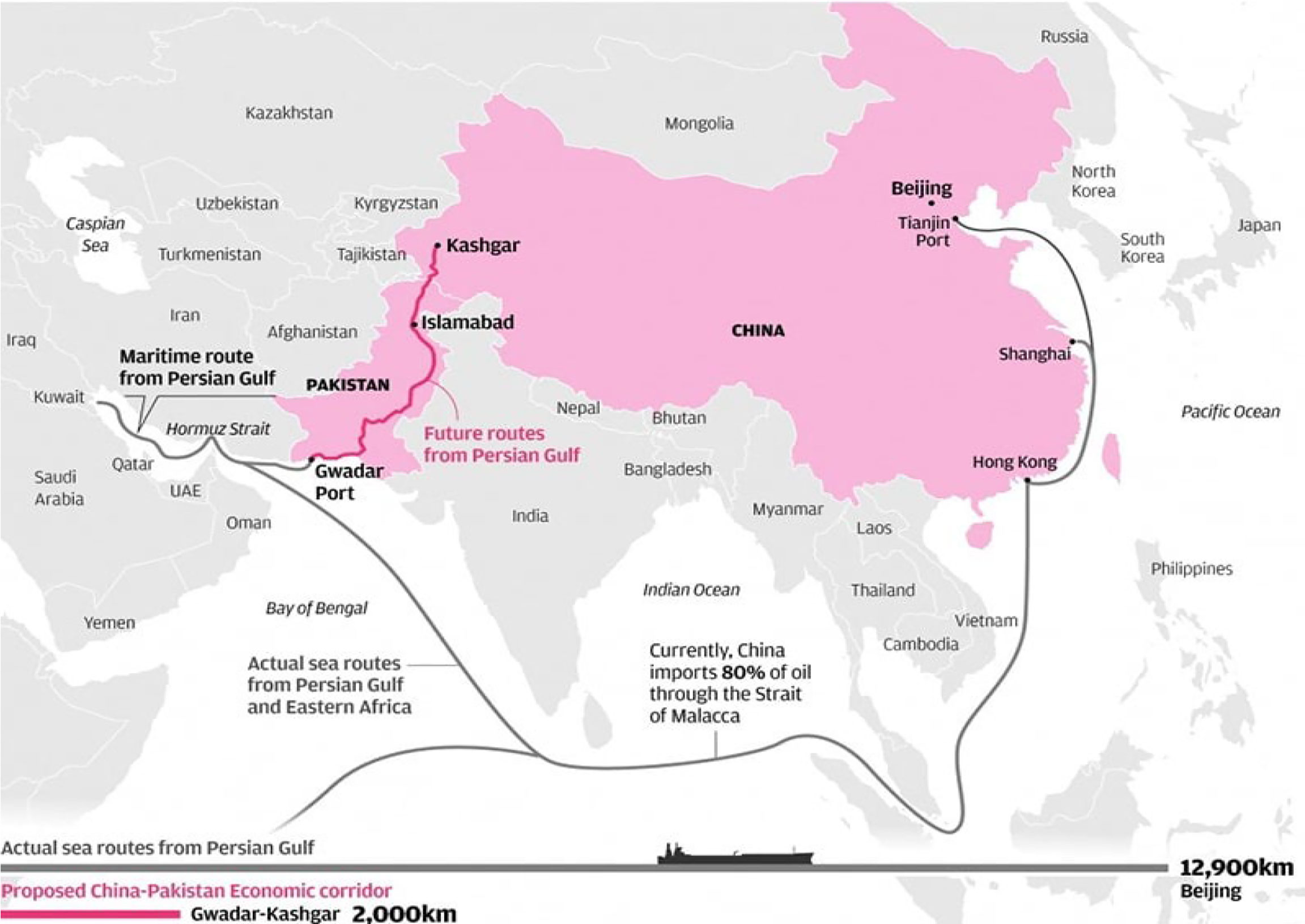

After the Brexit, UK will freely negotiate and decide its trade-related activities and preferences in terms of agreements with States across the globe through using its ports. As China could be one of the largest UK’s trade partners, both States will have to look into the possible feasibilities in their trade through the Sea and Shipping. To this end, the Gwadar port of Pakistan can play a crucial part since it opens China to the Arabian Sea as well as in the Indian Ocean, providing the shortest route to approach the Indian Ocean and reach out to Europe ultimately through the Hormuz Straits. Therefore, China can plight ahead toward the UK and other European countries and vice versa (using the new shortest passage under CPEC) far better than its current MSR route (see Figure 3), which connects China to Europe through South China Sea-Malaysia-Singapore (Malacca Straits)-SriLanka-Arabian States-Africa and then heading toward Europe. It is important to mention here that currently, it takes around 16 days to reach out to the Indian Ocean (from Shanghai) as compared to the reduced distance to 3-4 days through the proposed CPEC route (a mix of land-based as well as an oceanic route) though Gwadar Port of Pakistan (Chang and Khan, 2019). This will shorten the distance as well as save time and money on the one hand, and on the other hand, provide a strategic way out to China for international trade if its surrounding coastal neighbours hinder its oceanic routes, for example, uncertain challenges in the South China Sea—ensuring its uninterruptable trade relations with the UK and the EU.

Figure 3 Map of the Maritime Silk Road with New Shortest Route through CPEC. Source: The Dawn (Ebrahim, 2015).

The context of EU/UK-China relations has changed dramatically over the past few years; China’s interest in Europe has increased significantly. While some common patterns exist, new trends in trade and investment relations with China are expected to be widely differentiated across the EU and the UK after Brexit. Chinese players are constantly scrutinising new developments in European markets and are eager to utilise opportunities whenever they arise. So entering into a new trade relationship through ports and shipping could be a great avenue and win-win situation for both sides.

It is a fact that around 80% of the world trade is conducted through maritime routes across the globe, and China is one of the largest countries that largely conduct their trade through shipping. Similarly, the EU and the UK are the key players in the world’s maritime trade. However, Brexit is likely to change the situation since the division of port governance between the EU and UK may impact their maritime trade. The other future challenge that Sino-UK/EU trade may face is the possible blockade by the countries across the Indian Ocean region using the current MSR route through Malacca Straits. However, China has sensibly planned alternative routes to ensure maritime trade security, i.e., through the Indian Ocean via Malacca strait with Indian cooperation, and the new and shortest trade route under CPEC, which opens China to the Indian Ocean via the Arabian sea. Since the UK, after Brexit, has tremendous trade interests in this region, therefore, branding its ties with China with alternative maritime routes could be beneficial for Sino-UK trade relations ahead. To this end, construction of Gwadar port and connecting China to Indian Ocean through Arabian Sea could serve the multiple purposes to both sides, especially for China including the shortest trade route approaching UK and EU countries and energy security. Therefore, port governance with new trade expectations is the call of the day and the Gwadar port could play a significant role in this transaction. Eventually, both sides need to revise and ensure their maritime cooperation for a win-win trade relation in the coming years.

M.I.K deals with mainly the write-up, revisions and proofreads; S.L deals with the Indian perspective and general proofread; and Y-C.C deals with supervision and general guidelines. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Baker J. (2019). CEBR Says Maritime Sector Contributes $57bn to UK Economy ( Maritime Intelligence Informa). London. Available at: https://lloydslist.maritimeintelligence.informa.com/LL1129133/CEBR-says-maritime-sector-contributes-$57bn-to-UK-economy.

Basu D. (2020). Blaming China? Blame Those Who Keep Us Poor & Weak ( Business Standard). India. Available at: https://www.business-standard.com/article/opinion/blaming-china-blame-those-who-keep-us-poor-weak-120062101045_1.html.

BBC (2018). Post-Brexit Border Checks “May Triple Queues” to Port (BBC News). Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-kent-43318258. England.

BBC (2020a). Brexit: Boris Johnson Says “No Need” for UK to Follow EU Rules on Trade (BBC News). England. Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-51351914.

BBC (2020b). Brexit Divorce Bill: How Much Does the UK Owe the EU? (BBC News). Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/51110096. England.

Blenkinsop P., Baker L. (2020). EU, China and 15 Others Agree Temporary Fix to WTO Crisis (The Reuters). Brussels. Available at: https://www.reuters.com/article/us-trade-wto/eu-china-and-15-others-agree-temporary-fix-to-wto-crisis-idUSKBN1ZN0WM.

Blockmans S., Emerson M. (2016). Brexit’s Consequences for the UK – and the EU (Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS). Brussels. Available at: https://www.ceps.eu/ceps-publications/brexits-consequences-for-the-uk-and-the-eu/.

Bo X. (2018). China, Britain Pledge to Further Lift Golden-Era Partnership ( Xinhua Net). China. Available at: http://www.xinhuanet.com/english/2018-02/01/c_136940022.html.

Braakman A. J. (2017). Brexit and its Consequences for Containerised Liner Shipping Services. J. Int. Maritime Law 23, 1–12. http://www.emlo.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/11/005-Brexit-and-its-consequences-for-containerised-liner-shipping-services-A.J.-Braakman.pdf

Brown K. (2018). Britain’s China Challenge (The Diplomat). Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2018/01/britains-china-challenge/.

Burden L. (2020). EU Risks Wrath of US by Teaming Up With Beijing on Rival WTO Scheme (The Telegraph). Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/business/2020/01/24/eu-risks-wrath-us-teaming-beijing-rival-wto-scheme/.

Chang Y. C. (2018). The “21st Century Maritime Silk Road Initiative” and Naval Diplomacy in China. Ocean Coast. Manage. 153 (June 2017), 148–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ocecoaman.2017.12.015

Chang Y.-C., Khan M. I. (2019). China–Pakistan Economic Corridor and Maritime Security Collaboration: A Growing Bilateral Interests. Maritime Business Rev. 4 (2), 217–235. doi: 10.1108/MABR-01-2019-0004

Charlemagne (2020). The Eu’s Recovery Fund is a Benefit of Brexit ( The Economist). Europe. Available at: https://www.economist.com/europe/2020/05/30/the-eus-recovery-fund-is-a-benefit-of-brexit.

Chunying H. (2019) Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Hua Chunying’s Regular Press Conference on July 25, 2019 (Chinese Embassy in Pakistan). Available at: http://pk.chineseembassy.org/eng/fyrth/t1683397.htm (Accessed 24 March 2022).

Connor N. (2017). Hammond Says Brexit Britain Must Back China’s New Silk Road (The Telegraph). Beijing. Available at: https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/2017/05/14/hammond-says-brexit-britain-must-back-chinas-new-silk-road/.

CPEC (2020a) CPEC Likely to Become Trade Destination for UK After Brexit (China Pakistan Economic Corridor). Available at: http://cpecinfo.com/cpec-likely-to-become-trade-destination-for-uk-after-brexit/ (Accessed 17 August 2021).

CPEC (2020b) UK Investors are Ready to Join CPEC (China Pakistan Economic Corridor). Available at: http://cpecinfo.com/uk-investors-are-ready-to-join-cpec/ (Accessed 18 August 2021).

Devonshire-Ellis C. (2019). Britain’s New PM Boris Johnson Praises The Belt & Road Initiative – Could An EU Exit Mean A UK BRI Deal? (Silk Road Briefing). Available at: https://www.silkroadbriefing.com/news/2019/07/25/britains-new-pm-boris-johnson-praises-belt-road-initiative-eu-exit-mean-uk-bri-deal/.

Dhingra S., Sampson T. (2020) Life After Brexit : What are the UK’s Options Outside the European Union? (London School of Economics and Political Science). Available at: http://eprints.lse.ac.uk/66143/ (Accessed 24 March 2022).

Ebrahim Z. T. (2015). China’s New Silk Road: What’s in it for Pakistan? (The Dawn). Karachi. Available at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1177116.

Erlanger S. (2020). A Texas-Size Defeat for the E.U.: Brexit Is Here (The New York Times). Europe. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/01/29/world/europe/brexit-brussels-eu.html.

European Commission (2019) China-EU - International Trade in Goods Statistics (European Commission). Available at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/China-EU_-_international_trade_in_goods_statistics (Accessed 20 March 2022).

European Parliament (2016). China’s Proposed Market Economy Status: Defend EU Industry and Jobs, Urge MEPS (European Parliament). Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20160504IPR25859/china-s-proposed-market-economy-status-defend-eu-industry-and-jobs-urge-meps.

European Parliament (2018). State of EU-US Relations (European Parliament). Available at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2018/625167/EPRSATA(2018)625167_EN.pdf.

Evans E. (2019). What Brexit Did and Didn’t Change on Jan. 31 (Bloomberg).United Kingdom Available at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2019-12-18/what-brexit-will-and-won-t-change-on-jan-31-quicktake.

Ewert I. (2018). The EU Between the U.S. And China (China-US Focus). Available at: https://www.chinausfocus.com/finance-economy/the-eu-between-the-us-and-china.

Fairhead B. (2018). Why China’s Belt and Road Offers the UK Huge Opportunities (CAPX). Available at: https://capx.co/why-chinas-belt-and-road-offers-the-uk-huge-opportunities/.

Feng Q. (2020). Do India-China Relations Need a Reset? (Global Times). Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1196101.shtml.

Garrie A. (2020). EU Needs Refresh Attitude Toward Trade Ties With China ( Global Times). China. Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1178444.shtml.

Gaspers J. (2016). “Brexit is Bad News for European China Policy,” in MERICS Blog. Chatham House, the Royal Institute of International Affairs, London. Available at: https://blog.merics.org/en/blogpost/2016/07/12/brexit-is-bad-news-for-european-china-policy/.

Gehrke J. (2019). Brexit to China? Boris Johnson Praises Xi’s Belt and Road Initiative (Washington Examiner). Available at: https://www.washingtonexaminer.com/policy/defense-national-security/brexit-to-china-boris-johnson-praises-xis-belt-and-road-initiative.

Global Times (2017). China Signs Belt and Road Deals With 69 Countries and Organisations (Global Times). Available at: https://gbtimes.com/china-signs-belt-and-road-deals-69-countries-and-organisations.

Global Times (2019). China, EU Reach “Hallmark” Bilateral Trade GI Agreement: MOFCOM (Global Times). Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1169365.shtml.

Global Times (2020). BRI in Line With India’s Long-Term Development (Global Times). Available at: https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/1190258.shtml#:~:text=ThecoastofIndiaused,termsofpurchasingpowerparity.

Habib M. (2020). Will India Side With the West Against China? A Test Is at Hand (The New York Times). Asia Pacific. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2020/06/19/world/asia/india-china-border.html.

Haider M. (2015). Pak-China Sign Agreement for MSA Patrol Vessels ( The Dawn). Islamabad. Available at: https://www.dawn.com/news/1187352.

Heiduk G. (2018). “Does Brexit Influence China’s “One Belt One Road” Initiative?,” in Brexit and the Consequences for International Competitiveness. Ed. Kowalski A. M. (Springer International Publishing), 219–255. doi: 10.1007/978-3-030-03245-6

Her Majesty’s Government (2016). Alternatives to Membership: Possible Models for the United Kingdom Outside the European Union (Her Majesty’s Government), 6. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/504604/Alternatives_to_membership_-_possible_models_for_the_UK_outside_the_EU.pdf

Hindustan Times (2020). On China, Put India First’ (Hindustan Times). India. Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/editorials/on-china-put-india-first-ht-editorial/story-Zwmg305ch8ADVWpD75RZdP.html.

Jarral K. (2019) Pakistan-UK Trade Post-Brexit: Making the Most of it (The Asia Dialogue). Available at: https://theasiadialogue.com/2019/01/18/pakistan-uk-trade-post-brexit-making-the-most-of-it/ (Accessed 18 September 2021).

Javier Solana (2009). European Security Strategy: A Secure Europe in a Better World (Brussels, Belgium: General Secretariat of the Council). Available at: https://www.consilium.europa.eu/media/30823/qc7809568enc.pdf.

John Goods (2020) What Does Brexit Mean for the Shipping Industry? (John Goods). Available at: http://www.johngood.co.uk/2017/05/23/brexit-shipping-industry/ (Accessed 21 March 2022).

Lester S., Manak I., Zhu H. (2019). The Canada-China FTA in Peril Part 1: The USMCA “Non-Market Country” Provision’ (Georgetown Journal of International Affairs). Available at: https://www.georgetownjournalofinternationalaffairs.org/online-edition/2019/2/28/the-canada-china-fta-in-peril-part-1-the-usmca-non-market-country-provision.

Maher R. (2016). The Elusive EU – China Strategic Partnership Vol. 4 (International Affairs), 959–976. 10.1111/1468-2346.12659

Massot P. (2018). The China Clause in USMCA is American Posturing. But It’s No Veto (The Globe and Mail). Ottawa. Available at: https://www.theglobeandmail.com/opinion/article-the-china-clause-in-usmca-is-american-posturing-but-its-no-veto/.

McCarthy N. (2020). Brexit Costs Close To Matching Britain’s Total EU Contributions [Infographic] (Forbes). Available at: https://www.forbes.com/sites/niallmccarthy/2020/01/21/brexit-costs-close-to-matching-britains-total-eu-contributions-infographic/#645a14b01c55.

MDS Transmodal (2016) The Value of Goods Passing Through UK Ports (MDS Transmodal). Available at: https://www.abports.co.uk/media/x5dh111e/the-value-of-goods-report.pdf (Accessed 21 March 2022).

Mehra J. (2020). The Australia-India-Japan-US Quadrilateral: Dissecting the China Factor (ORF Occasional Paper: Observer Research Foundation). Available at: https://www.orfonline.org/research/the-australia-india-japan-us-quadrilateral/.

Miller E. (2018) What the USMCA – The New NAFTA – Means For The Environment (Idea Stream). Available at: http://www.ideastream.org/news/what-the-usmca—-the-new-nafta—-means-for-the-environment (Accessed 2 December 2021).

MOFA-PRC (2014). In Joint Pursuit of a Dream of National Renewal ( Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Peoples Republic of China). China. Available at: https://www.fmprc.gov.cn/mfa_eng/topics_665678/zjpcxshzzcygyslshdsschybdtjkstmedfsllkydjxgsfw/t1194300.shtml.

Moschieri C., Blake D. J. (2019). The Organizational Implications of Brexit. J. Organ. Design 8 (1), 1–9. doi: 10.1186/s41469-019-0047-8

MoS-India (2011) Maritime Agenda 2010-2020, Ministry Of Shipping (Government Of India). Available at: https://tgpg-isb.org/sites/default/files/document/strategy/Shipping.pdf (Accessed 18 August 2021).

NDRC (2015) Vision and Actions on Jointly Building Silk Road Economic Belt and 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, The National Development and Reform Commission, Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Peoples Republic of China. Available at: http://en.ndrc.gov.cn/newsrelease/201503/t20150330_669367.html (Accessed 9 December 2021).

ONS-UK (2017) Trade Statistics December 2017, Office for National Statistics (ONS) -Uk. Available at: https://www.ons.gov.uk/releases/uktradedec2017 (Accessed 21 March 2022).

Pandey A. (2019). Brexit to Cost Billions in Income Losses Across Europe ( Deutsche Welle). Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/brexit-to-cost-billions-in-income-losses-across-europe/a-47991332.

PIB-India (2011) Maritime Agenda 2010-2020 Launched 165000 Crore Rupees Investment Envisaged in Shipping Sector by 2020 (Press Information Bureau, Government of India). India. Available at: https://pib.gov.in/newsite/PrintRelease.aspx?relid=69044 (Accessed 18 August 2021).

PIB-India (2018). Year End Review 2018 – Ministry of Shipping (Press Information Bureau, Government of India). Available at: https://pib.gov.in/PressReleasePage.aspx?PRID=1555877.

Power V., et al. (2016) Brexit and Shipping, a&L Goodbody. Available at: http://www.algoodbody.com/media/Brexit and Shipping.pdf (Accessed 21 March 2020).

Premti A. (2016) Liner Shipping: Is There a Way for More Competition?, The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD). Available at: https://unctad.org/en/PublicationsLibrary/osgdp2016d1_en.pdf (Accessed 21 March 2022).

Rai D. (2020). BREXIT and its Impact on India ( IP-Leaderes). India. Available at: https://blog.ipleaders.in/brexit-and-its-impact-on-india/.

Ramesh M. (2019). Why India Should Join the BRI ( The Hinistan Business Line). India. Available at: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/opinion/why-india-should-join-the-bri/article29635683.ece.

Read J. (2020). Brexit Set to Cost More Than UK’s Net Contribution to EU Over 47 Years (The New European). Available at: https://www.theneweuropean.co.uk/top-stories/brexit-to-cost-more-than-uk-paid-in-to-eu-1-6463383.

Singh A. G. (2020). The Standoff and China’s India Policy Dilemma ( The Hindu). India. Available at: https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/the-stand-off-and-chinas-india-policy-dilemma/article32083539.ece.

Sonwalkar P. (2020). With 120 Projects, Over 5k Jobs, India Now Second Biggest Investor in UK ( Hindustan Times). New Delhi. Available at: https://www.hindustantimes.com/india-news/with-120-projects-over-5k-jobs-india-now-second-biggest-investor-in-uk/story-Bh6ZMpbhkQdVCpilC79MmN.html.

Statista (2020) Foreign Direct Investment Equity Inflows to India in Financial Year 2020, by Leading Investing Country ( Statista). Available at: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1020989/india-fdi-equity-inflows-investing-countries/ (Accessed 25 September 2021).

Stebbings E., Papathanasopoulou E., Hooper T., Austen M. C., Yan X. (2020). The Marine Economy of the United Kingdom. Mar. Policy 116 (December 2019), 103905. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103905

Sullivan A. (2019). India, the EU and the Hard Realities of a Post-Brexit World (DW News). New Delhi. Available at: https://www.dw.com/en/india-the-eu-and-the-hard-realities-of-a-post-brexit-world/a-47126604.

Summers T. (2017). Brexit: Implications for EU–China Relations, Catham House (The Royal Institute of International Affairs). London. Available at: https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/publications/research/2017-05-11-brexit-eu-china-summers.pdf.

Swaine M. D. (2019). A Relationship Under Extreme Duress: U.S.-China Relations at a Crossroads (Carbegie Endowmwent for International Peace). Washington, DC.

The Economic Times (2017) UK Eyeing to be ‘Key Partner’ of CPEC Post-Brexit (The Economic Times). Available at: https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/international/business/uk-eyeing-to-be-key-partner-of-cpec-post-brexit/articleshow/58032277.cms?from=mdr (Accessed 19 August 2021).

The Express Tribune (2017) This Country’s Eyeing to Become Key Partner of CPEC (The Express Tribune). Available at: https://tribune.com.pk/story/1375504/britain-eyeing-become-key-partner-cpec (Accessed 19 August 2021).

The Gulf Today (2017) CPEC to Reduce Transportation Costs to Europe (Middle East, The Gulf Today). Available at: http://gulftoday.ae/portal/ba231f3b-2697-4f7f-aafc-75b93b7e2e28.aspx (Accessed 23 November 2021).

The Hindu Business Line (2020). India Among Top 10 FDI Recipients, Attracts $49 Billion Inflows in 2019: UN Report (The Hindu Business Line). New Delhi. Available at: https://www.thehindubusinessline.com/economy/india-among-top-10-fdi-recipients-attracts-49-billion-inflows-in-2019-un-report/article30608178.ece.

The Natnation (2020a) Cpec’s Modern Infrastructure can Attract UK’s Business Community in Post Brexit Trade Agreement (The Nation). Available at: https://nation.com.pk/03-Feb-2020/cpec-s-modern-infrastructure-can-attract-uk-s-business-community-in-post-brexit-trade-agreement (Accessed 18 August 2021).

The Natnation (2020b) Pakistan, UK Trade Volume in 2019 Remained £2,043m (The Nation). Available at: https://nation.com.pk/03-Mar-2020/pakistan-uk-trade-volume-in-2019-remained-pound-2-043m (Accessed 18 August 2021).

The News (2018). Pakistan Wants to Develop Gwadar as “Oil City” Under CPEC (The News). New Dehli. Available at: https://www.thenews.com.pk/latest/367102-pakistan-wants-to-develop-gwadar-as-oil-city-under-cpec.

The Print (2018). India, China Discuss Maritime Security, Cooperation (The Print). New Delhi. Available at: https://theprint.in/india/governance/india-china-discuss-maritime-security-cooperation/82844/.

The Value Walk (2017) CPEC And Pakistan’s Maritime Security [ANALYSIS] (The Value Walk). Available at: https://www.valuewalk.com/2017/10/cpec-maritime-security-pakistan/ (Accessed 9 December 2021).

Valentine H. (2017). Future India - China Container Transshipment Cooperation (The Maritime Executive). Available at: https://www.maritime-executive.com/editorials/future-india-china-container-transshipment-cooperation.

Walker A. (2018). Does the EU Need Us More Than We Need Them? (BBC News). Available at: https://www.bbc.com/news/business-46612362.

Whitfield K. (2020). Brexit Costs: How Much has Brexit Cost the UK? Is it More Than the EU Membership Bill? (The Express Tribune). United Kingdom. Available at: https://www.express.co.uk/news/politics/1235498/brexit-costs-so-far-how-much-has-brexit-cost-eu-membership-divorce-bill.

WMN (2017). UK Turns to China to Boost Maritime Ties Ahead of Brexit (World Maritime News). Available at: https://worldmaritimenews.com/archives/215676/uk-turns-to-china-to-boost-maritime-ties-ahead-of-brexit/.

Yu J. (2017). After Brexit: Risks and Opportunities to EU–China Relations (Global Policy), 109–114. doi: 10.1111/1758-5899.12440

Zhu Z. (2020). China is So Fixed on the US, it may Lose India (Aljazeera). Lewisburg, Pennsylvania. Available at: https://www.aljazeera.com/indepth/opinion/india-china-tensions-time-beijing-pivot-asia-200627103442232.html.

Keywords: Brexit, UK-Sino relations, port governance, 21st-Century Maritime Silk Road, Maritime cooperation

Citation: Khan MI, Lokhande S and Chang Y-C (2022) Brexit and its Impact on the Co-Operation Along with the 21st Century Maritime Silk Road—Assessment from Port Governance. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:906566. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.906566

Received: 28 March 2022; Accepted: 17 June 2022;

Published: 20 July 2022.

Edited by:

José Guerreiro, University of Lisbon, PortugalReviewed by:

Hui Shan Loh, Singapore University of Social Sciences, SingaporeCopyright © 2022 Khan, Lokhande and Chang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Mehran Idris Khan, TGZvbWRAaG90bWFpbC5jb20=

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.