- WMU-Sasakawa Global Institute, World Maritime University (WMU), Malmö, Sweden

Negotiations are currently underway into establishing a new international agreement under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction. This paper discusses some of the experiences and challenges faced by the Caribbean Community (CARICOM), a regional group of small island developing States, in the negotiation of this agreement. The group has been engaged as a bloc since the preparatory stage of the process. The process has now advanced well into an inter-governmental conference, which had an original mandate for four sessions, but will be extended for at least one more session in August 2022. CARICOM has managed to innovate, adapt and access and pool resources in order to be relevant and impactful participants throughout the ongoing negotiations and in face of the Covid-19 pandemic. Some suggestions are offered with a view to ensuring continued meaningful involvement of the group in the remainder of the negotiations, as well as in future ocean related multilateral processes.

Introduction

The 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), commonly referred to as the “constitution for the oceans”, was the result of nine years of formal intergovernmental negotiations; the longest in the history of the United Nations (Freestone, 2012). This monumental effort produced a comprehensive and far reaching instrument of international law, many aspects of which are now recognized as having ‘customary’ status (Roach, 2014). Since its adoption, some provisions in UNCLOS have been further developed through the use of implementing agreements, namely the 1994 Agreement relating to Part XI, and the 1995 UN Fish Stocks Agreement (Boyle, 2005). An intergovernmental conference (IGC) to establish a third implementing agreement under UNCLOS began in 2018. This conference was convened to develop the text of an agreement which focuses on the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction, otherwise known as the BBNJ agreement.

The intergovernmental conference to elaborate the text of the BBNJ agreement is the final stage in a long process of formal and informal efforts to develop this instrument (Long and Chaves, 2015; Tiller et al., 2019; Mendenhall et al., 2019; De Santo et al., 2020). Commenced under the auspices of the UN General Assembly in 2004 with the setting up of an ad hoc informal working group to study the issues relating to the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity of areas beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ Working Group), the process progressed through a Preparatory Committee (Prep Com) established through UN General Assembly Resolution 69/2921 and eventually to the IGC when Resolution 72/2492 was adopted in December 2017. The resolutions mandated that both the Prep Com and the IGC were open to all Member States of the UN, members of the specialized agencies and parties to UNCLOS. In addition, the participation of a range of observers, including NGOs, was facilitated through these resolutions.

The Caribbean Community (CARICOM) have been active participants in the BBNJ process, negotiating as a regional group since the Prep Com stages. CARICOM is an integration movement from the developing world comprising of 20 countries – 15 member States and 5 associate members (O'Brien, 2011). Integration rests on four main pillars: economic; security; human and social development; and foreign policy co-ordination. In the BBNJ negotiations, when a member State of the group takes the floor, it almost always does so on behalf of 14 independent nations. These countries, who are all considered to be small island developing States (SIDS) by the UN, are Antigua and Barbuda, Bahamas, Barbados, Belize, Dominica, Grenada, Guyana, Haiti, Jamaica, St Kitts and Nevis, St Lucia, St Vincent and the Grenadines, Suriname and Trinidad and Tobago. The 15th member State of CARICOM, Montserrat, is not spoken for because it is an overseas territory of the United Kingdom.

In the field of international relations there has long been interest in how small States, especially developing ones, assert themselves and influence multilateral processes (Ingebritsen et al., 2012). It is generally accepted that small developing States start at a disadvantage in international negotiations because of the fewer available administrative and financial resources (Panke, 2012a). Payne (2004) proffers that the participation of such States in global politics is more often characterized by their expressing vulnerabilities to potential changes that may result from issues under consideration e.g. de Águeda Corneloup and Mol (2014), rather than, at the foremost, exercising the opportunity to affirm their broader interests. But research suggests that small States do impose themselves in international negotiations through the use of capacity-building strategies; to improve how they perform in diplomatic arenas, and shaping strategies; to become more persuasive and thus better influence outcomes (Panke, 2012b). All things being equal, small States seem to fare better in negotiations under the auspices of multilateral institutions where transaction costs are lower; there are set rules of procedure; power asymmetries are less pronounced e.g. consensus based decision-making is practiced; and coalitions can be more easily shaped and realized (Thorhallsson and Steinsson, 2017).

This paper adds to the literature on small States in international negotiations. Of focus is CARICOM’s participation in the BBNJ negotiations. In examining the involvement of this group of SIDS it draws on the experiences of the author, who is CARICOM negotiator in the process and the lead on the environmental impact assessment strand of the draft agreement. This is complemented with insights from group’s other negotiators which were garnered through semi-structured interviews. The paper documents the experiences and challenges encountered as the group has interfaced with the BBNJ process and offers details as to how it has adapted to remain an effective contributor. Discussed in the forthcoming sections will be stakeholder engagement in formulating negotiating positions, engaging and utilizing regional experts in the negotiations, CARICOM’s exercising of “institutional windows of opportunity”, and the impact of the Coivd-19 pandemic. In the closing discussion some suggestions are also offered as to how CARICOM may equip itself to be a more influential and active group in this and other multilateral ocean related processes in the future.

Collective Regional Ocean Visioning and Garnering Stakeholder Input

It is well recognized and acknowledged that Caribbean SIDS exhibit a substantial economic, social and cultural connection to and dependence on the ocean and its resources (Clegg et al., 2020). Indeed, within recent years; since blue economy ideologies emerging out of the United Nations Conference on Sustainable Development (Rio +20) have been mainstreamed into SIDS’ development policy discourses (Silver et al., 2015), individual CARICOM countries have been at the forefront of thrusts towards strategic development of the sustainable ocean economy. A number of detailed plans, policies and/or scoping documents have since emanated out of CARICOM nations including, for example, Grenada (Patil and Diez, 2016), Barbados (Roberts et al., 2020), Dominica (Roberts, 2019) and Belize (Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute (CZMAI), 2016).

Within CARICOM as a whole however, blue economy development is not coordinated to the extent that it should be. While the Organization of Eastern Caribbean States (OECS), which is made up primarily of a subset of CARICOM members, does have a regional ocean policy (OECS, 2020), there exists no agreed regional vision for Member States of CARICOM to collectively align their ocean development endeavors to and few formal mechanisms existing for collaborative ocean management at this larger scale (Hassanali, 2020). This is despite there long having been calls for such within the organization (Blake, 1998), but which never materialized in the face of limited resources and competing priorities. In the absence of a regionally considered and developed vision, along with a guiding document detailing ocean management priorities and objectives, the CARICOM negotiating bloc entered the BBNJ negotiations with a handicap and in some respects ill prepared to maximize the outcomes for the welfare and benefits of their peoples. This stands in contrast to the European Union (EU) for instance, who could be guided by the EU Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) and several other endogenous ocean related instruments. With this groundwork already done, this delegation was therefore better equipped and positioned to fully consider how what is contained therein, and the architecture developed as a result, related to the BBNJ discussions (Long and Brincat, 2019; Ricard, 2020).

Developing and executing a regional vision necessitates, inter alia, having a coordinating mechanism which includes multiple established fora for encouraging widespread, genuine stakeholder interaction and input (Fanning et al., 2021). A paucity of these have also impeded CARICOM’s engagement in the BBNJ negotiations in the sense that there has been limited domestic stakeholder knowledge and interest about the process, its purpose and potential implications. Concomitantly, in crafting its negotiating strategies, CARICOM has not fully tapped in to and benefitted from the expansive pool of knowledge and perspectives – traditional, contemporary and otherwise (Raymond et al., 2010; Mulalap et al., 2020; Tessnow-von Wysocki and Vadrot, 2020) – that the group potentially has at its disposal.

As the BBNJ negotiations progressed through the Prep Com into the IGC stages, this limitation was recognized. Consequently, through a grant provided by the Oak Foundation, CARICOM embarked on a stakeholder engagement process that targeted government agencies, civil society, private sector, regional agencies, academia and private individuals and resource users, among others. National workshops held in Guyana, Jamaica and Trinidad and Tobago were complemented by a number of key informant interviews and a more, far-reaching online survey. Through this engagement process CARICOM was able to distil 10 regional priorities from the elicited perspectives and these have been used to inform ongoing negotiations in the IGC3. The priorities were indeed a good starting point but would have benefited from ongoing, deeper and more nuanced discussions among the relevant stakeholders. Therefore, while the process and its results have proven to be important and instructive for CARICOM negotiators, its one-off, ad hoc nature is no substitute for a more robust and enduring system of stakeholder engagement on ocean related matters for the regional group.

Engaging and Developing Regional Expertise

Of course, an important faction that need to be perpetually engaged for the purposes of effective BBNJ agreement negotiations are those with professional and high-level technical expertise in ocean related fields. They are needed to complement and support the New York based diplomats at the seat of their Permanent Missions at the UN who, themselves, are not expected to be subject matter experts in the topics being discussed, especially in specialist fields such as the law of the sea. Fortunately, emerging from and/or practicing in a number of regional organizations; national bodies, agencies and Ministries; and higher-level education and research institutions, CARICOM has a cadre of professionals in a range of disciplines pertaining to biodiversity, oceans and marine management (Mahon and Fanning, 2021). That being said, while many of the skills and bodies of knowledge that these experts possess are transferable to ABNJ contexts, specific expertise dealing with BBNJ is more limited as CARICOM nations are constrained by capacity and resources in undertaking activities outside of their national jurisdictions (Cicin-Sain et al., 2018; Harden-Davies et al., 2020; Harden-Davies et al., 2022).

At the same time, while ocean experts can be found within CARICOM, it is fair to say that they are not ubiquitous – there is still a limited pool to draw from (Harden-Davies et al., 2020). Experts who are best equipped to advise in the exceedingly technical BBNJ negotiations also generally find themselves saddled with many other responsibilities. They often hold highly demanding positions and may be consequently, overworked and/or time-strapped. Incidentally, these are traits also observed in New York based negotiators, an issue that will be touched upon later. However, these characteristics of CARICOM ocean experts present a challenge to having them contribute in the BBNJ process through their offering of guidance and technical advice to negotiators. CARICOM has recognized that to be most effective, it is imperative that the diplomatic and international relations skills and understanding of the CARICOM negotiators are paired with the specialist knowledge of the regional ocean experts. The group therefore had to devise effective and feasible means to elicit expert advice and engagement to bolster the bloc’s participation in the negotiations.

Key to eliciting expert advice has been the hosting of regional workshops which brought negotiators, capital-based experts and foreign experts together to facilitate learning and dialogue. International non-governmental organizations, primarily Pew Charitable Trusts in this case, were integral in funding these workshops. Up to the time of writing, four separate events were convened. Two took place in Belize City, Belize in February 2017 and July 2018, just before the 3rd Prep Com session and 1st session of the IGC respectively. A third regional workshop was hosted by Barbados in July 2019 prior to the 3rd IGC session and a fourth hybrid regional workshop was hosted in Tarrytown, New York just prior to the most recent IGC session in March 2022. These three-day workshops allowed participants to have uninterrupted, dedicated time and focus on matters pertaining to the BBNJ negotiations. Additionally, in what is shaping into a burgeoning, meaningful partnership (Harden-Davies et al., 2022), Pew is also currently funding a BBNJ capacity building initiative related to area-based management tools and environmental impact assessments, aimed at further enhancing CARICOM’s understanding of the issues and capacity constraints in implementing potential obligations.

It can be said that the workshops successfully aided in building regional capacity and knowledge through interaction with international experts situated within the BBNJ epistemic communities. Crucially, the workshops also allowed the negotiators and regional and international experts to build and strengthen personal connections. An enduring legacy has been the formation of a regional team of experts to act as a devoted advisory group with formal and informal communication channels between themselves and negotiators. In addition, regional experts and negotiators were given time and space to concentrate on contextualizing the BBNJ agreement in light of CARICOM’s needs and wants and to develop regional strategy including consideration of ‘red lines’ – issues on which the region would not yield on its bottom-line position. An important point to note about the collaborations that have taken place with the external donors is that conditionalities on their funding have not been imposed. CARICOM has rightfully been allowed to be independent and self-determining in the decisions they take with regard to the BBNJ negotiations and positions adopted.

Involving Capital-Based Experts at the Negotiating Sessions

At its annual meetings since 2015, the Council for Foreign and Community Relations (COFCOR), which is comprised of the Ministers of Foreign Affairs from the CARICOM Member States, have discussed, monitored developments in, and made recommendations with regard to CARICOM’s engagement in the BBNJ process. Subsequent to the establishment of the advisory group of experts, COFCOR has continually called on Member States to ensure that these experts are included on national delegations for the negotiation sessions at the UN in New York. It is recognized that the presence of experts on location is needed to provide timely, relevant advice to lead negotiators. In addition, their presence in-person allows them to get a genuine sense of the negotiating atmosphere thus better facilitating the provision of the most appropriate and sophisticated guidance.

The physical presence of capital-based experts in the negotiating rooms in New York also has other vital benefits, most notably, adding to the human resources available to the CARICOM delegation and thereby facilitating more complete coverage of all aspects of the negotiations. CARICOM countries, being small, developing States with limited resources, do not have large Missions to the UN (Ó Súilleabháin, 2014). Consequently, foreign service officers stationed at the UN Missions of CARICOM States are tasked with the responsibility of covering multiple processes and committees which often occur in tandem; a workload that is extremely demanding. Given resource constraints, no CARICOM State, acting alone, would be able to adequately and effectively cover the BBNJ process. CARICOM States acting as a unit have strategized, dividing the BBNJ negotiation workload and having different countries lead on the various elements of the package.

It must be noted that if one were to look at the final lists of participants for the negotiating sessions it would appear that the CARICOM collective have had very sizeable delegations. However, these lists must be considered with caution as CARICOM countries tend to put all senior officers at their UN Missions on the participant’s list, but the reality is the vast majority are not involved in the proceedings. Even with combined efforts, having the critical mass of (wo)man-power available to ensure that CARICOM is present, completely following and comprehensively analyzing the proceedings that are occurring in the negotiating rooms is still a challenge especially with the gradual stepping up in intensity of deliberations as the process has progressed. In the 3rd IGC session the format of the negotiations shifted to one where parallel ‘informal’ and ‘informal-informal’ meetings were taking place in separate rooms (International Institute for Sustainable Development, 2019; De Santo et al., 2020). This necessitated a further division of human resources for the CARICOM negotiating team. The March 2022 4th IGC session had to be significantly scaled down and restricted due to Covid-19 safety protocols4. For the future IGC session(s) however, it is imperative for CARICOM to have a larger, more diverse delegation, inclusive of as many experts as possible as modalities are expected to return to normal.

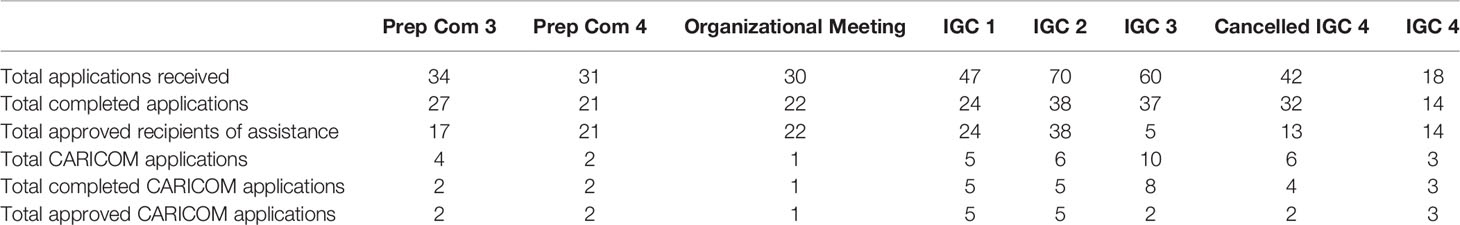

For developing countries, including the SIDS of CARICOM, the costs involved in getting experts to New York along with the associated accommodation and other living expenses for a two-week negotiation period, can be especially prohibitive. To address this challenge, the UN General Assembly in its resolution 69/292, authorized the establishment of a special voluntary trust fund to facilitate participation of capital-based delegates from the developing world, and in particular, least developed countries, land-locked developing countries and SIDS. Resolution 72/249 renewed the mandate of this trust fund for the IGC. For both the Prep Com and IGC this trust fund defrayed the cost of travel and provided daily subsistence allowances for those who successfully applied. The trust fund has not been a guaranteed source of funding however. It is resourced solely through voluntary contributions, and thus depends on the benevolence of UN Member States; international financial institutions, donor agencies, intergovernmental organizations, NGOs and natural and juridical persons. There have been points when the funding available has lagged behind the demand for assistance. There were not sufficient funds deposited into the trust fund to service the first two sessions of the Prep Com and the problem of not enough available resources to meet demand became particularly acute again in the more recent sessions of the BBNJ process (Table 1).

Table 1 BBNJ Voluntary Trust Fund applications and recipients of assistance including as relates to CARICOM.

CARICOM has benefitted from trust fund assistance (Table 1). However, two points are noteworthy with regard to the statistics. Firstly, it appears that CARICOM has been underutilizing the trust fund facility. With fourteen States under the group and funding theoretically available for one participant from each State, the number of applications from CARICOM to the fund has been underwhelming. It may be related to the fact that capital based experts, for reasons alluded to earlier, find it difficult to commit to two weeks away from their substantive portfolios. The second point of note is that the total number of completed applications from CARICOM is a moot one if there are not enough funds available to facilitate participation as was the case in the first two Prep Coms, the 3rd IGC session, and which would have been the case for the cancelled 4th session in March 2020. Overall, the Fund has proven to be an uncertain source of assistance and therefore not an entirely satisfactory mechanism to support delegations from the global south attending the BBNJ meetings. Indeed, throughout the BBNJ process CARICOM has constantly appealed for better resourcing of the Trust Fund. For example, in its statement delivered at the closing of the 3rd IGC session CARICOM appealed for more assistance in saying: “CARICOM therefore remains extremely concerned about the state of the Voluntary Trust Fund. We believe that adequate funding of the Trust Fund will be required if we are to actively engage in the upcoming negotiations and meet our goal of completing these negotiations by 2020. We therefore urge States and others who are in a position to contribute to the Fund, to do so.”

Caricom in Organizational Positions of Importance

In discussing how small States make their voices heard in international negotiations, Panke (2012b); p. 322) highlights the use of “institutional windows of opportunities such as being the Chair of meetings or holding the office of the Presidency to increase the influence via arguing, framing, bargaining or value-claiming positions”. Schulz et al. (2017) provide examples of this use of entrepreneurial leadership in regard to Switzerland’s role in negotiations of the Cartagena and Nagoya Protocols to the Convention on Biological Diversity. In the BBNJ negotiations CARICOM has also been availed of “institutional windows of opportunities” which has allowed the group to exercise further influence.

A fitting example of this is with respect to CARICOM ensuring that one of its member countries obtained a position on the Bureau for the IGC. The Bureau of the IGC is made of 15 countries who are then Vice Presidents to the Conference and, in particular, assist the President on procedural matters in the general conduct of the President’s work. In-keeping with this mandate the Bureau has been consulted by the President throughout the IGC. It consists of three countries from each of the five geopolitical regional groups of the United Nations – the African Group, Asia-Pacific Group, Eastern European Group, Latin American and Caribbean Group, and Western European and other Group. CARICOM countries fall within the Latin American and Caribbean Group (GRULAC).

In the Prep Com, as per paragraph 1(e) of UN General Assembly Resolution 69/292, the Bureau was limited to two members from each regional group. The Caribbean had no representative on the Bureau during this stage of negotiations with Latin American and South American countries from GRULAC assuming the roles (Costa Rica and Chile for the 1st and 2nd Prep Coms; Argentina and Mexico for the 3rd and 4th Prep Coms). With increased Bureau membership in the IGC, CARICOM felt that it would naturally follow that a Caribbean country from GRULAC would then be afforded the opportunity to serve as a Vice President to the Conference. However, CARICOM was met with resistance from within GRULAC, with some States of the opinion that a Caribbean country’s place was not automatically a given.

Therefore, unlike the other four UN regional groups, the representatives of GRULAC to serve on the Bureau of the IGC were not elected by acclamation on the first day of the 1st IGC session. Rather, these members were elected a couple of days later by secret ballot among all States participating in the Conference. The fact that the decision had to come to a vote was a source of consternation among some Conference participants. The feeling was that it set the wrong tone for the IGC especially given the fact that decisions in the Conference were to be made, as far as possible, by consensus. At the conclusion of the voting, CARICOM’s choice, the Bahamas, earned a place on the Bureau alongside Mexico and Brazil from GRULAC, Algeria, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, China, Japan, Mauritius, the Federated States of Micronesia, Morocco, Poland, the Russian Federation and the United States of America. For CARICOM, this position has been important particularly in having direct input in when the sessions of the IGC are organized and how they are structured.

Apart from the Bahamas being a Vice President to the IGC, Trinidad and Tobago’s Ambassador Eden Charles has also served as Chair of the Prep Com for the first two sessions. The Chair was appointed by the President of the UN General Assembly after that office held informal consultations with a number of groups and delegations participating in the process and found there was broad support for the Trinidad and Tobago Ambassador to be chosen. In his position as Chair, among other things, he conceptualized and developed the model for the negotiations in respect of having informal working groups on the different elements of the package, and also identified suitable candidates to serve as facilitators of these working groups. This model for the negotiations has persisted into the IGC. After the 2nd Prep Com session however, in what was a sovereign national decision, Ambassador Charles was recalled to capital thereby ending his tour at the UN. This decision, which culminated in him having to give up this prestigious position in the negotiations, probably did not aid CARICOM’s standing in the BBNJ process. As a result of the reshuffling that took place due to his departure however, another CARICOM national, Ambassador Janine Coye-Felson, was appointed to serve as the Facilitator for the Informal Working Group on Marine Genetic Resources (MGRs). She has competently served in this position, which deals with the most intractable and difficult aspect of the negotiations, from Prep Com 3 onwards.

In the BBNJ process, when persons are appointed to positions such as President, Chair and Facilitator of a working group they have earned these posts due to having established reputations of being highly astute, impartial and fair. They are expected to perform their duties without view to furtherance of national (or regional) positions in negotiations and in doing so are integral to success in consensus based negotiations (Buzan, 1981). For CARICOM, having nationals from the region in these positions of authority increase the stature, prominence and legitimacy of the bloc and also brings with it the added benefit of having access to persons with ‘insider knowledge’ and a thorough grasp of all the issues at play in different aspects of the negotiations. There is a trade-off however, as these positions also bring with it the drawback of not having available to the group its most seasoned and effective negotiators in real time. This is especially the case when sessions are being held in parallel. The situation therefore adds to the challenge faced by a group already strapped for human resources.

Finally, as it relates to CARICOM countries in influential positions, it must be noted that Guyana was the Chair of G77 + China in 2020, Belize the Chair of the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) from 2019-2020 and Antigua and Barbuda the Chair of AOSIS in 2021-2022. Guyana’s position as the G77 + China Chair coincided with a break in formal negotiations, of which more will be said on later. As a result, it was probably not as impactful from a CARICOM BBNJ perspective as it could have been if the IGC was being held. With regard to Belize’s time as AOSIS Chair, a tangible outcome was the commissioning and production of an insightful report on capacity challenges and options relating to MGR research (and marine scientific research more generally) in SIDS and as it relates to areas beyond national jurisdiction (Harden-Davies et al., 2020). Fellow CARICOM member States were indeed very supportive of their sister countries as they executed their roles as Chairs of these large groups. However, in the future, the CARICOM bloc may better strategize in order to further leverage opportunities that could arise from members holding these positions including in the building of cross-regional alliances and tabling of joint proposals on the key contentious issues under negotiation.

The Influence of the Covid-19 Pandemic

A couple of weeks before the fourth IGC session was scheduled to take place in March 2020, the UN General Assembly took the decision to postpone it due to the emerging threat of the Covid-19 disease5. Indeed, few would disagree that to host an international negotiation process during a time when the virus was an epidemic in many parts of the world and with global pandemic looming, would have been logistically impossible and ethically reprehensible. Subsequent to the postponement decision, new dates were scheduled for the session but these targets were unable to be met as the pandemic was not brought under control soon enough. After two years of postponement, the 4th IGC session eventually took place in March 2022. In the lengthy intervening period between IGC3 and IGC4 however, informal work and discussions were ongoing through a shift to virtual interaction and adopted modalities of operation using online networking platforms such as Zoom, Cisco Webx and Microsoft Teams (Vadrot et al., 2021).

The pandemic was beneficial to the negotiation process in the sense that it allowed additional time to reflect on the many outstanding issues in the negotiations (Tsioumanis, 2020), and, in that regard, seeking to generate more dialogue towards consensus. Two main multilateral and multi-stakeholder fora were established to have this occur. The President of the Conference, H.E. Ambassador Rena Lee from Singapore, supported by the Division of Ocean Affairs and Law of the Sea (DOALOS), organized intersessional work through an online forum which ran from September 2020 to March 2021. Participants discussed and proposed ideas in response to various questions posed on elements of the negotiations. This was complemented by the ‘High Seas Treaty Intersessional Dialogues’ which were hosted jointly by the Kingdom of Belgium, the Principality of Monaco and Costa Rica in collaboration with other organizing partners. These dialogues were conversational, held in a video conference format as opposed to the written interaction modality of the intersessional work organized by the President. They commenced in July 2020 and sessions were held regularly, each time focusing on different pre-specified topics and areas of interest6. Apart from participating in these multilateral interactive platforms, CARICOM also engaged in bilateral discussions with other delegations virtually. These too were helpful in getting CARICOM interests known, learning the interests of other delegations and proposing issue linkages and compromises towards common interests.

There were few barriers to participation in these virtual intersessional events; all that was required was a reliable internet connection and communicating to the organizers an interest to participate. Transaction costs were therefore low especially when considering that in-person intersessional meetings in different parts of the world would have required a considerably larger budget to fund travel and other expenses. The virtual intersessionals resulting from postponement due to the pandemic therefore, theoretically, allowed for increased opportunity for participation by CARICOM negotiators and interested experts. However, at the same time, the pandemic also saw a proliferation of online engagements as work modes migrated to virtual spaces, people became more familiar with the available technologies and their use, and meetings became easier to organize and coordinate. This, in turn, led to inundation of members of the CARICOM BBNJ delegation, who, as alluded to earlier, are tasked with numerous roles and responsibilities apart from the BBNJ process in their professional capacities. They therefore had to be selective in where to direct attention. It follows then that enhanced opportunity to participate in BBNJ discussions did not always necessarily translate into enhanced ability to participate.

Two final points need to be made on the influence of the Covid-19 pandemic on CARICOM’s engagement with the BBNJ process. Firstly, during the delay and postponement of formal negotiations the regional group saw the departure of experienced negotiators, with vast institutional knowledge of the BBNJ process and, among other things, well-honed networks of alliances with other delegations. Continuity and momentum in advancing the CARICOM group’s positions were affected as they either have not been replaced or as incoming delegates transitioned into their new roles and under difficult circumstances. Secondly, the Covid-19 pandemic brought with it physical, mental and emotional challenges both within and outside the professional sphere (Pedrosa et al., 2020). These came along with the sudden and drastic departure from the usual learnt and accepted practices of societal engagement and lifestyle changes that resulted. In commenting upon the influence of the pandemic on CARICOM’s delegation as a whole, the impact that was had at personal, individual levels must fully acknowledged and not understated.

Discussion and Recommendations

Based on the Virginia Commentary7 (Nordquist et al., 1985) it appears that CARICOM States did not approach negotiations in the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS III), which ran from 1973 to 1982 and yielded the Law of the Sea Convention as we know it today, as a negotiating bloc. Indeed, Carnegie (1987) has commented that CARICOM countries did not exercise much influence within the Group of 77, who played a major role in those negotiations on behalf of developing countries. Several authors have made the point that interest groups, rather that regional groups, were more impactful at the UNCLOS III negotiations8 (Buzan, 1980; Koh, 1983). Some CARICOM member States were prominent in those interest groups e.g. Bahamas in the negotiation of the archipelagic State regime (Andrew, 1978), but there was not a regionally strategized approach. In the present day BBNJ negotiations however, there has been a shift. Many regional groups are active and influential including the Pacific Small Island States (PSIDS), the African Group (AG), the European Union (EU), the Core Latin American Countries (CLAM) and CARICOM. This reflects what has been a growing trend of regionalization of international negotiations (Panke et al., 2017).

Undeterred by postponement of formal proceedings due to the pandemic, the BBNJ process has been ongoing. CARICOM was enthusiastically engaged before and during the interruption and continued to be prominent when the IGC officially resumed. To date, despite considerable challenges, the group have delivered well-articulated positions on all the substantive issues and articles under discussion, at every session and setting, be it plenary, informal working groups, ‘informal-informals’ and virtual intersessional dialogues. Spurred by internal impetus and with the help of external donors, the CARICOM delegation have adapted and persevered through the difficult and complex circumstances of the most important law of the sea negotiations in the past 25 years. In thinking through developing and delivering a common strategy there has been evidence of increased stakeholder engagement, accessing and networking with experts and the sharing of workloads. That being said, although improvised, interim solutions have been sought, most challenges are still to be adequately overcome in a long-term, sustainable way. The group has also been negatively affected by the periodic turnover of negotiators during the process. Added to this, the challenge of securing reliable, predictable funding to have a critical mass of capital-based delegates physically participate in the remaining negotiation session(s), has proved intractable, even in the short term, and still needs immediate redress.

CARICOM has negotiated as a bloc in other international processes which focus on different policy areas such as trade and security. It has been observed that many of group’s challenges highlighted in this paper are not uniquely experienced in the BBNJ process (Lewis, 2005; Joseph, 2013). A common thread, regardless of the forum or area of interest, is a lack of human and financial resources which inhibits the achievement of the most optimal results from the region’s perspective. This is in-keeping with observations in the published literature on small States even though CARICOM represents a group of small States which have pooled resources (Panke, 2012a). Amalgamation of resources by CARICOM member States in the BBNJ negotiations has proven to be an astute and judicious approach. Although it is not entirely perfected, the group should continue to pursue this path in the future. At the conclusion of these negotiations it would be important for further, comprehensive analysis of CARICOM’s engagement to take place, considering what was desired and juxtaposing this against the eventual outcomes. This would not only help determine the pros and cons of CARICOM member States signing the final BBNJ agreement but could also help to prioritize and action improvements and innovation in the way the group participates in and influences future multilateral negotiation processes, be they ocean related or otherwise. As it pertains future engagement in the ocean realm however, based on what has been observed in the BBNJ negotiations thus far, a few recommendations can be made.

Firstly, the creation of and commitment to a formal and functional regional mechanism to contemplate, coordinate and execute a collaborative approach to developing and achieving an agreed vision on ocean related development is imperative for CARICOM member States. Such an arrangement could increase public knowledge about sustainable ocean management and generate interest, input and desire towards realizing it. This may not only succeed in elevating ocean related issues on the political agenda within CARICOM, it may also produce more legitimate recommendations for negotiators to pursue and robust outcomes at national, regional and global levels. Additionally, an enduring coordination mechanism can help in developing and soliciting expert advice and strengthen the region’s standing as an authority on ocean related issues. Therefore, it is crucial that activities and pursuits of the envisioned coordination mechanism are perpetually ongoing even after a clearly articulated overarching policy, which would outlines long term vision, guiding principles and objectives with regard to sustainable development of the ocean spaces, is collaboratively arrived at by all members and relevant stakeholders within the CARICOM regional arrangement.

Secondly, within the contexts of the institutional architecture that would be created to govern BBNJ, CARICOM should push for the inclusion in the agreement of a special fund to, inter alia, help developing countries participate in the Conference of Parties and other bodies that would be established. Article 52(4) of the revised draft text of the BBNJ agreement which was prepared by the President of the IGC in November 20199, does refer to such a fund, but it proposes that it will be a voluntary trust fund, similar to that which currently pertains to aid developing State participation in the negotiations towards the agreement. This paper has already highlighted that the voluntary nature of the existing Fund makes it less than effective in meeting the needs of developing States. CARICOM, in coalition with like-minded delegations, should therefore lobby for the fund under Article 52(4) to be mandatorily resourced in order to ensure that developing State Parties, including those from CARICOM, continue to have a meaningful say in how BBNJ is managed after the agreement is signed and enters into force.

Thirdly, given the ocean’s importance to economic, social and cultural fortunes of the region (Clegg et al., 2020), CARICOM may want to consider creating a post within the organization of Ambassador for the Ocean. Countries such as Belgium and Sweden have recognized and influential international diplomatic representatives devoted to the ocean but this would be a novel idea within a regional group and indeed, for CARICOM. This specialist portfolio Ambassador would not supplant Member States’ Ambassadors at international fora but rather could support them, aiding in intra-regional coordination and helping the group arrive at internal consensus as it relates to oceans. In addition, this person could represent the Community’s interests internationally on an ongoing basis, increase the region’s visibility and influence, and strengthen bilateral cooperation with partners. Diplomatic outreach by the Ocean Ambassador to governments, private sector and non-governmental interests could create abiding alliances with entities who are interested in maximizing CARICOM’s ocean potential and realizing its ocean vision, including through being a strong presence at international processes. The CARICOM Ambassador for the Ocean should be supported by a dedicated team within the CARICOM Secretariat. At present ocean matters fall under the programme area on sustainable development. However, the human and financial resources directed towards this important programme area are not sufficient to effectively meet the needs of its broad ambit. Therefore, along with a CARICOM Ambassador for the Ocean, a dedicated, adequately resourced ocean desk under the sustainable development programme of the Secretariat would also be important.

Fourthly, the interest and support provided by COFCOR for the CARICOM group engagement in the BBNJ process has indeed been helpful. In this and future negotiations, other reflections of political support could further enhance CARICOM’s influence and redound to the group’s benefit. Increased presence of Ministers and other high ranking officials from the region at sessions could send a strong message about the importance of the ocean to the region. Ministerial presence, including their making statements in plenary and engaging in bilateral talks on the margins, should therefore be employed more fervently in the future. More immediately, with the BBNJ negotiations at a critical point, the opportunity must be seized at every juncture on the international stage for CARICOM Ministers and senior spokespersons to highlight the importance to the region of securing a fair, equitable agreement without undue delay. A case in point relates to the high profile taken by Canadian Minister Tobin at the Fish Stocks Conference in 1995 to secure favorable outcomes to Canada (Curran and Long, 1996).

Finalizing the BBNJ agreement would represent one of the most significant milestones in ocean multilateralism for almost three decades. CARICOM has been a diligent participant in the process thus far, lobbying for its regional interests and the special circumstances of SIDS all within the context of sustainable and equitable use of the ocean and its resources. The group has been noticeably vocal on, inter alia, equitable benefit sharing arising out of utilization of marine genetic resources from areas beyond national jurisdiction, ‘internationalization’ of the EIA process (Hassanali, 2021), and securing predictable, accessible and adequate funding for capacity building and technology transfer (Harden-Davies et al., 2022). The BBNJ process has also presented the opportunity for the regional group to adapt, retool, grow and evolve in order to remain relevant and impactful into the future. Having the region’s interests robustly reflected in the final agreement and strengthening the regional approach to international negotiation are two equally important, and mutually beneficial, outcomes which CARICOM should be focused on achieving.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by World Maritime University Ethics Committee. Thepatients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

The author confirms being the sole contributor of this work and has approved it for publication.

Conflict of Interest

The author speaks on behalf of CARICOM in the BBNJ negotiations, but has written this article in an exclusively personal capacity.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

This article is part of a PhD research project under the “Land-to-Ocean Leadership Programme” at the World Maritime University (WMU) – Sasakawa Global Ocean Institute, Malmö, Sweden. The author would like to acknowledge the generous funding of the Institute by The Nippon Foundation, as well as the financial support of the Programme provided by the Swedish Agency for Marine and Water Management (SwAM) and the German Federal Ministry of Transport and Digital Infrastructure. Sincere gratitude is also extended to Ronan Long, Meinhard Doelle and the reviewers for their helpful comments and insights that improved the manuscript.

Footnotes

- ^ UN General Assembly resolution 69/292: https://undocs.org/en/a/res/69/292 (accessed: 18th June 2021)

- ^ UN General Assembly resolution 72/249: https://undocs.org/en/a/res/72/249 (accessed: 18th June 2021)

- ^ The priorities included: 1. Recognition of the importance of high seas biodiversity; 2. Need for funding/financing; 3. Stakeholder involvement; 4. Capacity building; 5. Equitable access and benefit sharing; 6. Data access; 7. Defining jurisdictions; 8. Sufficient monitoring; 9. Compliance frameworks; and 10. Multi-tiered decision making based on best available science. More details on the CARICOM BBNJ stakeholder engagement project can be found at: https://canari.org/bbnj-consultations/ (accessed: 8th June 2021).

- ^ Letter from the President of IGC concerning the 4th session of the Conference: https://www.un.org/bbnj/sites/www.un.org.bbnj/files/president_letter_to_delegations_february_2022.pdf (accessed: 15th February 2022)

- ^ UN General Assembly decision regarding the postponement of the 4th IGC session: https://undocs.org/en/a/74/l.41 (accessed: 5th July 2021)

- ^ More information on the High Seas Treaty Intersessional Dialogues can be found at: https://highseasdialogues.org/ (accessed: 6th July 2021)

- ^ The seven volume “Virginia Commentary” is based on the formal and informal documentation of UNCLOS III coupled, where necessary, with the personal knowledge of editors, contributors, or reviewers, many of whom were principal negotiators or UN personnel who participated in the Conference.

- ^ Tommy Koh, President of the final sessions of UNCLOS III did highlight the Latin American Group as being a unified and effective negotiating bloc in that conference however (Koh in Nordquist et al., 1985).

- ^ Revised draft text of the BBNJ agreement (November 2019): https://undocs.org/en/a/conf.232/2020/3 (accessed: 12th July 2021)

References

Andrew D. (1978). Archipelagos and the Law of the Sea: Island Straits States or Island-Studded Sea Space? Mar. Policy 2 (1), 46–64. doi: 10.1016/0308-597X(78)90060-X

Blake B. (1998). A Strategy for Cooperation in Sustainable Oceans Management and Development, Commonwealth Caribbean. Mar. Policy 22 (6), 505–513. doi: 10.1016/S0308-597X(98)00025-6

Boyle A. (2005). Further Development of the Law of the Sea Convention: Mechanisms for Change. Int. Comp. Law Q. 54 (3), 563–584. doi: 10.1093/iclq/lei018

Buzan B. (1980). ‘United We Stand…’: Informal Negotiating Groups at UNCLOS III. Mar. Policy 4 (3), 183–204. doi: 10.1016/0308-597X(80)90053-6

Buzan B. (1981). Negotiating by Consensus: Developments in Technique at the United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea. Am. J. Int. Law 75 (2), 324–348. doi: 10.2307/2201255

Carnegie A. R. (1987). The Law of the Sea: Commonwealth Caribbean Perspectives. Soc. Economic Stud. 36 (3), 99–117.

Cicin-Sain B., Vierros M., Balgos M., Maxwell A., Kurz M., Farmer T. (2018). Policy Brief on Capacity Development as a Key Aspect of a New International Agreement on Marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) (Washington DC: FAO, GEF, GOF, Common Oceans, University of Delaware).

Clegg P., Mahon R., McConney P., and Oxenford H. A. (Eds.) (2020). The Caribbean Blue Economy (Oxfordshire, UK: Routledge).

Coastal Zone Management Authority and Institute (CZMAI). (2016). Belize Integrated Coastal Zone Management Plan (Belize City, Belize: CZMAI). Available at: https://www.coastalzonebelize.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/BELIZE-Integrated-Coastal-Zone-Management-Plan.pdf (Accessed June 8th 2021).

Curran P. A., Long R. J. (1996). Fishery Law, Unilateral Enforcement in International Waters: The Case of the Estai. Irish J. Eur. L 5, 123.

de Águeda Corneloup I., Mol A. P. (2014). Small Island Developing States and International Climate Change Negotiations: The Power of Moral “Leadership”. Int. Environ. Agreements: Politics Law Economics 14 (3), 281–297. doi: 10.1007/s10784-013-9227-0

De Santo E. M., Mendenhall E., Nyman E., Tiller R. (2020). Stuck in the Middle With You (and Not Much Time Left): The Third Intergovernmental Conference on Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction. Mar. Policy 117, 103957. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.103957

Fanning L., Mahon R., Compton S., Corbin C., Debels P., Haughton M., et al. (2021). Challenges to Implementing Regional Ocean Governance in the Wider Caribbean Region. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 286. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.667273

Freestone D. (2012). The Law of the Sea Convention at 30: Successes, Challenges and New Agendas. Int. J. Mar. Coast. Law 27 (4), 675–682. doi: 10.1163/15718085-12341262

Harden-Davies H., Amon D. J., Chung T. R., Gobin J., Hanich Q., Hassanali K., et al. (2022). How can a New UN Ocean Treaty Change the Course of Capacity Building? Aquat. Conservation: Mar. Freshw. Ecosyst. 907–912. doi: 10.1002/aqc.3796

Harden-Davies H., Vierros M., Gobin J., Jaspars M., der Porten v., Pouponneau A., et al. (2020). “Science in Small Island Developing States: Capacity Challenges and Options Relating to Marine Genetic Resources of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction,” in Report for the Alliance of Small Island States (Wollongong, Australia: University of Wollongong).

Hassanali K. (2020). CARICOM and the Blue Economy–Multiple Understandings and Their Implications for Global Engagement. Mar. Policy 120, 104137. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104137

Hassanali K. (2021). Internationalization of EIA in a New Marine Biodiversity Agreement Under the Law of the Sea Convention: A Proposal for a Tiered Approach to Review and Decision-Making. Environ. Impact Assess. Rev. 87, 106554. doi: 10.1016/j.eiar.2021.106554

Ingebritsen C., Neumann I., and Gsthl S. (Eds.) (2012). Small States in International Relations (Seattle, USA: University of Washington Press).

International Institute for Sustainable Development (2019)Summary of the Third Session of the Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) on Marine Biodiversity Beyond Areas of National Jurisdiction: 19-30 August 2019. In: Earth Negotiations Bulletin. Available at: https://enb.iisd.org/download/pdf/enb25218e.pdf (Accessed 16th June, 2021).

Joseph C. (2013). Reflections From the Arms Trade Treaty Negotiations: CARICOM Punching and Succeeding Above Their Weight. Caribbean J. Int. Relations Diplomacy 1 (1), 93–109.

Lewis P. (2005). Unequal Negotiations: Small States in the New Global Economy. J. Eastern Caribbean Stud. 30 (1), 54–108.

Long R., Brincat J. (2019). “Negotiating a New Marine Biodiversity Instrument: Reflections on the Preparatory Phase From the Perspective of the European Union,” in Cooperation and Engagement in the Asia-Pacific Region (Netherlands: Brill Nijhoff), 443–468.

Long R., Chaves M. R. (2015). Anatomy of a New International Instrument for Marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction. Environ. Liability Law Policy Pract. 6, 213–229.

Mahon R., Fanning L. (2021). Scoping Science-Policy Arenas for Regional Ocean Governance in the Wider Caribbean Region. Front. Mar. Sci. 8, 753. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.685122

Mendenhall E., De Santo E., Nyman E., Tiller R. (2019). A Soft Treaty, Hard to Reach: The Second Inter-Governmental Conference for Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction. Mar. Policy 108, 103664. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103664

Mulalap C. Y., Frere T., Huffer E., Hviding E., Paul K., Smith A., et al. (2020). Traditional Knowledge and the BBNJ Instrument. Mar. Policy 122, 104103. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2020.104103

Nordquist M., Rosenne S., Yankov A. (1985). United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea 1982: A Commentary, Vol. IV, Art. 192 to 278, Final Act, Annex Vi. Eds. Nordquist M., Rosenne S., Yankov A. (Leiden, Netherlands: Center for Oceans Law and Policy. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers).

O'Brien D. (2011). CARICOM: Regional Integration in a Post-Colonial World. Eur. Law J. 17 (5), 630–648. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0386.2011.00570.x

OECS (2020). “We Are Large Ocean States”: Blue Economy and Ocean Governance in the Eastern Caribbean (Castries, St. Lucia: OECS Commission).

Ó Súilleabháin A. (2014). Small States at the United Nations: Diverse Perspectives, Shared Opportunities (New York, USA: International Peace Institute).

Panke D. (2012a). Small States in Multilateral Negotiations. What Have We Learned? Cambridge Rev. Int. Affairs 25 (3), 387–398. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2012.710589

Panke D. (2012b). Dwarfs in International Negotiations: How Small States Make Their Voices Heard. Cambridge Rev. Int. Affairs 25 (3), 313–328. doi: 10.1080/09557571.2012.710590

Panke D., Lang S., Wiedemann A. (2017). State and Regional Actors in Complex Governance Systems: Exploring Dynamics of International Negotiations. Br. J. Politics Int. Relations 19 (1), 91–112. doi: 10.1177/1369148116669904

Patil P. G., Diez S. M. (2016) Grenada - Blue Growth Coastal Master Plan (English) (Washington DC, USA: World Bank Group). Available at: http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/358651480931239134/Grenada-Blue-growth-coastal-master-plan (Accessed June 8th 2021).

Payne A. (2004). Small States in the Global Politics of Development. Round Table 93 (376), 623–635. doi: 10.1080/0035853042000289209

Pedrosa A. L., Bitencourt L., Fróes A. C. F., Cazumbá M. L. B., Campos R. G. B., de Brito S. B. C. S., et al. (2020). Emotional, Behavioral, and Psychological Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Front. Psychol. 11, 56621. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.566212

Raymond C. M., Fazey I., Reed M. S., Stringer L. C., Robinson G. M., Evely A. C. (2010). Integrating Local and Scientific Knowledge for Environmental Management. J. Environ. Manage. 91 (8), 1766–1777. doi: 10.1016/j.jenvman.2010.03.023

Ricard P. (2020). “The European Union and the Future International Legally Binding Instrument on Marine Biodiversity Beyond National Jurisdiction,” in Global Challenges and the Law of the Sea (Cham, Switzerland: Springer), 379–399.

Roach J. A. (2014). Today's Customary International Law of the Sea. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 45 (3), 239–259. doi: 10.1080/00908320.2014.929460

Roberts J. (2019). Blue Economy Scoping Study for Dominica (Bridgetown, Barbados: United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Available at: https://www.bb.undp.org/content/barbados/en/home/library/undp_publications/dominca-blue-economy-scoping-study.html (Accessed June 8th 2021).

Roberts J., Downes A., Simpson N. (2020). Barbados Blue Economy Scoping Study – Stocktake and Diagnostic Analysis (Bridgetown, Barbados: United Nations Development Program (UNDP). Available at: https://www.bb.undp.org/content/barbados/en/home/library/undp_publications/barbados-blue-economy-scoping-study.html (Accessed June 8th 2021).

Schulz T., Hufty M., Tschopp M. (2017). Small and Smart: The Role of Switzerland in the Cartagena and Nagoya Protocols Negotiations. Int. Environ. agreements: politics Law economics 17 (4), 553–571. doi: 10.1007/s10784-016-9334-9

Silver J. J., Gray N. J., Campbell L. M., Fairbanks L. W., Gruby R. L. (2015). Blue Economy and Competing Discourses in International Oceans Governance. J. Environ. Dev. 24 (2), 135–160. doi: 10.1177/1070496515580797

Tessnow-von Wysocki I., Vadrot A. (2020). The Voice of Science on Marine Biodiversity Negotiations: A Systematic Literature Review. Front. Mar. Sci. 7, 1044. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2020.614282

Thorhallsson B., Steinsson S. (2017). “Small State Foreign Policy,” in Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics. Ed. Thies C. G. (USA: Oxford University Press).

Tiller R., De Santo E., Mendenhall E., Nyman E. (2019). The Once and Future Treaty: Towards a New Regime for Biodiversity in Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction. Mar. Policy 99, 239–242. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2018.10.046

Tsioumanis A. (2020). UN Marine Negotiations: The Third Intergovernmental Conference and Future Prospects for the Ocean Negotiations. Environ. Policy Law 50 (3), 201–206. doi: 10.3233/EPL-200216

Keywords: BBNJ, UNCLOS, CARICOM, small States in negotiations, ocean governance

Citation: Hassanali K (2022) Participating in Negotiation of a New Ocean Treaty Under the Law of the Sea Convention – Experiences of and Lessons From a Group of Small-Island Developing States. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:902747. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.902747

Received: 23 March 2022; Accepted: 09 May 2022;

Published: 02 June 2022.

Edited by:

Elizabeth Mendenhall, University of Rhode Island, United StatesReviewed by:

Elisa Morgera, University of Strathclyde, United KingdomEthan Beringen, Macquarie University, Australia

Cymie Payne, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey, United States

Copyright © 2022 Hassanali. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Kahlil Hassanali, dzE5MDM2MjBAd211LnNl, a2FobGlsX2hhc3NhbmFsaUBob3RtYWlsLmNvbQ==

Kahlil Hassanali

Kahlil Hassanali