- 1Department of Business Administration, Cheng Shiu University, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

- 2Institute of Marine Affairs and Business Management, National Kaohsiung University of Science and Technology, Kaohsiung, Taiwan

Taiwan is one of the largest distant water fishing (DWF) nations worldwide, and relies largely on the migrant labor to keep costs low. However, this industry has caused Taiwan to be listed in the 2020 “List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor” of the U.S. Department of Labor. In view of this, the Taiwanese government is actively adopting further management measures to supervise the domestic and foreign fishermen agencies. It is because the latter has been involved in many disputes, especially in recruitment, payroll, and labor contracts, which directly or indirectly affect the rights of migrant fishermen. On the other hand, although the C188 Work in Fishing Convention has stregthend the protection of the fishermen’s human rights, it still stays ambiguous in terms of private agency management. That is also why so many disputes have been caused in recent years.This study conducts a comparative analysis of the agency management systems in the primary source countries of Taiwan’s distant water fishing migrant fishermen (that is, Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam), as well as interviews with distant water fishing stakeholders to provide insights on the improvement of agency management and migrant fishermen’s rights in Taiwan. The findings imply that the positive interaction, mutual trust, and understanding of laws and regulations between fishermen’s exporting and importing countries lead to future cross-national collaboration. This study suggests that the Taiwanese government should follow the spirit of the C188 but not be restricted to the Convention texts to amend or formulate regulations and policies of agencies for fully protecting the rights of migrant fishermen.

1. Introduction

More than 40 million people worldwide are trapped in modern slavery, and more than 24 million are in forced labor (Minderoo Foundation, 2018). The global fishing industry is currently plagued by forced labor, and consumers are unaware of the true cost of buying seafood in shops or restaurants, while exploited workers are exposed to the risk of unpaid labor, exhaustion, violence, injury, and even death. Therefore, the distant water fishery industry is considered one of the most dangerous occupations. The majority of this workforce comes from Southeast Asia, where unethical agencies target vulnerable groups such as the poor, and recruit fishermen in large numbers without the commitment to good wages at sea (The ASEAN Post, 2019; Scalabrini Migration Center, 2020; Urbina, 2022), violating United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 10: Reduce inequalities.

In 2020, the U.S. Department of Labor (USDOL) reported the 2020 List of Goods Produced by Child Labor or Forced Labor. For the first time, Taiwan’s DWF products were listed as forced labor and included in the list, seriously affecting Taiwan’s international reputation (Thomas, 2020). According to the report, although Taiwan’s DWF industry is ranked second only to China, migrant fishermen often encounter forced labor issues, such as unpaid wages, withholding of passports, excessively long working hours, hunger, and dehydration; these are severe violations of forced labor rules. The report points out that during the recruitment process, overseas agencies sometimes use false wages or contracts to deceive fishermen and require them to pay recruitment fees and sign debt contracts (USDOL, 2020).

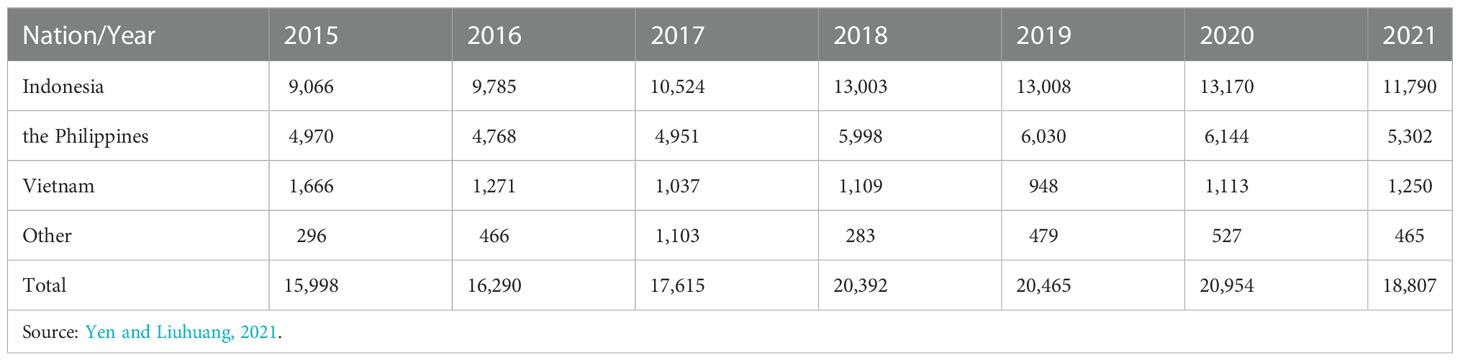

Fishing is a labor-intensive industry, and labor shortages have appeared acute in Taiwan due to the industry structure change. Therefore, importing foreign crew has been the primary means of filling the labor gap. The statistics exhibit that the number of domestic DWF workers in Taiwan has dropped from 26,000 in 1990 to 12,000 in 2020, and it is still showing a trend of continuous decline. Moreover, in 2021, Taiwan’s DWF enterprises employed 18,807 foreign workers, of which 11,790 (62.7%) from Indonesia, 5,302 (28.2%) from the Philippines, and 1,250 (6.65%) from Vietnam are the top three exporting countries for migrant fishermen in Taiwan, far exceeding the number of domestic workers of distant water fishermen. The number of fishermen from these three countries exceeds 90% of the foreign workers (Scalabrini Migration Center, 2020; Aspinwall, 2021; Yen and Liuhuang, 2021) (Table 1).

Foreign fishermen have made significant contributions to Taiwan’s DWF industry, but new problems have gradually arisen in employment, especially around the issue of fishermen’s rights, which has received great international attention. Taiwan’s principal regulations on DWF migrant fishermen employment – “Regulations on the Authorization and Management of Overseas Employment of Foreign Crew Members Regulations on the Authorization and Management of Overseas Employment of Foreign Crew Members” is based on the”Act for Distant Water Fisheries”. The purposes of the regulations are for strengthening the management of DWF, curbing “Illegal, Unreported and Unregulated Fishing” (IUU), improving the traceability of catches and fishery products, and promoting the sustainable operation of offshore fishing. The regulations of foreign fishermen employment by agencies, the conditions of establishment, the contract and management of fishermen, and the security deposit (Council of Agriculture, Taiwan, 2016; Jane, 2020), along with monthly minimum wage, insurance (accident, medical, and general death), rest periods, and medical, transportation, accommodation and other expenses incurred due to work (Executive Yuan, Taiwan, 2017; Executive Yuan, Taiwan, 2022; Council of Agriculture, Taiwan, 2022) are also managed by these regulations.1 Although it seems integral on issues related to foreign fishermen, however, according to Scalabrini Migration Center (SMC), the DWF regulations in Taiwan still need improvement, especially on migrant fisher agencies, including qualifications of intermediaries, attribution of responsibilities, roles in labor disputes, government supervision, and legal norms (Scalabrini Migration Center, 2020). On the basis of report of SAFE Seas (Safeguarding Against, And Addressing Fishers’ Exploitation at Sea)2, the cause of dispute about labor and human trafficking in the fishing industry, not only government’s legal institution and supervision system but also crew agencies management. Actually, the exploitation exist in labor condition, environment and wage, etc., and it is related to crew agencies (SAFE Seas, 2021).

According to the investigation report of the Taiwan Control Yuan, there are five significant deficiencies in the employment of foreign crews in the DWF industry. First, lack of training in leadership and communication skills; second, the incomplete legal framework of the fisheries industry and insufficient labor protection; third, insufficient interpreters to effectively assist in communication; fourth, insufficient investigative workforce and agreements, leading to labor exploitation problems; and fifth, insufficient communication mechanisms among governmental sectors. Having said that, Taiwan continues to promote and facilitate related improvements in response to the unfortunate cases involving migrant fishermen in Taiwan’s DWF, including the formulation of “Key Points of Service Quality Evaluation for Overseas Employment of Non-Taiwanese Crew Agencies” and the enactment of “Regulations on the Authorization and Management of Overseas Employment of Foreign Crew Members” (The Control Yuan, Taiwan, 2021), which shows that Taiwan is placing increasing emphasis on agency management and migrant worker recruitment.

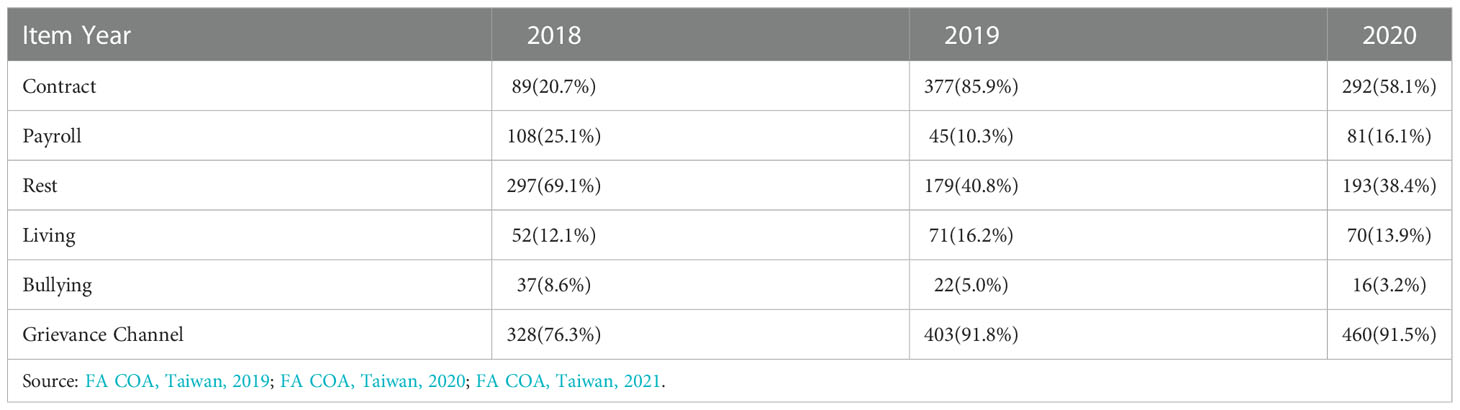

According to the “2018-2020 Right Protection and Intention investigation of Overseas Employment of Foreign Crew Members” published by Fisheries Agency in Taiwan, the main issues reported from the interviews of migrant crews in such fishing ports as Qianzhen, Xiaogang, Cijin in Kaohsiung City and Donggang, Yanpu in Pintung County are not knowing the complaint hotline, lack of rest time, not signing a contract with the shipping company or agency, not holding a contract or contracts being withheld. (FA COA, Taiwan, 2019; FA COA, Taiwan, 2020; FA COA, Taiwan, 2021) (Table 2).

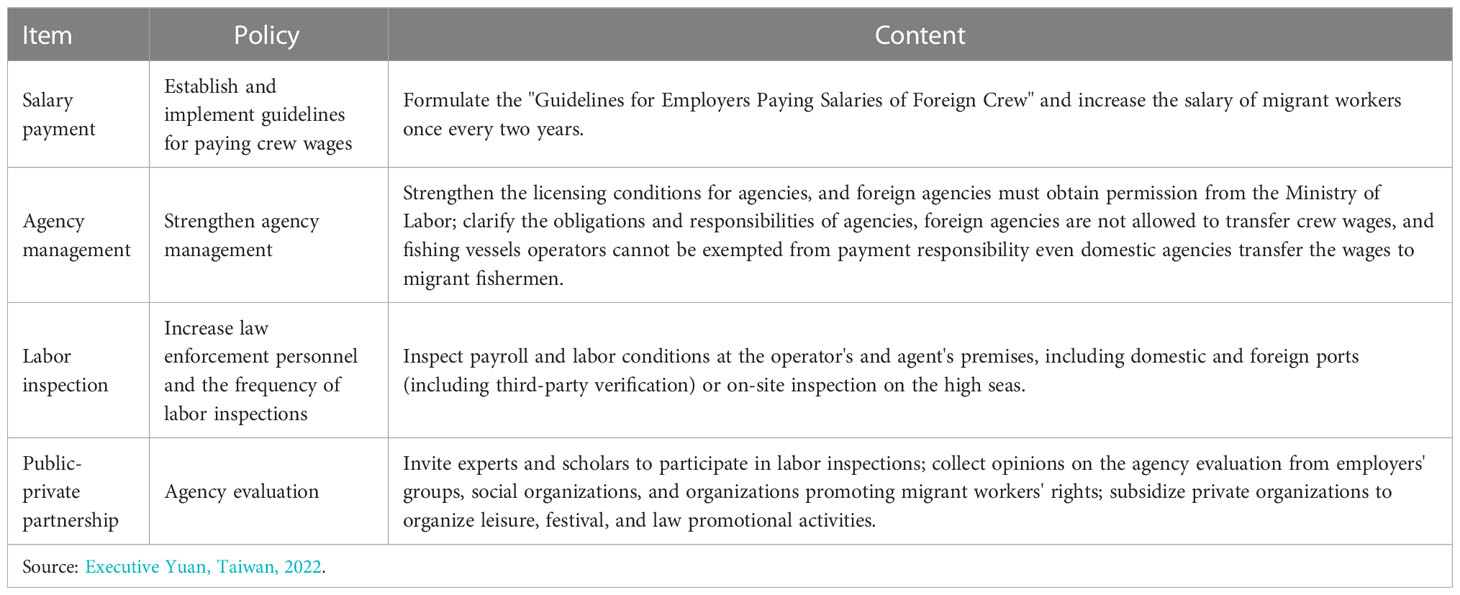

In recent years, the Taiwan government has been actively addressing the controversial issues of DWF, attempting to converge with the international community and fulfilling its international obligations. Therefore, in 2022, the Fisheries Agency enacted “Action Plan for Fisheries and Human Rights” with seven strategies covering the implementation of labor conditions, strengthening living conditions and social security, strengthening the management of agencies, monitoring the management mechanism, strengthening the management of expedient ships, establishing and deepening international cooperation, and promoting the partnership for the common good to improve the working conditions and rights of foreign fishermen (Executive Yuan, Taiwan, 2022).3 Following are agency-related sections. (Table 3):

The Work in Fishing Convention (C188) has become an essential international convention signed by many countries and gradually influenced the importing countries (such as Taiwan) and exporting countries (such as Indonesia, the Philippines, Vietnam) of fishermen as the basis for the amendment of laws and regulations related to DWF and fishermen (International Labour Organization, 2007; Simmons & Stringer, 2014; Zhou et al., 2019; Vandergeest & Marschke, 2021; Yen and Liuhuang, 2021). Although C188 enhances the system of fishermen’s working and human rights, it is somehow unclear in employment agencies, and this is why the focus on fishermen’s rights has gradually turned to agencies in recent years. However, Most of report and journal article are still focus on supervision system and legal institution, especially importing countries. But discussion of angencies is few, especially exporting countries. So it is necessary to discuss agencies of DWF migrant fishermen of exporting countries.

Therefore, this study conducts a comparative analysis of the agency management system in the major source countries of Taiwan’s DWF migrant fishermen (Indonesia, the Philippines, and Vietnam), and interviews with DWF stakeholders are also implemented, in order to improve the Taiwan government’s promotion of the agency management system, thereby promoting the development of fishermen’s rights.

2. Challenges for fishermen-exporting countries in migrant labor management

2.1. Indonesia

The central authority in charge of migrant worker agencies in Indonesia is “The National Board for the Placement and Protection of Indonesian Overseas Workers”(Badan Pelindungan Pekerja Migran Indonesia, BP2MI), and one of its policy guidelines is to protect Indonesian migrant workers, which is “to combat nonprocedural PMI delivery syndication” (Memerangi Sindikasi Pengiriman PMI Nonprosedural)(BP2MI, Indonesia).4 Thus, its two strategic goals are: (1) to enhance the protection and welfare of Indonesian migrant workers and their families; (2) to implement good governance. This policy enhances the welfare of Indonesian migrant workers and their families as national assets through the placement and protection of skilled and professional Indonesian migrant workers, and to implement efficient, effective, and accountable organizational governance. Over the past decade, Indonesia has gradually paid more attention to the rights of Indonesians working abroad, including working and human rights, especially migrant fishermen’s rights. Therefore, Indonesia has started to establish regulations to protect Indonesian fishermen working overseas, and the central regulation related to the agency is “2013 About Recruitment And Placement Of Crew”(Permenhub No. Pm.84 Tahun 2013 Tentang Perekrutan Dan Penempatan Awak Kapal).

Indonesia Ocean Justice Initiative (IOJI) held a conference on “the role of the government in the placement and protection of Indonesian migrant workers on foreign fishing vessels” in 2020 and proposed important policy guidelines and indicators. The director of BP2MI, Benny Rhamdani, and the chief executive officer of IOJI, Dr. Mas Achmad Santosa, mentioned the complaints and disputes of international fishermen in recent years; Taiwan was the country with the most complaints, accounting for more than 30% (Rhamdani, 2020).5

Most distant-water fishermen in Taiwan come from Indonesia, but they are often mistreated by low wages, long working hours, poor working conditions, poor living conditions, and physical abuse. Even worse are wage withholding and agencies’ exploitation (The Jakarta Post, 2017). Additionally, according to the report of Human Rights at Sea, many Indonesian fishermen in Taiwan are often faced with undesirable situations, such as medical errors, poor communication, unexpected changes in contracts, and deductions from paychecks, all of which are related to the inaction or malicious behavior of agencies (Chiang, 2019).

Among the complaints, wage arrears are the most common ones. The main reason is that most of the complainants are from fishermen hired by illegal processes, thus making these fishermen prone to breach of contracts and vulnerable to exploitation by employers. Furthermore, the use of Letter of Guarantee (LG) for crews of high seas voyages does not meet the Indonesian government’s requirements and regulations on labor contracts, thus losing this essential protection of fishermen. In sum, the labor disputes faced by Indonesian migrant fishermen can be summarized into six key issues: the content of labor contracts, working conditions, lack of sufficient control by government agencies, placement of employers without legal regulation mechanism, lack of comprehensive database making it challenging to handle cases immediately, and unfavorable labor contracts (Santosa, 2020). Furthermore, two of them might be attributed to the agencies: 1. The Indonesian government believes that the lack of a comprehensive national database makes it difficult to handle cases immediately, mainly the insufficient information of the domestic and overseas agencies, and crews in Indonesia; 2. Due to the unfavorable labor contract for the migrant fishermen, the agencies and the shipowners are exempted from protecting the fishermen, causing many controversies and problems. As a result, Indonesia has begun to pay closer attention to the regulation of agencies in recent years.

2.2. The Philippines

“Philippines Overseas Employment Administration”(POEA)was established in 1974 under the Labor Code of the Philippines. The original name was Overseas Employment Development Board(OEDB), then changed to its current name in 1982. The mission of POEA is to manage the export of migrant workers overseas and to protect the rights and interests of migrant workers. There are two central legal/regulatory systems for private agencies in the Philippines: “1995 Migrant Workers and Overseas Filipinos Act” and “Labor Code of the Philippines” (POEA, Philippines, 1995; DOLE, Philippines, 2017). The rules related to the overseas placement of fishermen include “Rules and Regulations Governing the Recruitment and Employment of Seafarers”, “Standard Terms and Conditions Governing the Overseas Employment of Filipino Seafarers Onboard Ocean-going Ships”, “2016 Revised POEA Rules and Regulations Governing the Recruitment and Employment of Seafarers” (POEA, Philippines, 2003; POEA, Philippines, 2010; POEA, Philippines, 2016).

However, in recent years, agencies have often exploited Filipino fishermen overseas in terms of wages, including excessive monthly payroll deductions and placement fees or job search fees to disguise high loans. This situation exists not only in Philippine agencies but also in Taiwan (Taiwan News, 2020). In fact, Filipino and Taiwanese agencies have charged various fees to Filipino fish workers, including transportation, documentation, training, and medical fees. This situation also makes it necessary for Filipino fishermen to pay certain types of fees to obtain a job, and these practices have long been in the gray area of the laws, or even illegal in the Philippines and Taiwan (Verité, 2021). Moreover, illegal agencies in the Philippines often recruit fish workers in the countryside, using deceptive and unrealistic wages, and refund of deposits to lure in cooperative Taiwanese fishing vessels. (personnel of Rerum Novarum Center, personal communication, 2021/09/02; Urbina, 2015). Therefore, the migrant worker agency is the problem that needs to be addressed urgently for the Philippine government.

Given that the economy is opening up and the number of migrant workers is increasing rapidly, the Department of Labor and Employment(DOLE)of the Philippines asserts that the government should ensure fair and ethical recruitment as the key to helping Filipinos choose to work overseas. The Philippines has been actively adopting immigration policies and frameworks for a long time. In order to further protect the rights and welfare of Filipino migrant workers, “National Action Plan to Mainstream Fair and Ethical Recruitment”(NAP-FER) plays an important role. NAP-FER is a significant commitment of the Philippines fully engaged to promote the Global Compact for Safe, Orderly, and Regular Migration (GCM) and the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) with six strategic goals: 1. formulate a reward system and strengthen the existing overseas labor recruitment registration and approval system;2. develop a code of ethical standards for overseas labor recruitment and encourage its adoption by private recruitment agencies and staffing industry associations; 3. develop and promote due diligence and self-assessment tools to enhance and simplify current policies and systems based on international fair and ethical recruitment standards;4. ongoing capacity building in fair and ethical recruitment principles and standards; 5. launch extensive informational, educational, and communicational campaigns to raise awareness of legal employment processes, illegal employment and human trafficking risks, and worker rights and responsibilities; 6. Improve existing reporting, monitoring, and remediation of Filipino migrant workers to address gaps in grievances, perceptions, and descriptions of previous mechanisms (DOLE, 2021; Leon, 2021; Noriega, 2021). From the above, it is clear that the role of Philippine agencies is highlighted during migrant worker recruitment by the government, and the international ethical standards are gradually adopted for future recruitment and incorporated into the National Action Plan to protect Filipino migrant workers overseas.

The NAP-FER follows the guideline: “Robust Legal and Policy Framework That the Philippines Already Has As One of the Top Labor-Sending or Worker-Deploying Countries Worldwide”, which has five key elements: 1. facilitate fair and ethical employment and ensure decent working conditions; 2. promote sustained, inclusive and sustainable economic growth, full and productive employment, and decent work for all; 3. reduce inequalities within and between countries; 4. protecting the rights, promoting the welfare, and increasing the opportunities of overseas Filipinos (OFs) in “Philippine Development Plan 2017-2022”; 5. National and international legal and policy frameworks such as Committee on Migrant Workers (CMW), International Labor Organization Conventions (ILO Conventions), relevant Philippine laws, and POEA regulations (Baclig, 2021).

2.3. Vietnam

The main authority in charge of the migrant worker in Vietnam is “Ministry of Labor, War Invalid and Social Affairs” (MOLISA), which was established under Vietnamese “Labor Code” with two departments dedicated to overseas labor affairs: Department of Overseas Labor(DOLAB)and the Center of Overseas Labor(COLAB) (Bộ Lao động – Thương binh và Xã hội). Vietnam’s labor export policy is based on the latest version of “Labor Code”. According to Article 4 of the Law (Government Labor Policy), there are seven major guidelines: 1. protect labor rights; 2. protect employers’ rights; 3. create job opportunities; 4. human resource development; 5. labor market development; 6. maintenance of labor relations; 7. ensuring social equity and justice.

The Labor Code of Vietnam was revised in 2019, and Article 150 of the Code, which focuses on “Vietnamese workers working overseas”, explicitly mentions that “the Government encourages enterprises, institutions, organizations and natural persons to seek and expand overseas labor markets in order to export Vietnamese workers. Vietnamese workers working abroad shall comply with the laws of Vietnam and the host country unless otherwise stipulated in international treaties to which the Socialist Republic of Vietnam is a member.” (Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Vietnam, Taiwan, 2020).

Furthermore, “Law on Vietnamese employees working abroad under employment contract”(NGƯỜI LAO ĐỘNG VIỆT NAM ĐI LÀM VIỆC Ở NƯỚC NGOÀI THEO HỢP ĐỒNG;69/2020/QH14), as the fundamental regulations for Vietnamese people working overseas, proposes five guidelines: 1. encourage the acquisition of skills overseas and bring them back to Vietnam; 2. protect the legal rights of Vietnamese workers in overseas labor contracts; 3. develop a new and safe labor market, targeting high-income industries to improve the qualifications and skills of Vietnamese workers working overseas; 4. ensure the protection for Vietnamese workers working overseas; 5. help Vietnamese workers overseas for social integration and participation in the labor market after returning home (Quốc Hội, 2020).

Although the policy focus on migrant workers of Vietnam doesn’t explicitly include agencies, agencies still play an essential role as a matchmaker when sending Vietnamese workers overseas. In addition, the government’s policy is to expect Vietnamese workers to acquire professional skills from overseas, earn foreign exchange for the country, and eventually bring them back to Vietnam to become the driving force of the country’s socio-economic development. Therefore, the role of agencies will be different from that of Indonesia and the Philippines and even more unique.

However, Vietnamese fishermen are often subjected to mistreatment, overtime work, restriction of freedom, and other treatment on Taiwanese fishing vessels, and wage disputes happen frequently (VN Express International, 2017). According to the report of Scalabrini Migration Center, many fishermen are charged high fees by agencies before going overseas. In addition to the $1,000 anti-runaway deposit, they must also pay a relocation fee (about $2,000) and other fees that are partially or fully deducted from their wages.

3. Scope of research and methodology

3.1. Comparison of the migrant fisher agency system

C188 is the current international norm and standard for protecting fishermen’s rights, and the relevant norms of agencies are mentioned in Article 22. For instance, the prohibition of recruitment and placement services from using means, mechanisms, or lists to prevent or deter fishermen from working and require no fees for recruitment or placement paid by the fisher. Therefore, this study compared the issues related to agencies mentioned in C188, including the management system, the main functions, and the recruitment system. Countries included in this study were Taiwan’s top three major source countries of migrant fishermen, namely Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam. The dimensions of comparison and the relevance to C188 are described in Table 4 (Peterson, 2005; Pickvance, 2021; Wang, 2021).

3.2. Focus group

In this study, we invited Taiwan’s DWF stakeholders, including officials from the Fisheries Agency, observers, Taiwan’s local agencies, NGOs, and fishery organizations, to conduct focus group interviews on the agency system for distant-water fishermen. According to McLafferty (2004), the focus group is appropriate for providing insights into participants’ attitudes, beliefs, and opinions on the specific issue. More than 50 agencies participated in the discussion to provide information to support the analysis of literature and regulations.

4. Comparative analysis of migrant fisher agency system in three countries

4.1. Agency management system

According to the current regulations in Indonesia, companies or institutions can undertake crew agency business with one of the three licenses, namely “Trading Business Permit” (Surat Izin Usaha Perdagangan, SIUP), “Recruitment and Placement Seafarers Agency’s License” (Surat Izin Usaha Perekrutan dan Penempatan Awak Kapal, SIUPPAK), and “License of Indonesian Migrant Workers Placement Agency” (Surat Izin Perusahaan Penempatan Pekerja Migran Indonesia, SIP3MI) (Santosa, 2020). SIUP is a business license issued by the Ministry of Trade in Indonesia, which mainly permits trading activities, including selling and leasing of commodities or services. Any company engaged in trading business must hold a SIUP (DPMPTSP Provinsi DKI JAKARTA, Indonesia; PPID, Indonesia, 2020). SIUPPAK is issued by the Ministry of Transportation in Indonesia. The Indonesian agencies with the SIUPPAK license have the largest number of cooperation with the Taiwanese agencies (personnel of Hai Sheng Human Resources, personal communication, 2021/09/17). SIUPPAK has specific crew placement affairs and a more stringent application process, which effectively enhances the cooperation and protection for the agencies in Taiwan and Indonesia (DJPL, Indonesia, 2013). Another license, SIP3MI is issued by the Ministry of Manpower in Indonesia because the original purpose was to attract cooperation and investment from foreign companies, so the requirements for the application are more stringent (Ministry of Manpower, Indonesia, 2019).

There are different authorities and conditions for establishing agencies or companies depending on their licenses. Currently, The number of agencies with SIUPPAK is the highest because of the lower entry barrier and more regulations. By contrast, SIP3MI was issued in 2018; although it contains the government’s good intentions, the threshold is too high (especially in deposits, paid-in capital, three-year plans, and commitments.), so it is not in the mainstream. Currently, three types of business licenses are allowed to undertake the agency business for Indonesian fishermen to work overseas: SIUP, SIUPPAK, and SIP3MI. Among them, the first two handle agency business and yet also are enaged in other business. In the meantime, the Indonesian migrant labor placement agency takes care of agency business only. That is the difference in essence. (personnel of Hai Sheng Human Resources, personal communication, 2021/09/17) (Table 5).

The business license of an agency in the Philippines is mainly issued by Philippine Overseas Employment Administration (POEA). In addition to the primary conditions (such as the proportion of Filipino shares and capital), the application requires the agency to provide a financial statement and proof of business capability. The four requirements for business capability are: 1. Special Power of Attorney signed by the Philippine Foreign Mission; 2. Official quota agreement confirmed by the Philippine Foreign Mission; 3. list of requirements for at least 50 crew members for new overseas jobs; 4. The new job offer should be verified by the Philippine Embassy or the Philippine Overseas Labor Office closest to the job location (POEA, Philippines, 2016). Therefore, although the Philippine government has few regulations on agency licensing, it has included expectations for the business capabilities of agencies in the application conditions.

The agency management in Vietnam is more stringent and mainly consists of officially recognized non-profit organizations, such as the Vietnam Overseas Labor Center (COLAB) and university internship institutions, to facilitate monitoring and managing overseas workers. (Trung Tâm Lao Động Ngoài Nước, 2020). However, there are also labor dispatch companies that provide agency services, and the business licenses of these companies are issued by the Office of Overseas Labour (DOLAB) (Bộ Lao Động, Thương Binh Và Xã Hội, 2007; Chính, 2007).

According to the sections on private agencies in C188, each country should have a competent authority and set standards for issuing licenses to effectively manage private agencies. It is obvious that differences exist in norms and regulations between Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam, and each country has its own advantages and problems. The licensing system in Indonesia is diversified, but this situation also reveals that the Indonesian management system has the overlapping responsibilities of departments. In addition, the SIUPPAK license currently in mainstream usage is not the SIP3MI that is being promoted in Indonesia. In the future, it may be necessary to integrate the authority and responsibility of the local government sectors and enhance a collaborative mechanism for future development. As for the Philippines, the government is engaged in facilitating the policy practice of migrant workers, and the system and authority for issuing licenses is more centralized in POEA, making management more efficient. Besides, the agencies must have a certain number of overseas job offers to meet the application criteria for the business permit, which also effectively promotes the Philippine agency as an important driver of the migrant worker policy. In Vietnam, although the country has a business license system, it is mainly operated by official institutions or non-profit organizations. Private agencies exist as labor dispatch companies and DOLAB is responsible for issuing business licenses. In summary, although Indonesia currently has many regulations, there is still confusion in regulations, authorities, and business licenses. In the Philippines, the policy is clear, and the role of agencies is clearly defined to support the national policy. In Vietnam, the licensing of migrant worker agency is led by relevant government sectors.

4.2. Main functions of agency

The main 13 functions of agencies in Indonesia are exhibited in the regulation of”2013 About Recruitment And Placement Of Crew”(Permenhub No. Pm.84 Tahun 2013 Tentang Perekrutan Dan Penempatan Awak Kapal): (1) licensing, (2) organization, (3) professionals in related fields, (4) management responsibilities of the agency business, (5) crew selection system, (6) report of the accommodated crews and their knowledge and skills development plan, (7) supervision and management of the employed crews, (8) verification, internal audit and management evaluation, (9) emergency response, (10) dispute analysis report, (11) submission of crew complaints and handling procedures, (12) establishment of health, medical, welfare, and social security system, (13) other related document processing. Additionally, the regulation also emphasizes that the functions and tasks of agencies should be assigned under the legal norms with clear context to protect the rights and interests of Indonesian migrant workers overseas, such as assisting in contract renewal at sea, assisting in remittance obligations, assisting in mortality affairs, signing collective labor agreements with unions, and assisting in allowance payment for high-risk areas. Among them, in terms of the obligation to assist in remittance, the agency is obliged to pay late fees, wages, bonuses, etc. in accordance with the contents of the crew work agreement (DJPL, 2013).

In the Philippines, according to regulations, agencies have 12 major functions: (1) provide fishermen with recruitment information, such as process, work contracts, and conditions; (2) ensure that fishermen apply for jobs with qualification documents; (3) ensure that labor contracts are in accordance with the national standard labor contract; (4) ensure that fishermen understand their rights and obligations under the labor contract before or during employment; (5) ensure that fishing workers conduct pre- and post-contract inspection; (6) submit the insurance certificate; (7) bear the responsibilities arising from the license; (8) share with the employer the responsibility and compensation arising from the labor contract, such as wages, death and disability compensation, and repatriation; (9) guarantee compliance with relevant domestic and international regulations; (10) take full responsibility for the agencies’ business practices; (11) dispatch at least 50 crew members (including fishermen) to work within one year of issuing the license; (12) repatriate overseas fishing workers when necessary (POEA, Philippines, 2016).

In Vietnam, the main institutions in charge of overseas worker agency are DOLAB and COLAB, herein their operations are described below, respectively. The main tasks of DOLAB include research and planning, evaluation and licensing of agencies, management of labor dispatch institutions (such as associations, organizations and NGOs), assistance in signing overseas labor contracts, staff training, protection of overseas workers’ rights and interests, and management of overseas workers’ income. The main tasks of COLAB include recruitment, training skills, and dispatching Vietnamese workers to work or learn overseas under contracts. Besides, understanding the relevant laws and regulations of countries where Vietnamese people work overseas is also an important task of COLAB (Ban Quản Lý Lao Động, 2020). It is clear that the Vietnamese government attaches great importance to the problems that may arise from the legal system of various countries, and intends to reduce the disputes through the mastery of laws and regulations.

The agency should take good care of the crew, but bad agencies often cause harm to the crew, and more likely to indirectly cause harm to the shipowner, such as fraudulent documents like passports, and recruitment of unqualified crew members. Therefore, fishermen-exporting countries highly value the management regulations of agencies as the basis for the functionality and positioning of agencies (personnel of Taiwan Tuna Longline Association, personal communication, 2021/10/04). According to the aforementioned functions of agencies in Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam, in addition to the basic functions of assisting labor contracts, recruitment, protecting labor rights and interests, and insurance, it is obvious that each country has their own focus differing from other countries. In Indonesia, agencies are responsible for dispute resolution assistance, and also need to assist overseas workers in remittance and incorporate related terms and conditions into contracts. Thus, it is discernible that the Indonesian government believes that agencies should make efforts in assisting overseas workers. However, Indonesian fishermen often have disputes over the payment of wages due from Indonesian agencies, such as multiple handling fees, non-payment of money, and the closure of the agencies. Although the Indonesian government has given agencies the function of assisting in remittances, many disputes still arise (personnel of PCTSFSC, personal communication, 2021/09/28). In the Philippines, the government believes that many of the responsibilities of the agency should be shared with the employer, so there are considerable regulations in the recruitment process. Moreover, in addition to reducing unnecessary disputes in correspondence with domestic and international regulations, the agency also serves the function of finding jobs overseas to facilitate the long-term national policy of promoting overseas jobs and earning foreign exchange. As for Vietnam, the dual-track execution of DOLAB and COLAB is the main feature while both institutions have the task of personnel training. The most unique function of DOLAB is to manage the income earned by overseas workers, and that of COLAB is to learn about the laws and regulations of the country where Vietnamese work overseas to reduce legal disputes. So, it can be seen that the Vietnamese government monitors the wages of overseas workers, and while actively sending its citizens to work overseas, it is hoped that they can work and learn on the basis of the understanding of laws and regulations in working countries, so that they can bring overseas technology and experience back to Vietnam to promote local economic development. In sum, Indonesia, the Philippines and Vietnam have very different perceptions on the functions and roles of agencies, and the differences in regulations between the countries are significant as a result.

4.3. Recruitment system of agency

In Indonesia, there are four approaches to recruit fishermen working on fishing vessels: through shipowners, fishing vessel operators, agencies, and independent crews. According to the regulations, in order to work on a foreign-flagged fishing vessel, an agency must meet the following requirements: According to the regulations, if a fisherman is going to work on a fishing vessel, the agency must meet the following requirements: (1) complete the registration with the competent authority, (2) hold the business license issued by the labor department, (3) join the Association of Fishing Vessel Crew Agents(asosiasi Agen Awak Kapal Perikanan), (4) have a labor contract approved by the flag state and the Indonesian official overseas institutions, (5) have a collective labor agreement, (6) have a system of internships, and (7) have standard operating procedures for the placement of fishing vessel crew (DJPL, 2013). As for the documents that fishermen need to provide, the SIUPPAK, which is the mainstream in Taiwan’s overseas employment, requires crew certificate, skill certificate, sea labor contract signed by both parties (in triplicate), consent form of family members and seafarer skills school for the maritime work (DJPL, Indonesia, 2013). Nevertheless, Indonesia’s literacy rate and government promotion are insufficient, which have resulted in many Indonesian fishermen not knowing the contract specifications even though they have signed the contract according to the law, which is one of the causes of future problems. (personnel of Bureau Veritas, personal communication, 2021/09/27).

In the Philippines, the role of fishing workers is defined under the “The Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines”. It is described in the constitution that “The State affirms labor as a primary social economic force. It shall protect the rights of workers and promote their welfare.”; “Provide appropriate legal measures for the protection of human rights of all persons within the Philippines, as well as Filipinos residing abroad, and provide for preventive measures and legal aid services to the underprivileged whose human rights have been violated or need protection”; “The State shall protect the rights of subsistence fishermen, especially of local communities, to the preferential use of local marine and fishing resources, both inland and offshore” (Constitutional Commission, Philippines, 1986). Fishermen are not only an important socio-economic force for the Philippine government, but they also need to be actively protected as a Filipino citizen, and their labor conditions need to be protected as well. Therefore, fishermen in the Philippines are positioned like crew members, and most of the laws and regulations related to fishermen in the Philippines are directly applicable to crew members. Whereas the Philippine government is more proactive in protecting Filipinos working abroad and has clearer information, Filipino fishermen also have a better understanding of the rights and obligations in the contract(personnel of Bureau Veritas, personal communication, 2021/09/27).

For complete disclosure of recruitment information to ensure labor rights, advertisements for the fishermen recruitment of Philippine agencies should explicitly mention: (1) Name, address, and POEA license number of the agency, (2) type of vessel and registration information, (3) required competencies, skills, and knowledge qualifications, (4) number of job vacancies (POEA, Philippines, 2015).6 In terms of agency fees, the Philippines offers considerable protection for fishermen. Philippine agencies can claim placement fees from overseas migrant workers in accordance with the law, but not from seafarers while fishermen are seafarers, and should not be charged placement fees according to POEA rules 2014 and “2016 Revised POEA Rules and Regulations Governing the Recruitment and Employment of Seafarers” (POEA, Philippines, 2014; POEA, Philippines, 2016). Additionally, “2016 Revised POEA Rules and Regulations Governing the Recruitment and Employment of Seafarers”requires that the competent authorities should publish guidelines to facilitate the registration of non-conventional positions or professionals with special qualifications on board like fishermen, and they are all classified as C3.7 In other words, the Philippine government guarantees job rights of those who do not meet the minimum requirements for crew registration, have limited maritime experience or training, and are placed by a licensed agency to work on DTF vessels. Plus, according to the regulations of C3, fishermen are recognized as crew members but are not required to submit training and certification documents (PSO, Philippines, 2016). Moreover, “Safety of Life at Sea (SOLAS) Course as Part of Registration Requirements”describes that life skills and life rafts are the only requirement for fishermen, and the maritime life skills for fishermen are merely based on Basic Safety Training (BST) under the STCW (STCW, Philippines, 2018).

In Vietnam, the COLAB is mainly in charge of fishermen recruitment by the cooperation with fishermen-importing countries, such as Korean and Taiwan.

The cooperation between Vietnam and Korea is based on the Korean Employment Permit System (EPS) (Kim, 2015; Trung Tâm Lao Động Ngoài Nước, 2020). According to the EPS, working in Korea includes nine major processes (1) learning Korean, (2) taking a Korean language test, (3) applying for registration, (4) being selected by a Korean company and signing a labor contract, (5) signing a dispatch Korea work contract with an overseas labor center, (6) making a deposit at a social policy bank, (7) going to work in Korea after attending a necessary knowledge training course, (8) returning to Korea on time after fulfilling the labor contract, and (9) terminating the dispatch Korea work contract and settling the escrow account. (Trung Tâm Lao Động Ngoài Nước, 2020). So, for migrant fishermen in Korea, working in Korea requires not only a certain level of Korean language proficiency, but fishermen must also pay the required fees in advance before going abroad and, more importantly, making a deposit at local social policy bank is compulsory.

The cooperation between Vietnam and Korea is based on the 2015 “Businesses operating in the service of sending workers to work abroad”(Kính gửi: Các doanh nghiệp hoạt động dịch vụ đưa người lao động đi làm việc ở nước ngoài). The requirements for agency include: 1. There must be operational procedures for dispatching workers overseas, as well as professional knowledge training when going to work in Taiwan; 2. there should be training facilities, such as classrooms or dormitories for more than 100 people; 3. At least four qualified and experienced trainers (one for skill, two for Chinese language, and one for knowledge). As for fishermen, the age must be 20 to 40 years old, live on the coast and have sea fishing experience, attend training courses in Chinese language and knowledge as required. The main conditions in the contract include: (1) contract period, (2) minimum wage, (3) board and lodging paid by employer, (4) employer-paid airfare at least, (5) working hours are in accordance with Taiwan regulations. Furthermore, costs for fishermen to work overseas regulated in the contract consist of total employee costs (service fees, agency fees; training, airfare, visas, and medical exams) and performance bond of $1,000 (Bộ Lao Động – Thương Binh Và Xã Hội, 2015).

There are significant differences between countries in the recruitment systems of an agency. In Indonesia, the agency recruitment is only one of the four recruitment channels, and SIUPPAK is the mainstream among the three agency business licenses, including the internship system and the standard operating procedures for placement of fishing vessel crew. Moreover, the recruitment process requires the consent of the family members and the specialized skills school for the offshore work, which exhibits Indonesia’s requirement for fishermen to have technical skills. And the agencies mainly assist the government to ensure skills training. In the Philippines, fishermen are constitutionally protected, while the government requires agents not to charge fishermen agency fees. Besides, whereas local fishermen do not have a high level of knowledge but have basic fishing skills, so the government provides preferential treatment for obtaining the C3 certificate. Since the fishermen only need to undergo basic safety training and have life skills and life raft operation capability, it can be seen that the Philippine government highlights the rights of fishermen. As for Vietnam, since the agency is mainly official and the private sectors have shifted to the dispatch function, the agency mainly focuses on the cooperation between countries, which can be seen in the aforementioned development of Vietnam in response to the adjustment of national laws and regulations. Additionally, the Vietnamese government has a deposit system for workers going overseas, which can be used not only to compensate for losses caused to fishermen, but also to maintain the stability of local workers when they work overseas, which will help them return to their home country after completing their skills learning. The recruitment process also varies from country to country depending on the management system and functionality. Among the three cases of this study, although Vietnam has the sound regulatory system, there are still different cooperation projects with different countries

5. Discussion

It is not easy to make congruence of law and institution in every countries. However, it could promte and improve human right of DWF migrant fishermen by some ways to influence agencies management. The discussion is below.

5.1. ILO should expand the part of agencies management in C188 to promote the protection of DWF migrant fishermen

The C188 Convention attempts to supplement the protections provided by the C179 and C181 Conventions to private agencies and fishermen, but it merely explains partially without clear practices or guiding principles. Thus, it cannot provide an international reference for the agencies worldwide, which results in significant differences in agency systems for each country and deriving the current issue of fishermen’s rights. Therefore, for Taiwan, pursuit and compliance with the spirit of the C188 Convention should be only the first step(Greenpeace, personal communication, 2021/09/14). Fundamentally, the C188 Convention should expand its guiding principles to serve as a reference for national legal norms of agencies.

5.2. Training mechanism’s standardization and inrernationalization could further to protect DWF migrant fishermen’s safety and human right

The training mechanism of agencies varies from country to country, resulting in great disparity in the skills and qualities of fishermen. Therefore, the fishermen- importing country should construct a functional training mechanism to facilitate the consistency of fishermen training in various countries, and cooperate with agencies to jointly improve the overall quality of fishermen, and at the same time, also enhance the safety and self-help ability of fishermen at work(personnel of Taiwan Tuna Longline Association, personal communication, 2021/10/04; personnel of Taiwan Tuna Association, personal communication, 2021/09/29; personnel of Rerum Novarum Center, personal communication, 2021/09/02).

5.3. It is necessary to connect exporting and importing countries of DWF migrant fishermen in agencies management to ensure the protection of human right

Whether the ILO will provide clearer regulations or guidelines for the management of agencies, fishermen-exporting countries still have different expectations or roles for agencies. Therefore, the real issue that should be taken seriously is how to connect the legal regulations of the fishermen-importing countries with those of the exporting countries, and whether the agents have fulfilled their responsibilities and obligations. For Taiwan, the government should understand the laws and regulations of the exporting countries, realize the functions of agency, and conduct due diligence on the agencies. Thus, it is feasible for the Taiwanese government to implement the management of the agencies, connect with international laws and policies, and to protect fishermen’s rights when revising laws or formulating policies for the migrant fishermen agencies (Bureau Veritas, personal communication, 2021/09/27).

5.4. Improving transparency of payment flow of angencies might be a good way to reduce disputes

For instance, the Indonesian government believes that the agency should assist the overseas fishermen to remit money back to their hometown, because Indonesia is the largest archipelago country in the world, with difficult transportation connections and poor infrastructure in rural areas. Nevertheless, the Taiwan government proposed”Action Plan for Fisheries and Human Rights” in 2022, which restricted salary transfer assistance for overseas agencies and is inconsistent with Indonesian regulations. Hence, in order to effectively resolve the most frequently occurring wage disputes. cross-national collaboration should be carried out against illegal or non-compliant migrant fishermen agencies, and even develop fishermen’s export and import project plans for different countries. Possible implementations include improving the transparency of salary remittances, reducing layer-by-layer transfers, and paying cash directly(personnel of PCTSFSC, personal communication, 2021/09/28; personnel of Bureau Veritas, personal communication,2021/09/27).

6. Conclusion

Inorder to promote human right of DWF migrant fishermen in Taiwan, it is necessary to understand the agencies management. The agencies always play the key role to connect importing and exporting countries of DWF migrant fishermen. And people find agencies might be the one of main causes to infringing upon human rights of DWF migrant fishermen. However, ILO C188 is still not to deal with agencies management yet. In the light of this, we decide to be based on the agencies management in importing country (Taiwan) to discuss and compare the agencies’ management system、main functions and recruitment system of exporting countries (Indonesia, the phillipines, and Vietnam).

The results showed that the differences in the policies of exporting fishermen or laborers among countries mainly include the management of the agencies, the training mechanism of the recruitment process, and the functions of the agencies. Although every country has made great efforts in protecting its people’s rights when the latter are working overseas, and also are devoted to following the C188, in reality, it is observed that every country holds a particular expectation of the special role that the agencies should play. For instance, the Indonesian government stresses particularly the agency’s role of transferring salaries back to their remote hometown. The Philippine government actively makes international links, and by asking the agencies to understand related regulations, the government helps to reduce disputes and in the meantime encourages the agencies to look for overseas job opportunities so that the country’s labor export policy can be followed. The Vietnamese government expects nationals to return home with the skills and capital after working overseas, in order to to promote local economic development; therefore, the government manages overseas income and realizes the differences in legal regulations between countries to reduce unnecessary disputes.

For fishermen-importing countries like Taiwan, the spirit of the C188 Convention should be followed, but not restricted to the Convention texts, and the laws and policies should be amended or formulated with the goal of promoting international human rights protection. The feasible practices include proactively establishing an agency management mechanism and collaboration platform with fishermen-exporting countries, and indirectly improving the agency’s protection of fishermen’s rights from the employers’ side. In conclusion, Taiwan as a major DWF country, should actively seize opportunities to lead the protection of fishermen’s human rights in the world, thereby implementing global obligations to achieve SDGs.

Data availability statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Ethics statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent from the participants was not required to participate in this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author contributions

The authors confirm contribution to the paper as follows: study conception and design: W-HL and P-CH. data collection: C-CL. analysis and interpretation of results: P-CH, W-HL, and C-CL. draft manuscript preparation: P-CH and H-CL. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding

Council of Agriculture-1.3.1-1.1-033

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Footnotes

- ^ In 2022, the monthly minimum wage has risen to 550 US dollars from 450 US dollars. Please refer to “Action Plan for Fisheries and Human Rights in 2022” (Council of Agriculture, Taiwan, 2022).

- ^ Safeguarding Against, And Addressing Fishers’ Exploitation at Sea is a project of Plan International and with funding from the U.S. Department of Labor. It is working to reduce forced labor and human trafficking in the fishing industry in Indonesia and the Philippines (SAFE Seas, 2022).

- ^ In response to the issue of forced labor in the 2020 U.S. Department of Labor's "Child Labor and Forced Labor Goods List", the Fisheries Administration made, revised and enacted the policy and law to comply with the spirit of the C188 Convention, such as "Regulations for the Issuance of Building Permit and Fishing Licenses", “Action Plan for Fisheries and Human Rights” , "Standard Operating Procedures for Acceptance, Notification and Handling of Disputed Information on Disputed Information of My Country's Overseas Employed Non-Chinese Crewmen for Suspected Violation of the Human Trafficking Prevention and Control Law", "Services of Overseas Employment of Non-Chinese Crew Agencies" “Key Points of Quality Evaluation", "Principles of Review of Living Care Service Plans for Overseas Employment of Non-Chinese Seamen", "Management Rules for Fishing Vessels", etc. (Liu, 2021; Council of Agriculture, Taiwan, 2022).

- ^ PMI is the abbreviation of “Pekerja Migran Indonesia” in Indonesian. it means “Indonesian Migrant Workers” in English.

- ^ The first three nations that received most complaints are Taiwan, Sourth Korea, and Peur (Rhamdani, 2020)。

- ^ As a matter of fact, the Philippines PIEA also works with other countires, such as the cooperation with Taiwan on recruitment. Please refer to: (POEA, Philippines, 2015; POEA, Philippines, 2016)

- ^ After one year of holding the licence, it is allowed to apply for C2. Please refer to: (PSO, Philippines, 2016)

References

Aspinwall N. (2021). Taiwan Ordered to Address Forced Labor on Its Fishing Vessels. (Washington, D.C., USA: The Diplomat). Available at: https://thediplomat.com/2021/05/taiwan-ordered-to-address-forced-labor-on-its-fishing-vessels/.

Bộ Lao động – Thương binh và Xã hội. Available at: http://www.molisa.gov.vn/Pages/trangchu.aspx.

Bộ Lao Động, Thương Binh Và Xã Hội (2007) Hướng Dẫn chi Tiết Một Số Điều Của Luật Người lao Động Việt nam Đi làm Việc Ở Nước ngoài Theo Hợp Đồng và Nghị Định Số 126/2007/Nđ-cp ngày 01 tháng 08 năm 2007 Của chính Phủ quy Định chi Tiết và Hướng Dẫn Một Số Điều Của Luật Người lao Động Việt nam Đi làm Việc Ở Nước ngoài Theo Hợp Đồng. Thư Viện pháp Luật. Available at: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Lao-dong-Tien-luong/Thong-tu-21-2007-TT-BLDTBXH-huong-dan-Luat-Nghi-dinh-126-2007-ND-CP-nguoi-lao-dong-Viet-Nam-lam-viec-nuoc-ngoai-hop-dong-56607.asp.

Bộ Lao Động – Thương Binh Và Xã Hội (2015)Các doanh nghiệp hoạt động dịch vụ đưa người lao động đi làm việc ở nước ngoài. Thư Viện pháp Luật. In: . Available at: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/cong-van/Lao-dong-Tien-luong/Cong-van-2176-LDTBXH-QLLDNN-2015-dua-lao-dong-sang-Dai-Loan-lam-viec-277365.aspx.

Bộ Lao động – Thương binh và Xã hội (2017) Về việc quy định chức năng, nhiệm vụ và cơ cấu tổ chức của trung tâm lao động ngoài nước. Bộ lao động – Thương binh và xã hội. Available at: http://molisa.gov.vn/Pages/gioithieu/cocautochucchitiet.aspx?ToChucID=1476.

Baclig C. E. (2021). National action plan emerging vs illegal recruitment. (Philippines: Inquirer.Net.). Available at: https://newsinfo.inquirer.net/1513990/national-action-plan-emerging-vs-illegal-recruitment.

Ban Quản Lý Lao Động (2020) Góp ý Dự án Luật Người lao động Việt nam đi làm việc ở nước ngoài theo hợp đồng (sửa đổi). văn phòng kinh Tế - văn hoá Việt nam Tại Đài Bắc (trụ sở chính). Available at: http://www.vecolabor.org.tw/vecovn/news.php?extend.7.1.

BP2MI Indonesia Website. Available at: https://www.bp2mi.go.id/.

Chiang M. (2019). Labour disputes reveal a worrying power imbalance and vulnerability of migrant fishermen in Taiwan's fishing industry. (UK: Human Rights at Sea). Available at: https://safety4sea.com/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/HRAS-Indonesian-crew-disputes-Taiwan-Case-Study-2019_12.pdf.

Chính P. (2007). Quy Định chi Tiết và Hướng Dẫn thi hành Một Số Điều Của Luật Người lao Động Việt nam Đi làm Việc Ở Nước ngoài Theo Hợp Đồng (Vietnam: Thư Viện pháp Luật). Available at: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/Lao-dong-Tien-luong/Nghi-dinh-126-2007-ND-CP-huong-dan-Luat-Nguoi-lao-dong-Viet-Nam-di-lam-viec-o-nuoc-ngoai-theo-hop-dong-54142.aspx.

Constitutional Commission, Philippines (1986) The constitution of the republic of the philippines. official gazette. Available at: https://www.officialgazette.gov.ph/constitutions/1987-constitution/.

Council of Agriculture, Taiwan (2016) Act for distant water fisheries. laws & regulations database of the republic of China (Taiwan). Available at: https://law.moj.gov.tw/ENG/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=M0050051.

Council of Agriculture, Taiwan (2022) Regulations on the authorization and management of overseas employment of foreign crew members. laws & regulations database of the republic of China (Taiwan). Available at: https://law.moj.gov.tw/LawClass/LawAll.aspx?pcode=M0050061.

DJPL, Indonesia (2013). “Permenhub No. Pm.84 Tahun 2013 Tentang Perekrutan Dan Penempatan Awak Kapal,” Direktorat Jenderal Pengangkutan Laut. Available at: https://hubla.dephub.go.id/home/page/regulation/read/6685/peraturan-menteri-perhubungan-nomor-pm-84-tahun-2013.

DOLE, Philippines (2017). Labor Code of the Philippines (Philippines: DOLE). Available at: https://www.dole.gov.ph/php_assets/uploads/2017/11/LaborCodeofthePhilippines20171.pdf.

DOLE, Philippines (2021). Fewer cases of OFW abuse with ethical recruitment action plan – Bello. (Philippines: DOLE). Available at: https://www.dole.gov.ph/news/fewer-cases-of-ofw-abuse-with-ethical-recruitment-action-plan-bello/.

DPMPTSP Provinsi DKI JAKARTA, Indonesia (n.d). Detail perizinan: Surat izin usaha perdagangan (SIUP) kecil perorangan baru (Provinsi DKI Jakarta: Dinas PM & PTSP). Available at: https://pelayanan.jakarta.go.id/site/detailperizinan/571.

Executive Yuan, Taiwan (2017). Template of labor contract between operator and overseas employment of non-Taiwanese seafarers. The Executive Yuan Gazette, 23 (22). Available at: http://www.rootlaw.com.tw/Attach/L-Doc/A040270061045100-1060203-1000-001.pdf.

Executive Yuan, Taiwan (2022). Action Plan for Fisheries and Human Rights. (Taipei: EY). Available at: https://www.ey.gov.tw/Page/448DE008087A1971/0ac73b25-1520-42ad-a5b9-a38ba39852a0.

FA COA, Taiwan (2019). 2018 right protection and intention investigation of overseas employment of foreign crew members (Taipei: COA).

FA COA, Taiwan (2020). 2019 right protection and intention investigation of overseas employment of foreign crew members (Taipei: COA).

FA COA, Taiwan (2021). 2020 right protection and intention investigation of overseas employment of foreign crew members (Taipei: COA).

International Labour Organization (2007). C188 - work in fishing convention 2007 (No. 188) (Switzerland: International Labour Organization). Available at: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/normlex/en/f?p=NORMLEXPUB:12100:0::NO::P12100_ILO_CODE:C188.

Jane W. J. (2020). Exploring the impact of deep Sea fishing regulations and policies (OAC-SHU-109-013) (Kaohsiung, Taiwan: OAC). Available at: https://www.oac.gov.tw/filedownload?file=subsidy/202101111608340.pdf&filedisplay=%E6%B5%B7%E6%B4%8B%E5%A7%94%E5%93%A1%E6%9C%83%E6%AD%A3%E5%BC%8F%E5%A0%B1%E5%91%8A.pdf&flag=doc.

Kim M. J. (2015). The Republic of Korea's Employment Permit System (EPS): Background and Rapid Assessment. International Migration Papers No. 119 (Switzerland: International Labour Organization). Available at: https://www.ilo.org/wcmsp5/groups/public/@ed_protect/@protrav/@migrant/documents/publication/wcms_344235.pdf.

Leon S. D. (2021). Drop in OFW abuse seen with recruitment action plan -bello (Philippines: PIA). Available at: https://pia.gov.ph/news/2021/11/15/drop-in-ofw-abuse-seen-with-recruitment-action-plan-bello.

Liu W. H. (2021). “Improvement of distant fishery human activation and evaluation of sustainable development of fishing village labor environment,” in Agriculture regeneration project, final report (Taipei: Council of Agriculture).

McLafferty I. (2004). Focus group interviews as a data collecting strategy. J. Adv. Nurs. 48 (2), 187–194. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2004.03186.x

Ministry of Manpower, Indonesia (2019). Procedures for issuance of license of Indonesian migrant workers placement agency,” (Indonesia: Ministry of Manpower). Available at: https://peraturan.go.id/common/dokumen/terjemah/2019/Lembaran%20Lepas%20Nomor%2010%20Tahun%202019%20(final%2011%20September%202019).pdf.

Noriega R. (2021). Bello: Fewer OFW abuse cases recorded after ethical recruitment plan adopted. (Philippines: GMA NEWS). Available at: https://www.gmanetwork.com/news/pinoyabroad/dispatch/810571/bello-fewer-ofw-abuse-cases-recorded-after-ethical-recruitment-plan-adopted/story/.

Peterson R. A. (2005). Problems in comparative research: The example of omnivorousness. (Netherlands: POETICS) 33, 257–282.

Pickvance C. G. (2021). Four varieties of comparative analysis. J. Hous. Built Environ. 16, 7–28. doi: 10.1023/A:1011533211521

POEA, Philippines (1995). Migrant Workers Act of 1995 (RA 8042) (Philippines: POEA). Available at: https://www.google.com/search?q=1995+Migrant+Workers+and+Overseas+Filipinos+Act&rlz=1C1ONGR_zh-TWTW973TW973&oq=1995+Migrant+Workers+and+Overseas+Filipinos+Act&aqs=chrome.69i57.240j0j4&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8.

POEA, Philippines (2003). POEA Rules and Regulations Governing the Recruitment and Employment of Seafarers (Philippines: POEA). Available at: https://www.ilo.org/dyn/natlex/docs/ELECTRONIC/77696/82590/F577650201/PHL77696.pdf.

POEA, Philippines (2010). Standard Terms and Conditions Governing the Overseas Employment of Filipino Seafarers On-Board Ocean-Going Ships (Philippines: POEA). Available at: https://www.poea.gov.ph/memorandumcirculars/2010/10.pdf.

POEA, Philippines (2014). “Fishermen are seafarers and should not be charged placement fee,” in POEA rules (Philippines: POEA). Available at: https://www.dmw.gov.ph/archives/news/2014/05-6.pdf.

POEA, Philippines (2015). Special hiring program for Taiwan (Philippines: POEA). Available at: https://www.dmw.gov.ph/archives/shpt/shpt.html.

POEA, Philippines (2016). 2016 Revised POEA Rules and Regulations Governing the Recruitment and Employment of Seafarers (Philippines: POEA). Available at: https://asean.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/08/2016-Rules-Seabased.pdf.

PPID, Indonesia (2020). Cara Mendapatkan Surat Izin Usaha Perdagangan (SIUP). (Indonesia: Pejabat Pengelola Informasi dan Dokumentasi). Available at: https://ppid.semarangkota.go.id/cara-mendapatkan-surat-izin-usaha-perdagangan-siup/.

PSO, Philippines (2016). Registration of SRC applicants (Philippines: POEA). Available at: https://www.dmw.gov.ph/archives/services/workers/registration_src.pdf.

Quốc Hội (2020). Người lao Động Việt nam Đi làm Việc Ở Nước ngoài Theo Hợp Đồng. (Vietnam: Thư Viện pháp Luật). Available at: https://thuvienphapluat.vn/van-ban/lao-dong-tien-luong/luat-69-2020-qh14-nguoi-lao-dong-viet-nam-lam-viec-o-nuoc-ngoai-theo-hop-dong-2020-439844.aspx?v=d.

Rhamdani B. (2020).Peran Pemerintah Dalam Penempatan Dan Pelindungan Pekerja Migran Indonesia Di Kapal Ikan Asing. (Indonesia: Melayani Dan Melindungi Dengan Nurani). Available at: https://kkp.go.id/an-component/media/upload-gambar-pendukung/DitJaskel/publikasi-materi-2/pekerja-migran/BAHAN%20KA%20BP2MI%20WEBINAR%20PELINDUNGAN%20ABK%20DI%20KAPAL%20ASING.pdf.

SAFE seas website. Available at: https://www.planusa.org/projects/indonesia-philippines-safeguarding-against-addressing-fishers-exploitation-at-sea/.

SAFE Seas (2021) Safe Fishing Alliance: Protecting Fishers from Forced Labor and Human Trafficking. SAFE seas. Available at: https://planusa-org-staging.s3.amazonaws.com/public/uploads/2021/06/Safe-Fishing-Alliance-Tech-Brief.pdf.

Santosa M. A. (2020) Keynote speech – badan pelindungan pekerja migran Indonesia (BP2MI). presented at peran pemerintah dalam penempatan Dan perlindungan pekerja migran Indonesia di kapal ikan asing, Jakarta, 14 mei. Available at: https://kkp.go.id/an-component/media/upload-gambar-pendukung/DitJaskel/publikasi-materi-2/pekerja-migran/Keynote%20Speech%20Webinar_Pelindungan%20ABK%20Indonesia%20di%20Kapal%20Ikan%20Asing_Indo%20Ocean%20Justice%20Initiative_14%20Mei%202020.pdf.

Scalabrini Migration Center (2020). Out at Sea, out of sight: Filipino, Indonesian and Vietnamese fishermen on Taiwanese fishing vessels (Quezon City: SMC). Available at: http://smc.org.ph/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/OUT-AT-SEA-OUT-OF-SIGHT.pdf.

Simmons G., Stringer C. (2014). New Zealand׳ s fisheries management system: forced labour an ignored or overlooked dimension? Mar. Policy 50, 74–80. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2014.05.013

STCW, Philippines (2018). List of Approved Maritime Training Institution Offering Refresher Courses On ATFF, PSCRB, and PFRB. STCW. Available at: https://stcw.marina.gov.ph/list-of-approved-maritime-training-institution-offering-refresher-courses-on-atff-pscrb-and-pfrb/.

Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Vietnam, Taiwan (2020). The labor code 2019 (Vietnam) (Taiwan: Taipei Economic and Cultural Office in Vietnam). Available at: https://www.roc-taiwan.org/uploads/sites/96/2020/12/2019%E5%B9%B4%E8%B6%8A%E5%8D%97%E5%8B%9E%E5%8B%95%E6%B3%95%E5%85%A8%E6%96%87%E4%B8%AD%E8%AD%AF%E6%9C%80%E7%B5%82%E7%89%88%E5%90%AB2%E9%99%84%E9%8C%84-%E5%B7%B2%E4%BF%9D%E5%85%A8.pdf.

Taiwan News (2020). Taiwan-Based Filipino fishermen accuse brokers of ‘overcharging (Taipei: Taiwan News). Available at: https://www.taiwannews.com.tw/en/news/3964698.

The ASEAN Post (2019). Is the fish you eat caught by “Slaves?” (Malaysia: The ASEAN Post). Available at: https://theaseanpost.com/article/fish-you-eat-caught-slaves.

The Control Yuan, Taiwan (2021) Investigation report of the control Yuan, no. 110-0005. the control Yuan. Available at: https://www.cy.gov.tw/CyBsBoxContent.aspx?n=133&s=17498.

The Jakarta Post (2017). Fishermen, including from Indonesia, ‘kept like slaves’ in Taiwan. (Indonesia: The Jakarta Post). Available at: https://www.thejakartapost.com/news/2017/09/19/-fishermen-including-from-indonesia-kept-like-slaves-in-taiwan-.html.

Thomas C. (2020). Taiwan Fishing fleet catch added to US forced labor list. (Taipei: Ketagalan Media). Available at: https://ketagalanmedia.com/2020/10/01/taiwan-fishing-fleet-catch-added-to-us-forced-labor-list/.

Trung Tâm Lao Động Ngoài Nước (2020). Quy Định, Điều Kiện tham gia Chương trình eps. (Vietnam: Trung tâm lao Động ngoài Nước). Available at: http://www.colab.gov.vn/tin-tuc/642/Cac-quy-dinh-dieu-kien-doi-voi-nguoi-lao-dong-khi-tham-gia-chuong-trinh.aspx.

Trung tâm lao động ngoài nước website. Available at: http://www.colab.gov.vn.

Urbina I. (2015). “The outlaw ocean: Tricked and indebted on land, abused or abandoned at Sea,” in The new York times. Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2015/11/09/world/asia/philippines-fishing-ships-illegal-manning-agencies.html.

Urbina I. (2022). Is the world’s deadliest profession also among the most violent? (Canada: CBC). Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/outlaw-ocean-lawless-seas-1.6595578.

Vandergeest P., Marschke M. (2021). Beyond slavery scandals: Explaining working conditions among fish workers in Taiwan and Thailand. Mar. Policy 132, 104685. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104685

Verité (2021). Recruitment and employment experiences of Filipino migrant fishers in taiwan’s tuna fishing sector: An exploratory study (MA, USA: Verité). Available at: https://verite.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/10/Verite_Recruitment-and-Employment-Experiences-of-Filipino-Migrant-Fishers-in-Taiwan-Tuna-Fishing-Sector:FINAL.pdf.

VN Express International (2017). Vietnamese Fishermen ‘Kept like slaves’ in Taiwan (Vietnam: VN Express International). Available at: https://e.vnexpress.net/news/world/vietnamese-fishermen-kept-like-slaves-in-taiwan-3644009.html.

Wang M. L. (2021). Comparative research. (Taipei: NAER). Available at: https://terms.naer.edu.tw/detail/1679273/.

Yen K. W., Liuhuang L. C. (2021). A review of migrant labour rights protection in distant water fishing in Taiwan: From laissez-faire to regulation and challenges behind. Mar. Policy 134, 104805. doi: 10.1016/j.marpol.2021.104805

Keywords: Agency System, Distant Water Fisheries, Human Rights, Migrant Fishermen, SDGs, Southeast Asia

Citation: Hung P-C, Lee H-C, Lin C-C and Liu W-H (2022) Promoting human rights for Taiwan’s fishermen: Collaboration with the primary source countries of Taiwan’s DWF migrant fishermen. Front. Mar. Sci. 9:1097378. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2022.1097378

Received: 13 November 2022; Accepted: 05 December 2022;

Published: 22 December 2022.

Edited by:

Yen-Chiang Chang, Dalian Maritime University, ChinaReviewed by:

Shih-Ming Kao, Graduate Institute of Marine Affairs, National Sun Yat-sen University, TaiwanSaru Arifin, State University of Semarang, Indonesia

Yordan Gunawan, Muhammadiyah University of Yogyakarta, Indonesia

Damir Bekyashev, Moscow State Institute of International Relations, Russia

Elyta Elyta, Tanjungpura University, Indonesia

Copyright © 2022 Hung, Lee, Lin and Liu. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Wen-Hong Liu, YW5kZXJzb25saXVAbmt1c3QuZWR1LnR3

Po-Chih Hung

Po-Chih Hung Hsiao-Chien Lee

Hsiao-Chien Lee Chih-Cheng Lin

Chih-Cheng Lin Wen-Hong Liu

Wen-Hong Liu