- 1School of Natural and Built Environment, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, United Kingdom

- 2Institute for Marine and Antarctic Studies, University of Tasmania, Hobart, TAS, Australia

Macroalgae, with their various morphologies, are ubiquitous throughout the world’s oceans and provide ecosystem services to a multitude of organisms. Water motion is a fundamental physical parameter controlling the mass transfer of dissolved carbon and nutrients to and from the macroalgal surface, but measurements of flow speed and turbulence within and above macroalgal canopies are lacking. This information is becoming increasingly important as macroalgal canopies may act as refugia for calcifying organisms from ocean acidification (OA); and the extent to which they act as refugia is driven by water motion. Here we report on a field campaign to assess the flow speed and turbulence within and above natural macroalgal canopies at two depths (3 and 6 m) and two sites (Ninepin Point and Tinderbox) in Tasmania, Australia in relation to the canopy height and % cover of functional forms. Filamentous groups made up the greatest proportion (75%) at both sites and depth while foliose groups were more prevalent at 3 than at 6 m. Irrespective of background flows, depth or site, flow speeds within the canopies were <0.03 m s–1 – a ∼90% reduction in flow speeds compared to above the canopy. Turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) within the canopies was up to two orders of magnitude lower (<0.008 m2 s–2) than above the canopies, with higher levels of TKE within the canopy at 3 compared to 6 m. The significant damping effect of flow and turbulence by macroalgae highlights the potential of these ecosystems to provide a refugia for vulnerable calcifying species to OA.

Introduction

Marine macroalgae (seaweeds) grow benthically in coastal waters worldwide, providing a range of ecosystem services including primary production, habitat creation, carbon, and nutrient cycling (Hurd et al., 2014). Seaweed growth and hence primary production is regulated by a range of abiotic drivers including light, inorganic carbon and nitrogen supply, temperature, and water motion. Of these regulating factors, the least studied is water motion, which controls the mass transfer of dissolved carbon and nutrients to and from seaweed surfaces thereby regulating the chemical microenvironment (e.g., Wheeler, 1980; Kregting et al., 2015). More generally, water movement also influences the physical environment by modifying the underwater light regime (Wing and Patterson, 1993) and local temperature gradients (Hurd et al., 2014). It also controls top down processes such as herbivory, epiphytism, and pathogens (Hurd, 2017).

In temperate coastal waters, seaweeds grow on rocky substratum in morphologically complex canopies that consist of numerous species of varying morphologies. The understory is comprised of typically leafy smaller red (Rhodophyta), green (Chlorophyta) and brown (Ochrophyta and Phaeophyceae) seaweeds (nominally <0.2 m). Larger seaweeds, typically browns, can form one or more canopy layer(s) above with either flat blades, single stipes or complex stipe clusters. The height of the canopy will depend on the dominant canopy-forming species – typically >1–4 m but can be >15–40 m for seaweeds such as Macrocystis pyrifera and Nereocystis luetkeana. Seaweeds act to modify the water flow structure within a canopy and the degree to which this will happen depends on the canopy morphology (Kregting et al., 2011).

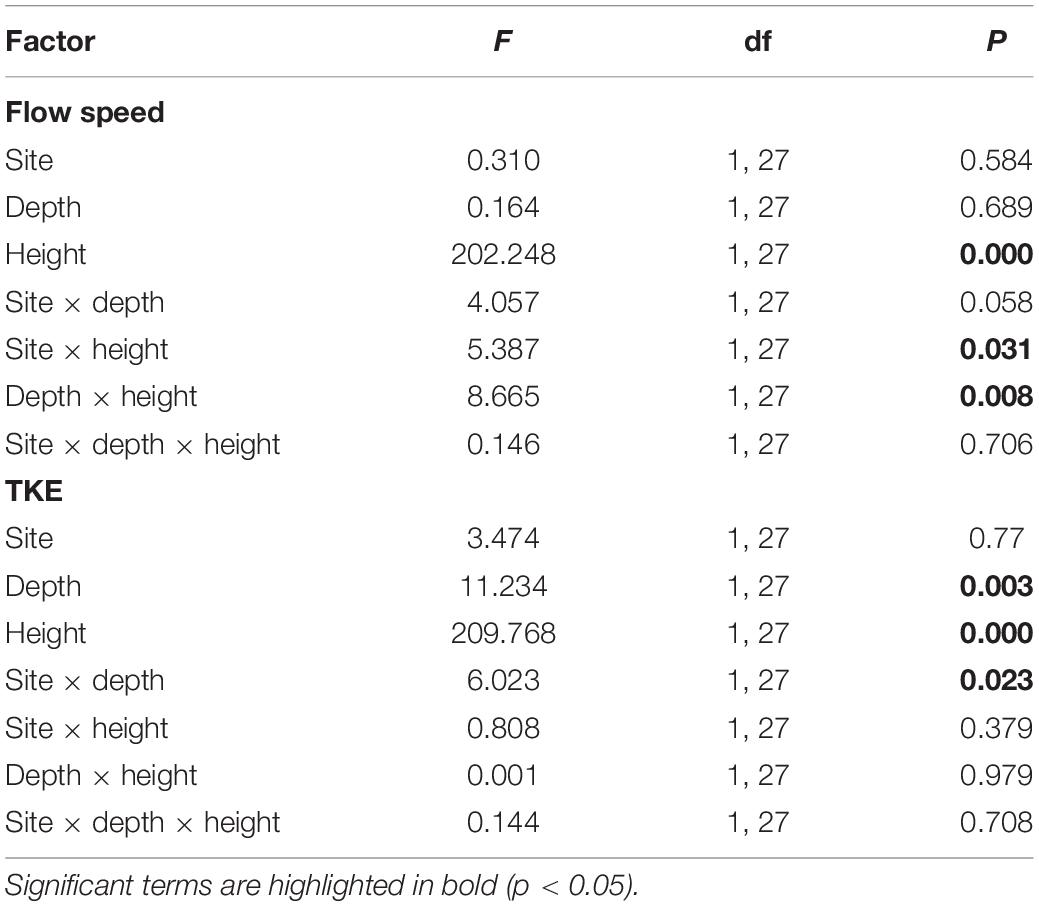

When a moving fluid (here seawater) interacts with a solid surface (seaweed) a velocity gradient forms. At the fluid-solid interface, flow speed is zero, due to the no-slip condition. The velocity then increases to that of the mainstream seawater some distance from the surface: this is termed the velocity boundary layer (VBL; Wheeler, 1988; Hurd, 2000). Individual seaweeds each have a VBL associated with their blades, and within the laminar region of the VBL lies the diffusion boundary layer (DBL) – a region within which the movement of mass (for example, dissolved carbon and nutrients) is by molecular diffusion (Hurd et al., 2014). In situations where flow speeds are slow (<0.2 m s–1), the DBL restricts the passage of essential dissolved substances to and from the seaweed surface (Hurd, 2015, 2017). When seaweeds grow in a canopy, the VBLs coalesce to form a canopy boundary layer (Cornwall et al., 2015). The result is that turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) and flow speed within seaweed beds are strongly attenuated (see Table 1; Kregting et al., 2011).

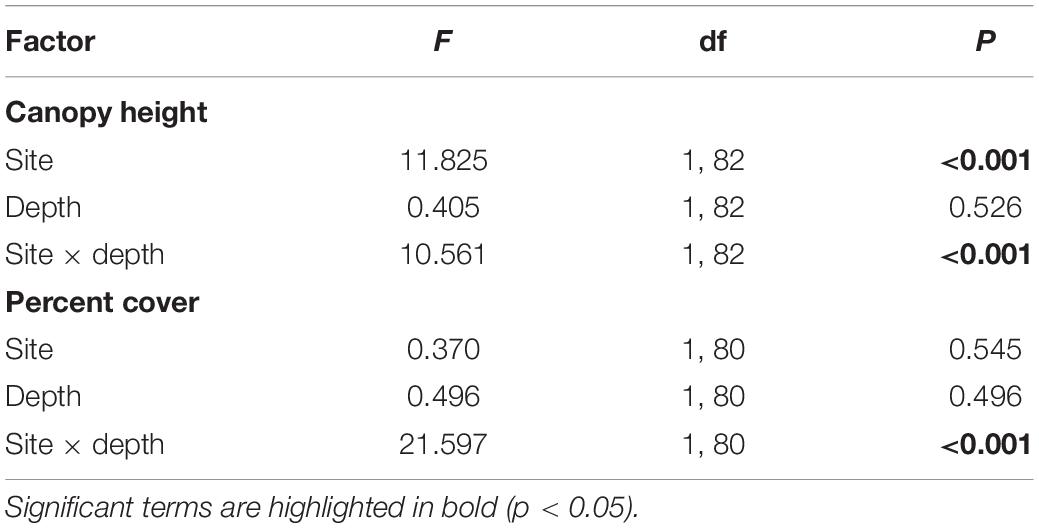

Table 1. Three-way ANOVA of the effects of site (Ninepin Point and Tinderbox), depth (3 and 6 m) and height (within canopy and above canopy) on square root transformed factors flow speed and TKE.

The interaction between macroalgal canopies and water flow is poorly understood. Very few measurements in the field at the scale relevant to DBL processes exist (Kregting et al., 2011; Nishihara et al., 2011). Acoustic Doppler current profilers (ADCPs) or electromagnetic current meters (ECMs) have been used successfully in field measurements of flow profiles throughout the water column or background flow (Neushul et al., 1992; Rosman et al., 2007; Kregting et al., 2013; Millar et al., 2020), however, they do not capture the scales important to DBL formation. More appropriate is the use of acoustic Doppler velocimeters (ADVs) which have been used extensively in laboratory and field investigations to measure fine scale flow profiles within and above seagrass beds (e.g., Grizzle et al., 1996; Koch and Gust, 1999; Cornelisen and Thomas, 2004; Abdolahpour et al., 2017; Monismith et al., 2019), coral reefs (e.g., Reidenbach et al., 2006; Falter et al., 2007; Hench and Rosman, 2013; van Rooijen et al., 2020), yet only once in a homogenous subtidal macroalgal canopy (Kregting et al., 2011).

Understanding flows in macroalgal canopies is fundamental to our understanding of how canopies modulate velocity and turbulence. This knowledge is becoming increasingly important as macroalgal beds are considered as refugia for calcifying organisms from ocean acidification (OA) (Hurd, 2015; Wahl et al., 2018). OA is causing the saturation state of carbonate (Ω) to decline, making calcifying organisms increasingly vulnerable to dissolution (Hurd et al., 2018). Uptake of inorganic carbon by seaweeds during photosynthesis causes seawater pH and Ω to increase, making conditions more favorable for calcification. The metabolic buffering of the seawater carbonate system is considered important in protecting sensitive calcifying invertebrates including shellfish and bryozoans from OA (Noisette and Hurd, 2018). For example, coralline algae subjected to OA grew and calcified faster in zero flow compared to “fast” flows of 0.05 m s–1 due to reduced dissolution, and the reduction of flow in overstory canopies enabled coralline algae to locally raise pH (Cornwall et al., 2014). Therefore, knowledge of seawater flows in natural environments at the scales relevant to DBL is central to understanding how canopies may provide a refuge for calcifying marine organisms including coralline algae, shellfish, and sea urchins, that live within seaweed beds.

Along many coastlines globally, wave sheltered habitats occur where extensive macroalgal “gardens” exist. Macroalgae have considerable interspecific variation of shapes, sizes, and rigidity which interact with the fluid flow. Here we present results of the flows measured within and above natural heterogenous macroalgal communities at two subtidal sites in Tasmania, Australia, in relation to canopy height and percent cover. These sites were chosen as earlier studies indicated differences in the seaweed communities due to differences in the light availability at each site (Barrett et al., 2009). Using ADVs, the campaign was designed to capture variability of flow speed within and above the canopies measured over a range of tidal states. We hypothesized that within canopies, flow would be significantly reduced compared to above canopies, irrespective of depth and the unique species composition of each site. We present data on how macroalgal assemblages’ moderate flows in natural conditions. This knowledge is fundamental to inform laboratory studies as to the characteristic speeds and turbulence associated within and above canopies of subtidal macroalgal canopies in inshore coastal habitats.

Materials and Methods

Study Sites

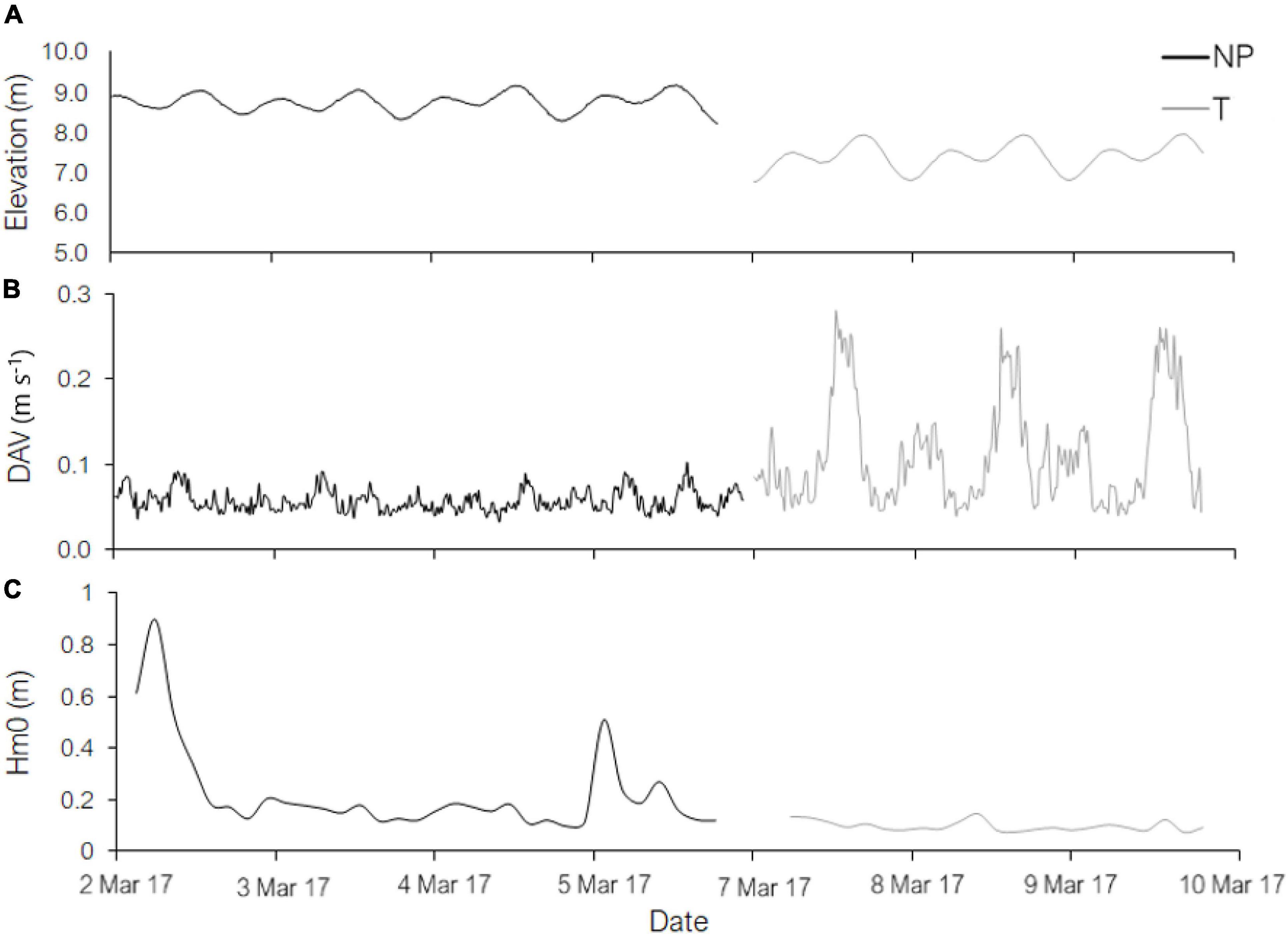

Velocity measurements within and above heterogenous subtidal macroalgal canopies were carried out at two sites in Tasmania, Australia: Ninepin Point Marine Reserve (S43°16′38.222 E147°11′16.86) from the 2nd to the 6th March, 2017 (hereafter Ninepin Point) and Tinderbox Nature Reserve (S43°03′30.722 E147°19′52.583) from the 7th to the 9th March, 2017 (hereafter Tinderbox). Both sites experience mixed semidiurnal tides with a tidal elevation of approximately 1 m (Figure 1). Ninepin Point is located within the D’Entrecasteaux Channel and is slight to moderately exposed to the South Pacific Ocean. It has a tannin rich freshwater input from the nearby Huon River restricting light penetration, enhancing red species abundance (Barrett et al., 2009). Tinderbox is also moderately sheltered from wave activity and located near the D’Entrecasteaux Channel providing a weak current (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Time series of (A) surface elevation, (B) depth averaged velocities (DAV), and (C) significant wave height (Hm0) at Ninepin Point (NP) (March 2nd – 6th, 2017) and Tinderbox Nature Reserve (T) (March 7th – 10th, 2017) recorded with an Acoustic Doppler Current Profiler (ADCP).

Velocity Within and Above the Canopy

Surveys of background (1.5 m above the substrate) and boundary (<0.01 m above the substrate) velocity measurements were obtained concurrently with two flexible stem ADV (Nortek AS, Norway) that captured the horizontal u, lateral v and vertical w velocity components. The ADV instruments were attached to a frame with adjustable legs to accommodate substrate irregularities and that could be easily maneuvered via SCUBA over a 20 m transect parallel to the shore. The frame ensured that the background probe remained at the same height for each measurement. The boundary probe could be moved vertically on an adjustable stem by a diver to the required position with the ADV sample volume located 0.15 m from the probe head occupying an area of 14.9 mm3. As there were uncertainties as to the exact height above the substrate that samples were being measured, velocity data were recorded at three heights measured with a ruler at ∼0.01, 0.02, and 0.03 m above the substrate to ensure that at least one sample was useable with no boundary proximity interference (Voulgaris and Trowbridge, 1998).

Owing to logistics such as dive time constraints, at each height above the substrate velocity data were recorded at 32 Hz for 5 min (9600 samples per record) to capture the largest turbulent length scale. Instrument alignment and movement were checked at each new location along with placement in relation to the direction of the flow to ensure no interference from the test legs on the recordings. At both sites, two depths were sampled, ∼3 and ∼6 m, representing the deepest and mid depths of macroalgal canopies up to ∼50 m offshore. Three or four locations were sampled at each depth and site combination. Tidal elevation differences were taken into account when selecting the sampling locations between days and dives. The maximum difference in tidal elevation between dives were 0.4 and 0.5 m for Ninepin Point and Tinderbox, respectively.

To determine background current profiles and significant wave height (Hm0) during the measurement campaign at each site, one ADCP (Nortek Aquadopp, 1 MHz; Nortek AS, Norway) was deployed approximately 100 m offshore at 8 and 7 m MLW depth in Ninepin Point and Tinderbox, respectively. The ADCP recorded flow velocity every 900 s with a burst length of a 120 s which was averaged at a vertical bin resolution of 0.3 m. To measure Hm0, measurements were made every 3 h recording 2048 readings at 2 Hz.

Macroalgal Canopy Characterization

To understand how canopy height and assemblages may alter turbulence and flow speed within and above the canopies, surveys of the canopy height and percentage cover were carried out using SCUBA. Canopy height and percentage cover of the understory was recorded in haphazardly placed quadrats (0.50 m × 0.50 m) along the 3 and 6 m depth contours. In each quadrat, three measurements of canopy height using a ruler to the nearest cm were taken. Measurements were made in as many quadrats as possible in the time taken for the first diver to undertake water velocity measurements (Tinderbox: 3 m = 21, 6 m = 24; Ninepin: 3 m = 20, 6 m = 21). Since both sites are in a Marine Reserve and collections was not permitted, photos were taken of each quadrat and percentage cover was calculated for the functional groups of: filamentous, foliose, leathery canopy forming, crustose coralline algae (CCA) and bare substratum. Species were grouped into functional groups because it is thallus morphology that is important in generating and influencing water motion, as opposed to species composition per se (Hurd and Stevens, 1997). Percentage cover estimates were calculated from identifying the functional group at 20 randomly allocated points using the software CoralNet (Beijbom et al., 2015). At Tinderbox only, a Sargassum sp. created a natural overstory canopy of which the height to the nearest 0.1 m and density (in seven 1 m2 quadrats) were also recorded.

Data Analysis

Velocity

All raw data were quality checked before flow parameters were calculated. Spikes were removed following 3D phase space threshold techniques and values with correlations <70 and signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) <15 were removed following the method of Goring and Nikora (2002). Only recordings with more than 70% of the values remaining were used for the analysis (Martin et al., 2002). The hydrodynamic quantities resolved from the ADV velocity data to compare to previous field and flume studies (Kregting et al., 2008, 2011; Noisette and Hurd, 2018) include speed (U) and TKE. Mean speed was computed from the three velocity components uu, uv, and uw as: and TKE = 0.5 (u′2 + v′2 + w′2) where u is the mean and u′ the SD of the original time trace. Comparison of speed and TKE as a function of site (Ninepin Point and Tinderbox), depth (3 and 6 m) and height (within canopy and above canopy) was carried out using a three-way ANOVA. When significant differences in the interaction were detected, treatments were compared using Tukey’s honestly significantly different (THSD) post hoc tests. Power spectral density (PSD) were computed using Welch’s method (Priestley, 1981).

Canopy Height and Percentage Cover

Comparison of the understory height and total percentage cover (n = 21–24 – see above) as a function of site (Ninepin Point and Tinderbox) and depth (3 and 6 m) was carried out using a two-way ANOVA. When significant differences in the interaction were detected, treatments were compared using THSD post hoc tests. Comparison of the overstory height and overstory density at Tinderbox only as a function of depth (3 and 6 m) was carried out using a one-way ANOVA. Normality of residuals was assessed by inspecting normal Q–Q plots and the assumption of homoscedasticity was confirmed by inspecting residual vs fitted plots. Total percentage cover required a transformation of Y1.3. No other variables required transformations. Analyses were performed in R. V. 3.6 (R Core Team, 2019).

Results

Hydrodynamic Characteristics at Each Site

At Ninepin Point, depth averaged flow speeds fluctuated between 0.04 and 0.08 m s–1 compared to 0.05 and 0.28 m s–1 observed at Tinderbox which were dependent on tidal state (Figure 1). Significant wave height (Hm0) was generally slight at both sites during the experimental period with a maximum Hm0 of 0.9 m recorded at Ninepin Point and 0.1 m at Tinderbox. Mean period (Tm02) at Ninepin Point was on average 5 s with minimum and maximum frequencies of 3 and 7.6 s, respectively, while Tinderbox mean period was 4.5 s with minimum and maximum frequencies of 3 and 6.7 s, respectively recorded (data not shown).

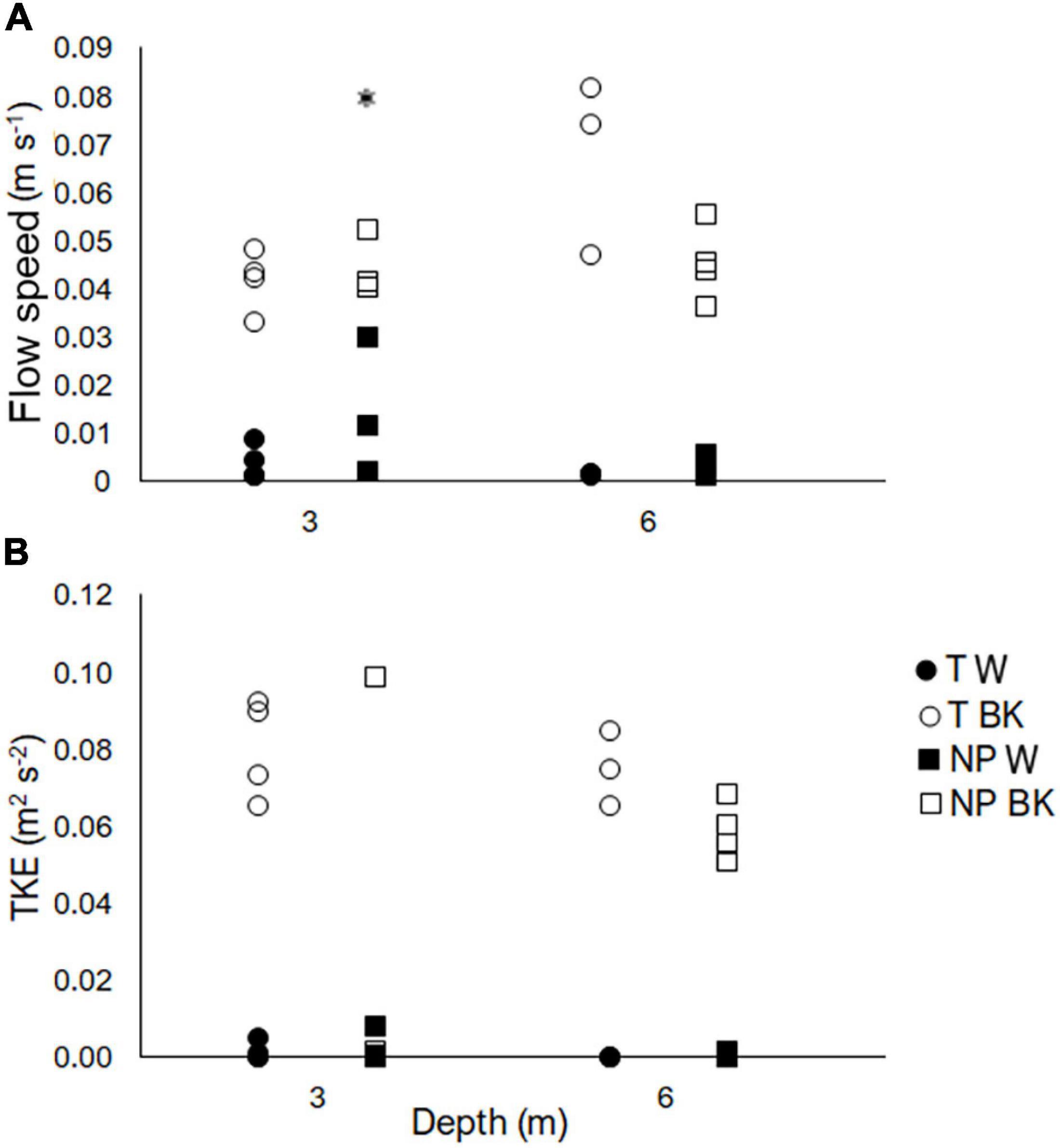

Flow speeds within the canopies were significantly lower than background flow speeds (Table 1). Irrespective of background flows, depth or site, flow speeds recorded within the canopy were <0.03 m s–1 (Figure 2A). The lowest speeds of <0.01 m s–1 were recorded within the macroalgal canopies at Tinderbox resulting in a >90% reduction of flow compared to above the canopy. Faster flows within the canopy at 3 m at Ninepin Point drove the significant interactions observed between site and height, and depth and height, as indicated by the pair-wise comparisons (Figure 2A and Table 1). Background flow speeds measured 1.5 m above the substrate ranged between 0.03 and 0.08 m s–1 (Figure 2A).

Figure 2. Flow speed (A) and turbulent kinetic energy (TKE) (B) measured within the canopy (W) and background (BK) at Ninepin Point (NP) and Tinderbox (T) and at two depths, 3 and 6 m. Circles refer to individual measurements at Tinderbox and squares refer to individual measurements at Ninepin Point. Filled points are measurements within the canopy and open points refer to the background. N = 3–4 for each site and canopy or background combination. Measurements were carried out during the period March 2nd – 9th, 2017. Asterisk denotes significant difference of within canopy measurements only between site and depth (LSD), P < 0.05.

Although TKE was similar between sites, significant differences were observed within and above canopies (3 or 6 m) and an interactive effect was found between site and depth (Figure 2B and Table 1). In general, TKE was 1.0 × 10–4 to 5.0 × 10–3 m2 s–2 within the macroalgal canopies at Ninepin Point and Tinderbox, which was up to two orders of magnitude lower than that above the canopies (Figure 2B and Table 1). Depth only influenced the level of turbulence at Ninepin Point, with higher levels of TKE generated at 3 compared to 6 m.

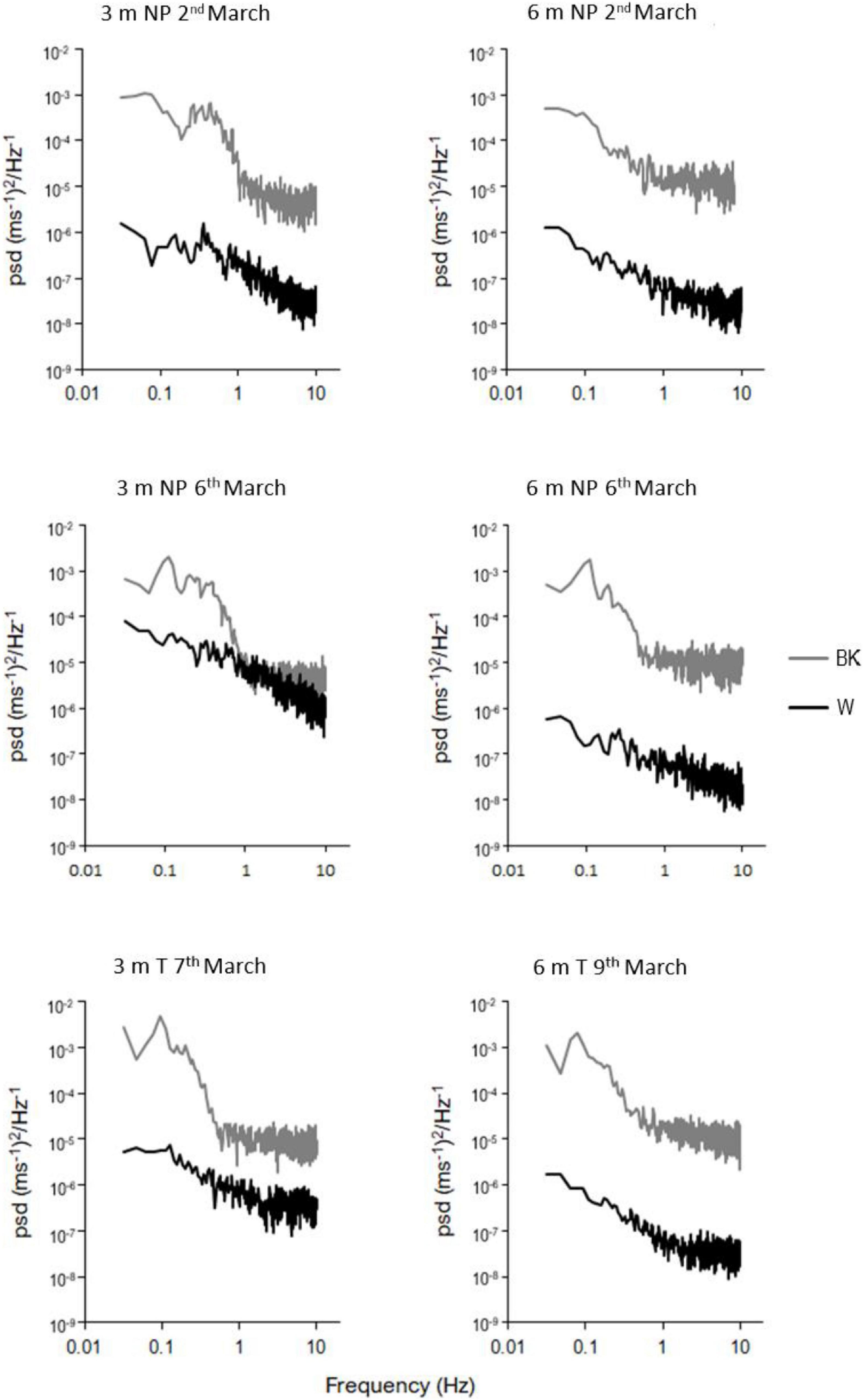

The outer-canopy spectra for each site and depth combination (Figure 3) showed similar levels of energy. Ninepin Point on the 6th March and Tinderbox on the 7th March showed frequency peaks at approximately 0.1 Hz indicative of a wave period of 10 s. At the shallower depth of 3 m, the spectra revealed some variation between 0.3 and 0.5 Hz (2–5 s), particularly at Ninepin Point. The inner-canopy spectra were approximately 2–3 orders of magnitude lower than the background spectra with no defined frequency peaks identified (Figure 3).

Figure 3. A selection of power spectral density (PSD) plots of speed (U) for background (BK) and within canopy (W) measurements at 3 and 6 m depth at Ninepin Point (NP) Tinderbox (T).

Macroalgal Canopy Characterization

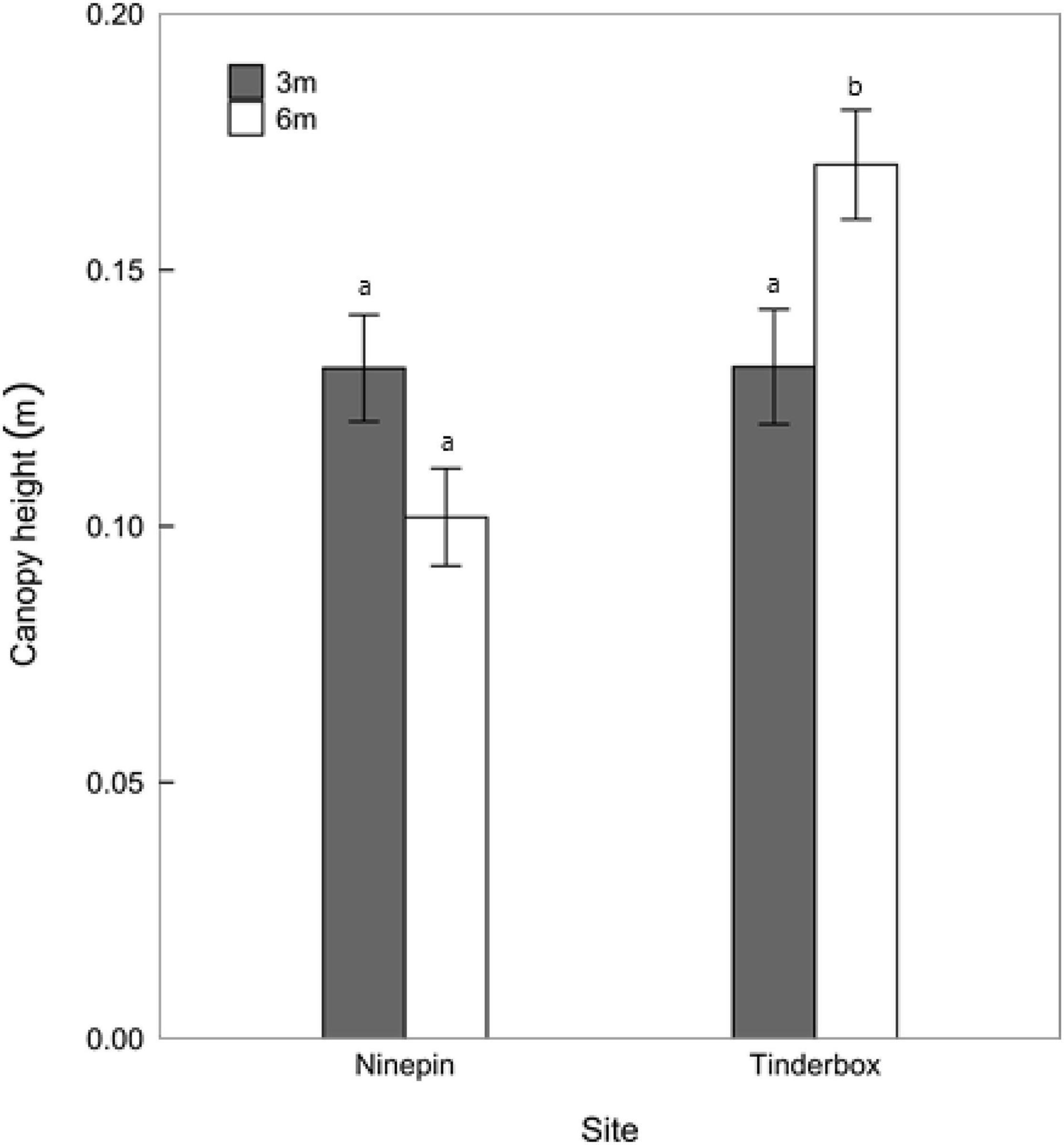

Understory canopy height was dependent on site and depth (Figure 4 and Table 2). At both sites, macroalgae growing at 3 m exhibited similar canopy heights of ∼0.13 m. Macroalgae growing at 6 m at Ninepin Point were similar in height to seaweeds growing at 3 m. However, for Tinderbox at 6 m, the average canopy height (0.17 m) was significantly higher than any of the other site × depth combinations (Figure 4 and Table 2). The average height of the overstory canopy at Tinderbox was 0.7 m and did not differ significantly between depths (F1,12 = 1.85, p = 0.199). The density at each depth was different with twice the number of Sargassum sp. verruculosum individuals at 3 m with an average of 4 individuals m2 compared to 2 individuals m2 at 6 m (F1,12 = 17.76, p = 0.0012).

Figure 4. Canopy heights at Ninepin Point and Tinderbox at two depths, 3 and 6 m. n = 20–24 ±SE. Letters denote significant difference of canopy height between sites and depth (LSD), P < 0.05.

Table 2. Two-way ANOVA of the effects of site (Ninepin Point and Tinderbox) and depth (3 and 6 m) on the factors canopy height and percent macroalgal cover.

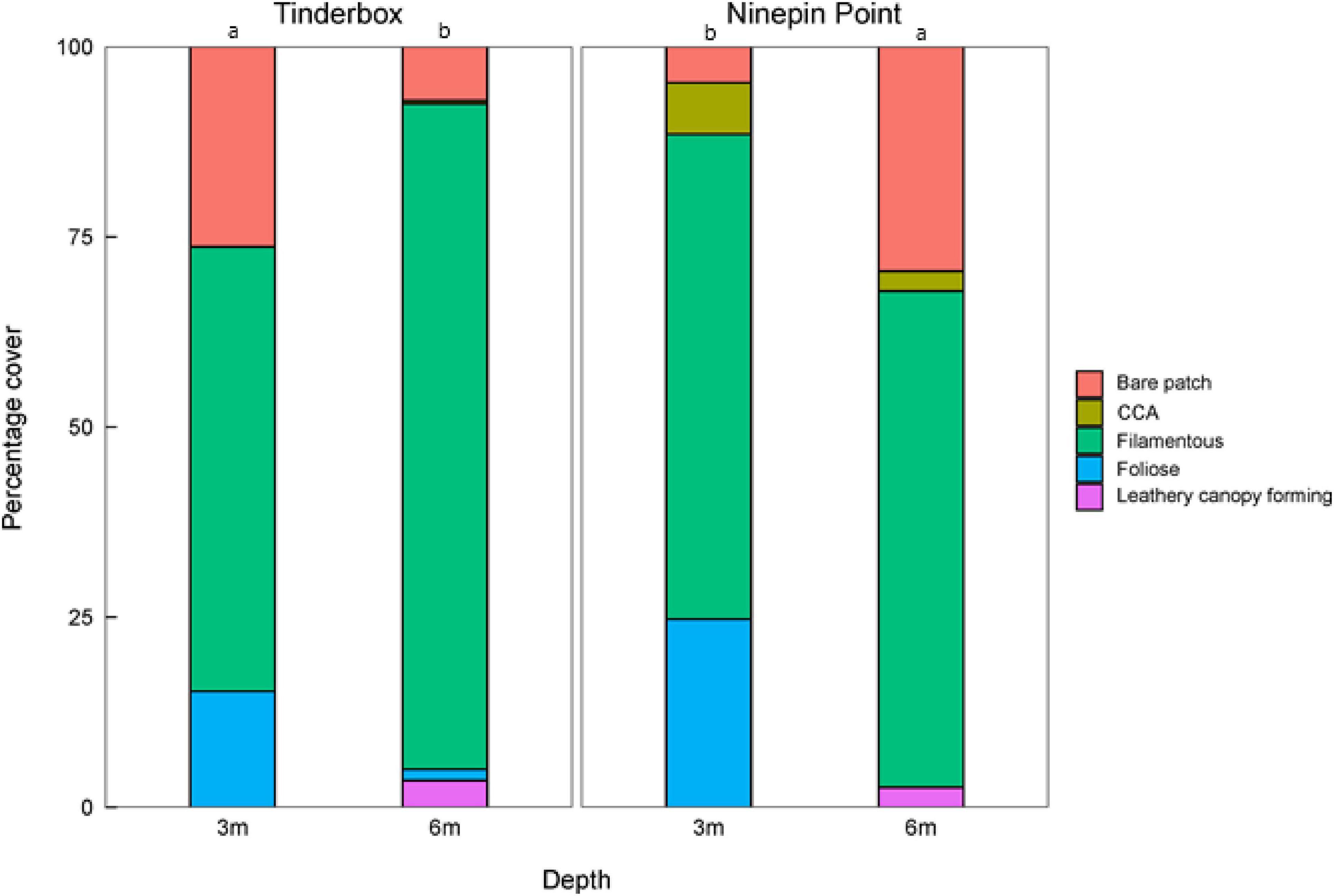

A mixture of foliose, filamentous, leathery canopy-forming seaweeds, and CCA were present at both sites and depths (Figure 5). There was a significant interactive effect of site and depth on percentage cover with a higher percentage cover at 6 m relative to 3 m at Tinderbox, while the opposite pattern was observed at Ninepin Point (Figure 5 and Table 2). Filamentous groups made up the highest proportion of seaweeds at each site covering up to 75% of the substrate irrespective of site or depth. Foliose seaweeds were more abundant at shallower depths, representing up to 25% of the cover. Crustose coralline algae predominantly occurred at Ninepin Point covering approximately 5% at both depths. The cover of macroalgae at both sites was interspersed with bare unvegetated patches that varied between 10 and 25% of the cover.

Figure 5. Proportion of cover of bare substrate, crustose coralline algae (CCA), filamentous, foliose, and leathery canopy forming macroalgae at Ninepin Point and Tinderbox at two depths, 3 and 6 m. Note that cover equates to the percentage of the understorey canopy macroalgae only. Letters denote significant difference of percent cover of macroalgae between sites and depth (LSD), P < 0.05.

Discussion

Modulation of background flow speed and turbulence within macroalgal canopies is fundamental to our understanding of nutrient supply and removal to and from seaweed surfaces. In addition, flow modulation in these systems has the potential to act as a “physiological” refuge for calcifying organisms. As hypothesized, we show that natural canopies can dampen background flow and turbulence by 70–90%, and that flow speeds and TKE within the seaweed assemblages were negligible at U < 0.03 m s–1 and TKE < 0.008 m2 s–2. The flow speed patterns were similar at both sites irrespective of the different algal morphologies, the depth at which the macroalgal canopies were situated and background flow rates, although elevated turbulence was observed within the canopy at 3 compared to 6 m. Studies quantifying flow speed above and within macroalgal canopies at scales relevant to DBL are rare, and our results are an advance in quantifying flow and turbulence within heterogenous macroalgal beds at different depths and sites.

The difference in flow parameters (speed and TKE) observed within the canopies in our study is likely to be driven by bio-physical interactions. More variability in flow speed and TKE within the canopy was observed at 3 m, coinciding with more foliose seaweed groups growing at these depths. It is difficult to disentangle if the increase in energy within the canopies at the shallow depths reflected the morphology of seaweeds, or if energy from wind waves were attenuating within the canopy, particularly at Ninepin Point. Wave energy can drive more flow inside a canopy than expected from current alone (Lowe et al., 2007), with the level of in-canopy flow dependent on blade morphology and density (Lowe et al., 2005). Although slight, wave energy was present at Ninepin Point, with a significant wave height of 0.1 m on average and a mean period of ∼4 s during the sampling period. Using Airy linear wave theory (Airy, 1845) this equates to a horizontal velocity of approximately 0.06 m s–1 at 3 m, a value observed above the canopy, but not to the same extent within the canopy. This suggests that some energy was able to penetrate within the canopy. However, there was also no overstory canopy of Sargassum sp. at Ninepin Point which will act to dampen background flow via drag (e.g., Jackson and Winant, 1983; Gaylord et al., 2007). Therefore, further experimental work is required to elucidate how canopies of similar functional groups modify flow and turbulence under oscillatory flow conditions. The results, however, highlight the complexity of flows within canopies are driven by both physical and biological factors.

The rate of transport of dissolved chemicals to and from a seaweed surface is partly driven by the thickness of the DBL which is controlled by flow speed at the blade surface (Stevens et al., 2001). Ideally, flow rates measured directly at the blade surface in situ are needed for understanding DBL formation to relate to physiological processes. However, in the natural setting of coastal environments, it is logistically impossible to measure DBL formation as the macroalgal assemblages are comprised of a range of functional groups including foliose, filamentous, leathery and crustose, as measured in this study. Each individual thallus has its own rugosity, rigidity, and VBL which will “trip” the transition from laminar to turbulent flow at different flow velocities (Hurd and Stevens, 1997). These features create variation in flow structures within the assemblage creating a range of scales of motion generated by the different morphologies (Hurd and Stevens, 1997). Collectively, as the macroalgae grow in a canopy, the VBLs coalesce to form the canopy boundary layer (Cornwall et al., 2015). To best capture how seaweeds modulate flow, we therefore measured flow speeds and turbulence within and above the canopies. Similar to Kregting et al. (2011), who measured >95% flow reduction within a homogenous canopy at one depth, the flow speeds and turbulence in this study were significantly dampened in the heterogenous canopies (70–90%). This degree of attenuation was greater than salt marsh plants (e.g., Leonard and Croft, 2006) and M. pyrifera beds (e.g., Rosman et al., 2007) but similar to seagrass and freshwater macrophytes (see Table 1; Kregting et al., 2011) suggesting that within these canopies, thick DBLs are likely to form.

Slow-flow marine environments such as natural harbors, embayment’s and enclosed seas where speeds are <0.2 m s–1 are very common in coastal regions both spatially (horizontally and vertically) and temporally (e.g., Jackson and Winant, 1983; Carpenter and Williams, 1993; Gaylord et al., 2007; Kregting et al., 2011). Background flow rates may also vary appreciably over spatial scales as small as 50–100 m as indicated by the 0.2 m s–1 difference between the ADCP measurements taken ∼50 m from the 6 m sites located nearest the channel and background measurements at the sampling sites. Flow regimes near shore are naturally heterogenous as a result of tidally driven, bathymetry-induced physical processes and smaller scale benthic structural complexity by rocks and organisms (Ferrier and Carpenter, 2009; Kregting et al., 2016). In addition, the rate of flow is continuously variable as tides ebb and flood during spring and neap tides (Kregting et al., 2013). How many coastlines globally experience similar flows to the ones in this study will become clearer in time. Tools such as the use of hydrodynamic models linked with macroalgal distribution will help speed up our understanding.

Although mean flow speeds will be the same in both laboratory flume and field measurements, the level of turbulence at the same mean speeds may be lower in the flume than in the field (Jonsson et al., 2006; Kregting et al., 2011). The thickness of the DBL will be controlled in part by environmental roughness and flow speed with increases in TKE reducing the thickness of the DBL (Schlichting, 1979). Higher levels of turbulence will therefore be beneficial for mixing and transport of dissolved carbon and nutrients. In the field, TKE was up to two orders of magnitude higher above the canopy than within the canopy, a result similar to coral reef environments (Reidenbach et al., 2006) and intertidal Sargassum canopies (Nishihara et al., 2011). However, TKE can be lower in flume studies than the field as flumes are specifically designed to generate steady flow (Hurd et al., 1994). Whether TKE is at the correct scale for laboratory studies assessing flow and metabolic processes for seaweeds is unknown. Consequently, further research should incorporate the importance of suitable scaling of turbulent parameters in the flume considering the importance of this characteristic in understanding DBL formation.

Knowledge of seawater flows and TKE in natural populations are rare but they are important to understand the extent to which a seaweed canopy might act as an important refugia for calcifying organisms (e.g., coralline algae, mussels, and urchins) from future OA (Hurd et al., 2011; Hurd, 2015; Noisette and Hurd, 2018; Wahl et al., 2018). This is because seaweeds have a twofold effect on the sub-canopy biochemical environment. The presence of the canopy reduces flow (above), but also locally raises the pH of the seawater via photosynthesis. This high pH seawater can be retained within a canopy at slow-moderate flows, but will dissipate at high flow speeds (Cornwall et al., 2015). Under future conditions of OA, coralline algae maintained net calcification under zero flow (but regular seawater exchange) compared to flows of 0.05 m s–1 (Cornwall et al., 2014), suggesting that elevated pH in macroalgal canopies under low flows during daylight may be beneficial to calcifying species (Hurd, 2015). However, often overlooked is the fact that the inverse occurs during the night, with reductions in pH driven by community respiration. Dissolution of calcareous structures can occur in dark conditions for coralline algae (Noisette et al., 2013; Reyes-Nivia et al., 2014). This phenomenon is likely to be exacerbated by OA particularly under slow flows, such as those presented here. Moreover, fluctuations in pH are likely to be higher, which has varied effects on calcifying species (e.g., Eriander et al., 2016; Wahl et al., 2016).

Summary

Flow modulation by macroalgal canopies may be viewed as a “double edged sword” (Wheeler, 1988) for the productivity of the macroalgae and the calcifying organisms living within the canopies. Undeniably, the thicker the DBL, the more restrictive the passage of essential dissolved substances to and from the seaweed surface (Hurd, 2015, 2017). As such, slow flow speeds over seaweed blades have long been considered as negative for processes such as nutrient uptake and carbon acquisition (Hurd, 2000). However, there is a growing body of evidence that for sensitive calcifying invertebrates and coralline algae, this area of low flow offers protection from OA. The chemical complexity within the canopy and at the blade surface is beyond the scope of this research but the flow speeds measured within the canopies in this study provide supporting evidence that these underwater marine gardens may provide periods of refuge for calcified species under increased OA.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation.

Author Contributions

LK, DB, CM, and CH designed the study. LK and DB carried out the experiment and undertook the data analysis. All authors contributed to the drafting of the manuscript.

Funding

LK was supported by a Visiting Scholarship from University of Tasmania, Australia, a Queen’s University Belfast Research Fellowship from Queen’s University Belfast, United Kingdom, and EPSRC research grant EP/S000747/1. DB was supported by a University of Tasmania, Australian Postgraduate Award.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We particularly like to thank Ellie Paine and Victor Shellamoff for their assistance in the field and Pál Schmitt for his helpful comments on the manuscript.

References

Abdolahpour, M., Hambleton, M., and Ghisalberti, M. (2017). The wave-driven current in coastal canopies. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 122, 3660–3674. doi: 10.1002/2016JC012446

Barrett, N. S., Buxton, C. D., and Edgar, G. J. (2009). Changes in invertebrate and macroalgal populations in Tasmanian marine reserves in the decade following protection. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 370, 104–119. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2008.12.005

Beijbom, O., Edmunds, P. J., Roelfsema, C., Smith, J., Kline, D. I., Neal, B. P., et al. (2015). Towards automated annotation of benthic survey images: variability of human experts and operational modes of automation. PLoS One 10:e0130312. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0130312

Carpenter, R. C., and Williams, S. L. (1993). Effects of algal turf canopy height and microscale substratum topography on profiles of flow speed in a coral forereef environment. Limnol. Oceanogr. 38, 687–694. doi: 10.4319/lo.1993.38.3.0687

Cornelisen, C. D., and Thomas, F. I. M. (2004). Ammonium and nitrate uptake by leaves of the seagrass Thalassia testudinum: impact of hydrodynamic regime and epiphyte cover on uptake rates. J. Mar. Syst. 49, 177–194. doi: 10.1016/j.jmarsys.2003.05.008

Cornwall, C. E., Boyd, P. W., McGraw, C. M., Hepburn, C. D., Pilditch, C. A., Morris, J. N., et al. (2014). Diffusion boundary layers ameliorate the negative effects of ocean acidification on the temperate coralline macroalga Arthrocardia corymbosa. PLoS One 9:e97235. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097235

Cornwall, C. E., Pilditch, C. A., Hepburn, C. D., and Hurd, C. L. (2015). Canopy macroalgae influence understorey corallines’ metabolic control of near-surface pH and oxygen concentration. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 525, 81–95. doi: 10.3354/meps11190

Eriander, L., Wrange, A. L., and Havenhand, J. N. (2016). Simulated diurnal pH fluctuations radically increase variance in-but not the mean of-growth in the barnacle Balanus improvisus. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 73, 596–603. doi: 10.1093/icesjms/fsv214

Falter, J. L., Atkinson, M. J., Lowe, R. J., Monismith, S. G., and Koseff, J. R. (2007). Effects of nonlocal turbulence on the mass transfer of dissolved species to reef corals. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 274–285. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.1.0274

Ferrier, G. A., and Carpenter, R. C. (2009). Subtidal benthic heterogeneity: flow environment modification and impacts on marine algal community structure and morphology. Biol. Bull. 217, 115–129. doi: 10.1086/BBLv217n2p115

Gaylord, B., Rosman, J. H., Reed, D. C., Koeseff, J. R., Fram, J., MacIntyre, S., et al. (2007). Spatial patterns of flow and their modification within and around a giant kelp forest. Limnol. Oceanogr. 52, 1838–1852. doi: 10.4319/lo.2007.52.5.1838

Goring, D. G., and Nikora, V. I. (2002). Despiking acoustic doppler velocimeter data. J. Hydraul. Eng. 128, 117–126. doi: 10.1061/(ASCE)0733-94292002128:1(117)

Grizzle, R., Short, F. T., Newell, C. R., Hoven, H., and Kindblom, L. (1996). Hydrodynamically induced synchronous waving of seagrasses:’monami’and its possible effects on larval mussel settlement. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 206, 165–177.

Hench, J. L., and Rosman, J. H. (2013). Observations of spatial flow patterns at the coral colony scale on a shallow reef flat. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 118, 1142–1156. doi: 10.1002/jgrc.20105

Hurd, C. L. (2000). Water motion, marine macroalgal physiology, and production. J. Phycol. 36, 453–472. doi: 10.1046/j.1529-8817.2000.99139.x

Hurd, C. L. (2015). Slow-flow habitats as refugia for coastal calcifiers from ocean acidification. J. Phycol. 51, 599–605. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12307

Hurd, C. L. (2017). Shaken and stirred: the fundamental role of water motion in resource acquisition and seaweed productivity. Perspect. Phycol. 4, 73–81. doi: 10.1127/pip/2017/0072

Hurd, C. L., and Stevens, C. L. (1997). Flow visualization around single-and multiple-bladed seaweeds with various morphologies. J. Phycol. 33, 360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1997.00360.x

Hurd, C. L., Cornwall, C. E., Currie, K., Hepburn, C. D., McGraw, C. M., Hunter, K. A., et al. (2011). Metabolically induced pH fluctuations by some coastal calcifiers exceed projected 22nd century ocean acidification: a mechanism for differential susceptibility? Global Change Biol. 17, 3254–3262. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2486.2011.02473.x

Hurd, C. L., Harrison, P. J., Bischof, K., and Lobban, C. S. (2014). Seaweed Ecology And Physiology. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. doi: 10.1017/CBO9781139192637

Hurd, C. L., Lenton, A., Tilbrook, B., and Boyd, P. W. (2018). Current understanding and challenges for oceans in a higher-CO2 world. Nat. Clim. Change 8, 686–694. doi: 10.1038/s41558-018-0211-0

Hurd, C. L., Quick, M., Stevens, C. L., Laval, B. E., Harrison, P. J., and Druehl, L. D. (1994). A low-volume flow tank for measuring nutrient uptake by large macrophytes. J. Phycol. 30, 892–896. doi: 10.1111/j.0022-3646.1994.00892.x

Jackson, G., and Winant, C. (1983). Effect of a kelp forest on coastal currents. Cont. Shelf Res. 2, 75–80. doi: 10.1016/0278-4343(83)90023-7

Jonsson, P. R., van Duren, L., Amielh, M., Asmus, R., Aspden, R. J., Daunys, D., et al. (2006). Making water flow: a comparison of the hydrodynamic characteristics of 12 different benthic biological flumes. Aquat. Ecol. 40, 409–438. doi: 10.1007/s10452-006-9049-z

Koch, E. W., and Gust, G. (1999). Water flow in tide- and wave-dominated beds of the seagrass Thalassia testudinum. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 184, 63–72.

Kregting, L. T., Hepburn, C. D., and Savidge, G. (2015). Seasonal differences in the effects of oscillatory and uni-directional flow on the growth and nitrate-uptake rates of juvenile Laminaria digitata (Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol. 51, 1116–1126. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12348

Kregting, L. T., Hurd, C. L., Pilditch, C. A., and Stevens, C. L. (2008). The relative importance of water motion on nitrogen uptake by the subtidal macroalga Adamsiella chauvinii (Rhodophyta) in winter and summer. J. Phycol. 44, 320–330. doi: 10.1111/j.1529-8817.2008.00484.x

Kregting, L. T., Stevens, C. L., Cornelisen, C. D., Pilditch, C. A., and Hurd, C. L. (2011). Effects of a small-bladed macroalgal canopy on benthic boundary layer dynamics: implications for nutrient transport. Aquat. Biol. 2011, 41–56. doi: 10.3354/ab00369

Kregting, L., Blight, A., Elsäßer, B., and Savidge, G. (2013). The influence of water motion on the growth rate of the kelp Laminaria hyperborea. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 448, 337–345. doi: 10.1016/j.jembe.2013.07.017

Kregting, L., Elsäßer, B., Kennedy, R., Smyth, D., O’Carroll, J., and Savidge, G. (2016). Do changes in current flow as a result of arrays of tidal turbines have an effect on benthic communities? PLoS One 11:e0161279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0161279

Leonard, L. A., and Croft, A. L. (2006). The effect of standing biomass on flow velocity and turbulence in Spartina alterniflora canopies. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci. 69, 325–336.

Lowe, R. J., Falter, J. L., Koseff, J. R., Monismith, S. G., and Atkinson, M. J. (2007). Spectral wave flow attenuation within submerged canopies: implications for wave energy dissipation. J. Geophys. Res 112:C05018. doi: 10.1029/2006JC003605

Lowe, R. J., Koseff, J. R., and Monismith, S. G. (2005). Oscillatory flow through submerged canopies: 1. Velocity structure. J. Geophys. Res. 110:C10016. doi: 10.1029/2004JC002788

Martin, V., Fisher, T. S., Millar, R. G., and Quick, M. C. (2002). “ADV data analysis for turbulent flows: low correlation problem,”in Conference on Hydraulic Measurements and Experimental Methods Specialty Conference (HMEM), 2002, 1–10. doi: 10.1061/406552002101

Millar, R. V., Houghton, J. D., Elsäβer, B., Mensink, P. J., and Kregting, L. (2020). Influence of waves and currents on the growth rate of the kelp Laminaria digitata (Phaeophyceae). J. Phycol. 56, 198–207. doi: 10.1111/jpy.12943

Monismith, S. G., Hirsh, H., Batista, N., Francis, H., Egan, G., and Dunbar, R. B. (2019). Flow and drag in a seagrass bed. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 124, 2153–2163. doi: 10.1029/2018JC014862

Neushul, M., Benson, J., Harger, J. B. W., and Charters, A. C. (1992). Macroalgal farming in the sea: water motion and nitrate uptake. J. Appl. Phycol. 4, 255–265. doi: 10.1007/BF02161211

Nishihara, G. N., Terada, R., and Shimabukuro, H. (2011). Effects of wave energy on the residence times of a fluorescent tracer in the canopy of the intertidal marine macroalgae. Sargassum fusiforme (Phaeophyceae). Phycol. Res. 59, 24–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1835.2010.00595.x

Noisette, F., and Hurd, C. L. (2018). Abiotic and biotic interactions in the diffusive boundary layer of kelp blades create a potential refuge from ocean acidification. Funct. Ecol. 32, 1329–1342. doi: 10.1111/1365-2435.13067

Noisette, F., Egilsdottir, H., Davoult, D., and Martin, S. (2013). Physiological responses of three temperate coralline algae from contrasting habitats to near-future ocean acidification. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 448, 179–187.

R Core Team (2019). R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria.

Reidenbach, M. A., Monismith, S. G., Koseff, J. R., Yahel, G., and Genin, A. (2006). Boundary layer turbulence and flow structure over a fringing coral reef. Limnol. Oceanogr. 51, 1956–1968. doi: 10.4319/lo.2006.51.5.1956

Reyes-Nivia, C., Diaz-Pulido, G., and Dove, S. (2014). Relative roles of endolithic algae and carbonate chemistry variability in the skeletal dissolution of crustose coralline algae. Biogeosciences 11, 4615–4626.

Rosman, J. H., Koseff, J. R., Monismith, S. G., and Grover, J. (2007). A field investigation into the effects of a kelp forest (Macrocystis pyrifera) on coastal hydrodynamics and transport. J. Geophys. Res. 112:C02016. doi: 10.1029/2005JC003430

Stevens, C. L., Hurd, C. L., and Smith, M. J. (2001). Water motion relative to subtidal kelp fronds. Limnol. Oceanogr. 46, 668–678. doi: 10.4319/lo.2001.46.3.0668

van Rooijen, A., Lowe, R., Rijnsdorp, D. P., Ghisalberti, M., Jacobsen, N. G., and McCall, R. (2020). Wave-driven mean flow dynamics in submerged canopies. J. Geophys. Res. Oceans 125:e2019JC015935. doi: 10.1029/2019jc015935

Voulgaris, G., and Trowbridge, J. H. (1998). Evaluation of the Acoustic Doppler Velocimeter (ADV) for turbulence measurements. J. Atmos. Ocean. Tech. 15, 272–289. doi: 10.1175/1520-0426(1998)015<0272:eotadv>2.0.co;2

Wahl, M., Saderne, V., and Sawall, Y. (2016). How good are we at assessing the impact of ocean acidification in coastal systems? Limitations, omissions and strengths of commonly used experimental approaches with special emphasis on the neglected role of fluctuations. Mar. Freshw. Res. 67, 25–36. doi: 10.1071/MF14154

Wahl, M., Schneider Covachã, S., Saderne, V., Hiebenthal, C., Müller, J. D., Pansch, C., et al. (2018). Macroalgae may mitigate ocean acidification effects on mussel calcification by increasing pH and its fluctuations. Limnol. Oceanogr. 63, 3–21. doi: 10.1002/lno.10608

Wheeler, W. (1980). Effect of boundary layer transport on the fixation of carbon by the giant kelp Macrocystis pyrifera. Mar. Biol. 56, 103–110.

Wheeler, W. N. (1988). Algal productivity and hydrodynamics-a synthesis. Prog. Phycol. Res. 6, 23–58.

Keywords: functional forms, canopies, seaweeds, currents, waves, hydrodynamics

Citation: Kregting L, Britton D, Mundy CN and Hurd CL (2021) Safe in My Garden: Reduction of Mainstream Flow and Turbulence by Macroalgal Assemblages and Implications for Refugia of Calcifying Organisms From Ocean Acidification. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:693695. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.693695

Received: 11 April 2021; Accepted: 31 August 2021;

Published: 23 September 2021.

Edited by:

Anne Staples, Virginia Tech, United StatesReviewed by:

Virginia B. Pasour, Army Research Office, United StatesLaurie Carol Hofmann, Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), Germany

Copyright © 2021 Kregting, Britton, Mundy and Hurd. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Louise Kregting, bC5rcmVndGluZ0BxdWIuYWMudWs=

Louise Kregting

Louise Kregting Damon Britton

Damon Britton Craig N. Mundy

Craig N. Mundy Catriona L. Hurd

Catriona L. Hurd