94% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

REVIEW article

Front. Mar. Sci., 30 June 2022

Sec. Deep-Sea Environments and Ecology

Volume 9 - 2022 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2022.799191

This article is part of the Research TopicRecent and Emerging Innovations in Deep-Sea Taxonomy to Enhance Biodiversity Assessment and ConservationView all 15 articles

As one of the oldest branches of biology, taxonomy deals with the identification, classification and naming of living organisms, using a variety of tools to explore traits at the morphological and molecular level. In the deep sea, particular challenges are posed to the taxonomic differentiation of species. Relatively limited sampling effort coupled with apparent high diversity, compared to many other marine environments, means that many species sampled are undescribed, and few specimens are available for each putative species. The resulting scarce knowledge of intraspecific variation makes it difficult to recognize species boundaries and thus to assess the actual diversity and distribution of species. In this review article, we highlight some of these challenges in deep-sea taxonomy using the example of peracarid crustaceans. Specifically, we offer a detailed overview of traditional as well as modern methods that are used in the taxonomic analysis of deep-sea Peracarida. Furthermore, methods are presented that have not yet been used in peracarid taxonomy, but have potential for the analysis of internal and external structures in the future. The focus of this compilation is on morphological methods for the identification, delimitation and description of species, with references to molecular analysis included where relevant, as these methods are an indispensable part of an integrative taxonomic approach. The taxonomic impediment, i.e. the shortage of taxonomists in view of a high undescribed biodiversity, is discussed in the context of the existing large taxonomic knowledge gaps in connection with the increasing threat to deep-sea ecosystems. Whilst peracarid crustaceans are used here as an exemplary taxon, the methodology described has broad relevance to many other deep-sea taxa, and thus will support broader research into deep-sea biodiversity and ecology more widely.

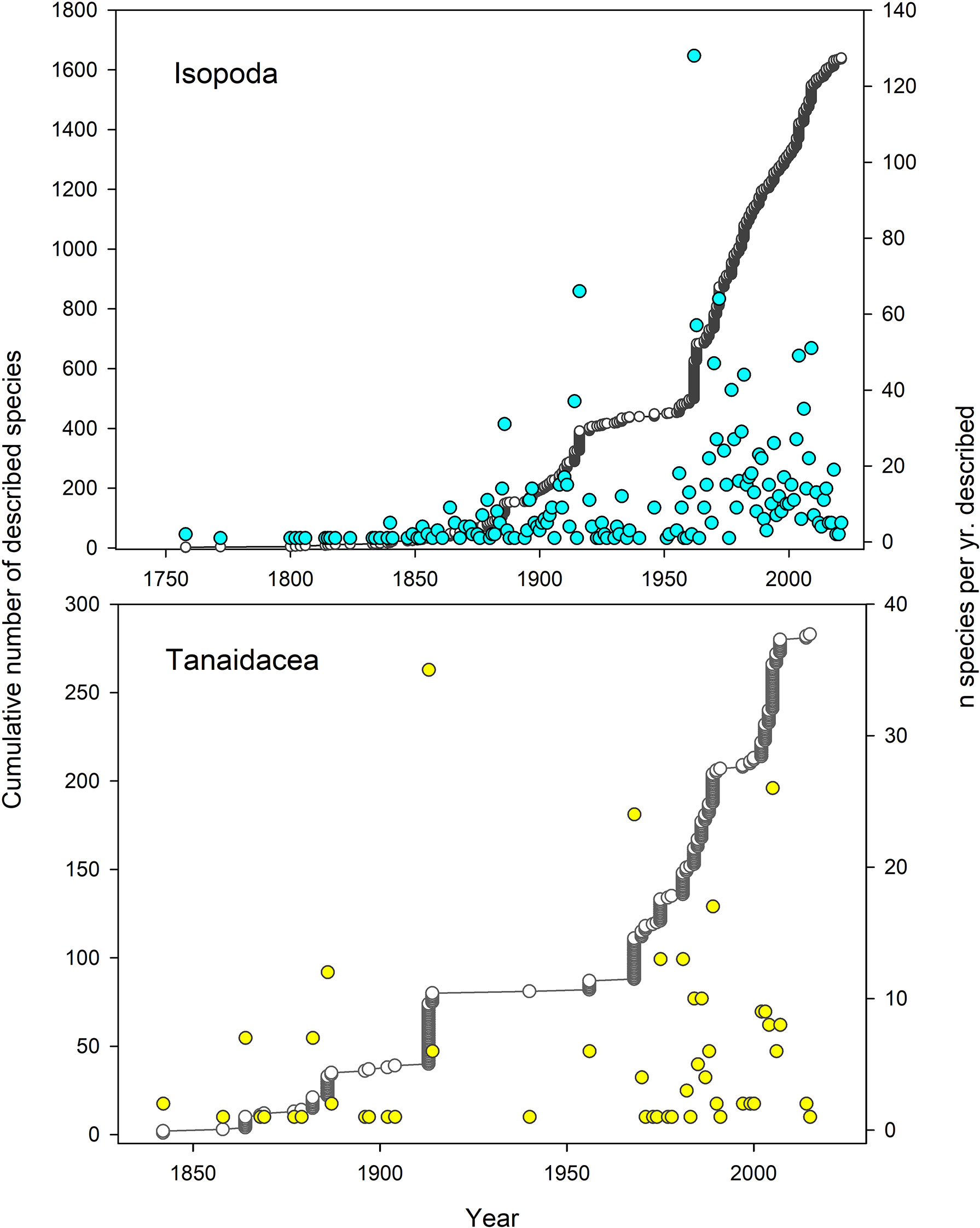

The dichotomy in deep-sea biodiversity research consisting of a gap between the sheer scale of the deep sea and our incomplete knowledge of what actually lives there, is immense; areas away from the shelf edge making up the deep sea cover more than two-thirds of the Earth’s global surface, but only a tiny portion of this has been examined by scientists (Ramirez-Llodra et al., 2010; Costello and Chaudhary, 2017). It is in part because of this limited knowledge that estimates of how many metazoan species to expect in the deep sea vary widely, ranging between 0.5 to more than 10 Mio. species (May, 1992; Grassle and Maciolek, 1992; Poore and Wilson, 1993; Lambshead and Boucher, 2003; Appeltans et al., 2012). There are currently > 26,000 named species catalogued in the World Register of Deep-Sea Species (WoRDSS; Glover et al., 2021), but certainly many more are to be discovered, especially among the inconspicuous, small-size and short-ranged fractions (Mora et al., 2011).

The discovery and description of the first species from the deep sea, the sea pen Umbellula encrinus (Linnaeus, 1758), heralded the beginning of the taxonomic study of deep-sea organisms. Remarkably, this coincided with the revision of the previous classification system and the birth of modern taxonomy as introduced by Linnaeus (1735) Systema Naturae. Our knowledge of deep-sea species has been thereby closely linked, on the one hand, with the ever-improving technology and logistics for taking samples from the deep sea and, on the other hand, with methodological advances to make external and internal parts of organisms visible. Here, the invention of the first compound microscopes towards the end of the 16th century had pushed taxonomic work forward considerably since it allowed to study the smaller size fractions and thus greatly increased the number of known species (Rosenthal, 2009; Manktelow, 2010). Regarded today as art, the detailed scientific illustrations of taxonomists at the earliest time such as Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), Alexander von Humboldt (1769–1859), Ernst Haeckel (1834–1919), or Georg Ossian Sars (1837–1927) were indispensable in the absence of the photographic imaging techniques available today (Figures 1A–G). Isolated deep-sea samples had already been collected prior, but it was only 150 years ago that a global collection as part of the HMS Challenger Expedition (1872–1876) could refute the thesis that the deep sea is devoid of life (Murray and Renard, 1891). Research into deep-sea biodiversity has gradually shifted from a more exploratory focus that involved a mere inventory of species to a more systematic approach that addresses issues such as how deep-sea diversity is structured. Likewise, taxonomy, as a legacy of Charles Darwin (1809–1882), Ernst Haeckel and more recently the German systematist Willi Hennig (1913–1976), has made a transition from classifying taxa based on their morphological appearance (phenetics) to using homologous characters to illuminate phylogenetic relationships (cladistics).

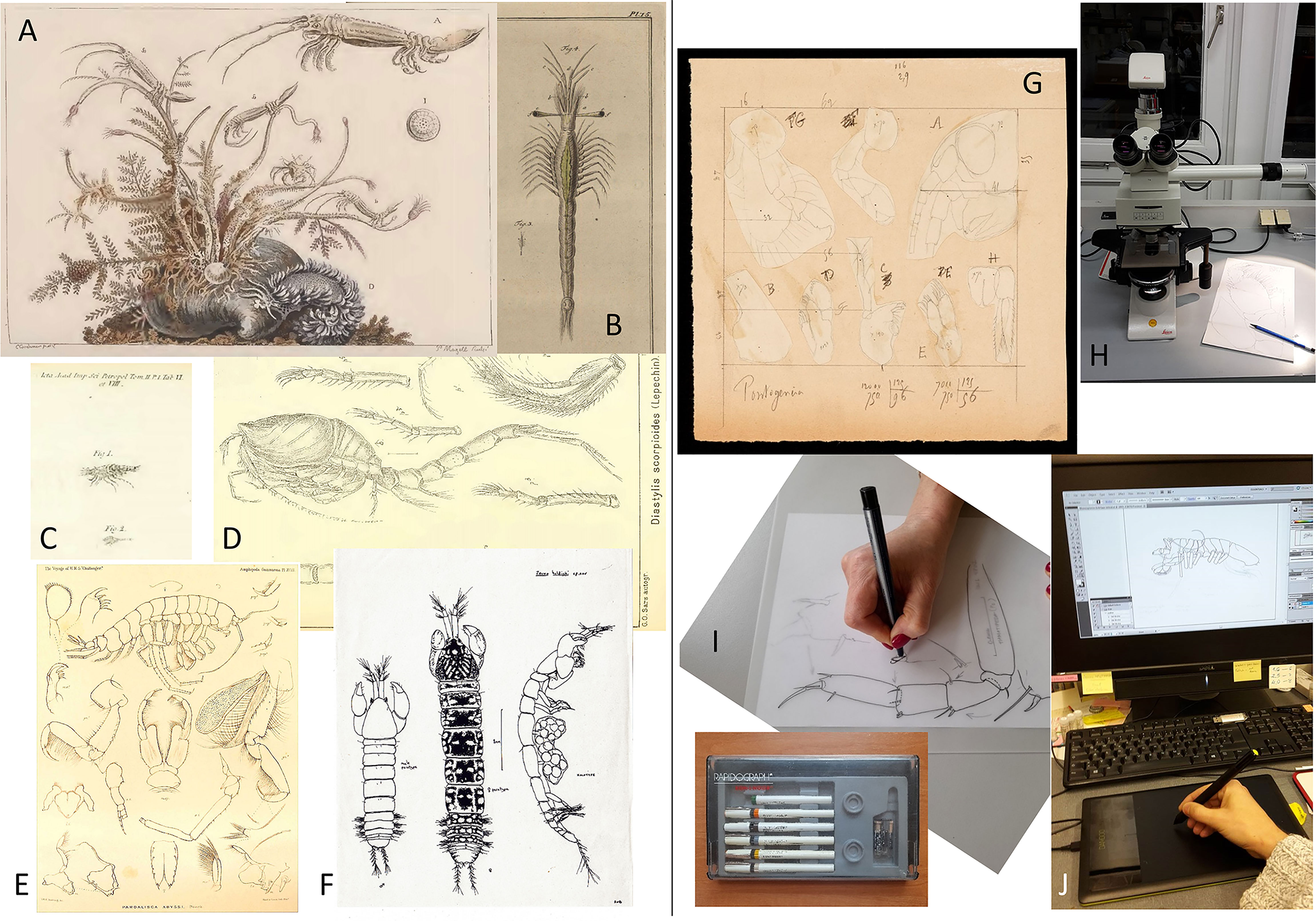

Figure 1 Scientific illustrations of peracarids as complement of taxa description from past to present. (A) Isopod genus Astacilla Cordiner, 1793 illustrated by Cordiner (1793). (B) Mesopodopsis slabberi (van Beneden, 1861), the earliest illustrated mysid by Slabber (1778). (C) Diastylis scorpioides (Lepechin, 1780), the earliest published illustration of a cumacean as Oniscus scorpioides Lepechin, 1780 (see Holthuis, 1964). (D) Diastylis scorpioides (Lepechin, 1780), illustrated by G.O. Sars more than one century later (G.O. Sars, 1900). (E) The amphipod Pardalisca abyssi Boeck, 1871 illustrated after the voyage of H.M.S. Challenger during the years 1873–76 (Stebbing, 1888). (F) Original hand inked drawing made by Roger Bamber for the description of the tanaid Zeuxo holdichi Bamber, 1990. (G) Original plate outline with the drawings made by Édouard Chevreux for the amphipod description Pontogeneia minuta Chevreux, 1908 (Crustacean collection MNHN). (H) Compound microscope equipped with camera lucida to draw specimens for taxonomical purposes (photo I Frutos). (I) Preparing a plate by hand inking from previously made pencil drawings (photo I Frutos). (J) Electronical inking of drawings using a drawing tablet and computer (photo I Frutos).

To date, referring to morphological features is still the means of choice when delimiting, identifying and describing deep-sea species. This is likely because it seems easy to apply, and others, such as the biological species concept sensu Mayr (1942; “Species are groups of interbred natural populations reproductively isolated from other such groups”) cannot readily be applied due to the difficulty to obtain data on reproduction of deep-sea species (see also Brandt et al., 2012). With the advent of molecular approaches in taxonomy in general and deep-sea taxonomy in particular, however, many complications are associated with the phenotypic data, including evidence of sexually dimorphic or polymorphic species, convergence, and phenotypic plasticity (Raupach and Wägele, 2006; Vrijenhoek, 2009; Błażewicz-Paszkowycz et al., 2012; Brandt et al., 2012; Riehl et al., 2012; Błażewicz-Paszkowycz et al., 2014; Brandt et al., 2014; Mohrbeck et al., 2021). While molecular techniques have certainly helped expedite species identification and delimitation, phylogenetic relationships and biodiversity assessment, also on the background of intensifying anthropogenic impacts on deep-sea ecosystems, the description and naming of species remains pivotal to understanding their ecological function and evolution. Traditional taxonomy, however, in general cannot keep up with automated, high-throughput molecular methods that generate large amounts of data at a rapid pace, resulting in a large number of unnamed species on taxonomists’ shelves, which remain unavailable for conservation purposes (Pante et al., 2015; Gellert et al., 2022). Moreover, for many (and not only) biologists, species identification also reduced to the pragmatic ability to distinguish between species remains far from a satisfactory solution. The simple curiosity to know and understand biodiversity in every detail at different levels of life organization, as well as the search for answers to how and why, goes beyond rapid and precise species identification (Will et al., 2005; Wheeler, 2018; Dupérré, 2020).

In that regard, morphological techniques used in deep-sea taxonomy did not stand still, but are constantly being further developed or have been introduced as new applications. For example, Confocal Laser Scanning Microscopy (CLSM) was originally developed in the 1950s to map the anatomy of the human nervous system and is now increasingly being used for the taxonomic analysis of microscopic invertebrates in the deep sea (Michels and Büntzow, 2010; Brandt et al., 2014; Meißner et al., 2017; Martínez Arbizu and Petrunina, 2018; Jennings et al., 2018; Kaiser et al., 2018; Błażewicz et al., 2019; Chim and Tong, 2020; Kaiser et al., 2021; Demidov et al., 2021). 3-D visualizations of internal structures are reconstructed from histological sections (Neusser et al., 2016; Bober et al., 2018; Gooday et al., 2018). Underwater Hyperspectral Imagery has been employed to aid identification of deep-sea megafaunal species owing to their specific spectral profiles alongside automated tools for the annotation of benthic fauna from video or still imagery (Langenkämper et al., 2017; Dumke et al., 2018; Kakui and Fujiwara, 2020; Singh and Mumbarekar, 2021).

The remit of this review article is to compile and evaluate available traditional and modern tools and techniques in morphology-based taxonomy with a focus on peracarid crustaceans. With more than 21,000 described species, the malacostracan superorder Peracarida is a highly diverse group containing about a third of the total richness of crustaceans (Appeltans et al., 2012; Wilson and Ahyong, 2015). Common to all peracarids is brood care, whereby embryos are carried around in a ventral brood pouch formed by coxal oostegites until juveniles are released. Peracarids occur in all aquatic habitats, including caves, freshwater, stygobiont and marine environments, but only the oniscidean isopods contain truly terrestrial species. Besides extant species, they have occurrences in the fossil record, including deep-sea areas (Secrétan and Riou, 1986; Selden et al., 2016; San Vicente and Cartanyà, 2017; Luque and Gerken, 2019). Spanning different size classes, from meio- to megafauna, the highest diversity of peracarids is likely to be found within the macrofauna, where they represent one of the most diverse groups in the deep sea (Hessler and Jumars, 1974; Sanders et al., 1985; Frutos et al., 2017a; Brandt et al., 2019; Washburn et al., 2021). Peracarids are the main component of suprabenthos, which includes all swimming bottom-dependent animals performing, with varying amplitude, intensity, and regularity, seasonal or daily vertical migrations above the seafloor (Brunel et al., 1978; Frutos et al., 2017a; Ashford et al., 2018). Most species of deep-sea peracarids are benthic, with tanaidaceans and some isopod taxa living mostly infaunally, whilst many amphipods, isopods and cumaceans are known as good swimmers (Błażewicz-Paszkowycz et al., 2012; Poore and Bruce, 2012). Shrimp-like mysids and lophogastrids similarly have good swimming capacities, representing members of suprabenthic (mysids) and pelagic (lophogastrids) communities (San Vicente et al., 2014a). Although the variety of lifestyles, morphologies and functions of deep-sea peracarids is large, with some exceptions, a general suite of taxonomic working methods can be applied to their study (including the study of some fossil specimens).

This review is intended to describe the entire process required for the morphological examination of deep-sea peracarids, from deep-sea sampling to long-term storage in historical collections. The focus is on fixation and conservation for microscopy as well as the selection and application of imaging techniques. Although this compilation is dedicated to the morphological analysis, recommendations for sample preparation are also given with regard to genetic/omic studies as part of an integrative workflow. Given the great diversity of peracarids in the deep sea, we hope that this overview will find broad application and importance in exploring the cornerstone of any biological research there, the species.

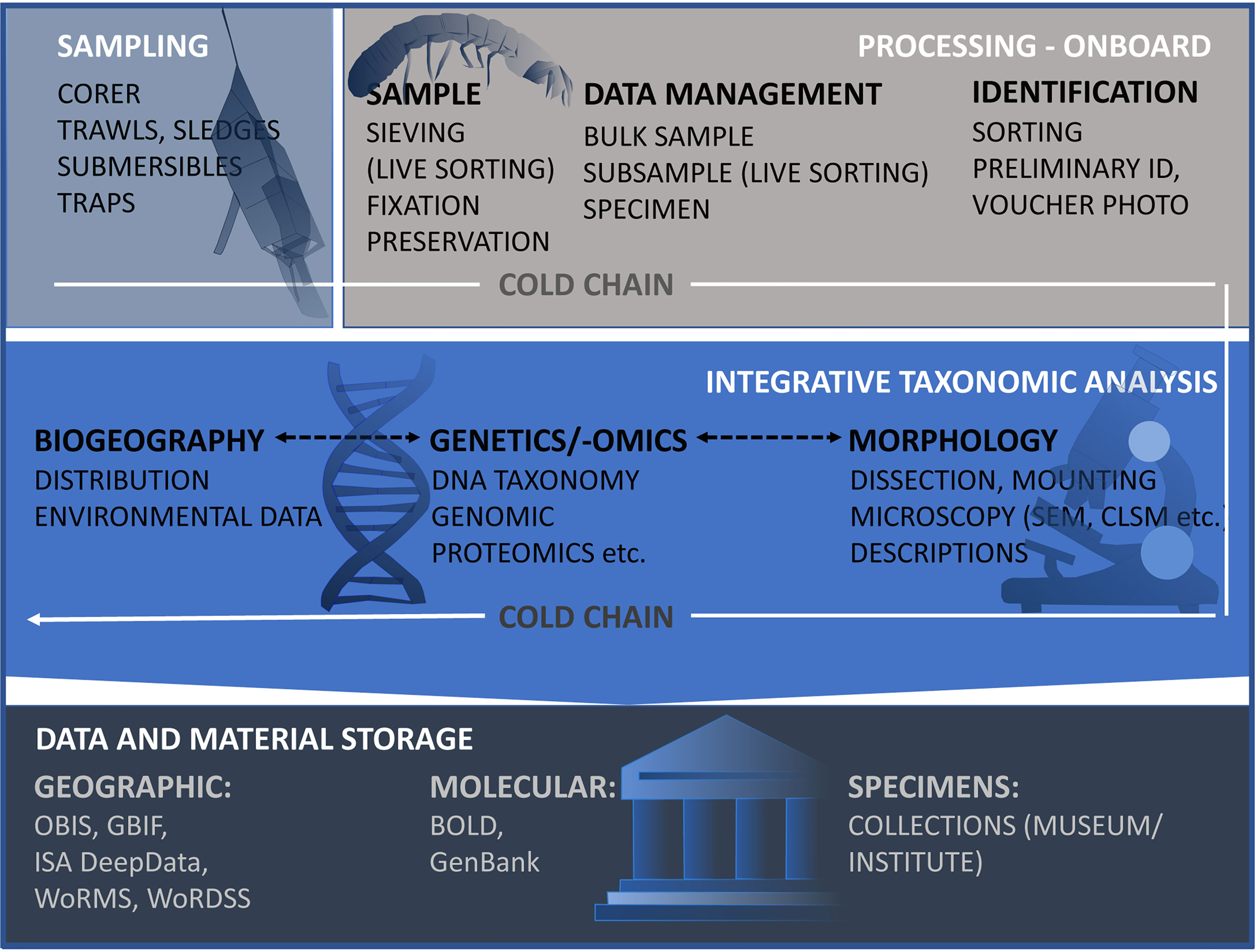

Deep-sea science is indisputably expensive and logistically difficult. Study areas are usually far away from the coast, sampling itself takes long hours, and apart from vents or seeps, faunal densities are typically low. Moreover, the ship-time costs, the effort and number of people involved to get a sample, with all the physical difficulties to successfully work at great ocean depth, make deep-sea material very precious. While this is common sense, prior to sampling consideration should therefore be given to how best to sample, process and fix samples simultaneously for various purposes (e.g., morphological, molecular, ecological and biochemical) in order to get the most out of the material. At the same time, media and methods for long-term storage need to be evaluated so that the vouchers and slides are retained for future work. A full representation of the described workflow of sample collection and processing is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Workflow to illustrate all steps that are required for the taxonomic investigation of the deep-sea peracarid fauna under the cold chain regime (Riehl et al., 2014) - from sampling, morphological taxonomic investigation, molecular and biogeographic analysis to the final storage of samples and data. Links to: OBIS, Ocean Biogeographic Information System1; GBIF, Global Biodiversity Information Facility2; DeepData, Deep Seabed and Ocean Database of the International Seabed Authority3; WoRMS, World Register of Marine Species4; WoRDSS, World Register of Deep-Sea Species5; BoLD, Barcode of Life Data System6; and Genbank7. (1https://obis.org/; 2https://www.gbif.org/; 3https://data.isa.org.jm/isa/map/; 4http://www.marinespecies.org/; 5http://www.marinespecies.org/deepsea/; 6https://www.boldsystems.org/; 7https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/genbank/).

Basically, two ways of collecting data are common: 1) still or video imagery in situ, and 2) direct sampling (Schiaparelli et al., 2016). Identification to the species level using images is difficult or even impossible for the megafauna (Hanafi-Portier et al., 2021; Horton et al., 2021), so that ex-situ examinations are required or even mandatory for the mostly much smaller Peracarida. The majority of deep-sea peracarids are sediment-bound, i.e. living in, on or just above the seabed (suprabenthic lifestyle). Depending on lifestyle and mobility of the target organisms, a variety of benthic sampling devices are used in deep-sea research. On soft bottoms, in general, coring devices, including box corer, multi- and megacorer, collect epi- and infaunal species; towed apparatus (trawls, sledges and dredges) is used for the epi- and supra-fauna; as well as baited and sediment traps, for the collections of more mobile and/or pelagic species. Manned submersibles or remotely operated vehicles (ROV) can help in the sample collection by means of push-corer, suction pump, small nets or picking up larger structures on hard substrata (for sampling specificities see Jamieson, 2016; Kaiser and Brenke, 2016; Kelley et al., 2016; Narayanaswamy et al., 2016; Frutos et al., 2017a). In water column studies, pelagic peracarid species are collected by means of mid-water trawls or plankton nets (Kürten et al., 2013; MacIsaac et al., 2014; Papiol et al., 2019); the latter are also suitable as collector of benthic peracarids if they are used as additional sampler attached to trawling devices such as otter or beam trawls (Nouvel and Lagardère, 1976; Lagardère, 1977). In addition, peracarids can also be sampled indirectly by examining the gut content of decapod or the fish stomach content, because they are their food source (Sorbe, 1981; Carrasón and Matallanas, 2001; Preciado et al., 2017). The advantages or disadvantages for the use of the aforementioned types of sampling devices are summarized in Table 1; however, an optimal choice is the combination of different equipment types to sample (Taylor et al., 2021; Ríos et al., 2022), which also provides complementary information on species behavior (Frutos and Sorbe, 2010; San Vicente et al., 2014b).

The choice of sampling devices depends on the target taxon (with regard to size class and lifestyle), seafloor topography, substrate type and depth, as well as data requirements (qualitative vs. quantitative). Benthic sledges are useful, for instance, to collect specimens with high swimming capacities (i.e. mysids and lophogastrids; Frutos, 2006), as well as relatively high specimen numbers, and thereby enable more coherent morphological and genetic assessment. Although sledges provide large numbers of peracarid fauna, additional equipment (such as opening/closing system of nets, flowmeters or pingers in the sledge frame) is required to better express abundances as densities (Brunel et al., 1978; Sorbe, 1983; Cartes et al., 1994; Dauvin et al, 1995; Frutos, 2006; Frutos et al., 2017a). Corers, by contrast, only provide low faunal densities, but offer quantitative insights when collecting undisturbed sediment surfaces (Jóźwiak et al., 2020; Lins and Brandt, 2020).

In all cases, minimizing mechanical damage to the specimens during sampling and processing to avoid loss of taxonomic information, and considering different preservation options for the same sample are important considerations. On the one hand, this includes careful handling during sampling and sample processing (washing and sieving), but also swift storage of the samples, especially if genetic or biochemical analyses are to be carried out. For example, precautions should be taken for trawled devices prior to sampling to avoid hard substrate entering the nets and grinding individuals (Kaiser and Brenke, 2016). Since sediment is part of the sample, it is important to remove it by sieving to maximize fixative concentration and thus improve sample preservation. As crustaceans can easily lose their legs and antennae, which is often essential for taxonomic identification, sediment samples should therefore be carefully sieved, if necessary with prior elutriation of the sediment samples in seawater.

Processing the samples for different purposes needs specimens to be removed from the sediment as soon as possible after the arrival of the sample on deck. Here, the maintenance in high ethanol content may arguably be even more crucial for genetic analysis (see 3.2.1 Light Microscopy) than to maintain a cold chain protocol. The latter has been thought to be essential for molecular work on deep-sea isopods (Riehl et al., 2014). For sampling under tropical climatic conditions, however, it is strongly recommended that the samples are transferred to a cold environment as soon as possible. A disadvantage of fixing the entire sample in ethanol, however, is that the tegument/cuticle of the peracarids becomes hard and stiff and could impede further morphological examination (e.g. of subcuticular elements), while the setae required for morphological determination, become brittle and can break off. Furthermore, some morphological features can only be observed in live (unfixed) specimens. For example, in deep-sea amphipods, optical structures often can only be visualized in live animals: Leucothoe cathalaa is showing the whitish pigmentation of the rounded eye before storage in preservative medium (Figure 3E, while its eyes are hardly visible in preserved specimens, even under light microscope (Frutos and Sorbe, 2013). Equally, samples that are to be frozen, e.g. for biochemistry studies, should be identified as accurate as possible and pictured before being preserved. Thus, live sorting should be considered, whenever possible, whereby the respective individuals are selected directly from the sample and individually identified, photographed and fixed (Brix et al., 2020; Ahyong et al., 2022).

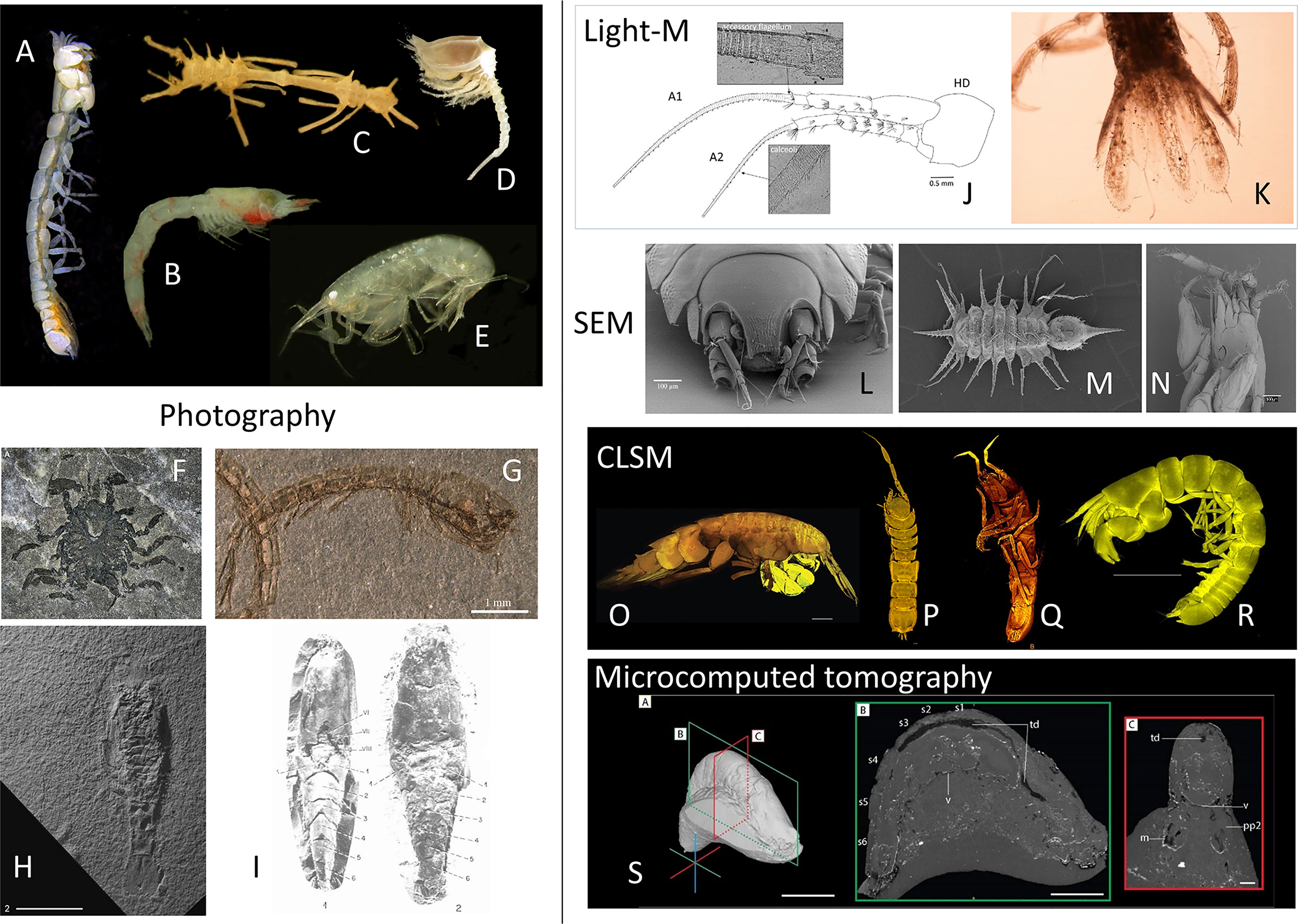

Figure 3 Peracarida specimens visualized applying different modern imaging techniques to complement the taxonomical description of species. (A–G) Digital still camera on stereomicroscope. (H, I) Still camera. (J, K) dissected specimen under Light microscope. (L–N) Scanning Electron Microscope. (O–R) Confocal Laser Scanning Microscope. (S) Microcomputed tomograph. (A) The paranarthrurellid tanaidacean Armatognathia swing Błażewicz and Jóźwiak, 2019 from Błażewicz et al. (2019) under Creative Commons license. (B) The mysid Paramblyops rostratus (Holt and Tattersall, 1905) from Frutos (2017). (C) The ischnomesid isopod Cornuamesus longiramus (Kavanagh and Sorbe, 2006), and (D) the diastylid cumacean Campylaspis vitrea Calman, 1906 from Frutos et al. (2017a). (E) The leucothoid amphipod Leucothoe cathalaa Frutos and Sorbe, 2013 from Frutos and Sorbe (2013). (F) The first asellote isopod from the fossil record Fornicaris calligarisi Wilson and Selden, 2016 from Selden et al. (2016),© The Crustacean Society, reprinted with permission of Oxford University Press on benhalf of The Crustacean Society. (G) The oldest crown cumacean Eobodotria muisca Luque and Gerken, 2019 from Luque and Gerken (2019), reprinted with permission of Royal Society Publishing. (H) The oldest known fossil mysid Aviamysis pinetellensis San Vicente and Cartanyà, 2017 from San Vicente and Cartanyà (2017), reprinted with permission of Cambridge University Press. (I) Two fossil lophogastrids of family Lophogastridae from Secrétan and Riou (1986), reprinted with permission of Annales of Paléontologie. (J) The eusirid amphipod Dorotea papuana Corbari, Frutos and Sorbe, 2019 from Corbari et al. (2019). (K) The paranthurid isopod Paranthura santiparrai Frutos, Sorbe and Junoy, 2011 from Frutos et al. (2011). (L) The nannoniscid isopod Austroniscus obscurus Kaiser and Brandt, 2007 from Kaiser and Brandt (2007). (M) The paramunnid isopod Pentaceration bifficlyro Kaiser and Marner, 2012 from Kaiser and Marner (2012). (N) The paranthurid isopod Paranthura santiparrai Frutos, Sorbe and Junoy, 2011 from Frutos et al. (2010). (O) The oedicerotid amphipod Oedicerina teresae Jażdżewska, 2021 from Jażdżewska et al. (2022) under Creative Commons license. (P) The nannoniscid isopod Thaumastosoma platycarpus Hessler, 1970 from Kaiser et al. (2018). (Q) The nannoniscid isopod Nannoniscus magdae Kaiser, Brix and Jennings, 2021 from Kaiser et al. (2021). (R) The paranthrurellid tanaidacean Paranarthrurella arctophylax (Norman and Stebbing, 1886), from Błażewicz et al. (2019) under Creative Commons license. (S) Fossil lophogastrid specimen showing internal anatomy after microcomputed tomography, from Jauvion (2020).

Fixation of specimens in taxonomic studies aims to prevent the spontaneous deterioration of taxonomically important features of the collected animals and thus its methods should be selected and applied with a thorough regard for the subsequently planned discovery pipeline of methods. The two main threats to morphological and genetic features of marine crustaceans that have to be prevented by fixation are dead cell/tissue autolysis by endogenous enzymes and destruction of biological material by microbial (bacterial/fungal) contaminants. An optimal fixative should aim to prevent both threats at the same time. Specimen fixation is of paramount importance if a significant time lapse occurs between collection and analysis, which is usually the case for marine samples, especially deep-sea ones, collected on board of research vessels and later analyzed in research institutions on dry land. In fact, the current average shelf life of new species between discovery and description is about 21 years (Fontaine et al., 2012). Furthermore, good preservation is also extremely important for material of taxonomic significance, especially type material that has to be available for subsequent re-analysis in museum collections. While the term “preservation” is usually used for application of fixatives for prolonged storage of museum specimens, both underlying principles and specific compounds used are analogous to fixation for general purposes and will be discussed together here.

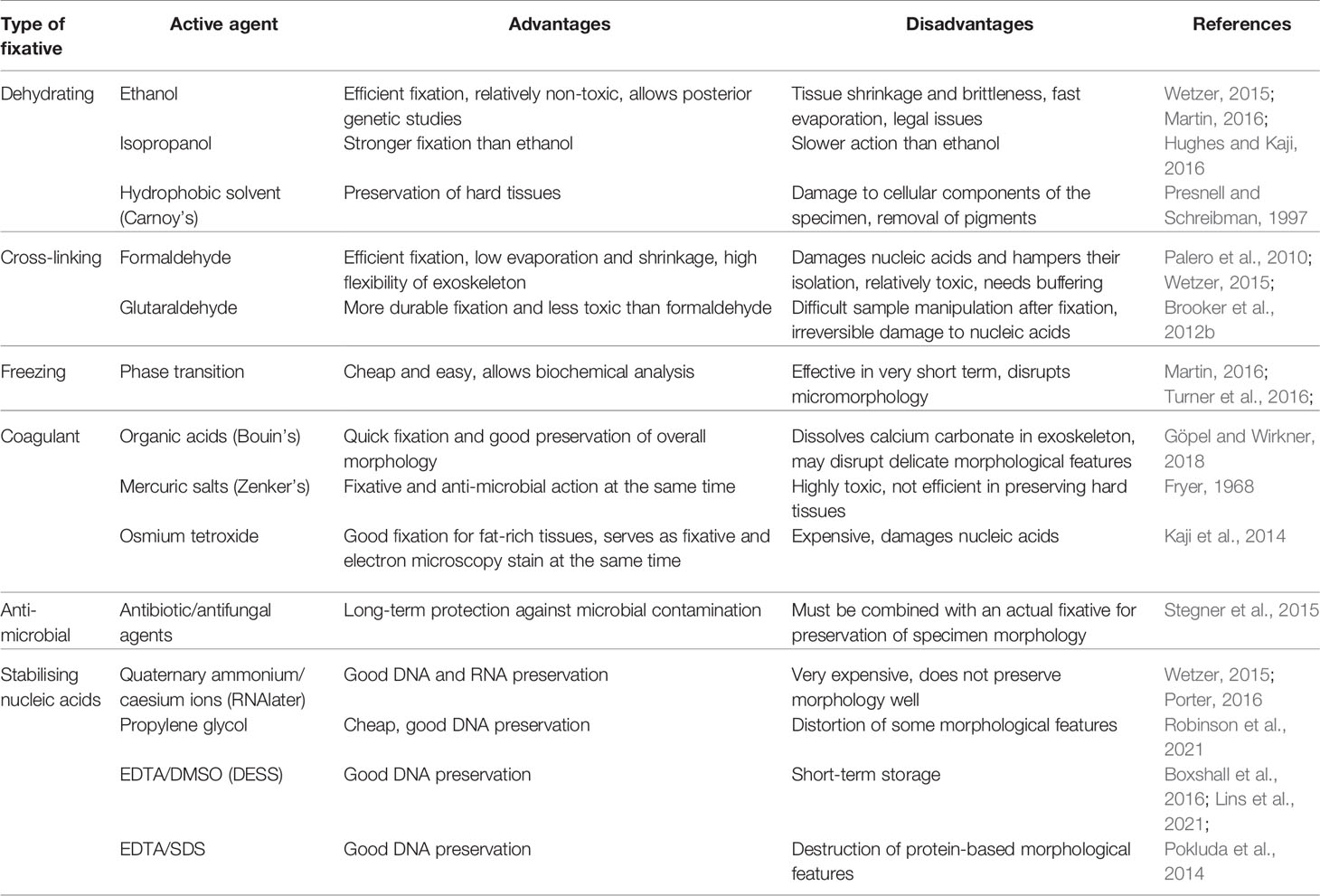

Fixation inevitably changes the physico-chemical properties of the specimen, so it has to be performed in a way that is compatible with downstream taxonomic techniques, both with regard to imaging morphology for identification purposes and to analyzing genetic and biochemical make-up of the specimen. Thus, selection of proper fixative is always a trade-off between efficiency and durability of preservation on one hand and lack of significant interference with taxonomically important features of the specimen (Eltoum et al., 2001). Among the properties that need to be considered are i.e.: crude shape changes which may result from physico-chemical processes (drying, osmotic swelling); delicate morphological elements that may be damaged during the fixation process itself; physical features that may deteriorate upon chemical reactions with the fixative, especially upon prolonged exposure (color, transparency, flexibility, malleability etc.); biochemical composition (e.g. lipid or carbohydrate content of specific tissues); integrity of nucleic acids and their accessibility to isolation; antigenic properties and/or enzymatic activity of proteins (Barbosa et al., 2014). With regard to deep-sea biological investigations, another consideration that has to be taken into account is the availability of fixative at the collection site: this includes questions of logistics (ease of transport, security), legal issues, shelf life of the fixative itself etc. Sometimes, a two-tier fixation protocol may be adopted, with simpler fixative applied on board the collection vessel for short-term preservation and subsequent exchange for museum-grade fixative during preparation for long-term storage in a biological collection. Of course, taxonomists are often confronted by the fact that the specimens to be examined have not been collected and preserved by themselves, so they no longer have a choice of fixation method, but some fixatives can be exchanged for others (e.g. ethanol can be replaced with formaldehyde and vice versa) prior to analysis if interference is expected (Pereira et al., 2019). As the published literature is contradictory about the compatibility of some fixation protocols with subsequent taxonomic analysis (especially by nucleic acid isolation, PCR and/or next generation sequencing) and anecdotal evidence for the suitability of individual protocols prevails, taxonomists are recommended to understand the physico-chemical principles of fixation and of genetic methods, so that an informed decision may be made. A classification of the fixatives most commonly used in the Peracarida taxonomic community and short description of their main advantages and disadvantages is included in Table 2.

Table 2 The most common types of fixatives used by peracarid taxonomists with their advantages and disadvantages summarized.

In some cases, taxonomic studies are performed not on specimens from extant taxa collected while still alive, but on subfossil or fossil material which is already naturally “fixed” or transformed into a relatively permanent, physico-chemically stable form. Morphology of preserved tissues may be studied in such samples using the same imaging techniques as described below for extant material – optical microscopy, electron microscopy or microcomputed tomography (Sánchez-García et al., 2016; Nagler et al., 2017; Jauvion, 2020; Luque et al., 2021; Robin et al., 2021), but the physical preparation of the sample lacks the fixation step, instead involving mechanical preparation (slicing, milling, polishing). For some taxa of deep-sea Peracarida, morphological studies of fossils using recently available imaging techniques led to taxonomic corrections and reclassification of whole groups of specimens: a decapod tail described as amphipod (McMenamin et al., 2013; Starr et al., 2016); samples that upon close investigation contained not amphipods but previously unknown genera and species of tanaids (Vonk and Schram, 2007); a new mysid genus (Cartanyà, 1991; San Vicente and Cartanyà, 2017) or a new lophogastrid taxon (Secrétan and Riou, 1986; Jauvion, 2020).

The most common fixative types in aquatic zoology can be classified into two groups: those relying on quick dehydration and those relying on molecular cross-linking of biochemical components. Both aim to quickly and efficiently inhibit the activity of enzymes (endogenous or microbial ones) which could destroy the biological macromolecules that the specimen consists of: proteases for proteins, nucleases for nucleic acids or glycosidases for carbohydrates. Dehydration withdraws the main reaction substrate for hydrolytic reactions and inactivates enzymes by coagulation-mediated denaturation. Cross-linking prevents enzyme-substrate interactions by stopping diffusion as well as by preventing conformational changes of the enzyme molecule that are crucial for its activity. Some fixation methods aim also to inhibit major lytic enzyme groups by specific biochemical interactions with their co-substrates or active sites, or to target microbial life with antibiotic toxins (Table 2).

The most universal and frequently used fixatives based on the dehydration principle are aliphatic alcohols, especially ethanol. Ethanol works by quickly mixing with water, penetrating the specimen, and removing the solvation shells from proteins and other molecules. The most efficient and rapid-acting concentration of 95–96% is considered the optimal fixative both for field fixation and long-term storage when preservation of tissue structure, biochemical composition and DNA for genetic analysis are important (Palero et al., 2010; Wetzer, 2015; Martin, 2016; Beninde et al., 2020).

While 70% ethanol is also historically used for long-term storage in museum collections due to its superior anti-microbial activity, numerous studies have shown that the increased water content and insufficient lytic enzyme inhibition leads to detectable levels of DNA degradation, correlating with storage time and therefore making subsequent genetic studies on material stored in the manner more difficult – especially for taxonomically valuable material (e.g. type specimens) (Marquina et al., 2021); moreover, the high-water content and lowered pH of 70% ethanol may lead to cuticle decalcification upon long-term storage, which is important especially for those peracarids that have taxonomically important calcium carbonate deposits in different forms (amorphous, calcite, aragonite) in the exoskeleton, e.g. isopods. On the other hand, rapid and complete dehydration by concentrated ethanol has the disadvantage of making arthropod exoskeletons stiff and brittle, as their natural elasticity depends to a large extent on extracellular matrix proteins which lose their properties when denatured/coagulated by water loss, leading to mechanical damage in transport or during dissection (Costa et al., 2021). The fragility of tegument is especially problematic in the case of some deep-sea Peracarida where delicate appendages and armament are often essential for taxonomic identification – therefore, an addition of up to 5% glycerol (by volume) during fixation and preservation would be strongly recommended as it softens the exoskeleton and makes it less fragile. In some cases, the tegument may also become opaque due to coagulated protein precipitation, hampering internal observation (e.g., of musculature or gut content), and taxonomically important pigmentation may be partially or totally dissolved, e.g. making eyes difficult to notice visually (Frutos and Sorbe, 2013; Campean and Coleman, 2018). Therefore, while 95% ethanol remains the optimal concentration for on-site fixation and long-term storage, it may be preferably exchanged for 70% ethanol in sample transit and before laboratory manipulations. Absolute (~100%) ethanol is much more expensive than 95% ethanol and may sometimes introduce microscopic morphological artefacts due to its extreme hygroscopy.

Methanol, while used in histological fixation, is ineffective for long-term storage of specimens for taxonomic purposes and should be avoided since its dehydration power is relatively weak, leading to insufficient protein coagulation and residual lytic activities. Isopropanol is as efficient in protein coagulation as ethanol and does not stiffen carbohydrate structures (carapaces) as much, but this advantage is offset by its relatively high price and slow diffusion into larger biological structures, leading to potential loss of fine details or DNA contained in internal structures (King and Porter, 2004).

Despite prevailing misconceptions in literature about ethanol with additives that make it unsuitable for human consumption (so-called denatured alcohol), these additives (e.g. methanol, ether or acetone) have no discernible effect on the fixation process, long-term preservation and downstream applications (when nucleic acids are isolated for genetic analysis, these additives are removed together with ethanol itself, and they are present in far too low concentrations to impact downstream processes anyway). The same is true for traces of benzene or its derivatives present in absolute ethanol. The misplaced recommendations against using denatured alcohol for specimen preservation for genetic analysis stem from faulty interpretation of several studies where “pure ethanol” at 95% was compared to “denatured alcohol” at 70% (as this is the concentration readily available commercially in many countries), and the above-mentioned inferior performance of the latter in DNA preservation was mistakenly ascribed to the denaturing additives (Wall et al., 2014). If denatured 95% ethanol is available, it may be used for fixing deep-sea Peracarida equally to pure 95% ethanol. The main advantages of ethanol as a fixative for taxonomy of deep-sea Peracarida include: low cost, fast action, potential for long-term storage, good preservation of DNA and proteins (including linear antigenic determinants). The main disadvantages include: high volatility (and therefore potential for evaporation from non-hermetic storage containers), flammability, legal issues (especially with transport to the collection site), need for time-consuming removal for some downstream applications (especially involving nucleic acid isolation), potential for morphological distortion by rapid water removal from small specimens with delicate exoskeletons, as well as fragility of dehydrated specimens.

The most frequently used cross-linking fixative is formaldehyde which reacts with proteins, nucleic acids as well as some lipids and carbohydrates to form a durable network of covalently linked macromolecules. For long-term storage, formaldehyde is usually used at concentration of 4% (or sometimes higher). The working solution is obtained by diluting so-called formalin (stabilized concentrated solution of ca. 36%) or by de-polymerizing the solid polymer paraformaldehyde. Formaldehyde penetrates tissues quickly and preserves structures efficiently, while not dehydrating the specimen at the molecular level, leading to full preservation of flexibility of appendages and tegument, making dissection easy. Since aquatic solutions of formaldehyde are acidic (due to hydrolysis and forming of geminal methanediol), it is crucial that this fixative is buffered to neutral or slightly basic pH (7.5–8.5) when used on marine crustaceans if biochemical integrity of the tegument is to be preserved, to prevent dissolution of calcium carbonate in their exoskeleton. The most frequently used buffering agents for this task are sodium borate (borax), sodium phosphate, sodium bicarbonate and hexamethylenetetramine (urotropin) (Presnell and Schreibman, 1997; Martin, 2016). On the other hand, decalcification in acidic formaldehyde solutions makes some tegument more transparent, allowing for easier microscopic observation of internal structures. For small aquatic animals with shells or carapaces, formaldehyde is sometimes combined with compounds that accelerate protein coagulation during the initial specimen soaking (picric and acetic acids) - this fixative is called Bouin’s solution and may be recommended where careful preservation of deep tissue morphology is of importance. An alternative for formaldehyde is the higher molecular weight bifunctional molecule, glutaraldehyde, which forms more stable and durable crosslinks, but is much more expensive, makes tissues hard and difficult to dissect and prevents any subsequent molecular analysis. The advantages of formaldehyde for peracarid taxonomy, especially used in commercial and monitoring studies, include: low cost, fast action, capacity for long-term storage (low volatility). The main disadvantages are: high toxicity (which necessitates careful handling, especially during transport), strong biochemical changes which are sometimes irreversible (DNA and RNA may be isolated from formaldehyde-fixed specimens after de-crosslinking, but it is of significantly lower quality; while some proteins retain antigenic properties, some do not), deterioration of some physical features of the specimen (tissue hardening, “tanning” - generation of secondary pigments), deformation of microscopic features by spontaneously precipitating paraformaldehyde crystals. It has been demonstrated that formaldehyde-crosslinked nucleic acids are more labile to hydrolysis, which is why they yield worse quality sequencing data; de-crosslinking is most efficient at 70°C in dilute buffer at pH=8.0 (Evers et al., 2011).

A historically common preservation technique for short-term maintenance of collected specimens until the availability of more efficient fixative is refrigeration or freezing of sample in the seawater in which it was collected. Refrigeration does not stop degradation processes, it only slows them down, while freezing (e.g., flash-freezing in liquid nitrogen) strongly disrupts microscopic morphology owing to generation of ice crystals within tissues, so these methods are recommended only when the main purpose of material collection is biochemical analysis in the near future.

While ethanol works by dehydration at the molecular level, water may be removed from the specimen also physically by drying (spontaneous, heat-induced or using hygroscopic materials such as silica gel). While common as a preservation procedure in terrestrial arthropods, this method is of highly limited applicability for marine peracarids: morphology is strongly disturbed by the drying process itself and by marine water salts, dry specimens are extremely delicate with regard to mechanical damage, inhibition of lytic enzymes and microbial growth is inefficient, nucleic acid chains tend to break. The only exception is preparation of specimens for SEM where liquid needs to be removed while preserving micromorphology – freeze-drying (lyophilisation) or critical point drying in liquid carbon dioxide are the fixation methods of choice here.

Organic solvent-based dehydrating fixatives, which are commonly used in histology, are also sometimes applied for preservation of marine crustaceans, although this is mainly of historical significance and should be discouraged for modern taxonomic analysis. Specifically, acetone or Carnoy’s solution (ethanol with chloroform and acetic acid) dissolve and wash out hydrophobic components of the specimen, including biological membranes and lipid pigments, much more strongly than ethanol, preserving only the crude external structures (e.g. the exoskeleton), which is not acceptable for museum-quality preservation.

A group of less frequently used fixatives are inorganic salt coagulants involving heavy metals that act on negatively charged groups in proteins and lipids. Osmium tetroxide is an efficient fixative for lipid-rich tissues, but its application for crustaceans is mostly limited to concurrent fixation and staining for electron microscopy (see below). Similarly, in some histological work on marine crustaceans, Zenker’s fixative is used. This solution contains highly toxic mercuric chloride acting as coagulant and providing excellent tissue fixation for detailed histological analysis. Its usage nowadays is limited, since it has to be handled with extreme care and produces hazardous waste that requires costly disposal.

Sometimes, antimicrobial additives (amphothericin, thimerosal, azide etc.) are used to prevent microbial contamination and degradation of the sample, but as they usually have a relatively narrow spectrum of action and do not influence the spontaneous degradation of dead tissue by endogenous enzymes, they can have an auxiliary function at best.

Several specialized fixatives have been developed for specimens destined for subsequent nucleic acid isolation and genetic analysis. While RNA is both inherently unstable and subject to degradation by ubiquitous and abundant RNAses, DNA (a more common object of genetic analysis for taxonomic purposes) is chemically very stable, degrading only under specific conditions, and its deterioration in unfixed specimens is mostly due to action of microbial digestive enzymes because tissues of marine invertebrates are very poor in endogenous nucleases. Thus, while commercial fixatives like RNAlater™ and other chaotropic salt-based protein denaturants aimed at rapid and efficient elimination of RNAse activity are crucial to any transcriptomic (RNA-based) analysis, they are very expensive and simpler fixatives (like ethanol) are just as efficient in DNAse inhibition if only DNA-based analysis is foreseen. Alternatives to ethanol as a fixative for DNA-based studies have been proposed (e.g. propylene glycol-containing antifreeze solution (Robinson et al., 2021) or solutions containing metal chelators that deprive DNAses of cofactors mixed with detergents (Pokluda et al., 2014) or polar solvents (Lins et al., 2021) and they facilitate subsequent DNA isolation, but they are not efficient in preserving morphology or in long-term prevention of microbial contamination, so they should be used only in targeted taxonomic studies (e.g. barcoding or metabarcoding). When selecting the fixative for a specimen that will (or may) be subjected to genetic analysis by DNA sequencing, it is important to take into account the specific technique to be used: some techniques (e.g. Illumina) sequence short fragments and thus may be efficiently used even on DNA of low quality, e.g. isolated from formaldehyde-fixed specimens; some techniques (e.g. nanopore) need long DNA molecules and thus should be applied only for material fixed with ethanol or DNA-specific fixatives. Importantly, both freeze-thaw cycles and drying-rehydration cycles contribute to DNA strand breakage and should be avoided if longer DNA is required.

Body length of peracarids rarely exceeds several millimeters. For this reason, the morphological identification of the peracarids involves observation of the details of head/cephalothorax, thorax, and abdomen appendages as well as additional components such as labrum, labium or epignath. The dissection of microscopic size requires experience, “surgical” dexterity, and precise tools. The needles used for the preparation of larger crustaceans are much too large for working with small crustaceans, while thin entomological needles are too flexible for dissection of the crustaceans. Tungsten needles, with tips although extremely fine, remain rigid and inelastic, are an ideal solution for peracarid dissection. Nowadays there are many companies on the market that offer tungsten needles, but sharpening can also be done in the lab, using solution of KOH, as copper as cathode and a low electric voltage.

Scientific drawings are the pillar of taxonomic research. Drawing practiced with the support of a camera lucida microscope enable future researchers to recognize named species (Figure 1H). In the early Linnean days of taxonomy, it was essential to prepare drawings to visualize features, but recently they are increasingly being replaced by other (e.g., photographic) techniques (Wilson, 2003; Anderson, 2014; d’Udekem d’Acoz and Verheye, 2017; Lörz and Horton, 2021), that are also being applied to fossilised specimens (Selden et al., 2016; Jauvion, 2020). There have been fierce debates over photographs or microscopic images to become substitutes for drawings or even types (cf. Zhang et al., 2017). Although changes to the International Code for Zoological Nomenclature now have a certain consistency with regard to the type problem (Zhang et al., 2017), the idea of describing species purely based on imagery or molecular taxonomic units (MOTUs) (Jörger and Schrödl, 2013; Sharkey et al., 2021) still remains the exception for peracarids.

Drawings provide an interpretation often in a rather schematic way. The traditional scientific drawing workflow is clearly a lengthy one, starting with pencil drawings, followed by inking, scanning, as well as editing and arranging plates (Figures 1G–J). Yet, pencil and ink drawings, on the one hand, aid in-depth examination of the morphology and, on the other hand, distracting details may be omitted if they are systematically uninformative. Besides, drawing habitus of poorly calcified specimens enables us to visualize the morphological characters which cannot be well pictured by camera because of low contrast. Images, on the other hand, ideally give a precise representation of the morphological structures (also with regard to coloration and patterns, see amphipod example above), even more so with the development of high-resolution imaging techniques (Kaiser et al., 2018; Błażewicz et al., 2019; Jażdżewska et al., 2022). In addition, photography is far less subjective than creating drawings, but despite these advantages has so far rarely found its way into peracarid taxonomy.

The preparation of drawings presenting details of morphological structure has been historically/traditionally carried out by means of a camera lucida attached to the microscope. This device is a simple system of mirrors (Wollaston, 1807) which makes it possible to reproduce an object (body habitus or appendages) on a sheet of paper placed next to the microscope (Figure 1H). Despite the simplicity of its design, the camera is a relatively expensive piece of optical microscope equipment: only few optical companies manufacture them, and they are not usually exchangeable between different models of microscopes. In addition to the traditional use of camera lucida, focus-stacked microphotographs can be the baseline for drawings (Coleman, 2006) or even substitute for pencil drawings (d’Udeckem d’Acoz and Verheye, 2017; Wilson and Humphrey, 2020). Nevertheless, both camera lucida and stacked microphotographs techniques can also be applied together for producing drawings of fossils (Selden et al., 2016). The appropriate camera and acquisition software to equip the microscope are also expensive.

Microscopic images are useful to complement scientific drawings when studying rare (singleton or unique) species. While this is a general phenomenon in the description of species (Lim et al., 2012; Wells et al., 2019), it becomes particularly evident in the morphological analyses of deep-sea species including peracarids (Brandt et al., 2012; Higgs and Attrill, 2015). Drawings without dissecting parts of the specimen are often sought not to sacrifice the holotype, but it is thanks to the use of imaging techniques, chiefly non-destructive methods (such as CLSM, see below), it is possible to fill in missing gaps of morphological information. However, it is clear that not always taxonomist have access to all facilities to use such as useful techniques and methods.

So far, however, no efforts to refrain from drawings in peracarid taxonomy have been taken but, on the contrary to bring together as much information as possible (including molecular, ecological, and biogeographic) as part of an integrative process (Brix et al., 2015; Malyutina et al., 2018; Kaiser et al., 2018; Schnurr et al., 2018; Błażewicz et al., 2019; Jakiel et al., 2019; Riehl and De Smet, 2020; Kaiser et al., 2021). Above all, the use of digital drawing techniques and the corresponding software (something expensive as well) has made a significant contribution to reducing the time required for, and improving the quality of species illustrations (Coleman, 2003; Coleman, 2009; Bober and Riehl, 2014; Montesanto, 2015). However, much greater advances appear to have been achieved in the development of 3D reconstruction and imaging techniques.

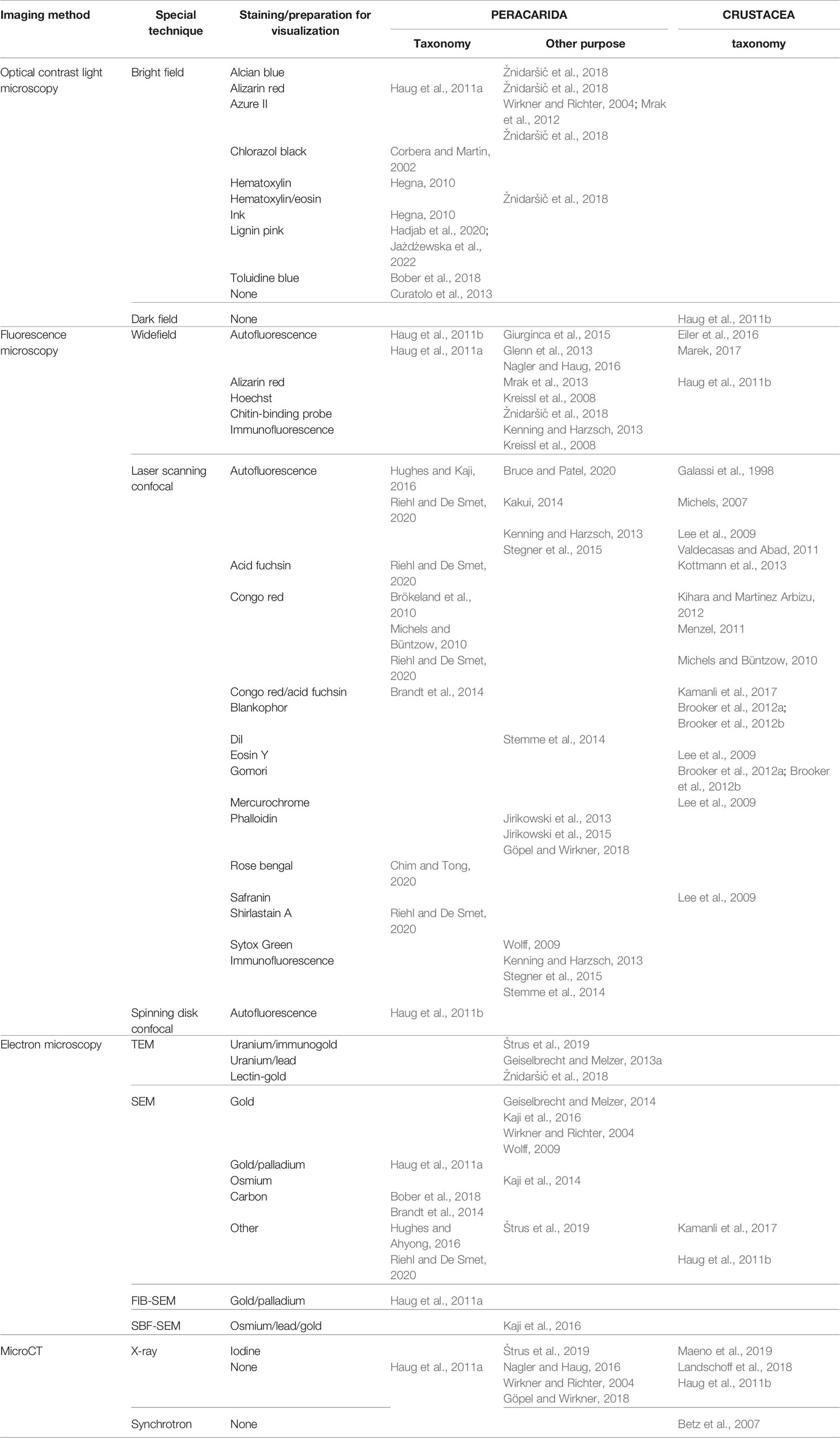

Morphology (i.e., shape of the organisms and its parts) is still the most important taxonomic characteristic and thus methods of its recording and analysis – imaging methods – are crucial tools in the armory of a taxonomist of deep-sea Peracarida (Figure 3). Concentrating on imaging for taxonomic purposes, we need to differentiate the imaging of overall morphology (habitus) which may be performed without any previous zoological knowledge (Figures 3A–I), and imaging of specialized, taxonomically important features, the choice of which must be informed by accumulated knowledge and expertise. For deep-sea peracarids, where specimens are difficult to obtain (complicated logistics), available in limited numbers and thus are highly valuable, an important consideration is the distinction between imaging taxonomically important morphological features in situ (in intact specimens) versus imaging of prepared or isolated body parts (ex situ, after dissection and/or sectioning, Figures 3J, K), which may be sometimes necessary even for type specimens. When selecting imaging techniques, some thought must be also paid to the location of taxonomically distinctive features within the body of the crustacean – some techniques are exclusively suited to imaging external morphology (e.g. SEM, Figures 3L–N, or CLSM, Figures 3O–R), while others were developed specifically for imaging internal organs and hidden features (e.g. microCT, Figure 3S). Finally, a modern taxonomist must bear in mind that imaging can be used not only for purely morphological (shape-related) analysis, but specific contrast techniques are available to draw conclusions about biochemical composition of tissue elements as well as course of physiological processes which may be helpful as additional taxonomic characteristics and form an additional level of analysis (apart from morphological and genetic ones). Table 3 includes recent examples of application of specific imaging techniques which will be reviewed below to Peracarida and other crustaceans.

Table 3 Selected examples of literature references where different imaging techniques were used to study the taxonomy of peracarids and other crustaceans or were applied to visualize peracarids for non-taxonomic purposes.

While bright field light microscopy is the original method in taxonomy of any small organisms, its applicability to deep-sea Peracarida is limited by the relative lack of inherent contrast in their bodies. Light microscopy relies mainly on absorption, refraction, and dispersion of incident rays in the specimen, and marine crustaceans tend to be colorless (low absorption) and with optical refringence that is uniform and similar to surrounding seawater. While habitus imaging may be performed on whole specimens by reflected light stereomicroscopy in air (Hegna, 2010), the resulting images are poor in details and thus of low usefulness in taxonomy.

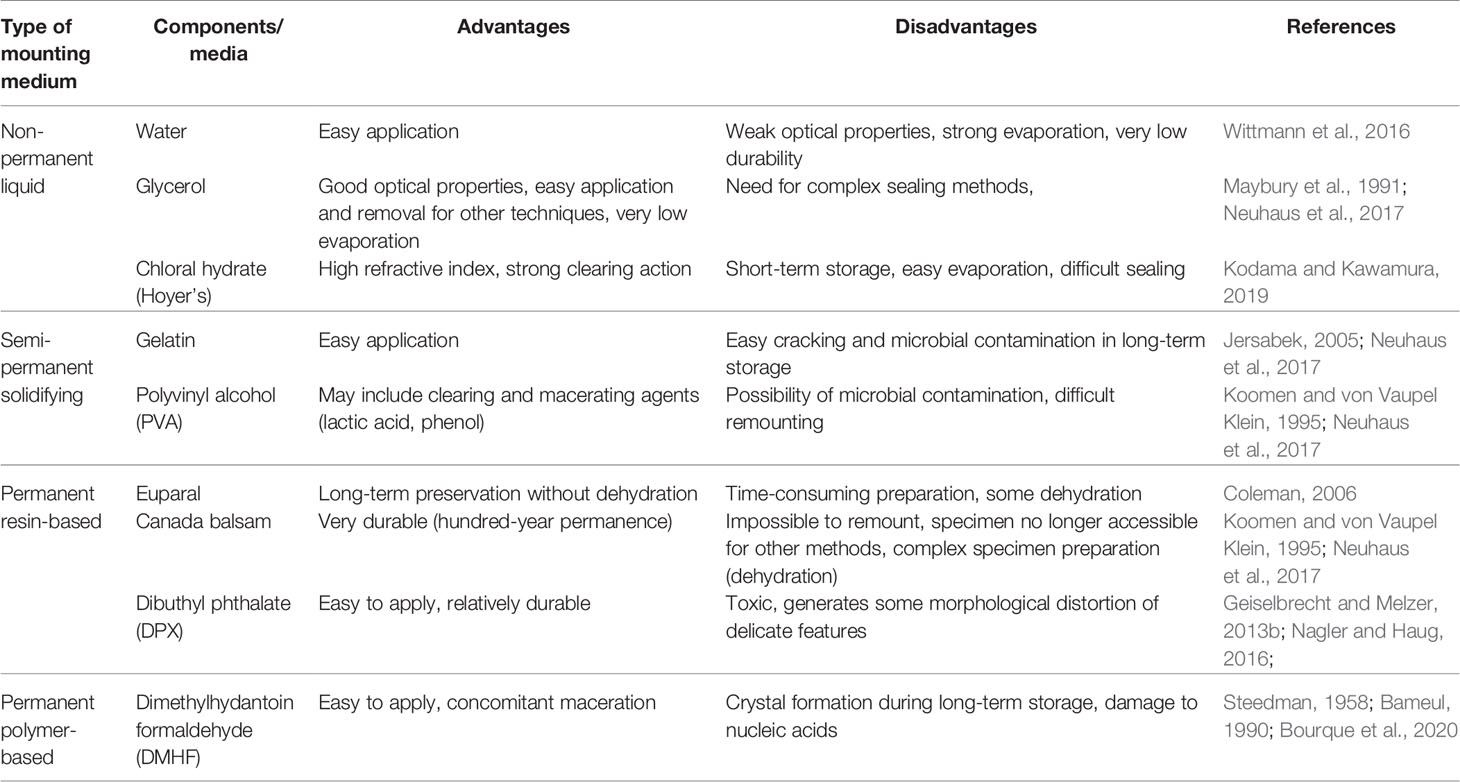

Most commonly, zoological specimens are prepared in a procedure called mounting, where the animal is placed on a glass slide in a drop of liquid and covered with another flat piece of glass (the thickness of this cover glass is adapted to the working distance of the microscope objective to be applied). Mounting has two main purposes: to prevent the desiccation-related destruction of specimen, and to provide an environment with uniform refraction properties in order to minimize image blurring due to photon scattering on phase borders. Therefore, the mounting medium for marine crustaceans must mix well and rapidly with seawater, and its refractive index should be as close as possible to that of glass (1.52). While animals can be mounted in water itself for short-term observation (e.g. on board), it evaporates quickly and a different mounting medium is needed if the specimen is to be stored as microscope slide. The most important decision in the choice of mounting medium is related to the desired permanence of the slide: specimens in non-permanent (liquid- or gel-based) media may be manipulated, moved around, remounted, or even removed from the slide for other type of analysis; permanent (solidifying) medium preserves the slide permanently in the same attitude of the specimen. Sometimes, the mounting medium includes components that have additional functions with regard to the specimen itself: clearing (optical homogenization by removal of light-scattering inclusions) and/or maceration (chemical removal of unwanted tissue, e.g. muscles inside the tegument). These components are usually acids (e.g. lactic acid) or bases (e.g. potassium hydroxide), and care must be taken not to exceed the necessary dosage and, if possible, to remove the agent before final mounting, as they may progressively destroy taxonomically important features or even the whole specimen during prolonged storage. Table 4 lists the commonly used mounting media for microscopic imaging of Peracarida with their main advantages and disadvantages.

Table 4 Advantages and disadvantages of mounting media commonly used for light-microscopy studies of peracarids.

The most common components of non-permanent mounting media used for taxonomic imaging of small marine arthropods include: glycerol (higher refractive index than water and negligible evaporation; sometimes mixed with 10% saline to facilitate mixing during slide preparation), gelatin (less recommendable as it is prone to desiccation and cracking), polyvinyl alcohol (included in the popular commercial mounting medium Mowiol and in the complex self-made medium polyvinyl lactophenol), and chloral hydrate (included together with glycerol in popularly used Hoyer’s medium, where it contributes to its high refractive index). They are often used in personally formulated mixtures based on experience and anecdotal evidence on performance – it is possible that some are more suitable for certain systematic groups of Peracarida than others, but systematic studies are lacking and it seems that subjective personal preference remains the main argument for mounting medium choice. Oil-based mounting media are also available, but rarely used for invertebrate taxonomy as they do not perform well with carbohydrate exoskeletons. Permanent (solidifying/hardening, either by physical curing or by chemical polymerisation) mounting media are also often used for museum specimen storage, but this practice prevents any further manipulation of the specimen (including potential new molecular discrimination techniques) and should be discouraged for rare type material where methodological developments in molecular studies may warrant the need for access to relatively unchanged biological material in distant future. However, permanent mounting may be recommended for long-term storage of dissected parts (e.g. appendages) which are of purely morphological value. While some resin-based solidifying media are marketed as reversible (they may be liquefied by heating with an excess of solvent), both morphological structure and biochemical composition is usually compromised by such treatment and all solidifying mounting media should be treated as permanent. The most common base ingredients of solidifying mounting media used in taxonomy of Peracarida include natural resins (Canada balsam, Euparal and others that solidify by gradual solvent evaporation and vitrification), synthetic resins (included in such preparations as DPX or Permount) and formaldehyde-based polymers (mainly dimethylhydantoin formaldehyde – DMHF – which is recognized as superior to resins due to much less cracking and bubbling artefacts; Bameul, 1990).

If the entire or dissected specimen is to be preserved in long-term storage in the form of microscope slide mounted in liquid medium, this slide must be also sealed using impermeant sealants that isolate the specimen from external moisture and oxygen (numerous commercial products are available, e.g. based on linseed oil, plant resins, paraffin or acrylic glue; even simple nail varnish may be used for this purpose, but care must be taken that its components do not interfere with any staining that was applied) (Allington-Jones and Sherlock, 2007). When considering long-term storage in non-permanent mounting media, the question of microbial contamination potential must be also taken into account: glycerol-based media are most resistant to contamination, while microbes grow most easily in those containing gelatin. Since the function of the mounting medium requires the compounds involved to thoroughly permeate the specimen, it needs to be extensively washed if it is required at some later point to release it from the slide after microscopy for some other (e.g. genetic) analysis. Common liquid mounting media (e.g. glycerol-based) do not damage nucleic acids and can be removed by washing, but polymerizing permanent mounting makes isolating DNA from the sample impossible.

For transmitted light imaging, the standard procedure is to stain the specimen with light-absorbing dyes to create contrast. In current practice for taxonomic purposes, researchers aim to use non-selective stains to visualize most tissue types and structures (in crustaceans, the most important element being usually the exoskeleton and its outgrowths, especially on the appendages). The most commonly used dyes are hematoxylin (which stains nucleic acids – and thus living tissue – dark blue) (Hegna, 2010) and eosin (which stains most biological macromolecules, including those in the extracellular matrix and exoskeleton, pink), most often combining these two as counterstains (Žnidaršič et al., 2018). Other, more selective dyes can also be used to stain crustaceans, including azure II (stains polysaccharides, including cuticle components), alizarin red (stains calcium deposits in calcified carapace), chlorazol black (basic dye that stains anionic macromolecules, mainly nucleic acids), alcian blue (basic dye for acidic glycans in connective tissue), toluidine blue, lignin pink (both glycan-selective stains with differing affinity) or even the non-selective India ink that stains by physical interactions. Specimens stained using these techniques are usually mounted by immobilization on standard microscope slides, but sectioned or dissected samples may be also prepared after staining. Image is recorded by photographic cameras attached to standard light microscopes or even simply by drawing (see Preparing Drawings). If a specimen stained with a cationic dye is to be subsequently used for DNA isolation, an additional washing step may be included to remove the bound dye which might impact downstream reaction efficiency. Some fluorescent DNA-binding (intercalating) dyes (see below) are virtually impossible to remove from DNA during isolation, but there are few reports (from experiments on tissues of vertebrates) finding them interfering even in complex genetic procedures (e.g. next generation sequencing), so this should not be a critical issue in invertebrate taxonomy.

The indisputable advantage of bright field light microscopy imaging is the common availability of cheap instrumentation which requires little specialist training on the part of the researcher. Light microscopes are usually available, even on board research vessels, and can be used for imaging of freshly collected specimens before fixation. When combined with staining, this technique can provide convincing basis for quantitative measurements and rudimentary conclusions with regard to biochemical composition of some structures (e.g. carapace calcification). The central disadvantage is the relatively poor contrast, both against the background and internally within the imaged specimen, leading to potential obfuscation of taxonomically important morphological differences and features. Standard light microscopy (both in reflected and transmitted light) is poor in rendering internal structures of the body and requires extensive dissection to image complex elements (like appendages). Efficiently imaging three-dimensional structures is not possible, even though they may be observed by stereomicroscopy (attempts have been made to construct and publish 3D images of Amphipoda to be viewed through red-cyan glasses, with limited success (Haug et al., 2011a). Nevertheless, taxonomical descriptions relying on bright field images of unstained or stained Peracarida continue to be routinely published, e.g. new amphipod species imaged after lignin pink staining (Hadjab et al., 2020) or new isopod species stained with chlorazol black (Pereira et al., 2019).

The contrast problem has led to the application of some specialized variants of optical contrast light microscopy (which all require technical add-on enhancements to the microscope itself which are relatively rare in zoological laboratories). One technique which has found use in taxonomically useful imaging of arthropods is dark field microscopy, where incident light is directed at the specimen in such a way that it does not pass into the objective unless deflected (reflected, refracted or scattered) by the specimen, leading to improved contrast against background and higher salience of delicate surface structures (Haug et al., 2011b). Another applicable method is polarization contrast that can underline differences in thickness and density of thicker homogenous structures formed by the cuticle (Fernández del Río et al., 2016; Melzer et al., 2021). Finally, interference contrast (also known as Nomarski contrast) is a powerful technique enabling the visualization of fine ultrastructural details. It has hitherto found application in deep-sea isopod and amphipod species taxonomy (Bruce, 1995; Bruce, 1997; Just, 2001; Tomikawa and Mawatari, 2006; Storey and Poore, 2009) but also in coastal and freshwater species (Shimomura and Mawatari, 1999; Shimomura and Mawatari, 2000; Tanaka, 2004; Jaume and Queinneck, 2007), demonstrating its power in imaging fine morphological structure of appendages (Maruzzo et al., 2007).

The most common solution to the contrast problem in biological microscopy is to make use of fluorescence, the physical phenomenon where some compounds (called fluorophores) absorb light of higher energy (lower wavelength) and subsequently emit light of lower energy (higher wavelength). This difference in wavelength, called Stokes shift, makes it possible to design microscopes which separate the incident (illumination) light from the light emanating from the sample, and thus obtain an image exclusively of the fluorescent elements within the sample. For most biological specimens, fluorescence microscopy requires staining with fluorescent dyes (fluorophore-containing compounds which bind to specific structures in the sample). Crustaceans (and arthropods in general), however, usually display relatively strong fluorescence of endogenous compounds (so-called autofluorescence) in intact specimens, allowing for easy fluorescence microscopy imaging and accounting for the widespread use of this technique in taxonomy. While biochemical studies of compounds responsible for autofluorescence in crustaceans are still too few and this field needs further intensive research, most parts of crustacean exoskeleton exhibit a broad-spectrum, near UV-excited autofluorescence that is a consequence of its highly cross-linked structure with glycan and protein components both contributing to the resulting fluorophores. Serendipitously, formaldehyde fixation tends to strengthen this broad-spectrum fluorescence component, making it even easier to image specimens fixed in this way (Hughes and Ahyong, 2016). Another source of autofluorescence is the elastomeric protein resilin, abundant in sites that are under strong mechanical stress such as tegument joints or mouthpart appendages, which contains dityrosine crosslinks that generate autofluorescence. Finally, some metabolic compounds (flavins, pterins, porphyrins, etc.) present in tissues also have fluorescent properties, enhancing the potential for fluorescent imaging of unstained specimens (Riehl and De Smet, 2020). Some arthropods have evolved dedicated autofluorescent compounds, probably important for ecological interactions, such as in some hoplocarid mantis shrimps with markings containing a yellow fluorescent fluorophore that are important in visual recognition or in shallow water copepods which contain dedicated fluorescent proteins similar to the more well-known ones from cnidarians. This ecologically motivated autofluorescence is even more common in terrestrial arthropods such as scorpions (which produce coumarin pigments) or millipedes (which rely on pterins). However, in crustaceans from the aphotic zone these dedicated fluorophores have not been detected yet and the observed autofluorescence seems to be a side effect of the biochemical structure of tissues and tegument (Glenn et al., 2013). Fluorescent properties may be used to enhance the visual signal generated by bioluminescence in deep-sea Peracarida that display this property, thus being ecologically important for visual communication within the species or between different species. Examples include, the lanceolid amphipod Megalanceola stephenseni (Chevreux, 1920) and amphipods from the families Pronoidae, Scinidae and Lysianassidae (Herring, 1981; Zeidler, 2009), mysids from family Mysidae (Herring, 1981) and the lophogastrid Neognathophausia ingens (Dohrn, 1870) (Frank et al., 1984), the fluorescence of which seems not to originate from the species itself, but rather to be dependent upon components of its food (Wittmann et al., 2014). This topic needs further studies on living specimens, preferably in situ (Macel et al., 2020). In any case, the presence of autofluorescence does not preclude the use of additional staining of specific structures in the crustacean body with fluorescent dyes for taxonomic purposes, but its continued presence needs to be taken into account for potential spectral overlap when selecting imaging channels.

When using fluorescence microscopy for taxonomic purposes, specimens are often stained with fluorescent dyes to further enhance contrast and facilitate the imaging of structures with defined biochemical composition. With regard to their mode of action, these dyes can be divided into four groups:

1) Broad specificity acidic dyes, which bind mainly to carbohydrates in the tegument. They are useful in detailed imaging of appendages, exoskeleton protrusions etc., while staining virtually the whole body of the animal to a different extent. The most commonly used dyes from this group are acid fuchsin (Riehl and De Smet, 2020; Kaiser et al., 2021) and Congo red (Michels and Büntzow, 2010; Kihara and Martinez Arbizu, 2012). An interesting example is rose bengal, a halogenated fluorescein derivative which has the capacity to bind cellular components as well, but in the presence of abundant extracellular carbohydrate material binds mostly to it. In the taxonomy of deep-sea Peracarida, its main use is for transient staining of (usually formaldehyde-fixed) mixed material to aid in visual sorting (due to its strong color) (Hegna, 2010), but its fluorescent properties allow it also to be used in whole-body fluorescence microscopy (Chim and Tong, 2020).

2) Carbohydrate-specific dyes, mostly taken over from the textile industry. They are i.a. Blankophor/Calcofluor (Brooker et al., 2012b), Shirlastain or aniline blue, which bind mainly to chitin in the exoskeleton (Riehl and De Smet, 2020).

3) Calcium binding stains, that are useful to identify calcified parts of the skeleton, such as calcein or alizarin red (Haug et al., 2011a).

4) Cationic dyes, which mainly bind to nucleic acids and stain living tissues more or less uniformly. They are safranin, eosin, DAPI or Hoechst family dyes (Kakui and Hiruta, 2017).

More specialized fluorescent probes binding to cellular or subcellular elements with restricted distribution may also be used, e.g. cytoskeleton-specific binders such as phalloidin or fluorescent antibodies (this technique is called immunofluorescence), but this is of limited usefulness in taxonomy and more commonly found in physiological or embryological studies. Both autofluorescence and probe/dye fluorescence is subject to a phenomenon called photobleaching, where long-term illumination causes a chemical reaction that destroys fluorophore molecules, leading to decreased image brightness. This can be slowed down by including so-called anti-fade components in the mounting medium, but this is rarely necessary with the bright and stable fluorophores used for taxonomically relevant imaging of crustaceans.

With regard to instrumentation, the simplest application of the fluorescence microscopy principle is the widefield fluorescence microscope which uses the same optical principle as a bright field microscope, but separates optical paths of excitation and emission light using filters and dichroic mirrors. Images generated in a widefield microscope can be viewed directly through the eyepiece or recorded using photographic or motion cameras. They can also be overlaid in-microscope with bright field images, pinpointing the location of fluorescent structures within the whole body of the animal. Widefield image quality is restricted by the so-called out-of-focus blur, i.e. light emitted from above and below the focal plane which enters the objective and decreases the image sharpness. This can be strongly limiting in the imaging of small taxonomically important elements within a larger structure. Therefore, an increasing number of taxonomic studies make use of another fluorescence imaging modality, so-called confocal microscopy. A confocal microscope retains only the objective lens from a standard optical microscope setup and images only a single point within the sample (so-called confocal volume), using regulated apertures (here called pinholes) to cut off out-of-focus illumination from both excitation and emission light paths. Therefore, a confocal microscope does not generate an image, but measures the fluorescence intensity in a spatially defined point within the sample. An image is subsequently reconstructed digitally by dedicated computer software from data collected from various confocal volumes, as the illumination is scanned across the sample. The scan may be effected in two ways: either by using optically deflected laser beams (laser-scanning confocal microscopy, in zoology usually known under the less logical name confocal laser scanning microscopy or CLSM) or by using spinning discs (Nipkow discs) with multiple pinholes (spinning disc confocal microscopy). While spinning disc confocal microscopy generates images much faster and with higher inherent brightness, these advantages are mostly important in imaging live specimens, which is rare for deep-sea taxonomical purposes. The relative rarity and costliness of spinning disc microscopes combined with their lack of versatility make them a niche tool for crustacean taxonomy when compared to laser-scanning microscopes (Haug et al., 2011b).

A confocal image is not “recorded” in a way that a camera records a widefield image, but is reconstructed from individual pixels in silico, so the native form of this image is already digital and with no loss of quality upon digitization. Since the confocal volume can be moved across the sample in all directions, a confocal microscope can be used to record three-dimensional images of specimens, making it especially useful in crustacean taxonomy where many important features such as appendage structure are inherently three-dimensional (Figures 3O–R). Properties of light, however, restrict the image resolution in the Z axis (parallel to the long axis of the objective) to ca. 2–3 times less than lateral resolution, so confocal images are never truly 3D-isomorphic. If isomorphism is absolutely necessary for taxonomic purposes, several images with different specimen orientation must be recorded. Since laser scanning confocal microscopy involves moving a small confocal volume around a large specimen, it is notoriously slow, with a good resolution image of an average-sized deep-sea crustacean taking more than 10 hours to record. Moreover, because for good resolution it is necessary to use medium-magnification objectives which usually do not allow the whole animal to fit in a single field of view, sophisticated software must be used to reconstruct the whole image from several adjacent scans in a procedure called tiling – its success (the lack of visible artifacts on scan joints) depends largely on the quality of the objective (spherical aberration correction). When recording 3D confocal images and using them for taxonomy, the way that they will be presented and disseminated in the literature must be considered, because the original files are usually too large to include even as supplementary information in published articles. A number of 2D projections (most common being maximum intensity projection and surface projection) have been developed to help present 3D data.

Electron microscopy is a group of imaging techniques which use physical effects which happen when the sample is illuminated with a stream of high-energy electrons: usually, transmitted, scattered or secondary electrons are detected. The main advantage of electron microscopy in biological imaging is the potential to generate images of much higher inherent resolution than light microscopy, since the electron beam is equivalent to radiation with a very short wavelength compared to visible light. However, for purposes of taxonomy of macroscopic invertebrates, this aspect rarely comes into play, since subcellular features (and generally features of submicrometric size) are not often used as taxonomically defining. The variant of this technique that is most often used by taxonomists is scanning electron microscopy (SEM), where the sample is illuminated by a narrow electron beam which moves across its surface and secondary electrons emitted from every spot on the way (only from the surface since they have too low energies to escape from lower layers of material) are measured using an array of detectors, recreating in real time a spatial map of the surface relief. The main advantages of this method which make it so attractive for imaging for taxonomic purposes are: high sensitivity to small changes in surface geometry which makes it possible to efficiently image surface texture and generate high-resolution images of delicate and complex structures such as those abounding on crustacean exoskeletons and appendages; high depth of field which retains in focus structures that are far away from each other along the z axis, generating a realistic and sharp image of the whole macroscopic specimen while retaining sub-microscopic resolution; the ability to modify magnification in a wide range (from several-fold to tens of thousands-fold) in a contiguous, real-time manner while conducting observations; and the possibility to easily reconstruct three-dimensional measurements from images or generate true 3D images of the specimen by recording images from two different angles. However, the method has also significant disadvantages, mostly related to the onerous and highly invasive sample preparation required for imaging in a typical SEM instrument: since both the high-energy illumination electrons and the low-energy secondary electrons that are being imaged can be deflected by interactions with air molecules, low-pressure vacuum environment is needed around the sample, which means it cannot contain water (so, biological samples must be dehydrated before imaging); since atoms contained in organic compounds do not interact with high-energy electrons efficiently and do not generate many secondary electrons, it is often necessary to coat the specimen surface with a layer of higher atomic number atoms which will produce a brighter image; the absorption of electrons by the specimen generates a high static electrical charge which would quickly lead to scanning artifacts, discharges and specimen destruction if not removed, thus the specimen must be electrically conductive or coated with a material which conducts electricity. For these reasons, SEM is a destructive technique and specimens of Peracarida prepared for SEM imaging cannot usually be used subsequently for any further preparation or analysis using other methods. The sample preparation process for deep-sea crustaceans for SEM imaging has several important steps at which different approaches may be taken depending on specific needs of the researcher. Due to the high energies and harsh treatment involved, the specimen needs to be fixed in a strong fixating agent, usually glutaraldehyde or a mixture of glutaraldehyde and formaldehyde. Dehydration cannot be achieved by air drying as this would destroy delicate surface structures, so water is first replaced by an organic solvent (e.g. ethanol or acetone), and this solvent with higher vapor pressure may be either evaporated directly with less damage to the specimen or it may be replaced with liquid carbon dioxide which then evaporates in conditions around its phase transition critical point (where gas and liquid densities are equal, removing the damaging surface tension - so-called critical point drying). For imaging, the specimen may then be coated with a thin layer of metal (such as gold, platinum, palladium or their mixtures) which provides both better secondary electron emission and electrical conductance, or with a layer of powdered carbon (graphite) which only increases conductance. Another useful metal with unique properties is osmium – its tetroxide is an efficient fixative due to the ability to bind lipids (see the chapter on fixation), coating with osmium itself provides conductivity, and both treatments strongly increase contrast due to efficient secondary electron generation.