- Marine Zoology Unit, Cavanilles Institute of Biodiversity and Evolutionary Biology, University of Valencia, Valencia, Spain

Each individual cetacean is an ecosystem itself, potentially harboring a great variety of animals that travel with it. Despite being often despised or overlooked, many of these epizoites have been proven to be suitable bio-indicators of their cetacean hosts, informing on health status, social interactions, migration patterns, population structure or phylogeography. Moreover, epizoites are advantageous over internal parasites in that many of them can be detected by direct observation (e.g., boat surveys), thus no capture or dissection of cetaceans are necessary. Previous reviews of epizoites of cetaceans have focused on specific geographical areas, cetacean species or epibiotic taxa, but fall short to include the increasing number of records and scientific findings about these animals. Here we present an updated review of all records of associations between cetaceans and their epibiotic fauna (i.e., commensals, ecto- or mesoparasites, and mutualists). We gathered nearly 500 publications and found a total of 58 facultative or obligate epibiotic taxa from 11 orders of arthropods, vertebrates, cnidarians, and a nematode that are associated to the external surface of 66 cetacean species around the globe. We also provide information on the use as an indicator species in the literature, if any, and about other relevant traits, such as geographic range, host specificity, genetic data, and life-cycle. We encourage researchers, not only to provide quantitative data (i.e., prevalence, abundance) on the epizoites they find on cetaceans, but also to inform on their absence. The inferences drawn from epizoites can greatly benefit conservation plans of both cetaceans and their epizoites.

Introduction

General Features of Epibiosis in Cetaceans

Cetaceans have developed a number of symbiotic associations (sensu Leung and Poulin, 2008) with other organisms, including endo-, meso- and ectoparasitism, commensalism, and mutualism (e.g., Arvy, 1982; Raga, 1994). Some of these organisms, the epibionts (also known as episymbionts or ectosymbionts), are associated to the external surface of cetaceans and can be classified into two basic types. On the one hand, ectoparasites live in/on the skin and cause a variable degree of harm by feeding on hosts’ integument (e.g., Smyth, 1962; Geraci and St. Aubin, 1987; Hopla et al., 1994). On the other hand, commensals or phoronts do not trophically depend on the tissues of cetaceans (also named basibionts in this case), thus they are generally harmless but benefit from epibiosis in multiple ways, e.g., via an improved feeding performance, reduction of predation, favored intraspecific contacts for reproduction, or offspring dispersion (Anderson, 1994; Seilacher, 2005; Carrillo et al., 2015). Not surprisingly, though, the limits of each type of interaction are not always clear-cut. For instance, whale-lice (fam. Cyamidae) are considered ectoparasites that primarily feed on hosts’ skin, but it has been speculated that they may opportunistically feed on plankton, even helping whales to detect plankton blooms, leading to a potentially mutualistic relationship (Rowntree, 1996). Or, high loads of commensal epibionts could increase the swimming drag or damage the skin on the site of settlement, thus producing indirect harm to cetaceans (Tomilin, 1957).

Given the high variety of life cycles of the epibionts of cetaceans, it is perhaps not surprising that their specific interactions are similarly diverse. Some epibionts depend strictly on cetaceans during their whole life (e.g., whale lice; Leung, 1976), whereas others use them only at some stages (e.g., barnacles; Nogata and Matsumura, 2006). Among commensals, many species are obligate epibionts, settling exclusively on cetaceans (e.g., coronulid barnacles; Hayashi et al., 2013), but others can colonize also inanimate substrata such as vessels or floating debris (e.g., Conchoderma spp. and Lepas spp.; Frick and Pfaller, 2013). The degree of host/basibiont specificity is also variable. For instance, many whale lice are known only from single, or a few, host species (Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018), but other epibionts have a very broad host spectrum (e.g., Xenobalanus globicitipitis Steenstrup, 1852 or Pennella balaenoptera Koren & Danielssen, 1877; Kane et al., 2008; Fraija-Fernández et al., 2018). Finally, there are examples of hyperepibiosis in which some epibionts, e.g., barnacles, can act as basibionts for other epibionts, e.g., Conchoderma spp. or cyamids (Cornwall, 1927; Matthews, 1937; Leung, 1970a).

Susceptibility and Health Impact of Cetacean Epibiosis

As many other symbionts, epibionts must succeed twice to live their associative life. This two-step process is mediated by the so-called encounter and compatibility filters (Combes, 2001). First, spatial and temporal overlap must take place for initial settlement. Second, whether the host is a suitable substratum will determine survival and/or reproduction on it. Epidermis renewal and hydrolytic substances of cetacean skin may prevent fouling, at least to some extent (Hicks 1985; Baum et al., 2000; Baum et al., 2001), but skin regeneration and immune functions are seemingly lower in debilitated dolphins (J. R. Geraci and S. H. Ridgway pers comm. in Aznar et al., 1994). Poor health can also result in slower swimming (Aznar et al., 1994; Lehnert et al., 2021), fostering better conditions for epibiotic settlement (e.g., providing more time for contact with blooms of free-living infective stages, or mild water flow over the host’s body, thus reducing drag and facilitating initial colonization). For instance, striped dolphins, Stenella coeruleoalba (Meyen, 1833), infected by morbillivirus and in poor nutritional condition harbored high loads of parasitic and commensal epizoites (Aguilar and Raga, 1993; Aznar et al., 1994; Aznar et al., 2005). Also, higher prevalence of cyamids in porpoises could hint a higher incidence of disease-related skin injuries, where they attach (Lehnert et al., 2021). Another example is the massive infestation of cyamids on a stranded humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae (Borowski, 1781), that suffered from severe discospondylitis and, as a result, reduced mobility (Groch et al., 2018).

Once settled, the impact of epibionts on cetacean health varies among taxa (especially between ectoparasites and commensals; see above). For instance, the mesoparasite Pennella balaenoptera penetrates the skin and blubber of its hosts; this process has been related to both macro- and microscopic lesions such as abscesses, inflammation, and dermatitis (Cornaglia et al., 2000; Gomerčić et al., 2006; IJsseldijk et al., 2018). In contrast, no direct damage has been related to whale lice infections (e.g., Migaki, 1987; Lehnert et al., 2021), although it has been speculated that their occurrence may hinder skin healing processes (Lehnert et al., 2021). On the other hand, the possibility that some cetacean epibionts can act as viral or bacterial vectors is an open question, as it has been observed for ectoparasitic crustaceans parasitizing fish (Smit et al., 2019) or lice infecting seals (La Linn et al., 2001). Climate changes have shifted the geographical distribution of arthropod-borne viruses (Gould and Higgs, 2008) and whether these may emerge in cetaceans and even be transmitted by their epibonts (e.g., ectoparasitic lice, see Van Bressem et al., 2009) remains unknown.

Epibionts as Cetacean Indicators

Due to temporal or permanent association with their hosts/basibionts, both endoparasites and epibionts represent a cost-effective tool to study multiple facets of cetacean biology (e.g., Dailey and Vogelbein, 1991; Balbuena et al., 1995; Gomes et al., 2021). However, epibionts are advantageous over endoparasites in that many of them are detectable in the field (e.g., using boat-based photography; see Hermosilla et al., 2015; Siciliano et al., 2020; Flach et al., 2021), and can often be easily found and counted on stranded hosts, be alive or dead, with minimum dissection, if at all (Balbuena et al., 1995). Most studies using epibionts as markers only require basic data to be gathered, i.e. genus- or, preferably, species-level identification, and quantification of population size at host individual or population scales. More elaborated research may require additional information on (1) degree of host specificity, (2) size measurements as an estimate of time since attachment, (3) distribution patterns on hosts’ body, (4) geographic range, and/or (5) selected molecular markers (e.g., Bushuev, 1990; Kaliszewska et al., 2005; Ten et al., 2019; Moreno-Colom et al., 2020; Lehnert et al., 2021).

At present, cetacean epibionts have been used, inter alia, as ‘tags’ to trace past (e.g., Collareta et al., 2018a; Taylor et al., 2019) or present-day (e.g., Pearson et al., 2020; Visser et al., 2020) migratory routes and habitat use; shed light on phylogeography, population structure, and ecological stock delimitation (e.g., Bushuev, 1990; Kaliszewska et al., 2005; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2018); give insight into hydrodynamics (e.g., Kasuya and Rice, 1970; Briggs and Morejohn, 1972; Fish and Battle, 1995; Carrillo et al., 2015; Moreno-Colom et al., 2020), assist in individual recognition (e.g., Visser et al., 2020); and act as sentinels of health status (Mackintosh and Wheeler, 1929; Van Waerebeek et al., 1993; Aznar et al., 1994; Aznar et al., 2005; Lehnert et al., 2007; Vecchione and Aznar, 2014; Lehnert et al., 2021; for more references see Results). Nonetheless, there is plently of further opportunities to exploit the full potential of these organisms as biological indicators.

Aims

Studies including information on cetacean epibionts have usually focused on particular geographical areas (e.g., Kane et al., 2008; Lehnert et al., 2019), host species (e.g., Rice, 1978; Stimmelmayr and Gulland, 2020) or epibiotic taxa (e.g., Kane et al., 2008; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018). Furthermore, in the last decades a number of nomenclatural changes, new associations, and geographical records have been accumulating, thus we think that the available comprehensive reviews and checklists on this subject (Beneden, 1870; Dailey and Brownell, 1972; Arvy, 1977; Arvy, 1982; Raga, 1994) should be updated. On the other hand, few articles have reviewed the use of marine mammal parasites as biological tags (Balbuena et al., 1995; Mackenzie, 2002), and none gathered information about the whole epibiotic fauna of cetaceans.

The present systematic review aims to compile and update all records of cetacean epibiotic fauna (= epizoites) to date as a thorough, handy catalogue for researchers. Other organisms, i.e. diatoms and cookie-cutter shark, Isistius brasiliensis (Quoy & Gaimard, 1824) are also included in a specific section of this review to provide a complete picture of other externally-associated organisms that have been proven to be valuable biological indicators for cetaceans. Finally, we identify information gaps and future research directions and highlight the value of cetacean epibionts as indicator tools, encouraging their application in cetacean research.

Methods

Literature Search

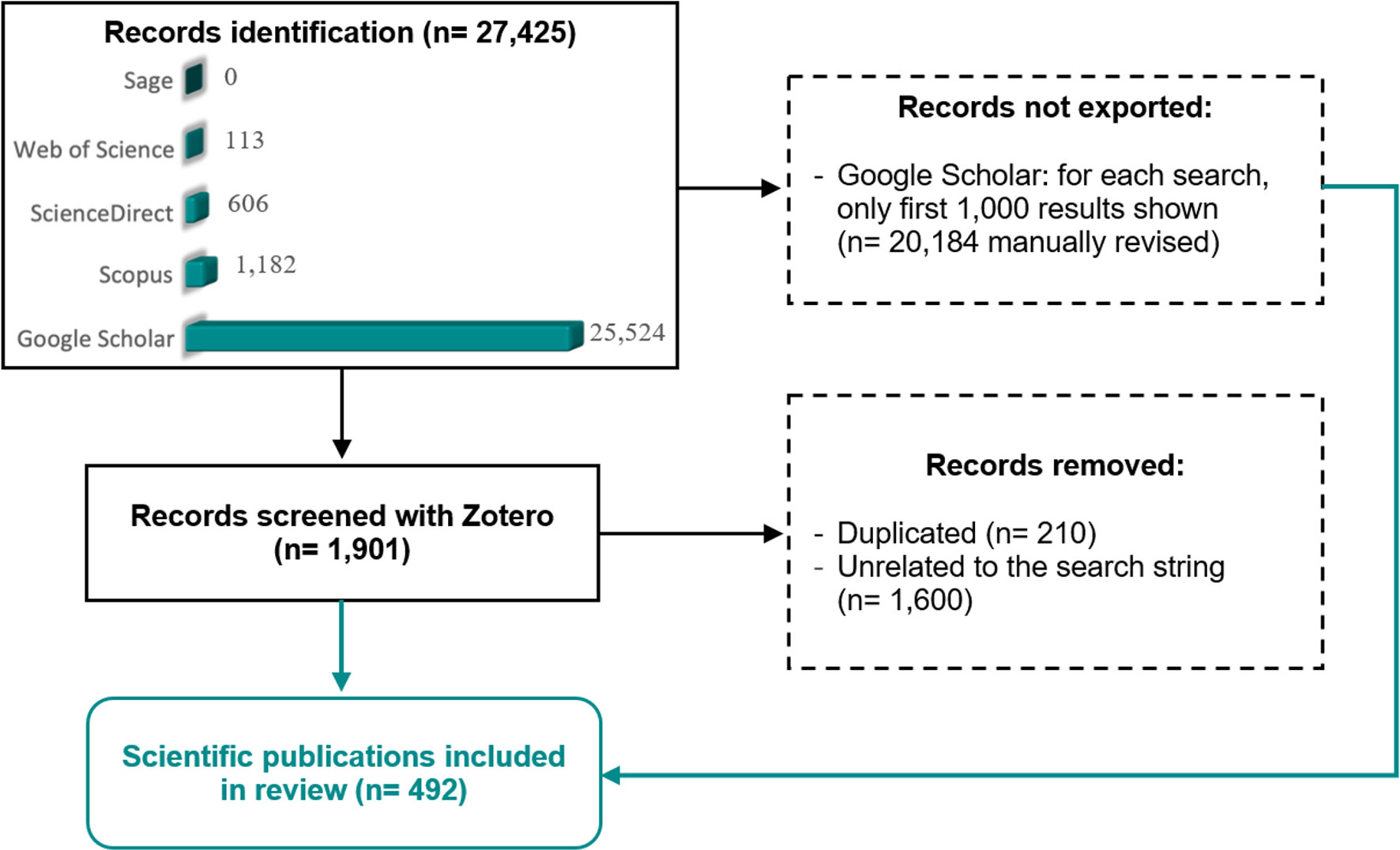

A systematic literature review was performed following PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) guidelines (Moher et al., 2015; Figure 1). We conducted a thorough bibliographic search in the following databases: Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.com), Scopus (https://www.scopus.com), ScienceDirect (https://www.sciencedirect.com), Web of Science (https://www.webofscience.com), and Sage (https://journals.sagepub.com). The following search string was used for Scopus, ScienceDirect, Web of Science, and Sage: (epibiont OR epibiotic OR epibiosis OR epizoite OR epizoic OR barnacle OR ectoparasite OR mesoparasite) AND (balaena OR eubalaena OR balaenoptera OR megaptera OR eschrichtius OR caperea OR cephalorhynchus OR delphinus OR feresa OR globicephala OR grampus OR lagenodelphis OR lagenorhynchus OR lissodelphis OR orcaella OR orcinus OR peponocephala OR pseudorca OR sotalia OR “Sousa chinensis” OR “Sousa plumbea” OR “Sousa sahulensis” OR “Sousa teuszii” OR stenella OR “Steno bredanensis” OR tursiops OR “Inia geoffrensis” OR kogia OR delphinapterus OR “Monodon monoceros” OR neophocaena OR phocoena OR phocoenoides OR physeter OR platanista OR pontoporia OR berardius OR hyperoodon OR mesoplodon OR tasmacetus OR ziphius OR indopacetus)

Figure 1 Flow diagram of the methodology used in the literature search performed in this systematic review. Adaptation from PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews) template (Page et al., 2021).

Note that the use of genus name in some cetacean genera, i.e., Monodon Linnaeus, 1758, Sousa Gray, 1866, and Steno Gray, 1846 yielded many records of unrelated taxa, thus full species name was included in these cases. The output was exported and checked for duplicates and non-relevant papers with the open-source reference management software Zotero.

In the case of Google Scholar, only the first 100 result pages are available, thus we used the search strings “(epibiont OR epibiotic OR epibiosis OR epizoite OR epizoic OR barnacle OR ectoparasite OR mesoparasite) AND i”, where i stands for a cetacean genus, to maximize the number of obtainable records. The output of each search was checked manually. In addition, we searched each epibiotic species in GBIF.org and included those associations and geographic locations that had not been reported in scientific publications. For all publications obtained, we looked up their references to search for potential missing records.

The final list includes the literature published until December 2021 that provides information on cetacean-epibiont(s) associations (Figure 1). These results are listed according to the epibiotic (see the Results) and the cetacean taxa (Supplementary Table 1). For each selected record, we extracted the following information, when available: cetacean species, epibiotic species, geographic area(s), prevalence (i.e., percent occurrence of the epibiont in each cetacean species of the sample), location on the cetacean, and any information related to indicator potential. Current species nomenclature and synonyms were checked in WoRMS (https://www.marinespecies.org/) and recent literature. Geographical locations were also classified at the scale of Large Marine Ecosystem (LME) (see e.g., Brotz et al., 2012).

For comparative purposes, we investigated research effort on each cetacean species using the number of results in Google Scholar as a proxy. For each species, we used the scientific name in quotation marks as search string. For the 6 species that previously constituted the Lagenorynchus genus (see Vollmer et al., 2019), we used the former nomenclature for the search to avoid understimation (i.e., "Lagenorynchus" followed by species name).

Results

General Patterns

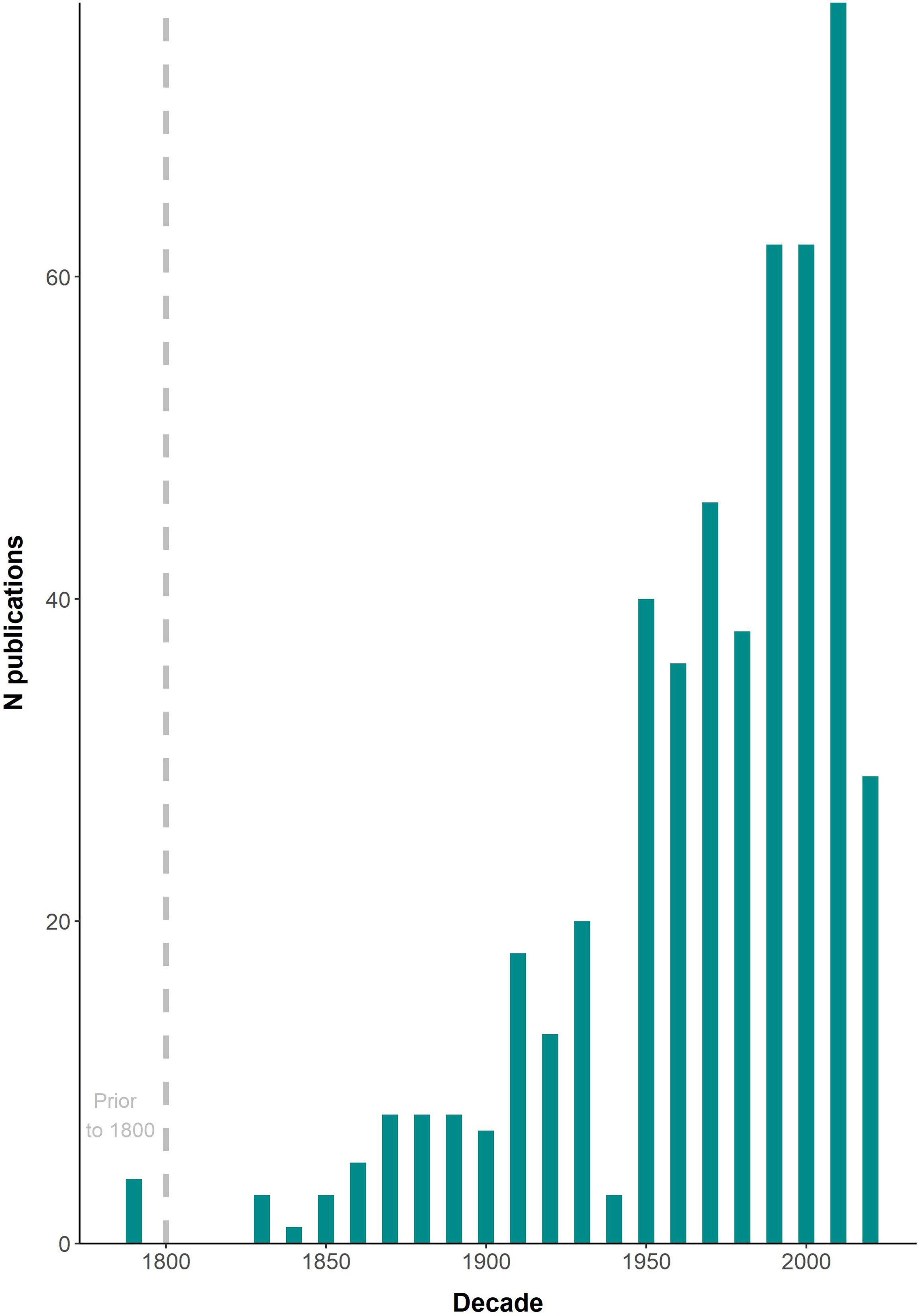

A total of 492 published documents, including 7 unpublished manuscripts, and 9 GBIF records were found. Three additional reliable records were serendipitously found in internet photo-catalogues and were also included in the final list (Supplementary Table 1). A roughly exponential trend in the number of publications was found throughout the period covered (1655-2021), with a peak in the 2010s decade (Figure 2); 2020 was the most productive year with 21 publications.

Figure 2 Number (N) of publications including data on cetacean epibiotic fauna at a decadal scale from 1655 to 2021.

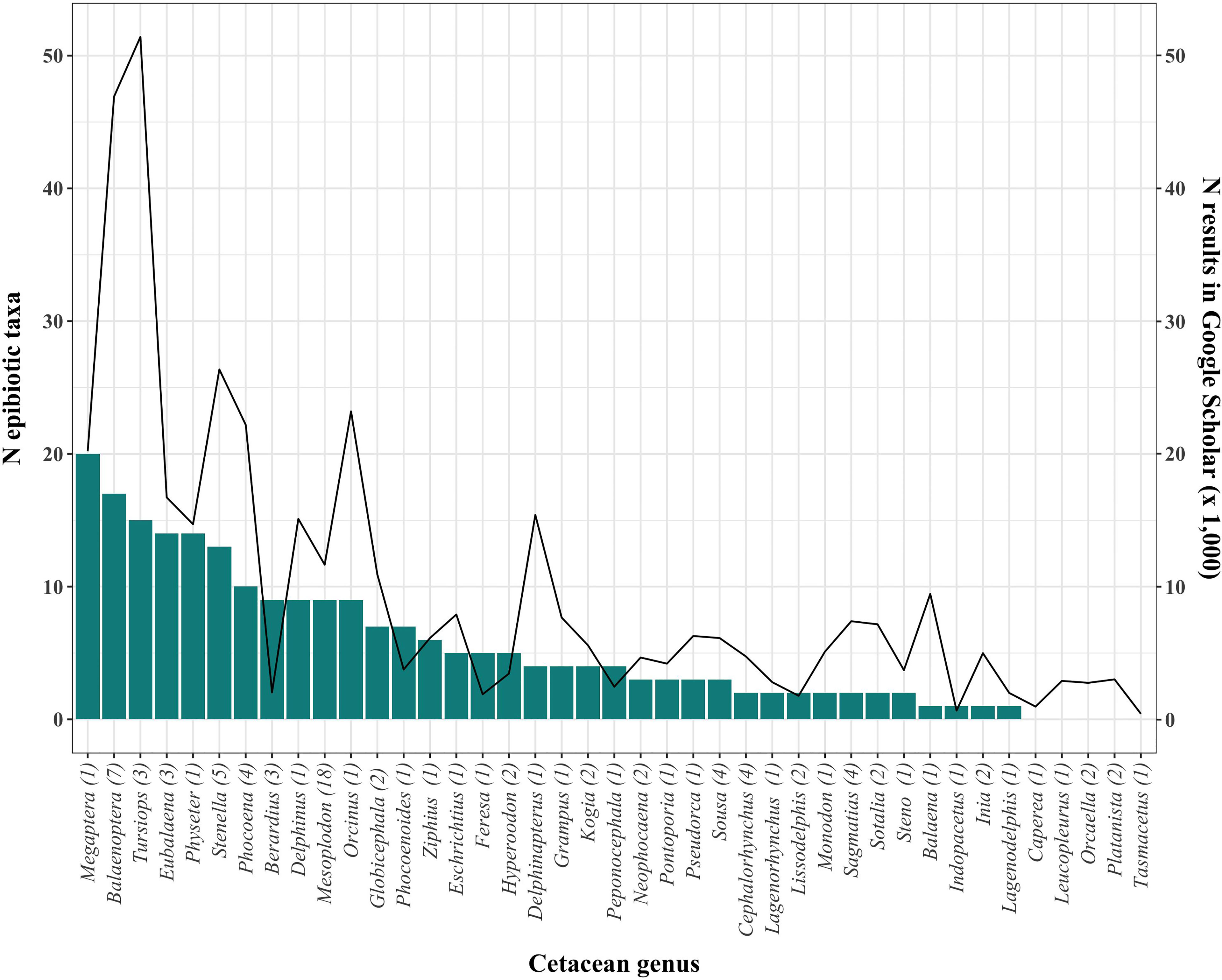

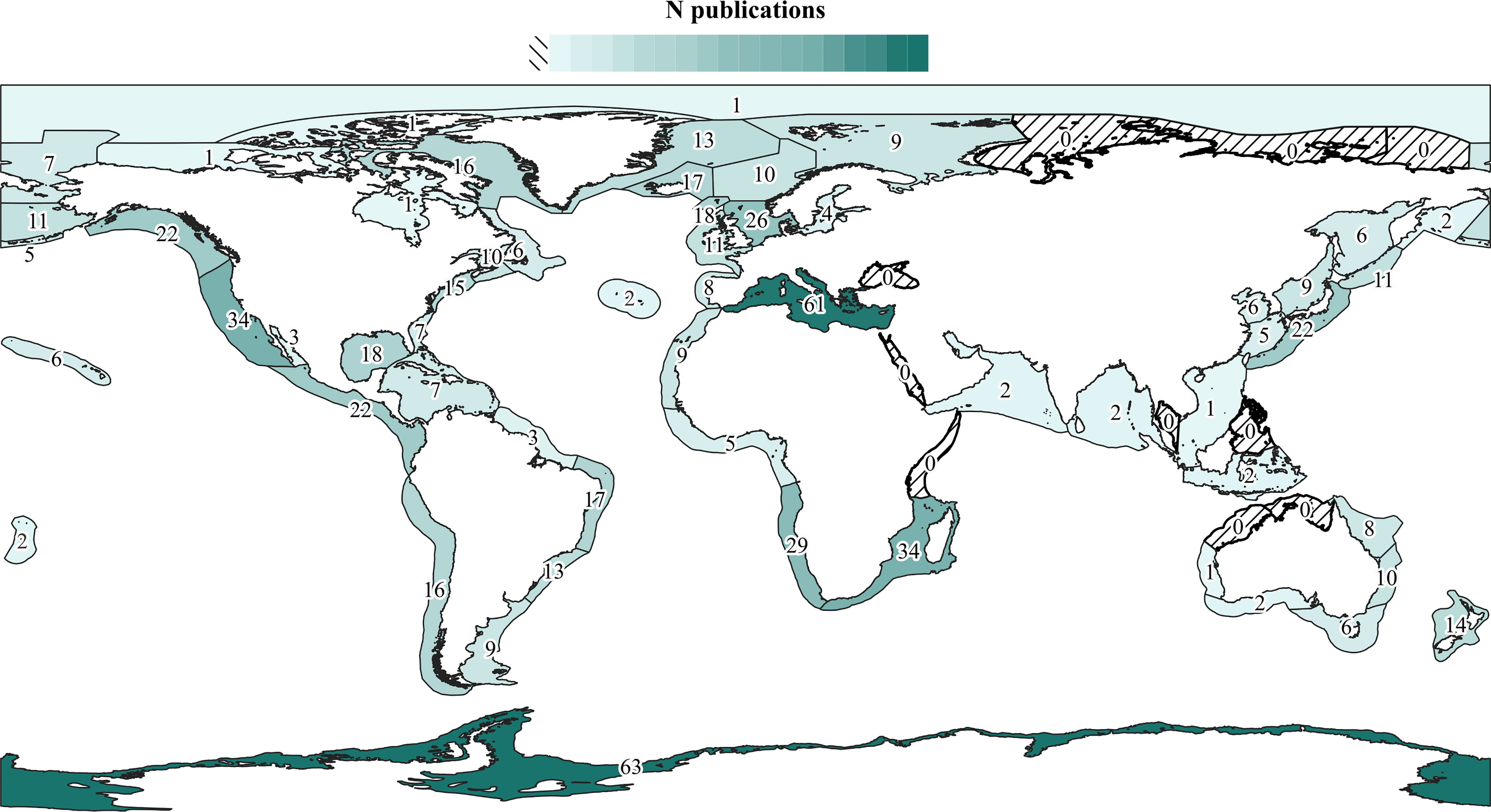

Baleen whales, and particularly Megaptera novaeangliae (Borowski, 1781), show the highest diversity of epibionts, followed by Tursiops spp. (Figure 3). However, it is difficult to ascertain the extent to which this pattern is affected by sampling effort (Figure 3). Likewise, 26 cetacean species from four genera have no published records of epibiotic fauna to date (Supplementary Table 1), but these hosts have also been generally little studied (< 4,000 publications in Google Scholar, Figure 3). Research effort varies also among geographic regions (Figure 4). The Mediterranean Sea and Antarctica are, by far, the geographic areas with the highest number of publications of cetacean epizoites, and some areas still lack such studies.

Figure 3 Number of epibiotic species (bars, left y-axis) and total number of general results in Google Scholar (line, right y-axis) of each cetacean genus. The number of cetacean species in each genus is shown in parentheses.

Figure 4 Number of publications (indicated by numbers and color gradient) on cetaceans that contain data on their epibiotic fauna at least to genus level grouped by Large Marine Ecosystems (LME). When the same publication includes data for several LMEs, it is counted separately for each one. Azores (NE Atlantic) and Tonga (SW Pacific) are not in the LME system but were included as additional areas.

Systematic List

A systematic list of the 58 epizoic taxa (53 at species level) found to date on cetaceans follows. For each one, we provide information on (i) taxonomic synonyms; (ii) a subset of selected references that provide a complete overview of the species morphology; (iii) molecular sequences available on GenBank (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/), with references or with Accession Number whenever no published manuscript was available; (iv) primary type of association, including parasitic (34 spp.), obligate commensal (8-9 spp.), facultative commensal (8 spp.), mutualistic (possibly 1 sp.), or unknown (2 spp.); (v) a list of cetacean hosts/basibionts; (vi) geographic range; (vii) life-cycle; and (viii) microhabitat, i.e., the location(s) on the cetacean body, with references; and (ix) indicator use or potential, with references. Any other relevant data are reported in the ‘Remarks’ section, and all records of association between epizoites and cetaceans are cited in the ‘References’ section.

Phylum Arthropoda von Siebold, 1848

Class Malacostraca Latreille, 1802

Subclass Eumalacostraca, Grobben, 1892

Order Amphipoda Latreille, 1816

Family Cyamidae Rafinesque, 1815

The Cyamidae (‘whale lice’) comprises a group of amphipods that are found exclusively on marine cetaceans (see, e.g., Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018). These 3-30 mm creatures use their pereopods to cling to areas of reduced water flow (e.g., ventral grooves, blowhole, genital slit), where they spend their whole life feeding primarily on cetacean skin (Rowntree, 1983; Rowntree, 1996; Schell et al., 2000); thus, they are all considered ectoparasites. However, evidence that they cause any harm is rather scarce, so some authors support the use of the term ‘ectocommensals’ for them (Leung, 1976; Kenney, 2009). Rowntree (1996) discussed the possibility that some cyamids from whales may also feed on plankton, having perhaps developed mutualistic associations with their hosts. In particular, the cyamid species covering the sensory hairs of whales could increase their activity during plankton blooms, amplifying the signal for prey detection by whales. In addition, it has also been suggested that cyamids could feed on cetaceans’ dead skin and epibiotic algae, thus cleaning up wounds and speeding up healing (Williams and Bunkley-Williams, 2019). Lehnert et al. (2021), on the contrary, hypothesized that cyamids’ feeding activity could actually hinder the healing of skin injuries, and some authors have suggested that heavy cyamid infections may contribute to the death of their hosts (Mignucci-Giannoni et al., 1998).

Since cyamids lack swimming stages, transmission must occur through bodily contacts (Fransen and Smeenk, 1991; Pfeiffer, 2009). Males are typically larger than females (but see Fraija-Fernández et al., 2017) and, at least in some species, have been observed to perfom pre-copulatory mate guarding (Rowntree, 1996; Oliver and Trilles, 2000). Females mate after molting (Conlan, 1991) and incubate eggs and protect the hatchling in a ventral brood pouch (Leung, 1976; Williams and Bunkley-Williams, 2019).

Balaenocyamus balaenopterae (Barnard K.H. 1931)

Synonyms

Cyamus balaenopterae Barnard K.H. 1931

Morphological Description

Barnard, 1932; Margolis, 1959; Leung, 1967; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

18S rRNA (Ito et al., 2011)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Balaenoptera acutorostrata Lacépède, 1804, B. bonaerensis Burmeister, 1867, B. musculus (Linnaeus, 1758), B. physalus (Linnaeus, 1758)

Geographic Range

Atlantic, Pacific, Mediterranean, Indian Ocean, Antarctica

Life Cycle

In common minke whales, Balaenoptera acutorostrata, captured off Iceland, a one-year long life cycle is assumed; similar to other whale lice, hatching occurs in autumn, juveniles are released from the females’ pouch in mid-winter, and they reach sexual maturity in spring or summer (Ólafsdóttir and Shinn, 2013). This life cycle may be synchronized with whales’ seasonal migration (Raga and Sanpera, 1986).

Microhabitat

Natural orifices, i.e., ventral grooves, eyes, umbilicus, mammary slits, anus, and genital slit (Ohsumi et al., 1970; Ivashin, 1975; Raga and Sanpera, 1986)

Use as Indicator

Used to delineate ecological stocks and detect sex segregation in migrating cetaceans (Kawamura, 1969; Bushuev, 1990; Ólafsdóttir and Shinn, 2013).

Remarks

-

References

Mackintosh and Wheeler, 1929; Barnard, 1931; Barnard, 1932; Margolis, 1959; Leung, 1965; Kawamura, 1969; Ohsumi et al., 1970; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Ivashin, 1975; Rice, 1978; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Best, 1982; Raga and Sanpera, 1986; Avdeev, 1989; Bushuev, 1990; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1990 (unpubl.); Dailey and Vogelbein, 1991; Kuramochi et al., 1996; Araki et al., 1997; Uchida, 1998; Kuramochi et al., 2000; Margolis et al., 2000; Uchida and Araki, 2000; Ólafsdóttir and Shinn, 2013; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018; Ten et al., unpubl.

Cyamus boopis (Lütken, 1870)

Synonyms

Cyamus elongatus Hiro, 1938, C. pacificus Lütken, 1873, C. suffuses Dall, 1872, Paracyamus boopis (Lütken, 1870)

Morphological Description

Sars, 1895; Barnard, 1932; Leung, 1967; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2016

Molecular Sequences

COI (Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017a, Iwasa-Arai et al., 2018; GenBank FJ751158; FJ751159; MT551876; OK562816-OK562832), COII, COIII, ATP6, ATP8, ND3 (Kaliszewska et al., 2005) and the complete mitochondrial genome (GenBank MT458501)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Typically on Megaptera novaeangliae, but once reported on Berardius bairdii Duvernoy, 1851, Eubalaena australis (Desmoulins, 1822), and Tursiops truncatus (Montagu, 1821)

Geographic Range

Arctic, Atlantic, Pacific, Mediterranean, Indian Ocean, Antarctica

Life Cycle

Transmission may regularly occur during contacts between migrating hosts or at the feeding areas (Iwasa-Arai et al., 2018).

Microhabitat

Ubiquitous, i.e., head tubercles, eye, jaw, ventral grooves, genital slit, fins (Matthews, 1937; Cockrill, 1960; Ivashin, 1965; Rowntree, 1996). Sometimes attached to the epibiotic cirripedes Coronula diadema (Linnaeus, 1767) and Conchoderma spp. (Dall, 1872; Matthews, 1937; Stephensen, 1942; Angot, 1951; Cockrill, 1960).

Use as Indicator

Haplotype and nucleotide diversities have been used to assess inter-mixing between different breeding populations of humpback whales (Iwasa-Arai et al., 2018). Also, its presence on a southern right whale suggests an interspecific interaction with humpback whales in Brazilian waters (Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017a). The presence of an alive unidentified cyamid (likely C. boopis) on a humpback whale was used to infer that the stranding occurred less than three days before (Bortolotto et al., 2016).

Remarks

Some records of C. boopis on sperm whales (e.g., Barnard, 1932) were re-classified as C. catodontis by Margolis (1955) and later authors (e.g., Stock, 1973a; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018).

References

Lütken, 1870; Dall, 1872; Scammon, 1874; Pouchet, 1888; Pouchet, 1892; Sars, 1895; Collet, 1912; Chevreux, 1913a; Liouville, 1913; Ishi, 1915; Cornwall, 1928; Barnard, 1932; Matthews, 1937; Hiro, 1938; Scheffer, 1939; Angot, 1951; Hurley, 1952; Rees, 1953; Margolis, 1954a; Cockrill, 1960; Rice, 1963; Ivashin, 1965; Leung, 1965; Leung, 1970b; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1991; Rowntree, 1996; Abollo et al., 1998; Osmond and Kaufman, 1998; Margolis et al., 2000; Alonso de Pina and Giuffra, 2003; Carvalho et al., 2010; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2016; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017b; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2018; Groch et al., 2018; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2021; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2018; Qiao et al., 2020

Cyamus catodontis (Margolis, 1954)

Synonyms

Cyamus bahamondei Buzeta, 1963

Morphological Description

Margolis, 1954a; Margolis, 1955; Buzeta, 1963; Leung, 1967; Stock, 1973a; Margolis et al., 2000

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Typically on Physeter macrocephalus Linnaeus, 1758, but once reported on Balaenoptera acutorostrata, B. bonaerensis, B. musculus, B. physalus, and Berardius bairdii

Geographic Range

Eastern Atlantic, Pacific, Indian Ocean, Antarctica

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

One record on a sperm whale’s deformed jaw (Buzeta, 1963)

Use as Indicator

Used to detect social segregation in sperm whales; large males, but not females nor male bachelors, were infected with C. catodontis, suggesting that the former leave their natal pods at puberty (Best, 1969a; Best, 1979).

Remarks

-

References

Barnard, 1932; Margolis, 1954a; Clarke, 1956; Buzeta, 1963; Rice, 1963; Leung, 1965; Best, 1969a; Best, 1969b; Best, 1979; Stock, 1973b; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Fransen and Smeenk, 1991; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Cyamus ceti (Linnaeus, 1758)

Synonyms

Oniscus ceti Linnaeus, 1758

Morphological Description

Krøyer, 1843; Leung, 1967; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

COI (GenBank FJ751160-FJ751180)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Typically on Balaena mysticetus Linnaeus, 1758, but once reported on Eschrichtius robustus (Lilljeborg, 1861) and Eubalaena japonica (Lacépède, 1818)

Geographic Range

Artic, North Pacific

Life Cycle

Similar to C. scammoni (see below), but juveniles reach maturity before whales’ northern migration to summer grounds (Leung, 1976). Females carry 150-240 eggs in the brood pouch, of which about 75% are fertilized (Leung, 1976).

Microhabitat

Creases of the lips, flippers, flukes, and thin areas, e.g., armpit and genital slit (Stephensen, 1942; Leung, 1976)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Linnaeus, 1758; Lütken, 1870; Dall, 1872; Scammon, 1874; Margolis, 1955; Omura, 1958; Rice, 1963; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Leung, 1976; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Heckmann et al., 1987; Margolis et al., 2000; Kaliszewska et al., 2005; Von Duyke et al., 2016; Chernova et al., 2017; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Cyamus erraticus (Roussel de Vauzème, 1834)

Synonyms

Paracyamus erraticus Roussel de Vauzème, 1834

Morphological Description

Barnard, 1932; Iwasa, 1934; Margolis, 1955; Leung, 1967

Molecular Sequences

COI, COII, COIII, ATP6, ATP8, ND3 (Kaliszewska et al., 2005), EF1a (Seger et al., 2010)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Typically on Eubalaena australis, E. glacialis (Müller, 1776), and E. japonica; also found on Megaptera novaeangliae

Geographic Range

Atlantic, Pacific, Indian Ocean, Antarctica

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Genital, mammary, and anal slits, armpits, and opportunistically on wounds (Stephensen, 1942; Rowntree, 1996; see Remarks)

Use as Indicator

Sequence variation in mitochondrial DNA was used to investigate associations among right whale individuals and subpopulations, to estimate the time of past divergence of right whale populations, and to infer possible changes in their population sizes (Kaliszewska et al., 2005).

Remarks

Transmission probably occurs from mothers’s genital slit to calves’ head at birth. As callosity tissue develops, calves are colonized by the putative competitor Cyamus ovalis Roussel de Vauzème, 1834, likely by head-to-head contact with the mother; the distribution of C. erraticus is then restricted to skin folds and wounds (Rowntree, 1996).

References

Rossel de Vauzème, 1834; Lütken, 1873; Collet, 1912; Chevreux, 1913a; Liouville, 1913; Barnard, 1932; Iwasa, 1934; Margolis, 1955; Lincoln and Hurle7y, 1974a; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Rowntree, 1996; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Cyamus eschrichtii (Margolis, McDonald & Bousfield, 2000)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Eschrichtius robustus

Geographic Range

California (eastern North Pacific)

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

-

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Cyamus gracilis (Roussel de Vauzème, 1834)

Synonyms

Paracyamus gracilis (Roussel de Vauzème, 1834)

Morphological Description

Barnard, 1932; Leung, 1967; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

COI, COII, COIII, ATP6, ATP8, ND3 (Kaliszewska et al., 2005), EF1a (Seger et al., 2010)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Eubalaena australis, E. glacialis, E. japonica

Geographic Range

Atlantic, Pacific, Antarctica

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Head callosities (Barnard, 1932; Rowntree, 1996)

Use as Indicator

See C. erraticus.

Remarks

In a South African sample, C. gracilis co-occurred with C. ovalis Roussel de Vauzème, 1834 (Barnard, 1932).

References

Rossel de Vauzème, 1834; Lütken, 1873; Barnard, 1932; Margolis, 1955; Leung, 1965, Leung 1967; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Rowntree, 1996; Alonso de Pina and Giuffra, 2003; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Cyamus kessleri (A. Brandt, 1873)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Brandt, 1872; Leung, 1967; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

COI (GenBank FJ751215-FJ751224)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Eschrichtius robustus

Geographic Range

From Chukchi Sea to California (eastern North Pacific)

Life Cycle

Similar to C. scammoni (see below), but juveniles reach maturity before whales’ northern migration to summer grounds (Leung, 1976). Females carry up to 300 eggs in the brood pouch, of which 75-80% are fertilized (Leung, 1976).

Microhabitat

Umbilicus, genital slit, and anal aperture (Leung, 1976)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Hurley and Mohr, 1957; Leung, 1976; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Margolis et al., 2000; Kaliszewska et al., 2005; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Cyamus mesorubraedon (Margolis, McDonald & Bousfield, 2000)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Physeter macrocephalus

Geographic Range

Vancouver Island (eastern North Pacific)

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

-

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Cyamus monodontis (Lütken, 1870)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Leung, 1967; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017b; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Delphinapterus leucas (Pallas, 1776), Monodon monoceros Linnaeus, 1758, Ziphius cavirostris Cuvier, 1823

Geographic Range

Arctic, western North Atlantic, eastern North Pacific

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Tusk base, caudal fin along with C. nodosus, skin injuries (Porsild, 1922; Stephensen, 1942)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Lütken, 1870; Porsild, 1922; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Heyning and Dahlheim, 1988; Mignucci-Giannoni et al., 1998; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017a

Cyamus nodosus (Lütken, 1861)

Synonyms

Paracyamus nodosus (Lütken, 1861)

Morphological Description

Leung, 1967; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017b; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Delphinapterus leucas, Monodon monoceros

Geographic Range

Greenland (Arctic, western North Atlantic)

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Tusk base, caudal fin along with C. monodontis, skin injuries (Porsild, 1922; Stephensen, 1942)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Lütken, 1870; Porsild, 1922; Margolis, 1954b; Margolis, 1955; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017a

Cyamus orubraedon (Waller, 1989)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Berardius bairdii

Geographic Range

North Pacific

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Lower jaw (Waller, 1989)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Waller, 1989; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Cyamus ovalis (Roussel de Vauzème, 1834)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Roussel de Vauzème, 1834; Iwasa, 1934; Leung, 1967; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

COI (Kaliszewska et al., 2005; Seger et al., 2010), COII, COIII, ATP6, ATP8, ND3 (Kaliszewska et al., 2005), EF1a (Seger et al., 2010)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Eubalaena australis, E. glacialis, E. japonica, Physeter macrocephalus; once reported on Megaptera novaeangliae

Geographic Range

Atlantic, Pacific, Antarctica

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Head callosities, sometimes with C. erraticus (Stephensen, 1942; Rowntree, 1996; see C. erraticus, above)

Use as Indicator

See C. erraticus.

Remarks

Once misidentified as Cyamus rhytinae (J. F. Brandt, 1846), ectoparasitic on the extinct Steller’s sea cow, Hydrodamalis gigas (Zimmermann, 1780) Palmer, 1895 (see Leung, 1967; O'Clair and O'Clair, 1998).

References

Roussel de Vauzème 1834; Lütken, 1873; Collet, 1912; Liouville, 1913; Barnard, 1932; Iwasa, 1934; Margolis, 1955; Leung, 1967; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Rowntree, 1996; Margolis et al., 2000; Pettis et al., 2004; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Cyamus scammoni (Dall, 1872)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Lütken, 1887; Leung, 1967; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

COI (GenBank FJ751214), hemocyanin mRNA (Terwilliger and Ryan, 2006)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Eschrichtius robustus

Geographic Range

North Pacific

Life Cycle

Females can carry about 1,000 eggs in the brood pouch, although only about a 60% are fertilized (Leung, 1976). Eggs hatch in autumn, when gray whales arrive in California, and the young remain in the female’s pouch for 2-3 months and then find shelter in host’s crevices (Leung, 1976). Juveniles reach maturity during the winter northward migration of whales, and have full-grown brood upon arrival to summer grounds. The whole cycle takes 8-9 months to complete and there is probably some overlap in the life cycle of different individuals, given that juveniles are present throughout the year (Leung, 1976). The number of instars is presumed to be at least 7 or 8, but the number of ecdysis was untraceable (Leung, 1976).

Microhabitat

Ventral grooves, i.e., jaw and belly; flukes; on the cirriped Cryptolepas rachianecti Dall, 1872 (Leung, 1976; Dailey et al., 2000)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

Chonotrichous ciliates can infest its ventral surface (Leung, 1976).

References

Dall, 1872; Scammon, 1874; Lütken, 1887; Margolis, 1954a; Rice, 1963; Leung, 1965; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Leung, 1976; Sullivan and Houck, 1979; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Dailey et al., 2000; Margolis et al., 2000; Kaliszewska et al., 2005; Takeda and Ogino, 2005; Murase et al., 2014; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Isocyamus antarcticensis (Vlasova in Berzin & Vlasova, 1982)

Synonyms

Cyamus antarcticensis Vlasova in Berzin & Vlasova, 1982

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Orcinus orca (Linnaeus, 1758)

Geographic Range

Antarctica

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Pectoral fins, umbilicus (Berzin and Vlasova, 1982)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Isocyamus delphinii (Guérin-Méneville, 1836)

Synonyms

Cyamus delphinii Guérin-Méneville, 1836, C. globicipitis Lütken, 1870

Morphological Description

Barnard, 1932; Leung, 1967; Stock, 1973a; Stock, 1973b; Stock, 1977; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1991; Margolis et al., 2000; Lehnert et al., 2007; Lehnert et al., 2021

Molecular Sequences

COI (Lehnert et al., 2021)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Typically found on Globicephala melas (Traill, 1809); some records on Delphinus delphis Linnaeus, 1758, Grampus griseus (G. Cuvier, 1812), Lagenorhynchus albirostris (Gray, 1846), Phocoena phocoena (Linnaeus, 1758), and Pseudorca crassidens (Owen, 1846); once reported on Globicephala macrorhynchus Gray, 1846, Megaptera novaeangliae, Mesoplodon europaeus (Gervais, 1855), Peponocephala electra (Gray, 1846), Phocoena dioptrica Lahille, 1912, Steno bredanensis (G. Cuvier in Lesson, 1828), and Tursiops truncatus

Geographic Range

Arctic, Atlantic, Pacific, Mediterranean, Indian Ocean

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Ubiquitous; i.e., blowhole, eyes, jaw, insertion of pectoral fin, wounds (Stock, 1973a; Stock, 1977; Greenwood et al., 1979; Raga et al., 1988; Balbuena et al., 1989; Balbuena and Raga, 1991; Raga and Balbuena, 1993; Jauniaux et al., 2002; Lehnert et al., 2007; Batista et al., 2012; Lehnert et al., 2021)

Use as Indicator

The higher prevalence and intensity of I. delphinii on mature long-finned pilot whale males (vs. females and immature males) may identify the males that are dominant in sexual fights, given that the resulting wounds serve as shelter for this cyamid species (Balbuena and Raga, 1991; Raga and Balbuena, 1993).

Remarks

Lehnert et al. (2021) pose that some records around the 1970-90s misidentified this species and refer to Isocyamus deltobranchium Sedlak-Weinstein, 1992, which has triangular accessory gills (vs. cylindrical in I. delphinii).

References

Lütken, 1870; Lütken, 1893; Collet, 1912; Chevreux, 1913b; Hiro, 1938; Bowman, 1955; Sergeant, 1962; Leung, 1965; Stock, 1973a; Stock, 1973b; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Stock, 1977; Van Bree and Smeenk, 1978; Greenwood et al., 1979; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Raga et al., 1983a; Rappé, 1985; Raga et al., 1988; Balbuena et al., 1989; Mead, 1989; Rappé, 1991; Balbuena and Raga, 1991; Fransen and Smeenk, 1991; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1991; Raga and Balbuena, 1993; Abollo et al., 1998; Gibson et al., 1998; Margolis et al., 2000; Wardle et al., 2000; Haelters, 2001; Jauniaux et al., 2002; Haney et al., 2004; Lehnert et al., 2007; Batista et al., 2012; Lehnert et al., 2021; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Isocyamus deltobranchium (Sedlak-Weinstein, 1992)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Sedlak-Weinstein, 1992a; Martínez et al., 2008; Lehnert et al., 2021

Molecular Sequences

COI (Lehnert et al., 2021)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Phocoena phocoena; once reported on Delphinus delphis, Globicephala macrorhynchus, G. melas, Mesoplodon mirus True, 1913, and Orcinus orca

Geographic Range

Eastern North Atlantic, western north Pacific, Indian Ocean

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Skin wounds (Sedlak-Weinstein, 1992a; Martínez et al., 2008; Lehnert et al., 2021)

Use as Indicator

Higher prevalence in some harbor porpoise populations may reveal more interspecific contacts than in other areas (Lehnert et al., 2021). Also, temporal changes in prevalence could trace trends in the health status of cetacean hosts, given that it has been suggested that poor nutritional status may increase the susceptibility of porpoises to whale lice infections (Lehnert et al., 2021).

Remarks

Diatoms have been reported between I. deltobranchium forearms (Lehnert et al., 2021).

References

Sedlak-Weinstein, 1992a; Martínez et al., 2008; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018; Lehnert et al., 2021

Isocyamus indopacetus (Iwasa-Arai & Serejo, 2017)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017b; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018; Kobayashi et al., 2021

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Indopacetus pacificus (Longman, 1926)

Geographic Range

Japan, New Caledonia (western Pacific)

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Mouth, mammary slits, and scars provoked by Isistius sp. (Kobayashi et al., 2021)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017a; Kobayashi et al., 2021

Isocyamus kogiae (Sedlak-Weinstein, 1992)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Kogia breviceps (de Blainville, 1838)

Geographic Range

Australia (western South Pacific)

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Skin wounds (Sedlak-Weinstein, 1992b)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Neocyamus physeteris (Pouchet, 1888)

Synonyms

Cyamus fascicularis Verrill, 1901, C. physeteris Pouchet, 1888, Paracyamus physeteris (Pouchet, 1888)

Morphological Description

Pouchet, 1892; Leung, 1967; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Typically on Physeter macrocephalus; single record on Phocoenoides dalli (True, 1885)

Geographic Range

Eastern Pacific, Atlantic

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

-

Use as Indicator

Used to detect social segregation in sperm whales: females and male bachelors, but not large males, harbour N. physeteris, suggesting that the later leave their natal pods at puberty (Best, 1969a; Best, 1979).

Remarks

-

References

Pouchet, 1888; Pouchet, 1892; Verrill, 1902; Clarke, 1956; Margolis, 1959; Buzeta, 1963; Leung, 1965; Leung, 1967; Best, 1969a; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Best, 1979; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Mignucci-Giannoni et al., 1998; Margolis et al., 2000; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Orcinocyamus orcini (Leung, 1970)

Synonyms

Cyamus orcini Leung, 1970b

Morphological Description

Leung, 1970b; Margolis et al., 2000

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Orcinus orca

Geographic Range

Senegal (eastern South Atlantic)

Microhabitat

-

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Platycyamus flaviscutatus (Waller, 1989)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Berardius bairdii

Geographic Range

North Pacific

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Head, back, flanks, flukes (Waller, 1989)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Waller, 1989; Margolis et al., 2000

Platycyamus thompsoni (Gosse, 1855)

Synonyms

Cyamus thompsoni Gosse, 1855

Morphological Description

Gosse, 1855; Lütken, 1873; Wolff, 1958; Leung, 1967; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1991; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Typically on Hyperoodon ampullatus (Forster, 1770); once reported on H. planifrons Flower, 1882 and Mesoplodon grayi von Haast, 1876

Geographic Range

North Atlantic, Pacific, Antarctica

Life Cycle

At least four instars have been distinguished in females (Wolff, 1958). Males are more difficult to classify by morphological features and could die and fall off the whale after copulation (Wolff, 1958).

Microhabitat

Ubiquitous on skin, i.e., eyes, beak, corners of the mouth (Tomilin, 1957; Wolff, 1958; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1991)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Gosse, 1855; Lütken, 1870; Vosseler, 1889; Collet, 1912; Liouville, 1913; Tomilin, 1957; Wolff, 1958; Stock, 1973b; Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a; Berzin and Vlasova, 1982; Fransen and Smeenk, 1991; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1991; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Scutocyamus antipodensis (Lincoln & Hurley, 1980)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Cephalorhynchus hectori (Lacépède, 1804), Phocoena dioptrica, Sagmatias obscurus (Gray, 1828)

Geographic Range

Off Namibia (eastern South Atlantic) and New Zealand (western South Pacific)

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Ubiquitous on skin (Lincoln and Hurley, 1980; Best and Meÿer, 2010; Lehnert et al., 2017)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Lincoln and Hurley, 1980; Best and Meÿer, 2010; Lehnert et al., 2017

Scutocyamus parvus (Lincoln & Hurley, 1974)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Lagenorhynchus albirostris

Geographic Range

North Sea

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

-

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Lincoln and Hurley, 1974a, Lincoln and Hurley, 1974b; Stock, 1977; Fransen and Smeenk, 1991

Syncyamus aequus (Lincoln & Hurley, 1981)

Synonyms

See Remarks.

Morphological Description

Lincoln and Hurley, 1981; Raga, 1988; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1991

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Delphinus delphis, Stenella coeruleoalba; once reported on Sousa chinensis (Osbeck, 1765), Stenella longirostris (Gray, 1828), Tursiops aduncus (Ehrenberg, 1832 [1833]), and T. truncatus

Geographic Range

Mediterranean, western South Pacific, Indian Ocean

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Blowhole, eyes, corner of mouth, snout, jaw, axilla (Lincoln and Hurley, 1981; Raga and Raduan, 1982; Aznar et al., 1994; Cerioni and Mariniello, 1996; Haney, 1999; Haney et al., 2004; Fraija-Fernández et al., 2017)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

On the one hand, Mediterranean striped dolphins, Stenella coeruleoalba, harbored low prevalence and intensity of S. aequus (27% and 3 ind./host, respectively; Fraija-Fernández et al., 2017). Since striped dolphins are highly social animals (Carlucci et al., 2015), transmission success would be hardly hampered by the scarcity of contacts, but rather by the low sizes of source populations. These small populations may result from the extreme limitation of suitable microhabitats to shelter on these fast-swimming dolphins (Fraija-Fernández et al., 2017). This phenomenon seems also to impact the reproductive strategy of this species (Fraija-Fernández et al., 2017). On the other hand, the species Cyamus chelipes was first described by Costa (1866) and later re-classified in the genus Syncyamus by Bowman (1958). It is considered a nomen dubium (Haney, 1999), the type series is lost (Bowman, 1958), and it was not included in later reviews of the Cyamidae (Leung, 1965; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018|). Thus, it is possible that S. chelipes is a synonym of S. aequus, later described and common in the Mediterranean Sea (see above, Supplementary Table 1).

References

Lincoln and Hurley, 1981; Raga and Raduan, 1982; Raga et al., 1983; Raga and Carbonell, 1985; Raga, 1988; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1991; Aznar et al., 1994; Mariniello et al., 1994; Ross et al., 1994; Cerioni and Mariniello, 1996; Margolis et al., 2000; Fraija-Fernández et al., 2017

Syncyamus ilheusensis (Haney, de Almeida & Reid, 2004)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Haney et al., 2004; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017b; Iwasa-Arai and Serejo, 2018

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Globicephala macrorhynchus, Peponocephala electra, Stenella clymene (Gray, 1850)

Geographic Range

Brazil (western South Atlantic)

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Eyes, blowhole (Haney et al., 2004; Batista et al., 2012)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Haney et al., 2004; Batista et al., 2012; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2017a; Iwasa-Arai et al., 2018

Syncyamus pseudorcae (Bowman, 1955)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Delphinus delphis, Pseudorca crassidens, Stenella clymene

Geographic Range

North Atlantic, Pacific

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Blowhole, mouth, snout, jaw (Carvalho et al., 2010)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Bowman, 1955; Leung, 1970a; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1991; Jefferson et al., 1995; Carvalho et al., 2010

Order Isopoda Latreille, 1817

Family Cymothoidae Leach, 1818

Representatives from the family Cymothoidae are obligate parasites of mainly marine but also freshwater fish (Smit et al., 2014). Identification of cymothoid isopods is often difficult because species often show high morphological variation (Trilles et al., 2013). Many species of Nerocila Leach, 1818 require taxonomic revision (Aneesh et al., 2019).

Nerocila sp.

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

A general account of the genus Nerocila and of some of its species can be found Hai-yan and Xin-zheng (2002) and Trilles et al. (2013).

Molecular Sequences

COI, LSU rRNA, 16S rRNA, and 18S rRNA of nine Nerocila spp. (see GenBank)

Association

Unknown

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Pontoporia blainvillei (Gervais & d’Orbigny, 1844)

Geographic Range

-

Life Cycle

See Brusca (1978) and Smit et al. (2014) for a description of the cymothoid cycle.

Microhabitat

Neck region (Brownell, 1975)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

Brownell (1975) reported this ectoparasite on some La Plata dolphins that had been captured accidentally in gillnets, and interpreted that it could have been transmitted from sharks or other fish while all were trapped in the gillnet. Thus, the association with cetaceans should be viewed as accidental.

References

Class Thecostraca Gruvel, 1905

Subclass Copepoda Milne Edwards, 1840

Order Harpacticoida Sars G.O., 1903

Family Balaenophilidae Sars G.O., 1910

The genus Balaenophilus Aurivillius P.O.C., 1879 contains two species that live in close association with marine vertebrates. B. unisetus Aurivillius P.O.C., 1879 is considered an obligate commensal of baleen whales that feeds on algae and/or baleen tissue (Vervoort and Tranter, 1961; Fernandez-Leborans, 2001; Badillo et al., 2007), causing no harm to hosts (Ogawa et al., 1997; Badillo et al., 2007). In contrast, B. manatorum (Ortiz et al., 1992) infects manatees and sea turtles; in the latter they can feed on healthy skin (Badillo et al., 2007; Domènech et al., 2017), sometimes producing extensive lesions (Crespo-Picazo et al., 2017). Thus, this species is considered an ectoparasite.

Balaenophilus unisetus (Aurivillius P.O.C., 1879)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Aurivillius, 1879; Vervoort and Tranter, 1961; Bannister and Grindley, 1966

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Obligate commensal

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Balaenoptera borealis Lesson, 1828, B. edeni Anderson, 1878, B. musculus, B. physalus

Geographic Range

Arctic, Atlantic, eastern Pacific, Indian Ocean, Antarctica

Life Cycle

Aurivillius (1879) describes a nauplius and five copepodite stages preceding the adult phase. In the allied species B. manatorum nauplii and early copepodite stages are unable to swim, and copepodite V and adults can perform only short swimming excursions (Domènech et al., 2017). Thus, host bodily contact or closeness is likely necessary for transmission in both species.

Microhabitat

Baleen plates (Aurivillius, 1879; Cocks, 1885; Lillie, 1910; Scharff, 1913; Matthews, 1938b; Vervoort and Tranter, 1961; Rice, 1963; Gambell, 1964; Bannister and Grindley, 1966; Ichihara, 1966; Ichihara, 1978; Collet, 1986; Raga and Sanpera, 1986; Dalla Rosa and Secchi, 1997; Esteves et al., 2020), corner of the mouth (Raga and Sanpera, 1986)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

The presence of this species is likely underestimated since it can be easily overlooked without exhaustive inspection of baleen plates (Aurivillius, 1879; Vervoort and Tranter, 1961). It can sometimes be colonized by chonotrichous ciliates, acting as basibiont (Fernandez-Leborans, 2001).

References

Cocks, 1885; Aurivillius, 1879; Lillie, 1910; Collet, 1912; Scharff, 1913; Allen, 1916; Cornwall, 1927; Cornwall, 1928; Matthews, 1938b; Vervoort and Tranter, 1961; Rice, 1963; Gambell, 1964; Bannister and Grindley, 1966; Ichihara, 1966; Kawamura, 1969; Rice, 1977; Ichihara, 1978; Collet, 1986; Raga and Sanpera, 1986; Dalla Rosa and Secchi, 1997; Esteves et al., 2020

Family Harpacticidae Dana, 1846

Members of this family are mostly marine or brackishwater macroalgal associates, with a few freshwater species (Joon and Young, 1993).

Harpacticus pulex (Humes, 1964)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Unknown

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Tursiops truncatus

Geographic Range

-

Life Cycle

Unknown for this species, but naupliar and copepodite stages have been described for other Harpacticus spp. (e.g., Itô, 1976; Walker, 1981; Choi and Kim, 1994). Harpacticoids generally lack planktonic larval stages, but adults are active swimmers (e.g., Hicks, 1985; Palmer, 1988). It is thus plausible that transmission to bottlenose dolphin occurred during the adult phase.

Microhabitat

On ulcerated and sloughed skin (Humes, 1964)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

This species was described by Humes (1964) on captive marine mammals and has never been reported again. Species of Harpacticus Milne Edwards H., 1840 typically colonize seagrass, algal clumps or sandy and muddy bottoms (Ólafsson, 2001 and references therein), thus the occurrence of H. pulex on cetaceans is intriguing and perhaps forced by confinement conditions (Humes, 1964). Future re-examination of the taxonomic status of H. pulex is advisable.

References

Order Siphonostomatoida Burmeister, 1835

Family Caligidae Burmeister, 1835

The family Caligidae (“sea lice”) contains 30 genera (Walter and Boxshall, 2020); species of Caligus Müller O. F., 1785 and Lepeophtheirus Nordmann, 1832 have great economic relevance due to their impact on salmonid fish mariculture (Costello, 2006; Hemmingsen et al., 2020). Caligids use their siphon and a pair of mandibles to feed on fish skin (Kabata, 1974), causing ulcerations and even death to their hosts (Tørud and Håstein, 2008), but their impact on cetaceans has not yet been reported.

Caligus elongatus (Nordmann, 1832)

Synonyms

Caligus arcticus Brandes, 1956, C. kroyeri Milne Edwards, 1840, C. latifrons Wilson C.B., 1905, C. leptochilus Leuckart in Frey & Leuckart, 1847, C. lumpi Krøyer, 1863, C. rabidus Leigh-Sharpe, 1936, C. rissoanus Milne Edwards, 1840, C. trachypteri Krøyer, 1863

Morphological Description

Hemmingsen et al., 2020 and references therein

Molecular Sequences

COI (Øines and Heuch, 2005; Raupach et al., 2015; GenBank AY386272; AY386273; EF452647), 16S rRNA (Øines and Schram, 2008; GenBank AY660020), 18S rRNA (Huys et al., 2006; Øines and Schram, 2008; Mohrbeck et al., 2015; Khodami et al., 2017; GenBank JX845119-JX845131), 28S rRNA (Khodami et al., 2017; GenBank DQ180336; DQ180337; EU118301; EU118302)

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Balaenoptera acutorostrata, Hyperodoon ampullatus

Geographic Range

North Atlantic (Hemmingsen et al., 2020)

Life Cycle

Two free-living planktonic nauplius stages, one free-swimming infective copepodid stage, and four chalimus stages and one adult stage attached to the host (Maran et al., 2013).

Microhabitat

Skin (O’Reilly, 1998; Ólafsdóttir and Shinn, 2013)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

This is a typical fish ectoparasite that has been reported on more than 80 species (Kabata, 1979; Agusti-Ridaura et al., 2019). Infections in cetaceans are exceptional and likely related to their occurrence close to cage farms (Ólafsdóttir and Shinn, 2013). The hyperparasitic monogenean Udonella caligorum Johnston, 1835, which typically attaches to fish copepods (Freeman and Ogawa, 2010), has been found on C. elongatus infecting common minke whales (Ólafsdóttir and Shinn, 2013).

References

O’Reilly, 1998; Ólafsdóttir and Shinn, 2013

Caligus rufimaculatus (Wilson C.B., 1905)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Wilson, 1905; Takemoto and Luque, 2002; Kim et al., 2019

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Tursiops truncatus

Geographic Range

Western Atlantic (Benz et al., 2011)

Life Cycle

See C. elongatus (above).

Microhabitat

Skin (Benz et al., 2011)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

This species typically infects fish, but there is an exceptional record of adult individuals, including ovigerous females, on a carcass of bottlenose dolphin (Benz et al., 2011).

References

Lepeophtheirus crassus (Wilson & Bere, 1936)

Synonyms

Gloiopotes crassus Wilson & Bere, 1936

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Ectoparasite

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Delphinus delphis

Geographic Range

Western Atlantic, North Pacific, Indian Ocean (Lewis, 1967)

Life Cycle

Species of Lepeophtheirus have 2-4 chalimus stages and two preadult stages. The latter can be distinguished by their ability to detach and move over the surface of the host (Krøyer, 1834; see Hamre et al., 2013).

Microhabitat

Hyperparasitic on Remora australis (Bennett, 1840; Radford and Klawe, 1965)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Family Pennellidae Burmeister, 1835

Unlike other families of the order Siphonostomatoida, members of the family Pennellidae do have intermediate hosts, usually a fish or invertebrate (Kabata, 1979; Nagasawa et al., 1985; Suyama et al., 2021a and references therein). Mating seemingly occurs in the intermediate host and fertilized females attach to the final host in which they produce and release the eggs (Arroyo et al., 2002).

Pennella balaenoptera (Koren & Danielssen, 1877)

Synonyms

Pennella antarctica Quidor, 1913, P. anthonyi Quidor, 1913, P. balaenopterae Koren & Danielssen, 1877, P. cettei Quidor, 1913, P. charcoti Quidor, 1913

Morphological Description

Koren and Danielssen, 1877; Turner, 1905; Hogans, 1987, Hogans, 2017; Abaunza et al., 2001; Vecchione and Aznar, 2014; Suyama et al., 2021b

Molecular Sequences

COI (Fraija-Fernández et al., 2018)

Association

Mesoparasite. The head penetrates the blubber and musculature to feed on blood and expands as 2-3 cephalic horns in host’s tissue to enable attachment, whereas the trunk, genital complex, and abdominal plumes protrude and hang on the host body (Hogans, 1987; Abaunza et al., 2001; Schmidt and Roberts, 2009; Hogans, 2017).

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Balaenoptera acutorostrata, B. bonaerensis, B. borealis, B. edeni, B. musculus, B. physalus, Delphinus delphis, Eubalaena australis, Feresa attenuata Gray, 1874, Globicephala melas, Grampus griseus, Hyperoodon ampullatus, Kogia breviceps, Lissodelphis borealis (Peale, 1848), Megaptera novaeangliae, Mesoplodon bidens (Sowerby, 1804), M. carlhubbsi Moore, 1963, M. mirus, Orcinus orca, Phocoena phocoena, Physeter macrocephalus, Stenella coeruleoalba, Tursiops truncatus, Ziphius cavirostris

Geographic Range

Atlantic, Pacific, Mediterranean, Indian Ocean, Antarctica

Life Cycle

Based on information from other penellids, its life cycle is believed to include a pelagic naupliar stage and several copepodid and chalimus instars on the intermediate (squid) hosts; females are fertilized as late chalimi and undergo a pelagic phase to search out the definitive host, where they metamorphose into the adult stage (Schmidt and Roberts, 2009). In the case of P. balaenoptera, only adult females and the first naupliar stage are known (Arroyo et al., 2002). However, the copepodid and chalimus stages have been described for P. filosa (Linnaeus, 1758) collected from squids (Rose and Hamon, 1953; see also Arroyo et al., 2002), and P. filosa is now considered conspecific with P. balaenoptera (Fraija-Fernández et al., 2018; see also the Discussion). The life cycle of P. balaenoptera could be primarily oceanic because this species is more prevalent on pelagic versus coastal cetaceans (Fraija-Fernández et al., 2018).

Microhabitat

Commonly on the flanks (Raga and Sanpera, 1986; Aznar et al., 1994; Gomerčić et al., 2006; Souza et al., 2005; Ciçek et al., 2007; Foskolos et al., 2017), but occasionally reported on the head (Pouchet and Beauregard, 1889; Foskolos et al., 2017) and flukes (Foskolos et al., 2017). A single record on a whale sucker, Remora australis (Bennett, 1840) attached to a dolphin (Radford and Klawe, 1965).

Use as Indicator

It may be an indicator of compromised health in cetacean hosts (Mackintosh and Wheeler, 1929; Aznar et al., 2005; Vecchione and Aznar, 2014).

Remarks

Since P. balaenoptera is the only recognized species of Pennella Oken, 1815 parasitizing cetaceans, we consider that the published records of Pennella sp. in cetaceans could be assigned to this species, unless proven otherwise. Dailey et al. (2002) reported P. balaenoptera in one northern elephant seal, Mirounga angustirostris (Gill, 1866). Recently, molecular analyses revealed that specimens of P. balaenoptera collected from several cetaceans in western Mediterranean could be conspecific with P. filosa from swordfish, Xiphias gladius Linnaeus, 1758, collected in the same area (Fraija-Fernández et al., 2018). This finding begs further attention (see the Discussion).

References

Steenstrup and Lütken, 1861; Sars, 1866; Pouchet and Beauregard, 1889; Anthony and Calvet, 1905; Turner, 1905; Bouvier, 1910; Japha, 1910; Mörch, 1911; Collet, 1912; Quidor, 1912; Liouville, 1913; Olsen, 1913; Scharff, 1913; Cornwall, 1927; Cornwall, 1928; Mackintosh and Wheeler, 1929; Van Oorde-de Lint and Schuurmans-Stekhoven, 1936; Matthews, 1938b; Allen, 1941; Stephensen, 1942; Mizue, 1950; Nishiwaki and Hayashi, 1950; Mizue and Murata, 1951; Nishiwaki and Oye, 1951; Ohno and Fujino, 1952; Kakuwa et al., 1953; Barnard, 1955; Chapman and Santler, 1955; Clarke, 1956; Zenkovich, 1956; Tomilin, 1957; Rice, 1963; Radford and Klawe, 1965; Kawamura, 1969; Berzin, 1972; Rice, 1977; Rice, 1978; Dailey and Stroud, 1978; Dailey and Walker, 1978; Ivashin and Golubovsky, 1978; Greenwood et al., 1979; Best, 1982; Raga and Carbonell, 1985; Raga and Sanpera, 1986; Smiddy, 1986; Mead, 1989; Bushuev, 1990; Dorsey et al., 1990; Sedlak-Weinstein, 1990 (unpubl.); Dailey and Vogelbein, 1991; Raga and Balbuena, 1993; Aznar et al., 1994; Aznar et al., 2005, unpubl.; Raga, 1994; Vecchione, 1994; Cerioni and Mariniello, 1996; Kuramochi et al., 1996; Araki et al., 1997; Kuramochi et al., 2000; McAlpine et al., 1997; Terasawa et al., 1997; Uchida, 1998; Walker and Hanson, 1999; Cornaglia et al., 2000; Uchida and Araki, 2000; Abaunza et al., 2001; Arroyo et al., 2002; Brzica, 2004; Gomerčić et al., 2006; Souza et al., 2005; Ciçek et al., 2007; Kautek et al., 2008; Martín et al., 2011; Rosso et al., 2011; Bertulli et al., 2012; Ólafsdóttir and Shinn, 2013; Tonay and Dede, 2013; Danyer et al., 2014; Öztürk et al., 2015; Delaney et al., 2016; Birincioğlu et al., 2017; Foskolos et al., 2017; Hogans, 2017; Fraija-Fernández et al., 2018; IJsseldijk et al., 2018; Marcer et al., 2019; Methion and Díaz López, 2019; Herr et al., 2020; Orrell, 2020; Ten et al., unpubl.

Subclass Cirripedia Burmeister, 1834

Order Balanomorpha Pilsbry, 1916

Family Balanidae Leach, 1817

Thoracic barnacles (Infraclass Thoracica) are sessile, hermaphroditic crustaceans that attach to diverse substrata and have specialized cirri to filter organic particles from water for feeding (Anderson, 1994). The life cycle typically includes a free-swimming nauplius larva that undergoes several (usually 6) moults, and a non-feeding cypris larva that searchs out, and attaches to, an appropriate substratum. Subsequent metamorphosis leads to a juvenile filter-feeding version of the adult (Darwin, 1854; Cornwall, 1955; Maruzzo et al., 2012). The cyprid stage is unique to barnacles and shows little morphological variability across species, even though they can attach to strikingly different substrata (Maruzzo et al., 2012; Dreyer et al., 2020).

This family originally encompassed all sessile barnacles (Leach, 1817), but whale barnacles and most sea turtles were later re-classified (Pitombo, 2004; see below). Most members of Balanidae are intertidal, although some species are facultative epibionts, e.g., those found on sea turtles, such as Balanus trigonus (Ten et al., 2019).

Balanus trigonus (Darwin, 1854)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

COI (Chen et al., 2013; Ashton et al., 2016; GenBank JQ035523; JQ035524; MF974362; MK308152; MK308163; MK308322; MK496572; MT258956; MW277718; MW277822), EF1a (Chan et al., 2017), RPII (Chan et al., 2017), 12S rRNA (Endo et al., 2010; Kamiya et al., 2012; Pérez-Losada et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2017; GenBank GU983669; GU983670), 16S rRNA (Chan et al., 2017; GenBank JQ035491; JQ035492), 18S rRNA (Pérez-Losada et al., 2014; Chan et al., 2017), 28S rRNA (Pérez-Losada et al., 2014), and the complete mitochondrial genome (GenBank MW646099; MZ049958; NC_056392)

Association

Facultative commensal

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Megaptera novaeangliae

Geographic Range

Cosmopolitan (Werner, 1967)

Life Cycle

Metamorphosis from nauplius to cyprid stage is speeded up at higher water temperature, i.e., 4-11 days (Thiyagarajan et al., 2003). Recruitment is seasonal and takes place at approximately 24°C (Lam, 2000).

Microhabitat

As a hyperepibiont on the barnacle Coronula diadema (Cornwall, 1928)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Balanus spp.

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

A general account of Balanus spp. can be found in Darwin (1854); Newman and Ross (1976), and Pitombo (2004).

Molecular Sequences

> 5,000 results in GenBank

Association

Presumably facultative commensal

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Megaptera novaeangliae

Geographic Range

-

Life Cycle

Information for Balanus spp. is available from Brown and Roughgarden (1985) and Maruzzo et al. (2012).

Microhabitat

As a hyperepibiont on the barnacle Coronula spp. (Rice, 1963)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

Balanus spp., as in Rice (1963), may correspond to a single or several species.

References

Megabalanus tintinnabulum (Linnaeus, 1758)

Synonyms

Balanus tintinnabulum (Linnaeus, 1758), Lepas tintinnabulum Linnaeus, 1758

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

COI (Chen et al., 2013; Ashton et al., 2016; GenBank JQ035525-JQ035527), H3 (Pérez-Losada et al., 2004), 12S rRNA (Pérez-Losada et al., 2004), 16S rRNA (Pérez-Losada et al., 2004; GenBank JQ035505-JQ035508), 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA (Pérez-Losada et al., 2004), and the complete mitochondrial genome (Che et al., 2019; GenBank MW281857; NC_056162)

Association

Facultative commensal

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Unidentified whale

Geographic Range

Tropical or sub-tropical to warm temperate waters (Otani et al., 2007)

Life Cycle

In the Arabian Sea, barnacles breed at lower temperatures, i.e., less than 24 °C in winter vs. > 28 °C in summer; and grow at a rate of 0.44-0.63 mm/year (Ali and Ayub, 2021).

Microhabitat

As a hyperepibiont on the barnacle Coronula diadema (Barnard, 1924)

Use as Indicator

-

Remarks

-

References

Family Coronulidae Leach, 1817

Coronulids are typically obligate epibionts of sea turtles, sirenians or cetaceans (Marlow, 1962; Hayashi et al., 2013). One species, Chelonibia testudinaria (Linnaeus, 1758), can also be found on crustaceans and sea snakes, and even on inanimate substrata (Frazier and Margaritoulis, 1990; Cheang et al., 2013).

Cetopirus complanatus (Mörch, 1852)

Synonyms

Coronula balaenaris (Gmelin, 1791), C. complanata (Mörch, 1852)

Morphological Description

Darwin, 1854; Pilsbry, 1916; Scarff, 1986; Pastorino and Griffin, 1996; Seilacher, 2005

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Obligate commensal

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Eubalaena australis, E. glacialis

Geographic Range

Arctic, Atlantic, eastern North Pacific, Antarctica

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Lips, fins (Guiler, 1956; Best, 1991)

Use as Indicator

Shell plate remains of C. complanatus in Nerja Cave (Málaga, southern Spain) were used as indirect evidence of whale consumption by humans in the Upper Magdalenian (Álvarez-Fernández et al., 2013) and of the presence and migration of right whales (Balaenidae) in the Mediterranean during the Early Pleistocene (Collareta et al., 2016; Bosselaers et al., 2017).

Remarks

There is a single record on Megaptera novaeangliae (Guiler, 1956), but it was probably confused with Coronula reginae (Holthuis et al., 1998).

References

Chemnitz, 1785; Chemnitz and Martini, 1790; Darwin, 1854; Gruvel, 1903; Pilsbry, 1916; Nilsson-Cantell, 1931; Best, 1991

Coronula diadema (Linnaeus, 1767)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Darwin, 1854; Dall, 1872; Cornwall, 1955; Scarff, 1986; Anderson, 1994

Molecular Sequences

H3, 12S rRNA, 16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA (Hayashi et al., 2013)

Association

Obligate commensal

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Typical from Megaptera novaeangliae but some records on Balaenoptera bonaerensis, B. borealis, B. musculus, B. physalus, Eubalaena glacialis, Hyperoodon ampullatus and Physeter macrocephalus

Geographic Range

Atlantic, Pacific, Indian Ocean, Antarctica

Life Cycle

A one-year life cycle has been proposed (Angot, 1951; Newman and Abbott, 1980). Larval release and settlement seem to occur in warm waters (20-25°C in September-October off Madagascar), whereas adult development may take place during whale migration to the poles (Angot, 1951). Details of development from the embryo to the juvenile stage have been studied in vitro (Nogata and Matsumura, 2006). Larval settlement is likely induced by chemical cues from whale skin, such as alpha-2-macroglobulin (Nogata and Matsumura, 2006).

Microhabitat

Rostrum, lips, lower jaw, fins (Dall, 1872; Pilsbry, 1916; Nilsson-Cantell, 1930a, Nilsson-Cantell, 1930c; Stephensen, 1938; Scheffer, 1939; Tomilin, 1957; Scarff, 1986)

Use as Indicator

Isotope analyses (δ18O) of shells of C. diadema and its direct ancestor C. bifida (Dominici et al., 2011) accurately trace current and Pleistocene-Miocene whale migration routes (Buckeridge et al., 2018; Collareta et al., 2018a; Collareta et al., 2018b; Buckeridge et al., 2019; Taylor et al., 2019). Fossil remains have also been used to infer humpback whale migration routes and breeding areas in the Late Pliocene-Pleistocene (Bianucci et al., 2006a; Bianucci et al., 2006b). Present-day observations of Coronula sp. (Olsen, 1913; Angot, 1951) helped to elucidate right whales’ migration from warmer waters (Best, 1991). The co-occurrence of C. bifida with Cetopirus complanatus may indicate that whales belonging to Balaenopteridae and Balaenidae shared breeding grounds during the Early Pleistocene (Collareta et al., 2016). Interestingly, the presence of C. diadema on cetaceans other than humpback whales could also indicate some geographical overlap between species (see the Discussion). Coronula spp. have been suggested as natural marks for individual photo-identification (Franklin et al., 2020). The pattern of attachment of barnacles (presumably C. diadema) indicates non-uniform water flow over humpback whale flippers and has shed light on the function of leading-edge tubercles (Fish and Battle, 1995). Rubbing against rocks and the sea bottom has been observed in humpback whales, which may be an attempt to remove these barnacles (Tomilin, 1957) and could limit its application as an indicator.

Remarks

This species serves as a basibiont of the facultative epibionts Balanus spp., Conchoderma auritum (Linnaeus, 1767), and Megabalanus tintinnabulum, and of the hydroid Obelia dichotoma (Linnaeus, 1758) (Liouville, 1913; Barnard, 1924; Cornwall, 1928; Stephensen, 1938; Rice, 1963; Kim et al., 2020).

References

Dall, 1872; Scammon, 1874; Fischer, 1884; Sars, 1890-1895; Borradaile, 1903; Liouville, 1913; Pilsbry, 1916; Cornwall, 1924; Cornwall, 1927; Cornwall, 1928; Nilsson-Cantell, 1930a; Nilsson-Cantell, 1930c, Hiro, 1935; Hiro, 1938; Stephensen, 1938; Nilsson-Cantell, 1939; Scheffer, 1939; Mizue and Murata, 1951; Rees, 1953; Tomilin, 1957; Nishiwaki, 1959; Cockrill, 1960; Wolff, 1960; Rice, 1963; Nilsson-Cantell, 1978; O’Riordan, 1979; Scarff, 1986; Paterson and Van Dyck, 1991; Young, 1991; Holthuis and Fransen, 2004; Félix et al., 2006; Nogata and Matsumura, 2006; Wirtz et al., 2006; Jones, 2010; Ávila et al., 2011; Jiménez et al., 2011; Hayashi, 2012; Angeletti et al., 2014; Kim et al., 2020; Minton et al., 2020 (in press.); Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, 2020; Ueda, 2020; Ten et al., unpubl.

Coronula reginae (Darwin, 1854)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Molecular Sequences

-

Association

Obligate commensal

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Balaenoptera bonaerensis, B. borealis, B. musculus, B. physalus, Eubalaena glacialis, Megaptera novaeangliae; single report on Delphinapterus leucas and Physeter macrocephalus

Geographic Range

Arctic, Atlantic, North Pacific, Indian Ocean, Antarctica

Life Cycle

-

Microhabitat

Lower jaw, flukes (Cockrill, 1960; Scarff, 1986)

Use as Indicator

See Coronula diadema (above).

Remarks

-

References

Collet, 1912; Pilsbry, 1916; Cornwall, 1927; Cornwall, 1928; Mackintosh and Wheeler, 1929; Nilsson-Cantell, 1930a; Nilsson-Cantell, 1930b; Hiro, 1938; Stephensen, 1938; Scheffer, 1939; Rees, 1953; Guiler, 1956; Tomilin, 1957; Cockrill, 1960; Rice, 1963; Klinkhart, 1966; Kawamura, 1969; Rice, 1977; Nilsson-Cantell, 1978; Silva-Brum, 1985; Scarff, 1986; Bushuev, 1990; Smiddy and Berrow, 1992; Holthuis and Fransen, 2004; Ten et al., unpubl.

Cryptolepas rhachianecti (Dall, 1872)

Synonyms

-

Morphological Description

Dall, 1872; Cornwall, 1955; Achituv, 1998; Seilacher, 2005

Molecular Sequences

H3, 12S rRNA, 16S rRNA, 18S rRNA, 28S rRNA (Hayashi et al., 2013)

Association

Obligate commensal, although Tomilin (1957) considered this species to be potentially harmful because it can impede whales’ movement and damage their skin.

Cetacean Hosts/Basibionts

Eschrichtius robustus; once reported on Delphinapterus leucas and Orcinus orca

Geographic Range

North Pacific; one record in the Gulf of Mexico (eastern North Atlantic)

Life Cycle

Gray whales wintering in waters off California and Mexico bear large and small specimens of C. rhachianecti when migrating northward, but only large barnacles when sighted during the southbound migration (Rice and Wolman, 1971). This would suggest that larval settlement occurs in wintering areas. This interpretation is supported by the observation that belugas held captive in San Diego Bay have C. rhachianecti in synchrony with gray whale northward migration (Rice and Wolman, 1971; Ridgway et al., 1997). Vertical shell growth is 0.12 mm/day (Killingley, 1980).

Microhabitat

Rostrum, lips, throat, peduncle, fins (Kasuya and Rice, 1970; Briggs and Morejohn, 1972)

Use as Indicator