95% of researchers rate our articles as excellent or good

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.

Find out more

PERSPECTIVE article

Front. Mar. Sci. , 20 August 2021

Sec. Marine Conservation and Sustainability

Volume 8 - 2021 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fmars.2021.690163

This article is part of the Research Topic Solving Complex Ocean Challenges Through Interdisciplinary Research: Advances from Early Career Marine Scientists View all 42 articles

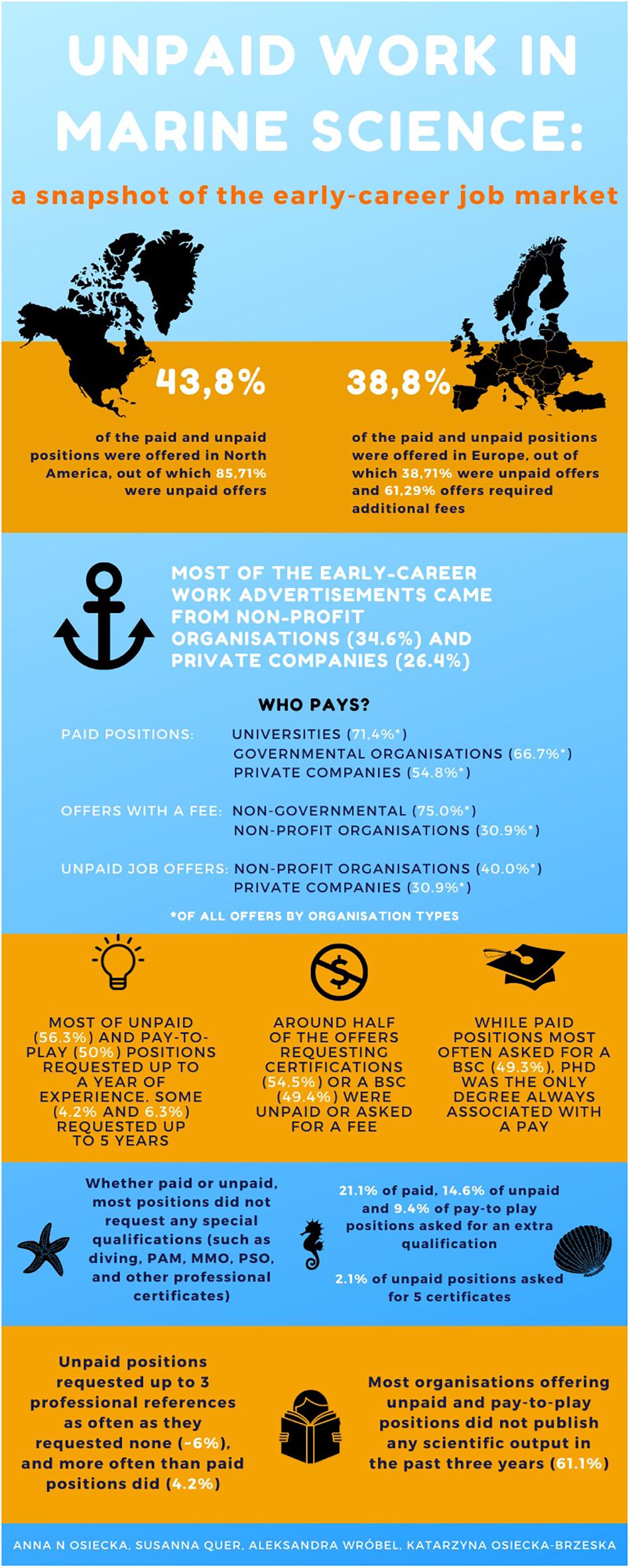

Unpaid positions in environmental sciences are common yet controversial. While they exclude already marginalised groups and are detrimental to the entire job market, many voices maintain that these positions are crucial, support science and conservation in economically disadvantaged areas, and allow early-career scientists their first step into the field. To better understand the real scale and nature of these positions, we reviewed relevant job offers within marine biology and conservation, advertised globally in English, from three random months in 2019–2020, both preceding and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Unpaid and pay-to-work positions were more common than paid jobs, and offered mostly in economically privileged areas, such as North America and Europe. Most of these postings required some or strong experience and education background. Most non-governmental and private organisations offering uncompensated work did not produce any peer-reviewed research output in the last 3 years. This review shows that a considerable proportion of unpaid work contributes to private businesses, and may often breach local labour laws.

Graphical Abstract. Brief summary of the early-career job market in marine biology and conservation.

Uncompensated positions are common in conservation and environmental science. Such positions often require prolonged periods of full-time commitment, while offering little or no support to the workers, or requesting a fee for the opportunity to work (“pay-to-work” or “pay-to-play” positions). Because of their direct costs, but also indifference to the family composition, health, and financial security of participants, unpaid positions are only accessible to the privileged few. This further deepens the already acute racial, gender, health, and class issues in STEM (e.g., Johnson, 2011; Thompson et al., 2011; Williams, 2014; Swan, 2015; Mellifont et al., 2019; Eaton et al., 2020; Wanelik et al., 2020). At the same time, unpaid work does not generally offer significant career advances (Fournier et al., 2019) and its pitfalls are often bigger than the benefits (Siebert and Wilson, 2013). Moreover, it can be difficult to prove as work experience (Allan, 2019).

The problem of discrepancies between paid and unpaid work opportunities was addressed before and has been thoroughly discussed by Whitaker (2003) and Fournier and Bond (2015) with regard to the United States wildlife job market. There was previously no information on the situation outside the United States, or on the nature of such unpaid positions. Even though more perspectives are being slowly included (e.g., Orcutt and Cetinić, 2014; Hooker et al., 2017; Srinivasan, 2018; Michalena et al., 2020; Miriti, 2020), the discussion about the ethics of unpaid labour in ocean science seems to be based largely on personal opinions (Society for Marine Mammalogy, 2020). Yet one cannot improve the situation without looking at it objectively. Here, we provide a snapshot of the early-career (i.e., aimed at students and professionals up to 7 years post doctoral degree) job market in marine biology and conservation, hoping to shed some light on the extent, sources, and legality of unpaid work.

We reviewed a total of 159 job postings related to marine biology and conservation from all over the world. Our search was narrowed to three professional platforms sharing both paid and unpaid work opportunities in English: a marine mammal-oriented mailing list (MARMAM), a website listing ocean conservation jobs1, and a widely used social media group dedicated to early-career job opportunities (Marine Biologist network and job postings). While these platforms do not present an exhaustive list of all work opportunities worldwide, they do provide a good overview of the job market and are widely used by early-career marine scientists, many of whom suggested to use those platforms in our review. Using a random number generator, we selected three random months from the period of a year preceding the data collection: November 2019, February 2020, and April 2020. We screened the platforms for selected keywords representative of the early-career job market (“experience,” “internship,” “job,” “opportunity,” “Ph.D.,” “post-doc,” and “volunteer”), and included only full-time positions requiring up to 7 years of experience. We noted down all relevant information about the postings, paying special attention to the requirements (in terms of experience, education, professional references, and additional qualifications), salary, and location. If the same job was posted repeatedly, or advertised on more than one channel, it was only included once. Since very few postings informed on the actual wages, we grouped the postings into paid, unpaid, and requiring a fee to work.

Additionally, we included the research output of private companies, non-profit organisations (NPOs) and non-governmental organisations (NGOs). To do this, we searched the organisations’ websites (e.g., “Research” and “Communication” sections, as well as blog entries) for information on the total research output (peer-reviewed publications and official reports) of each institution in the past 3 years. If no such information was available, we have classified the institution’s research output as unknown. We have excluded universities and governmental organisations, since these are expected to and do in fact publish immense quantities of scientific output.

Less than a half of all posted positions offered compensation (44.7%), with most of the postings being either unpaid (30.2%) or requiring a fee for the possibility to work (20.1%). Most of the paid and unpaid positions were offered in North America and Europe, and the positions requiring a fee to work were most common in Europe.

Most of the early-career (i.e., requiring not more than 7 years of experience) work advertisements came from non-profit organisations (34.6%) and private companies (26.4%). Universities and governmental organisations offered mostly paid positions (71.4% and 66.7%, respectively), while only roughly half of the private companies’ postings offered compensation. Proportions of offers requiring a fee were exceptionally high in the non-governmental and non-profit organisations (75% and 30.9%, respectively). Most of the unpaid job offers came from non-profit organisations (45.8%) and private companies (27.1%).

Among all wage types, the highest proportion of cases required up to 1 year of experience, and the lowest 5–10 years of experience. Among all wage types, a B.Sc. was requested most frequently, while a Ph.D. was not needed in either unpaid or pay-to-work positions. The proportion of paid work grew with requested qualifications, from no paid positions for unqualified work, 45.5% of paid positions requesting professional certifications or a B.Sc., to a 100% of positions requiring a Ph.D. offering a wage.

Paid positions requested no (40.9%), one (21.1%), two (1.4%), or four (1.4%) additional qualifications (such as diving, Passive Acoustic Monitoring, Marine Mammal Observer, Protected Species Observer, and other professional certificates). Both unpaid and pay-to-play positions usually did not request any additional qualifications (68.8 and 71.9%, respectively). Few positions specifically requested references. Positions requiring a fee did not request any references in 15.6% cases, which constitutes the highest proportion among all wage types.

Although most private and non-governmental institutions published no or up to five scientific outputs in the 3 years preceding the data collection, institutions offering paid work seemed to be less likely to publish nothing at all than these offering no compensation (34.48% vs. 61.11%). However, in nearly half of the cases we were unable to establish the institution’s research output, and this result should be interpreted with caution. Data generated in this review are freely available in an online repository (see section “Data Availability Statement”).

The early-career job market for marine environmentalists offers few, and mostly uncompensated opportunities – over 3 months, only 45% of all the positions we were able to find, and 42.4% of positions requiring up to a B.Sc., were paid. Our survey shows that the overall situation is even worse than previously reported for undergraduate temporary wildlife workers in the United States (54% of positions paid; Fournier and Bond, 2015) in the United States. Additionally, since in most cases information on the exact wage offered was not provided, we are missing information on the proportion of positions waged below the local minimum rate. It is thus possible that the problem is even worse than what we believe, with many paid positions not paid a liveable wage (Whitaker, 2003).

It is worthwhile to note that two of 3 months used for this review preceded the COVID-19 pandemic. In the third month, April 2020, some impact of this situation could already be seen, with very few job advertisements posted. It is possible that the job market has seen some changes since then. One easily noticeable turn was the appearance of online internships with a fee. These offers typically require the candidate to have strong analytical skills and experience, and perform data analysis remotely, using their own hardware, without being offered co-authorship (based on personal inquiries to the organisations). Such remote internships were offered by a few organisations relying on internships with a fee before the coronavirus pandemic.

Interestingly, a large part of the unpaid job postings came from countries with strict labour protection laws, most notably the United Kingdom. In these situations, unpaid internships are illegal, except in few controlled situations, such as vocational placements as a part of an education, or work shadowing, where the intern does not perform any duties (Government UK, 2021). Only about half of private company postings offered compensation. These job postings referred almost entirely to tour operators in private whale watching companies, and contributed to one fourth of all unpaid offers. A number of private for-profit companies went as far as to request a fee from their tour operators. It is extremely important to stress that in many such cases the unpaid work offers may violate local labour laws. What is quite interesting is that some of the unpaid and pay-to-work positions were offered by governmental organisations themselves, particularly in Venezuela and the United States Universities advertised mostly paid positions, and offered unpaid internships exclusively to students.

Work availability is very unevenly distributed, with most positions, and an even larger proportions of the unpaid positions, based in North America and Europe. At the same time, unemployment and temporary work in these regions affect women, immigrants, and Black, Indigenous, and people of colour (BIPOC) population particularly strongly (European Commission, 2016; NSF Report, 2019; Eurostat, 2020). These are the same groups already burdened with issues from systemic discrimination to direct harassment (e.g., Viglione, 2020), and most vulnerable in situations of crisis (e.g., Spector and Overholser, 2020; Staniscuaski et al., 2021; Garcia et al., 2021; Tai et al., 2021; Wright et al., 2021). When taken into account the additional psychological (Woolston, 2019, 2020) and financial (Favaro and Hind-Ozan, 2020) strain on early career scientists, the overall pressure on any minority in STEM is alarming. Providing fair wages is crucial to increasing retention of groups underrepresented in the field (Jensen et al., 2021). As an early-career scientist, one is often advised to “simply find a second job,” though rarely followed by ideas on how to do so in a strongly biassed job market, remote location, and often unregulated working hours. The narrative of finding a side job to support unpaid work in one’s own discipline is thus not only quite unrealistic, but also excluding to those that do not start their career from a position of privilege.

Unpaid workers can unwillingly perpetuate the vicious circle of labour abuse, making it possible for companies to lower the rates of employed staff (Siebert and Wilson, 2013) and deepen social inequalities (Shade and Jacobson, 2015). Yet in the scarcity of paid work, desperate early-career environmentalists are often forced to accept pays below the industry standard. The results of this are very clear: for example, the wages of Marine Mammal Observers and Protected Species Observers are dramatically lower than these of any other offshore employees, comparable only to these of unskilled workers, such as pot washers (Glassdoor, 2021a,b; Wind Rose Network, 2021), and well below the average salaries of skilled staff in the oil industry (SPE Research, 2019). Yet these are people directly responsible for running or halting large, invasive operations of a billion dollar business, and as a result for the life or death of protected marine animals. Furthermore, professional field technicians can be pushed out of the job market by workers willing to work for little or no compensation, which can hinder the quality of research and conservation (Fournier and Bond, 2015). Protecting early stages jobs is thus crucial to protecting the entire job market and ensuring fair wages for everyone.

It is widely understood that finances are tight for environmental organisations, and competition for funding is fierce. This indeed often comes up as an argument in defence of unpaid positions, since for some organisations these could be the only way to get enough labour and funding to do the necessary work (Elwen and Gridley, 2020; Society for Marine Mammalogy, 2020). We recognise that the laws protecting against unfair work conditions need to be complemented by an increase in funding to research, and that access to the existing funds may be hindered by many factors. Especially in economically less advantaged countries or countries with no or limited access to funding schemes, internship fees might be the main or only source of income for the NGOs. However, we would like to stress that most of the unpaid work in our review was offered in wealthy countries, and a large amount of this work is illegal and/or contributes to private businesses. The problem does not come from underfunded organisations in marginalised countries.

Non-governmental organisations and non-profit organisations offer a large part of the unpaid and pay-to-work positions, but also an important part of all marine jobs, and some of them have great contributions to science and conservation. To limit parachute science and provide training for locals, some organisations introduced policies that only require fees of foreign interns. Volunteering can be an enriching experience and a great tool to include marginalised groups (Miller et al., 2002; O’Brien et al., 2010, 2011). In voluntourism, the participant pays a fee for an organised volunteering or internship opportunity, often in locations seen as “exotic” by the Eurocentric world. Such arrangements are often dictated by neoliberal market laws, where the intern is a demanding client rather than a worker (e.g., Wearing et al., 2005; Lyons et al., 2012; St-Amant et al., 2018), and can perpetuate neocolonialist relations (e.g., Mahrouse, 2012; Pastran, 2014; St-Amant et al., 2018). Yet, they can be beneficial when practiced responsibly (Palacios, 2010; Coghlan and Gooch, 2011; McGehee, 2014). Not every unpaid work is abusive, but volunteering should be truly voluntary, and never required.

While income from voluntourism might be very necessary for some organisations, is a person paying for the right to work really a worker? In situations where paid interns are absolutely necessary to maintain the running costs of NPOs and NGOs, we suggest considering such experiences as “courses,” “training,” or “eco-tourism,” especially when no or minimal skills are required. To avoid labour abuse, it is necessary to carefully name positions according to their workload and compensation, and follow not only the local legal requirements, but good practices guidelines within the field (Parsons and Scarlett, 2020). Words matter, and such a change in language can hopefully help remove the unrealistic expectations for entry-level positions in our field and move past the notion that one needs years of experience to deserve to pay their bills.

Finally, one reason to engage in unpaid work is the necessity of building up a strong publication record, since paid Ph.D. and post-doc positions are often extremely competitive, and early co-authorship with top scientists is very beneficial (Li et al., 2019). Our review focussed only on the scientific output of private, non-governmental, and non-profit organisations. Within this group, the highest proportion of organisations that published at all was found among those offering paid positions. While many NGOs did not produce any scientific output, some of them had a very strong publication record, and many were engaged in outreach and education (see Supporting Data). These observations may indicate a general pattern, though they must be interpreted with caution, since in many cases we were unable to determine the organisation’s research output. Should publishing be the motivation to engage in unpaid work, it is advisable to carefully check the academic output of an organisation, as well as its authorship policies, since volunteering can, but rarely does translate into authorship.

This review should be understood as a snapshot of the situation, and not an exhaustive market study. We have excluded platforms listing exclusively paid work opportunities, as well as those directed to one nationality, and in languages other than English. While this is the dominant language in the field, this can be a source of potential bias. A larger-scale review would lead to a more robust inference, yet the total sample size of only 159 advertisements over 3 months emphasises just how limited the job market is for marine biologists and conservationists. One of the platforms we used focuses specifically on marine mammalogy – field that tends to attract enthusiastic workers, sometimes happy to simply have the opportunity to interact with charismatic megafauna, and may thus offer higher numbers of unpaid positions than other marine fields.

We focussed on early-career options in the understanding of up to 7 years after the completion of a doctoral degree, and as such our review is not representative of the entire marine environmental job market. The situation may of course be very different for senior colleagues. However, it is important to stress that the jobs we reviewed here were not addressed solely to people on the very first steps of their careers or undergraduate students. In this review, only the few available positions requiring a Ph.D. always guaranteed a pay. While it seems understandable that the more qualified positions are more likely to be paid, it is unreasonable to demand a doctoral degree as a minimum qualification securing a wage, especially in non-academic positions. Yet such seems to be the case in marine biology and conservation. If one wants to make their way in the field, there is often no other choice but to work for free. Additionally, there is a strong expectation of multiple “specialisations,” even though such a lack of professional focus can often be detrimental to science and conservation (Cosentino and Souviron-Priego, 2021). This leads to a situation in which professionals with experience, education, a network of referees, and expensive professional certifications are asked to volunteer for years, with no insurance or future job security.

While unpaid or “pay-to-play” labour is common both in and outside academia, we should make an effort to stop normalising it. Recently, the issue of unpaid work has been taken up within the Society for Marine Mammalogy, sparking quite an intensive debate and leading to declarations of action toward a more inclusive field (Jacobson et al., 2020). In October 2020, the European Parliament adopted a resolution urging the member states to stop the exploitation in unpaid internships, clearly stating this practice is a violation of workers’ laws (European Parliament, 2020; Nadkarni and Kolinska, 2020). After years of discussion, this measure offers a promising situation in which action backed with funding is and will be taken against such practices.

Unpaid positions are more common than paid jobs, creating unrealistic expectations to enter the field of marine biology and conservation. Many of these positions may breach local labour protection laws, and contribute to private profit rather than science and conservation. It is high time we remove the harmful practices and rethink the ways to sustain small or non-profit organisations.

The datasets presented in this study can be found in online repositories. The names of the repository/repositories and accession number(s) can be found below: http://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/C36JN.

AO and SQ: idea of the review. AO, KO-B, and SQ: design of the study. SQ: data collection. KO-B, SQ, and AW: data processing and analysis. AO: first draft and the review process. AO, SQ, AW, and KO-B: contribution to final manuscript. KO-B, AO, and AW: Graphical Abstract preparation. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

This work was performed independently of the authors’ affiliations, and none of the authors received a compensation. AW was supported by Polish National Science Centre grant “Sonatina” no. 2020/36/C/NZ8/00013. AO was supported by the University of Gdańsk Dean of Biology grant no. 539-D050- B853-21.

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Allan, K. (2019). Volunteering as hope labour: the potential value of unpaid work experience for the un-and under-employed. Cult. Theory Crit. 60, 66–83. doi: 10.1080/14735784.2018.1548300

Coghlan, A., and Gooch, M. (2011). Applying a transformative learning framework to volunteer tourism. J. Sustain. Tour. 19, 713–728. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2010.542246

Cosentino, M., and Souviron-Priego, L. (2021). Think of the Early career researchers! Saving the oceans through collaborations. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:46. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.574620

Eaton, A. A., Saunders, J. F., Jacobson, R. K., and West, K. (2020). How Gender and Race Stereotypes Impact the Advancement of Scholars in STEM: professors’ Biased Evaluations of Physics and Biology Post-Doctoral Candidates. Sex Roles 82, 127–141. doi: 10.1007/s11199-019-01052-w

Elwen, S., and Gridley, T. (2020). ‘Voluntourism’ is Often Critical to Academic Careers and Conservation, but the Practice has Drawn Flak. Daily Maverick. Available online at: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/opinionista/2020-07-16-voluntourism-is-often-critical-to-academic-careers-and-conservation-but-the-practice-has-drawn-flak/ (accessed July 16, 2020).

European Commission (2016). Communication from the Commission to the European Parliament, the Council, the European Economic and Social Committee and the Committee of the Regions. Investing in Europe’s Youth. COM(2016) 940 final. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/transparency/regdoc/rep/1/2016/EN/COM-2016-940-F1-EN-MAIN.PDF (accessed January 21, 2021).

European Parliament (2020). European Parliament resolution on the Youth Guarantee (2020/2764(RSP)). Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/doceo/document/TA-9-2020-0267_EN.html (accessed January 21, 2021).

Eurostat (2020). Being young in Europe today - Labour Market - Access and Participation. Available online at: https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Being_young_in_Europe_today_-_labour_market_-_access_and_participation#Education_and_employment_patterns (accessed January 21 2021).

Favaro, B., and Hind-Ozan, E. (2020). SciSpends: an exploratory survey investigating nonreimbursed expenses in biological sciences. FACETS 5, 989–1005. doi: 10.1139/facets-2020-0026

Fournier, A. M., and Bond, A. L. (2015). Volunteer field technicians are bad for wildlife ecology. Wildl. Soc. Bull. 39, 819–821. doi: 10.1002/wsb.603

Fournier, A. M., Holford, A. J., Bond, A. L., and Leighton, M. A. (2019). Unpaid work and access to science professions. PLoS One 14:e0217032. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0217032

Garcia, M. A., Homan, P. A., García, C., and Brown, T. H. (2021). The color of COVID-19: structural racism and the disproportionate impact of the pandemic on older Black and Latinx adults. J. Gerontol. Ser. B 76, e75–e80.

Glassdoor (2021a). Marine Mammal Observer Salaries. Available online at: https://www.glassdoor.com/Salaries/marine-mammal-observer-salary-SRCH_KO0,22.htm (accessed January 15, 2021).

Glassdoor (2021b). Pot Washer Salaries in United States. Available online at: https://www.glassdoor.co.uk/Salaries/us-pot-washer-ship-salary-SRCH_IL.0,2_IN1_KO3,13_KE14,18.htm?clickSource = searchBtn (accessed January 20, 2021).

Government UK (2021). Employment Rights and Pay for Interns. Available online at: https://www.gov.uk/employment-rights-for-interns (accessed January 20, 2021).

Hooker, S. K., Simmons, S. E., Stimpert, A. K., and McDonald, B. I. (2017). Equity and career-life balance in marine mammal science? Mar. Mamm. Sci. 33, 955–965. doi: 10.1111/mms.12407

Jacobson, E. K., Malinka, C. E., and Siple, M. C. (2020). Petition to the Society for Marine Mammalogy Regarding Unpaid Positions. Available online at: https://zenodo.org/record/3956566#.YQEJipgzbIU (accessed January 15, 2021).

Jensen, A. J., Bombaci, S. P., Gigliotti, L. C., Harris, S. N., Marneweck, C. J., Muthersbaugh, M. S., et al. (2021). Attracting diverse students to field experiences requires adequate pay, flexibility, and inclusion. Bioscience 71, 757–770. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biab039

Johnson, D. R. (2011). Women of color in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). New Dir. Inst. Res. 152, 75–85. doi: 10.1002/ir.410

Li, W., Aste, T., Caccioli, F., and Livan, G. (2019). Early coauthorship with top scientists predicts success in academic careers. Nat. Commun. 10:5170.

Lyons, K., Hanley, J., Wearing, S., and Neil, J. (2012). Gap year volunteer tourism: Myths of global citizenship? Ann. Tour. Res. 39, 361–378.

Mahrouse, G. (2012). “Solidarity Tourism and International development internships: some critical reflections,” in Organize!: Building from the Local for Global Justice, eds A. Choudry, J. Hanley, and E. Shragge (Oakland: PM Press), 227–240.

McGehee, N. G. (2014). Volunteer tourism: evolution, issues and futures. J. Sustain. Tour. 22, 847–854. doi: 10.1080/09669582.2014.907299

Mellifont, D., Smith-Merry, J., Dickinson, H., Llewellyn, G., Clifton, S., Ragen, J., et al. (2019). The ableism elephant in the academy: a study examining academia as informed by Australian scholars with lived experience. Disabil. Soc. 34, 1180–1199. doi: 10.1080/09687599.2019.1602510

Michalena, E., Straza, T. R., Singh, P., Morris, C. W., and Hills, J. M. (2020). Promoting sustainable and inclusive oceans management in Pacific islands through women and science. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 150:110711. doi: 10.1016/j.marpolbul.2019.110711

Miller, K. D., Schleien, S. J., Rider, C., Hall, C., Roche, M., and Worsley, J. (2002). Inclusive volunteering: benefits to participants and community. Ther. Recreat. J. 36, 247–259.

Miriti, M. N. (2020). The elephant in the room: race and STEM diversity. Bioscience 70, 237–242. doi: 10.1093/biosci/biz167

Nadkarni, I. T., and Kolinska, D. (2020). Parliament Calls on Member States to Fully Exploit the European Youth Guarantee. Available online at: https://www.europarl.europa.eu/news/en/press-room/20201002IPR88443/parliament-calls-on-member-states-to-fully-exploit-the-european-youth-guarantee (accessed January 15, 2021).

NSF Report (2019). Women, Minorities, and Persons with Disabilities in Science and Engineering. Available online at: https://ncses.nsf.gov/pubs/nsf19304/digest (accessed January 15, 2021).

O’Brien, L., Burls, A., Townsend, M., and Ebden, M. (2011). Volunteering in nature as a way of enabling people to reintegrate into society. Perspect. Public Health 131, 71–81. doi: 10.1177/1757913910384048

O’Brien, L., Townsend, M., and Ebden, M. (2010). ‘Doing something positive’: Volunteers’ experiences of the well-being benefits derived from practical conservation activities in nature. Voluntas 21, 525–545. doi: 10.1007/s11266-010-9149-1

Orcutt, B. N., and Cetinić, I. (2014). Women in oceanography: continuing challenges. Oceanography 27, 5–13. doi: 10.5670/oceanog.2014.106

Palacios, C. M. (2010). Volunteer tourism, development and education in a postcolonial world: conceiving global connections beyond aid. J. Sustain. Tour. 18, 861–878. doi: 10.1080/09669581003782739

Parsons, E. C. M., and Scarlett, A. (2020). The problem of toxic internships in the environmental field: guidelines for more equitable professional experiences. J. Environ. Stud. Sci. 10, 352–354. doi: 10.1007/s13412-020-00629-2

Shade, L. R., and Jacobson, J. (2015). Hungry for the job: gender, unpaid internships, and the creative industries. Sociol. Rev. 63, 188–205. doi: 10.1111/1467-954x.12249

Siebert, S., and Wilson, F. (2013). All work and no pay: consequences of unpaid work in the creative industries. Work Employ. Soc. 27, 711–721. doi: 10.1177/0950017012474708

Society for Marine Mammalogy (2020). Discussion Panel: Unpaid Positions in Science. 2020. Available online at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lndXvE0nR0c (accessed January 15, 2021).

Spector, N. D., and Overholser, B. (2020). COVID-19 and the slide backward for women in academic medicine. JAMA Network Open 3:e2021061. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21061

SPE Research (2019). SPE Membership Salary Survey. Available online at: https://www.spe.org/media/filer_public/ee/ff/eeffeeec-4076-45f9-b578-8aec517b0adb/2019_salary_survey_highlight_report.pdf (accessed January 15, 2021).

Srinivasan, M. (2018). Marine mammal science without borders. Aquat. Mamm. 44, 736–744. doi: 10.1578/am.44.6.2018.736

St-Amant, O., Ward-Griffin, C., Berman, H., and Vainio-Mattila, A. (2018). Client or volunteer? Understanding Neoliberalism and neocolonialism within international volunteer health work. Glob. Qual. Nurs. Res. 5:2333393618792956.

Staniscuaski, F., Kmetzsch, L., Zandona, E., Reichert, F., Soletti, R. C., Ludwig, Z. M. C., et al. (2021). Gender, race and parenthood impact academic productivity during the COVID-19 pandemic: from survey to action. Front. Psychol. 12:663252. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2021.663252

Swan, E. (2015). “The internship class: subjectivity and inequalities –gender, race and class,” in Handbook of Gendered Careers in Management, eds A. M. Broadbridge and S. L. Fielden (Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing).

Tai, D. B. G., Shah, A., Doubeni, C. A., Sia, I. G., and Wieland, M. L. (2021). The disproportionate impact of COVID-19 on racial and ethnic minorities in the United States. Clin. Infect. Dis. 72, 703–706. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciaa815

Thompson, L., Perez, R. C., and Shevenell, A. E. (2011). Closed ranks in oceanography. Nat. Geosci. 4, 211–212. doi: 10.1038/ngeo1113

Viglione, G. (2020). Racism and harassment are common in field research-scientists are speaking up. Nature 585, 15–16. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02328-y

Wanelik, K. M., Griffin, J. S., Head, M. L., Ingleby, F. C., and Lewis, Z. (2020). Breaking barriers? Ethnicity and socioeconomic background impact on early career progression in the fields of ecology and evolution. Ecol. Evol. 10, 6870–6880. doi: 10.1002/ece3.6423

Wearing, S., McDonald, M., and Ponting, J. (2005). Building a decommodified research paradigm in tourism: the contribution of NGOs. J. Sustain. Tour. 13, 424–439. doi: 10.1080/09669580508668571

Whitaker, D. M. (2003). The use of full-time volunteers and interns by natural-resource professionals. Conserv. Biol. 17, 330–333. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1739.2003.01503.x

Williams, J. C. (2014). Double jeopardy? An empirical study with implications for the debates over implicit bias and intersectionality. Harv. J. Law Gend. 37, 185–569.

Wind Rose Network (2021). Available online at: http://www.windrosenetwork.com/Jobs-on-Offshore-Oil-Rigs-Food-Preparation-and-Services-Department (accessed January 15, 2021).

Woolston, C. (2020). Postdoc survey reveals disenchantment with working life. Nature 587, 505–508. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-03191-7

Keywords: early-career, unpaid work, ecotourism, volunteering, unpaid internships, work abuse

Citation: Osiecka AN, Quer S, Wróbel A and Osiecka-Brzeska K (2021) Unpaid Work in Marine Science: A Snapshot of the Early-Career Job Market. Front. Mar. Sci. 8:690163. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.690163

Received: 02 April 2021; Accepted: 26 July 2021;

Published: 20 August 2021.

Edited by:

Samiya Ahmed Selim, Leibniz Centre for Tropical Marine Research (LG), GermanyReviewed by:

Eiren Jacobson, University of St Andrews, United KingdomCopyright © 2021 Osiecka, Quer, Wróbel and Osiecka-Brzeska. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (CC BY). The use, distribution or reproduction in other forums is permitted, provided the original author(s) and the copyright owner(s) are credited and that the original publication in this journal is cited, in accordance with accepted academic practice. No use, distribution or reproduction is permitted which does not comply with these terms.

*Correspondence: Anna N. Osiecka, YW5uLm9zaWVja2FAZ21haWwuY29t

†These authors have contributed equally to this work and share first authorship

Disclaimer: All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article or claim that may be made by its manufacturer is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Research integrity at Frontiers

Learn more about the work of our research integrity team to safeguard the quality of each article we publish.