- Law School of Dalian Maritime University, Dalian, China

China has adopted a domestic approach to the compensation fund for ship-induced oil pollution damage by establishing the Chinese Ship-induced Oil Pollution Compensation (CSOPC) Fund. After almost 10 years of practice, there are still opinions and questions regarding the rationality of China’s domestic approach. This study reassesses China’s domestic approach by a two-dimensional analysis of the current position and potential developments of the CSOPC Fund’s functions in pollution governance and victim compensation. At the present stage, the goal of adequate compensation to victims is not well achieved by the CSOPC Fund when compared to its other goal of ensuring a better oil pollution emergency reaction. Given that the International Oil Pollution Compensation (IOPC) Fund is unlikely to contribute much to pollution governance, and the current inadequacy and defects of the CSOPC Fund can be improved gradually, it is suggested that China should continue its domestic approach with necessary improvements. Using the CSOPC Fund’s practice as a case study, this research intends to explore the pollution governance side of the compensation fund that has not yet been fully addressed, demonstrating the key value of the domestic fund compared to the IOPC Fund.

Introduction

The international civil liability regime for marine oil pollution is recognized as a typical “smart mix”: the compensation is provided on the one hand via the (limited) liability of the tanker owner based on the 1969 International Convention on Civil Liability for Oil Pollution Damage (hereinafter, CLC) and its 1984 and 1992 Protocols (the amended CLC is also known as the 1992 CLC, hereinafter, 1992 CLC) and on the other hand via the oil receivers through the 1971 International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage (ceased to be enforced on May 24, 2002) and its 1992 Protocol (hereinafter, 1992 Fund Convention) (Faure and Wang, 2019). Owing to the cooperation of the Governments of the Member States as well as the shipowners, Protection and Indemnity (P&I) clubs, and the oil industry, the oil pollution compensation system has worked remarkably well (Jacobsson, 1994, 361; Shaw, 2013).

However, the success of the international regime does not necessarily mean that the international approach is the best option and shall be the only choice for every country. In practice, at least two other options are adopted by countries for the compensation fund for the ship-induced oil pollution damage. The first is to establish a domestic compensation fund for the ship-induced oil pollution damage, a well-known example of which is the Oil Spill Liability Trust Fund (OSLTF) as set by the Oil Pollution Act (1990). The other is to adopt a combination of the international and domestic regime, an example of which is Canada—while being a contracting party to the 1992 Fund Convention, it retains its domestic Ship-Source Oil Pollution Fund providing financial protection for the situations not covered by the present international regime, as well as additional compensation for oil spills from laden tankers covered by the international conventions.

As the biggest oil importer in the world, China has acceded to the 1969 CLC and its 1992 Protocol, but is not a Member State of the Fund Convention. Instead, China adopted a domestic approach to establish the Chinese Ship-induced Oil Pollution Compensation (CSOPC) Fund in 2012 by the regulation of Administrative Measures for the Collection and Use of Compensation Funds for ship-induced Oil Pollution Damage (hereinafter, Fund Administrative Measures). After almost 10 years of practice, the CSOPC Fund has shaped a unique practice that is similar to, but also different from, the International Oil Pollution Compensation (IOPC) Fund. However, the rationality of adopting a domestic approach for the oil pollution compensation fund is still not self-evident. On the one hand, the gap is quite evident between the CSOPC and IOPC Funds in terms of the protection capabilities; that is, for the CSOPC Fund, the maximum compensation amount payable is ¥30 million for a single vessel-induced oil pollution accident, and for the IOPC Fund, the maximum amount of compensation payable under the 1992 Fund Convention for any one incident is SDR 135 million for incidents that occurred before November 1, 2003, and SDR 203 million for incidents that occurred later. On the other hand, regarding the levy rate imposed on oil receivers, the annual contribution rates (per ton) of the IOPC Fund from 2015 to 2019 were £0.002906, £0.0062582, £0.00097341, £0.0037193, and £0.0014586, respectively (IOPC, 2021), lower than the fixed ¥0.3 as prescribed by the Fund Administrative Measures in most years. It is also worth noting that unlike the IOPC Fund that only requires contributions from receivers who have received total quantities exceeding 150,000 tons, all receivers in China are subject to the obligation of contributing to the CSOPC Fund despite the import quantities.

The above comparison may lead to the following conclusion: the CSOPC Fund currently levies a higher rate but its protection level is not as desirable as that of the IOPC Fund, and it is thus better for China to abandon the domestic approach and adopt the IOPC Fund. Some previous studies have also reported that for countries with a high risk of exposure to oil spills like China, it is better to join the IOPC Fund from the perspective of sharing both the risks and financial losses (Dong et al., 2015; Hao, 2019). In this regard, after almost 10 years of practice, it is still imperative to reassess whether China’s domestic approach concerning the ship-induced oil pollution compensation fund is reasonable by identifying the key characteristics and challenges of the CSOPC Fund. Such a reassessment is not only needed for further policymaking and the mechanism perfection of China’s practice regarding the compensation fund but also can set a good example to demonstrate the key considerations in making the path choice between the domestic or international compensation fund for pollution damage.

Literature Review

The major reason for China’s choice of domestic approach on a compensation fund for ship-induced oil pollution damage is largely explained by Hu (2005, 164): after it transitioned to an oil importing country in 1993, China believed that the acceptance of the IOPC Fund would lead to more cost than benefit since Chinese oil importers would have to make a significant contribution to the organization. However, this was the initial consideration before the enactment of the Fund Administrative Measures. After the enactment of the Fund Administrative Measures in 2012, more studies were carried out regarding the CSOPC Fund. However, besides the two above-mentioned papers by Dong and Hao advising China to join the IOPC Fund for the purpose of better sharing of risk and financial losses, no other studies attempted to reassess the rationalities of the domestic approach. Although many studies have compared the legislation and practice of the CSOPC and IOPC Funds, their primary intention has been to improve the CSOPC Fund by borrowing the successful experience of the IOPC Fund. For example, by analyzing and summarizing the operational mechanism of the IOPC Fund, it is suggested that the CSOPC Fund shall review ship oil pollution accident data systematically, broaden the compensation scope, and increase the compensation limit (Shuai, 2019); by learning from the mature experience of the IOPC Fund in cooperating with insurers of shipowners, recommendations are made to unify the compensation scope and items between the insurance of the shipowner and CSOPC Fund (Yang and Zhu, 2017). These researches contend that the domestic approach shall be insisted, and imply that the IOPC Fund is more favorable than the CSOPC Fund in certain aspects. Thus, despite the brief financial and risk-sharing considerations, the rationality or irrationality of the domestic approach in establishing the CSOPC Fund is not fully assessed.

Meanwhile, extending the literature review scope to other jurisdictions where the domestic approach is also adopted, the discussion regarding the choice of domestic funds is also very limited. Pieces of analysis can be found in some researches regarding the legal regime of the liability of oil pollution, and the reasons for United States’ refusal in joining the IOPC Fund are briefly mentioned as following: the political issue of whether the US state oil pollution statutes would be pre-empted by the international conventions, leaving open the potential for uncompensated damage claims in the event of a major oil spill (Donaldson, 1992); the significant differences between the international and domestic regimes in the liability limit of a responsible party and the scope of recoverable damages (Kim, 2003); and the need for expanded geographic coverage (Wagner, 1990). Although studies have reviewed the domestic funds of United States and Canada after 10 or 20 years of practice (Troop and Greenham, 1991; Kiern, 2000; Woods, 2009), no comprehensive study has reassessed the rationality or key values of the domestic funds.

Summarizing the previous academic research, the burden of financial contribution and compensation adequacy are viewed as the main reason for establishing the domestic compensation fund for ship-induced oil pollution damage. This makes sense as the primary goal of introducing the second layer of compensation is to provide full and adequate compensation to victims in oil pollution accidents by way of placing part of the economic consequences of oil pollution damage to the oil cargo interests. However, focusing on the contribution and compensation side of the fund is onefold and incomprehensive to some extent. For the domestic fund, as it is more integrated into the national governance regime of ship-induced oil pollution, its role in pollution governance shall not be overlooked. The contribution of the domestic fund in achieving better pollution governance is mentioned in some research, such as finding the changing relationship between the Coast Guard and responsible parties with the separate emergency fund set up by the OSLTF: the Coast Guard gained the financial capacity to undertake the removal action itself if a responsible party is not identified, in the event of a “mystery spill,” or if the Coast Guard is not satisfied with the actions of the responsible party (Kiern, 2000, 545). However, this function is not fully and well discussed.

This study attempts to use the CSOPC Fund’s practice as a case study to explore the function of pollution governance of the domestic fund, demonstrate the key value of the domestic fund compared with the international fund, and reassess whether the domestic approach of China shall be continued by a two-dimensional analysis of its achievement and potential in pollution governance and victim compensation.

Pollution Governance of the Chinese Ship-Induced Oil Pollution Compensation Fund

Being part of the oil pollution compensation regime caused by ships, the CSOPC Fund undertakes the role of pollution governance from its establishment. This is embodied in Article 1 of the Fund Administrative Measures, which states that the purpose of establishing the CSOPC Fund is to protect China’s marine environment and enhance the maritime transport industry’s sustainable and healthy development; this is significantly different from the purpose of the IOPC Fund embodied in the preamble of the 1992 Fund Convention. To be specific, the pollution governance considerations have been considered especially in the compensation scope and consequence of the CSOPC Fund, and can be further explored by the construction of a unified ship-induced pollution damage compensation fund.

Prioritize the Compensation Sequence of Emergence Response Costs

Different from the proportional compensation model adopted by the IOPC Fund, the CSOPC Fund adopts a sequential compensation model, where claims involved in the same accident are compensated in the following sequence as per Article 17 of the Fund Administrative Measures: (1) emergency response costs incurred for reducing oil pollution damage; (2) expenses incurred for controlling or removing pollution; (3) direct economic losses caused to the fishery and tourist industries; (4) expenses incurred for measures taken to recover marine ecology and natural fishery resources; (5) expenses incurred during the surveillance and monitoring activities conducted by the Management Committee of the CSOPC Fund; and (6) other expenses approved by the State Council. This sequential order demonstrates the policy considerations embodied in the priority of the compensation sequence. Emergency response costs, especially, are compensated first to encourage fast emergency responses for the containment of oil pollution damage. By ensuring the compensation of the cost, the parties organizing and participating in the emergency response actions can be assured to take up works.

The priority in compensation for oil pollution emergency response costs is consistent with the oil pollution governance need of China, which ensures rapid and efficient coordination of oil pollution emergency treatment. In China, the Maritime Safety Administration (MSA) is responsible for the duty to coordinate with the commercial clean-up companies in oil spill accidents, however, MSA has long been in trouble with the potential claims against it with the unpaid clean-up fees. For instance, in the case of “Zhongheng 9,” the clean-up company was decided entitled to claim its clean-up cost against the MSA as it has an entrusting relationship with the MSA under the clean-up operation entrusted by the MSA (Hubei Higher People’s Court, 2018). By prioritizing the compensation of those clean-up fees, clean-up companies can recover from the CSOPC Fund first, which reduces the chances of being chased. Thus, it will be easier for MSA to deal with oil pollution accidents with the financial guarantee provided by the CSOPC Fund.

Furthermore, in the revision of the Fund Administrative Measures, advance payment rules may be introduced for emergency response costs. This may help solve the financial difficulties faced by oil pollution emergency response entities in case of a major oil pollution accident. This suggestion is also noted in the revision of the Chinese Maritime Code; in its latest draft, which has not been made public, the following Article has been introduced: “the necessary expenses incurred by relevant entities under the organization of government for the emergency response to oil pollution accidents may be paid in advance from the compensation fund.” This proposal, consistent with the aforesaid considerations to ensure the clean-up operation’s efficiency, also reflects the policy consideration in responding to the demands of clean-up practices for better pollution control at the early stage of the accidents.

A Broader Scope and Circumstances of Accidents Covered by the Chinese Ship-Induced Oil Pollution Compensation Fund

International conventions have an inevitably limited scope of application as they involve the consensus of different countries, similar to the case with the IOPC Fund as shown by its limited definitions of oil and ships covered by it. Contrastingly, the application scope of the domestic fund is less limited, where the domestic pollution governance needs can be met systematically. For instance, the oil pollution covered by the OSLTF includes pollution caused by “oil of any kind or form, including, but not limited to petroleum, fuel oil sludge, oil refuse, and oil mixed with wastes other than dredged spoil,” and its geographic scope is also broad, including ocean, coastal, and inland waters of the United States. It reaches beyond general maritime “navigable waters” and includes all surface waters of the United States (Lawrence I. Kiern, 1994, 495). As for the CSOPC Fund, its compensation scope is also broader than that of the IOPC Fund, which makes the CSOPC Fund available for the losses and expenses caused by more categories of oils and accidents, especially ensuring the compensation of relevant pollution response costs in more pollution accidents. The broader scope and circumstances of accidents covered by the CSOPC Fund is further illustrated in the following three aspects.

First, the CSOPC Fund has a broader scope of application to ships that cause oil pollution accidents. The 1992 Fund Convention, in conformity with the 1992 CLC, applies to any sea-going vessel and seaborne craft of any type constructed or adapted for the carriage of oil in bulk as cargo, provided that a ship capable of carrying oil and other cargoes shall be regarded as a ship only when it is actually carrying oil in bulk as cargo and during any voyage following such carriage unless it is proven that it has no residues of such carriage of oil in bulk aboard. In comparison, the CSOPC Fund has no such limit: the 2020 Compensation Guidelines of the CSOPC Fund (hereinafter, Compensation Guidelines) stipulate that the fund applies to any vessel with exceptions only to vessels used by governments for non-commercial purposes, military vessels or fishing vessels, offshore oil platforms, and floating oil storage devices that are not registered as ships (CSOPC Fund, 2021b).

Second, the CSOPC Fund applies to a wider scope of “oil” that causes pollution. Conforming to the 1992 CLC, the IOPC Fund only compensates those who suffer from oil pollution damage resulting from spills of persistent oil as defined in the convention from tankers as per Article 5 (1) of 1992 CLC. Contrastingly, the oil pollution accidents covered by the CSOPC Fund include any occurrence or a series of occurrences causing oil pollution damage resulting from the vessel’s leakage of persistent oil substances, non-persistent oil substances, fuel oil, and their residues, or, if there is no leakage, posing serious and urgent dangers of oil pollution damage (CSOPC Fund, 2021b). Therefore, pollution accidents arising from non-persistent oil are compensated by the CSOPC Fund, although no levy is imposed on the receivers of the non-persistent oil.

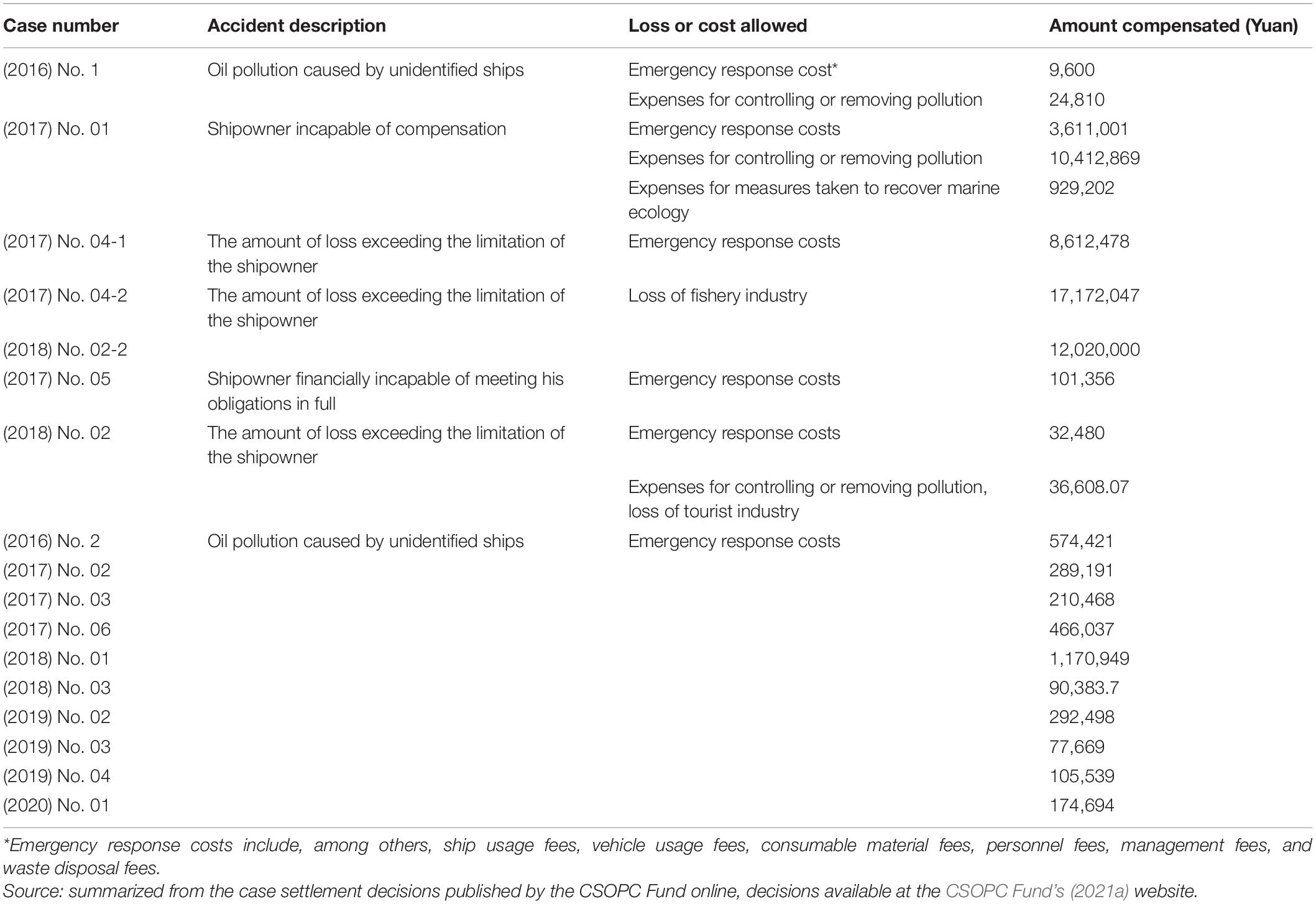

Last, the CSOPC Fund specifically lists the damage resulting from unidentified ships as one of the situations that qualify for fund compensation application. Although it is argued that pollution from an unidentified ship can be classified as a case, and the IOPC Fund has been prepared to accept a claim as admissible, a claim will nevertheless fail if it cannot be shown that an oil tanker was the source of the spill (De la Rue and Anderson, 2009, 430). Given its wider application to the scope of “oils” and “ships” as mentioned above, the CSOPC Fund is more likely to provide cover for the victims in circumstances where the ship causing the pollution is unidentifiable. This is evidenced by the fact that among the 17 claims settlement decisions made by the CSOPC Fund, the number of claims of oil pollution damage caused by an unidentified ship has reached 11 (see Table 1), which demonstrates the practical value to list this claim situation.

Simplified Decision-Making Mechanism

As it is based on international conventions, the international fund has to consider the practices and demands of different countries, making it unable to consider every need of the contracting states. Contrarily, as the domestic fund is established based on domestic laws, it can focus better on its domestic practical considerations, being easier in its policymaking. This is especially embodied in the fact that the decision-making mechanism of domestic funds is simplified as the trouble of international coordination is saved. For example, under OSLTF, upon the request of the governor of a state or pursuant to an agreement with a state, the President may obligate the Fund for payment within $250,000 for costs for immediate removal of a discharge or the mitigation or removal of a substantial threat of a discharge of oil. Also, for CSOPC Fund, the initiation of the amendment of Fund Administrative Measures will be easier than the amendment of Fund Convention, and interim measures relating to the management of the fund can be taken more easily to meet the changing domestic situations. An example of this is the alleviation of the financial burden of oil companies during the epidemic. The Ministries of Transport and Finance have halved the levy rates of the CSOPC Fund from March 1 to December 31, 2020 by announcements (Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Finance of PRC, 2020).

Possibility of a Unified Ship-Induced Pollution Damage Compensation Fund

Suggestions are also being made to expand the coverage of the CSOPC Fund to other ship-induced pollutions to realize more systematic governance of oil pollution in China. As argued by scholars, the ultimate goal of the CSOPC Fund should establish a comprehensive ship-induced pollution damage compensation fund after gaining sufficient experience so that more victims of ship-induced pollution can receive scientific, reasonable, and adequate compensation, realizing the socialization of marine environmental infringement relief (Han, 2012). This proposal not only meets the challenges raised by various pollution risks from ships in China, but is also realistic, as there are at least two development directions of the CSOPC Fund to a more unified compensation fund for ship pollution damage in the foreseeable future:

Extending the Application of the Chinese Ship-Induced Oil Pollution Compensation Fund to Inland River Ship Pollution Accidents

At present, the CSOPC Fund applies to the internal waters, territorial sea, contiguous zone, exclusive economic zone, continental shelf, and other sea areas under the jurisdiction of the PRC. Internal waters only refer to sea areas on the inland side of China’s territorial sea baseline, including coastal port waters, but excluding inland rivers (CSOPC Fund, 2021b). Therefore, victims of inland river pollution accidents cannot claim compensation from the CSOPC Fund, unless it is proven that the clean-up work at inland waters is to prevent or reduce pollution of the sea area. In the “Shanhong 12” oil pollution accident, pollution had not only happened in the sea but also in the Changshu section of the Yangtze River and the inland river of Chongming Island. Owing to the limitation of the applicable geographical scope of the CSOPC Fund, the losses in the sea area were compensated by the fund, while the losses in the inland rivers were not. This has triggered the concern for equity and environmental protection effect of the inland waters, as with the continuous improvement of the navigability of China’s domestic rivers, the possibility of major oil pollution accidents from ships in inland waters is also increasing. For example, in May 2018, the second phase of the 12.5-meter deep-water channel below the Yangtze River in Nanjing was officially commissioned (CNR, 2018), the 50,000-ton ships can now reach Nanjing Port directly and the 100,000-ton ships can arrive with reduced load.

The possibilities of enabling the CSOPC Fund to cover the ship pollution accidents in inland rivers can be expected since the first-tier compulsory liability insurance for shipowners regarding inland river pollution accidents has been set in motion. The Ministry of Transport initiated the revision of the Measures for the Implementation of Civil Liability Insurance for Ship-induced Oil Pollution Damage and published its Draft for Comment in August 2020. One of the core changes is to extend the application of compulsory insurance from ships navigating within the sea areas to inland waterways (Ministry of Transport of PRC, 2020). Also, Article 51 of the Yangtze River Protection Law, which came into force on March 7, 2021, stipulates that “the state shall establish a mechanism that combines pollution liability insurance and financial guarantees for ships transporting dangerous goods in the Yangtze River Basin.” To implement the Yangtze River Protection Law, the Ministry of Transport published the Measures for the Implementation of Civil Liability Insurance for Ship-induced Inland River Pollution Damage (Draft for Comment) online in August 2021 (Ministry of Transport of PRC, 2021). According to the draft, all ships transporting dangerous goods through the Yangtze River Basin and ships transporting dangerous chemicals through the inland waters of China must purchase corresponding compulsory insurance. With the first-tier compulsory liability insurance mechanism for shipowners ready, one of the main obstacles to the application of the second-tier fund mechanism is eliminated.

Extending the Application of the Chinese Ship-Induced Oil Pollution Compensation Fund to Pollution Accidents of Hazardous and Noxious Substances

Although the International Maritime Convention on Liability and Compensation for Noxious and Hazardous Material Damage [hereafter, Hazardous and Noxious Substances (HNS) Convention], which includes a second-tier fund mechanism, has been negotiated to establish the legal regime of compensation for pollution damage caused by HNS, it has not yet come into effect. As a major importer of HNS, China has no comprehensive legal framework covering liability and compensation for damage in connection with the carriage of HNS by sea (Dong and Zhu, 2019, 220). Considering the potential pollution risks of HNS transported by sea, it is long advised that China should construct a compensation system for HNS pollution damage in the domestic law first by referring to the provisions of the HNS Convention (Li, 2015, 126). This is reflected in the Revised Draft of Chinese Maritime Code published by the Ministry of Transport for online comments in November 2018 (Ministry of Transport of PRC, 2018), where a new chapter titled “Liability for Ship Pollution Damages” was added. Notably, the fifth section of this new chapter is “Ship Oil Pollution Damage Compensation Fund” and the pollution accidents covered by the fund include pollution damage from HNS. Although there is uncertainty regarding whether to incorporate regulations regarding HNS (as the HNS Convention has not come into force and there is difficulty in implementing the first-tier compulsory insurance), the attempt itself gives a strong clue for the future of the CSOPC Fund. Meanwhile, it is practically feasible for the CSOPC Fund to be expanded into a unified ship pollution fund by setting up an independent HNS account in the current fund, or simply sharing a common fund account. To this end, the Marine Environment Protection Law shall also be amended, where the requirement of “establish the system for ship-induced oil pollution insurance and damage compensation fund” in Article 66 shall be modified to “establish the system for ship-induced pollution insurance and damage compensation fund.”

Victim Compensation of the Chinese Ship-Induced Oil Pollution Compensation Fund

Providing adequate compensation to victims in oil pollution accidents is the fundamental function of the compensation fund. However, assessing the CSOPC Fund in terms of compensation availability, it is not only inadequate in the compensation ability, but also deficient in its claim settlement mechanism.

Inadequate Compensation

The current inadequacy of the CSOPC Fund is not only manifest in terms of the maximum amount of compensation payable, but also in terms of the compensation scope and availability of losses and expenses in a low compensation sequence.

Certain Types of Losses Are Not Compensated

The compensated types of loss under the CSOPC Fund are less due to claims for future expenses to be incurred for restoration measures, and indirect loss and pure economic loss (which are allowed in the IOPC Fund) are excluded.

According to Article 17 of Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues Concerning the Trial of Cases of Disputes over Compensation for Ship-induced Oil Pollution Damage (hereinafter, Oil Pollution Judicial Interpretation), expenses on reasonable measures which are to be taken to restore the environment in the future are allowed for compensation for environmental damage. However, Article 17 of the Fund Administrative Measures only lists the expenses incurred for measures taken to recover marine ecology and natural fishery resources as one of the claims allowed for compensation under the CSOPC Fund, and Article 21 of the Fund Administrative Measures further states that only expenses or losses that have been incurred can be recovered from the Fund. In comparison, the costs of reasonable measures of reinstatement to be undertaken are allowed for the IOPC Fund (2018).

Meanwhile, according to Articles 12 and 13 of the Oil Pollution Judicial Interpretation, indirect losses of the oil pollution victims and the pure economic losses that have a direct relationship with the oil pollution are also allowed for compensation. However, Article 17 of the Fund Administrative Measures only lists direct economic losses caused to the fishery and tourist industries as one of the claims allowed for compensation under the CSOPC Fund. As a result, in the “Trans Summer” oil pollution accident, claims for fishing loss brought up by hundreds of fishermen were dismissed (CSOPC Fund, 2020). This is different from the practice of the IOPC Fund, as consequential loss and pure economic loss are all payable (IOPC Fund, 2018). Also, interest of relevant losses covered by the fund is not payable under the CSOPC Fund as shown by the compensation report of “Shanhong 12” oil pollution accident (CSOPC Fund, 2017), while the IOPC Fund takes a more flexible position: if interest is payable under national law, the Fund would be obliged to follow the applicable national law, but the rate and period of interest can be agreed between claimants and the Fund during negotiations (De la Rue and Anderson, 2009, 436–437).

Inadequacy for Loss and Expense in Lower Compensation Sequence

Although prioritizing the emergency response costs in the compensation sequence is a rational policy, it greatly dilutes the possibilities of compensation for other pollution damages, making it difficult for other types of oil pollution claims to get adequate compensation from the CSOPC Fund with a currently limited compensation amount. Consequently, among the 17 claim decisions of the CSOPC Fund listed in Table 1, only four cases relate to non-emergency disposal costs while 15 cases deal with or involve emergency response costs.

Improved but Still Defective Claim Settlement Mechanism

Despite the compensation amount and scope, the claim settlement mechanism is another important aspect of the compensation availability of the fund.

The CSOPC Fund has made considerable progress during its practice, not only in terms of the enhancement of its governance mechanism but also in terms of the improvement of the claim settlement mechanism. For example, in June 2015, the CSOPC Fund Management Committee, the highest authority for the use and management of the CSOPC Fund, was formally established in Beijing, and in the same year, the Claims Settlement Center of the CSOPC Fund was established to provide settlement services. In the Guidelines for Compensation Settlement updated in 2020, in addition to the update of the relevant rate table, it also added the claimant’s right to object to the fund’s inadmissibility decision with review procedure.

However, due to the government-managed nature of the CSOPC Fund as categorized by Article 18 of Fund Administrative Measures, the operation of the CSOPC Fund needs to meet the special requirements for government funds as embodied in the Interim Measures for the Administration of Government-managed Funds. The administrative features of the CSOPC Fund have caused problems or ambiguities that will not occur under the IOPC Fund, such as: (1) Whether the CSOPC Fund is an independent legal person or not? If it is, which kind of legal person does it belong to? (2) Is the CSOPC Fund’s decision on settlement of claims a civil or an administrative one? and (3) If the claimants are dissatisfied with the decision of the CSOPC Fund, should they initiate a civil or administrative lawsuit (Han and Zhu, 2018)?

Simultaneously, the strict management rules for government-managed funds may also cause inconvenience for the CSOPC Fund. For example, the government budgeting and expenditure requirements are tricky to handle, which could lead to the low efficiency of the CSOPC Fund’s compensation procedure (Shuai, 2019, 94). Article 13 of the Detailed Rules for the Implementation of the Administrative Measures for the Collection and Use of the CSOPC Fund regulates that the compensation shall be made following the expenditure budget, and where the fund expenditure budget for the current year is insufficient for the claim cases, the Secretariat of the Management Committee of the CSOPC Fund shall make compensation according to the sequence of time when the Management Committee makes the compensation decision, and compensate proportionally for those in the same compensation sequence. For the unpaid part that exceed the fund expenditure budget for the current year, it shall be included in the fund expenditure budget for the following year. The above procedure will inevitably complicate and delay the compensation procedure, and problems caused thereof would become more obvious as the CSOPC Fund’s practice broadens. This shall be addressed by the amendment of the Fund Administrative Measures, where special rules shall be adopted to exempt the application of those unsuitable procedure requirements for government funds to the CSOPC Fund, for the purpose of speedy remedy for victims in the pollution accidents.

Meanwhile, the cooperation with other participants involved in the oil pollution compensation regime shall also be strengthened. The handling of major oil pollution accidents requires multi-party cooperation including government departments, P&I clubs, shipowners, oil pollution clean-up enterprises, oil pollution compensation funds, and so on. Especially for the P&I clubs and the oil pollution compensation fund, the possibility and necessity of cooperation are significant owing to the cohesion of the liability for compensation. As shown by the practice of the IOPC Fund, the P&I clubs and IOPC Fund often jointly investigate and assess the damage from a particular incident and cooperate in the settlement of claims to ensure a consistent and efficient approach (Briggs, 2005, 7). Such cooperation is not yet well established for the CSOPC Fund because most of the oil pollution cases handled are caused by unidentified ships, and the difference in the compensation scope and items between the insurance of the shipowner and the CSOPC Fund as mentioned above also acts as a hindrance.

Potential Enhancement of the Compensation Availability

Similar to the United States, establishing the domestic fund means China is making a calculated choice to self-insure against major oil pollution damage arising in their waters (Tan, 2006). Therefore, it is deprived of the chance to better diversify the risk of major oil pollution incidents and has to go through the financial uncompetitive period at its initial development stage. The CSOPC Fund has taken a “broad but shallow” approach in its early development stage: the scope and circumstances of oil pollution accidents compensated by the CSOPC Fund are broader, providing more compensation chances to pollution victims, but a relatively low compensation limit is set for a single accident and certain losses are restricted.

As the world’s largest oil importing country, the current inadequacy in the compensation and defective claim settlement mechanism of the CSOPC Fund is not acceptable in the long term. However, the magnitude of domestic fund contribution will enable China’s unilateral fund regime to survive without links with the international market. In 2020, China imported 542.4 million tons of crude oil (Reuters, 2021), while the IOPC Fund’s contributions in 2019 totaled 1.504 billion tons (IOPC Funds, 2021). The current low compensation limit and high levy rate are mainly attributable to the fact that the CSOPC Fund is in its primitive accumulation phase of the capital pool, and with the continuous expansion of its accumulated capital scale, it may gradually increase the limit, reduce the levy rate, or even suspend the levy as compensation can be paid with the interests of the accumulated capital pool and other revenues such as fines and so on.

The Ministries of Transport and Finance are also accelerating the revision of the Fund Administrative Measures to tackle the problems cited in theories and practices. A consensus has been reached to solve the most critical problem, which is to increase the number of limitations. In a draft, not yet made public, it is expected to adjust the limit to ¥200 million for a single oil pollution accident and if the accident is graded as an extraordinarily serious pollution accident, the limit could be raised to ¥1 billion. Admittedly, this proposed limitation amount is still lower than that of the IOPC Fund, but the compensation ability of the CSOPC Fund as well as the willingness and ability of oil receivers to contribute to the fund have to be considered, as an increase in the financial caps would lead to a decrease in the size of the coalition as observed with the 2003 Fund with the effect to bound pollution deterrence to an inefficient level (Hay, 2010, 42). The enhancement of the protection capability of the CSOPC Fund may also be achieved by other means. For example, the purchase of commercial insurance by the Fund may be considered to enhance its indemnification capability for major accidents. This idea was proposed and discussed in a conference held by Dalian Maritime University in 2020, where the possibility of expanding the CSOPC Fund’s compensating ability through the integration of the insurance mechanism was discussed and supported.

Meanwhile, methods to coordinate the contradiction between the policy considerations in giving priority to emergency response costs and providing funds for other damages have been widely discussed. While enhancing the limit of compensation can certainly alleviate this contradiction, the practice of the OSLTF in setting up a special fund for emergency response costs can be further adopted by the CSOPC Fund. The emergency fund set by the OSLTF provides funds for (1) federal and state agency removal costs, including those of the Coast Guard and the Environmental Protection Agency and (2) initiation of natural resource damages assessments by natural resource trustees. As argued by scholars, by setting up a special sub-fund for emergency response purposes, not only can the cost of emergency response be paid separately and sufficiently, or even in advance, guaranteeing the fast operation of the oil pollution emergency response system, but improvements in the possibilities of other damages being compensated can also be made, reducing the unfairness caused by prioritization of emergency response costs (Li and Hu, 2018, 39).

Conclusion

From the traditional dimension of the victim compensation function of compensation fund for ship-induced pollution damage, abandoning the domestic CSOPC Fund and joining the IOPC Fund maybe a choice for China, as it is obvious that the CSOPC Fund is unlikely to provide sufficient compensation and serve as a second tier of protection for victims at the present stage. There shall also be no fundamental obstacles for such choice, as China is already a member of the 1992 CLC, which means China’s legal regime of oil pollution compensation is in accord with the IOPC Fund in general. However, the function of the compensation fund for ship-induced pollution damage in pollution governance shall also be emphasized. This is the key why domestic approach is still the more favorable choice for China in a long-term strategic way: first, the domestic fund offers the advantages in the freedom to establish the compensation fund in accords with specific domestic needs. Especially considering the government fund nature of the CSOPC Fund, the government departments can exercise more control over the fund, and the practical needs of government in oil pollution governance can be satisfied better. Second, the domestic fund provides possibilities of establishing a more unified compensation fund for ship-induced pollution damage, contributing to a more systematic ship-induced pollution governance regime. Third, the current inadequacy and defects of the CSOPC Fund in victim compensation can be improved gradually, while the IOPC Fund is unlikely to provide the same contribution as the domestic fund in pollution governance. Last, to avoid the excessive burden on oil companies and increase the scale of the CSOPC Fund’s capital reserves and compensation capabilities as soon as possible, China is unlikely to accede to the 1992 Fund Convention and retain the domestic CSOPC Fund at the same time as Canada.

While continuing the strategic choice of adopting a domestic approach on the ship-induced oil pollution damage compensation fund, improvements are necessary for the CSOPC Fund both in terms of achieving a better pollution governance effect and providing adequate compensation and a professional claim handling service. For the purpose of a better service of its pollution governance function, besides the effort to coordinate the tension between the emergency response costs and other damages, the key step is to arrange for the unified ship-induced pollution damage compensation fund through an amendment of relevant laws. To better realize its compensation function, the CSOPC Fund should give up its current “broad but shallow” approach, and amendments shall be made to the Fund Administrative Measures as soon as possible to lift the compensation limit, make the compensation for emergency response costs independent from other losses and expenses, and coordinate the compensation scope of the fund with the compensation liability of the shipowner and its insurer. Meanwhile, it is necessary to clarify the legal nature of its claim settlement activities, reduce the administrative feature of the fund operation for improvement of the efficiency of claim settlement, and strengthen the cooperation with P&I clubs in compensation handling by borrowing the mature experiences of the IOPC Fund and other domestic funds.

Author Contributions

XC: original idea and writing up. Y-CC: proofreading and supervision. Both authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Social Science Fundamental Project, China, “Research on China’s Maritime Rights Protection under the Perspective of Maritime Community with the Shared Future” (Grant No. 19VHQ009), Youth Project of Philosophy and Social Science of Liaoning Province (No. 20221lslwtkt-010), and Fundamental Research Fund of Dalian Maritime University (3132021504).

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

Briggs, R. (2005). “The international oil pollution compensation funds,” in Oil Pollution and its Environmental Impact in the Arabian Gulf Region, eds M. Al-Azab, W. El-Shorbagy, and S. Al-Ghais (Amsterdam: Elsevier). doi: 10.1016/S1571-9197(05)80025-4

CNR (2018). The second phase of the 12.5-meter deep water channel below the Yangtze River in Nanjing has been fully completed today. Available Online at: http://china.cnr.cn/NewsFeeds/20180508/t20180508_524226263.shtml (accessed November 10, 2021).

CSOPC Fund (2017). Compensation report of the “Shanhong 12” oil pollution accident. Available Online at: https://www.sh.msa.gov.cn/copcfund/lpal/2688.jhtml (accessed November 10, 2021).

CSOPC Fund (2020). Compensation report of the Trans Summer oil pollution accident. Available Online at: https://www.sh.msa.gov.cn/copcfund/lpal/2731.jhtml (accessed November 10, 2021).

CSOPC Fund (2021a). Accidents Tracking. Available Online at: https://www.sh.msa.gov.cn/copcfund/lpal/index.jhtml (accessed November 10, 2021).

CSOPC Fund (2021b). Chapter one, Section 1 of the Compensation Guidelines. Available Online at: https://www.sh.msa.gov.cn/copcfund/dbfile.svl?n=/u/cms/www/202009/17145556o009.pdf (accessed November 10, 2021).

De la Rue, C., and Anderson, C. B. (2009). Shipping and the Environment, 2nd Edn. New York: Informa Law.

Donaldson, M. P. (1992). The oil pollution act 1990: reaction and response. Villanova Environ. Law J. 3, 283–303.

Dong, B., and Zhu, L. (2019). Civil Liability and Compensation for Damage in Connection with the Carriage of Hazardous and Noxious Substances Chinese Perspective. Ocean Dev. Int. Law 50, 209–224. doi: 10.1080/00908320.2019.1582609

Dong, B., Zhu, L., Li, K., and Luo, M. (2015). Acceptance of the international compensation regime for tanker oil pollution – And its implications for China. Mar. Policy 61, 179–186. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2015.08.001

Faure, M., and Wang, H. (2019). “Smart Mixes of Civil Liability Regimes for Marine Oil Pollution,” in Smart Mixes for Transboundary Environmental Harm, eds J. Van Erp, M. Faure, A. Nollkaemper, and N. Philipsen (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press), 285–308. doi: 10.1017/9781108653183.013

Han, L. (2012). Establishment and Legal Framework of China’s Marine Pollution Damage Compensation Fund. J. Soc. Sci. 5, 80–86.

Han, L., and Zhu, Z. (2018). Issues need to be clarified for China’s Ship-induced Oil Pollution Compensation Fund. Politics Law Rev. 2, 281–290.

Hao, H. (2019). Prospect of China’s Accession to the 1992 International Convention on the Establishment of an International Fund for Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage. Chin. Oceans Law Rev. 15, 113–136.

Hay, J. (2010). How efficient can international compensation regimes be in pollution prevention? A discussion of the case of marine oil spills. Int. Environ. Agreem. Politics Law Econ. 10, 29–44. doi: 10.1007/s10784-009-9096-8

Hu, Z. (2005). Legal Issues Concerning the Establishment of a Ship-source Oil Pollution Compensation Fund. SMU Law Rev. 1, 163–184.

Hubei Higher People’s Court (2018). The “Zhongheng 9” Case. Case Citation: (2018) Hubei Final No.664. Wuhan: Hubei Higher People’s Court.

IOPC (2021). Contributions to the IOPC Funds. Available Online at: https://iopcfunds.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/Contributions-to-the-IOPC-Funds_e.pdf (accessed November 10, 2021).

IOPC Fund (2018). IOPC Fund, Claims Manual (2019 Edition), Section 3.6. Available Online at: https://iopcfunds.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/12/2019-Claims-Manual_e-1.pdf (accessed November 10, 2021).

IOPC Funds (2021). Annual Report 2020 of IOPC Funds. Available Online at: https://iopcfunds.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/Annual-Report-2020_e.pdf (accessed November 10, 2021).

Jacobsson, M. (1994). Compensation for Oil Pollution Damage Caused by Oil Spills from Ships and the International Oil Pollution Compensation Fund. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 29, 378–384. doi: 10.1016/0025-326x(94)90657-2

Kiern, L. (1994). The Oil Pollution Act of 1990 and the National Pollution Funds Center. J. Marit. Law Commer. 25:487520.

Kiern, L. (2000). Liability, Compensation, and Financial Responsibility under the Oil Pollution Act of 1990: a Review of the First Decade. Tulane Marit. Law J. 24, 481–545.

Kim, I. (2003). A comparison between the international and US regimes regulating oil pollution compensation. Mar. Policy 27, 265–279.

Li, W., and Hu, Z. (2018). Deficiencies in the Chinese Ship-sourced Oil Pollution Compensation Fund regime and the improvement thereof. Chin. J. Marit. Law 3, 33–40.

Li, Z. (2015). On Legal Regime of Compensation for HNS Pollution Damage from Ships. Ph.D. thesis. China: Dalian Maritime University.

Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Finance of PRC (2020). Announcement of the Ministry of Transport and the Ministry of Finance on The Reduction or Exemption of Port Construction Fees and compensation fund for ship-induced oil pollution damage. Available Online at: http://www.gov.cn/zhengce/zhengceku/2020-03/13/content_5491052.htm (accessed November 10, 2021).

Ministry of Transport of PRC (2018). Notice of the Ministry of Transport on the Public Consultation on the ‘Chinese Maritime Code (Draft for Comment). Available Online at: https://xxgk.mot.gov.cn/2020/jigou/fgs/202006/t20200623_3308111.html (accessed November 10, 2021).

Ministry of Transport of PRC (2020). Notice of the Ministry of Transport on the Measures of the People’s Republic of China for the Implementation of Civil Liability Insurance for Vessel-induced Oil Pollution Damage (Draft for Comment). Available Online at: http://www.gov.cn/hudong/2020-08/18/content_5535473.htm (accessed November 10, 2021).

Ministry of Transport of PRC (2021). Notice of the Ministry of Transport on the Implementation Measures for Civil Liability Insurance for Inland River Pollution Damage from Ships (Draft for Comment). Available Online at: http://www.moj.gov.cn/pub/sfbgw/lfyjzj/lflfyjzj/202108/t20210824_435852.html (accessed November 10, 2021).

Reuters (2021). China’s 2020 crude oil imports hit record on stockpiling. Available Online at: https://www.reuters.com/article/china-economy-trade-crude-idUSL1N2JP07X (accessed November 10, 2021).

Shaw, R. (2013). “Pollution of Sea by Hazardous and Noxious Substances – Is a Workable International Convention on Compensation an Impossible Dream?,” in Maritime Law Evolving, Hart Publishing, ed. M. Clarke (New York: Bloomsbury Publishing).

Shuai, Y. (2019). References and thoughts on the mechanism of International Oil Pollution Compensation Funds. Chin. J. Marit. Law 1, 89–97.

Tan, A. K.-J. (2006). “Vessel-source marine pollution: the law and politics of international regulation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9780511494628

Troop, P. M., and Greenham, M. S. (1991). Ship-source oil pollution fund: 20 years of Canada’s experience. Washington D.C: American Petroleum Institute. doi: 10.7901/2169-3358-1991-1-683

Wagner, T. J. (1990). The oil pollution act of 1990: an analysis. J. Marit. Law Commer. 21, 569–588.

Woods, J. M. (2009). Going on twenty years the oil pollution act of 1990 and claims against the oil spill liability trust fund. Tulane Law Rev. 83, 1323–1338.

Keywords: CSOPC Fund, IOPC Fund, oil pollution, domestic approach, pollution governance, adequate compensation, emergency response

Citation: Cao X and Chang Y-C (2022) A Two-Dimensional Assessment of China’s Approach Concerning the Compensation Fund for Ship-Induced Oil Pollution Damage: Pollution Governance and Victim Compensation. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:817049. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.817049

Received: 17 November 2021; Accepted: 07 January 2022;

Published: 28 January 2022.

Edited by:

Kum Fai Yuen, Nanyang Technological University, SingaporeReviewed by:

Liang Zhao, University of Southampton, United KingdomBaris Soyer, Swansea University, United Kingdom

Copyright © 2022 Cao and Chang. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Yen-Chiang Chang, eWNjaGFuZ0BkbG11LmVkdS5jbg==

Xingguo Cao

Xingguo Cao Yen-Chiang Chang

Yen-Chiang Chang