- 1Tsinghua University School of Law, Beijing, China

- 2The Law School (Intellectual Property College) of Jinan University, Guangzhou, China

Sea-level rise is not only causing physical damage to maritime features but also posing challenges to the law of the sea. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea lends legal significance to the relative position of the land and the sea. However, the ecological situation of maritime features and rising sea levels are changing these factors and placing the legal status of these features at risk of reclassification. This implies that islands with full rights may lose their exclusive economic zones, continental shelves, and even territorial seas due to sea-level rise. In addition to the physical enhancement of maritime features, legal solutions, as a more sustainable and affordable approach, are expected to contribute to mitigating adverse impacts of sea-level rise. However, most discussions are limited to the issue of baselines and maritime boundaries, while the legal status of maritime features has not received sufficient attention. In this paper, we examine in detail the limitations of existing laws, particularly the Convention, and present substantive and procedural options for the establishment of new rules to mitigate the effects of sea-level rise. The legal impacts of sea-level rise on maritime features can be categorized into three different aspects: dynamics of the relative position of land and sea, ecological degradation, and human interventions. It was found that the current international rules are insufficiently flexible in addressing the challenges posed by sea-level rise; thus, international law-making is therefore considered necessary. As far as the proposed rule is concerned, either legally “sustaining” the status of maritime features or allowing reclassification elicits complex issues, particularly considering the close connection between land and maritime zones under the law of the sea. Moreover, attempts to achieve new rules by applying any procedural option for international law-making in isolation may be impractical. In light of this, we explore a viable approach to the progressive development of relevant legal regimes, following the international community’s optimal consensus and shared interests.

1. Introduction

Since 1993, the global sea-level has been rising at an average rate of 3.3 millimetres per year with the large-scale melting of ice sheets caused by global warming commonly attributed as the major cause (WMO, 2020). According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), “Global sea levels are rising as a result of human-caused global warming, with recent rates being unprecedented over the past 2,500-plus years” (NASA, 2022). A joint research study conducted by British and Finnish researchers shows that the global sea-level will probably rise another metre in the next hundred years (Grinsted et al., 2010). Additionally, an Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report1 similarly suggests that sea levels may still go up by 0.9–1.3 metres during the twenty-first century despite the implementation of effective measures (IPCC, 2019). Although scientific studies are not conclusive regarding the rate of future sea-level rise, this phenomenon is certainly posing serious threats to low-lying islands, which face a future of environmental degradation as well as inundation (Wadey et al., 2017). Furthermore, sea-level rise not only poses a physical threat to those maritime features (including islands, rocks and low-tide elevations), but also constitutes international legal challenges.2

The law of the sea attaches legal significance to certain natural factors by connecting the relative position of the sea and the land as well as ecological situations of maritime features with their legal statuses. According to the United Nations Convention on the law of the sea (UNCLOS), only “a naturally formed area of land” above the high-tide line can be legally defined as an “island” that has a 12-nautical-mile territorial sea. Further, only those islands capable of sustaining “human habitation or economic life of their own” can have an exclusive economic zone of 200 nautical miles to the maximum and a continental shelf that may exceed 200 nautical miles.3 In return, the legal status of maritime features is of paramount significance to states, as it determines the geographical extent of the sovereignty,sovereign rights or jurisdiction, which are closely linked to their maritime interests.

However, sea-level rise resulting from climate change produces a series of challenges to the legal status of maritime features by altering the relative position of the sea and the land, as well as ecological situations. The International Law Commission (ILC) observes that “[T]he partial inundation of a fully entitled island owing to sea-level rise could call into question its possible reclassification from the category of a fully entitled island to that of a rock, or even a low-tide elevation, if the capacity to sustain human habitation or economic life of its own is lost.”4 It implies a possibility that the owner states of features who are potentially affected by sea-level rise, especially those small island states that rely heavily on maritime zones for achieving development, become at risk of losing vast areas that would otherwise be under their national jurisdiction.

Some aspects of these issues have been discussed over the past few years. Studies published in 1990—by both Soons and Caron—first raised the topic of the legal effects of rising sea levels (Caron, 1990; Soons, 1990). In subsequent research, a proposal to “freeze” the baseline and the outer limit of maritime zones received increasing attention and a number of procedural options were further analyzed and compared (Jesus, 2003; Hayashi, 2011; Rayfuse, 2013; Vidas, 2014; Freestone et al., 2017; Lal, 2017; Ma, 2021). The Institute of International Law (ILA) established the Committee on International Law and Sea-Level Rise. The Committee had a full discussion at the ILA’s Johannesburg Conference in 2016 and used this as the basis for an official report in 2018, which changed the position significantly from the previous one on whether the baseline should be floating (ILA, 2018). Following this, the ILC decided in 2018 to include the topic “Sea-Level Rise in Relation to International Law” in its long-term programme of work and issued some preliminary reports (ILC, 2018; ILC, 2020; ILC, 2022). In recent years, small island states that are significantly affected by sea-level rise have become increasingly vocal in their arguments against the idea that sea-level rise would diminish their established legal rights and maritime interests (PIF, 2021).

However, the focused debate on baselines and maritime zones has frequently neglected to address concerns regarding the legal status of maritime features including islands and low-tide elevations, which has led to peculiar incongruities from the perspective of the “land dominates the sea” principle, which is traditionally considered fundamental to maritime rights concerning islands as well as the mainlands (Freestone et al., 2017; Papanicolopulu, 2018). As the International Court of Justice (ICJ) plainly stated in the Qatar/Bahrain case, there are “islands … and therefore generate the same maritime rights, as other land territory.” This observation was reaffirmed in the Nicaragua/Honduras case5 that followed. In fact, only a few studies have focused on the effects of features or the legal significance of human intervention on the legal status (Yamamoto and Esteban, 2010; Kaye, 2017). Moreover, with the option being increasingly proposed that baselines and the outer limit of maritime zones should be frozen, it is necessary to answer the question of how to reconcile arrangements in international law concerning the legal status of maritime features in relation to these maritime boundaries that may be frozen. Additionally, although attempts to interpret and apply existing rules are usually quite popular among scholars in response to new legal challenges posed by climate change, this paper discusses why international law-making in relation to the law of the sea is necessary for the present context.

The paper examines the limitations of existing laws, primarily UNCLOS, and discusses how the options for international law-making in the law of the sea can be applied to mitigate the effects of sea-level rise on maritime features as well as the relevant, potentially affected maritime zones. The rest of the paper is structured as follows. Part 2 considers the blurred boundary between international law-making and legal interpretation and the need for a distinction. Part 3 discusses typical effects of sea-level rise on maritime features and, on this basis, illustrates the limitations of the current legal regime under the law of the sea. Part 4 discusses and compares the substantive and procedural options in international law-making that can be applied. Part 5 proposes a balanced approach to address the impacts of sea-level rise from the perspective of the “community” initiative6, guided by the principle of giving particular regard to small island states and low-lying coastal states.

2. International law-making in the law of the sea

In response to the legal challenges posed by sea-level rise, generally, the international community may adopt one of two different approaches: one is applying the legal interpretation, whereas the other is the development of international law. However, these two strategies are, occasionally, incorrectly conflated in current forums, which can be misleading and precipitate confusion. Therefore, before discussing which approach is more feasible or reasonable, this part of the paper attempts to clarify the exact meaning of international law-making and its boundaries in relation to legal interpretation, as well as provides a preliminary indication of the international law-making options proposed in the law of the sea.

2.1. International law-making and its boundaries with legal interpretation

As distinguished from domestic legal systems, no centralized legislative institution exists in international law that is responsible for legislation or for amending laws; however, the making, amending, and abrogating of international legal rules does occur: some otherwise non-binding rules come into force, while those that are binding, are altered (Harrison, 2008). Such a process is often referred to as “international law-making.” It is commonly accepted that the formal path of international law-making includes both customary international law and treaties. According to Philip Allott, the development of customary international law is accompanied by “the sedimentary self-ordering of a self-evolving international society” (Allott, 1999). Treaties, by contrast, create a sub-system between the states parties and, thus, produced legal effects, as well as social effects in the general legal system, which can be understood as changing the legal environment within the “international society” (Allott, 1999).

Nonetheless, in the practice of international law, the structure of international law-making is far more complex than the prescription under Article 38 of the Statute of the ICJ. In addition to state practice and their consent, express or implied, the United Nations as well as other international organizations also play an important role in creating rules of international law (Ian, 2008). Indubitably, sovereign states still remain at the center of international law-making, but the rest of the structure is not evidently unimportant. The discussion here only serves to illustrate the complex reality of international law-making; this paper does not intend to provide a lengthy consideration of the maximum or minimum definitions of international law-making. In the following paragraphs, we will only take into consideration possible options related to the mitigation of the effects of sea-level rise on maritime features.

A primary issue we must address, however, is the distinction between law-making (legislation) and legal interpretation, which is sometimes related to the distinction between the current rule and the proposed rule. In some cases, legal proposals in response to legal effects of sea-level rise confuse the two, because the boundary between them is not always clearly visible. Nevertheless, as we will discuss below, it is unacceptable in international law to ignore that rules exist, bypass treaties, or overlook the accumulation of state practice to replace the current rule with the proposed rule.

Legal interpretation as an activity that clarifies the meaning of a text is not essential in all situations. Only when the meaning of a legal text is unclear and the application of the text cannot be achieved, is it necessary to apply legal interpretation. One might ask whether it is still relevant to distinguish between the interpreting and the amending of a treaty. After all, the Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) has made separate provisions7 for both. Indeed, in an ideal situation, the formulation of a treaty by consensus would mean something different from the clarification of its texts by interpretation: the former directly alters the rights and obligations of the parties and determines the validity and meaning of a legal text, whereas the latter is merely “retroactive (or ex tunc)” and helps one recall these meanings (Schwarzenberger, 1968).

In reality, however, whether in the forum of domestic law or that of international law, the blurred boundary between the interpreting and the amending of legal documents may under some circumstances cause no less trouble for the certainty of a treaty than does the ambiguity of the text itself. Lord McNair commented in his well-known work that the interpretation of legal documents is a subject of great unease for legislators (McNair, 1961). Such unease stems not only from the uncertainty of legal interpretation but also from the tendency that legal interpretation may usurp legislative power for the following reasons.

The first and most common situation, which is popular in common law countries, is “a hybrid between interpretation and revision” based on the mandate of the legislator (Schwarzenberger, 1968). This is the case with judicial law-making that is familiar to lawyers but also often questioned. In the field of public international law, few bodies have been accorded such a status. Even the ICJ, the International Criminal Court, and the International Tribunal for the law of the sea (ITLOS) are regarded as mere interpreters in a particular case and do not have the competence to revise treaties. Second, at a moment when the legislator does not have a situation in mind when making the law, or when circumstances subsequently change, legal interpretation seems to be tacitly accepted as a proper way to fill such “hidden gaps,” as long as they remain within the “object and purpose” of the law (Alexander, 2013). Third, when neither a mandate is provided nor a situation falls within the legislator’s intention, interpreters sometimes still find it difficult to restrain their impulse to create new rights and obligations for those who are bound by the law, which in effect constitutes a revision to the law. An example is the judgement of the 2016 South China Sea Arbitration. In that case, the ICJ, in interpreting Article 13 of UNCLOS, asserted that low-tide elevation does not legally constitute “the land territory,”8 disregarding that the definition of the low-tide elevation is exactly “ a naturally formed area of land” in this legal document.

To identify the boundaries between legal interpretation and legislation and, in particular, to avoid usurpation of the legislator’s powers, some standards have been established. Long before the VCLT and any draft of the VCLT, “context,” which is the most important of these standards, had been a traditional criterion for distinguishing between legal interpretation and legislation and the idea that “interpretation must not exceed the scope of the text” was quite familiar to the legal profession (Barak, 2006). The problem with the “context” standard, however, is that not everyone has the same understanding of the text and thus the question becomes one of whose understanding prevails. A commonly accepted answer to this question would be that it is necessary to respect the legislator’s intent when they are making the law. Therefore, Article 31.1 of the VCLT prescribes, “A treaty shall be interpreted … in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given … in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.” In this sense, we have thus initially identified the boundaries of legal interpretation—the text and object and purpose it reflects—though the ambiguity is not entirely removed, which will be discussed in specific contexts in the following paragraphs.

2.2. Options for international law-making in the law of the sea

As with other parts of the broader realm of international law, the conclusion and revision of treaties and changes in customary international law are the principal means of international law-making in the law of the sea. Simultaneously, this area has some characteristics of its own. Before we embark on a specific discussion of international law-making with respect to the effects of sea-level rise on the legal status of maritime features, it is necessary to clarify these potential influencing factors, which include the “centrality” of the UNCLOS, the co-governance of multiple international institutions, and the existence of specially affected states.

First, the legal regime of the law of the sea is believed to be governed by a “constitution of the oceans,” the UNCLOS, which covers most, if not all, aspects of maritime issues; however, any attempt to start the revision process of the Convention invariably raises concerns. Technically speaking, the UNCLOS is indeed “a living treaty” (Barnes & Barrett, 2016), even leaving aside this metaphor suggesting a broad space for interpretation of the provision within such a description. Any state party to this Convention may, through the United Nations, send written notifications to other states parties requesting specific amendments to the provisions of the UNCLOS and a conference must be convened to consider those amendments when they have the support of sufficient states.9 It should be noted that such formal amendments to the UNCLOS have not been successful for 40 years and there have been few actual attempts. This may sufficiently illustrate the potential resistance and complexity to changing this agreement.

In addition to the formal amendment procedure, states parties may “amend” the provisions of the UNCLOS by consensus through the Meeting of States Parties that is held annually. In this regard, some successful precedents already exist. In 1995, the Meeting of States Parties postponed the election of the judges of the ITLOS and the election of members of the Commission on the Limits of the continental shelf by means of its decisions.1011 In the following, the Meeting of States Parties has twice adjusted the deadline in 2001 and 2008 for states to make submissions on the continental shelf, and has permitted them to provide first “a description of the status of preparation and intended date of making a submission” within the deadline instead of the full submission.12 The closest attempt may be the making of the implementing agreement on Part XI13, though none of its text mentions amendments or revisions (Vidas, 2010).

Indubitably, the UNCLOS is not the only option for initiating treaty-based law-making. States may conclude an agreement supplementary to the UNCLOS, specially addressing the problems posed by sea-level rise, or develop an independent document or protocol to other treaties, such as the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change.14

Moreover, applying the customary international law approach, states also create or alter rules of the law of the sea through conducting general practice and expressing acceptance of achieving international law-making. The development of rules of customary international law in relation to the regime of the Convention should also be carefully considered in the context of the law of the sea. Where the development of customary international law occurs in areas not covered by the UNCLOS, no “genuine conflict” exists, and the emerging norm of customary international law will apply among all states. However, when subsequent customary international law has the same substance as the existing rules of the Convention and constitutes a modification of them, there may exist a difference of opinion regarding which governs the contracting parties (Buga, 2022).

Second, a large number of international institutions including the ILC, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), the International Seabed Authority, and the Food and Agriculture Organisation (FAO) play essential roles in the international law-making process. For example, the IMO continually organizes the making and the revision of conventions related to maritime safety, the prevention of pollution of the sea by ships, the facilitation of maritime transport and the improvement of the efficiency of navigation and maritime liability in connection therewith and is responsible for the translation into law of technical standards for shipping. Since 2017, the organization has actively led discussions on the regulation of maritime autonomous surface ships. Moreover, the FAO has led forums on most levels of legal aspects of fisheries utilization and conservation. International institutions contribute to facilitating the making of international law in the law of the sea, despite this sometimes leading to the risk of fragmentation and conflicts (Harrison, 2011).

Third, states may enjoy a differentiated status in the international law-making of the law of the sea due to differences in their geographical situation. In its judgement in the North Sea continental shelf case, the ICJ, in discussing whether the equidistance principle had been transformed from a treaty rule under the 1958 Convention on the continental shelf into general international law, stated, “a very widespread and representative participation in the Convention might suffice of itself, provided it included that of States whose interests were specially affected” and the Court further confirmed that the participation of landlocked states that have no interest in this matter would not be necessary.15

The “specially affected” state doctrine has since been applied again in the Fisheries Jurisdiction case between the United Kingdom and Iceland.16 It seems to the ICJ that coastal states, which do not actually possess genuine sovereign rights over certain continental shelves and landlocked states, play different roles with regard to the development of customary international law. The state practice and acceptance in the formation of customary rules are of greater legal significance than that of states which are not specially affected by a particular matter. In the law of the sea, we find “specially affected states” on various issues, including several well-disputed subjects such as the international seabed and the oceanic islands of continental countries. Therefore, some countries are considered eligible to enjoy more power in the development of customary international law on the law of the sea if they are subject to special influences of the emerging rules.

3. International law-making when sea-level rise impacts maritime features

Having clarified the options for international law-making in the law of the sea and its boundaries vis-à-vis legal interpretation, this part further discusses the effects of sea-level rise on maritime features that have different legal statuses as well as the serious practical impacts potentially caused by sea-level rise. On this basis, we examine the flexibility (or inflexibility) of existing rules with regard to the interpretation and confirm that international law-making is necessary to address the adverse impacts of sea-level rise.

3.1. Effects of sea-level rise on maritime features

Questions regarding offshore features, such as the conditions for determining the legal status of islands and the acquisition of rights in low-tide elevation, have long been a highly debated subject in diplomatic forums and academic discussions (Symonides, 2001). The legal implications of sea-level rise add to the complexity and uncertainty surrounding the topic. From the perspective of the law of the sea regime, centered on the UNCLOS, the international law implications of sea-level rise for maritime features as well as for the maritime entitlements that are closely related, are mainly reflected in three relatively independent yet interrelated aspects.

3.1.1. Dynamics of the relative position of land and sea

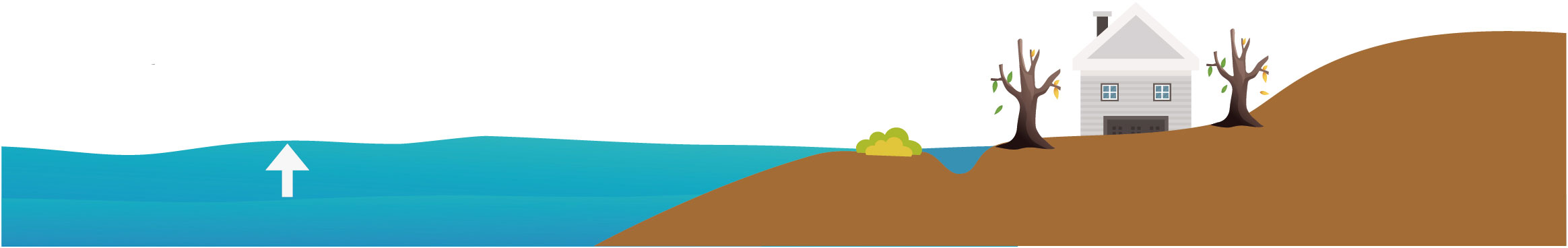

Among the international law challenges to the legal status of maritime features as a result of sea-level rise, a fairly direct observation is the legal issues arising from the change in relative position between the land and the sea (Figure 1). The law of the sea has attached great legal significance to this relative position, transforming it from a purely geographical phenomenon into an important factor in identifying the legal status of maritime features. During the Conference for the Codification of International Law, which took place from March 13 to April 12 1930, the legal definition of “island” was clarified as “any area of land surrounded by water which, except in abnormal circumstances, is permanently above high-water mark.”17 On this basis, the 1958 Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone and the Convention on the Continental Shelf (also 1958) added the requirement of “naturally formed” to exclude artificial islands and other artificial structures.18 Up to that time, all “naturally formed” maritime features “surrounded by water” were classified into two categories: one is “islands,” which are “above water at high tide” in normal circumstances (excluding short-term extreme conditions such as storms, typhoons, and tsunamis etc.) and the other is “a naturally formed area of land which is surrounded by and above water at low-tide but submerged at high tide,” that is, low-tide elevation.19

By 1982, the UNCLOS replaced these provisions in Articles 13 and 121.1 respectively, classifying maritime features into islands and low-tide elevations according to their temporal and spatial relationship to the high tide line. This use of the high tide line as an element identifying the legal status of maritime features suggests the possibility that, in the context of sea-level rise, an “island” that was normally above the seawater level might become submerged at high tide, or even submerged at low-tide. Thus, a maritime feature once considered to be an “island” under the law of the sea regime might, in such circumstances, be reclassified as a low-tide elevation or even as a submerged feature—a part of the continental shelf. Likewise, a low-tide elevation that was not normally inundated at low-tide is at risk of being reclassified when it is completely submerged underwater by rising sea levels.

3.1.2. Ecological degradation

The dichotomy presented in the Convention on the Territorial Sea and Contiguous Zone and the Convention on the continental shelf dichotomy between islands and low-tide elevations gave rise to further reflection on whether all islands should enjoy the same rights under the law of the sea. In discussions at the 1973 session of the United Nations Seabed Committee, the Organisation of African Unity was the first participant to point out the need to distinguish between different islands, considering factors such as size, population, and geological configuration (Nandan & Rosenne, 1995). Malta suggested that “one square kilometre” could be used as a criterion (Nandan & Rosenne, 1995). By contrast, countries such as Greece are opposed to reliance on quantitative standards and the concept of “economic life” proposed by Turkey has also been supported by a number of countries (Nandan & Rosenne, 1995). In light of these observations, the UNCLOS ultimately provides that “Rocks which cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.”20

In this case, two categories of “islands” have emerged in the law of the sea: (1) islands with full rights that generate a 200-nautical-mile exclusive economic zone21 and the continental shelf22 of more than 200 nautical miles and (2) islands with the 12-nautical-mile territorial sea only. It is therefore possible that sea-level rise may, under some circumstances, cause significant changes to islands’ capability to “sustain human habitation or economic life of their own” and turn a full-rights island into a “barren rock.”

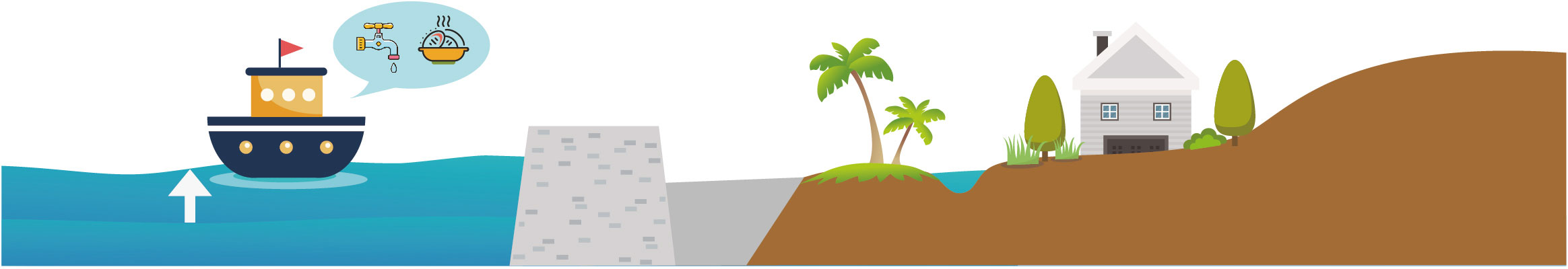

Among environmental challenges brought by sea-level rise, the commonly recognized environmental impacts include degradation of the soil and salinization of the freshwater in low-lying islands, which is likely to render otherwise habitable land unsuitable for “human habitation” and its “economic life” (see Figure 2). As mentioned, the UNCLOS has assigned great legal significance to sustain “human habitation or economic life” in identifying the category of maritime features.23 In this sense, ecological degradation brought by sea-level rise may lead to the reclassification of the legal status of maritime features. However, the UNCLOS did not consider, at the time of its conclusion, the potential degradation of the environment and living conditions of low-lying islands as a result of rising sea levels (Sefrioui, 2017). Therefore, it is unclear whether islands that once sustained human habitation and economic life can lose their position due to sea-level rise, as a feature defined by the UNCLOS that generates exclusive economic zones and continental shelves. Moreover, the incompatibility between law and reality, in this case, is all the more puzzling when considering the stringent criteria established by the arbitral tribunal in the 2014 South China Sea arbitration for “human habitation” as well as “economic life” (Kaye, 2017).

3.1.3. Human interventions

Closely related to the two issues mentioned above is the evaluation of the legal effects of human interventions24 in response to sea-level rise. For centuries, humans have taken intervention measures as a defense against seawater intrusion (Figure 3). Generally speaking, the construction of wave protection facilities, land reclamation, and even the building of artificial islands by states are generally accepted by the international community and are considered to be in accordance with the UNCLOS, although requirements and obligations, such as environmental impact assessment under Part XII, must be followed first and foremost (Soons, 2018). However, the legal question here is different. The real controversy that emerges in times of rapid sea-level rise is whether human intervention can have the legal effect of “sustaining” the legal status of a maritime feature.

On the one hand, the criterion “naturally formed” which was initially proposed by the US representative at the first United Nations Conference on the law of the sea and later adopted by the formal provisions of the UNCLOS – is important in determining the legal status of maritime features, as well as distinguishing between natural features that have the potential to create maritime entitlements, which include exclusive economic zones and continental shelves and territorial sea and artificial features that do not enjoy such rights (Nandan & Rosenne, 1995). Under this criterion, an artificial island or artificial installation built by any state in a maritime area, no matter how large or ecologically habitable, cannot generate maritime entitlements because it is not naturally formed. This then raises additional questions. Will numerous island enhancements taken in response to the significant rise in sea-level make an otherwise “naturally formed” maritime feature less natural, especially when it would have been submerged without human intervention. Or furthermore, will human intervention eventually transform it into an entirely “artificial island” as defined in Articles 60 and 80 of the Convention, and thus lose the maritime zone it once had?

On the other hand, Article 121.3 of the UNCLOS provides that maritime features which are incapable of sustaining human habitation and economic life on their own do not precipitate an exclusive economic zone and continental shelf25. In that case, indubitably, a maritime feature that once enjoyed full rights can still be classified as such when it must be fully dependent on external supplies of food, fresh water, and the like, thus losing the capability to provide for the living and economic activities of the inhabitants by itself. Moreover, if this is not the case, where is the boundary for such external supplies?

3.2. Limitation of the law of the sea before sea-level rise

Before discussing the international law-making required to address sea-level rise, it is necessary to examine the extensible boundaries of the current rules. In other words, the boundaries of the interpretation of the law of the sea determine whether, or to what extent, the international community requires “new rules” in taking steps to meet the legal challenges posed by rising sea levels. As a matter of fact, potential impacts of sea-level rise on maritime features were not considered by the contracting parties to the UNCLOS during the negotiation process and therefore this important document does not explicitly provide for this issue, leading to the legal challenges in controversy (Caron, 1990). It is worth emphasizing that, in attempting to achieve the objective through the “interpretation and application” of the law of the sea—whether by sustaining or reclassifying (which we will discuss later)—the constraints of the object and purpose of the UNCLOS must be considered.

First, Article 31(1) of the VCLT provides that a treaty “shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose.” When examining the text of the UNCLOS in relation to the status of features, we find that Articles 13 and 121 only provide “static” rules related to identifying what rights a state can claim on the basis of a maritime feature with certain geographical characteristics, but do not indicate reclassification of the legal status of a maritime feature that is experiencing a dramatic sea-level rise. From the context of the Convention, the provisions relating to the straight baseline of a delta are sometimes considered relevant to the issue. Article 7(2) of the UNCLOS prescribes,

Where because of the presence of a delta and other natural conditions the coastline is highly unstable, the appropriate points may be selected along the furthest seaward extent of the low-water line and, notwithstanding subsequent regression of the low-water line, the straight baselines shall remain effective until changed by the coastal State in accordance with this Convention.

Although this provision reflects the possibility of the temporary maintenance of rights in the case of a change in the relative position of land and sea, it does not answer the question of whether such maintenance can be considered a general rule and whether its effect is “permanent.” Moreover, the scope of application of the provision is strictly limited to scenarios where the baseline of a delta moves seaward and is excessively remote from the international law status of maritime features. Generally, the “context,” as mentioned by VCLT, of the UNCLOS does not sufficiently aid in clarifying the issue.

Second, in terms of the object and purpose of the treaty, both during the conclusion of the treaties on the law of the sea and at the Meeting of States Parties to the UNCLOS, it is commonly understood that the negotiations revolved around the identification of the international law status of maritime features all the time, but did not include reclassification of the legal status. In other words, the possible scenario that the legal status of a maritime feature could change with geographical dynamics was not considered at the time. While in international law it is feasible to fill “hidden gaps” in the development of facts contemplated by the contracting parties through speculating on what the contracting parties “would have known,” such a presumption cannot be open-ended. Although interpretation and the amending of a legal document may seem difficult to identify in numerous cases, “inevitable uncertainty” is not a proper excuse for blurring this boundary (Schwarzenberger, 1968). It is necessary to consider whether the legal nature of the facts in question fully deviates from the “object and purpose” of the legal text. For example, if a provision is intended to establish the protection of all marine animals and a species of marine animal subsequently emerges, the “hidden gap” here can be filled by including the new species. By contrast, the emergence of new species of marine plants would clearly not fall into this category and could only be dealt with by going beyond the text and constructing special or general rules.

Articles 121 and 13 of the UNCLOS only refer to the constituent elements of the legal status of maritime features and the content of rights and do not purport to agree on the legal effects of geographical changes on the legal status of any maritime feature. It is clear that the determination of legal status in the first place and the reclassification of the legal status would not be considered as one and the same under both international and national law and that the rules applicable to both are often quite different, for instance, the acquisition and loss of statehood in international law and the rules of acquisition and extinction of rights in rem in domestic law. It follows, then, that mere legal interpretation may not be sufficient to respond satisfactorily to issues of international law concerning sea-level rise in relation to maritime features.

Finally, in the context of dramatic sea-level rise, neither the conclusion that the legal status of maritime features shall be sustained, nor the conclusion that the status of maritime status shall be reclassified is likely to be established as persuasive if they rely solely on the interpretation of the UNCLOS. The former ignores that Articles 121 and 13 of the UNCLOS, neither textually nor in terms of the purpose of the treaty, do not deal with the reality of changes in the legal status of maritime features and overextend the normative content of the provisions of the UNCLOS, applying them mechanically to entirely different matters and misinterpreting the law. Moreover, the latter would mix treaty interpretation with international law-making and become a kind of attempt to “create something out of nothing” in the UNCLOS. This approach emphasizes that the relevant provisions of the UNCLOS26 should be interpreted in a manner consistent with the contractual purpose of equitable distribution of the benefits of the seas and the sustainment of the maritime order; the maintenance of existing rights of states is the option that better serves that purpose. However, it is unclear whether a necessary linkage exists between the stability of the legal status of maritime features and justice or order, and whether, as a product of national compromise, all UNCLOS provisions point to the same purpose or function.

Overall, the interpretation of the law must be limited by the true meaning of the contracting parties; otherwise, it would enter the realm of “international law-making.” As parties to the UNCLOS have no intention of agreeing on the rules governing the reclassification of the legal status of maritime features, naturally, no “qualified” object is available for such “interpretation.” In this sense, it is no longer an inquiry or clarification of the meaning of the texts but rather an attempt to create new normative content under the guise of interpretation, changing the relationship of rights and obligations between states. Treaty interpretation alone has failed to demonstrate its ability to respond to current legal challenges; instead, it is likely to unconsciously exceed the boundaries of treaty interpretation and fall into the realm of treaty revision. Therefore, in this case, we can only rely on international law-making in relation to new rules to cope with the potential effects of sea-level rise on maritime features.

4. Substantive and procedural options regarding new rules

As clarified above, to address the legal challenges caused by the dramatic sea-level rise, the international community is left with few choices but to seek new rules beyond the UNCLOS and the customs that have long existed. This part will discuss two different paths proposed for dealing with the substantive aspects of the legal effects of sea-level rise and analyze available procedural options regarding new rules.

4.1. Divided approaches to the legal status of maritime features: Reclassify or sustain?

4.1.1. Reclassifying the legal status of maritime features

The UNCLOS lays out three different categories of maritime features, including islands with full rights, islands without exclusive economic zones, and continental shelves and low-tide elevations that normally do not give rise to maritime zones. Therefore, from the perspective of some authors, it is almost intuitive to reclassify the legal status of maritime features once sea-level rise changes the geographical situation of these features. The following discussion will illustrate such a viewpoint from four aspects.

First, it was accepted in early discussions of this issue that the legal status of a maritime feature is determined by its geography under the UNCLOS, despite the fact that a coastal state is legally permitted to take measures to enhance or support the affected maritime feature (Yamamoto & Esteban, 2010). This means that only the current geographical situation of a maritime feature has legal significance, and therefore, the legal status of this feature shall be reclassified when sea-level rise changes the relevant situation physically or ecologically. In the 2007 Nicaragua v. Honduras case, the ICJ, on the basis of the common understanding of the parties, provided that the maritime feature, which had historically been exposed above the sea, no longer enjoyed island status after it had become submerged at high tide due to forces of nature.27 The Court observed,

In response to a question put by Judge ad hoc Gaja to the Parties in the course of the oral proceedings as to whether these cays would qualify as islands within the meaning of Article 121, paragraph 1, of UNCLOS, the Parties have stated that Media Luna Cay is now submerged and thus that it is no longer an island.28

The Court at least indicated that it did not oppose the viewpoint that islands may be “degraded” by rising sea levels or eventually lose their legal status as “an area of land” (Stephens & Bell, 2015). The ILC did not explicitly respond to this question in its 2020 report, but some of its statements are intriguing, as seen in the following statement:

The partial permanent inundation and/or its reclassification as a rock (as defined by Article 121, paragraph 3, of the United Nations Convention on the law of the sea) or a low-tide elevation, or the full permanent inundation (disappearance) of an island may result in the decision to no longer consider that island as a relevant or special circumstance in this phase of the application of the maritime delimitation method mentioned above.29

David D. Caron also pointed out in his earlier research that if a state’s territory, of course including maritime features, is submerged, it ceases to be “land” and becomes part of the sea, and therefore, no maritime area can be claimed on that basis (Caron, 1990). Chinese scholar Bao Yinan concludes that the jurisprudence of the ICJ and scholarly writings support the standing that “sea-level rise has a degrading effect on the natural properties of maritime features” (Bao, 2016).

Second, islands with full rights are at risk of being reclassified as “barren rocks”, as they are no longer capable of sustaining human habitation or economic livelihood (Kaye, 2017). In this regard, ILC observed,

The partial inundation of a fully entitled island owing to sea-level rise could call into question its possible reclassification from the category of a fully entitled island to that of a rock or even a low-tide elevation if the capacity to sustain human habitation or economic life of its own is lost.30

However, the ILC also expressed concern about the potential consequences of those islands being reclassified as “rocks” because “such consequences could be economically, socially and culturally catastrophic” and “natural resources of the exclusive economic zone constitute a major livelihood source for many small islands developing States, which was also a key factor that influenced the historical development of the exclusive economic zone”.31 In this sense, the view of the ILC appears to be that it is necessary for the direct inferences based on the text to be revised in some way.

Third, in recognition of potential reclassification, the extent to which human intervention can prevent maritime features from being legally “degraded” is inconclusive. There is little question as to whether states are allowed under international law, subject to obligations such as environmental assessment or due regard for affected states, to enhance the coastline of their territory, including maritime features, or to provide external supplies to those suffering from dramatic sea-level rise. How these human interventions can, after all, legally prevent the reclassification of maritime features when their geographical conditions have been altered by rising seawater is a separate issue, however.

In the South China Sea arbitration, the arbitral tribunal was dismissive of the legal significance of the state practice of human intervention in relation to the enhancement of maritime features. The tribunal went quite far in its interpretation of Article 121(3).32 In its view, “the requirement in Article 121(3) that the feature itself sustain human habitation or economic life clearly excludes a dependence on external supply.” Therefore, a maritime feature that can only sustain human habitation through the continuous delivery of supplies from the outside does not meet such requirements. Simultaneously, if the economic activity on a maritime feature depends entirely on external support or if it is carried out without the participation of the local population, for example, by utilizing a feature as a subject for mineral extraction, then this so-called economic activity does not constitute economic life under the provision.33 However, in the context of sea-level rise, large-scale human interventions are likely to result in these features being unable to sustain human habitation or economic life completely “of their own.” Applying a strict standard of interpretation to “of their own,” then, neither the coastal enhancement of maritime features that should have been submerged by the sea through human intervention nor the continuation of human habitation and economic life may exhibit the desired effect at the legal level for coastal states.

Finally, the question turns more complicated when we connect “reclassification theory” with the heated debate regarding baselines and the outer limits of maritime zones affected by sea-level rise. The legal status of maritime features, as a fundamental issue, is generally not considered when discussing the impact of and response to sea-level rise in maritime areas. Currently, the viewpoint of a significant number of states and international law scholars is that baselines and maritime zones should be “frozen” to preserve the interests of coastal states, particularly small island states. In this case, the approach of reclassifying a maritime feature in response to sea-level rise elicits discord to some extent.

It is understood that a fundamental principle in the law of the sea is “land dominates the sea.” Sovereignty over maritime features is the source of maritime entitlements according to the law of the sea. Thus, some people may view it as peculiar to see maritime zones under coastal states’ jurisdiction separated from the land. According to the UNCLOS, maritime features “cannot sustain human habitation or economic life of their own shall have no exclusive economic zone or continental shelf.” When baselines and the outer limits of maritime zones are frozen, it is possible to see a barren rock, a low-tide elevation or even a completely submerged feature allowing vast areas of the ocean to be brought under the jurisdiction of the coastal state.

Such problems may become more pronounced in areas where maritime zones are not well established, including disputed maritime areas as well as undelimited maritime areas. Assuming that a disputed island capable of sustaining human habitation or economic life becomes a barren rock as a result of sea-level rise over a period of time, it is, on the one hand, unclear whether this maritime feature should be considered a fully entitled island as it formerly was, after the parties to the dispute resolve their sovereignty dispute and proceed to delineate and it is, on the other hand, troublesome as to where the baselines should be determined due to the retreating coastline. In short, the coexistence between frozen maritime entitlements and the dynamic status of features may create some confusion in the law of the sea, especially when the “land dominates the sea” principle still dominates.

4.1.2. Sustaining the legal status of maritime features

In contrast to the opinion above, which could be called the “reclassification approach,” in the context of global sea-level rise, some scholars consider “sustaining” a principle of international law in addressing this issue, especially when considering the concern of the UNCLOS for the interests of coastal states. Currently, a number of coastal states have made clear claims to “defend” their interests against sea-level rise under international law. The Pacific Island states, for example, have jointly affirmed that their existing rights will not be legally diminished in any way by sea-level rise and that coastal states are not required to adopt unreasonable measures to retain what is rightfully theirs according to the UNCLOS (PIF, 2021). The continued assertion by small island states in recent years to maintain their established rights through declarations and actions has never been explicitly opposed by others.34 Rather, the calls of small island states have received widespread sympathy and empathy from the international community. In this context, legal solutions in response are being proposed, which may raise some new questions as well.

On the one hand, José Luís Jesus has said that in the face of the unprecedented challenges of sea-level rise in modern society, the legal rights of states that are potentially affected need to be “frozen” to maintain the equilibrium of the UNCLOS in the distribution of benefits among contracting parties (Jesus, 2003). To cope with the legal effects of sea-level rise, some authors consider the rights of states “self-perpetuating” and that the existing legal status of maritime features can be sustained through the concept of a “conceptualized islands regime” (Bai, 2017). The ILC has also recognized that an island which becomes uninhabitable as a result of seawater infiltration due to rising sea levels and the consequent pollution of its freshwater supply, rather than as a result of loss of territory, is different from the case of retreating baseline. A change in baseline may only lead to a diminution of maritime rights rather than a total loss of maritime rights, whereas the consequences of the loss of an island’s legal status could be economically, socially, and culturally catastrophic.35

The jurisprudence of the South China Sea arbitration case is also quite intriguing, although the decision has been challenged on both procedural and substantive grounds (Xu, 2021). In this judgement, the tribunal, after expressing its indifference to the legal effects of human intervention, perhaps to maintain logical coherence, claimed that islands with full rights do not lose their original legal status as a result of “environmental damage” caused by human activity.36 This means that the legal status of a maritime feature cannot be altered by human intervention, and in this case, although the Court sought to prove by this reasoning that a low-tide elevation cannot be created and transformed into a “rock” and that a “rock” cannot be transformed into an island with full maritime rights as well (Abrahamson, 2020; Schofield, 2021), it is equally clear that a “rock” cannot be transformed into a low-tide elevation by “human intervention,” nor can an island be transformed into a “rock.” However, we should not forget that sea-level rise, presently, is also a commonly recognized consequence of human activity, qualifying as a certain kind of “human intervention.” If one were to follow the tribunal’s reasoning, sea-level rise could likewise not be regarded as grounds for derogation from the established rights of the coastal state. A maritime feature’s legal status should therefore be “sustained” even if it has been submerged by the sea or if ecological degradation has occurred on it.

On the other hand, it will be interesting to see how the “sustaining” approach to coping with the effects of sea-level rise and the theory of “floating baselines” and “dynamic maritime zones” come to coexist. For example, in an extreme case, when a fully entitled island can be affected by the sea-level rise to become a feature that is only above the water at low-tide, it is still recognized as an island that has a territorial sea, an economic zone, and a continental shelf starting from its low-tide line. Furthermore, if this feature is completely submerged, it is worth considering whether the highest point of the feature shall be regarded as the only “base point” as the starting point for maritime areas.

Not surprisingly, proponents of the “sustaining approach” are also largely positive regarding the legal effects of human intervention to maintain the status of a feature (Stephens and Bell, 2015). Although it is still unclear whether the legal status of submerged maritime features can be “restored” by human intervention, greater support exists for the effectiveness of human intervention in sustaining the legal status of maritime features (Song, 2009). In the same way that an artificial island does not become a “naturally formed” maritime feature, human intervention in a “naturally formed” maritime feature does not make it any less “natural” (Elferink, 2012). The ILC has also expressed a clear preference on this issue, namely the need for the relative stability of rights relating to maritime features, as this does not imply adding new rights but rather only the maintenance of existing rights and helps to preserve the existing balance between the rights of coastal states and those of third states.37

Last, this option against reclassification of the legal status of maritime features requires coordination with “frozen” baselines and maritime zones as well. For example, in areas where the coastline recedes within the baselines, the territory may be converted to internal waters in accordance with Article 7 of the UNCLOS. Internal waters have the same legal character as the land, but specific circumstances exist in which third-state vessels may enjoy the right of innocent passage, and some states claim sovereign immunity for warships in their internal waters. However, it remains to be seen whether these rights can be preserved in “internal waters” transformed from a part of the land territory of a state.

4.2. Legal and policy options regarding new rules

As discussed above, the contemporary law of the sea, including the UNCLOS, or “general international law” as it is referred to in the Convention’s preamble, does not contain the necessary normative content to address the challenges that sea-level rise poses to the international law status of maritime features. Whether the final decision is allowing the reclassification of maritime features or sustaining their legal statuses, the international community requires new rules to mitigate the uncertainty that sea-level rise will bring to its members. In the present context, the conclusion and revision of international instruments, as well as the development of customary law and historical rights can be regarded as three possible options. Any of these procedural options have pros and cons, as elucidated in the following paragraphs.

4.2.1. Modifying or concluding international documents

It has been suggested that the most straightforward approach to addressing the incompatibility of sea-level rise with existing rules is initiating a process of revising the UNCLOS by amending or expanding it (Hayashi, 2011).

On the one hand, states parties are entitled to regulate the issue of sea-level rise in the form of a protocol or an independent document separate from the UNCLOS. However, this step, in addition to requiring a broad consensus among states, must consider the complex interactions (Oral, 2018) that the document may have with the UNCLOS and technically avoid a continuation of interpretation difficulties resulting from the ambiguity of texts. A relatively reasonable option would be arriving at an agreement regarding the legal effects of sea-level rise on the legal status of maritime features through an instrument among a range of states that adopt a fairly consistent legal position concerning this issue (e.g., amongst small island states in the Pacific region) as a tool for addressing the gap in the UNCLOS.

On the other hand, according to the UNCLOS, any state party has the privilege to submit a request to amend the UNCLOS by either the general procedure or the simplified procedure. However, the conditions for the adoption of both these procedures are extremely demanding: the former requires the unanimous agreement of all states parties on the substance for a period of 12 months, whereas for the latter, no state can object to the choice of procedure or the substance.38 Currently, the position of a significant number of states parties on this issue is unclear, and widespread concern exists that others are using the amendment of the UNCLOS to expand their own interests (Whomersley, 2021). A Chinese author has expressed strong objections and cautioned that their government should reject “opening Pandora’s box” to revise the UNCLOS (Fu, 2014). It seems, realistically, less feasible to obtain sufficient consensus and agreement to initiate and achieve a formal amendment to the UNCLOS.39 Simultaneously, the revision of this document alone cannot directly bind non-parties outside of it, including some major maritime powers, and may cause friction between contracting states and non-contracting states owing to divergent views.

4.2.2. Developing international custom

The evidence of customary international law is based on widespread state practice and the belief that such practice is obligatory due to “the existence of a rule of law requiring it.”40 Promoting the formation of a new customary international law is sometimes considered a better way to address the legal challenges of sea-level rise (Caron, 1990). In the context of this environmental phenomenon, states can clarify their legal position on the status of maritime features and adopt practical actions consistent with it, thus developing a new rule commonly accepted by members of the international community. For example, a state can consistently maintain legislation and enforce jurisdiction over a maritime feature that is submerged at high tide due to rising sea levels, using the criteria of an “island” and “gain approval of such practice in the relevant international forums” (Hayashi, 2011).

Today, the Pacific states that potentially suffer from the adverse effects of sea-level rise lobby extensively for the international acceptance of rules to support their interests and take considerable action in doing so (Kaye, 2017). In 2010, the Pacific Islands Forum adopted the Pacific Oceanscape Framework: Advancing the Implementation of Ocean Policy common declaration, which states that the forum will work to defend the undiminished maritime rights of its members (PIF, 2010). Subsequent position papers such as the Samoa Pathway, the Palau Declaration, and the Taputapuatai Declaration on Climate Change have also pointed to varying degrees of the “sustaining” approach. Australia, New Zealand, the Federated States of Micronesia, Fiji, and the Marshall Islands have also expressed backing for this proposal.41

On August 6, 2021, the Pacific Islands Forum issued a declaration stating that equity, fairness, and justice are key legal principles underpinning the UNCLOS, that the drafters of the document did not consider the impacts of sea-level rise and that, therefore, the UNCLOS is based on the premise that coastlines and ocean features are generally considered stable when determining maritime zones. In this case, coastal states, particularly small island developing countries and low-lying countries, already rely on maritime rights under the UNCLOS to plan their own development, and their existing maritime rights and interests will not be diminished by sea-level rise (PIF, 2021). All these declarations not only emphasize the stability of maritime zones but also, in fact, express a position against the reclassification of the legal status of maritime features.

However, a “threshold” exists for the emergence of customary rules, which usually requires the accumulation of evidence of state practice and opinio juris on a large-scale, and this can take a considerable period of time.42 At least in the view of the ILC, current state practice has not yet matured into a rule of customary international law. Moritaka Hayashi notes that some islands may be submerged or subject to disputes before such a rule is ultimately formulated (Hayashi, 2011).

4.2.3 Seeking acceptance for regional customs

The draft conclusions of customary international law recognize that customary law can develop among a limited number of states and apply to themselves.43 In other words, regional customary international law is a rule of international law with a regional application provided to a particular area by the unique values shared by its member states (Forteau, 2006).

The small island countries that are desperate to maintain their rights are mostly concentrated in the Pacific and Southeast Asia, and adopting the customary regional law approach would obviate the need for them to provide evidence of extra-regional state practice and certainty. Such evidence of state practice and opinio juris in a relatively small area would be easier and would equally contribute to the regional order and stability. It should be noted, however, that regional customary international law cannot bind other states and that if some of them choose to ignore regional rules, they may act against these rules and vice versa.

5. Recommendations for addressing adverse impacts

As Louis Sohn commented in his work, in terms of the development of international law, “the states are the masters of the house” (Sohn, 1995). The rules of international law must try to keep up with the needs of “their consumers and custodians,” or they will soon be abrogated “like any prescription” (Reisman, 2006). When we consider the role that international law should play in the event of sea-level rise, it is imperative to consider the will and thoughts of the majority of members of the international community. Only then can the rules proposed by jurists be accepted and truly contribute to the stability and order of the world’s oceans. In this part, based on observations regarding the claims and actions from various parties, we present some recommendations for developing relevant rules to legally mitigate the adverse impacts of sea-level rise.

5.1. Rethinking normative stability under the dynamics of natural conditions

As discussed above, significant sea-level rise due to climate change poses challenges to the rule of law, but technically speaking, this is not due to any defects in the current legal regime. There is nothing “wrong” with the UNCLOS’s provisions on the legal status of maritime features and the boundaries of maritime zones. Legislators need not—and indeed they did not—feel guilty for not having been able to anticipate such changes in natural conditions that were neither significant nor predictable at the time of drafting the treaty. We recognize, as well, that the current rules are clear and unambiguous and therefore do not leave enough room for “legal interpretation.”

Nevertheless, it is incumbent upon international law and international lawyers not to stop here. As the ILC observed, sea-level rise places coastal states, especially low-lying island states, at risk of losing extensive maritime zones and further depriving their governments of their main assets and their people of the resources on which they depend for their livelihoods due to the degradation of maritime features. The consequences could be catastrophic, not only bankrupting numerous small island developing states but also creating large numbers of refugees. This is unacceptable for both the international community and potentially affected countries. In this context, numerous impetuses exist for initiating the process of international law-making.

First, it appears that maintaining the stability of states’ interests and taking care of the interests of potentially affected countries have started to be seen as a general principle in the case of sea-level rise. A preliminary conclusion is that the UNCLOS allows countries to strengthen their own coastlines against sea-level rise through physical measures, such as reclamation and dyking. However, coastal enhancement projects to combat sea-level rise are economically or technically unaffordable for the small island developing states that are the most affected. It is likely that they will have to sit back and watch the rising waters threaten their marine features because they cannot afford such human interventions. Under these circumstances, small island states mostly have no choice but to assert their rights through legal solutions. In recent years, coastal states, represented by the Pacific Island countries, have continuously taken the position that sea-level rise should not derogate from the rights granted to them by the UNCLOS. In other words, in these international views, the rights that have been acquired should not be legally derogated, although no concrete and feasible options have been proposed. Other states in the international community seem to recognize the legitimacy of such a claim—even though it is not consistent with the existing rules—and have not raised noteworthy objections to it. This valuable consensus has laid the foundation for international law-making in the future.

Additionally, the question of how to cope with the effects of sea-level rise is essentially related to justice in the distribution of the consequences of climate change. As some researchers have pointed out, sea-level rise is not simply a natural phenomenon but also a consequence of human activity: Greenhouse gas emissions contribute to global warming, which, in turn, triggers the melting of ice sheets. The major emitters of greenhouse gases, both historically and currently, are not the small island states that experience the greatest impact of sea-level rise. While it is admittedly difficult to establish legal causality, clearly, industrial countries have a greater moral responsibility for these consequences. Therefore, it is unreasonable and inconsistent with the notion of international justice to allow small island states to suffer from sea-level rise. Not only is it necessary for industrial countries to reach out to potentially affected countries and their people, but it is also incumbent upon the international community to embrace a rule that favours or does not harm their interests in response to the effects of a rise in sea-level.

Finally, the preamble to the UNCLOS focuses on legal order and stability, which is of some help in understanding the issue. This view, which “pure” international law scholars may find distracting, is that the order upon the law of the sea is not a mere rule of law but more a reflection of the distribution of interests among states. Indeed, the so-called certainty, universality, and consistency (Lal, 2017) in the law of the sea do not preclude changing the rules; on the contrary, the balance of interests among states can be ensured through international law-making.

Thus, it seems that the making of international law to cope with the effects of sea-level rise on maritime features is a proper choice at both the practical and the logical levels. It is consistent with the consensus of the international community and does not undermine the existing international order as well. Thereafter, we must consider a feasible “international law-making programme” in a more concrete context.

5.2. A balanced path under the “community” initiative

A global consensus recognises that sea-level rise is now posing a long-term threat to all people from countries in different ways. However, Pacific Island countries find themselves in a more urgent situation. Rising sea levels threaten to submerge entire islands, making them uninhabitable or completely inundated. Pacific Island states have made urgent appeals and struggled to maintain their coastlines (PIF, 2021). All countries should be aware, however, that the effects of sea-level rise on maritime features are not only a challenge to certain states. Instead, it is a sustainable development issue that the international community should seek to address through cooperation and solidarity in many aspects. At least on this issue, countries should be seen as a community with a shared future. In pursuing their own interests, states should take into account the legitimate concerns of other countries and promote common development.

Fortunately, the international legal system provides us with more affordable and feasible approaches to mitigating the effects of sea-level rise than the physical enhancement of the long coastline. First, to ensure certainty, fairness and justice, “permanent sovereignty over natural resources” should be emphasised as a principle. When sea-level rise begins to erode shorelines, potentially altering baselines and ocean area boundaries, these ocean areas should be “frozen” (Caron, 1990; Freestone et al., 2017; Ma, 2021), as many scholars have discussed. However, if the effects of sea-level rise are so severe that this will change the legal status of maritime features, potentially causing coastal states to lose their entire, exclusive economic zones, continental shelves, or even territorial seas, simply “freezing” the boundaries of maritime zones may not be sufficient to fully protect the interests of coastal states from loss. A more direct approach might be to legally allow coastal states to retain the original status of maritime features. This approach would have two advantages. On the one hand, the link between the land territory and the maritime zone is preserved, consistent with the principle of “land dominates the sea”. On the other hand, the coastal state is given a new option to resurface the sunken territory, that is, to restore it to its original status when the relevant capacity is available, preventing it from facing the risk of being legally considered an “artificial island”. This would allow potentially affected states enough time to plan and implement actions to address the effects of sea-level rise.

Second, in addition to identifying guidelines in principle, a number of specific issues require further discussion. Although the UNCLOS does not make the depositing or publishing of baselines or maritime zones an obligation of states, they should be encouraged to do so in order to legally protect their rights in the event of coastline instability. Conversely, in the absence of a convincing reason, a state that does not publish or deposit baselines according to the UNCLOS may be at a disadvantage in international law because there may be no evidence of the location of the “normal” coastline. Such an approach would also prevent states from expanding their maritime areas in response to sea-level rise. Concerning the “convincing reason” mentioned above, the existence of disputes over relevant sea areas or features should be taken into account. In such cases, the countries concerned often avoid unilateral declarations of baselines or maritime zones out of political consideration for maintaining the status quo in order to avoid the worsening of disputes. This is also in line with obligations under provisions of the UNCLOS44 but may lead to changes in the coastline or the legal status of the disputed features due to sea-level rise. In this regard, the parties in disagreement should be encouraged to jointly determine the location and coastline of the disputed features and to publish or properly preserve this information to address the possible adverse effects of sea-level rise.

Third and perhaps most importantly, choosing the appropriate procedural options for this issue must be thoughtfully considered at this stage. Although scholars have proposed a number of solutions to the threat posed by sea-level rise, as already discussed, they all suffer from a number of flaws, such as being impractical or taking too long. Given the urgency and complexity of the challenges, the fruit of international law-making can be achieved through a hybrid approach. Attempts to amend the UNCLOS through a formal process may not go as planned, but a supplementary agreement or resolution may be supported in the ICC’s Assembly of States Parties or other international forums. Nevertheless, we should not expect too much from this. The effects of sea-level rise on maritime features and areas are both widespread and unpredictable, and the idea of a single agreement to solve the problem once and for all is not realistic. In this sense, a more appropriate option might be to codify and develop in treaty law the principle of maintaining the rights of coastal states –including the “freezing” of maritime zones and the legal status of features. The more specific and procedural rules therein would, in turn, be subject to international/regional customary law, depending on the future practice of states. In this process, UN agencies, particularly the ILC, have an important role to play, both in drafting treaties and in facilitating the formation of consensus. In addition, adjudging states that experience sea-level rise where maritime features are particularly threatened, as specially affected states, may help enhance the significance of their practice in the identification of customary international law, although the actual meaning and effects of the doctrine are still subject to contested opinions (Heller, 2018; Yeini, 2018).

Last, the international community can contribute much more than simply promoting in-time legal solutions to mitigate the effects of sea-level rise. First, capable states are encouraged to provide funding and technology to developing low-lying countries to strengthen their fragile coastlines. This assistance should be sustainable and institutionalised. Economic and technical assistance in exchange for a commitment to marine protection could be considered a viable model. Second, it should be established as an international obligation under the UNFCCC that countries should provide the necessary land for potentially affected countries to maintain their own coastlines and facilitate the migration of their nationals when they fail to protect their territory from sea-level rise. Finally, state mergers could also be an option, although mergers for “natural” reasons have not been common throughout human history. It should be noted that among these options, retention of the status of maritime features and the maritime zone is of considerable importance. From the perspective of realist international relations theory, this would give the potentially affected states a more favourable negotiating position to truly achieve the guarantee of their interests and the rights of their nationals.

6. Conclusion

The challenges posed by sea-level rise to islands and low-lying coastal areas are intensifying as the effects of climate change become apparent. While small island states are already taking various measures to strengthen their coastlines against erosion from rising seawater and to protect their people from displacement, it is both economically and technically unsustainable to rely solely on physical measures. In this context, international law is considered an important tool for maintaining the rights of coastal states to mitigate the effects of sea-level rise. Much of the earlier discussion revolved around the effects of sea-level rise on baselines and maritime boundaries, while downplaying the topic of the legal status of marine features and often ignoring the necessary boundary between treaty interpretation and international law-making. By contrast, this paper recognizes that the legal effects of sea-level rise on the status of maritime features and the issue of maritime boundaries are two related but distinct subjects and that there is insufficient room for treaty interpretation on this issue; therefore, we need to turn to international law-making in the law of the sea.