- Department of Spatial Planning and Environment, Faculty of Spatial Sciences, University of Groningen, Groningen, Netherlands

Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) literature identifies various dimensions of integration to deal with fragmented, sectoral, and ad hoc approaches to managing various uses offshore. However, the spatial dimension of MSP has receded into the background, the dimensions of integration remain ill-defined, and there is a lack of appreciation for the institutional changes that these integration efforts induce and require. Moreover, in light of the urgency of energy transition, offshore wind farms (OWF) are often prioritized over other interests in MSP practice. This paper uses the case of the Dutch North Sea Dialogues (NSD) to explore to what extent actors during the NSD pursued formal and informal institutional change to progress the various dimensions of integration in line with the normative principles of MSP to improve spatial integration between OWF and other interests at sea. The NSD provided an, initially temporary, platform that proved key for stakeholders to pursue subsequent formal and informal institutional changes that progressed integration in MSP. While formal institutional changes were achieved during the NSD, informal institutional changes also proved fundamental in progressing various dimensions of integration. The NSD shows that incremental institutional change can be effective in progressing integration, but also shows the limits to this approach. The place-based and temporal dimensions of integration require additional attention because this is where stakeholders most notably rely on existing institutional frameworks and conflicts are most prominent.

Introduction

The limitations on space for furthering energy transition onshore are creating a push for offshore renewable energy generation, foremost by means of offshore wind farms (OWF) (Bilgili et al., 2011). However, offshore space is also limited, and particularly those areas that are currently being considered feasible for OWF (closer to the coast in more shallow water), are contested (Gusatu et al., 2020). Therefore, coordination and cooperation between various interests and stakeholders offshore is necessary to ensure a timely and balanced energy transition that is well-balanced in relation to the interests of other users of the sea. Marine Spatial Planning (MSP) was developed in many countries as a means of dealing with these spatial claims offshore (Douvere and Ehler, 2008; Qiu and Jones, 2013; Ehler, 2018; Ehler et al., 2019; Flannery et al., 2019; Quero García et al., 2019; Flannery and McAteer, 2020). As such, MSP has been important in the development of the institutional framework—the “rules of the game”—surrounding OWF and in balancing OWF in relation to other sea uses.

In the past decade, there has been a surge of literature on MSP that attribute a range of normative principles to MSP (Douvere, 2008; Portman, 2011; Flannery and Ó Cinnéide, 2012; Kidd, 2013; Qiu and Jones, 2013; Kidd and Shaw, 2014; Jones et al., 2016; Olsen et al., 2016; Smythe, 2017; Klinger et al., 2018; Gee et al., 2019; Kelly et al., 2019; Saunders et al., 2019; Smythe and McCann, 2019; Kidd et al., 2020; Spijkerboer et al., 2020; Vince and Day, 2020). Ehler (2014, 2018) categorized these principles, stating that MSP should be area-based, integrated, ecosystem-based, participatory, adaptive, and strategic. Recently, however, MSP efforts in many countries are criticized for prioritizing powerful interests, such as OWF, over other interests offshore, with MSP taking the form of “strategic sectoral planning” (Kidd and Ellis, 2012; Jones et al., 2016; Flannery and McAteer, 2020; Spijkerboer et al., 2020), and being “post-political” (Flannery et al., 2018; Tafon, 2018; Clarke and Flannery, 2019). Hence, current MSP efforts appear to have limited success in satisfying these normative principles and dealing with fragmented governance, institutions, and stakeholders.

Integration is a prominent concept in MSP literature for dealing with fragmented governance and policies offshore (Portman, 2011; Kidd, 2013; Smythe, 2017; Saunders et al., 2019; Smythe and McCann, 2019; Vince and Day, 2020). Despite the attention to integration in existing literature, this paper identifies and addresses three research gaps relating to MSP and integration: (1) the spatial dimension of MSP has receded into the background, (2) the various dimensions of integration remain ill-defined, and (3) there is a lack of appreciation for the institutional changes that these integration efforts induce and require.

First, the spatial dimension of integration appears to have receded to the background in many of the more recent publications focusing on integration and MSP. Integration can occur at multiple spatial scales (Kidd, 2007), such as the local level (e.g., within specific OWF), the national level, or the international/sea-basin level. Integration processes at these various scales affect each other (Healey, 2006). Therefore, it is striking that in existing research, space and scale often only form the context in empirical analyses of governance processes or tools that examine (specific dimensions of) integration processes. When these papers do mention specific (local) knowledge and places, it is usually related to integration of coastal communities and recreation (e.g., Gee et al., 2019; Saunders et al., 2019; Vince and Day, 2020). While these are important considerations, achieving sustainable spatial configurations of various sea-uses—what I call spatial integration—should be a key purpose of integration in MSP processes.

The second research gap is related to the observation that the term integration in the marine context remains poorly defined. As emphasized by Kelly et al. (2019), it often stays unclear what is being integrated. Existing literature that discusses integration processes often refers to various dimensions of integration, such as cross-border, policy/sector, stakeholder, knowledge, and temporal integration (Saunders et al., 2019). Moreover, while various papers dealing with integration usually include similar concepts, the applied terminology differs depending on the specific focus of the paper (e.g., Portman, 2011; Kidd, 2013; Saunders et al., 2019; Smythe and McCann, 2019; Kidd et al., 2020; Vince and Day, 2020). An example is policy/sectoral integration, where definitions often do not go beyond the relatively abstract “improving coordination between policies and sectors.” Moreover, such policy/sectoral integration is acknowledged to be closely related to, for example, stakeholder and interagency integration (Smythe and McCann, 2018), which further confuses the distinctions between these dimensions. Another example is the integration within and between governments and governmental agencies for which various terms are used [e.g., organizational (Kidd, 2013), administrative (Kidd et al., 2020), inter- and intra-agency (Vince and Day, 2020), inter- and intra-governmental (Smythe and McCann, 2019), or cross-border (Saunders et al., 2019)]. Therefore, while being useful for shedding light on integration processes, these various dimensions of integration require further clarification and direction in what should be integrated.

Third, existing MSP literature on integration is criticized for its lack of appreciation for the “complex socio-political and institutional re-ordering” that these integration efforts require (Kelly et al., 2019, p. 3). Institutions are “the rules of the game in a society or, more formally […] the humanly devised constraints that shape human interaction” (North, 1990, p. 3). Generally, a distinction is made between formal institutions such as laws, policies, and regulations, and informal institutions such as conventions, norms, and understandings (North, 1991; Ostrom, 2005; Kingston and Caballero, 2009). This paper adheres to the “embedded agency” perspective on institutions, in which institutions are seen as the structures to which actors adhere, while also acknowledging actor’s capacity to bring about institutional change (Seo and Creed, 2002; Lawrence and Suddaby, 2006; Battilana and D’Aunno, 2009). When applying such an agency-oriented institutional perspective, MSP is also about “the process of designing and redesigning the rules of the game at sea with the purpose of coordinating sea-uses within specific sea-areas” (Spijkerboer et al., 2020, p. 2). Gaining insight into integration in MSP processes, therefore, requires researchers to explore how actors in their interactions throughout MSP processes pursue formal and informal institutional changes that either progress or hamper integration processes and—by extension—spatial integration.

In response to these research gaps, this paper conceptualizes spatial integration as a key purpose of MSP processes, which brings the spatial dimension back into debates regarding integration in MSP. The various dimensions of integration processes identified in existing MSP literature (e.g., Kidd and Shaw, 2014; Saunders et al., 2019) are considered important components of MSP processes that help improve such spatial integration between OWF and other interests at sea. However, as explained above, these dimensions require further clarification. Therefore, this paper develops an analytical framework for studying spatial integration, in which the normative principles that are attributes to MSP (Ehler, 2018) are used to provide direction to the dimensions of integration. Moreover, in response to the third gap, this framework is specifically attuned to studying both the formal and informal institutional changes that actors pursue when progressing these various dimensions of integration in line with the normative principles of MSP.

This paper is based on participatory observation of the case of the Dutch North Sea Dialogues (NSD). In line with the argument above, the aim is to explore to what extent actors during the NSD pursued formal and informal institutional change to progress the various dimensions of integration in line with the normative principles of MSP to achieve spatial integration between OWF and other interests at sea. The NSD were high-level, political negotiations with the purpose of drafting a North Sea Agreement that improves the balance between various interests in the Dutch North Sea, particularly related to energy, fisheries/food, and nature. The NSD can be seen as part of the Dutch MSP process because relevant parts of the agreement must be included in the current round of revisions of the Dutch marine spatial plans and other relevant plans and regulations. The NSD is a unique case because it was organized as a platform to enable stakeholders—including the government—to explore, reflect upon and negotiate potential institutional changes. As such, it can be seen as an example of a platform, or “round table” (Olsen et al., 2014) for “meaningful participation” (Pomeroy and Douvere, 2008; Ritchie and Ellis, 2010; Gopnik et al., 2012; Kidd and Shaw, 2014; Olsen et al., 2014; Jay et al., 2016; Morf et al., 2019; Quesada-Silva et al., 2019; Santos et al., 2020; Vince and Day, 2020), where stakeholders become part of collective decision-making processes. Examples of such platforms for meaningful participation are lacking in practice (Jones et al., 2016; Twomey and O’Mahony, 2019). Therefore, insights from the case of the NSD are also useful for both scientists and practitioners interested in organizing integration processes and “meaningful participation” in MSP processes. Moreover, this paper responds to calls for more empirical research into the role of integration in MSP (Saunders et al., 2019) and contributes toward understanding the socio-political and institutional dimension of integration, particularly in relation to the debate on radical versus incremental change in marine contexts (Kelly et al., 2019).

Section “Integration and Institutional Change” further explains the main concepts and development of the analytical framework for studying spatial integration in MSP. Section “Participatory Observation for Studying the North Sea Dialogues” describes and discusses the case and methods, followed by the results in section “Institutional Change for Integration in the Dutch North Sea Dialogues.” The paper concludes by using these results to reflect on existing MSP literature and provides policy recommendations.

Integration and Institutional Change

Integration is a recurring theme in spatial planning policies and debates, both onshore (Healey, 2006; Stead and Meijers, 2009; van Geet et al., 2021) and offshore (Portman, 2011; Kidd, 2013; Smythe, 2017; Saunders et al., 2019; Smythe and McCann, 2019; Vince and Day, 2020). The term integration is often used in MSP literature to describe processes that counteract fragmentation and ad hoc policies and is associated with terms such as coordination and alignment of interests (Kelly et al., 2018, 2019). Healey (2006) emphasizes that integration from a spatial planning perspective is “not just about coordinating and aligning the spatial aspects of the policies of other sectors,” it is also about “qualities of places and principles of spatial organization” (p. 71). Specific places provide insight into possibilities and impossibilities for aligning various interests in light of local circumstances and characteristics, but these places must be seen across scales, in relation to the regional, national, and international context (Healey, 2006). Insights in various interests and their spatial distribution and interactions on various scales could provide input for the abovementioned principles of spatial organization, and provide the basis for establishing frameworks for decision-making.

This paper returns an explicitly “spatial” perspective to MSP, by positioning spatial integration as a substantive goal of MSP processes. Based on the above discussion, spatial integration is understood as a sustainable spatial configuration of sea-uses, based on the presence of frameworks for decision-making that coordinate the spatial impacts of (sectoral) policies and organize structural cooperation between stakeholders at various scales, taking into account the place-based characteristics and opportunities offered by specific locations. Spatial integration, then, does not mean that interests always need to be physically integrated [e.g., in the form of multi-use (Schupp et al., 2019)]. Instead, spatial integration means that there is a patchwork of functions and uses that can be physically integrated when beneficial, but that can also lead to conscious separation of functions when necessary, to achieve a sustainable spatial configuration of sea-uses.

In this paper, the various dimensions of integration that are discussed in MSP literature (Jones et al., 2016; Saunders et al., 2019; Vince and Day, 2020) are considered important building blocks for achieving spatial integration. In their analysis of MSP literature regarding integration Saunders et al. (2019) identify the following dimensions of integration: cross-border integration, policy/sector integration, stakeholder integration, knowledge integration, and temporal integration. However, as explained in the introduction, the distinction between these dimensions remains unclear. Healey (2006) emphasizes that integration is a relational term that can only be understood in terms of “what is to be linked or merged” (p. 68) (see also Kelly et al., 2019). This paper provides such clarification by combining the dimensions of integration with the normative principles that are attributed to MSP. These normative principles distinguish MSP from previous ad hoc and sectoral approaches (Ehler, 2014, 2018; Spijkerboer et al., 2020) and show what MSP should be:

• Area or place-based: MSP should take into account location-specific contexts and cumulative effects of activities in areas and regions (Young et al., 2007; Douvere, 2008; Ehler and Douvere, 2009; Flannery and Ó Cinnéide, 2012; Christie et al., 2014; Kyriazi et al., 2016);

• Integrated: MSP should coordinate across organizational and sectoral boundaries (Douvere, 2008; Portman, 2011; Kidd, 2013; Qiu and Jones, 2013; Kidd and Shaw, 2014; Jones et al., 2016; Olsen et al., 2016; Smythe, 2017; Klinger et al., 2018; Gee et al., 2019; Saunders et al., 2019; Smythe and McCann, 2019; Kidd et al., 2020; Vince and Day, 2020);

• Ecosystem-based: MSP should achieve sustainable use of marine ecosystems by taking into account the (cumulative) effect of various uses on the environment (Young et al., 2007; Douvere, 2008; Gilliland and Laffoley, 2008; Ehler and Douvere, 2009; Agardy et al., 2011; Flannery and Ó Cinnéide, 2012; Qiu and Jones, 2013; Zaucha, 2014; Sander, 2018; Karlsson, 2019);

• Participatory: MSP should create ownership and legitimacy by organizing “meaningful” stakeholder involvement throughout the MSP process (Pomeroy and Douvere, 2008; Ritchie and Ellis, 2010; Kidd, 2013; Jones et al., 2016; Olsen et al., 2016; Flannery et al., 2018, 2016; Smith, 2018; Smythe and McCann, 2018; Tafon, 2018; Alexander and Haward, 2019; Frazão Santos et al., 2019; Piwowarczyk et al., 2019);

• Adaptive: MSP should incorporate monitoring and evaluation to ensure learning takes place and new insights are incorporated during the planning cycle (Young et al., 2007; Douvere, 2008; Douvere and Ehler, 2011; Flannery and Ó Cinnéide, 2012; Carneiro, 2013; Collie et al., 2013; Christie et al., 2014; Kelly et al., 2014; Portman, 2015; Jones et al., 2016; Frazão Santos et al., 2019; Vince and Day, 2020); and

• Strategic: MSP should take into account future developments and needs proactively (Agardy et al., 2011; Kidd, 2013; Christie et al., 2014; Gissi et al., 2019).

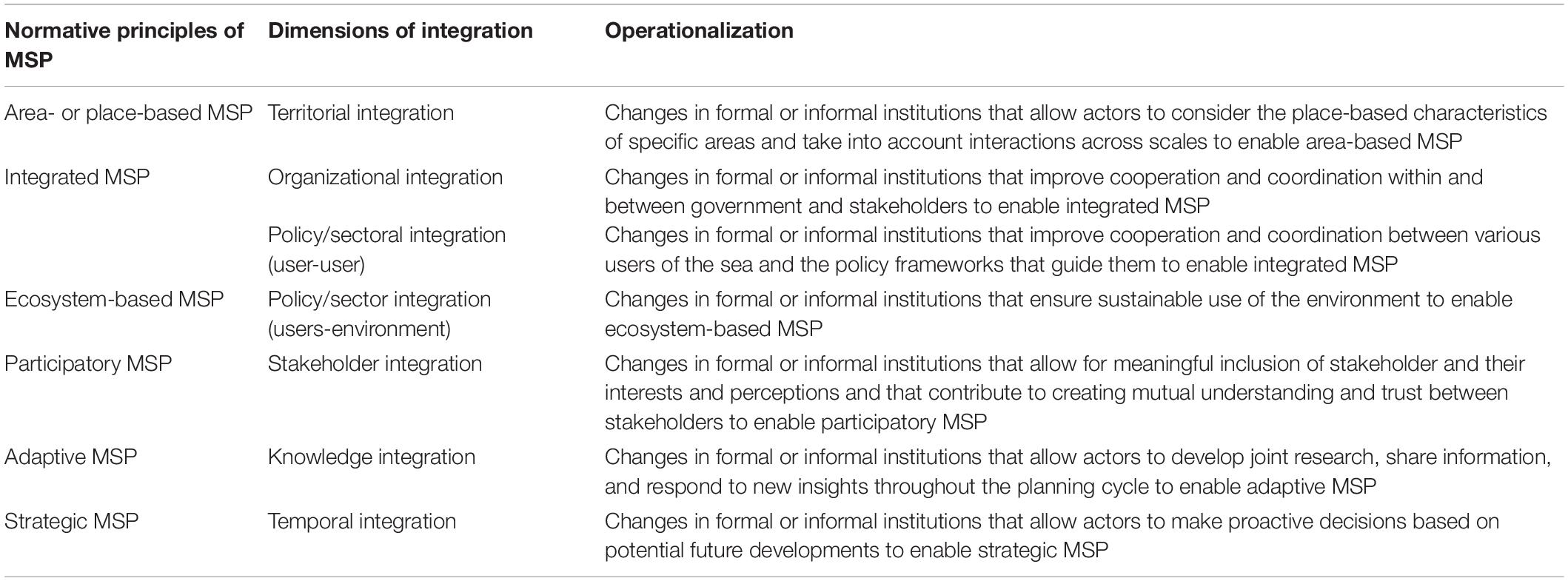

Table 1 shows how the normative principles of MSP closely match the dimensions of integration. For example, the normative principle of area-based- or place-based MSP is related to territorial integration. Territorial integration is one of the dimensions of integration referred to in existing literature on integration in MSP to refer to spatial coverage (Kidd et al., 2020) and working across (local) borders (Kidd and Shaw, 2014; Kelly et al., 2019). Existing literature often focuses solely on the cross-border or multi-scale dimensions (Gee et al., 2019; Saunders et al., 2019). Kidd and Shaw (2014) make a distinction between horizontal (adjacent areas) and vertical (between scales) territorial integration. Therefore, this paper adheres to the term territorial integration (rather than, for example, cross-border integration). Using the normative principle of area-based MSP, direction is provided to this dimension of territorial integration by focusing efforts on specific locations in relation to various scales. To further clarify and relate policy/sectoral integration to the normative principles of MSP, this article uses the distinction by Douvere (2008) between user—user, and user–environment integration. Both are seen as forms of policy/sectoral integration, but user–user integration is related to the normative goal of integrated MSP, while user-environment integration is related to the normative goal of ecosystem-based MSP. Moreover, while knowledge integration is closely related to temporal integration, the former refers to institutional changes pursued by actors that enable them to react and respond to new insights. Temporal integration, on the other hand, refers to institutional conditions that progress proactive behavior in light of uncertain future developments.

Table 1. Analytical framework for studying spatial integration in MSP by examining formal and informal institutional changes pursued by actors to progress various dimensions of integration in line with the normative principles of MSP.

The institutional dimension of integration is key in the operationalization of the analytical framework for this paper in Table 1. Paradoxically, integration efforts are often hampered by the very problems they aim to solve: namely, fragmented formal and informal institutions that guide the various sectors, policy communities, and stakeholders (Jones et al., 2016; Kelly et al., 2018, 2019). Moreover, sometimes there are no existing rules because MSP is still a relatively new endeavor and new ideas for using offshore space continue to emerge (Frazão Santos et al., 2019). Progressing spatial integration, therefore, requires institutional change aimed at “co-aligning the policies of diverse policy communities, each with their own traditions, pressures and innovation dynamics” (Healey, 2006, p. 71).

This paper will focus on the forms of institutional change pursued by actors to progress integration in line with the principles of MSP, using the commonly made distinction between formal and informal institutions (North, 1991; Ostrom, 2005; Kingston and Caballero, 2009). Formal institutional change refers to changes in laws, policies, or regulations, while informal institutional change refers to changes in conventions, norms, and codes of conduct (North, 1991; Ostrom, 2005; Kingston and Caballero, 2009). Using this distinction, the analytical framework in Table 1 can be used to explore to what extent the actors, during their interaction in the context of the NSD, pursued formal and informal institutional change to progress the various dimensions of integration in line with the normative principles of MSP.

Moreover, by using the distinction between formal and informal change, this study also contributes to the debate in MSP literature on more radical versus incremental change. Recently, authors have argued for more radical change in formal institutional arrangements to achieve fundamental transformations in marine governance (Clarke and Flannery, 2019; Kelly et al., 2018, 2019). Maintaining and adding to the existing system will result in problems due to path dependency, policy layering, and institutional inertia, which hamper integration efforts (Kelly et al., 2018, 2019) and reinforce the status quo (Clarke and Flannery, 2019). Simultaneously, existing institutional theories pose that consequential shifts can also be brought about through more gradual institutional change, for example by re-interpreting existing formal or informal institutions (Mahoney and Thelen, 2010). By using the distinction between formal and informal change, the analysis allows for discussion of the findings on institutional change in the context of this debate.

Participatory Observation for Studying the North Sea Dialogues

The Case of OWF Development in the Netherlands and the NSD

Offshore wind farms development in the Netherlands is a highly regulated and efficient, top-down, national government-led affair (Spijkerboer et al., 2020). In the Dutch marine spatial plan, areas are appointed for OWF (Ministry of Infrastructure and the Environment and Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2015). Letters to parliament are used to explain the timeline for constructing wind farms in these appointed areas (e.g., Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2018). The Offshore Wind Energy Act forms the basis for the licensing procedure for OWF (Staatsblad, 2015). The national government prepares the relevant studies such as the Environmental Impact Assessment for these appointed areas, which form the basis for so-called plot-decisions. These plot-decisions provide the exact coordinates for an OWF within appointed offshore wind energy areas, as well as bandwidths and requirements for constructing the OWF. Subsequently, developers can submit a bid (depending on the specific plot this can be with or without subsidy-schemes), and the highest bid, respectively the bid which requires the lowest amount of subsidy, will gain the right to construct the OWF on a specific plot (Spijkerboer et al., 2020).

Signals about a lack of balance between energy transition and other interests at sea, led the government to start a process for a Strategic Agenda 2030 for the North Sea. However, a broad range of stakeholders felt that this process resembled a “black box,” and that it remained unclear what happened to their input (OFL, 2018). These insights were included in a report which recommended the government to organize NSD with the aim of coming to a North Sea Agreement and included a letter by various stakeholders with the request to organize these Dialogues (OFL, 2018).

As a result of these efforts and reports, the government decided to facilitate in the organization of the NSD. The NSD were led by an independent chairperson and staff. Over the course of 2019, representatives from various sectors, including the domains of energy (both fossil and offshore wind energy), ports, nature (NGOs), fisheries, and the national government (represented by the Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Policy, Ministry of Agriculture, Nature and Food Quality) met regularly in face-to-face meetings. These dialogues were confidential and resulted in a “negotiators-agreement for the North Sea” in February 2020 (OFL, 2020c). This negotiators agreement was presented by involved representatives to their constituencies. In June all participating stakeholders except the fisheries sector1 signed the North Sea Agreement and this version is used when referring to provisions in the agreement in the remainder of this paper (OFL, 2020b). The Dutch House of Representatives accepted the agreement in January 2021. As such, the North Sea Agreement is now an official agreement between the government and various stakeholders, that provides one of the pillars for Dutch North Sea policy until 2030.

The focus of this paper will mainly lie on the content of the dialogues, rather than the set-up of the dialogues as a participatory approach, or the implementation of the agreement. The NSD is a far-reaching participation effort, going beyond just consultation of stakeholders toward a collective decision-making process on North Sea policy. This means that relevant aspects of the agreement must be included by the government in the new revisions of the Dutch marine spatial plans. Moreover, if the government runs into problems that require changes to the agreement, this will need to be discussed with the stakeholders. While the set-up, drawbacks, and benefits of the NSD would be an interesting topic of research in itself, this goes beyond the scope of this paper, particularly because implementation of the agreement is just starting at the time of writing this paper.

Data Collection and Analysis

This paper is based on data collected during participatory observation of the NSD process. Observational methods are suited to gaining insight into what actors actually do, rather than what they say they did (Robson, 2011). As such, this method provides unique insight into the negotiation process and how actors in their interactions actually pursued or hampered institutional change during the NSD.

The author of this paper was hired as part of the independent staff of the NSD and, as such, was immersed in the process. The double position of the researcher as observer and staff member was explained at the beginning and end of the NSD process. These two roles did not conflict with each other, because the purpose of the staff was to facilitate the negotiations and come to an agreement. Being a staff member, the researcher was responsible for among others, collecting information from various stakeholders, writing discussion papers to structure debates, and drafting the agreement based on the input of stakeholders. Raw data, therefore, includes notes and experiential knowledge on the NSD meetings up to the presentation of the “negotiators agreement” in February 2020, internal debates, discussions within the staff and between the staff and members of the NSD, as well as input and debates regarding various draft versions of the agreement. Triangulation occurred by comparing personal notes to official meeting reports constructed by an external party. To ensure the confidentiality of the negotiations were not breached, findings were discussed with a key member who was present throughout the process.

The raw data was organized and categorized into a timeline and, subsequently, condensed into a storyline of 192 pages that describes the process and debates within the NSD. This storyline contains cross-references to raw data for verification purposes. First, deductive coding, based on Table 1, was applied to the storyline to explore to what extent the various dimensions of integration and related normative principles of MSP could be observed during the NSD. This was followed by an analysis of the formal and informal institutional changes that were dominant in progressing particular dimensions of integration. The next section presents and discusses the results, organized according to the dimensions of integration and related normative principles of MSP.

Institutional Change for Integration in the Dutch North Sea Dialogues

Territorial Integration for Area-Based MSP

Territorial integration can be progressed through changes in formal and informal institutions that allow actors to consider the place-based characteristics of specific areas and take into account interactions across scales to enable area-based MSP. Prior to the NSD, the area-based principle was understood as a means to avoid conflict by appointing areas to specific uses such as OWF in the Netherlands (Spijkerboer et al., 2020). Conflicts resulting from local circumstances were mainly recognized and dealt with when designing plot-decisions. Interestingly, it could be observed that during the NSD, debates about specific areas were also often avoided because these debates exposed existing sensitivities and conflicts. Such conflict was particularly noticeable when debating protected nature areas in relation to fisheries (this will be further discussed in section “Policy/Sectoral Integration Between Users and the Environment for Ecosystem-Based MSP”), but also in debates on potential future locations of offshore wind energy areas. As such, a certain level of abstraction in the negotiations proved helpful in coming to the agreement. However, this does not necessarily contribute to solving underlying conflicts. Rather, these conflicts were postponed to a later point in time by means of “process agreements,” which are provisions in the agreement stating that a specific topic will be discussed further in the future. While not leading to any formal institutional change yet, these process agreements do ensure that the government is held publicly accountable for the choices that will be made regarding these topics in the future.

An important factor contributing to this postponement is that, when discussing certain areas, specific knowledge regarding these areas is required. Such knowledge was often not (readily) available. Simultaneously, knowledge gaps regarding specific locations also provided opportunities for stakeholders to oppose certain developments, for example by creating doubts regarding the feasibility of potential locations for OWF. This can be illustrated by the debates in the NSD regarding the option to more quickly start developing OWF in the northern part of the Dutch North Sea. All stakeholders agreed that constructing OWF in the northern part of the Dutch North Sea is inevitable in the long term and that these northern locations may have benefits in terms of higher wind speeds, as well as limiting the impact on other sectors and the environment. The idea was that if the development of OWF areas in the northern part of the Dutch North Sea was prioritized, parts of appointed offshore wind energy areas2 in the more intensively used Southern part of the Dutch EEZ could remain open. This idea would require both formal and informal changes in the priorities for appointing and developing OWF locations. However, in light of the urgency of renewable energy targets, the government did require a check of the feasibility of these suggested northern areas for OWF. The resulting debates illustrate how a lack of site-specific knowledge can be used to halt or delay institutional change when it is not in line with current core values and rules. For example, calculations regarding costs and benefits for the already appointed OWF areas were readily available, but they were compared against rough assumptions and estimates for suggested new areas. Moreover, the assumptions that were used in these calculations were based upon the existing institutional framework, with the dominant rule in Dutch MSP that OWF needs to be cost-efficient and landing points for electricity cables must be located in the Randstad area close to major users of electricity such as the port of Rotterdam. These assumptions are closely related to the financing structure of OWF in the Netherlands in which cable costs are socialized. Moreover, potential opportunities for reducing costs through e.g., international interconnection and storage are not taken into account (see also section “Temporal Integration for Strategic MSP” on temporal integration). Still, the idea of prioritizing OWF development in the northern North Sea was still included as a process agreement, as well as the terms for further research into this idea. Again, these terms also include many conditions based on the existing institutional framework, for example, related to the costs and speed of the energy transition (see provision 4.9–4.11 of the Agreement). This example shows the importance of site-specific knowledge for territorial integration. A lack of site-specific knowledge can lead to assumptions that are strongly grounded in the current formal and informal institutional frameworks. Nonetheless, the agreement does create opportunities for institutional change in the future because it communicates broad support for this idea and commitment to further research in the form of process agreements.

Stakeholders also agreed upon the need for more area-based approaches that take into account local characteristics of an area. This was particularly the case for discussions regarding multi-use of areas. Section “Organizational Integration and Policy/Sectoral Integration Between Users for Integrated MSP” on policy/sectoral integration illustrates that in some cases it was possible to devise general rules. However, stakeholders in the NSD agreed that in many cases the local circumstances are key to determining whether certain forms of multi-use are potentially feasible. While all stakeholders supported the idea of area-based approaches during the NSD, representatives from the ministries did caution that uniform approaches create more regulatory clarity and are easier to enforce. Nonetheless, formal institutional change toward more territorial integration was achieved by introducing the instrument of the “area-passport.” Provision 4.1 of the Agreement states that before appointing areas at sea for a specific purpose (for example plot-decisions for OWF), and after deliberation with stakeholders, the government will construct an area-passport. The goal of this passport is to explicitly take into account current and potential future uses of this area when designingan OWF. As such, a formal rule is introduced to ensure that various potential co-uses are identified and supported prior to constructing an OWF. This formal rule progresses territorial integration toward improved area-based MSP.

Organizational Integration and Policy/Sectoral Integration Between Users for Integrated MSP

Organizational integration can be progressed through changes in formal or informal institutions that improve cooperation and coordination within and between government and stakeholders to enable integrated MSP. During the NSD, it became clear that fragmentation within the government was a major point of frustration for stakeholders prior to the NSD. While literature often speaks of “the government,” significant fragmentation in responsibilities exists between and within various ministries and governmental agencies. This fragmentation caused stakeholders to experience institutional barriers resulting from inconsistencies, shifting priorities, and a lack of communication between various ministries and government agencies. During the NSD, however, the three directly involved Ministries were stakeholders themselves, represented by the director-general of the relevant departments in each ministry. Moreover, there was one director responsible for coordinating information-flows within “the government” and between the government and the NSD. As a result, the government was challenged to organize coordination of information and expertise within and between all relevant ministries and departments (which was broader than just the three ministries that were directly involved) and the NSD. Government representatives acknowledged during the NSD that this process led to significant improvements in the cooperation and coordination within and between ministries and departments because they needed to speak with “one voice” during the NSD. While formal responsibilities remained unchanged, the informal communication structure within the government was adapted. Appreciation for this enhanced coordination within the government was also expressed by stakeholders. They appreciated, for example, the clarification of the position of the government regarding various topics, the stable interaction with the government including a clear contact-point, and the increased trust in the government. As such, the NSD progressed organizational integration by improving coordination and cooperation of information flows within the government. Interestingly, this form of organizational integration relied mainly on informal changes in the norms and habits regarding collecting and sharing information within the government, and between the government and other stakeholders within the NSD.

It is important to mention that similar processes of organizational integration could also be observed among other stakeholder groups. For example, the fisheries organizations that were represented in the NSD, which are traditionally competitors, unified behind a joint vision document in which they clarified their view on the issues that were debated in the NSD (VisNed, 2019). Similarly, the various NGOs that were involved coordinated their input into the NSD, despite having different focal points (e.g., the position of NGOs regarding OWF can vary depending on whether they focus on wildlife in general, birds, or environmental pollution). The NGO representatives could often be observed to negotiate among themselves prior to meetings, they coordinated their responses to new information, and they always created joint input-documents to present their view on various issues that were being discussed. The setting of the NSD caused organizations that represented similar interests to form a “unified front” for their overarching interests, rather than fighting openly among themselves which could have weakened their position. These examples illustrate that organizational integration within stakeholder groups, while not prominent in existing literature, might also be an important aspect of organizational integration that can be encouraged in MSP processes.

However, there are limits to organizational integration, which can be illustrated using the example of the “transition fund.” The idea of such a fund was inherently connected to the idea of a North Sea Agreement prior to the start of the NSD (OFL, 2018). The idea behind this transition fund was to enhance coordination in the financial flows for various aspects of North Sea policy. This included financial flows relating to enforcement, research and innovation, but also to fill gaps related to the implementation of the agreement that were not covered by existing (sectoral) funds. All parties agreed that some kind of streamlining in funding was necessary and the idea of this fund was debated extensively during the NSD from the first meetings onward. Stakeholders were in favor of a fund that would be independent of the NSD and the government. However, this turned out to be unacceptable due to general rules on budgeting and funds within the government. Eventually, agreement was reached in the NSD on a set of financial-procedural rules on how to spend the funds that were made available by the government for the implementation of the agreement. Therefore, while funds were made available for implementing the North Sea Agreement, formal institutional change toward financial-organizational integration during the NSD remained limited.

Policy/sectoral integration can be progressed by changes in formal or informal institutions that improve cooperation and coordination between various users of the sea and the policy frameworks that guide them, to enable integrated MSP. This form of integration refers to general rules for cooperation and coordination, rather than the area-based rules discussed in section “Territorial Integration for Area-Based MSP.” An example of such policy sectoral integration is the formal institutional change that was achieved regarding cutter fisheries within OWF. While the fisheries sector initially argued for access to wind farms, debates and discussions within the NSD regarding risks and alternatives led to a shift in perspective. In the vision document that the fisheries sector prepared for the NSD, they acknowledged that with the current fisheries techniques and set-up of OWF, it is not (yet) feasible to use cutters for fisheries within OWF (VisNed, 2019). As a result, the agreement includes a provision (4.24) stating that for the near future, cutter fisheries within wind farms will not be allowed. Another example relates to passage for smaller ships through wind farms. Debates focused on whether to allow for free passage through wind farms versus dedicated passageways. Within the NSD, this debate regarding shipping also related to topics such as compatibility with other forms of multi-use (e.g., seaweed farming might not be compatible with free passage for ships), risks to the OWF itself, and issues such as enforcement. Moreover, while at first debates centered around 45 m as the maximum length for ships to pass through OWF, the NSD provided a platform for the fisheries representatives to mention that many cutters are slightly larger and argue for an extension to 46 m.3 The resulting provision (4.23) in the agreement states that as a general rule “the government will strive for appointment of passageways for ships up to 46 meters […]” (OFL, 2020b, p. 21). These examples show that the NSD progressed user-user integration mainly by changing formal institutional rules. Informal institutional change of norms and values for communicating created open debate and an increased understanding of various points of view among stakeholders, which created opportunities for such formal institutional change. It is important to notice that policy/sectoral integration requires the clarification of uses that are considered (potentially) compatible, but also the specification of uses that are considered incompatible. Moreover, the breadth of discussions regarding e.g., the passage for shipping shows that a platform for negotiating and deliberating these issues is crucial for progressing policy/sectoral integration in line with integrated MSP.

Policy/Sectoral Integration Between Users and the Environment for Ecosystem-Based MSP

Policy/sectoral integration between users and the environment can be progressed by changes in formal or informal institutions that ensure sustainable use of the environment to enable ecosystem-based MSP. While not explicitly mentioning the ecosystem-based approach, the idea of a “healthy North Sea” is prominent in the North Sea Agreement, as is the idea that this requires additional efforts compared to the current situation. Debates during the NSD focused on the degree to which the “good environmental status” as laid down in the Marine Strategy Framework Directive (MSFD) should be explicitly used as a benchmark or whether to use the framing of a “healthy North Sea,” as well as how to measure progress toward these targets. These debates laid bare pre-existing tensions, particularly between the fisheries sector and the NGOs, but also raised questions regarding the use and interpretation of various indicators that can be used to operationalize these concepts in relation to OWF development. Moreover, it became apparent that, despite increasing efforts, there is still a lack of scientific knowledge regarding many aspects of the ecosystem and the impacts of various (cumulative) human users (see also section “Knowledge Integration for Adaptive MSP” on knowledge integration). These examples illustrate that in progressing user–environment integration, actors initially pursued institutional change primarily through a reinterpretation of existing institutional frameworks.

Even though not all these debates reached a definite conclusion, the NSD and agreement did encourage a shift in the understanding of the position of the ecosystem compared to previous Dutch MSPs and even the government’s coalition agreement for the period 2017–2021 (Rutte et al., 2017). Prior to the NSD, EU threshold values for environmental protection and biodiversity were considered “targets rather than threshold values” (Spijkerboer et al., 2020, p. 5). This idea was rejected during the NSD, which prominently supports the idea of “going additional miles for a healthy North Sea,” particularly in light of the increasing intensity of use such as OWF. While the existing formal rule is rejected, it is not yet replaced by a new formal rule but rather by an informal aspiration, the shape of which will depend on future actions of stakeholders. However, the importance of this change should not be underestimated because it required the responsible minister to acknowledge that this agreement would exceed the governing period of the current administration, thereby allowing for the North Sea Agreement to include provisions that are not in line with the perspective of the coalition government at that time.

Although stakeholders had different opinions on how to operationalize the new aspiration of “a healthy North Sea,” the fact that there was a shift in this aspiration can be illustrated by the debates between representatives from the fisheries sector and NGOs. For example, despite the fisheries sector not signing the agreement as explained in chapter 3, this sector was open to discussing a significantly higher percentage of the Dutch North Sea being closed to sea-bed fisheries than in any previous negotiations on this topic. During these debates, percentages that were seriously discussed ranged between 10 and 15%, compared to the existing 5.1% that was proposed for implementation prior to the start of the NSD. The debates regarding these percentages were strongly influenced by the definition of “sea-bed fisheries” and what is considered sea-bed disturbance. This was already the case prior to the NSD. For example, the government initially claimed that proposed measures amounted to a higher percentage than 5.1%, because they used a definition focusing on “significant sea-bed disturbance,” which allowed certain types of fisheries within the closed areas because of their relatively limited impact on the sea-bed (Vrooman et al., 2018). An important aspect of these debates was also whether to include windfarms (which are closed to fisheries) in these percentages or not. Provision 4.38 of the Agreement eventually states that 13.7% of the Dutch North Sea will be closed to any form of sea-bed disturbance by fisheries in 2023, with a rise to 15% in 2030. These percentages are to be appointed within recognized ecologically valuable areas, such as areas appointed on the basis of the European Bird- and Habitat Directives or the European Marine Strategy Framework Directive. However, this provision is conditioned by the availability of funds for the transition of the fisheries sector.4 This is an, albeit still disputed, change in the formal rules regarding protected areas in the Dutch North Sea.

This formal rule change is also supported by a different way of rationalizing the choice for protected areas, focusing more on the quality of protected areas over just quantity. Based on suggestions from the scientific advisory committee that assisted during the NSD, the idea of considering the “relative ecological value” of areas (but also wind turbines and gas platforms) was included in considerations regarding protected areas. Using this concept, identified ecologically valuable areas could be ranked according to their relative ecological value for the Dutch North Sea. Following this idea, improving the protection of the highest-ranked areas will then provide the highest overall ecological benefits to the system. This concept was used to rationalize the choices for additional protection in certain areas, while still weighing this against other interests in these areas. While this change in rationalization hints at informal institutional change, it is important to mention that there is no provision in the agreement that guarantees the use of this concept of relative ecological value in the future. Whether this will be a lasting informal or formal institutional change, therefore, remains to be seen.

The aspiration of a healthy North Sea is also supported by some formal changes in rules, for example by including provisions regarding the use of “best available techniques” for the construction of installations, nature enhancing construction, and mitigating the impact on the ecosystem. As such, the NSD progressed integration between users and the environment through a rejection of the existing interpretation of the institutional framework (deinstitutionalization), through changes in formal rules to mitigate impacts and enhance protection, as well as new more informal changes in rationalizing these choices and measures. While a new understanding of ecosystem-based MSP is starting to take shape in the North Sea Agreement, this new understanding is not yet fully formed and remains somewhat disputed.

Examples of remaining disputes include the rejection of the agreement by part of the fisheries sector, but also a list of topics that remain unresolved. One topic on this list is, for example, the debate regarding the potential strengthening of the norms for underwater noise during construction. NGOs, the government, and the offshore wind sector could not agree upon the interpretation of relevant data and norms. These disputes over the interpretation of indicators remain. Nonetheless, the examples above do show the willingness of various economic sectors to debate and agree to enhanced efforts to protect and improve the ecosystem, within certain boundaries.5 Particularly for the offshore wind sector and the oil- and gas sector, this willingness involved agreeing to a partly unknown costs increase (related to e.g., using best available techniques and nature enhanced construction), which could be a threat to their business case. Moreover, process agreements on these topics ensure future communication and debate on the use and interpretation of indicators and norms, thereby opening pathways for future institutional change.

Stakeholder Integration for Participatory MSP

Stakeholder integration can be progressed by changes in formal or informal institutions that allow for meaningful stakeholder inclusion and that contribute to creating mutual understanding and trust between stakeholders to enable participatory MSP. It is important to recognize the NSD itself as an important, initially temporary, and more informal institutional change to progress stakeholder integration. As a temporary platform, the NSD did not require changes in formal responsibilities. However, it did require political willingness and funds to assign a chairperson and staff to lead the negotiations, as well as the commitment of all parties including the government. Over the course of the NSD, this chairperson and staff proved key in protecting the position of the NSD in the broader context of policy and law-making. For example, the NSD chairman was essential in emphasizing and ensuring the recognition of the role of the NSD and the North Sea Agreement as an agreement between the government and stakeholders, rather than an advisory report or council. Moreover, the chairperson and staff confronted stakeholders when the rules regarding the functioning of the NSD—which were agreed upon by all parties at the start of the NSD—were breached. This happened, for example, when the NSD was excluded from relevant ongoing processes within government. Another example is when public statements of certain stakeholder groups (often unrelated to the NSD process) were disrespectful to other parties in the NSD. As such, the NSD illustrates the importance of a platform for open deliberation and building mutual trust between stakeholders, even when it is through a temporary arrangement. This platform proved key to creating the conditions under which opportunities for institutional change arose and could be acted upon.

During the NSD, it became increasingly clear that stakeholders, including the governmental delegation, did not want to return to the situation prior to the NSD. Stakeholders agreed that a form of “permanent NSD” was necessary to ensure open communication between stakeholders, but also to deal with changes that potentially affect the agreement and new knowledge (see also section “Knowledge Integration for Adaptive MSP”on knowledge integration). While much debate centered around the form and legal basis of this “permanent NSD,” the fact that there will be a permanent NSD (as laid down in chapter 8 of the Agreement) is a substantial formal institutional change that progresses stakeholder integration in line with participatory MSP. This permanent NSD reinforces meaningful stakeholder participation in the future, by ensuring that policies that potentially contradict the North Sea Agreement cannot be made without renegotiation in the context of the NSD. As such, the permanent NSD provides a strong platform for stakeholders to hold each other and the government accountable for potential breaches of the agreement. The permanent NSD is a major formal institutional change in the governance of the Dutch North Sea, that is achieved by adding a new “layer,” rather than changing existing formal responsibilities.

It is important to mention that enhancing meaningful participation in this manner can also pose difficulties for the government and stakeholders. For the government, responsibilities with regards to the NSD and agreement need to be balanced against the responsibilities that derive from existing statutory consultation as required in existing laws. These statutory processes and political debates in parliament can lead to amendments in policy documents and laws that can potentially contradict the agreement. This example illustrates that a range of questions arise with regards to legitimacy and good governance as a result of more direct participation processes like the NSD, also because it is always a choice who is included in such participation efforts. Simultaneously, while signing the North Sea Agreement does not limit any formal rights for stakeholders, they did accept that before they object and appeal future decisions, they will try to reach consensus in the permanent NSD. This example illustrates some more informal changes brought about by the NSD that affect future interactions between and among stakeholders and the government.

Literature on stakeholder integration in MSP generally argues for broad involvement of stakeholders (Reay and Jones, 2016; Flannery et al., 2018; Grimmel et al., 2019; Morf et al., 2019; Quesada-Silva et al., 2019). However, some authors question whether smaller, more focused inclusion efforts might be more successful (Smythe and McCann, 2018; Vince and Day, 2020). During the NSD, the question regarding the inclusion of a broader range of stakeholders caused much debate, particularly at the start when many parties requested to join the NSD. It was a conscious decision not to broaden the range of included stakeholders because of practical reasons such as available meeting space and being able to maintain structure during meetings, which would be much more difficult with a larger group of representatives. Stakeholders did use their ties to the various parties that requested to participate in an attempt to cover their interests by representation. For the permanent NSD, this issue is addressed and laid out in a separate governance agreement for the North Sea (OFL, 2020a). The experience from the NSD would point toward the inclusion of a broad range of stakeholders to enable inclusion and consideration of a broad range of interests but by a limited number of representatives.

Knowledge Integration for Adaptive MSP

Knowledge integration can be progressed by changes in formal or informal institutions that allow actors to develop joint research, share information, and respond to new insights throughout the planning cycle to enable adaptive MSP. The formal institutional change in the form of the permanent NSD allowed for issues that could not be resolved in the time set for the NSD (e.g., due to knowledge gaps or conflict) to be placed on the agenda for future deliberation (the so-called “process agreements”). Moreover, the continuation of the NSD allowed for the agreement to include provisions that require periodical revision. Examples of such provisions include the definition of best available techniques for a specific period and the development of a two-yearly “state of the North Sea” report that provides transparency regarding the progress toward a healthy North Sea. The agreement also includes provisions that require the NSD to be involved in any changes in response to new insights, conflicts, and developments that infringe upon the agreement. These examples show how during the NSD, stakeholders pursued formal institutional changes that support information sharing and provide opportunities to respond to new insights. Thereby, stakeholders progressed knowledge integration in line with adaptive MSP.

Moreover, the significant fragmentation and gaps in knowledge regarding a broad range of topics concerning the North Sea, led actors to push for a joint research agenda that is tied to and, when necessary, financed by funds allocated to the implementation of the North Sea Agreement. There was a relatively high amount of agreement between stakeholders regarding the content of the research agenda. However, the coordination and distribution of responsibilities and funds for this research agenda was highly disputed between government and stakeholders. This shows that in progressing knowledge integration, formal institutional changes regarding finances and responsibilities are most difficult to achieve. Nevertheless, the development of a dedicated joint research agenda with associated funds for the North Sea is an important additional formal institutional change that progresses knowledge integration and learning in MSP, while also counteracting fragmentation of knowledge and pushing for results to be made publicly available.

The NSD also helped create mutual understanding between stakeholders for their respective points of view and proved helpful in resolving pre-existing and rising conflicts. The fact that the content of the negotiations was confidential contributed to creating this understanding between stakeholders, because it allowed for open debates on issues that were highly disputed between the same stakeholders in public. An example of creating understanding between stakeholders is related to the fisheries sector. Before the NSD and during the first months of the NSD, many stakeholders had difficulties in understanding why it was almost impossible for the fisheries representatives to present maps that show areas that are most important to them. The months of debates, explanations, and presentations in the NSD—including presentations by fishermen using the maps they use while fishing—slowly created an understanding among other stakeholders of the reasons behind the difficulties for the fisheries sector in creating these maps. While this does not resolve problems necessarily, stakeholders slowly developed a mutual understanding of the reasons behind each other’s actions and perceptions. Examples of resolving rising conflicts can be found in the fact that stakeholders would address issues that affected mutual relations in the first NSD after incidents occurred. On multiple occasions, disputed statements that were published in media, or breaches of other prior agreements would be discussed in the NSD. This also includes, when necessary, apologies and debates regarding potential solutions. These examples show how the NSD also created informal institutional change toward knowledge integration, by changing the norms for how stakeholders treated and addressed each other in both every-day situations, as well as in situations of conflict. While the immediate effects of these changes might be more limited, the understanding and trust that was created might contribute to creating opportunities for future institutional change.

Temporal Integration for Strategic MSP

Temporal integration can be progressed by changes in formal or informal institutions that allow actors to make proactive decisions based on potential future developments to enable strategic MSP. As such, this dimension of integration is also about the capacity of actors to behave strategically and act pro-actively in light of potential future developments. Again, the permanent NSD as a formal institutional change is an important platform that enables stakeholders to act proactively in light of projections regarding uncertain future development. However, the NSD also illustrates that changes that progress temporal integration toward more strategic MSP remains extremely difficult in practice. Stakeholders appear to be able to assess the potential consequences of changes such as an area-passport, or using best available techniques for construction. However, it appears to be very difficult for stakeholders to reflect upon the feasibility of changes that would take effect in the long term (e.g., in ten or more years). In these cases, stakeholders, including the government, could be observed to rely heavily on current institutional frameworks in assessing the feasibility of these future developments. This can be illustrated using the earlier example of speeding up the construction of OWF in the northern North Sea and leaving some appointed areas in the southern North Sea open. To enable the development of OWF in the Northern North Sea after 2030, decisions on these ideas would have to be made within the next few years. Many of the foreseen benefits of this solution are connected to technological developments such as larger wind turbines that would generate more electricity, but also international interconnectors to distribute electricity, or hydrogen solutions. The speed, costs and, innovation trajectories of these developments are uncertain. The government could be observed to apply today’s context and institutional framework to calculations (e.g., the current costs of high voltage direct current cables to user hotspots like the Port of Rotterdam, without taking into account the potential cost reduction opportunities offered by international interconnections or hydrogen solutions). As a result, the costs of this solution were presented as being extremely high which undermined the feasibility of this idea. Nonetheless, stakeholders managed to include this idea in the agreement as a process agreement that will require further research, referring it to the permanent NSD. This example illustrates that is it is difficult for stakeholders, the government particularly, to progress temporal integration in line with strategic MSP, because the current formal and informal institutional framework is applied as a frame of reference to assess the feasibility of ideas for the future. Simultaneously, the permanent NSD does provide stakeholders with the opportunity to progress temporal integration, because it creates a platform where stakeholders can place these issues on the agenda for further deliberation and negotiation.

Conclusion: the Institutional Dimension of Integration in Marine Spatial Planning

This paper set out to explore the formal and informal institutional changes that were pursued by actors during the NSD to progress the various dimensions of integration in line with the normative principles that are attributed to MSP. These dimensions of integration and normative principles are important components of MSP processes that aim to improve spatial integration between OWF and other interests at sea. A first important conclusion is that the—initially only temporary—institutional arrangement of the NSD itself proved key because it provided a platform for actors to pursue formal and informal institutional change. This platform helped create mutual understanding and open deliberation on issues that were sometimes highly disputed. Thereby, the results from this study support the calls for “round tables” or platforms for structural cooperation between sectors (Olsen et al., 2014; Saunders et al., 2019), and indicate that such a platform should allow for actors to interact and deliberate on various ideas in an open manner. Moreover, the results show that besides formal institutional changes, the platform offered by the NSD caused actors to pursue informal institutional changes that were extremely important in progressing specific dimensions of integration. For example, organizational integration toward more integrated MSP was to a large extent progressed by changes in informal institutions such as the norms and customs for communicating and sharing information within the government or between stakeholders within one sector.

The formal institutional changes that were pursued by actors usually filled a policy gap or extended existing regulation by adding additional institutions to the existing system in a form of policy layering (e.g., the area-passport or passageways for shipping), rather than abolishing existing institutions or major shifts in responsibilities. Sometimes, the changes pursued by actors also took the form of planting seeds for ideas, and it remains to be seen whether these will grow or die down (e.g., the relative ecological value). Moreover, informal institutional changes in the form of reinterpretation of existing rules also played an important role (e.g., the rejection of the old understanding of ecosystem-based MSP and new aspirations surrounding a healthy North Sea). The permanent NSD itself is also a good example of the institutional changes that were pursued during the NSD: the permanent NSD does not require abolishment of existing institutional frameworks regarding who is responsible for what, but it does add important formal and informal institutions to the existing system. While these institutional changes might not address all persistent problems in marine governance (cf. Kelly et al., 2019), the case of the NSD shows that more incremental forms of institutional change should not be discredited, as they can be effective in progressing the variousdimensions of integration and improving spatial integration in the Dutch North Sea.

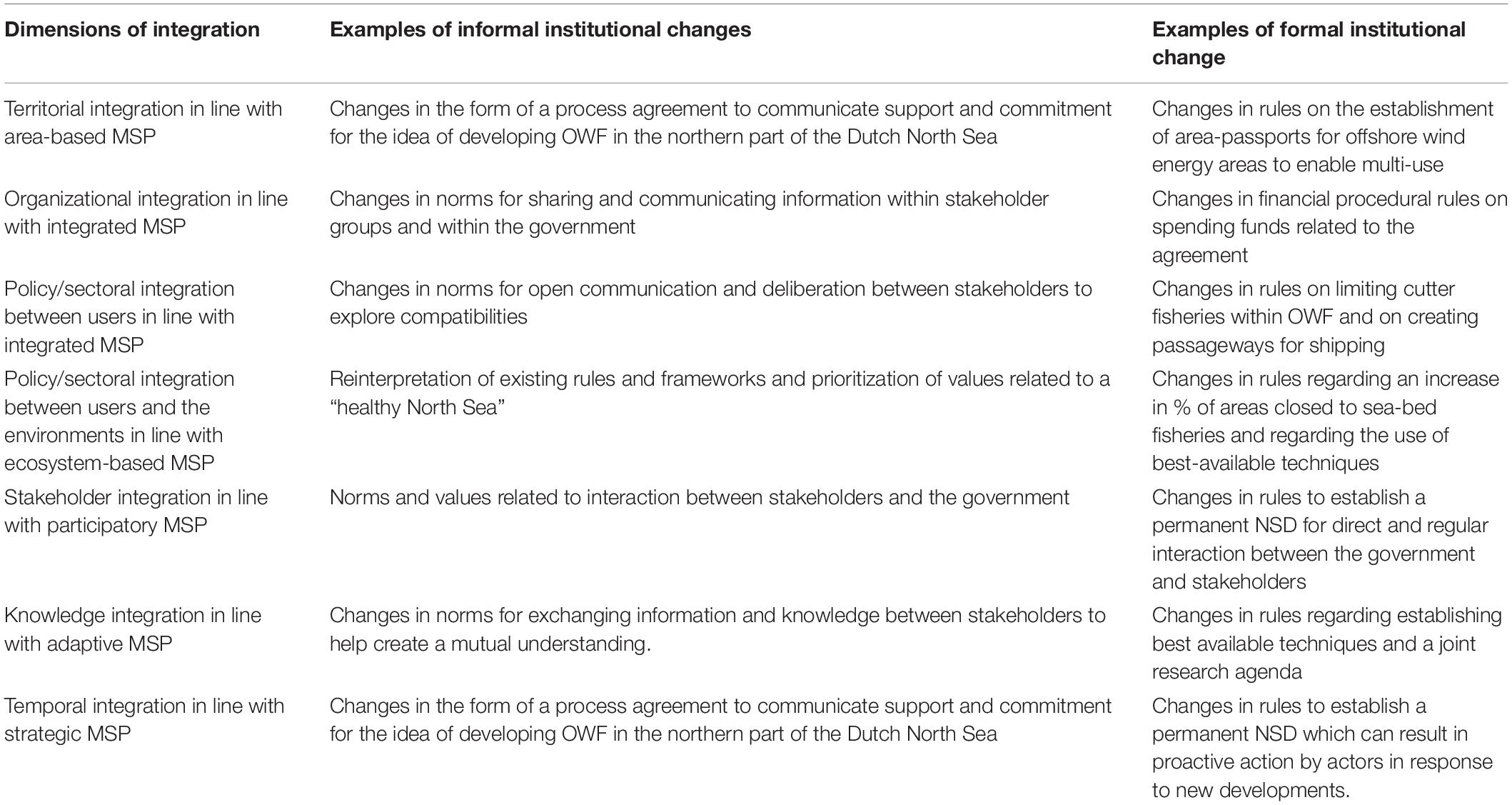

It can be concluded that the institutional changes achieved during the NSD do progress all dimensions of integration (see Table 2), albeit to various degrees. As such, the NSD contributed to spatial integration, mainly by means of more incremental institutional changes. The results indicate that a range of subsequent incremental changes might lead to a more radical change in participatory governance of the North Sea in the form of the establishment of a permanent NSD, but this will require further research into the effectiveness of the NSD on the long-term. However, the case of the NSD also illustrates the most important difficulties with this more incremental approach. Particularly when considering longer time periods (temporal integration), or when considering specific locations (territorial integration on the local scale), actors heavily rely on existing formal and informal institutional frameworks. This was illustrated using the examples of developing OWF in the northern North Sea, as well as the debates surrounding additional protection regimes for ecologically valuable areas. In these cases, stakeholders refer to existing formal and informal institutional frameworks, while their capacity to reflect on these frameworks appears to be limited. Table 2 shows that in these cases informal institutional changes were mainly assisted by the platform of the NSD, which created the option of process agreements. These process agreements can be seen as informal institutional changes that communicate support for new ideas and understandings. As a result, the institutional space for finding solutions in these specific cases also appears to be more limited and more radical forms of change might be necessary to enable spatial integration.

Table 2. Examples of formal and informal institutional changes that were used to progress the various dimensions of integration in line with the normative principles of MSP.

This paper shows that it is important to not only take into account formal institutional changes, but also informal institutional changes. This paper used a broad definition of informal institutional change as changes in the unwritten conventions, norms and codes of conduct (Kingston and Caballero, 2009). This broad definition was used to explore the informal changes that could be observed in a general sense. In light of the importance of informal institutional changes in the results from this study and the lack of attention to such informal changes in existing research, it is recommended that future research will further explore and explain informal institutional change and how these informal changes are interrelated with the formal changes that are either progressed or hindered in practice. Existing theories on informal institutional change in planning could provide fruitful starting points for such research, including, for example, theories on institutional capacity building in collaborative planning (Healey, 1999), theories on frame reflection (Schön and Rein, 1994) and “living institutions” (Hajer, 2006). Another option is to explore the use of actor-oriented institutional theories such as discursive institutionalism (Schmidt, 2008) and institutional work (Lawrence and Suddaby, 2006; Beunen and Patterson, 2019), which can provide more detailed insight in the agency of actors in organizing institutional change on the micro-level.

The NSD also shows some drawbacks and boundaries to participatory approaches within MSP. It was very difficult to keep all stakeholders and their constituencies on board during the NSD process. This is illustrated most clearly by the difficulties related to the fisheries sector, but it was an issue that representatives from the wind sector, the oil- and gas sector, the NGOs, and the government mentioned during the NSD. The negotiations, and the understanding that is created between stakeholders throughout these negotiations, is only experienced by the representatives. However, the implementation and effects of changes in formal and informal institutions will weigh on their constituencies who do not necessarily share these experiences. Therefore, it will be interesting for future research to look into the implementation and effects of the North Sea Agreement and processes of stakeholder negotiation in other countries. Moreover, it will be important to study whether and how in arrangements that organize participation through the representation of sectors, the connections to the constituencies of these representatives can be maintained, particularly when a degree of confidentiality is beneficial to the negotiations themselves.

The insights from the NSD show that meaningful participation can only be achieved when both stakeholders and the government contribute to the process: the government needs to offer space that enables actors to pursue and implement institutional change, but stakeholders also need to take responsibility and look beyond their own interests. The presence of the NSD chairman and staff was key in this struggle, as they constantly had to remind both government and other stakeholders of their contributions to this process. As illustrated most clearly by the example of the transition fund, the NSD was also a struggle by and for stakeholders to claim institutional space which was not always willingly offered, particularly when it related to changing formal responsibilities.

Based on these insights regarding the NSD processes, it would be interesting for future research to study the possibility of temporary or “soft” institutional arrangements in improving spatial integration offshore. Based on these insights, recommendations for policymakers and scientists alike would be to examine the use of quasi soft spaces (cf. Jay, 2018; Walsh, 2021), that help create a platform for stakeholders to pursue institutional change. Simultaneously, experiences from the NSD would suggest that even such temporary and more soft arrangements do require financial backing, an independent chairperson and staff, as well as commitment from all parties including the government to implement changes that are agreed upon. These spaces can create the required institutional conditions under which actors can pursue further institutional changes. How these spaces can be connected to the trans-national domain will be an important topic of study as well.

Discussions in existing MSP literature on integration provide highly relevant insights in various dimensions of integration processes on a more abstract, governance level. However, in essence, MSP is about integrating various users and interests in space. As such, it becomes even more important for MSP literature to return to a focus on spatial integration, including the interrelations and cooperation between interests and users at various scales from local to international. The analysis in this paper shows that the “spatial dimension” of MSP, in the form of spatial integration, can be progressed by actors pursuing the various dimensions of integration, but that it is important to take into account the interrelations between these dimensions. For example, territorial integration aimed at area-based MSP can ensure that specific area-based characteristics are incorporated into decision-making procedures, and related to the patchwork of users that occupy an area or sea-basin to progress spatial integration. However, progressing spatial integration also requires that actors simultaneously pursue, for example, user-user integration to understand the needs and interests of these other users, user-environment integration to ensure that this patchwork of uses fits within the environment, and knowledge integration to test new ideas and develop mechanisms to respond to potential issues that are encountered. As such, spatial integration in MSP requires not only attention to all the dimensions of integration, but also to their interrelations.

Additional research is needed to further develop the concept of spatial integration in MSP. Future research could explore specific cases to examine the reasons behind choices for the establishment of multi-use sites or specific single-use sites (cf. Schupp et al., 2019) to provides insight into opportunities and barriers for spatial integration that are experienced by actors in practice. Moreover, future research could examine the manners in which stakeholders can be enticed to broaden their perceptions of institutional possibilities when, for example, exploring areas for OWF development in the future that benefit from decision-making today. The institutional dimension of integration can then be seen as a learning process in which actors search for institutional space that allows them to find physical space to achieve such spatial integration.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets presented in this article are not readily available because of confidential information that cannot be separated from the content of the data set. Requests to access the datasets should be directed to RS, ci5jLnNwaWprZXJib2VyQHJ1Zy5ubA==.

Ethics Statement

Ethical review and approval was not required for the study on human participants in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. Written informed consent for participation was not required for this study in accordance with the national legislation and the institutional requirements.

Author Contributions

The author conceptualized and designed the study, conducted data collection and analysis, and wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors. Funding for the open access fee was received from the Faculty of Spatial Sciences Open Access Fund, University of Groningen.

Conflict of Interest

The author declares that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Jacques Wallage, Christian Zuidema, Tim Busscher, and Jos Arts and for contributing their thoughts on the manuscript.

Footnotes

- ^ Due to fragmentation among the constituency of the fisheries organizations regarding support for the North Sea Agreement, these organizations have decided against signing the agreement. The parties to the North Sea Agreement are searching for manners to incorporate the fisheries sector in the agreement (Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, 2020).

- ^ These (parts) of areas were not included in the existing Roadmap for OWF because they were, for various reasons, considered the least feasible options when the Roadmap was constructed. Reasons that were mentioned included conflicts due to the impact on other sectors and the environment (Ministry of Economic Affairs, 2018).

- ^ This provision relates solely to passage through OWF, not the act of fishing.

- ^ Early on during the NSD, a parallel trajectory was started to develop a vision for the transition of the cutter fisheries sector. This parallel trajectory focused on issues that were internal to the fisheries sector and not directly related to balancing the fisheries sector and other interests at sea. However, from the start of the NSD processes, it was acknowledged that this transition would require funds and that these funds were part of the NSD process.